Abstract

An asymmetric approach for the synthesis of substituted δ-sultams with multiple synthetic handles is described. This study demonstrates the facile construction of a stereochemically diverse array of substituted δ-sultams, more specifically substituted 3,4,5,6-dihydro 1,2-thiazine 1,1-dioxides. A pivotal Mitsunobu alkylation/RCM sequence is used to assemble key allyl sultam building blocks possessing a C3 stereogenic handle. All subsequent reactions are achieved with high levels of diastereoselectivity to afford enantiopure δ-sultams in good yields.

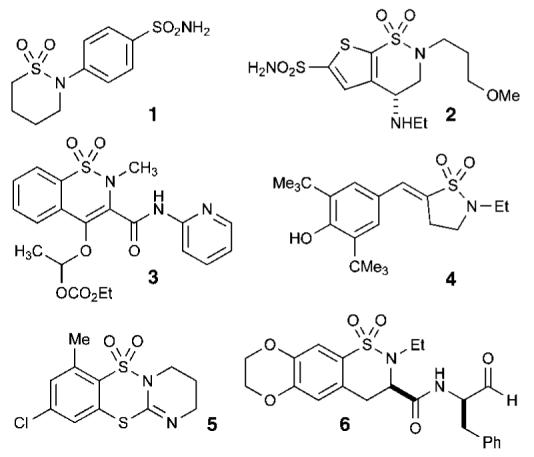

Compounds containing the sulfonamide moiety have gained wide popularity due to their extensive chemical and biological profiles, making them promising candidates in drug discovery.1 Sultams (cyclic sulfonamides), although not found in nature,2 have also shown potent biological activity, including several with medicinal value. A brief survey of the literature reveals that there are more than 60 sultams with impressive biological activity. The more prominent include the antiepileptic agent sulthiame (1) (Figure 1),3 brinzolamide (2)4 for the treatment of glaucoma, the COX-2 inhibitors ampiroxicam (3)5 and S-2474 (4),6 novel benzodithiazine dioxides with both antiviral and anticancer activities (5),7a selective inhibitors of calpain I (6),7b and most recently pyrrolo[1,2-b][1,2,5]benzothiadiazepines,8 a new class of potential agents for treatment against chronic myelogenous leukemia. In addition, this impressive biological profile is augmented by a number of chemical properties including facile coupling pathways for their formation, stability to hydrolysis, polarity, and their crystalline nature. Taken collectively, these attributes have allowed sultams to emerge as privileged structures in drug discovery.

Figure 1.

Biologically active sultams.

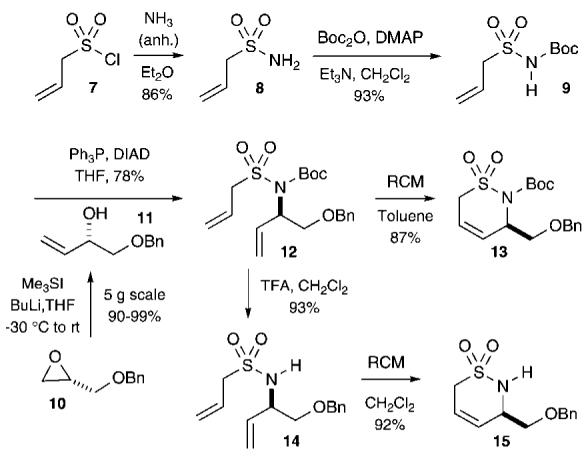

Traditionally, sultam synthesis has relied on classical cyclization protocols such as Pictet-Spengler,8 Friedel-Crafts,9 dianion,10 cyclization of aminosulfonyl chlorides,11 [3 + 2] cycloadditions,12 and Diels-Alder reactions.13 Recently, however, a number of transition-metal-catalyzed approaches to sultams have come to light, including the use of Pd-,14 Au-,15 Cu-,16 and Rh-catalyzed cyclizations.17 Moreover, RCM has been reported to generate several interesting sulfur-containing heterocycles with biological potential.2,18 Our continuous interest in the development of transition-metal-catalyzed approaches to sulfur and phosphorus heterocycles (S- and P-heterocycles)18 has prompt us to investigate an RCM approach for the synthesis of chiral, nonracemic sultams. The method is designed to afford sultams containing multiple handles as attractive scaffolds for potential library production with the ultimate goal of uncovering interesting biological leads. The method we herein report utilizes a key Mitsunobu alkylation reaction to install a stereogenic center at C3 (Scheme 1). Ensuing metathesis is used as the cyclization event to yield key allyl sultam building blocks 13 and 15. All subsequent reactions leading to more complex building blocks are achieved with high levels of diastereoselectivity to afford enantiopure δ-sultams in good yields (Schemes 2-5).

Scheme 1.

RCM Strategy to Sultams 13 and 15

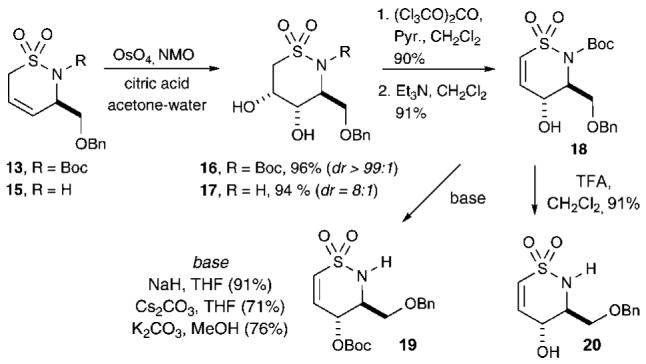

Scheme 2.

Facile Route to γ-Hydroxy Sultam 18

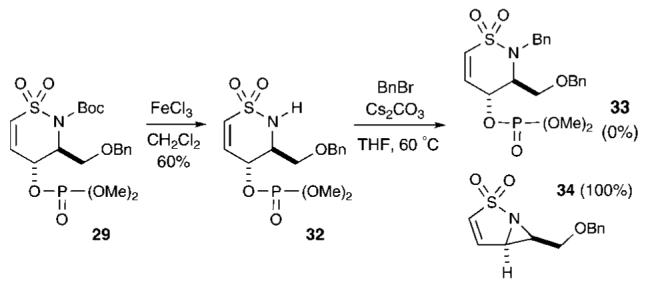

Scheme 5.

Unexpected Internal SN2 Displacement Pathway

Our approach began with the multigram production of allylsulfonyl chloride (7).19 Subsequent amination with anhydrous NH3, following the procedure reported by Belous and co-workers, afforded sulfonamide 8 in good yields.19 Mono-protection with Boc2O20 afforded sulfonamide 9 (93%), possessing an acidic proton (N-H) suitable for Mitsunobu alkylation (Scheme 1). Mitsunobu reaction with chiral, nonracemic alcohol 11, derived from epoxide 10 using the Christie protocol,21 afforded the RCM precursor 12 in good yield (78%). Initial attempts to obtain 13 via RCM using the second-generation Grubbs catalyst22 in refluxing CH2Cl2 or DCE were unsuccessful. Subsequent RCM studies revealed that 13 could be obtained in good yield when toluene was used as the solvent under refluxing conditions. Alternatively, Boc-removal in diene 12 using TFA, followed by RCM in refluxing CH2Cl2, afforded the δ-sultam 15 in excellent yield.23

The diastereoselective route to the desired δ-sultam 18 continued with dihydroxylation of cyclized products 13 and 15 (Scheme 2). When sultam 15 (R = H) was first subjected to dihydroxylation, an inseparable mixture of diastereomers (dr ∼8:1) was obtained. However, dihydroxylation of the Boc-protected sultam 13 resulted in the formation of cis-diol 16 as a single diastereomer in excellent yield (96%). This result further substantiates the aforementioned A1,2 effects,23 which presumably force the CH2OBn group at C3 into an axial orientation, thus accentuating dihydroxylation from the opposite face. The relative stereochemistry of 16 was confirmed by X-ray crystallography (see the Supporting Information). Conversion of this diol to the respective carbonate was achieved using triphosgene,24,25 followed by base-promoted elimination with Et3N25 under refluxing DCM to afford the γ-hydroxy vinyl δ-sultam 18 in 91% yield. This protocol was previously shown in our laboratory to be applicable to the synthesis of phosphono sugars.25 Attempted functionalization of the C4 hydroxyl group in sultam 18 using various inorganic bases such as NaH, Cs2CO3, or K2CO3 resulted in an unexpected intramolecular Boc-migration onto the γ-hydroxy group, providing δ-sultam 19 in good to excellent yields (Scheme 2). Schreiber and co-workers have previously reported an analogous Boc group migration event.26 Treatment of sultam 18 with TFA in CH2Cl2 resulted in Boc removal to afford the γ-hydroxy vinyl δ-sultam 20 as a crystalline solid in 91% yield.

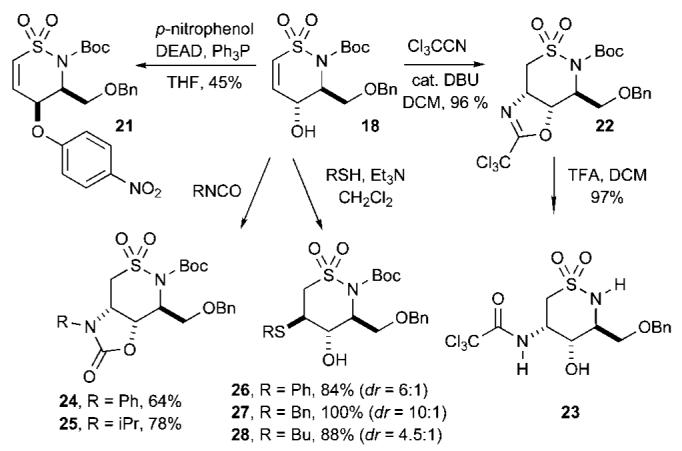

With the desired scaffold 18 in hand, we turned our attention to an array of diversification reactions highlighted in Scheme 3. Mitsunobu reaction with p-nitrophenol afforded allylic ether 21 in moderate yields. Attempts to perform the Mitsunobu reaction with phenol or substituted phenols containing electron-donating groups were unsuccessful. We next focused on the addition of nucleophiles into 18. Consequently, 18 was treated with Cl3CCN in the presence of catalytic amounts of DBU in CH2Cl2 to afford trichloro-acetimidate 22 in excellent yield (96%) via an intramolecular Michael addition. Further treatment of 22 with TFA (CH2Cl2 at rt) afforded amino alcohol 23 in 97% yield (Scheme 3). This concept was expanded to isocyanates in attempts to form bicyclic sultams. Treatment of 18 with phenyl isocyanate (PhNCO) and Et3N in CH2Cl2 at reflux afforded sultam 24 in good yield (64%) via conjugate addition (Scheme 3). When isopropyl isocyanate (iPrNCO) was utilized under identical conditions, prolonged reaction times were necessary to obtain the cyclized product 25 in good yield (78%).

Scheme 3.

Diversification of Sultam 18

Intermolecular nucleophilic additions of thiols were next explored. Previous work reported by Roush27 revealed that vinyl sulfonamides are good Michael acceptors of sulfur nucleophiles. Addition of PhSH to sultam 18 in the presence of catalytic amounts of Et3N (CH2Cl2 at rt)28 afforded sultam 26 in good yield (84%) as a mixture of inseparable diastereomers (dr ∼6:1) as determined by 1H NMR. Addition of PhCH2SH under identical reaction conditions afforded sultam 27 in quantitative yield as a separable mixture of diastereomers with improved diastereoselectivity (dr ∼ 10:1). Addition of butanethiol resulted in the formation of sultam 28 in 88% yield as a mixture of inseparable diastereomers (dr ∼4.5:1). The addition of 2-methyl-propane-2-thiol [(CH3)3CSH] under the same reaction conditions failed to produce the Michael adduct, presumably due to steric factors.

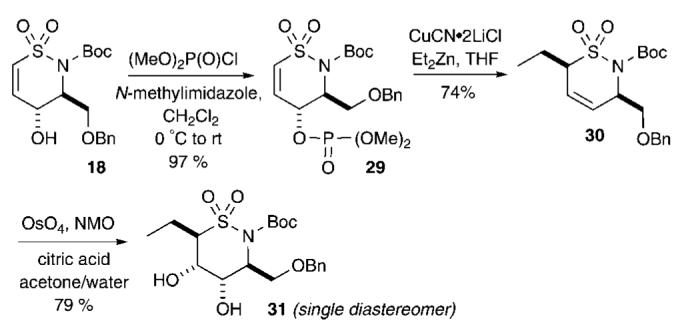

Interest in potential diversification at the α-position of sultam 18 led us to explore installation of alkyl groups with the ultimate goal of incorporating different functional groups throughout the periphery of the ring. In order to accomplish this, we explored the use of an SN2′ cuprate displacement of the corresponding phosphate.29 Thus, treatment of 18 with (MeO)2P(O)Cl in the presence of N-methylimidazole in CH2Cl2 at 0 °C afforded allylic phosphate 29 in excellent yield (97%) (Scheme 4).30 Subjection of allylic phosphate 29 to conjugate addition via ethyl cuprate formation under Knochel’s conditions31 was performed by adding an excess of diethylzinc cuprate to provide sultam 30 in good yield (74%) and excellent regio- and diastereoselectivity. The 3,6-disubstituted δ-sultam 30 was tentatively assigned as the diastereomer arising from anti addition in accordance with the Corey mechanism.29b,c This product was further dihydroxylated under Os-mediated conditions to afford cis-diol 31 as a single diastereomer in good yield (79%).

Scheme 4.

Diastereoselective Phosphate Displacement

A diversification/cuprate addition strategy was next explored. This approach involved deprotection via removal of the N-Boc group, followed by benzylation at the free N-H site to generate sultam 33 (Scheme 5). Initial attempts to remove the Boc group in sultam 29 using TFA in CH2Cl2 resulted in hydrolysis of the phosphate moiety. Milder reaction conditions were then studied and revealed that treatment of sultam 29 with 1.0-1.5 equiv of FeCl332 (CH2Cl2, rt, 30 min) afforded, after aqueous workup, sultam 32 in 60% yield. Introduction of an alkyl group at the nitrogen was sought via benzylation under basic conditions (BnBr, Cs2CO3, THF, 65 °C) to obtain benzyl sultam 33. However, a product lacking both phosphate and benzyl moieties was isolated and later confirmed as aziridine 34. This unexpected product is presumably the result of direct internal nucleophilic displacement of the C(4)-substituted phosphate. Additional studies concerning this internal SN2 displacement pathway are underway.

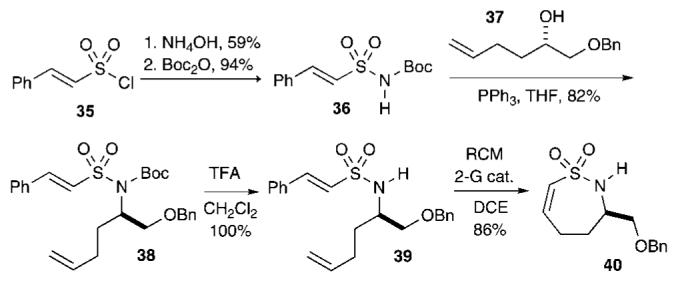

The RCM strategy utilized for the facile assembly of δ-sultam scaffolds prompted our efforts into extending this methodology for the construction of 7-membered vinylic sultams as outlined in Scheme 6. Thus, treatment of styrylsulfonyl chloride33 35 with NH4OH, followed by slow addition of Boc2O,20 afforded Boc-protected styrylsulfonamide 36 in high yield (94%). Mitsunobu alkylation with chiral, nonracemic alcohol 3734 afforded diene 38 in 82% yield. Removal of the Boc-group utilizing TFA in CH2Cl2 at rt provided sulfonamide 39 in quantitative yield. RCM in refluxing DCE afforded the seven-membered ring vinylic sultam 40 in 86% yield.

Scheme 6.

RCM Strategy to Seven-Membered Sultam 40

In conclusion, we have demonstrated a new method to synthesize a stereochemically diverse array of substituted 1,2-thiazine 1,1-dioxides. These scaffolds represent novel sultams, which can be utilized in the production of versatile and novel libraries. These studies are underway and will be reported in due course.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This investigation was generously supported by funds provided by the National Institutes of General Medical Sciences Center for Chemical Methodologies and Library Development at the University of Kansas (P50 GM069663, Minority Supplement, M.J.-H.). We thank Dr. Victor Day of the Molecular Structure Group (MSG) at the University of Kansas for X-ray analysis. We kindly acknowledge Materia, Inc., for supplying metathesis catalyst and Daiso Co., Ltd., Fine Chemical Department for donation of benzyl-protected glycidol (e-mail: akkimura@daiso.co.jp).

References

- (1)(a).Drews J. Science. 2000;287:1960–1964. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5460.1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Scozzafava A, Owa T, Mastrolorenzo A, Supuran CT. Curr. Med. Chem. 2003;10:925–953. doi: 10.2174/0929867033457647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Hanessian S, Sailes H, Therrien E. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:7047–7056. [Google Scholar]

- (3).Tanimukai H, Inui M, Harigushi S, Kaneko J. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1965;14:961–970. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(65)90248-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Wroblewski T, Graul A, Castaner J. Drugs Future. 1998;23:365–369. [Google Scholar]

- (5).Rabasseda X, Hopkins SJ. Drugs Today. 1994;30:557–563. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Inagaki M, Tsuri T, Jyoyama H, Ono T, Yamada K, Kobayashi M, Hori Y, Arimura A, Yasui K, Ohno K, Kakudo S, Koizumi K, Suzuki R, Kawai S, Kato M, Matsumoto S. J. Med. Chem. 2000;43:2040–2048. doi: 10.1021/jm9906015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7)(a).Brzozowski Z, Saczewski F, Neamati N. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006;16:5298–5302. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.07.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wells GJ, Tao M, Josef KA, Bihovsky R. J. Med. Chem. 2001;44:3488–3503. doi: 10.1021/jm010178b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Silvestri R, Marfè G, Artico M, La Regina G, Lavecchia A, Novellino E, Morgante M, Di Stefano C, Catalano G, Filomeni G, Abruzzese E, Ciriolo MR, Russo MA, Amadori S, Cirilli R, La Torre F, Salimei PS. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:5840–5844. doi: 10.1021/jm0602716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9)(a).Bravo RD, Cánepa AS. Synth. Commun. 2002;32:3675–3680. [Google Scholar]; (b) Orazi OO, Corral RA, Bravo R. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1986;23:1701–1708. [Google Scholar]; (c) Katritzky AR, Wu J, Rachwal S, Rachwal B, Macomber DW, Smith TP. Org. Prep. Proced. Int. 1992;24:463–467. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Lee J, Zhong Y-L, Reamer RA, Askin D. Org. Lett. 2003;5:4175–4177. doi: 10.1021/ol0356183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Enders D, Moll A, Bats JW. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2006:1271–1274. [Google Scholar]

- (12).Chiacchio U, Corsaro A, Rescifina A, Bkaithan M, Grassi G, Piperno A. Tetrahedron. 2001;57:3425–3433. [Google Scholar]

- (13)(a).Metz P, Seng D, Fröhlich R. Synlett. 1996:741–742. [Google Scholar]; (b) Plietker B, Seng D, Fröhlich R, Metz P. Tetrahedron. 2000;56:873–879. [Google Scholar]; (c) Rogatchov VO, Bernsmann H, Schwab P, Fröhlich R, Wibbeling B, Metz P. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:4753–4756. [Google Scholar]; (d) Greig IR, Trozer MJ, Wright PT. Org. Lett. 2001;3:369–371. doi: 10.1021/ol006863e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Wanner J, Harned AM, Probst DA, Poon KWC, Klein TA, Snelgrove KA, Hanson PR. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:917–921. [Google Scholar]

- (14)(a).Merten S, Fröhlich R, Kataeva O. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2005;347:754–758. [Google Scholar]; (b) Vasudevan A, Tseng P-S, Djuric SW. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47:8591–8593. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Liu X-Y, Li C-H, Che C-M. Org. Lett. 2006;8:2707–2710. doi: 10.1021/ol060719x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16)(a).Dauban P, Dodd RH. Org. Lett. 2000;2:2327–2329. doi: 10.1021/ol000130c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dauban P, Sanière L, Aurélie T, Dodd RH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:7707–7708. doi: 10.1021/ja010968a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Sherman ES, Chemler SR, Tan TB, Gerlits O. Org. Lett. 2004;6:1573–1575. doi: 10.1021/ol049702+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Zeng W, Chemler SR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:12948–12949. doi: 10.1021/ja0762240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17)(a).Liang J-L, Yuan S-X, Chan PWH, Che C-M. Org. Lett. 2002;4:4507–4510. doi: 10.1021/ol0270475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Padwa A, Flick AC, Leverett CA, Stengel T. J. Org. Chem. 2004;69:6377–6386. doi: 10.1021/jo048990k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18)(a).McReynolds MD, Dougherty JM, Hanson PR. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:2239–2258. doi: 10.1021/cr020109k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Moriggi J-M, Brown LJ, Castro JL, Brown RCD. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2004;2:835–844. doi: 10.1039/b313686h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Freitag D, Schwab P, Metz P. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004;45:3589–3592. [Google Scholar]; (d) Karsch S, Freitag D, Schwab P, Metz P. Synthesis. 2004;10:1696–1712. [Google Scholar]

- (19).Belous MA, Postovsky IY. J. Gen. Chem. USSR. 1950;20:1761–1770. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Neustadt BR. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:379–380. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Davoille RJ, Rutherford DT, Christie SDR. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:1255–1259. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Scholl M, Ding S, Lee CW, Grubbs RH. Org. Lett. 1999;1:953–956. doi: 10.1021/ol990909q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23). These results indicated that A1,2-strain between the vicinally substituted Boc-group at N2 and the CH2OBn group at C3 presumably force the two terminal olefins to orient in opposite directions, thus requiring higher temperatures for cyclization.

- (24).Nicolaou KC, Li Y, Sugita K, Monenschein H, Guntupalli P, Mitchell HJ, Fylaktakidou KC, Vourloumis D, Giannakakou P, O’Brate A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:15443–15454. doi: 10.1021/ja030496v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25)(a).Stoianova DS, Hanson PR. Org. Lett. 2001;3:3285–3288. doi: 10.1021/ol016491p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Stoianova DS, Whitehead A, Hanson PR. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:5880–5889. doi: 10.1021/jo0505122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26)(a).Valentekovich RJ, Screiber SL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:9069–9070. [Google Scholar]; (b) Bew SP, Bull SD, Davies SG. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:7577–7581. For other examples, see. [Google Scholar]; (c) Branch L, Norrby P-O, Frydenvag K, Krogsgaard-Larsen P, Madsen U. Org. Lett. 2001;3:433–435. doi: 10.1021/ol0069397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Reddick JJ, Cheng J, Roush WR. Org. Lett. 2003;5:1967–1970. doi: 10.1021/ol034555l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Isaksson D, Sjödin K, Högberg H-E. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2006;17:275–280. [Google Scholar]

- (29)(a).Yanagisawa A, Noritake Y, Nomura N, Yamamoto H. Synlett. 1991:251–253. [Google Scholar]; (b) Corey EJ, Boaz NW. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984;25:3063–3066. [Google Scholar]; (c) Whitehead A, McParland JP, Hanson PR. Org. Lett. 2006;8:5025–5028. doi: 10.1021/ol061756r. and references cited therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30)(a).Xu Y, Quian L, Pontsler AV, McIntyre TM, Prestwich GD. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:43–49. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Calaza MI, Hupe E, Knochel P. Org. Lett. 2003;5:1059–1061. doi: 10.1021/ol0340742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32)(a).Pospísil J, Markó IE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:3516–3517. doi: 10.1021/ja0691728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Padrnó JI, Vázquez JT. Tetrahdron: Asymmetry. 1995;6:857–858. [Google Scholar]

- (33).Culbertson BM, Dietz S. J. Chem. Soc. C. 1968:992–993. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Rutjes FPJT, Kooistra TM, Hiemstra H, Schoemaker HE. Synlett. 1998:192–194. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.