Abstract

Many human diseases are caused by missense substitutions that result in misfolded proteins that lack biological function. Here we express a mutant form of the human cystathionine β-synthase protein, I278T, in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and show that it is possible to dramatically restore protein stability and enzymatic function by manipulation of the cellular chaperone environment. We demonstrate that Hsp70 and Hsp26 bind specifically to I278T but that these chaperones have opposite biological effects. Ethanol treatment induces Hsp70 and causes increased activity and steady-state levels of I278T. Deletion of the SSA2 gene, which encodes a cytoplasmic isoform of Hsp70, eliminates the ability of ethanol to restore function, indicating that Hsp70 plays a positive role in proper I278T folding. In contrast, deletion of HSP26 results in increased I278T protein and activity, whereas overexpression of Hsp26 results in reduced I278T protein. The Hsp26-I278T complex is degraded via a ubiquitin/proteosome-dependent mechanism. Based on these results we propose a novel model in which the ratio of Hsp70 and Hsp26 determines whether misfolded proteins will either be refolded or degraded.

Cells have evolved quality control systems for misfolded proteins, consisting of molecular chaperones (heat shock proteins) and proteases. These molecules help prevent misfolding and aggregation by either promoting refolding or by degrading misfolded protein molecules (1). In eukaryotic cells, the Hsp70 system plays a critical role in mediating protein folding. Hsp70 protein interacts with misfolded polypeptides along with co-chaperones and promotes refolding by repeated cycles of binding and release requiring the hydrolysis of ATP (2). Small heat shock proteins (sHsp)2 are small molecular weight chaperones that bind non-native proteins in an oligomeric complex and whose function is poorly understood (3). In mammalian cells, the sHsp family includes the α-crystallins, whose orthologue in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is Hsp26. Studies suggest that Hsp26 binding to misfolded protein aggregates is a prerequisite for effective disaggregation and refolding by Hsp70 and Hsp104 (4, 5).

Misfolded proteins can result from missense substitutions such as those found in a variety of recessive genetic diseases, including cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) deficiency. CBS is a key enzyme in the trans-sulfuration pathway that converts homocysteine to cysteine (6). Individuals with CBS deficiency have extremely elevated levels of plasma total homocysteine, resulting in a variety of symptoms, including dislocated lenses, osteoporosis, mental retardation, and a greatly increased risk of thrombosis (7). Approximately 80% of the mutations found in CBS-deficient patients are point mutations that are predicted to cause missense substitutions in the CBS protein (8). The most common mutation found in CBS-deficient patients, an isoleucine to threonine substitution at amino acid position 278 (I278T), has been observed in nearly one-quarter of all CBS-deficient patients. Based on the crystal structure of the catalytic core of CBS, this mutation is located in a β-sheet more than 10 Å distant from the catalytic pyridoxal phosphate and does not directly affect the catalytic binding pocket or the dimer interface (9).

Previously, our lab has developed a yeast bioassay for human CBS in which yeast expressing functional human CBS can grow in media lacking cysteine, whereas yeast expressing mutant CBS cannot (10). We have used this assay to characterize the functional effects of many different CBS missense alleles, including I278T (7, 11). However, an unexpected finding was that it was possible to restore function to I278T and a number of other CBS missense mutations by either truncation or the addition of a second missense mutation in the C-terminal regulatory domain (12, 13). The ability to restore function by a cis-acting second mutation suggested to us that it might be possible to restore function in trans via either interaction of mutant CBS with a small molecule (i.e. drug) or a mutation in another yeast gene. In a previous study, we found that small osmolyte chemical chaperones could restore function to mutant CBS presumably by directly stabilizing the mutant CBS protein (14).

In this study we report on the surprising finding that exposure of yeast to ethanol can restore function of I278T CBS by altering the ratio of the molecular chaperones Hsp26 and Hsp70. We demonstrate Hsp70 binding promotes I278T folding and activity, whereas Hsp26 binding promotes I278T degradation via the proteosome. By manipulating the levels of Hsp26 and Hsp70, we are able to show that I278T CBS protein can have enzymatic activity restored to near wild-type levels of activity. Our findings suggest a novel function for sHsps.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Yeast Strains and Plasmids—CBS expressing yeast strains used in this study are derived from WY35 (α leu2 ura3 ade2 trp1 cys4::LEU2) (10). Strains LS1 (α leu2 ura3 ade2 trp1 cys4::LEU2 hsp26::KanMX), LS2 (α leu2 ura3 ade2 trp1 cys4::LEU2 hsp104::KanMX), and LS3 (α leu2 ura3 ade2 trp1 cys4::LEU2 ssa2::KanMX) are isogenic derivatives of Wy35 created by insertion of a disruption cassette as described below. The yeast ubiquitin assay strains LS4 and LS5 were derived from RJD3269 (MATa, uba1Δ::KanMX [pRS313-uba1-204-HIS], can1-100, leu2-3, -112, his3-11, -15, trp1-1, ura3-1, ade2-1) and RJD3270 (uba1Δ::KanMX [pRS313-UBA1], ura3::PGAL-SIC1HA-URA3), respectively (15). These were created by introduction of the cys4::LEU2 cassette as described previously (10). Gene replacements and expression of phI278T were verified by Western blot and functional assay. SSC1, SSA2, SSA3, SSA4, SSE1, SSE2, SSB1, SSQ1, SSZ1, LHS1, ECM10, and SSA1 deletion strains were obtained from the yeast deletion strain library (16).

The CBS expression plasmids phCBS and pI278T were all made as described previously and are 2-μm-based plasmids with a TRP1 marker and express CBS from the yeast TDH1 promoter (7). To make the pHsp26 overexpression plasmid, the HSP26 gene was PCR-amplified with primers 5′-CGTTGGACTTTTTTTAATATAACCTAC (forward) and 5′-CTTTGGCGCTACGTATTTCTGCATTTTC (reverse), and the product was then digested with SpeI and HincII and cloned into expression vector pRS426.

Deletion of HSP26, SSA2, and HSP104—Disruption cassettes were created by PCR amplification of total DNA of the HSP26, SSA2, and HSP104 deletion strains from the Yeast Genome Deletion Project using A and D primers. The PCR product was transformed by the lithium acetate procedure into the recipient yeast strain, WY35. Transformants were selected on SC-trp media, and gene replacement was verified by Western analysis.

Yeast Media and Growth—Synthetic complete media lacking cysteine (SC–Cys) and histidine (SC–His) were made as described (17). SC+Cys media were made by adding glutathione to the indicated SC media at a final concentration of 30 μg/ml. All chemicals were purchased from Sigma. For cell growth assays, saturated cultures were diluted to an A600 of 0.05 in standard 15-ml borosilicate tubes containing 3 ml of media. Cells were then grown at 30 °C with aeration. After 24 h A600 was determined using a Milton Roy Spectronic 601 spectrophotometer (Ivyland, PA).

Quantitative Reverse Transcription-PCR—RNA was extracted from the yeast cells using RNeasy mini kit from QIAGEN (catalogue number 74104). A total of 100 ng of RNA was used for Taq Man gene expression analysis using two probes, one for human CBS (Hs00163925_m1; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and one for 18 S ribosomal RNA (Hs99999901_s1). Quantification of signal was achieved using an Applied Biosystems 7900HT version 2.2.2 sequence detection system. Each sample was assayed in triplicate for both probes.

Extract Preparation and Immunoblot Analysis—Yeast were diluted to an A600 of 0.05 and grown until the A600 was between 0.7 and 0.9 (mid-log phase). Yeast extracts were prepared by mechanical lysis as described previously (12). Protein concentration was determined by the Coomassie Blue protein assay reagent (Pierce) using bovine serum albumin as a standard. For immunoblot analysis, extracts containing 20 μg of total protein were run on precast Tris acetate gel (Bio-Rad) at 15 mA per gel and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane as described (14). For most experiments, immunopurified mouse anti-CBS was purchased from ABNOVA (catalogue number H00000875-A01) and was used at 1/10,000 dilution. For the experiments shown in Figs. 1D and 3D, rabbit polyclonal serum was used (13). Hsp26 polyclonal rabbit antiserum was a generous gift from J. Buchner (18) and was used at a 1/4000 dilution. Hsp104 polyclonal rabbit serum was obtained from AbCAM (catalogue number ab2924) and was used at a 1/5000 dilution. Hsp70 monoclonal mouse serum was also from AbCAM (catalogue number ab5439) and used with at a dilution of 1/5000. α-Tubulin antibody used here is the same as described previously (19). Ubiquitin monoclonal antibody was purchased from Covance (MMS-258R) and used at a 1:1000 dilution. For rabbit antiserum a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary anti-body was used at a 1/30,000 dilution (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA). Signal was detected by chemiluminescence using SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Amersham Biosciences) and Chemigenius station (Syngene); signal was quantitated by Alpha Innotech software.

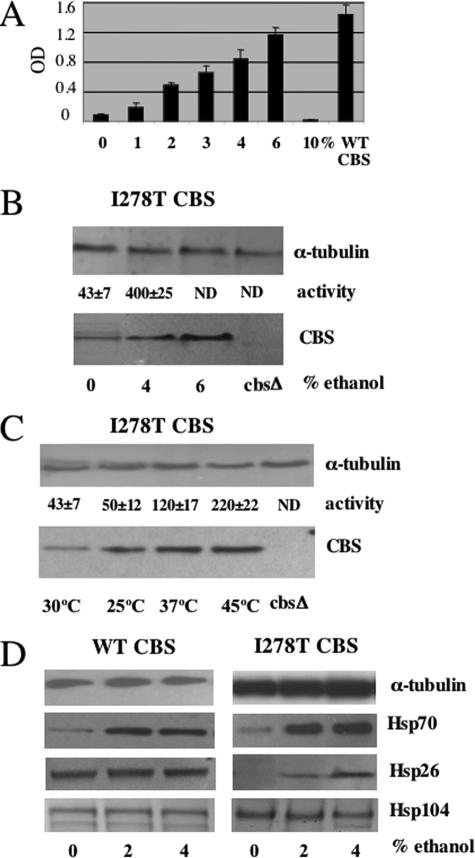

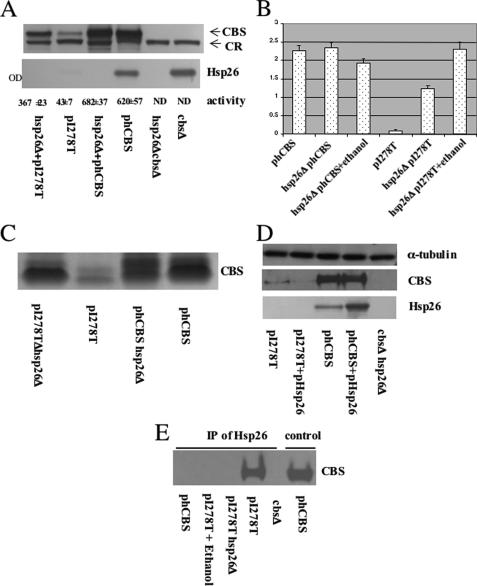

FIGURE 1.

Functional rescue of I278T CBS by chaperone manipulation. A, saturated culture of yeast strain WY35 expressing I278T CBS (WY35 pI278T) was diluted 1:1000 in SC–Cys media with the indicated amount of ethanol at 30 °C for 24 h. Growth was measured by A600 (OD600). All cultures were grown in triplicate with the error bars showing standard deviation. A control strain expressing wild-type human CBS is shown on the right. B, WY35 pI278T cells were grown in SC–Trp+Cys media with the indicated percent of ethanol added to the media. Cells were harvested, and CBS and α-tubulin were assessed by immunoblot. CBS enzyme activity was measured in triplicate with the average and standard deviation shown. The far right lane contains extract from WY35 with no plasmid. ND = not determined. C, heat shock rescue of I278T CBS activity. Yeast strain WY35 pI278T was grown overnight at either 25, 30, or 37 °C, and extracts were assessed for CBS activity and CBS protein by immunoblot as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The yeast labeled 45 °C were exposed to a 3-h heat shock after overnight growth at 37 °C. All experiments were done in triplicate, and standard deviation is shown. D, WY35 phCBS and WY35 pI278T strains were grown in SC–Trp+Cys media with the indicated amount of ethanol overnight. Total lysates were examined for Hsp26, Hsp70, Hsp104, and α-tubulin by immunoblot.

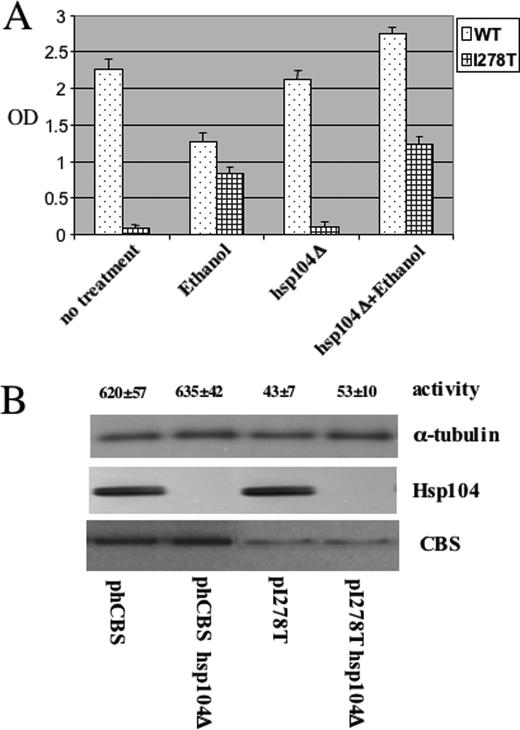

FIGURE 3.

Loss of Hsp104 does not affect I278T function. A, yeast strain LS2 (α leu2 ura3 ade2 trp1 cys4::LEU2 Hsp104::KanMX) was transformed with a plasmid expressing either I278T CBS (pI278T) wild-type human CBS (phCBS). Saturated cultures of the yeast were diluted 1:1000 in SC–Trp–Cys+G418 media and grown with aeration at 30 °C for 24 h in the absence and presence of 4% ethanol. Growth was measured by A600 (OD600). Experiment was done in triplicate, and error bars indicate standard deviation. B, LS2 cells transformed with either phCBS or pI278T were grown in SC–Trp+G418+Glu media. Cells were harvested, and CBS, Hsp104, and α-tubulin were assessed by immunoblot. Extracts were also examined for CBS activity in triplicate.

CBS Enzyme Activity—CBS enzyme activity was measured using a Biochrom 30 amino acid analyzer as described previously (20). Units are nanomoles of cystathionine/h/mg of protein.

Immunoprecipitation—Yeast cells were lysed in 50 mm Hepes, 50 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 50 mm NaF, and 10 mm sodium pyrophosphate buffer supplemented with protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Diagnostics, catalogue number 11 836 153 001). 500 μg of yeast extract was incubated overnight with 50 μl of anti-Hsp26 antibody or 10 μl of CBS antibody. After 4 h the antigen-antibody complexes were treated with 50 μl of protein A-Sepharose beads and incubated overnight. Protein A-Sepharose-isolated immune complexes were washed three times with assay buffer, boiled in SDS-PAGE sample buffer for 5 min, and analyzed by Western blot. The immune complexes were then washed three times with assay buffer, boiled in SDS-PAGE sample buffer for 5 min, and analyzed by Western blot.

RESULTS

Ethanol and Heat Shock Rescues I278T Function—Previously we have shown that yeast lacking endogenous yeast CBS and expressing human I278T are unable to grow in yeast media lacking cysteine (SC–Cys) (10). We found that addition of up to 6% ethanol to standard yeast media allowed growth of I278T expressing yeast in SC–Cys media in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1A). Addition of 10% ethanol resulted in total growth inhibition, but this was also observed in yeast expressing wild-type human CBS (data not shown). Addition of 4% ethanol caused a 280% increase in steady-state levels of I278T protein, as well as a 930% increase in CBS enzyme activity (Fig. 1B). Examination of CBS mRNA levels by quantitative real time PCR showed that ethanol had no effect on mRNA levels (data not shown), indicating that the increase in steady-state I278T levels was because of stabilization of the protein. As it has been shown previously that certain heat shock genes are up-regulated upon ethanol stress in S. cerevisiae (21), we hypothesized that heat shock proteins might somehow mediate this effect. Consistent with this idea, we found that exposure of I278T yeast to a 45 °C heat shock for 3 h resulted in a 312% increase in steady-state CBS and a 511% increase in CBS activity (Fig. 1C). These findings indicate that exposure to either ethanol or heat shock can both stabilize I278T protein and increase its specific activity.

To understand the mechanism by which ethanol and heat shock restored I278T function, we examined the steady-state levels of three major Hsps in yeast, Hsp26, Hsp70, and Hsp104. In strains expressing WT CBS, we observed increased Hsp70 levels with regards to ethanol exposure, but no increase in either Hsp26 or Hsp104 (Fig. 1D). Interestingly, basal levels of Hsp26 were much lower in I278T yeast but strongly induced by ethanol (Fig. 1D, right panel).

Elevated Hsp70 Is Associated with Increased I278T Activity—Because ethanol induced Hsp70 and increased both steady-state levels and specific activity of I278T, we hypothesized that elevated Hsp70 might aid in the correct folding of I278T protein. Because Hsp70 in S. cerevisiae is encoded by a gene family with at least 14 members (22), we had to first determine which gene or genes were responsible for the increased Hsp70 cross-reacting material observed by immunoblot. We examined the level of Hsp70 protein present in yeast strains grown in ethanol containing deletions of each of the annotated Hsp70 family members. We found significant reductions of Hsp70 in cells containing deletions in three genes, SSA2, SSC1, and SSQ1 (Fig. 2A). We focused on SSA2, because it was the only one of the three genes thought to be present in the cytosol. (The SSQ1 and SSC1 are thought to encode mitochondrial proteins (22).) Therefore, to determine whether cytosolic Hsp70 is playing a crucial role in proper I278T folding, we deleted SSA2 in a strain expressing I278T and measured CBS function by examining growth on cysteine-free media in the presence and absence of 4% ethanol (Fig. 2B). I278T cells deleted for SSA2 (ssa2Δ) can no longer grow in the presence of ethanol, implying that SSA2 is required for ethanol rescue of I278T.

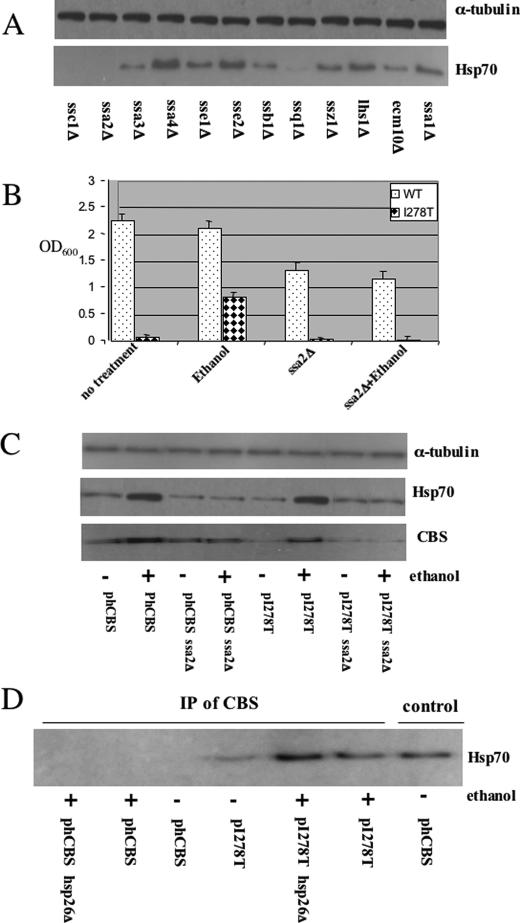

FIGURE 2.

Hsp70 interacts with I278T CBS. A, yeast strains deleted for the indicated genes were grown in the presence of 4% ethanol, and total lysates were examined for Hsp70 and α-tubulin by immunoblot. B, yeast strain LS3 (α leu2 ura3 ade2 trp1 cys4::LEU2 SSA2::KanMX) was transformed with pI278T or phCBS, and saturated cultures were diluted 1:1000 in SC–Trp–Cys+G418 media and grown with aeration at 30 °C for 24 h in the absence and presence of ethanol. Growth was measured by A600 (OD600). C, WY35 or LS3 cells transformed with either phCBS or pI278T were grown in SC–Trp+G418+Glu media in the presence or absence of 4% ethanol as indicated. Cells were harvested, and CBS, Hsp70, and α-tubulin were assessed by immunoblot. D, yeast strain WY35 phCBS, WY35 pI278T, LS1 pI278T, and LS1 phCBS were grown in SC–Trp+Cys media with or without ethanol. Two hours before harvest, 50 μm MG132 was added, and cell lysates were prepared. Immunoprecipitation (IP) was performed with anti-Hsp26 antibody, and CBS present in the immune complexes was analyzed by immunoblot. Lane labeled control shows extract without immunoprecipitation.

We next examined how ethanol and ssa2Δ affected steady-state levels of CBS. In the absence of ethanol we find that steady-state levels of I278T are significantly reduced compared with WT CBS (Fig. 2C and Fig. 3A). Addition of ethanol increases I278T steady-state levels but only when SSA2 is present. This experiment indicates that elevated Hsp70 may help stabilize I278T protein.

We next determined if Hsp70 could bind directly to wild-type and I278T CBS. Immunoprecipitation experiments with α-CBS antibodies show that Hsp70 forms a complex with I278T but not wild-type CBS protein (Fig. 2D). The amount of the complex appears to increase upon ethanol induction or deletion of Hsp26. These findings show that Hsp70 binds specifically to I278T and that Hsp70 is required for ethanol rescue of I278T.

Hsp104 Is Not Involved in Reactivation of I278T CBS Activity—Because previous studies have suggested that Hsp104 acts coordinately with Hsp70 for protein refolding (4, 5), we investigated if Hsp104 plays a role in ethanol rescue of I278T. We found that deletion of Hsp104 had no effect on ethanol rescue of I278T as measured by growth, steady-state level of protein, or activity (Fig. 3, A and B). These findings suggest that Hsp104 does not play a significant role in reactivation of the inactive mutant I278T.

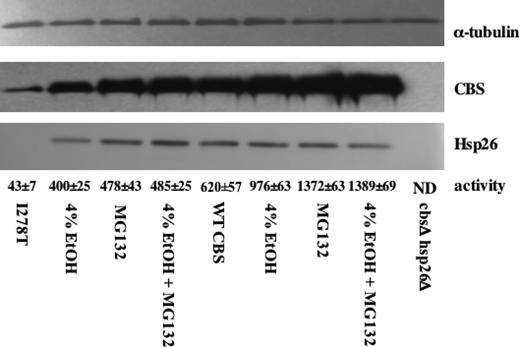

I278T Expression Causes Reduced Steady-state Levels of Hsp26—Based on the Western blot shown in Fig. 1D, we were interested in why yeast expressing I278T had greatly reduced levels of Hsp26 compared with yeast that express WT CBS. We hypothesized that the low steady-state levels of I278T and Hsp26 in I278T-expressing yeast might be due to increased proteosomal degradation of I278T and Hsp26 proteins. To test this, we examined the steady-state levels of CBS and Hsp26 in WT and I278T yeast supplemented with either ethanol or the proteosome inhibitor MG132 (Fig. 4). I278T yeast had significantly lower steady-state levels of both CBS and Hsp26 protein compared to WT yeast, and addition of either 4% ethanol or the proteosome inhibitor MG132 caused a significant increase in both I278T and Hsp26. The steady-state levels of I278T CBS were slightly higher in the MG132-treated cells compared with the 4% ethanol-treated cells, as was enzyme activity. Treatment with both ethanol and MG132 was no more effective than MG132 by itself in stabilizing I278T protein. With regard to WT CBS, 4% ethanol resulted in an ∼50% increase in both steady-state and enzyme activity, whereas MG132 treatment resulted in a 2-fold increase in activity and steady-state protein. Taken together these observations show the following. 1) Expression of I278T results in decreased Hsp26 levels. 2) Low steady-state levels of both I278T and Hsp26 can be reversed by addition of the proteosome inhibitor MG132. 3) 4% ethanol supplementation stabilizes I278T and Hsp26 proteins and increases the specific activity of I278T expressed in S. cerevisiae.

FIGURE 4.

Ethanol and MG132 rescue of I278T. WY35 phCBS and WY 35 pI278T were grown in SC–Trp+Cys media in the absence and presence of 4% ethanol. Where indicated, 50 μm MG132 was added 3 h before cells were harvested. Total cell lysates were then examined for CBS, Hsp26, and α-tubulin by immunoblot. CBS enzyme activity was measured for each extract in triplicate with the mean ± S.D. for each sample indicated.

Hsp26Δ Restores Function to I278T CBS—To explain both the low steady-state levels of I278T and how I278T expression resulted in decreased steady-state Hsp26, we hypothesized that Hsp26 binds to I278T, and the Hsp26-I278T complex is then targeted to the proteosome for degradation. A prediction of this hypothesis is that, in the absence of Hsp26, steady-state levels of I278T should increase resulting in increased CBS activity. As predicted, I278T yeast deleted for HSP26 (hsp26Δ) had increased steady-state CBS protein and increased CBS activity (Fig. 5A). I278T protein levels increased by 4-fold, whereas I278T activity increased 9-fold, to almost 60% that observed in the hCBS-expressing strain. Loss of Hsp26 had no significant effect on WT CBS. Hsp26Δ also rescued the cysteine auxotrophy of I278T (Fig. 5B) and caused a 776% increase in CBS tetramer formation on native gels (Fig. 5C). In contrast, overexpression of Hsp26 selectively reduced levels of I278T but did not affect WT CBS levels (Fig. 5D).

FIGURE 5.

Hsp26 interacts with I278T CBS. A, yeast strain LS1 (α leu2 ura3 ade2 trp1 cys4::LEU2 hsp26::KanMX) was grown in SC–Trp+Cys, and total lysates were examined for CBS and Hsp26 protein by immunoblot. Extracts were also examined for CBS activity in triplicate. CR indicates cross-reacting band that acts as an internal control. B, yeast strain LS1 was transformed with either phCBS or pI278T. Yeast were grown in SC–Trp–Cys in the absence and presence of 4% ethanol, and growth was measured after 24 h using A600 (OD). C, indicated strains were grown in SC+Cys media, and total soluble extracts were prepared. Extracts were then subjected to native gel electrophoresis followed by immunoblot with native CBS antiserum. D, yeast strains WY35 phCBS and WY35 pI278T were transformed with a plasmid overexpressing Hsp26 (pHsp26). Strains were grown in SC–Trp–Ura+Cys media, and total lysates were examined for CBS, Hsp26, and α-tubulin by immunoblot. E, yeast strain WY35 phCBS, WY35 pI278T, LS1 pI278T, and WY35 were grown in SC–Trp+Cys media with or without ethanol. At this time, 50 μm MG132 (to prevent I278T degradation) was added, and cells were incubated an additional 2 h before lysates were prepared. Immunoprecipitation (IP) was performed with anti-Hsp26 antibody, and CBS present in the immune complexes was analyzed by immunoblot. Lane labeled control shows extract without immunoprecipitation.

A second prediction of our hypothesis is that Hsp26 should physically interact with I278T CBS but not wild-type CBS. As shown in Fig. 5E, antibodies to Hsp26 immunoprecipitated I278T present in untreated cells but not in cells treated with ethanol or expressing WT CBS. These findings show the following. 1) Hsp26 binds to I278T CBS and is required for degradation of both proteins. 2) I278T enzyme is highly active in the absence of Hsp26.

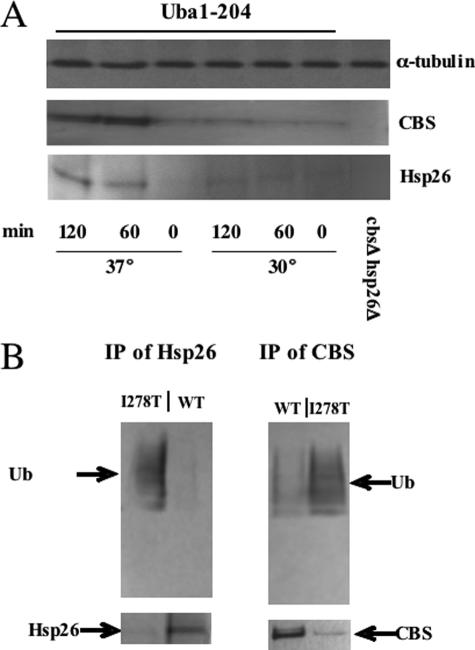

Degradation of Hsp26-I278T Complex Is Ubiquitin-dependent—To test whether degradation of I278T and Hsp26 is ubiquitin-dependent, we first expressed I278T in yeast containing a temperature-sensitive allele of the ubiquitin-activating enzyme (uba1–204) (15). When shifted to the nonpermissive temperature, cells carrying this allele exhibit a rapid depletion of cellular ubiquitin conjugates and stabilization of several different substrates. Using this strain, we found that shifting to the nonpermissive temperature resulted in a large increase in the steady-state levels of both I278T and Hsp26 (Fig. 6A). These findings suggest that that degradation of the Hsp26-I278T complex is ubiquitin-dependent.

FIGURE 6.

Ubiquitin-dependent degradation of I278T and Hsp26. A, yeast strain LS4pI278TΔ was grown in SC–His–Leu–Trp+Glu at 30 °C to an A600 of 0.7 and then either shifted to 37 °C or maintained at the current temperature as indicated. At the indicated times, total lysates were prepared and analyzed for CBS and Hsp26 by immunoblot. B, yeast strain LS3 transformed with either pI278T or phCBS was grown in SC–Trp+G418 to an A600 of 0.7 and then treated with 50 μm MG132 for 3 h. Extracts were then subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with either Hsp26 and CBS antibodies. Immune complexes were analyzed for ubiquitin (Ub), CBS, and Hsp26 by immunoblot.

More direct evidence for the ubiquitination of Hsp26 and I278T was obtained using immunoprecipitation. For these experiments, we prepared extracts from an ssa2Δ strain treated with the proteosome inhibitor MG132 expressing either WT or I278T CBS. The ssa2Δ mutation was used to prevent I278T from folding into a native conformation, whereas the MG132 was used to prevent degradation of the ubiquitinated substrate. As shown in Fig. 6B, immunoprecipitation with either Hsp26 or CBS-specific antibodies pulled down significant amounts of ubiquitinated Hsp26 or CBS protein only in the strain that expresses I278T and not WT CBS (top panel). Probing the immunoprecipitated material with either CBS or Hsp26 antibodies reveals that almost all of the Hsp26 or I278T present is ubiquitinated in the I278T-expressing strain but not in the WT-expressing strain. This experiment demonstrates that I278T is a substrate for ubiquitination and that expression of I278T induces ubiquitination of Hsp26.

DISCUSSION

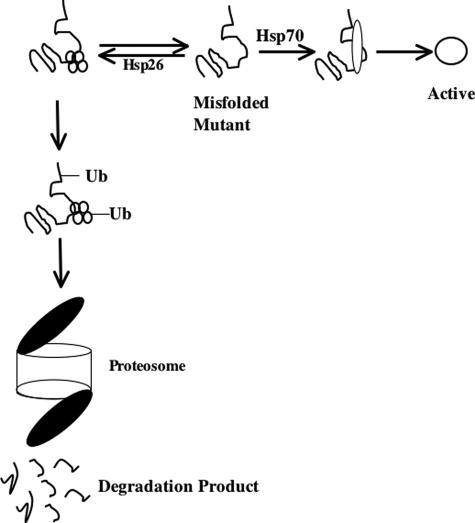

The data presented here show that substantial enzymatic function could be restored to human I278T CBS expressed in S. cerevisiae by either reduction of Hsp26 or increase in Hsp70 levels. To explain our data, we propose a model (Fig. 7) in which there is an equilibrium between Hsp26 and Hsp70 binding to misfolded mutant proteins. In this model, Hsp26 acts as a quality-control chaperone resulting in the formation of an Hsp26-mutant protein complex that is then targeted to the proteosome for degradation, whereas Hsp70 acts positively as a refolding chaperone resulting in the production of functional active protein.

FIGURE 7.

Equilibrium model of Hsp26 acting as quality control chaperone. Missense mutant proteins are acted on by two competing systems. If bound by Hsp26, missense mutant proteins are ubiquitinated and directed to the proteosome for degradation. If bound by Hsp70, mutant proteins are refolded into an active conformation. Ub, ubiquitin.

This model can explain all of our experimental data. In the absence of ethanol, the Hsp26 pathway predominates because there are low basal levels of Hsp70 relative to Hsp26. This then results in low steady-state levels of I278T. In the presence of ethanol, Hsp70 levels are greatly increased resulting in the refolding of I278T to an enzymatically active, stable form. We speculate that addition of the proteosome blocker, MG132, results in increased enzyme activity by increasing the half-life of the I278T protein, resulting in an increased probability of interaction with Hsp70. The simplest explanation for the observation that either ethanol treatment or MG132 could modestly increase steady-state levels of WT CBS is that about half of the time WT CBS fails to fold properly and is then subject to degradation. This is also consistent with the modest amount of ubiquitination observed for WT CBS in Fig. 6.

Previous studies have shown that Hsp26 and other small heat shock proteins bind denatured proteins and prevent protein aggregation (4, 5). The Hsp26-denatured protein complexes are then acted upon by Hsp70 and Hsp104 to allow refolding. In contrast, the experiments described here indicate that Hsp26 has the opposite function, binding to misfolded mutant protein and directing it to the proteosome. Our data also show that Hsp104 does not play an important role in this process. However, there are some key difference between these two sets of experiments. In both earlier studies, marker proteins were subjected to heat stress, whereas the experiments presented here involved the use of missense proteins grown under normal temperature conditions. In addition, the experiments described here utilize a human protein and not an endogenous yeast protein. Interestingly, Ahner et al. (23) demonstrated that Hsp26 expression was induced by expression of the human cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator in S. cerevisiae and that deletion of Hsp26 increased the half-life of the protein. Because both our system and the system by Ahner et al. (23) involve the expression of foreign proteins, we cannot be certain that Hsp26 would function the same way with regard to endogenous misfolded yeast proteins.

Our data also suggest a link between sHsp and the ubiquitin/proteosome system. We found that both I278T and Hsp26 steady-state protein levels increased in either the absence of ubiquitin-activating enzyme protein or the presence of a proteosome inhibitor. In addition, we demonstrate directly that Hsp26 and I278T are ubiquitinated. We hypothesize that Hsp26-I278T complex is a target for a ubiquitin ligase, which then directs the entire complex to the proteosome for degradation. A link between molecular chaperones and ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis has been described previously. CHIP, carboxyl terminus of Hsc70-interacting protein, is a ubiquitin-protein isopeptide ligase that is known to interact with both mammalian Hsp90 and Hsp70 and is responsible for the degradation of several proteins, including the glucocorticoid receptor, ErbB2, cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator, and luciferase (24). We hypothesize that there may also be a ubiquitin-protein isopeptide ligase that interacts with yeast Hsp26 and directs ubiquitination of the complex. One possible candidate is Cul8, a ubiquitin-protein isopeptide ligase involved in anaphase progression that was found to interact with Hsp26 in a large scale proteomics screen using tandem affinity purification (25, 26). One interesting difference between the CHIP system and the one described here is that in CHIP-mediated degradation the levels of the accompanying Hsp protein do not change, whereas in the system described here both the misfolded protein and the accompanying Hsp26s are degraded.

Our findings also suggest new potential strategies to treat genetic diseases. The fact that we were able to restore significant functional activity back to the I278T protein suggests that some disease-causing missense mutations can be refolded successfully by modifying the molecular chaperone environment. In humans there are 10 members of sHsp family designated HspB1–B10 and at least 9 members of the Hsp70 family (27). Interestingly, overexpression of the mammalian Hsp26 orthologue α-crystalline (HspB4) caused enhanced degradation of DF508-cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator in human embryonic kidney cells (23). If our finding that deletion of Hsp26 results in increased mutant protein expression and activity in mammalian cells, it may be possible to develop agents that alter molecular chaperone expression in vivo, resulting in increased mutant protein function. This approach might be especially attractive for treating individuals with inherited genetic disorders in metabolism because often a small increase in residual enzymatic activity can have a profound effect in the clinical severity of the disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Raymond Deshaies for supplying us with RJD3269 and RJD3270 and Johannes Buchner for the Hsp26 antiserum. We thank the DNA sequencing facility of Fox Chase Cancer Center for their assistance. We also thank Dr. Erica Golemis and Dr. Cindy Keleher for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants HL57299 and CA06927 (core grant). This work was also supported by an appropriation from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement”in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: sHsp, small heat shock protein; CBS, cystathionine β-synthase; WT, wild type.

References

- 1.Smith, D. F., Whitesell, L., and Katsanis, E. (1998) Pharmacol. Rev. 50 493–514 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartl, F. U., and Hayer-Hartl, M. (2002) Science 295 1852–1858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haslbeck, M. (2002) Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 59 1649–1657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cashikar, A. G., Duennwald, M., and Lindquist, S. L. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 23869–23875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haslbeck, M., Miess, A., Stromer, T., Walter, S., and Buchner, J. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 23861–23868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jhee, K. H., and Kruger, W. D. (2005) Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 7 813–822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kruger, W. D., Wang, L., Jhee, K. H., Singh, R. H., and Elsas, L. J., II (2003) Hum. Mutat. 22 434–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kraus, J. P., Janosik, M., Kozich, V., Mandell, R., Shih, V., Sperandeo, M. P., Sebastio, G., de Franchis, R., Andria, G., Kluijtmans, L. A., Blom, H., Boers, G. H., Gordon, R. B., Kamoun, P., Tsai, M. Y., Kruger, W. D., Koch, H. G., Ohura, T., and Gaustadnes, M. (1999) Hum. Mutat. 13 362–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meier, M., Janosik, M., Kery, V., Kraus, J. P., and Burkhard, P. (2001) EMBO J. 20 3910–3916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kruger, W. D., and Cox, D. R. (1995) Hum. Mol. Genet. 4 1155–1161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim, C. E., Gallagher, P. M., Guttormsen, A. B., Refsum, H., Ueland, P. M., Ose, L., Folling, I., Whitehead, A. S., Tsai, M. Y., and Kruger, W. D. (1997) Hum. Mol. Genet. 6 2213–2221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shan, X., Dunbrack, R. L., Jr., Christopher, S. A., and Kruger, W. D. (2001) Hum. Mol. Genet. 10 635–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shan, X., and Kruger, W. D. (1998) Nat. Genet. 19 91–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh, L. R., Chen, X., Kozich, V., and Kruger, W. D. (2007) Mol. Genet. Metab. 91 335–342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghaboosi, N., and Deshaies, R. J. (2007) Mol. Biol. Cell 18 1953–1963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shoemaker, D. D., Lashkari, D. A., Morris, D., Mittmann, M., and Davis, R. W. (1996) Nat. Genet. 14 450–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sherman, F. (2002) Methods Enzymol. 350 3–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haslbeck, M., Walke, S., Stromer, T., Ehrnsperger, M., White, H. E., Chen, S., Saibil, H. R., and Buchner, J. (1999) EMBO J. 18 6744–6751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Slegtenhorst, M., Carr, E., Stoyanova, R., Kruger, W. D., and Henske, E. P. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 12706–12713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen, X., Wang, L., Fazlieva, R., and Kruger, W. D. (2006) Hum. Mutat. 27 474–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alexandre, H., Ansanay-Galeote, V., Dequin, S., and Blondin, B. (2001) FEBS Lett. 498 98–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dutkiewicz, R., Schilke, B., Knieszner, H., Walter, W., Craig, E. A., and Marszalek, J. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 29719–29727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahner, A., Nakatsukasa, K., Zhang, H., Frizzell, R. A., and Brodsky, J. L. (2007) Mol. Biol. Cell 18 806–814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McDonough, H., and Patterson, C. (2003) Cell Stress Chaperones 8 303–308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krogan, N. J., Cagney, G., Yu, H., Zhong, G., Guo, X., Ignatchenko, A., Li, J., Pu, S., Datta, N., Tikuisis, A. P., Punna, T., Peregrin-Alvarez, J. M., Shales, M., Zhang, X., Davey, M., Robinson, M. D., Paccanaro, A., Bray, J. E., Sheung, A., Beattie, B., Richards, D. P., Canadien, V., Lalev, A., Mena, F., Wong, P., Starostine, A., Canete, M. M., Vlasblom, J., Wu, S., Orsi, C., Collins, S. R., Chandran, S., Haw, R., Rilstone, J. J., Gandi, K., Thompson, N. J., Musso, G., St Onge, P., Ghanny, S., Lam, M. H., Butland, G., Altaf-Ul, A. M., Kanaya, S., Shilatifard, A., O'Shea, E., Weissman, J. S., Ingles, C. J., Hughes, T. R., Parkinson, J., Gerstein, M., Wodak, S. J., Emili, A., and Greenblatt, J. F. (2006) Nature 440 637–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Michel, J. J., McCarville, J. F., and Xiong, Y. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 22828–22837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kappe, G., Franck, E., Verschuure, P., Boelens, W. C., Leunissen, J. A., and de Jong, W. W. (2003) Cell Stress Chaperones 8 53–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]