Abstract

Background

The emergence of blaKPC-containing Klebsiella pneumoniae (KPC-Kp) isolates is attracting significant attention. Outbreaks in the Eastern USA have created serious treatment and infection control problems. A comparative multi-institutional analysis of these strains has not yet been performed.

Methods

We analysed 42 KPC-Kp recovered during 2006–07 from five institutions located in the Eastern USA. Antimicrobial susceptibility tests, analytical isoelectric focusing (aIEF), PCR and sequencing of bla genes, PFGE and rep-PCR were performed.

Results

By in vitro testing, KPC-Kp isolates were highly resistant to all non-carbapenem β-lactams (MIC90s ≥ 128 mg/L). Among carbapenems, MIC50/90s were 4/64 mg/L for imipenem and meropenem, 4/32 mg/L for doripenem and 8/128 for ertapenem. Combinations of clavulanate or tazobactam with a carbapenem or cefepime did not significantly lower the MIC values. Genetic analysis revealed that the isolates possessed the following bla genes: blaKPC-2 (59.5%), blaKPC-3 (40.5%), blaTEM-1 (90.5%), blaSHV-11 (95.2%) and blaSHV-12 (50.0%). aIEF of crude β-lactamase extracts from these strains supported our findings, showing β-lactamases at pIs of 5.4, 7.6 and 8.2. The mean number of β-lactamases was 3.5 (range 3–5). PFGE demonstrated that 32 (76.2%) isolates were clonally related (type A). Type A KPC-Kp isolates (20 blaKPC-2 and 12 blaKPC-3) were detected in each of the five institutions. rep-PCR showed patterns consistent with PFGE.

Conclusions

We demonstrated the complex β-lactamase background of KPC-Kp isolates that are emerging in multiple centres in the Eastern USA. The prevalence of a single dominant clone suggests that interstate transmission has occurred.

Keywords: carbapenemases, ESBLs, Enterobacteriaceae, PFGE, rep-PCR

Introduction

The emergence of KPC carbapenemases in strains of Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa is attracting significant attention. In current surveys, Klebsiella pneumoniae is the most common pathogen harbouring blaKPC genes.1–5 Additionally, blaKPC-containing K. pneumoniae (KPC-Kp) isolates are becoming endemic in certain hospitals and are responsible for increasing numbers of outbreaks in several healthcare facilities located in the Eastern USA,6–8 Israel9,10 and Greece.11,12 Recently, sporadic KPC-Kp isolates were detected in Central and South America,5,13,14 the Far East15–17 and Europe.18–20

In the clinical laboratory, KPC-Kp isolates demonstrate resistance or reduced susceptibility to all β-lactams as well as many other classes of antimicrobial agents (i.e. fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides and sometimes polymyxins).4,7,21 Therefore, the emergence and spread of this multidrug-resistant (MDR) phenotype has created serious treatment and infection control problems.22,23 Detection of KPC-mediated carbapenem resistance in these isolates also poses a significant challenge for many clinical laboratories.21,24,25

Studies that examine the clonal relationship of large collections of KPC-Kp isolates from geographically separate institutions are still lacking. Earlier efforts investigating the clonal relatedness of KPC-Kp used isolates that were obtained from single hospitals or from the same geographic region (e.g. Tel Aviv and New York City).6–10 Moreover, previous analyses were performed using PFGE, ribotyping or randomly amplified DNA.6–9 The DiversiLab™ Strain Typing System, (Bacterial BarCodes, bioMérieux, Athens, GA, USA) is a semi-automated rep-PCR method able to analyse large numbers of isolates rapidly.26 Despite the literature regarding the use of the rep-PCR for epidemiological studies, the DiversiLab™ System has not yet been tested for K. pneumoniae as well as for KPC-Kp isolates.

Little is known regarding the presence of other β-lactamases or the genetic environment of isolates possessing blaKPC genes. Moland et al.27 reported a unique KPC-Kp strain producing at least eight different β-lactamases. Other studies have discovered a limited number of bla genes in addition to blaKPC.7,10,15,24,28,29 In a study performed by Bradford et al.,29 the β-lactamases possessed by 18 KPC-Kp isolates were characterized by PCR and cloning. Although three strains possessed two TEM-type enzymes, only one SHV-type β-lactamase was found in each of the 18 strains.

Taken together, the above considerations compelled us to characterize the β-lactamase background of KPC-Kp isolates from several institutions in order to: (i) understand the evolution of the molecular epidemiology of KPC-Kp in the Eastern USA; (ii) assess the in vitro efficacy of antibiotic combinations (i.e. β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations); and (iii) compare the ability of DiversiLab™ Strain Typing System versus PFGE to characterize KPC-Kp isolates. To these ends, we determined the β-lactam resistance phenotypes, β-lactamase genotypes and clonality of a large set of KPC-Kp isolates recently collected from five major healthcare institutions located in the Eastern USA. We discovered that KPC-Kp isolates frequently belong to a single genotype and possess a complex β-lactamase background, in the context of significant resistance to penicillins, cephalosporins, carbapenems and β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations, limiting the choices available for antibiotic therapy.

Materials and methods

Clinical isolates

Forty-two KPC-Kp strains collected during a previous study were analysed.30 Isolates were detected from January 2006 to October 2007 at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York City (MSMCNY, n = 24), University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC, n = 4) and three Cleveland institutions including University Hospitals Case Medical Center (UHCMC, n = 2), Cleveland Clinic (CC, n = 9) and Louis Stokes Veterans Affairs Medical Center (LSVAMC, n = 3).

PCR and sequencing of β-lactamase genes

Specific primers were used to amplify and sequence the blaKPC genes [Table S1, available as Supplementary data at JAC Online (http://jac.oxfordjournals.org/)]. KPC-Kp isolates were further investigated by PCR amplification to detect other resistance determinants, including those for other carbapenemases, blaESBL genes (where ESBL stands for extended-spectrum β-lactamase) and blaAmpC genes. The complete list of genes investigated and the corresponding set of primers used for PCR and DNA sequencing analysis are reported in Table S1.

DNA was obtained by suspending two to three colonies of each test isolate grown on MacConkey agar plates in 500 µL of nuclease-free water (UBS Corporation, Cleveland, OH, USA) and heating at 90°C for 10 min using a dry bath incubator. Samples were spun at 10 000 rpm for 10 min and the resulting supernatant was diluted 1:10 with nuclease-free water. These samples were used as the bacterial DNA template for PCR assays. Amplification reactions were performed using the high-fidelity rTth DNA Polymerase XL (GeneAmp XL PCR Kit; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Temperature cycling conditions included an initial denaturation at 94°C for 1 min followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, annealing for 30 s (see Table S1 for the temperature of each primer set), with an extension at 72°C for 30 s. Cycling was followed by a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. Samples were incubated in the PTC-225 Peltier Thermal Cycler (MJ Research, Waltham, MA, USA). Reaction mixture (5 µL) containing the PCR product was mixed with 2 µL of UltraClean Gel Dye (Mo Bio Laboratories Inc., Carlsbad, CA, USA) and analysed by electrophoresis in a 1% Ultrapure MB Grade agarose gel (USB Corporation).

The remaining amplified product (20 µL) was purified using Exonuclease I and Shrimp Alkaline Phosphatase before DNA sequencing, according to the manufacturer's instructions (ExoSAP-IT protocol; USB Corporation). Samples were incubated at 37°C for 30 min, at 45°C for 15 min and at 80°C for 15 min to degrade the unincorporated primers and nucleotides. Sequencing reactions were performed using BigDye v1.1 Sequencing Kits (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and sequence data were acquired on a 3730xl DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). DNA traces were interpreted by Lasergene 7.2 (DNASTAR, Madison, WI, USA). The final β-lactamase amino acid sequences were determined using the ExPASy Proteomics Server (http://ca.expasy.org) and compared with those previously described (http://www.lahey.org/studies/webt.htm).

Cloning and sequencing of multiple β-lactamase alleles

In cases where multiple alleles were suspected (i.e. double ‘spikes’ in the DNA sequencing traces at a single location), a new PCR product for each isolate was obtained as described above; however, the reactions were limited to 18 cycles of amplification. The product was purified using the QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen Sciences, Valencia, CA, USA) and subsequently cloned into a pCR-XL-TOPO vector, according to the manufacturer's instructions (TOPO XL PCR Cloning Kit; Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Plasmids were electroporated into competent ElectroMAX Escherichia coli DH10B cells (Invitrogen Corporation) and selected on Luria–Bertani (LB) agar containing kanamycin sulphate (50 mg/L; Invitrogen Corporation). Ten random colonies for each cloned PCR product were selected and cultures were grown overnight at 37°C in 3 mL of LB broth containing kanamycin sulphate (50 mg/L). Plasmids were isolated using the Wizard Plus Miniprep Kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Direct sequencing of the plasmid preparations was done using the primers previously listed (Table S1). Furthermore, specific primers for the TOPO vector were also used (M13-forward, 5′-GTAAAACGACGGCCAG-3′; M13-reverse, 5′-CAGGAAACAGCTATGAC-3′).

Three E. coli DH10B isolates containing blaSHV-11 (VA-401-t5), blaSHV-12 (VA-389-t4) or blaTEM-1 (VA-402-t3) cloned into the pCR-XL-TOPO vector and one blaKPC-2-containing K. pneumoniae strain (VA-361) were used as controls to test the reliability of the above cloning method.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

MICs of β-lactams were determined using the agar dilution method on cation-adjusted Mueller–Hinton agar (BBL, Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD, USA) using a Steer's ReplicatorTM that delivers 104 cfu/10 µL spot. We tested the following antibiotics: cefoxitin (Abraxis Pharmaceutical Products, Schaumburg, IL, USA), piperacillin (Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO, USA), piperacillin/tazobactam (Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc., Philadelphia, PA, USA), cefotaxime (Sigma Chemical Co.), ceftazidime (Sandoz GmbH, Kundl, Austria), cefepime (Bristol-Myers Squibb, Princeton, NJ, USA), aztreonam (Bristol-Myers Squibb), imipenem/cilastatin (Merck & Co. Inc., Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA), meropenem (AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, Italy), ertapenem (Merck & Co. Inc.) and doripenem (Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical Inc., Raritan, NJ, USA). Lithium clavulanate (GlaxoSmithKline, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA) and sodium tazobactam (Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc., Pearl River, NY, USA) were tested at a constant concentration of 4 mg/L in combination with cefepime, imipenem, meropenem, ertapenem and doripenem. For non-β-lactam antibiotics (e.g. aminoglycosides and quinolones), antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed using the Microscan Autoscan System (Siemens, West Sacramento, CA, USA). Results were interpreted according to the CLSI criteria31 except for doripenem, for which the FDA breakpoint for Enterobacteriaceae (i.e. ≤0.5 mg/L susceptible) was used. The following ATCC control strains were used: E. coli 25922, P. aeruginosa 27853 and K. pneumoniae 700603.

Analytical isoelectric focusing (aIEF)

aIEF was performed to identify and determine the pIs of β-lactamases expressed by the KPC-Kp isolates. Crude cell lysates were prepared using a previously described method.32 Enzyme extracts were loaded onto 5% polyacrylamide gels containing ampholines (pH range, 3.5–9.5; GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences AB, Uppsala, Sweden) and electrophoresed using a Multiphor II apparatus (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA). Gels were focused at 4°C with 8 W for 150 min. The detection of β-lactamases was performed by the addition of 1 mM nitrocefin (Becton Dickinson Biosciences, Cockeysville, MD, USA) onto the gel. The following purified β-lactamase enzymes prepared by our laboratory were used as controls: TEM-1 (pI, 5.4), SHV-1 (pI, 7.6), KPC-2 (pI, 6.7) and CMY-2 (pI, 9.0).

Clonal analysis by PFGE

PFGE was performed as described previously.33,34 Whole chromosomal DNA in agarose was digested with SpeI (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) and the restriction fragments were separated in a CHEF DRII apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). After electrophoresis, the gels were stained with ethidium bromide, illuminated under UV light and photographed. Computer-assisted (BioNumerics; Applied Maths, Kortrijk, Belgium) analysis of PFGE patterns was performed. The Dice correlation coefficient was used to analyse the similarity of the banding patterns. Strains with similarity coefficients of >80% were considered to belong to the same PFGE type (i.e. clonally related), while those with indistinguishable PFGE banding patterns (>97% similarity coefficient) were considered to be of the same subtype.35 Clustering was based on the unweighted pair-group method with arithmetic averages. The tolerance position was 1%.

rep-PCR

Genomic similarity of KPC-Kp isolates was also investigated with the DiversiLab™ Strain Typing System (Bacterial BarCodes, bioMérieux). Genomic DNA was extracted using the UltraClean™ Microbial DNA Isolation Kit (Mo Bio Laboratories). Rep-PCR was performed using the DiversiLab Klebsiella Kit (Bacterial BarCodes). Results were interpreted with DiversiLab Web-Based Software using the Pearson correlation and the modified Kullback–Leibler methods. In this study, clonally related isolates were defined as a ≥95% homology as recorded by software provided by the manufacturer.

Results

Molecular characterization of β-lactamase genes

As summarized in Table 1, sequencing analysis revealed that 25 (59.5%) strains harboured blaKPC-2 and the remaining 17 (40.5%) carried blaKPC-3. The majority of KPC-Kp strains also contained blaTEM-1 (38/42, 90.5%) and blaSHV-11 (40/42, 95.2%); blaSHV-12 was detected in 50.0% (21/42) of KPC-Kp isolates. In general, seven isolates contained other SHV variants (VA-368, blaSHV-5 and blaSHV-68; VA-373, VA-375 and VA-384, blaSHV-14; VA-391, blaSHV-77; VA-398, blaSHV-27; VA-417, blaSHV-26). The aIEF results were consistent with these findings, showing β-lactamase bands of pI 5.4 (TEM-1 enzyme), 6.7 (KPC-2,-3), 7.6 (SHV-11 enzyme) and 8.2 (SHV-12 enzyme) (Table 1). β-Lactamases migrating with pIs >8.2 were not detected. The average number of β-lactamases in KPC-Kp isolates was 3.5 (range 3–5) (Table 1). We did not detect blaCTX-M, blaIMP, blaVIM, blaCMY-2-like, blaACT-1, blaP99, blaPER-1, blaPSE, blaFOX, blaMIR or blaDHA genes among the 42 KPC-Kp isolates (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sequencing of β-lactamase genes and aIEF results for the 42 blaKPC-containing (KPC-Kp) isolates detected in five institutions in the Eastern USA

| β-Lactamase genotype |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolate | KPC type | TEM type | SHV typea | aIEF bands (pI) |

| VA-184 | KPC-2 | — | SHV-11, SHV-12 | 5.2, 6.7, 7.6, 8.2 |

| VA-237 | KPC-2 | — | SHV-11, SHV-12 | 5.2, 6.7, 7.6, 8.2 |

| VA-267 | KPC-3 | TEM-1 | SHV-11, SHV-12 | 5.4, 6.7, 7.6, 8.2 |

| VA-357 | KPC-2 | — | SHV-11 | 5.4, 6.7, 7.0, 7.6 |

| VA-360 | KPC-2 | TEM-1 | SHV-11, SHV-12 | 5.4, 6.7, 7.6, 8.2 |

| VA-361 | KPC-2 | TEM-1 | SHV-11 | 5.4, 6.7, 7.6, 8.2 |

| VA-362 | KPC-2 | TEM-1 | SHV-11, SHV-12 | 5.4, 6.7, 7.0, 7.6, 8.2 |

| VA-364 | KPC-2 | TEM-1 | SHV-11 | 5.4, 6.7, 7.0, 7.6 |

| VA-367 | KPC-3 | TEM-1 | SHV-11, SHV-12 | 5.4, 6.7, 7.6, 8.2 |

| VA-368 | KPC-2 | TEM-1 | SHV-5, SHV-68b | 5.4, 6.7 |

| VA-373 | KPC-2 | — | SHV-11, SHV-14c | 6.7, 7.0, 7.6 |

| VA-375 | KPC-3 | TEM-1d | SHV-11, SHV-14 | 5.4, 5.8, 6.7, 7.0, 7.6 |

| VA-376 | KPC-2 | TEM-1 | SHV-11, SHV-12 | 5.4, 6.7, 7.6, 8.2 |

| VA-378 | KPC-2 | TEM-1 | SHV-11, SHV-12 | 5.4, 6.7, 7.6, 8.2 |

| VA-380 | KPC-2 | TEM-1 | SHV-11, SHV-12 | 5.4, 6.7, 7.6, 8.2 |

| VA-383 | KPC-2 | TEM-1 | SHV-11, SHV-12 | 5.4, 6.7, 7.6, 8.2 |

| VA-384 | KPC-2 | TEM-1 | SHV-11, SHV-12, SHV-14c | 5.4, 6.7, 7.6, 8.2 |

| VA-387 | KPC-2 | TEM-1 | SHV-11, SHV-12 | 5.4, 6.7, 7.6, 8.2 |

| VA-388 | KPC-3 | TEM-1 | SHV-11 | 5.4, 6.7 |

| VA-389 | KPC-2 | TEM-1 | SHV-11, SHV-12 | 5.4, 6.7, 7.6 |

| VA-390 | KPC-2 | TEM-1 | SHV-11 | 5.4, 6.7, 7.6 |

| VA-391 | KPC-3 | TEM-1 | SHV-11, SHV-12, SHV-77e | 5.4, 6.7, 7.6, 8.2 |

| VA-392 | KPC-3 | TEM-1 | SHV-11 | 5.4, 6.7, 7.6, 8.2 |

| VA-394 | KPC-3 | TEM-1 | SHV-11, SHV-12 | 5.4, 6.7, 7.6 |

| VA-395 | KPC-2 | TEM-1d | SHV-11, SHV-12 | 5.4, 5.8, 6.7, 7.6, 8.2 |

| VA-396 | KPC-2 | TEM-1d | SHV-11 | 5.4, 5.6, 6.7, 7.6 |

| VA-397 | KPC-3 | TEM-1 | SHV-11 | 5.4, 5.6, 6.7, 7.6 |

| VA-398 | KPC-3 | TEM-1 | SHV-11, SHV-12, SHV-27f | 5.4, 6.7, 7.6 |

| VA-400 | KPC-2 | TEM-1 | SHV-11, SHV-12 | 5.4, 6.7, 7.6 |

| VA-401 | KPC-3 | TEM-1 | SHV-11 | 5.4, 6.7, 7.6 |

| VA-402 | KPC-3 | TEM-1 | SHV-11 | 5.4, 5.8, 6.7, 7.6 |

| VA-403 | KPC-3 | TEM-1 | SHV-11 | 5.4, 6.7, 7.6 |

| VA-404 | KPC-2 | TEM-1 | SHV-11, SHV-12 | 5.4, 6.7, 7.6 |

| VA-406 | KPC-2 | TEM-1d | SHV-11, SHV-12 | 5.4, 5.8, 6.7, 7.6 |

| VA-408 | KPC-2 | TEM-1d | SHV-11, SHV-12 | 5.4, 5.8, 6.7, 7.6 |

| VA-409 | KPC-3 | TEM-1 | SHV-11 | 5.4, 5.8, 6.7, 7.6 |

| VA-410 | KPC-3 | TEM-1d | SHV-11 | 5.4, 5.8, 6.7, 7.6 |

| VA-412 | KPC-2 | TEM-1 | SHV-11 | 5.2, 5.4, 5.8, 6.7, 7.6, 8.2 |

| VA-413 | KPC-2 | TEM-1d | SHV-11 | 5.4, 5.8, 6.7, 7.6 |

| VA-414 | KPC-3 | TEM-1d | SHV-11 | 5.4, 5.8, 6.7, 7.6 |

| VA-416 | KPC-3 | TEM-1 | SHV-11 | 5.4, 6.7, 7.6 |

| VA-417 | KPC-3 | TEM-1 | SHV-26 | 5.4, 6.7, 7.6 |

aFor all KPC-Kp isolates, the SHV PCR product was cloned and sequenced.

bSHV-68 is not characterized.

cSHV-14 is not an ESBL.52

dKPC-Kp isolates for which the TEM PCR product was cloned and sequenced.

eSHV-77 is not characterized.

fSHV-27 possesses a pI of 8.2.

Antimicrobial susceptibility tests

As shown in Table 2, KPC-Kp isolates expressed high-level resistance to all non-carbapenem β-lactams (MIC90s ≥128 mg/L), except for three isolates (VA-237, VA-387 and VA-398) that were susceptible to cefepime (MICs of 8 mg/L).

Table 2.

Antimicrobial susceptibility test results for the 42 KPC-Kp isolates detected in five institutions in the Eastern USA

| MIC (mg/L)a |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolate | FOX | PIP | TZP | CAZ | CTX | ATM | FEP | FEP/CLA | FEP/TZB | IPM | IPM/CLA | IPM/TZB | MEM | MEM/CLA | MEM/TZB | ERT | ERT/CLA | ERT/TZB | DORb | DOR/CLA | DOR/TZB |

| VA-184 | 128 | 2048 | 2048 | 512 | 128 | 1024 | 32 | 8 | 16 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 16 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| VA-237 | 128 | 512 | 512 | 256 | 32 | 512 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| VA-267 | 256 | 2048 | 1024 | 512 | 64 | 1024 | 32 | 16 | 16 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| VA-357 | 256 | >2048 | 2048 | 128 | 128 | 512 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| VA-360 | 512 | >2048 | 2048 | 512 | 256 | 2048 | 128 | 64 | 32 | 32 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 16 | 32 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| VA-361 | 256 | >2048 | 1024 | 256 | 64 | 512 | 32 | 8 | 16 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 16 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| VA-362 | 256 | >2048 | 512 | 128 | 64 | 256 | 16 | 8 | 16 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| VA-364 | 256 | >2048 | 2048 | 128 | 64 | 128 | 32 | 8 | 32 | 8 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| VA-367 | 256 | 1024 | 512 | 512 | 64 | 1024 | 16 | 8 | 16 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| VA-368 | 512 | 1024 | 512 | 32 | 32 | 512 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 16 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| VA-373 | 256 | >2048 | 2048 | 64 | 32 | 512 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| VA-375 | 512 | 1024 | 1024 | 64 | 32 | 512 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| VA-376 | 1024 | 2048 | 2048 | 512 | 256 | 1024 | 128 | 64 | 64 | 32 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 16 | 32 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| VA-378 | 256 | 2048 | 1024 | 256 | 64 | 1024 | 32 | 8 | 16 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 16 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| VA-380 | 256 | 2048 | 1024 | 256 | 128 | 512 | 64 | 32 | 64 | 8 | 2 | 8 | 16 | 8 | 16 | 16 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| VA-383 | 256 | 2048 | 512 | 256 | 64 | 1024 | 16 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| VA-384 | 1024 | 2048 | 1024 | 256 | 256 | 1024 | 128 | 64 | 64 | 32 | 16 | 16 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| VA-387 | 2048 | >2048 | 1024 | 128 | 512 | 2048 | 256 | 128 | 128 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 256 | 256 | 256 | 256 | 128 | 128 |

| VA-388 | 64 | 2048 | 512 | 512 | 64 | 256 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| VA-389 | 256 | 2048 | 512 | 1024 | 64 | 1024 | 16 | 8 | 16 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| VA-390 | 1024 | 1024 | 512 | 256 | 128 | 512 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 32 | 16 | 16 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| VA-391 | 256 | 1024 | 1024 | 512 | 128 | 2048 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| VA-392 | 256 | 1024 | 512 | 512 | 64 | 1024 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| VA-394 | 128 | 1024 | 512 | 512 | 64 | 1024 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| VA-395 | 256 | >2048 | 1024 | 1024 | 256 | 2048 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| VA-396 | 256 | 1024 | 512 | 512 | 64 | 256 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| VA-397 | 512 | 2048 | 1024 | 512 | 128 | 512 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| VA-398 | 64 | 1024 | 64 | 128 | 32 | 512 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| VA-400 | 256 | 1024 | 256 | 512 | 128 | 2048 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 1 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| VA-401 | 1024 | >2048 | 1024 | 1024 | 512 | 1024 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 64 | 32 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 64 | 64 | 64 |

| VA-402 | 256 | 2048 | 1024 | 128 | 16 | 512 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 8 | 8 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| VA-403 | 1024 | 2048 | 512 | 1024 | 256 | 512 | 128 | 64 | 64 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| VA-404 | 128 | 2048 | 1024 | 512 | 32 | 512 | 16 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 16 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| VA-406 | 1024 | 2048 | 1024 | 512 | 512 | 512 | 256 | 128 | 128 | 256 | 128 | 256 | 256 | 128 | 128 | 512 | 256 | 256 | 256 | 128 | 128 |

| VA-408 | 256 | 2048 | 1024 | 512 | 64 | 512 | 16 | 8 | 16 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| VA-409 | 256 | 2048 | 1024 | 1024 | 256 | 512 | 32 | 16 | 16 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| VA-410 | 128 | 1024 | 512 | 256 | 64 | 256 | 32 | 16 | 16 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| VA-412 | 256 | 2048 | 1024 | 1024 | 64 | 1024 | 16 | 8 | 16 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 16 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| VA-413 | 1024 | 2048 | 1024 | 64 | 64 | 512 | 128 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 32 | 32 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 64 | 64 | 64 |

| VA-414 | 1024 | 2048 | 1024 | >1024 | 512 | 2048 | 128 | 256 | 128 | 64 | 16 | 16 | 64 | 32 | 32 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| VA-416 | 512 | 2048 | 1024 | 1024 | 512 | 512 | 128 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 32 | 32 | 16 | 16 | 8 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| VA-417 | 128 | 2048 | 512 | 128 | 64 | 512 | 32 | 16 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| MIC50 | 256 | 2048 | 1024 | 512 | 64 | 512 | 32 | 16 | 16 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| MIC90 | 1024 | >2048 | 2048 | 1024 | 512 | 2048 | 128 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 32 | 32 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| S (%) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 7.1 | 33.3 | 11.9 | 57.1 | 71.4 | 64.3 | 61.9 | 71.4 | 66.7 | 4.8 | 11.9 | 9.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

FOX, cefoxitin; PIP, piperacillin; TZP, piperacillin/tazobactam; CAZ, ceftazidime; CTX, cefotaxime; ATM, aztreonam; FEP, cefepime; IPM, imipenem; MEM, meropenem; ERT, ertapenem; DOR, doripenem; CLA, clavulanate (constant concentration of 4 mg/L); TZB, tazobactam (constant concentration of 4 mg/L); S, susceptible. MICs were interpreted according to the CLSI criteria.31

aResults of β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations were interpreted as the CLSI criteria established for the drug alone.

bInterpretative criteria have not yet been established by CLSI; therefore, we interpreted the results according to the US FDA criteria (S ≤ 0.5 mg/L).

MIC50/90 values of carbapenems were 4/64 mg/L for imipenem and meropenem, 4/32 mg/L for doripenem and 8/128 mg/L for ertapenem. Approximately two-thirds of the isolates tested were susceptible to imipenem and meropenem. All isolates were doripenem-resistant according to the US FDA breakpoints, while 57.1% were susceptible to imipenem, 61.9% to meropenem and 4.8% to ertapenem according to the CLSI criteria. The carbapenem MIC cut-off values able to accurately predict KPC production in these isolates were: imipenem, ≥2 mg/L; meropenem, ≥1 mg/L; ertapenem, ≥2 mg/L; and doripenem, ≥1 mg/L (Table 2). Combining either of the β-lactamase inhibitors, clavulanate or tazobactam, with cefepime or the carbapenems did not decrease the MICs by more than two doubling dilutions in most cases (Table 2).

Percentages of non-susceptible KPC-Kp isolates for the remaining antibiotics were as follows: gentamicin, 57.1%; tobramycin, 92.9%; amikacin, 59.5%; ciprofloxacin, 88.1%; levofloxacin, 88.1%; moxifloxacin, 85.7%; tetracycline, 11.9%; and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, 97.6%. Colistin was tested at 4 mg/L, and all isolates were susceptible at this concentration.

PFGE

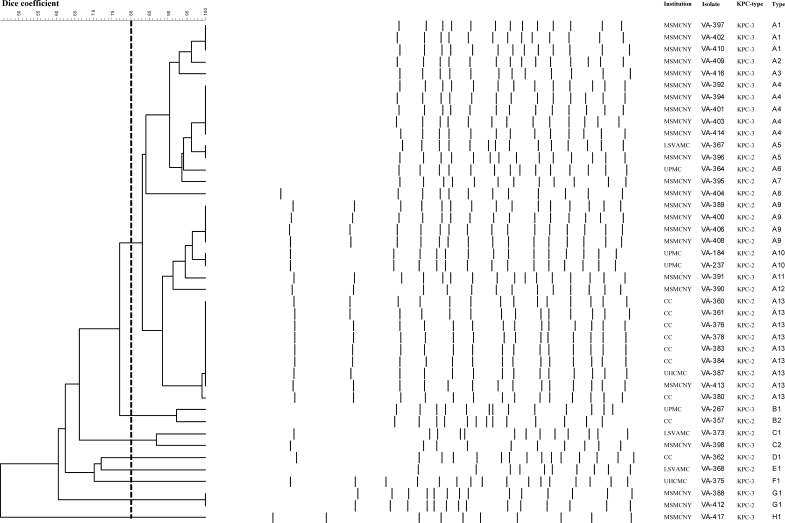

Using the Dice similarity coefficient to assess clonality by PFGE, we found that 32 KPC-Kp isolates belonged to the same genotype (type A), whereas the remaining 10 isolates showed <80% similarity (Figure 1). Isolates of PFGE type A were detected in collections from all five institutions. Thirteen subtypes of type A were observed, of which subtypes A1, A4, A9 and A13 were the most common. Isolates with subtypes A1, A4 and A9 were detected at the MSMCNY, whereas isolates of subtype A13 were collected at CC, UHCMC and MSMCNY (Figure 1). Interestingly, type A contains K. pneumoniae isolates possessing either blaKPC-2 or blaKPC-3 genes. However, each subtype includes strains that uniformly possess only a single blaKPC gene type. For example, subtypes A13 and A9 possess blaKPC-2, whereas subtypes A1 and A4 carry blaKPC-3.

Figure 1.

PFGE patterns of the 42 KPC-Kp isolates detected in five institutions located in the Eastern USA from January 2006 to October 2007 (MSMCNY, UPMC, UHCMC, CC, LSVAMC). Thirty-two isolates showed a genomic similarity >80% according to the Dice coefficient (type A). The remaining 10 isolates showed a similarity <80% when compared with type A isolates.

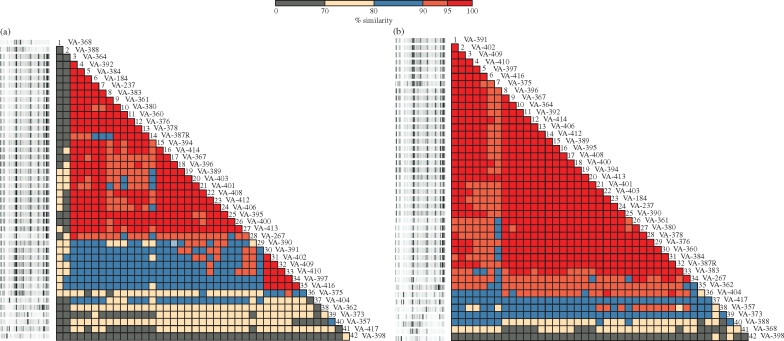

rep-PCR

As shown in Figure 2(a), using the Pearson correlation, two KPC-Kp genotypes were present. The major genotype included 25 KPC-Kp isolates collected in all five institutions, whereas the second included five strains collected at the MSMCNY only. The two genotypes shared a genomic homology of 80% to 95%. In contrast, using the modified Kullback–Leibler method, only one major KPC-Kp clone (n = 34) was observed (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Genotype analysis of the 42 KPC-Kp isolates performed with the DiversiLab™ Strain Typing System (Bacterial BarCodes, bioMérieux). (a) rep-PCR results interpreted using the Pearson correlation. Twenty-five isolates (from #3 to #27) were included in a single genotype, whereas five (from #31 to #35) were included in another clone type. (b) rep-PCR results interpreted using the modified Kullback–Leibler method. A single major KPC-Kp clone was identified among the 42 isolates analysed. This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the print version of JAC.

Discussion

The CDC estimates that K. pneumoniae is responsible for 8% of hospital-acquired infections and 3% of nosocomial outbreaks.36 In endemic areas, such as New York City, it is reported that more than one-third of K. pneumoniae isolates possess blaKPC genes.3 Therefore, the spread of KPC-Kp is a significant clinical and public health concern.1,2,37,38 In the present study, we analysed 42 KPC-Kp isolates recently collected in five institutions from a large geographic region to determine the number of β-lactamases that were expressed in the isolates and the genomic relatedness of them using both PFGE and rep-PCR.

Overall, four important findings emerged from our study: (i) contemporary KPC-Kp isolates possess a complex β-lactamase background (an average of 3.5 β-lactamase genes per isolate); (ii) clavulanate and tazobactam are unable to restore the activity of β-lactams against these isolates; (iii) there is evidence that KPC-Kp isolates from the five institutions in the Eastern USA are clonally related; and (iv) rep-PCR is a quick and reliable method to study KPC-Kp outbreaks.

Complex β-lactamase background

Survey studies are showing that the β-lactamase background of K. pneumoniae is becoming more complex.39–41 In our analysis, the blaKPC-2/3 carbapenemase genes detected among KPC-Kp were often accompanied by the blaTEM-1 and blaSHV-11 genes; the blaSHV-12 ESBL gene was also frequently found (50% of strains). This was previously observed by Essack et al. among blaKPC-negative K. pneumoniae isolates.39 However, it should be noted that using a standard DNA sequencing analysis method, many of the blaSHV-12-producing organisms would have been missed (during our study, 15 out of 21 blaSHV-12-positive KPC-Kp were identified as blaSHV-11-containing only; data not shown). While SHV-11 is a broad-spectrum β-lactamase (group 2b), SHV-12 is an ESBL able to confer resistance to all cephalosporins (group 2be).42 Thus, finding an additional SHV ESBL might have important clinical and epidemiological relevance. It should be noted that SHV-12 is one of the most prominent ESBLs found in the Eastern USA.43 Standard β-lactamase inhibitors were unable to lower the MICs of β-lactams for our clinical KPC-Kp isolates. However, in previous studies, clones expressing only the blaKPC gene showed MICs of β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations three or four dilutions lower than the antibiotic alone.44,45 Therefore, we could speculate that the additional β-lactamases (e.g. SHV and TEM types) expressed by KPC-Kp isolates could counteract the activity of the commercially used β-lactamase inhibitors. For similar reasons, the escalating number of β-lactamases could also contribute to the impaired ability of clinical laboratories to identify KPC-producing isolates.21,24,25

It is interesting to observe that blaCTX-M genes were not detected in our KPC-Kp isolates. This is in agreement with the known relatively low prevalence of CTX-M ESBLs among K. pneumoniae isolates in the USA compared with Asia, Europe, Canada and South America.46 To the best of our knowledge, KPC-Kp isolates possessing blaCTX-M genes have been detected only in China, Brazil and Puerto Rico.13,14,17 It is also interesting to note that production of AmpC enzymes could be reasonably excluded on the basis of our molecular and aIEF results.

In vitro activity

The antimicrobial susceptibility testing results show that KPC-Kp isolates are frequently resistant to aminoglycosides and quinolones and extremely resistant to all non-carbapenem β-lactams (MIC90s ≥ 128 mg/L). In addition, combinations of cefepime or carbapenems with clavulanate or tazobactam are unable to lower significantly the MICs. Our data indicate that the complexity of the class A β-lactamase background limits the clinical efficacy of novel combinations of β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitors using currently available clavulanate or tazobactam for treating infections caused by KPC-producers.

Our analysis also shows the limitations of our current CLSI breakpoints for imipenem and meropenem. Two-thirds of imipenem and meropenem MIC results for KPC-Kp strains were in the susceptible range, and 95% of ertapenem MIC results were resistant. Having some KPC-containing isolates that were ‘missed’ by an ertapenem screen is also disturbing as an important clinical predictor may be lost. Clinicians should be aware of these important limitations and, when necessary, request further testing.

Using the US FDA Enterobacteriaceae breakpoints, all isolates were doripenem-resistant. Thus, in our opinion, isolates of K. pneumoniae that exhibit imipenem, meropenem or doripenem MICs ≥1 mg/L or ertapenem MICs ≥2 mg/L should be screened by PCR for blaKPC genes or with a phenotypic method (i.e. modified Hodge test) for carbapenemase production.25

It should be noted that 10 KPC-Kp isolates (24%) included in PFGE type A expressed high-level resistance to carbapenems (i.e. MICs of imipenem ≥32 mg/L). Since production of other common carbapenemases has been excluded by molecular analysis and aIEF, this result may be due to alterations of outer membrane proteins such as OmpK35, OmpK36 and OmpK37.47,48 Strains lacking OmpK35 and OmpK36 have been reported to occur frequently among KPC-Kp strains.6,17,24,44

Clonal analysis

PFGE results show that 76% of KPC-Kp isolates were clonally related and were included in one common type (type A). Surprisingly, type A KPC-Kp was present in all five institutions studied. We also performed genotyping using rep-PCR. In our case, the modified Kullback–Leibler method of analysis of genotype data seemed to be more consistent than the Pearson correlation when compared with PFGE.

As in the case of Staphylococcus aureus,49 clonal analysis of KPC-Kp isolates is important for understanding how these organisms may be responsible for outbreaks and how these isolates are spreading in our healthcare system. We demonstrated that the majority of KPC-Kp isolates that are spreading from institution to institution in the Eastern USA originated from a single K. pneumoniae clone. We also demonstrated that the DiversiLab™ Strain Typing System can be used to quickly analyse large numbers of K. pneumoniae isolates.

Conclusions

In summary, the above results show why K. pneumoniae containing blaKPC represent a formidable therapeutic, diagnostic and clinical challenge. The complex β-lactamase background contributes to the incapacity of current β-lactams and β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations to inhibit KPC-Kp strains. It is most concerning that a single clone may be contributing to the current outbreaks in the Eastern USA. Further studies are warranted to assess if these related isolates possess transferable resistance determinants in common (e.g. Tn4401, plasmids and the KQ element), which are important in the dissemination of the MDR phenotype in KPC-Kp.50,51

Funding

This work was supported in part by AstraZeneca (to A. E. and R. A. B.), the National Institutes of Health (grant RO1-AI063517 to R. A. B. and grant RO1-AI045626 to L. B. R.), the Veterans Affairs Merit Review Program (L. B. R. and R. A. B.) and the Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Care VISN 10 (R. A. B.).

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Transparency declarations

R. A. B. received research and speaking invites from various pharmaceutical companies. None of these poses a conflict of interest with the present work. Other authors: none to declare.

Supplementary data

Table S1 is available as Supplementary data at JAC Online (http://jac.oxfordjournals.org/).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Philip N. Rather for his critical evaluation of our cloning and sequencing methods.

References

- 1.Queenan AM, Bush K. Carbapenemases: the versatile β-lactamases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:440–58. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00001-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walther-Rasmussen J, Hoiby N. Class A carbapenemases. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;60:470–82. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Landman D, Bratu S, Kochar S, et al. Evolution of antimicrobial resistance among Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Acinetobacter baumannii and Klebsiella pneumoniae in Brooklyn, NY. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;60:78–82. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deshpande LM, Jones RN, Fritsche TR, et al. Occurrence and characterization of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: report from the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program (2000–2004) Microb Drug Resist. 2006;12:223–30. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2006.12.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Villegas MV, Lolans K, Correa A, et al. First detection of the plasmid-mediated class A carbapenemase KPC-2 in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae from South America. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:2880–2. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00186-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woodford N, Tierno PM, Jr, Young K, et al. Outbreak of Klebsiella pneumoniae producing a new carbapenem-hydrolyzing class A β-lactamase, KPC-3, in a New York Medical Center. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:4793–9. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.12.4793-4799.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bratu S, Landman D, Haag R, et al. Rapid spread of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in New York City: a new threat to our antibiotic armamentarium. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1430–5. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.12.1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiang T, Mariano N, Urban C, et al. Identification of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae harboring KPC enzymes in New Jersey. Microb Drug Resist. 2007;13:235–9. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2007.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leavitt A, Navon-Venezia S, Chmelnitsky I, et al. Emergence of KPC-2 and KPC-3 in carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae strains in an Israeli hospital. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:3026–9. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00299-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Samra Z, Ofir O, Lishtzinsky Y, et al. Outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae producing KPC-3 in a tertiary medical centre in Israel. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2007;30:525–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cuzon G, Naas T, Demachy MC, et al. Plasmid-mediated carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase KPC-2 in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolate from Greece. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:796–7. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01180-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giakkoupi P, Vourli S, Polemis M, et al. Emergence of KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Greece. Abstracts of the Tenth β-Lactamase Meeting; Eretria, Greece. 2008. p. 14. Abstract L6. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robledo IE, Moland ES, Aquino EA, et al. First report of a KPC-4 and CTX-M producing K. pneumoniae (Kp) isolated from Puerto Rico (PR). Abstracts of the Forty-seventh Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy; Chicago, IL. Washington, DC, USA: American Society for Microbiology; 2007. p. 142. Abstract C2-1933. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monteiro J, Henriques APC, Santos AF, et al. Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae outbreak: emergence of KPC-2-producing strains in Brazil. Abstracts of the Forty-seventh Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy; Chicago, IL. Washington, DC, USA: American Society for Microbiology; 2007. p. 141. Abstract C2-1929. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wei ZQ, Du XX, Yu YS, et al. Plasmid-mediated KPC-2 in a Klebsiella pneumoniae isolate from China. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:763–5. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01053-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mendes RE, Bell JM, Turnidge JD, et al. Carbapenem-resistant isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae in China and detection of a conjugative plasmid (blaKPC-2 plus qnrB4) and a blaIMP-4 gene. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:798–9. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01185-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cai JC, Zhou HW, Zhang R, et al. Emergence of Serratia marcescens, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Escherichia coli isolates possessing the plasmid-mediated carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase KPC-2 in intensive care units of a Chinese hospital. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:2014–8. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01539-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naas T, Nordmann P, Vedel G, et al. Plasmid-mediated carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase KPC in a Klebsiella pneumoniae isolate from France. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:4423–4. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.10.4423-4424.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tegmark Wisell K, Haeggman S, Gezelius L, et al. Identification of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase in Sweden. Euro Surveill. 2007;12:E071220.3. doi: 10.2807/esw.12.51.03333-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woodford N, Zhang J, Warner M, et al. Arrival of Klebsiella pneumoniae producing KPC carbapenemase in the United Kingdom. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62:1261–4. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bratu S, Mooty M, Nichani S, et al. Emergence of KPC-possessing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Brooklyn, New York: epidemiology and recommendations for detection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:3018–20. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.7.3018-3020.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Daly MW, Riddle DJ, Ledeboer NA, et al. Tigecycline for treatment of pneumonia and empyema caused by carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Pharmacotherapy. 2007;27:1052–7. doi: 10.1592/phco.27.7.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Landman D, Salvani JK, Bratu S, et al. Evaluation of techniques for detection of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in stool surveillance cultures. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:5639–41. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.11.5639-5641.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lomaestro BM, Tobin EH, Shang W, et al. The spread of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae to upstate New York. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:e26–e28. doi: 10.1086/505598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anderson KF, Lonsway DR, Rasheed JK, et al. Evaluation of methods to identify the Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase in Enterobacteriaceae. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:2723–5. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00015-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carretto E, Barbarini D, Farina C, et al. Use of the DiversiLab semiautomated repetitive-sequence-based polymerase chain reaction for epidemiologic analysis on Acinetobacter baumannii isolates in different Italian hospitals. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;60:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moland ES, Hong SG, Thomson KS, et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae isolate producing at least eight different β-lactamases, including AmpC and KPC β-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:800–1. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01143-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith Moland E, Hanson ND, Herrera VL, et al. Plasmid-mediated, carbapenem-hydrolysing β-lactamase, KPC-2, in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;51:711–4. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bradford PA, Bratu S, Urban C, et al. Emergence of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella species possessing the class A carbapenem-hydrolyzing KPC-2 and inhibitor-resistant TEM-30 β-lactamases in New York City. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:55–60. doi: 10.1086/421495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Endimiani A, Carias LL, Hujer AM, et al. Presence of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates possessing blaKPC in the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:2680–2. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00158-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: Seventeenth Informational Supplement M100-S17. Wayne, PA, USA: CLSI; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paterson DL, Rice LB, Bonomo RA. Rapid method of extraction and analysis of extended-spectrum β-lactamases from clinical strains of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2001;7:709–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pfaller MA. Chromosomal restriction fragment analysis by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Application to molecular epidemiology. In: Isenberg HD, editor. Essential Procedures for Clinical Microbiology. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology; 1998. pp. 651–7. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ktari S, Arlet G, Mnif B, et al. Emergence of multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates producing VIM-4 metallo-β-lactamase, CTX-M-15 extended-spectrum β-lactamase, and CMY-4 AmpC β-lactamase in a Tunisian university hospital. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:4198–201. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00663-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carrico JA, Pinto FR, Simas C, et al. Assessment of band-based similarity coefficients for automatic type and subtype classification of microbial isolates analyzed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:5483–90. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.11.5483-5490.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Podschun R, Ullmann U. Klebsiella spp. as nosocomial pathogens: epidemiology, taxonomy, typing methods, and pathogenicity factors. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:589–603. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.4.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pope J, Adams J, Doi Y, et al. KPC type β-lactamase, rural Pennsylvania. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1613–4. doi: 10.3201/eid1210.060297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bratu S, Tolaney P, Karumudi U, et al. Carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Brooklyn, NY: molecular epidemiology and in vitro activity of polymyxin B and other agents. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;56:128–32. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Essack SY, Hall LM, Pillay DG, et al. Complexity and diversity of Klebsiella pneumoniae strains with extended-spectrum β-lactamases isolated in 1994 and 1996 at a teaching hospital in Durban, South Africa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:88–95. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.1.88-95.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paterson DL, Hujer KM, Hujer AM, et al. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases in Klebsiella pneumoniae bloodstream isolates from seven countries: dominance and widespread prevalence of SHV- and CTX-M-type β-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:3554–60. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.11.3554-3560.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Howard C, van Daal A, Kelly G, et al. Identification and minisequencing-based discrimination of SHV β-lactamases in nosocomial infection-associated Klebsiella pneumoniae in Brisbane, Australia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:659–64. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.3.659-664.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bush K, Jacoby GA, Medeiros AA. A functional classification scheme for β-lactamases and its correlation with molecular structure. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1211–33. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.6.1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bush K. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases in North America, 1987–2006. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008;14(Suppl 1):134–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yigit H, Queenan AM, Anderson GJ, et al. Novel carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase, KPC-1, from a carbapenem-resistant strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:1151–61. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.4.1151-1161.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yigit H, Queenan AM, Rasheed JK, et al. Carbapenem-resistant strain of Klebsiella oxytoca harboring carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase KPC-2. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:3881–9. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.12.3881-3889.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Canton R, Coque TM. The CTX-M β-lactamase pandemic. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2006;9:466–75. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Crowley B, Benedi VJ, Domenech-Sanchez A. Expression of SHV-2 β-lactamase and of reduced amounts of OmpK36 porin in Klebsiella pneumoniae results in increased resistance to cephalosporins and carbapenems. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:3679–82. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.11.3679-3682.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kaczmarek FM, Dib-Hajj F, Shang W, et al. High-level carbapenem resistance in a Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolate is due to the combination of blaACT-1 β-lactamase production, porin OmpK35/36 insertional inactivation, and down-regulation of the phosphate transport porin phoe. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:3396–406. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00285-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kennedy AD, Otto M, Braughton KR, et al. Epidemic community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: recent clonal expansion and diversification. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:1327–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710217105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Naas T, Cuzon G, Villegas MV, et al. Genetic structures at the origin of acquisition of the β-lactamase blaKPC gene. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:1257–63. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01451-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rice LB, Carias LL, Hutton RA, et al. The KQ element, a complex genetic region conferring transferable resistance to carbapenems, aminoglycosides, and fluoroquinolones in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:3427–9. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00493-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yuan M, Hall LM, Hoogkamp-Korstanje J, et al. SHV-14, a novel β-lactamase variant in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from Nijmegen, The Netherlands. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:309–11. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.1.309-311.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.