STRUCTURED ABSTRACT

Objectives

Our purpose was to determine whether factors that regulate angiogenesis are altered in peripheral arterial disease (PAD) and whether these factors are associated with the severity of PAD.

Background

Alterations in angiogenic growth factors occur in cardiovascular disease (CVD), but whether these factors are altered in PAD or correlate with disease severity is unknown.

Methods

Plasma was collected from patients with PAD (n=46) and healthy control subjects (n=23). PAD patients included those with intermittent claudication (IC, n=23) and critical limb ischemia (CLI, n=23). Plasma angiopoietin-2 (Ang2), soluble Tie2 (sTie2), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), soluble VEGF receptor-1 (sVEGFR-1), and placenta growth factor (PlGF) were measured by ELISA. In vitro, endothelial cells (ECs) were treated with recombinant VEGF to investigate effects on sTie2 production.

Results

Plasma concentrations of sTie2 (P<0.01), Ang2 (P<0.001), and VEGF (P<0.01), but not PlGF or sVEGFR-1, were significantly greater in PAD patients compared to controls. Plasma Ang2 was significantly increased in both IC and CLI compared to controls (p<0.0001), but there was no difference between IC and CLI. Plasma VEGF and sTie2 were similar in controls and IC but were significantly increased in CLI (P<0.001 vs. control or IC). Increased sTie2 and VEGF were independent of CVD risk factors or the ankle-brachial index, and VEGF treatment of ECs in vitro significantly increased sTie2 shedding.

Conclusions

VEGF and sTie2 are significantly increased in CLI, and sTie2 production is induced by VEGF. These proteins may provide novel biomarkers for CLI, and sTie2 may be both a marker and a cause of CLI.

Keywords: Peripheral arterial disease, soluble Tie2, vascular endothelial growth factor, critical limb ischemia, biomarkers

INTRODUCTION

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) is characterized by atherosclerosis of non-cardiac vascular beds and most commonly affects the lower extremities. Although widely under-recognized, PAD is a major health problem, affecting 8 to 12 million individuals in the United States (1). The two major clinical manifestations of PAD of the lower extremities are intermittent claudication (IC) and critical limb ischemia (CLI), which have markedly different clinical outcomes (2). IC is characterized by reproducible pain on exertion that is relieved with rest. CLI is the most severe form of PAD and is characterized by the inability of arterial blood flow to meet the metabolic demands of resting muscle or tissue, resulting in rest pain and/or tissue necrosis, which frequently necessitates amputation (3,4). Whereas annual mortality in patients with IC is only 1–2%, the annual risk of death in patients with CLI is up to 20% (3,4). Therefore, early identification would be expected to provide improved treatment options for patients with PAD.

Currently, the ankle-brachial index (ABI) is the standard for diagnosis of PAD, however the correlation between ABI and severity of PAD is poor (5). Aside from the ABI, there are no other reliable diagnostic tests for PAD. Furthermore, the diagnosis of IC vs. CLI is purely clinical. Patients with IC and CLI can present with virtually identical clinical risk factors (e.g., tobacco use, diabetes mellitus), peripheral hemodynamic parameters, and degree of atherosclerotic burden (6). Thus, minimally invasive tests or biomarkers to diagnose PAD and potentially distinguish between IC and CLI are needed.

In PAD, atherosclerotic arterial occlusive disease results in tissue ischemia and varying degrees of collateral blood vessel growth (i.e., angiogenesis). The extent of collateral blood vessel formation has the potential to impact the clinical manifestations of PAD, thus insufficient angiogenesis may be responsible for the different clinical presentations of patients with IC and CLI. A number of angiogenic growth factors and endogenous inhibitors of angiogenesis have the potential to modulate vascular growth in PAD. Among these, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-A is perhaps the most important pro-angiogenic factor, as it is required for both physiological and pathological angiogenesis (7), and even minor changes in its expression can lead to dramatic alterations in vascular growth and remodeling (8). The related placenta growth factor (PlGF) binds a common receptor, VEGF receptor-1 (VEGFR-1), and although it is not required for normal embryonic vascular development, it plays a critical role in pathological angiogenesis (9). The angiopoietins are ligands for the endothelial receptor Tie2 (10), and angiopoieitin-2 (Ang2) is upregulated by VEGF (11) and in some cases has been shown to be required for VEGF-mediated angiogenesis (12). Interestingly, soluble forms of both VEGFR-1 and Tie2 are produced and secreted into the circulation, where they can bind their respective growth factors and inhibit angiogenesis (13). Whereas soluble VEGFR-1 (sVEGFR-1) is produced by alternative splicing of the VEGFR1 gene (14), soluble Tie2 (sTie2) results from proteolytic cleavage of the full-length, membrane-bound receptor (15), and both proteins have been implicated in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease (16,17).

In this report, we hypothesized that differences in expression of these angiogenic growth factors and/or their soluble receptors might provide markers of PAD and its different clinical manifestations. To investigate this possibility, plasma from control subjects and patients with IC and CLI was analyzed for changes in the pro-angiogenic growth factors Ang2, VEGF-A, and PlGF, along with their soluble receptors sVEGFR-1 and sTie2, which act as endogenous inhibitors of angiogenesis. We found that patients with PAD have significantly higher plasma concentrations of Ang2, VEGF, and sTie2 compared to control subjects, but only VEGF and sTie2 concentrations distinguish patients with CLI from those with IC.

METHODS

Subject recruitment

Subjects with PAD were recruited consecutively from the vascular medicine clinics at Duke University Medical Center, and control subjects were recruited from the vascular screening clinics if they showed no evidence of PAD, as demonstrated by an ankle-brachial index (ABI) >1.0 or other diagnostic testing. All patient studies were approved by the Duke University Institutional Review Board. All patients were over 18 years of age and able to give informed consent for a single 10 ml blood draw. The study population was comprised of 23 control subjects without PAD and 46 patients with PAD. PAD subjects included 23 patients with intermittent claudication (IC) and 23 patients with critical limb ischemia (CLI), based on the Rutherford criteria (18). IC patients had an ABI of 0.5–0.9 and exercise-limiting claudication, and CLI subjects were identified by an ABI <0.5 and the presence of either a non-healing lower extremity ulcer, rest pain, or gangrene. Control subjects were age- and gender-matched, and were without clinical evidence of vascular, metabolic, or neoplastic disease based on history and physical examination and routine laboratory studies. Patients were excluded from all groups if they had evidence of acute coronary syndromes and/or acute decompensated heart failure in the previous 6 weeks or Child-Pugh class C liver disease. Sample size was determined based on 80% power to detect a significant difference in at least one measured factor between control and PAD subjects without distinction between IC and CLI subgroups. The subjects’ demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics

| Control

(n=23) |

Intermittent

Claudication (n=23) |

Critical

Limb Ischemia (n=23) |

P (ANOVA) |

P (χ2, IC vs. CLI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (min-max), yrs | 51.7(36–72) | 56.1 (40–69) | 62.3 (29–90) | 0.02 | 0.25 |

| Male, n (%) | 14 (61.2) | 12 (52.2) | 15 (65.2) | 0.001 | |

| Caucasian, n (%) | 13 (56.5) | 15 (65.2) | 17 (74.1) | 0.13 | |

| ABI*, median (min-max) | 1.09 (0.91–1.36) (n=22) | 0.55 (0.48–0.86) (n=21) | 0.39 (0.08–0.53) (n=17) | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0 (0.0) | 4 (17.4) | 9 (42.9) | 0.003 | |

| Smoking history, n (%) | 11 (47.8) | 16 (69.5) | 18 (78.2) | 0.001 | |

| Prior Coronary Artery Disease, n (%) | 3 (14.3) | 9 (39.1) | 17 (74.1) | 0.37 | |

| Prior Lower Extremity Vascular Intervention | 0 (0.0) | 9 (39.1) | 19 (82.6) | 0.001 | |

| Hyperlipidemia (LDL>130) | 8 (34.7) | 15 (65.2) | 11 (47.8) | 0.37 | |

| Statin use | 4 (17.3) | 19 (82.6) | 16 (69.5) | 0.08 | |

| Hypertension | 7 (30.4) | 14 (60.8) | 15 (65.2) | 0.01 | |

| ACEI/ARB** | 2 (8.6) | 8 (34.8) | 11 (47.8) | 0.37 |

ABI = ankle-brachial index; ABI data were not available for all patients

ACEI/ARB = angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker

Sample acquisition and analysis of angiogenesis-modulating factors

Blood was collected by venipuncture into EDTA-containing tubes. Whole blood samples were placed on ice and immediately centrifuged at 2000 ×g for 5 minutes at 4°C for plasma separation. Plasma was aliquoted and stored at −80°C. The concentrations of sTie2, VEGF-A165, Ang2, placenta growth factor (PlGF), and soluble VEGF receptor-1 (sVEGFR-1) were quantified using commercially available ELISA kits (R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Assay sensitivities, quantified as the mean minimal detectable concentration for each assay, were: sTie2, 14 pg/ml; VEGF-A, 5.0–9.0 pg/ml; Ang2, 8.3 pg/ml; PlGF, 7 pg/ml; sVEGFR-1, 3.5 pg/ml. Coefficients of variation (intra-assay precision) were less than 4% for all assays.

Cell culture studies

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were harvested from fresh umbilical cords and phenotyped as described previously (19) and used between passages 2 and 6. Cells were grown in endothelial growth medium (EGM)-MV (Cambrex) until confluent. The cells were then changed to serum-free medium, and triplicate samples were treated with vehicle or with recombinant human VEGF165 (25ng/mL; R&D Systems) for 24 hours. The conditioned media were then collected and sTie2 concentration was quantified by ELISA, as described above. ELISA data are presented as the means ± the standard deviation (SD) from triplicate samples. Experiments were repeated on at least three separate occasions. Statistical comparisons were performed using Student’s t-test, and significance was set at P<0.05.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 16.0 for Windows. Patient demographic data were compared across all three groups by ANOVA for continuous variables followed by chi-squared analysis to compare IC and CLI patients. Categorical variables were compared between IC and CLI groups using a non-parametric chi-squared test. Categorical variables that were significantly different between the IC and CLI patients were controlled for using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) to compare levels of VEGF and sTie2 within the PAD cohort. Similarly, ANCOVA was used to control for the effects of differences in ABI on VEGF and sTie2 concentrations in IC vs. CLI patients. For analysis of ELISA data, which were not normally distributed, the data were log-transformed and analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Fisher’s protected least significant difference post-hoc test or Student’s t-test where appropriate. Graphical data are presented as the non-log-transformed values and are expressed as the mean ± SD. Significance was set at P<0.05.

RESULTS

Baseline patient characteristics

The baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. Comparing patients with IC and CLI, a significantly greater percentage with CLI were male, diabetic, hypertensive, and had a history of smoking and peripheral vascular intervention (Table 1). There were no significant differences in the use of cardiovascular medications (ACEI/ARB or statins) between patients with IC and CLI (Table 1).

Analysis of angiogenic growth factors and inhibitors in PAD and control subjects

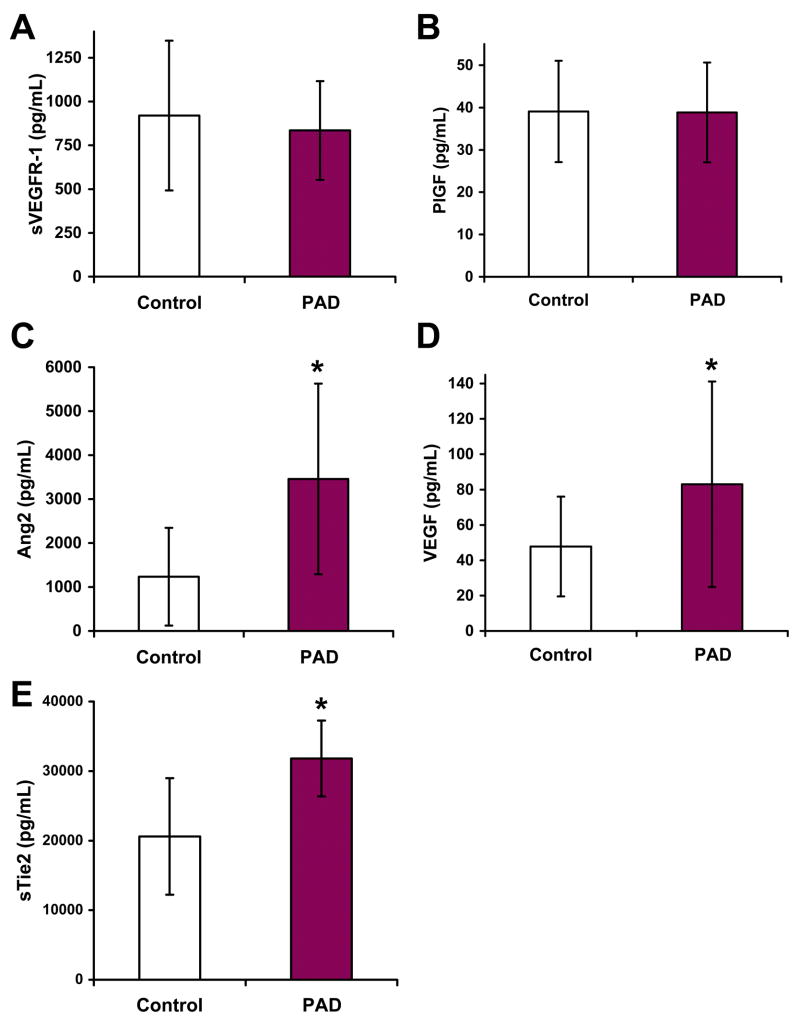

Plasma concentrations of the five different factors were analyzed in controls vs. all PAD patients combined. Plasma concentrations of sVEGFR-1 and PlGF were not significantly different in PAD patients compared to controls (Fig. 1A and B). However, levels of Ang2, VEGF, and sTie2 were significantly higher in PAD patients (Fig. 1C–E).

Figure 1. Plasma concentrations of Ang2, VEGF, and sTie2 are increased in PAD.

Plasma concentrations of sVEGFR-1 (A), PlGF (B), Ang2 (C), VEGF (D), and Tie2 (E) were measured in control subjects (n=23) and patients with PAD (n=46). Concentrations of sVEGFR-1 and PlGF were not significantly different between the two populations, however Ang2 (*, P<0.0001), VEGF (*, P<0.01), and sTie2 (*, P<0.01) were significantly greater in PAD patients.

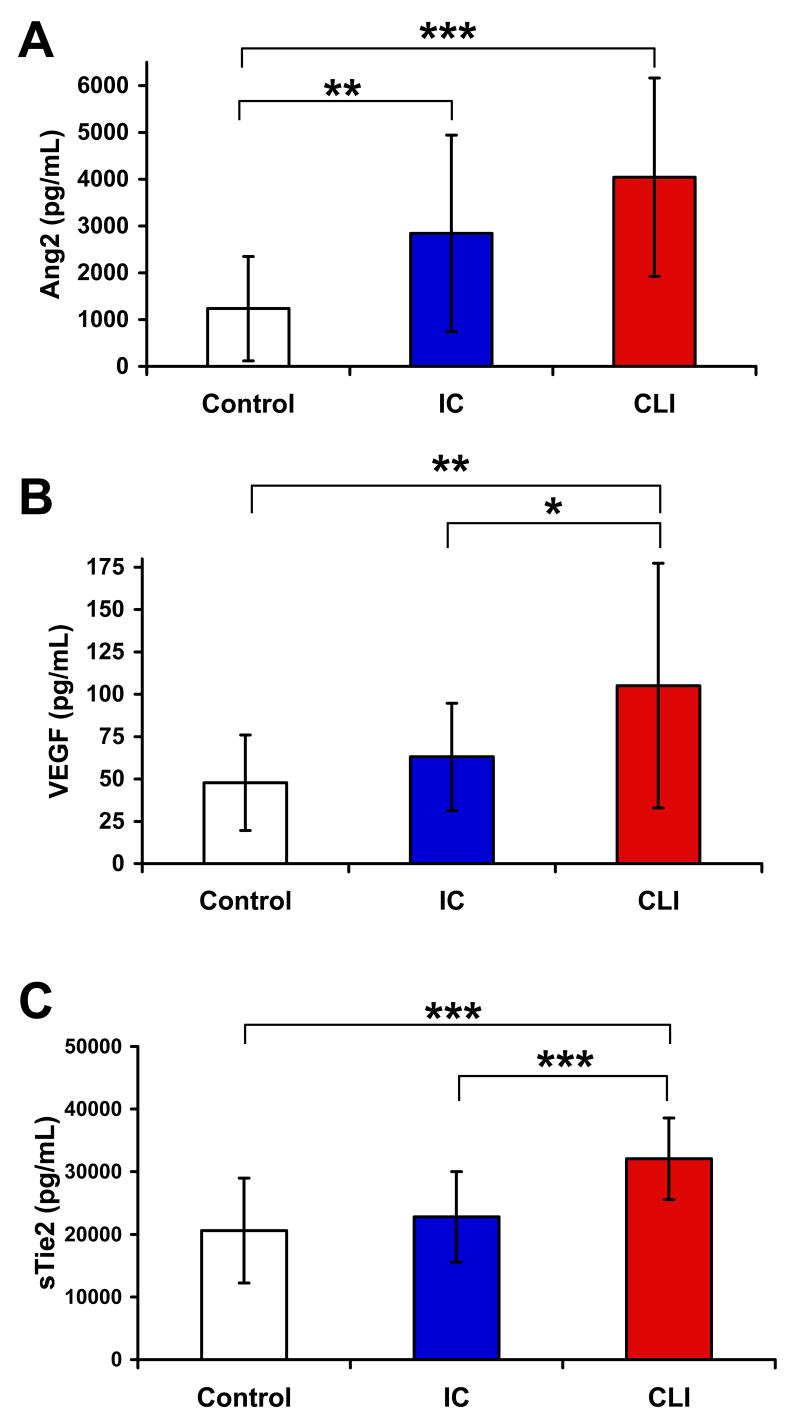

Analysis of angiogenic growth factors and inhibitors within PAD groups (IC vs. CLI)

Visually, there was a stepwise increase in plasma Ang2 expression from control subjects to patients with IC to patients with CLI (Fig. 2A). Although Ang2 concentrations were significantly greater in both PAD groups compared to controls, Ang2 expression was not statistically different in patients with IC and CLI (Fig. 2A). In contrast, plasma VEGF expression was not significantly increased in IC patients compared to controls (Fig. 2B). However, plasma VEGF expression was significantly higher in patients with CLI compared to those with IC (Fig. 2B). Similarly, plasma sTie2 levels were not significantly different in patients with IC compared to controls, but they were significantly higher in CLI patients compared to either IC patients or controls. Mean sTie2 levels in the three groups were 20.6 ± 1.8, 22.8 ± 1.5, and 32.1 ± 1.4 ng/mL in control, IC, and CLI patients, respectively.

Figure 2. Plasma VEGF and sTie2 levels distinguish patients with CLI from controls or patients with IC.

Plasma concentrations of Ang2, VEGF, and sTie2 were measured and compared in control subjects (n=23) and those with IC (n=23) or CLI (n=23). (A) Plasma concentrations of Ang2 were significantly increased in both IC (**, P<0.01) and CLI patients (***, P<0.0001) compared to controls, but there was no significant difference between IC and CLI. (B) VEGF levels were significantly increased in CLI patients compared to controls (**, P<0.01) and IC (*, P<0.05), but there was no difference between IC and controls. (C) sTie2 concentrations were significantly greater in CLI patients compared to controls (***, P<0.0001) and IC (***, P<0.0001), but there was no difference between IC and controls.

sTie2 and VEGF concentrations are independent of cardiovascular risk factors

Circulating concentrations of VEGF and sTie2 could be altered as a result of concomitant cardiovascular disease (CVD) and endothelial dysfunction. Analysis of the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with IC and CLI revealed that significantly more CLI patients were male, diabetic, hypertensive, and had a history of smoking (Table 1). Therefore, we performed analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) for each of these categorical variables with VEGF and sTie2 concentrations and found that differences in both VEGF and sTie2 between the IC and CLI groups remained significant (P<0.001) in our study population.

sTie2 and VEGF concentrations are independent of the ABI

ABI values were lower within our CLI patients than in those with IC (Table 1). However, when we controlled for differences in ABI, the increased concentrations of both sTie2 and VEGF in CLI vs. IC patients remained significantly different (P<0.001). These findings demonstrate that increased levels of sTie2 and VEGF correlate with disease state but not with the ABI, suggesting that these proteins are potential markers of CLI.

Interaction between VEGF and sTie2

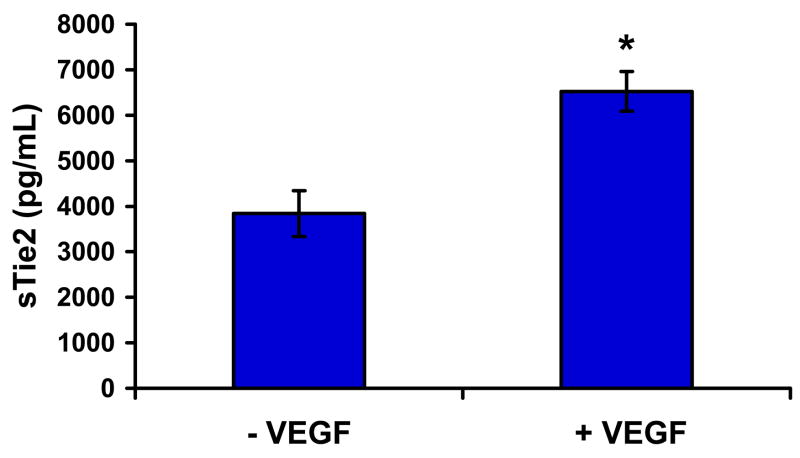

The finding that sTie2 and VEGF concentrations were similarly elevated in subjects with CLI compared to controls or those with IC suggested a potential mechanistic link between VEGF and sTie2. VEGF is known to activate proteases upon stimulation of endothelial cells (7), and sTie2 is a proteolytic cleavage product of the full-length, membrane-bound receptor (20). Moreover, VEGF has been shown to induce proteolysis of the related Tie1 receptor (21). Therefore, we stimulated human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) with recombinant human VEGF and analyzed cell conditioned media for the presence of cleaved sTie2 by ELISA. VEGF induced a significant increase in sTie2 in vitro (Fig. 3), suggesting that increased sTie2 levels in CLI are a result of increased VEGF expression.

Figure 3. sTie2 production is induced by VEGF in vitro.

HUVECs were stimulated with VEGF-A165 (25 ng/mL) for 24 hours. Concentration of sTie2 in the cell conditioned media was quantified by ELISA. VEGF treatment significantly increased release of sTie2 (*, P<0.01).

DISCUSSION

Peripheral arterial disease is a major health care problem in the US, and the prevalence of PAD is increasing. Although the ABI is currently the gold standard for the diagnosis of PAD, there are a number of limitations to its use, and new diagnostic tests are needed. Because PAD is characterized by decreased tissue perfusion and tissue hypoxia, we hypothesized that concentrations of circulating angiogenic growth factors and/or inhibitors of angiogenesis would be altered in subjects with PAD, and these factors might provide important diagnostic and therapeutic targets in this disease. We found that plasma concentrations of Ang2, VEGF, and sTie2 were all significantly elevated in patients with PAD compared to control subjects. Furthermore, plasma concentrations of VEGF and sTie2, but not Ang2, were significantly increased in patients with critical limb ischemia compared to those with intermittent claudication. Increases in VEGF and sTie2 in CLI patients were independent of CVD risk factors and the ABI. Moreover, VEGF was found to induce shedding of sTie2 from endothelial cells in vitro, suggesting a potential mechanistic link between these two proteins. Taken together, these findings suggest that sTie2 and VEGF may provide novel biomarkers for PAD in general and CLI more specifically. These results have implications for understanding the pathophysiology and potentially improving the diagnosis and treatment of PAD.

Despite its increasing prevalence, PAD continues to be clinically under-recognized. Recent data indicate that a significant percentage of patients with PAD are asymptomatic or they present with atypical symptoms (22). Moreover, patients with PAD frequently have concomitant CAD, and their risk of cardiovascular events is significantly higher than in patients without PAD. As a result, the early identification of PAD is of paramount importance, as it would lead to earlier and more aggressive cardiovascular risk factor modification. The identification of novel biomarkers of PAD would aid substantially in this effort. To this end, Wilson et al recently used an unbiased proteomic approach to demonstrate that β2-microglobulin (β2M) is upregulated in the serum of patients with PAD (23). β2M is a component of the class I major histocompatibility complex and is present on virtually all cell membranes, and although the mechanism of its increased release is not understood, its identification as a potential biomarker of PAD represents an important step forward in the diagnosis and management of this disease (24). Proteomic techniques such as the mass spectroscopy approach used by Wilson et al provide an attractive means to identify potential protein biomarkers. However, an important limitation of these approaches is that they can detect only a small subset of the total serum proteome. Many serum proteins are masked by albumin or other abundant proteins, and a number of proteins of interest, including most cytokines and growth factors, are present in serum at concentrations that are below the level of detection with these techniques. Therefore, the hypothesis-driven, targeted approach used in our study provides an important complement to investigate potential biomarkers for PAD.

PAD is characterized by tissue ischemia, and the resulting tissue hypoxia provides a potent angiogenic stimulus. Therefore, PAD should result in upregulation of angiogenic factors in order to induce a compensatory angiogenic response, and VEGF, Ang2, and sVEGFR-1 are all known to be upregulated by hypoxia in vitro (25–27). A number of studies have examined circulating levels of angiogenesis-modulating proteins in the setting of cardiovascular disease or in patients with CVD risk factors, such as hypertension and diabetes mellitus. Similar to our results, plasma concentrations of VEGF, Ang2, and sTie2 have been found to be increased the setting of coronary artery disease, acute coronary syndromes (17,28), and hypertension (29). Increased VEGF and Ang2 have also been demonstrated in the setting of diabetes (30), although there appear to be no prior data on sTie2 levels in diabetics. In the context of PAD, only VEGF and sVEGFR-1 have been studied previously, and consistent with our findings, plasma VEGF concentrations were found to be higher in patients with PAD compared to controls (31–33). Also in agreement with our results, circulating levels of sVEGFR-1 were not increased in patients with PAD but were either unchanged (31,33) or reduced (32) compared to controls. Importantly, after controlling for major demographic and cardiovascular risk factors in our study, the differences in circulating sTie2 and VEGF levels in CLI patients remained significant.

Our study subdivided PAD patients by their diagnosis of intermittent claudication or critical limb ischemia, which have markedly different outcomes. Currently, the diagnosis of IC vs. CLI is largely clinical and is based on a combination of signs, symptoms, and, to a certain degree, the ABI. Our finding that VEGF and sTie2 were significantly increased in patients with CLI compared to IC indicates that plasma concentrations of these proteins may distinguish between these two conditions. To our knowledge, only one study has attempted to correlate expression of angiogenic proteins with severity of PAD. Makin et al (31) examined VEGF levels in PAD patients as a function of the ABI and found that VEGF concentrations did not differ in patients with ABIs above or below 0.52. Although that study did not classify patients clinically as having CLI, no correlation was found between plasma VEGF concentration and the presence of rest pain (31). A critical difference in our study is that patients were given a clinical diagnosis of CLI that was not based on the ABI alone, since it correlates poorly with disease state. Importantly, our data demonstrate a significant association between levels of sTie2 or VEGF and the clinical diagnosis of CLI that is independent of the ABI. These findings suggest that sTie2 and/or VEGF may provide novel biomarkers for this manifestation of PAD.

Whereas VEGF is likely upregulated as a compensatory response to ischemia in PAD, sTie2 appears more likely to play a role in the pathogenesis of the disease. Although IC and CLI have traditionally been thought of as early vs. late or minor vs. severe variants of the same disease, recent evidence suggests that these manifestations of PAD may be caused by distinct mechanisms. In this regard, the upregulation of an inhibitor of angiogenesis like sTie2 could worsen the clinical presentation despite having a similar extent of vascular occlusive disease. If so, sTie2 could serve as a target for therapeutic intervention in PAD. Furthermore, the increase in circulating levels of both VEGF and sTie2 in CLI patients suggests a mechanistic link between these two proteins. Accordingly, our data demonstrated that VEGF induced proteolytic cleavage and shedding of sTie2 in vitro, and recent concomitant work from our laboratory has demonstrated that this process is mediated through the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt pathway (15). Thus, it is possible that ischemia-induced increases in VEGF expression result in dysregulated cleavage of sTie2, thereby limiting the angiogenic response to tissue hypoxia in those patients with the most severe ischemia, eventually resulting in CLI.

The regulation of Tie2 cleavage and subsequent shedding of sTie2 is poorly understood. Previous studies have demonstrated sTie2 in the serum of healthy individuals (20) as well as in patients with a variety of cardiovascular diseases, including congestive heart failure, hypertension, and acute coronary syndromes (17,29,34). Moreover, in renal cell carcinoma patients, sTie2 concentrations correlated with severity of disease and decreased survival (35). Our study is the first to examine sTie2 levels in PAD, and the correlation of sTie2 with CLI provides important insights into this manifestation of PAD.

Study Limitations

Although a clear limitation of the current study is the modest sample size, a unique feature of the study is the analysis of subclassifications of patients with PAD (e.g., IC and CLI). Moreover, investigation of changes in factors involved in angiogenesis provides novel insights into the pathophysiology of this disease and its different manifestations. Although our results suggest that plasma concentrations of Ang2 are not significantly different between patients with IC and CLI, the current study was underpowered to rule out a type II error in this analysis (i.e., a false negative). Thus, assessment of larger populations will be necessary to confirm whether Ang2 might also serve as a marker of CLI as well as to validate our observations on sTie2 and VEGF in this population. Furthermore, investigation of temporal changes in these factors in PAD populations may be clinically relevant, and additional studies will be needed to establish quantitative values of sTie2 and/or VEGF that define CLI with relatively high sensitivity and specificity. The targeted, hypothesis-driven approach used here to investigate changes in angiogenesis modulatory proteins is limited in its analysis of only a small subset of potential biomarkers of PAD. Therefore, additional unbiased proteomic approaches, as described recently for the identification of β2M (23), might lead to the identification of additional PAD biomarkers.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that plasma levels of sTie2 and VEGF are significantly increased in patients with PAD and that increases in these proteins distinguish patients with CLI from those with IC. Because the signs and symptoms of CLI can overlap with those of other disease states, including neuropathies and venous ulcers, these results could have important implications for the diagnosis of CLI. These results also demonstrate a potential mechanistic link between VEGF and sTie2 in PAD, suggesting that sTie2 may serve not only as a marker of CLI but also as a viable target for therapeutic intervention in this disease.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by NIH grants R01HL70165 and R21DK069673 (to CDK); R01 HL075752 (to BHA); and R36AG027584 (to CMF); by a Grant-in-Aid (0655493U) from the Mid-Atlantic Affiliate of the American Heart Association (to CDK); and by a grant from Medtronic, Inc. (to RGM). CMF was supported in part by a Fellowship Award from the UNCF-Merck Foundation.

Abbreviations List

- ABI

ankle-brachial index

- ACEI

angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor

- Ang2

angiopoietin-2

- ARB

angiotensin receptor blocker

- CLI

critical limb ischemia

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- HUVECs

human umbilical vein endothelial cells

- IC

intermittent claudication

- PAD

peripheral arterial disease

- PlGF

placenta growth factor

- sVEGFR-1

soluble VEGF receptor 1

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

Footnotes

This work was presented in part at the 17th Annual Scientific Sessions of the Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, Philadelphia, PA, June, 2006

Conflict of Interest/Financial Disclosures: None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Criqui MH. Peripheral arterial disease--epidemiological aspects. Vasc Med. 2001;6:3–7. doi: 10.1177/1358836X0100600i102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dolan NC, Liu K, Criqui MH, et al. Peripheral artery disease, diabetes, and reduced lower extremity functioning. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:113–20. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ouriel K. Peripheral arterial disease. Lancet. 2001;358:1257–64. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06351-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDermott MM, Hahn EA, Greenland P, et al. Atherosclerotic risk factor reduction in peripheral arterial diseasea: results of a national physician survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:895–904. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.20307.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weitz JI, Byrne J, Clagett GP, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of chronic arterial insufficiency of the lower extremities: a critical review. Circulation. 1996;94:3026–49. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.11.3026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McDermott MM, Liu K, Greenland P, et al. Functional decline in peripheral arterial disease: associations with the ankle brachial index and leg symptoms. JAMA. 2004;292:453–61. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.4.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferrara N. Vascular endothelial growth factor: basic science and clinical progress. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:581–611. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carmeliet P, Ferreira V, Breier G, et al. Abnormal blood vessel development and lethality in embryos lacking a single VEGF allele. Nature. 1996;380:435–439. doi: 10.1038/380435a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carmeliet P, Moons L, Luttun A, et al. Synergism between vascular endothelial growth factor and placental growth factor contributes to angiogenesis and plasma extravasation in pathological conditions. Nat Med. 2001;7:575–83. doi: 10.1038/87904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones N, Iljin K, Dumont DJ, Alitalo K. Tie receptors: new modulators of angiogenic and lymphangiogenic responses. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:257–67. doi: 10.1038/35067005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oh H, Takagi H, Suzuma K, Otani A, Matsumura M, Honda Y. Hypoxia and vascular endothelial growth factor selectively up-regulate angiopoietin-2 in bovine microvascular endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:15732–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.22.15732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gale NW, Thurston G, Hackett SF, et al. Angiopoietin-2 is required for postnatal angiogenesis and lymphatic patterning, and only the latter role is rescued by Angiopoietin-1. Dev Cell. 2002;3:411–23. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00217-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siemeister G, Schirner M, Weindel K, et al. Two independent mechanisms essential for tumor angiogenesis: inhibition of human melanoma xenograft growth by interfering with either the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor pathway or the Tie-2 pathway. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3185–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barleon B, Siemeister G, Martinybaron G, Weindel K, Herzog C, Marme D. Vascular endothelial growth factor up-regulates its receptor fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (flt-1) and a soluble variant of flt-1 in human vascular endothelial cells. Cancer Res. 1997;57:5421–5425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Findley CM, Cudmore MJ, Ahmed A, Kontos CD. VEGF induces Tie2 shedding via a phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt dependent pathway to modulate Tie2 signaling. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2619–26. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.150482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hazarika S, Dokun AO, Li Y, Popel AS, Kontos CD, Annex BH. Impaired angiogenesis after hindlimb ischemia in type 2 diabetes mellitus: differential regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1 and soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1. Circ Res. 2007;101:948–56. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.160630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee KW, Lip GYH, Blann AD. Plasma Angiopoietin-1, Angiopoietin-2, Angiopoietin Receptor Tie-2, and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Levels in Acute Coronary Syndromes. Circulation. 2004;110:2355–2360. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000138112.90641.7F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rutherford RBBJ, Ernst C, et al. Recommended Standard for Reports Dealing with Lower Extremity Ischemia: Revised Version. J Vasc Surg. 1997;26:517–538. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(97)70045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jaffe EA, Nachman RL, Becker CG, Minick CR. Culture of human endothelial cells derived from umbilical veins. Identification by morphologic and immunologic criteria. J Clin Invest. 1973;52:2745–56. doi: 10.1172/JCI107470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reusch P, Barleon B, Weindel K, et al. Identification of a soluble form of the angiopoietin receptor TIE-2 released from endothelial cells and present in human blood. Angiogenesis. 2001;4:123–31. doi: 10.1023/a:1012226627813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yabkowitz R, Meyer S, Black T, Elliott G, Merewether LA, Yamane HK. Inflammatory cytokines and vascular endothelial growth factor stimulate the release of soluble tie receptor from human endothelial cells via metalloprotease activation. Blood. 1999;93:1969–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirsch AT, Criqui MH, Treat-Jacobson D, et al. Peripheral arterial disease detection, awareness, and treatment in primary care. JAMA. 2001;286:1317–24. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.11.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson AM, Kimura E, Harada RK, et al. Beta2-microglobulin as a biomarker in peripheral arterial disease: proteomic profiling and clinical studies. Circulation. 2007;116:1396–403. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.683722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Annex BH. Is a simple biomarker for peripheral arterial disease on the horizon? Circulation. 2007;116:1346–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.726299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Detmar M, Brown LF, Berse B, et al. Hypoxia regulates the expression of vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor (VPF/VEGF) and its receptors in human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1997;108:263–268. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12286453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pichiule P, Chavez JC, LaManna JC. Hypoxic Regulation of Angiopoietin-2 Expression in Endothelial Cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:12171–12180. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305146200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gerber HP, Condorelli F, Park J, Ferrara N. Differential transcriptional regulation of the two vascular endothelial growth factor receptor genes - flt-1, but not flk-1/KDR, is up-regulated by hypoxia. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:23659–23667. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.38.23659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chung NAY, Makin AJ, Lip GYH. Measurement of the soluble angiopoietin receptor tie-2 in patients with coronary artery disease: development and application of an immunoassay. Eur J Clin Invest. 2003;33:529–535. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2003.01173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nadar SK, Blann A, Beevers DG, Lip GYH. Abnormal angiopoietins 1&2, angiopoietin receptor Tie-2 and vascular endothelial growth factor levels in hypertension: relationship to target organ damage [a sub-study of the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial (ASCOT)] J Intern Med. 2005;258:336–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2005.01550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lim HS, Blann AD, Chong AY, Freestone B, Lip GY. Plasma vascular endothelial growth factor, angiopoietin-1, and angiopoietin-2 in diabetes: implications for cardiovascular risk and effects of multifactorial intervention. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2918–24. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.12.2918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Makin AJ, Chung NA, Silverman SH, Lip GY. Vascular endothelial growth factor and tissue factor in patients with established peripheral artery disease: a link between angiogenesis and thrombogenesis? Clin Sci (Lond) 2003;104:397–404. doi: 10.1042/CS20020182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blann AD, Belgore FM, McCollum CN, Silverman S, Lip PL, Lip GY. Vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptor, Flt-1, in the plasma of patients with coronary or peripheral atherosclerosis, or Type II diabetes. Clin Sci (Lond) 2002;102:187–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blann AD, Belgore FM, Constans J, Conri C, Lip GY. Plasma vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptor Flt-1 in patients with hyperlipidemia and atherosclerosis and the effects of fluvastatin or fenofibrate. Am J Cardiol. 2001;87:1160–3. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)01486-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chong AY, Caine GJ, Freestone B, Blann AD, Lip GY. Plasma angiopoietin-1, angiopoietin-2, and angiopoietin receptor tie-2 levels in congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:423–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harris AL, Reusch P, Barleon B, Hang C, Dobbs N, Marme D. Soluble Tie2 and Flt1 extracellular domains in serum of patients with renal cancer and response to antiangiogenic therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:1992–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]