Abstract

To describe how the tobacco and gaming industries opposed clean indoor air voter initiatives in 2006, we analyzed media records and government and other publicly available documents and conducted interviews with knowledgeable individuals. In an attempt to avoid strict “smoke free” regulations pursued by health groups via voter initiatives in Arizona, Ohio, and Nevada, in 2006, the tobacco and gaming industries sponsored competing voter initiatives for alternative laws.

Health groups succeeded in defeating the pro-tobacco competing initiatives because they were able to dispel confusion and create a head-to-head competition by associating each campaign with its respective backer and instructing voters to vote “no” on the pro-tobacco initiative in addition to voting “yes” on the health group initiative.

CLEAN INDOOR AIR LAWS, designed to protect nonsmokers from secondhand tobacco smoke, also decrease smoking prevalence and cigarette consumption.1–3 In 2006, health groups passed statewide clean indoor air laws through the ballot initiative process (enacting a law by direct popular vote) in 3 states: Arizona, Ohio, and Nevada. In response to these public health efforts, the tobacco and gaming industries organized competing pro-tobacco ballot initiatives in an attempt to implement pro-tobacco laws and avoid the strict regulations proposed by health groups. These weak preemptive “look-alike” laws (Table 1) were presented as strong “reasonable” clean indoor air alternatives to the health groups' proposals.

TABLE 1.

Clean Indoor Air Voter Initiatives Sponsored by Health Groups and Competing Pro-Tobacco Initiatives in 3 States in 2006

| Arizona |

Ohio |

Nevada |

||||

| Pro-Health | Pro-Tobacco | Pro-Health | Pro-Tobacco | Pro-Health | Pro-Tobacco | |

| Name of proposed law | Smoke Free Arizona Act | Arizona Non-Smoker Protection Act | Smoke Free Workplace Act | Restrict Smoking Places (constitutional amendment) | Clean Indoor Air Act | Responsibly Protect Nevadans from Second Hand Smoke Act |

| Campaign name | Smoke Free Arizona | Arizona Non-Smoker Protection Committee | Smoke Free Ohio | Smoke Less Ohio | Nevadans for Tobacco Free Kids | Smoke Free Coalition |

| Primary sponsors | ACS, AHA, ALA | RJ Reynolds, Arizona Licensed Beverage Association | ACS, AHA, ALA | RJ Reynolds, Ohio Licensed Beverage Association | ACS, AHA, ALA | Slot Route Operators, Herbst Gaming |

| Ballot designation | Proposition 201 | Proposition 206 | Issue 5 | Issue 4 | Question 5 | Question 4 |

| Milestones | ||||||

| Signature gathering started | August 31, 2005 | May 24, 2006 | May 3, 2005 | May 2006 | March 2004 | August 2004 |

| Qualified for ballot | August 4, 2006 | August 23, 2006 | September 8, 2006 | September 28, 2006 | March 2005 | March 2005 |

| Key smoke-free provisions | ||||||

| Workplaces (nonhospitality) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No (required smoking sections) |

| Restaurants | Yes | Yes (except bar areas) | Yes | No (required smoking sections) | Yes | No (required smoking sections) |

| Bars | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Casinos | NA | NA | Yes | No | No | No |

| Grocery and convenience stores | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Preemptiona | No | Yes (impose preemption) | No | Yes (impose preemption) | No (repeal existing preemption) | Yes (maintain existing preemption) |

| Enforcement | Department of Health Services | None | State Health Department | None | County Health Divisions | None |

| Campaign financing | ||||||

| Target budget | $2 million–$3 million | NA | $3 million | NA | $750 000–$1.25 million | NA |

| Actual expenditures | $1.8 million | $8.8 million | $2.7 million | $6.7 million | $570 000 | $2.1 million |

| Largest single funding source | ACS, 54% | RJ Reynolds, 99.8% | ACS, 81% | RJ Reynolds and Smoke Less Ohio Inc,b 99.5% | ACS, 81% | Herbst Gaming, 35% |

| Outcome | Passed, 55% | Failed, 43% | Passed, 58% | Failed, 36% | Passed, 54% | Failed, 48% |

Note. ACS = American Cancer Society; ALA = American Lung Association; AHA = American Heart Association; NA = not available.

Preemption prohibits local city and county councils from enacting stronger legislation.

Smoke Less Ohio Inc. was probably funded by RJ Reynolds.

In a simple contest, when only one initiative is presented to voters, a campaign focuses on the advantages of the proposal over the status quo. Competing initiatives, regardless of the subject matter, generally are introduced by moneyed interests with the primary goal of defeating an original proposal.4 Manipulating voter behavior through competing initiatives is a strategy that has been used by controversial industries such as the chemical and auto insurance industries to avoid strict regulation.5,6 In Arizona, Ohio, and Nevada, competing pro-tobacco proposals forced health advocates to mount campaigns that not only promoted their initiatives but also exposed the weaknesses of the pro-tobacco competing proposals.

BACKGROUND

At the beginning of the nonsmokers' rights movement in the early 1970s, health advocates used ballot initiatives to enact smoking restrictions requiring nonsmoking seating sections in response to the tobacco industry's power to block such laws in state and local legislatures.7–9 In these efforts, tobacco control advocates underestimated the expense and difficulty of running ballot initiatives against the industry, and generally lost.7,10–12 As scientific evidence demonstrating the dangers of secondhand tobacco smoke accumulated and health advocates became more sophisticated in isolating the tobacco industry, they experienced increased success at passing clean indoor air regulations legislatively, especially at the local level. Local venues proved more productive for tobacco control advocates because local lawmakers are more responsive to public opinion and less sensitive to campaign contributions from out-of-town tobacco interests.7,9,11,12 Indeed, the tobacco industry often tried to shift the field of play back to the (more expensive) ballot by forcing referendums (repealing laws by popular vote) as a way of rolling back or preventing passage of local clean indoor air legislation.7,10–13 Although these industry efforts raised the cost of enacting some local clean indoor air ordinances, they generally failed to overturn the laws.7,10–13

Beginning in Florida in 1985, the tobacco industry responded to health advocates' efforts to pass clean indoor air acts by promoting weak state laws that nominally restricted smoking in some venues while including preemption, which prohibited local city and county councils from enacting stronger legislation.14–16 By the 1990s, enacting preemption had become a major policy priority for the tobacco industry as a way to contain the burgeoning grassroots clean indoor air movement.16,17 Through the late 1980s and 1990s, clean indoor air ordinances passed at an accelerating rate at the local level in states without preemption while no progress occurred in the states (only 22 ordinances by 2004) with preemption.18

In the early 2000s, health advocates returned to using ballot initiatives as a way to circumvent pro-tobacco city councils and state legislatures. Local ballot initiatives from 2000 through 2002 resulted in at least 8 communities in Oregon, Ohio, Colorado, and Arizona passing local clean indoor air laws.18 (During the same period, 130 local and 2 state laws were passed legislatively.18) The ballot initiative route gained additional momentum and national attention when in 2002 tobacco control advocates in Florida spent $5.9 million and successfully amended the state's constitution via ballot initiative to replace Florida's weak 1985 preemptive state antismoking law with one making workplaces and restaurants (but not bars) smoke free,19 with 71% of Floridians voting in favor of the law.

Motivated by this momentum, tobacco control advocates used the initiative process to enact another 18 local and 4 state clean indoor air laws through the end of 2006.18 In Washington State in 2005, a law making workplaces, restaurants, and bars smoke free was passed by ballot initiative at a cost of $1.6 million, with 63% of voters in favor.18 In 2006, health groups in Arizona, Ohio, and Nevada, faced with pro-tobacco legislatures, used the initiative process to pursue statewide clean indoor air laws (Table 1).20–22

In response, tobacco companies and their allies attempted a new strategy of mounting competing state initiatives on the same ballots as the health groups' proposals. The tobacco industry had previously attempted to pass a preemptive state law using the initiative process in 1994, when Philip Morris Tobacco Company spent $12.6 million (of $18.9 million total spent by the tobacco industry) unsuccessfully trying to overturn California's statewide smoke-free workplace law with a “look-alike” law that was marketed as protecting nonsmokers but that would actually have weakened the existing strong state law (which went into force in 1994).7,23 Also, in 2004, a group of bar owners were able to defeat health groups' comprehensive clean indoor air initiatives in Fargo and West Fargo, North Dakota, by placing on the same ballot competing initiatives that included workplaces and restaurants but exempted bars.24,25

METHODS

We obtained news reports, public documents, and case studies conducted at the University of California, San Francisco20–22 and interviewed knowledgeable individuals. We selected individuals for interview based on written records (public messaging, media reports, campaign finance reports, and other government filings) and the snowball technique, in which interviewees suggested other interviewees We were unable to interview campaign managers for the pro-tobacco campaigns because we did not have the same access to individuals knowledgeable about those campaigns as we did with the health group initiatives.

The lack of interview data from the pro-tobacco campaigns is a limitation and a potential source of bias in this study.

RESULTS

The Health Group Initiatives

In 2006, health groups in Arizona21 and Ohio20 ran comprehensive clean indoor air initiatives, building on the strong local smoke free ordinances they had previously achieved in those states. One of the factors motivating the effort in Ohio was concern that the state legislature would pass a weak preemptive law overturning the existing local ordinances. In Nevada,22 state preemption barred local smoke free ordinances, so no such foundation of local ordinances existed. Health groups in all 3 states had faced repeated failures in their legislatures prior to attempting ballot initiatives.

Health groups in Arizona and Ohio originally considered exempting bars, but opted for comprehensive clean indoor air proposals following polling that showed strong public support for comprehensive laws (75% in Arizona and 66% in Ohio).20,21 Polling in Nevada22 showed that only 32% of voters were in favor of a comprehensive law, but 71% were in favor of a law that exempted bars, so bars were exempted. The gaming floors of major casinos were exempted in Nevada to avoid strong opposition from the gaming industry (major casinos), which has a long history of working with the tobacco industry to oppose smoking restrictions.26

Securing sufficient funding was a continuous challenge and focus for all 3 campaigns, despite strong financial commitments from the American Cancer Society (each initiative's primary contributor). Clean indoor air acts fail to draw major outside donors because there are no immediate financial returns or future revenue streams as there are for tax proposals.23 The tobacco control campaigns in Arizona, Ohio, and Nevada all fell short of their initial fundraising projections (Table 1), even before the demands on the campaigns increased with the filing of the pro-tobacco competing initiatives.

The pro-tobacco counterinitiatives were not expected by tobacco control advocates and created tremendous anxiety among them. Health groups in all 3 states recognized that they would need more money, primarily for paid advertising, once the competing initiatives were filed. In Ohio, the health campaign, which had originally sought to raise $3 million, revised its fundraising target to $4 million once they learned of the RJ Reynolds Tobacco–sponsored competing initiative. All 3 health campaigns struggled with fundraising, which forced the American Cancer Society to provide additional money to allow the campaigns to continue.

The Pro-Tobacco Counterinitiatives

While health groups were gathering signatures for their initiatives in Arizona and Ohio (in April 2006) and in Nevada (in 2004), where an initiative cannot be voted on until 2 years after signatures have been collected, the pro-tobacco counterinitiatives were launched. In Arizona and Ohio, RJ Reynolds, working with the state Licensed Beverage Associations, long-time allies of the tobacco industry,20,21,27 sponsored the competing initiatives (Table 1). RJ Reynolds saw the health groups' “smoke free” initiatives as an opportunity to forward their agenda by using the health group initiatives as foils. The open involvement of RJ Reynolds in the initiatives in Arizona and Ohio signaled a shift in the tobacco industry's strategy. Because of the industry's low public credibility, it had traditionally tried to remain in the background and work through front groups.7,9,12,27 During the campaign in Arizona, where the competing initiative was named Proposition 206, RJ Reynolds Executive Vice President Tommy Payne sent a letter directly to the state's voters, which was also prominently posted on the pro-tobacco group Yes on 206's Web site (now defunct):

One of the many benefits of living in a democracy is our ability to participate in the political process and freely make our views known in a way that impacts public policy. As executive vice president of RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company, one public issue I am increasingly concerned about is the proliferation of smoking bans that make no exceptions for adult-only venues like bars. … We are not trying to hide our participation in this election.28

RJ Reynolds's open involvement in Arizona and Ohio made it easier for the tobacco control groups to distinguish their initiatives from the pro-tobacco counterinitiative by associating each with its respective backer. In Nevada, where state preemption was already in place, the pro-tobacco initiative allowed smoking in bars, restaurants, grocery stores, convenience stores, and any other location where slot machines were located (Table 1). This initiative was backed by a group of gaming companies called Slot Route Operators, an element of Nevada's gaming industry distinct from the major gaming resorts. The Slot Route Operators represent businesses that operate slot machines in grocery stores, convenience stores, restaurants, bars, and other noncasino gaming areas. The major casinos remained neutral because the health group initiative exempted their gaming floors.23

There was no apparent connection between the Slot Route Operators' counterinitiative and the tobacco companies. The tobacco industry appeared content to let its interests be represented by the Slot Route Operators23; it made no direct campaign contributions, and no public correspondence took place between the 2 industries during that time. RJ Reynolds may not have considered itself threatened by Nevada's tobacco control initiative because, like RJ Reynolds's initiatives in Arizona (Table 1), it preserved smoking in bars, a key venue in which RJ Reynolds had pioneered a way to promote its products.29–32

The Campaigns

Prior to the introduction of the competing pro-tobacco initiatives, the health groups were preparing simple campaigns designed to win majority votes. When the tobacco control campaigns learned of the pro-tobacco competing initiatives, they redesigned their campaign strategies to simultaneously promote their proposals while urging that the pro-tobacco initiatives be defeated. Defeating the pro-tobacco proposals was critical, because passage of both initiatives in Arizona or Nevada would have left the handling of the resulting conflicts to the courts, Generally, when 2 ballot initiatives on the same subject pass, all provisions go into effect, with those that received more votes taking precedence when a conflict arises.4 In Ohio, if both initiatives had passed, the pro-tobacco initiative would have taken precedence even if it received fewer votes because it was a constitutional amendment and the health group proposal was a state law.

The health group campaigns.

Health advocates were concerned that the pro-tobacco initiatives would confuse voters and that voters would either vote “no” on both proposals through confusion or vote “yes” on both proposals in the belief that both were authentic tobacco control measures. With this concern in mind, the key objective of the health groups' campaigns was to leverage public support for clean indoor air by (1) maintaining a consistent message that clean indoor air laws are good for public health, (2) associating the pro-health initiative with high-credibility health groups such as the American Cancer Society and the pro-tobacco initiative with the low-credibility tobacco industry, and (3) ensuring the public knew that if they supported public health, they must also vote against the pro-tobacco initiative.

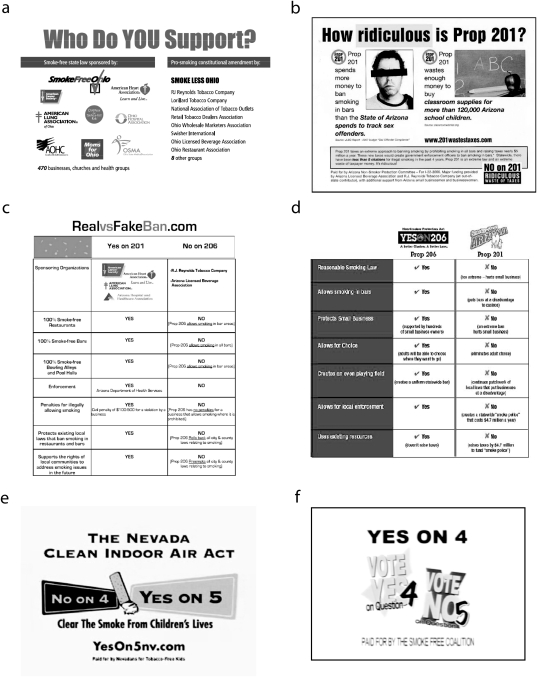

Messaging from the tobacco control campaigns in all 3 states consistently reinforced the campaigns' 3 primary objectives (Figure 1). Protecting public health was the main theme in all 3 states, but additional emphasis was placed in Arizona and Nevada on child health and in Arizona and Ohio on the health of hospitality workers. One of the television commercials run throughout the campaign by Smoke Free Arizona started by asking, “What if your one vote could protect children and workers from dangerous secondhand smoke and make every restaurant in Arizona smoke free? You can.”21

FIGURE 1.

Advertisements in the 2006 campaign for competing antismoking initiatives from (a) the Ohio health group campaign (“Who Do You Support?”), (b) the Arizona pro-tobacco campaign (“How Ridiculous is Prop 201?”), (c) the Arizona health group campaign (RealvsFakeBan.com”), (d) the Arizona pro-tobacco campaign (“Yes on 206”), (e) the Nevada health group campaign (“The Nevada Clean Indoor Air Act”), and (f) the Nevada pro-tobacco campaign (“Yes on 4”).

Associating the tobacco control initiatives with the voluntary health agencies and the competing campaigns with pro-tobacco interests was important for drawing a clear distinction between the 2 proposals, particularly since the pro-tobacco initiatives also presented themselves as “smoking bans” (Figure 1). The open involvement of the tobacco and gaming industries helped the health groups meet this objective. A major component of commercials and other public communications from the tobacco control campaigns were statements in Ohio such as, “Issue 4 is backed by Big Tobacco … and Issue 5 is led by the American Cancer Society” (Figure 1).20 Statements such as these helped the health groups differentiate the competing campaigns in the minds of the public.

The third major objective of the health group campaigns was to ensure that voters knew that if they supported public health they also needed to vote against the pro-tobacco initiatives. The tobacco control campaigns in all 3 states were concerned that the competing pro-tobacco initiatives would confuse voters, leading to a situation where both competing initiatives would be voted down or both might pass. To avoid this situation, the campaigns all made voting “no” on the pro-tobacco initiatives a part of their messaging in addition to voting “yes” on the tobacco control initiative (Figure 1). For example, a consistent pattern used in television ads and other public communications by the Smoke Free Ohio campaign was “If Issue 4 [pro-tobacco initiative] wins, you lose. Vote no on Issue 4, vote yes for Issue 5 [tobacco control initiative].”33

Because their budgets for advertising were one tenth to one third what the pro-tobacco initiatives spent (Table 1), the health groups had to depend heavily on earned media (free media exposure). The voluntary health organizations had their volunteers participate in a range of activities, from meeting newspaper editorial boards to spreading the public health message through word of mouth in their local communities. One of the campaign managers for Nevada commented after the tobacco control initiative passed, “Had it not been for the earned media, we would have never won because they [earned media] carried the message for us.”

The pro-tobacco competing campaigns.

Creating confusion was the pro-tobacco interests' key strategy for defeating the health proposals. In Arizona and Ohio, the RJ Reynolds initiatives, marketed as alternative “smoking bans,” were named “Smoke Less Ohio” and “The Arizona Non-Smoker Protection Act” (Table 1). The pro-tobacco campaigns stated that their initiatives were “common sense” and “reasonable” smoking bans that would protect jobs, as opposed to the health groups' “extreme” smoking bans, which would create a “smoking police” and would harm the economy (Figure 1).34

An Arizona Republic news article35 during the campaign called RJ Reynolds's competing initiative a “switch-don't-fight strategy” purporting to “give voters a choice” and to “balance protection of public health with protection against an overly intrusive government.” It noted that the pro-tobacco initiative created “confusion … even the names of the initiatives sound nearly the same.”35 The tobacco industry, in putting forward partial “smoking bans” rather than resisting policy change altogether, robbed the health groups of a clear distinction between health interests and big tobacco. RJ Reynolds's reinvention of its opposition as a compromise plan, positioning its own proposal as the reasonable middle between the status quo and the health groups' “extremist” law, complicated the traditional tactics of tobacco control advocacy.

Paid media was the primary form of public messaging for the RJ Reynolds campaigns in Arizona and Ohio, which spent $6.8 and $3.1 million on media, respectively. (By contrast, the health groups spent $655 000 and $1.17 million on paid media in Arizona and Ohio, respectively.36,37) The pro-tobacco campaigns did not have a significant grassroots or volunteer base to help disseminate their messages, and their press coverage was problematic because the vast majority of news articles and editorials supported the health group campaigns and frequently exposed the pro-tobacco campaigns' deceptive claims of supporting comprehensive tobacco control measures.

In Nevada, the Slot Route Operators' initiative based its entire campaign on a strategy of confusion by portraying their proposal as the “real smoking ban.” The pro-tobacco campaign in Nevada never tried to portray itself as an alternative proposal and did not raise the issue of jobs or economic concerns as had been done in Arizona and Ohio. One of the managers of the tobacco control campaign commented that the issue of jobs and economics was its largest vulnerability in Nevada, and it was a strategic mistake on the part of the pro-tobacco campaign not to make it one of their central issues. As in Arizona and Ohio, the primary form of public messaging from the pro-tobacco campaign in Nevada was paid media, in the form of television commercials, at a cost of $917 000 (compared with $385 000 in paid media bought by the health groups).38

Polling and the Elections

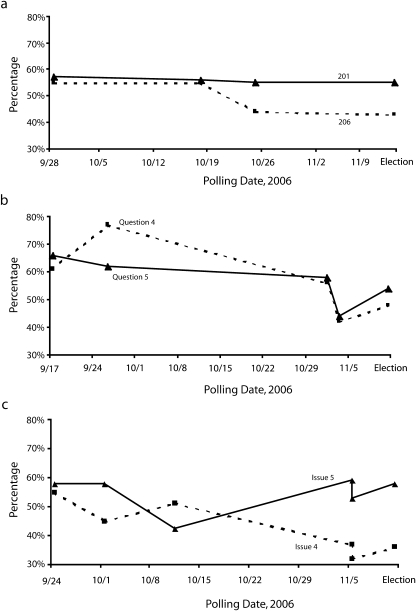

At the beginning of the campaign season in September, polls showed both the pro-tobacco and pro-health initiatives passing in all 3 states (Figure 2). As the competing campaigns progressed toward election day in November, polls showed the pro-tobacco initiatives losing support while the health group campaigns generally maintained support and, in Ohio, increased support. Encouraged by the polls, the health groups were consistent in their messaging through the duration of their campaigns. By contrast, the pro-tobacco initiatives in Arizona and Ohio changed their public messaging in late October as polls showed public support for their initiatives waning (Figure 1). The messages from the pro-tobacco campaigns switched from promoting their initiatives to a “no” campaign against the health groups' initiatives, arguing that the health groups' “smoking bans” would harm the economy.20,21 Despite this last-minute change in strategy, the health groups' initiatives all passed and the pro-tobacco initiatives all failed (Table 1 and Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Polling and election results for competing antismoking initiatives in (a) Arizona, (b) Nevada, and (c) Ohio in 2006.

Note. Health group campaigns are represented by solid lines and pro-tobacco campaigns by dotted lines. Polls in September 2006 showed the competing initiatives in all 3 states passing. As the campaigns progressed, support for the health group campaigns stayed consistent while support for the pro-tobacco campaigns eroded.

Source. For Arizona data, see references 39–42; for Nevada data, see references 42–45; for Ohio data, see references 46–50.

Implementation

Following the passage of the health group initiatives, Arizona, Ohio, and Nevada had very different implementation experiences. Health groups in Arizona had worked extensively with the state's health department to plan for implementation and included a $0.02 per pack cigarette tax as part of the initiative for its funding, with any remaining funds allocated to Arizona's tobacco control program.21 As a result, implementation went smoothly there. In Ohio, the health groups had not coordinated with the state health department,20 which was completely unprepared to implement the initiative after it passed. This failure of planning and coordination led to a 5-month delay in the implementation of Ohio's new law while the health department finalized implementation rules. The American Cancer Society in Ohio also had to sue the health department to remove exemptions for private clubs that the health department tried to create in violation of the terms of the initiative.20

Health groups in Nevada also made the mistake of not coordinating implementation efforts with the state's regional health districts, which operate independently of one another to enforce state laws. In contrast to Ohio and Arizona, Nevada22 also had no experience in implementing local clean indoor air ordinances, as the state previously had preemption of local clean indoor air legislation. These circumstances, coupled with organized resistance from several sports bars and slot route operators, led to compliance issues with a few hospitality venues and ambiguous legal rulings in the Las Vegas area that, as of May 2008, had not been resolved. In areas of Nevada outside Las Vegas, the “smoke free” law quickly became self-enforcing, with high compliance. By May 2008, compliance in all 3 states was high.

DISCUSSION

While the tobacco industry had opposed statewide initiatives to implement smoking restrictions since the late 1970s7–9 and ran an unsuccessful effort to overturn California's state smoke-free workplace law with a “look-alike” law in 1994,7,23 the competing initiatives in Arizona, Ohio, and Nevada represented the first time pro-tobacco forces ran competing initiatives at the same time that health groups were trying to enact “smoke free” initiatives. The tobacco control campaigns effectively dealt with the confusion created by the counterinitiatives by (1) creating information “shortcuts” and clarifying the contest through associating the pro-health and pro-tobacco initiatives with each campaign's respective backers and (2) successfully communicating to voters that if they supported tobacco control they must also vote against the pro-tobacco initiative.

Voter Behavior and Competing Initiatives

By introducing competing initiatives portrayed as alternative “smoking bans” to generate confusion, pro-tobacco interests sought to capitalize on 2 independent aspects of voter behavior. First, when voters are confused or overwhelmed they tend to vote “no.”5,51,52 Second, voters tend to evaluate competing initiatives not against each other but against the status quo, which can sometimes result in the initiative that is farther from the population's preference receiving more votes.4

Voters, with help from campaigns, can understand very complicated ballots that include competing initiatives, such as when, in 1988, California voters faced 5 different competing initiatives on automobile insurance reform.6 In the end, only one proposal sponsored by the consumer activist group Voter Revolt (with consumer advocate Ralph Nader as their spokesperson) passed, while the other 4 initiatives (3 sponsored by the auto industry and 1 by trial lawyers) failed. On the basis of this experience, A. Lupia concluded that voters who possessed incomplete knowledge about the competing measures were still able to use available information “signals” or “shortcuts” to make well-informed decisions.6 Even though the voters did not fully understand the details of the competing initiatives, they were able to vote for the initiative that was closest to their personal preference by considering the reputation and outcome preference of each initiative's backer.

The clean indoor air initiatives backed by health groups in 2006 provided effective information signals and shortcuts to communicate which initiative was the authentic tobacco control measure. The effective use of the high public credibility of the American Cancer Society, American Lung Association, and American Heart Association, compared with the tobacco and gaming industries, allowed voters more easily to identify which initiative reflected their desired outcome. The strong public association of the campaign sponsors with the respective initiatives reduced confusion introduced by the competing pro-tobacco initiatives, as well as the deceptive campaign messaging that claimed the pro-tobacco initiatives were actually comprehensive tobacco control measures. The availability of information shortcuts helped voters become informed and avoid the confusion that frequently leads to public interest initiatives being defeated.

The pro-tobacco interests also hoped to exploit the tendency of voters to evaluate competing initiatives not against each other but against the status quo.4 This independent evaluation of each competing proposal can lead to passage of both initiatives, with the less popular but more moderate initiative receiving more votes.4 Numerous examples exist of such voter behavior. In 2004 in North Dakota, Fargo and West Fargo's local competing clean indoor air initiatives each received more than 50% of the vote, with the less restrictive measures receiving a greater majority in each city and thus becoming law.18,24,25 In 2006, the competing pro-tobacco clean indoor air initiatives threatened to defeat the health group initiatives by leveraging the voter tendency to evaluate competing initiatives in terms of the status quo. The health group campaigns effectively dealt with the pro-tobacco strategy and this aspect of voter behavior when they emphasized in their campaign messaging that if voters supported the health group initiatives, they also needed to vote against the pro-tobacco initiatives, effectively creating a head-to-head competition in the minds of voters.

Conclusion

Ballot initiatives are expensive and require political expertise, and the tobacco industry is a formidable political opponent. In addition to preparing to take on the superior financial resources and paid media efforts of the tobacco industry, health advocates should prepare for competing pro-tobacco initiatives. Future pro-tobacco competing initiatives will probably portray comprehensive clean indoor air laws as extreme and harmful to the economy, a factor health advocates must consider when deciding whether to use the ballot initiative to pass tobacco control laws.

Ballot initiatives should only be used as a last resort after legislative efforts have been exhausted. If health advocates do choose to mount a campaign, they should create effective information “shortcuts” and “signals” by associating their initiative with high-credibility health groups and frame the campaign as a head-to-head competition against the pro-tobacco counterinitiative. (Given the defeat of the RJ Reynolds–backed initiatives in Arizona and Ohio, it will be interesting to see if the company chooses to remain openly involved in similar efforts in the future.) In addition, health advocates should write initiatives in a way that anticipates the practicalities of implementation and work with the government agency responsible for implementation and enforcement.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (grant CA–61021). The funding agency played no role in the selection of the topic or preparation or review of the manuscript.

Human Participant Protection

This research was conducted in accordance with a protocol approved by the Committee on Human Research of the University of California, San Francisco. Informed consent was obtained from all interviewees.

References

- 1.Levy DT, Chaloupka F, Gitchell J. The effects of tobacco control policies on smoking rates: a tobacco control scorecard. J Public Health Manag Pract 2004;10:338–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henson R, Medina L, St Clair S, Blanke D, Downs L, Jordan J. Clean indoor air: where, why, and how. J Law Med Ethics 2002;30:75–82 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fichtenberg C, Glantz S. Effect of smoke-free workplaces on smoking behaviour: systemic review. BMJ 2002;325:1–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilbert MD, Levine J. Less can be more: conflicting ballot proposals and the highest vote rule. The Berkeley Electronic Press. 2007. Available at: http://law.bepress.com/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1975&context=alea. Accessed September 11, 2008

- 5.Bowler D, Donovan T. Demanding Choices: Opinion, Voting, and Direct Democracy. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press; 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lupia A. Shortcuts versus encyclopedias: information and voting behavior in California insurance reform elections. Am Polit Sci Rev 1994;88:63–76 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glantz S, Balbach E. Tobacco War: Inside the California Battles. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monardi F, Glantz SA. Are tobacco industry campaign contributions influencing state legislative behavior? Am J Public Health 1998;88:918–923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Givel M, Glantz S. Tobacco lobby political influence on US state legislatures in the 1990s. Tob Control 2001;10:124–134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glantz S. Achieving a smokefree society. Circulation 1987;76:746–752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Samuels B, Glantz S. The politics of local tobacco control. JAMA 1991;266:2110–2117 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Traynor M, Begay M, Glantz S. New tobacco industry strategy to prevent local tobacco control. JAMA 1993;270:479–486 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsoukalas T, Glantz S. The Duluth clean indoor air ordinance: problems and success in fighting the tobacco industry at the local level in the 21st century. Am J Public Health 2003;93:1214–1221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Givel M, Glantz S. Tobacco industry political power and influence in Florida from 1979 to 1999. Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education, University of California, San Francisco. 1999. Available at: http://repositories.cdlib.org/ctcre/tcpmus/FL1999. Accessed September 11, 2008

- 15.Nixon ML, Mahmoud L, Glantz SA. Tobacco industry litigation to deter local public health ordinances: the industry usually loses in court. Tob Control 2004;13:65–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Siegel M, Carol J, Jordan J, et al. Preemption in tobacco control: review of an emerging public health problem. JAMA 1997;278:858–863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Americans for Nonsmokers' Rights Preemption: tobacco control's #1 enemy. 1998. Bates no. 106004299/4305. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/kiz11c00. Accessed September 11, 2008

- 18.Americans for Nonsmokers' Rights Americans for Nonsmokers' Rights clean indoor air database. Available at: www.no-smoke.org. Accessed September 11, 2008

- 19.Filaroski PD No-smoking vote draws fire—puffers, opponents at odds over voter-approved measure. Florida Times-Union November 7, 2002. Available at: http://infoweb.newsbank.com. Accessed June 17, 2008

- 20.Tung G, Glantz S. Clean air now, but a hazy future: tobacco industry political influence and tobacco policy making in Ohio 1997–2007. San Francisco. 2007. Available at: http://repositories.cdlib.org/ctcre/tcpmus/Ohio2007. Accessed September 11, 2008

- 21.Hendlin YH, Barnes RL, Glantz SA. Tobacco Control in Transition: Public Support and Governmental Disarray in Arizona 1997–2007. San Francisco, CA: Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education; 2008. Available at: http://repositories.cdlib.org/ctcre/tcpmus/Arizona2007. Accessed September 11, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tung G, Glantz S. Swimming Upstream: Tobacco Industry Political Influence and Tobacco Policy Making in Nevada 1975–2008. San Francisco, CA: Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education; 2008. Available at: http://repositories.cdlib.org/ctcre/tcpmus/Nevada2008. Accessed September 11, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Macdonald H, Aguinaga S, Glantz SA. The defeat of Philip Morris' “California Uniform Tobacco Control Act”. Am J Public Health 1997;87:1989–1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.West Fargo may have two smoking ban proposals on ballot. Bismarck (North Dakota) Tribune August 14, 2004:8A. Available at: http://infoweb.newsbank.com. Accessed June 17, 2008

- 25.Associated Press Bar owners seek smoking ban exemptions. Grand Forks (North Dakota) Herald October 13, 2004:07. Available at: http://infoweb.newsbank.com. Accessed June 17. 2008

- 26.Mandel LL, Glantz SA. Hedging their bets: tobacco and gambling industries work against smoke-free policies. Tob Control 2004;13:268–276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dearlove J, Bialous S, Glantz S. Tobacco industry manipulation of the hospitality industry to maintain smoking in public places. Tob Control 2002;11:94–104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Payne TJ. Why RJ Reynolds supports Prop 206. Yes on 206. Available at: http://web.archive.org/web/20060823031149/www.yeson206.org/why-RJ-supports/index.php. Accessed January 2, 2009

- 29.Ling PM, Glantz SA. Nicotine addiction, young adults, and smoke-free bars. Drug Alcohol Rev 2002;21:101–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ling PM, Glantz SA. Why and how the tobacco industry sells cigarettes to young adults: evidence from industry documents. Am J Public Health 2002;92:908–916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sepe E, Glantz SA. Bar and club tobacco promotions in the alternative press: targeting young adults. Am J Public Health 2002;92:75–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sepe E, Ling PM, Glantz SA. Smooth moves: bar and nightclub tobacco promotions that target young adults. Am J Public Health 2002;92:414–419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Smoke Free Ohio Web site. Available at: http://web.archive.org/web/20070210092507/www.smokefreeohio.org/oh/about/movies/TVCommercials.aspx. Accessed January 2, 2009.

- 34. Yes on 206, Nonsmokers Protection Act [advertising flier]. Yes on 206 [Arizona pro-tobacco campaign], 2006.

- 35.Prop Pitzl MJ. 206's language smoky. Arizona Republic August 17, 2006. Available at: http://infoweb.newsbank.com. Accessed June 17, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arizona Secretary of State Campaign Finance Committee search results. Available at: http://www.azsos.gov/cfs/CommitteeSearchResults.aspx. Accessed August 6, 2008

- 37.Ohio Secretary of State Campaign finance reports. Columbus. Available at: http://www.sos.state.oh.us/SOS/Campaign%20Finance.aspx. Accessed September 11, 2008

- 38.Nevada Secretary of State Financial disclosure reports/ballot advocacy groups. Available at: http://sos.state.nv.us. Accessed December 19, 2007

- 39.Cronkite-Eight Poll. Arizona voters support smoking ban proposals. Tempe, AZ. September 28, 2006. Available at: http://www.azpbs.org/horizon/poll/2006/9–28-06.htm. Accessed June 17, 2008

- 40.Cronkite-Eight Poll. Proposition 201 favored over proposition 206. Tempe, AZ. October 24, 2006. Available at: http://www.azpbs.org/horizon/poll/2006/10–24-06.htm. Accessed June 17, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Northern Arizona University Rival anti-smoking measures neck-and-neck. Flagstaff, AZ. October 17, 2006. Available at: http://www4.nau.edu/srl/PressReleases/SRL%20Press%20Release%20-%20Races%20and%20Intiatives.pdf. Accessed January 2, 2009

- 42.Clifton G. Anti-smoking acts supported, poll says. Reno (Nevada) Gazette-Journal September 17, 2006:14A. Available at: http://infoweb.newsbank.com. Accessed June 17, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mullen FX. Gap gets slimmer on two questions—RGJ/News 4 poll: smoking initiatives. Reno Gazette-Journal. November 1, 2006:1A. Available at: http://infoweb.newsbank.com. Accessed June 17, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wells A. Poll: smoking measures lag. Las Vegas Review-Journal. November 3, 2006:1A. Available at: http://infoweb.newsbank.com. Accessed June 17, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Whaley S. Poll finds strong support for both anti-smoking initiatives. Las Vegas Review-Journal September 26, 2006:1A. Available at: http://infoweb.newsbank.com. Accessed June 17, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 46.The Columbus Dispatch Politics. Columbus Dispatch poll, September 24, 2006.

- 47.The Columbus Dispatch Politics. Columbus Dispatch poll, November 5, 2006.

- 48.Naymik M. Voters oppose slots, back $6.85 wage. Cleveland Plain Dealer October 1, 2006. Available at: http://infoweb.newsbank.com. Accessed June 17, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ray C. Bliss Institute of Applied PoliticsUniversity of Akron. Bliss Institute 2006 general election survey. October 11, 2006. Available at: http://www.uakron.edu/bliss/docs/FallPollReportFall2006draft2_2_.pdf. Accessed September 11, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Breckenridge T. Voters back smoking ban, higher wage, polls shows. Cleveland Plain Dealer November 5, 2006. Available at: http://infoweb.newsbank.com. Accessed June 17, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schultz J. The Initiative Cookbook: Recipes and Stories From California's Ballot Wars. San Francisco, CA: Democracy Center; 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stein EM. The California constitution and the counter-initiative quagmire. Hastings Constit Law Q 1993;21:143–188 [Google Scholar]