Abstract

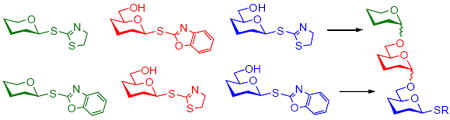

Thorough mechanistic studies of the alkylation pathway for the activation of glycosyl thioimidates have led to the development of the “thioimidate-only orthogonal strategy”. Discrimination amongst S-thiazolinyl (STaz) and S-benzoxazolyl (SBox) anomeric leaving group was achieved by fine-tuning of the activation conditions. Preferential glycosidation of a certain thioimidate is not simply determined by the strength of activating reagents; instead, the type of activation – direct vs. indirect – comes to the fore and plays the key role.

Traditional linear approaches to oligosaccharide assembly are often cumbersome and consequently the availability of complex glycostructures remains insufficient to address the challenges of modern glycosciences.1 Recent improvements in strategies for oligosaccharide assembly, have significantly shortened the number of synthetic steps required by minimizing protecting group manipulations between glycosylation steps.2 One of the most flexible assembly strategies is the orthogonal concept.3 Unlike the armed-disarmed approach,4 the orthogonal activation is not reliant on the nature of the protecting groups, which can interfere with stereoselectivity. The only requirement for the orthogonal approach is a set of two orthogonal leaving groups and a pair of suitable activators. Unfortunately, this simple concept is still limited to the following two examples: Ogawa’s S-ethyl and fluoride,3 and thioimidate S-thiazolinyl (STaz) and S-alkyl/aryl.5 In addition, a related, albeit less flexible, semi-orthogonal approach with the use of S-ethyl and O-pentenyl glycosides was reported,6 and was recently extended to fluoride/pentenyl leaving groups.7

Overall, the orthogonal strategy is an excellent concept for flexible sequencing of oligosaccharides that remains under explored, with too few examples to become universal.

The excellent glycosyl donor properties of glycosyl thioimidates and their unique activation conditions have led to a number of useful developments for oligosaccharide synthesis, including the orthogonal approach.5 From our previous studies we had determined the S-benzoxazolyl (SBox) glycosyl donors8 to be significantly more reactive than their STaz counterparts,5 and, although direct selective activations of the SBox donors over STaz acceptors were reported in the presence of Cu(OTf)2,5 no comprehensive side-by-side comparisons had been performed.

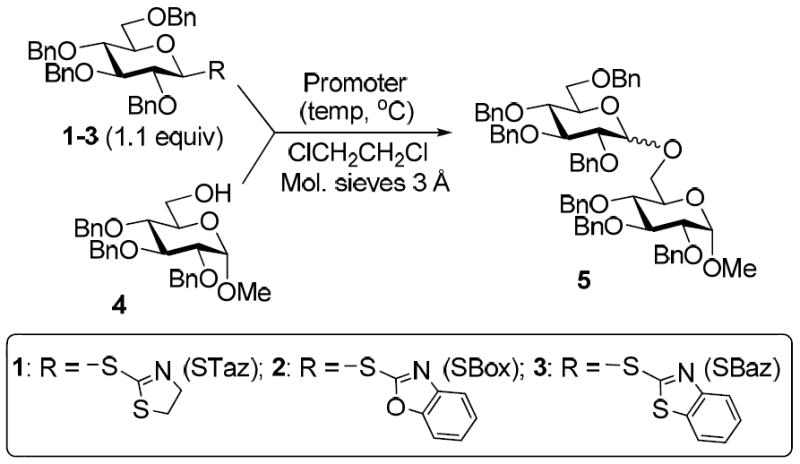

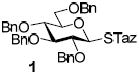

With the main purpose of determining relative reactivity patterns of thioimidates, we set-up a series of glycosidations including STaz,5 SBox,8 and structurally related Mukaiyama’s S-benzothiazolyl (SBaz) derivatives.9 All reactions of benzylated glycosyl donors 1-3 with glycosyl acceptor 4 promoted with MeOTf were very effective, and disaccharide 5 was obtained in high yields (Table 1). Although the disparity amongst the reaction times was unremarkable, it was evident that glycosidation of the STaz glycoside 1 (entry 1) was about two times slower than that of its SBox counterpart 2 (entry 2), with the reactivity of the SBaz glycoside 3 (entry 3) somewhere in the middle.

Table 1.

Alkylation-initiated glycosidation of benzylated thioimidates 1-3

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | donor | Promoter (equiv, temp) | time | product 5 (yield, α/β) |

| 1 | 1 | MeOTf (3, rt) | 0.75 h | (87%, 1.4/1) |

| 2 | 2 | MeOTf (3, rt) | 0.33 h | (88%,1.6/1) |

| 3 | 3 | MeOTf (3, rt) | 0.58 h | (89%, 1.6/1) |

| 4 | 1 | MeI (9, rt) | 120 h | (89%, 8.0/1) |

| 5 | 2 or 3 | MeI (9-15, rt) | 120 h | no reaction |

| 6 | 1 | BnBr (3, 55 °C) | 24 h | (90%, 3.5/1) |

| 7 | 2 | BnBr (3-9, 55°C) | 120 h | (traces) |

| 8 | 3 | BnBr (3-9, 55°C) | 120 h | no reaction |

To gain better control of the glycosylations and to achieve a more precise differentiation of reactivity between the different thioimidates, we turned to investigating other activators. Amongst these, results obtained with common alkylating (and acylating) reagents were of particular attractiveness. For example, MeI was only effective for glycosidation per-benzylated STaz glycoside 1 (entry 4). Surprisingly, when these reaction conditions were applied to the glycosidation of expectedly more reactive SBox and SBaz glycosides, no glycosylation took place (entry 5). Also BnBr was only effective for glycosidation STaz derivative 1, whereas glycosyl donors 2 or 3 gave only trace amounts of products (entries 6-8).

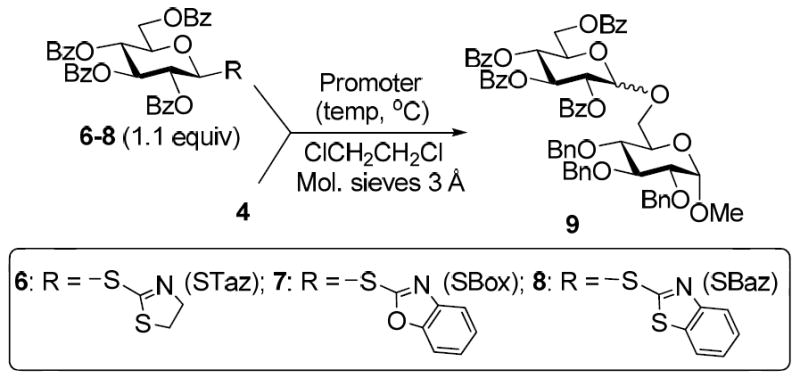

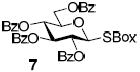

Subsequently, similar observations have been made with less reactive per-benzoylated glycosyl donors. Thus, all reactions of benzoylated glycosyl donors 6-8 with glycosyl acceptor 4 promoted with MeOTf were very effective, and disaccharide 9 was obtained in high yields (Table 2, entries 1-3). With MeI though, no glycosidation of benzoylated glycosyl donors 6-8 took place (entry 4). BnBr was only effective for the STaz derivative 6, (entry 5), whereas glycosidation of glycosyl donors 7 or 8 gave no products (entry 6). It should be noted that all reactions with benzylated glycosyl donors (Table 1) were significantly faster than those with their benzoylated counterparts (Table 2).

Table 2.

Alkylation-initiated glycosidation of benzoylated thioimidates 6-8

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | donor | Promoter (equiv, temp) | time | product 9 (yield, α/β) |

| 1 | 6 | MeOTf (3, rt) | 2 h | (97%, β only) |

| 2 | 7 | MeOTf (3, rt) | 1 h | (95%, β only) |

| 3 | 8 | MeOTf (3, rt) | 2 h | (84%, β only) |

| 4 | 6-8 | MeI (9-15, rt) | 120 h | No reaction |

| 5 | 6 | BnBr (3, 55 °C) | 72 h | (79%, β only) |

| 6 | 7 or 8 | BnBr (3-9, 55°C) | 120 h | no reaction |

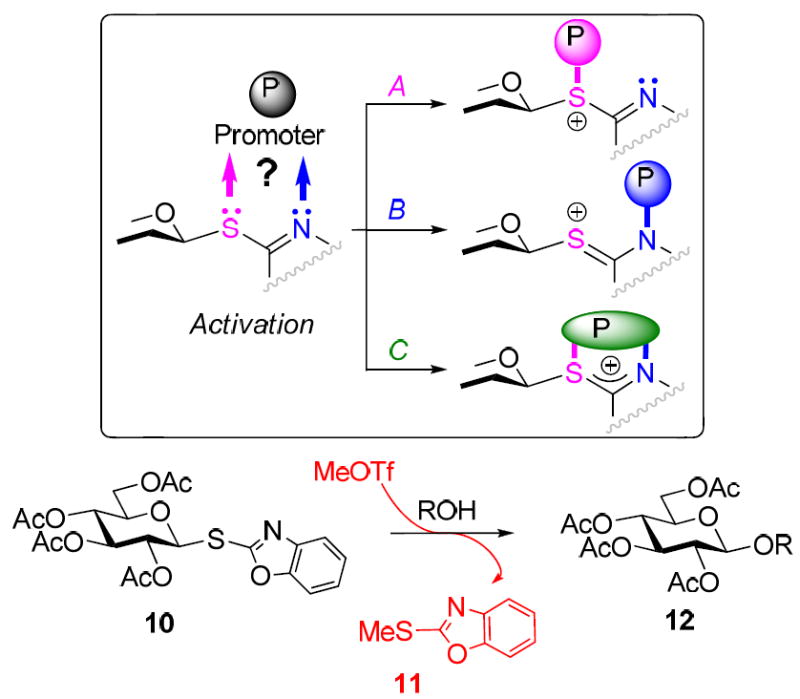

This discovery signified the gap in our understanding of the thioimidate activation and created a basis for the development of the STaz-SBox orthogonal strategy. The uniqueness of this approach would be that both leaving groups employed are of essentially the same class. Although certain pathways for the activation of thioimidates were postulated (Scheme 1),10,11 little proof had been available until our recent mechanistic study,8 wherein we showed that MeOTf-promoted activation of the SBox glycosyl donor 10 proceeds via the anomeric sulfur atom (direct activation). This was confirmed by isolating the departed S-methylated aglycone MeSBox (11, Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Activation of thioimidates: a study with SBox glycoside 10.8

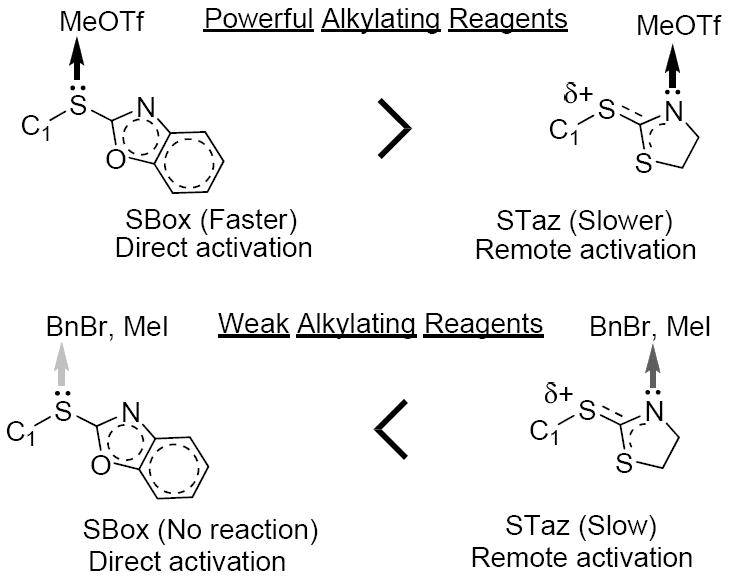

Since the exact nature of the STaz activation was not known, our working hypothesis for this study was based on our previous findings with the SBox moiety, taking into consideration the structural differences between the two moieties. We anticipated that the activation of the STaz moiety proceeds via the nitrogen (remote activation), as opposed to the direct activation of the SBox moiety. This remote activation of STaz would lead to a marginally slower reaction with a powerful promoter, such as MeOTf (refer to Tables 1 and 2). When weak alkylating reagents are used (MeI, BnBr), a powerful nucleophile is needed to replace the iodine or bromine, respectively. Evidently, this can be predominantly achieved with STaz glycosides that bear the reactive nitrogen atom, but not with the SBox glycosides, which can only be activated via the exocyclic sulfur8 (Figure 1). For comparison, previous reports suggest that SPh glycosides do not react with MeI (direct activation), while S-pyridyl derivatives do (remote activation is postulated).11

Figure 1.

Working hypothesis for thioimidate activation.

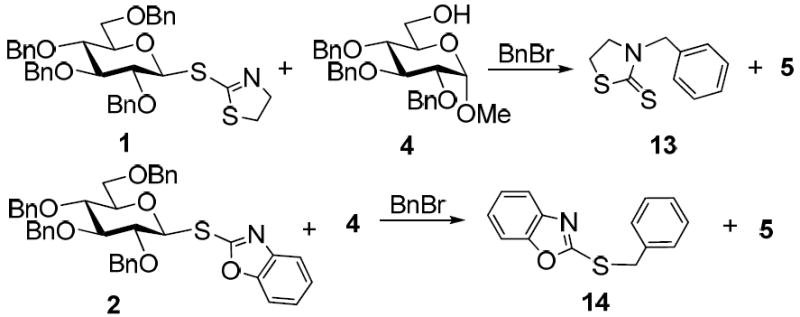

The credibility of this working hypothesis was verified by a series of experiments in which glycosyl donor 1 was reacted with the standard acceptor 4 in the presence of BnBr (Scheme 2). Upon disappearance of 1, the reaction mixture was concentrated in vacuo and the high running UV-active spot, corresponding to the benzylated aglycone, was separated from the disaccharide product 5 by column chromatography on silica gel. The structure of the isolated alkylated aglycone was assigned as thioamide 13 (BnNTaz) by X-ray (see the SI) and UV (λ=277 nm, C=S).

Scheme 2.

Mechanism of thioimidate activation with BnBr.

A similar reaction between 2 and 4 was significantly slower, nevertheless, we succeeded in isolating the departed aglycone, which was assigned as thioimide 14 (BnSBox) by X-Ray (see the SI) and UV (λ=280, 287 nm, C=N), as anticipated. To exclude the impact of tautomerization of the products both reactions were monitored by HPLC (see the SI).

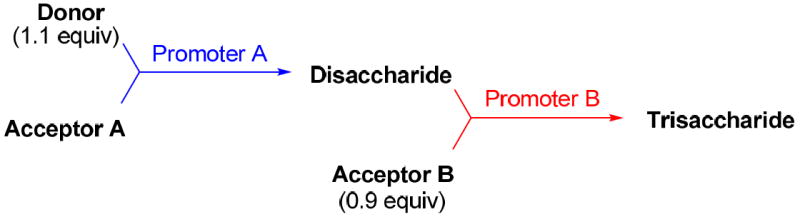

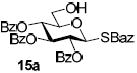

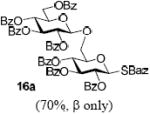

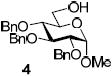

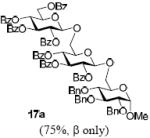

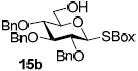

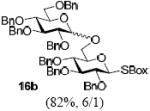

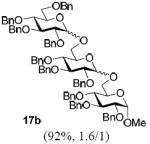

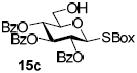

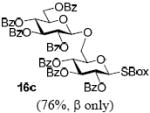

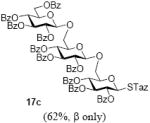

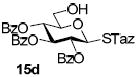

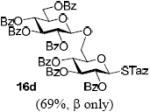

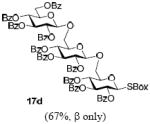

With a better understanding of the mechanistic pathway, we were well positioned to undertake further studies of expeditious oligosaccharide assembly. First, the activation of STaz donors 1 and 6 over SBaz/SBox acceptors 15a-c was investigated in the presence of BnBr or MeI. As a result, disaccharides 16a-c were obtained in good yields (70-82%, Table 3). Conversely, SBox donor 7 was also activated over the STaz acceptor 15d. This activation could be accomplished in the presence of a variety of activators, amongst which Bi(OTf)3 was the most promising; disaccharide 16d was obtained in 69% yield. The terminal SBox moieties of 16b or 16c could be glycosidated either with model acceptor 4 or with STaz acceptor (15d). Conversely, the STaz moiety of 16d could be glycosidated with 4 or activated over the SBox acceptor (15c). The resulting trisaccharides 17a-d were isolated in 62-92% yields (Table 3), with 1,6-anydro and hemiacetal being the major byproducts identified. Among trisaccharides generated, 17c and 17d can be used in subsequent sequencing.

Table 3.

Orthogonal activations for oligosaccharide synthesis.

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | donor | acceptor A | promoter A a | disaccharide (yield, α/β) | acceptor B | promoter B a | trisaccharide (yield, α/β) |

| 1 |  |

|

BnBr |  |

|

AgBF4 |  |

| 2 |  |

|

MeI |  |

4 | AgOTf |  |

| 3 | 6 |  |

BnBr |  |

4 | AgOTf | 17a (72%, β only) |

| 4 | 16c | 15d | Bi(OTf)3 |  |

|||

| 5 |  |

|

Bi(OTf)3 |  |

4 | AgBF4 | 17a (81%, β only) |

| 6 | 16d | 15c | BnBr |  |

|||

Conditions: All glycosylations were performed in 1,2-dichloromethane in the presence of molecular sieves (3 Å). Promoters: BnBr (3 equiv, 55 °C); AgBF4 (3 equiv, rt); MeI (9 equiv, 55 °C); AgOTf (2 equiv, rt); Bi(OTf)3 (3 equiv, 0 °C → rt). Reaction time: 16a - 24 h, 16b – 16 h, 16c – 24 h, 16d – 1h, 17a – 30, 30, and 40 min (entries 1, 3, and 5, respectively), 17b – 15 min, 17c – 2 h, 17d – 36 h.

In conclusion, a mechanistic study of the alkylation pathway for the activation of glycosyl thioimidates has led to the development of the “thioimidate-only orthogonal strategy”. The synthesis of trisaccharides 17a-d clearly illustrates the entirely orthogonal character of the SBox and STaz derivatives. Further studies and application of the new concept to glycosylation of secondary glycosyl acceptors is currently under pursuit in our laboratory.

Supplementary Material

Experimental procedures, 1H and 13C NMR spectra for all new compounds, the crystal structure and geometrical parameters for 13 and 14. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank NIGMS (GM077170) and AHA (0660054Z, 0855743G) for financial support of this work, as well as NSF (MRI, CHE-0420497) for the purchase of the ApexII diffractometer. Dr. Winter and Mr. Kramer (UM – St. Louis) are thanked for HRMS determinations.

References

- 1.Prescher JA, Bertozzi CR. Nature Chem Bio. 2005;1:13–21. doi: 10.1038/nchembio0605-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Galonic DP, Gin DY. Nature. 2007;446:1000–1007. doi: 10.1038/nature05813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Seeberger PH, Werz DB. Nature. 2007;446:1046–1051. doi: 10.1038/nature05819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nicolaou KC, Mitchell HJ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2001;40:1576–1624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Danishefsky SJ, Bilodeau MT. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1996;35:1380–1419. [Google Scholar]; Roy R, Andersson FO, Letellier M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:6053–6056. [Google Scholar]; Boons GJ, Isles S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:3593–3596. [Google Scholar]; Douglas NL, Ley SV, Lucking U, Warriner SL. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 1. 1998:51–65. [Google Scholar]; Zhang Z, Ollmann IR, Ye XS, Wischnat R, Baasov T, Wong CH. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:734–753. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kanie O, Ito Y, Ogawa T. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:12073–12074. [Google Scholar]; Ito Y, Kanie O, Ogawa T. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1996;35:2510–2512. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fraser-Reid B, Udodong UE, Wu ZF, Ottosson H, Merritt JR, Rao CS, Roberts C, Madsen R. Synlett. 1992:927–942. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Demchenko AV, Pornsuriyasak P, De Meo C, Malysheva NN. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:3069–3072. doi: 10.1002/anie.200454047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Pornsuriyasak P, Demchenko AV. Chem Eur J. 2006;12:6630–6646. doi: 10.1002/chem.200600262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Demchenko AV, De Meo C. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:8819–8822. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lopez JC, Uriel C, Guillamon-Martin A, Valverde S, Gomez AM. Org Lett. 2007;9:2759–2762. doi: 10.1021/ol070753r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kamat MN, De Meo C, Demchenko AV. J Org Chem. 2007;72:6947–6955. doi: 10.1021/jo071191s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Kamat MN, Rath NP, Demchenko AV. J Org Chem. 2007;72:6938–6946. doi: 10.1021/jo0711844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mukaiyama T, Nakatsuka T, Shoda SI. Chem Lett. 1979:487–490. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanessian S, Bacquet C, Lehong N. Carbohydr Res. 1980;80:c17–c22. [Google Scholar]; Demchenko AV, Malysheva NN, De Meo C. Org Lett. 2003;5:455–458. doi: 10.1021/ol0273452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mereyala HB, Reddy GV. Tetrahedron. 1991;47:6435–6448. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Experimental procedures, 1H and 13C NMR spectra for all new compounds, the crystal structure and geometrical parameters for 13 and 14. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.