Abstract

Sleep related breathing disorders (SRBD) are a significant public health concern, with a prevalence in the US general population of ∼2% of women and ∼4% of men. Although significant strides have been made in our understanding of these disorders with respect to epidemiology, risk factors, pathogenesis and consequences, work to understand these factors in terms of the underlying cellular, molecular and neuromodulatory processes remains in its infancy. Current primary treatments are surgical or mechanical, with no drug treatments available. Basic investigations into the neurochemistry and neuropharmacology of sleep-related changes in respiratory pattern generation and modulation will be essential to clarify the pathogenic processes underlying SRBD and to identify rational and specific pharmacotherapeutic opportunities. Here we summarize emerging work suggesting the importance of vagal afferent feedback systems in sleep related respiratory pattern disturbances and pointing toward a rich but complex array of neurochemical and neuromodulatory processes that may be involved.

Introduction

The past two decades have witnessed rapidly increasing knowledge regarding sleep-related breathing disorders (SRBD). Significant strides have been made in our understanding of these disorders with respect to epidemiology and risk factors, pathogenesis, clinical and behavioral consequences, and appropriate diagnostic and treatment strategies. Still, work to understand these factors in terms of the underlying cellular, molecular and neuromodulatory processes remains in its infancy.

Sleep related breathing disorders are a significant public health concern, with a prevalence in the US general population of ∼2% of women and ∼4% of men (Young et al. 1993; Young et al. 1997). Accumulating evidence suggests that morbid consequences of untreated SRBD include hypertension, coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, arrhythmia, stroke, dementia, depression, cognitive dysfunction, sexual dysfunction, and injury due to accidents (for recent reviews see: (El-Ad and Lavie 2005; Thorpy 2006; Parati et al. 2007; Saunamaki and Jehkonen 2007). Patients with SRBD can exhibit a spectrum of respiratory disturbances during sleep, including: central apneas, operationally defined as cessation of respiratory effort for more than 10 seconds; obstructive apneas, characterized by continued inspiratory efforts against an occluded upper airway; mixed apneas, which present with an initial central component followed immediately by an obstructive component; hypopneas, associated with partial collapse of the upper airway and an attendant drop in pulmonary ventilation; and respiratory event-related arousals, characterized by increased inspiratory force generation leading to arousal from sleep but not impaired gas exchange (1999).

Disordered breathing events may be a normal phenomenon during transitions from wakefulness to sleep and during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep in man (Bulow 1963; Webb 1974). However, when the frequency of disordered breathing events becomes high, daytime symptoms and clinical sequellae can result. A generalized “respiratory disturbance index” (RDI), calculated as the frequency of disordered breathing events (apneas, hypopneas or transient oxygen desaturations) during sleep, is most often used clinically to assess the severity of the disease. Although early studies suggested that healthy subjects rarely exhibited an RDI > 5, it has thus far proven impossible to identify a firm threshold RDI above which behavioral or clinical morbidity results.

Pathogenesis of SRBD

Incomplete agreement exists regarding mechanisms underlying the generation or termination of apneas during sleep. In general, patients with primarily obstructive apnea have redundant pharyngeal tissue with relatively narrow and collapsible upper airways. These anatomical defects can predispose to upper airway collapse during sleep, launching the vicious cycle of sleep-apnea-arousal-ventilation that is a hallmark of the syndrome (Arens and Marcus 2004; Martins et al. 2007). It now appears that in most patients, total (apnea) or partial (hypopnea) collapse of the pharyngeal airway during sleep arises from both deficient airway anatomy and state-related influences on airway muscle function. Some evidence suggests that augmented reflex activation of pharyngeal dilator muscles, possibly by phasic negative intraluminal pressure, is an important compensatory mechanism during wakefulness in patients with obstructive sleep apnea – a mechanism that is blunted or lost during sleep (Jordan and White 2008).

Other findings argue that unstable or desynchronized respiratory drive is an important factor contributing to SRBD. In circumstances where the upper airway is predisposed to collapse by anatomical or neuromuscular factors mixed and obstructive events may predominate, whereas in conditions where the upper airway is mechanically stable, central events may predominate. It has been argued that general instability of ventilatory control produces fluctuating drive to the diaphragm and to the pharyngeal muscles in SRBD (Skatrud and Dempsey 1983; Onal et al. 1986). Such fluctuations cause attendant alterations in upper airway resistance and collapsibility even in normal individuals (Onal et al. 1986; Warner et al. 1987). Brainstem phasic perturbations characteristic of REM sleep also impact on respiratory rhythmogenesis and motor output coordination (Millman et al. 1988; Dunin-Barkowski and Orem 1998), a factor that may contribute to the diathesis of disordered breathing often associated with this sleep state (Lugaresi et al. 1978; Arens and Marcus 2004; Martins et al. 2007).

These viewpoints argue that detailed knowledge of the neurochemical control and modulation of upper airway motor neurons and respiratory rhythm generating and premotor integrating neurons should provide insights toward pharmacologic treatment strategies for SRBD. Although no generally effective pharmacologic treatments for obstructive SRBD have yet been identified, knowledge of these processes is accumulating from a range of animal studies. These studies are detailed elsewhere in this issue. For this reason, we will here focus on evidence regarding the potential importance of vagal afferent neurons in the pathogenesis of SRBD, and the emerging neuropharmacology in this area.

Vagus Nerve Apneic Reflexes

Lung inflation is well known to elicit inspiratory termination and expiratory apnea via activation of slowly adapting stretch receptors. These receptors are innervated by myelinated fibers of vagus nerve afferent neurons residing in the nodose ganglia (Kubin et al. 2006). Apnea in the context of cough can be elicited by activation of rapidly adapting receptors that respond both to large changes in lung volume and to inhaled irritants (Kubin et al. 2006). These receptors also receive myelinated fibers from nodose ganglion neurons. Activation of non-myelinated C fiber nodose-afferents innervating other airway receptors sensitive to mechanical, chemical or thermal stimuli also can provoke reflex apnea (Kubin et al. 2006). Laryngeal irritant (and thermal) receptors also are innervated mostly by the nodose ganglia (Nishino 2000) and their activation can provoke reflex apnea (Nishino 2000; Thach 2007). All of these reflexes are physiologically active and play roles in protecting the airways and in regulating ongoing respiratory pattern. Experimental apnea can be evoked by activation of these pathways using mechanical, chemical, or electrical stimulation.

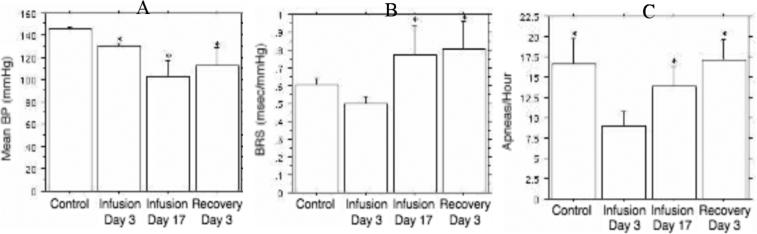

Yoshioka and coworkers demonstrated that intravenous bolus injection of serotonin evoked immediate apnea of dose-dependent duration (Yoshioka et al. 1992). These apneas resulted from vagal activation, in that supra-nodose vagotomy eliminated the response (Yoshioka et al. 1992). The serotonin-evoked reflex apnea also was blocked by pretreatment with a serotonin type 3 (5-HT3) receptor antagonist. The potential relevance of vagal afferent tone and vagal reflexes to SRBD was first suggested by Carley and Radulovacki who demonstrated that intraperitoneal injection of serotonin provoked an increase of spontaneous sleep-related apnea in a rat model of central SRBD (Carley and Radulovacki 1999b). Although not definitive, it is likely that this resulted from vagal activation, because serotonin does not cross the blood brain barrier. The impact of serotonin on SRBD also was highly state dependent: RDI increased almost 3-fold during REM sleep over a 3-hour recording period (Fig. 1), but no effect was observed on RDI during non-REM (NREM) sleep, or on respiratory rate, minute ventilation, heart rate, or blood pressure. Moreover, the serotonin-induced increase of REM RDI was completely blocked by a low dose of the 5-HT3 receptor antagonist GR38032F, or ondansetron (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Effects of intraperitoneal 5-HT (0.79 mg/kg) on RDI during REM sleep. Points depict mean values in 1-hour recording intervals for 10 animals. With respect to placebo injection, 5-HT evoked a 3-fold increase in RDI during REM sleep for a period of 3 hours. Pretreatment with 0.1 mg/kg ondansetron completely blocked this effect. * p < 0.001 versus control.

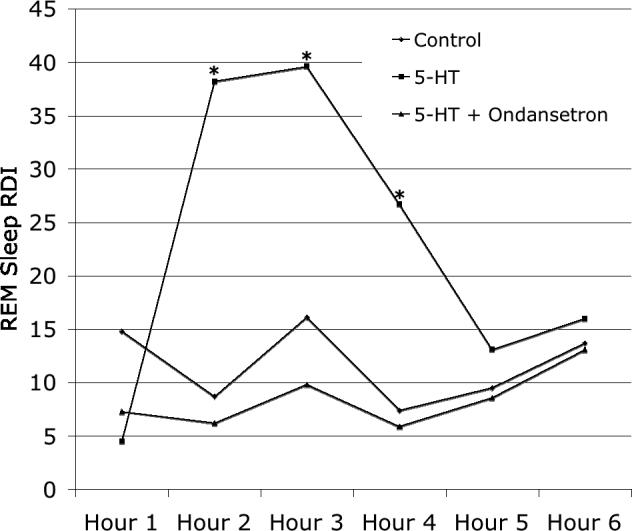

Carley and coworkers further demonstrated that two other pharmacologic activators of vagal afferents, capsaicin (Hedner et al. 1985) and protoveratrine (Clozel et al. 1990) also increased spontaneous SRBD in rats (Trbovic et al. 1997; Carley et al. 2004). Interestingly, unlike serotonin, capsaicin, which activates primarily c-fibers, and protoveratrine, which stimulates free nerve endings, increased apnea expression only during NREM sleep (Figs. 2 and 3, respectively).

Fig. 2.

Effect of c-fiber activation by capsaicin on RDI in NREM and REM sleep. Bars are mean ± SE in 9 animals. * p < 0.05 versus control.

Fig. 3.

Effects of protoveratrine A on RDI during NREM and REM sleep. Bars indicate mean ± SE for 10 animals. * p < 0.02 versus control ** p < 0.001 versus control

Neurochemistry of the Nodose Ganglion

The observation that pharmacologic stimulation of vagal afferents can exacerbate the expression of spontaneous apnea during all stages of sleep provided a rationale for attempting to stabilize respiratory pattern during sleep by using neuromodulators to reduce excitability in afferent vagal systems. The visceral sensory neurons of the nodose ganglion that innervate cardiorespiratory structures have central axons that transmit information to the central nervous system, terminating in the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS). A growing body of evidence shows that neurochemically and functionally distinct populations of neurons can be identified within the nodose ganglia (Browning 2003). Recent work suggests that alterations in vagal afferent excitability may contribute to the development or maintenance of clinical disorders (Holtmann et al. 1998).

Neurochemistry of the nodose ganglion is very rich (for a review, see (Zhuo et al. 1997). Numerous neurotransmitters and neuropeptides have been identified within nodose neurons, including: glutamate, serotonin, acetylcholine, substance P, neurokinin A, vasoactive intestinal peptide, calcitonin gene-related peptide, galanin, enkephalin, somatostatin, cholecystokinin, neuropeptide Y, calcium binding proteins and other neuroactive molecules such as nitric oxide. Moreover, expression of these molecules is not static, and can respond to changes in environmental conditions and activity at modulatory sites. This potential plasticity is further amplified by the fact that, while classical neurotransmitters are manufactured at the central nerve terminals, neuropeptides are made in the nodose neuron cell bodies and transported centrally to the NTS. It remains unclear whether there is a functional differentiation for the roles of these many potential neuroactive substances within nodose afferent neurons (Zhuo et al. 1997).

Nodose ganglion neurons also are imbued with a rich array of receptors for neurotransmitters and neuromodulators. Many studies demonstrate the presence of 5-HT3 binding sites in the nodose ganglion, and 5-HT depolarizes these neurons by increasing membrane conductance (Kilpatrick et al. 1989; Zhuo et al. 1997). Interestingly, cannabinoid type 1 (CB1) receptors also are expressed on nodose ganglion cell bodies (Pertwee 1999) and cannabinoid agonists block the depolarizing effect of 5-HT on these cells (Fan 1995). This suggests that the excitability of vagal afferent systems may potentially be decreased by 5-HT3 antagonists or CB1 agonists, alone or in combination.

Angiotensin receptors are manufactured in nodose ganglion cell bodies and transported bidirectionally (Zhuo et al. 1997). Angiotensin II microinjection into the NTS attenuates vagal baroreflexes, but respiratory effects have not been examined. Type A and B receptors for cholecystokinin (CCKA and CCKB, respectively) are expressed by a subpopulation of nodose ganglion cells and processes. CCK application induces a rapid fall in membrane resistance and depolarization of isolated nodose ganglion cells (Dun et al. 1991) suggesting that peripheral administration of CCK antagonists may reduce the activity of vagal afferent systems. Indirect evidence for the existence of both low and high affinity neurotrophin receptors within nodose ganglia arises from in situ hybridization immunohistochemistry for their mRNAs (Zhuo et al. 1997). The level of protein expression and functional significance of these receptors remains to be demonstrated in vagal sensory neurons.

Vagal afferent neurons also express vanilloid receptors. At least 4 distinct subtypes of vanilloid receptor have now been identified (TRPV1 – TRPV4) (Bender et al. 2005) and several groups of endogenous vanilloid receptor ligands have been identified, providing a rationale for therapeutic uses of vanilloid receptor ligands (Van Der Stelt and Di Marzo 2004). At low concentrations, intravenous capsaicin acts at TRPV1 receptors to provoke vagal reflex apnea, and as demonstrated in Fig. 2, intraperitoneal capsaicin evokes spontaneous sleep apnea during NREM sleep. Interestingly, at higher concentrations, exposure to vanilloid agonists produces initial excitation of vagus nerve afferent fibers followed by a prolonged refractory state during which these neurons are unresponsive to physiological or pharmacological stimuli (Szallasi 2001). This form of desensitization is associated with profound changes in the expression of receptors and neuromediators in the affected cells, and these changes may last for weeks following a single agonist exposure (Szallasi and Blumberg 1996).

Prostanoids are a family of autocrine mediators that act through multiple G-protein coupled receptors. Of relevance here, prostanoid receptors are widely expressed in both the peripheral and central nervous systems. Important endogenous prostanoids include at least the prostaglandin D, E, F, and I families and the thromboxanes. As reviewed by Ashby (Ashby 1998), prostanoid receptors include at least: DP, EP1, EP2, EP3 (6 isoforms), EP4, FP, IP, and TP (2 isoforms). Administration of prostanoids stimulates rapidly adapting pulmonary stretch receptors (Mohammed et al. 1993) and intravenous administration of prostaglandin E1 or E2, or thromboxane A2 evoke vagal reflex apnea, and prostaglandin E2 exacerbates capsaicin-induced reflex apnea (Lee and Morton 1995).

Effects of Pharmacologic Modulation of the Afferent Vagus on SRBD

As outlined above, the sensory vagus nerve plays a physiologic role in setting ongoing respiratory pattern and a protective role in the context of lung over-inflation, irritant inhalation, or fluid/foreign-body aspiration. Pharmacologic stimulation of the afferent vagal pathways can evoke immediate dose-dependent reflex apnea or increased spontaneous sleep-related apnea in rats, depending on the route of administration. Additional studies have explored the hypothesis that pharmacologically decreasing excitability in the afferent vagus nerves may result in reductions in SRBD in animal model systems.

Although intraperitoneal injection of 0.1 mg/kg ondansetron did not change RDI from baseline placebo-control (Fig. 1), treatment of rats with a dose of 1.0 mg/kg eliminated REM-sleep apnea for a period of 4 hours after injection (Fig. 4), despite the fact that REM sleep expression was only slightly reduced over this interval (Radulovacki et al. 1998). NREM apneas also were reduced, but only by 50% and only during the first two hours after drug administration (Radulovacki et al. 1998). These effects of ondansetron were reproduced in the English bulldog – a natural animal model of obstructive SRBD (Veasey et al. 2001). It is possible that decreasing afferent vagal tone with effective doses of ondansetron results in a net activation (disinhibition) of drive to both the respiratory pattern generator and the upper airway muscles. In support of this possibility, Fenik et al. observed that peripherally administered ondansetron resulted in increased respiratory phasic activation of hypoglossal (upper airway) motor neurons (Fenik et al. 2001). Radulovacki et al. observed that ondansetron doses sufficient to reduce RDI also increased minute ventilation in conscious rats (Radulovacki et al. 1998).

Fig. 4.

Effect of 1.0 mg/kg intraperitoneal ondansetron on RDI during REM sleep. Points are mean values for 8 animals. Ondansetron eliminated apnea during REM sleep for 4 hours and reduced apnea by 65% during the fifth and sixth hours after treatment (p < 0.001 at each time point versus control).

Based on these findings with ondansetron, several additional serotonin antagonist drugs were screened in the rat model. As depicted in Fig. 5., during all sleep stages, at a dose of 1.0 mg/kg ondansetron, a selective 5-HT3 antagonist, produced an average reduction in RDI of approximately 50% with respect to placebo conditions. In contrast, ketanserin, an 5-HT antagonist at type 2 receptors, did not reduce apnea expression (Radulovacki et al. 2002). Mirtazapine, a 5-HT2 and 5-HT3 antagonist and central 5-HT release promoter, yielded a 50% reduction in RDI during both NREM and REM sleep (Carley and Radulovacki 1999a). R-zacopride, a 5-HT3 antagonist and 5-HT4 agonist, yielded a reduction in RDI similar to mirtazapine, but the effects persisted for only 2 hours after injection (Carley et al. 2001a).

Fig. 5.

Activity of a screening panel of 5-HT antagonist drugs in reducing RDI in a rat model of central SRBD. Animals served as their own controls (placebo injection condition) during each test. Ordinate represents the ratio of RDI (AHI during combined NREM and REM sleep) under active drug normalized by RDI for the same animal under placebo recording conditions. No change from placebo was thus represented by a value of 1.0 (heavy horizontal rule). The bars reflect the mean value for the group of test animals at the lower end and the upper 95% confidence interval at the upper end. Thus any bar that intersects the unity line had no significant effect on RDI (p > 0.05). Lower and shorter bars indicate greater and more consistent drug-induced reductions in RDI.

Cannabimimetic agents also showed an ability to reduce RDI, as depicted in Fig. 6. Δ9THC, a CB1 and CB2 receptor agonist produced a 40% to 50% reduction in RDI during both NREM and REM sleep at a dose of 10.0 mg/kg. Oleamide, an endogenous cannabinoid molecule, produced similar effects on RDI at doses of 1.0 mg/kg and 10.0 mg/kg (Fig. 6). Oleamide also increased the expression of deep slow-wave NREM sleep (Carley et al. 2002). Despite their similar effects on RDI, Δ9THC and oleamide produced opposite effects on breathing frequency at the highest dose: Δ9THC decreased breathing frequency by 17 breaths/minute (15%) whereas oleamide increased breathing frequency by 16 breaths per minute (14%) (Carley et al. 2002). Each of these cannabimimetic drugs also was able to block the 5-HT-induced increase of RDI at a dose (0.1 mg/kg) that had no independent effect on baseline RDI.

Fig. 6.

Impact of Δ9THC and oleamide on RDI in an individual animal recorded on three occasions (A), and for a group of 11 animals (B and C). Panel A depicts separate 6-hour recordings made at one week intervals immediately after injections of vehicle, Δ9THC or oleamide (10.0 mg/kg for each). The upper trace of each recording presents the duration of each individual breath during the recording. Breaths exceeding 2.5s duration represent at least two “missed” breaths and are scored as apnea. It is apparent that the number (and frequency) of apneas is reduced after Δ9THC or oleamide injection in comparison to control. Bars in panels B and C represent mean ± SE for the groups and demonstrate dose-dependent reductions in both NREM and REM related RDI.

The CCKB receptor antagonist CR2945 produced a dose-dependent reduction of RDI versus control during both NREM and REM sleep (Fig. 7). Doses of 0.5 mg/kg and 5.0 mg/kg reduced RDI by 65% − 75% during NREM (p < 0.05) and REM (p < 0.02) sleep. Apnea duration, respiratory frequency and sleep stage percentages were not significantly affected (data not shown).

Fig. 7.

Impact of CCKB receptor antagonist CR2945 on RDI during NREM and REM sleep. Bars represent group mean ± SE for 9 animals. CR2945 produced significant reductions in RDI with respect to control in both NREM (p < 0.05 for doses of 0.5 and 5.0 mg/kg) and REM (p < 0.02 for all doses) sleep.

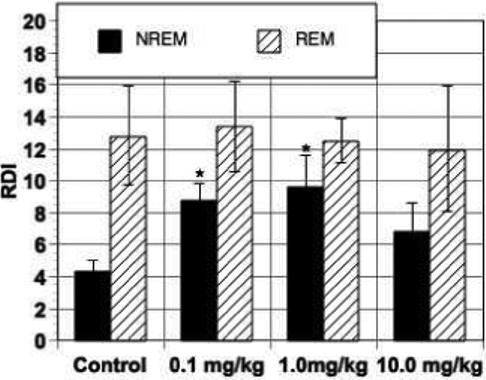

The angiotensin receptor antagonist losartan was tested during continuous infusion over a 17 day period (5.0 mg/kg/day) using subcutaneous osmotic pumps (Carley et al. 2001b). As expected, this treatment reduced mean blood pressure progressively from day 3 to day 17 of infusion; an effect that persisted for at least 3 days after losartan discontinuation (Fig. 8). Conversely, baroreflex sensitivity was increased after 17 but not 3 days of treatment, and this effect also persisted for at least 3 days after losartan discontinuation. In contrast, RDI was decreased by 50% on treatment day 3, a time point at which blood pressure or baroreflex effects were minimal or absent. By treatment day 17, however, RDI suppression by losartan was lost (Fig. 8). It is possible that this loss of effect reflected time-dependent alterations in the manufacture and transport of angiotensin receptors along the centrally or peripherally projecting axons of nodose ganglion neurons, alterations in the interactions between respiratory and cardiovascular pathways, or other factors that cannot be discriminated from the available data.

Fig. 8.

Mean blood pressure (A; mmHg), baroreflex sensitivity (B; ms/mmHg) and RDI (C; apneas/hour) during NREM sleep under control (saline) conditions, after 3 and 7 days of continuous losartan infusion (5 mg/kg/day by osmotic pump), and 3 days after losartan discontinuation. Bars indicate mean ± SE for 10 animals. * indicates p < 0.05 vs control (A, B), or p < 0.01 versus infusion day 3 (C).

Clinical Significance of Animal Model Data

Collectively, the studies outlined above provide a rationale for stabilizing respiratory pattern generation and possibly upper airway motor outputs by pharmacologically decreasing afferent vagal tone and/or excitability. They further support this conceptual framework by demonstrating that agents expected to increase or decrease vagal sensory neuron excitability, respectively, can indeed produce increased and decreased expression of spontaneous sleep-related apnea in natural animal models of SRBD. However, the clinical significance of these observations remains to be fully demonstrated.

For example, a single study has examined the effect of ondansetron in patients with obstructive sleep apnea, finding no effect of a single dose on RDI (Stradling et al. 2003). Interpretation of this finding is difficult, however, in that the dose tested (16 mg) was far below the effective doses needed in both rats and bulldogs (1 − 5 mg/kg). Conversely, a single small placebo-controlled crossover trial of mirtazapine in patients with sleep apnea syndrome also has been published (Carley et al. 2007). Here the results from animal and human studies were comparable: an approximate 50% reduction of RDI in both NREM and REM sleep across multiple doses. However, even such a finding does not necessarily represent clinical relevance. Sedation and appetite stimulation are two well-recognized side effects of mirtazapine. Because individuals with sleep apnea syndrome are characteristically obese and experience daytime sleepiness, these must be viewed as very negative side effects. In the apnea trial, even subjects who experienced a significant reduction in RDI did not feel more alert when taking mirtazapine (Carley et al. 2007). In light its significant negative side effect potential, mirtazapine is not viewed as an appropriate drug for clinical use in patients with sleep apnea (Carley et al. 2007).

In summary, an accumulating body of evidence from animal investigations supports the potential importance of vagal afferent pathways in the pathogenesis and/or therapy of SRBD. The neurochemistry and neuropharmacology of this pathway offers numerous possible targets for pharmacologic modulation. Defining the ultimate clinical relevance of these pathways in SRBD pathogenesis and treatment can only be accomplished with significant ongoing clinical and basic investigation.

Acknowledgment

Original work of the authors presented here supported in part by NIH grants AG016303 and HL070780.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Sleep-related breathing disorders in adults: recommendations for syndrome definition and measurement techniques in clinical research. The Report of an American Academy of Sleep Medicine Task Force. Sleep. 1999;22:667–689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arens R, Marcus CL. Pathophysiology of upper airway obstruction: a developmental perspective. Sleep. 2004;27:997–1019. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.5.997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashby B. Co-expression of prostaglandin receptors with opposite effects: a model for homeostatic control of autocrine and paracrine signaling. Biochem Pharmacol. 1998;55:239–246. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(97)00241-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender FL, Mederos YSM, Li Y, Ji A, Weihe E, Gudermann T, Schafer MK. The temperature-sensitive ion channel TRPV2 is endogenously expressed and functional in the primary sensory cell line F-11. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2005;15:183–194. doi: 10.1159/000083651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning KN. Excitability of nodose ganglion cells and their role in vago-vagal reflex control of gastrointestinal function. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2003;3:613–617. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2003.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulow K. Respiration and wakefulness in man. Acta Physiol scand. 1963;59:1–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carley DW, Depoortere H, Radulovacki M. R-zacopride, a 5-HT3 antagonist/5-HT4 agonist, reduces sleep apneas in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2001a;69:283–289. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00535-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carley DW, Olopade C, Ruigt GS, Radulovacki M. Efficacy of mirtazapine in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep. 2007;30:35–41. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carley DW, Paviovic S, Janelidze M, Radulovacki M. Functional role for cannabinoids in respiratory stability during sleep. Sleep. 2002;25:391–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carley DW, Pavlovic S, Malis M, Knezevic N, Saponjic J, Li C, Radulovacki M. C-fiber activation exacerbates sleep-disordered breathing in rats. Sleep Breath. 2004;8:147–154. doi: 10.1007/s11325-004-0147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carley DW, Radulovacki M. Mirtazapine, a mixed-profile serotonin agonist/antagonist, suppresses sleep apnea in the rat. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999a;160:1824–1829. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.6.9902090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carley DW, Radulovacki M. Role of peripheral serotonin in the regulation of central sleep apneas in rats. Chest. 1999b;115:1397–1401. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.5.1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carley DW, Trbovic S, Radulovacki M. Losartan, an angiotensin AT1 receptor antagonist, modulated sleep apnea expression in spontaneously hypertensive (SHR) rats. Sleep Res Online. 2001b;4:7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Clozel JP, Pisarri TE, Coleridge HM, Coleridge JC. Reflex coronary vasodilation evoked by chemical stimulation of cardiac afferent vagal C fibres in dogs. J Physiol. 1990;428:215–232. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dun NJ, Wu SY, Lin CW. Excitatory effects of cholecystokinin octapeptide on rat nodose ganglion cells in vitro. Brain Res. 1991;556:161–164. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90562-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunin-Barkowski WL, Orem JM. Suppression of diaphragmatic activity during spontaneous ponto-geniculo-occipital waves in cat. Sleep. 1998;21:671–675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Ad B, Lavie P. Effect of sleep apnea on cognition and mood. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2005;17:277–282. doi: 10.1080/09540260500104508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan P. Cannabinoid agonists inhibit the activation of 5-HT3 receptors in rat nodose ganglion neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1995;73:907–910. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.2.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenik P, Ogawa H, Veasey SC. Hypoglossal nerve response to 5-HT3 drugs injected into the XII nucleus and vena cava in the rat. Sleep. 2001;24:871–878. doi: 10.1093/sleep/24.8.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedner J, Hedner T, Jonason J. Capsaicin and regulation of respiration: interaction with central substance P mechanisms. J Neural Transm. 1985;61:239–252. doi: 10.1007/BF01251915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtmann G, Goebell H, Jockenhoevel F, Talley NJ. Altered vagal and intestinal mechanosensory function in chronic unexplained dyspepsia. Gut. 1998;42:501–506. doi: 10.1136/gut.42.4.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan AS, White DP. Pharyngeal motor control and the pathogenesis of obstructive sleep apnea. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2008;160:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick GJ, Jones BJ, Tyers MB. Binding of the 5-HT3 ligand, [3H]GR65630, to rat area postrema, vagus nerve and the brains of several species. Eur J Pharmacol. 1989;159:157–164. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90700-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubin L, Alheid GF, Zuperku EJ, McCrimmon DR. Central pathways of pulmonary and lower airway vagal afferents. J Appl Physiol. 2006;101:618–627. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00252.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee LY, Morton RF. Pulmonary chemoreflex sensitivity is enhanced by prostaglandin E2 in anesthetized rats. J Appl Physiol. 1995;79:1679–1686. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.79.5.1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugaresi E, Coccagna G, Montovani M. In: Hypersomnia with periodic apneas. Weitzman E, editor. Advances in Sleep Research, Spectrum Publications; New York: 1978. pp. 68–70. [Google Scholar]

- Martins AB, Tufik S, Moura SM. Physiopathology of obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome. J Bras Pneumol. 2007;33:93–100. doi: 10.1590/s1806-37132007000100017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millman RP, Knight H, Kline LR, Shore ET, Chung DC, Pack AI. Changes in compartmental ventilation in association with eye movements during REM sleep. J Appl Physiol. 1988;65:1196–1202. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1988.65.3.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed SP, Higenbottam TW, Adcock JJ. Effects of aerosol-applied capsaicin, histamine and prostaglandin E2 on airway sensory receptors of anaesthetized cats. J Physiol. 1993;469:51–66. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishino T. Physiological and pathophysiological implications of upper airway reflexes in humans. Jpn J Physiol. 2000;50:3–14. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.50.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onal E, Burrows DL, Hart RH, Lopata M. Induction of periodic breathing during sleep causes upper airway obstruction in humans. J Appl Physiol. 1986;61:1438–1443. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1986.61.4.1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parati G, Lombardi C, Narkiewicz K. Sleep apnea: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and relation to cardiovascular risk. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;293:R1671–1683. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00400.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertwee RG. Evidence for the presence of CB1 cannabinoid receptors on peripheral neurones and for the existence of neuronal non-CB1 cannabinoid receptors. Life Sci. 1999;65:597–605. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(99)00282-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radulovacki M, Pavlovic S, Rakic A, Janelidze M, Shermulis L, Carley D. Ketanserin, a 5-HT2 receptor antagonist, reduces sleep apneas in rats. Res Comm Biol Psychol Psychiat. 2002;26:3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Radulovacki M, Trbovic SM, Carley DW. Serotonin 5-HT3-receptor antagonist GR 38032F suppresses sleep apneas in rats. Sleep. 1998;21:131–136. doi: 10.1093/sleep/21.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunamaki T, Jehkonen M. Depression and anxiety in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a review. Acta Neurol Scand. 2007;116:277–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2007.00901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skatrud JB, Dempsey JA. Interaction of sleep state and chemical stimuli in sustaining rhythmic ventilation. J Appl Physiol. 1983;55:813–822. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1983.55.3.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stradling J, Smith D, Radulovacki M, Carley D. Effect of ondansetron on moderate obstructive sleep apnoea, a single night, placebo-controlled trial. J Sleep Res. 2003;12:169–170. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2003.00342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szallasi A. Vanilloid receptor ligands: hopes and realities for the future. Drugs Aging. 2001;18:561–573. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200118080-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szallasi A, Blumberg PM. Vanilloid receptors: new insights enhance potential as a therapeutic target. Pain. 1996;68:195–208. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(96)03202-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thach BT. Maturation of cough and other reflexes that protect the fetal and neonatal airway. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2007;20:365–370. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorpy M. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome is a risk factor for stroke. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2006;6:147–148. doi: 10.1007/s11910-996-0037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trbovic SM, Radulovacki M, Carley DW. Protoveratrines A and B increase sleep apnea index in Sprague-Dawley rats. J Appl Physiol. 1997;83:1602–1606. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.83.5.1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Stelt M, Di Marzo V. Endovanilloids. Putative endogenous ligands of transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 channels. Eur J Biochem. 2004;271:1827–1834. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veasey SC, Chachkes J, Fenik P, Hendricks JC. The effects of ondansetron on sleep-disordered breathing in the English bulldog. Sleep. 2001;24:155–160. doi: 10.1093/sleep/24.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner G, Skatrud JB, Dempsey JA. Effect of hypoxia-induced periodic breathing on upper airway obstruction during sleep. J Appl Physiol. 1987;62:2201–2211. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1987.62.6.2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb P. Perodic breathing during sleep. J Appl Physiol. 1974;37:899–903. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1974.37.6.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka M, Goda Y, Togashi H. Pharmacological characterization of 5-hydroxytryptamine-induced apnea in the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;260:917–924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young T, Evans L, Finn L, Palta M. Estimation of the clinically diagnosed proportion of sleep apnea syndrome in middle-aged men and women. Sleep. 1997;20:705–706. doi: 10.1093/sleep/20.9.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, Skatrud J, Weber S, Badr S. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults [see comments]. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1230–1235. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304293281704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuo H, Ichikawa H, Helke CJ. Neurochemistry of the nodose ganglion. Prog Neurobiol. 1997;52:79–107. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(97)00003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]