Abstract

Objective

The role of osteoprotegerin (OPG) and its nuclear receptor ligand kappaB (RANKL) in the regulation of bone in humans remains unclear. We examined sex-specific associations of serum OPG, RANKL, and their ratio with bone mineral density (BMD) in older adults.

Design

Participants were 681 community-dwelling adults, ages 45-90 years, who had serum OPG and RANKL measured and bone density scans in 1988-91, with follow-up scans five and/or ten years later.

Methods

Analyses were sex-specific; women using and not using estrogen were evaluated separately. Cross-sectional analyses used multivariable regression models; longitudinal analyses used repeated measures mixed effects models.

Results

In cross-sectional analyses, age- and weight-adjusted serum OPG levels were significantly positively associated with BMD at the lumbar spine in men, and at the femoral neck, total hip, and lumbar spine in women using estrogen, but not in non-users of estrogen. RANKL concentrations were significantly and inversely associated with BMD in men only, and only at the total hip. Neither OPG nor RANKL was significantly associated with bone loss. Results for the RANKL/OPG ratio were the same as those for RANKL alone.

Conclusions

These results suggest a modulatory effect of both endogenous and exogenous sex hormones on the biologic interaction of OPG, RANKL, and bone.

Keywords: Aging, Bone mineral density, Estrogen, Osteoprotegerin, RANK ligand

INTRODUCTION

The OPG/RANKL/RANK system is thought to play a major role in the regulation of osteoclastogenesis and to be the chief mechanism by which osteoblast and osteoclast activity are coupled to coordinate bone formation and bone resorption (1, 2). Osteoprotegerin (OPG), a soluble receptor secreted by osteoblasts and other cell types, competitively binds nuclear receptor ligand kappaB (RANKL) expressed primarily on osteoblasts, preventing RANKL from binding to the receptor activator of nuclear factor kappaB (RANK) on osteoclasts (3).

In vitro studies have shown that, in the absence of OPG, RANKL binds to the RANK receptor, promoting the proliferation and differentiation of pre-osteoclasts and prolonging osteoclast survival by suppressing apoptosis (4–7). In the presence of OPG, osteoclast differentiation, activation, and survival are inhibited (4, 6). Variations in the balance of OPG and RANKL are thought to critically contribute to the pathology of osteoporosis and other bone diseases (4, 6).

The effects of alterations in the OPG/RANKL/RANK pathway have been demonstrated in genetic models. In OPG knockout mice, the number of osteoclasts is increased markedly and severe osteoporosis develops throughout the skeleton (8, 9, 4). Transgenic mice over-expressing OPG produce almost no osteoclasts and develop osteopetrosis (6, 4). Mice administered serum RANKL developed elevated levels of osteoclast growth and activation, leading to osteoporosis (2, 7). In humans, a mutant gene encoding OPG has been found; the mutant OPG produced by this gene fails to suppress bone resorption, resulting in severe bone deformities (10).

Published findings of serum OPG-bone mineral density (BMD) associations in humans have been inconsistent (11–16, 3, 17, 18), and few studies have assessed the associations of RANKL (19, 20, 18) and the RANKL/OPG ratio (21, 20) with BMD. To test the a priori hypotheses that OPG-BMD associations are positive and RANKL-BMD associations are negative in humans, we conducted a cross-sectional and prospective study of the associations of serum levels of OPG, RANKL, and their ratio with BMD in older men and postmenopausal women, stratified by use of estrogen.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population

Between 1988 and 1991, 82% (n=2,031) of surviving community-dwelling men and women from the Rancho Bernardo Study, a study of healthy middle to upper middle class ambulatory older Caucasian adults aged 45–90, participated in a baseline osteoporosis study visit. To be eligible for the present analysis, participants had to have returned for a third osteoporosis visit about 10 years after the baseline osteoporosis visit. Of the original osteoporosis study cohort, 1,095 (54%) died prior to the third osteoporosis visit. Of the remaining 936 participants, 681 (73%) had sufficient serum stored for analysis of serum OPG and RANKL levels and had one (n=52) or two (n=617) subsequent bone density scans. The surviving participants were younger, consumed alcohol more frequently, and exercised more frequently than those who did not participate. Each visit for this study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of California, San Diego. All participants gave written informed consent.

Measurements

Baseline age, medical history, and health habits were assessed using standardized questionnaires. Data on current health habits were dichotomized: current cigarette smoking (yes/no); alcohol consumption on three or more days per week (yes/no); exercise on three or more days per week (yes/no); and current estrogen use (yes/no). Smoking, exercise frequency, alcohol frequency, and current estrogen use were self-reported. In this cohort, self-reported lifestyle measures correlate with relevant measurements such as pulmonary function, pulse rate, HDL cholesterol, and liver function tests (22–24). Current estrogen use at baseline was validated by examination of pills and prescriptions brought to the clinic for that purpose.

BMD (g/cm2) of the femoral neck, total hip, and lumbar spine (L1–L4) was measured using dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) (Hologic QDR-1000; Hologic, Inc., Bedford, Massachusetts). Scans were standardized daily against a calibration phantom. Weight was measured using a balance beam scale with participants wearing light clothing and no shoes.

Serum from non-fasting blood samples obtained by venipuncture on the day of the baseline bone scan was separated and frozen at -70°C. OPG and RANKL were measured in 2004 at Amgen, Inc. in Thousand Oaks, California. Serum OPG levels were measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) commercial kit (Biomedica Gruppe, Vienna, Austria) that detects monomeric, dimeric, and ligand bound OPG. The published sensitivity of the assay was 2.8 pg/ml; the intra- and interassay coefficients of variation were 4–10% and 7–8%, respectively. RANKL levels were assayed using an ELISA (Biomedica Gruppe, Vienna, Austria) that detects soluble, uncomplexed human RANKL in serum. The manufacturer’s insert indicates that the ELISA can reliably detect values below 1.6 pg/ml using extrapolation. For the purposes of this study, values greater than 0.20 pg/ml were included in the analyses as measured; levels for 75 individuals (27 men and 48 women) with values below 0.20 pg/ml were set at 0.20 pg/ml for these analyses. The intra- and interassay coefficients of variation for RANKL were 3–5% and 6–9%, respectively.

Serum samples were stored at -70°C for up to 16 years before assay, and information regarding the effect of long-term storage are limited (25). However, OPG and RANKL data were available for a subset of 139 Rancho Bernardo participants at two different visits eleven years apart, providing samples assayed after five and 16 years of storage. There were no associations between storage duration and OPG or RANKL concentrations in these samples. Also, means and variances for OPG and RANKL concentrations did not differ between the two visits. Serum OPG and RANKL concentrations did not vary significantly with time of day of blood draw or number of hours since last dietary intake.

Statistical Analysis

All variables except OPG and RANKL levels were normally distributed. Natural log transformed OPG and RANKL values approximated normality and were used in all statistical analyses. OPG and RANKL data are presented as either the geometric mean or in standardized units to simplify interpretation. For all analyses, data were stratified into three comparison groups: men (n=307), women using estrogen at the baseline osteoporosis visit (n=173), and women not using estrogen at the baseline visit (n=201). The latter group included 106 prior estrogen users 85% of whom had stopped estrogen long enough (>1 year) for the protective effect of ET on BMD to reverse (26).

Descriptive statistics of the study cohort were summarized using means with 95% confidence intervals for continuous variables or proportions for dichotomous variables. Least squared means and the ordinary χ2 test were used to evaluate significant differences among the three comparison groups. Student’s t-test and the ordinary χ2 were used to compare characteristics of participants included in these analyses to those in the baseline osteoporosis cohort not included in the present study due to death prior to the third osteoporosis visit, lack of archived sera, or no subsequent bone scan.

Covariates were evaluated for incorporation in the OPG-BMD and RANKL-BMD models by testing individual associations with OPG and RANKL; correlations were used for continuous variables and least squared means were used for dichotomous variables. Covariates significantly associated with OPG or RANKL and BMD that changed the coefficient estimate of OPG or RANKL as a predictor of BMD by greater than 15% were considered confounding variables.

Multiple linear regression models were used to examine associations between OPG, RANKL, and their ratio with BMD. Models were evaluated unadjusted and by adding one covariate at a time. In adjusted models, regression diagnostics verified that data met normal regression assumptions including linearity, normality of residuals, and lack of collinearity. Additional adjustment for time of day of blood draw and number of hours since last dietary intake did not materially alter results.

Mixed-effects models for repeated measures were used to evaluate associations of baseline OPG and RANKL, with change in BMD between baseline and subsequent visits approximately five and ten years later. These models were adjusted for the same covariates used in the multilinear regression models.

All p-values were based on two-tailed significance, defined as p < .05. No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons, in order to reduce type 2 errors (27). All statistical analyses were conducted using the SAS system package (version 9.1, SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

Characteristics of Participants

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the 307 men and 374 women aged 45 to 90 years who participated in this study. More than 98% of women were postmenopausal. Men weighed more, had a higher BMD, and reported more frequent alcohol consumption than women. Women not using estrogen had the lowest BMD. OPG and RANKL levels did not differ significantly by sex or by women’s estrogen use status.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Study Participants 1988–1991; Rancho Bernardo, California

| Men (n=307) | Women Using ET (n=173) | Women Not Using ET (n=201) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean (95% CI) | mean (95% CI) | mean (95% CI) | p‑value | |

| Age (years) | 69.43 (68.53 ,70.34) | 66.45 (65.25 ,67.66) | 69.88 (68.76 ,71.00) | <.001 |

| Weight (kg) a | 81.2 (80.0 ,82.5) | 62.8 (61.2 ,64.5) | 65.4 (66.4 ,66.9) | <.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) a | 26.43 (26.04 ,25.82) | 24.33 (23.80 ,24.86) | 25.35 (24.88 ,25.84) | <.001 |

| OPG (pg/ml) b | 107.6 (101.8 ,113.7) | 114.5 (106.8 ,122.7) | 109.2 (102.7 ,116.3) | 0.410 |

| RANKL (pg/ml) b | 1.8 (1.5 ,1.9) | 1.6 (1.3 ,1.9) | 1.85 (1.56 ,2.1) | 0.542 |

| RANKL/OPG ratio b | 0.014 (0.011 ,0.018) | 0.009 (0.007 ,0.010) | 0.013 (0.010 ,0.017) | 0.092 |

| BMD: | ||||

| Hip: neck (g/cm2) b | 0.7452 (0.7315 ,0.7589) | 0.7102 (0.6900 ,0.7275) | 0.6727 (0.6573 ,0.6881) | <.001 |

| Hip: total hip(g/cm2) b | 0.9408 (0.9256 ,0.9561) | 0.8827 (0.8635 ,0.9020) | 0.8313 (0.8142 ,0.8585) | <.001 |

| Lumbar spine (L1–L4) (g/cm2) b | 1.0276 (1.0059 ,1.0494) | 1.0013 (0.9739 ,1.0287) | 0.922 (0.8975 ,0.9465) | <.001 |

|

| ||||

| % yes | % yes | % yes | p‑value | |

|

| ||||

| Current Smoking b | 7.1 | 9.8 | 7.5 | 0.551 |

| Current Alcohol use on 3 or More Days Per Week b | 59.2 | 52.0 | 42.8 | 0.001 |

| Current Exercise 3 or More Times Per Week b | 46.3 | 46.2 | 37.8 | 0.128 |

Abbreviations: ET, estrogen therapy, CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; OPG, osteoprotegerin; RANKL, nuclear factor ligand kappaB; BMD, bone mineral density; Data are means (95% CI) for continuous variables and proportions for dichotomous variables; values for OPG, RANKL and RANKL/OPG are geometric means.

Age adjusted;

Age and weight adjusted.

Associations of OPG and RANKL with Osteoporosis Risk Factors

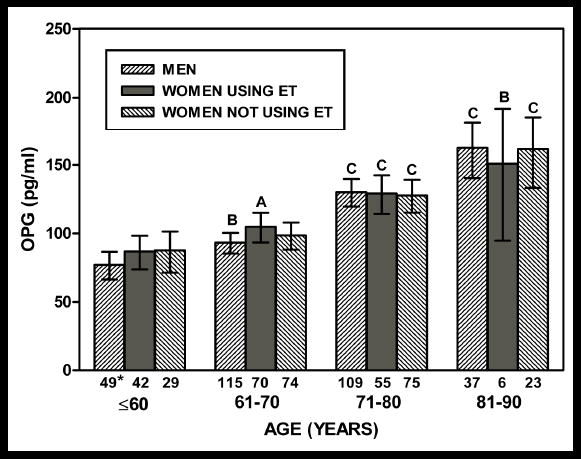

As shown in Figure 1, increasing age was associated with significantly higher OPG levels (overall p<.001) for all three comparison groups. Table 2 summarizes associations of OPG and RANKL with osteoporosis risk factors. For men only, OPG levels were lower for those who reported drinking alcohol three or more days per week compared to those who reported drinking less frequently or not at all (age adjusted geometric mean: 102.5 vs. 118.2 pg/ml, respectively, p=.001). For women using estrogen, OPG concentrations were higher for smokers compared to those who were past or never smokers (age adjusted geometric mean: 142.4 vs. 105.1 pg/ml, respectively, p=.012). Weight, BMI, and exercise frequency were not significantly associated with OPG.

Figure 1.

Baseline geometric mean OPG levels by age category for each study group; Rancho Bernardo, California, 1981–1991. Abbreviations: OPG, osteoprotegerin; ET, estrogen therapy. Ap<.05, Bp<.01, Cp<.001 versus age ≤60 years for the corresponding group; * sample size.

Table 2.

Correlations of Serum OPG and RANKL Levels with Covariates 1988–1991; Rancho Bernardo, California

| OPG (pg/ml) | RANKL (pg/ml) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men (n=307) | Women on Estrogen (n=173) | Women not on Estrogen (n=201) | Men (n=307) | Women on Estrogen (n=173) | Women not on Estrogen (n=202) | |

| Age (years) | 0.552* | 0.309* | 0.418* | -0.009 | -0.012 | 0.006 |

| Weight (pounds) a | -0.058 | 0.122 | -0.067 | 0.003 | -0.036 | 0.037 |

| BMI (m2/kg) a | -0.059 | 0.089 | -0.063 | -0.077 | -0.065 | 0.033 |

| RANKL (geometric mean) b | 0.024 | -0.010 | -0.136 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| OPG (geometric mean) b | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.024 | -0.010 | -0.136 |

Abbreviations: OPG, osteoprotegerin; RANKL, nuclear factor ligand kappaB; BMI, body mass index;

Age adjusted;

Age and weight adjusted;

P <.001

RANKL levels did not differ significantly by sex, age, weight, BMI, alcohol use, or exercise frequency among men or women. For men only, RANKL levels were higher for smokers compared to those who were past smokers or never smoked (age adjusted geometric mean: 1.9 vs. 0.9 pg/ml, respectively, p=.011).

The correlation of RANKL with the RANKL/OPG ratio was 0.93 (p<.001) and did not vary among the three study groups. The correlation of OPG with the ratio was -0.33 for men, -0.47 for women not using estrogen, and -0.36 for women using estrogen (all p <.001). There were no significant correlations between serum OPG and RANKL.

Associations of OPG, RANKL, and their Ratio with BMD

Table 3 summarizes results of multilinear regressions of OPG, RANKL, and their ratio with BMD. Higher levels of OPG were associated with higher BMD at the lumbar spine, femoral neck, and total hip for women using estrogen but not non-users. For men, higher OPG levels were associated with higher BMD only at the lumbar spine.

Table 3A.

β Coefficients for the Multiple Linear Regressions of Serum Levels of OPG and RANKL with baseline BMD for 307 Older Men, 1998–1991; Rancho Bernardo, California

| Men (n= 307) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Femoral Neck | Total Hip | Lumbar Spine | |||||||

| Models and Adjustments: | β | SE | p‑value | β | SE | p‑value | β | SE | p‑value |

| OPG | |||||||||

| age | 0.007 | .009 | .393 | -0.020 | .010 | .859 | 0.020 | .014 | .149 |

| age, weight, lifestylea | 0.012 | .008 | .135 | 0.005 | .010 | .549 | 0.033 | .013 | .012 |

| age, weight, lifestyle, RANKL | 0.012 | .008 | .133 | 0.006 | .009 | .539 | 0.033 | .013 | .011 |

| RANKL | |||||||||

| age, weight | 0.010 | .007 | .119 | -0.017 | .007 | .020 | -0.016 | .011 | .130 |

| age, weight, lifestyle | -0.012 | .006 | .065 | -0.017 | .007 | .015 | -0.017 | .011 | .092 |

| age, weight, lifestyle, OPG | -0.012 | .007 | 0.74 | -0.017 | .007 | .017 | -0.019 | .011 | .070 |

Abbreviations: OPG, osteoprotegerin; RANKL, nuclear factor ligand kappaB; BMD, bone mineral density; Values are standardized β coefficients; OPG and RANKL were log-transformed for analyses;

Lifestyle variables include current smoking (yes/no) and use of alcohol on 3 or more days per week (yes/no)

Higher RANKL levels were significantly associated with lower BMD at the total hip in men only; higher RANKL levels were also marginally associated with lower BMD at the femoral neck (p<.074) and lumbar spine (p<.069) in men, but only after adjustment for all covariates. No RANKL-BMD associations were observed in women. RANKL/OPG ratio associations with BMD were essentially the same as those for RANKL (data not shown).

Associations of OPG and RANKL with Changes in BMD

The annual percent change in BMD from baseline was significant for all three groups at all three bone sites. Rates of bone loss at the femoral neck and the total hip were not significantly different between men and women not using estrogen, but were significantly lower for women using estrogen (p<.001). All comparison groups had a net gain in bone at the lumbar spine, consistent with osteoarthritis. Baseline OPG and RANKL levels were not associated with change in BMD at any site for any of the three comparison groups.

DISCUSSION

In this cohort of older men and women, we found an independent, positive cross-sectional association of OPG with BMD at the lumbar spine, femoral neck, and total hip in women estrogen users, but not in women non-users of estrogen. In men, multiply adjusted OPG levels were associated with BMD at the lumbar spine only. Higher RANKL levels were significantly associated with higher BMD at the hip in men, but not women. Neither OPG nor RANKL predicted five to ten year change in BMD.

The absence of a positive association of OPG with BMD in women who were not using estrogen is concordant with five of six previous studies (3, 11, 21, 28, 14, 16). Only one prior study explicitly assessed women using estrogen. In that study of 490 postmenopausal women, OPG levels were higher in the 70 women who were using estrogen compared to those who were not, but no significant OPG-BMD associations were found in either group (16). Although OPG concentrations did not differ in estrogen-users versus non-users in our study, significant positive OPG-BMD associations were found at all bone sites for women using estrogen. These results are consistent with animal and in-vitro studies showing that higher levels of estrogen are associated with higher levels of OPG (6, 29–31) and that OPG inhibits osteoclast activity, resulting in less bone resorption (5, 8, 9, 6, 7, 32, 33).

Three of six previous studies (3, 15, 11, 20, 19, 13) reported positive OPG-BMD associations in men. In the present study, higher OPG levels were significantly associated with higher BMD at the lumbar spine after adjustment for covariates. No significant associations were observed at the femoral neck or total hip. Endogenous levels of estrogen and testosterone and their effects on OPG may be confounding the associations. In-vitro studies have shown that estrogen increases OPG while testosterone and the non-aromatizable androgen 5 alpha-dihydrotestosterone seemingly have the opposite effect (15, 29, 28, 34, 35). Alternatively, because of the number of associations evaluated, the OPG-spine BMD association only in men and only at a single bone site may be due to chance.

Although no RANKL-BMD associations were found for women, for men higher RANKL levels were significantly associated with lower BMD at the total hip and marginally associated with lower BMD at the femoral neck and lumbar spine. Two other studies have published RANKL-BMD associations in humans. One reported no association at the middle and distal phalanges in 566 men and women aged 18–75 years (19); the other reported an inverse association at the femoral neck in 80 Korean men aged 42–70 years (20). The inverse RANKL-BMD association for men in our study is in the predicted direction, given the expected function of RANKL.

An inverse RANKL-BMD association in men but not women raises the question whether testosterone mediates this association. One in-vitro study supports this thesis; the androgen dihydrotestosterone (derived from testosterone in human tissues) inhibited OPG mRNA levels and protein secretion by osteoblastic cells by up to 60% (34). However, testosterone had no effect on RANKL mRNA expression in a study of mouse bone cells (35), and no association between RANKL serum levels and testosterone was found in a study of 289 men (19) . Nevertheless, testosterone may indirectly mediate the RANKL-BMD association by acting on other modulators of the RANKL-RANK pathway. Older men have much higher estrogen levels than postmenopausal woman, but estrogen seems unlikely to be an important modulator of the RANKL-BMD association in that no association was observed in women using estrogen, who have circulating levels of estradiol similar to those in older men.

Standard levels of OPG and RANKL are not well-established (2). OPG levels reported here are within the wide range published in other studies. Mean values of OPG (for assays that detect all OPG forms) have ranged from 10 to 246 pg/ml (3, 15, 21, 14, 16), with the exception of one study reporting 1359 pg/ml and 1229 pg/ml for premenopausal and postmenopausal women, respectively (28). Wide ranges in reported values likely reflect differences in study populations, collection and storage methods, assay detection levels, and improved detection levels in newer assays (2). Consistent with earlier studies (3, 15, 11, 12, 13, 19, 28), we found higher serum OPG levels with increasing age, no sex differences in OPG, and no difference in serum RANKL levels by age or sex.

Most RANKL is cell bound and serum levels are low (7). Until recently, RANKL assays were not sensitive enough to detect levels for a large proportion of healthy individuals (21). One study reported that 55% of postmenopausal women had undetectable levels (21). Mean values using the less sensitive assays ranged from 7 pg/ml [3] to 26 pg/ml (21, 20, 36, 37). According to the manufacturer’s insert for the Biomedica, levels below 1.6 pg/ml can now be reliably detected. For the present study the detectable level of RANKL was set at 0.20 pg/ml. By these criteria, only 11% of the cohort had undetectable levels and the mean value of 1.73 pg/ml was therefore lower than that reported in other studies.

Baseline OPG and RANKL values were not associated with five to ten year change in BMD at the femoral neck, total hip, or lumbar spine in men or women. In the only other study of OPG and bone loss (11), OPG was not related to five year change in femoral neck or total hip BMD in 180 postmenopausal women. There are several reasons why serum OPG and RANKL levels measured at a single point in time may not predict change in BMD over time. First, because OPG levels increase with age, baseline values may reflect current bone status but not predict future bone loss. Second, while RANKL levels are relatively stable over time, the ability of RANKL to induce the RANK signaling system depends on levels of other modulators such as macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and the levels of these modulators are dynamic over time (2). Finally, some mediation of bone resorption occurs downstream of RANK and therefore is independent of OPG and RANKL levels at any single point in time (4).

This study has several strengths, including the community-dwelling cohort of relatively healthy ambulatory adults unselected for osteoporosis who were not using bone specific medications at baseline, the prospective design, quality controlled DXA scans, relatively large sample size, inclusion of both sexes, and validated hormone therapy use. Study limitations include the fact that OPG and RANKL are produced by many different cells, thus serum concentrations are not bone-specific (3, 38). In addition, circulating OPG and RANKL levels are low, difficult to measure, and may not reflect intracellular concentrations or activity. This might partially explain low or absent associations with BMD, but would not explain different associations by sex. Like all studies of older adults, healthy participant bias and survival bias were present. However, these biases were unlikely to contribute to the estrogen use specific OPG-BMD associations in women or to the significant inverse RANKL-BMD association only in men. Previous Rancho Bernardo studies have shown that poor renal function is associated with decreased BMD (39), whereas diabetes is associated with higher BMD (40). Measures of renal function and diabetes are not available at the baseline visit for this study, therefore the effect of the association of these two conditions on OPG and RANKL associations could not be examined. Because of the number of associations evaluated, some associations may be due to chance. Finally, the Rancho Bernardo cohort was comprised almost entirely of white, relatively well-educated, and middle or upper-middle class adults; results may not be generalizable to other ethnic or socioeconomic groups.

In conclusion, the selective association of OPG and BMD in women using estrogen suggests that exogenous estrogen may inhibit osteoclast activity indirectly by increasing OPG levels in the bone microenvironment, and is in line with laboratory studies showing a modulatory effect of estrogens on OPG-bone biology in females. Only men showed a significant RANKL-BMD association. This unexpected result may indicate a testosterone or other sex hormone effect on modulators of the RANKL-BMD system. More studies are needed to confirm these sex differences, to clarify their etiology, and to quantify the importance of OPG and RANKL on the RANK pathway relative to other mediators of osteoclast activity. Whether measurement of circulating levels of these cytokines will be clinically relevant is not yet clear.

Table 3B.

β Coefficients for the Multiple Linear Regressions of Serum Levels of OPG and RANKL with baseline BMD for 274 Postmenopausal Women, 1998–1991; Rancho Bernardo, California

| Women Using Estrogen (n= 173) | Women Not Using Estrogen (n= 201) | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Femoral Neck | Total Hip | Lumbar Spine | Femoral Neck | Total Hip | Lumbar Spine | |||||||||||||

| Models and Adjustments: | B | SE | p‑value | β | SE | p‑value | B | SE | p‑value | β | SE | p‑value | β | SE | p‑value | β | SE | p‑value |

| OPG | ||||||||||||||||||

| age | 0.022 | .008 | .008 | 0.023 | .009 | .010 | 0.035 | .012 | .005 | 0.000 | .007 | .930 | 0.010 | .009 | .225 | .005 | .012 | .684 |

| age, weight, lifestylea | 0.016 | .008 | .045 | 0.018 | .009 | .044 | 0.028 | .012 | .018 | 0.001 | .007 | .878 | 0.013 | .008 | .104 | 0.008 | .012 | .487 |

| age, weight, lifestyle, RANKL | 0.015 | .008 | .047 | 0.018 | .009 | .045 | 0.028 | .012 | .018 | 0.001 | .007 | .859 | 0.014 | .008 | .094 | 0.007 | .012 | .540 |

| RANKL | ||||||||||||||||||

| age | ||||||||||||||||||

| age, weight, lifestyle | 0.010 | .007 | .153 | 0.000 | .008 | .988 | -0.001 | .011 | .946 | 0.001 | .007 | .870 | 0.003 | .008 | .745 | -0.006 | .012 | .622 |

| age, weight, lifestyle, OPG | 0.010 | .007 | .157 | 0.001 | .008 | .917 | 0.003 | .011 | .819 | 0.010 | .007 | .846 | 0.003 | .008 | .610 | -0.007 | .012 | .581 |

Abbreviations: OPG, osteoprotegerin; RANKL, nuclear factor ligand kappaB; BMD, bone mineral density; Values are standardized β coefficients; OPG RANKL were log-transformed for analyses;

Lifestyle variables include current smoking (yes/no) and use of alcohol on 3 or more days per week (yes/no)

Acknowledgments

The study was funded by a grant by the National Institution of Health on Aging: AG07181. The serum OPG and RANKL assays were run by Stephen Adamu and Frank Suncion at Amgen, Inc. (Thousand Oaks, California).

Footnotes

Funding: Supported by research grant AG07181 from the National Institute on Aging. Amgen, Inc. (Thousand Oaks, California) ran the serum OPG and RANKL assays.

Conflict of Interest: Amgen, Inc. paid for and ran the OPG and RANKL assays. Elizabeth Barrett-Connor is a consultant to an Amgen-sponsored registry designed to study patient compliance with bone-specific medications or hormone therapy. Neither of these activities influenced this manuscript and there is no conflict of interest. All other authors have no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Anna Stern, Email: astern@ucsd.edu.

Jaclyn Bergstrom, Email: jbergstrom@ucsd.edu.

Elizabeth Barrett-Connor, Email: ebarrettconnor@ucsd.edu.

References

- 1.Khosla S. Minireview: the OPG/RANKL/RANK system. Endocrinology. 2001;142:5050–5055. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.12.8536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rogers A, Eastell R. Circulating osteoprotegerin and receptor activator for nuclear factor kappaB ligand: clinical utility in metabolic bone disease assessment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:6323–6331. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kudlacek S, Schneider B, Woloszczuk W, Pietschmann P, Willvonseder R. Serum levels of osteoprotegerin increase with age in a healthy adult population. Bone. 2003;32:681–686. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(03)00090-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hofbauer LC, Heufelder a E. Role of receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB ligand and osteoprotegerin in bone cell biology. J Mol Med. 2001;79:243–253. doi: 10.1007/s001090100226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yasuda H, Shima N, Nakagawa N, Yamaguchi K, Kinosaki M, Mochizuki S, Tomoyasu A, Yano K, Goto M, Murakami A, Tsuda E, Morinaga T, Higashio K, Udagawa N, Takahashi N, Suda T. Osteoclast differentiation factor is a ligand for osteoprotegerin/osteoclastogenesis-inhibitory factor and is identical to TRANCE/RANKL. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:3597–3602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simonet WS, Lacey DL, Dunstan CR, Kelley M, Chang MS, Luthy R, Nguyen HQ, Wooden S, Bennett L, Boone T, Shimamoto G, Derose M, Elliott R, Colombero A, Tan HL, Trail G, Sullivan J, Davy E, Bucay N, Renshaw-Gegg L, Hughes TM, Hill D, Pattison W, Campbell P, Sander S, Van G, Tarpley J, Derby P, Lee R, Boyle WJ. Osteoprotegerin: a novel secreted protein involved in the regulation of bone density. Cell. 1997;89:309–319. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80209-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lacey DL, Timms E, Tan HL, Kelley MJ, Dunstan CR, Burgess T, Elliott R, Colombero A, Elliott G, Scully S, Hsu H, Sullivan J, Hawkins N, Davy E, Capparelli C, Eli A, Qian YX, Kaufman S, Sarosi I, Shalhoub V, Senaldi G, Guo J, Delaney J, Boyle WJ. Osteoprotegerin ligand is a cytokine that regulates osteoclast differentiation and activation. Cell. 1998;93:165–176. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81569-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bucay N, Sarosi I, Dunstan CR, Morony S, Tarpley J, Capparelli C, Scully S, Tan HL, Xu W, Lacey DL, Boyle WJ, Simonet WS. osteoprotegerin-deficient mice develop early onset osteoporosis and arterial calcification. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1260–1268. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.9.1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mizuno A, Amizuka N, Irie K, Murakami A, Fujise N, Kanno T, Sato Y, Nakagawa N, Yasuda H, Mochizuki S, Gomibuchi T, Yano K, Shima N, Washida N, Tsuda E, Morinaga T, Higashio K, Ozawa H. Severe osteoporosis in mice lacking osteoclastogenesis inhibitory factor/osteoprotegerin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;247:610–615. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cundy T, Hegde M, Naot D, Chong B, King A, Wallace R, Mulley J, Love DR, Seidel J, Fawkner M, Banovic T, Callon KE, Grey a B, Reid IR, Middleton-Hardie CA, Cornish J. A mutation in the gene TNFRSF11B encoding osteoprotegerin causes an idiopathic hyperphosphatasia phenotype. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:2119–2127. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.18.2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Indridason OS, Franzson L, Sigurdsson G. Serum osteoprotegerin and its relationship with bone mineral density and markers of bone turnover. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16:417–423. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1699-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yano K, Tsuda E, Washida N, Kobayashi F, Goto M, Harada A, Ikeda K, Higashio K, Yamada Y. Immunological characterization of circulating osteoprotegerin/osteoclastogenesis inhibitory factor: increased serum concentrations in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:518–527. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.4.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Szulc P, Hofbauer LC, Heufelder a E, Roth S, Delmas PD. Osteoprotegerin serum levels in men: correlation with age, estrogen, and testosterone status. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:3162–3165. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.7.7657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rogers A, Saleh G, Hannon RA, Greenfield D, Eastell R. Circulating estradiol and osteoprotegerin as determinants of bone turnover and bone density in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:4470–4475. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khosla S, Arrighi HM, Melton LJ, 3rd, Atkinson EJ, O′fallon WM, Dunstan C, Riggs BL. Correlates of osteoprotegerin levels in women and men. Osteoporos Int. 2002;13:394–399. doi: 10.1007/s001980200045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Browner WS, Lui LY, Cummings SR. Associations of serum osteoprotegerin levels with diabetes, stroke, bone density, fractures, and mortality in elderly women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:631–637. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.2.7192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schett G, Kiechl S, Redlich K, Oberhollenzer F, Weger S, Egger G, Mayr A, Jocher J, Xu Q, Pietschmann P, Teitelbaum S, Smolen J, Willeit J. Soluble RANKL and risk of nontraumatic fracture. Jama. 2004;291:1108–1113. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.9.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abrahamsen B, Hjelmborg JV, Kostenuik P, Stilgren LS, Kyvik K, Adamu S, Brixen K, Langdahl BL. Circulating amounts of osteoprotegerin and RANK ligand: genetic influence and relationship with BMD assessed in female twins. Bone. 2005;36:727–735. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trofimov S, Pantsulaia I, Kobyliansky E, Livshits G. Circulating levels of receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB ligand/osteoprotegerin/macrophage-colony stimulating factor in a presumably healthy human population. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004;150:305–311. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1500305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oh KW, Rhee EJ, Lee WY, Kim SW, Baek KH, Kang MI, Yun EJ, Park CY, Ihm SH, Choi MG, Yoo HJ, Park SW. Circulating osteoprotegerin and receptor activator of NF-kappaB ligand system are associated with bone metabolism in middle-aged males. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2005;62:92–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2004.02179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mezquita-Raya P, De La Higuera M, Garcia DF, Alonso G, Ruiz-Requena ME, De Dios Luna J, Escobar-Jimenez F, Munoz-Torres M. The contribution of serum osteoprotegerin to bone mass and vertebral fractures in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16:1368–1374. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-1844-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frette C, Barrett-Connor E, Clausen JL. Effect of active and passive smoking on ventilatory function in elderly men and women. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;143:757–765. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reaven PD, Mcphillips JB, Barrett-Connor EL, Criqui MH. Leisure time exercise and lipid and lipoprotein levels in an older population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1990;38:847–854. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1990.tb05698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greendale GA, Barrett-Connor E, Edelstein S, Ingles S, Haile R. Lifetime leisure exercise and osteoporosis. The Rancho Bernardo study. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;141:951–959. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan BY, Buckley KA, Durham BH, Gallagher JA, Fraser WD. Effect of anticoagulants and storage temperature on the stability of receptor activator for nuclear factor-kappa B ligand and osteoprotegerin in plasma and serum. Clin Chem. 2003;49:2083–2085. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2003.023747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gallagher JC, Rapuri PB, Haynatzki G, Detter JR. Effect of discontinuation of estrogen, calcitriol, and the combination of both on bone density and bone markers. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:4914–23. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rothman KJ. No adjustments are needed for multiple comparisons. Epidemiology. 1990;1:43–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oh KW, Rhee EJ, Lee WY, Kim SW, Oh ES, Baek KH, Kang MI, Choi MG, Yoo HJ, Park SW. The relationship between circulating osteoprotegerin levels and bone mineral metabolism in healthy women. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2004;61:244–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2004.02090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saika M, Inoue D, Kido S, Matsumoto T. 17beta-estradiol stimulates expression of osteoprotegerin by a mouse stromal cell line, ST-2, via estrogen receptor-alpha. Endocrinology. 2001;142:2205–2212. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.6.8220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hofbauer LC, Khosla S, Dunstan CR, Lacey DL, Spelsberg TC, Riggs BL. Estrogen stimulates gene expression and protein production of osteoprotegerin in human osteoblastic cells. Endocrinology. 1999;140:4367–4370. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.9.7131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Michael H, Harkonen PL, Vaananen HK, Hentunen TA. Estrogen and testosterone use different cellular pathways to inhibit osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:2224–2232. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsuda E, Goto M, Mochizuki S, Yano K, Kobayashi F, Morinaga T, Higashio K. Isolation of a novel cytokine from human fibroblasts that specifically inhibits osteoclastogenesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;234:137–142. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yasuda H, Shima N, Nakagawa N, Mochizuki SI, Yano K, Fujise N, Sato Y, Goto M, Yamaguchi K, Kuriyama M, Kanno T, Murakami A, Tsuda E, Morinaga T, Higashio K. Identity of osteoclastogenesis inhibitory factor (OCIF) and osteoprotegerin (OPG): a mechanism by which OPG/OCIF inhibits osteoclastogenesis in vitro. Endocrinology. 1998;139:1329–1337. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.3.5837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hofbauer LC, Hicok KC, Chen D, Khosla S. Regulation of osteoprotegerin production by androgens and anti-androgens in human osteoblastic lineage cells. Eur J Endocrinol. 2002;147:269–273. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1470269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen Q, Kaji H, Kanatani M, Sugimoto T, Chihara K. Testosterone increases osteoprotegerin mRNA expression in mouse osteoblast cells. Horm Metab Res. 2004;36:674–678. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-826013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eghbali-Fatourechi G, Khosla S, Sanyal A, Boyle WJ, Lacey DL, Riggs BL. Role of RANK ligand in mediating increased bone resorption in early postmenopausal women. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1221–1230. doi: 10.1172/JCI17215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hawa G, Brinskelle-Schmal N, Glatz K, Maitzen S, Woloszczuk W. Immunoassay for soluble RANKL (receptor activator of NF-kappaB ligand) in serum. Clin Lab. 2003;49:461–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Makhluf HA, Mueller SM, Mizuno S, Glowacki J. Age-related decline in osteoprotegerin expression by human bone marrow cells cultured in three-dimensional collagen sponges. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;268:669–672. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jassal SK, von Muhlen D, Barrett-Connor E. Measures of renal function, BMD, bone loss, and osteoporotic fracture in older adults: the Rancho Bernardo study. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:203–10. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.061014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barrett-Connor E, Holbrook TL. Sex differences in osteoporosis in older adults with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 1992;16:3333–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]