Abstract

BACKGROUND

Many patients with a positive fecal occult blood test (FOBT) do not undergo follow-up evaluations.

OBJECTIVE

To identify the rate of follow-up colonoscopy following a positive FOBT and determine underlying reasons for lack of follow-up.

DESIGN

It is a retrospective chart review.

PARTICIPANTS

The subject group consisted of 1,041 adults with positive FOBTs within a large physician group practice from 2004 to 2006.

MEASUREMENTS

We collected data on reasons for ordering FOBT, presence of prior colonoscopy, completed evaluations, and results of follow-up tests. We fit a multivariable logistic regression model to identify predictors of undergoing follow-up colonoscopy.

RESULTS

Most positive FOBTs were ordered for routine colorectal cancer screening (76%), or evaluation of anemia (13%) or rectal bleeding (7%). Colonoscopy was completed in 62% of cases, with one-third of these procedures identifying a colorectal adenoma (29%) or cancer (4%). Factors associated with higher rates of follow-up colonoscopy included obtaining the FOBT for routine colorectal screening (odds ratio (OR) 1.59, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.11–2.29) and consultation with gastroenterology (OR 1.99, 95% CI 1.46–2.72). Patients were less likely to undergo colonoscopy if they were older than 80 years old (OR 0.54, 95% CI 0.31–0.92), younger than 50 years old (OR 0.44, 95% CI 0.28–0.70), uninsured (OR 0.50, 95% CI 0.27–0.93), or had undergone colonoscopy within the prior five years (OR 0.32, 95% CI 0.23–0.44).

CONCLUSIONS

Clinical decisions and patient factors available at the time of ordering an FOBT impact performance of colonoscopy. Targeting physicians’ understanding of the use of this test may improve follow-up and reduce inappropriate use of this test.

KEY WORDS: colorectal cancer, cancer screening, quality of care, risk management, patient safety, fecal occult blood test

Colorectal cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death in the United States. In 2008, over 140,000 individuals will be diagnosed with colorectal cancer and almost 50,000 will die from the disease.1 Colorectal cancer screening via fecal occult blood testing, flexible sigmoidoscopy, or colonoscopy is strongly recommended for average risk adults over 50 years based on its ability to promote earlier identification of cancer and reduce colorectal cancer mortality.2–9

Colonoscopy has become favored over fecal occult blood testing as an initial screening modality among physicians,10 and is increasingly used.11 However, the evidence for the effectiveness of screening colonoscopy programs to reduce colorectal cancer mortality is limited,12 and patients continue to report a preference for fecal occult blood testing,13 with 15% of US adults having been screened via this modality in 2006.14 As a screening test for colorectal cancer, fecal occult blood testing is only effective when accompanied by a complete diagnostic evaluation of the colon via colonoscopy in the setting of a positive occult blood test.15 Unfortunately, many patients with a positive fecal occult blood test (FOBT) result do not undergo appropriate follow-up diagnostic evaluation.16–22 This failure to “close the loop” represents a significant lapse in care for these high risk patients, as up to 40% of patients with a positive fecal occult blood test result have either early colorectal cancer or a large adenoma identified on follow-up colonoscopy.9,23

The reasons for this gap in care for colorectal cancer screening are likely related to a combination of physician, patient, and systems factors. Physicians may not recommend appropriate follow-up testing to patients,17,18,24 patients may refuse further testing,18 or appropriate systems may not be in place to help clinicians identify abnormal test results and ensure appropriate follow-up.25 Implementing a program to increase appropriate follow-up testing requires detailed knowledge of the relative importance of all of these factors. However, most prior studies in this area relied on clinician or patient surveys, or small medical chart reviews, which are limited in their ability to simultaneously capture such details.

Our organization implemented a quality improvement program in 2006 designed to improve follow-up of positive fecal occult blood tests. This program first involved using electronic medical record data to identify all patients with a positive fecal occult blood test and no subsequent colonoscopy or office visit in the gastroenterology department. Primary care physicians received a report listing their patients meeting these criteria on a quarterly basis, along with a recommendation to refer the patients for either colonoscopy or an office visit with a gastroenterologist. However, this program relied entirely on automated data extracts without knowledge of clinical details, and ultimately the failure to follow-up on positive fecal occult blood tests remained a persistent threat to patient safety.

The goal of this study was to provide a large-scale, detailed assessment of the clinical management of positive fecal occult blood tests to inform the development of future quality improvement programs by 1) identifying the rate of colonoscopy performance following a positive fecal occult blood test among our patient population, and 2) determining underlying reasons for lack of appropriate follow-up.

METHODS

Study Setting

The study was conducted within a large, integrated, multi-specialty group practice with approximately 135 primary care physicians caring for 250,000 adult patients across 14 health centers in eastern Massachusetts. All physicians use a common electronic medical record system (Epic Systems, http://www.epicsys.com) that provides a complete representation of clinical care in a near paperless environment, including clinical notes, diagnostic and procedure codes, and laboratory, radiology, and pathology results. In addition, the system allows for computerized ordering of laboratory tests, procedures, and referrals. Six-specimen FOBT kits are processed in the central laboratory and coded test results are stored in the electronic record. Primary care physicians within the medical group are able to directly refer patients for colonoscopy without a prior office consultation with a gastroenterologist via an open-access scheduling system.26

Data Collection

All data for this study were obtained from the electronic medical record system, which has been used extensively in prior analyses of quality of care.27–31 We used automated data extracts to identify 1041 positive six-specimen FOBTs obtained from 1009 unique patients over 18 years of age between 01/01/2004 and 12/31/2006. The study authors (SKR, TS, TDS) performed chart reviews to identify the reason for ordering the FOBT, history of colonoscopy, proposed treatment plans (including endoscopic procedures, gastroenterology consultation prior to colonoscopy, or repeat FOBT), and eventual treatments and clinical findings. We also identified reasons documented by the evaluating physician for follow-up not being pursued or completed, including patient refusal, patient no longer receiving care within the practice group, or competing clinical conditions. Competing clinical conditions were defined as those cited by the evaluating physician as a reason to defer follow-up of the positive FOBT, including 1) new conditions felt to require more urgent evaluation, such as a new lung mass; 2) existing conditions felt to make follow-up colonoscopy unnecessary, as in the case of terminal illness; or 3) existing conditions that increase the risk of performing colonoscopy, such as symptomatic cardiovascular disease. We obtained data on patient age, sex, race, health insurance, and number of positive stool cards using automated data extracts from the electronic medical record system.

Data Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to assess rates of planned and completed interventions. We fit a multivariable logistic regression model with generalized estimating equations to identify significant predictors of performance of follow-up colonoscopy, with independent variables including patient sociodemographic features, number of positive stool cards, presence of prior colonoscopy, and involvement of gastroenterology consultation. This model was adjusted for repeated measures among patients with more than one positive fecal occult blood test during the study period ( = 32). All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.1. The study was approved by the Human Studies Committees at Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates and Partners Healthcare System.

RESULTS

We identified 36,944 fecal occult blood tests during the three-year study period, including 1,041 (3%) positive tests. Among patients with a positive FOBT, the majority was between the ages of 50 and 80, white, and insured through the Medicare program or commercial health plans (Table 1). Routine colorectal cancer screening was the most common indication for FOBT (76%), though evaluation of anemia (13%) and rectal bleeding (7%) were also common indications. In approximately one-third of cases, patients had undergone a colonoscopy prior to the positive FOBT.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients with Positive Fecal Occult Blood Tests

| Characteristic | (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| <50 years | 112 (11) |

| 50–80 years | 791 (76) |

| >80 years | 138 (13) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 507 (49) |

| Race | |

| White, Non-Hispanic | 667 (64) |

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 101 (10) |

| Asian | 67 (6) |

| Hispanic | 22 (2) |

| Other | 46 (4) |

| Missing | 138 (13) |

| Insurance | |

| Medicare | 480 (46) |

| Commercial | 464(45) |

| Self-pay | 65 (6) |

| Medicaid | 32 (3) |

| Reason for fecal occult blood test* | |

| Colorectal cancer screening (normal risk) | 740 (71) |

| Colorectal cancer screening (high risk)† | 52 (5) |

| Anemia | 131 (13) |

| Rectal bleeding | 76 (7) |

| Abdominal pain | 36 (4) |

| Previously positive fecal occult blood test | 23 (2) |

| Number of stool cards positive | |

| One | 633 (61) |

| Two | 189 (18) |

| Three | 210 (20) |

| Prior colonoscopy | |

| No prior colonoscopy | 651 (63) |

| Prior colonoscopy within 5 years | 349 (34) |

| Prior colonoscopy greater than 5 years prior | 41 (4) |

* Total is greater than 100% as patients could have more than one documented indication for the test

† High risk indicates family history of 1st degree relative with colorectal cancer (CRC) before age 60, two 1st degree relatives with CRC at any age, or inflammatory bowel disease

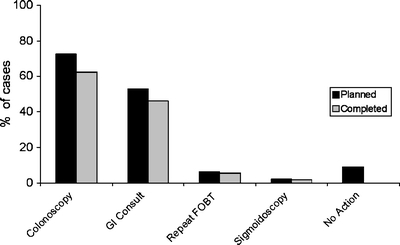

Colonoscopy was the most commonly planned (73%) action by primary care physicians following the positive FOBT, and was completed among 62% of all cases (Fig. 1). Gastroenterology consultation was recommended by primary care physicians in approximately one-half (53%) of patients. Among those patients evaluated by a gastroenterologist, the most common recommendations included colonoscopy (76%) and upper endoscopy (23%). Repeat FOBT was planned by primary care physicians in 6% of cases, while no follow-up plan was documented in 9% of cases.

Figure 1.

Planned and completed follow-up evaluations rates of planned and completed evaluations are indicated among 1,041 positive fecal occult blood tests.

Most planned evaluations were completed, including 86% of planned colonoscopies (Fig. 1). The majority (87%) of these colonoscopies was completed within 6 months of the positive FOBT, with nearly all (94%) being completed within one year. Patient refusal was the reason for a follow-up colonoscopy not being completed in only 7% of cases. Other reasons for failure to complete a follow-up colonoscopy included the patient no longer receiving care within the group practice (0.2%) and competing clinical conditions (3%). Among patients undergoing follow-up colonoscopy, nearly one-third (29%) had adenomatous polyps identified, and 4% were diagnosed with colorectal cancer (Table 2)

Table 2.

Findings Among 650 Patients Undergoing Colonoscopy

| Colonoscopy result | (%) |

|---|---|

| Normal | 107 (17) |

| Abnormal | |

| Hemorrhoids | 248(38) |

| Diverticulosis | 207(32) |

| Hyperplastic polyp | 109(17) |

| Arteriovascular malformation | 10 (2) |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 27 (4) |

| Adenomatous polyp | 186 (29) |

| Colorectal cancer | 28 (4) |

In multivariable models, patients older than age 80 years or younger than age 50, as well as those without health insurance were less likely to undergo follow-up colonoscopy; while black patients were more likely to undergo colonoscopy (Table 3). Clinical factors associated with completion of follow-up colonoscopy included gastroenterology consultation (odds ratio (OR) 1.99, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.46–2.72) and performance of fecal occult blood testing for routine screening (OR 1.59, 95% CI 1.11–2.29). In addition, the presence of a colonoscopy within 5 years prior to the positive FOBT test was strongly associated with not completing a follow-up colonoscopy (OR 0.32, 95% CI 0.23–0.44).

Table 3.

Predictors of Performance of Follow-up Colonoscopy‡

| Completed colonoscopy (%) | Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| Less than 50 | 67 (60) | 0.54 (0.31–0.92)† |

| 51–79 years | 523 (66) | REF |

| Greater than 80 | 60 (44) | 0.44 (0.28–0.70)† |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 330 (62) | REF |

| Male | 320 (63) | 0.96(0.72–1.30) |

| Race | ||

| White | 392 (59) | REF |

| Black | 80 (79) | 2.33 (1.33–4.10)† |

| Hispanic | 17 (77) | 2.04 (0.75–5.62) |

| Asian | 49(73) | 1.42 (0.79–2.56) |

| Other | 34 (73) | 1.64 (0.84–3.20)† |

| Insurance | ||

| Medicare | 284(59) | REF |

| Medicaid | 25 (78) | 1.64 (0.68–3.97) |

| Commercial | 317 (68) | 1.38 (0.98–1.95) |

| Self pay | 24 (37) | 0.50 (0.27–0.93)† |

| Reason for testing | ||

| Screening | 502 (66) | 1.59 (1.11–2.29)† |

| Non-screening* | 148 (52) | REF |

| Stool cards | ||

| One | 392 (62) | 0.78 (.52–1.16) |

| Two | 119 (62) | 0.88 (.70–1.13) |

| Three | 139 (65) | REF |

| Prior colonoscopy | ||

| No prior colonoscopy | 460 (71) | REF |

| Prior colonoscopy within 5 years | 162 (46) | 0.32 (0.23–0.44)† |

| Prior colonoscopy greater than 5 years ago | 29 (71) | 1.22 (0.57–.2.60) |

| Gastroenterology consult | ||

| Yes | 321 (67) | 1.99 (1.46–2.72)† |

| No | 329 (59) | REF |

* Includes anemia, abdominal pain, rectal bleeding, and follow-up of prior positive FOBT

† Indicates < 0.05

‡ Total sample included in multivariable models is 903 after excluding 138 patients with missing data on race/ ethnicity

DISCUSSION

We evaluated over 1,000 cases of positive FOBT tests during a 3-year period within a large health care system and found that in approximately one-third of cases, patients did not undergo follow-up colonoscopy. Among those patients that did complete colonoscopy, over one-third had an important clinical finding of colorectal cancer or colorectal adenoma, highlighting the importance of completing a diagnostic evaluation of the colon. Many factors associated with performing follow-up colonoscopy were related to the clinical decision-making process and known by the physician at the time of ordering the test, including patient age, reason for obtaining the test, and presence of a recent prior colonoscopy. This suggests that quality improvement programs to improve follow-up of positive fecal occult blood tests should include a focus on improving the indications for initial use of these tests, where we identified significant variation as well as strong predictors of performing follow-up colonoscopy.

Our findings are consistent with prior studies documenting the lack of colonoscopy performance following a positive FOBT.15–21 We examined a broad set of predictors, including patient and health system factors, as well as those related to the clinical decision-making process. While health systems may implicitly contribute to poor follow-up via the absence of systems to identify abnormal results requiring follow-up,32 our health system utilizes a system of quarterly feedback reports to physicians identifying patients in need of additional evaluation, lessening the impact of this issue. There have been concerns in the past regarding the capacity of the system to support the demand for colonoscopy,33 potentially leading to delays in appropriate evaluations. However, our data indicate a very high rate of completing colonoscopy once a procedure was ordered, and most colonoscopies were completed within six months. This finding is consistent with more recent analyses indicating that the US health system can support the demand for colonoscopy in the era of increased use of this procedure.34

Patient refusal has been commonly offered by physicians as a reason for low rates of follow-up colonoscopy.35 However, we found only a small minority of cases had a documented refusal of a recommended follow-up colonoscopy. While other studies have found that female patients were somewhat less likely to have follow-up colonoscopy performed,19 we did not identify this association. Other important patient characteristics did predict lack of appropriate follow-up in our study. Patients under 50 and over 80 years old in our study were less likely to undergo follow-up colonoscopy, potentially reflecting a decreased suspicion for significant disease among younger patients, or concerns about the expected benefits among the elderly. However, this calls into question the appropriateness of the initial test in these scenarios. Clinicians ordering FOBT should consider these characteristics and whether follow-up colonoscopy would be appropriate for a particular patient.

Prior studies relying on survey data have found that the physician clinical decision-making process is one of the strongest predictors of performing follow-up colonoscopy,18,19 and there is considerable variation in how physicians report dealing with a positive FOBT.24 Many physicians report a preference to perform follow-up testing that is not recommended by national guidelines, including repeat fecal occult blood testing or flexible sigmoidoscopy, as well as often recommending no further follow-up. Our study provides important insights into physician variability in clinical care using data obtained from routine clinical practice. In our sample of patients, ordering of colonoscopy by the primary care physician resulted in a completed colonoscopy 86% of the time, highlighting the extreme importance of physician recommendation. Similarly, referral to gastroenterology was associated with higher rates of colonoscopy, consistent with prior studies.20 This latter finding may reflect improved understanding of the importance of colonoscopy by patients after specialist consultation or better understanding of screening guidelines among specialists.

The variability in the clinical decision-making process is also evident in the reasons for ordering the FOBT. We found that this test was ordered for a range of non-screening purposes, consistent with a recent study suggesting that many FOBTs are ordered inappropriately.36 This includes their use in evaluation of anemia or rectal bleeding, which are more appropriately evaluated with direct visualization of the colon, particularly in older adults.37,38 Unfortunately, we found that performance of the fecal occult blood test for non-screening purposes was associated with failure to obtain a follow-up colonoscopy, perhaps underscoring the clinical ambiguity surrounding performance of the initial test.

In approximately one-third of cases in our study population, the patient had undergone colonoscopy within five years preceding the positive fecal occult blood test, and the majority of these patients did not undergo repeat colonoscopy. Performance of a FOBT was likely not indicated in these cases as current guidelines do not recommend such interval testing between screening colonoscopies.14 The unfortunate consequence of FOBT in this scenario is that it creates a situation where the optimal clinical avenue is not well defined, and may pose a risk management issue in the cases where a clinician may appropriately decide that a repeat colonoscopy is not warranted.

While our study is strengthened by the large number of patients and availability of complete clinical data, there are important limitations. The study was conducted within a single health system using an advanced electronic health record and disease registry system to notify physicians of positive test results, potentially limiting the generalizability of the findings. Clinical reminder systems directed towards providers have been demonstrated to improve the delivery of effective cancer screening services in a variety of settings.39 Therefore, the rates of colonoscopy following positive fecal occult blood tests may be higher in our system than in other settings. However, the most important findings related to indications for ordering fecal occult blood tests are likely common to most other primary care practice settings. In addition, our understanding of the clinical scenario was limited to what was documented in the medical record. However, this design allows insights beyond what may be reported in surveys of patients and physicians in this area. Finally, predictors of performing follow-up colonoscopy may vary within particular small subgroups, and further research using larger patient populations will be needed to understand these more nuanced variations in clinical care delivery.

In conclusion, our study identified a persistent gap in appropriate follow-up of positive FOBTs. Clinical factors, including the reason for performing the FOBT and the presence of a recent colonoscopy, strongly affected rates of appropriate follow-up, suggesting that physician clinical decision-making, rather than patient or system factors, plays an important role in the performance of follow-up colonoscopy. Future interventions to improve follow-up of positive FOBTs should focus on physician education regarding the appropriate use of these tests.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Amy Marston, BA for her efforts in data extraction and project management. This study was funded by a grant from the Harvard Risk Management Foundation. The funding agency played no role in design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. Dr. Sequist had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis

Conflict of Interest None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

This project was supported by a grant from the Harvard Risk Management Foundation and has not been previously published or presented in any form.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:71–96. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Mandel JS, Bond JH, Church TR, et al. Reducing mortality from colorectal cancer by screening for fecal occult blood. Minnesota Colon Cancer Control Study. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1365–71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Hardcastle JD, Chamberlain JO, Robinson MH, et al. Randomised controlled trial of faecal-occult-blood screening for colorectal cancer. Lancet. 1996;348:1472–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Kronborg O, Fenger C, Olsen J, Jorgensen OD, Sondergaard O. Randomised study of screening for colorectal cancer with faecal-occult-blood test. Lancet. 1996;348:1467–71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Selby JV, Friedman GD, Quesenberry CP Jr., Weiss NS. A case-control study of screening sigmoidoscopy and mortality from colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:653–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Ho MN, et al. Prevention of colorectal cancer by colonoscopic polypectomy. The National Polyp Study Workgroup. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1977–81. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.United States Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for colorectal cancer: recommendation and rationale. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:129–31. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Smith RA, von Eschenbach AC, Wender R, et al. American Cancer Society guidelines for the early detection of cancer: update of early detection guidelines for prostate, colorectal, and endometrial cancers. Also: update 2001-testing for early lung cancer detection. CA Cancer J Clin. 2001;51:38–75. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Winawer S, Fletcher R, Rex D, et al. Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance: clinical guidelines and rationale-Update based on new evidence. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:544–60. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Klabunde CN, Frame PS, Meadow A, Jones E, Nadel M, Vernon SW. A national survey of primary care physicians’ colorectal cancer screening recommendations and practices. Prev Med. 2003;36:352–62. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Gross CP, Andersen MS, Krumholz HM, McAvay GJ, Proctor D, Tinetti ME. Relation between Medicare screening reimbursement and stage at diagnosis for older patients with colon cancer. JAMA. 2006;296:2815–22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Whitlock EP, Lin JS, Liles E, Beil TL, Fu R. Screening for colorectal cancer: a targeted, updated systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:638–58. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.DeBourcy AC, Lichtenberger S, Felton S, Butterfield KT, Ahnen DJ, Denberg TD. Community-based preferences for stool cards versus colonoscopy in colorectal cancer screening. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:169–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Use of colorectal cancer tests-United States, 2002, 2004, and 2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:253–8. [PubMed]

- 15.Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, et al. Screening and Surveillance for the Early Detection of Colorectal Cancer and Adenomatous Polyps, 2008: A Joint Guideline From the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. Gastroenterology. 2008. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Levin B, Hess K, Johnson C. Screening for colorectal cancer. A comparison of 3 fecal occult blood tests. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:970–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Shields HM, Weiner MS, Henry DR, et al. Factors that influence the decision to do an adequate evaluation of a patient with a positive stool for occult blood. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:196–203. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Baig N, Myers RE, Turner BJ, et al. Physician-reported reasons for limited follow-up of patients with a positive fecal occult blood test screening result. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2078–81. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Turner B, Myers RE, Hyslop T, et al. Physician and patient factors associated with ordering a colon evaluation after a positive fecal occult blood test. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:357–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Etzioni DA, Yano EM, Rubenstein LV, et al. Measuring the quality of colorectal cancer screening: the importance of follow-up. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1002–10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Fisher DA, Jeffreys A, Coffman CJ, Fasanella K. Barriers to full colon evaluation for a positive fecal occult blood test. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:1232–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Lurie JD, Welch HG. Diagnostic testing following fecal occult blood screening in the elderly. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1641–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Ransohoff DF, Lang CA. Screening for colorectal cancer with the fecal occult blood test: a background paper. American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:811–22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Nadel MR, Shapiro JA, Klabunde CN, et al. A national survey of primary care physicians’ methods for screening for fecal occult blood. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:86–94. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Klabunde CN, Riley GF, Mandelson MT, Frame PS, Brown ML. Health plan policies and programs for colorectal cancer screening: a national profile. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10:273–9. [PubMed]

- 26.Charles RJ, Cooper GS, Wong RC, Sivak MV Jr., Chak A. Effectiveness of open-access endoscopy in routine primary-care practice. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:183–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Ayanian JZ, Sequist TD, Zaslavsky AM, Johannes RS. Physician Reminders to Promote Surveillance Colonoscopy for Colorectal Adenomas: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Sequist TD, Adams A, Zhang F, Ross-Degnan D, Ayanian JZ. Effect of quality improvement on racial disparities in diabetes care. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:675–81. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Pereira AG, Kleinman KP, Pearson SD. Leaving the practice: effects of primary care physician departure on patient care. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2733–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Sequist TD, Marshall R, Lampert S, Buechler EJ, Lee TH. Missed opportunities in the primary care management of early acute ischemic heart disease. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2237–43. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Sequist TD, Fitzmaurice GM, Marshall R, Shaykevich S, Safran DG, Ayanian JZ. Physician performance and racial disparities in diabetes mellitus care. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1145–51. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Poon EG, Gandhi TK, Sequist TD, Murff HJ, Karson AS, Bates DW. I wish I had seen this test result earlier!: Dissatisfaction with test result management systems in primary care. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:2223–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Seeff LC, Manninen DL, Dong FB, et al. Is there endoscopic capacity to provide colorectal cancer screening to the unscreened population in the United States? Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1661–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Ladabaum U, Song K. Projected national impact of colorectal cancer screening on clinical and economic outcomes and health services demand. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1151–62. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Klabunde CN, Vernon SW, Nadel MR, Breen N, Seeff LC, Brown ML. Barriers to colorectal cancer screening: a comparison of reports from primary care physicians and average-risk adults. Med Care. 2005;43:939–44. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Fisher DA, Judd L, Sanford NS. Inappropriate colorectal cancer screening: findings and implications. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2526–30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Capurso G, Baccini F, Osborn J, et al. Can patient characteristics predict the outcome of endoscopic evaluation of iron deficiency anemia: a multiple logistic regression analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:766–71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Lewis JD, Brown A, Localio AR, Schwartz JS. Initial evaluation of rectal bleeding in young persons: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:99–110. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Stone EG, Morton SC, Hulscher ME, et al. Interventions that increase use of adult immunization and cancer screening services: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:641–51. [DOI] [PubMed]