Abstract

Deprivation of estrogen causes breast tumors in women to adapt and develop enhanced sensitivity to this steroid. Accordingly, women relapsing after treatment with oophorectomy, which substantially lowers estradiol for a prolonged period, respond secondarily to aromatase inhibitors with tumor regression. We have utilized in vitro and in vivo model systems to examine the biologic processes whereby Long Term Estradiol Deprivation (LTED) causes cells to adapt and develop hypersensitivity to estradiol. Several mechanisms are associated with this response including up-regulation of ERα and the MAP kinase, PI-3-kinase and mTOR growth factor pathways. ERα is 4–10 fold up-regulated as a result of demethylation of its C promoter, is nuclear receptor then co-opts a classical growth factor pathway using SHC, Grb-2 and Sos. is induces rapid nongenomic effects which are enhanced in LTED cells.

The molecules involved in the nongenomic signaling process have been identified. Estradiol binds to cell membrane-associated ERα which physically associates with the adaptor protein SHC and induces its phosphorylation. In turn, SHC binds Grb-2 and Sos which results in the rapid activation of MAP kinase. These nongenomic effects of estradiol produce biologic effects as evidenced by Elk-1 activation and by morphologic changes in cell membranes. Additional effects include activation of the PI-3-kinase and mTOR pathways through estradiol-induced binding of ERα to the IGF-1 and EGF receptors.

A major question is how ERα locates in the plasma membrane since it does not contain an inherent membrane localization signal. We have provided evidence that the IGF-1 receptor serves as an anchor for ERα in the plasma membrane. Estradiol causes phosphorylation of the adaptor protein, SHC and the IGF-1 receptor itself. SHC, after binding to ERα, serves as the “glue” which tethers ERα to SHC binding sites on the activated IFG-1 receptors. Use of siRNA methodology to knock down SHC allows the conclusion that SHC is needed for ERα to localize in the plasma membrane.

In order to abrogate growth factor induced hypersensitivity, we have utilized a drug, farnesylthiosalicylic acid, which blocks the binding of GTP-Ras to its membrane acceptor protein, galectin 1 and reduces the activation of MAP kinase. We have shown that this drug is a potent inhibitor of mTOR and this provides the major means for inhibition of cell proliferation. The concept of “adaptive hypersensitivity” and the mechanisms responsible for this phenomenon have important clinical implications. The efficacy of aromatase inhibitors in patients relapsing on tamoxifen could be explained by this mechanism and inhibitors of growth factor pathways should reverse the hypersensitivity phenomenon and result in prolongation of the efficacy of hormonal therapy for breast cancer.

Introduction

Cancer cells adapt in response to the pressure exerted upon them by various hormonal treatments. Ultimately, this process of adaptation renders them insensitive to hormonal therapy. In patients, clinical observations suggest that long term deprivation of estradiol causes breast cancer cells to develop enhanced sensitivity to the proliferative effects of estrogen. Premenopausal women with advanced hormone dependent breast cancer experience objective tumor regressions in response to surgical oophorectomy which lowers estradiol levels from mean levels of approximately 200 pg/ml to 10 pg/ml.1 After 12–18 months on average, tumors begin to regrow even though estradiol levels remain at 10 pg/ml. Notably tumors again regress upon secondary therapy with aromatase inhibitors which lower estradiol levels to 1–2 pg/ml. These observations suggest that tumors develop hypersensitivity to estradiol as demonstrated by the fact that untreated tumors require 200 pg/ml of estradiol to grow whereas tumors regrowing after oophorectomy require only 10 pg/ml. We have shown in prior studies that up-regulation of growth factor pathways contributes to the phenomenon of hypersensitivity.2–10 Ultimately these tumors adapt further and grow exclusively in response to growth factor pathways and do not require estrogens for growth.

In order to provide direct proof that hypersensitivity does develop and to study the mechanisms involved, we have utilized cell culture and xenograft models of breast cancer as experimental tools.5,8,9,11–13

Phenomenon of Hypersensitivity: Mechanisms and Pathways

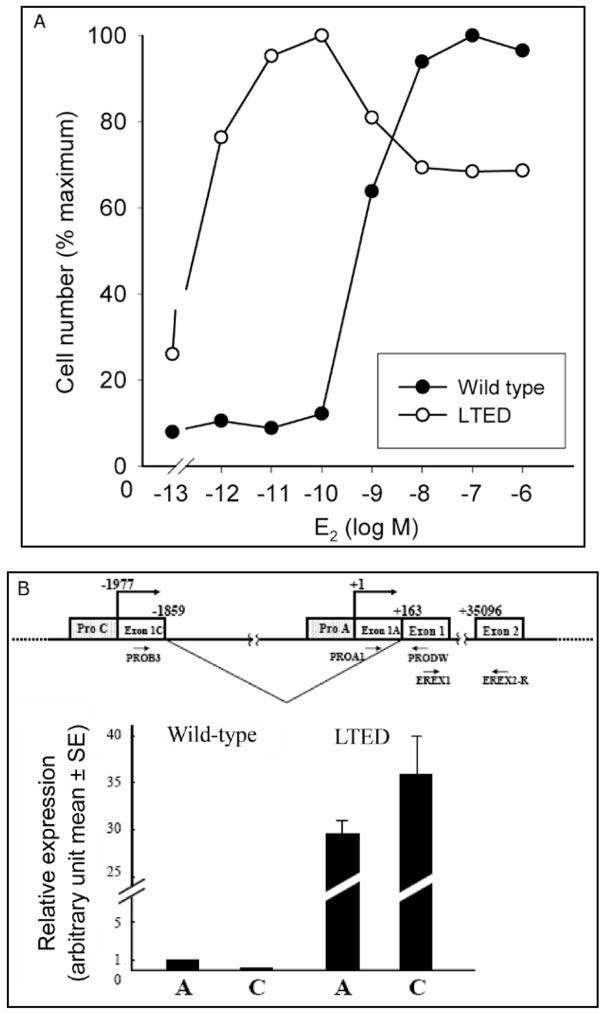

To induce hypersensitivity, wild type MCF-7 cells require culturing over a 6–24 month period in estrogen-free media to mimic the effects of ablative endocrine therapy such as induced by surgical oophorectomy or aromatase inhibitors.11,12 is process involves Long Term Estradiol Deprivation and the adapted cells are called by the acronym, LTED cells. As evidence of hypersensitivity, a three log lower concentration of estradiol can stimulate proliferation of LTED cells compared to wild type MCF-7 cells (Fig. 1A).7 We reasoned that the development of hypersensitivity could involve modulation of the genomic effects of estradiol acting on transcription, nongenomic actions involving plasma membrane related receptors, cross talk between growth factor and steroid hormone stimulated pathways, or interactions among these various effects.5,7–9,11–13

Figure 1.

A) E2-induced cell proliferation. Wild type MCF-7 and LTED cells were plated in 6 well plates at a density of 60,000 cells/well. After 2 days the cells were refed with phenol-red and serum free IMEM (improved modified Eagles medium) and cultured in this medium for another 2 days before treatment with various concentrations of E2 in the presence of ICI 182,780 (fulvestrant) at a 1 nmol concentration to abrogate the effects of any residual estradiol in the medium. Cell number was counted 5 days after treatment.7,9 From: Yue W et al. Endocrinology 2002; 143(9):3221-9;9 with permission of The Endocrine Society. B) Schematic representation of a part of ER alpha gene organization is shown. The transcription start site of Promoter A is defined as +1. Relative expression of ER alpha mRNA from promoters A and C in wild type and LTED cells is shown. Expression levels of ER alpha mRNA from promoters A and C were quantified by RT-PCR. C) COBRA assay for gene promoter C of ER α in wild type and LTED cells: an image of the polyacrilamide gel showing the methylated (M) and unmethylated (UM) products. B,C) From: Sogon T et al. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2007; 105(1–5):106–14;13a with permission of Elsevier.

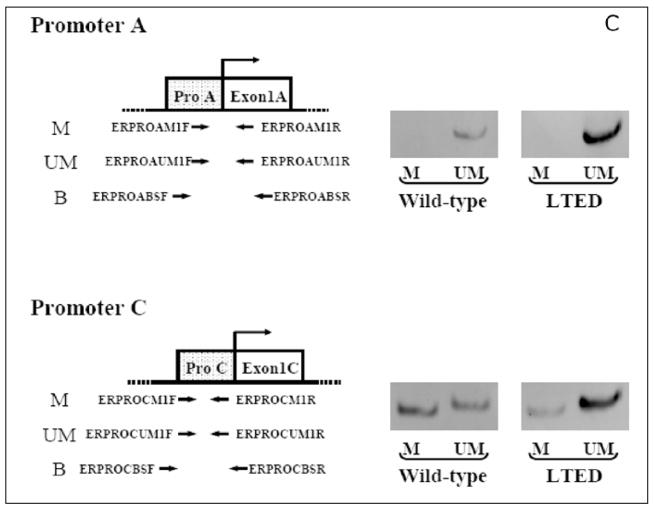

We initially postulated that enhanced receptor mediated transcription of genes related to cell proliferation might be involved. Indeed, the levels of ERα increased 4–10 fold during long term estradiol deprivation.11 The up-regulation of ER alpha results from demethylation of promoter A and C of the estrogen receptor (Fig. 1B and 1C). The transcripts stimulated by this promoter increase by 149 fold and the DNA of this segment exhibits a marked increase in demethylation. 13AWe initially reasoned that the up-regulation of ERα would directly result in hypersensitivity to estradiol (E2). Accordingly, to directly examine whether enhanced sensitivity to E2 in LTED cells occurred at the level of ER mediated transcription, we quantitated the effects of estradiol on transcription in LTED and in wild type MCF-7 cells. As transcriptional readouts, we measured the effect of E2 on progesterone receptor (PgR) and pS2 protein concentrations and on ERE-CAT reporter activity (Fig. 2A–F).9,13 We observed no shift to the left in estradiol dose response curves (the end point utilized to detect hypersensitivity) for any of these responses (i.e., PgR, pS2, CAT activity) when comparing LTED with wild type MCF-7 cells. On the other hand, basal levels (i.e., no estrogen added) of transcription of three ER/ERE related reporter genes were greater in LTED than in wild type MCF-7 cells (Fig. 2D–F).13

Figure 2.

A–C) Wild–type MCF-7 and LTED cells, deprived of E2, were treated with different concentrations of E2. Cytosols were measured for PgR (A), pS2 protein (B) and ERE-TK-CAT activity (C) 48 h after E2 treatment. A–C) From: Yue W et al. Endocrinology 2002; 143(9):3221-9;9 with permission of The Endocrine Society. D–F) ER trans-activation function in wild-type MCF-7 and LTED cells under basal conditions. Wild type and LTED cells were deprived of estrogen and transfected with ERE-TK-CAT (D), pERE-2-TK-CAT E) or pERE-E1b-CAT (F) reporter plasmids in conjunction with pCMV-beta Gal plasmid as internal control. Two days later, cell cytosols were collected and assayed for CAT activities using the same amount of beta-galactosidase units.9,11,13 D–F) From: Jeng MH et al. Endocrinology 1998; 139(10):4164–74;13 with permission of The Endocrine Society.

To interpret these data, we used the classic definition for hypersensitivity, namely a significant shift to the left in the dose causing 50% of maximal stimulation. Accordingly, these data suggest that hypersensitivity of LTED cells to the proliferative effects of estradiol does not occur primarily at the level of ER-mediated gene transcription (Fig. 2A–C) but may be influenced by the higher rates of maximal transcription (Fig. 2D–F).

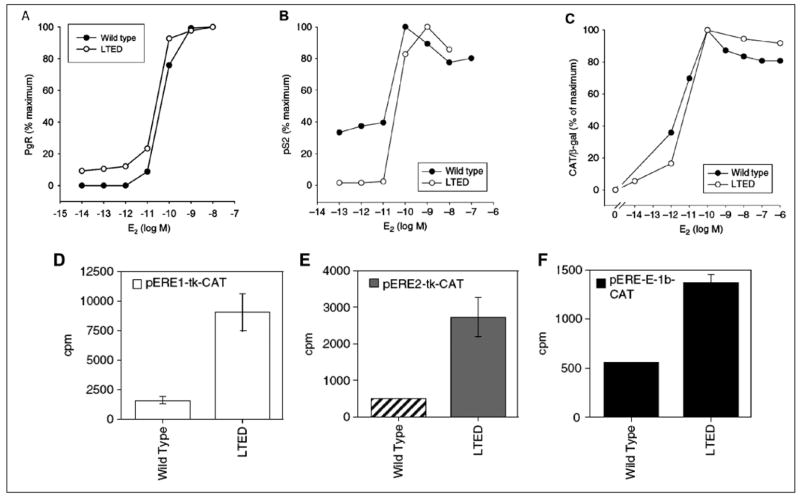

We next considered that adaptation might involve dynamic interactions between pathways utilizing steroid hormones and those involving MAP kinase and PI-3-kinase for growth factor signaling (Fig. 3A).5,7–9,11–16 Our initial approach demonstrated that basal levels of MAP kinase were elevated in LTED cells in vitro (Fig. 2B, top panel) and in xenografts (data not shown) and were inhibited by the pure antiestrogen, fulvestrant.8,11

Figure 3.

A) Diagrammatic representation of the MAP kinase and PI-3-kinase signaling pathways activated when growth factors bind to their trans-membrane receptors. After auto-phosphorylation of the receptor, a series of events occurs which results in the activation of Ras. Downstream from Ras is the activation of the MAP kinase pathway with its components Raf and Mek and the activation of the PI-3-kinase pathway with its downstream components Akt, mTOR and p70S6K. At the same time, estradiol binds to the estrogen receptor and initiates transcription in the nucleus. B, top) Comparison of total and activated MAP kinase, detected with a phosphospecific antibody directed against activated MAP kinase and an antibody directed against total MAP kinase, in WT (wild-type MCF-7) and LTED cells. The right portion of the panel is a quantitation of the ratio of activated to total MAP kinase in WT and LTED cells.16 B, second, third and fourth panels) Use of phosphospecific antibodies to quantitate the levels of activated Akt (second panel), p70S6 kinase (third panel) and 4E-BP1 (fourth panel) in wild type MCF-7 and LTEDS cells.16 C) Treatment of LTED cells with an inhibitor of MAP kinase (U-0126) and PI-3- kinase (LY 292004) to demonstrate a shift to the right of LTED cells to a normal level of sensitivity to estradiol.7,9 From: Yue W et al. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2003; 86(3–5):265–74;8 ©2003 with permission from Elsevier.

We further demonstrated that activated MAP kinase is implicated in the enhanced growth of LTED cells since inhibitors of MAP kinase such as PD98059 or U-0126 block the incorporation of tritiated thymidine into DNA.7 To demonstrate proof of the principle of MAP kinase participation, we stimulated activation of MAP kinase in wild type MCF-7 cells by administering TGFα (data not shown). Administration of TGFα caused a two log shift to the left in the ability of estradiol to stimulate the growth of wild type MCF-7 cells. To demonstrate that this effect was related specifically to MAP kinase and not to a nonMAP kinase mediated effect of TGF alpha, we co-administered PD 98059. Under these circumstances, the two log left shift in estradiol dose response, returned back to the baseline dose response curve.7 As further evidence of the role of MAP kinase, we administered U-0126 to LTED cells and examined its effect on level of sensitivity to estradiol. is agent partially shifted dose response curves to the right by approximately one-half log (data not shown).

While an important component, MAP kinase did not appear to be solely responsible for hypersensitivity to estradiol. Blockade of this enzyme did not completely abrogate hypersensitivity. Accordingly, we examined the PI-3-kinase pathway to determine if it was up-regulated in LTED cells as well (Fig. 3B) and examined several signaling molecules downstream from this regulatory kinase.16 We determined that LTED cells exhibit an enhanced activation of AKT (Fig. 3B, second panel), P70 S6 kinase (Fig. 3B, third panel) and PHAS-1/4E BP-1 (Fig. 3B, fourth panel; see also below).16 Dual inhibition of PI-3-kinase with Ly 294002 (specific PI-3-kinase inhibitor) and MAP kinase with U-0126 shifted the level of sensitivity to estradiol more dramatically: more than two logs to the right (Fig. 3C).7

One possible mechanism to explain the activation of MAP kinase would be through nongenomic effects of estrogen acting via ERα located in or near the cell membrane.17–19 We postulated that membrane associated ERα might utilize a classical growth factor pathway to transduce its effects in LTED cells. The adaptor protein SHC represents a key modulator of tyrosine kinase activated peptide hormone receptors.14–15,20 Upon receptor activation and auto-phosphorylation, SHC binds rapidly to specific phosphotyrosine residues of receptors through its PTB or SH2 domain and becomes phosphorylated itself on tyrosine residues of the CH domain.14,15 The phosphorylated tyrosine residues on the CH domain provide the docking sites for the binding of the SH2 domain of Grb2 and hence recruit SOS, a guanine nucleotide exchange protein. Formation of this adapter complex allows Ras activation via SOS, leading to the activation of the MAPK pathway.20

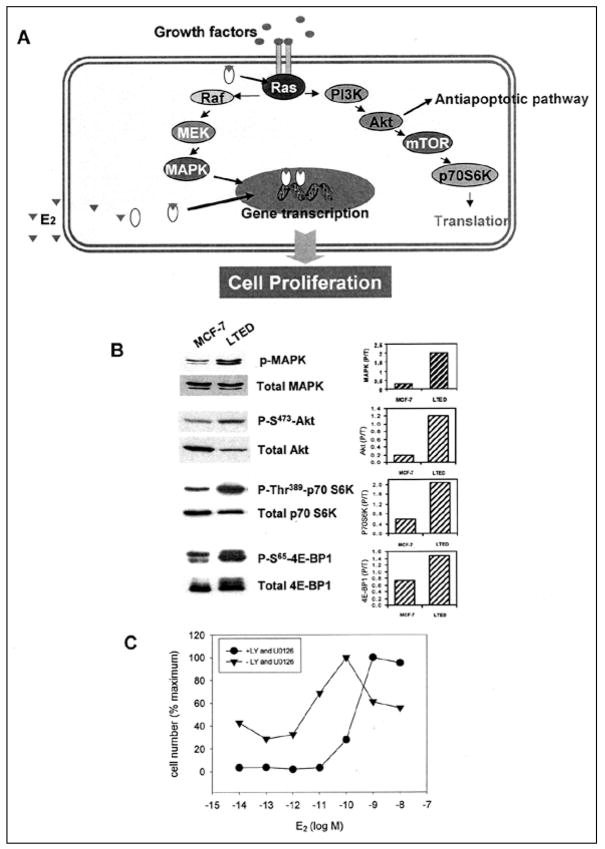

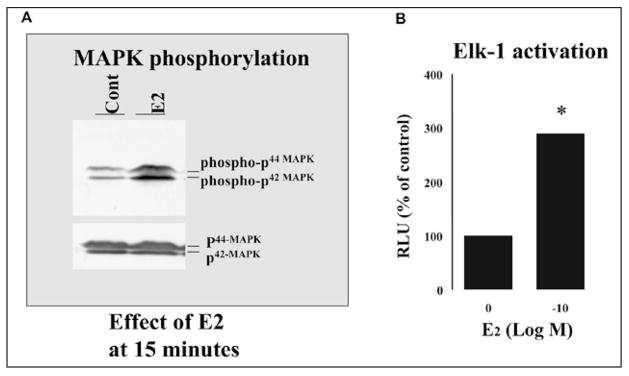

We postulated that estrogen deprivation might trigger activation of a nongenomic, estrogen-regulated, MAP kinase pathway which utilizes SHC.14–15,20–22 We employed MAP kinase activation as an endpoint with which to demonstrate rapid nongenomic effects of estradiol (Fig. 4A). The addition of E2 stimulated MAP kinase phosphorylation in LTED cells within minutes. The increased MAP kinase phosphorylation by E2 was time and dose-dependent, being greatly stimulated at 15 min and remaining elevated for at least 30 min. Maximal stimulation of MAP kinase phosphorylation was at 10−10 M of E2.

Figure 4.

A) Effect of 0.1 nM estradiol on levels of activated and total MAP kinase measured 15 min after addition of steroid. Shown on the top segment is activated MAP kinase as assessed by an antibody specific for activated MAP kinase and on the bottom segment, total MAP kinase. B) Effect of 0.1 nM estradiol on the activation of ELK-1.

We then examined the role of peptides known to be involved in growth factor signaling pathways that activate MAP kinase. SHC proteins are known to couple tyrosine kinase receptors to the MAPK pathway and activation of SHC involves the phosphorylation of SHC itself.20–22 To investigate if the SHC pathway was involved in the rapid action of estradiol in LTED cells, we immunoprecipitated tyrosine phosphorylated proteins and tested for the presence of SHC under E2 treatment. E2 rapidly stimulated SHC tyrosine phosphorylation in a dose and time dependent fashion with a peak at 3 minutes.20 The pure estrogen receptor antagonist, fulvestrant, blocked E2-induced SHC and MAPK phosphorylation at 3 min and 15 min respectively. To demonstrate that the classical ER alpha mediated this response, we transfected a siRNA against ER alpha and showed down-regulation of this receptor and also abrogated the effect of estradiol to rapidly enhance MAP kinase activation. The time frame suggests that SHC is an upstream component in E2-induced MAPK activation.

We reasoned that the adapter protein SHC may directly or indirectly associate with ERα in LTED cells and thereby mediate E2-induced activation of MAP kinase. We considered this likely in light of recent evidence regarding ERα membrane localization.23–25 To test this hypothesis, we immunoprecipitated SHC from nonstimulated and E2-stimulated LTED cells and then probed immunoblots with anti-ERα antibodies. Our data showed that the ERα/SHC complex pre-existed before E2 treatment and E2 time-dependently increased this association.20 In parallel with SHC phosphorylation, we observed a maximally induced association between ERα and SHC at 3 min (data not shown). MAP kinase pathway activation by SHC requires SHC association with the adapter protein Grb2 and then further association with SOS. By immunoprecipitation of Grb2 and detection of both SHC and SOS, we demonstrated that the SHC-Grb2-SOS complex constitutively existed at relatively low levels in LTED cells, but was greatly increased by treatment of cells with 10−10 M E2 for 3 min.20

After the demonstration of protein-protein interactions, we wished to provide evidence that these biochemical steps resulted in biologic effects. Accordingly, we evaluated the role of estrogen activated MAP kinase on the function of the transcription factor, Elk-1. When activated, Elk-1 serves as a down stream mediator of cell proliferation. The phosphorylation of Elk1 by MAPK can up-regulate its transcriptional activity through phosphorylation. By cotransfection of LTED cells with both GAL4-Elk and its reporter gene GAL4-luc,26,27 we were able to show that E2 dose-dependently increased Elk-1 activation at 6 hours as shown by luciferase assay (Fig. 4B).20

We also wished to demonstrate biologic effects on cell morphology. To examine E2 effects on reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton, we visualized the distribution of F-actin by phalloidin staining and also redistribution of the ERα localization in LTED and MCF-7 cells (data not shown).20 Untreated MCF-7 cells expressed low actin polymerization and a few focal adhesion points. After E2 stimulation, in contrast, the cytoskeleton underwent remodeling associated with formation of cellular ruffles, lamellipodia and leading edges, alterations of cell shape and loss of mature focal adhesion points. A sub-cellular redistribution of ERα to these dynamic membranes upon E2 stimulation represented another important feature. The ER antagonist ICI 182 780 at 10−9 M blocked E2-induced ruffle formation as well as redistribution of ERα to the membrane with little effect by itself. Therefore, these studies further demonstrated the rapid action of E2 with respect to dynamic membrane alterations in LTED cells.

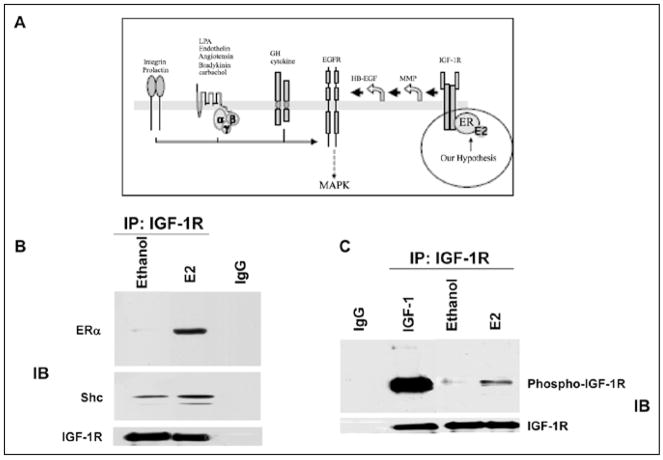

A key unanswered question was how the ER could localize in the plasma membrane when it does not contain membrane localization motifs. We postulated that the IGF-1-receptor and SHC might be involved in this process (Fig. 5A).28 A series of studies by other investigators suggested that ERα and the IGF-1 receptor might interact.28 We tested the model that estradiol caused binding of SHC to ERα but also caused phosphorylation of the IGF-1 receptor. In this way, SHCwould serve as the “glue” which would tether ER alpha to the plasma membrane where it would bind to the SHC acceptor site. To assess this possibility, we immunoprecipitated IGF-1 receptors before and after addition of estradiol. is caused SHC to bind to the IFG-1 receptor (Fig. 5C) and caused the IGF-1 receptor to become phosphorylated (Fig. 5B,C). In order to prove a causal effect for this role of SHC, we utilized an siRNA methodology to knock down SHC and showed that this prevented ERα from binding to the IGF-1 receptor.28 As further evidence, we conducted confocal microscopy experiments to show that knockdown of SHC prevented ERα from localizing in the plasma membrane (data not shown).29

Figure 5.

A, top) Diagrammatic representation of a model in which estradiol binds to ERα which then binds to the adaptor protein, SHC. At the same time estradiol causes phosphorylation of the IGF-1-R, which provides a binding site for SHC. In this model, estradiol signals through the IGF-1-R and activates MAP kinase which then acts through Elk-1 to initiate gene transcription. B) estradiol-induced protein complex formation among ERα, SHC and IGF-1-R. MCF-7 cells were treated with vehicle, 1 ng/ml IGF-1, or E2 at 0.1 nM for the times indicated. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with IGF-1-R antibody. The nonspecific monoclonal antibody (IgG) served as a negative control.28 C) estradiol increases the phosphorylation of the IGF-1-R.

Ellis Levin and colleagues recently showed that ER alpha must be palmitylated before it can localize in the plasma membrane.29A Although speculative, we postulate that ER alpha requires palmitylation to travel to the plasma membrane but activated SHC serves to tether it to the membrane via IGF-1-R. In contrast to our previous concept that SHC serves as the “bus” to carry ER alpha to the membrane, we now postulate that SHC is the “glue” that tethers ER alpha there after binding to the IGF-1-R. Further studies will be necessary to dissect out each component of these interactions and their biologic relevance.

From the data reviewed, we conclude that membrane related ERα plays a role in cell proliferation and in activation of MAP kinase. It appeared likely then that LTED cells might exhibit enhanced functionality of the membrane ERα system. As evidence of this, we examined the ability of estradiol to cause the phosphorylation of SHC in wild type and MCF-7 cells and also to cause association of SHC with the membrane ERα. We demonstrated a marked enhancement of both of these processes in LTED as opposed to wild type cells. Considering all of these data together, it is still not clear at the present time what is responsible for enhancement of the nongenomic ERα mediated process.

If adaptive hypersensitivity results from the up-regulation of growth factor pathways, an inhibitor of MAP kinase and downstream PI-3-kinase pathways could be important in abolishing hypersensitivity and in inhibiting cell proliferation. We had been studying the effects of a MAP kinase inhibitor, farnesylthiosalicylic acid (FTS), which has been shown to block proliferation of LTED cells. is agent interferes with the binding of GTP-Ras to its acceptor site in the plasma membrane, a protein called galectin 1.30 While examining its downstream effects, we have shown that this agent is also a potent inhibitor of phosphoinositol-3-kinase (PI-3-kinase). We postulated that an agent which blocks not only the MAP kinase pathway but also downstream actions of the PI-3-kinase pathway might be ideal to inhibit hypersensitivity. Accordingly, we have intensively studied the effects of FTS on mTOR.

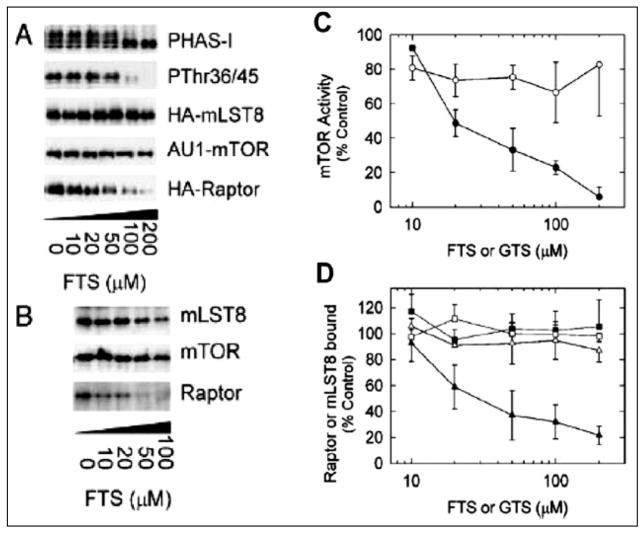

The mammalian target of rapamycin, mTOR, is a Ser/r protein kinase involved in the control of cell growth and proliferation.31 One of the best characterized substrates of mTOR is PHAS-1 (also called 4E-BP1).32,33 PHAS-I/4E-BP1 binds to eIF4E and represses cap-dependent translation by preventing eIF4E from binding to eIF4G.32,33 When phosphorylated by mTOR, PHAS-I/4E-BP1 dissociates from eIF4E, allowing eIF4E to engage eIF4G, thus increasing the formation of the eIF4F complex needed for the proper positioning of the 40S ribosomal subunit and for efficient scanning of the 5′-UTR.31 In cells, mTOR is found in mTORC1, a complex also containing raptor, a newly discovered protein of 150kDa. It has been proposed that raptor functions in TORC1 as a substrate-binding subunit which presents PHAS-I/4E-BP1 to mTOR for phosphorylation.31,32 Our results suggest that FTS inhibits phosphorylation of the mTOR effectors, PHAS-I/4E-BP1 and S6K1, in response to estrogen stimulation of breast cancer cells.2

To investigate the effects of FTS on mTOR function, we utilized 293T cells and monitored changes in the phosphorylation of PHAS-I/4E-BP1.2 Incubating cells with increasing concentrations of FTS decreased the phosphorylation of PHAS-I/4E-BP1, as evidenced by a decrease in the electrophoretic mobility. To determine whether FTS also promoted dephosphorylation of r36 and r45, the preferred sites for phosphorylation by mTOR31, an immunoblot was prepared with P r36/45 antibodies. Increasing FTS markedly decreased the reactivity of PHAS-I/4E-BP1 with the phosphospecific antibodies (Fig. 6A and B).

Figure 6.

Left) FTS promotes raptor dissociation and inhibits mTOR activity in cell extracts. A) 293T cells were transfected with pcDNA3 alone (vector) or with a combination of pcDNA3-AU---mTOR, pcDNA3-3-HA-raptor and pcDNA3-3HA-mLST8. Extracts of cells were incubated with increasing concentration of FTS for 30 min before AU-1-mTOR was immunoprecipitated. Samples of the immune complexes were incubated with (γ32P)-ATP and recombinant (HIS 6) PHAS-1 and then subjected to SDS-PAGE. A phosphor image of a dried gel was obtained to detect 32P-PHAS1 and an immunoblot was prepared with PThr36/45 antibodies. Other samples of the immune complexes were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblots were prepared with antibodies to the HA epitope or to mTOR.2 B) Extracts of nontransfected 293T cells were incubated with increasing concentrations of FTS before mTOR was immunoprecipitated with mTab 1. A control immunoprecipitation was conducted using nonimmune IgG(Nl). Immune complexes were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblots were prepared with antibodies to mLST8, mTOR and raptor.2 Right) Relative effects of increasing concentrations of FTS and GTS on mTOR activity and the association of mTOR and raptor. Samples of extracts from 293T cells overexpressing AU1-mTOR, HA-raptor and HA-mLST8 were incubated for 1 hr with increasing concentrations of FTS (●, ◆, ■) or GTS (○, △, □) before immunopreciptations were conducted with anti-AU 1 antibodies.2 A) mTOR kinase activity (●, ○) was determined by measuring32P incorporation into (HIS6) PHAS-1 in immune complex kinase assays performed with (γ32P)-ATP. B) The relative amounts of HA-raptor (◆,○) and HA-mLST8 (■, △) that co-immunoprecipitated with AU-1-mTOR were determined after immunoblotting with anti-HA antibodies. The results (mean values ± SE for five experiments) are expressed as percentages of the mTOR activity (C) or co-immununoprecipitating proteins (D) from samples incubated without FTS or GTS and have been corrected for the amounts of AU-1–mTOR immunopecipitated.2 From: McMahon LP et al. J Mol Endocrinol 2005; 19(1):175–183;2 with permission of The Endocrine Society.

To investigate further the inhibitory effects of FTS on mTOR signaling, we determined the effect of the drug on the association of mTOR, raptor and mLST8 (Fig. 6A and B). AU1-mTOR and HA-tagged forms of raptor and mLST8 were overexpressed in 293T-cells, which were then incubated with increasing concentrations of FTS before AU1-mTOR was immunoprecipitated with anti-AU1 antibodies. Immunoblots were prepared with anti-HA antibodies to assess the relative amounts of HA-raptor and HA-mLST8 that co-immunoprecipitated with AU1-mTOR. Both HA-tagged proteins were readily detectable in immune complexes from cells incubated in the absence of FTS, indicating that mTOR, raptor and mLST8 form a complex in 293T cells. FTS did not change the amount AU1-mTOR that immunoprecipitated; however, increasing concentrations of FTS produced a progressive decrease in the amount of HA-raptor that co-immunoprecipitated. The half maximal effect on raptor dissociation from mTOR was observed at approximately 30 μM FTS (Fig. 6A, B). Results obtained with over-expressed proteins are not necessarily representative of responses of endogenous proteins. Therefore, experiments were conducted to investigate the effect FTS on the endogenous TORC1 in nontransfected cells. Similar results were found indicating the FTS blocks the association of raptor from mTOR.2

Incubating cells with FTS produced a stable decrease in mTOR activity that persisted even when mTOR was immunoprecipitated. The dose response curves for FTS-mediated inhibition of AU1-mTOR activity (Fig. 6C, D) and dissociation of AU1-mTOR and HA-raptor were very similar, with half maximal effects occurring between 20–30 μM. These results indicate that FTS inhibits mTOR in cells by promoting dissociation of raptor from mTORC1.

These studies provide direct evidence that FTS inhibits mTOR activity. The finding that the inhibition of mTOR activity by increasing concentrations of FTS correlated closely with the dissociation of the mTOR-raptor complex, both in cells and in vitro (Fig. 6), supports the conclusion that FTS acts by promoting dissociation of raptor from mTORC1.

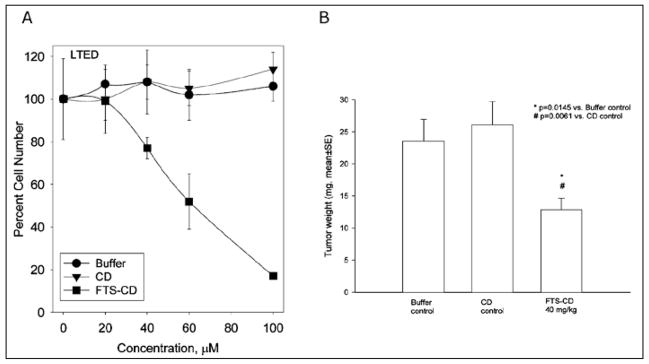

Since FTS blocks both MAP kinase and mTOR, it was reasonable to conclude that it could block cell proliferation. For that reason, we conducted extensive studies to demonstrate that FTS blocks the growth of LTED cells. As shown in Figure 7A, B, FTS blocks the growth on LTED cells both in vitro and in vivo.

Figure 7.

A) In vitro effects of FTS on cell growth. Effects of FTS complexed with cyclodextrin (CD) for solubility were compared with buffer or cyclodextrin (CD) alone on the number of LTED cells expressed as a percent of maximum number. The ordinate shows the concentration of FTS used. B) In vivo effects of FTS on cell growth. LTED cells were implanted into castrate nude mice to form xenografts. Silastic implants delivering estradiol at amounts sufficient to provide plasma levels of estradiol of 5 pg/ml were implanted. One group received buffer alone, the second cyclodextrin alone and the third FTS 40 mg/kg complexed to cyclodextrin. The effects of FTS-CD compared to CD control were statistically significant at p = 0.0061.

Our studies to date have predominantly concentrated on long term estradiol deprivation as a mode of development of resistance to aromatase inhbitors. More recently, we have examined the effect of long term tamoxifen treatment (LTTT) on MCF-7 cells. Interestingly, this maneuver also causes enhanced sensitivity to estradiol, both in vitro and in vivo.34,35 While the up-regulation of MAP kinase is only transitory for a period of 2–3 months, these cells become hypersensitive to EGF-R mediated pathways. At the same time, we have demonstrated increased complex formation between ER alpha and the EGF-R and between ER alpha and cSRC. These studies also demonstrate that the tamoxifen resistant cells become hypersensitive to the inhibitory properties of the EGF-R tyrosine kinase inhibitor, AG 1478.

Significance of Our Findings to Development of Further Therapies

Our data suggest that cells adapt to hormonal therapy by up-regulation of growth factor pathways and ultimately become resistant to that therapy. Blockade of the pathways involved might then allow enhancement of the duration of responsiveness to various hormonal agents. Studies by Osborne and Schiff etal 36,37 and by Nicholson and his group38,39 have demonstrated this phenomenon both in vitro and in vivo. For example, Schiff and Osborne have treated HER-2/neu transfected MCF-7 cells with a cocktail of three kinase inhibitors: pertuzamab, gefitamab and traztuzamab as well as tamoxifen.40 Each sequential growth factor inhibitor caused a further delay in development of resistance. Only 2/20 tumors began to regrow as a reflection of resistance when the four agents were used in combination (i.e., tamoxifen, pertuzamab, gefitimab and traztuzamab).

There are multiple agents currently in development to block growth factor pathways. Agents are available to block HER-1, 2, 3 and 4; EGF-R, IGF-R, mTOR, MAP kinase, Raf and MEK. Each of these agents might potentially be used in combination with an endocrine therapy. At the present time, this strategy is being used in several studies. A recent presentation demonstrated proof of the principle of this concept. Women with metastatic breast cancer selected to be ERα and HER-2 positive were treated either with an aromatase inhibitor alone or in combination with Herceptin. The percent of patients achieving clinical benefit (i.e., complete objective tumor regression, partial regression or stable disease for > 6 months was 27.9% percent in the aromatase inhibitor alone group and 42.9% in the combined group, a statistically significant (p = 0.026) finding.41 Further studies will be necessary to determine the optimal combinations of growth factor and aromatase inhibitors in the future. However, based upon the Tandem study (examining the efficacy of aromatase inhibitor plus herceptin), this approach appears to be promising.

Synthesis of Our Current inking

Our current working model to explain adaptive hypersensitivity can be summarized as follows. Long term estradiol deprivation causes a four to ten fold up-regulation of the amount of ERα present in cell extracts and an increase in basal level of transcription of several estradiol stimulated genes. The up-regulation of the ER results from demethylation of promoter C of the ER. The lack of shift to the left in the dose response curves of these transcriptional endpoints suggested that hypersensitivity is not mediated primarily at the transcriptional level (Fig. 1 and 2). On the other hand, rapid, nongenomic effects of estradiol such as the phosphorylation of SHC and binding of SHC to ERα are easily demonstrable and appear enhanced in the LTED cells. Taken together, these observations suggest that adaptive hypersensitivity is associated with an increased utilization of nongenomic, plasma membrane mediated pathways. is results in an increased level of activation of the MAP kinase as well as the PI-3-kinase and mTOR pathways. All of these signals converge on downstream effectors which are directly involved in cell cycle functionality and which probably exert synergistic effects at that level. As a reflection of this synergy, E2F1, an integrator of cell cycle stimulatory and inhibitory events, is hypersensitive to the effects of estradiol in LTED cells.7 us, our working hypothesis at present is that hypersensitivity reflects upstream nongenomic ERα events as well as downstream synergistic interactions of several pathways converging at the level of the cell cycle.

It is clear that primary endocrine therapies can exert pressure on breast cancer cells that causes them to adapt as a reflection of their inherent plasticity. Based upon this concept, we postulate that certain patients may become resistant to tamoxifen as a result of developing hypersensitivity to the estrogenic properties of tamoxifen. Up-regulation of growth factor pathways involving erb-B-2, IGF-1 receptor and the EGF receptor are associated with this process.2 The estrogen agonistic properties of tamoxifen under these circumstances might explain the superiority of clinical responses in patients receiving aromatase inhibitors as opposed to tamoxifen. It is possible to counteract the effects of the adaptive processes leading to growth factor up-regulation. If breast cancer cells are exceedingly sensitive to small amounts of estradiol or to the estrogenic properties of tamoxifen, one therefore needs highly potent aromatase inhibitors to block estrogen synthesis or pure antiestrogens such as fulvestrant. Blockade of the downstream effects of the IGF-1-R, EGF-R and erb-B-2 pathways would also be beneficial and allow continuing responsiveness to aromatase inhibitors or tamoxifen.

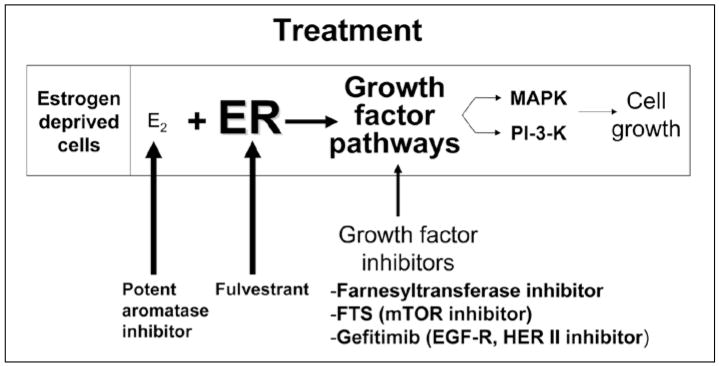

Disruption of each of several key steps could reduce the level of sensitivity to estradiol and block cell growth. Figure 8 illustrates the potential sites for disruption of adaptive hypersensitivity. An agent that blocks the nodal points through which several growth factor pathways must pass might be a more suitable therapy than combination of several growth factor blocking agents. Our preliminary data suggest that FTS blocks two nodal points, the functionality of Ras and the activity of mTOR. FTS also effectively inhibits the proliferation of MCF-7 breast cancer cells in culture. Since this agent blocks MAP kinase as well as mTOR, it may be ideal for the prevention of adaptive hypersensitivity and prolongation of the effects of hormonal therapy in breast cancer. We are currently conducting further studies in xenograft models to demonstrate its efficacy. We envision the possibility that women with breast cancer will receive a combination of aromatase inhibitors plus FTS. In this way, the beneficial effects of the aromatase inhibitor may be prolonged and relapses due to growth factor over-expression might be prevented or retarded.

Figure 8.

Practical implications of the effects of up-regulation of growth factor pathways and development of hypersensitivity to estradiol. Potent aromatase inhibitors are useful to counteract the enhanced sensitivity to estradiol resulting from adaptation to prolonged estradiol deprivation. A pure antiestrogen such as fulvestrant can counteract the up-regulation of the ER that occurs. Growth factor inhibitors such as FTS, farnesyl-transferase inhibitors and growth factor inhibitors such as Iressa and others can be used to block up-regulation of growth factor pathways.

Acknowledgments

These studies have been supported by NIH RO-1 grants Ca 65622 and Ca 84456 and Department of Defense Centers of Excellence Grant DAMD17-03-1-0229.

References

- 1.Santen RJ, Manni A, Harvey H, et al. Endocrine treatment of breast cancer in women. Endocr Rev. 1990;11(2):221–265. doi: 10.1210/edrv-11-2-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McMahon LP, Yue W, Santen RJ, et al. Farnesylthiosalicylic acid inhibits mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) activity both in cells and in vitro by promoting dissociation of the mTOR-raptor complex. J Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19(1):175–183. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Santen RJ, Song RX, Zhang Z, et al. Long-term estradiol deprivation in breast cancer cells up-regulates growth factor signaling and enhances estrogen sensitivity. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2005;12(Suppl 1):S61–73. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shim WS, DiRenzo J, DeCaprio JA, et al. Segregation of steroid receptor coactivator-1 from steroid receptors in mammary epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(1):208–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.1.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shim WS, Conaway M, Masamura S, et al. Estradiol hypersensitivity and mitogen-activated protein kinase expression in long-term estrogen deprived human breast cancer cells in vivo. Endocrinology. 2000;141(1):396–405. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.1.7270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yue W, Wang J, Li Y, et al. Farnesylthiosalicylic acid blocks mammalian target of rapamycin signaling in breast cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2005;117(5):746–754. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song RX. Membrane-initiated steroid signaling action of estrogen and breast cancer. Seminars in Reproductive Medicine. 2007 May;25(3):187–97. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-973431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Song RX, Fan P, Yue W, Chen Y, Santen RJ. Role of receptor complexes in the extranuclear actions of estrogen receptor alpha in breast cancer. Endocrine-Related Cancer. 2006 Dec;13(Suppl 1):S3–13. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yue W, Wang JP, Conaway M, et al. Activation of the MAP Kinase pathway Enhances Sensitivity of MCF-7 Breast Cancer Cells to the Mitogenic Effect of Estradiol. Endocrinology. 2002;143(9):3221–9. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yue W, Wang JP, Conaway MR, et al. Adaptive hypersensitivity following long-term estrogen deprivation: involvement of multiple signal pathways. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;86(3–5):265–74. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(03)00366-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeng MH, Yue W, Eischeid A, et al. Role of MAP kinase in the enhanced cell proliferation of long term estrogen deprived human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2000;62(3):167–175. doi: 10.1023/a:1006406030612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Masamura S, Santner SJ, Heitjan DF, et al. Estrogen deprivation causes estradiol hypersensitivity in human breast cancer cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80(10):2918–2925. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.10.7559875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeng MH, Shupnik MA, Bender TP, et al. Estrogen receptor expression and function in long-term estrogen-deprived human breast cancer cells. Endocrinology. 1998;139(10):4164–74. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.10.6229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13a.Sogon T, Masamura S, Hayashi S-I, et al. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.12.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pelicci G, Lanfrancone L, Salcini AE, et al. Constitutive phosphorylation of SHC proteins in human tumors. Oncogene. 1995;11(5):899–907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pelicci G, Dente L, De Giuseppe A, et al. A family of SHC related proteins with conserved PTB, CH1 and SH2 regions. Oncogene. 1996;13(3):633–641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yue W, Wang JP, Li Y, et al. Farnesylthiosalicylic acid blocks mammalian target of rapamycin signaling in breast cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2005;117(5):746–54. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Migliaccio A, Di Domenico M, Castoria G, et al. Tyrosine kinase/p21ras/MAP-kinase pathway activation by estradiol-receptor complex in MCF-7 cells. EMBO J. 1996;15(6):1292–1300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kelly MJ, Lagrange AH, Wagner EJ, et al. Rapid effects of estrogen to modulate G protein-coupled receptors via activation of protein kinase A and protein kinase C pathways. Steroids. 1999;64(1–2):64–75. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(98)00095-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Valverde MA, Rojas P, Amigo J, et al. Acute activation of Maxi-K channels (hSlo) by estradiol binding to the beta subunit [see comments] Science. 1999;285(5435):1929–1931. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5435.1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song RX, McPherson RA, Adam L, et al. Linkage of rapid estrogen action to MAPK activation by ERalpha-SHC association and SHC pathway activation. J Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16(1):116–127. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.1.0748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dikic I, Batzer AG, Blaikie P, et al. SHC binding to nerve growth factor receptor is mediated by the phosphotyrosine interaction domain. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(25):15125–15129. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.25.15125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boney CM, Gruppuso PA, Faris RA, et al. The critical role of SHC in insulin-like growth factor-I-mediated mitogenesis and differentiation in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. J Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14(6):805–813. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.6.0487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collins P, Webb C. Estrogen hits the surface. [see comments] Nature Medicine. 1999;5(10):1130–1131. doi: 10.1038/13453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watson CS, Campbell CH, Gametchu B. Membrane oestrogen receptors on rat pituitary tumour cells: immuno-identification and responses to oestradiol and xenoestrogens. [Review] [45 refs] Exp Physiol. 1999;84(6):1013–1022. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-445x.1999.01903.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watson CS, Norfleet AM, Pappas TC, et al. Rapid actions of estrogens in GH3/B6 pituitary tumor cells via a plasma membrane version of estrogen receptor-alpha. Steroids. 1999;64(1–2):5–13. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(98)00107-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duan R, Xie W, Burghardt RC, et al. Estrogen receptor-mediated activation of the serum response element in MCF-7 cells through MAPK-dependent phosphorylation of Elk-1. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(15):11590–11598. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005492200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roberson MS, Misra-Press A, Laurance ME, et al. A role for mitogen-activated protein kinase in mediating activation of the glycoprotein hormone alpha-subunit promoter by gonadotropin-releasing hormone. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15(7):3531–3539. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.7.3531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Song RX, Barnes CJ, Zhang Z, et al. The role of SHC and insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor in mediating the translocation of estrogen receptor alpha to the plasma membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(7):2076–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308334100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Song RX, Santen RJ. Role of IFG-1R in mediating nongenomic effects of estrogen receptor alpha. Paper presented at: The Endocrine Society’s 85th Annual Meeting (USA); Philadelphia. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 29a.Levin E. J Biol Chem [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haklai R, Weisz MG, Elad G, et al. Dislodgment and accelerated degradation of Ras. Biochemistry. 1998;37(5):1306–14. doi: 10.1021/bi972032d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harris TE, Lawrence JC., Jr TOR signaling. [Review] [221 refs]. Science’s Stke [Electronic Resource] Sci STKE. 2003;(212) doi: 10.1126/stke.2122003re15. ref 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lawrence JC, Jr, Brunn GJ. Insulin signaling and the control of PHAS-I phosphorylation. [Review] [102 refs] Prog Mol Subcell Biol. 2001;26:1–31. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-56688-2_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brunn GJ, Hudson CC, Sekulic A, et al. Phosphorylation of the translational repressor PHAS-I by the mammalian target of rapamycin. Science. 1997;277(5322):99–101. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5322.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berstein L, Zheng H, Yue W, et al. New approaches to the understanding of tamoxifen action and resistance. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2003;10(2):267–77. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0100267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fan P, Wang J, Santen RJ, et al. Long-term treatment with tamoxifen facilitates translocation of estrogen receptor alpha out of the nucleus and enhances its interaction with EGFR in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67(3):1352–1360. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Osborne CK, Hamilton B, Titus G, et al. Epidermal growth factor stimulation of human breast cancer cells in culture. Cancer Res. 1980;40(7):2361–2366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Osborne CK, Fuqua SA. Mechanisms of Tamoxifen Resistance. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1994;32:49–55. doi: 10.1007/BF00666205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hiscox S, Morgan L, Green TP, et al. Elevated Src activity promotes cellular invasion and motility in tamoxifen resistant breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;97(3):263–274. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hiscox S, Morgan L, Barrow D, et al. Tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer cells is accompanied by an enhanced motile and invasive phenotype: inhibition by gefitinib (‘Iressa’, ZD1839) Clin Exp Metastasis. 2004;21(3):201–212. doi: 10.1023/b:clin.0000037697.76011.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schiff R, Massarweh SA, Shou J, et al. Advanced concepts in estrogen receptor biology and breast cancer endocrine resistance: implicated role of growth factor signaling and estrogen receptor coregulators. [Review] [97 refs] Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2005;56(Suppl 1):10–20. doi: 10.1007/s00280-005-0108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mackey JR, Kaufman B, Clemens M, et al. Trastuzumab prolongs progression-free survival in hormone dependent and HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;100(Suppl 1) S5, Ab 3. [Google Scholar]