Abstract

IL-10 is a critical cytokine in determining host susceptibility to Leishmania spp. We previously demonstrated that macrophage-derived IL-10 could contribute to disease exacerbation, but the mechanisms whereby Leishmania infections led to IL-10 induction were not fully understood. In this study, we demonstrated that infection of macrophages with Leishmania amazonensis amastigotes led to the activation of the MAPK, ERK1/2. This activation was required, but not sufficient for IL-10 induction. In addition to ERK activation, an inflammatory stimulus, such as low m.w. hyaluronic acid from the extracellular matrix, must also be present. The combination of these two signals resulted in the superinduction of IL-10. We also demonstrated that IgG on the surface of Leishmania amastigotes was required to achieve maximal IL-10 production from infected macrophages. Surface IgG engages macrophage FcγR to induce ERK activation. Macrophages lacking FcγR, or macrophages treated with an inhibitor of spleen tyrosine kinase, the tyrosine kinase that signals via FcγR, failed to activate ERK and consequently failed to produce IL-10 following infection with Leishmania amastigotes. We confirmed that ERK1/2 activation led to the phosphorylation of histone H3 at the IL-10 promoter, and this phosphorylation allowed for the binding of the transcription factor, Sp1, to the IL-10 promoter. Finally, the administration of U0126, an inhibitor of ERK activation, to infected mice resulted in decreased lesion progression with reduced numbers of parasites in them. Thus, our findings reveal an important role of MAPK, ERK signaling in the pathogenesis of Leishmania infection.

Leishmania species are obligate intracellular parasites that can cause a range of human diseases, spanning self-healing cutaneous lesions to a fatal visceral form of the disease. It has been estimated that there are 1.5 million new cases of cutaneous and 500,000 of visceral leishmaniasis per year (1). The parasites have a unique life cycle. Flagellated metacyclic promastigotes are transmitted into a mammalian host from an infected sandfly. Promastigotes are taken up by professional phagocytic cells, where they replicate as amastigotes within host cell phagolysosome (2). The amastigote forms are released from heavily infected macrophages and spread to adjacent phagocytic cells. The present work focuses on the reinfection of macrophages by released amastigotes.

Leishmania species are master manipulators of host innate and acquired immune mechanisms (3). Leishmania can modulate host cell signaling pathways, making infected cells refractory to activation signals (3, 4). They can also induce host immune cells to produce cytokines that promote disease progression. One of these permissive cytokines is IL-10. IL-10 is a class II α-helical cytokine, and the founding member of a growing family of structurally related cytokines. IL-10 is one of only a few cytokines that has been well documented to have potent immune inhibitory capacity. IL-10 can inhibit the transcription and translation of a variety of inflammatory cytokines and block their actions (5). IL-10 reduces Ag presentation and either inhibits or biases T cell activation (6, 7).

Several groups, including our own, have examined a role for IL-10 during leishmaniasis (8–15). In humans, IL-10 levels were shown to directly correlate with disease severity (16). In murine models of cutaneous (8, 10) and visceral (17) leishmaniasis, IL-10 contributes to disease progression. Lesions in IL-10 knockout mice are substantially smaller than in wild-type mice (10, 12), and the administration of exogenous IL-10 (18) or the induction of endogenous IL-10 (19) results in exacerbated disease.

The transcriptional regulation of IL-10 remains somewhat elusive, despite the identification of several transcription factors and the promoter elements to which they bind. Sp1 has been shown to play an important role in IL-10 transcription (20). The STAT 3 transcription factor has also been shown to bind to an element in the human IL-10 promoter, and a dominant-negative form of STAT 3 has been shown to diminish IL-10 transcription (21). A role for C/EBP has been suggested (22), although it may not be required for IL-10 transcription. The protooncogene, c-MAF, has also been shown to play a critical role in driving IL-10 transcription (23). The regulation of IL-10 in macrophages appears to be somewhat more complex than merely activating transcription factors, however, and a unique transient form of chromatin remodeling appears to be involved (24). Maximal IL-10 gene expression occurs only after the phosphorylation of histones associated with specific sites in the IL-10 promoter (24). The modifications in the IL-10 locus appear to be spatiotemporally distinct from those previously described in T cells (25, 26). In macrophages, chromatin phosphorylation at the IL-10 promoter and subsequent transcription factor binding to this promoter depend on the activation of ERK. In the present work, we show that ERK is activated by lesion-derived amastigotes that are coated with host IgG.

IgG Abs to Leishmania are prominent in human visceral leishmaniasis, and they are also produced in BALB/c mice during Leishmania infection (27–32). The levels of IgG increase as disease progresses and parasites disseminate. We previously examined the role of host Igs in Leishmania major infections in BALB/c mice and found that instead of providing protection, anti-Leishmania IgG actually made the disease worse (19). We attributed this increase in disease severity to an increase in IL-10 production. We further hypothesized that IgG-opsonized Leishmania interacted with FcγRs on the surface of macrophages to trigger signaling events leading to the induction of IL-10 gene expression (19).

Our previous observations about the role of ERK activation in response to soluble immune complexes (24), combined with our recent observations that Ab could exacerbate leishmanial disease, led us to investigate whether the activation of ERK during Leishmania infection could contribute to disease progression. In the present studies, we examined ERK activation following infection of macrophages with Leishmania amazonensis (LA) amastigotes. We identified a link between the epigenetic modifications at the il-10 locus, IL-10 gene expression, and disease progression. We demonstrate a critical role for ERK activation in the induction of IL-10 production by Leishmania, and show that parasite immune complexes bind to macrophage FcγR and induce this activation via the macrophage FcγR. The implications for these studies are that IgG can be detrimental to the host due to its ability to activate ERK.

Materials and Methods

Mice and bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMMϕ)3

BALB/c, JH, and FcγR knockout mice on the BALB/c background were purchased from Taconic Farms. All mice were maintained in high efficiency particle air-filtered Thoren units (Thoren Caging Systems) at the University of Maryland. All animal studies were reviewed and approved by the University of Maryland Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. BMMϕ were prepared, as previously described. Briefly, bone marrow was flushed from the femurs and tibias of mice at 6−10 wk of age. The cells were plated in petri dishes in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% FBS, glutamine, penicillin/streptomycin, and 10% L cell conditioned medium. Cells were fed on days 2 and 5. On day 7, cells were removed from petri dishes and cultured on tissue culture dishes in complete medium without L cell conditioned medium. On the next day, cells were subjected to experiments.

Reagents

The MEK/ERK inhibitors, U0126 and PD98059, and the spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) inhibitor (3-(1-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl-methylene)-2-oxo-2,3-dihydro-1H-indole-5-sulfonamide) were purchased from Calbiochem (EMD Biosciences). Low m.w. hyaluronic acid (LMW-HA) was purchased from MP Biomedicals. Anti-ERK1/2 (total and phospho-T202/Y204) Abs were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology. Anti-phosphorylated his-tone H3 (Ser10) Ab, anti-Sp1 Ab, and chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) kits were purchased from Upstate Biotechnology. TRIzol reagent was purchased from Invitrogen Life Technologies. RNase-free DNase I was obtained from Roche Diagnostics.

Parasites

LA (RAT/BA/72/LV78) were used throughout. IgG-free amastigotes of LA were developed by axenic culturing of parasites, as previously described (10). Amastigotes were isolated from footpads of BALB/c mice that were infected for 6−8 wk, as previously described (10, 19). Briefly, the plunger of a 10-ml syringe was used to pass the excised foot through a cell strainer of 100 μm nylon (BD Biosciences) in the presence of Schneider's complete medium. The release of amastigotes from infected cells was achieved by passing the mixture through progressively smaller, 21-, 23-, and 25-gauge needles. Footpad-derived (Fp.) amastigotes were obtained by centrifugation at 1000 × g for 10 min. Stationary-phase promastigotes were obtained by growing parasites in Schneider's complete medium with 20% FBS at 25°C. Axenic amastigotes were cultured in Schneider's complete medium with 5% FBS (pH 5.6) at 32°C, as described (33).

Cytokine measurement

Approximately 2−5 × 105 BMMϕ were plated per well overnight in a 48-well plate in DMEM/F12 medium with 10% FBS. Cells were then washed and activated with either 10 μg/ml LMW-HA alone or in combination with 10:1 ratio to macrophages of LA lesion-derived (IgG-positive) amastigotes or axenic amastigotes (IgG-negative). Supernatants were harvested at different time intervals. Cytokines were measured by a sandwich ELISA using Ab pairs provided by BD Pharmingen (IL-12p40, C15.6 and C17.8; IL-10, JES-2A5 and JES-16E3), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Western blotting

A total of 2 × 106 BMMϕ per well were plated overnight in six-well plates. Cells were treated with 10 μg/ml LMW-HA alone or in combination with parasites in a final volume of 1 ml of DMEM/F12 without L929 conditioned medium. Cells were then lysed in ice-cold lysis buffer (100 mM Tris (pH 8), 2 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100 containing complete EDTA-free protease inhibitors from Roche Diagnostics, which included 5 mM sodium vanadate, 10 mM sodium fluoride, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate sodium, and 5 mM sodium pyrophosphate). Equal amounts of protein were loaded onto 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels, and then transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Membranes were incubated with primary Abs overnight at 4°C, washed, and incubated with secondary Ab with HRP conjugates. The specific protein bands were visualized by using Lumi-LightPLUS chemiluminescent substrate (Roche Diagnostics).

Immunofluorescence microscopic analysis

Amastigotes were stained with 5 μM CellTracker Blue CMAC (Invitrogen Life Technologies). BMMϕ were infected with amastigotes in the presence or absence of hyaluronic acid (HA) for a period of time. After brief washing with PBS, cells were fixed in methanol at 4°C for 15 min and then washed with PBS. Monolayers were incubated with 10% FBS in PBS for 1 h at room temperature to prevent nonspecific binding. ERK1/2 phosphor-ylation was stained by a phospho-p44/42 MAPK (T202/Y204) (E10) mouse mAb (Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate) (Cell Signaling Technology). Macrophages were counterstained for 2 min with 0.5% propidium iodide (PI). Slides were examined by using a Zeiss Axioplan 2 fluorescent imaging research microscope and Zeiss KS300 imaging software.

RNA isolation and RT-PCR

TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies) was used to extract RNA from BMMϕ (3 × 106 cells per reaction). Homogenization was conducted to facilitate RNA extraction from footpad and lymph node. RNase-free DNase I (Roche Diagnostics) was used to remove contaminated DNA. ThermoScript RT-PCR system (Invitrogen Life Technologies) was used to generate cDNA from RNA by using random hexamers or oligo(dT)20. Quantitative real-time PCR (Qrt-PCR) was used to measure both mature and premature IL-10 mRNA levels. Premature IL-10 mRNA was analyzed by using random hexamer-generated cDNA and the primer pairs: sense 5′-CATTCCAGTAAGTCACACCCA-3′ (intronic primer) and antisense 5′-TCTCACCCAGGGAATTCAAA-3′, and GAPDH primer pairs: sense 5′-TGTTCCTACCCCCAATGTGT-3′ and antisense 5′-TCCCAAGTCACTGTCACACC-3′ (intronic primer). Mature IL-10 mRNA was amplified by using oligo(dT)20-generated cDNA and the primer pairs: sense 5′-AAGGACCAGCTGGACAACAT-3′ and antisense 5′-TCTCACCCAGGGAATTCAAA-3′, GAPDH primer pairs: sense 5′-TGTTCCTACCCCCAATGTGT-3′ and antisense 5′-GGTCCTCAGTGTAGCCCAAG-3′, and hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase primer pairs: sense 5′-AAGCTTGCTGGTGAAAAGGA-3′ and antisense 5′-TTGCGCTCATCTTAGGCTTT-3′.

ChIP assay

ChIP assays were performed following ultrasonic shearing conditions that resulted in relatively uniform DNA fragment size of ∼300 bp. The remaining procedures were conducted, as previously described (24). The primer pairs used to amplify nucleosomes 2 and 11 of the IL-10 promoter were as follows: 5′-GCAGAAGTTCATTCCGACCA-3′ (sense) and 5′-GGCTCCTCCTCCCTCTTCTA-3′ (antisense) for nucleosome 2, and 5′-GTTGCTTCGCTGTTGGAAA-3′ (sense) and 5′-GGTCAGTTCCAGGCTGAGTT-3′ (antisense) for nucleosome 11.

Infection and parasite quantitation

Mice were inoculated in the right hind footpad with different numbers of amastigotes, as indicated in the figure legends. Lesion size was measured with a digital thickness gauge (Chicago Brand Industrial) and expressed as the difference in thickness between the infected and the contralateral (non-infected) footpad, as described previously (19). Parasite burdens were determined by a limiting dilution of cell suspensions obtained from excised lesions, as described previously (19). Briefly, the cell suspensions were serially diluted in Schneider's complete medium and observed 7 days later for the growth of promastigotes. Parasite burdens were expressed as the negative log10 dilution of which parasite growth was visible. A Qrt-PCR method to amplify parasite DNA complemented parasite burdens. In brief, the homogenates of infected lesion were treated with proteinase K. The DNA was obtained after phenol/chloroform extraction and NaOAC/EtOH precipitation. Primers specific for LA 18S rRNA gene are: 5′-AGCAGGTCTGTGATGCTCCT-3′ (sense) and 5′-GGACGTAATCGGCACAGTTT-3′ (antisense). PCR amplication of murine 18S rRNA gene was used as reference marker for normalization. The relevant primers are: 5′-CCCAGTAAGTGCGGGTCATA-3′ (sense) and 5′-AGTTCGACCGTCTTCTCAGC-3′ (antisense). The parasite burden was expressed as fold changes by using the ΔΔCT (cycle threshold) methods, as described below.

Qrt-PCR

Qrt-PCR was performed on an ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detection System using SYBR Green PCR reagents purchased from Bio-Rad. Electrophoresis of final PCR products was performed after PCR amplification to ensure that a single product was obtained.

Data analysis

The relative differences among Qrt-PCR samples were determined using the ΔΔCT methods, as described in the Applied Biosystems protocol. A ΔCT value was determined for each sample using the CT value from input DNA to normalize ChIP assay results. The CT value for GAPDH gene was used to normalize loading in the RT-PCRs. For quantitation of parasite burden in the infected lesion, the CT value for murine 18S rRNA gene was used as normalization reference gene. A ΔΔCT value was then obtained by subtracting control ΔCT values from the corresponding experimental ΔCT. The ΔΔCT values were converted to fold difference compared with the control by raising 2 to the ΔΔCT power. Unpaired Student's t test was used for statistical analysis. Values of p < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

ERK activation in macrophages infected with lesion-derived LA amastigotes

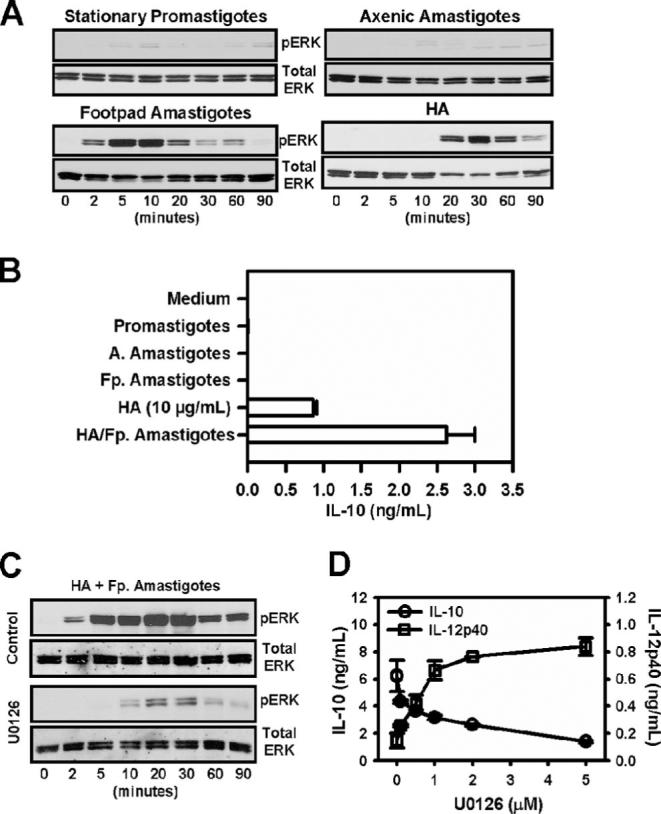

We examined ERK activation in macrophages infected with LA. Macrophages that were infected with either stationary-phase promastigotes or axenic amastigotes exhibited no sign of ERK activation, as measured by Western blot analysis using an Ab specific for phosphorylated forms of ERK 1 and 2 (Fig. 1A). In contrast to these developmental forms, lesion-derived footpad amastigotes were potent inducers of ERK activation (Fig. 1A). Footpad amastigotes induced ERK activation in a time-dependent fashion, such that activation reached maximal levels between 5 and 10 min postinfection and began to decline after 20 min. As a positive control for these studies, macrophages were cultivated with inflammatory LMW-HA (34–36). HA is a major component of the extracellular matrix. HA can be degraded to yield fragments with smaller m.w., which can occur at sites of inflammation (34, 36), such as leishmanial lesions. LMW-HA induced ERK activation in macrophages (Fig. 1A); however, this induction was somewhat slower than amastigotes. ERK phosphorylation was not detectable until 20 min, and it persisted for 60−90 min. These data indicate that lesion-derived amastigotes are rapid, but transient inducers of ERK activation.

FIGURE 1.

ERK activation by LA amastigotes. A, Stationary-phase promastigotes, axenic cultured amastigotes, and Fp. amastigotes were obtained, as described in Materials and Methods. They were added to monolayers of BMMϕ (2 × 106 cells/well), along with HA (10 μg/ml). The ratio of parasites to macrophages was 20:1. At designated times, equal amounts of whole cell lysates (15 μg) were subject to electrophoresis on 10% SDS-PAGE. Phosphorylated forms of ERK and the corresponding total proteins were detected by Western blotting. B, Macrophages were treated with HA (10 μg/ml), or infected with stationary promastigotes (Promastigotes), axenic amastigotes (A. Amastigotes), Fp. amastigotes (Fp. Amastigotes), or Fp. amastigotes and HA. Supernatants were collected after 16 h, and IL-10 and IL-12p40 were quantitated by ELISA. Data represent one of three independent experiments (mean ± SD of triplicates). C, Macrophages were pretreated with drug vehicle (control) or U0126 (2 μM) for 1 h. Cells (2 × 106 cells) were then stimulated with HA plus lesion-derived amastigotes for the indicated times. Electrophoresis and Western blotting were performed, as described above. D, Macrophages were pretreated with increasing concentrations of U0126 as indicated for 1 h and then infected with lesion-derived amastigotes in the presence of HA (10 μg/ml) for 8 h. Supernatants were harvested, and IL-10 and IL-12p40 production were determined by ELISA. Data represent one of three independent experiments (mean ± SD of triplicates).

We next wanted to correlate ERK activation with IL-10 production by macrophages. Infection of macrophages with either promastigotes or axenic amastigotes failed to induce IL-10 production (Fig. 1B). This observation is consistent with their failure to activate ERK (Fig. 1A). Although Fp. amastigotes were potent inducers of ERK (Fig. 1A), they also failed to induce IL-10 production (Fig. 1B). Similarly, although LMW-HA was a potent, albeit delayed, inducer of ERK (Fig. 1A), it induced only modest levels of IL-10 (Fig. 1B). Only the combination of lesion-derived amastigotes (Fp. amastigotes) and LMW-HA resulted in optimal IL-10 production (Fig. 1B).

We therefore examined ERK activation in macrophages exposed to both LA amastigotes and LMW-HA (Fig. 1C). ERK activation under these conditions could be detected as early as 2 min posttreatment, and reached maximal levels between 20 and 30 min. It persisted for 90 min. Thus, the combination of LMW-HA plus Fp. amastigotes resulted in a rapid and prolonged activation of ERK. This activation correlates with maximal IL-10 production (Fig. 1D).

To determine the link between ERK activation and IL-10 production, macrophages were treated with increasing concentrations of U0126, and IL-10 production was measured in response to infection with lesion-derived amastigotes plus LMW-HA. The phosphorylation of ERK1/2 was strongly inhibited by adding the MEK inhibitor U0126 (Fig. 1C). There was also a dose-dependent inhibition of IL-10 production by U0126 (Fig. 1D). As a control, IL-12 (p40) levels were also measured. There was a reciprocal increase of IL-12 that correlated with ERK inhibition. These data suggest that ERK was required for IL-10 production by infected macrophages, and that the inhibition of ERK activation prevented IL-10 production. However, ERK activation was not sufficient for IL-10 production because lesion-derived amastigotes activated ERK (Fig. 1A), but failed to induce IL-10, unless an inflammatory stimulus such as LMW-HA was also added.

The role of IgG in ERK activation by Leishmania

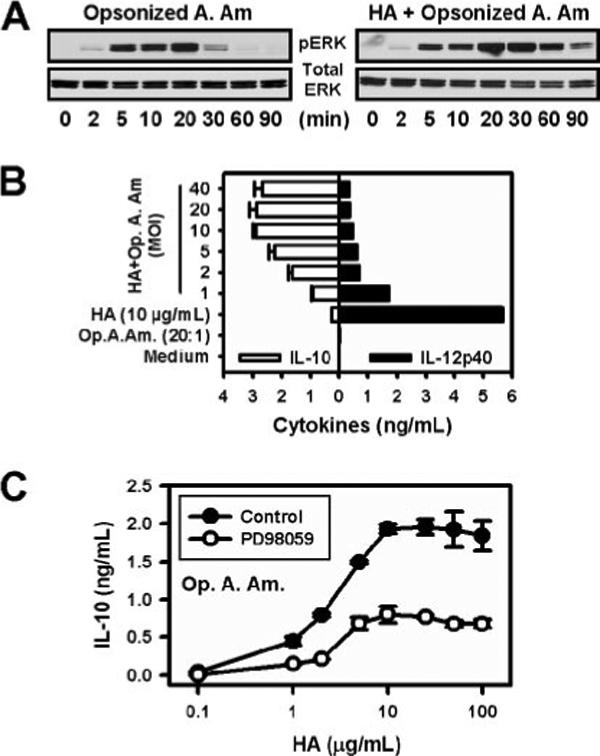

Axenically grown amastigotes do not activate ERK (Fig. 1A), and they fail to induce IL-10 production (2, 10). To determine the relationship between surface IgG and ERK activation, axenically grown amastigotes, which have no IgG on their surface (2, 10), were opsonized with Ab against LA and added to macrophages. ERK activation in the absence or presence of LMW-HA was analyzed (Fig. 2A). Opsonized axenic amastigotes induced ERK activation to a similar degree and with similar kinetics as footpad amastigotes. ERK activation was detectable as early as 2 min, and peaked at 20 min. Similar to lesion-derived amastigotes, the presence of LMW-HA increased the speed, magnitude, and duration of ERK activation (Fig. 2A).

FIGURE 2.

Opsonized axenic cultured amastigotes activate ERK and induce IL-10 production. A, Macrophages (2 × 106 cells) were infected with LA axenic amastigotes opsonized with anti-Leishmania serum (Opsonized A. Am.) in the presence or absence of HA (10 μg/ml). Western blotting of phosphorylated ERK1/2 was examined at the indicated times. Total ERK1/2 was used as the loading control. The ratio of parasites to macrophages was 20:1. B, Macrophages were infected with increasing concentrations (MOI from 1:1 to 40:1) of axenic cultured amastigotes opsonized with IgG (Op. A. Am.) in the presence of HA (10 μg/ml). The supernatants were collected after 16 h, and IL-10 and IL-12p40 proteins were determined by ELISA. For controls, macrophages were treated with medium alone, opsonized axenic amastigotes (Op. A. Am.), or HA alone. Data represent one of three independent experiments (mean ± SD of trip-licates). C, Macrophages (2 × 105 cells) were exposed to a 20:1 ratio of opsonized axenic cultured amastigotes (Op. A. Am.) in the presence of increasing concentrations of HA. Parallel monolayers were treated similarly, except that the MEK inhibitor, PD98059 (10 μM), was added 30 min before stimulation. The supernatants were collected 8 h later, and IL-10 concentrations were determined by ELISA. Data represent one of three independent experiments (mean ± SD of triplicates).

IL-10 was measured by macrophages infected with opsonized axenic amastigotes. Similar to lesion-derived footpad amastigotes, opsonized axenic amastigotes only induced IL-10 production when macrophages were infected in the presence of LMW-HA. Under these conditions, IL-10 production was induced in a parasite dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2B, □). Maximal IL-10 production occurred with a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of between 10:1 and 20:1. This corresponds to the ratio of parasites that maximally activate ERK (data not shown). As a control for these studies, IL-12 (p40) production was also measured. LMW-HA was a potent inducer of IL-12, as previously reported (34). The addition of opsonized axenic amastigotes reduced IL-12 production in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2B, ■).

IL-10 production from infected macrophages was also measured in the presence or absence of another MEK inhibitor, PD98059. Amastigotes induced IL-10 from macrophages in a LMW-HA dose-dependent manner, and this production was inhibited by the addition of PD98059 (Fig. 2C). These data are consistent with Ab opsonization of Leishmania amastigotes being responsible for ERK activation, and with ERK activation being required for IL-10 production.

Immunofluorescence microscopic analysis of ERK activation

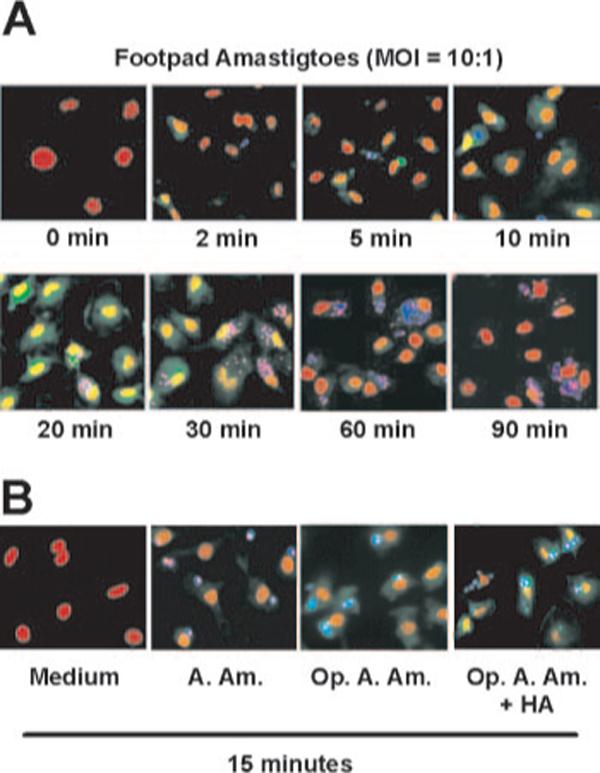

To monitor intracellular changes in ERK phosphorylation, macrophages were plated on coverslips and infected with lesion-derived amastigotes (10:1 ratio) in the presence of LMW-HA (10 μg/ml). Amastigotes were prestained with CellTracker Blue, and monolayers were examined by epifluorescence microscopy. ERK phosphorylation was detected by a fluorescent-labeled Ab against phosphorylated ERK 1/2 (green), and nuclei were stained with PI (red). ERK phosphorylation of infected macrophages could be detected as early as 2 min after infection (Fig. 3A). By 20−30 min postinfection, ERK activation reached maximal levels. Phosphorylated ERK was mainly localized in the perinuclear/nuclear regions of the cell, which is consistent with previous observations (37). A similar degree of ERK activation occurred with opsonized axenic amastigotes. Unopsonized axenic amastigotes, however, failed to activate ERK (Fig. 3B).

FIGURE 3.

Immunofluorescence analysis of ERK activation in macrophages. A, Macrophage monolayers (1 × 105 cells/coverslip) were infected with lesion-derived footpad amastigotes in the presence of HA (10 μg/ml) at MOI of 10:1 for the indicated times. Cells were fixed with cold-methanol, and visualized by fluorescence microscopy. Parasites were prestained with Cell Tracker Blue (blue). Phosphorylated ERK was stained with mouse mAb (Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate) against phosphor-ERK (green), and cell nuclei were stained with PI (red). B, Macrophages (1 × 105 cells) were treated with HA (10 μg/ml), and infected with unopsonized (A. Am.) or IgG-opsonized axenic cultured amastigotes (Op. A. Am.), in the presence or absence of HA for 15 min.

ERK activation and IL-10 production by opsonized parasites are mediated by the FcγR signaling pathway

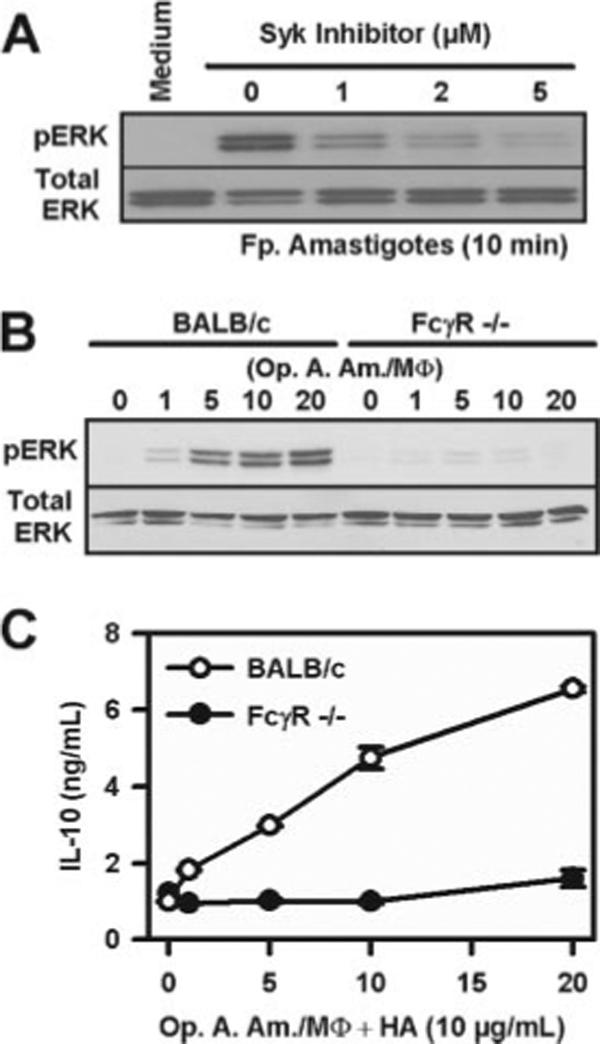

To show a role for the FcγR in ERK activation, we used a pharmacological inhibitor and macrophages from FcγR knockout mice. Syk is a tyrosine kinase that has been implicated in FcγR-mediated signaling (38). A Syk inhibitor, 3-(1-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl-methylene)-2-oxo-2,3-dihydro-1H-indole-5-sulfonamide, was added to macrophages before their infection with lesion-derived amastigotes. The inhibition of FcγR signaling by the addition of the Syk inhibitor reduced ERK activation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4A). At 1 μM inhibitor concentration, ERK activation was substantially diminished. At this dose of inhibitor, IL-10 production was reduced by >80% (data not shown).

FIGURE 4.

FcγR-mediated signaling is critical for ERK activation. A, Macrophages (2 × 106 cells) were pretreated with different doses of Syk inhibitor for 1 h and then stimulated with lesion-derived amastigotes (MOI = 20:1) for 10 min. Whole cell lysates were collected and analyzed by Western blotting to detect ERK phosphorylation. B, Macrophages derived either from BALB/c or FcγR−/− mice were treated with different MOIs of opsonized axenic cultured amastigotes (Op. A. Am), as indicated. After 10-min incubation, cell lysates were collected and analyzed by Western blotting. C, Macrophages derived either from BALB/c or FcγR−/− mice were infected with increasing amounts (MOI) of opsonized axenic cultured amastigotes together with HA (10 μg/ml). After 8 h, the supernatants were collected for ELISA to determine IL-10 production. Data represent one of two independent experiments (mean ± SD of triplicates).

Our second approach was to examine ERK activation in macrophages lacking the common γ-chain through which FcγRI, III, and IV signal. ERK activation was essentially undetectable in these microphages following infection with lesion-derived amastigotes (Fig. 4B). These macrophages produced substantially less IL-10 when infected with lesion-derived amastigotes, relative to those from wild-type BALB/c mice (Fig. 4C). Taken together, these data indicate that LA-induced ERK activation was mediated through an FcγR-mediated signaling pathway.

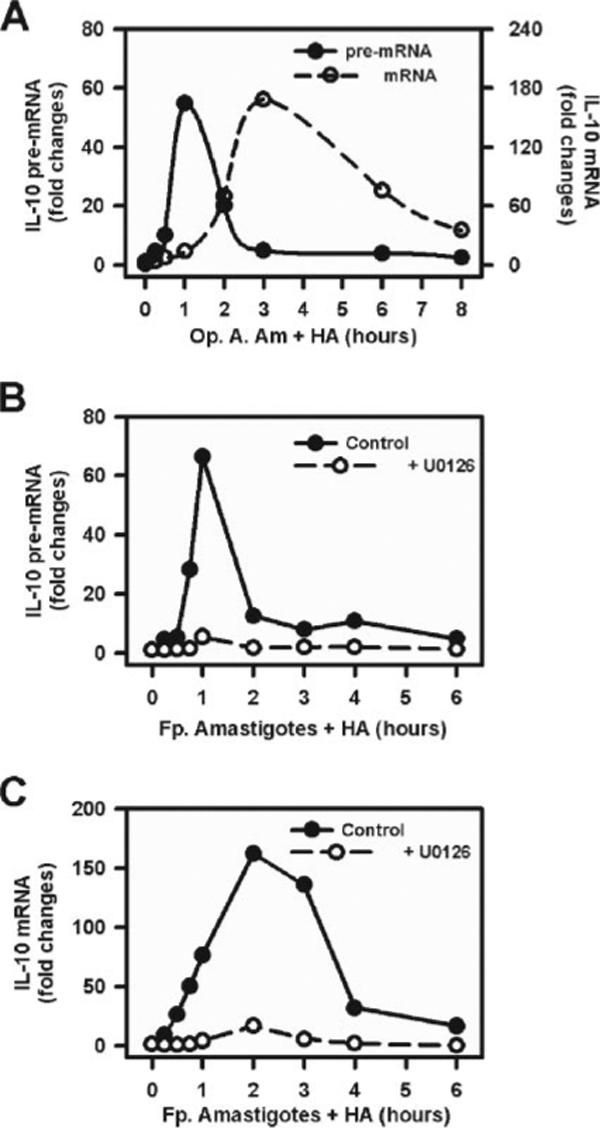

Induction of IL-10 gene expression by opsonized parasites in the presence of HA

To gain further insight into the molecular mechanisms of IL-10 gene expression, we investigated changes in IL-10 transcription. Nuclear pre-mRNA and cytoplasmic mature mRNA were isolated following infection of macrophages with LA amastigotes plus HA. Gene transcription was monitored by measuring pre-mRNA formation, using Qrt-PCR to amplify unspliced message, as previously described (39). The accumulation of cytoplasmic mature spliced IL-10 mRNA was also examined. In the presence of HA (10 μg/ml), opsonized axenic amastigotes (20:1) induced IL-10 transcription (Fig. 5A). Pre-mRNA transcripts were detected as early as 15 min postinfection, and quickly reached maximal levels at ∼60 min. They rapidly returned to basal levels by 180 min (Fig. 5A). IL-12p40 gene expression was barely detected at these time points under these conditions (data not shown). Mature mRNA for IL-10 was detectable within1hof infection, and peaked at 3 h (Fig. 5A). Axenic amastigotes without Ab opsonization failed to induce IL-10 transcripts or mature mRNA (data not shown).

FIGURE 5.

Parasites induce IL-10 gene expression via ERK activation. A, Macrophages (4 × 106 cells) were treated with opsonized axenic cultured amastigotes (Op. A. Am.) (MOI = 20:1) in the presence of HA (10 μg/ml). Cytoplasmic and nuclear RNA were isolated at different time intervals, as indicated. Real-time PCR was performed to detect the presence of IL-10 pre-mRNA (solid line, left axis) and IL-10 mRNA (dash line, right axis). B and C, Macrophages were pretreated with U0126 (2 μM) (○)or drug vehicle (●) for 1 h and then infected with lesion-derived amastigotes (Fp. Amastigotes) (at an MOI of 20:1) plus HA (10 μg/ml) for indicated times. Cytoplasmic and nuclear RNA were isolated, and the real-time PCR was performed to analyze the presence of IL-10 pre-mRNA (B) and mature IL-10 mRNA (C). Data represent one of two independent experiments.

Similar studies were performed with Fp. amastigotes. Macrophages were pretreated with the ERK inhibitor, U0126, and then infected with Fp. amastigotes in the presence of HA. Similar to the effects observed with opsonized axenic amastigotes, the inhibition of ERK activation by U0126 prevented IL-10 transcription from infected macrophages (Fig. 5B). A similar observation was made at the level of mature mRNA, which failed to accumulate in the presence of U0126 (Fig. 5C). These data demonstrate the requirement for ERK activation for IL-10 transcription initiated in response to infection by Leishmania amastigotes.

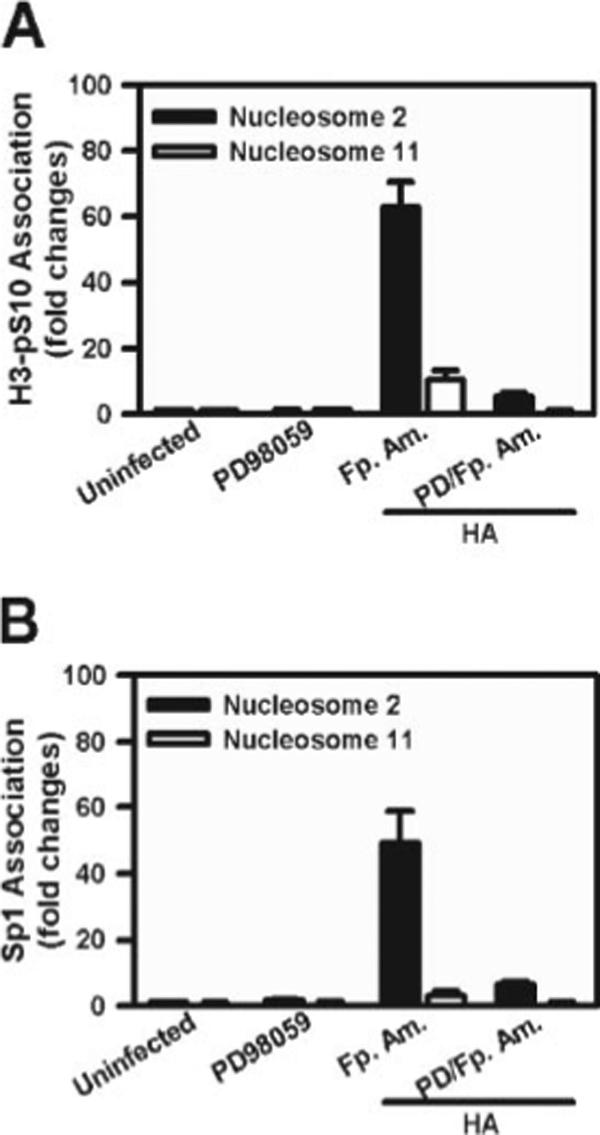

ERK activation results in histone phosphorylation at the IL-10 promoter

To further explore the molecular mechanisms of IL-10 gene transcription, we investigated epigenetic modifications associated with the IL-10 gene following infection. We examined histone H3 phosphorylation at Ser10 (H3S10) at the IL-10 promoter. Our previous observations (24) indicated that ERK activation by soluble immune complexes could result in histone phosphorylation. We used ChIP to examine histone phosphorylation at the IL-10 promoter following macrophage infection with LA. The second nucleosome from the transcriptional start site contains the binding site for the transcription factor Sp1 (24). Within 45 min of infection with Fp. amastigotes, histone H3 was phosphorylated at Ser10 on the second nucleosome (Fig. 6A, ■). This phosphorylation was relatively specific to this site, because there was essentially no phosphorylation of the histones associated with nucleosome 11 located only 1000 bp from the Sp1 site (Fig. 6A, □). Coincident with histone phosphorylation, there was a rapid binding of Sp1 to the IL-10 promoter at nucleosome 2, but not nucleosome 11 (Fig. 6B). Both histone phosphorylation (Fig. 6A) and Sp1 binding (Fig. 6B) were completely prevented by inhibiting ERK activation.

FIGURE 6.

IL-10 gene expression requires ERK-mediated histone H3 Ser10 phosphorylation and the recruitment of Sp1. Macrophages (4 × 106 cells) were pretreated with or without PD098059 (10 μM) (PD) for 1 hand then infected with or without Fp. amastigotes (Fp. Am.) plus HA (10 μg/ml) for 45 min. The chromatin fragments were immunoprecipitated using a specific Ab against phosphorylated histone H3 at Ser10 (A)oranAbto Sp1 (B). Real-time PCR was performed to determine the presence of DNA associated with nucleosome 2 (■) or nucleosome 11 (□), as described in Materials and Methods. Data represent mean ± SD with triplicates.

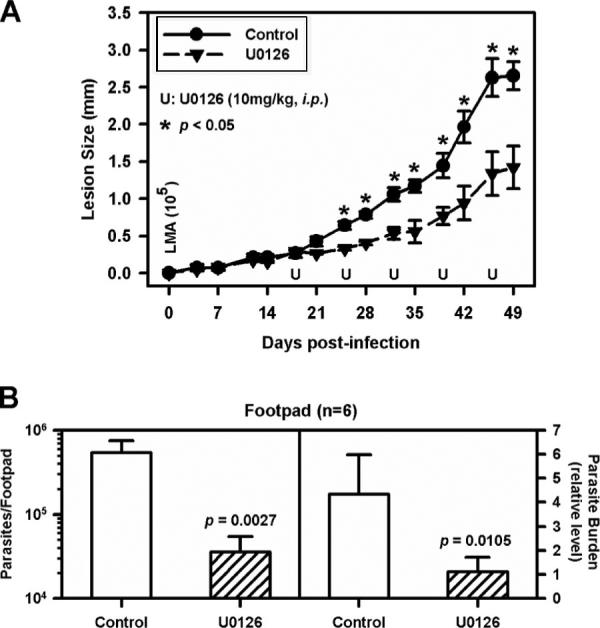

Lesion development in mice treated with ERK inhibitors

We examined whether the inhibition of ERK activation would have any effect on lesion progression followed by LA infection of BALB/c mice. BALB/c mice were infected with 105 lesion-derived amastigotes in the right hind footpad. Lesion progression was monitored twice weekly over a 7-wk period. The ERK inhibitor, U0126 (10 mg/kg), was administrated i.p. once per week beginning at the 18th day after infection for 5 wk. We selected U0126 over PD98059 for these in vivo studies because it has higher potency and solubility. Control BALB/c mice developed measurable lesions within 3 wk of infection, and these lesions became progressively larger until the experiment was terminated on day 49 (Fig. 7A). Lesions in mice treated with U0126 were smaller within 1 wk of administration of the inhibitor, and they remained significantly smaller throughout the observation period (p < 0.05) (Fig. 7A). Parasite burdens in the infected feet were measured by two methods, limiting dilution and Qrt-PCR to amplify parasite DNA (Fig. 7B). By both criteria, mice that received the inhibitor had significantly lower parasite burdens relative to untreated mice at day 49 (Fig. 7B).

FIGURE 7.

Inhibition of ERK activation delays the progression of lesions in mice infected with LA in vivo. BALB/c mice (female) control group (n = 6) (●) and U0126-treated group (n = 6) (▲) were injected with 1 × 105 lesion-derived amastigotes of LA in the hind footpad. After 18 days, weekly injections of U0126 (10 mg/kg) were administered i.p. for 5 wk. The control group received the same volume of drug vehicle. A, Lesion size was measured on the indicated days. B, Parasite burdens in infected footpad were determined by limiting dilution assay (left) and real-time PCR (right), as described in Materials and Methods. One representative experiment of three is shown. Data represent mean ± SD. The p values were determined by Student's t test. *, p < 0.05.

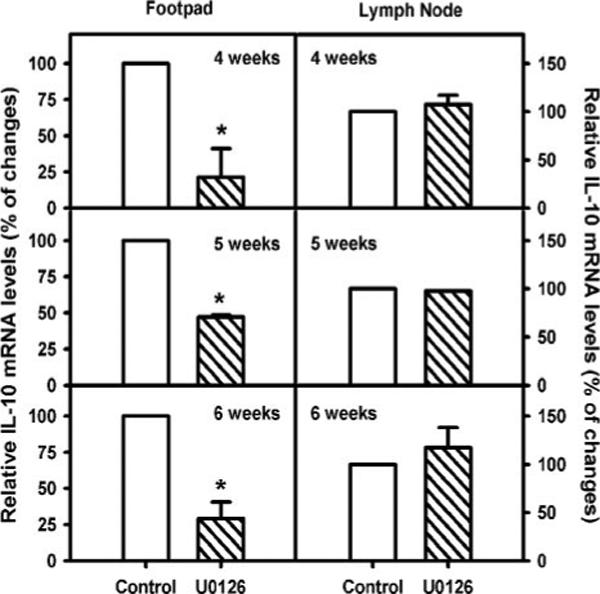

To relate the differences in lesion size to IL-10 levels, mice were infected on day 1 with LA and administered U0126 i.p. at weekly intervals thereafter. At weeks 4, 5, and 6, mice were euthanized, and IL-10 mRNA levels in the lesions were analyzed by Qrt-PCR. The levels of IL-10 mRNA in the feet of infected mice treated with U0126 were substantially reduced relative to untreated mice (Fig. 8). Interestingly, there was no difference in IL-10 levels in lymph nodes (Fig. 8), suggesting that IL-10 production in the lesion itself was responsible for lesion progression.

FIGURE 8.

ERK inhibition by U0126 reduces IL-10 gene expression in lesions. BALB/c mice (female) were infected with 1 × 105 lesion-derived amastigotes in the right hind footpad. Weekly injection of U0126 (10 mg/kg) was administrated to one group i.p. for 6 wk ( ; n = 3). Total RNA was isolated on the day after U0126 administration for 3 wk, as indicated in the figures. IL-10 mRNA levels were determined by Qrt-PCR, as described in Materials and Methods. After normalization by hypoxanthineguanine phosphoribosyltransferase mRNA levels, IL-10 mRNA levels of infected mice without U0126 treatment (□; n = 3) were arbitrarily set as 100%. Relative IL-10 mRNA expression in the footpad (left) and the lymph node (right) was determined. Data represent mean ± SD with triplicates. The p values were determined by Student's t test. *, p < 0.05.

; n = 3). Total RNA was isolated on the day after U0126 administration for 3 wk, as indicated in the figures. IL-10 mRNA levels were determined by Qrt-PCR, as described in Materials and Methods. After normalization by hypoxanthineguanine phosphoribosyltransferase mRNA levels, IL-10 mRNA levels of infected mice without U0126 treatment (□; n = 3) were arbitrarily set as 100%. Relative IL-10 mRNA expression in the footpad (left) and the lymph node (right) was determined. Data represent mean ± SD with triplicates. The p values were determined by Student's t test. *, p < 0.05.

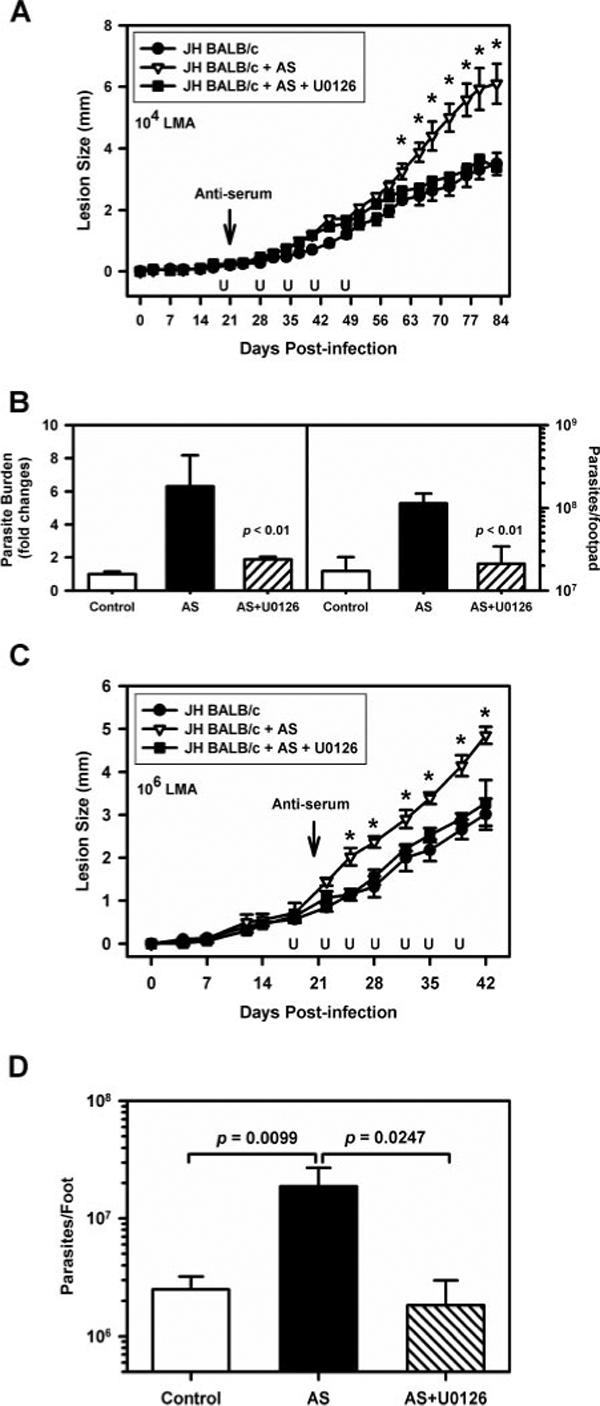

Previous studies in our laboratory (19) demonstrated that the administration of parasite-specific antiserum to JH mice exacerbated L. major infection. We infected JH mice with 1 × 104 lesion-derived LA amastigotes in the hind footpad and examined lesion development. Beginning at the 20th day after infection, we administrated one group of mice U0126 (10 mg/kg) i.p. every 7 days until 48 days postinfection. At the 21st day, the two groups of mice were injected i.p. with 200 μl of anti-LA serum. Lesions in JH mice became slightly larger after mice were injected with anti-parasite serum (Fig. 9A, △). The administration of U0126 reduced the Ab-induced increase in lesion swelling (Fig. 9A, ■). These lesions were not significantly different from those in mice that received no Ab (Fig. 9A, ●). Parasite burdens in the infected footpads were measured by serial dilution and Qrt-PCR. Mice administered Ab to LA had significantly more parasites than untreated mice (p ≤ 0.01). The coadministration of U0126, however, returned burdens back to untreated levels (Fig. 9B). Similar studies were performed using 100-fold more parasites (1 × 106), with the similar result (Fig. 9, C and D). Mice receiving U0126 had smaller lesions with fewer parasites. These in vivo observations are consistent with our in vitro data showing that ERK activation can influence macrophage responses to Leishmania infection.

FIGURE 9.

The inhibition of ERK activation prevents IgG-mediated exacerbation of disease. JH mice on the BALB/c background (female) were infected with 1 × 104 (A and B) or 1 × 106 (C and D) lesion-derived amastigotes in the right hind footpad. Two groups of mice (n = 6) were injected i.p. with 200 μl of anti-LA serum at the 21st day postinfection. One of these groups (■) was administrated with U0126 (10 mg/kg) i.p., as indicated. Another group of mice (●)(n = 6) was treated with drug vehicle as a control. Lesion size was measured on the indicated days following infection with 1 × 104 (A) or 1 × 106 (C) parasites. B, Parasite burdens were determined by limiting dilution assay (right) and real-time PCR (left, and D), as described in Materials and Methods. Data represent mean ± SD. The p values were determined by Student's t test. *, p < 0.05.

Discussion

The interaction of Leishmania parasites with host macrophages can result in altered intracellular signaling pathways, leading to parasite survival within infected macrophages. In this study, we describe the activation of MAPK, ERK following infection of macrophages with LA parasites. Previous studies have correlated ERK activation with leishmaniasis. Lipophosphoglycan from Leishmania has been reported to subvert macrophage IL-12 production by activating ERK (40). It has also been suggested that the strength of CD40 signaling may influence the specific MAPK pathway that is activated, and thereby influence cytokine production from infected cells (41). In the present work, we demonstrate that opsonized amastigotes of Leishmania induce MAPK-ERK activation in macrophages. This activation results in epigenetic modifications of il-10 gene locus, thereby causing a superinduction of IL-10 from infected macrophages.

Importantly, lesion-derived amastigotes alone are not sufficient to induce IL-10 production, despite their ability to rapidly activate ERK. Parasites must be combined with some inflammatory stimulus to induce macrophage IL-10 production. These stimuli can be fragments of hyaluronan, called LMW-HA. Hyaluronan is a major component of extracellular matrix and exists as a high-m.w. polymer under normal physiological conditions. After tissue injury, small fragments of hyaluronan are generated at the site of injury (35, 36). Several recent studies suggest that these hyaluronan fragments can signal through TLR2 and 4 on endothelial cells and dendritic cells (34–36). LMW-HA is not the only inflammatory signal that can coinduce IL-10 production. Often leishmanial lesions are superinfected with bacteria, which can provide the inflammatory stimulus via any TLR, including TLR2 or 4. Alternatively, the lysis of heavily infected macrophages may release heat shock proteins (42) or high mobility group protein 1 (43) from mammalian cells to stimulate IL-10 production.

Our findings also indicate that signaling through the macrophage FcγR is critical for IL-10 induction. Axenically grown amastigotes, which lack IgG (10), failed to activate ERK (Fig. 1A) and failed to induce IL-10 production (Fig. 1B). The opsonization of these organisms with IgG restored their ability to activate ERK and induce IL-10 (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, cells lacking FcγR failed to activate ERK (Fig. 4B), and they failed to produce IL-10 in response to infection (Fig. 4C) (10).

In our model, the delayed activation of ERK by inflammatory mediators, such as LMW-HA, is sufficient to induce only modest levels of IL-10 production from macrophages. However, the addition of IgG-opsonized amastigotes dramatically increased the speed with which ERK was activated, and it also increased the magnitude and the duration of ERK activation. This hyperactivation of ERK resulted in the phosphorylation of histone H3 at Ser10. This modification occurs primarily, if not exclusively, at the IL-10 promoter, and specifically at nucleosomes that are associated with transcription factor binding. The histones associated with Sp1 binding site were highly phosphorylated. The phosphorylation of histones makes this promoter region more accessible to Sp1 (Fig. 6B), resulting in a dramatic superinduction of IL-10 transcription. The result is the secretion of high levels of this inhibitory cytokine by infected macrophages.

A critical component of the proposed model is that the amastigotes in lesions have host IgG on their surface. We (10) and others (44) previously reported this, but we were preceded by almost a decade by the original observation showing this to be the case (45). The IgG on amastigotes appears to be the result of a parasite-specific IgG response by the host. Several studies have demonstrated that high levels of parasite-specific IgG are generated during leishmaniasis (46, 47). This is especially true with human visceral leishmaniasis in which rheumatoid factor (48–50) and parasite-specific IgG levels are high (27–32), making it more likely that amastigotes derived from lesions would be opsonized with host IgG. Our model would predict that disease exacerbation caused by immune complexes would only occur late in disease, after parasite-specific IgG was generated. We predict that the re-infection of macrophages by IgG-opsonized amastigotes would be the trigger for IL-10 production. For these reasons, we performed in vivo infection studies in which we inhibited ERK activation relatively late in disease, after the lesions had progressed for 21 days. The administration of ERK inhibitors at this late time still exhibited a significant influence on disease progression, decreasing lesion size and reducing parasite burdens. This administration also resulted in reduced IL-10 levels in the lesions, but not in the draining lymph nodes, suggesting that localized ERK-dependent production of IL-10 in the lesions was responsible for lesion progression.

In summary, our current findings detail the molecular mechanisms of IL-10 production by amastigote-infected macrophages. They reveal a central role for the MAPK, ERK that is required for maximal IL-10 production. These studies lead to several predictions. The first is that the activation of ERK in any infectious disease may predispose the host to inhibitory IL-10 production. These studies confirm a role for IL-10 during disease progression, and they may lead to the development of a new class of therapeutics to treat human visceral leishmaniasis. Finally, these studies would predict that vaccines against intracellular pathogens might be more effective if administered in the presence of an ERK inhibitor.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant AI55576.

Abbreviations used in this paper: BMMϕ, bone marrow-derived macrophage; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; CT, cycle threshold; Fp., footpad-derived; HA, hyaluronic acid; LA, Leishmania amazonensis; LMW-HA, low m.w. HA; MOI, multiplicity of infection; PI, propidium iodide; Syk, spleen tyrosine kinase; Qrt-PCR, quantitative real-time PCR.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Herwaldt BL. Leishmaniasis. Lancet. 1999;354:1191–1194. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)10178-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kane MM, Mosser DM. Leishmania parasites and their ploys to disrupt macrophage activation. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2000;7:26–31. doi: 10.1097/00062752-200001000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sacks D, Sher A. Evasion of innate immunity by parasitic protozoa. Nat. Immunol. 2002;3:1041–1047. doi: 10.1038/ni1102-1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nandan D, Knutson KL, Lo R, Reiner NE. Exploitation of host cell signaling machinery: activation of macrophage phosphotyrosine phosphatases as a novel mechanism of molecular microbial pathogenesis. J. Leukocyte Biol. 2000;67:464–470. doi: 10.1002/jlb.67.4.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donnelly RP, Sheikh F, Kotenko SV, Dickensheets H. The expanded family of class II cytokines that share the IL-10 receptor-2 (IL-10R2) chain. J. Leukocyte Biol. 2004;76:314–321. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0204117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conti P, Kempuraj D, Frydas S, Kandere K, Boucher W, Letourneau R, Madhappan B, Sagimoto K, Christodoulou S, Theoharides TC. IL-10 subfamily members: IL-19, IL-20, IL-22, IL-24 and IL-26. Immunol. Lett. 2003;88:171–174. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(03)00087-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grutz G. New insights into the molecular mechanism of interleukin-10-mediated immunosuppression. J. Leukocyte Biol. 2005;77:3–15. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0904484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chatelain R, Mauze S, Coffman RL. Experimental Leishmania major infection in mice: role of IL-10. Parasite Immunol. 1999;21:211–218. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.1999.00224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murray HW, Lu CM, Mauze S, Freeman S, Moreira AL, Kaplan G, Coffman RL. Interleukin-10 (IL-10) in experimental visceral leishmaniasis and IL-10 receptor blockade as immunotherapy. Infect. Immun. 2002;70:6284–6293. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.11.6284-6293.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kane MM, Mosser DM. The role of IL-10 in promoting disease progression in leishmaniasis. J. Immunol. 2001;166:1141–1147. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.2.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Padigel UM, Alexander J, Farrell JP. The role of interleukin-10 in susceptibility of BALB/c mice to infection with Leishmania mexicana and Leishmania amazonensis. J. Immunol. 2003;171:3705–3710. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.7.3705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buxbaum LU, Scott P. Interleukin 10- and Fcγ receptor-deficient mice resolve Leishmania mexicana lesions. Infect. Immun. 2005;73:2101–2108. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.4.2101-2108.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Belkaid Y, Piccirillo CA, Mendez S, Shevach EM, Sacks DL. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells control Leishmania major persistence and immunity. Nature. 2002;420:502–507. doi: 10.1038/nature01152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noben-Trauth N, Lira R, Nagase H, Paul WE, Sacks DL. The relative contribution of IL-4 receptor signaling and IL-10 to susceptibility to Leishmania major. J. Immunol. 2003;170:5152–5158. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.10.5152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Belkaid Y, Hoffmann KF, Mendez S, Kamhawi S, Udey MC, Wynn TA, Sacks DL. The role of interleukin (IL)-10 in the persistence of Leishmania major in the skin after healing and the therapeutic potential of anti-IL-10 receptor antibody for sterile cure. J. Exp. Med. 2001;194:1497–1506. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.10.1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karp CL, el-Safi SH, Wynn TA, Satti MM, Kordofani AM, Hashim FA, Hag-Ali M, Neva FA, Nutman TB, Sacks DL. In vivo cytokine profiles in patients with kala-azar: marked elevation of both inter-leukin-10 and interferon-γ. J. Clin. Invest. 1993;91:1644–1648. doi: 10.1172/JCI116372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murray HW, Moreira AL, Lu CM, DeVecchio JL, Matsuhashi M, Ma X, Heinzel FP. Determinants of response to interleukin-10 receptor blockade immunotherapy in experimental visceral leishmaniasis. J. Infect. Dis. 2003;188:458–464. doi: 10.1086/376510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lang R, Rutschman RL, Greaves DR, Murray PJ. Autocrine deactivation of macrophages in transgenic mice constitutively overexpressing IL-10 under control of the human CD68 promoter. J. Immunol. 2002;168:3402–3411. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.7.3402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miles SA, Conrad SM, Alves RG, Jeronimo SM, Mosser DM. A role for IgG immune complexes during infection with the intracellular pathogen Leishmania. J. Exp. Med. 2005;201:747–754. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brightbill HD, Plevy SE, Modlin RL, Smale ST. A prominent role for Sp1 during lipopolysaccharide-mediated induction of the IL-10 promoter in macrophages. J. Immunol. 2000;164:1940–1951. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benkhart EM, Siedlar M, Wedel A, Werner T, Ziegler-Heitbrock HW. Role of Stat3 in lipopolysaccharide-induced IL-10 gene expression. J. Immunol. 2000;165:1612–1617. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.3.1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu YW, Tseng HP, Chen LC, Chen BK, Chang WC. Functional cooperation of simian virus 40 promoter factor 1 and CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein β and δ in lipopolysaccharide-induced gene activation of IL-10 in mouse macrophages. J. Immunol. 2003;171:821–828. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.2.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cao S, Liu J, Song L, Ma X. The protooncogene c-Maf is an essential transcription factor for IL-10 gene expression in macrophages. J. Immunol. 2005;174:3484–3492. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lucas M, Zhang X, Prasanna V, Mosser DM. ERK activation following macrophage FcγR ligation leads to chromatin modifications at the IL-10 locus. J. Immunol. 2005;175:469–477. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.1.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Im SH, Hueber A, Monticelli S, Kang KH, Rao A. Chromatin-level regulation of the IL10 gene in T cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:46818–46825. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401722200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shoemaker J, Saraiva M, O'Garra A. GATA-3 directly remodels the IL-10 locus independently of IL-4 in CD4+ T cells. J. Immunol. 2006;176:3470–3479. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.6.3470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Junqueira PM, Orsini M, Castro M, Passos VM, Rabello A. Antibody subclass profile against Leishmania braziliensis and Leishmania amazonensis in the diagnosis and follow-up of mucosal leishmaniasis. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2003;47:477–485. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(03)00141-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghosh AK, Dasgupta S, Ghose AC. Immunoglobulin G subclass-specific antileishmanial antibody responses in Indian kala-azar and post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 1995;2:291–296. doi: 10.1128/cdli.2.3.291-296.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Casato M, de Rosa FG, Pucillo LP, Ilardi I, di VB, Zorzin LR, Sorgi ML, Fiaschetti P, Coviello R, Lagana B, Fiorilli M. Mixed cryoglobulinemia secondary to visceral leishmaniasis. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:2007–2011. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199909)42:9<2007::AID-ANR30>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jeronimo SM, Teixeira MJ, Sousa A, Thielking P, Pearson RD, Evans TG. Natural history of Leishmania (Leishmania) chagasi infection in Northeastern Brazil: long-term follow-up. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2000;30:608–609. doi: 10.1086/313697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Galvao-Castro B, Sa Ferreira JA, Marzochi KF, Marzochi MC, Coutinho SG, Lambert PH. Polyclonal B cell activation, circulating immune complexes and autoimmunity in human American visceral leishmaniasis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1984;56:58–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elassad AM, Younis SA, Siddig M, Grayson J, Petersen E, Ghalib HW. The significance of blood levels of IgM, IgA, IgG and IgG subclasses in Sudanese visceral leishmaniasis patients. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1994;95:294–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1994.tb06526.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Teixeira MC, de Jesus SR, Sampaio RB, Pontes-de-Carvalho L, Dos-Santos WL. A simple and reproducible method to obtain large numbers of axenic amastigotes of different Leishmania species. Parasitol. Res. 2002;88:963–968. doi: 10.1007/s00436-002-0695-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hodge-Dufour J, Noble PW, Horton MR, Bao C, Wysoka M, Burdick MD, Strieter RM, Trinchieri G, Pure E. Induction of IL-12 and chemokines by hyaluronan requires adhesion-dependent priming of resident but not elicited macrophages. J. Immunol. 1997;159:2492–2500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Termeer C, Benedix F, Sleeman J, Fieber C, Voith U, Ahrens T, Miyake K, Freudenberg M, Galanos C, Simon JC. Oligosaccharides of hyaluronan activate dendritic cells via Toll-like receptor 4. J. Exp. Med. 2002;195:99–111. doi: 10.1084/jem.20001858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiang D, Liang J, Fan J, Yu S, Chen S, Luo Y, Prestwich GD, Mascarenhas MM, Garg HG, Quinn DA, et al. Regulation of lung injury and repair by Toll-like receptors and hyaluronan. Nat. Med. 2005;11:1173–1179. doi: 10.1038/nm1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Plows LD, Cook RT, Davies AJ, Walker AJ. Activation of extracellular-signal regulated kinase is required for phagocytosis by Lymnaea stagnalis haemocytes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1692:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Song X, Tanaka S, Cox D, Lee SC. Fcγ receptor signaling in primary human microglia: differential roles of PI-3K and Ras/ERK MAPK pathways in phagocytosis and chemokine induction. J. Leukocyte Biol. 2004;75:1147–1155. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0403128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goriely S, Van LC, Dadkhah R, Libin M, De WD, Demonte D, Willems F, Goldman M. A defect in nucleosome remodeling prevents IL-12(p35) gene transcription in neonatal dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 2004;199:1011–1016. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Feng GJ, Goodridge HS, Harnett MM, Wei XQ, Nikolaev AV, Higson AP, Liew FY. Extracellular signal-related kinase (ERK) and p38 mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases differentially regulate the lipopolysaccharide-mediated induction of inducible nitric oxide synthase and IL-12 in macrophages: Leishmania phosphoglycans subvert macrophage IL-12 production by targeting ERK MAP kinase. J. Immunol. 1999;163:6403–6412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mathur RK, Awasthi A, Wadhone P, Ramanamurthy B, Saha B. Reciprocal CD40 signals through p38MAPK and ERK-1/2 induce counteracting immune responses. Nat. Med. 2004;10:540–544. doi: 10.1038/nm1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsan MF, Gao B. Endogenous ligands of Toll-like receptors. J. Leukocyte Biol. 2004;76:514–519. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0304127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Park JS, Svetkauskaite D, He Q, Kim JY, Strassheim D, Ishizaka A, Abraham E. Involvement of Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 in cellular activation by high mobility group box 1 protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:7370–7377. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306793200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peters C, Aebischer T, Stierhof YD, Fuchs M, Overath P. The role of macrophage receptors in adhesion and uptake of Leishmania mexicana amastigotes. J. Cell Sci. 1995;108:3715–3724. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.12.3715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guy RA, Belosevic M. Comparison of receptors required for entry of Leishmania major amastigotes into macrophages. Infect. Immun. 1993;61:1553–1558. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.4.1553-1558.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kima PE, Constant SL, Hannum L, Colmenares M, Lee KS, Haberman AM, Shlomchik MJ, Mahon-Pratt D. Internalization of Leishmania mexicana complex amastigotes via the Fc receptor is required to sustain infection in murine cutaneous leishmaniasis. J. Exp. Med. 2000;191:1063–1068. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.6.1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Colmenares M, Constant SL, Kima PE, Mahon-Pratt D. Leishmania pifanoi pathogenesis: selective lack of a local cutaneous response in the absence of circulating antibody. Infect. Immun. 2002;70:6597–6605. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.12.6597-6605.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carvalho EM, Andrews BS, Martinelli R, Dutra M, Rocha H. Circulating immune complexes and rheumatoid factor in schistosomiasis and visceral leishmaniasis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1983;32:61–68. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1983.32.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Newkirk MM. Rheumatoid factors: host resistance or autoimmunity? Clin. Immunol. 2002;104:1–13. doi: 10.1006/clim.2002.5210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pearson RD, De Alencar JE, Romito R, Naidu TG, Young AC, Davis JS. Circulating immune complexes and rheumatoid factors in visceral leishmaniasis. J. Infect. Dis. 1983;147:1102. doi: 10.1093/infdis/147.6.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]