Abstract

Recent reports implicate poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1) in the activation of NF-κB. We investigated the role of PARP-1 in the NF-κB signalling cascade induced by ionizing radiation (IR). AG14361, a potent PARP-1 inhibitor, was used in two breast cancer cell lines expressing different levels of constitutively activated NF-κB, as well as mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) proficient or deficient for PARP-1 or NF-κB p65. In the breast cancer cell lines, AG14361 had no effect on IR-induced degradation of IκBα or nuclear translocation of p50 or p65. However, AG14361 inhibited IR-induced NF-κB dependent transcription of a luciferase reporter gene. Similarly, in PARP-1-/- MEFs, IR-induced nuclear translocation of p50 and p65 was normal, but κB binding and transcriptional activation did not occur. AG14361 sensitized both breast cancer cell lines to IR-induced cell killing, inhibited IR-induced XIAP expression and increased caspase-3 activity. However, AG14361 failed to increase IR-induced caspase activity when p65 was knocked down by siRNA. Consistent with this, AG14361 sensitized p65+/+ but not p65-/- MEFs to IR. We conclude that PARP-1 activity is essential in the upstream regulation of IR-induced NF-κB activation. These data indicate that potentiation of IR-induced cytotoxicity by AG14361 is mediated soley by inhibition of NF-κB activation.

Keywords: NF-κB, PARP-1, ionizing radiation

INTRODUCTION

NF-κB represents a family of inducible transcription factors that regulates the expression of genes involved in apoptosis and cell proliferation. NF-κB exists as a heterodimeric complex of Rel family proteins (p50, p52, p65, cRel and RelB) that is physically confined to the cytoplasm through its interaction with inhibitor κB (IκB) proteins. Mammary NF-κB consists predominantly of p65/p50 heterodimers (Cao and Karin, 2003). Upon stimulation by inflammatory cytokines or DNA damage, several signalling cascades converge at the IKK complex which phosphorylates and targets IκBα for degradation, promoting nuclear translocation of NF-κB, where it binds to enhancer/promoter regions of target genes, activating transcription (Ghosh and Karin, 2002).

Aberrant activation of NF-κB is very common in cancers (Bassères and Baldwin, 2006). Elevated NF-κB DNA binding activity has been demonstrated both in breast cancer cell lines and primary breast cancer tissues (Biswas et al., 2004; Nakshatri et al., 1997; Sovak et al., 1997). NF-κB activation has been reported following both low and high doses of ionizing radiation (IR) (Brach et al., 1991; Criswell et al., 2003). DNA damage-activated NF-κB induces anti-apoptotic genes, thereby inhibiting apoptosis (Barkett and Gilmore, 1999; Wang et al., 1998). Loss or inhibition of NF-κB activation leads to radio-sensitization (Criswell et al., 2003; Jung and Dritschilo, 2001; Russo et al., 2001). Constitutive activation of NF-κB contributes to malignant progression, radio- and chemo-resistance and increased metastasis of breast tumors. Thus, inhibition of NF-κB represents a promising therapeutic strategy (Biswas et al., 2001; Wu and Kral, 2005). Although most studies have focussed on the mechanisms and pathways that lead to nuclear localization of NF-κB, nuclear modifications such as phosphorylation and acetylation of NF-κB subunits can affect NF-κB function (Perkins, 2006). Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1) is now emerging as an essential factor in the nuclear regulation of NF-κB activity.

PARP-1 plays an important role in modulating the cellular responses to DNA damage (Smith, 2001). We have previously shown that PARP-1 mediates the repair of both DNA single and double strand breaks induced by IR (Veuger et al., 2003). Recent evidence also supports a role for PARP-1 as a transcriptional co-regulator, with the enzyme being implicated in the control of NF-κB, AP-1, Oct1, and more recently HIF-1α (Kraus and Lis, 2003; Martin-Oliva et al., 2006). The role of PARP-1, more specifically its catalytic activity, in the modulation of NF-κB function is contentious, and is likely to be both cell type and stimulus specific (Hassa et al., 2005; Hassa and Hottiger, 1999; Oliver et al., 1999). Furthermore, the role of PARP-1 as a mediator of NF-κB activation in response to IR has not been investigated..

AG14361 is a potent PARP-1 inhibitor (Ki < 5 nM) that has previously been shown to potentiate IR-induced cell killing and enhance tumor regression in xenograft models (Skalitzky et al., 2003; Calabrese et al., 2004; Veuger et al., 2003). We evaluated the impact AG14361 on constitutive and IR-induced NF-κB activity in breast cancer cell lines, as well as mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) proficient or deficient for PARP-1 or p65. The data presented here lead us to hypothesise that PARP-1 is an essential mediator of IR-induced NF-κB activation, which in turn is an essential mediator of resistance to IR .

RESULTS

Characterization of cell lines

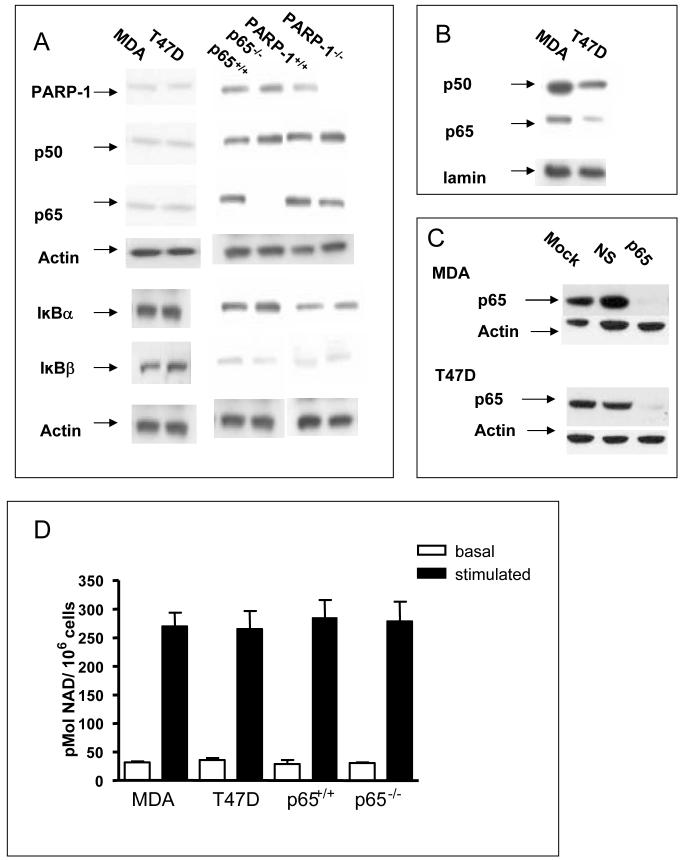

P65-/- MEFs lacked p65, but showed similar levels of p50, PARP-1, IκBα and IκBβ to the p65+/+ cells (Fig. 1A). PARP-1-/- MEFs lacked PARP-1 but showed bands of similar intensity to the PARP-1+/+ cells for p50, p65, IκBα and IκBβ. The two breast cancer cell lines contained similar levels of PARP-1, p50 and p65. There was very little nuclear p50 or p65 in the PARP-1+/+, PARP-1-/-, p65+/+ and p65-/- MEFs (data not shown). MDA cells are reported to have higher levels of p50 and p65 in the nucleus and a lower level of IκBβ compared to T47D cells (Nakshatri et al., 1997). We also found higher nuclear levels of p50 and p65 in the MDA cells, but no difference in the levels of either IκBα or IκBβ (Fig. 1A,1B and Supplementary Fig. S1). Transient transfection of p65 siRNA resulted in knockdown of p65 protein, and this was maximal (95% reduction) by 48 h (Fig. 1C), and persisted up to 72 h. Fig. 1D shows that PARP activity was very similar in all the cell lines. We have previously shown that PARP activity is very low (< 5%) in the PARP-1-/- MEFs used here (Veuger et al., 2003).

FIGURE 1. Characterization of cell lines.

(A) Western blots of whole cell extracts from untreated cells Blots were probed for PARP-1, p50, p65, IkBα, IkBβ and actin. (B)Western blots of nuclear extracts from untreated cells Blots were probed for p50, p65 and lamin. (C) Western blots of whole cell extracts of MDA-MB-231 and T47D at 48 h following transfection with vehicle alone, non specific siRNA or p65 siRNA. (D) PARP-1 activity. Open bars, basal activity in the absence of oligonucleotide; closed bars, oligonucleotide-stimulated activity. Results are the mean of three replicates from three independent experiments ± SE

AG14361 inhibits NF-κB binding to DNA following IR

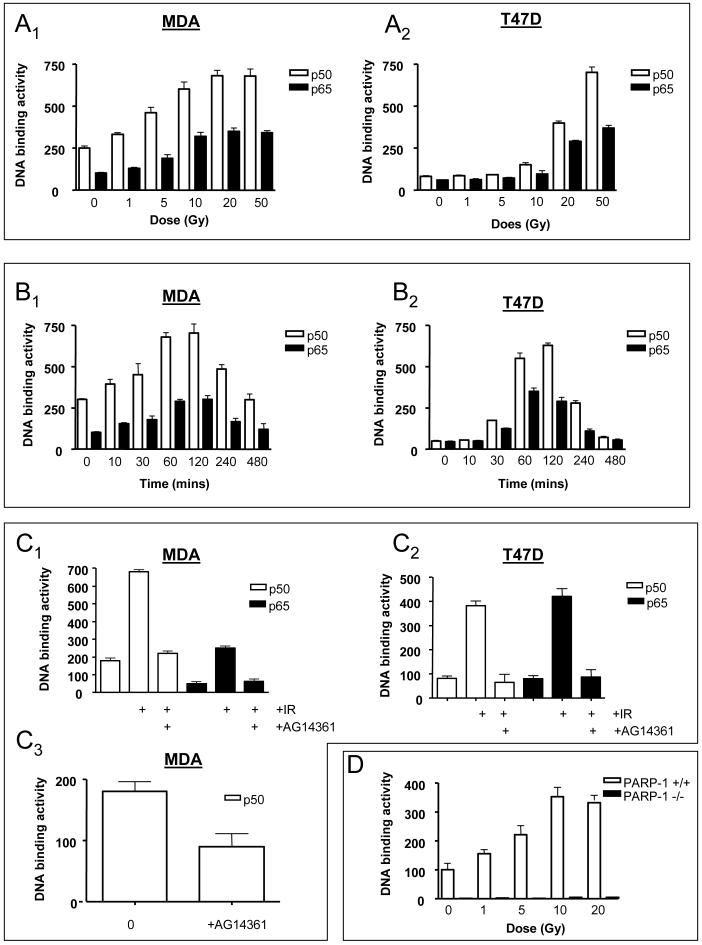

As predicted from published reports which used EMSA to measure NF-κB DNA binding activity, the ER-ve MDA cells contained higher levels of constitutive NF-κB DNA binding activity compared to T47D cells (compare Fig. 2A1 to 2A2) (Nakshatri et al., 1997). IR induced binding of p50 and p65 in both cell lines in a dose-dependent manner 2 h post-IR (Fig. 2A). The binding activity was competed out by wild type, but unaffected by a mutant, oligonucleotide (data not shown). Increased binding activity in the MDA cells was detectable following a clinically relevant dose of 1 Gy (Fig. 2A1). Similarly, in PARP-1+/+ MEFs, there was a 1.7-fold increase in DNA binding following 1 Gy (Fig. 2D). Maximal induction (p50 and p65) occurred at a higher dose of IR in the T47D compared to the MDA cell line (Fig. 2A1 versus 2A2 - 50 Gy compared to 20 Gy). Furthermore, the activation was greater in the T47D cells (15-fold versus 3-fold). Maximal binding occurred by 2 h and returned to basal levels by 8 h (Fig. 2B1 and 2B2) Subsequent experiments used a dose of 20 Gy to ensure maximal NF-κB activation. Importantly, incubation with 0.1 μM AG14361 completely prevented DNA binding 2 h following IR in both cell lines (Fig. 2C1 and 2C2). The DNA binding activity of p50 in the absence of IR in MDA cells was inhibited by >50 % by co-incubation with AG14361 for 24 h (Fig. 2C3). Nuclear extracts from IR-treated cells were incubated with AG14361 before carrying out the DNA binding assay. No reduction in binding was detected (data not shown) demonstrating that AG14361 does not interfere directly with the interaction of NF-κB with the DNA. Constitutive p50 DNA binding was extremely low in the PARP-1-/- cells compared to the PARP-1+/+ cells (Fig. 2D). IR stimulated DNA binding in the PARP-1+/+ (but not the PARP-1-/-) cells, with maximal binding at 10 Gy (Fig. 2D).

FIGURE 2. Effect of IR ± AG14361 on NF-κB DNA binding.

(A) P50 and p65 binding activity at 2 h following increasing doses of IR. A1, MDA-MB-231 cells; A2, T47D cells. (B) Kinetics of induction of p50 and p65 binding activity following 20 Gy IR. B1, MDA-MB-231 cells; B2, T47D cells. (C) Effect of AG14361 on IR-induced and constitutive p50 binding activity. C1, MDA-MB-231 cells 2 h following 20 Gy IR; C2 T47D cells 2 h following 20 Gy IR; C3, MDA-MB-231 cells in the absence of IR. (D) P50 binding activity 2 h following increasing doses of IR in PARP-1 +/+ and PARP-1 -/- cells

AG14361 does not affect IκBα degradation or NF-κB nuclear translocation

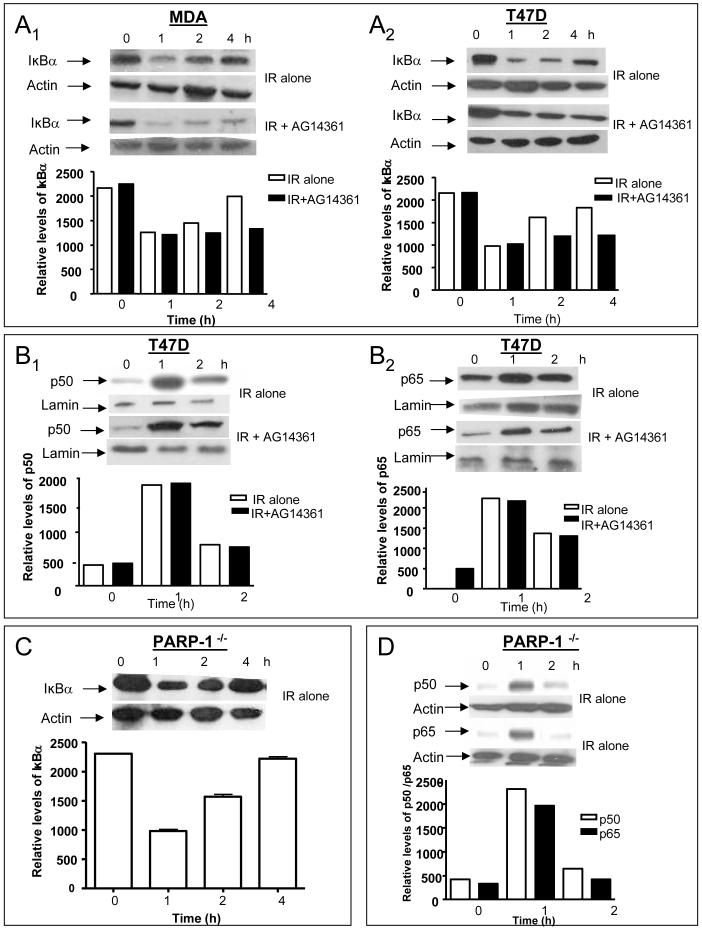

IR triggered a partial degradation (∼50%) of IκBα (Fig. 3A) with maximal degradation occurring by 1 h and returning towards control levels following 4 h. Treatment with AG14361 had no effect on IκBα degradation, but its resynthesis was suppressed (Fig. 3A). IR-induced IκBα degradation was also observed in PARP-1-/- MEFs (Fig. 3C). In the absence of IR, AG14361 had no effect on IκBα levels when incubated with cells for 72 h (data not shown). Nuclear translocation of both p50 and p65 in the T47D cells was observed 1 h after IR, returning back towards control levels by 2 h, in parallel with the kinetics of IκBα degradation (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Fig. S1), and this was unaffected by AG14361. Translocation of p50 and p65 occurred in the PARP-1-/- MEFs with similar kinetics to the T47D cell line (Fig. 3D and Supplementary Fig. S1), in agreement with Oliver et al., 1999.

FIGURE 3. Effect of IR ± AG14361 on IkBα degradation and nuclear translocation.

(A) Kinetics of degradation of IkBα following 20 Gy IR ± AG14361. A1, MDA-MB-231 cells; A2, T47D cells. Western blots of whole cell lysates. Blots were probed for IkBα. Bar charts:- relative density of a representative blot normalized to actin co-loading obtained by densitometry (B) Kinetics of nuclear translocation pf p50 and p65 following 20 Gy IR ± AG14361 in T47D cells. C1, T47D cells probed for p50; C2, T47D cells probed for p65. Western blots of nuclear extracts. Blots were probed for p50 or p65. Bar charts are normalized to lamin co-loading. (C) Kinetics of degradation of IkBα protein following 20 Gy IR in PARP-1-/- cells. Western blots of whole cell lysates. Blots were probed for IkBα. Bar charts are normalized to actin co-loading. (D) Kinetics of nuclear translocation of p50 and p65 following IR in PARP-1-/- cells. Blots were probed for p50 or p65. Bar charts are normalized to lamin co-loading.

AG14361 inhibits NF-κB dependent gene transcription following IR

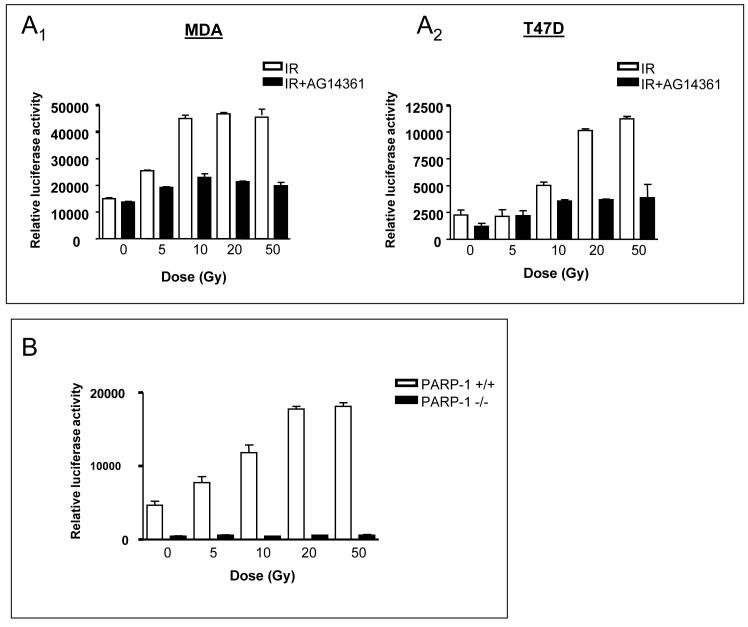

Induction of luciferase activity 8 h post- IR was dose-dependent in all cell lines tested (Fig. 4). IR did not influence the expression of the internal control plasmid used to monitor transfection efficiency (data not shown). Consistent with the increased DNA binding, the levels of constitutive luciferase expression were higher in the MDA cell line, and maximal luciferase activity occurred at a lower dose compared to the T47D cell line (10 Gy and 50 Gy, respectively) (Fig. 4A;B). AG14361 (0.1 μM) inhibited transcriptional activation by at least 80 % at all IR doses tested. Fig. 4B shows that the constitutive luciferase expression was about 10-fold lower in the PARP-1-/- than the PARP-1+/+ cells, consistent with previous a report (Carrillo et al., 2004). IR failed to activate gene transcription in the PARP-1-/- cells, but clearly stimulated luciferase expression in the PARP-1+/+ cells.

FIGURE 4. Effect of IR ± AG14361 on NF-κB transcriptional activity in the cell lines.

(A) Induction of luciferase activity 8 h following increasing doses of IR ± AG14361. A1, MDA-MB-231 cells; A2, T47D cells. (B) Induction of luciferase activity 8 h following increasing doses of IR in PARP-1 +/+ and PARP-1 -/- cells.

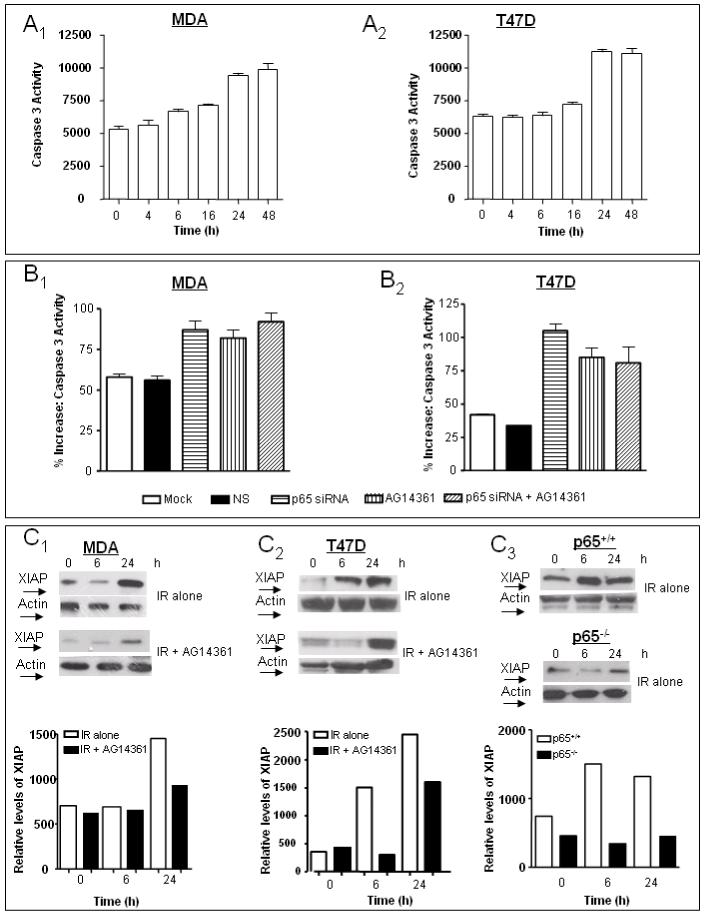

AG14361 increases apoptosis following IR

Caspase-3 activity is upregulated in cells with reduced NF-κB signalling (Cardoso and Oliveira, 2003). Caspase-3 activity was induced by 20 Gy IR in a time-dependent manner in both breast cancer cell lines (Fig. 5A1;A2), and this was maximal by 24 h.. P65 knockdown by siRNA and AG14361 were used to assess their effects on IR-induced caspase-3 activity (Fig. B1;B2). Compared to IR alone, both p65 knockdown and AG14361 significantly increased caspase-3 activity to approximately the same extent in both cell lines. Importantly, when AG14361 was used in conjunction with p65 knockdown, there was no significant difference in the caspase-3 activity compared to either agent alone. XIAP (X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis) is the most potent caspase inhibitor of the IAP family and its expression is regulated by NF-κB (Xiao et al., 2001). Western analysis showed that the levels of XIAP in the absence of stimulus were higher in the MDA than the T47D cell line (Fig. 5C1 versus 5C2). Following IR, XIAP protein was induced in all cell lines except for the p65-/- cell line (Fig. C3). This induction was partially suppressed by AG14361 in both breast cancer cell lines.

FIGURE 5. Effect of IR ± AG14361 on the levels of caspase-3 activity and XIAP protein.

(A) Kinetics of induction of caspase -3 activity following 20 Gy IR A1, MDA-MB-231 cells; A2, T47D cells. (B) The effect of IR ± AG14361 ± p65 siRNA on the induction of caspase-3 activity at 24 h post-IR. B1, MDA-MB-231 cells; B2, T47D cells. (C).Induction of XIAP following 20 Gy IR ± AG14361. C1, MDA-MB-231 cells; C2, T47D cells; C3, p65+/+ and p65-/- cells. Blots were probed for XIAP. Bar charts:-relative density of a representative blot normalized to actin co-loading.

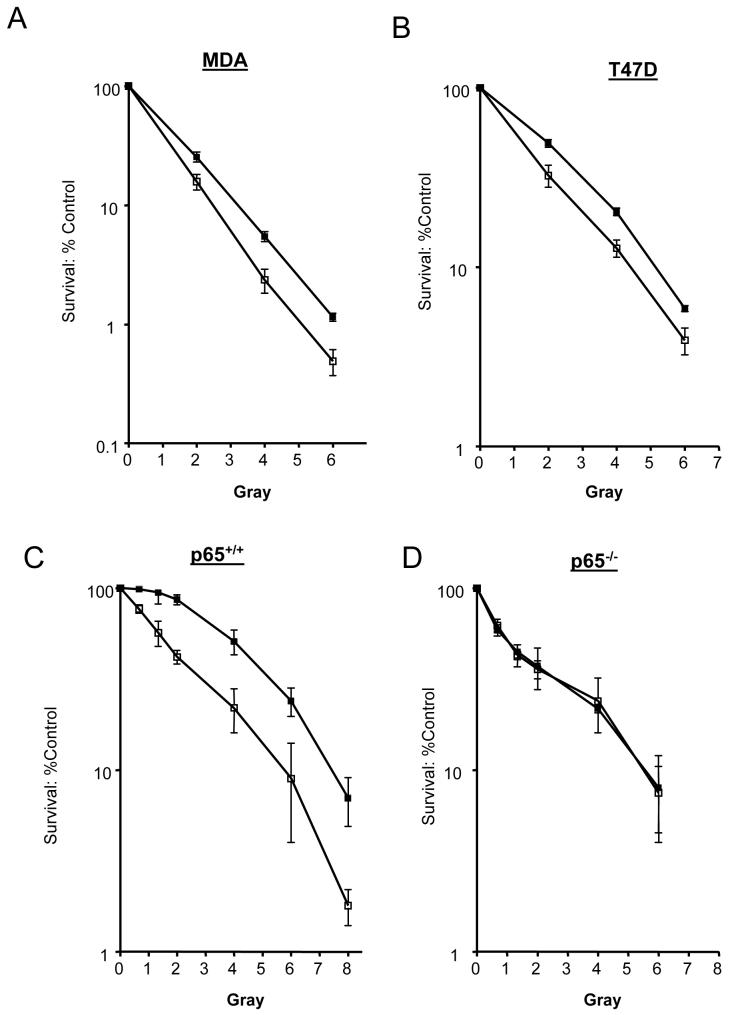

Radio-sensitization by AG14361

We investigated the ability of AG14361 to sensitize the breast cancer cell lines to IR by colony forming assays. The LD90 values for IR alone for MDA and T47D cell lines were 3.5 and 5.4, respectively. AG14361 sensitized both cell lines to IR (PF90 = 1.2 for both cell lines). The p65-/- cells were 1.3-fold more sensitive than the p65+/+ cells (Fig. 6C versus 6D). This demonstrates a role for NF-κB in preventing IR-induced cell death, and is consistent with data using TNFα as the inducer in the same cell lines (Beg and Baltimore, 1996). Co-incubation with AG14361 sensitized the p65+/+ cell line 1.3-fold (PF90). In marked contrast, there was no sensitization to IR by AG14361 in the p65-/- cell line at any of the doses tested. Preliminary data show that, as expected, p65 siRNA sensitised the p65+/+ cell line and not the p65-/- cell line to IR. However, when combined with AG14361, there was no additional sensitisation compared to either agent alone consistent with caspase data (Data not shown, Jill Hunter, unpublished results).

FIGURE 6. Effects of increasing doses of IR ± AG14361 on cell survival.

A, MDA-MB-231 cells; B, T47D cells; C, p65 +/+ cells; D, p65 -/-. ■, IR alone ; □, IR + AG14361. Data are the mean of 3 independent experiments ± SE.

DISCUSSION

Exposure of cells to cytotoxic agents and IR increases NF-κB activity (Brach et al., 1991; Criswell et al., 2003), conferring chemo- and radio-resistance by induction of anti-apoptotic proteins (Barkett and Gilmore, 1999; Wang et al., 1998). We investigated the role of PARP-1 in the individual steps within the NF-κB signalling cascade induced by IR. We showed high constitutive activity of NF-κB in the MDA cells which was inhibited by prolonged incubation with AG14361. In contrast, constitutive NF-κB activity was low in the T47D cells. IR activated NF-κB in both cell lines, consistent with the studies of Brach et al., 1991, and AG14361 fully inhibited this activation in both cell lines.

Reports suggest that NF-κB activation can occur with or without IκBα degradation following IR (Raju et al., 1998). We observed IR-induced IκBα degradation in all the cell lines tested. Although AG14361 did not inhibit IR- induced degradation of IκBα, its resynthesis was inhibited, indicating that the liberated NF-κB could not induce transcription of the IκBα gene. IR-induced NF-κB dependent gene transcription, assessed by a luciferase gene reporter assay, was completely inhibited by AG14361, although nuclear translocation of p50 and p65 was unaffected. Very similar results were obtained when PARP-1+/+ cells were compared with PARP-1-/- cells. However, resynthesis of IκBα was unaffected by the absence of PARP-1. This difference may be because inhibited PARP-1 may produce different physiological effects compared to the absence of PARP-1 protein. Although inhibitory effects on other PARP family proteins cannot be rigorously excluded, the consistency in the data obtained from both the inhibitor studies and the PARP-1-/- cell line suggest that this is not the case.

PARP-1 may modulate transcription either through local modification of chromatin structure and/or modulation of transcription factor activity via physical interactions with proteins including transcription factors, or direct binding to gene regulating sequences (Althaus et al., 1994; Kraus and Lis, 2003). The importance of PARP-1 enzymatic activity for NF-κB activation is controversial. Some groups have reported that PARP-1 enzyme activity directly influences NF-κB dependent transcription (Chang and Alvarez-Gonzalez, 2001; Chiarugi and Moskowitz, 2003; Nakajima et al., 2004). For example, Chang and Alvarez-Gonzalez, 2001, demonstrated that non-poly(ADP-ribosylated) PARP-1 binds NF-κB p50 and blocks its sequence-specific DNA binding and hence prevents transcriptional activation. In cells treated with H2O2, leading to DNA damage and hence PARP-1 activation, this binding is reversed upon PARP-1 automodification, enabling p50 to bind to the DNA and activate NF-κB-dependent transcription. Furthermore, pre-incubation with the PARP-1 inhibitor 3-aminobenzamide strongly inhibited NF-κB activation. These data are consistent with our results demonstrating that NF-κB activation in response to IR was completely dependent on PARP-1 catalytic activity. Conversely, Hassa et al., 2001, demonstrated that TNFα-mediated PARP-1 co-activation of the NF-κB transcription factor was attenuated in PARP-1 null cells, but was unaffected by either PARP-1 inhibition or over-expression of a mutant PARP-1 with no catalytic activity. We have also shown that TNF-α activates NF-κB in the MCF7 breast cancer cell line. Whereas knockdown of PARP-1 protein abrogated NF-κB activation, AG14361 had no effect (Martha Watson, unpublished results), consistent with the data of Hassa et al., 2001,. Both TNF- and IR signalling converge to activate NF-κB by the same canonical pathway, viz:- IκB kinase complex (IKK) activation, resulting in phosphorylation and proteosome-mediated degradation of IκB, freeing NF-κB to translocate to the nucleus. We show here, that PARP-1 mediates activation of NF-κB independent of the signalling pathways through which it is activated. Thus, the differential requirements of TNF-α and IR activated NF-κB for PARP-1 (protein only versus catalytic activity, respectively) must occur at the DNA binding and transcription stage. The differences in these observations evidently depend on the tissue or cell type and the type of inducing agent used. One possibility is that PARP-1 is not activated by TNF- and thus inhibition of PARP-1 should have no impact.

Dysregulation of NF-κB pathways is implicated in malignant progression (Biswas et al., 2004; Nakshatri et al., 1997; Sovak et al., 1997). NF-κB was found to be aberrantly elevated in ER- breast cancers and cell lines and our data support these findings. We showed a higher amount of aberrant p50 nuclear localisation and DNA binding when compared to p65 in the ER- MDA cell line. Additionally, the level of p50 was higher than p65 in both cell lines following exposure to IR. Zhou et al., 2005, also showed that DNA binding complexes with p50 were more abundant than p65 in breast tumor samples. Where the predominant NF-κB complex is the p50 homodimer, activation following IR would not necessarily be expected to yield a strong transcriptional response. Nevertheless, increased transcriptional activity following IR was observed in both breast cancer cell lines. Complex formation with the IκB homolog, BCl3, provides a mechanism by which IR may induce p50-associated NF-κB transcriptional activity in breast cancer cells which do not contain high levels of p65 (Pratt et al., 2003).

Radio-sensitization can be achieved at clinically relevant doses of IR by inhibiting NF-κB in many cancer cell types (Criswell et al., 2003; Jung and Dritschilo, 2001; Russo et al., 2001; Wang et al., 1996). We have previously shown that AG14361 potentiates IR-induced cell killing (Veuger et al., 2003). In this study, we demonstrated that AG14361 potentiated IR cytotoxicity in both ER+ and ER- breast cancer cell lines, and that this effect correlated with enhanced caspase-3 activity. P65-/- cells were more radiosensitive than p65+/+ cells, indicating that NF-κB activity is required for protection against cell killing induced by IR. Crucially, AG14361 sensitized the p65+/+, but not the p65-/-, cells to IR, suggesting that AG14361-mediated cell death is dependent on NF-κB function. This notion was substantiated by knocking down p65 in the breast cancer cell lines using siRNA. Similarly to AG14361, p65 knockdown resulted in enhanced caspase-3 activity compared to IR alone. Strikingly, the combination of AG14361 and p65 siRNA showed no additive effects, confirming that NF-κB and PARP-1 are affecting the same pathway. That the AG14361-mediated radio-sensitization is due soley to the inhibition of PARP-1 is supported by our previous observation that AG14361 potentiated IR-induced cytotoxicity in PARP-1+/+, but not PARP-1-/- cells (Veuger et al., 2003).

XIAP is the best characterised of mammalian IAPs and the most potent and versatile of these regulators of cell death (Holcik et al., 2001). XIAP is upregulated in many human tumor types (Ferreira et al., 2001). Yang et al., 2003, showed that downregulation of XIAP significantly enhanced apoptosis. We show here that AG14361 decreased the upregulation of XIAP protein following IR. XIAP mRNA levels were not investigated, as post-translational modifications of apoptosis effectors, including XIAP, (e.g. ubiquitylation, phosphorylation) may influence their stability, subcellular targeting and cell death function (Deveraux et al., 1999; Dan et al., 2004). XIAP has recently been shown to inhibit the apoptotic executioners caspase-3 and -7 (Scott et al., 2005). We showed that AG14361 increased caspase-3 activity concomitant with its effect in decreasing XIAP expression. This apoptotic response is p53-independent since both breast cancer cell lines used here are p53 mutant (Concin et al., 2003). .Moreover, NF-κB activation occurred in the PARP-1+/+ cells which we have previously demonstrated to have a mutant p53, with no activation in the PARP-1-/- cells, although they have a wild type p53 (Veuger et al., 2003).

Several therapeutic approaches have been used to suppress NF-κB activity, including proteosome and IKK inhibitors (Pande and Ramos, 2005). NF-κB inhibitors reduced metastasis in xenograft models (Andela et al., 2000). Parthenolide, which inhibits inhibits IKK activity, increased the sensitivity of breast cancer cell lines to taxol (Patel et al., 2000). An NF-κB decoy oligonucleotide stimulated apoptosis and upregulated caspase-3 activity in osteoclasts (Penolazzi et al., 2003). A PARP-1 inhibitor will usefully target NF-κB at the penultimate DNA binding and transcriptional activation stage. The role of PARP-1 is also likely to involve cross talk between different transcriptional factors activated by IR. For example, p53 is induced following IR, and both NF-κB and p53 share the CREB binding protein (CBP) and p300 as transcriptional coactivators.(Webster and Perkins, 1999). Acetylation of PARP-1 by CBP and p300 has been shown to be involved in the regulation of the NF-κB transcriptional response (Hassa et al., 2005).

In summary, we have demonstrated that PARP-1 function is essential for IR-induced NF-κB activation. Furthermore, the data support the hypothesis that the radio-sensitizing effects of AG14361 are a consequence of its effects on NF-kB activity. This hypothesis merits further investigation as it has important consequences for the design of therapeutic strategies deploying PARP-1 inhibitors which are currently in clinical trials.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

PARP-1 Inhibitor

AG14361 was synthesised by Pfizer GRD, CA. AG14361 and PJ34 (Axxora, Nottingham, UK) were dissolved in anhydrous DMSO at a stock concentration of 10 mM and stored at -20 °C. AG14361 was added in cell culture such that the final DMSO concentration was kept constant at 0.1 % (v/v), and was used at a final concentration of 1 μM in all experiments, unless otherwise stated.

Cell lines and Culture

Human breast cancer cell lines, MDA-MB-231 (estrogen-independent; estrogen receptor negative, ER-), hereafter referred to as MDA, and T47D (estrogen-dependent; estrogen receptor positive, ER++) were obtained from ATCC (Middlesex, UK). PARP-1 +/+ and PARP-1 -/- MEFs were a gift from Professor Gilbert de Murcia, École Superieure de Biotechnologie de Strasbourg, France. The p65 +/+ and p65 -/- MEFs were kindly provided by Professor Ron Hay, University of St Andrews, UK. All cell lines were cultured in DMEM medium (supplemented with 10 % (v/v) FCS, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin and 2 mM glutamine).

SiRNA Transfection

Cells were seeded, in 6-well cell culture plates at a density of 5×104 (MDA), or 1×105 (T47D) in 2mls of tissue culture medium and left overnight to adhere. SiRNA targeting human p65 (GCCCUAUCCCUUUACGUCA; Dharmacon, UK) was transfected at a final concentration of 50 nM using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, UK), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Controls used included non-specific (NS) siRNA and mock/vehicle only transfected cells. P65 knock down was confirmed by Western analysis.

Western Blotting

Proteins were resolved on 4-20 % (v/v) Tris glycine gradient gels (Invitrogen Ltd, Paisley, UK) and electrotransferred onto nitrocellulose (BioRad Herts., UK). Antibodies against PARP-1 (H-250), p50 (8414), p65 (8008), IκBα(371), IκBβ(945) and pIκBα (8404) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, (Santa Cruz, CA). AntiXIAP was aquired from R&D systems (Oxfordshire, UK). As loading controls, anti-actin antibody (mouse clone AC-40; Sigma, Dorset, UK) was used for whole cell extracts, antilamin A/C (7293; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) for nuclear extracts and -tubulin for cytoplasmic extracts (8035; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). This was followed by binding of peroxidase-conjugated goat antimouse/ rabbit antibody (DAKO, Ely, UK) and detection by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham International, Bucks., UK). Cells were pretreated with AG14361 for 60 min and exposed to IR. Cells were harvested at different time points and whole cell extracts were taken using SDS lysis buffer (100 mM Tris-Hcl pH 6.8, 20 % v/v glycerol, 4 % w/v SDS). Nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts were prepared using the NE-PER extraction kit as per manufacturers instructions (Pierce - Perbio science, Cheshire, UK)). No α-tubulin was detected in nuclear extracts and conversely, lamin was absent in all cytoplasmic extracts, thus demonstrating the efficiency of the kit (Supplementary Fig. S1). Bands were quantified and normalized to their relevant loading controls using densitometry (BIORAD Gel Doc, Quantity One, Herts., UK).

NF-κB DNA binding Assay

P50 and p65 DNA binding activities were determined using an ELISA-based EZ detect assay according to the manufacturers instructions (Promega Southampton, UK). Briefly, streptavidin-coated 96 well plates are bound with biotinylated κB consensus sequence oligonucleotides (5′GGGACTTTCC-3′). Nuclear extracts (prepared as above) were added to each well and incubated with primary antibody specific for either p50 or p65. Binding was detected using a secondary HRP-conjugated antibody and chemiluminescence measured using a CCD camera (LAS-300; Fujifilm). We have probed for PARP-1, histones and lamin in nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions, and these proteins were only be detected in the nuclear fractions (data not shown). Results were normalised to chemiluminescence/μg protein using the BCA protein assay as per manufacturers instructions (Pierce-Perbio science, Cheshire, UK).

Reporter Gene Assay

Cells were seeded onto 96 well plates and incubated for 24 h. Cells were transiently transfected with 200 ng of an NF-κB-luciferase construct containing 3 tandemly repeated NF-κB consensus sequence binding sites in the promoter (Professor Ron Hay, St Andrews University), together with 200 ng of a pCMB-β-galactosidase plasmid containing a minimal promoter element up-stream from the β-galactosidase gene, using FuGENE6 transfection reagent (Roche diagnostics, Sussex, UK)) for 6 h. 24 h after transfection, cells were treated with AG14361 for 1 h prior to IR. Following an 8 h incubation, cells were lysed and assayed for luciferase activity according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega, Southampton, UK). Luciferase activity was corrected for β-galactosidase activity as described previously, and relative activities expressed as fold changes.

Caspase-3 Assay

Caspase-3 activity was determined using the Caspase- Glo 3/7 kit (Promega, Southampton, UK). Cells were seeded onto a 96 well plate and incubated for 24 h. Cells were transfected with 50nM siRNA, 50 nM NS siRNA or lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen Ltd, Paisley, UK) and incubated for 48 h. Cells were treated with AG14361 for 60 min before IR and allowed to recover at 37°C before addition of Caspase-Glo 3/7 reagent to the culture medium at a 1:1 ratio, shaken for 30 seconds and incubated at room temperature for 2 h. Cell lysates were transferred to a white-walled 96 well plate. Luminescence was measured using a microplate luminometer (Perkin Elmer, Bucks., UK). Data were normalised to untreated controls.

PARP activity assay

PARP activity was assayed by measuring incorporation of radiolabel from [32P] NAD+ into acid precipitable counts in a permeabilised cell system (Grube et al., 1991). A 30 bp blunt-ended oligonucleotide was used to maximally activate PARP.

Cytotoxicity Assay

Clonogenic assays were carried out as described previously (Veuger et al., 2003). Data were normalised to untreated controls. PF90 (potentiation factor at 90% cell kill) values were calculated from the ratio of the individual LD90 - (lethal dose producing 90% cell kill) values:- i.e., LD90 divided by LD90 in the presence of AG14361.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary information is available at Oncogene's website.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Breast Cancer Campaign, UK and Cancer Research UK.

REFERENCES

- Althaus FR, Hofferer L, Kleczkowska HE, Malanga M, Naegeli H, Panzeter PL, et al. Histone shuttling by poly ADP-ribosylation. Mol Cell Biochem. 1994;138:53–59. doi: 10.1007/BF00928443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andela VB, Schwarz EM, Puzas JE, O’Keefe RJ, Rosier RN. Tumor metastasis and the reciprocal regulation of prometastatic and antimetastatic factors by nuclear factor kappaB. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6557–6562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkett M, Gilmore TD. Control of apoptosis by Rel/NF-kappaB transcription factors. Oncogene. 1999;18:6910–6924. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassères DS, Baldwin AS. Nuclear factor-kappaB and inhibitor of kappaB kinase pathways in oncogenic initiation and progression. Oncogene. 2006;25:6817–6830. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beg AA, Baltimore D. An essential role for NF-kappaB in preventing TNF-alpha-induced cell death. Science. 1996;274:782–784. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas DK, Dai SC, Cruz A, Weiser B, Graner E, Pardee AB. The nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kappa B): a potential therapeutic target for estrogen receptor negative breast cancers. Proc.Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:10386–10391. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151257998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas DK, Shi Q, Baily S, Strickland I, Ghosh S, Pardee AB, Iglehart JD. NF-kappa B activation in human breast cancer specimens and its role in cell proliferation and apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10137–10142. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403621101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brach M, Hass R, Sherman M, Gunji H, Weichselbaum R, Kufe D. Ionizing radiation induces expression and binding activity of the nuclear factor kB. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1991;88:691–695. doi: 10.1172/JCI115354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese CR, Almassy R, Barton S, Batey MA, Calvert AH, Canan-Koch S, et al. Anticancer chemosensitization and radiosensitization by the novel poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 inhibitor AG14361. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:56–67. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Karin M. NF-kappaB in mammary gland development and breast cancer. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2003;8:215–223. doi: 10.1023/a:1025905008934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso SM, Oliveira CR. Inhibition of NF-kB renders cells more vulnerable to apoptosis induced by amyloid beta peptides. Free Radic Res. 2003;37:967–973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo A, Monreal Y, Ramirez P, Marin L, Parrilla P, Oliver FJ, et al. Transcription regulation of TNF-alpha-early response genes by poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 in murine heart endothelial cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:757–766. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers A, Johnston P, Woodcock M, Joiner M, Marples B. PARP-1, PARP-2, and the cellular response to low doses of ionizing radiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;58:410–419. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang WJ, Alvarez-Gonzalez R. The sequence-specific DNA binding of NF-kappa B is reversibly regulated by the automodification reaction of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:47664–47670. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104666200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiarugi A, Moskowitz MA. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 activity promotes NF-kappaB-driven transcription and microglial activation: implication for neurodegenerative disorders. J Neurochem. 2003;85:306–317. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Concin N, Zeillinger C, Tong D, Stimpfl M, Konig M, Printz D, et al. Comparison of p53 mutational status with mRNA and protein expression in a panel of 24 human breast carcinoma cell lines. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2003;79:37–46. doi: 10.1023/a:1023351717408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Criswell T, Leskov K, Miyamoto S, Luo G, Boothman DA. Transcription factors activated in mammalian cells after clinically relevant doses of ionizing radiation. Oncogene. 2003;22:5813–5827. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dan HC, Sun M, Kaneko S, Feldman RI, Nicosia SV, Wang HG, et al. Akt phosphorylation and stabilization of X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) J Biol Chem. 2004;279:5405–5412. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312044200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deveraux QL, Leo E, Stennicke HR, Welsh K, Salvesen GS, Read GC. Cleavage of human inhibitor of apoptosis protein XIAP results in fragments with distinct specificities for caspases. EMBO J. 1999;18:5242–5251. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.19.5242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira C, van der Valk P, Span S, Jonker J, Postmus P, Kruyt F, et al. Assessment of IAP (inhibitor of apoposis) proteins as predictors of response to chemotherapy in advanced non small lung cancer patients. Annals of Oncology. 2001;12:799–805. doi: 10.1023/a:1011167113067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S, Karin M. Missing pieces in the NF-kappaB puzzle. Cell. 2002;109(Suppl):S81–96. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00703-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grube K, Kupper JH, Burkle A. Direct stimulation of poly(ADP ribose) polymerase in permeabilized cells by double-stranded DNA oligomers. Anal Biochem. 1991;193:236–239. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(91)90015-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassa PO, Covic M, Hasan S, Imhof R, Hottiger MO. The enzymatic and DNA binding activity of PARP-1 are not required for NF-kappa B coactivator function. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:45588–45597. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106528200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassa PO, Haenni SS, Buerki C, Meier NI, Lane WS, Owen H, et al. Acetylation of PARP-1 by p300/CBP regulates coactivation of NF-kappa B-dependent transcription. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:40450–40464. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507553200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassa PO, Hottiger MO. A role of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase in NF-kappaB transcriptional activation. J Biol Chem. 1999;380:953–959. doi: 10.1515/BC.1999.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holcik N, Gibson H, Korneluk RG. XIAP: apoptotic brake and promising therapeutic target. Apoptosis. 2001;6:253. doi: 10.1023/a:1011379307472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung M, Dritschilo A. NF-kappa B signaling pathway as a target for human tumor radiosensitization. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2001;11:346–351. doi: 10.1053/srao.2001.26034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus W, Lis J. PARP goes transcription. Cell. 2003;113:677–683. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00433-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Oliva D, Aguilar-Quesada R, O’valle F, Munoz-Gamez JA, Martinez-Romero R, Garcia Del Moral R, et al. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase modulates tumor-related gene expression, including hypoxia-inducible factor-1 activation, during skin carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5744–5756. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima H, Nagaso H, Kakui N, Ishikawa M, Hiranuma T, Hoshiko S. Critical role of the automodification of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 in nuclear factor-kappaB-dependent gene expression in primary cultured mouse glial cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:42774–42786. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407923200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakshatri H, Bhat-Nakshatri P, Martin DA, Goulet RJ, Jr, Sledge GW., Jr. Constitutive activation of NF-kappaB during progression of breast cancer to hormone-independent growth. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:3629–3639. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.7.3629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver FJ, Menissier-de Murcia J, Nacci C, Decker P, Andriantsitohaina R, Muller S, et al. Resistance to endotoxic shock as a consequence of defective NF-kappaB activation in poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 deficient mice. Embo J. 1999;18:4446–4454. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.16.4446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pande V, Ramos MJ. NF-kappaB in human disease: current inhibitors and prospects for de novo structure based design of inhibitors. Curr Med Chem. 2005;12:357–374. doi: 10.2174/0929867053363180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel NM, Nozaki S, Shortle NH, Bhat-Nakshatri P, Newton TR, Rice S, et al. Paclitaxel sensitivity of breast cancer cells with constitutively active NF-kappaB is enhanced by IkappaBalpha super-repressor and parthenolide. Oncogene. 2000;19:4159–4169. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penolazzi L, Lambertini E, Borgatti M. Decoy oligodeoxynucleotides targeting NFkB transcription factors: induction of apoptosis in human primary osteoclasts. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2003;66:1189–1198. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00470-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins ND. Good cop, bad cop: the different faces of NF-kappaB. Oncogene. 2006;25:6717–6730. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt MA, Bishop TE, White D, Yasvinski G, Menard M, Niu MY, et al. Estrogen withdrawal-induced NF-kappaB activity and bcl-3 expression in breast cancer cells: roles in growth and hormone independence. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:6887–6900. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.19.6887-6900.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raju U, Gumin GJ, Noel F, Tofilon PJ. IkappaBalpha degradation is not a requirement for the X-ray-induced activation of nuclear factor kappaB in normal rat astrocytes and human brain tumour cells. Int J Radiat Biol. 1998;74:617–624. doi: 10.1080/095530098141195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayet B, Gelinas C. Aberrant rel/nfkb genes and activity in human cancer. Oncogene. 1999;18:6938–6947. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo SM, Tepper JE, Baldwin AS, Jr, Liu R, Adams J, Elliott P, et al. Enhancement of radiosensitivity by proteasome inhibition: implications for a role of NF-kappaB. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;50:183–193. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)01446-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott FL, Denault JB, Riedl SJ, Shin H, Renatus M, Salvesen GS. XIAP inhibits caspase-3 and -7 using two binding sites: evolutionarily conserved mechanism of IAPs. Embo J. 2005;24:645–655. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skalitzky DJ, Marakovits JT, Maegley KA, Ekker A, Yu XH, Hostomsky Z, et al. Tricyclic benzimidazoles as potent poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2003;46:210–213. doi: 10.1021/jm0255769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. The world according to PARP. Trends Biochem Sci. 2001;26:174–179. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01780-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sovak MA, Bellas RE, Kim DW, Zanieski GJ, Rogers AE, Traish AM, et al. Aberrant nuclear factor-kappaB/Rel expression and the pathogenesis of breast cancer. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2952–2960. doi: 10.1172/JCI119848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veuger SJ, Curtin NJ, Richardson CJ, Smith GC, Durkacz BW. Radiosensitization and DNA repair inhibition by the combined use of novel inhibitors of DNA-dependent protein kinase and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6008–6015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CY, Mayo MW, Baldwin AS., Jr. TNF- and cancer therapy-induced apoptosis: potentiation by inhibition of NF-kappaB. Science. 1996;274:784–787. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CY, Mayo MW, Korneluk RG, Goeddel DV, Baldwin AS., Jr. NF-kappaB antiapoptosis: induction of TRAF1 and TRAF2 and c-IAP1 and c-IAP2 to suppress caspase-8 activation. Science. 1998;281:1680–1683. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5383.1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster GA, Perkins ND. Transcriptional cross talk between NF-kappaB and p53. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:3485–3495. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.5.3485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JT, Kral JG. The NF-kappaB/IkappaB signaling system: a molecular target in breast cancer therapy. J Surg Res. 2005;123:158–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao CW, Ash K, Tsang BK. Nuclear factor-kappaB-mediated X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein expression prevents rat granulosa cells from tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced apoptosis. Endocrinology. 2001;142:557–563. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.2.7957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Cao Z, Yan H, Wood W. Coexistence of high levels of apoptotic signalling and inhibitor of apoptosis proteins in human tumour cells: Implications for cancer specific therapy. Cancer Research. 2003;63:6815–6824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Eppenberger-Castori S, Marx C, Yau C, Scott GK, Eppenberger U, et al. Activation of nuclear factor-kappaB (NFkappaB) identifies a high-risk subset of hormone-dependent breast cancers. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2005;37:1130–44. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.