Abstract

Purpose

To determine whether high-resolution, high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) images of the tongue acquired with IDEAL-FSE (iterative decomposition of water and fat with echo asymmetry and least squares estimation) will provide comparable volumetric measures to conventional nonfat-suppressed FSE imaging and to determine the feasibility of estimating the proportion of lingual fat in adults using IDEAL-FSE imaging.

Materials and Methods

Healthy volunteers underwent magnetic resonance imaging of the tongue using both IDEAL-FSE and conventional FSE sequences. The tongue was manually outlined to derive both volumetric and fat fraction measures. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) were computed for intrarater measurement reliability and Spearman’s rank correlation tested the relationship between IDEAL-FSE and conventional volumetric measures of the tongue.

Results

IDEAL-FSE imaging yielded almost identical volumetric measures to that of conventional FSE imaging in the same amount of scan time (IDEAL-FSE mean 64.1 cm3; conventional mean 63.3 cm3; r = 0.988, P ≤0.01). The average fat signal fraction across participants was 26.5%. Intrarater reliability was excellent for all measures (ICC ≥ 0.92).

Conclusion

Our results indicate that IDEAL-FSE provided similar lingual volume estimates to conventional FSE imaging obtained in both the current and previous studies. IDEAL-FSE measures of lingual fat composition may be useful in studies that aim to increase lingual muscle strength and volume in swallowing and speech-disordered populations.

Keywords: fast spin echo, magnetic resonance imaging, water-fat separation, tongue, deglutition, sarcopenia

An estimated 18 million adults suffer from dysphagia (swallowing disorders) in the United States (1). This life-threatening condition frequently results in aspiration pneumonia, dehydration, and malnutrition. Elderly individuals are among the most common groups to suffer with dysphagia (2). Previous studies have indicated that nondysphagic older adults swallow more slowly, have both reduced range of lingual motion and lingual isometric pressures compared to younger adults and likely due to lingual sacropenia (age-related skeletal muscle loss and increased fat) (3-5). Thus, identification of decreasing muscle and increasing fat in the tongue may serve as a predictor for presbyphagia and provide useful clinical information about dysphagic individuals.

Previous MRI studies of the tongue have focused on detailing its gross morphology (6-8) and muscular architecture (9) in humans. Others have used MRI to estimate the volume of healthy and disordered human tongues at one timepoint (10,11) as well as pre- and post-treatment to estimate changes in lingual volume in a disordered population (12). No study, to date, has used MRI to quantify both lingual volume and lingual fat content within healthy adults, which could offer more useful clinical information about the effects of lingual sarcopenia (13) and atrophy (14) on lingual function during swallowing. Data gathered from healthy tongues will contribute to knowledge about the range of normalcy for lingual volume and composition, to which disordered populations can be compared. In addition, fat-suppressed contrast techniques may be used during MRI to improve tumor diagnosis in the tongue (15).

In this work a unique method for lingual tissue differentiation using a chemical shift based water–fat separation method, known as IDEAL-FSE (iterative decomposition of water and fat with echo asymmetry and least squares estimation), was examined (16-18). This method acquires three images at slightly different echo times and uses an iterative algorithm to estimate the local inhomogeneity in the magnetic field (B0). Phase shifts created by the field inhomogeneity are then demodulated from the three images and finally a least-squares pseudoinverse operation is performed to make final estimates of water and fat, free from the effects of field inhomogeneities.

Although IDEAL can use arbitrary echo spacing (16), it can achieve the best possible signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) performance equivalent to an effective signal averaging of three, so long as an optimal echo combination is used. The echo combination that maximizes the SNR performance occurs when the phase between water and fat is in quadrature (ie, π/2+πk, k = any integer) and the first and third echoes are acquired 2π/3 before and 2π/3 after the center echo, respectively (18). This effective averaging is equivalent to the SNR performance that would be obtained if the object contained only water or fat and the three images were averaged together. In addition, IDEAL-FSE does not require the overhead of a fat-saturation pulse, thereby increasing its acquisition efficiency compared to fat saturation methods (16,19). Practically, for FSE acquisitions, this will increase the number of available slices by ≈10%–30%, depending on the specific imaging parameters.

Water–fat “swapping” artifacts are common with chemical shift-based water–fat separation methods (20) due to the inherent ambiguity that occurs when pixels contain mostly water or fat: the signal from off-resonance water is indistinguishable from fat signal. To avoid this artifact, IDEAL-FSE uses a region-growing algorithm (21) that assumes that the field inhomogeneity map is spatially smooth across the image, an assumption commonly made with chemical shift-based water–fat methods (20,22,23). Finally, chemical shift artifact in the readout direction is corrected with IDEAL-FSE by shifting the fat image by the known chemical shift using standard sinc interpolation methods (24).

We hypothesized that IDEAL-fast-spin echo (FSE) imaging of adult human tongues would yield nearly identical volumetric measures to conventional-FSE imaging volumetric measures. As such, the purpose of this work is to determine whether high-resolution, high SNR images of the tongue acquired with IDEAL-FSE at 1.5T will provide comparable volumetric measures to conventional 1.5T nonfat-suppressed FSE imaging. In addition, this investigation will determine the feasibility of estimating the proportion of lingual fat in adults using IDEAL-FSE imaging.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Eleven healthy participants were recruited to participate in this study. All healthy participants were free of speech, swallowing, or otolaryngological abnormalities. All imaging was performed with the approval of our Institutional Review Board (IRB) and after obtaining informed consent. In addition, all data were handled in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

All scanning was performed on a 1.5T MRI scanner (TwinSpeed, GE Healthcare Technologies, Waukesha, WI) using a neurovascular head coil (MRI Devices, Gainesville, FL). Imaging scan parameters for both T2-weighted IDEAL-FSE and the conventional FSE acquisition included: 4500/50 TR/TE, 384 × 224 matrix, 20 × 11 cm field-of-view (FOV), 3.0 mm slice thickness (zero gap), 26 slices, ±42 kHz bandwidth, an echo-train-length (ETL) of 12. The resulting voxel dimensions were 0.5 × 0.9 × 3.0 mm3. All images were obtained in the coronal plane to ensure that the lateral aspects of the tongue are clearly visually differentiated from the teeth, unlike in sagittal planning where the teeth and tongue can be difficult to separate from one another depending on slice location. Product linear auto-shimming was used for all scans. In order to achieve the same SNR and scan time, three signal averages were used for conventional FSE imaging. IDEAL-FSE automatically provides an effective signal averaging of three. The total scan time for both sequences was 2 minutes 47 seconds. Conventional imaging was not fat-suppressed.

For IDEAL-FSE imaging, separate fat, water, and recombined (fat + water) images were reconstructed using an online reconstruction algorithm. Recombined images were corrected for chemical shift artifact in the readout direction by realigning the separated water and fat images to account for the chemical shift, which depends on imaging parameters and is easily calculated (24). Separate fat signal fractions were computed for T2-weighted IDEAL images by using Analyze software (Lenexa, KS) to perform a pixel-by-pixel division of fat signal by the total fat plus water signals [fat/(fat + water)].

Each participant was scanned in the supine position. Padding the head within the head coil minimized head movement. To reduce motion artifact due to intra-oral movements each participant was instructed to position the tongue-tip to the back of their front teeth and to avoid swallowing, speaking, or any tongue movement for the duration of the scans.

Data Analysis

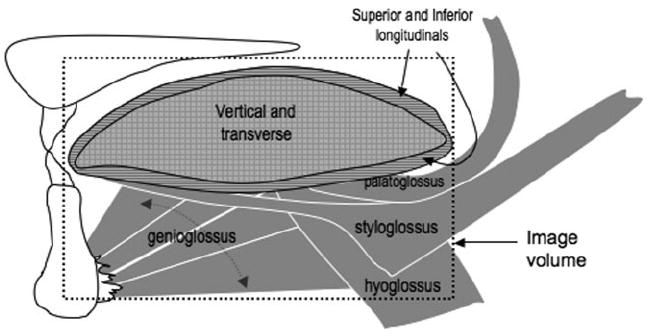

The tongue (lingual mucosa border) was manually outlined using Analyze software 6.0 for both the IDEAL-FSE and conventional FSE images. For IDEAL-FSE images, only the in-phase (water plus fat) recombined images were outlined. The body of the tongue is surrounded by dentition laterally and the hard palette superiorly. Because dentition and the hard palate are osseous structures, the soft tissue of the lingual border was clearly defined and facilitated data analysis within the oral cavity. Care was taken to exclude glandular tissue (sublingual, submandibular, and lingual tonsils) bilaterally, especially in posterior regions where it was more difficult to differentiate the tongue from other surrounding soft tissues. Total tongue volume was derived via summation of the individual slice areas multiplied by slice thickness. The outline of the tongue included all intrinsic muscles (vertical, transverse, superior, and inferior longitudinal) and extrinsic lingual muscles (genioglossus, hyoglossus, styloglossus, and palatoglossus). For extrinsic lingual muscles that have origins outside of the oral cavity (hyoglossus, styloglossus, and palatoglossus) only the aspects that joined the main body of the tongue were outlined and included in the analysis (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic of intrinsic and extrinsic lingual muscles included in the outline for analysis. The dotted-outlined box indicates the aspects of muscles that were included in the outline.

Statistical Analysis

To determine intrarater measurement reliability, 51 slices (11% of total outlined sample) that were evenly distributed across participants were reanalyzed for both conventional and IDEAL-FSE images. Only one rater outlined the images in this study. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) were computed for measures of volume and fat-fraction. The ICC represents the proportion of total variation (between-subject variability and measurement variability) that may be attributed to between-subject variability. Values near 1 suggest nearly all variability is essentially biological variance and not related to measurement, whereas values near 0 indicate that variability is primarily a result of measurement problems (25).

A Spearman’s rank correlation was used to test the direction and strength of the relationship between IDEAL-FSE and conventional volumetric measures of the tongue (SPSS v. 13.0, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

One participant was excluded from the study due to signal drop-out because the head coil would not fit completely over the head. Therefore, tongues from 10 healthy participants contributed to the results (six female; average age 31.3 years, age range 23–64, SD 12.3) (Table 1). Measurement reliability for conventional and IDEAL-FSE lingual volume showed ICCs of 0.98 and 0.92, respectively, and measurement reliability for fat fraction showed an ICC of 0.99.

Table 1.

Results Including Participant Demographics (Age, Sex), Volumetric Measures for Both IDEAL-FSE and Conventional Scanning, and Fat Fraction (Derived From IDEAL-FSE Images Only)

| Participants

|

Volume (cm3)

|

Fat Fraction (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Sex | Age | IDEAL | Conventional | |

| 1 | F | 26 | 52.0 | 50.8 | 22.6 |

| 2 | M | 32 | 56.9 | 55.9 | 30.1 |

| 3 | F | 23 | 58.1 | 56.4 | 27.6 |

| 4 | F | 37 | 58.7 | 59.1 | 24.8 |

| 5 | F | 27 | 60.0 | 60.4 | 21.0 |

| 6 | F | 64 | 65.4 | 64.6 | 31.5 |

| 7 | M | 24 | 69.1 | 67.1 | 29.7 |

| 8 | F | 31 | 72.2 | 70.2 | 23.8 |

| 9 | M | 26 | 72.1 | 73.1 | 25.3 |

| 10 | M | 23 | 76.6 | 75.8 | 28.4 |

| Averages: | 31.3 | 64.1 | 63.3 | 26.5 | |

| Std Deviations: | 12.3 | 8.1 | 8.2 | 3.5 | |

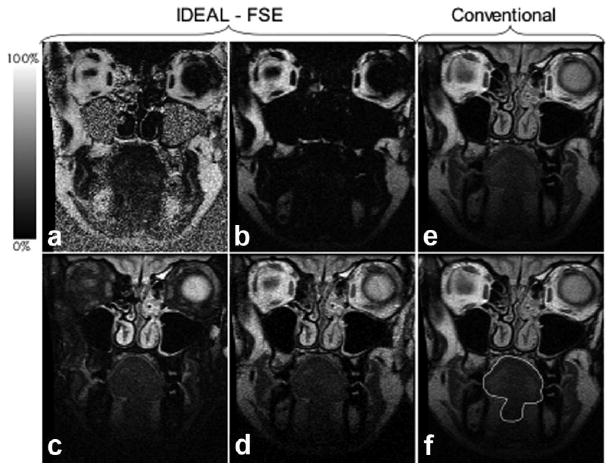

The entire tongue was completely imaged in 26 slices for each participant with a 20 × 11 cm FOV and 3 mm slice thickness. Participants reported relative ease with avoiding movement of their oral cavities for the duration of the scans, thus artifact due to movement was not problematic. IDEAL-FSE provided four separate images of the tongue (fat fraction, fat-only, water-only, and recombined fat + water) in the same scan time as conventional-FSE scans, which only provided nonfat-suppressed images (Fig. 2). Subjectively, the image quality of both IDEAL-FSE and conventional scans were deemed “very good” by a board-certified radiologist and two speech-language pathologists who are experienced with identifying structures of the oral cavity using MRI. There were subtle differences in the appearance of the images such that the IDEAL-FSE images showed slightly more blurring, which was likely due to increased echo spacing that leads to increased T2 decay during the echo train (26) (Fig. 2); however, the IDEAL-FSE scans easily allowed very good image analysis for tongue outlines. Because of the slight, but visible, differences in appearance, it was not possible to blind the analyst to the scanning technique. However, all IDEAL-FSE image analyses were completed several weeks before the onset of conventional image analyses and no adjustments were made to the original calculated volumetric measurements.

Figure 2.

T2-weighted IDEAL-FSE acquires separate fat fraction (a), fat (b) water (c), and recombined (d) images that were reconstructed using an online reconstruction algorithm, while conventional imaging only provides a nonfat-suppressed image (e). Manual outline of tongue shown in image (f).

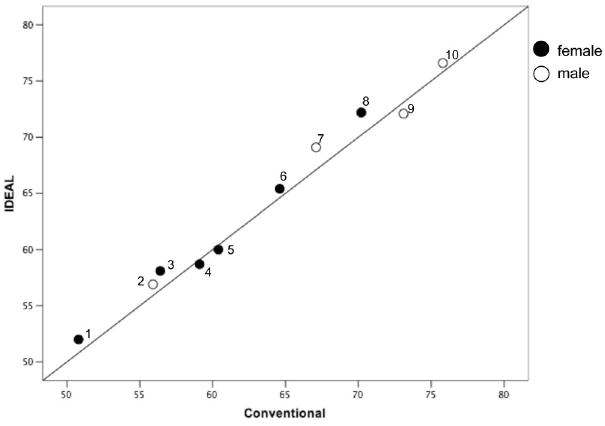

The average lingual volume across participants was 64.1 cm3 for IDEAL-FSE imaging (range 52–76.6 cm3, SD ± 8.1 cm3) and an average volume of 63.3 cm3 for conventional imaging (range 50.8–75.8 cm3, SD ± 8.2 cm3) (Table 1). The lingual volumetric measures for IDEAL-FSE and conventional images was highly correlated (r = 0.988; P ≤ 0.01) (Fig. 3). The average fat signal fraction across participants was 26.5% (range 21%–31.5%, SD ± 3.5%). On average, female participants had smaller lingual volumes for both IDEAL-FSE and conventional scans (60.7 cm3) and less fat signal fraction (25.2%) than male participants (volume 68.3 cm3, fat fraction 28.4%).

Figure 3.

Scatterplot shows lingual volumetric measures (Cartesian coordinates) from IDEAL-FSE and conventional images are highly correlated (r = 0.988; P ≤ 0.01).

DISCUSSION

The tongue is responsible for breaking food down in the mouth and for helping to initiate swallowing by forcefully propelling the material into the pharynx for ingestion. Because physiologic disorders of the tongue may be directly related to anatomic differences or abnormalities (ie, muscular dystrophy, Down syndrome, disuse atrophy), interventions that target the tongue are validated by quantitative measures of both lingual volume and composition. MRI is well suited to obtain such information in a relatively small amount of time.

One goal of the current study was to determine whether IDEAL-FSE imaging would result in lingual volume measures that were comparable to conventional FSE imaging. Our results indicated that IDEAL-FSE imaging yielded almost identical volumetric measures to that of conventional FSE imaging in the same amount of scan time. Although conventional images resulted in slightly better image resolution than IDEAL-FSE imaging, the difference did not affect similar delineation of the tongue during the analyses, as seen by very similar volumetric measures between the two scanning techniques. Estimates of lingual volume in the current study for both conventional and IDEAL-FSE imaging are on par with many previous studies that have used MRI to determine lingual volume (Table 2).

Table 2.

Lingual Volume Estimates of Previous Studies Using MRI Along With Estimates From the Current Study

| Reference, Year | Number of Participants | Average Volume (cm3) | Male Volume (cm3) | Female Volume (cm3) | Average Age | Slice Acquisition Orientation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lauder, 1991 | 19 (11 female) | 71.2 | 81.47 | 63.73 | Not provided | coronal and sagittal |

| Yoo, 1996 | 10 (all female) | 64.6 | N/A | 64.6 | 20 | coronal and sagittal |

| Ajaj, 2005 | 50 (25 female) | 97 | 117 | 77 | 58 | sagittal |

| Current study | 10 (6 female) | 64.5 | 72.3 | 60.7 | 31 | coronal |

Of perhaps even greater importance, the current study also aimed to determine the feasibility of IDEAL-FSE to estimate, in vivo, the fat content of the tongue. In 10 healthy adults the average fat content was 26.5%. Our results are comparable to a study of 16 human cadaver specimens that reported an average of 25.49% adipose tissue after anterior, middle, and posterior regions of the tongue were biopsied (27).

The use of IDEAL-FSE at 1.5T permitted acquisition of high-resolution images of the tongue in only 2 minutes 47 seconds. IDEAL-FSE provides very good SNR efficiency, resulting from the optimization of echo shifts, which produce the best possible SNR performance of the IDEAL-FSE water–fat separation method.

Previous studies have indicated that the presence of image artifact in the oral cavity due to dental work is dependent on the type of metal that was used (28). However, few participants knew which types of metals were left in their teeth after dental procedures. As such, the current study is limited by the inability to predict which types of permanent dental work would result in image artifact. Therefore, using MRI to estimate lingual volume or content may not be easily generalizable to those patients whose dental work is artifact-inducing and permanently fixed within the oral cavity. Participants were asked to minimize both gross movement of the head as well as movements of their tongues. Although none of the participants in the current study expressed difficulty remaining still during scanning, those with cognitive impairment or severe swallowing impairment who require frequent swallows to clear saliva may be challenging candidates for MRI of the tongue. Finally, the population sample in this study is small and not evenly distributed between males and females or young and old participants, therefore estimates of lingual volume and fat composition may be skewed.

In conclusion, our results indicate that IDEAL-FSE provided similar lingual volume estimates to conventional FSE imaging obtained in both the current and previous studies. In addition to lingual volume, IDEAL-FSE of the tongue provided estimates of fat composition, which can be useful in studies that aim to increase lingual muscle strength and volume in swallowing and speech-disordered populations, emphasizing its clinical relevance. Future studies should focus on IDEAL-FSE to determine whether significant differences exist in healthy old and young adults to answer important clinical questions about lingual sacropenia in the aged.

Acknowledgments

Contract grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health (NIH), NCRR; Contract grant sponsor: the Training and Education to Advance Multidisciplinary-Clinical-Research (TEAM) Program, K12 Roadmap, 8K12RR023268-02. 10/01/04 – 7/30/09.

Footnotes

Published online in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com).

References

- 1.ECRI E-BPC. Diagnosis and Treatment of Swallowing Disorders (Dysphagia) in Acute Stroke Patients. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; Jul, 1999. Report nr Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No 8 AHCPR Publication No 99-E024. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaw J. Dysphagia in the adult: its clinical significance, diagnosis and management. Part II. Br J Clin Pract. 1981;35:73–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robbins J, Hamilton JW, Lof GL, Kempster GB. Oropharyngeal swallowing in normal adults of different ages. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:823–829. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)90013-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robbins J, Levine R, Wood J, Roecker EB, Luschei E. Age effects on lingual pressure generation as a risk factor for dysphagia. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1995;50:M257–262. doi: 10.1093/gerona/50a.5.m257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans WJ. What is sarcopenia? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1995;50(Spec No):5–8. doi: 10.1093/gerona/50a.special_issue.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lufkin RB, Wortham DG, Dietrich RB, et al. Tongue and oropharynx: findings on MR imaging. Radiology. 1986;161:69–75. doi: 10.1148/radiology.161.1.3763886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sigal R, Zagdanski AM, Schwaab G, et al. CT and MR imaging of squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue and floor of the mouth. Radiographics. 1996;16:787–810. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.16.4.8835972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Unger JM. The oral cavity and tongue: magnetic resonance imaging. Radiology. 1985;155:151–153. doi: 10.1148/radiology.155.1.3975395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilbert RJ, Napadow VJ. Three-dimensional muscular architecture of the human tongue determined in vivo with diffusion tensor magnetic resonance imaging. Dysphagia. 2005;20:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s00455-003-0505-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lauder R, Muhl ZF. Estimation of tongue volume from magnetic resonance imaging. Angle Orthod. 1991;61:175–184. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1991)061<0175:EOTVFM>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoo E, Murakami S, Takada K, Fuchihata H, Sakuda M. Tongue volume in human female adults with mandibular prognathism. J Dent Res. 1996;75:1957–1962. doi: 10.1177/00220345960750120701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ajaj W, Goyen M, Herrmann B, et al. Measuring tongue volumes and visualizing the chewing and swallowing process using real-time TrueFISP imaging—initial clinical experience in healthy volunteers and patients with acromegaly. Eur Radiol. 2005;15:913–918. doi: 10.1007/s00330-004-2596-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robbins J, Gangnon RE, Theis SM, Kays SA, Hewitt AL, Hind JA. The effects of lingual exercise on swallowing in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1483–1489. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sonies BC, Almajid P, Kleta R, Bernardini I, Gahl WA. Swallowing dysfunction in 101 patients with nephropathic cystinosis: benefit of long-term cysteamine therapy. Medicine (Baltimore) 2005;84:137–146. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000164204.00159.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lenz M, Greess H, Baum U, Dobritz M, Kersting-Sommerhoff B. Oropharynx, oral cavity, floor of the mouth: CT and MRI. Eur J Radiol. 2000;33:203–215. doi: 10.1016/s0720-048x(99)00143-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reeder SB, Wen Z, Yu H, et al. Multicoil Dixon chemical species separation with an iterative least-squares estimation method. Magn Reson Med. 2004;51:35–45. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reeder SB, Pineda AR, Wen Z, et al. Iterative decomposition of water and fat with echo asymmetry and least-squares estimation (IDEAL): application with fast spin-echo imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2005;54:636–644. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pineda AR, Reeder SB, Wen Z, Pelc NJ. Cramer-Rao bounds for three-point decomposition of water and fat. Magn Reson Med. 2005;54:625–635. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hargreaves BA, Gold GE, Beaulieu CF, Vasanawala SS, Nishimura DG, Pauly JM. Comparison of new sequences for high-resolution cartilage imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2003;49:700–709. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glover GH, Schneider E. Three-point Dixon technique for true water/fat decomposition with B0 inhomogeneity correction. Magn Reson Med. 1991;18:371–383. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910180211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu H, Reeder SB, Shimakawa A, Brittain JH, Pelc NJ. Field map estimation with a region growing scheme for iterative 3-point water-fat decomposition. Magn Reson Med. 2005;54:1032–1039. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma J. Breath-hold water and fat imaging using a dual-echo two-point Dixon technique with an efficient and robust phase-correction algorithm. Magn Reson Med. 2004;52:415–419. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiang QS, An L. Water-fat imaging with direct phase encoding. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1997;7:1002–1015. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880070612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu H, R S, Shimakawa A, Gold GE, Pelc NJ, Brittain JH. Implementation and noise analysis of chemical shift correction for fast spin echo Dixon imaging. Proc ISMRM; Kyoto, Japan: 2004. p. 2686. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fleiss JL. The design and analysis of clinical experiments. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1999. pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farzaneh F, Riederer SJ, Pelc NJ. Analysis of T2 limitations and off-resonance effects on spatial resolution and artifacts in echo-planar imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1990;14:123–139. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910140112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller J, Watkin K, Chen M. Muscle, adipose, and connective tissue variations in intrinsic musculature of the adult human tongue. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2002;45:51–65. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2002/004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.New P, Rosen B, Brady T, et al. Potential hazards and artifacts of ferromagnetic and nonferromagnetic surgical and dental materials and devices in nuclear magnetic resonance imaging. Radiology. 1983;147:139–148. doi: 10.1148/radiology.147.1.6828719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]