Summary

Vestibular schwannoma may present as a sporadic or genetically-based multi-localized benign neoplasm of the internal auditory canal and/or cerebello-pontine angle region. Multiple localization is generally regarded as genetic in origin and often affects the stato-acoustic bundle on both sides. A case of double vestibular schwannoma localized on the same stato-acoustic bundle is presented. After removal, slight histological differences were found between the two separate masses. From these findings, the possibility of a unilateral multiple localization of a vestibular schwannoma is considered plausible within the range of clinical presentation, with negative genetic features. Whether these individual masses might have an autonomous origin or a different growth pattern remains to be fully elucidated.

Keywords: CPA tumour, Vestibular schwannoma, Neurofibromatosis

Riassunto

Lo schwannoma vestibolare si può presentare come neoplasia benigna della regione del condotto uditivo interno e/o dell’angolo ponto-cerebellare in forma sporadica o come localizzazione multipla su base genetica. La localizzazione multipla è generalmente da considerarsi di probabile origine genetica, con frequente interessamento del pacchetto stato-acustico di entrambi i lati. In questo lavoro viene presentato il caso di un paziente con una duplice, apparentemente individuale, localizzazione di uno schwannoma sul pacchetto stato-acustico dello stesso lato. Dopo la sua asportazione per via translabirintica, l’esame istologico ha messo in risalto lievi, ma pur sempre presenti, differenze istostrutturali. Da tale riscontro viene sottolineata la possibilità di poter incontrare clinicamente una localizzazione multipla di uno schwannoma vestibolare sullo stesso pacchetto stato-acustico, con screening genetico negativo per neurofibromatosi 2. Se le formazioni tumorali abbiano un’origine autonoma ed una potenzialità di crescita differente restano problematiche meritorie di ulteriori approfondimenti.

Introduction

Vestibular Schwannoma (VS) is the most frequent benign lesion occurring at cerebello-pontine angle (CPA) level, where it represents approximately 8% of all intra-cranial tumours 1. It more often presents as a sporadic, unilateral form, but it may also display a genetically-based expression, such as neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2), and have a bilateral and/or multiple type presentation 2.

The clinical onset of VS usually relates to the presence of unilateral tinnitus and/or hearing loss or balance disorders, and often prompts the patient to ask for a neurotological consultation. To date, modern imaging techniques, Gadolinium (DTPA)-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) above all, have drastically changed both diagnostic and, consequently, therapeutic algorithms, since millimetric VS can be detected even in poorly-symptomatic patients. Indeed, in tertiary referral Centres, such as University Hospitals, Fast-Spin Echo MRI is usually carried out as a “shortcut” exam, whenever VS is suspected 3.

Although even involvement of the superior (SVN) and inferior vestibular nerves (IVN) has classically been described 4, a higher predominance has recently been attributed to the latter, within the internal auditory canal (IAC) 5. Localization of the site of origin, within the neural context, has also been the object of several scientific contributions during the last few decades. Two main sites of origin have been proposed over the years: the first located at the glial-schwannian cell junction, also known as Obersteiner-Redlich zone, which is found in the medial IAC portion 6; the second localized more laterally, in the most proximal portion of the vestibular nerve, near, or at the level of, Scarpa’s ganglion, where the myelin is laid down by the oligodendroglial cell 7. This latter site of origin has also been specifically related to very small VSs.

In this report, the presence of a bifocal, unilateral VS, in a male Caucasian patient offered the opportunity to discuss the pathogenesis and clinical manifestations of VS.

Case report

A 47-year-old Caucasian male, affected by right-side VS, was referred for surgery from a secondary Otolaryngologic referral Centre to our University Hospital. The clinical history started 5 years earlier when right tinnitus and hearing loss led him to undergo neurotologic evaluation which revealed a right sensorineural hearing loss (PTA 45 dB), with 40% speech discrimination, and positive tone decay test at 1000 Hertz. Auditory Brainstem Response (ABR) showed a desynchronized trace. Ice caloric test revealed complete areflexia in the affected ear and hyporeflexia in the contra-lateral ear.

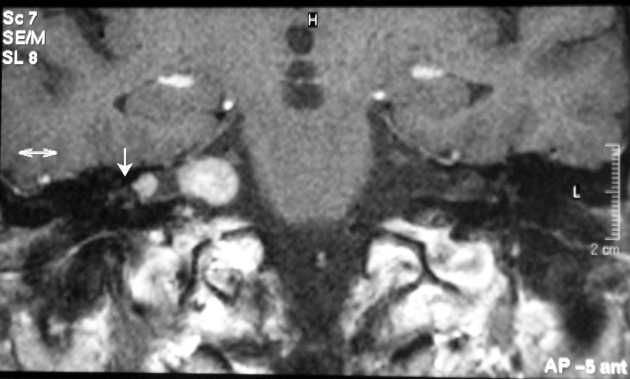

Gadolinium DTPA-enhanced MRI showed the presence of two separate, positively-contrasting areas within the IAC/CPA region: one located in the most lateral IAC portion, close to the fundus; the other, occupying the medial IAC as well as part of the CPA region (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

MRI coronal view: two, apparently distinct gadolinium-enhanced masses are visible within the right internal acoustic canal/cerebello-pontine angle region. White arrowhead: pedicled portion of the lateral mass.

The family history was negative for cutaneous tumours or central nervous system disease. Molecular genetic analysis was performed from the blood and normal skin of the patient and from the blood of family members (mother and two sisters), all of which resulted negative for NF2 mutations.

The patient also presented with multiple fibroma-like masses in the scalp, one of which was removed and sent for histological examination.

During the translabyrinthine surgical removal, the IAC fundus was found to be filled with a small, 5 mm large whitish mass (Fig. 2), which displaced the facial nerve antero-laterally. Medial to this small mass, the IAC showed a normal anatomical pattern while, more medially, the neural content appeared to divide into a larger, deeper tumoural mass which occupied part of the cisternal space in the CPA.

Fig. 2.

Macroscopic view of the laterally-located schwannoma mass. Arrow indicates its lateral pedicle (white arrowhead in Fig. 1).

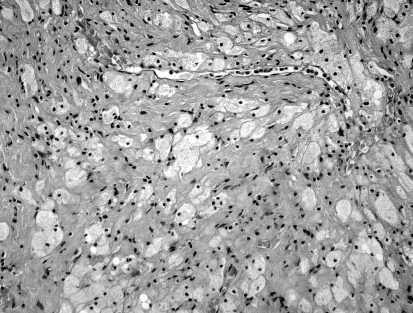

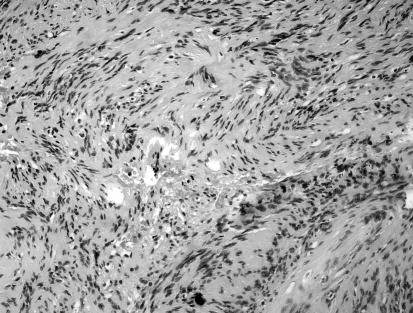

After removal, the entire small tumour and pieces of the larger mass were sent separately for pathology. Both specimens corresponded to a schwannoma: the smaller, more lateral one showed an even combination of both Antoni A and B traits, while in the larger one, more medial, Antoni B traits clearly prevailed (Fig. 3a, b).

Fig. 3.

a: Light micrograph of the medial VS mass. A loose aggregation of pleomorphic, vacuolated cells, characteristic of Antoni B type, can be visualized. b: Light micrograph of the lateral VS mass. Concomitant presence of denser and looser tissue is seen, i.e., Antoni A and B types.

Discussion

VS more often presents as a single mass, more or less occupying the IAC and/or the cerebello-pontine angle, in the form of sporadic VS. The simultaneous growth of multiple schwannomas would, instead, usually indicate the likelihood of NF2. Germline mutations of the NF2 gene would, in fact, predispose individuals to the development of multiple benign tumours of the nervous system, the most common of which is bilateral VS 8.

In this case, two clearly independent schwannoma masses were found on the vestibular nerve of the same patient for whom, therefore, the suspicion of NF2 gene mutation was rationally raised, also due to the concomitant presence of multiple scalp masses. Surprisingly, genetic and histological evaluations ruled out this possibility. In our opinion, this negative result, although unexpected, would allow us to implement the pattern of clinical manifestations of VS, which is often likely to be observed when MRI is precociously carried out, as occurs nowadays. Furthermore, some insights into the site of origin of VS can also be added, enriching a debate which has been rescued by recent literature notes 7.

Scarpa’s ganglion as the site of origin for VS, first mentioned by Henschen in 1915 9, was confirmed by Leonard and Talbot in the ’70s 10. A few years later, Stewart et al. 11, on the grounds of meticulous histopathological studies, demonstrated a multifocal origin along the intra-IAC portion of the vestibular nerve. Later, Neely et al. 12 reinforced this concept by demonstrating the VS origin on the tract of the IVN which lies distal to the glial-schwannian junction. A further contribution to this issue was also given by Foncin et al. 13 and was supported by the consideration that, in the adult human vestibular ganglion, unique among the vertebrates, the bipolar ganglion cells are devoid of myelin sheaths, which may be responsible for the permanent immaturity (neoteny) explaining the abnormal Schwann cell proliferation 14. Following an elegant ultrastuctural study, Viala et al. 15 identified a clear connection between the tumour and Scarpa’s ganglion, with frequent abnormalities in number and appearance (darkness, loss of connection with ganglionar cells) of the Schwann cells located at the junction between the tumour and ganglion, while a secondary invasion of the vestibular ganglion, due to the absence of a capsule, was excluded. In order to explain tumours apparently arising medially to Scarpa’s ganglion, they suggested, as the most likely explanation, the existence of ganglionar cell islands spread along the vestibular nerve.

Hence, despite a few studies published in the mid 70’s, there would appear to be general agreement on a lateral origin of VS in the IVN, at the level of the vestibular ganglion.

On the grounds of these hypotheses, the present case could offer appropriate reasons for further remarks on this issue. As already pointed out, all genetic tests showed negative results.

The finding of two distinct tumours on the same nerve, which was also very recently reported in the literature 16, might suggest three hypotheses:

VS which arises from two different sites;

VS which, spreading medially into the CP angle, looses connections with the original tumour;

VS which arises from different ganglionar elements spreads along the vestibular nerve.

The first hypothesis would suggest the simultaneous growth of two separate tumours on the same nerve from different structures and with different histological features that, in our case, was not possible to reveal. The second possibility is difficult to accept since the loss of connections between two capsulate tumours is very unlikely. Thus, the third hypothesis seems to be the most plausible, since it would explain the occurrence of both a small VS, arising at the level of Scarpa’s ganglion, and another one on a different site along the IVN course, showing a similar behaviour and histological features. Slight histological differences were, in fact, found between the two schwannoma masses. Antoni B-tumour type, which has been reported to occur in larger tumours 17 characterized mainly the medial, larger VS mass in our patient, while the smaller, lateral mass showed a mixed histological appearance. Whether this finding is of any importance for predicting whether the two individual masses would fuse or not in the future, it is difficult to say.

Another interesting speculation could be made regarding the fact that, in our case, no features of NF1 or NF2 could be identified. Indeed, due to the fact that most intracranial VS schwannomas present as sporadic lesions, bilateral expressions would per se fulfill the clinical diagnostic criteria for a genetic form, such as NF2. The simultaneous growth of multiple schwannomas in different loci further indicates a high likelihood of NF2 as well. In this regard, several scientific contributions have reported a number, though limited, of patients with multiple pathologically proven neurofibromas, without other NF1 or NF2 stigmata.

Blakley et al. 18 proposed the term of “multiple isolated neurofibromas” to identify 10 subjects affected by peripheral neurofibromas, without meeting either the original or the proposed revisions of NIH diagnostic criteria 19 for NF1 or NF2. Schwannomatosis has been established to be a clinical entity characterized by multiple schwannomas without vestibular involvement 20. The suggested criteria to be met for differentiating schwannomatosis from segmental NF2 are: (i) distinct mutation and concomitant loss of heterozygosity (LOS) in different tumours, (ii) no brain lesions at MRI, (iii) subcutaneous, instead of intracutaneous, location of the schwannoma, as observed in NF2 patients.

In the present case, it was not possible to meet any criterion which would frame such a bifocal, unilateral VS as NF2, nor as schwannomatosis or multiple isolated neurofibroma. Although it is possible to assume that two separate VS, if left alone, would, in the future, grow and eventually fuse in a single tumoural mass, the possibility that due to early MRI detection small, plurifocal VS may come to light, has to be taken into consideration when summarizing the possibilities of its clinical presentations.

References

- 1.Mahaley MS jr, Mettlin C, Natarajan N, Laws ER Jr, Peace BB. Analysis of patterns of care of brain tumour patients in the United States: a study of the brain tumour section of the AANS and CNS and the Commission on Cancer of the ACS. Clin Neurosurg 1990;36:347-52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wullich B, Kiechle-Schwarz M, Mayfrank L, Schempp W. Cytogenic and in situ DANN-hybridation studies in intracranial tumours of a patient with central neurofibromatosis. Hum Genet 1989;82:31-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zealley IA, Cooper RC, Clifford KM, Campbell RS, Potterton AJ, Zammit-Maempel I, et al. MRI screening for acoustic neuroma: a comparison of fast spin echo and contrast enhanced imaging in 1233 patients. Br J Radiol 2000;73:242-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clemis JD, Ballad WJ, Baggot PJ, Lyon ST. Relative frequency of inferior vestibular schwannoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1986;112:190-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Komatsuzaki A, Tsunoda A. Nerve origin of the acoustic neuroma. J Laryngol Otol 2001;115:376-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sterkers JM, Perre J, Viala P, Foncin JF. The origin of acoustic neuromas. Acta Otolaryngol 1987;103:427-31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xenellis JE, Linthicum FH Jr. On the myth of the glial/schwann junction (Obersteiner-Redlich Zone): origin of vestibular nerve schwannomas. Otol Neurotol 2003;24:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evans DG, Sainio M, Baser ME. Neurofibromatosis type 2. J Med Genet 2000;37:897-904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henschen H. Zur Histologic und Pathogenesc der Kleinhirobrückenwinnkel Tumouren. Arch Psychiat 1915;56. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leonard JR, Talbot ML. Asymptomatic acoustic neurilemoma. Arch Otolaryngol 1970;91:117-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stewart TJ, Liland J, Schuknecht HF. Occult schwannomas of the vestibular nerve. Arch Otolaryngol 1975;101:91-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neely JG, Britton BH Geenberg SD. Microscopic characteristics of the acoustic tumour in relationship of its nerve of origin. Laryngoscope 1976;86:984-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foncin JF, Sterkers JM, Perre J, Corlieu P. The origin of Acoustic Neurinoma. An ultrastructural study of operated neurinoma incipiens. Ann Otolaryngol Chir Cervicofac 1979;96:11-22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sterkers JM, Perre J, Viala P, Focin JF. The origin of acoustic neuromas. Acta Otolaryngol 1987;103:427-31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Viala P, Perre J, Sterkers JM, Foncin JF. L’origine des neurinomes de l’acoustique. Ann Otolaryngol Chir Cervicofac 1986;103:475-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kennedy RJ, Salzman KL, Shelton C. Unilateral double vestibular schwannoma. Otol Neurotol 2005;26:1241-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jackler RK, Pfister MHF. Acoustic Neuroma (Vestibular Schwannoma). In: Jackler RK, Brakmann DE, editors. Neurotology. Philadelphia: Elsevier Mosby 2005. p. 727-82. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blakley P, Louis DN, Short MP, MacCollin M. A clinical study of patients with multiple isolated neurofibromas. J Med Genet 2001;38:485-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mulvihill JJ, Parry DM, Sherman JL, Pikus A, Kaiser-Kupfer MI, Eldridge R. Neurofibromatosis 1 (Recklinghausen disease) and neurofibromatosis 2 (bilateral acoustic neurofibromatosis). An update. Ann Intern Med 1990;113:39-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leverkus M, Kluwe L, Roll E-M, Beker G, Brocker E-B, Mautner VF, et al. Multiple unilateral schwannomas: segmental neurofibromatosis type 2 or schwannomatosis? Br J Dermatol 2003;148:804-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]