Abstract

Eukaryotic translation elongation factor 1A (eEF1A) both shuttles aminoacyl-tRNA (aa-tRNA) to the ribosome and binds and bundles actin. A single domain of eEF1A is proposed to bind actin, aa-tRNA and the guanine nucleotide exchange factor eEF1Bα. We show that eEF1Bα has the ability to disrupt eEF1A-induced actin organization. Mutational analysis of eEF1Bα F163, which binds in this domain, demonstrates effects on growth, eEF1A binding, nucleotide exchange activity, and cell morphology. These phenotypes can be partially restored by an intragenic W130A mutation. Furthermore, the combination of F163A with the lethal K205A mutation restores viability by drastically reducing eEF1Bα affinity for eEF1A. This also results in a consistent increase in actin bundling and partially corrected morphology. The consequences of the overlapping functions in this eEF1A domain and its unique differences from the bacterial homologs provide a novel function for eEF1Bα to balance the dual roles in actin bundling and protein synthesis.

The final step of gene expression takes place at the ribosome as mRNA is translated into protein. In the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, elongation of the polypeptide chain requires the orchestrated action of three soluble factors. The eukaryotic elongation factor 1 (eEF1)2 complex delivers aminoacyl-tRNA (aa-tRNA) to the empty A-site of the elongating ribosome (1). The eEF1A subunit is a classic G-protein that acts as a “molecular switch” for the active and inactive states based on whether GTP or GDP is bound, respectively (2). Once an anticodon-codon match occurs, the ribosome acts as a GTPase-activating factor to stimulate GTP hydrolysis resulting in the release of inactive GDP-bound eEF1A from the ribosome. Because the intrinsic rate of GDP release from eEF1A is extremely slow (3, 4), a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) complex, eEF1B, is required (5, 6). The yeast S. cerevisiae eEF1B complex contains two subunits, the essential catalytic subunit eEF1Bα (5) and the non-essential subunit eEF1Bγ (7).

The co-crystal structures of eEF1A:eEF1Bα C terminus:GDP: Mg2+ and eEF1A:eEF1Bα C terminus:GDPNP (8, 9) demonstrated a surprising structural divergence from the bacterial EF-Tu-EF-Ts (10) and mammalian mitochondrial EF-Tumt-EF-Tsmt (11). While the G-proteins have a similar topology and consist of three well-defined domains, a striking difference was observed in binding sites for their GEFs. The C terminus of eEF1Bα interacts with domain I and a distinct pocket of domain II eEF1A, creating two binding interfaces. In contrast, the bacterial counterpart EF-Ts and mammalian mitochondrial EF-Tsmt, make extensive contacts with domain I and III of EF-Tu and EF-Tumt, respectively. The altered binding interface of eEF1Bα to domain II of eEF1A is particularly unexpected given the functions associated with domain II of eEF1A and EF-Tu. The crystal structure of the EF-Tu:GDPNP:Phe-tRNAPhe complex reveals aa-tRNA binding to EF-Tu requires only minor parts of both domain II and tRNA to sustain stable contacts (12). That eEF1A employs the same aa-tRNA binding site is supported by genetic and biochemical data (13-15). Interestingly, eEF1Bα contacts many domain II eEF1A residues in the region hypothesized to be involved in the binding of the aa-tRNA CCA end (8). Because, the shared binding site of eEF1Bα and aa-tRNA on domain II of eEF1A is significantly different between the eukaryotic and bacterial/mitochondrial systems, eEF1Bα may play a unique function aside from guanine nucleotide release in eukaryotes.

In eukaroytes, eEF1A is also an actin-binding and -bundling protein. This noncanonical function of eEF1A was initially observed in Dictyostelium amoebae (16). It is estimated that greater than 60% of Dictyostelium eEF1A is associated with the actin cytoskeleton (17). The eEF1A-actin interaction is conserved among species from yeast to mammals, suggesting the importance of eEF1A for cytoskeleton integrity. Using a unique genetic approach, multiple eEF1A mutations were identified that altered cell growth and morphology, and are deficient in bundling actin in vitro (18, 19). Intriguingly, most mutations localized to domain II, the shared aa-tRNA and eEF1Bα binding site. Previous studies have demonstrated that actin bundling by eEF1A is significantly reduced in the presence of aa-tRNA while eEF1A bound to actin filaments is not in complex with aa-tRNA (20). Therefore, actin and aa-tRNA binding to eEF1A is mutually exclusive. In addition, overexpression of yeast eEF1A or actin-bundling deficient mutants do not affect translation elongation (18, 19, 21), suggesting eEF1A-dependent cytoskeletal organization is independent of its translation elongation function (18, 20). Thus, while aa-tRNA binding to domain II is conserved between EF-Tu and eEF1A, this actin bundling function associated with eEF1A domain II places greater importance on its relationship with the “novel” binding interface between eEF1A domain II and eEF1Bα.

Based on this support for an overlapping actin bundling and eEF1Bα binding site in eEF1A domain II, we hypothesize that eEF1Bα modulates the equilibrium between actin and translation functions of eEF1A and is perhaps the result of evolutionary selective pressure to balance the eukaryotic-specific role of eEF1A in actin organization. Here, we present kinetic and biochemical evidence using a F163A mutant of eEF1Bα for the importance of the interactions between domain II of eEF1A and eEF1Bα to prevent eEF1A-dependent actin bundling as well as promoting guanine nucleotide exchange. Furthermore, altered affinities of eEF1Bα mutants for eEF1A support that this complex formation is a determining factor for eEF1A-induced actin organization. Interestingly, the F163A that reduces eEF1A affinity is an intragenic suppressor of the lethal K205A eEF1Bα mutant that displays increased affinity for eEF1A. This, along with a consistent change in the actin bundling correlated with the affinity of eEF1Bα for eEF1A, indicates that eEF1Bα is a balancer, directing eEF1A to translation elongation and away from actin, and alterations in this balance result in detrimental effects on cell growth and eEF1A function.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Yeast Techniques and Mutation Preparation—S. cerevisiae strains used are listed in Table 1. Standard yeast genetic methods were employed (22). Yeast cells were grown in either YEPD (1% Bacto yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% dextrose) or defined synthetic complete media (C-) supplemented with 2% dextrose as a carbon source. Yeast were transformed by the lithium acetate method (23). Strains expressing wild type (TKY368) and F163A mutant (TKY412, tef5-23) forms of eEF1Bα are as described (3, 8). The W130A eEF1Bα mutation was prepared in plasmid pTKB500 (TEF5 LEU2) by PCR mutagenesis using the QuikChange method (Stratagene). Plasmid pTKB377 (F163A) was the template for preparation of W130A/F163A and F163A/K205A eEF1Bα mutations and pTKB526 (K205A) for the W130A/K205A eEF1Bα mutation. The oligonucleotide used for the W130A mutation was 5′-CCATTGTCACTCTAGATGTCAAGCCAGCGGATGATGAAACC-3′ and 5′-CCGATATTGCTGCTATGCAAGCTTTATAAAAGGC-3′ for the K205A mutation. The resulting plasmids pTKB424 (W130A, tef5-24), pTKB425 (W130A/F163A, tef5-25), pTKB1034 (F163A/K205A, tef5-28), and pTKB778 (W130A/K205A, tef5-29) were transformed into strain TKY406 (MATα ura3-52 trp1-Δ101 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 his4-713 tef5::TRP1 pTEF5 URA3). Loss of the wild type TEF5 URA3 plasmid was monitored by growth on complete media containing 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA) (24), to produce isogenic strains TKY443 (W130A), TKY444 (W130A/F163A), and TKY1181 (F163A/K205A). The W130A/K205A eEF1Bα mutant form (pTKB778) could not complement the wild type protein as monitored by its inability to grow on 5-FOA media. The templates for the K205A eEF1Bα mutation were pTKB478 (TEF5 CEN URA3) and pTKB479 (TEF5 2μ URA3), previously described in Ref. 21 and the above oligonucleotides. The resulting plasmids were pTKB1036 (tef5 K205A CEN URA3) and pTKB1048 (tef5 K205A 2μ URA3).

TABLE 1.

S. cerevisiae strains

| Strain | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| TKY368 | MAT α ura3-52 trp1-Δ101 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 his4-713 tef5::TRP1 pTEF5 LEU2 | (3) |

| TKY412 | MAT α ura3-52 trp1-Δ101 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 his4-713 tef5::TRP1 ptef5-23 LEU2 (F163A) | (8) |

| TKY443 | MAT α ura3-52 trp1-Δ101 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 his4-713 tef5::TRP1 ptef5-24 LEU2 (W130A) | This study |

| TKY444 | MAT α ura3-52 trp1-Δ101 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 his4-713 tef5::TRP1 ptef5-25 LEU2 (W130A/F163A) | This study |

| TKY1181 | MAT α ura3-52 trp1-Δ101 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 his4-713 tef5::TRP1 ptef5-26 LEU2 (F163A/K205A) | This study |

| AAY1453 | MAT α ura3-52 trp1 his3-Δ200 pep4::HIS3 prb11.6R can1 leu2-Δ1 GAL MATα ura3-52 trp1 his3-Δ200 pep4::HIS3 prb11.6R can1 LEU2 GAL | (28) |

Growth, Total Translation, and Translation Inhibitor Sensitivity Assays—Growth of strains at the permissive and nonpermissive temperatures were assayed by streaking or spotting equal amounts of 10-fold serially diluted cells at an A600 of 0.5 on YEPD or C-Ura-Leu media at 30 and 38 °C for 2-4 days. The doubling times were determined by diluting cells to an A600 of 0.1 and monitoring the A600 in liquid YEPD media for 12 h. Liquid growth assays were performed using strains grown at 30 °C in complete media to mid-log phase, diluted to an A600 of 0.04, and grown in triplicate with various concentrations of the translation inhibitor hygromycin B in a 96-well microtiter plate. Plates were incubated with shaking at 30 °C and growth was monitored with a BioTek ELx 800 microtiter reader and reported as the mean of triplicate A600 after 20 h. Total yeast translation was monitored by in vivo [35S]methionine incorporation as previously described (25). All time points were analyzed in triplicate, and the data are represented as % relative to wild-type incorporation (cpm per A600 unit). Standard deviation values were determined for microtiter and total translation assays for a minimum of three data points.

Protein Purification—Wild-type eEF1A was purified from strain TKY368 as previously described (1, 3) with the following adjustments. The dialyzed 500 mm KCl eluate from the S-Sepharose resin was loaded onto CM52 (Whatman). The column was eluted with a salt gradient of buffer 1 (20 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 0.1 mm EDTA, pH 8.0, 25% glycerol, 1 mm dithiothreitol, and 0.2 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) with 50 mm to 300 mm KCl using a gradient mixer. Fractions containing eEF1A at greater than 95% purity were identified by SDS-PAGE and dialyzed overnight against 10 volumes of buffer 1 with 100 mm KCl. Wild-type actin was purified from AAY1453 according to published procedures (26) with the modifications in Ref. 21.

A pET11d vector expressing the N-terminally His6-tagged eEF1Bα fusion protein (pTKB448) was used to prepare the F163A, W130A, W130A/F163A, and F163A/K205A mutants using the QuikChange method (Stratagene). The resulting plasmids pTKB582 (F163A), pTKB605 (W130A), pTKB581 (W130A/F163A), and pTKB1043 (F163A/K205A) were transformed into Escherichia coli strain BL21. The recombinant protein was purified as described previously in Ref. 3.

Stopped-flow Kinetics Measurements—2′-(or-3′)-O-(N-methylanthraniloyl) guanosine 5′-diphosphate (mant-GDP) was purchased from Molecular Probes and purified as previously described (3). Using a stopped-flow fluorimeter (KinTek), mant-GDP fluorescence was monitored as previously described. One μm eEF1A and 1 μm mantGDP were rapidly mixed with 45 μm GDP and various concentration of eEF1Bα. At least seven fluorescence trace curves were averaged for each condition, and the resulting averaged curves were fitted to a single or double exponential decay Equation 1, calculating the dissociation rate constants and amplitudes using Sigma Plot version 9 (Systat Software, Inc.),

|

(Eq.1) |

where A is the amplitude of each phase, k is the dissociation rate constant of each phase, t is the time, Fo is the final fluorescence value, and F is the fluorescence.

Actin Bundling and Phalloidin Staining—Bundling assays were performed by adaptations of procedures previously described (20). eEF1A and wild type or mutant His-tagged eEF1Bα forms were dialyzed into buffer 2 (20 mm HEPES, pH 7.2, 2 mm EGTA, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 1 mm ATP, 2 mm MgCl2, 0.25 mm GDP, and 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) for 4 h at 4 °C. Purified G-actin was clarified by centrifugation at 130,000 × g in a Beckman Optima™ TLX Ultracentrifuge for 40 min at 4 °C. G-actin (3 μm) was added to buffer 2 followed by the addition of wild type or mutant eEF1Bα (0.6 μm) and eEF1A (0.3 μm) to a total volume of 100 μl. This mixture was incubated for 18-20 h at 4 °C to allow equilibration. 50 μl of the mixture was centrifuged at low speed (50,000 × g; 36,000 rpm in Beckman Optima™ TLX Ultracentrifuge) for 2 min at 4 °C to assay bundling. Supernatants and pellets were separated in a SDS-PAGE gel and stained with GelCode Blue (Pierce). The densitometry analysis was performed using Image J (Java). Representative data from one of several independent experiments are shown, and standard deviation values were calculated using a minimum of three independent data sets.

Fixation, staining, and sample preparation for yeast strains grown in YEPD for 16 h in log phase by continual dilution at 30 °C was performed as previously described (18). Cell size populations were quantified using at least one hundred cells counted from at least five different fields in five independent experiments. Graphs are plotted as the average number of cells per size range and show standard deviation values.

RESULTS

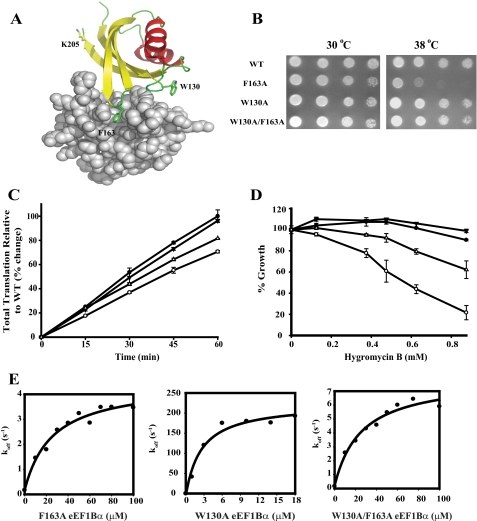

Growth Defects of a F163A eEF1Bα Mutation Can Be Suppressed with a Second eEF1Bα Mutation—The co-crystal x-ray structure of S. cerevisiae eEF1A with the C terminus of eEF1Bα shows that Phe-163 of eEF1Bα is positioned in a hydrophobic pocket of domain II of eEF1A, which indicates its role in complex formation between eEF1Bα and eEF1A (Fig. 1A) (8). This interaction is likely a prerequisite, but an indirect requirement, for efficient nucleotide exchange activity. To address the significance of eEF1Bα Phe-163 in eEF1A binding, this residue was mutated to alanine providing a mutant form that is functional as the only copy of eEF1Bα. However, the resulting strain displayed a Ts- phenotype (Fig. 1B), reduced translation rates (Fig. 1C), and sensitivity to translation elongation inhibitors (Fig. 1D) (8). The doubling times at the permissive temperature in YEPD media reveal that the F163A strain has a 26% reduction of growth compared with a wild-type strain (3.8 ± 0.3 h versus 2.8 ± 0.1 h). Because F163A was not a lethal mutation; it was hypothesized that another residue may contribute to the binding interface with eEF1A. Three conserved loops of eEF1Bα are in close proximity to the hydrophobic pocket of domain II of eEF1A (8) (Fig. 1A). Phe-163 and Trp-130 of eEF1Bα are on neighboring loops of the same binding interface (Fig. 1A). To test for a potential overlapping function with Phe-163, the single W130A and W130A/F163A double mutants were prepared and analyzed in vivo. Both mutant forms were functional as the only form of the eEF1Bα protein and the resulting strains did not display any growth defects at 38 °C (Fig. 1B). The doubling times at permissive temperature of both W130A and W130A/F163A eEF1Bα mutant strains were equivalent to the wild type strain (2.7 ± 0.1 h). Because F163A alone has a Ts- defect, these results indicate that W130A completely suppresses the growth defect conferred by the F163A mutant. Strains expressing each of these mutant forms of eEF1Bα were analyzed by Western blot analysis with an eEF1Bα polyclonal antibody and each protein form was stably expressed at 30 and 38 °C (data not shown). Therefore, the growth phenotype was not due to reduced protein expression or stability.

FIGURE 1.

W130A acts as an intragenic suppressor of the F163A eEF1Bα mutant by partially restoring the nucleotide exchange activity, but not eEF1A binding defect. A, binding interface between the C terminus (amino acids 117-206) of eEF1Bα and eEF1A domain II. Three eEF1Bα loops (green) in close proximity to eEF1A domain II (gray), which contains the stick representation of residues analyzed. The figure was prepared with the PyMol program (27) using PDB coordinates 1F60 (8). Strains containing a deletion of the chromosomal gene encoding eEF1Bα (tef5::TRP1) with a plasmid expressing TEF5 (WT,•), tef5-23 (F163A,○), tef5-24 (W130A, ▾), or tef5-25 (W130A/F163A, Δ) were analyzed for growth (B), total protein synthesis (C), and drug sensitivity (D). B, cells were grown in liquid YEPD to mid-log phase at 30 °C, diluted to an A600 of 0.5, serially diluted 10-fold, spotted on YEPD plates, and incubated at the indicated temperatures for 2-3 days. C, total [35S]methionine incorporation was performed as previously described (25) with strains as in panel B. Data are presented as 35S total incorporation relative to wild type with standard deviation values shown. D, strains as in panel B were grown to mid-log phase at 30 °C in C-media, diluted to an A600 of 0.04, and grown in triplicate with the indicated concentration of hygromycin B. After 20 h of incubation at 30 °C, percent growth was determined by the A600 with drug compared with the A600 without drug with standard deviation values shown. E, using stopped-flow kinetics, an eEF1A (1 μm)-mantGDP (1 μm) complex in binding buffer containing 5 mm Mg2+ was rapidly mixed with a solution containing excess GDP (45 μm) and various concentrations of F163A, W130A, or W130A/F163A eEF1Bα to reach saturating conditions. A time course of fluorescence intensity was monitored for each eEF1Bα concentration, and the data fitted to a single or double exponential decay equation to calculate the dissociation rate constants (•). A hyperbolic equation was used to fit the given dissociation rate constants to calculate the Kd (μm) and koff (s-1) of F163A: Kd = 25.7 ± 6.9, koff = 4.3 ± 0.3, W130A: Kd = 2.6 ± 0.9, koff = 230.9 ± 20, and W130A/F163A: Kd = 25.5 ± 7, koff = 7.8 ± 0.6.

The W130A Suppressor Only Partially Corrects the Translation Elongation Function of the F163A eEF1Bα Mutant Independent of an eEF1A Binding Defect—To determine if the intragenic suppression of the F163A growth defect by W130A is linked to the translation function of eEF1Bα, strains expressing wild-type or mutant forms of the protein were examined for an effect on total protein synthesis by [35S]methionine incorporation. The F163A eEF1Bα mutant strain shows a 30% reduction in total translation at the permissive temperature (8) (Fig. 1C). The W130A mutant alone conferred no translation defect, correlating with the lack of a growth phenotype (Fig. 1C). The double mutant W130A/F163A only partially suppresses the F163A translational defect (Fig. 1C). Translation defects were further analyzed by observing the sensitivity of the eEF1Bα mutant strains to the translation elongation inhibitor hygromycin B using a liquid microtiter growth assay. The strain expressing W130A/F163A eEF1Bα showed resistance to this inhibitor intermediate between the F163A and wild-type eEF1Bα strains (Fig. 1D). These data indicate that the complete growth suppression of the F163A mutation observed in a W130A/F163A double mutant strain is only partially due to suppressing the effects on protein biosynthesis.

To examine if the eEF1Bα mutations alter nucleotide exchange activity, and in particular if the suppression of the F163A growth defect by W130A is due to enhanced GDP release from eEF1A, stopped flow kinetic analysis was performed. The rate of GDP release over time from eEF1A in the presence of 5 mm Mg2+, excess GDP and different forms of eEF1Bα was determined. To reach saturating conditions and determine the maximal dissociation rate constant of the mantGDP:eEF1A complex catalyzed by the eEF1Bα mutants, experiments were performed with varying concentrations of eEF1Bα. The dissociation rate constants were plotted against the eEF1Bα concentration and fitted to a hyperbolic curve to obtain the apparent equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd) of the eEF1A:eEF1Bα complex and the maximal dissociation rate constant (koff) values of GDP (Table 2 and Fig. 1E). The maximal dissociation rate constant of the mantGDP: eEF1A complex under saturating conditions of the F163A mutant form of eEF1Bα is 4.3 ± 0.3 s-1 (Fig. 1E), which is 28-fold slower than the wild-type complex (122 ± 8 s-1) (3). This is likely the result of a 6.5-fold increase in the Kd for eEF1A (25.7 ± 6.9 μm) compared with wild-type eEF1Bα (4 ± 0.8 μm) (3) (Fig. 1E). On the other hand, the W130A mutant form enhances the mantGDP dissociation rate by 2-fold (230.9 ± 20 s-1) compared with the wild-type protein (Fig. 1E). The apparent Kd value of the W130A form for the mantGDP:eEF1A complex is 2.6 ± 0.9 μm, which is essentially the same as wild-type eEF1Bα. The F163A/W130A double mutant suppresses the F163A GDP release activity 2-fold (7.8 ± 0.6 s-1) in the presence of 5 mm Mg2+ (Fig. 1E). The Kd value of the W130A/F163A for the mantGDP:eEF1A complex, however, is 25.5 ± 7 μm (Fig. 1E). This is equivalent to the F163A eEF1Bα:eEF1A complex. Together, these results argue that F163 of eEF1Bα is important for binding stability to eEF1A domain II while W130A partially restores the reduced rate at which the F163A eEF1Bα catalyzes GDP release from eEF1A.

TABLE 2.

Stopped-flow kinetics values for different forms of the eEF1A:eEF1Bα complex

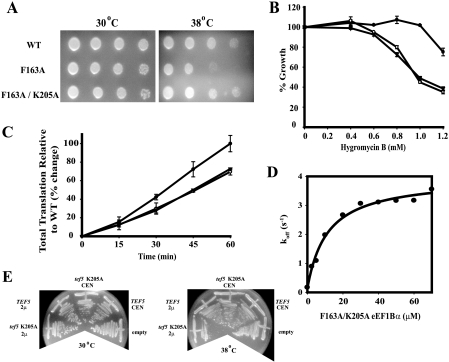

The Reduced Affinity of the F163A Mutation for eEF1A Suppresses the Inviable K205A eEF1Bα Mutation—Previous studies established that Lys-205 of eEF1Bα plays a significant role in displacing the Mg2+ ion during the nucleotide exchange reaction and a K205A mutation is lethal in vivo as the only form of eEF1Bα (8). Interestingly, comparing the above maximal koff result for the F163A mutation (4.3 s-1, Fig. 1E) to the published stopped-flow analysis for K205A eEF1Bα mutant, indicates that the inviable K205A mutant has a higher maximal koff for GDP of 8.0 s-1 (3) in the presence of 5 mm Mg2+ (Table 2). Even at various Mg2+ concentrations, the dissociation rate constants of mantGDP from eEF1A:K205A eEF1Bα are always higher when compared with the complex with F163A eEF1Bα (data not shown). These findings support the hypothesis that the lethal phenotype of K205A is not solely due to reduced exchange activity of eEF1Bα, but rather due to the 10-fold reduction in the Kd for eEF1A (3). Thus, we propose that tight binding of K205A eEF1Bα to eEF1A would be suppressed by adding the F163A mutation, which would increase the Kd for eEF1A. The F163A/K205A eEF1Bα double mutant, unlike K205A alone, is functional as the only form of eEF1Bα (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, the F163A/K205A double mutant did not exhibit the Ts- phenotype seen for to the F163A mutant. To confirm this model, the W130A mutation which does not result in reduced eEF1A binding was combined with the K205A mutant, but viability was not restored (data not shown). To determine whether the increased growth of the F163A/K205A eEF1Bα strain compared with a F163A single mutant is due to suppression of a translation function, we measured hygromycin B sensitivity and [35S]methionine incorporation. Interestingly, in both assays the F163A/K205A mutant strain displays similar protein synthesis defects to the F163A single mutant strain (Fig. 2, B and C), suggesting that the lethality of the Lys-205 mutation is due to altering an eEF1A function other than translation.

FIGURE 2.

The F163A eEF1Bα mutation acts as an intragenic suppressor of the lethal K205A eEF1Bα mutation while K205A eEF1Bα overexpression causes a dominant negative phenotype. A, strains expressing eEF1Bα forms: wild type-•, F163A-○, and F163A/K205A-▾ strains were grown to mid-log phase at 30 °C in YEPD liquid, diluted to an equivalent A600 of 0.5, spotted as 10-fold serial dilutions on YEPD plates, and grown at 30 and 38 °C for 2-4 days. Strains as in panel A were assayed for (B) hygromycin sensitivity and (C)[35S]methionine incorporation with standard deviation values shown. D, using stopped-flow kinetics, the eEF1A:mantGDP complex (1 μm each) complex in binding buffer containing 5 mm Mg2+ was rapidly mixed with a solution containing 45 μm GDP and various concentrations of F163A/K205A eEF1Bα to reach saturating conditions and analyzed as in Fig. 1. A hyperbolic equation was used to fit the given dissociation rate constants to calculate a Kd of 11.4 ± 2.1 μm and maximal koff of 3.8 ± 0.2 s-1. E, wild-type strain TKY368 was transformed with either pRS316 (empty), pTKB478 (TEF5 CEN), pTKB1036 (tef5 K205A CEN), pTKB479 (TEF5 2μ), pTKB1048 (tef5 K205A 2μ). Cells were grown on C-Ura-Leu media at 30 and 38 °C for 3-4 days.

To confirm that the increased growth of the K205A/F163A mutant strain compared with the F163A single mutant strain is not due an altered translation-related GEF function of eEF1Bα, stopped-flow analysis was performed as described above. In the presence of 5 mm Mg2+, the maximal dissociation rate constant of GDP from the eEF1A:F163A/K205A eEF1Bα complex is 3.8 ± 0.2 s-1 (Fig. 2D), which is equivalent to the single F163A mutant complex (4.3 ± 0.3 s-1, Fig. 1E) (Table 2). On the other hand, as predicted the Kd value for the F163A/K205A eEF1Bα: eEF1A complex increased 28-fold (11.3 ± 2.1 μm) compared with the K205A eEF1Bα:eEF1A complex (0.4 ± 0.1 μm) (Table 2). These results indicate that increased growth of the F163A/K205A eEF1Bα double mutant strain compared with a F163A strain is not due to the restoration of nucleotide exchange activity of eEF1A. More likely, it suppresses a function not yet assigned eEF1Bα.

Overexpression of the K205A eEF1Bα Mutant Confers a Dominant Negative Phenotype—Because the K205A eEF1Bα mutation causes inviability, which appears to be due to its tight affinity for eEF1A, we analyzed how excess levels of this eEF1Bα mutation would affect the growth of a wild-type strain (Fig. 2E). Low copy-(CEN) and high copy-(2μ)-based plasmids expressing either the wild type or K205A eEF1Bα were transformed into a wild-type strain. Overexpression of either the wild type or mutant form of eEF1Bα on a CEN plasmid showed no effect on cell growth at 30 or 38 °C. However, the K205A eEF1Bα mutation on a 2μ plasmid causes much slower growth at 38 °C compared with the overexpression of the wild-type protein (Fig. 2E). Based on these findings, we hypothesize that the overexpression of the tight binding K205A mutant affects the availability of eEF1A to interact with actin, thereby decreasing actin bundling.

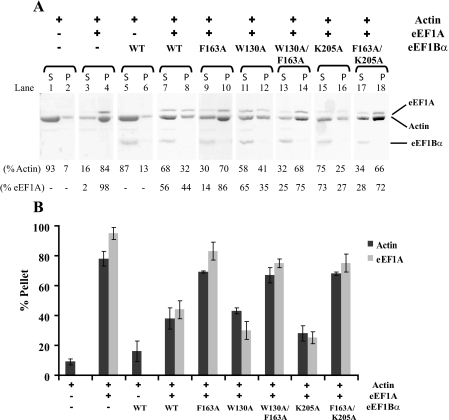

eEF1Bα Reduced Actin Bundling by eEF1A in Vitro—Because the eEF1Bα and proposed aa-tRNA binding sites in eEF1A physically overlap, we hypothesized that eEF1Bα binding, like aa-tRNA (20), is mutually exclusive with eEF1A-induced actin bundling. To test this hypothesis, the ability of eEF1A to bundle actin in the absence and presence of different forms of eEF1Bα in vitro was analyzed using an established cosedimentation assay (18). After centrifugation, actin levels present in the pellet indicate bundling activity. Representative data from one of several independent experiments is shown in Fig. 3A. Densitometry analysis was performed for all experiments and the percentage of actin and eEF1A in the pellet was plotted as a bar graph with standard deviations (Fig. 3B). As an experimental control, purified actin alone was unable to bundle, with only 7% of total actin in the pellet after centrifugation (Fig. 3A, lane 1). The addition of eEF1A enhanced actin bundling, yielding 78 ± 5% of actin and 95 ± 4% of eEF1A in the pellet (Fig. 3A, lanes 3 and 4 and B). Unlike eEF1A, eEF1Bα protein did not confer an actin bundling function as 13% of actin was recovered in the pellet (Fig. 3, lanes 5 and 6). Similar to aa-tRNA (20), in the presence of an 2-fold molar excess of wild-type eEF1Bα to eEF1A, the actin bundling activity of eEF1A was inhibited as the fraction of both actin and eEF1A in the pellet decreased more than 45% when compared with eEF1A alone (Fig. 3B).

FIGURE 3.

The interaction between eEF1A and eEF1Bα reduces actin bundling in vitro. Actin bundling assays were performed with various purified yeast protein combinations of actin, eEF1A, and His-tagged eEF1Bα forms. Actin polymerized in the presence of indicated protein(s) was analyzed followed by centrifugation. A, supernatants (S) and pellets (P) of each experiment were resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE and stained with GelCode Blue to observe the position of actin, eEF1A, and eEF1Bα. Pellets containing actin indicates its bundling. The intensity of the band signal was reported as a percentage of the total (supernatant and pellet) using Image J. B, band intensities of three or more independent experiments were plotted as a percentage for actin and eEF1A pellet of the total protein input and standard deviation values are provided.

Mutant Forms of eEF1Bα Affect Actin Organization—To examine the effect of altered binding by eEF1Bα to eEF1A, actin bundling was monitored in the presence of eEF1Bα mutant proteins. The F163A and W130A/F163A eEF1Bα mutant proteins, which displayed lower but essentially equivalent affinity for eEF1A (Kd of ∼25 μm for eEF1A) compared with 4 μm for the wild-type eEF1Bα (3), allowed greater eEF1A-induced actin bundling than wild-type eEF1Bα. In the presence of either eEF1Bα mutant, the pellet contained about 70 and 80% of actin and eEF1A, respectively (Fig. 3A, lanes 9, 10, and 13, 14 and 3B). These data suggest that the growth defect of the F163A mutant strain is linked to two mechanisms: the negative consequence of overbundling of actin by eEF1A and reduction of the GDP release reaction during translation elongation. In contrast, there was no significant change in the bundling of actin by eEF1A in the presence of the W130A or K205A eEF1Bα mutant protein when compared with the presence of wild-type eEF1Bα protein, where 43 ± 2%, 28 ± 5%, and 38 ± 7%, respectively, of total actin was in the pellet (Fig. 3, A, lanes 11, 12, and 15, 16 and B). These data verify that if the affinity of the eEF1Bα protein for eEF1A is equivalent or higher than the wild-type complex (2.6 μm for W130A and 0.4 μm for K205A (3), then eEF1Bα has the ability to disrupt the actin bundling function of eEF1A (Fig. 3B). Next, we examined eEF1A-induced actin bundling in the presence of the F163A/K205A eEF1Bα mutant. When compared with the K205A mutation that disrupts eEF1A-induced actin bundling, the F163A/K205A mutant allows more than twice as much actin to pellet (Fig. 3A, lanes 15-18 and B). This observation is consistent with the lower affinity of F163A/K205A (Kd of 11.4 μm) for eEF1A relative to wild-type complex, and indicates suppression of the lethal K205A mutant likely occurs from reduced eEF1A binding which also affects the availability of eEF1A to bind and bundle actin.

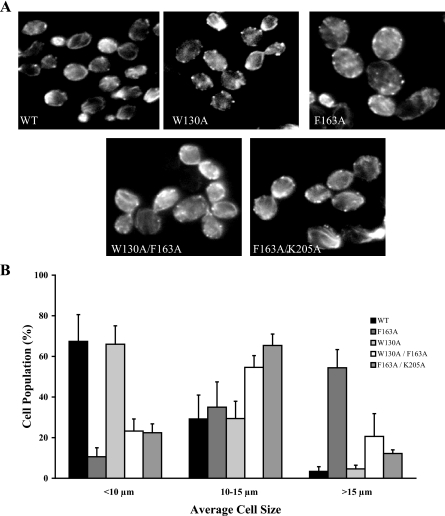

eEF1Bα Mutants Show Differences in Cell Morphology—Because eEF1Bα affects eEF1A-induced actin bundling activity in vitro, rhodamine phalloidin staining was used to evaluate the downstream effect of eEF1Bα mutations on actin organization and cell morphology. Yeast cells expressing the wild type and W130A mutant forms of eEF1Bα demonstrated normal actin staining displaying attributes such as patches and cables (Fig. 4A). More than 65% of the wild-type cell population was of normal size (10 μm or less) while a very small proportion of the cells (<5%) were larger than 15 μm in diameter (Fig. 4B). In contrast, a drastic change in morphology was observed in the strain expressing the F163A single mutation. More than half of the cell population was larger than 15 μm, which is 6-fold higher than cells expressing wild-type eEF1Bα protein (Fig. 4B). Intriguingly, the F163A eEF1Bα mutant strain displays a phenotype of slower growth, increased cell size, and loss of actin cables and patches which is similar to eEF1A-overexpressing cells and actin bundling-deficient eEF1A mutations (18, 21). These data suggest that correct stoichiometry of the actin:eEF1A and eEF1Bα:eEF1A complexes is important for cell morphology as well as cell growth. Strains expressing the eEF1Bα double mutants W130A/F163A or F163A/K205A also exhibit altered morphology. However, both double mutant strains showed a reduced population of cells in 15 μm or greater size range 3-6-fold compared with the F163A strain (Fig. 4A). These results confirm that these intragenic mutations can improve the growth defect of F163A eEF1Bα unrelated to its translation function.

FIGURE 4.

The F163A eEF1Bα mutant strain displays a cell morphology defect suppressed by the W130A or K205A mutation. A, strains expressing WT or mutant eEF1Bα forms: wild type, F163A, W130A, W130A/F163A, and K205A/F163A were stained with rhodamine phalloidin prior to mounting. Images were captured with an IX70 Olympus inverted fluorescence microscope equipped with a planapochromatic 100× oil immersion objective lens. B, cells from above strains were scored as large (>15 μm), medium (10-15 μm), and small (<10 μm) sizes and plotted as a percentage of the total population for a minimum of 100 cells with standard deviation values shown.

DISCUSSION

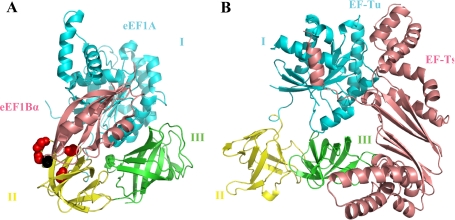

Translation elongation requires the activity of a classic G-protein, eEF1A, for aa-tRNA binding and delivery to the ribosome. In addition, eEF1A is an actin bundling protein whose functions are required for cell survival. Alteration of this later interaction does not appear to effect translation elongation (18, 19). eEF1A also interacts with the essential guanine nucleotide exchange factor eEF1Bα to maintain its active GTP-bound pool. These translation and cytoskeletal eEF1A functions appear to be in conflict, because aa-tRNA and actin interactions are mutually exclusive. Thus, eEF1Bα can alter the distribution of eEF1A between translational and non-canonical functions. Evolutionarily, this is particularly important because despite the high degree of sequence and structural conservation between eEF1A, EF-Tu, and EF-Tumt; there is a major difference in how these proteins form a complex with their GEFs (8, 10, 11). To achieve guanine nucleotide exchange catalysis, all three GEFs bind to domain I as this region consists of the conserved G-domains and Mg2+ binding site (Fig. 5). However, eEF1Bα creates a distinct binding interface with domain II of eEF1A while EF-Ts and EF-Tsmt bind to domain III of EF-Tu and EF-Tumt, respectively. The selective pressure that resulted in eEF1Bα binding to domain II, and not domain III of eEF1A, is unclear. Unlike eEF1A, there is no obligation for EF-Tu and EF-Tumt to interact with the actin cytoskeleton. Based on the overlapping functions of eEF1A domain II in actin, aa-tRNA and eEF1Bα binding; it is likely that this domain is the “balancer” to differentiate between the dual functions of eEF1A: translation elongation and actin organization.

FIGURE 5.

eEF1A and EF-Tu binds their GEFs in a fundamentally different manner, leading to a novel eEF1Bα function of modulating actin bundling by eEF1A. A, co-crystal structure of yeast eEF1A and the catalytic domain of eEF1Bα (117-206 amino acids) highlighting eEF1A (red spheres) and eEF1Bα residues (black spheres) that are important for actin bundling activity and eEF1A binding, respectively and B, E. coli EF-Tu and EF-Ts complex. Domain I (cyan) of eEF1A contains the G-domains and Mg2+ binding site as domain II (yellow) contains the proposed aa-tRNA binding site. eEF1Bα (salmon) binds to domains I and II and has no contacts with domain III (green) whereas EF-Ts (salmon) bind to domain I and III and has no contacts with domain II. The figure was prepared with the PyMol program (27) using PDB coordinates 1F60 (8) and 1EFU (10).

As domain II of eEF1A forms a hydrophobic pocket that accommodates the Phe-163 residue of eEF1Bα, kinetic data on the F163A mutation confirm that this residue is crucial for binding to eEF1A. The F163A eEF1Bα strongly reduces the exchange activity 28-fold, possibly due to its altered eEF1A affinity. Interestingly, a W130A/F163A double mutant completely suppresses the effects of F163A on cell growth. However, the W130A mutation only increases GEF activity 2-fold and does not correct the eEF1A binding defect of F163A eEF1Bα (Fig. 1E and Table 2). It is clear, however, that the eEF1Bα catalyzed koff for GDP is not the sole determinant for viability, as the inviable K205A mutant has essentially the same activity as some viable mutants. Structural analysis of the eEF1A domain II and eEF1Bα binding interface indicates that the W130A mutant could cause removal of hydrogen bond constraints between two of the conserved eEF1Bα loops, where Trp-130 interacts with Glu-192 and His-194. This may allow greater flexibility in the eEF1Bα protein to suppress the loss of F163A function. The F163A/W130A mutant also only shows a partial restoration of the translational defects of the single F163A mutant strain. These results suggest that the growth phenotype of the F163A mutant is linked to another cellular function of eEF1Bα as this intragenic suppressor has the ability to improve the end result of actin organization (Fig. 4).

Intriguingly, the F163A mutant can suppress the lethality of the K205A mutant. This intragenic suppression is not due to restoration of the koff for GDP from eEF1A. However, F163A drastically reduces the affinity of K205A eEF1Bα for eEF1A. Based on these results and the fact that eEF1Bα binding site overlaps with mutations in domain II of eEF1A that are deficient in bundling actin in vitro (18, 19) (Fig. 5A), we hypothesized that eEF1Bα may help modulate the non-canonical function of eEF1A in actin bundling. eEF1Bα displayed the ability to prevent eEF1A association with actin bundles (Fig. 3B), which is consistent with the dynamic model that eEF1A bound to aa-tRNA or eEF1Bα functions exclusively in translation elongation as eEF1A is sequestered from the actin cytoskeleton. To support this model, eEF1Bα mutants that have lower affinity for eEF1A could not prevent formation of actin bundles. Furthermore, the two double mutants of F163A suppress at least partially the increased cell size phenotype of the single mutant. Because reducing the rate of total translation via elongation factor mutants does not alter cell morphology or the cytoskeleton (19), these in vivo effects are due to actin bundling changes by eEF1A (Fig. 4). Given that both nucleotide-bound states of eEF1A interact with actin (17) and the ratio of eEF1Bα to eEF1A is thought to be between 1:5 and 1:10, we propose that eEF1Bα prevents inappropriate actin bundling of the GDP-bound pool of eEF1A while stabilizing the GTP: eEF1A complex so eEF1A can bind aa-tRNA and not actin. Thus, suppression of the lethality of the K205A eEF1Bα mutation by the F163A mutation correlates with eEF1A binding and actin bundling and not GEF activity during translation elongation. Taken together, these data establish that eEF1Bα likely plays a key role in distributing eEF1A between its two functions.

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the Kinzy laboratory especially Patrick McGovern, Peter Cathcart from the Kandl laboratory, and Drs. Paul Copeland (UMDNJ-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School), Estela Jacinto (UMDNJ-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School), and Stephane Gross (Liverpool John Moores University) for helpful comments.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 GM57483 (to T. G. K.) and F31 A126530 (to Y. R. P.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: eEF, eukaryotic translation elongation factor; aa-tRNA, aminoacyl-tRNA; mant-GDP, 2′-(or-3′)-O-(N-methylanthraniloyl) guanosine 5′-diphosphate; PDB, Protein Data Bank.

References

- 1.Carvalho, M. G., Carvalho, J. F., and Merrick, W. C. (1984) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 234 603-611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bourne, H. R., Sanders, D. A., and McCormick, F. (1991) Nature 349 117-127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pittman, Y., Valente, L., Jeppesen, M. G., Andersen, G. R., Patel, S., and Kinzy, T. G. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 19457-19468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saha, S. K., and Chakraburtty, K. (1986) J. Biol. Chem. 261 12599-12603 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slobin, L. I., and Moller, W. (1978) Eur. J. Biochem. 84 69-77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janssen, G. M. C., and Moller, W. (1988) J. Biol. Chem. 263 1773-1778 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kinzy, T. G., Ripmaster, T. R., and Woolford, J. L., Jr. (1994) Nucleic Acids Res. 22 2703-2707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andersen, G. R., Pedersen, L., Valente, L., Chatterjee, I., Kinzy, T. G., Kjeldgaard, M., and Nyborg, J. (2000) Mol. Cell 6 1261-1266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andersen, G. R., Valente, L., Pedersen, L., Kinzy, T. G., and Nyborg, J. (2001) Nat. Struct. Biol. 8 531-534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawashima, T., Berthet-Colominas, C., Wulff, M., Cusack, S., and Leberman, R. (1996) Nature 379 511-518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeppesen, M. G., Navratil, T., Spremulli, L. L., and Nyborg, J. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 5071-5081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nissen, P., Kjeldgaard, M., Thirup, S., Polekhina, G., Reshetnikova, L., Clark, B. F. C., and Nyborg, J. (1995) Science 270 1464-1472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kinzy, T. G., Freeman, J. P., Johnson, A. E., and Merrick, W. C. (1992) J. Biol. Chem. 267 1623-1632 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anand, M., Valente, L., Carr-Schmid, A., Munshi, R., Olarewaju, O., Ortiz, P. A., and Kinzy, T. G. (2001) Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 66 439-448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dinman, J. D., and Kinzy, T. G. (1997) RNA 3 870-881 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang, F., Demma, M., Warren, V., Dharmawardhane, S., and Condeelis, J. (1990) Nature 347 494-496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edmonds, B. T., Bell, A., Wyckoff, J., Condeelis, J., and Leyh, T. S. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273 10288-10295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gross, S. R., and Kinzy, T. G. (2005) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12 772-778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gross, S. R., and Kinzy, T. G. (2007) Mol. Cell. Biol. 27 1974-1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu, G., Tang, J., Edmonds, B. T., Murray, J., Levin, S., and Condeelis, J. (1996) J. Cell Biol. 135 953-963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Munshi, R., Kandl, K. A., Carr-Schmid, A., Whitacre, J. L., Adams, A. E., and Kinzy, T. G. (2001) Genetics 157 1425-1436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burke, D., Dawson, D., and Stearns, T. (2000) Methods in Yeast Genetics: A Laboratory Course Manual, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY

- 23.Ito, H., Fukuda, Y., Murata, K., and Kimura, A. (1983) J. Bacteriol. 153 163-168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boeke, J. D., Trueheart, J., Natsoulis, G., and Fink, G. R. (1987) Methods Enzymol. 154 164-175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carr-Schmid, A., Valente, L., Loik, V. I., Williams, T., Starita, L. M., and Kinzy, T. G. (1999) Mol. Cell. Biol. 19 5257-5266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Honts, J. E., Sandrock, T. S., Brower, S. M., O'Dell, J. L., and Adams, A. E. M. (1994) J. Cell Biol. 126 413-422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DeLano, W. L. (2002) The PyMOL User's Manual

- 28.Jones, E. W. (1991) in Guide to Yeast Genetics and Molecular Biology (Guthrie, C., and Fink, G. R., eds) pp. 428-453, Academic Press, New York