SUMMARY

Aim

This study examines the relationship between prenatal cocaine exposure and parent-reported child behavior problems at age 7 years.

Methods

Data are from 407 African-American children (210 cocaine-exposed, 197 non-cocaine-exposed) enrolled prospectively at birth in a longitudinal study on the neurodevelopmental consequences of in utero exposure to cocaine. Prenatal cocaine exposure was assessed at delivery through maternal self-report and bioassays (maternal and infant urine and infant meconium). The Achenbach Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), a measure of childhood externalizing and internalizing behavior problems, was completed by the child’s current primary caregiver during an assessment visit scheduled when the child was seven years old.

Results

Structural equation and GLM/GEE models disclosed no association linking prenatal cocaine exposure status or level of cocaine exposure to child behavior (CBCL Externalizing and Internalizing scores or the eight CBCL sub-scale scores).

Conclusions

This evidence, based on standardized ratings by the current primary caregiver, fails to support hypothesized cocaine-associated behavioral problems in school-aged children with in utero cocaine exposure. A next step in this line of research is to secure standardized ratings from other informants (e.g., teachers, youth self-report).

Keywords: cocaine, prenatal exposure, child behavior

INTRODUCTION

The European Community has witnessed a marked increase in cocaine consumption over the last decade, although occurrence of cocaine use has not yet reached levels seen in the United States. It is estimated that there are over 3 million cocaine users in Europe, with cocaine use concentrated heavily in the western regions. Spain and Ireland have the highest rates of cocaine use among the general population with annual prevalence estimates of 2.6% and 2.4%, respectively (UNODC, 2004). According to the 2002/2003 British Crime Survey, approximately 2.1% of the United Kingdom population used cocaine in the last year (Condon & Smith, 2003). Although rates of cocaine use in Italy are lower (e.g., 1.1% in past year), data from several sources suggest cocaine use is on the rise here as well (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, 2003). The climb in cocaine consumption is most evident among adolescents and young adults. For example, among 15-16-year-old Italian students, lifetime prevalence rates rose from 1.9% in 2000 to 3.5% in 2001 (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, 2003). In addition, during the year 2000, roughly 10% of 15-34 year olds in the United Kingdom had used cocaine as compared to 3-4% in 1994. Similarly, 4-5% in this age group were recent cocaine users in 2000–a five-fold increase since 1994 (Haasen et al., 2004). Because some of these young cocaine users are women of childbearing age, one might expect corresponding increases in the number of infants exposed in utero to cocaine each year.

Maternal cocaine use during pregnancy and the possibility of cocaine’s impact on the developing fetus and young child has been a major public health concern in the United States for the last two decades. Consequently, numerous studies have examined the relationship between in utero cocaine exposure and aspects of infant and child functioning. In the short term, prenatal cocaine exposure has been linked to adverse obstetric and perinatal outcomes including spontaneous abortion, abruptio placentae, and decreased fetal growth, as well as early infant neurobehavioral abnormalities (Bandstra et al., 2001a; Dombrowski et al., 1991; Morrow et al., 2001; Singer et al., 1994). Evidence about long-term consequences of prenatal cocaine exposure remains inconclusive, mainly because few controlled studies have followed cocaine-exposed and non-exposed children into the school-age years. What is apparent in the available body of evidence is that the impact of in utero cocaine exposure is more subtle and variable than initially believed. In most (but not all) studies, global problem-solving and intellectual functioning seem to be spared (Azuma & Chasnoff, 1993; Hurt et al., 1997; Nelson et al., 2004; Nulman et al., 2001; Phelps & Cottone, 1999). Several studies of in utero cocaine exposure have produced evidence consistent with cocaine-associated deficits in specialized areas of functioning such as attention, language, visual-motor integration, and motor performance (Bandstra et al., 2001b; Bender et al., 1995; Johnson et al., 1997; Mayes et al., 2003; Mentis & Lundgren, 1995; Nulman et al., 2001; Richardson et al., 1996). Research to date, with some limitations, seems to support regulatory deficits in children exposed prenatally to cocaine. Tester ratings of child behavior in the clinic setting have indicated greater restlessness and distractibility in exposed children compared to non-exposed children (Richardson, 1998), and cocaine-exposed children have performed more poorly on laboratory measures of impulsivity and inattention (e.g., delay task, continuous performance test) compared to controls (Bandstra et al., 2001b; Bendersky & Lewis, 1998; Richardson et al., 1996). Preliminary evidence also suggests possible cocaine-associated deficits in neuropsychological functioning (Espy et al., 1999). Teacher ratings of classroom behavior have indicated greater behavioral difficulties among cocaine-exposed children (Delaney-Black et al., 1998; 2004), and some, but not all, studies have found greater externalizing and/or internalizing behavior problems on parent-report measures such as the Child Behavior Checklist in relation to prenatal cocaine exposure (Bennett et al., 2002; Chasnoff et al., 1998; Hawley et al., 1995; Phelps et al., 1997; Richardson, 1998).

Evidence from pre-clinical neuropsychopharmacological and neurodevelopmental experiments lends plausibility to the hypothesis that prenatal cocaine exposure might have causal linkages to later arousal dysregulation, with manifestations including disturbances of behavior and emotion, deficits in attention and executive functioning, and altered stress reactivity. Noting the pervasive effects of in utero cocaine exposure on monoaminergic neuro-transmitter tracts of the central nervous system (CNS), investigators (Mayes, 1999; 2002; Volpe, 1992) have advanced a developmental hypothesis, expressed here by Mayes (1999): “Because of their trophic role in CNS ontogeny, cocaine effects on [the] developing nervous system may be mediated in part through effects on monoamine system ontogeny. In turn, these effects may be expressed behaviorally in disrupted patterns of arousal and attention regulation given that these domains are connected intimately to monoaminergic systems.” Moreover, the idea has emerged that these disruptions and disturbances in cocaine-exposed children may be more apparent under stressful environmental conditions, for example, as these children increase in maturity and face the challenges of the primary school environment (Mayes et al., 1998; Mayes, 2002).

In our research group’s previous report from the Miami Prenatal Cocaine Study (MPCS), 140 five-year-old children who had been exposed in utero to cocaine were compared with 120 matched non-exposed children in terms of dysregulation as might be manifest in externalizing and internalizing behavior problems on the Achenbach’s Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), rated by the biological mother. Based upon CBCL global scores taken at age five years, there were no differences on the Externalizing behavior score or the Internalizing behavior score in relation to prenatal cocaine exposure, despite adequate sample size and statistical power to detect quite modest differences (Accornero et al., 2002).

This report extends our prior research by examining the potential relationship between prenatal cocaine exposure and dysregulation in school-aged children (i.e., at age seven years), with a focus upon CBCL scores rated by the child’s current primary caregiver (biological mother or other relative/non-relative caregiver). The primary objective is to examine whether cocaine-associated externalizing and/or internalizing disturbances might become manifest once the children are challenged by increased social and academic task demands associated with entry into primary school. In addition, the possible influence of level of cocaine exposure on the externalizing and internalizing disturbances observed at age seven years is investigated, and the relationship between prenatal cocaine exposure and specific types of behavior problems (i.e., subfacets of the externalizing and internalizing global scores) is explored. The approach includes structural equation modelling, as well as an application of multivariate marginal models (SEM) based upon a generalized estimating equations approach.

METHOD

As described in detail elsewhere (Bandstra et al., 2001a), the Miami Prenatal Cocaine Study was designed as a multi-wave longitudinal study focused on the neurodevelopmental outcome of children exposed in utero to cocaine. Study protocol and informed consent procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board and conducted under a federal Department of Health and Human Services Certificate of Confidentiality. The description provided here is a brief summary of the study’s materials and methods.

PARTICIPANTS

The original study sample of 476 mothers and children was enrolled prospectively at birth, recruited from a larger epidemiological survey sample of 1,505 African-American women residing in pre-selected inner-city, low-income neighbourhoods and delivering full-term infants at a large university-affiliated teaching hospital between November 1990 and July 1993. To be included in the study, the mothers had to identify themselves as United States-born and of African-American ethnicity. These and other study design constraints (e.g., English-speaking, residence within inner-city neighbourhoods) helped to increase the homogeneity of the sample and to reduce confounding by characteristics that otherwise might vary across cocaine-exposed and non-exposed groups. In addition, so as to constrain confounding due to co-morbid conditions and other drug exposures, the following exclusion criteria were imposed: maternal HIV infection, major congenital malformations, disseminated congenital infection, and prenatal exposure to opioids (including methadone), amphetamines, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, or phencyclidine. Prenatal cocaine exposure was determined by maternal self-report of cocaine use during pregnancy and/or via at least one positive bioassay (maternal urine, infant urine, meconium). The resulting baseline sample of 476 newborns included 253 with evidence of prenatal cocaine exposure and varying degrees of prenatal alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana exposure and 223 with no evidence of cocaine exposure (147 drug free and 76 with varying degrees of prenatal alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana use).

The analysis sample for this study consists of 407 children (210 with prenatal cocaine exposure, and 197 without) participating in the 7-year follow-up assessment. Explanations for missingness at age seven were as follows: 2 infants had died; 32 moved out of area, too far to assess by interview at the study clinic; 11 declined 7-year assessment; and 16 were lost to follow-up. Another 8 children attended the visit but had incomplete behavioral data (e.g., primary caregiver unavailable for interview); these 69 children have not been included in these analyses. There was no differential attrition across study groups. Comparison of enrollment characteristics of participants and non-participants of the 7-year assessment revealed no group differences at alpha = 0.05. Descriptive information on the 407 participants within this study’s analysis sample is presented in table I.

Table I.

Sample characteristics at birth (n=407).

| Cocaine-exposed (n=210) | Non-cocaine-exposed (n=197) | |

|---|---|---|

| Infant | ||

| Birth weight (grams)* | 2952 (471) | 3302 (510) |

| Birth length (cm)* | 48.8 (2.5) | 50.8 (2.3) |

| Birth head circumference (cm)* | 33.0 (1.6) | 33.8 (1.5) |

| Gestational age (weeks)* | 39.3 (1.3) | 39.7 (1.4) |

| Male | 51.0% | 50.8% |

| Mother | ||

| Age* | 28.9 (4.8) | 23.8 (5.4) |

| Education (years) | 11.1 (1.4) | 11.3 (1.4) |

| Employed* | 5.2% | 16.8% |

| Never married | 91.0% | 87.8% |

| Prenatal care (≥ visits)* | 68.1% | 84.3% |

| Primigravida* | 6.2% | 23.4% |

Numbers represent means (S.D.) or percentages where indicated.

p <0.01

PROCEDURES

Whereas participants are enrolled in an intensive longitudinal follow-up investigation with multiple repeated measures, the current study focuses on assessments taken at the time of delivery (i.e., indicators of prenatal drug exposure and maternal and infant characteristics) and measures collected by trained research staff during the child’s seventh year (i.e., basic psychosocial information about the child and family, assessments of internalizing and externalizing behavior) as part of a comprehensive follow-up assessment at the study clinic.

The primary response variables for the present investigation are global and specific facets of externalizing behavior and internalizing behavior, interpreted here as a manifestation of dysregulation. The Achenbach Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach, 1991) was completed by the child’s primary caregiver, typically the biological mother, at the time of the 7-year follow-up study visit. The CBCL is a 113-item standardized parent-report measure of behavior problems in children, with norms available for ages 4-18 years. The measure yields scores for eight sub-scales, which were termed ‘facets’ for multivariate analysis (Withdrawn, Somatic Complaints, Anxious/Depressed, Social Problems, Thought Problems, Attention Problems, Delinquent Behavior, and Aggressive Behavior); the two primary CBCL global summary scales, the Externalizing and Internalizing scores, were also analyzed. For the facet and global scales, larger scores indicate higher levels of problems.

With respect to covariates, birth weight was obtained immediately after delivery by the nursing staff of the admission nursery. Trained research nurses, blinded to exposure status, performed the Ballard gestational age assessment within 36 hours of delivery, and obtained occipital-frontal head circumference and recumbent crown-heel birth length. During the immediate postpartum period, experienced research staff performed a standardized research interview with the mother and organized the collection of biological specimens for analysis. The interview included detailed standardized interview assessments of the mother’s drug use history, including questions on drug use during and before pregnancy (e.g., number of weeks used, usual days/weeks, and usual dose/day). In addition, pertinent maternal and infant demographic and medical information were abstracted from the medical chart.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

In order to estimate relationships between prenatal cocaine exposure and subsequent levels of internalizing and externalizing behavior problems, a structural equation model was implemented using Mplus software (Muthén & Muthén, 2004). This multivariate approach permitted simultaneous estimation of regression slopes that link prenatal cocaine exposure, measured at delivery, with the two primary global scale scores measured at age 7 years (CBCL Externalizing and Internalizing raw scores). Because this study sample is demographically different from the CBCL sample used to derive the standard normed T-score values, raw scores from the Externalizing and Internalizing domains were used in analyses, with covariate adjustment for child’s sex and age in months.

After standard Tukey-style exploratory steps (e.g., box-whisker plots), an initial multivariate analysis/estimation model was fit to the data. In this model, the presence/absence of prenatal cocaine use was summarized via a single binary (0/1) indicator, with the value of 1 encoding any positive maternal self-report and/or any one or more cocaine-positive bioassay indicators. The two global Externalizing and Internalizing scores measured at age seven years were regressed simultaneously on the binary indicator for prenatal cocaine exposure status and on a set of covariates that included terms coded to reflect levels of alcohol, tobacco, or marijuana use during the pregnancy, as reported by the mother in the hours after delivery. Terms for child sex and age (in months) at the time of the assessment were included as covariates in all models. In these and all other analyses, the focus was on estimation of the magnitude of relationships or hypothesized influences and their 95% confidence intervals; p-values are presented as an aid to readers who wish to gauge the estimated slopes in relation to departures from the null value.

After fitting the initial model with a binary indicator for prenatal cocaine exposure, a similar multivariate model was re-specified with prenatal cocaine exposure expressed as a summary latent construct manifest in the values of two sub-constructs with multiple indicators. One sub-construct was formed via exploratory latent trait analysis of the four interdependent bioassay indicators of prenatal cocaine exposure (maternal urine, infant urine, qualitative assay of infant meconium, quantitative assay of infant meconium). In addition, there was a second sub-construct with separate discrete indicators for each of the three trimesters of pregnancy, pre-coded (before any analysis) to discriminate mothers in relation to tertiles of the frequency of her cocaine use during that trimester (e.g., 0= no self-reported cocaine/crack use; 1= 1-24 uses; 2= 25-180+ uses). These self-report and bioassay sub-constructs were then combined into a single summary latent variable that placed each infant on a single dimension to reflect ‘level of prenatal cocaine exposure,’ as manifest in the bioassay-determined latent construct and in the trimester-specific indicators of cocaine exposure, and the two indicators of externalizing and internalizing difficulties were regressed upon this latent construct within the SEM framework.

Thereafter, a multivariate response profile analysis, developed by Liang & Zeger (1986) as an extension of the General Linear Model and Generalized Estimating Equations (GLM/GEE), was used in order to study possible links from prenatal cocaine exposure to eight specific facets of behavior problems (CBCL subscale scores). In brief, the multivariate GLM/GEE analysis takes the interdependencies of the eight facets into account and yields a ‘common slope estimate,’ which borrows strength across all subscales, based on the parsimonious assumption that the size of the cocaine-associated difference in subscale scores is roughly equivalent across all eight facets of behavior problems. Then, the modelling process is extended to test the assumption that the common slope estimate provides an adequate summary of the cocaine association with each facet. That is, this form of multivariate analysis provides simultaneous estimation of the effects of prenatal cocaine on the eight CBCL subscale scores, with consideration for the interrelationships among these measures. While similar to the well-known MANOVA, the GEE approach offers a number of advantages. For example, the GLM/GEE model utilizes all available data, even if some subjects have missing response values, and does not impose compound symmetry assumptions. For this analysis, z-transformed raw scores for the eight facet-specific subscales were used, as recommended in the CBCL manual in order to promote dispersion across the full range of subscale values (Achenbach, 1991); accordingly, covariate terms for age (in months) and sex were entered into these models. Under the GLM/GEE framework as implemented via the Stata Version 8.2 software (Statacorp, 2003), this model was specified with ‘robust’ estimation for relaxation of the more stringent ANOVA compound symmetry assumption.

RESULTS

Table II describes the study sample of 407 mother-child pairs in relation to maternal and infant characteristics at delivery. As shown here, cocaine-exposed infants had slightly shorter mean length of gestation and were smaller at birth compared to non-exposed infants. Additionally, mothers who used cocaine during pregnancy were older and were more likely to be unemployed, to have received inadequate prenatal care, and to have had previous pregnancies. Table II summarizes self-reported rates and median amounts of alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, and cocaine use during pregnancy. Mothers who used cocaine during pregnancy were more likely to report alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana use. A higher level of tobacco use was also observed in the cocaine group compared to the non-cocaine group. To accommodate these differences, covariate terms for these drugs were included in the multivariate models described below.

Table II.

Maternal self-reported drug use during pregnancy (n=407).

| Cocaine-exposed (n=210) | Non-cocaine-exposed (n=197) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug | Median (Min, Max) a | % (n) | Median (Min, Max) a | % (n) |

| Alcohol (# drinks) c | 99 (1, 5226) | 66.2 (139) | 57 (2, 1680) | 29.4 (58) |

| Tobacco (# cigarettes) bc | 2156 (1, 8820) | 76.7 (161) | 1043 (21, 5880) | 15.2 (30) |

| Marijuana (# joints) c | 30 (1, 1229) | 45.7 (96) | 32 (1, 807) | 11.7 (23) |

| Cocaine/crack (# lines/rocks) | 140 (1, 19320) | 68.6 (144) | ||

Maternal drug use is expressed as median (min/max) due to skewed distributions. Median values based only on mothers reporting usage, calculated using total exposure composites [(number of weeks used) x (usual number of days per week) x (usual dose per day)].

p <0.05, between group comparisons of median self-reported maternal drug use.

p <0.01, between group comparisons of percentage of mothers reporting drug use.

There were also demographic differences at the 7-year follow-up, as shown in table III. Children in the cocaine-exposed group experienced a greater number of changes in primary caregiver since birth and were less likely to be in the primary care of the biological mother at the time of the 7-year assessment. Moreover, primary caregivers of the cocaine-exposed children were older, more likely to have been married in their lifetime, more likely to be unemployed, and slightly less well educated than those in the non-exposed group. Table IV presents means for the CBCL summary and subscale scores and shows the percentage of children scoring in the clinically significant range by group status. Mean CBCL T-scores were in the non-clinical range and generally comparable for the two groups.

Table III.

Sample characteristics at 7-year follow-up visit (n=407).

| Cocaine-exposed (n=210) | Non-cocaine-exposed (n=197) | |

|---|---|---|

| Child | ||

| Age (months) | 88.6 (4.0) | 88.7 (4.2) |

| Full-scale IQ c | 81.9 (13.3) | 83.0 (13.7) |

| Received special services d | 30.6% | 30.3% |

| Caregiver changes (#) b | 0.69 (1.1) | 0.33 (0.87) |

| Biological mother as caregiver b, e | 58.9% | 95.9% |

| Caregiver | ||

| Age b | 41.4 (10.7) | 31.7 (6.5) |

| Education (years) a | 11.2 (2.0) | 11.7 (1.5) |

| Employed b | 43.3% | 71.6% |

| Never married a | 46.9% | 58.1% |

Numbers represent means (S.D.) or percentages where indicated.

p <0.05;

p <0.01

Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Third Edition (WISC-III), Short Form.

Received any physical therapy, speech/language therapy, formal educational interventions, or psychological/psychiatric services in the past 12 months.

The biological mother is one of the child’s current primary caregivers.

Table IV.

Caregiver-Report Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) scores at age 7 years

| Cocaine-exposed (n=210) | Non-cocaine-exposed (n=197) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD)a | Clinical Rangeb | Mean (SD)a | Clinical Rangeb | |

| CBCL Summary Scales | ||||

| Internalizing | 46.2 (10.1) | 12.0% | 46.5 (9.1) | 8.1% |

| Externalizing | 50.7 (11.8) | 23.4% | 50.5 (11.3) | 19.3% |

| Total Problems | 49.4 (11.6) | 19.1% | 49.3 (10.6) | 15.7% |

| CBCL Subscales | ||||

| Withdrawn | 53.7 (6.0) | 5.7% | 54.0 (6.1) | 4.1% |

| Somatic Problems | 52.1 (4.1) | 1.4% | 52.1 (4.2) | 1.5% |

| Anxious/Depressed | 52.5 (5.4) | 2.4% | 51.9 (4.3) | 1.0% |

| Social Problems | 54.5 (6.7) | 8.1% | 54.1 (6.4) | 5.6% |

| Thought Problems | 53.1 (6.0) | 6.7% | 52.9 (6.5) | 3.6% |

| Attention Problems | 55.6 (8.1) | 11.4% | 54.7 (7.8) | 10.7% |

| Delinquent Behavior | 55.4 (7.3) | 13.3% | 55.5 (7.0) | 13.2% |

| Aggressive Behavior | 55.2 (8.3) | 10.9% | 54.8 (8.7) | 9.6% |

T-scores

Percentage of children scoring in the clinical range using a T-score of ≥ 60 for summary scales and T-score ≥ 67 for subscales.

Under the Mplus SEM estimation model, maternal use of cocaine during pregnancy, expressed in binary (0/1) form, was not associated with dysregulation at age seven years, as measured via the CBCL global Externalizing score (ß = -1.1; 95% confidence interval, CI = -3.0, 0.8; p = 0.28) and Internalizing score (ß = 0.4; 95% CI = -0.6, 1.4; p = 0.49), which were allowed to be intercorrelated within this multivariate response analysis. Interestingly, prenatal tobacco exposure, entered into analyses as a covariate, was related to greater levels of externalizing (ß = 0.09; 95% CI = 0.03, 0.14; p = 0.004), but not with internalizing problems (p>0.05). For each unit increase in tobacco exposure during pregnancy (i.e., equivalent to 100 cigarettes), there was an estimated 0.09 point increase in level of externalizing symptoms. No statistically robust associations were observed between prenatal marijuana exposure or prenatal alcohol exposure and the two global externalizing and internalizing constructs (p>0.05).

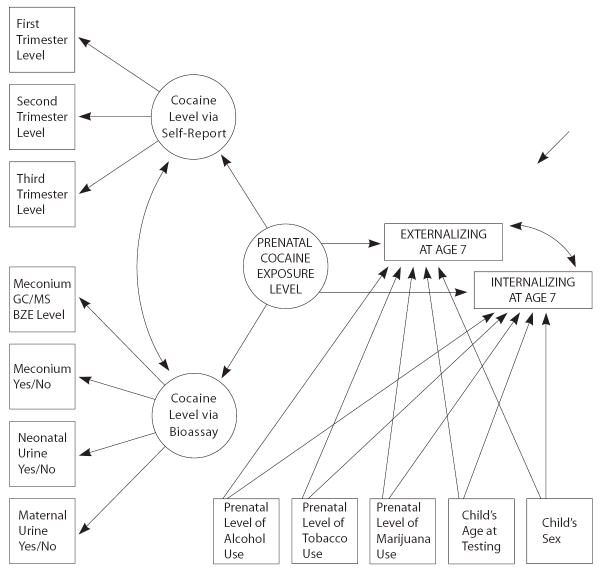

Figure 1 depicts the extension of this initial model to accommodate ‘level’ of prenatal cocaine exposure as a dimensional construct and shows the multiple indicator approach of the model. Under this model, there was also no tangible link from level of prenatal cocaine exposure and dysregulation seven years after birth. The confidence intervals and p-values for the cocaine slope estimates were large, indicating little evidence in support of cocaine-associated externalizing behavior problems (ß = -0.5; 95% CI = -1.5, 0.5; p = 0.31) or cocaine-associated internalizing symptoms at that age (ß = 0.03; 95% CI = -0.4, 0.5; p = 0.88). Similarly, null estimates were observed for levels of maternal marijuana and alcohol use during pregnancy. However, consistent with findings from the initial model, the level of prenatal tobacco use was associated with greater levels of externalizing difficulties at age 7 years (ß = 0.07; 95% CI = 0.03, 0.12; p = 0.002), but not with internalizing problems (p>0.05).

Figure 1.

Estimated effect of prenatal cocaine exposure level on Externalizing and Internalizing problems at age 7 Years

GLM/GEE multivariate response analysis was then used in an exploratory probing for underlying facets of externalizing and internalizing problems that might be differentially influenced by prenatal cocaine exposure. The resulting ‘common slope’ estimates indicated no cocaine-associated difference across the eight facets of behavior problems at age 7 years, with or without statistical adjustments for age and sex (p=0.71 and p=0.74, before and after covariate adjustment, respectively). Extending this multivariate analysis to derive an estimated cocaine-associated effect with respect to each specific facet, again, no apparent cocaine-associated difference was found between cocaine-exposed and non-exposed children at age seven years. Whether boys and girls are combined into a single analysis (see table V), or separated for sex-specific analyses (data not shown in a table), there is no evidence to support a cocaine-associated dysregulation, as manifest in internalizing or externalizing behavior problems as reported on the parent version of the Achenbach CBCL administered to the mother or primary caregiver seven years after the child’s birth (all p>0.05). The non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test based on rank-ordering of the CBCL subscale scores was used as a check on the multivariate GLM/GEE model-based summaries. Results from these univariate K-W tests were consistent with results from the multivariate GLM/GEE models. Namely, there were no cocaine-associated differences of note. The smallest p-value from the eight K-W tests exceeded 0.25.

Table V.

Multivariate contrast of CBCL subscales for cocaine and non-cocaine-exposed children.

| Cocaine-exposed (n=210) | Non-cocaine-exposed (n=197) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBCL Subscales | Estimated Level | 95% CI | Estimated Level | 95% CI | P Value* |

| Withdrawn | -0.16 | -0.30, -0.02 | -0.10 | -0.24, 0.05 | .532 |

| Somatic Problems | -0.14 | -0.29, 0.01 | -0.12 | -0.28, 0.05 | .819 |

| Anxious/Depressed | -0.09 | -0.25, 0.07 | -0.17 | -0.31, -0.04 | .397 |

| Social Problems | -0.10 | -0.25, 0.05 | -0.16 | -0,31, -0.01 | .533 |

| Thought Problems | -0.12 | -0.24, -0.003 | -0.14 | -0.29, 0.02 | .900 |

| Attention Problems | -0.08 | -0.22, 0.07 | -0.19 | -0.33, -0.05 | .248 |

| Delinquent Behavior | -0.14 | -0.28, 0.004 | -0.12 | -0.26, 0.02 | .833 |

| Aggressive Behavior | -0.11 | -0.25, 0.03 | -0.15 | -0.30, -0.01 | .625 |

Comparison of estimated levels for each CBCL subscale between cocaine-exposed and non-cocaine-exposed children.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to examine the hypothesized causal link between prenatal cocaine exposure and later behavioral or emotional dysregulation during a developmental period when children face increasing challenges such as the social task demands of primary school. Contrary to the hypothesis, seven years after birth, neither global externalizing nor internalizing behavior problems were found to depend upon levels of maternal cocaine use during pregnancy. In addition, none of the eight facets of dysregulation, as manifest in the individual CBCL sub-scale scores, was related to in utero cocaine exposure, even when examined separately for boys and girls. These results support findings from another published report with respect to absence of cocaine-associated elevations in parent-rated behavior problems at age 5 (Accornero et al., 2002), as well as evidence from other research teams (Bennett et al., 2002; Frank et al., 2001; Phelps et al., 1997). Nevertheless, as noted in the introduction to this article, theory and a substantial body of evidence from both animal and human studies suggest that prenatal cocaine exposure should affect arousal regulation which may manifest in a variety of behavioral and emotional difficulties, particularly as the developing child is exposed to increasing loads of environmental stressors (e.g., as those faced upon entry into primary school). In this regard, it is important to note that some other studies have found evidence linking prenatal cocaine exposure to parent-rated externalizing and internalizing difficulties among children ages 3-6 years old (Chasnoff et al., 1998; Griffith et al., 1994; Hawley et al., 1995; Richardson, 1998). Moreover, Delaney-Black et al. (2004) recently reported that a measure of sustained cocaine use during pregnancy (i.e., positive maternal and/or infant urine at delivery) is related to teacher ratings of problem behaviors in 6-to 7-year old boys; the apparent cocaine-associated difference was not found for cocaine-exposed girls.

Strengths (e.g., attention to bioassays of cocaine exposure as opposed to exclusive reliance upon maternal self-report of cocaine use during pregnancy) and limitations of the longitudinal study have been summarized previously (Bandstra et al., 2001a). The most noteworthy limitation of the present study is its reliance upon the report of the primary caregivers, some of whom are drug users or have a history of drug use. On one hand, reliance on primary caregiver’s report can be viewed as a potential strength. The primary caregiver is frequently the person most familiar with the child’s behavior, observing him/her in a variety of situations and over extended periods of time. In addition, primary caregivers often are recipients of complaints about the child’s behavior that come from multiple sources: other caregivers and relatives, teachers or day care providers, adults outside of the family and school (e.g., neighbours, church or club leaders), as well as the child’s peers and siblings. On the other hand, the primary caregiver might try to ‘fake good’ on behalf of the child, ignore or suppress evidence of emotional or behavioral difficulties during assessments, or might even under certain circumstances exaggerate the problem behaviors of their children (Chilcoat & Breslau, 1997; Merydith et al., 2003; Youngstrom et al., 1999). To address this issue, future work should include measurements of the youth’s behavioral and emotional dysregulation from multiple perspectives, including the perspective of the teacher and the adolescent him/herself, as well as standardized behavioral ratings made by trained research staff.

Notwithstanding limitations such as reliance upon CBCL ratings by the primary caregiver, a somewhat unexpected finding, at least in this context, was the estimated dependence of global externalizing behavior problems upon one of the key covariates, i.e., the level of prenatal tobacco smoking by the mother. Slotkin (1998) has presented compelling pre-clinical evidence of the direct neurotoxic effects of fetal nicotine exposure, and several studies have linked maternal smoking during pregnancy and later childhood behavior difficulties including conduct problems, hy-peractivity, impulsivity and inattention (Fried et al., 1992; Kotimaa et al., 2003; Orlebeke et al., 1999; Wakschlag et al., 1997). The relationship between prenatal tobacco exposure and neurodevelopmental outcome, however, is complex. The framework of this study, specifically focused on prenatal cocaine exposure, cannot provide definitive evidence regarding the effect of tobacco exposure. For example, the majority of the mothers who smoke tobacco during pregnancy continue to smoke thereafter (Colman & Joyce, 2003), and environmental exposure to tobacco smoke may result in lasting neurodevelopmental complications (Eskenazi & Trupin, 1995). Hence, persistent second-hand exposure to tobacco smoke is a time-varying and potentially confounding covariate of importance in any follow-up study of child development in relation to prenatal tobacco exposure. Unless observational studies are designed with careful consideration of such factors, it is difficult to secure definitive evidence of prenatal tobacco exposure and subsequent neurodevelopmental adverse effects during childhood and adolescence. The current study’s observed link between the covariate term for prenatal tobacco exposure and later behavioral dysregulation should nevertheless evoke curiosity and promote new research.

Given the recent rise in cocaine use in Europe, the impact of prenatal cocaine exposure on infant and child development may be of increasing scientific interest and clinical importance in the European community. The results of this study do not support the hypothesized impact of prenatal cocaine exposure on behavioral and emotional dysregulation during the school-entry years, at least as viewed from the perspective of the mother or other primary care-giver. This evidence is important, but a firm conclusion must await completion of investigations that take a multi-informant approach, with information drawn from among youth, teachers, and others (Chilcoat & Breslau, 1997).

Acknowledgments

Declaration of Interest: This research was conducted in the context of an ongoing longitudinal study funded by the National Institutes of Health National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 DA 06556). Support was also provided by a NIDA career development award (K01 DA 16720), a NIDA research training award (T32 DA 07292), the General Clinical Research Center (M01 RR 16587), and the Health Foundation of South Florida.

References

- Accornero VH, Morrow CE, Bandstra ES, Johnson AL, Anthony JC. Behavioral outcome of preschoolers exposed prenatally to cocaine: Role of maternal behavioral health. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2002;27:259–269. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.3.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4-18 & 1991 Profile. University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; Burlington: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Azuma SD, Chasnoff IJ. Outcome of children prenatally exposed to cocaine and other drugs: A path analysis of three-year data. Pediatrics. 1993;92:396–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandstra ES, Morrow CE, Anthony JC, Churchill SS, Chitwood DD, Steele BM, Ofir AY, Xue L. Intrauterine growth of full-term infants: Impact of prenatal cocaine exposure. Pediatrics. 2001a;108:1309–1319. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.6.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandstra ES, Morrow CE, Anthony JC, Accornero VH, Fried PA. Longitudinal investigation of task persistence and sustained attention in children with prenatal cocaine exposure. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 2001b;23:545–559. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(01)00181-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender SL, Word CO, DiClemente RJ, Crittenden MR, Persaud NA, Ponton LE. The developmental implications of prenatal and/or postnatal crack cocaine exposure in preschool children: A preliminary report. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 1995;16:418–424. doi: 10.1097/00004703-199512000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendersky M, Lewis M. Prenatal cocaine exposure and impulse control at two years. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1998;846:365–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DS, Bendersky M, Lewis M. Children’s intellectual and emotional-behavioral adjustment at 4 years as a function of cocaine exposure, maternal characteristics, and environmental risk. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:648–658. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.5.648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chasnoff IJ, Anson A, Hatcher RP, Stenson H, Iaukea K, Randolph LA. Prenatal exposure to cocaine and other drugs: Outcome at four to six years. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1998;846:314–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilcoat HD, Breslau N. Does psychiatric history bias mothers’ reports? An application of a new analytic approach. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:971–979. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colman GJ, Joyce T. Trends in smoking before, during, and after pregnancy in ten States. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2003;24:29–35. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00574-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condon J, Smith N. Prevalence of Drug Use: Key Findings from the 2002/2003 British Crime Survey.Home Office Research Findings No 229. Home Office; London: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Delaney-Black V, Covington C, Templin T, Ager JW, Martier SS, Sokol RJ. Prenatal cocaine exposure and child behavior. Pediatrics. 1998;102:945–950. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.4.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney-Black V, Covington C, Nordstrom B, Ager J, Janisse J, Hannigan JH, Chiodo L, Sokol RJ. Prenatal cocaine: Quantity of exposure and gender moderation. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2004;25:254–263. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200408000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dombrowski MP, Wolfe HM, Welch RA, Evans MI. Cocaine abuse is associated with abruptio placentae and decreased birth weight, but not shorter labor. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1991;77:139–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskenazi B, Trupin LS. Passive and active maternal smoking during pregnancy, as measured by serum cotinine, and postnatal smoke exposure: 2. Effect on neurodevelopment at age 5 years. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1995;142:S19–S29. doi: 10.1093/aje/142.supplement_9.s19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espy KA, Kaufmann P, Glisky M. Neuropsychologic function in toddlers exposed to cocaine in utero: A preliminary study. Developmental Neuropsychology. 1999;15:447–460. [Google Scholar]

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. The state of the drug problem in the European Union and Norway. Annual Report 2003. 2003 Retrieved 9-2-2005, from http://annualreport.emcd-da.eu.int/en/home-en.html.

- Frank DA, Augustyn M, Knight WG, Pell T, Zuckerman B. Growth, development, and behavior in early childhood following prenatal cocaine exposure: A systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;285:1613–1625. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.12.1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried PA, Watkinson B, Gray R. A follow-up study of attentional behavior in 6-year-old children exposed prenatally to marijuana, cigarettes, and alcohol. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 1992;14:299–311. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(92)90036-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith DR, Azuma SD, Chasnoff IJ. Three-year outcome of children exposed prenatally to drugs. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1994;33:20–27. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199401000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haasen C, Prinzleve M, Zurhold H, Rehm J, Guttinger F, Fischer G, Jagsch R, Olsson B, Ekendahl M, Verster A, Camposeragna A, Pezous AM, Gossop M, Manning V, Cox G, Ryder N, Gerevich J, Bacskai E, Casas M, Matali JL, Krausz M. Cocaine use in Europe - a multi-centre study. Methodology and prevalence estimates. European Addiction Research. 2004;10:139–146. doi: 10.1159/000079834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley TL, Halle TG, Drasin RE, Thomas NG. Children of addicted mothers: Effects of the ‘crack epidemic’ on the caregiving environment and the development of preschoolers. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1995;65:364–379. doi: 10.1037/h0079693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurt H, Malmud E, Betancourt LM, Brodsky NL, Giannetta JM. A prospective evaluation of early language development in children with in utero cocaine exposure and in control subjects. Journal of Pediatrics. 1997;130:310–312. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(97)70361-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JM, Seikel JA, Madison CL, Foose SM, Rinard KD. Standardized test performance of children with a history of prenatal exposure to multiple drugs/cocaine. Journal of Communication Disorders. 1997;30:45–72. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9924(96)00055-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotimaa AJ, Moilanen I, Taanila A, Ebeling F, Smalley SL, McGough JJ, Hartikainen AL, Jarvelin MR. Maternal smoking and hyperactivity in 8-year-old children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42:826–833. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000046866.56865.A2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Mayes LC. Developing brain and in utero cocaine exposure: Effects on neural ontogeny. Development and Psychopathology. 1999;11:685–714. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayes LC. A behavioral teratogenic model of the impact of prenatal cocaine exposure on arousal regulatory systems. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 2002;24:385–395. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(02)00200-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayes LC, Grillon C, Granger R, Schottenfeld RS. Regulation of arousal and attention in preschool children exposed to cocaine prenatally. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1998;846:126–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayes LC, Cicchetti D, Acharyya S, Zhang H. Developmental trajectories of cocaine-and-other-drug-exposed and non-cocaine-exposed children. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2003;24:323–335. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200310000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mentis M, Lundgren K. Effects of prenatal exposure to cocaine and associated risk factors on language development. Journal of Speech & Hearing Research. 1995;38:1303–1318. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3806.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merydith SP, Prout HT, Blaha J. Social desirability and behavioral rating scales: An exploratory study with the Child Behavior Checklist/4-18. Psychology in the Schools. 2003;40:225–235. [Google Scholar]

- Morrow CE, Bandstra ES, Anthony JC, Ofir AY, Xue L, Reyes M. Influence of prenatal cocaine exposure on full-term infant neurobehavioral functioning. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 2001;23:533–544. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(01)00173-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO, Muthén L. Mplus Software [CD-ROM] Muthén B.O. & Muthén L; Los Angeles, CA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson S, Lerner E, Needlman R, Salvator A, Singer LT. Cocaine, anemia, and neurodevelopmental outcomes in children: A longitudinal study. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2004;25:1–9. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200402000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nulman I, Rovet J, Greenbaum R, Loebstein M, Wolpin J, Pace-Asciak P, Koren G. Neurodevelopment of adopted children exposed in utero to cocaine: The Toronto Adoption Study. Clinical and Investigative Medicine. 2001;24:129–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlebeke JF, Knol DL, Verhulst FC. Child behavior problems increased by maternal smoking during pregnancy. Archives of Environmental Health. 1999;54:15–19. doi: 10.1080/00039899909602231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelps L, Cottone JW. Long-term developmental outcomes of prenatal cocaine exposure. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment. 1999;17:343–353. [Google Scholar]

- Phelps L, Wallace NV, Bontrager A. Risk factors in early child development: Is prenatal cocaine/polydrug exposure a key variable? Psychology in the Schools. 1997;34:245–252. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson GA. Prenatal cocaine exposure: A longitudinal study of development. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1998;846:144–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson GA, Conroy ML, Day NL. Prenatal cocaine exposure: Effects on the development of school-age children. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 1996;18:627–634. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(96)00121-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer LT, Arendt RE, Song LY, Warshawsky E, Kliegman RM. Direct and indirect interactions of cocaine with childbirth outcomes. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 1994;148:959–964. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1994.02170090073014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotkin TA. Fetal nicotine or cocaine exposure: Which one is worse? Journal of Pharmacology & Experimental Therapeutics. 1998;285:931–945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statacorp. Stata Statistical Software. Stata Corporation; College Station, TX: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- UNODC. World Drug Report. Volume 1: Analysis. United Nations; New York: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Volpe JJ. Effect of cocaine use on the fetus. New England Journal of Medicine. 1992;327:399–407. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199208063270607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakschlag LS, Lahey BB, Loeber R, Green SM, Gordon RA, Leventhal BL. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and the risk of conduct disorder in boys. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54:670–676. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830190098010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youngstrom E, Izard C, Ackerman B. Dysphoria-related bias in maternal ratings of children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:905–916. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]