Abstract

Attendant to the exponential increase in rates of incarceration of mothers with young children in the United States, programming has been established to help mothers attend to parenting skills and other family concerns while incarcerated. Unfortunately, most programs overlook the important, ongoing relationship between incarcerated mothers and family members caring for their children—most often, the inmates' own mothers. Research reveals that children's behavior problems escalate when different co-caregivers fail to coordinate parenting efforts and interventions, work in opposition, or disparage or undermine one another. This article presents relevant research on co-caregiving and child adjustment, highlights major knowledge gaps in need of study to better understand incarcerated mothers and their families, and proposes that existing interventions with such mothers can be strengthened through targeting and cultivating functional coparenting alliances in families.

Introduction

When mothers of young children are incarcerated, broader problematic patterns often exist in the family (Parke & Clarke-Stewart, 2003; Phillips, Erkanli, Keeler, Costello, & Angold, 2006). Unfortunately, corrections programs designed to strengthen mothers' parenting skills typically focus only narrowly on promoting knowledge-and skill-building, but not on broader family systems issues that will ultimately serve as the context for future maternal involvement (McHale & Sullivan, 2008). As a result, any gains women make in knowledge or skills while incarcerated may be lost if they have no opportunity to participate in decision-making about their children and no meaningful connections to active parenting during the period of incarceration.

To raise consciousness about how these important, broader family issues stand to affect incarcerated women and their children, this article summarizes pertinent conceptual work from coparenting theory and research. Its aim is to familiarize criminologists and corrections professionals with major developments from this rapidly developing field of study. As yet, there have been no studies of coparenting among families in the criminal justice system. In every other family configuration studied thus far by coparenting researchers, however, coordination and cooperation between the different adults responsible for children's care and upbringing has surfaced as a centrally important determinant of young children's social, emotional, and behavioral adaptation. This article identifies several important knowledge gaps clouding the present understanding of coparenting issues in the families of incarcerated women, calls for research attention to these topics, and proposes that skill-building programs offered to mothers during their incarceration may stand a better chance of having positive long-term impacts for children if multi-caregiver parenting frameworks guide such interventions.

The case for effective interventions with incarcerated mothers of young children

Creating effective intervention programs for incarcerated mothers is among the most critical needs in both criminal justice and child welfare systems. Much has been written about how the stress of incarceration amplifies the vulnerability and disadvantage of these already multi-risk women. Devastating effects of maternal incarceration are also seen in women's families, particularly in the adjustment of their children. It is therefore stunning that aside from the approximately 10 percent of children with incarcerated parents who live in the foster care system, the remaining 90 percent are not considered a responsibility of any traditional governmental entity, such as child welfare, mental health, or the juvenile court (Eddy & Reid, 2001).

The data that children are most adversely affected by incarceration of their mothers are plentiful (Catan, 1992; Devine, 1997; Petersilia, 2003; Woodrow, 1992). Infants and young children almost always form enduring attachment bonds with mothers, even when their mothers are absent for extended periods of time (Vaughn, Egeland, Sroufe, & Waters, 1979). Overwhelmingly, data indicate that there has typically been ample opportunity for mother-child bonding before maternal incarceration; while many mothers do not reside with their children at the time of incarceration, only 20 percent have never lived with their children (Johnston, 2001a). Furthermore, when mothers are incarcerated it is typically maternal grandmothers and other kin, not children's fathers, who step up to care for them if they are not fostered out (Baunach, 1985; Enos, 2001; Glick & Neto, 1977; E. Johnson & Waldfogel, 2003; Snell, 1994; Zalba, 1964). Since 75 percent of children with incarcerated mothers also have criminally-involved fathers (Phillips et al., 2006), most fathers do not parent actively while mothers are away. Provision of care by members of mothers' kin network is far more common in all ethnic groups, and is especially commonplace in Black and Hispanic families (Goodman & Silverstein, 2006; Hairston, 2003).

The dynamics of caregiving involvement by members of incarcerated mothers' kinship networks are poorly understood, despite their critical importance. Correctional facilities operate from an implicit assumption that mothers will ultimately go back to playing a meaningful role in their family (Johnston, 2001b; Newberger, 1999). For the majority of those who do, they reenter a system where grandmothers or other kin caregivers have been parenting their children. That is, unlike incarcerated fathers, who rely on their children's mothers to enable contact with children during and after their incarceration (Roy & Dyson, 2005), mothers' contact with children is enabled most often by grandmothers and not fathers. Since mother-grandmother relationships do tend to endure during women's incarcerations, mothers' ongoing contact with their children while incarcerated can be much greater than fathers (Johnston & Carlin, 2007). Despite a wealth of anecdotal and qualitative evidence, however, relatively little is known about the within-family dynamics that do enable or impede maternal reunification with children following reentry. Hence, this article will outline dynamics likely to operate when incarcerated mothers and family caregivers co-raise children. It will also outline how the nature of these coparenting dynamics might be expected to affect young children's adaptation, for good or for ill, both during and after the mother's incarceration (Myers, Smarsh, Amlund-Hagen, & Kennon, 1999; Parke & Clarke-Stewart, 2003).

The central focus of the following review will be on co-caregiving relationships in extended kin systems, the most typical family circumstance for incarcerated mothers. Contrasts, however, will be drawn to nuclear family arrangements as is fitting.

Coparenting, co-caregiving, and the co-raising of young children

What exactly is a co-caregiving alliance, and what is the basis for positioning that such an alliance could be valuable in supporting children's socio-emotional and behavioral adaptation during maternal incarceration? The concept of co-caregiving, related in many but certainly not all ways to the kindred concept of coparenting, stems from Salvador Minuchin's (1974) theory of adaptive family structure. In families that function most effectively during times of acute stress, there is a functional family hierarchy wherein caregiving adults in the system function together as the family's architects and decision-makers. These “coparenting” individuals share the executive power in the family system. They work collaboratively as a team, with no one member of the team wielding unilateral or undue power, no coparenting adult excluded from their role in the hierarchy, and no overt or covert presses on children to triangulate them into a position of having to form a coalition with one coparenting adult against the other (which disrupts the functional family hierarchy). Hence an effective coparenting alliance is comprised of adults working together to demonstrate to the children that there is solidarity and support between them, as well as safety and security within the home and a set of consistent rules and principles (McHale, Lauretti, Talbot, & Pouquette, 2002).

In the case of multi-generational extended kinship systems, grandmothers or other relatives assume responsibilities for children in their parents' absence. Such systems can likewise be characterized by a spirit of partnership and alliance between children's mothers and the caregiving relatives, or by an air of contentiousness, strain, and resentment (Young & Smith, 2000). Indeed in most families, there are undoubtedly elements of both. Unfortunately, strain and resentment complicate decision-making on the child's behalf, and decision-making must be handled effectively and cooperatively by involved caregivers to serve the child's best interests (c.f. Parke & Clarke-Stewart, 2003). Herein lies perhaps the most direct link to studies of inter-caregiver collaboration or antagonism in nuclear families—cooperation and collaboration between caregivers provide a supportive structure enabling children's adaptation, while disputes about children can harm not only children, but adults as well (Bearss & Eyberg, 1998; Gabriel & Bodenmann, 2006; Goeke-Morey, Cummings, Harold, & Shelton, 2003; Grych & Fincham, 1993).

The benefits of cooperation between the adults responsible for children's care and upbringing are many. When the alliance between caregivers is characterized by greater solidarity, children show better self-regulation at home and at school; more pro-social peer behavior; greater comfort in talking about family anger, and greater empathy and emotional understanding (Lindahl, 1998; Lindahl & Malik, 1999; McHale, 2007; McHale & Cowan, 1996; McHale, Johnson, & Sinclair, 1999). By contrast, when detachment, antagonism, and animosity between coparents is present, children show more substantial behavioral problems, including interpersonal aggression (particularly among boys); higher levels of anxiety and withdrawal (especially among girls); propensities to invoke aggressive and conflict-ridden imagery when portraying family relationships; and a greater likelihood of insecure parent-child attachments (V. Johnson, 2003; Katz & Low, 2004; McConnell & Kerig, 2002; McHale & Rasmussen, 1998; Schoppe, Mangelsdorf, & Frosch, 2001).

Statistically, coparenting adjustment accounts for variability in child outcomes unexplained by either parent-child or connubial functioning (Belsky, Putnam, & Crnic, 1996; McHale et al., 1999). In other words, coparenting functionality or dysfunction is a potent family force that is separable and distinct from parenting competencies or conjugal adjustment. This is an important finding, as it indicates that the essence of the coparental alliance can transcend nuclear family arrangements (Ahrons, 1981; Brody, Flor, & Neubaum, 1998; McHale, in press; McHale, Khazan, et al., 2002). This principle will be discussed in further detail below. It is doubly important because it reveals that solidarity between coparenting adults can mitigate negative effects of problematic parenting or other significant family problems (Katz & Low, 2004). Unfortunately, the opposite is also true; contentiousness between parenting adults heightens children's risk for adjustment difficulties, even in the absence of other appreciable family risks (McHale, Kuersten, & Lauretti, 1996).

Co-caregiving in extended kinship systems

In extended family systems, where grandmothers and other family members frequently shoulder a great deal of the responsibility for raising grandchildren (Hairston, 2003), coparenting research is not as extensive. There are, however, relevant data. Kellam, Ensminger, and Turner (1977) reported that mother-grandmother teams were as effective as mother-father teams in raising children, with children from both kinds of family systems showing better social and emotional adjustment than children from families with no coparent or co-caregiver. Barbarin and Soler (1993) likewise found that compared with children from families without a second caregiver, children who had a second resident caregiving adult (grandmother, father, other adult) had a lower prevalence of problem behavior.

This said, interpersonal factors within the family appear to be key (Coley & Chase-Lansdale, 1998; Kalil, Spencer, Spieker, & Gilchrist, 1998). When mothers and grandmothers care for children together, dissonance between the parenting adults adversely affects children in much the same way as does dissonance between biological parents (Brody et al., 1998). Apfel and Seitz (1991, 1999) found that for young, unmarried inner city African American teen mothers, both (a) the absence of caregiving involvement by maternal grandmothers and (b) the supplanting of mothers by grandmothers who commandeered care of the baby forecast the most adverse outcomes (e.g., mother having a second baby in rapid succession; mother no longer being responsible for the care of the index child on that child's twelve-year birthday). Balanced levels of grandparental co-caregiving support and involvement were associated with the best adjustment. In Brooks-Gunn and Chase-Lansdale's (1995) study of inner-city grandmothers and teenaged mothers, ambivalence and resentment in the mother-grandmother co-caregiving arrangement were quite commonplace.

Most studies that have investigated co-caregiving in kinship systems have focused rather narrowly on grandmaternal involvement in families with teen mothers. Far less is known about co-caregiving alliances between grandmothers and older women the age of most incarcerated mothers. In fact, a reading of relevant literature on this topic would seem to suggest that such family adaptations are relatively uncommon. Most published empirical studies of grandmaternal caregiving portray grandmothers as simply having “taken over.” That is, grandmothers are seen as replacements for mothers, the new de facto primary caregivers for grandchildren who were formally or informally placed in their custody because of child abuse and neglect, or parental drug involvement and incarceration (Brooks, Webster, Berrick, & Barth, 1998; Geen et al., 2001; Glick & Neto, 1977; Hunter & Taylor, 1998; Minkler & Roe, 1993; Waldrop, 2004). Unfortunately, beyond Harden, Clark, and McGuire's (1997) look at informal kinship care, little is known about stable and enduring mother-grandmother co-caregiving partnerships, such as those families commonly form for economic reasons such as under- or unemployment (Hogan, Hao, & Parish, 1990; Stack, 1974).

On their side of the equation, African American grandmothers do warrant legitimate identification as “parents.” Minkler and Fuller-Thompson's (2005) report on African American households based on the Census 2000 Supplemental Survey/American Community Survey (C2SS/ACS) (U.S. Census Bureau, 2000) found that 47 percent of households in which grandparents were responsible for most of minor children's basic needs were skipped generation households (without the grandchildren's parents in residence), while the remainder had at least three generations co-residing. Seventy-one percent of caregiving grandmothers sampled were age fifty-five or older, indicating that the mothers of their grandchildren were no longer teens. Eighty-one percent of grandparents had looked after grandchildren for over a year.

These data, together with a more recent report from Pittman and Boswell (2007), substantiate that grandmothers are appropriately cast as parenting figures even if they do not always reside with grandchildren, but say nothing about how frequently families maintain an ongoing relationship in which the child's mother is also a recognized care provider. Indeed, even in families when grandmother regularly cares for the child and mother is in residence and involved, numerous possibilities exist. Mother's presence can be episodic, erratic, nebulous, and even altogether absent despite her ostensible co-residence. Nonetheless, census data at minimum help confirm that mother-grandmother co-resident households are not uncommon family adaptations, at least among African American communities, and that they do exist in large numbers in families where the grandchild's mother is beyond teen-age motherhood. Unfortunately, until the relevant studies have been conducted, interventionists can draw only from clinical, anecdotal, and incomplete empirical evidence implying that mothers and grandmothers have jointly assumed some responsibility for the young child's upbringing in a great many lower socioeconomic families and families of color (Goodman & Silverstein, 2006).

At such a time when data do eventually allow one to verify the existence and operation of mother-grandmother co-caregiving alliances in families, there will remain a variety of unique and important differences between nuclear and multi-generational family systems important to consider. Perhaps of greatest consequence, a common coparenting dynamic in many nuclear families is for mothers to quickly develop greater expertise with infant and young children than fathers. In some families, mothers' greater expertise can translate into “gatekeeping” behavior, or the regulation of paternal involvement with children. By contrast, mothers in all three generational co-caregiving households inevitably possess less, rather than more, of the family's caregiving knowledge and expertise. The ramifications of this knowledge gap vary from family to family, depending on family composition, living circumstances, and a number of other contextual factors. Overall, however, this distinction between mother-father coparents and mother-grandmother co-caregivers is a critically important one for understanding the range of possible ways in which mother-grandmother relationships are likely to adapt both normatively and during periods of maternal absence and incarceration.

In summary, research has established that positive coparenting alliances (characterized by high levels of inter-parental support and solidarity, and low levels of inter-parental antagonism, undermining, disparagement, and detachment) promote the social and emotional health of toddler and preschool-aged children in nuclear families. This is so even, and perhaps especially, when one or both parents are struggling individually. It is unclear whether inter-adult co-caregiving alliances play as critical a role in non-nuclear family systems, though such solidarity does appear relevant for child adjustment in multi-generational family systems where the ongoing coparental “team” is comprised of the child's mother and the mother's mother (Brody et al., 1998; Goodman & Silverstein, 2006). Largely as a result of this knowledge gap, very little is known about the adaptations made by and within mother-grandmother co-caregiving alliances during maternal incarceration, or about the extent to which greater solidarity between mothers and grandmothers during an incarceration helps to effectively buoy children's immediate and longer-term adaptation.

The next section focuses more explicitly on the relevance of the co-caregiving model for criminologists. It discusses considerations for multi-generational family units coping with incarceration. It also outlines how the child behavioral and developmental indicators that are most directly affected by co-caregiver solidarity are precisely the ones that forecast eventual child delinquency. For these reasons, the model outlined below holds heuristic value for both basic and applied research in the field of criminology.

Inter-caregiver solidarity and adjustment among children with incarcerated mothers

To build a co-caregiving alliance or to discourage children's ties with mothers?

Unfortunately, despite data substantiating kin involvement in families where mothers are incarcerated, very little is actually known about specific roles grandmothers and other family members play in cultivating or undermining children's active ties with their mothers while the mothers are incarcerated. It seems reasonable to expect at least some parallel with studies of fathers, which find that men's success in maintaining ties with children during and after incarceration can be traced principally to the quality of the ongoing relationship he shares with the children's custodial mother (Nurse, 2001, 2002). Research with men also has indicated that fathers who maintain family ties during incarceration adapt more successfully upon release than those who do not (Dowden & Andrews, 1999; Hairston, 1988, 1991; Slaght, 1999).

This said, matters are more complicated where mothers are concerned. It certainly seems reasonable that grandmothers would do more to keep mother's presence active in children's minds and to foster children's contacts with mothers if the two women get along. It is less clear whether family contacts while mothers are incarcerated will have the same salutary effect on post-release adjustment as they appear to have for fathers—one operative variable will certainly be the degree and quality of general family social support; however, mothers vary to a great extent in how ready they are to put the pieces of their family life back together quickly.

This variability is evident in O'Brien's (2001) qualitative study of factors promoting women's successful reentry after incarceration. Many, perhaps most, women do not immediately resume living together with children, embarking on a more gradual process of reassumed responsibility after developing a modicum of financial and emotional stability (O'Brien, 2001). Even among those who do move immediately back in with family and rejoin their children, mending problematic family relationships is often of great concern. Ten of the eighteen mothers in O'Brien's sample described their relationships with their mothers as historically problematic, and sometimes abusive. Hence resuming a co-equal or primary maternal role is a quite different undertaking for mothers than is father's work in reestablishing basic contact with children.

The process by which mothers and grandmothers or other caregiving relatives share the care of young children before their incarceration, and resume this relationship after mothers are released, is a critical empirical question in need of dedicated attention. At the moment, only informed speculation is possible. For despite the pragmatic importance of understanding the possible benefits of co-caregiving support for the adjustment of incarcerated mothers and their young children, it is not yet known whether and which children are better served by strengthened solidarity between mothers and grandmothers than by complete disconnection from mothers. Moreover, a variety of factors undoubtedly determine whether grandmothers would consider promoting a continuing sense of solidarity between themselves and children's mothers during periods of incarceration. Among these would be the extent to which the two women actually had a history of working collaboratively to co-raise the child, the presence or absence of any additional important family figures, such as the child's father or paternal grandparents, the quality of the preexisting relationship between grandmother and mother, and the extent to which grandmothers saw mothers as assets or threats to the child.

Hence the issue is not nearly as straightforward as whether strong and supportive coparenting alliances benefit adults and children during periods when mothers are away. Strong co-caregiving solidarity should be of tremendous benefit to children when it exists—especially when the mother is herself struggling with parenting or mental health issues—a proposition following both from coparenting theory and research (e.g., Katz & Low, 2004; McHale, in press; McHale, Khazan, et al., 2002; Minuchin, 1974), and from prior investigations of incarcerated parents documenting the benefit of family support for post-incarceration adaptation (Burstein, 1977; Fishman, 1986; Seymour, 1998). Where no historical co-caregiving alliance exists, or when there is extreme animosity or emotional cutoffs between mother and grandmother, the severance of ties with mother could potentially lead to better child outcomes in some cases. At the moment, however, there is no sound research evidentiary base on which to hinge such judgments or to guide intervention approaches in work with families.

The focus of the past few sections has been principally on grandmothers. This was apt, as grandmothers are female inmates' most stable sources of support and most frequent visitors, on top of the role they play in caring for their daughters' children (Hairston, 1992, 1995). Viable and open relationships between incarcerated mothers and children's fathers, or other caretaking relatives, however, undoubtedly also benefit children. The capacity to productively problem-solve about the child together, maintain a generally consistent and shared system of child-rearing beliefs and practices, and keep a spirit of collaboration and affirmation of one another's parenting authority to the children will enhance children's sense of the family's integrity in the smaller percentage of cases where they, and not grandparents, function as the family's other major coparent.

Having said this, the opposite is also likely to be true. To the extent that the co-caregiving dynamic between the incarcerated mother and whomever the important custodial parenting figures might be is contentious and colored by antagonism, derision, undermining, or demeaning of one another's parenting credibility, children cannot derive a sense of safety, cohesion, and family-level security. In these latter circumstances, children suffer yet another form of worry, confusion, and uncertainty, entrapped by loyalty conflicts and choosing sides (c.f. Maccoby & Mnookin, 1992; McHale & Sullivan, 2008). Research is needed on the kinds of communications family caregivers have with children about their mothers while mothers are in jail, as such communications likely run the full gamut from affirmation and support to denigration and emotional cutoff, depending on the family.

Over the long haul: why co-caregiver solidarity is important for at-risk children

Thus far, most of what is known about co-caregiving solidarity and child adjustment has come from studies of families with very young children. This is actually useful, and important for several reasons. Take for example the finding that solidarity between caregiving figures can help to foster secure attachments (Caldera & Lindsey, 2006; Frosch, Mangelsdorf, & McHale, 2000). This finding is of major significance, as children's bedrock sense of emotional security is almost fully cultivated by the end of the infant and toddler years. Once an expectation of instability and chaos has been entrained as the child's root “first response,” it can have a lifelong organizing effect (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978; Bowlby, 1988). By contrast, the early socio-emotional competencies that secure attachments breed serve as assets for the child when he or she faces major stresses later on. Developmental trajectories toward conduct problems, crime, and delinquency can be charted early on (Farrington & Welsh, 2007), but such trajectories can be waylaid when children possess capacities that help them to make successful adaptation as they mature.

This point bears repeating. While risk is endemic to families contending with maternal incarceration, certain children are at greatest risk than others for later delinquent and criminal behavior themselves, while others may be protected by factors that buffer them from negative outcomes. While risk and protective factors vary depending on the child's age, the infant, toddler, and early childhood years are uniquely important because most core socio-emotional competencies are taking firm root during those years. For example, the infant and toddler years are when children develop foundational regulatory capacities, without which early onset of delinquency is exponentially more likely—especially when concurrent risk operates in the child's family system and in systems surrounding the family (Farrington & Welsh, 2007; Wasserman et al., 2003). Indeed, this is the major reason why preventive efforts must target multiple risk domains. From an intervention standpoint, child and family assets are equally important to address because protective factors can mitigate risk effects (Farrington & Welsh, 2007). Though less is known about protective factors, co-caregiving solidarity qualifies as one such family asset. Collaborative and supportive coparenting alliances promote numerous critical socio-emotional competencies in early childhood; divisive or detached coparenting alliances heighten adjustment problems in young children (McHale, 2007).

Most studies of co-caregiving solidarity and child adjustment have studied children only over the short-term, documenting positive benefits for periods up to three or four years. Less is known about more distal benefits for adolescents. Given the essential foundational skills and competencies inculcated by supportive coparenting in families, however, solidarity and cooperation between mothers and other caregivers when children are young hold the potential for dampening longer-term delinquency risk. Both the criminal justice and social welfare systems are concerned about the heightened risk for delinquent and criminal behavior among children of incarcerated parents (Gabel & Johnston, 1995). It hence would be sage for each system to examine potential benefits of promoting cooperation and coordination between incarcerated women and their children's co-caregivers as one possible means of buffering children from lifetime risk.

In the absence of coparenting solidarity, children develop behavioral problems, including both interpersonal aggression and anxiety and other internalizing symptoms; cultivate dissonance-ridden imagery of family relationships; display immature emotion skills; exhibit greater insecurity in parent-child attachments; and manifest problems in development of conscience (Belsky et al., 1996; Caldera & Lindsey, 2006; Groenendyk & Volling, 2007; see McHale, 2007, in press, for review). These findings should resonate with criminologists, who know well that deficient social cognitive skills, negative temperament, high impulsivity, and poor empathy all place children at elevated risk for later antisocial and delinquent behavior (Farrington & Welsh, 2007). For example, children identified as difficult to manage as early as age three are at heightened risk for later antisocial behavior (White, Moffitt, Earls, Robins, & Silva, 1990). Preschool conduct problems are a risk factor for later delinquent, criminal, and antisocial behavior (Loeber, Stouthamer-Loeber, & Green, 1991; White et al., 1990). Physical aggression in kindergarten predicts later involvement in property crimes (Haapasalo & Tremblay, 1994; Tremblay, Pihl, Vitaro, & Dobkin, 1994). More generally, undue behavioral activation (sensation seeking, impulsivity, hyperactivity, aggression) in the absence of compensatory behavioral inhibition (fearfulness, timidity, anxiety, or shyness) carries risk for future antisocial behavior (Wasserman et al., 2003).

Parenting factors that escalate children's risk for delinquent, criminal, and antisocial behavior have been well chronicled. They include chaotic management styles, aggravated parent-child conflict, inadequate parental monitoring, absence of positive engagement with children, attachment problems, and destructive inter-adult conflict (Farrington & Welsh, 2007; Hawkins et al., 1998; Henry, Moffitt, Robins, Earls, & Silva, 1993; Herrenkohl, Hill, Hawkins, Chung, & Nagin, 2006; J. G. Johnson, Smailes, Cohen, Kasen, & Brook, 2004; Lipsey & Derzon, 1998; Loeber & Stouthamer-Loeber, 1986; C. A. Smith & Stern, 1997; Wasserman, Miller, Pinner, & Jaramillo, 1996). Note, however, that all but the last of these factors pertain to parent-child relationships, not parent-parent-child relationships.

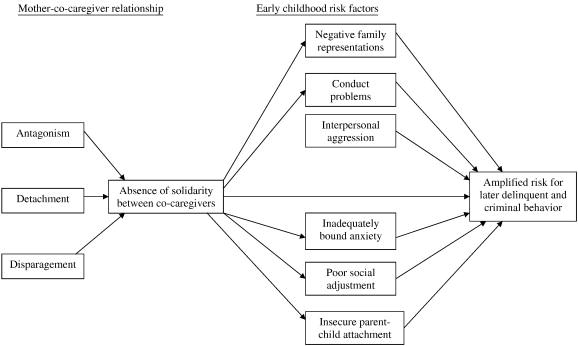

By way of synopsis, Fig. 1 summarizes problems in the family's co-caregiving relationship that can cultivate the kinds of problems placing children at longer-term delinquency risk. Given the wide array of problems that emanate when co-caregivers parent children incompatibly, programming that enables and strengthens communication between mothers and custodial caregivers during the mother's time away stands to have immense benefit. A focus of any effective coparenting intervention is helping the adult caregivers to stay focused on communicating and working together to meet the child's needs. Such intervention also helps adults to recognize and validate one another's formative caregiving impact, contain differences about what's best for the child, and sidestep urges to denigrate one another's character or authority to the child would help solidify a family co-caregiving alliance. By so doing, they help bolster the child's confidence in the family's cohesiveness and experience of family-level security—during the incarceration period. Indeed, intervention at a time during which the child may be experiencing acute fears about family collapse would help dampen child adjustment problems that, once present, often crystallize and amplify eventual lifetime risk.

Fig. 1.

Co-caregiving problems and indicators of early childhood risk

As emphasized previously, it is not only the forestalling or reduction of problem behavior that should be of concern. Ideally, interventions should be concerned with promoting the protective skills and competencies that allow children to avert the eventual risk situations that would otherwise groom them for future involvement in delinquent and criminal behavior. These skills include the capacity for effective behavioral regulation, especially under stress, at both home and at school; the capacity to form and maintain positive peer connections; facility in thinking and talking about negative emotions; and capacity for empathy and emotional understanding. These are all competencies enhanced by greater coparental solidarity (Lindahl, 1998; Lindahl & Malik, 1999; McHale & Cowan, 1996; McHale et al., 1999). When young children respect authority, value the importance of honesty, and use nonaggressive problem-solving techniques as their cognitive and verbal abilities multiply during the preschool years, trajectories toward later delinquency are less likely (Kelley, Loeber, Keenan, & DeLamatre, 1997). Pro-social relationship patterns decrease children's risk of disruptive and delinquent behavior (Kelley et al., 1997), while the absence of pro-social skills (particularly the capacity for empathy) during the preschool years is especially prognostic of criminal behavior by age thirteen (Wasserman et al., 2003).

Another key point emphasized above was how co-caregiving solidarity supports bonding and attachment (Caldera & Lindsay, 2006; Frosch et al., 2000). Criminologists have come to appreciate how secure attachments to parents during childhood and adolescence promote healthy relationships, which themselves reduce risk of delinquency (Cernkovich & Giordano, 1987; Cota-Robles & Gamble, 2006; Hagan, Simpson, & Gillis, 1988; Sampson & Laub, 1994; C. A. Smith & Krohn, 1995). A particularly important finding from attachment research has been that maternal absence can—but need not necessarily—jeopardize attachment security; Martin (1997) outlined how incarcerated mothers are able to nurture attachments with their young children if they have the support of their families and kin. In this way, co-caregiving solidarity can be especially critical in sustaining attachment quality between incarcerated mothers and young children, with a longer-term payoff in reduced delinquency risk as children age.

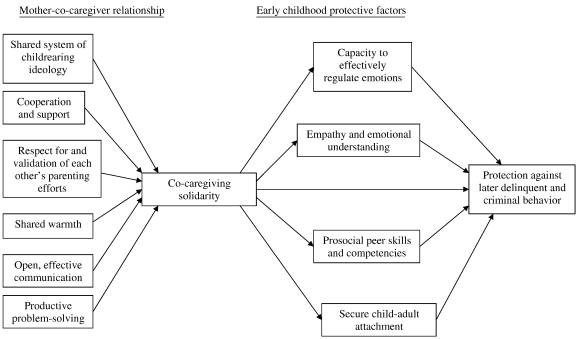

Perhaps most pertinent to the case being made here are data indicating that the risk of problem behaviors increases exponentially as there are changes in a child's caregiver, for many of the reasons outlined (e.g., Henry et al., 1993). Notably then, Fergusson, Horwood, and Lynskey (1992) reported that accord and unanimity between adults helps to offset this risk. For these reasons, it is important to consider not only the potential risk induced by inter-caregiver divisiveness, but also the potential protection afforded by inter-caregiver solidarity and support. Fig. 2 summarizes how solidarity within co-caregiving relationships between mothers and caregiving relatives during and following incarceration might be expected to positively benefit children.

Fig. 2.

Co-caregiving solidarity and early childhood protective factors

When young children become depressed, withdraw emotionally, develop sleeping and eating problems, begin exhibiting disruptive behavior, or engage in aggressive or violent outbursts, it is crucial that there be a measured and coordinated response from the important caregivers in their lives (McHale, 2007). Supportive, consistent, and predictable caregiving provided by the different adults who care for children helps to allay children's anxieties and enable them to focus on mastering the important developmental challenges they face. By contrast, the absence of a supportive alliance between caregiving adults introduces new emotional stresses and prevents children from age-appropriate mastery. For these reasons, parenting work with incarcerated mothers should always include assessments of whether any co-caregiving relationship exists and if so, whether it is a hostile, benign, or collaborative one. This step is particularly crucial given that mothers have had to abdicate any parenting responsibilities they had upheld. To reiterate a point made earlier: corrections efforts to bolster maternal capacities that do not also attend to the family's overall caregiving landscape are unlikely to reap enduring benefits.

New directions for family strengthening efforts: summary and research agenda

To summarize: the literature reviewed strongly suggests that working with incarcerated mothers in a vacuum can be expected to have minimal impact on the women's chances at successful family reintegration upon reentry. At the moment, there are a number of poorly understood issues in need of concentrated study before maximally effective corrections programming can commence. Most of these issues will profit from a multidisciplinary approach and from partnerships between corrections professionals and experts in social work, developmental, and family psychology.

First and foremost, interventionists must be able to operate from a far more complete understanding of the co-caregiving relationships that exist between incarcerated mothers and the grandmothers (or other related-caregivers) who care for their children than is currently available. For this to happen, incarcerated mothers themselves must be given voice to provide their perspectives on the individuals besides themselves who they believe to be the most salient, ongoing caregivers in their children's lives. These individuals should then be part of reentry planning to every extent possible (see below). Of course, mothers' perspectives should obviously be augmented by the perspectives of these custodial caregivers and when possible, of their children to attain a complete understanding of the family's situation, assets, and impediments to resumption or initiation of effective coparenting in the child's best interests.

In this regard, mothers' and custodial caregivers' perspectives on their current and future prospects as coparents for the child will also need to be understood in the context of the ongoing within-family co-caregiving dynamics present in the extended kinship network long before the mother's current incarceration. Interventions with incarcerated mothers would necessarily need to vary as a function of how the current custodial caregiver came to her or his involvement in the shared parenting system. Circumstances in families where the current caregiver had shared parenting with the mother over many years will be different from circumstances in which the current caregiver always functioned as the child's primary parent, with mothers more of a peripheral figure. In still other families, the current caregiver will have stepped in as an emergency measure but without a long history of having been custodial or having coparented the child over many years. These issues are also central to understanding the child's adjustment, as continuity in care is an important determinant of the quality of the child's adjustment during and upon mothers' release from incarceration.

With respect to the period of incarceration itself, it is vital that interventionists develop a handle on the different types of adaptations that families make while mothers are away. The position taken in this article is that children can be expected to benefit if mothers and family caregivers cooperate and communicate about the child during mother's absence. This stance is antithetical to the position that children may be best off without the mothers in their lives—the fallback position of many corrections and helping professionals, custodial caregivers, and even many mothers themselves (Enos, 2001). As noted, while few data actually speak to this issue, the authors have not previously been in a proper position to even call the question without the coparenting framework outlined in this article. It is important to now elucidate what custodial caregivers can do and are doing to either strengthen or undermine mothers' standing with their children during mothers' absence, and what enduring impact it has on children when caregivers collude to disenfranchise mothers. Studies of this nature must also begin employing direct measures of the affected children's well-being and adaptive skills, rather than relying simply on behavior reports from the adults in their lives.

Finally, research is needed on the institutional obstacles to strengthening mother-coparent relationships during periods of incarceration. Were corrections programs to take coparenting models to heart, what might they be in a position to do to enable mother-coparent communications about children during the jail sentence? This issue is addressed in a final section, how corrections professionals might alter services for incarcerated mothers if they weighed the potential benefits of adopting a coparenting model.

Implications for programming

Corrections staff never work in an institution for very long before they begin hearing virtually all inmates discuss their current relationships with their children. There is hence tremendous opportunity to leverage the momentum created in the family system when a mother is incarcerated. Should the kinds of research advocated in this article solidify the case for working with incarcerated mothers and the family members caring for their children, creative thought will be needed to reallocate existing resources so as to effectively structure useful interventions.

The child and family advocacy model developed in this article is being advanced at a historical juncture when most United States jails face barriers in contemplating additional new programming for inmates. Budgets and public opinion regarding the efficacy and economy of programming have held institutions more accountable than ever to produce enhanced results with reduced funding. At the same time, this is a point in the country's political landscape affording an opportunity to capitalize on national sentiment for development of services concerned with release. Such efforts fit squarely in the purview of reentry planning.

Jails have historically been treated as either a “first step” or a “last stop” to prison, with programming philosophies that reflect each approach. Current trends expand both of these definitions, clarifying the real role that jails play in the criminal justice arena. From the vantage of Minuchin's (1974) coparenting paradigm, however, it becomes apparent that jails play an important gatekeeping role in determining whether meaningful contact and communication between coparenting adults will be facilitated or discouraged. Program decisions hence can and do play a central role in advancing the disruption or protection of the functional family hierarchy for incarcerated mothers.

Practically, inherent barriers such as jail location, staffing capacities, and security concerns affect the capacity of jail administrators to provide a proactive environment for mothers and grandmothers to develop or improve their coparenting alliance; but there are also institutional barriers that may be less inflexible. These include visitation policies, program content and availability, staff training and attitude, and community in-reach. If research efforts establish the value of developing/improving the bond between inmates and their children's co-caregivers, jails and prisons can be encouraged to look closely at how to best deliver negotiable items for the benefit of their children.

What are the current possibilities? For institutions fortunate enough to have resources, current programming could be enhanced to include work on the coparenting alliance fairly easily. Parenting courses could begin including training on how children are affected by positive co-caregiving alliances, on how inmates can effectively communicate with their children's caregiver when inevitable differences of opinion about parenting surface, on steps toward improving coparenting alliances post-release, on how the family system will be affected, and how it can move positively forward upon the inmate's release. More advanced considerations such as allowing contact visitation in order that mothers and caregivers might be able to discuss children directly, training of staff in skills required to facilitate family communication, and creating opportunities for caseworkers to discuss parenting and coparenting issues in transition planning with both parties can be implemented or refined.

For institutions with fewer resources, enlisting community agencies to work with family caregivers in the community or with mothers in the institution may be feasible. Personnel from child welfare agencies, the education system, and other child-centered entities could be invited and enabled to use the institution as a safe and secure place in which to initiate family connectedness. Indeed, services initiated during maternal incarceration that remained available to families following release would stand the greatest chance of sustaining gains achieved during the jail sentence.

Conclusion

Findings from dozens of studies of coparenting have been quite clear and consistent: when there is genuine support and solidarity in the family's coparenting alliance, children show better adjustment. When there is divisiveness, disparagement, contentiousness, and detachment, children are more likely to struggle. The crucial value of equipping children with necessary socio-emotional competencies when they are very young to help them circumvent problem trajectories is well documented by a criminological literature dealing with the roots of delinquency and criminality. Helping families collectively and proactively support the ongoing development of important social and emotional skills in young children during their mothers' incarceration may have the longer-term payoff of reducing risk for delinquent and antisocial behavior.

Incarcerated mothers almost uniformly voice desires to do the right thing for their children (Kazura, 2001; O'Brien, 2001; A. Smith, Krisman, Strozier, & Marley, 2004). The problem, of course, is that they frequently find actualizing these maternal wishes next to impossible given their circumstances (Radosh, 2002). For these reasons, planned efforts to promote communication and strengthen relations between the incarcerated mother and her child's caregiver can only be helpful. Coparenting is not so much about “who does how much” parenting as it is about the creation and maintenance of a unified front respected by all caregivers. It is this solidarity and unity that most benefits children—even, and especially, in one parent's absence (McHale, 1997).

It is not only children who stand to fare better if mothers remain connected with other caregivers in a supportive coparenting alliance during the period of incarceration. Most women will face intense challenges upon their release that will hinder their ability to remain crime free and to reunify with their children. If meaningful dialogues about the child and about the importance of co-caregiving cooperation and support for children can be cultivated prior to release—even if such dialogues are supported simply through episodic and emblematic visitations and coordinated supports afforded programmatically by social work staffers—this would go a long way toward empowering mothers during their reentry into the community and their children's life (Hairston, 1988; Visher & Travis, 2003).

Clearly, there are major impediments to developing and advocating such a model. Incarcerated women are pathologized as inadequate parents, even when they do possess parenting desires, skills, and capacities. Relatives, much as they care for their daughters, are prone to buy into the failed mother perspective, as are mothers themselves (Enos, 2001). In families where custodial relatives harbor such level of concern that they do not want the mothers in the children's lives, there is probably very little that heightened awareness of the importance of coparental solidarity will do to alter this dynamic. There are certainly many families that fit this description in the criminal justice system; but the collective experience of the authorship team is that they are not the majority. Most mothers do go on to play meaningful, if sometimes limited, parenting roles in the lives of their children and for these reasons, efforts to preserve or rekindle the connection they and the custodial relatives maintain about the child stand to reap potentially far-reaching benefits.

Incarcerated mothers and their children and families already labor with far too few resources; finding ways to cultivate one such resource that lies at the center of healthy and adaptive functioning in all families seems a logical and humane place to start.

Acknowledgments

Work on this manuscript was supported by National Institute of Child Health and Development grant R21, “Incarceration, co-caregiving, and child adjustment” (J. McHale, Principal Investigator; A. Strozier & D. Cecil, Co-Principal Investigators) and by NICHD CAREER award K02 HD47505 to the second author.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Dawn K. Cecil, Department of Criminology, University of South Florida, 140 Seventh Avenue South, St. Petersburg, FL 33701

James McHale, Department of Psychology, University of South Florida, St. Petersburg, FL 33701.

Anne Strozier, School of Social Work, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL 33620.

Joel Pietsch, Inmate Treatment and Intervention Section, Hillsborough County Sheriff's Office, Tampa, FL.

References

- Ahrons CR. The continuing coparental relationship between divorced spouses. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1981;51:415–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1981.tb01390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth M, Blehar M, Waters E, Wall S. Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Oxford, England: Erlbaum; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Apfel N, Seitz V. Four models of adolescent mother-grandmother relationships in Black inner-city families. Family Relations. 1991;40:421–429. [Google Scholar]

- Apfel N, Seitz V. Effective interventions for adolescent mothers. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 1999;6:50–66. [Google Scholar]

- Barbarin OA, Soler RE. Behavioral, emotional, and academic adjustment in a national probability sample of African American children: Effects of age, gender, and family structure. Journal of Black Psychology. 1993;19:423–446. [Google Scholar]

- Baunach P. Mothers in prison. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Bearss K, Eyberg SM. A test of the parenting alliance theory. Early Education and Development. 1998;9:179–185. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Putnam S, Crnic K. Coparenting, parenting, and early emotional development. New Directions for Child Development. 1996;74:45–55. doi: 10.1002/cd.23219967405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. A secure base: Parent-child attachment and healthy human development. New York: Basic Books; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Flor DL, Neubaum E. Coparenting processes and child competence among rural African American families. In: Lewis M, Feiring C, editors. Families, risk, and competence. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1998. pp. 227–243. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks D, Webster D, Berrick JD, Barth R. An overview of the child welfare system in California: Today's challenges and tomorrow's interventions. Berkeley: University of California, Center for Social Services Research; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Chase-Lansdale PL. Escape from poverty: What makes a difference for children? New York: Cambridge University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Burstein J. Conjugal visits in prison. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Caldera YM, Lindsey EW. Coparenting, mother-infant interaction, and infant-parent attachment in relationships in two-parent families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:275–283. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.2.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catan L. Infants with mothers in prison. In: Shaw R, editor. Prisoner's children. New York: Routledge, Chapman and Hall; 1992. pp. 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Cernkovich SA, Giordano PC. Family relationships and delinquency. Criminology. 1987;25:295–319. [Google Scholar]

- Coley RL, Chase-Lansdale PL. Adolescent pregnancy and parenthood: Recent evidence and future directions. American Psychologist. 1998;53:152–166. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cota-Robles S, Gamble W. Parent-adolescent processes and reduced risk for delinquency: The effect of gender for Mexican American adolescents. Youth and Society. 2006;37:375–392. [Google Scholar]

- Devine K. Family unity: The benefits and costs of community-based sentencing programs for women and their children in Illinois. Chicago: Chicago Legal Advocacy to Incarcerated Mothers; 1997. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- Dowden C, Andrews DA. What works for female offenders: A meta-analytic review. Crime and Delinquency. 1999;45:438–452. [Google Scholar]

- Eddy J, Reid J. The antisocial behavior of the adolescent children of incarcerated parents: A developmental perspective. Paper presented at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services conference on From Prison to Home; Bethesda, Maryland. 2002. Jan, [Google Scholar]

- Enos S. Mothering from the inside: Parenting in a women's prison. Albany: State University of New York Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Farrington DP, Welsh BC. Saving children from a life of crime: Early risk factors and effective interventions. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Lynskey MT. Family change, parental discord, and early offending. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1992;33:1059–1075. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1992.tb00925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman LT. Repeating the cycle of hard living and crime: Wives' accommodations to husbands' parole performance. Federal Probation. 1986;50:44–54. [Google Scholar]

- Frosch CA, Mangelsdorf SC, McHale JL. Marital behavior and the security of preschooler-parent attachment relationships. Journal of Family Psychology. 2000;14:144–161. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.14.1.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabel K, Johnston D. Children of incarcerated parents. New York: Lexington Books; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel B, Bodenmann G. Stress and coping in parents of a child with behavioral problems. Zeitschrift für Klinische Psychologie und Psychotherapie. 2006;35:59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Geen R, Holcolm P, Jantz A, Koralek R, Leos-Urbel J, Malm K. On their own terms: Supporting kinship care outside of TANF and foster care. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Glick RM, Neto VN. National study of women's correctional programs. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Goeke-Morey MC, Cummings EM, Harold GT, Shelton KH. Categories and continua of destructive and constructive marital conflict tactics from the perspective of Welsh and US children. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17:327–338. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman CC, Silverstein M. Grandmothers raising grandchildren. Journal of Family Issues. 2006;27:1605–1626. [Google Scholar]

- Groenendyk AE, Volling BL. Coparenting and early conscience development in the family. Journal of Genetic Psychology. 2007;168:201–224. doi: 10.3200/GNTP.168.2.201-224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grych JH, Fincham FD. Children's appraisals of marital conflict: Initial investigations of the cognitive-contextual framework. Child Development. 1993;64:215–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb02905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haapasalo J, Tremblay RE. Physically aggressive boys from ages 6 to 12: Family background, parenting behavior, and prediction of delinquency. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;6:1044–1052. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.5.1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan J, Simpson J, Gillis AR. Feminist scholarship, relational and instrumental control, and a power-control theory of gender and delinquency. British Journal of Sociology. 1988;39:301–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hairston CF. Family ties during imprisonment: Do they influence future criminal activity? Federal Probation. 1988;52:48–52. [Google Scholar]

- Hairston CF. Family ties during imprisonment: Important for whom and for what? Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare. 1991;18:87–104. [Google Scholar]

- Hairston CF. The state of corrections: Proceedings ACA annual conference. Laurel, MD: American Correctional Association; 1992. Women in jail: Family needs and family supports; pp. 179–184. [Google Scholar]

- Hairston CF. Fathers in prison. In: Gabel K, Johnston D, editors. Children of incarcerated parents. New York: Lexington Books; 1995. pp. 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Hairston CF. Prisoners and their families: Parenting issues during incarceration. In: Travis J, Waul M, editors. Prisoners once removed: The impact of incarceration and reentry on children, families, and communities. Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press; 2003. pp. 259–282. [Google Scholar]

- Harden AW, Clark RL, McGuire K. Informal and formal kinship care. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Herrenkohl T, Farrington DP, Brewer D, Catakabi RF, Harachi TW. A review of predictors of youth violence. In: Loeber R, Farrington D, editors. Serious and violent juvenile offenders: Risk factors and successful interventions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. pp. 106–146. [Google Scholar]

- Henry B, Moffitt T, Robins L, Earls F, Silva P. Early family predictors of child and adolescent antisocial behavior: Who are mothers of delinquents? Criminal Behavior and Mental Health. 1993;3:97–118. [Google Scholar]

- Herrenkohl TI, Hill KG, Hawkins JD, Chung I, Nagin DS. Developmental trajectories of family management and risk for violent behavior in adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39:206–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan DP, Hao L, Parish WL. Race, kin networks, and assistance to mother-headed families. Social Forces. 1990;68:797–812. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter A, Taylor RJ. Grandparenthood in African American families. In: Szinovacz M, editor. Handbook on grandparenthood. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press; 1998. pp. 70–86. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson E, Waldfogel J. Where children live when parents are incarcerated. Joint Center for Poverty Research Policy Briefs. 2003;5 [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Smailes E, Cohen P, Kasen S, Brook JS. Anti-social parental behaviour, problematic parenting and aggressive offspring behavior during adulthood: A 25-year longitudinal investigation. British Journal of Criminology. 2004;44:915–930. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson V. Linking changes in whole family functioning and children's externalizing behavior across the elementary school years. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17:499–509. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.4.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston D. Incarceration of women and effects on parenting. Paper presented at Northwestern University, Institute for Policy Research conference on Effects of Incarceration on Children and Families; Evanston, IL. 2001a. May, [Google Scholar]

- Johnston D. What works for children of prisoners: The “children of criminal offenders in the community” study. Paper presented at the annual conference of International Community Corrections Association; Philadelphia, PA. 2001b. Sep, [Google Scholar]

- Johnston D, Carlin M. When incarcerated parents lose contact with their children. Center for Children of Incarcerated Parents Journal. 2007;6 [Google Scholar]

- Kalil A, Spencer MS, Spieker SJ, Gilchrist LD. Effects of grandmother coresidence and quality of family relationships on depressive symptoms of adolescent mothers. Family Relations. 1998;47:433–441. [Google Scholar]

- Katz L, Low S. Marital violence, co-parenting, and family-level processes in relation to children's adjustment. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;8:372–382. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.2.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazura K. Family programming for incarcerated parents: A needs assessment among inmates. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation. 2001;32:67–83. [Google Scholar]

- Kellam SG, Ensminger ME, Turner RJ. Family structure and the mental health of children: Concurrent and longitudinal community-wide studies. General Psychiatry. 1977;34:1012–1022. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1977.01770210026002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley BT, Loeber R, Keenan K, DeLamatre M. Developmental pathways in boys' disruptive and delinquent behavior (Juvenile Justice Bulletin) Washington, DC: Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 1997. Dec, [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl KM. Family process variables and children's disruptive behavior problems. Journal of Family Psychology. 1998;12:420–436. [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl KM, Malik NM. Marital conflict, family processes, and boys' externalizing behavior in Hispanic American and European American families. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1999;28:12–24. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2801_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey MW, Derzon JH. Predictors of violent or serious delinquency in adolescence and early adulthood: A synthesis of longitudinal research. In: Loeber R, Farrington DP, editors. Serious and violent juvenile offenders: Risk factors and successful interventions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. pp. 86–105. [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Family factors as correlates and predictors of juvenile conduct problems and delinquency. In: Tonry M, Morris N, editors. Crime and justice. Vol. 7. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1986. pp. 209–149. [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Green SM. Age at onset problem behaviour in boys, and later disruptive and delinquent behaviours. Criminal Behavior and Mental Health. 1991;1:229–246. [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE, Mnookin RH. Dividing the child: Social and legal dilemmas of custody. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Martin M. Connected mothers: A follow-up study of incarcerated women and their children. Women and Criminal Justice. 1997;8:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- McConnell M, Kerig P. Assessing coparenting in families of school-age children: Validation of the coparenting and family rating system. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science. 2002;34:4–58. [Google Scholar]

- McHale J. Overt and covert coparenting processes in the family. Family Process. 1997;36:183–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1997.00183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale J. Charting the bumpy road of coparenthood. Washington, DC: Zero to Three Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- McHale J. Shared child-rearing in nuclear, fragile, and kinship family systems: Evolution, dilemmas, and promise of a coparenting framework. In: Schulz M, Pruett M, Kerig P, Parke R, editors. Feathering the nest: Couple relationships, couples interventions and children's development. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; in press. [Google Scholar]

- McHale J, Cowan PA. Understanding how family-level dynamics affect children's development: Studies of two-parent families. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- McHale J, Johnson D, Sinclair R. Family-level dynamics, preschoolers' family representations, and playground adjustment. Early Education and Development. 1999;10:373–401. [Google Scholar]

- McHale J, Khazan I, Erera P, Rotman T, DeCourcey W, McConnell M. Coparenting in diverse family systems. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of parenting: Vol 3: Status and social conditions of parenting. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- McHale J, Kuersten R, Lauretti A. New directions in the study of family-level dynamics during infancy and early childhood. In: McHale JP, Cowan PA, editors. Understanding how family-level dynamics affect children's development: Studies in two-parent families. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1996. pp. 5–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale J, Lauretti A, Talbot J, Pouquette C. Retrospect and prospect in the psychological study of coparenting and family group process. In: McHale J, Grolnick W, editors. Retrospect and prospect in the psychological study of families. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 127–166. [Google Scholar]

- McHale J, Rasmussen J. Coparental and family group-level dynamics during infancy: Early family precursors of child and family functioning during preschool. Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10:39–58. doi: 10.1017/s0954579498001527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale J, Sullivan M. Family systems. In: Hersen M, Gross A, editors. Handbook of clinical psychology: Vol 2 Children and adolescents. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley; 2008. pp. 192–226. [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, Fuller-Thompson E. African American grandparents raising grandchildren: A national study using the census 2000 American community survey. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2005;60:S82–S92. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.2.s82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, Roe K. Grandmothers as caregivers: Raising children of the crack cocaine epidemic. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Minuchin S. Families and family therapy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Myers BJ, Smarsh TM, Amlund-Hagen K, Kennon S. Children of incarcerated mothers. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 1999;8:11–25. [Google Scholar]

- Newberger EH. The men they will become: The nature and nurture of male character. Reading, MA: Perseus Books; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Nurse A. Coming home to strangers: Newly paroled juvenile fathers and their children. Paper presented at Northwestern University, Institute for Policy Research conference on Effects of Incarceration on Children and Families; Evanston, IL. 2001. May, [Google Scholar]

- Nurse A. Fatherhood arrested: Parenting from within the juvenile justice system. Nashville, TN: Van der Bilt University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien P. Just like baking a cake: Women describe the successful ingredients for successful reentry after incarceration. Families in Society. 2001;82:287–295. [Google Scholar]

- Parke R, Clarke-Stewart K. The effects of parental incarceration on children: Perspectives, promises, and policies. In: Travis J, Waul M, editors. Prisoners once removed: The impact of incarceration and reentry on children, families, and communities. Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press; 2003. pp. 189–232. [Google Scholar]

- Petersilia J. When prisoners come home. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips SD, Erkanli A, Keeler GP, Costello EJ, Angold A. Disentangling the risks: Parent criminal justice involvement and children's exposure to family risks. Criminology and Public Policy. 2006;5:677–702. [Google Scholar]

- Pittman LD, Boswell MK. The role of grandparents in the lives of preschoolers growing up in urban poverty. Applied Developmental Science. 2007;11:20–42. [Google Scholar]

- Radosh PF. Reflections on women's crime and mothers in prison: A peacemaking approach. Crime and Delinquency. 2002;48:300–315. [Google Scholar]

- Roy K, Dyson O. Gatekeeping in context: Babymama drama and the involvement of incarcerated fathers. Fathering Journal. 2005;3:289–310. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Laub JH. Urban poverty and the family context of delinquency: A new look at structure and process in a classic study. Child Development. 1994;65:523–540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoppe S, Mangelsdorf S, Frosch C. Coparenting, family process, and family structure: Implications for preschoolers' externalizing behavior problems. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15:526–545. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.3.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seymour C. Children with parents in prison: Child welfare policy, program, and practice issues. Child Welfare. 1998;77:469–493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slaght E. Family and offender treatment focusing on the family in the treatment of substance abusing criminal offenders. Journal of Drug Education. 1999;19:53–62. doi: 10.2190/BHGA-Y0KY-U7FK-UDKX. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A, Krisman K, Strozier A, Marley M. Breaking through the bars: Exploring the experience of addicted incarcerated parents whose children are cared for by relatives. Families in Society. 2004;85:187–195. [Google Scholar]

- Smith CA, Krohn M. Delinquency and family life among male adolescents: The role of ethnicity. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1995;24:69–93. [Google Scholar]

- Smith CA, Stern SB. Delinquency and antisocial behavior: A review of family processes and intervention research. Social Service Review. 1997;71:382–420. [Google Scholar]

- Snell TL. Women in prison: Survey of state prison inmates, 1991. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Stack CB. All our kin: Strategies for survival in a Black community. New York: Harper Torchbooks; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay RE, Pihl RO, Vitaro F, Dobkin PL. Predicting early onset of male antisocial behavior from preschool behavior. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:732–739. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950090064009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. U S Census 2000 supplementary survey (C2SS) 2000 Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/c2ss/www/

- Vaughn B, Egeland B, Sroufe A, Waters E. Individual differences in infant-mother attachment: Stability and change in families under stress. Child Development. 1979;50:971–975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visher CA, Travis J. Transitions from prison to community: Understanding individual pathways. Annual Review of Sociology. 2003;29:89–113. [Google Scholar]

- Waldrop D. Caregiving issues for grandmothers raising their grandchildren. Journal of Human Behavior. 2004;7:201–223. [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman GA, Keenan K, Tremblay RE, Coie JD, Herrenkohl TI, Loeber R, et al. Risk and protective factors of child delinquency (NCJ 193409) Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman GA, Miller L, Pinner E, Jaramillo BS. Parenting predictors of early conduct problems in urban, high-risk boys. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35:1227–1236. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199609000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White JL, Moffitt TE, Earls F, Robins L, Silva PA. How early can we tell?: Predictors of childhood conduct disorder and adolescent delinquency. Criminology. 1990;28:507–533. [Google Scholar]

- Woodrow J. Mothers inside, children outside. In: Shaw R, editor. Prisoner's children. New York: Routledge, Chapman and Hall; 1992. pp. 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Young DS, Smith C. When moms are incarcerated: The needs of the children, mothers, and caregivers. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Human Services. 2000;81:130–147. [Google Scholar]

- Zalba SR. Inmate mothers and their children. In: Bryant CD, Wells JG, editors. Deviancy and the family. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis; 1964. pp. 181–189. [Google Scholar]