Abstract

Short-lived positron-emitting radiotracer techniques provide time-dependent data that are critical for developing models of metabolite transport and resource distribution in plants and their microenvironments. Until recently these techniques were applied to measure radiotracer accumulation in coarse regions along transport pathways. The recent application of positron emission tomography (PET) techniques to plant research allows for detailed quantification of real-time metabolite dynamics on previously unexplored spatial scales. PET provides dynamic information with millimeter-scale resolution on labeled carbon, nitrogen, and water transport over a small plant-size field of view. Because details at the millimeter scale may not be required for all regions of interest, hybrid detection systems that combine high-resolution imaging with other radiotracer counting technologies offer the versatility needed to pursue wide-ranging plant physiological and ecological research. In this perspective we describe a recently developed hybrid detection system at Duke University that provides researchers with the flexibility required to carry out measurements of the dynamic responses of whole plants to environmental change using short-lived radiotracers. Following a brief historical development of radiotracer applications to plant research, the role of radiotracers is presented in the context of various applications at the leaf to the whole-plant level that integrates cellular and subcellular signals and∕or controls.

Primary plant productivity sustains life on Earth and is a principal component of the planet’s system that regulates atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) concentration. A central goal of plant science is to understand the regulatory mechanisms of plant growth in a changing environment. Key to our understanding of productivity are the plant carbon and nutrient balances: how does the plant acquire and use resources for maintenance and protection to maximize individual growth and reproductive success? Aspects of this question have been examined independently at different organizational scales through genetic, molecular, organismal, and ecosystem studies. Increasingly, plant scientists are developing experimental techniques and quantitative models that enable them to integrate across scales for a more complete understanding of whole-plant responses to environmental change. For example, various genetic mutants are used to elucidate the role of specific metabolites in the control of photosynthesis (e.g., Swissa et al., 1980; Sterky et al., 1998); mutants are coupled with high-resolution imaging to elucidate the role of sugars in signaling and control of plant growth (e.g., Schurr et al., 2006; Smith and Stitt, 2007), or of hormones in root gravitropic responses (Chavarria-Krauser et al., 2008); and chlorophyll fluorescence is measured remotely to estimate heterogeneous canopy photosynthesis in forests (Osmond et al., 2004; Ananyev et al., 2005). Although we do not fully understand several processes and feedback mechanisms important for plant growth, descriptive analytical models of plant photosynthesis that incorporate the complexity of growth regulatory networks will enable reliable quantitative predictions of plant responses to environmental change.

Through collaborative research within and among disciplines, scientists have developed new tools to address the integration of plant growth processes across spatial scales. These tools are helpful in developing a coherent description of plant development across scales of complexity from the genomic to the whole-plant physiological responses to the environment. At one end of the spectrum, this integration involves knowledge of biochemical regulatory networks that are controlled by gene expression (e.g., Tyson et al., 2001; Tyson et al., 2003). For example, using the unicellular yeast as our best-known physiological system, computer models of enzyme and protein-driven reaction networks are developed through sustained interaction between theory and experiment (e.g., Lapinskas et al., 1995; Himmelbach et al., 1998; Buchwald and Sveiczer, 2006). At the leaf level in plants, the simple biochemical model of photosythesis developed by Farquhar and colleagues (Farquhar et al., 1980) has been extended to describe a network of enzyme-driven biochemical reactions (Zhu et al., 2007). Collaborations between theoretical biologists and experimentalists are enabling the development of increasingly more sophisticated and complete computer models of biochemical regulatory reaction networks in systems biology. At the other end of the spectrum, canopy photoysnthesis models couple processes at the individual leaf level with canopy and remote sensing data to integrate productivity at regional and global scales (e.g., Field et al., 1995; Chen and Coughenour, 2004; Sasai et al., 2007). These large scale models integrate the plant response to environmental stresses. Intermediate to these extremes, regulatory processes at the whole-plant level sense and respond to external limiting factors that control productivity. The use of short-lived radioistopes in whole-plant studies can help elucidate the processes that link the enzyme-driven biochemical reactions to the physiological responses of plants to environmental stimuli (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Hierarchical temporal and spatial processes of plant growth and development (based on Osmond, 1989).

Different processes at the subcellular and cellular level can link to higher organizational levels via signal transduction. At small spatial scales autoradiography, which requires disturbance of the plant system, provides detailed images of radiotracer accumulation. At the tissue, whole-plant, and plant microenvironment levels, dynamic processes can be measured using short-lived positron-emitting radioisotopes with gamma-ray detection and imaging techniques.

Plant growth and environmental change

Plant productivity is strongly influenced by environmental stresses that include drought, temperature extremes, nutrient limitation, and predator or pathogen pressure. All are likely to increase with global climate change, and the impact will vary regionally (e.g., Fischlin et al., 2007). Although we have a good understanding of the photosynthetic process itself, detailed understanding is still missing for how plants sense chronic stresses (e.g., drought, low nutrient availability) and heterogeneous changes in the environment (e.g., sunflecks) that can result in short-term stresses, and the consequent impact of such stresses on growth and development. Osmond (1989) once forecasted that the now commonly used chlorophyll fluorescence technique could be a useful tool to scale our understanding of stress on photosynthesis from small-scale (within leaf tissue) indicator to large-scale (forest canopy) integrator (Jones and Morison, 2007). Similarly, we predict that short-lived radioisotope techniques will provide data that are crucial for developing models that quantitatively link the underlying biochemical reactions to physiological responses, i.e., to model the complexity of plant growth and development across different scales (Fig. 1). For example, sugars, which are produced in source leaves and needed in developing sinks, are both sensing and signaling molecules between cells and between organs (e.g., review by Rolland et al., 2006). Sugar signaling can interact with other signals (e.g., hormones) to control plant development under different environmental conditions. As sensors or integrators of stress, sugars and other signal molecules rely on the phloem for long-distance transport (Lough and Lucas, 2006). Coupling the dynamic transport of the signal in response to environmental stress with gene expression in transgenic plants can provide us with better predictive models to understand integrated plant development and growth. A better mechanistic understanding of the phloem transport itself is in progress (Minchin and Lacointe, 2005; Thompson, 2006) and will benefit from dynamic measurement techniques. At a larger spatial scale, chemical signals are also used for communication between plants (competition or facilitation), or between plant and pathogen or microbes (Paiva, 2000). The availability of new techniques or novel applications of established methods can help decipher the role of metabolite transport and regulation.

Imaging technology and plant science

A variety of technologies are available that enable researchers to span a wide range of spatial scales in plant studies, from submicron resolution using optical microscopy techniques and fluorescent markers (Stephens and Allan, 2003; Haustein and Schwille, 2007) to millimeter-scale resolution using x-ray computed tomography (e.g., Kaestner et al., 2006) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI; e.g., MacFall et al., 1990; Windt et al., 2006). Dynamic processes can be imaged using time-lapse fluorescence microscopy with micron-scale resolution by taking successive images at the microsecond to millisecond time range (Weijer, 2003; Rieder and Khodjakov, 2003). For example, this technique has been used to determine patterns of the dominant gene expression in developing roots of Arabidopsis (Brady et al., 2007). At a larger spatial scale (tenths of mm), MRI has been employed in medicine to visualize anatomical structure, as well as in plants to observe water content in and around root systems (e.g., MacFall et al., 1990). In addition, techniques that use short-lived radioisotopes with gamma-ray detection provide the capacity to visualize dynamic transport and allocation of metabolites at large distance scales and consequently give information important for understanding whole-plant physiological responses to environmental change in real time. The combined application of these techniques provides detailed information about biological structure and function over spatial dimensions ranging from cells to entire organisms and between-organism interactions.

Coordination between the sensing and signal transport through the plant and∕or out of the plant into the environment requires dynamic measurement methods. Short-lived radioisotopes are already used successfully at high specific activity to show the transport of jasmonate, a signal metabolite involved in plant defense, in whole plants (Thorpe et al., 2007). Additionally, Ferrieri and colleagues assessed the role of recently fixed carbon with short-lived radiotracers and demonstrated that treatment of poplar seedlings with jasmonic acid increases isoprene emission (Ferrieri et al., 2005), leaf export of mobile sugar (Babst et al., 2005), and plant metabolism of carbon tetrachloride (Ferrieri et al., 2006). Carbon-11 tracer measurements designed to study carbon metabolism dynamics cover a wide range of spatial scales within plants. For example, Minchin and colleagues have measured unloading and reloading of photoassimilate in bean stem (Minchin and Thorpe, 1987); carbon partitioning to whole versus surgically modified pea ovules (Minchin and Thorpe, 1989); changes in partitioning to soybean root nodules following treatment of the root system with nitrate (Thorpe et al., 1998); the short and long-term effects of photosynthate availability on carbon partitioning to apple fruits (Minchin et al., 1997); the effect of electric shock and cold shock on phloem transport (Pickard et al., 1993); and the effects of temperature (Minchin et al., 1994) and osmotica (Williams et al. 1991) on carbon partitioning in split root systems of barley. Additionally, 11C radiotracer techniques were applied in an ecological context to measure plant response to herbivory by nematodes (Freckman et al., 1991) and grasshoppers (Dyer et al., 1991) at Duke University, and more recently, by inducible response to simulated leaf herbivory (Babst et al., 2005; Schwachtje et al., 2006). Likewise, measurements using short-lived isotopes are valuable in studies of root growth dynamics and nutrient uptake in a heterogenous environment.

Positron emission tomography (PET) is a noninvasive imaging technique that can achieve spatial resolution on the order of millimeters and provide quantitative information about dynamic physiological processes over a relatively large field of view. PET utilizes radioactive nuclei to label biologically active molecules. These systems have been used clinically for the diagnosis of human disease for about 30 years (Ter-Pergossian et al., 1975; Rohren et al., 2004), and many research centers now employ microPET instruments to better understand disease by studying small animals (Cherry et al., 1997; Chatziioannou, 2002). In addition to biomedical applications, PET techniques are used to study the regulation of plant growth and development via metabolite transport. Because plants are sessile organisms, they have developed adaptations to deal with a heterogeneous environment, which often includes metabolite signaling to induce a cascade of physiological responses. Plant labeling entails the integration of short-lived positron-emitting isotopes such as carbon-11 (11C), nitrogen-13 (13N), oxygen-15 (15O), and fluorine-18 (18F) into biologically active molecules, nutrients, or compounds. The radiotracers (i.e., labeled molecules) are absorbed via normal metabolism and distributed throughout the plant. In vivo detection of the gamma rays emitted by the radioisotopes enables researchers to track the transport and distribution of the radiotracers in the plant as a function of time. The short radioactive half-lives of the radiotracers and the noninvasive detection of the decay products allow the same plant to be tested multiple times without destructive sampling to determine its response to environmental changes. Additionally, a suite of different short-lived radiotracers can be applied to the same plant in a short period of time to investigate the transport and allocation of various metabolites (Caldwell et al., 1984;Grodzinski et al., 1984). These features make short-lived positron-emitting radiotracers attractive candidates for studying the dynamics of metabolite transport in plants. Also, the time-ordered data obtained with radiotracers provides the information required to causally connect plant responses to specific environmental changes.

While earlier studies monitored radiotracer transport and accumulation on a coarse spatial scale, recent experiments use PET techniques to produce high-resolution images of radiotracer transport and allocation (e.g., Keutgen et al., 2005). In this perspective we describe recent studies using short-lived radioisotopes to examine aspects of plant growth at different spatiotemporal scales. We start with a brief review of the historical development of radiotracer techniques followed by a discussion of the general use of positron emission techniques in plant research. We concentrate on a radiotracer labeling system that is based on a hybrid gamma-ray detection platform being developed at Duke University for positron emission imaging and counting in plant studies. This radiotracer system is primarily for studies of carbon, nutrient, and water transport and allocation in plants.

HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE APPLICATION OF RADIOTRACERS TO PLANT STUDIES

A variety of techniques are used to measure the transport and distribution of substances in plants. These include methods that employ both stable and radioactive isotopes. Examples include real-time tracing of short-lived radioisotopes (e.g., 11C, 13N), measuring accumulation of long-lived radioisotopes (e.g., 14C) and stable isotopes (e.g., 13C, 15N), and studying water flow with MRI.

The use of short-lived positron emitters

The first plant studies using short-lived radioisotopes were performed nearly 70 years ago by Ruben et al. (1939) in their work on photosynthesis using 11C. Because of the short life of 11C (20.4 min), Ruben soon searched for and discovered a long-lived radioisotope, 14C (half-life 5730 years) that has been used extensively in metabolite accumulation (Gest, 2005; and see below). Nevertheless, since then many types of plant physiology studies have been performed using carbon-11 dioxide (11CO2) as a radiotracer. Labeled 11CO2 is particularly useful in studies of carbohydrate source-sink relationships in plants. Because CO2 is the primary substrate for photosynthesis, 11CO2 is incorporated into plant tissue as photoassimilates, i.e. carbohydrates that can be tracked through the plant by detecting the gamma radiation emitted in the decay of 11C nuclei. The isotopic discrimination between11CO2 and 12CO2 during photosynthesis is likely similar in magnitude to that between 13C and 12C, which is on the order of a few percent (Farquhar et al., 1982; Thorpe and Minchin, 1991). The 11C nucleus decays by emitting a positron (i.e., an anti-electron) and has a radioactive half-life of 20.4 min. Positrons emitted by the decay of 11C nuclei lose energy by collisions in matter until they reach thermal energies and annihilate with an electron. This annihilation produces two gamma rays (high energy photons, each with 511 keV energy) that are emitted collinearly and in opposite directions to conserve linear momentum. These gamma rays are attenuated very little by the tissue of small plants and may be detected singly with collimated detectors or in coincidence to trace the distribution of 11C in real time andin vivo (Minchin and Thorpe, 2003).This technique allows for multiple radiotracer labelings of the same plant, which leads to a better understanding of biological variations within a single organism. Because the radioactive half-life of 11C is about 20 min, it is particularly useful for the study of short-term effects of environmental stimuli on carbon translocation dynamics and source-sink relationships. The fundamental limit on the spatial resolution achievable using positron-emitting tracers is governed by the finite range that the positrons travel inside the material before losing all their kinetic energy via ionization and annihilating with an electron. This travel range is a function of the initial kinetic energy of the positron and therefore is different for each radiotracer isotope (Table 1). However, it is generally the main source of uncertainty that limits the accuracy of determining the positron production location (i.e., spatial resolution) to a few millimeters.

Table 1.

Properties of positron-emitting isotopes used to measure metabolite transport and allocation in plants. Emax and Emean are the maximum and mean energy of the emitted positron, and t1∕2 is the radioactive half-life of the isotope. The maximum and mean range of the positrons is given for water because this is a close approximation to plant tissue. The data in this table are from Bailey et al. (2003).

| Radioisotope | Emax (MeV) | Emean (MeV) | t1∕2 (min) | Max range in water (mm) | Mean range in water (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11C | 0.959 | 0.326 | 20.4 | 4.1 | 1.1 |

| 13N | 1.197 | 0.432 | 9.96 | 5.2 | 1.5 |

| 18F | 0.633 | 0.202 | 109.8 | 2.4 | 0.6 |

| 15O | 1.738 | 0.696 | 2.03 | 7.3 | 2.5 |

For improved spatial resolution, positron-emitting radiotracers can also be imaged using positron autoradiography, which gives spatial detail on the order of hundreds of microns (Schmidt and Smith, 2005) by direct detection of the positrons. This resolution is about an order of magnitude better than that achievable with PET because the positron energy is deposited directly on the phosphor imaging plate before it has the opportunity to annihilate. Direct detection of the positron eliminates the uncertainty in radiotracer location that is due to the distance the positron travels before annihilating. This technique has been applied in whole-plant studies to determine metabolite partitioning at the end of a labeling period using phosphor plate imaging of the plant (Babst et al., 2005; Ferrieri et al., 2006). Positron autoradiography has also been used to investigate radiotracer allocation in detached leaves of tobacco plant (Thorpe et al., 2007). While positron autoradiography provides much better spatial detail than PET, real-time dynamic information cannot be attained without disturbing the labeled organism. Tanoi et al. (2005) have demonstrated an imaging system in which the labeled plant is placed directly against a vertically mounted imaging plate. Sequential images provide information about flow dynamics, but exposures must be performed in the dark because fluorescent light can erase the information stored in the imaging plate. A system of this type could be used to image plant roots without disrupting the biological system, but it is not ideal for above-ground regions of the plant that behave differently in light and dark conditions. PET cannot provide the same level of spatial detail, but it requires minimal disturbance to the organism.

In addition to 11C, other short-lived positron-emitting isotopes have been used for plant physiology studies. Nitrogen-13 (13N) decays by positron emission with a radioactive half life of 9.96 min. This isotope can be introduced to plants in the form of 13N-labeled nitrate (e.g., Glass et al., 1985) or ammonium (e.g., Kronzucker et al., 1995c) ions in solution, or as 13N-labeled nitrogen gas (e.g., Bishop et al., 1986). The 13N-labeled substances are generally applied to plant roots to study nutrient absorption and transport in the plant under various environmental conditions (e.g.,McNaughton and Presland, 1983). To extract root nitrate flux characteristics, compartmental models have been applied to13N data from barley (Lee and Clarkson, 1986; Siddiqi et al., 1991; Ritchie, 2006), maize seedlings (Presland and McNaughton, 1984), and spruce seedlings (Kronzucker et al., 1995a, 1995b). Additionally, the tracer efflux kinetics of 13N-labeled ammonium have been examined using compartmental analysis in the roots of barley (Britto and Kronzucker, 2003), maize seedlings (Presland and McNaughton, 1986), spruce seedlings (Kronzucker et al., 1995c, 1995d), and rice (Wang et al., 1993a; Kronzucker et al., 1998), as well as in leaf segments of wheat (Britto et al., 2002). Kinetic models that parameterize nutrient uptake have also been developed based on 13N-labeled nitrate influx measurements in barley roots (Lee and Drew, 1986) and 13N-labeled ammonium influx in rice roots (Wang et al., 1993b). Each of these experiments combined the use of 13N-labeled radiotracers with rigorous mathematical treatment to extract meaningful information about nitrogen flow in a particular region of an intact plant.

Oxygen-15 (15O) is another short-lived radioisotope that decays by positron emission; its radioactive half-life is 2.03 min. Generally, a water source (H215O) is produced and introduced to the plant through the root bathing solution. Gamma-ray detectors (or a positron emission imaging system) are then used to monitor radiotracer accumulation in sections of the plant to observe water transport (Kiyomiya et al., 2001a; Nakanishi et al., 2003, Tanoi et al., 2005). Due to its very short half-life, 15O is only useful for tracing phenomena occurring on a short time scale. However, the longer-lived isotope fluorine-18 (18F; 109.8 min radioactive half life) has been used as a proxy for tracing the dynamics of water transport because fluorine ions bind readily to water molecules (Kume et al., 1997; Nakanishi et al., 2001c). The prolonged half-life of 18F makes it a more attractive candidate for measuring longer-term phenomena, although 18F labeling likely tracks the movement of fluorine ions more so than water molecules (Nakanishi et al., 2001b). In addition, MRI offers an alternative for measuring the long-term dynamics of water transport in plants (Windt et al., 2006; Van As, 2007).

The dynamic information obtained from radiotracer experiments is used to investigate time-dependent changes within the labeled plant. Short-lived radiotracer experiments with 11CO2 use either pulse-labeling, where 11CO2 gas is supplied to a portion of the plant in a short burst (pulse), or continuous labeling, where the 11C activity in the labeling system is kept fairly constant by supplying 11CO2 at regular intervals (Thorpe and Minchin, 1991) or by a continuous production system (Magnuson et al., 1982). The continuous labeling technique is particularly useful for studying diurnal patterns and other time-dependent plant responses, such as those due to environmental changes (e.g., shading; Thorpe and Minchin, 1991). Pulse-labeling can also be used to measure metabolite dynamics in plants. For example, time-dependent analysis techniques are applied to radiotracer data obtained from pulse-labeling experiments to determine the plant response during the labeling period (e.g., Minchin and Grusak, 1988). Alternatively, the environmental conditions of the plant can be modified between pulse-labeling periods or similar plants grown in different environmental conditions can be pulse-labeled to measure plant responses.

Long-time scale measurements with isotopic analysis techniques

The use of short-lived positron emitters provides the ability to perform real-time substance accumulation and flow measurements in vivo. However, a few important constraints should be considered when designing experiments that use short-lived radioisotopes. First, the short radioactive half-life requires that experiments be performed near the isotope production facility. Second, its short radioactive half-life limits the dynamic phenomena that can be observed to those with characteristic time constants on the order of a few hours. Last, high initial radioactivity is needed to observe the radiotracer transport and allocation over long periods of time (e.g., nine half lives for 11C), so sufficient radiation shielding must surround the labeling region.

For measuring carbon dynamic processes of a longer time scale than achievable with short-lived radioisotopes, measurement techniques based on the stable 13C isotope or the long-lived 14C radioisotope can be used. However, determination of 13C accumulation in plant tissue requires destructive harvesting of the labeled plant for mass spectrometry. There are also two major drawbacks with 14C labeling: (1) due to the long half-life, a single plant cannot be labeled multiple times, and (2) the low energy beta particle emitted from 14C decay has a small probability of escaping plant tissue thereby drastically reducing the number of cases where in vivo counting techniques can be used. For example, detection of the 14C beta particles in plant leaves has been used in autoradiography studies of phloem loading, unloading, and transport (Fritz et al., 1983; Turgeon, 1987; Turgeon and Wimmers, 1988). While beta particles emitted in 14C decay may escape a thin leaf, they will likely be absorbed by thicker shoot or root tissue. Thus, the labeled plant must be destructively harvested at the end of a labeling period, and 14C accumulation is quantified by either detecting the beta particles emitted from various plant tissues or by accelerator mass spectrometry (Reglinski et al., 2001). The 14C-radio-labeled plant tissue has also been sampled destructively for studies of carbon allocation of particular metabolites (e.g., phenolics; Margolis et al., 1991). These methods provide information about carbon allocation but give no insight into carbon transport dynamics in the same plant.

Development of data analysis techniques

Over the last 30 years, the considerable advancements made in gamma-ray detection, imaging, and analysis techniques have enabled high precision quantitative studies of plants using short-lived radioisotopes. The pioneering work of Peter Minchin and colleagues (e.g., Minchin and McNaughton, 1984; Minchin and Thorpe, 1987, 1989) established the foundation for this field using collimated single detectors. One of Minchin’s most important contributions was the development of analysis techniques that provide the framework for quantitative interpretation of tracer profiles. Tracer profiles are measurements of the spatial distributions of radiotracer inside the plant as a function of time. Using a statistical analysis derived from transfer functions in physics, Minchin developed an input-output model to determine properties of the transport system tracer profile data (Minchin, 1978). The transfer function describes the change in shape of the tracer profile between the system input and output and provides an alternate description of the system that can be used to calculate the output response for any given input (Cadzow, 1973, Ch.7). This type of analysis makes no assumptions about the physical mechanisms involved but allows physiologically relevant parameters to be calculated (Minchin and Troughton, 1980). Transfer function analysis has been applied to many sets of 11C tracer profile data to extract physically meaningful information about carbon allocation and transport in plants. Because input-output models provide a mathematical description of the data and physically relevant parameters, any mechanistic model should be consistent with the statistical modeling results.

In addition to transfer function analysis, mechanistic models have been used to describe radiotracer transport and allocation. Minchin et al. (1993) applied a transport-resistance (TR) model proposed by Thornley (1972; reviewed by Minchin and Lacointe, 2005) to explain source-sink dynamics using 11C radiotracer data. The TR model is based on Münch’s original hypothesis that photoassimilate flow is driven by an osmotically generated pressure gradient. Bancal and Soltani (2002) extended this model to consider the source term as an activity of solute production rather than a compartment concentration and to include changes in sap viscosity. The TR model does not incorporate all the intricacies of the transport system, but it does provide sufficient mechanistic detail to describe the phenomena observed in whole-plant experiments. In fact, Thornley (1998) suggests that a TR model needs to be the starting point for all more complex models, as this incorporates the only two significant processes, transport and chemical conversion, that result in allocation.

Mechanistic models of phloem transport can be used to fit tracer profile data and estimate physical parameters (e.g., Moorby et al., 1963), but these models may assign unnecessary complexity to the system. Compartmental analysis (e.g. Fares et al., 1988) considers the flow of carbon through a series of partitions of characteristic kinetics, so it does not assume any explicit mechanism for phloem transport. However, compartmental analysis does provide physiological parameters that can be directly compared to those predicted by mechanistic models (e.g., Moorby and Jarman, 1975). Detailed mathematical models of phloem transport have been proposed (e.g., Goeschl et al., 1976; Daudet et al., 2002; Thompson, 2006); these have not been directly compared to radiotracer data, but their predictions can be compared to the physiologically relevant parameters obtained using nonmechanistic analysis methods.

11C LABELING AT DUKE UNIVERSITY

The first plant studies using short-lived radioisotopes at Duke University were performed in the 1980’s. These took advantage of the close proximity of the Duke University Plant Growth Facilities (Phytotron) and the Triangle Universities Nuclear Laboratory (TUNL). The 11C was produced using the TUNL 4 MeV Van de Graaff accelerator. A beam of 3He nuclei was directed on a 12CO2 flowing gas target to produce 11CO2 continuously via the 12C+3He→11C+4He(Q=+1.86 MeV) reaction (Magnuson et al., 1982). Later, 11CO2 was also produced at the Duke University Medical School Cyclotron and transferred to the Phytotron using a shielded transporter (McKinney et al., 1989) for pulse-labeling experiments. With improved technology a new initiative is under way to study plants using short-lived radiotracers at Duke University. The initial focus of the research program is to measure physiological responses of plants to environmental changes and to measure the rates of physiological processes that are important for plant growth. In this research, 11C is produced with the TUNL FN tandem Van de Graaff accelerator by bombarding a nitrogen (N2) gas-filled target cell with an energetic (∼10 MeV) beam of protons for about 30 min. This radioactive-substance production method is based on the 14N+p→11C+4He(Q=−2.92 MeV) reaction that was used by Jahnke et al. (1981). We prefer this reaction over the 10B+d→11C+n(Q=+6.46 MeV) reaction, which is commonly used with low-energy electrostatic accelerators, because it can be implemented more easily and with a higher efficiency for producing 11C tagged carbon dioxide. For example, we produce 25 milliCuries of 11CO2 in 30 min with 1.5 μA of proton beam on a nitrogen gas target compared to 10 milliCuries produced by Minchin and colleagues (More and Troughton, 1973) by bombarding a 10B target with 30 μA of deuterons for the same length of time.

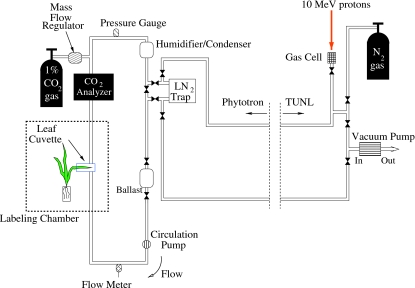

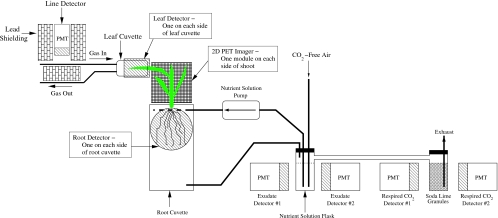

A schematic diagram of the recently developed 11CO2 radiotracer gas system at Duke University is shown in Fig. 2. The 11CO2 gas is produced in the tandem accelerator laboratory at TUNL, and the plant labeling measurements are performed at the Duke Phytotron in a specially modified environmental growth chamber. The present system provides researchers with pulse-loading capability and was designed to make upgrading for continuous loading measurements straightforward. The 11CO2 gas is produced by bombarding a target cell pressurized to 7.8 atmospheres with research-grade N2 gas with a proton beam. The contents of the production cell, which is N2 gas with a minute mixture of radioactive tagged gases, is transferred through tubing in an underground conduit approximately 100 m to the labeling system in the Phytotron. In a typical isotope production run the proton beam is kept on the target gas cell for about 30 min. The main radioactive gases produced in the process are 11CO, 11CO2, and 14O tagged O2. The 14O is produced by the 14N+p→14O+n reaction (Q=−5.93 MeV). It decays by positron emission with a radioactive half life of 1.2 min compared to the 20.3 min half life of 11C. After a production run the radioactive gas mixture in the target cell is slowly pumped through a liquid-nitrogen cooled trap where the CO2 is frozen, the O2 is liquefied and the N2 and CO gases are vented into a high-flow gas exhaust system in the tandem accelerator laboratory. Though not shown in Fig. 2, the LN-cooled trap is inside a 4-in.-thick lead shielding enclosure. Most of the 14O that is trapped along with the CO2 decays before the gas is loaded into the labeling loop. The nominal activity of trapped 11CO2 at the beginning of each labeling period is about 30 milliCuries (∼109 decays per second). After warming the trap to room temperature, the 11CO2 gas is injected as a pulse into the labeling loop. The loop contains diagnostic instrumentation and control components, as well as a temperature-controlled leaf cuvette (Fig. 2). The 11CO2 is mixed with air in the closed loop and introduced to the plant by flowing the air over a leaf that is in a sealed cuvette. The concentration of the labeled 11CO2 is negligible compared to the controlled atmospheric [12CO2]; at the beginning of a labeling measurement the ratio of 11CO2 to 12CO2 molecules is about 1:109. The 11CO2 is metabolized via photosynthesis into 11C-labeled photoassimilates that are tracked through the plant. The radiotracer experiments take place inside a controlled-environment growth chamber at the Phytotron that allows for maintenance of abiotic factors such as temperature (12°–35° C when fully lit and 2°–30° C when dark), light intensity (up to 350 μmol m−2 s−1 photosynthetically active radiation), and atmospheric CO2 concentration (200–1000 μmol mol−1). The chamber can replicate growth conditions of the plant in its natural environment and∕or its experimental growth conditions, or it can be adjusted to a novel environment for short-term acclimation experiments.

Figure 2. 11CO2 production, transport and, labeling system at Duke University.

The 11CO2 gas is produced in the tandem accelerator at TUNL (p+14N→11C+4He) and transferred to the Duke University Phytotron via tubing in underground conduits. 11CO2 gas from the target cell is collected in a lead-shielded liquid nitrogen cooled trap at the Phytotron. Other gases (mostly nitrogen and carbon monoxide) from the target cell are pumped back through the exhaust system at TUNL. The present system has pulse-loading capability only. A pulse of 11CO2 gas is introduced into the labeling loop by warming the CO2 trap to room temperature and opening the valves that isolate the trap from the loop so that the air in the loop flows through the trap, thereby mixing with the radioactive 11CO2 gas.

Development of low spatial resolution 2D PET imaging

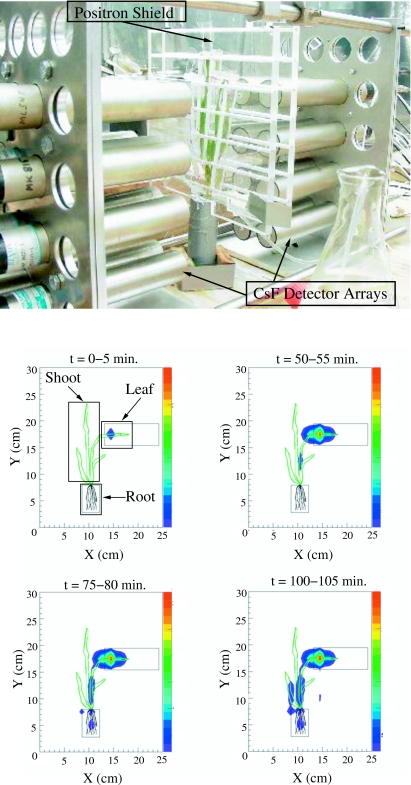

To gain experience with PET measurement techniques for plant applications and to develop image reconstruction software and quantitative data analysis tools, a prototype two-dimensional (2D) planar PET imager was constructed using existing hardware at TUNL. This prototype imager is composed of two planar arrays of cylindrical cesium fluoride detectors (25 mm diameter×45 mm thick), with each array containing 10 detectors (Fig. 3). This arrangement provides a spatial resolution of about 1 cm in both the horizontal and vertical directions over a field of view (FOV) of approximately 12 cm (width) ×20 cm (height). The dimensions of the imager and the detector positions within each array were chosen to cover a specific FOV while also providing smooth geometric detection efficiency across the image plane. The image plane is located midway between the parallel planes defined by the front surfaces of the detector arrays. Coincidence detection of the back-to-back gamma rays emitted from electron-positron annihilation is used to initiate the recording of information associated with the decay of 11C nuclei inside the plant tissue. The density distribution of the electron-positron annihilation sites is reconstructed on the image plane using the detector hit pattern data that are stored for each coincidence event. The source of the gamma rays for each event is projected onto the image plane at the point where the line connecting the centers of the two detectors involved in the coincidence intersects the image plane. The count for each event is distributed over several pixels in the image plane using a spatial probability distribution function that accounts for the finite size and the geometric arrangement of the detectors. Each event is recorded with a time stamp thereby providing the capability of tracing substance flow between any regions within the imager FOV. The information available from the images is limited spatially by the resolution of the imager and temporally by the period of time needed to accumulate adequate counting statistics in the regions of interest.

Figure 3. (Above) Photograph of a barley plant arranged within the FOV of the low spatial resolution 2D PET imager.

Each detector cylinder is a cesium fluoride scintillator with dimensions 25 mm diameter by 45 mm thick. A plastic shield equipped with ventillation ducts is placed near the plant surface to stop positrons that escape from the plant tissue so that they annihilate within the imager FOV. Individual barley leaves are also separated with plastic shields to ensure that positron annihilation occurs locally. (Below) Snapshots indicating 11C-labeled photoassimilate accumulation in a barley plant as a function of time. The integration time for these images is 5 min; the minimum exposure time is imposed by the counting rate of the detector system and the minimum required counting statistics within each region of interest. The relative intensity of the source in the image plane is coded according to the color scale on the right side of each frame with red representing the brightest pixels. The images are corrected for background radiation, radioactive decay of 11C, and the detection efficiency as a function of location in the image plane. In the first frame (0–5 min), the regions of interest (leaf, shoot, and root, as indicated by the rectangular boxes) are selected for direct comparison to earlier collimated detector measurements.

Trade-offs between spatial resolution and the area of the FOV are often necessary to make the final cost of the imager fit budget constraints. For example, the positron-emitting tracer imaging system (PETIS) developed at the Japan Atomic Research Institute was first used to measure uptake and transfer of 18F in soybean with 2.5 mm spatial resolution in a 6 cm×5 cm FOV (Kume et al., 1997). While this spatial resolution is four times finer than that of the Duke prototype PET device, the imaging area is reduced by about a factor of 8. Since this original application, the PETIS device has been used to visualize translocation of 11C-labeled methionine in barley (Nakanishi et al., 1999), 13N-labeled nitrates in soybean plants (Ohtake et al., 2001), 13N-labeled ammonium in rice (Kiyomiya et al., 2001b), and 15O-labeled water in soybean plants (Nakanishi et al., 2001a). The primary limitation of the original PETIS was the small FOV. By adding two pairs of detector modules with dimensions similar to the original instrument, the PETIS detection area was increased to approximately 5 cm×15 cm (Keutgen et al., 2005). More recently, the FOV of PETIS has been increased to roughly 14 cm×21 cm (Kawachi et al., 2006). In addition, the Institute of Chemistry and Dynamics of the Geosphere Phytosphere research group in Germany has developed a three-dimensional (3D) imaging system for plant studies, the Plant Tomographic Imaging System or PlanTIS (Streun et al., 2007). The PlanTIS device has a cylindrical geometry that provides 1.3 mm resolution with an axial FOV of about 11 cm (Streun et al., 2006, 2007).

The Duke prototype PET imager has been used to measure allocation of 11C-labeled photoassimilates in small plants for studies examining limitations of photoassimilate export in elevated CO2 environments. The uptake leaf, shoot, and roots are all visible within the detector FOV, thereby enabling coherent tracing of 11C throughout an entire plant. Images are reconstructed by integrating the events accumulated during a specific exposure time. For example, the images shown in Fig. 3 are 5-min-long exposures. The duration of each exposure is limited to the time required to yield a statistically significant number of detected events from each region of interest. This integration time can be adjusted to provide finer temporal resolution as long as the counting statistics for each region of interest remain adequate. The counting statistics can be improved by moving the detector arrays closer together, increasing the initial 11C activity, or selecting larger regions of interest. While the spatial resolution of the instrument is fixed by the detector geometry, the temporal resolution can vary depending on the particular application but is fundamentally limited by the time-stamp clock frequency.

Determination of 11C profiles using PET-based methods requires image construction from raw coincidence event data. The analysis involves ray tracing to determine the location of the event vertex and correcting the raw data for geometric and gamma-ray detection efficiencies using Monte Carlo simulations of the imager-plant setup. These analysis techniques are well proven and comparisons of simulations to independent benchmark data for a particular experimental setup provide checks for implementation mistakes and assessments of systematic errors. We used the results of collimated single-detector measurements as the standard to which our PET-based data were compared. The single-detector method was chosen as the standard because it measures 11C profiles directly, i.e., without the complexities of event reconstruction. Verification of the PET-based measurement techniques using single-detector benchmark data was carried out in two steps.

First, collimation techniques were used to determine carbon allocation on a coarse spatial scale by measuring 11C accumulation in three regions of barley (Hordeum distichum L.) plants: the uptake leaf, the shoot, and the root. Barley plants were chosen because of their successful use in previous radiotracer studies of carbon transport and allocation (e.g., Thorpe and Minchin, 1991). Each region was viewed by a single collimated bismuth germanate (BGO) detector. The collimators were made of small lead shielding blocks that were arranged to define the FOV of each detector to a specific region of the plant. This detector arrangement is commonly used for 11C-labeled photoassimilate tracking (Minchin and Thorpe, 2003; Schwachtje et al., 2006) and gives results with only minor processing of the raw data. Because only one of the emitted gamma rays from electron-positron annihilation in the plant tissue is detected, each region of interest is defined solely by the geometry of the lead shielding. Tracer profiles from the collimated detector measurements were analyzed using an input-output statistical model (Minchin, 1978). The physical parameters that result from this analysis are the system gain (fraction of the input that arrives at the output) and the average transit time, which is used to calculate the average photoassimilate velocity (Minchin and Troughton, 1980). With our detection system, both leaf and shoot exports were evaluated, thereby enabling the determination of the fraction of 11C allocated to each section of the plant (partitioning fraction).

Second, results from the event reconstruction and analysis of data taken with our 2D imager were compared with data obtained from the collimated single-detector measurements that were made as described above. The imaging measurements were made on barley plants similar in age and growth conditions as those used in the collimation experiments. The barley seedlings were labeled with 11CO2, and the 11C-photoassimilates were tracked throughout the entire plant using the low resolution prototype imager. To enable direct comparisons between the results obtained with the two techniques the regions of interest within the imager FOV were chosen to match the regions measured in the collimated detector experiments. Time series snapshots with exposure times of 5 min, as shown in Fig. 3, were used to trace the accumulation of 11C in the barley seedlings. The regions of interest, which are the uptake leaf, the shoot, and the root, are indicated by the rectangles in the first image frame. Tracer profiles for each region of interest are generated by integrating the image pixel values within the region for all corrected exposure images. The input-output statistical model was applied to the tracer profiles obtained from the image data to provide information about leaf and shoot export. The leaf export analysis quantifies the flow of photoassimilate out of the uptake leaf and into the shoot and roots. Similarly, the shoot export analysis describes the flow of radiotracer from the shoot to the roots. The statistical input-output methods were developed for use with individual detectors collimated to monitor photoassimilate accumulation in terminal sinks of the plant as well as the entire organism. However, these same techniques can be applied to 2D PET images without gaps between the detection regions as is often the case in collimated detector measurements; electronic definition of the region of interest and integration of pixels in the 2D images enables spatial continuity in the substance flow analysis. The advantages of the imaging technique are improved spatial resolution and the ability to quantify radiotracer flow between any physiologically relevant regions of interest in the image plane. The application of input-output modeling to tracer profiles from 2D PET images has previously been demonstrated with PETIS (Keutgen et al., 2002;Keutgen et al., 2005; Matsuhashi et al., 2005).

The patterns of carbon partitioning obtained from the measurements made with the prototype 2D PET imager are consistent with the results from our collimated detector measurements (Table 2), thus validating the image reconstruction and analysis techniques applied to the 2D PET imaging data. Uncertainties in the partitioning fractions determined from our collimated detector data are primarily due to variations within an individual plant as was assessed by labeling the same plant multiple times. The somewhat larger errors in the partitioning fractions determined using the 2D PET imager reflect both variation within an individual plant and differences between plants; the PET-based data were accumulated using several plants, not just one as was used in the collimated detector measurements.

Table 2.

Comparison of the results of our carbon partitioning measurements made using collimated detection to those obtained with our prototype 2D PET system. Both measurement methods were applied on barley seedlings that were 10–12 days old. These seedlings were grown and labeled at a CO2 concentration of 350 ppm. The errors in the measured quantities are mostly due to systematic uncertainties. In both methods the statistical uncertainties were generally a factor of 10 smaller than the systematic errors.

| Measurement method | Labeled leaf fraction | Shoot fraction | Root fraction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collimated detectors | 0.35±0.02 | 0.45±0.04 | 0.20±0.03 |

| Prototype 2D PET | 0.34±0.10 | 0.52±0.08 | 0.14±0.03 |

High spatial resolution 2D PET imaging: VIPER

The 2D PET imaging technique is applicable to a broad range of spatial scales with the achievable spatial resolution mostly dependent on the size of the individual detector elements. A high spatial resolution 2D PET imager composed of two 5 cm×5 cm detector modules was designed at Duke University to provide greater spatial detail. Each module consists of a planar array of pixelated BGO crystals (15×15) coupled to a position-sensitive photomultiplier tube (PSPMT) with the associated position calculating circuitry. The dimensions of each BGO pixel are 3 mm (wide) ×3 mm (high) ×25 mm (thick), and adjacent pixels are optically decoupled by a 0.25-mm-thick reflective material. These crystals are coupled to a PSPMT with 8×8 anode pads and an active area of 49 mm×49 mm. To reduce the number of analog-to-digital conversion channels required for BGO pixel identification within each module, position-calculating circuit boards are mounted onto the PSPMT. This arrangement reduces the number of readout channels for each module from 64 (8×8) anode signals to four position signals (X+, X−, Y+, and Y−) (Popov et al., 2001). Because the modular design of this system makes it highly adaptable to a wide variety of geometries in plant studies, we refer to it to as the Versatile Imager for Positron Emitting Radiotracers (VIPER).

The Duke VIPER is similar to the PETIS instrument that was developed at the Japan Atomic Energy Research Institute. Both devices have a FOV of approximately 5 cm×5 cm, although the PETIS imager employs finer scintillator segmentation (2 mm×2 mm×20 mm BGO scintillator pixels). The PETIS was recently used to visualize the accumulation of photoassimilates in grains of a wheat ear (Matsuhashi et al., 2006) with 2.3 mm resolution. Finer detector segmentation can provide better spatial resolution in an ideal situation, although the actual spatial resolution is generally degraded by positron range effects. For positrons emitted by 11C decay in wet tissue, the average distance the positron travels before annihilation is about a millimeter. However, positrons near the surface of the plant may escape and travel up to 4 m in air before annihilating. To ensure positron annihilation as close to the decaying 11C nucleus as possible, a plastic shield is placed near the surface of the plant to supply an annihilation medium (Minchin and Thorpe, 2003). The plastic shield increases detection efficiency since positrons that could have otherwise escaped are stopped within the detection FOV. However, overall spatial resolution is degraded due to the increased distance allowed between the location of the 11C nucleus and the site of electron-positron annihilation. This trade-off between the efficiency for detecting the positron annihilations and spatial resolution is required to ensure that all positrons emitted within the FOV are accurately counted.

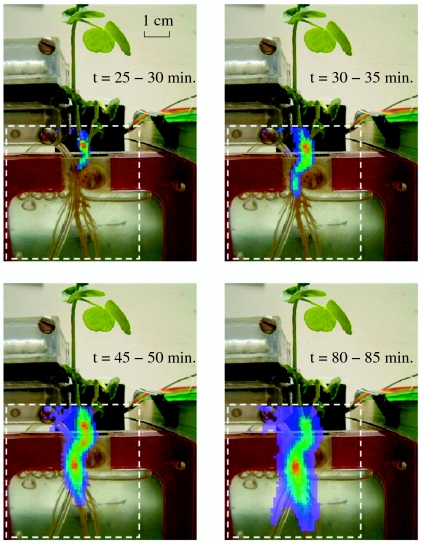

The capabilities of the VIPER have been demonstrated using both 11C and 13N radiotracers. The ability to measure carbon accumulation as a function of position within the VIPER FOV was demonstrated by tracking the distribution of 11C-labeled photoassimilates in a 5 cm×5 cm region of a germinated bean (Pisum sativum L.) seedling (Fig. 4). In these measurements the labeled leaf was sealed in a cuvette into which air with a mixture of 12CO2 and 11CO2 flowed. The labeling cuvette was located above the imager FOV and the roots were placed in a hydroponic rectangular container. For the images shown in Fig. 4, the FOV of the VIPER included the shoot and the upper portion of the roots. The integration time for each frame in Fig. 4 was 5 min. Note that tracer accumulation is first detected in the lower shoot region about 25 min after 11CO2 is introduced to the labeled leaf. This delay is the time required for 11CO2 assimilation in the leaf and the subsequent transport of photoassimilates out of the leaf and through the upper portion of the shoot. The 11C-labeled carbohydrates are then transported around the seed cotyledon and down into the upper root region. Though most of the 11C accumulation is observed in the primary root possibly for storage, significant accumulation is measured in a fine root after about 80 min of labeling (seen just to the left of the bubbling tube in Fig. 4) suggesting lower C allocation priorities in the fine active roots. The series of images demonstrates the ability of the VIPER to reconstruct the distribution of 11C-labeled photoassimilates with high spatial resolution in a 5 cm×5 cm FOV.

Figure 4. Snapshots taken with VIPER of accumulation of 11C-labeled photoassimilates in the lower shoot and root of a bean plant as a function of time.

The images are obtained by coincidence detection of the back-to-back gamma rays emitted from positron annihilation in the plant. The dashed square indicates the VIPER FOV, and each image pixel is 1 mm×1 mm. The integration time for these images is 5 min for demonstration purposes, but the exposure time can be decreased to 1 min, which is the limit imposed by the counting statistics within each region of interest for this particular setup.

Measurement of transport properties in the translocation of nitrogen ions from the root bathing solution to the foliage of a barley plant has also been carried out successfully with the VIPER. Here, nitrate ions were produced at TUNL by bombarding a depleted water target (H2O with 99.99% 16O) with a proton beam. This process results in an aqueous solution of 13N nuclei that are >90% . Nitrite and ammonium ions are also produced in the solution in small quantities (Chasko and Thayer, 1981). The 13N-labeled solution was added to the root hydroponic solution, and 13N-labeled ions were assimilated in the roots and transported to plant sinks. The 13N in the roots was monitored using coincidence counting, and the VIPER was used to visualize 13N accumulation in two leaves of a barley plant. After about 15 min the 13N-labeled compounds were detected in leaves located about 6 cm above the shoot-root interface (data not shown).

Hybrid detection system with low and high spatial resolution techniques

The integration of coincidence counting with high resolution 2D PET imaging is an efficient and effective approach to studying entire plants and plant systems where a large or distributed FOV is required. The types of experiments that can currently be performed with high spatial resolution are primarily limited by the FOV covered by imaging devices with resolution finer than about 3 mm. Though high spatial resolution is desired in many instances, some regions of interest for the overall analysis may not require detailed spatial information. These regions can be monitored separately using coincidence counting with nonsegmented detectors.

Combining high spatial resolution imaging with coincidence counting to form a hybrid radiotracer system requires an accurate determination of the relative detection efficiency for each detection region. The relative detection efficiency for each region of our hybrid system is determined by placing a positron-emitting source at the center of each FOV and measuring the decay-corrected count rate. The positron-emitting source is a granule of soda lime that has absorbed 11CO2 gas. Monte-Carlo simulations are used to calculate the relative detection efficiency as a function of position across each FOV. The simulation for the VIPER is normalized to the efficiency of the other detector pairs in the system using the measurements made with the soda-lime source. For regions monitored by nonsegmented detectors, the measured relative detection efficiency is scaled by the average calculated detection efficiency across the FOV. Once corrections for background radiation, radioactive half-life, and relative detection efficiency have been applied, quantitative determinations of material flow throughout the entire system can be made.

An example of experiments being performed at Duke University that takes advantage of a hybrid detection system is the measurement of total carbon allocation and translocation, including root exudation and root respiration under various environmental conditions. Coincidence counting is utilized to monitor accumulation of 11C-photoassimilates in the labeled leaf and roots; it is also used to monitor the exudation of soluble 11C-labeled compounds from the roots and 11CO2 gas that is respired by the roots. The quantity of radiotracer released from plant roots in the form of soluble exudates or respired carbon dioxide gas is measured by circulating the root bathing solution in a closed system (Fig. 5). The flow of the circulated solution transports soluble exudates out of the rhizosphere and into a flask where a detector monitors radiotracer accumulation within a sample of the well-mixed solution. This experimental design is a modification of the setup used by Minchin and McNaughton (1984). While high spatial resolution imaging is not required to monitor the root exudation and respiration flasks, it is needed in the shoot region to enable measurement of material flow in regions of interest within the shoot as well as carbon allocation analysis on a coarse spatial scale (i.e., leaf, shoot, and root). Better spatial resolution can elucidate relative sink strengths, such as reloading of photoassimilate into a region of the shoot adjacent to the labeled leaf rather than root allocation.

Figure 5. Diagram of an experiment that uses the hybrid detector system to measure full-plant carbon partitioning dynamics as well as root exudation and root respiration.

The root exudation and respiration are measured by circulating the root bathing solution in a closed loop. The 11C accumulation in the labeled leaf and root is monitored via coincidence counting instead of imaging because high spatial resolution is not required in these regions. Coincidence counting is also used to monitor 11C-labeled root exudates and 11CO2 respired from the roots. VIPER is used to measure 11C accumulation in the shoot of the plant.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

To coherently trace short-lived positron-emitting isotopes throughout an entire plant seedling or parts of a larger plant with high spatial resolution, detector modules similar to the ones in the current small FOV imagers can be tiled into planar arrays. This concept has driven the development of a large FOV imager at Duke based on tiled arrays of the VIPER module. The proposed imager is composed of 4×6 detector modules in each array, covering a FOV approximately 20 cm wide ×30 cm tall. The primary benefit of this modular design is the flexibility it provides. The modules may be rearranged within the detector array frame to accommodate various plant geometries while covering a total imaging area of 600 cm2. This type of flexibility is not a standard feature of commercially available PET imaging devices. Hamamatsu Photonics has constructed and demonstrated the capabilities of an imaging system with a FOV approximately 12 cm wide ×19 cm tall and a spatial resolution of 2 mm (Uchida et al., 2004; Kawachi et al., 2006), and PlanTIS provides 3D images with a spatial resolution of 1.3 mm (Streun et al., 2007). Though these systems currently have the largest coverage areas of any high spatial resolution PET imaging systems with demonstrated plant applications, they do not offer the flexibility of the planned Duke imager.

Imaging and quantitative analysis of the dynamic transport of metabolites using radiotracers will improve our understanding of the complexity of controls on plant growth and development in changing environments. Measurement of radiotracer transport and allocation over a large FOV with high spatial resolution will provide information on fine-scale dynamics that is not accessible using other techniques. For example, characterization of gene function for whole-plant transgenics can be monitored in dynamic light environments, in soils with heterogeneous nutrient availability or water pulses, or after insect or pathogen attacks. The technique can be used for screening different genotypes for particular traits likely to improve plant growth. Additionally, imaging techniques will provide data to parameterize and test plant growth models from the plant-soil interface (e.g., root exudates-microbe interactions) to the physiological limitations of source-sink carbohydrate loading in future elevated CO2 environment or in polluted air, whole-plant dynamics of carbon allocation as mediated by nitrogen, and whole-plant hydraulics in fluctuating environments. The variety of plants species used and their different growth stages requires a versatile imaging system made up of both high and low spatial resolution components that provides the opportunity to observe the spatiotemporal dynamics of metabolites on multiple scales. In addition to providing physiological information, versatile radiotracer imaging systems can also be used to provide a better understanding of metabolite dynamics on an ecological scale, such as insight into plant-fungal interactions or responses to herbivory.

CONCLUSIONS

The collaboration of scientists across multiple disciplines provides the expertise to study the responses of plants to environmental changes using radioisotopes. Measurements with short-lived positron-emitting isotopes have led to a better understanding of basic physiological and ecological phenomena. The development of quantitative analysis methods for tracer profiles has been crucial to the interpretation of measurements using short-lived radioisotopes. Statistical input-output models do not require a priori knowledge of the mechanisms driving tracer transport, but physiologically meaningful parameters can be determined from data using this model, thereby providing consistency checks on mechanistic interpretations of certain phenomena. The recent application of PET techniques for plant research allows for observation of real-time metabolite dynamics on previously unexplored spatial scales and creates opportunities for new discoveries. At the subcellular scale, the increased knowledge of genomes for various species combined with the spatio-temporal measurements made possible by new radiotracer techniques could help identify gene function in an environmental context. At the other end of the spatial scale, i.e., plant-organism interactions, the technique has promise in helping to elucidate the dynamics of short-term energy and nutrient fluxes between organisms.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank anonymous reviewers for their insightful and constructive feedback. Thank you to Peter Minchin for helping us get started with short-lived positron emitting radiotracer labeling. Also, many thanks to Stan Majewski and the Detector and Imaging Group at Jefferson Lab for providing the position calculation circuit boards for the prototype VIPER imager and to Emily Bernhardt for her insightful suggestions during the early stages of this collaboration. Thank you as well to Todd Smith at the Phytotron and Bret Carlin, John Dunham, David Hoyt, Patrick Mulkey, Richard O’Quinn, and Chris Westerfeldt at TUNL for their technical assistance. Funding for this research is provided by the US Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Nuclear Physics, Grant No. DE-FG02-97ER41033 (TUNL), the National Science Foundation (NSF), Grant No. IBN-9985877 (Phytotron), and the NSF, Grant No. DBI-0649924.

References

- Ananyev, G, Kolber, Z S, Klimov, D, Falkowski, P G, Berry, J A, Rascher, U, Martin, R, and Osmond, B (2005). “Remote sensing of heterogeneity in photosynthetic efficiency, electron transport and dissipation of excess light in Populus deltoides stands under ambient and elevated CO2 concentrations, and in a tropical forest canopy, using a new laser-induced fluorescence transient device.” Glob. Chang. Biol. 11, 1195–1206. [Google Scholar]

- Babst, A B, Ferrieri, R A, Gray, D W, Lerdau, M, Schlyer, D J, Schueller, M, Thorpe, M R, and Orians, C M (2005). “Jasmonic acid induces rapid changes in carbon transport and partitioning in Populus.” New Phytol. 167, 63–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, D L, Carp, J S, and Surti, S (2003). Positron Emission Tomography: Basic Science and Clinical Practice, pp 41–67, Springer-Verlag, London. [Google Scholar]

- Bancal, P, and Soltani, F (2002). “Source-sink partitioning. Do we need Münch?” J. Exp. Bot. 10.1093/jxb/erf037 53, 1919–1928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, H T, Thompson, R G, Aikman, D P, and Fensom, D S (1986). “Fine structure aberrations in the movement of 11C and 13N in the stems of plants.” J. Exp. Bot. 37, 1780–1794. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, S M, Orlando, D A, Lee, J, Wang, J Y, Koch, J, Dinneny, J R, Mace, D, Ohler, U, and Benfey, P N (2007). “A high-resolution root spatiotemporal map reveals dominant gene expression patterns.” Science 318, 801–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britto, D T, and Kronzucker, H J (2003). “Trans-stimulation of efflux provides evidence for the cytosolic origin of tracer in the compartmental analysis of barley roots.” Functional Plant Bio. 30, 1233–1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britto, D T, Siddiqi, M Y, Glass, A DM, and Kronzucker, H J (2002). “Subcellular flux analysis in leaf segments of wheat (Triticum aestivum).” New Phytol. 155, 373–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchwald, P, and Sveiczer, A (2006). “The time-profile of cell growth in fission yeast: model selection criteria favoring bilinear models over exponential ones.” Theoretical Biology and Medical Modelling, 3, 16–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadzow, J A (1973). Discrete-Time Systems, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell, C D, Fensom, D S, Bordeleau, L, Thompson, R G, Drouin, R, and Didsbury, R (1984). “Translocation of 13N and 11C between nodulated roots and leaves in alfalfa seedlings.” J. Exp. Bot. 35, 431–443. [Google Scholar]

- Chasko, J H, and Thayer, J R (1981). “Rapid concentration and purification of 13N-labelled anions on a high performance anion exchanger.” Int. J. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 10.1016/0020-708X(81)90004-1 32, 645–649. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chatziioannou, A F (2002). “PET scanners dedicated to molecular imaging of small animal models.” Mol. Imaging Biol. 4, 47–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavarria-Krauser, A, Nagel, K A, Palme, K, Schurr, U, Walter, A, and Scharr, H (2008). “Spatio-temporal quantification of differential growth processes in root growth zones based on a novel combination of image sequence processing and refined concepts describing curvature production.” New Phytol. 177, 811–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D X, and Coughenour, M B (2004). “Photosynthesis, transpiration, and primary productivity: scaling up from leaves to canopies and regions using process models and remotely sensed data.” Global Biogeochem. Cycles 10.1029/2002GB001979 18, GB4033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cherry, S, et al. (1997). “MicroPET: a high resolution PET scanner for imaging small animals.” IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 10.1109/23.596981 44, 1161–1166. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Daudet, F A, Lacointe, A, Gaudillere, J P, and Cruiziat, P (2002). “Generalized Münch coupling between sugar and water fluxes for modeling carbon allocation as affected by water status.” J. Theor. Biol. 10.1006/jtbi.2001.2473 214, 481–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer, M I, Acra, M A, Wang, G M, Coleman, D C, Freckman, D W, McNaughton, S J, and Strain, B R (1991). “Source-sink carbon relations in two Panicum coloratum ecotypes in response to herbivory.” Ecology 10.2307/1941120 72, 1472–1483. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fares, Y, Goeschl, J D, Magnuson, C E, Scheld, H W, and Strain, B R (1988). “Tracer kinetics of plants carbon allocation with continuously produced 11CO2.” J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 10.1007/BF02035510 124, 105–122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar, G D, Caemmerer, S V, and Berry, J A (1980). “A biochemical model of photosynthetic CO2 assimilation in leaves of C-3 species.” Planta 10.1007/BF00386231 149, 78–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar, G D, O’Leary, M H, and Berry, J A (1982). “On the relationship between carbon isotope discrimination and the intercellular carbon dioxide concentration in leaves.” Aust. J. Plant Physiol. 9, 121–137. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrieri, A P, Thorpe, M R, and Ferrieri, R A (2006). “Stimulating natural defenses in poplar clones (OP-367) increases plant metabolism of carbon tetrachloride.” Int. J. Phytoremediation 8, 233–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrieri, R A, Gray, D W, Babst, B A, Schueller, M J, Schlyer, D J, Thorpe, M R, Orians, C M, and Lerdau, M (2005). “Use of carbon-11 in Populus shows that exogenous jasmonic acid increases biosynthesis of isoprene from recently fixed carbon.” Plant, Cell Environ. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2004.01303.x 25, 591–602. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Field, C B, Randerson, J T, and Malmström, C M (1995). “Global net primary production: combining ecology and remote sensing.” Remote Sens. Environ. 10.1016/0034-4257(94)00066-V 51, 74–88. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fischlin, A, Midgley, G F, Price, J T, Leemans, R, Gopai, B, Turley, C, Rounsevell, M DA, Dube, O P, Tarazone, J, and Velichko, A A (2007). “Ecosystems, their properties, goods, and services.” In Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, Parry, M L, Canziani, O F, Palutikof, J P, van der Linden, P J, and Hanson, C E (eds.) pp 211–272, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- Freckman, D W, Barker, K R, Coleman, D C, Acra, M, Dyer, M I, Strain, B R, and McNaughton, S J (1991). “The use of the 11C technique to measure plant responses to herbivorous soil nematodes.” Funct. Ecol. 10.2307/2389545 5, 810–818. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz, E, Evert, R F, and Heyser, W (1983). “Microautoradiographic studies of phloem loading and transport in the leaf of Zea mays L.” Planta 159, 193–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gest, H (2005). “Samuel Ruben’s contributions to research on photosynthesis and bacterial metabolism with radioactive carbon.” In Discoveries in Photosynthesis, Govindjee, Beatty, J T, Gest, H, and Allen, J F (eds.) pp 131–137, Springer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass, A DM, Thompson, R G, and Bordeleau, L (1985). “Regulation of influx in barley.” Plant Physiol. 77, 379–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goeschl, J D, Magnuson, C E, DeMichele, D W, and Sharpe, P JH (1976). “Concentration-dependent unloading as a necessary assumption for a closed form mathematical model of osmotically driven pressure flow in phloem.” Plant Physiol. 58, 556–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grodzinski, B, Jahnke, S, and Thompson, R (1984). “Translocation profiles of [11C] and [13N]-labeled metabolites after assimilation of 11CO2 and [13N]-labeled ammonia gas by leaves of Helianthus annuus L. and Lupinus albus L.” J. Exp. Bot. 35, 678–690. [Google Scholar]

- Haustein, E, and Schwille, P (2007). “Trends in fluorescence imaging and related techniques to unravel biological information.” HFSP J. 10.2976/1.2778852 1, 169–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himmelbach, A, Iten, M, and Grill, E (1998). “Signaling of abscisic acid to regulate plant growth.” Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London, Ser. B 10.1098/rstb.1998.0299 353, 1439–1444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahnke, S, Stöcklin, G, and Willenbrink, J (1981). “Translocation profiles of 11C-assimilates in the petiole of Marsilea quadrifolia L.” Planta 10.1007/BF00385318 153, 56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, H G, and Morison, J (eds.) (2007). “Imaging techniques for understanding plant responses to stress.” J. Exp. Bot. 58(4), 743–898.17175554 [Google Scholar]

- Kaestner, A, Schneebeli, M, and Graf, F (2006). “Visualizing three-dimensional root networks using computed tomography.” Geoderma 136, 459–469. [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi, N, Sakamoto, K, Ishii, S, Fujimaki, S, Suzui, N, Ishioka, N S, and Matsuhashi, S (2006). “Kinetic analysis of carbon-11-labeled carbon dioxide for studying photosynthesis in a leaf using positron emitting tracer imaging system.” IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 10.1109/TNS.2006.881063 53, 2991–2997. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keutgen, A J, et al. (2005). “Input-output analysis of in vivo photoassimilate translocation using positron-emitting tracer imaging system (PETIS) data.” J. Exp. Bot. 10.1093/jxb/eri143 56, 1419–1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keutgen, N, et al. (2002). “Transfer function analysis of positron-emitting tracer imaging system (PETIS) data.” Appl. Radiat. Isot. 10.1016/S0969-8043(02)00077-5 57, 225–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyomiya, S, et al. (2001a). “Light activates flow in rice: detailed monitoring using a positron-emitting tracer imaging system (PETIS).” Physiol. Plant. 113, 359–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyomiya, S, et al. (2001b). “Real time visualization of 13N-translocation in rice under different environmental conditions using positron emitting tracer imaging system.” Plant Physiol. 10.1104/pp.125.4.1743 125, 1743–1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronzucker, H J, Glass, A DM, and Siddiqi, M Y (1995a). “Nitrate induction in spruce: an approach using compartmental analysis.” Planta 196, 683–690. [Google Scholar]

- Kronzucker, H J, Guy, G UD, Siddiqi, M Y, and Glass, A DM (1998). “Effects of hypoxia on fluxes in rice roots.” Plant Physiol. 10.1104/pp.116.2.581 116, 581–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronzucker, H J, Siddiqi, M Y, and Glass, A DM (1995b). “Compartmentation and flux characteristics of nitrate in spruce.” Planta 196, 674–682. [Google Scholar]

- Kronzucker, H J, Siddiqi, M Y, and Glass, A DM (1995c). “Compartmentation and flux characteristics of ammonium in spruce.” Planta 196, 691–698. [Google Scholar]

- Kronzucker, H J, Siddiqi, M Y, and Glass, A DM (1995d). “Analysis of efflux in spruce roots.” Plant Physiol. 109, 481–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kume, T, et al. (1997). “Uptake and transport of positron-emitting tracer 18F in plants.” Appl. Radiat. Isot. 10.1016/S0969-8043(97)00117-6 48, 1035–1043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lapinskas, P J, Cunningham, K W, Liu, X F, Fink, G R, and Culotta, C (1995). “Mutations in PMR1 suppress oxidative damage in yeast-cells lacking superoxide-dismutase.” Mol. Cell. Biol. 15, 1382–1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, R B, and Clarkson, D T (1986). “Nitrogen-13 studies of nitrate fluxes in barley roots: I. Compartmental analysis from measurements of 13N efflux.” J. Exp. Bot. 37, 1753–1767. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, R B, and Drew, M C (1986). “Nitrogen-13 studies of nitrate fluxes in barley roots: II. Effect of plant N-status on the kinetic parameters of nitrate influx.” J. Exp. Bot. 37, 1768–1779. [Google Scholar]

- Lough, T J, and Lucas, W J (2006). “Integrative plant biology: role of phloem long-distance macromolecular trafficking.” Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 57, 203–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacFall, J S, Johnson, G A, and Kramer, P J (1990). “Observation of a water-depletion region surrounding loblolly pine roots by magnetic resonance imaging.” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 10.1073/pnas.87.3.1203 87, 1203–1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnuson, C E, Fares, Y, Goeschl, J D, Nelson, C E, Strain, B R, Jaeger, C H, and Bilpuch, E G (1982). “An integrated tracer kinetics system for studying carbon uptake and allocation in plants using continuously produced 11CO2.” Radiat. Environ. Biophys. 10.1007/BF01338755 21, 51–65. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis, H A, Delaney, S, Vezina, L P, and Bellefleur, P (1991). “The partitioning of 14C between growth and differentiation within stem-deformed and healthy black spruce seedlings.” Can. J. Bot. 69, 1225–1231. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuhashi, S, et al. (2006). “A new visualization technique for the study of the accumulation of photoassimilates in wheat grains using [11C]CO2.” Appl. Radiat. Isot. 10.1016/j.apradiso.2005.08.020 64, 435–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuhashi, S, Fujimaki, S, Kawachi, N, Sakamoto, K, Ishioka, N, and Kume, T (2005). “Quantitative modeling of photoassimilate flow in an intact plant using the positron emitting tracer imaging system (PETIS).” Soil Sci. Plant Nutrition 51, 417–423. [Google Scholar]

- McKinney, C J, Fares, Y, Musser, R L, Goeschl, J D, Magnuson, C E, and Need, J L (1989). “Transportation system for 11CO2.” Rev. Sci. Instrum. 10.1063/1.1141019 60, 783–786. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McNaughton, G S, and Presland, M R (1983). “Whole plant studies using radioactive 13-Nitrogen: I.” J. Exp. Bot. 34, 880–892. [Google Scholar]

- Minchin, P EH (1978). “Analysis of tracer profiles with applications to phloem transport.” J. Exp. Bot. 10.1093/jxb/29.6.1441 29, 1441–1450. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Minchin, P EH, Farrar, J, and Thorpe, M R (1994). “Partitioning of carbon in split root systems of barley: effect of temperature of the root.” J. Exp. Bot. 45, 1103–1109. [Google Scholar]

- Minchin, P EH, and Grusak, M A (1988). “Continuous in vivo measurement of carbon partitioning within whole plants.” J. Exp. Bot. 39, 561–571. [Google Scholar]