Summary

The need for professional management of dysphagic patients is growing. The scenario of patient care settings spans from the acute ward to chronic care facilities or home, requiring a health care network able to integrate hospital and community resources and optimise human and instrumental resources. This is also valid for Swallowing Centres, where admission, management, treatment and follow-up of discharged patients are a priority. The complexity of symptoms and the specificity of the underlying disease require a multidisciplinary approach to the patient. The coordinator of the Swallowing Centre is a phoniatrician working together with a logopedist. Patient management and personalized therapeutic options are discussed collegially. The logopedist, coordinating the activity of other therapists in the Centre, is responsible for patient treatment. In addition, the logopedist is responsible for counselling patients, nurses and informal caregivers.

Keywords: Deglutition disorders, Therapy, Diagnosis, Swallowing centre

Riassunto

La richiesta di gestione di pazienti con disfagia è in aumento. Il cambiamento degli scenari entro cui i pazienti si muovono da reparti per acuto a reparti per cronico o al domicilio, richiede una rete assistenziale in grado di integrare le risorse di ospedali e territorio, così come di ottimizzare le risorse umane e tecnologiche. Questo vale per i Centri Deglutizione dove la presa in carico, la gestione, il trattamento e la sorveglianza dei pazienti dimessi rappresentano obiettivi prioritari. La complessità della disfagia e la peculiarità della patologia sottostante richiede un approccio multidisciplinare al paziente. Il coordinatore del Centro è un Foniatra coadiuvato da un Logopedista. La gestione di ogni paziente, così come le opzioni terapeutiche personalizzate sono discusse in team. Il trattamento compete al Logopedista che coordina l’attività degli altri terapisti del Centro. Il counselling del paziente, degli infermieri e degli altri caregivers sono attività preminenti del Logopedista.

Introduction

The number of patients referred for swallowing disorders is constantly growing. Increased lifespan and refinement of emergency medical treatment has markedly improved the survival both of adults and infants with previously mortal or severely disabling diseases 1. The greater awareness of health care expectations and the effort to improve quality of life (QoL) point to patient-centred management of dysphagia. Respecting the needs of persons and addressing their basic demands helps improve satisfaction of the service offered.

The amount of literature on dysphagia has assumed overwhelming proportions, even for specialists. One of the main issues is the need for a multidisciplinary approach to dysphagia 2, which must always take into consideration the underlying disorder. Defining the scope of practice in medical and rehabilitation settings 3–5 allows a multidisciplinary approach respecting of each professional and targeted to the needs of the patient.

Definition and topics

Swallowing is the ability to carry a solid, liquid, gaseous or mixed texture bolus from the mouth to the stomach 6 keeping food and liquids out of the larynx, thanks to a combination of functions that stop food and liquids from entering the larynx; dysphagia derives from an impairment of one or more of these functions, at their origin or of their coordination 7. Dysphagia is a symptom 8 that involves oral, pharyngeal or oesophageal phase of swallowing, with a negative impact on health and QoL. Italian epidemiological data are not available 6 9. Data from the international literature are alarming for the elderly population 10. It has been estimated that by 2010 nearly 16,500,000 individuals will need attention for dysphagia 11. In another case series, the incidence and prevalence of dysphagia depends on the underlying pathology, with a clear majority of neurological disorders 1.

This is the mission of Centres devoted to the study of swallowing disorders (Swallowing Centres) 12 13. Hospital-based centres allow a multidisciplinary approach to the management of dysphagia, with very refined diagnostic resources.

The activities of Swallowing Centres may be extended to the community setting, considering a team with diagnostic, therapeutic and nursing profiles. Cultural and educational programmes must also be considered.

The development of specific competence in dysphagia makes the evaluation, by a phoniatrician and logopedist, an important step in the management of dysphagia. The treatment plan is designed according to clinical, non instrumental, and instrumental findings emerging from these evaluations. If the underlying disorder suggests a different diagnostic pathway, the specific phoniatric-logopedic evaluation needs to be considered in every possible approach. The need of phoniatricians – logopedists for assessing dysphagia has been proposed for decades but only recently confirmed 3–5 14. “The professional competence of phoniatricians and logopedists concern the physiopathology of communication and swallowing: the above is formalized in all countries of the European Union as well as in other countries of the world where the afore-mentioned professionals exist” 14.

Other objectives of the Swallowing Centre are monitoring results achieved by the treatment plan (continuum of care) and patient surveillance 15, challenges for the near future.

The setting

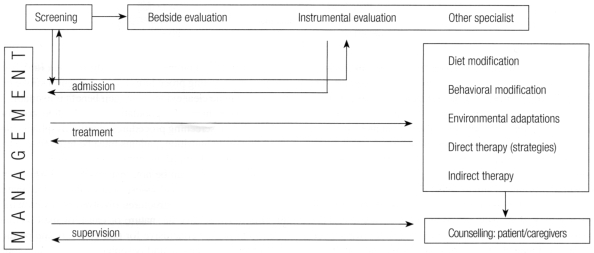

Swallowing Centres aim to provide patient management, from admission to discharge, and where local resources permit (Table I) perform instrumental evaluation and treatment. Screening and supervision are additional important activities. The phoniatrician must be involved both in the initial workup and design of the treatment plan. Management must be patient oriented, considering that the disability also involves the caregiver, so that the family, together with the clinician, must identify the most appropriate goals to pursue, in line with patient choices 15.

Table I. Management of the dysphagic patient (continuum of care).

Different scenarios for phoniatric-logopedic services can be established in public or private health care organisations: acute care, sub-acute care, long-term care (including nursing home facilities), rehabilitation and assisted living centres, and other health facilities (also mental health) (Table II).

Table II. Contemporary setting.

| SETTING | MANAGEMENT | TEAM SPECIALISTS |

Acute ward

|

|

|

Subacute ward

|

|

|

Rehabilitation and assisted living centres

|

|

|

Longterm care (also nursing home facilities)

|

|

|

Other health facilities (also mental facilities)

|

|

|

Home care

|

|

|

Activities of the service

The Swallowing Centre provides a point of reference for the community. All life phases must be considered: infancy, childhood, adulthood and old age 16–18. Diagnostic evaluation aims to define the anatomical or functional defects in motor effectors 2 and underlying disease 1 19: these goals may require the expertise of various professionals. Coordination of the multidisciplinary team (leadership), respecting specific expertise 4, remains an issue. The phoniatrician, based on his/her specific expertise 3 14 and close relationship with therapists, is in an ideal position to assume this role, translating the anatomo-functional disorders into therapeutic goals. Other team specialists will address the objectives formulated by the leader. At the end of the evaluation, the elements identified will be appraised by the care team to formulate an aetiological and functional diagnosis. In this phase, the severity of symptoms and risks of complications are evaluated. The treatment plan is influenced by the severity of the disorder, with a progressive restriction of therapeutic options 20.

Screening, clinical assessment, instrumental assessment, clinical management and discharge planning are cardinal activities of the Swallowing Centre. Patient management is pivotal to the intervention plan.

The management of patients with swallowing disorders, with a variable intensity of intervention 13 21–23, aims to take charge of the patient, including evaluating specific resources, planning and maintaining an intervention. The availability of local resources influences the type of intervention. The care plan (Table I) is managed and coordinated by the team leader, in line with the results of clinical and instrumental examinations and integrating the opinions of other team components: referring physician, therapists (logopedist, physiotherapist, occupational therapist), nurses (or other professional caregivers) and patient/family. The plan may foresee simple supervision of the patient or include behavioural modifications and new feeding strategies. In this phase, the logopedist plays a pivotal role in the management of patients with dysphagia acting as the link between the phoniatrician, other team members and caregivers. The logopedist then carries out an independent evaluation 14 24 and acts on the basis of the results of the preliminary phoniatric evaluation. Counselling of the patient and caregivers represents a crucial phase of speech therapy.

As already mentioned, patients are enrolled from screening, bedside and instrumental evaluation.

Screening procedures aim to detect signs and symptoms 21 of patients at risk for dysphagia, malnutrition or dehydration. These are non-diagnostic procedures and do not assess disorders in the anatomy and physiology of swallowing effectors or development of complications. Screening can be applied in all settings of patients at high risk for dysphagia 1 or with signs and symptoms suggesting dysphagia (Table III).

Table III. Main signs and symptoms requiring management.

| SIGNS | SYMPTOMS |

| Piecemeal deglutition | Weakness |

| Cough and drooling of saliva when speaking | Weight loss |

| Dysphonia and throat clearing | Difficulty initiating swallowing |

| Drooling and nasal bolus regurgitation | Crushing weight on chest |

| Increased eating times | Refusal to drink/eat |

| Pooling of saliva or bolus (hiding retained bolus) | Increased sensitivity to infections |

| Dehydration | Pulmonary infections |

| Malnutrition |

Studies on screening procedures commonly enrol stroke patients 25 26, but no clear evidence of their benefit is available 27. Data on other high risk populations or children are also lacking. When screening procedures identify dysphagia, dehydration or malnutrition, patients must be referred to other specialists of the team or instrumental evaluation.

Clinical assessment can be non-instrumental or instrumental 22 27 28. Bedside clinical assessment evaluates the anatomy and physiology of structures involved in swallowing, attempting to identify the nature or cause of malfunction. The assessment is conclusive for oral effectors and predictive for pharynx, larynx and oesophagus 15 27. Simple tools (spatula, probes, dish, straws, etc.) can be employed.

Clinical assessment is reserved for patients identified as belonging to high risk populations by screening procedures. It takes into consideration the clinical history and current medical conditions or growth impairments (in childhood) related to nutrition, hydration or pulmonary status. The motor and sensory validity of upper swallowing effectors (lips, cheeks, tongue, mandible, soft palate, pharynx) and laryngeal sphincter efficiency have to be evaluated for non-deglutitive praxis and during swallowing of foods of different volumes and texture. Cognitive and communication skills must be considered 22 30: attention and memory are closely related to safe swallowing.

Instrumental assessment aims to establish the integrity of structures involved in swallowing, such as functioning of oral effectors, pharynx, larynx and cervical oesophagus during bolus transit. Compensatory therapeutic strategies (manoeuvres and postures) must be evaluated by instrumental assessment 22 30.

Initial bedside assessment is generally integrated with instrumental procedures; however, there is no evidence of a reduction in pulmonary complications after instrumental assessment in stroke patients 27. Some data confirm the diagnostic potential of instrumental examination 2, despite the limits of predicting complications only by bedside examination 27 31.

Clinical indicators for instrumental assessment are an open issue. This is a problem faced daily, in clinical practice, considering not only the patient’s pulmonary status and general health status but also costs, tolerance and invasiveness of the procedures 30. Possible clinical indicators are listed in Table IV 22, although the most common request for consultation is to establish the safety of oral feeding 32.

Table IV. Main clinical indicators for ordering instrumental evaluation.

| Bedside examination not diagnostic (discordance between signs and symptoms) |

| Confirmation of medical diagnosis |

| High risk populations |

| Clinical début with pulmonary, dehydration or nutritional complications |

| Compromised cognitive or communication skills |

| Candidate for management and treatment (special manoeuvres and postures) |

| Altered swallowing capabilities (in previously diagnosed dysphagia) |

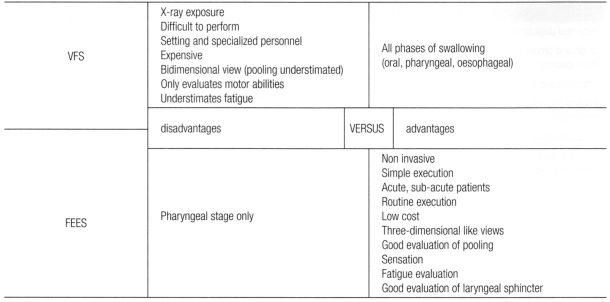

Instrumental assessment provides direct visualization of swallowing effectors and their functioning during bolus transit, allows appraisal of sensation and evaluates the effectiveness of manoeuvres and postures. Videofluoroscopic swallowing study (VFSS) or other dynamic digital procedures with modified barium swallow (MBS) 2 are the most exhaustive instrumental examination. However, VFSS is, today, no longer considered the gold standard (false negatives, reliability) 27 33. Fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES) 34 35 is easy to perform, in everyday practice, and in experienced hands can reliably assess all the elements required to establish an appropriate treatment plan 23 32 36–38. The pros and cons of the two procedures are presented in Table V. Unlike some years ago, endoscopic and radiologic procedures have become complementary 30, with good overlap of results 38–42 and are usually selected, based upon local availability. In a Swallowing Centre both procedures should be performed in head and neck and neurologic degenerative patients or when a differential diagnosis is necessary.

Table V. VFS and FEES: advantages and disadvantages.

Treatment of patients with swallowing disorders includes procedures to modify the physiology of swallowing or developmental deglutition patterns in childhood, with the aim of preventing aspiration even in the presence of anatomical modification of the effectors. Nutrition, hydration and drug administration are important outcomes. The treatment plan includes procedures to increase the efficiency of the laryngeal sphincter, neuromuscular effectors (including interventions on hypo/hypersensitivity) and provide airway protection. Clinical evaluation may influence treatment outcomes 2 28 43, and these findings must be considered 42–44. Treatment can be planned by the logopedist 4 14, together with other team members (dietician, occupational therapist, physiotherapist) and nurses, based on the initial evaluation. The logopedist instructs, trains and advises the patient and caregivers on swallowing techniques (manoeuvres and postures), optimising environmental conditions and behavioural patterns for safe deglutition. When possible, both patient and caregivers are actively involved in the treatment plan 15.

At the end of treatment, or when particular conditions arise (i.e., hospital discharge), the patient is given a series of goals to pursue in other settings or at home. The discharge plan identifies the goals and professionals involved (family physician, caregivers, home-care nurses). Plans are provided for patients identified by screening, bedside and/or instrumental assessment, submitted or not submitted to treatment. Patients and caregivers must be trained to identify ominous signs and symptoms of complications: cough, gurgling, pooling, etc. (Table III).

The availability of timely consultations with the Centre or urgent phoniatric-logopedic evaluations, in liaison with different professionals, represents an added benefit, having an impact on quality of service and patient satisfaction.

Service organization

The rationale subtending the intervention of a Swallowing Centre is articulated on two levels: internal and external organization.

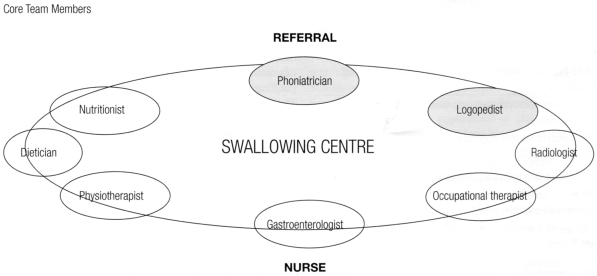

The internal organization (Table VI) of the Centre is coordinated by a medical specialist (leader), if possible a phoniatrician. The leader maintains contacts with the referring professional and team members and performs or participates in instrumental assessment. With other members of the assessment team, the leader plans the management, treatment and discharge of the patient. Medical staff are chosen, based upon local possibilities and the community catchment area. The core team (Table VI) should include a phoniatrician, logopedist, radiologist, nutritionist, gastroenterologist, dietician and physiotherapist. Nurses are enrolled in all settings (Table VI).

Table VI. Swallowing Centre: internal organization.

The most binding medical decisions (i.e. nil per os order, nasogastric tube feeding or percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy), are taken by the team, integrating the referring physician and patient as well as family’s needs.

The logopedist, together with other members of the rehabilitation team, performs functional evaluation of the patient and plans treatment in keeping with phoniatric and instrumental assessment. The logopedist acts in agreement with the nutritionist, occupational therapist, child-care and physiotherapist to achieve safe intake of foods, respecting food tastes, texture, aroma and colours. The possibility of taking medication by mouth is another goal that can be pursued.

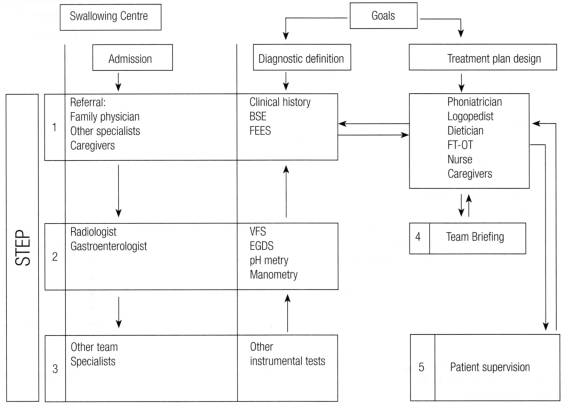

The external organization (Table VII) of the Swallowing Centre is articulated in several tiers. Access is possible, as an outpatient from all community services: home (by family physician), acute care, sub-acute care, long-term care (also nursing home facilities), rehabilitation and assisted living centres, mental health care facilities and other health units. Patient care, in these settings 1 (Table II), require specific dysphagia care training for the personnel.

Table VII. Swallowing Centre: external organization.

After admission (Table VII), the phoniatrician takes a meticulous case history and makes a complete physical evaluation, with FEES of the upper aerodigestive tract and evaluation of deglutition with bolus. In this first step, a diagnostic definition of dysphagia may be possible with an initial treatment plan design. If diagnosis cannot be defined, it is possible for the patient to take the second step, namely, VFSS. As a rule, the phoniatrician or logopedist assists the radiologist during radiological studies, performing specific tests and verifying manoeuvres and postures. Textures and volumes of bolus are previously defined by FEES to avoid unexpected episodes of inhalation of contrast medium and to reduce exposure to X-rays. As already pointed out, head and neck and degenerative neurological patients should be examined by both FEES and VFSS. If needed, subsequently or alternatively, the patient can be referred to the gastroenterologist for specific evaluation or the performance of other instrumental examinations (oesophago-gastro-duodenoscopy, pH-metry, manometry, etc.).

With dynamic tests, swallowing impairments can be defined in terms of the underlying pathology. As already pointed out, these tests also provide information on anatomical changes and physiological adaptations required to formulate strategies useful for patient management.

The patient is sometimes referred to others team specialists (step 3) when the aetiology in unknown and a diagnostic work-up is needed (ENT, neurologist, surgeon, internist, pneumologist, etc.). The clinical diagnosis, severity of dysphagia and therapeutic options are discussed together.

Personal experience and conclusions

The above considerations are derived from the experience of the Swallowing Centre set up at the City Hospital of Rimini; it aims to adapt the main experimental and clinical knowledge on dysphagia to community practice. With a catchment basin of 200,000 inhabitants, the Centre carries out approximately 150 evaluations per year. The current patient load concerns referrals coming to our attention since 1997 and training activity started in 2000, with the organization of training events and courses. As of May 2006, the Centre already had a clinical experience of approximately 1600 patients.

Patients have mainly neurological and medical disorders with cerebro-vascular, traumatic and degenerative sequelae (Table VIII).

Table VIII. Swallowing Centre activity. City Hospital of Rimini.

| Main disorders | Origin | |||

| Cerebrovascular disease | 401 | Medical ward | 253 | |

| TBI | 123 | Geriatrics | 219 | |

| Dementia | 68 | Neurology | 131 | |

| Degenerative Neurological Pathologies | 198 | Other acute care wards | 49 | |

| Presbyphagia | 148 | Nursing home facilities | 55 | |

| Head and neck operated | 66 | Outpatients | 231 | |

| ENT | 66 | |||

| Total patients: 1662 from 1997 to May 2006 | Rehabilitation and assisted living centres: | |||

| TBI | 163 | |||

| Stroke | 319 | 658 | ||

| Other | 176 | |||

TBI: Traumatic Brain Injury

The Centre initially admitted hospital inpatients and the service was subsequently expanded to outpatients, with a constant increase in demand. Ongoing education has allowed a screening programme to be adopted in the Hospital that aims to rationalize referrals for phoniatric and logopedist interventions and design of management plans based on liaison with nurses and caregivers. These professional figures play an important role in the management of symptoms with a marked impact on patient QoL and health expenditure.

The possibility to arrange prompt consultations, preceded by a telephone contact with the referring service, is important. A plan of supervision is also fundamental, which differs for each patient and includes periodic follow-up.

The patients referred to our service are submitted to phoniatric evaluation (Tab. VII). The medical history in an important tool for planning the following workup: previous disorders, variations of the feeding habits and signs or symptoms of dysphagia are probed.

The overall functioning of the patient are evaluated: vigilance, neuropsychological competency (memory, attention, perceptive ability, executive functioning, intellect and language) 29, awareness of illness and collaboration (possibility to speak, swallowing praxies and coughing on request).

The control of the head, trunk, and possible deficits of cranial nerves are evaluated, as well as motor abilities. Then the oro-pharyngeal effectors of deglutition, particularly neuromotor abilities (mobility, tone, strength, symmetry, speed, precision, coordination, diadococinesi) and sensory inputs (tactile, pressure, pain, thermal, gustatory) are tested.

After this first phase the patient is routinely submitted to endoscopic evaluation with bolus tests. The procedure is conducted according to a standard protocol in use at our service for years 30. Bolus tests are conducted with foods having volume and consistency identified at medical history and based on the complaints and abilities of the patient. Moreover, the neuromotor abilities of the soft palate, pharynx and larynx for the non swallowing praxies and during passage of the bolus are evaluated.

The sensitivity of the base of the tongue, pharynx and larynx (up to the vocal folds) is tested with the tip of the endoscope. Likewise, the possibility of pre-deglutitive spillage, indirect signs of false tracts (respiratory signs, residua in trachea) or post deglutitive residue are identified. The same parameters are evaluated during manoeuvres or postures.

During evaluation, generally well tolerated by the patient, one can appraise the appearance of structural fatigue and signs of dysphagia, otherwise underestimated or misunderstood.

When the definition of the anatomo-functional defect is not exhaustive, we proceed with dynamic radiologic evaluation of swallowing, conducted with the MBS procedure, using foods with different consistency and volume (identified during FEES). In our Center the radiologic evaluation is not routinely executed: we reserve this technique to cases selected by FEES, in head and neck and neurologic degenerative patients.

At the end of the evaluation we collect a series of information (Table IX) that is transmitted to the logopedist and used for planning treatment.

Table IX. FEES: information for the logopedist.

| Information | Event | Endoscope |

| Adequacy of the oral phase | Premature spillage | High position |

| Subjective perception of the bolus | Pooling in vallecule (hypopharynx) | High position |

| Site trigger | Pre-swallowing Inhalation | High position |

| Glottic closure | Intra-swallowing Inhalation | Low position |

| Site, amount and management of the pooling | Post-swallowing Inhalation | High position |

| Effectiveness of manoeuvres and postures | Protection for the low respiratory tract | High position |

The treatment plan, performed by the logopedist, starts with a functional evaluation of the patient, considering the information provided 16 17 45 46. The logopedist also appraises the patient during the bolus test or meal, depending on the setting, to better appreciate the neuropsychological abilities 29.

The treatment plan is articulated in interventions in different areas: a general area, effecting strategies of multimodale stimulation and a sectorial area through global and segmental relaxation, promoting correct respiration and control of full apnea, restoring tone to structures and strengthening protective reflexes. In specific areas the logopedist works with dietary artifices, correction of salivary deficit and planning protective manoeuvres and postures. He/she works for recovery of tone, strength and mobility of structures (paretic or amputated). The goal is a functional deglutition: an act that allows feeding and assumption of drugs while protecting the lower respiratory tract.

The progress needs to be monitored over time, with planned follow-up or a timely access to the Center under signal of caregivers or medical referrals. Careful management of the dysphagic patient helps avoid frustration of the team, helping to maintain the outcomes over time. When this fails, the need for alternative feeding strategies must be addressed: positioning of a gastrotomy tube (PEG) is a decision to be discussed together with the patient and the family.

References

- 1.ASHA Special populations: dysphagia. Edition Rockville, MD; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Logemann JA. Evaluation and treatment of swallowing disorders. Austin, Texas. Pro-ed; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Union of the European Phoniatricians, Committee of References. Phoniatrics: medical specialty for speech, voice and language pathology and swallowing disorders. Training principles and LOGBOOK. [Google Scholar]

- 4.ASHA. Preferred practice patterns for the profession of speech-language pathology. Rockville MD; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 5.ASHA Desk Reference. Scope of Practice in Speech-Language Pathology. Cardinal Documents of the Association I-22a/2001. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schindler O, Ruoppolo G, Schindler A. Deglutologia. Torino: Edizioni Omega; 2001. p. 167-88. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kahrilas PJ, Logemann JA. Volume accommodation during swallowing. Dysphagia 1993;8:259-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Piemonte M. Fisiopatologia della deglutizione. XIV Giornate Italiane di Otoneurologia. Manifestazione ufficiale dell’AOOI. Senigallia, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schindler O. Manuale operativo di fisiopatologia della deglutizione. Torino: Edizioni Omega; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baine WB, Yu W, Summe JP. Epidemiologic trends in the hospitalization of elderly. Medicare patients for pneumonia, 1991-1998. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1121-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.U.S. Census Bureau, Populations Projections Program. Department of Commerce, Population Division. Washington, DC; 2000.

- 12.Ravich WJ, Donner MW, Kashima H, Buchholz DW, Marsh BR, Hendrix TR, et al. The swallowing center: concepts and procedures. Abdominal Imaging 1985;1:255-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peracchia A, Bonavina L. Il centro per lo studio della deglutizione: organizzazione ed obiettivi. Chirurgia 1993;6:409-14. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Società Italiana di Foniatria e Logopedia. President Communication. www.SIFEL.net.

- 15.Martino R, Meissner-Fishbein B, Saville D, Barton D, Kerry V, Kodama S, et al. Preferred practice guidelines for dysphagia. Toronto, ON Canada: College of Audiologists and Speech-Language Pathologists of Ontario; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vernero I, Gambino M, Stefanin R, Schindler O. Cartella logopedica. Età evolutiva. Torino: Edizioni Omega; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vernero I, Gambino M, Schindler A, Schindler O. Cartella logopedica. Età adulta ed involutiva. Torino: Edizioni Omega; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farneti D. Presbifagia e disfagia. Geriatria 2005;XVII (Suppl)1:133-8. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cook IJ, Kahrilas PJ. AGA Technical review on management of oropharyngeal dysphagia. Gastroenterology 1999;116:455-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farneti D, Consolmagno P. Ristagni ipofaringei e loro significato nella valutazione clinica del cliente con disturbi della deglutizione. I Care 2004;4:114-17. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Logemann JA. Evaluation and treatment of swallowing disorders. 2nd edn. Austin, Texas: Pro-ed; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Speech-Language.Hearing Association (ASHA). Clinical indicators for instrumentation assessment of dysphagia: draft. Special interest division 13. Swallowing and swallowing disorders. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Langmore SE. Issues in the management of dysphagia. Folia Phoniat Logopaed 1999;51:220-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Speech-Language Hearing Association. Roles of Speech-Language Pathologist in swallowing and feeding disorders: technical report. Desk Reference 2002;3:181-99. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martino R, Pron G, Diamant N. Screening for oropharyngeal dysphagia in stroke: Insufficient evidence for guidelines. Dysphagia 2000;15:19-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perry L, Love CP. Screening for dysphagia and aspiration in acute stroke: a systematic review. Dysphagia 2001;16:7-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Diagnosis and treatment of swallowing disorders (dysphagia). Evidence Report Technology Assessment n. 8, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reilly S, Douglas J, Oates J. The evidence base for the management of dysphagia. In: Evidence based practice in speech pathology. London: Whurr Publisher; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Farneti D, Consolmagno P. Valenza di alcuni parametri neuropsicologici nella gestione di utenti disfagici adulti. I Care, 2005; 30:128-31. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Farneti D. La valutazione videoendoscopica. In: Schindler O, Ruoppolo G. Schindler A, editors. Deglutologia. Torino: Edizioni Omega; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farneti D, Consolmagno P. Aspiration: the predictive value of some clinical and endoscopy signs: evaluation of our case series. Acta Otorhinolaryngologica Italica 2005;25:36-42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Farneti D. Valenza della indagine strumentale nella gestione del cliente con disturbi della deglutizione. I Care 2003;29:5-9. [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCullough GH, Wetrz RT, Rosembeck JC, Mills RH, Webb WG, Ross KB. Inter- and intrajudge reliability for videofluoroscopic swallowing evaluation measures. Dysphagia 2001;16:110-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Langmore SE, Schatz K, Olsen N. Fiberoptic endoscopic examination of swallowing safety: a new procedure. Dysphagia 1988;2:216-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bastian RW. Contemporary diagnosis of the dysphagic patient. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1998;31:489-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bastian RW. Videoendoscopic evaluation of patients with dysphagia: an adjunct to the modified barium swallow. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1991;104:339-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bastian RW. The videoendoscopic swallowing study: an alternative and partner to the videofluoroscopic swallowing study. Dysphagia 1993;8:359-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aviv JE. Prospective, randomized outcome study of endoscopy vs. modified barium swallow. Laryngoscope 2000;110:563-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Logemann JA, Roa Pauloski B, Rademaker A, Cook B, Graner D, Milianti F, et al. Impact of the diagnostic procedure on outcome measures of swallowing rehabilitation in head and neck cancer patients. Dysphagia 1992;7:179-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smithard DG, O’Neill PA, Parks C, Morris J. Complications and outcome after acute stroke. Does dysphagia matter? Stroke 1996;27:1200-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu CH, Hsiao TY, Chen JC, Chang YC, Lee SY. Evaluation of swallowing safety with fiberoptic endoscope: comparison with videofluoroscopic technique. Laryngoscope 1997;107:396-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leder SB, Karas DE. Fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing in the pediatric population. Laryngoscope 2000;110:1132-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schmidt J, Holas M, Halvorson K, Reding M. Videofluoroscopic evidence of aspiration predicts pneumonia and death but not hydration after stroke. Dysphagia 1994;9:7-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Logemann JA, Rademaker A, Pauloski B, Karilas P. Effects of postural changes on aspirations in head and neck surgical patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1994;110:222-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schindler O, Ferri A, Travalca B, Di Rosa R, Schindler A, Utari C. La riabilitazione fonatoria, articolatoria e deglutitoria. In: La qualità di vita in oncologia cervico-cefalica. XLV Raduno Alta Italia; Torino 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Farneti D. Ruolo e contributo infermieristico nella odierna gestione del cliente con disturbi della deglutizione. Biblioteca informatica IPASVI, Agosto 2003. [Google Scholar]