Abstract

The differential recruitment of coregulatory proteins to the DNA-bound estrogen receptor α (ERα) plays a critical role in mediating estrogen-responsive gene expression. We previously isolated and identified retinoblastoma-associated proteins 46 (RbAp46) and 48 (RbAp48), which are associated with chromatin remodeling, histone deacetylation, and transcription repression, as proteins associated with the DNA-bound ERα. We now demonstrate that RbAp46 and RbAp48 interact with ERα in vitro and in vivo, associate with ERα at endogenous, estrogen-responsive genes, and alter expression of endogenous, ERα-activated and -repressed genes in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Our findings reveal that RbAp48 limits expression of estrogen-responsive genes and that RbAp46 modulates estrogen responsiveness in a gene-specific manner. The ability of RbAp46 and RbAp48 to interact with ERα and influence its activity reveals yet another role for these multifunctional proteins in regulating gene expression.

Keywords: estrogen receptor, RbAp46, RbAp48, retinoblastoma-associated protein, transcription

INTRODUCTION

The recruitment of coactivator and corepressor proteins to DNA-bound transcription factors plays a critical role in regulating gene expression. Coactivators increase transcription by remodeling chromatin, enhancing histone acetylation, and increasing the accessibility of DNA to transcription factors and their associated coregulatory proteins (Collingwood et al., 1999). In contrast, corepressors decrease transcription by remodeling chromatin, deacetylating histones, and making DNA less accessible (Dobrzycka et al., 2003). Paradoxically, some coregulatory proteins can function as both transcriptional activators and repressors in a gene specific and/or cell type specific manner (Fernandes and White, 2003; Peterson et al., 2007; Rao et al., 2008; Schultz-Norton et al., 2006; Schultz-Norton et al., 2007).

Extracellular signals can be initiated at the plasma membrane and propagated through cytoplasmic signal transduction cascades to initiate changes in transcription. Alternatively, lipophilic hormones can enter the cell and elicit their effects by activating intracellular ligand-activated nuclear receptor superfamily members. One of these superfamily members, estrogen receptor α (ERα), is activated by its lipophilic ligand, 17β-estradiol (E2). Upon binding hormone, the receptor undergoes a conformational change, interacts with estrogen response elements (EREs) in target DNA, and recruits coregulatory proteins that influence estrogen-responsive gene expression. The cohort of coregulatory proteins recruited to the ERE-bound ERα depends on the ligand bound, the ERE sequence, and the population of proteins expressed in the cell (Loven et al., 2001; Loven et al., 2001; Schultz et al., 2005; Wood et al., 1998; Wood et al., 2001). ERα-induced changes in gene expression have profound effects on reproductive, mammary, cardiovascular, neural, and skeletal cell function (Couse and Korach, 1999; Dubal et al., 1999; Wise et al., 2001).

To better understand how estrogen-responsive genes are regulated, we used agarose gel mobility shift assays and mass spectrometry analysis to isolate and identify novel proteins associated with the ERE-bound ERα (Curtis et al., 2007; El Marzouk et al., 2007; Schultz-Norton et al., 2007; Schultz-Norton et al., 2006; Schultz-Norton et al., 2007). Two of the proteins isolated in these proteomic screens were the highly homologous retinoblastoma associated protein 46 (RbAp46) and retinoblastoma associated protein 48 (RbAp48). As their names imply, RbAp46 and RbAp48 were originally isolated as part of a protein complex associated with the retinoblastoma protein (Nicolas et al., 2000; Qian and Lee, 1995; Qian et al., 1993). Subsequent studies identified RbAp46 and RbAp48 as histone binding proteins and components of protein complexes involved in histone deacetylation and chromatin remodeling (Ahringer, 2000; Bowen et al., 2004; Knoepfler and Eisenman, 1999; Zhang et al., 1997). Interestingly, some components of these chromatin remodeling complexes are known to interact with ERα (Cui et al., 2006; Laherty et al., 1998; McKenna and O'Malley, 2002; Privalsky, 2004; Talukder et al., 2003).

Although the amino acid sequences of RbAp46 and RbAp48 are highly homologous, these two proteins do have biochemically distinct activities. While RbAp46 associates with other proteins involved in the acetylation of newly synthesized histones (Parthun, 2007; Verreault et al., 1998), RbAp48 is an essential subunit of a protein complex involved in loading histones onto newly replicated DNA (Hoek and Stillman, 2003). Interestingly, the dysregulation of both RbAp46 and RbAp48 has been linked to carcinogenesis of a number of tissues including the breast and cervix (Guan et al., 2001; Thakur et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2003). Given the role of RbAp46 and RbAp48 in transcription regulation and carcinogenesis, we investigated whether RbAp46 and RbAp48 might influence ERα-mediated gene expression in MCF-7 breast cancer cells.

MATERIALS and METHODS

Identification of RbAp46 and RbAp48

RbAp46 and RbAp48 were isolated and identified as proteins associated with the ERE-bound ERα using agarose gel shift assays and mass spectrometry analysis as described previously (Curtis et al., 2007; El Marzouk et al., 2007; Schultz-Norton et al., 2007; Schultz-Norton et al., 2006; Schultz-Norton et al., 2007). Two peptides that contained amino acid sequence unique to RbAp46 (KIWKKNTPFL YDLVMTHALQ WPSLTVQWLP EVTKPEGK and EVTKPEGKDY ALHWLVLGTH TSDEQNHLVV AR), 4 peptides that contained amino acid sequence unique to RbAp48 (NTPFLYDLVMT HALEWPSLTAQ WLPDVTRPE GKD, GEFGGFGSVS GKIEIEIK, YGLSWNPNLS GHLLSASDDH TICLWDISAVPK, and TIFTGHTAVV EDVSWHLLHE SLFGSVADDQ), and 2 peptides that contained amino acid sequence present in both RbAp46 and RbAp48 (TPSSDVLVFDYTK and LNVWDLSKI) were identified in two independent experiments.

Immunocytochemical Analysis

MCF-7 cells were cultured on coverslips in phenol red free MEM with 5% charcoal dextran treated calf serum (CDCS). Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, washed with PBS, dehydrated in a series of graded ethanols, and rehydrated with PBS washes. Samples were incubated in blocking solution (PBS with 3% BSA and 0.1% Triton X-100) with 5% normal donkey serum for 10 min at room temperature and then incubated with blocking solution containing 5% normal donkey serum or an ERα specific antibody (1:1000, sc8002, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) along with an RbAp46 (1:1000, ab3535, Cambridge, MA) or RbAp48 (1:1000, ab1765, Cambridge, MA) specific antibody overnight at 4°C. All samples were incubated with a biotin-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:200, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) for 30 min at room temperature and then a Cy-3 conjugated streptavidin (1:200, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) along with an anti-mouse FITC conjugated antibody (1:100, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) for 30 min at room temperature. PBS washes were conducted after each of the antibody incubations. Coverslips were mounted using Vectashield mounting media containing 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) to visualize the nuclei. Images were obtained using a Leica (Nussloch, Germany) DM2500 microscope fitted with a QImaging Retiga 2000R camera (QImaging, Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada). Overlays were created using QCapture software (QImaging, Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada).

Western Blot Analysis

Proteins were fractioned on 15% denaturing acrylamide gels and detected with antibodies directed against ERα (sc-8002, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), RbAp46 (ab-3535 Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA or sc-8272, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), RbAp48 (ab-1765 Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA or sc-12434, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), β-actin (A-5491, Sigma, St. Louis, MO), or GAPDH (Anti-GAPDH antibody, Open Biosystems, Huntsville, AL). Horseradish peroxidase conjugated secondary antibodies (Zymed, San Francisco, CA) and Super Signal West Femto Chemiluminescent detection kit (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, IL) were used to visualize the proteins.

GST Pulldown Assays

The RbAp46 expression vector pGEM-RbAp46, the RbAp48 expression vector pGEM-RbAp48 (Qian et al., 1993), which were generous gifts from Bruce Stillman (Cold Spring Harbor, NY) or the parental GST expression vector was used to transform BL21-Codon Plus (DE3)RIPL competent cells (Stratagene, LaJolla, CA). 0.25 mM Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside was used to induce protein expression for 3 hrs. Bacteria were pelleted, resuspended in TEGN-500 (20mM Tris, pH7.9, 2 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 500 mM NaCl, and 5 mM DTT), sonicated on ice, and spun at 142,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. The supernatant was incubated with glutathione sepharose 4B beads (Amersham BioSciences/ GE HealthCare, Piscataway, NJ) for 1–2 hrs at 4°C, washed three times with TEGN-500 buffer, and then washed three times with interaction buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 10 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM Na2VO4, 50 mM NaF, 0.5% IGEPAL, and 1X protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, St. Louis, MO)). Proteins were eluted with glutathione elution buffer (3% glutathione solution w/v in 20 mM Tris, pH7.9) and protein purity was monitored on Coomassie stained gels. Protein concentrations of the eluates were determined with the Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, CA) using BSA as a standard. For each reaction, 100 µg of nuclear extract prepared from MCF-7 cells that had been treated with ethanol vehicle or 10 nM E2 as described (Wood et al., 2001) was combined with ~8 µg of immobilized protein in interaction buffer for a final volume of 500 µl and incubated overnight at 4°C. Beads were washed three times with interaction buffer and eluted with 2X SDS loading buffer (100 mM Tris, pH 6.8, 200 mM dithiothreitol, 4% SDS, 0.2% bromophenol blue, 20% glycerol) for 10 min at 24°C. Eluted proteins were subjected to Western blot analysis to determine if ERα was present.

Immunoprecipiation Assays

MCF-7 cells, which had been obtained from Benita Katzenellenbogen (University of Illinois, Urbana, IL), were maintained in phenol red containing minimal essential medium (MEM) with 5% calf serum in 15 cm culture dishes. Three days prior to treatment, cells were transferred to phenol red free MEM with 5% CDCS and grown to 95% confluency. Cells were exposed to ethanol vehicle or 10 nM E2 for 20 min, washed with cold Hanks Balanced Salt Solution, and lysed in 1 ml of cold interaction buffer. Whole cell extracts were subjected to centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C to remove insoluble material. Whole cell lysate (~4 mg) was combined with 1 µg of rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), RbAp46 specific antibody (ab-3535 Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA), or RbAp48 specific antibody (ab-1765, Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA) in interaction buffer for a final volume of 500 µl and incubated overnight at 4°C while mixing. The immune complexes were collected using 40 µl of a 50% protein A agarose bead slurry (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) for 3–4 hrs at 4°C while mixing. The beads were washed three times with interaction buffer and proteins were eluted with 2X SDS loading buffer for 10 min at 24°C and subjected to Western blot analysis.

RNA Interference assays

MCF-7 cells were maintained in phenol red-containing MEM with 5% calf serum and transferred to phenol red free MEM with 5% CDCS for 24 hrs. Cells were plated in 12 well plates at 4×105 cells/well in phenol red free MEM with 5% CDCS without antibiotics, grown for 24 hrs, and transfected with luciferase control, RbAp46 specific, or RbAp48 specific siRNA oligos (Silencer siRNA #4630, RBBP7#142450, or RBBP4#142864, respectively, Ambion, Austin, TX) using siLentFect (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After 24 hrs, medium was replaced with phenol red free and antibiotic free MEM with 5% CDCS supplemented with ethanol vehicle or 10 nM E2 and cells were incubated for 24 hrs. Four independent experiments were performed.

For RNA analysis, cells were harvested with Trizol (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and RNA was isolated according to the manufacturer’s instructions and treated with RQ1 RNase free DNase (Promega, Madison, WI). cDNA was synthesized using the Reverse Transcription System (Promega, Madison, WI). The cDNA and iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Richmond, CA) were combined with primers specific for RbAp46 (5’- GCT GTT GTA GAG GAT GTG G-3’ and 5’- CGG CTT GGA GGT GGT ATT G -3’), RbAp48 (5’- TGA CCA TAC CAT CTG CCT GTG -3’ and 5’- ACT GCC GTA TGC CCT GTA AAG -3’), PR (5’- GTG CCT ATC CTG CCT CTC AAT C -3’ and 5’- CCC GCC GTC GTA ACT TTC G -3’), pS2 (5’- GCT GTT TCG ACG ACA CCG TT-3’ and 5’- TTC TGG AGG GAC GTC GAT G-3’), cyclin G2 (5’- GCT GTT GTA GAG GAT GTG G -3’ and 5’- CGG CTT GGA GGT GGT ATT G -3’), Sox9 (5’- ATG TTT CAG CAG CCA ATA AGT G -3’ and 5’- AGG TGA CAG AGC GAG CAG -3’ ), ERα (5’-TGC CCT ACT ACC TGG AGA AC-3’ and 5’CCA TAG CCA TAC TTC CCT TGT C-3’) or 36B4 (5’-GCT GTT TCG ACG ACA CCG TT-3’ and 5’- TTC TGG AGG GAC GTC GAT G-3’) and quantitative real time PCR was carried out in a Bio-Rad iCycler. Standard curves were derived from serial dilutions of cDNA equivalent to 125, 250, 500, and 1000 ng input RNA and were run in duplicate with each primer set.

For protein analysis, cells were harvested in TNE (40 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 140 mM NaCl, and 1.5 mM EDTA), pelleted, resuspended in 250 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.8, lysed using three freeze/thaw cycles, and subjected to centrifugation to pellet insoluble debris. Whole cell extracts (30 µg) were subjected to Western blot analysis to determine the levels of RbAp46, RbAp48 (ab-3535), and GAPDH.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Assays

MCF-7 cells were maintained in phenol red containing MEM with 5% calf serum. Cells were transferred to phenol red free MEM with 5% CDCS four days prior to treatment. MCF-7 cells were exposed to ethanol vehicle or 10 nM E2 for 45 min or 4 hrs and treated with formaldehyde. Immunoprecipitation of chromatin was carried out essentially as described by Millipore (Charlottesville, VA) except that 1) pelleted cells were washed three times in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2 and 0.5% Nonidet P-40), resuspended in lysis buffer with 10 mM CaCl2 and 4% Nonidet P-40, and treated with 50 U micrococcal nuclease (USB, Cleveland, OH) for 10 min before sonication, 2) samples were digested with proteinase K (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for a minimum of 2 hrs according to manufacturer’s recommendations after immunoprecipitation, and 3) crosslinking was reversed with an overnight incubation at 65°C in the absence of salt. Immunoprecipitation of the chromatin was carried out with a fluorescein-specific antibody (Immunological Resource Center, University of Illinois, Urbana, IL) as a negative control, an ERα-specific antibody SC-8002 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Santa Cruz, CA), an RbAp46 specific antibody (ab-3535, Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA) or an RbAp48 specific antibody (ab-1765, Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA). ChIP DNA was analyzed using real time quantitative PCR. Primers specific to the Sox9 downstream ERE (5’- TGG CAA ACT TTC CGT TCC TAT G -3’ and 5’- GCT TCT CTC TGG TTC CCT GTA G -3’) or the pS2 imperfect ERE (5’- CCC GTG AGC CAC TGT TGT C -3’ and 5’- CCT CCC GCC AGG GTA AAT AC -3’) were combined with iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Richmond, CA) and used for quantitative PCR on a Bio-Rad iCycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Richmond, CA). 1,000, 5,000, 10,000, 50,000, and 100,000 genomic DNA copies were run in parallel with each primer set during each experiment to derive a standard curve. The relative copy number for each sample was determined from the standard curve for the three replicate samples. Five independent experiments were performed.

RESULTS

RbAp46 and RbAp48 are localized to the nucleus

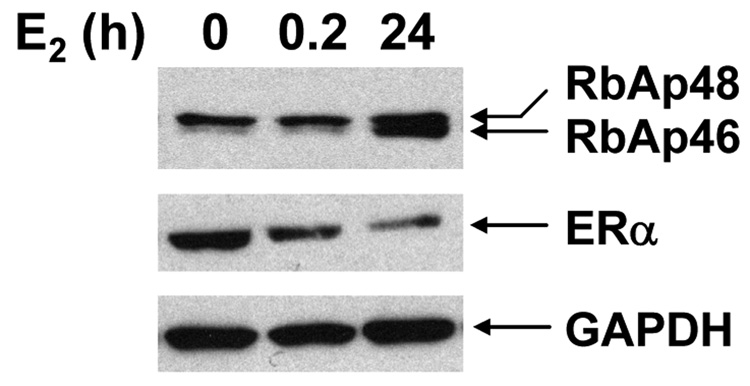

The expression of RbAp46 and RbAp48 was examined in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. As shown in the Western analysis shown in Fig. 1, RbAp46 expression was significantly lower than RbAp48 in the absence of hormone and after cells had been treated with E2 for 20 min. However, the expression of RbAp46 increased significantly (2.6-fold ± 0.7, p < 0.001) when cells were treated with E2 for 24h. There was no apparent difference in RbAp48 expression in the presence or absence of E2. In contrast to the increased expression of RbAp46, expression of ERα decreased significantly when MCF-7 cells had been treated with E2 for 24h. A GAPDH specific antibody was used to confirm that the lanes were equally loaded.

Fig. 1. Expression of RbAp46 and RbAp48.

Whole cell extracts were prepared from MCF-7 breast cancer cells that had been treated with ethanol or 10 nM E2 for the indicated times and subjected to Western analysis with antibody directed against RbAp46 and RbAp48, ERα or GAPDH. The blot shown is representative of six independent experiments.

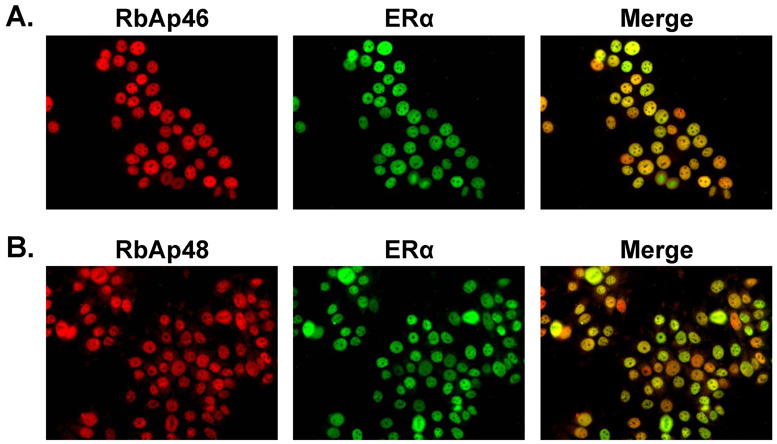

To determine whether RbAp46, RbAp48, and ERα were localized in the same cellular compartment and might be able to interact, immunohistochemical analysis was performed. ERα was present in the nuclei as expected and colocalized with RbAp46 and RbAp48 (Fig. 2). Thus, RbAp46, RbAp48, and ERα were localized in the nuclear compartment. Additional studies demonstrated that the distribution of these proteins was not altered by the presence of E2 (data not shown).

Fig. 2. Localization of RbAp46, RbAp48, and ERα in MCF-7 cells.

MCF-7 cells, which were maintained in a hormone-free environment, were fixed with formaldehyde and incubated with an antibody directed against ERα, RbAp46 (A) or RbAp48 (B). ERα (green) and RbAp proteins (red) are shown individually and as merged ERα, RbAp images (yellow). Control cells, which had not been exposed to primary antibody, are included as inserts. DAPI was used to visualize MCF-7 nuclei. Results are representative of multiple fields in three independent experiments.

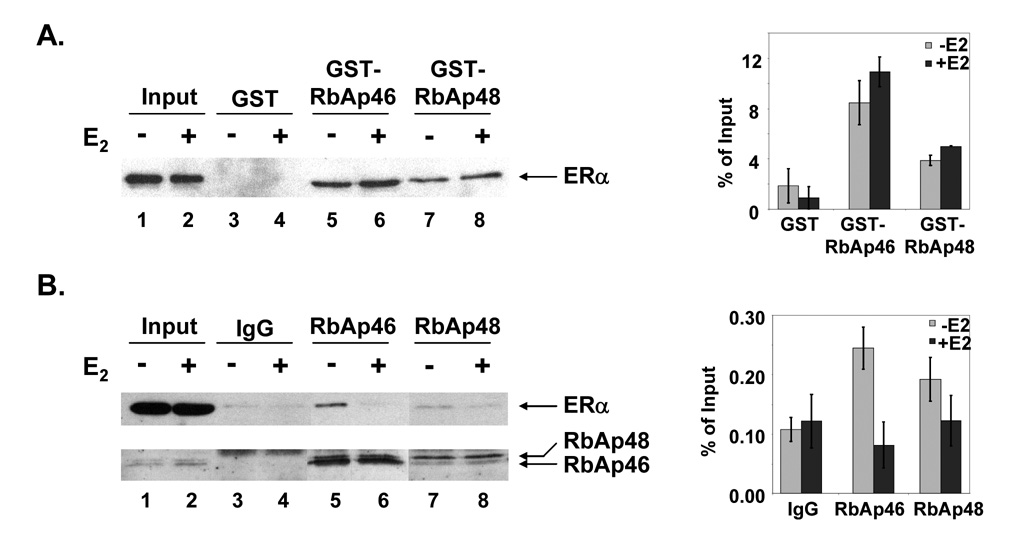

RbAp46 and RbAp48 interact with ERα

Since RbAp46 and RbAp48 were originally isolated as components of a large complex associated with the DNA-bound ERα (Curtis et al., 2007; El Marzouk et al., 2007; Schultz-Norton et al., 2007; Schultz-Norton et al., 2006; Schultz-Norton et al., 2007) and colocalized with ERα in MCF-7 cells, we wanted to determine whether they could interact with ERα. Bacterially expressed, GST-tagged RbAp46, GST-tagged RbAp48, or GST alone was immobilized and incubated with nuclear extracts from MCF-7 cells that had been treated with ethanol or E2 for 20 min. Endogenously-expressed ERα from MCF-7 nuclear extracts bound to both GST-RbAp46 (Fig. 3A, lanes 5 and 6) and GST-RbAp48 (lanes 7 and 8), but not to GST alone (lanes 3 and 4), demonstrating these two proteins interact with ERα in vitro. Nuclear extracts from the ethanol or E2-treated MCF-7 cells demonstrated that similar amounts of nuclear extracts were added to each reaction (lanes 1 and 2).

Fig. 3. Interaction of RbAp46 and RbAp48 with ERα.

(A) Bacterially expressed GST, GST-tagged RbAp46, or GST-tagged RbAp48 was immobilized on glutathione beads and incubated with nuclear extracts from MCF-7 cells that had been treated with ethanol or E2 for 20 min. Eluted proteins were subjected to Western analysis with an ERα specific antibody. Input (10%) was included (lanes 1 and 2) to demonstrate that equivalent amounts of ERα, RbAp46, and RbAp48 were present in the extracts from ethanol and E2 treated cells. (B) Extracts from MCF-7 cells that had been treated with ethanol or 10 nM E2 for 20 min were incubated with IgG, an RbAp46-specific, or an RbAp48-specific antibody. Specifically-bound proteins were eluted and subjected to Western analysis using an ERα-specific antibody (top panel) or antibodies directed against RbAp46 and RbAp48 (bottom panel). Input (2%) was included (lanes 1 and 2) to demonstrate that equivalent amounts of ERα, RbAp46, and RbAp48 were present in the extracts from ethanol and E2 treated cells. Data from 3 independent experiments were combined and are presented as the mean ± SEM to the right of each blot.

To determine whether endogenously-expressed ERα and RbAp46 or RbAp48 interact, immunoprecipitation experiments were performed. Whole cell extracts from MCF-7 cells that had been treated with ethanol or E2 for 20 min were incubated with IgG, RbAp46-specific, or RbAp48-specific antibodies. Although similar amounts of RbAp46 and RbAp48 were immunoprecipitated when MCF-7 cells had been treated with ethanol or E2 (Fig. 3B, lanes 5–8), significantly more ERα was immunoprecipitated with the RbAp-specific antibodies when MCF-7 cells had been treated with ethanol (lanes 5 and 7) than with E2 (lanes 6 and 8). Furthermore, the amount of ERα, RbAp46, or RbAp48 immunoprecipitated with RbAp-specific antibodies was far greater than was immunoprecipitated with IgG (lanes 3 and 4). Control lanes were included to demonstrate that similar amounts of whole cell extracts had been added to each lane (lanes 1 and 2). These studies indicate that endogenously-expressed ERα RbAp46, and RbAp48 interact more effectively in the absence than in the presence of hormone.

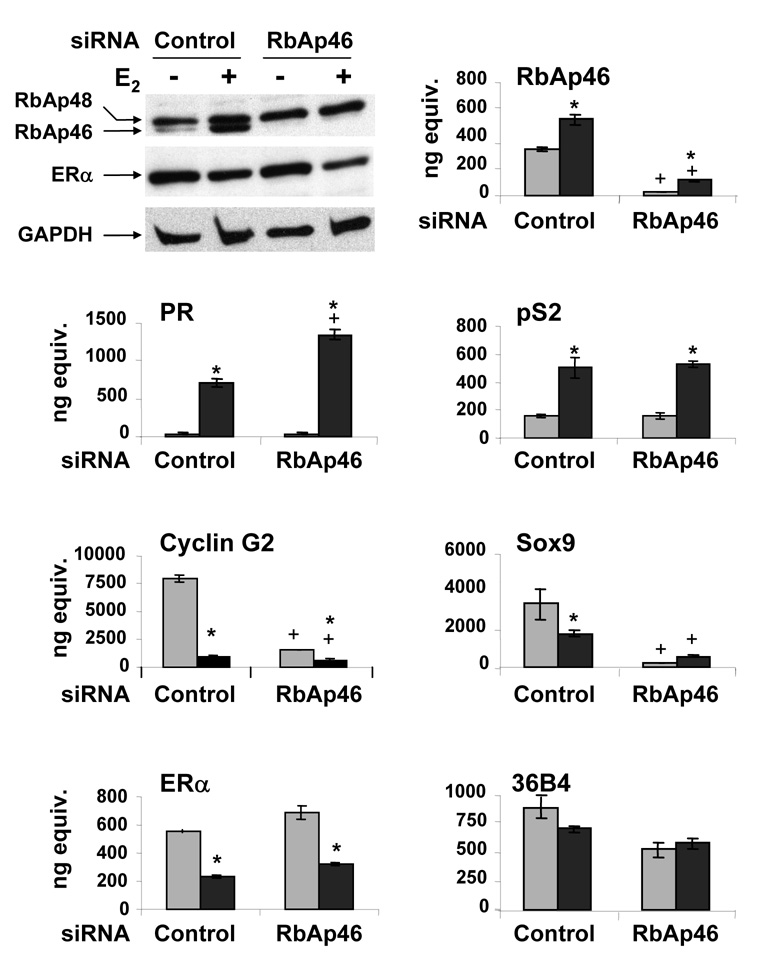

RbAp46 and RbAp48 influence ERα-mediated transcription

Since both RbAp46 and RbAp48 are present in protein complexes involved in transcription repression (Ahringer, 2000; Bowen et al., 2004; Knoepfler and Eisenman, 1999; Zhang et al., 1997) and we showed that both proteins interact with ERα, we next determined whether RbAp46 and RbAp48 might influence ERα-mediated transcription. To examine the effects of these two proteins on endogenous, estrogen-responsive gene expression, MCF-7 cells were transfected with control, RbAp46-specific, or RbAp48-specific siRNA to decrease their expression. We examined the expression of RbAp46 and RbAp48, the progesterone receptor (PR) and pS2 genes, which are activated by E2 (Berry et al., 1989; Brown et al., 1984; Nardulli et al., 1988; Petz and Nardulli, 2000; Petz et al., 2002; Petz et al., 2004; Petz et al., 2004) and the cyclin G2, Sox9, and ERα genes, which are repressed by E2 (Carroll et al., 2006; Couse et al., 2001; Frasor et al., 2003; Monsma et al., 1984; Stossi et al., 2006).

When RbAp46-specific siRNA was utilized, RbAp46 mRNA and protein levels were significantly decreased in the absence and in the presence of E2 (Fig. 4). In contrast, RbAp48 and GAPDH proteins levels, as well as RNA levels for the control gene 36B4, were unaffected by the RbAp46 siRNA. As expected, PR and pS2 mRNA levels were increased in MCF-7 cells that had been exposed to control siRNA and treated with E2 for 24 h. When MCF-7 cells were treated with RbAp46-specific siRNA, PR mRNA levels were significantly increased in the presence but not in the absence of E2. In contrast, pS2 expression was unaffected by the decreased RbAp46 expression suggesting that RbAp46 influences E2-mediated transactivation in a gene specific manner. When control siRNA was utilized, the mRNA levels of cyclin G2, Sox9, and ERα decreased upon E2 treatment as expected. When MCF-7 cells were exposed to RbAp46-specific siRNA, both cyclin G2 and Sox9 mRNA levels were significantly decreased in the absence and in the presence of E2, but ERα mRNA and protein levels were unchanged, suggesting that RbAp46 alters E2-mediated transrepression in a gene-specific manner. The ability of endogenously-expressed RbAp46 to enhance the activation of the Sox 9 and Cyclin G2 genes and attenuate activation of the PR gene suggests that RbAp46 differentially regulates estrogen-responsive genes. A significant increase in RbAp46 mRNA and protein levels was observed when MCF-7 cells had been treated with E2 for 24 hrs.

Fig. 4. Effect of RbAp46 on endogenous, estrogen-responsive genes.

MCF-7 breast cancer cells were transfected with control or RbAp46-specific siRNA and then treated with ethanol (gray bars) or 10 nM E2 (black bars) for 24 hrs. Whole cell extracts (30 µg) were subjected to Western analysis using an antibody directed against both RbAp46 and RbAp48 or GAPDH. The levels of mRNA were quantified in triplicate using real time PCR with gene specific primers. ANOVA analysis was performed using SAS 9.1. An asterisk indicates a significant difference (p<0.05) in the E2-treated cells compared to ethanol-treated cells and a plus sign indicates a significant difference (p<0.05) in the RbAp46-specific siRNA compared to the corresponding control siRNA. Error bars are sometimes too small to be visualized. Data is representative of three independent experiments.

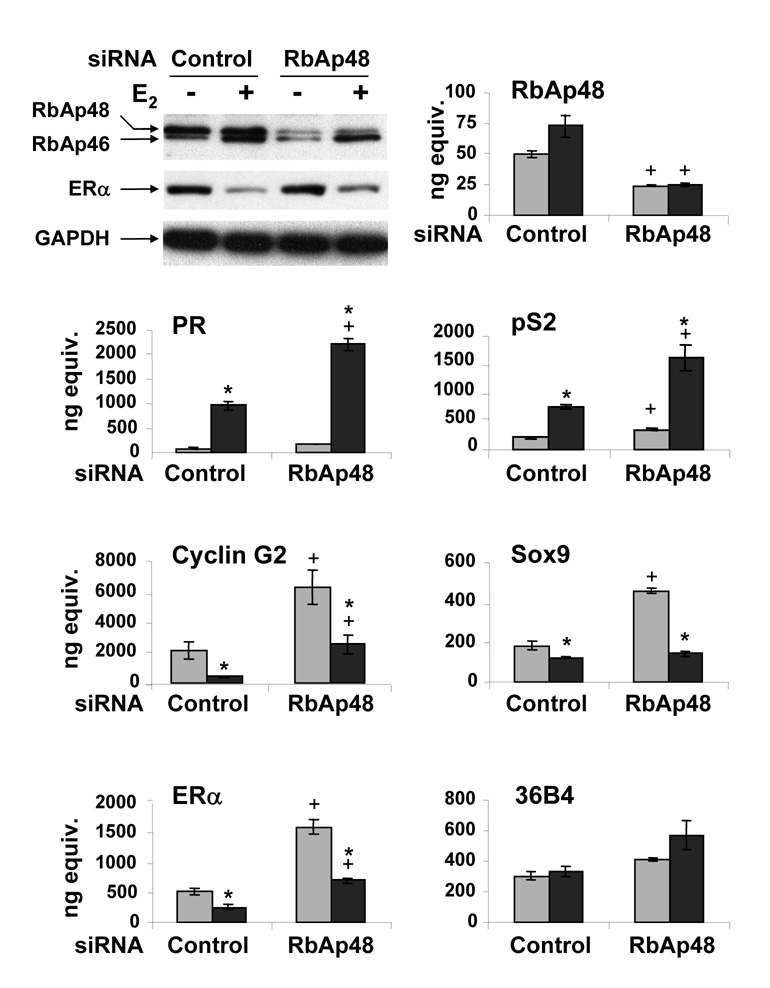

When RbAp48-specific siRNA was utilized, RbAp48 mRNA and protein levels, but not RbAb46 protein levels, were significantly decreased in the absence and in the presence of E2 (Fig. 5). PR and pS2 mRNA levels were increased as expected when MCF-7 cells were treated with control siRNA and exposed to E2 for 24h. When RbAp48 protein was knocked down, PR and pS2 mRNA levels significantly increased in the presence of E2. When control siRNA was used, the mRNA levels of cyclin G2, Sox9, and ERα were decreased in the presence of E2 as expected. When control siRNA was used, the mRNA levels of cyclin G2, Sox9, and ERα were decreased in the presence of E2 as expected. When RbAp48-specific siRNA was utilized, cyclin G2 mRNA levels were significantly increased in the absence and in the presence of E2 and Sox9 mRNA levels were increased in the absence of E2. We also noted an increase in ERα mRNA and protein levels. No significant difference was observed in the mRNA level of the 36B4 control gene when RbAp48-specific siRNA was used. Taken together, these data suggest that RbAp48 has the overall effect of limiting estrogen-responsive gene expression.

Fig. 5. Effect of RbAp48 on endogenous, estrogen-responsive genes.

MCF-7 breast cancer cells were transfected with control or RbAp48-specific siRNA and then treated with ethanol (gray bars) or 10 nM E2 (black bars) for 24 hrs. Whole cell extracts (30 µg) were subjected to Western analysis using an antibody directed against both RbAp46 and RbAp48 or GAPDH. The levels of mRNA were quantified in triplicate using real time PCR with gene specific primers. ANOVA analysis was performed using SAS 9.1. An asterisk indicates a significant difference (p<0.05) in the E2-treated cells compared to ethanol-treated cells and a plus sign indicates a significant difference (p<0.05) in the RbAp48-specific siRNA compared to the corresponding control siRNA. Error bars are sometimes too small to be visualized. Data is representative of three independent experiments.

RbAp46, RbAp48, and ERα interact with endogenous, estrogen-responsive genes

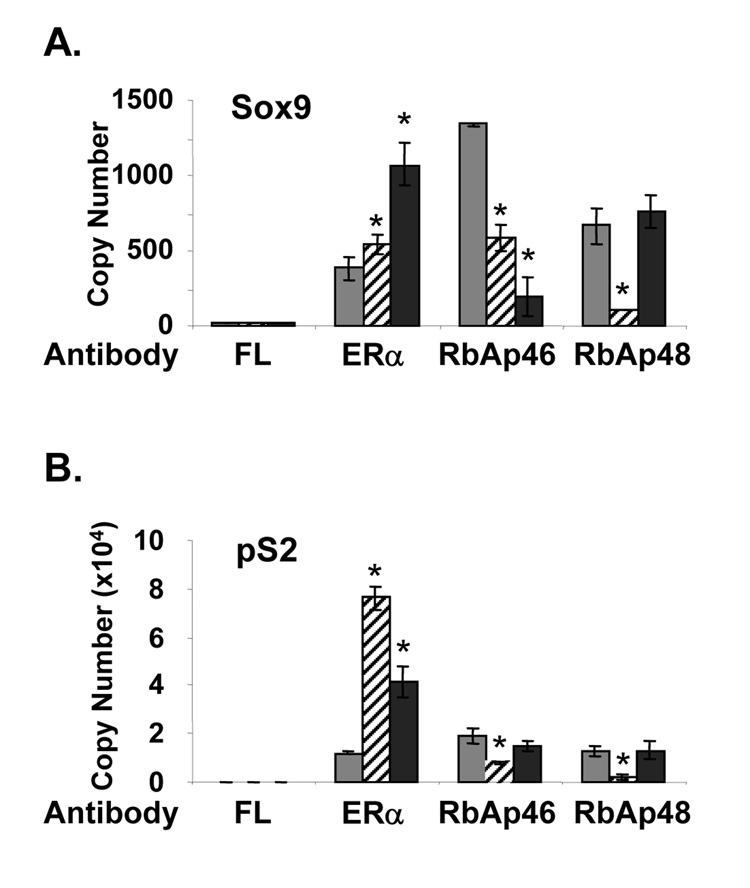

To further clarify the roles of RbAp46 and RbAp48 in regulating transcription, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were performed. Antibodies directed against ERα, RbAp46, and RbAp48 were used to immunoprecipitate chromatin from MCF-7 cells that had been treated with ethanol or E2. Since we were particularly interested in defining the effects of RbAp46 and RbAp48 on E2-repressed genes and shorter E2 treatments have been used more successful in examining repressed genes in ChIP assays, we limited the E2 treatment times to 45 min and 4 hrs (Stossi et al., 2006). A control antibody directed against fluorescein, a protein not found in mammalian cells, was used as a negative control. ChIP assays were analyzed by quantitative real time PCR to determine whether ERα, RbAp46, and/or RbAp48 were associated with a 3’ region of the Sox9 gene that contains two imperfect EREs and seven imperfect half ERE sites and is associated with ERα (Carroll et al., 2006). We found that more ERα was associated with this region of the Sox9 gene in the presence than in the absence of E2 (Fig. 6A). Association of RbAp46 with the Sox9 gene region decreased significantly upon E2 treatment. RbAp48 association with the Sox9 gene also decreased after 45 min of E2 treatment, but returned to the levels found in the absence of E2 after 4 hrs of E2 treatment. Significantly more ERα, RbAp46 and RbAp48 were associated with the Sox9 gene region in the absence and presence of E2 compared to the control fluorescein (FL) antibody.

Fig. 6. Association of ERα, RbAp46, and RbAp48 with endogenous, estrogen-responsive genes.

MCF-7 cells were treated with ethanol vehicle (gray bars) or E2 for 45 min (hatched bars) or 4 hrs (black bars) and subjected to ChIP analysis. Chromatin was immunoprecipitated with antibody directed against fluorescein (FL), ERα, RbAp46, or RbAp48. Quantitative real time PCR was performed in triplicate with primers specific to the Sox9 (A) or pS2 (B) gene. Standard curves were utilized to determine the number of genomic copies immunoprecipitated. Data shown is representative of five independent experiments and is the mean ± S.D. ANOVA analysis was performed using SAS 9.1. An asterisk indicates a significant difference (p<0.05) in the E2-treated cells compared to ethanol treated cells. Error bars are sometimes too small to be visualized.

The association of ERα, RbAp46, and RbAp48 with the region of the pS2 gene containing an imperfect ERE was used for comparison. As expected, more ERα was associated with the pS2 promoter in MCF-7 cells that had been treated with E2 (Fig. 6B) than with ethanol. The transient decreased association of RbAp46 and RbAp48 with the pS2 promoter after 45 min of E2 treatment suggested that these two proteins were associated with the pS2 gene region in the absence of hormone and reassociated with this gene region after 4 hrs of E2 treatment. In support of this idea, significantly more copies of the pS2 ERE region were immunoprecipitated with antibodies directed against ERα, RbAp46, and RbAp48 than with the control fluorescein (FL) antibody. The association of RbAp46 and RbAp48 with DNA in the absence and presence of hormone might be anticipated since both proteins interact with histones (Verreault et al., 1996; Verreault et al., 1998).

DISCUSSION

Our studies have demonstrated that RbAp46 and RbAp48 interact with ERα in vitro and in vivo, associate with endogenous, estrogen-responsive genes, and alter the expression of activated and repressed genes. These represent novel interactions and activities for RbAp46 and RbAp48.

Effects of RbAp46 and RbAp48 on endogenous, estrogen-responsive gene expression

Although RbAp46 and RbAp48 are homologous proteins, there are regions of divergence in their amino acid sequence (Qian and Lee, 1995). Likewise, while there are similarities in their activities, each protein has distinct functions as well. Both RbAp46 and RbAp48 limit expression of the endogenous, estrogen-responsive PR gene in MCF-7 cells, which is consistent with previous reports that these two proteins are involved in repressing gene expression (Ahringer, 2000; Bowen et al., 2004; Knoepfler and Eisenman, 1999; Zhang et al., 1997). In contrast to their similar activities on the PR gene, RbAp46 and RbAp48 had opposing effects on the expression of repressed genes. While RbAp46 increased expression of the cyclin G2 and Sox9 genes, RbAp48 decreased their expression. Thus, the increased expression of RbAp46 after 24 hrs of E2 treatment could help to provide a more graded response to hormone, limit repression, and sustain a modest level of gene expression. The ability of RbAp48 to decrease gene expression was most apparent in the absence of hormone suggesting that the primary role of this protein may be to help limit expression of estrogen-repressed genes in a hormone-free environment.

The ability of RbAp46 and RbAp48 to repress gene expression is probably not due to the intrinsic activity of these proteins, but is more likely due to their association with protein complexes involved in repressing gene expression. Interestingly, in addition to isolating RbAp46 and RbAp48, we also isolated and identified metastasis associated protein 2 (MTA2) and histone deacetylase 2 (HDAC2) as proteins associated with the DNA-bound ERα (data not shown). RbAp46, RbAp48, MTA2 and HDAC2 are all components of the NuRD complex, which remodels chromatin, decreases acetylation of histones, and limits gene expression (Ahringer, 2000; Knoepfler and Eisenman, 1999). Since MTA2 interacts directly with ERα (Cui et al., 2006; Yao and Yang, 2003), ERα interacts with RbAp46 and RbAp48, and ERα, RbAp46, RbAp48, MTA2, and HDAC2 are associated with the DNA-bound ERα, these proteins may form an interconnected network that together modify gene expression (Ahringer, 2000; Knoepfler and Eisenman, 1999).

It has been suggested that the ability of a transcription factor to interact with multiple partners can enable it to function in both activation and repression of transcription (Privalsky, 2004). Our siRNA experiments suggest that RbAp46 is a particularly versatile protein that can participate in gene activation and repression. The dual capacity of RbAp46 to act as a coactivator and a corepressor may be derived in part from its ability to foster protein-protein interactions (Ahringer, 2000; Knoepfler and Eisenman, 1999; Martinez-Balbas et al., 1998; Parthun, 2007; Verreault et al., 1998) and to interact with ERα. We have demonstrated that when ERα binds to EREs with slightly different nucleotide sequence discrete changes in receptor conformation occur, which alter coregulatory protein recruitment and transactivation (Loven et al., 2001; Loven et al., 2001; Wood et al., 1998; Wood et al., 2001). The ability of ERα to recruit different cohorts of proteins to discrete gene regulatory regions combined with the ability of RbAp46 to serve as a platform for other proteins may help to determine whether RbAp46 acts as a coactivator or corepressor. The ability of a single transcription factor to activate and repress gene expression has been observed for other ERα-associated proteins including receptor interacting protein p140 (Fernandes and White, 2003), silencing mediator of retinoid and thyroid receptors (Peterson et al., 2007), protein disulfide isomerase (Schultz-Norton et al., 2006), flap endonuclease 1 (Schultz-Norton et al., 2007), and superoxide dismutase 1 (Rao et al., 2008).

Effect of RbAp46 and RbAp48 on Sox9 gene expression

The divergent activities of RbAp46 and RbAp48 are obvious in their effects on ERα-repressed genes. While the overall effect of RbAp46 is to increase expression of repressed genes, the overall effect of RbAp48 is to decrease their expression. In spite of these opposing activities on gene expression, RbAp46 and RbAp48 can act in concert to regulate gene expression. The decreased association of RbAp46 with the Sox9 gene, which increases Sox9 expression, and the continued association of RbAp48 with the Sox9 gene, which decreases Sox9 expression, would have the overall effect of repressing expression of this gene. The ability of RbAp46 and RbAp48 to interact with ERα and facilitate protein-protein interactions (Ahringer, 2000; Knoepfler and Eisenman, 1999; Martinez-Balbas et al., 1998; Parthun, 2007; Verreault et al., 1998) may also help to foster the assembly of protein complexes at gene regions involved in transcriptional control.

Biological activity of RbAp46 and RbAp48

Given their association with ERα, it is not surprising that RbAp46 and RbAp48 would influence estrogen-responsive gene expression and alter target cell function. In fact, RbAb46 expression is increased in the mammary gland during pregnancy (Ginger et al., 2001). It has been suggested that this increased expression of RbAp46 initiates changes in the mammary gland gene expression profile that persist after parturition (Ginger et al., 2001).

RbAp46 and RbAp48 were originally identified as proteins associated with retinoblastoma (Nicolas et al., 2000; Qian and Lee, 1995; Qian et al., 1993). Thus, the association of RbAp46 and RbAp48 with cancer might be anticipated. Decreased expression of RbAp48 has been implicated in the increased incidence of cervical cancer (Kong et al., 2007). Our studies suggest that this increase in carcinogenesis may be due in part to the increased expression of ERα-repressed genes, which are no longer attenuated by RbAp48 in the absence of hormone (Fig. 5). On the other hand, increased expression of RbAp46 has been implicated in a decreased incidence in mammary tumor formation (Ginger et al., 2001; Guan et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2003), which is consistent with the ability of RbAb46 to selectively limit ERα-activated and enhance ERα-repressed gene expression (Fig. 4). Taken together, our studies suggest that the ability of RbAp46 and RbAp48 to interact with ERα and influence estrogen-responsive gene expression helps to maintain normal target cell function and that dysregulation of RbAp46 or RbAp48 can alter a cell’s susceptibility to the onset and/or progression of carcinogenesis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank B. Stillman and Z. Wang for expression vectors. This work was supported by NIH Grants RO1 DK053884 (to AMN) and NIH P41 RR11823-10 (to JRY). ALC was supported by a University of Illinois Predoctoral Fellowship.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Ahringer J. NuRD and SIN3 histone deacetylase complexes in development. Trends Genet. 2000;16:351–356. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)02066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry M, Nunez A-M, Chambon P. Estrogen-responsive element of the human pS2 gene is an imperfectly palindromic sequence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:1218–1222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.4.1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen NJ, Fujita N, Kajita M, Wade PA. Mi-2/NuRD: multiple complexes for many purposes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1677:52–57. doi: 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AMC, Jeltsch J-M, Roberts M, Chambon P. Activation of pS2 gene transcription is a primary response to estrogen in the human breast cancer cell line MCF-7. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81:6344–6348. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.20.6344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll J, Meyer C, Song J, Li W, Geistlinger T, Eeckhoute J, Brodshy A, Keeton E, Fertuck K, Hall G, Wang Q, Bekiranov S, Sementchenko V, Fox E, Silver P, Gingeras T, Liu X, Brown M. Genome-wide analysis of estrogen receptor binding sites. Nat Genetics. 2006;38:1289–1297. doi: 10.1038/ng1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collingwood TN, Urnov FD, Wolffe AP. Nuclear receptors: coactivators, corepressors and chromatin remodeling in the control of transcription. J Mol Endocrinol. 1999;23:255–275. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0230255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couse JE, Mahato D, Eddy EM, Korach KS. Molecular mechanism of estrogen action in the male: insights from the estrogen receptor null mice. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2001;13:211–219. doi: 10.1071/rd00128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couse JF, Korach KS. Estrogen receptor null mice: what have we learned and where will they lead us? Endocr Rev. 1999;20:358–417. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.3.0370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y, Niu A, Pestell R, Kumar R, Curran EM, Liu Y, Fuqua SA. Metastasis-associated protein 2 is a repressor of estrogen receptor alpha whose overexpression leads to estrogen-independent growth of human breast cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:2020–2035. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis CD, Likhite VS, McLeod IX, Yates JR, Nardulli AM. Interaction of nonmetastatic protein 23 homolog H1 and estrogen receptor alpha alters estrogen-responsive gene expression and DNA nicking. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10600–10610. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrzycka KM, Townson SM, Jiang S, Oesterreich S. Estrogen receptor corepressors -- a role in human breast cancer? Endocr Relat Cancer. 2003;10:517–536. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0100517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubal DB, Wilson ME, Wise PM. Estradiol: a protective and trophic factor in the brain. J Alzheimers Dis. 1999;1:265–274. doi: 10.3233/jad-1999-14-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Marzouk S, Schultz-Norton JR, Likhite VS, McLeod IX, Yates JR, Nardulli AM. Rho GDP dissociation inhibitor alpha interacts with estrogen receptor alpha and influences estrogen responsiveness. J Mol Endocrinol. 2007;39:249–259. doi: 10.1677/JME-07-0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes I, White JH. Agonist-bound nuclear receptors: not just targets of coactivators. J Mol Endocrinol. 2003;31:1–7. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0310001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasor J, Barnett DH, Danes JM, Hess R, Parlow AF, Katzenellenbogen BS. Response-Specific and Ligand Dose-Dependent Modulation of Estrogen Receptor (ER) α Activity by ERβ in the Uterus. Endocrinology. 2003;144:3159–3166. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-0143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginger MR, Gonzalez-Rimbau MF, Gay JP, Rosen JM. Persistent changes in gene expression induced by estrogen and progesterone in the rat mammary gland. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15:1993–2009. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.11.0724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan LS, Li GC, Chen CC, Liu LQ, Wang ZY. Rb-associated protein 46 (RbAp46) suppresses the tumorigenicity of adenovirus-transformed human embryonic kidney 293 cells. Int J Cancer. 2001;93:333–338. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoek M, Stillman B. Chromatin assembly factor 1 is essential and couples chromatin assembly to DNA replication in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:12183–12188. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1635158100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoepfler PS, Eisenman RN. Sin meets NuRD and other tails of repression. Cell. 1999;99:447–450. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81531-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong L, Yu XP, Bai XH, Zhang WF, Zhang Y, Zhao WM, Jia JH, Tang W, Zhou YB, Liu CJ. RbAp48 is a critical mediator controlling the transforming activity of human papillomavirus type 16 in cervical cancer. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:26381–26391. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702195200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laherty CD, Billin AN, Lavinsky RM, Yochum GS, Bush AC, Sun JM, Mullen TM, Davie JR, Rose DW, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG, Ayer DE, Eisenman RN. SAP30, a component of the mSin3 corepressor complex involved in N-CoR-mediated repression by specific transcription factors. Mol Cell. 1998;2:33–42. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loven MA, Likhite VS, Choi I, Nardulli AM. Estrogen response elements alter coactivator recruitment through allosteric modulation of estrogen receptor beta conformation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:45282–45288. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106211200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loven MA, Wood JA, Nardulli AM. Interaction of estrogen receptors alpha and beta with estrogen response elements. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2001;181:151–163. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(01)00491-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Balbas MA, Tsukiyama T, Gdula D, Wu C. Drosophila NURF-55, a WD repeat protein involved in histone metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:132–137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna NJ, O'Malley BW. Combinatorial control of gene expression by nuclear receptors and coregulators. Cell. 2002;108:465–474. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00641-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monsma FJ, Katzenellenbogen B, Miller M, Ziegler Y, JA K. Characterization of the estrogen receptor and its dynamics in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells using a covalently attaching antiestrogen. Endocrinology. 1984;115:143–153. doi: 10.1210/endo-115-1-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nardulli AM, Greene GL, O'Malley BW, Katzenellenbogen BS. Regulation of progesterone receptor messenger ribonucleic acid and protein levels in MCF-7 cells by estradiol: analysis of estrogen's effect on progesterone receptor synthesis and degradation. Endocrinology. 1988;122:935–944. doi: 10.1210/endo-122-3-935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolas E, Morales V, Magnaghi-Jaulin L, Harel-Bellan A, Richard-Foy H, Trouche D. RbAp48 belongs to the histone deacetylase complex that associates with the retinoblastoma protein. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:9797–9804. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parthun MR. Hat1: the emerging cellular roles of a type B histone acetyltransferase. Oncogene. 2007;26:5319–5328. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson TJ, Karmakar S, Pace MC, Gao T, Smith CL. The silencing mediator of retinoic acid and thyroid hormone receptor (SMRT) corepressor is required for full estrogen receptor alpha transcriptional activity. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:5933–5948. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00237-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petz LN, Nardulli AM. Sp1 binding sites and an estrogen response element half-site are involved in regulation of the human progesterone receptor A promoter. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14:972–985. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.7.0493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petz LN, Ziegler YS, Loven MA, Nardulli AM. Estrogen receptor alpha and activating protein-1 mediate estrogen responsiveness of the progesterone receptor gene in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Endocrinology. 2002;143:4583–4591. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petz LN, Ziegler YS, Schultz JR, Kim H, Kemper JK, Nardulli AM. Differential Regulation of the Human Progesterone Receptor Gene by an Estrogen Response Element Half Site and Sp1 Sites. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;88:113–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2003.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petz LN, Ziegler YS, Schultz JR, Nardulli AM. Fos and Jun inhibit estrogen-induced transcription of the human progesterone receptor gene through an activator protein-1 site. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:521–532. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Privalsky ML. The role of corepressors in transcriptional regulation by nuclear hormone receptors. Annu Rev Physiol. 2004;66:315–360. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.66.032802.155556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian YW, Lee EY. Dual retinoblastoma-binding proteins with properties related to a negative regulator of ras in yeast. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:25507–25513. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.43.25507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian YW, Wang YC, Hollingsworth RE, Jr, Jones D, Ling N, Lee EY. A retinoblastoma-binding protein related to a negative regulator of Ras in yeast. Nature. 1993;364:648–652. doi: 10.1038/364648a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao AK, Ziegler YS, McLeod IX, Yates JR, Nardulli AM. Effects of Cu/Zn Superoxide Dismutase (SOD1) on Estrogen Responsiveness and Oxidative Stress in Human Breast Cancer Cells. Mol Endocrinol. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22:1113–1124. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz JR, Petz LN, Nardulli AM. Cell- and ligand-specific regulation of promoters containing activator protein-1 and Sp1 sites by estrogen receptors α and β. J Bio Chem. 2005;280:347–354. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407879200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz-Norton JR, Gabisi VA, Ziegler YS, McLeod IX, Yates JR, Nardulli AM. Estrogen receptor alpha interaction with the DNA repair protein proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:5028–5038. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz-Norton JR, McDonald WH, Yates JR, Nardulli AM. Protein disulfide isomerase serves as a molecular chaperone to maintain estrogen receptor α structure and function. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:1982–1995. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz-Norton JR, Walt KA, Ziegler YS, McLeod IX, Yates JR, Raetzman LT, Nardulli AM. The DNA Repair Protein Flap Endonuclease-1 (FEN-1) Modulates Estrogen-Responsive Gene Expression. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:1569–1580. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stossi F, Likhite VS, Katzenellenbogen JA, Katzenellenbogen BS. Estrogen-occupied estrogen receptor represses cyclin G2 gene expression and recruits a repressor complex at the cyclin G2 promoter. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:16272–16278. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513405200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talukder AH, Mishra SK, Mandal M, Balasenthil S, Mehta S, Sahin AA, Barnes CJ, Kumar R. MTA1 interacts with MAT1, a cyclin-dependent kinase-activating kinase complex ring finger factor, and regulates estrogen receptor transactivation functions. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:11676–11685. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209570200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakur A, Rahman KW, Wu J, Bollig A, Biliran H, Lin X, Nassar H, Grignon DJ, Sarkar FH, Liao JD. Aberrant expression of X-linked genes RbAp46, Rsk4, and Cldn2 in breast cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2007;5:171–181. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verreault A, Kaufman PD, Kobayashi R, Stillman B. Nucleosome assembly by a complex of CAF-1 and acetylated histones H3/H4. Cell. 1996;87:95–104. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81326-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verreault A, Kaufman PD, Kobayashi R, Stillman B. Nucleosomal DNA regulates the core-histone-binding subunit of the human Hat1 acetyltransferase. Curr Biol. 1998;8:96–108. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise PM, Dubal DB, Wilson ME, Rau SW, Bottner M, Rosewell KL. Estradiol is a protective factor in the adult and aging brain: understanding of mechanisms derived from in vivo and in vitro studies. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2001;37:313–319. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(01)00136-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JR, Greene GL, Nardulli AM. Estrogen response elements function as allosteric modulators of estrogen receptor conformation. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:1927–1934. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.4.1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JR, Likhite VS, Loven MA, Nardulli AM. Allosteric modulation of estrogen receptor conformation by different estrogen response elements. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15:1114–1126. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.7.0671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao YL, Yang WM. The metastasis-associated proteins 1 and 2 form distinct protein complexes with histone deacetylase activity. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:42560–42568. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302955200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang TF, Yu SQ, Deuel TF, Wang ZY. Constitutive expression of Rb associated protein 46 (RbAp46) reverts transformed phenotypes of breast cancer cells. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:3735–3740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Iratni R, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Reinberg D. Histone deacetylases and SAP18, a novel polypeptide, are components of a human Sin3 complex. Cell. 1997;89:357–364. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80216-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]