Abstract

Mutations in several steps of de novo purine synthesis lead to human inborn errors of metabolism often characterized by mental retardation, hypotonia, sensorineural hearing loss, optic atrophy, and other features. In animals, the phosphoribosylglycinamide transformylase (GART) gene encodes a trifunctional protein carrying out 3 steps of de novo purine synthesis, phosphoribosylglycinamide synthase (GARS), phosphoribosylglycinamide transformylase (also abbreviated as GART), and phosphoribosylaminoimidazole synthetase (AIRS) and a smaller protein that contains only the GARS domain of GART as a functional protein. The GART gene is located on human chromosome 21 and is aberrantly regulated and overexpressed in individuals with Down syndrome (DS), and may be involved in the phenotype of DS. The GART activity of GART requires 10-formyltetrahydrofolate and has been a target for anti-cancer drugs. Thus, a considerable amount of information is available about GART, while less is known about the GARS and AIRS domains. Here we demonstrate that the amino acid residue glu75 is essential for the activity of the GARS enzyme and that the gly684 residue is essential for the activity of the AIRS enzyme by analysis of mutations in the Chinese hamster ovary (CHO-K1) cell that require purines for growth. We report the effects of these mutations on mRNA and protein content for GART and GARS. Further, we discuss the likely mechanisms by which mutations inactivating the GART protein might arise in CHO-K1 cells.

Keywords: somatic cell mutations, gene evolution, enzyme activity, metabolism, genetic disorders

1. Introduction

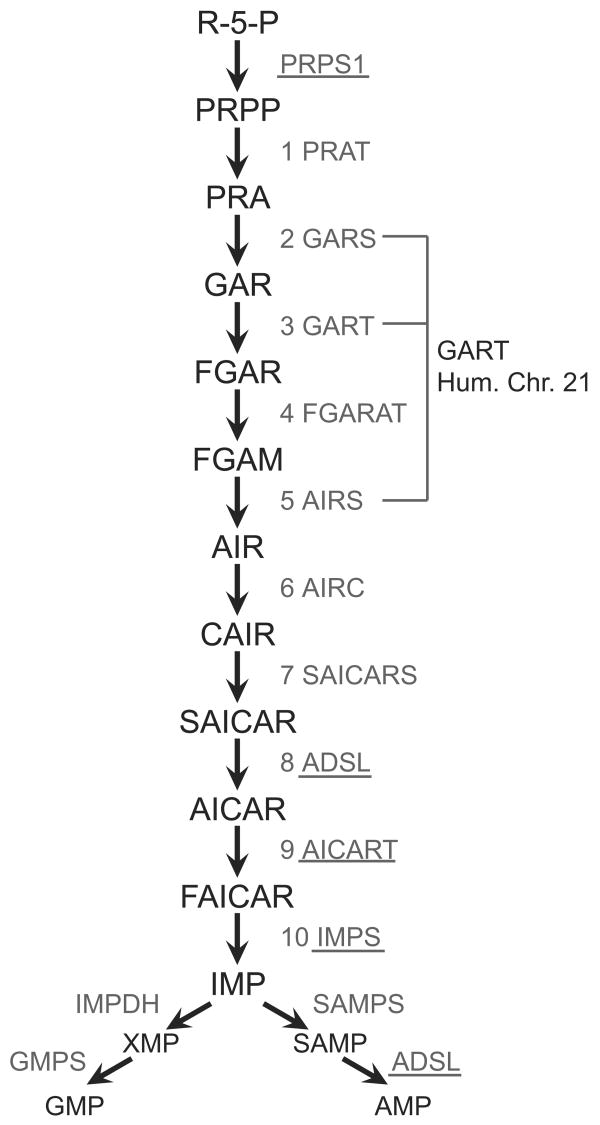

The de novo purine biosynthetic pathway is a target for currently used cancer chemotherapy agents, and new agents continue to be developed. Aberrant purine synthesis leads to significant pathology in humans. For example, purine overproduction due to genetic alterations in PRPP synthase (PRPS1) resulting in increased activity leads to mental retardation, sensorineural deafness, ataxia, and hyperuricemia that can result in kidney damage and gouty arthritis if untreated (Becker et al., 1994). Loss of function mutations in PRPS1 leads to conditions with related phenotypes: Arts syndrome, characterized by mental retardation, early onset hypotonia, ataxia, delayed motor development, hearing impairment, and optic atrophy (de Brouwer et al. 2007), a variant of Charcot-Marie Tooth syndrome (CMTX5), which is characterized by inherited peripheral neuropathy, sensorineural hearing loss, gating disturbance, and visual loss, and Rosenberg-Choutorian syndrome, which has features similar to CMTX5 (Kim et al., 2007). Deficiency of adenylosuccinate lyase (ADSL), step 8 in Figure 1, leads to psychomotor delay often accompanied by autistic features, hypotonia, and seizures (Spiegel et al., 2006; Mouchegh et al., 2007). Phosphoribosylaminoimidazolecarboxamide transformylase/IMP synthase (ATIC) deficiency leads to a syndrome characterized by dysmorphic features, severe neurological defects, and congenital blindness (Marie et al., 2004). Thus, defects in several steps of de novo purine synthesis lead to inborn errors of metabolism, often with similar features, and it seems reasonable to hypothesize that defects in other enzymes in the pathway may also lead to inborn errors.

Fig. 1.

The de novo purine biosynthesis pathway. Enzymes associated with pathology are underlined. The steps encoded by the GART gene are indicated. Abbreviations are: R-5-P, ribose-5-phosphate; PRPP, phosphoribosylpyrophosphate; PRA, phosphoribosylamine; GAR, phosphoribosylglycinamide; FGAR, phosphoribosylformylglycinamide; FGAM, phosphoribosylformylglycineamidine; AIR, phosphoribosylaminoimidazole; CAIR, phosphoribosylaminoimidazole- carboxylate; SAICAR, phosphoribosylsuccinylaminoimidazole; AICAR, phosphoribosylaminoimidazolecarboaxamide; FAICAR, phosphoribosylformylaminoimidazolecarboxamide; IMP, inosine monophosphate; SAMP, adenylosuccinate; XMP, xanthosine monophosphate; AMP, adenosine monophosphate; GMP, guanosine monophosphate. Pathway enzymes are: (1) PRAT, phosphoribosylamidotransferase; (2) GARS, GAR synthetase; (3) GART, GAR transformylase; (4) FGARAT, FGAR amidotransferase; (5) AIRS, AIR synthetase; (6) AIRC, AIR carboxylase; (7) SAICARS, SAICAR synthetase; (8) and (12) ADSL, adenylosuccinate lyase; (9) AICART, AICAR transformylase; (10) IMPS, IMP synthetase; SAMPS, SAMP synthetase; IMPDH, IMP dehydrogenase; GMPS, GMP synthetase. PRPS1, phosphoribosylpyrophosphate synthase 1

One enzyme in the pathway of special interest is GART. In mammals, GART is part of a trifunctional protein, also known as GART, which carries out two additional steps of de novo purine synthesis, GARS and AIRS (Figure 1). GART function, which requires 10-formyltetrahydrofolate as a cofactor, is the best characterized of the three steps because it has been a target for cancer chemotherapy (Dahms et al., 2005). However, even though some inhibitors of GART showed some promise, none have become a mainstay of therapy. The GARS and AIRS domains of GART, which do not require folates or other cofactors, are less well characterized and present additional chemotherapeutic targets.

The GART gene is located on human chromosome 21, and is trisomic in DS (Moore et al., 1977; Patterson, 2007). Individuals with DS have ∼1.5-fold elevated levels of purines in their bodily fluids (Pant et al., 1968). Persons with DS, in addition to essentially ubiquitous intellectual disability of varying severity, almost always have hypotonia and have an increased risk of sensorineural deafness, all of which are common features of inborn errors of purine metabolism. Moreover, GART is aberrantly regulated in the developing cerebellum of individuals with DS (Brodsky et al., 1997) and is overexpressed in fetal heart of individuals with DS (Li et al., 2006). We and others hypothesize that de novo purine synthesis may be elevated in individuals with DS because of increased dosage of the GART gene and that this may be related to the intellectual disabilities and other health problems confronted by individuals with DS (Brodsky et al. 1997; Li et al., 2006). If GART activity is related to the phenotype of DS, then methods that reduce the activity of GART to levels seen in euploid individuals might alleviate some of the consequences of DS. Understanding the mechanism of action of the various activities of GART may aid in developing ways to reduce the activity of one or more of the enzymatic steps of GART for this purpose.

In addition to its possible relevance to human health and development, the evolution, structure, and basic genetics of GART are inherently interesting. Mammals, vertebrates, and insects produce two proteins from the GART gene, one the full length trifunctional protein, and one containing only the amino-terminal GARS domain (Brodsky et al., 1997; Aimi et al,, 1990; Henikoff et al., 1986). The monofunctional GARS protein is produced through cleavage and polyadenylation of the GART gene transcript in the intron separating the last GARS exon and the first AIRS exon (Kan and Moran, 1995; Brodsky et al., 1997; Kan and Moran, 1997). In yeast, the GARS and AIRS domains are carried on a single protein, while GART is on a separate protein. In plants or bacteria, each of the three activities is carried on a separate protein (Li et al., 1999). Thus, there are important differences in the structure and organization of the genes and proteins in different organisms. How this situation arose evolutionarily is unclear.

Two important approaches to understanding the mechanisms of action of the enzymes of purine synthesis are analysis and comparison of the structures of the proteins and analysis of mutations in the genes encoding the enzymes. Both mutations generated by targeted mutagenesis and naturally occurring mutations associated with human inborn errors of metabolism have been studied. Structural analysis can be informative to guide generation of hypotheses, but these need to be tested experimentally. The GART domain of the trifunctional GART gene has been cloned and expressed, allowing study of the GART monofunctional human protein. Structural and functional comparisons of the human and E. coli protein as well as targeted mutagenesis experiments have revealed important differences between these proteins (Manieri et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2002). Similarly, structural and functional analysis coupled with targeted mutagenesis of the ADSL locus reveals important differences between the human, B. subtilis, and E. coli enzymes (Sivendran et al., 2004; Sivendran and Colman, 2008). Thus, specific serine residues in the E. coli enzyme were hypothesized to be important for catalysis. This was then proven by targeted mutagenesis of the relevant residues in the E. coli, B. subtilis, and human ADSLs (Tsai et al., 2007; Sivendran and Colman, 2008). One important point from this work was that the E. coli ADSL might not be a particularly good model for either the human or B. subtilis enzymes (Sivendran and Colman, 2008). These findings demonstrate that comparisons of the bacterial and human structures of enzymes, including GART, while useful, must be interpreted carefully and that hypotheses based on these comparisons need to be validated experimentally, by analysis of normal and mutant proteins.

A further complexity in the case of GART is the multifunctional nature of the mammalian enzyme and the recently demonstrated existence of functional complexes between GART and the other enzymes of de novo purine synthesis under growth conditions requiring purines (An et al., 2008). Determination of the amino acids responsible for this mammalian multiprotein complexing will most likely require study of mutants of the mammalian enzymes.

So far, no examination of mutants affecting the activities or structures of the mammalian GARS and AIRS domains of GART has been reported. Therefore, to elucidate the role of GART in mammalian development, health, and disease, to contribute to the development of additional anti-cancer drugs, and to aid in understanding the evolution and structure of GART, we isolated CHO-K1 mutants that are deficient in the GARS or AIRS enzyme activities (Brodsky et al., 1997; Patterson, 1975). These mutants were isolated solely on the basis of their requirement for purines for growth. This means that these mutations may cause amino acid substitutions or may be due to other changes, for example in the production or stability of GART mRNA or protein. If they result in amino acid substitutions, since there is no bias (except that they affect the function of the enzyme) these mutants may reveal unexpected insights into which amino acids are important for the function and/or stability of GART. These mutants fall into two complementation groups, AdeC and AdeG, as determined by somatic cell hybridization experiments. Here we report the identification of the mutations in CHO-K1 purine auxotrophs of the AdeC and AdeG complementation groups and characterize the purine deficiency phenotype in these CHO-K1 mutant cell lines.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Cell lines and cell culture

The AdeC and 55-1 mutant cell lines have been partially characterized previously (Brodsky et al., 1997). 55-1 is a member of the AdeG complementation group. Therefore, in this manuscript we refer to it as AdeG (55-1). Previously, for example in Brodsky et al. (1997), it was referred to simply as 55-1. For standard, nonselective, growth CHO cell lines were grown in Ham's F12 (Ham, 1965) medium supplemented with 5% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS), penicillin, streptomycin, and the antifungal-amphotericin B.

2.2 Isolation and Northern blot analysis of GARS and GART mRNA

RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Midi (Qiagen) kit and protocol, separated by formaldehyde-borate agarose gel electrophoresis (Derman et al., 1981) and transferred to nylon hybridization membranes (Ausubel, 1987). Probes were generated by amplifying fragments of the hamster GARS and human cyclophilin cDNAs using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in which α-P32 labeled dCTP was directly incorporated in the PCR reaction. Primers used were: GARS; 230F 5′-GATCACACTGTCCTGGCTCA-3′, 662R 5′-CTTCTTCCCCGTCCAGAAACTCT-3′; Cyclophilin; hCyclo23F 5′-GCCGAGGAAAACCGTGTACT-3′, hCyclo183R 5′-CCTTTCTCTCCAGTGCTCAGA-3′. The GARS probe hybridizes to the GARS domain of both the GARS and GART mRNAs. Northern blots were performed using the Ultrahyb reagent and protocol (Ambion) and visualized using a STORM PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA).

2.3 Western blot analysis of GARS and GART proteins

Generation of the GARS monoclonal antibody has been described (Brodsky et al., 1997). Protein isolations were performed as previously described (Barnes et al., 1994). Protein concentrations were determined using the BioRad Microassay reagent. Equal amounts (30-40 μg) of total protein were resolved by gel electrophoresis and electroblotted onto nitrocellulose membranes. Immunoblotting and detection were performed essentially as previously described (Barnes et al., 1994; Brodsky et al., 1997) Protein bands were visualized using CDP-Star substrate according to the supplier's protocol (Applied Biosystems). Images of Western blots were captured using a Diana III camera system (Raytest), and analyzed using AIDA Image Analyzer software (Raytest).

2.3 Relative Specific Enzyme activities of GARS AIRS, and GART in CHO-K1, AdeC, and AdeG (55-1)

Enzyme assays of GARS, AIRS, and GART were carried out using our previously published procedures (Chang et al., 1991). All assays were linear with time and amount of protein and were run in duplicate.

2.4 Sequence analysis of CHO GART cDNAs

To determine the coding sequence of CHO-K1 GART and to identify mutations in AdeC and AdeG (55-1), GART cDNAs were isolated and cloned from CHO-K1 and the mutant cell lines. GART cDNA was amplified from total RNA using GART primers USOUT (5′-GCGGGTTTCATTTTGCTTC-3′) and GARTDSIN2 (5′-GACAAGAGTTTGGGACAAGA-3′) and the SuperScript™ One-Step RT-PCR for Long Templates (Invitrogen). PCR products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. These PCR products were ligated into the pGEM-T Easy TA cloning vector (Promega) and transformed into NovaBlue competent cells according to the supplier's protocol (Novagen). Insert-containing clones were isolated based on blue\white screening and positive restriction digestion of plasmid DNA (Promega Wizard Plus Miniprep Kit).

GART cDNA clones were sequenced using primers that allowed for complete sequence coverage in both directions with overlapping sequence results (Table 1). Sequencing reactions were carried out using the ABI Big Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing kit. Purified products were sequenced using an ABI Prism 377 DNA sequencer. GART sequence data was analyzed using the Sequencher application (Gene Codes).

Table 1.

Oligonucleotides used to sequence and mutagenize the CHO GART cDNA.

| Primer | Sequence 5′-3′ |

|---|---|

| AK1 | ggtgcgggtttcattttgct |

| 638R | ccacaaccactgtttctcca |

| AK4 | gcgcagtggaaagcctttac |

| CHOGT33 | tccaccctagatggcctgct |

| CHOGT34 | ctgttatctctacaccct |

| AIRSUSOUT | gtgtcagcccttgaagaagc |

| DSIN | ttgtaagtcaggccccttgg |

| CHOGT4 | ttgcccagctgtgcaacaag |

| 1713REV | tccagcaacaacagcttcag |

| 2056FWD | cagccattcactgttgccta |

| 2153REV | ggaggactctggggatgttc |

| GARTUSOUT | gaagattcccctcgtgtcaga |

| CHOGT11 | tggcctccatcagattcttg |

| 18US | gctggcctagacaaagcaga |

| 14DS | gaatgccagctttttctgct |

| GARTDSOUT | acgggtaagggctgaagtct |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Oligonucleotides | |

| Oligonucleotide | Sequence 5′-3′ |

| AdeC_EtoK | GTGGTTGTTGGACCAAAGGCCCCTCTAGCTG |

| AdeC_EtoK_R | CAGCTAGAGGGGCCTTTGGTCCAACAACCAC |

| 55-1_GtoD | GCTCACATTACTGGAGATGGACTGCTGGAGAAC |

| 55-1_GtoD_R | GTTCTCCAGCAGTCCATCTCCAGTAATGTGAGC |

| Gly684toLys | GCCTTGGCTCACATTACTGGGAACGGGCTGCTGGAGAACATCC |

| Gly684toLys_R | GGATGTTCTCCAGCAGCCCGTTCCCAGTAATGTGAGCCAAGGC |

| Gly684toPro | CTTGGCTCACATTACTGGGCCTGGGCTGCTGGAGAACATC |

| Gly684toPro_R | GATGTTCTCCAGCAGCCCAGGCCCAGTAATGTGAGCCAAG |

2.5 Sequence analysis of CHO GART genomic regions

Genomic DNA was isolated from CHO-K1, AdeC, and AdeG (55-1) with the PureGene Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Gentra Systems). Regions of the CHO GART gene corresponding to putative mutations in the GART cDNA were amplified with the Expand High Fidelity PCR Kit (Roche) using primers for GARS (230F 5′-GATCACACTGTCCTGGCTCA-3′, 386R 5′-TGGACTCTAACTGGGCTGCT-3) and AIRS (1933F 5′-ATGGGTTTAGCCTTGTGAGGA-3′, 2135R 5′-GGAGGACTCTGGGGATGTTC-3′). PCR products were visualized on 1% agarose gels in 1X Tris-acetate-EDTA containing ethidium bromide. PCR products were purified with the GFX™ PCR DNA and Gel Band Purification Kit (Amersham) and sequenced and analyzed as described above, except 100 ng of PCR product was sequenced.

2.6 Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) of GART in CHO cell-lines

CHO GART probe was produced from two pooled PCR amplified fragments of the genomic CHO GART sequence. A 7 kb fragment spanning exons 3 to 10 was PCR amplified using GART specific primers 230F 5′-GATCACACTGTCCTGGCTCA-3′ and Exon10R 5′-TGCCATGACAACAGTTACGG-3′. A 5 kb GART genomic PCR fragment spanning exons 10 to 16 was amplified with the primers CHOGTE16F1 5′-TGGAGAACATCCCCAGAGTC-3′ and 2764R 5′-TGACAAAAGGGCCAGAGAG-3′. These fragments were then TA cloned into the pGEM-Teasy vector (Promega). Fragments containing the entire insert were released by NotI digestion and 500ng of each fragment were combined and labeled using the Nick Translation Kit (Vysis) with the SpectrumOrange fluorophor (Vysis). Metaphase spreads were prepared for each CHO cell line using standard cytogenetic methods (McCarthy et al., 2004). Metaphase spreads were then co-denatured at 70°C for 5 minutes with 1 μl probe mixed with 4 μl Hybridization Buffer (Vysis). Slides were hybridized overnight at 37°C, washed for 1-2 minutes in 0.4XSSC at 73 ± 1°C and counterstained with DAPI. Hybridized metaphase spreads were visualized using an Olympus epifluorescence microscope and single, dual and triple band pass filters (DAPI, SpectrumOrange). A minimum of 10 metaphase spreads per slide were analyzed, and representative metaphase spreads were captured with the Cytovision imaging system (Applied Imaging Corp.).

2.7 Cloning and mutagenesis of CHO GART gene in a mammalian expression vector

The full-length GART cDNA from CHO-K1 was amplified and cloned into the G418R TA cloning and mammalian expression vector pTarget (Promega). The ends of the insert in this clone (pCMV-GART-K1) were sequenced using vector T7 and Sp6 primers, confirming the presence of full-length CHO GART cDNA.

Site-directed mutagenesis was performed with the QuickChange II site-directed mutagenesis kit and protocol (Stratagene). The primers used to introduce point mutations into pCMV-GART-K1 are listed in Table 1. The presence of the introduced mutations was verified by DNA sequencing as described above. The successfully mutated GART expression constructs, the wild-type GART clone, and the empty pTarget vector were all used for transfection after purification with the Pure Yield Plasmid Midi Prep System (Promega) followed by ethanol precipitation and washing to remove contaminants.

2.8 Transfection of GART cDNA expression constructs into CHO GART mutants

The CHO mutants AdeC and AdeG (55-1) were transfected with the GART cDNA expression constructs using the Lipofectamine 2000 reagent according to the supplier's protocol (Invitrogen).

To select for the ability of transfected cells to grow in purine deficient media, cells were cultured in Ham's F12 without hypoxanthine supplemented with 5% (v/v) twice dialyzed fetal calf serum, antibiotic/antimyotic (Ham, 1965) and G418 (Geneticin®, Gibco) at an active concentration of 400 μg/ml.

Cells were fixed and then stained with crystal violet. Plates were scanned using a digital photograph scanner and the image file of each plate was scored for colonies using the colony-counting tool in the TotalLab™ TL100 software application (Nonlinear Dynamics).

3. Results

3.1 Cloning and sequencing the CHO-K1 GART cDNA

The full-length CHO GART cDNA sequence has an open reading frame of 3030bp (GenBank accession number (EU622913) and codes for a protein with 1010 amino acids. The human and CHO protein sequences are 86% identical and 93% similar. The mouse and CHO protein sequences are 89% identical and 95% similar (Figure S1).

3.2 Sequencing of the mutant cDNAs and genomic DNAs

We sequenced the cloned full-length trifunctional GART cDNA and relevant GART genomic regions from CHO-K1 and the AdeC and AdeG (55-1) mutants. The mutation in AdeC is a G to A transition at nucleotide 223 of the GART coding region resulting in a glutamate (glu) to lysine (lys) substitution at amino acid position 75. The mutation in AdeG (55-1) is a G to A transition at position 2050 resulting in a glycine (gly) to aspartate (asp) substitution at amino acid 684.

To confirm the mutations in each mutant, we sequenced PCR amplification products from genomic DNA from each mutant. In both AdeC and AdeG (55-1), the mutations also appeared in genomic DNA with no evidence of the wild-type sequence.

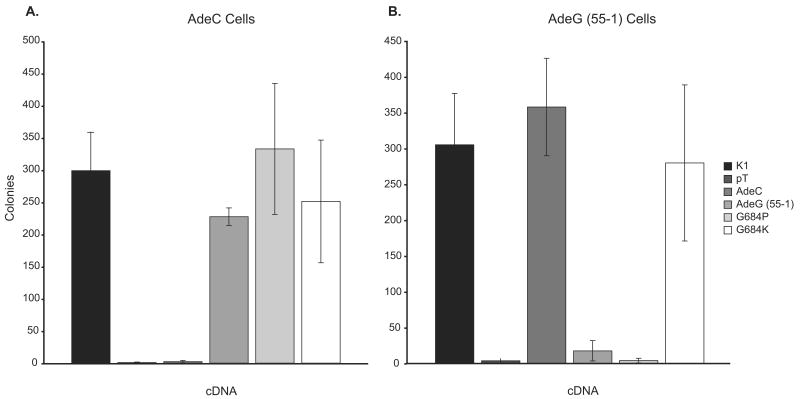

3.3 GART gene mutations cause the purine auxotrophy

To verify that the mutant phenotypes in AdeC and AdeG (55-1) are caused by the mutations identified above, we tested the ability of mutant GART cDNAs to alleviate the purine auxotrophy in these cell lines. For this purpose, we introduced the relevant mutation into the wild-type CHO-K1 cDNA expression construct and transfected the GART mutants to determine whether expression of the mutant cDNAs could alleviate the purine auxotrophy of the various mutants. In each case, we found that the mutant cDNAs could not alleviate the purine auxotrophy in cells with the corresponding mutation. However, the AdeC mutation could alleviate the auxotrophy of the AdeG (55-1) mutant and vice-versa. Wild-type GART alleviated both the AdeC and AdeG (55-1) purine requirements (Figure 2).

Fig. 2.

Transfection of AdeC and AdeG (55-1) cells with wild-type and mutant cDNA constructs. The wild-type and mutant GART clones indicated were transfected into AdeC or AdeG (55-1) cells in F12 without purines and clones able to grow in the absence of purines were scored as described in Materials and Methods. Error bars indicate the standard deviation of the measurements. pT indicates transfection with the empty cloning vector.

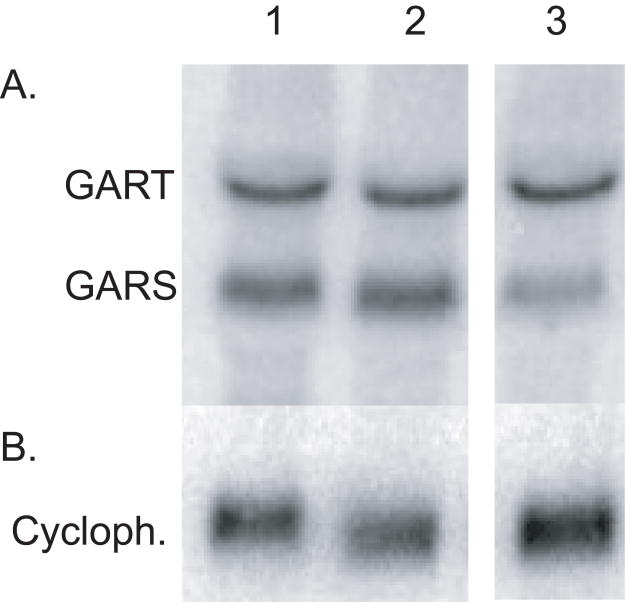

3.4 Northern blot analysis of the CHO-K1 GART mutants

To assess whether the changes in the GART gene in these mutants affect GART transcript sizes or amounts, the mRNAs for monofunctional GARS and trifunctional GART were analyzed by Northern blot using a probe specific for the GARS region (Figure 3). CHO-K1 and the mutants all express significant levels of mRNA for the trifunctional GART and monofunctional GARS transcripts. The approximate lengths of the GART and GARS mRNAs in all cases are 3.2 and 1.7 kb, respectively, similar to the lengths seen in mice (Kan and Moran, 1995; Kan and Moran, 1997). Full length GART cDNAs were also obtained by RT-PCR from all the cell lines (data not shown). The levels of mRNA in CHO-K1 and the two mutants are qualitatively similar, although the Northern blot suggests that mutant AdeG (55-1) may have slightly reduced levels of the GARS transcript on the basis of the apparent differences in the relative intensity of the GART and GARS mRNAs in CHO-K1 and AdeG (55-1). Thus, neither mutation has major effects on GARS or GART mRNA levels.

Fig. 3.

Northern blot of mRNA from wild-type and GART mutant CHO cells. Total RNAs were isolated from CHO cells, separated on 1% agarose-formaldehyde gel, transferred to nylon membrane and probed with (A) Labeled PCR fragment of GARS cDNA. (B) The membrane was stripped then reprobed with a control cyclophilin cDNA. 1 = CHO-K1; 2 = AdeC; 3 = AdeG (55-1).

3.5 Western blot and enzyme activity analysis of the CHO-K1 GART mutants

In a previous study (Brodsky et al., 1997), this laboratory detected GARS (∼50kDa) and GART (∼110 kDa) proteins in CHO-K1 and the two mutants by Western blotting. AdeC produces GARS protein with a consistently observed increased mobility (Fig. S2). Similar mobility shifts for glu to lys substitution have been observed previously (Yannoukakos et al., 1991). In general agreement with our previous studies (Oates et al., 1977; Irwin et al., 1979; Chang et al., 1991; Brodsky et al., 1997; Bleskan and Patterson, unpublished results) AdeC and AdeG (55-1) both contain at least as much GARS and GART protein as CHO-K1 lysates (Fig. S2). Most significantly, AdeC has undetectable levels of GARS enzyme activity, and AdeG (55-1) has undetectable levels of AIRS enzyme activity. AdeC has significant levels of AIRS and GART activity and AdeG (55-1) has significant levels of GARS and GART activity. In each mutant there is a trend towards reduced levels of the remaining enzyme activities.

Based upon the E. coli AIRS structure (Li et al., 1999) and the high level of sequence conservation at the gly684 residue, the gly684asp mutation would alter a well-conserved glycine-rich loop at or near the AIRS active site. This substitution would also introduce a negative charge at this position. To explore whether the effects of this mutation are due to a structural change or a charge change, mutants were created in which amino acid 684 was substituted with lys or proline (pro). The former substitution introduces a positive charge as opposed to the negative charge introduced by aspartate, while the latter is expected to increase the rigidity of the loop and alter its three-dimensional structure.

The cDNA expression constructs with residue 684 mutations were transfected into AdeG (55-1) cells and selected for purine-free growth. When the original AdeG (55-1) mutation (gly684asp) or gly684pro were transfected into AdeG (55-1) cells there was no auxotrophy rescue, while the gly684lys mutation did rescue at levels comparable to the wild-type CHO-K1 cDNA. As expected, all 3 amino acid substitutions relieved the auxotrophy of AdeC cells (Figure 2).

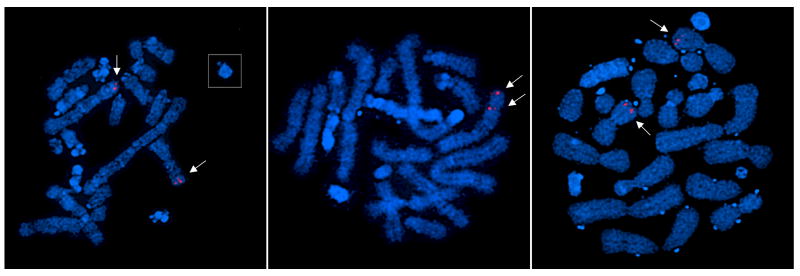

3.6 GART gene copy number in CHO-K1 and AdeC and AdeG (55-1)

To complement our understanding of the relationship between the mutations and the genomic changes in each cell line we determined the number of GART chromosomal loci in metaphase chromosome spreads from CHO-K1 and from the AdeC and AdeG (55-1) mutants using FISH (Figure 4) (McCarthy et al., 2004).

Fig. 4.

CHO-GART copy number in CHO mutants. Fluorescence in situ hybridization of metaphase chromosomes from CHO-K1, AdeC, and AdeG (55-1) cells. The left panel is CHO-K1, the middle panel is AdeC, and the right panel is AdeG (55-1). The probe was made from two fragments of the CHO GART gene that were purified and labeled with SpectrumOrange (Vysis Inc.).

CHO-K1 cells have two copies of the GART allele, both very close to the telomeres of two different chromosomes. The AdeC FISH results show two GART genes on the same chromosome and an apparent reduction in chromosome number, so rearrangement of the two GART-containing chromosomes with each other may have occurred in this cell line. AdeG (55-1) has two copies of GART on different mid-sized, metacentric chromosomes, again demonstrating rearrangement involving the GART containing chromosomes seen in CHO-K1. We cannot determine from this result whether the GART gene was altered by these chromosome rearrangements, but clearly, one copy of the entire gene was not lost during generation of the AdeC or AdeG (55-1) mutations.

4. Discussion

4.1 Identification of the mutations responsible for the purine auxotrophy in AdeC and AdeG (55-1) CHO-K1 mutants

There have been limited genetic analyses of the GART protein from mammals, mainly consisting of targeted mutagenesis and structural studies focused on the human GART domain. In this case, significant differences between the human GART protein and the E. coli protein have been observed (Manieri et al., 2007). These studies suggest that study of the human (or mammalian) GART and GARS proteins are important for their accurate characterization, although clearly comparisons of the mammalian and bacterial proteins will be useful, as described below. The mutations reported here are the first in which mutations with functional significance have been reported for the GARS and AIRS domains of mammalian GART. Our results demonstrate that the defects leading to the purine deficiency in these cells are due to coding region mutations in the relevant enzyme domains as opposed to epigenetic effects such as gene silencing as has been observed for other CHO cell mutants (Harris, 1984). They represent a start toward genetic analysis of these proteins.

The mutation in AdeC is a G to A transition at nucleotide 223 of the GART coding region resulting in a glutamate to lysine substitution at amino acid position 75. The structure of the E. coli GARS enzyme indicates that glu73, which is highly conserved and equivalent to glu75 in CHO GARS, may be responsible for hydrogen bonding to the glycyl moiety of GAR, the product of GARS catalysis (Wang et al., 1998). This observation is consistent with the AdeC CHO mutant phenotype; namely, the glu75lys mutation abolishes cellular GARS enzyme activity but retains at least normal GARS and GART protein levels and more than half of wild-type levels of AIRS and GART activity. Thus, alteration of the glu75 residue does not result in protein instability and degradation. Since this mutant retains at least 50% of AIRS and GART activities compared to CHO-K1, it is evident that the glu to lys mutation does not severely impact the function of the other domains.

The mutation in AdeG (55-1) is a G to A transition at position 2050 resulting in a glycine to aspartate substitution at amino acid 684. Thus, gly684 is essential for AIRS enzyme activity but retains GARS and GART protein and enzyme activities. This finding was confirmed by showing that substitution of residue 684 with pro also inactivates AIRS activity as assessed by transfection studies and does not have a major effect on GARS or GART protein levels.

4.2 Mechanisms by which mutations in CHO-K1 cells can arise

It is of some interest to consider how recessive mutations such as those reported here could be generated in CHO-K1 cells, which should be diploid for the GART locus. The CHO-K1 karyotype has been extensively rearranged, so the possibility existed that CHO-K1 cells might contain only a single copy of the GART gene or that one copy of the gene might be lost in the mutants. However, our FISH analysis demonstrates two signals for GART in CHO-K1 cells. Recently, the inner mitochondrial folate transport protein gene that is mutated in CHO-K1 glyB mutants was found to be present in two copies in CHO-K1 cells but in one copy in the glyB mutant cells (McCarthy et al., 2004; Kao et al., 1969). The authors hypothesized that the single mutant allele in the glyB cells was due to the loss of one wild-type allele during selection of the glyB line. Both the AdeC and AdeG (55-1) mutants reported here apparently remain diploid for the GART locus, although the possibility of rearrangement or epigenetic silencing of one copy of the gene cannot be ruled out. However, both the AdeC and AdeG (55-1) mutations reported here appear to have altered chromosomal locations for one GART allele. Thus, the available evidence from the GlyB, AdeC, and AdeG (55-1) mutants is consistent with the hypothesis that chromosomal rearrangement of the relevant genes is a common feature in generation of mutations in CHO-K1 cells.

4.3 Implications of these results for the structure of mammalian GART

These data are the first to identify amino acids critical for the function of mammalian GARS or AIRS. X-ray crystal structures are not available for human GARS, AIRS, or trifunctional GART. Therefore, we compared the amino acid sequences for the GARS and AIRS domains of CHO GART with the crystal structures of E. coli GARS and AIRS (Wang et al., 1998; Li et al., 1999). The E. coli and CHO GARS domains are 51% identical and 65% similar while homology between the AIRS domains shows 49% identity and 65% similarity. Modeling of the CHO domains with SwissModel using the E. coli structures as templates produced models that were very similar to the E. coli enzymes except in some exposed loops (Guex and Peitsch, 1997).

The mutation in AdeC results in a glu75lys substitution. Mutations that cause human disease are thought to be most likely at amino acid residues that are conserved across species (Miller and Kumar 2001; Vitkup et al., 2003). Glu at this residue is completely conserved in all eukaryotic sequences currently available and in all bacterial sequences examined with the exception that two Clostridia, six Streptococcus strains, Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus, and Cloroflexus auranticans have asp at this position. Of 34 Archaea sequences, all are glu except two, which are asp, a conservative substitution for glu. Two strains of bacteria, Roseiflexus sp. RS-1 and Chloroflexus aurantiacus have serine at this position. Thus, this is a highly conserved amino acid position throughout evolution.

Although glu to lys substitutions are uncommon in interspecies comparisons, lysine is the most common substitution for glutamate in human genetic disease (Miller and Kumar, 2001; Vitkup et al., 2003). Thus, the mutation in AdeC fits the pattern expected for mutations that might be associated with genetic disease.

The gly684asp mutation in AdeG (55-1) is a non-conservative substitution at a remarkably conserved residue. All available eukaryotic AIRS sequences have a glycine at this residue. One bacterial sequence has a serine residue and two have an aspartate at this position. Mutations at gly residues are relatively common in human genetic disease, perhaps because glycine is important for protein structural stability (Vitkup et al., 2003). Thus, again, this mutation follows a pattern consistent with that expected for mutations that cause genetic disease in humans.

This residue corresponds to gly251 in E. coli AIRS, which is the central residue in a highly conserved and short glycine-rich loop between strand β6 and helix α8 of E. coli AIRS (Li et al., 1999). β6 is a component of the proposed AIRS active site and contains histidine 247 and threonine 249, both highly conserved polar residues that could interact with metal ions in the active site. Glycine residues are often found in short loops and enzyme active sites due to the flexibility they allow (Li et al., 1999; Krieger et al., 2005; Yan and Sun, 1997). If this residue serves a similar function in CHO AIRS, substitution of CHO gly684 with a larger, polar, and negatively charged aspartate could disrupt the structure of the AIRS active site. Alternatively, the negative charge introduced by the aspartate might interfere with the active site or introduce attractions or repulsions with other amino acids (of course these substitutions may also cause structural changes). The finding that substitution of a pro at residue 684 in the CHO-K1 enzyme prevents the protein from alleviating the purine auxotrophy of AdeG (55-1) strongly implies that the structural features of glycine are significant for activity. Introduction of a positively charged lysine at this site does not eliminate enzyme activity. Thus, the introduction of a charge itself does not prohibit enzyme function, a finding that is again consistent with this glycine being critical for the structure of the active site of AIRS. It is interesting to note that two bacterial AIRS proteins do have an aspartate at this residue, an observation consistent with this interpretation.

In general, missense mutations can impact proteins and their cellular role by either altering functional sites or decreasing active enzyme levels. Unstable proteins are often degraded, improperly localized, or form aggregates. The most straightforward interpretation of the data presented here is that the glu75lys mutation affects enzyme activity but not protein stability since our Western blot results show that AdeC has GARS and GART protein levels at least equivalent to those found in CHO-K1. The gly684asp mutation in AdeG (55-1) eliminates AIRS enzyme activity but does not appear to result in a decrease in GART (and GARS) protein levels

The information gained from identifying and characterizing the consequences of the mutations in AdeC and AdeG (55-1) enhances the current knowledge of the mammalian GARS and AIRS enzymes. This is important since no genetic studies on the GARS and AIRS domains of the mammalian protein have been reported so far, and it is not clear how well studies on the bacterial GARS, GART, and AIRS proteins apply to the mammalian trifunctional protein. Although it has been hypothesized on the basis of the structural studies that the E. coli GARS, AIRS, and GART proteins might form a complex involving all three proteins, thus mimicking the trifunctional structure of the animal protein, and that this protein might interact with PRAT, the first committed enzyme of de novo purine synthesis to allow channeling of the unstable product of PRAT, PRA, to the GARS active site (Li et al., 1999), complex formation has not yet been detected experimentally in bacteria. A recent elegant study demonstrates that the human GART trifunctional protein does indeed interact with the PRAT in mammalian cells under conditions in which the cells need to synthesize purines (An et al., 2008).

4.4 Possible implications for inborn errors of metabolism and Down syndrome and future studies

Inborn errors have now been associated with 3 genes of de novo purine synthesis, PRPS1, ADSL, and ATIC. All of these inborn errors have neurological consequences and can lead to hypotonia, and many lead to sensorineural hearing loss. We speculate that deficiencies of one or more of the activities of the GART protein (or any other protein in the de novo purine biosynthetic pathway) may also lead to inborn errors in humans. We and others have published methods to detect most of the intermediates of purine biosynthesis (Hards and Patterson, 1988; Friedecký et al., 2007). Lack of GARS, AIRS, or GART activities might be expected to alter purine concentrations or profiles in bodily fluids and/or lead to accumulation of intermediates of de novo purine synthesis. Thus, it seems reasonable to test individuals with developmental delay of unknown origin with these methods. We therefore hypothesize that an analysis of individuals with developmental delay of unknown origin using these methods may uncover clinically relevant alterations in GARS, AIRS, or GART, revealing both basic enzymatic mechanisms and pharmacological targets.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1. Sequence alignment for the GART protein from CHO, Mus musculus, and Homo sapiens. The amino acid sequence of GART from CHO, mouse, and human is shown. Amino acid identities are indicated by grey shadowing, with darker grey indicating amino acids identical in all species and lighter grey indicating amino acids identical in two of three species.

Figure S2. Western blot analysis of GARS-AIRS-GART and GARS protein expression in wild-type (CHO- K1) and mutant CHO cell lines. 30 ug of total protein was separated on a 12% PA gel, transferred to a nylon membrane and immunoblotted with an anti-GARS monoclonal antibody diluted 1:5000. A control blot was probed with a 1:10000 dilution of an anti-actin monoclonal antibody. 1 = CHO-K1; 2 = AdeC; 3 = AdeG (55-1).

Table 2.

Enzyme activities for steps catalyzed by GART gene products in CHO-K1, AdeC, and AdeG (55-1). Units are: GARS and GART, nmols mg-1 min-1; AIRS, pmols mg-1 min-1. ND = not detectable.

| CHO-K1 | AdeC | AdeG (55-1) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| GARS | 82.4 | ND (0) |

53.6 (65) |

| GART | 18.6 | 10.5 (56) |

15.3 (82) |

| AIRS | 10.3 | 7.5 (73) |

ND (0) |

Acknowledgments

We thank Lynne Meltesen, Jean M. Smith, and Billie Carstens (Colorado Genetics Laboratory, Department of Pathology, University of Colorado at Denver Medical School) for the FISH analysis and Guido Vacano, Ph.D. of the Eleanor Roosevelt Institute at the University of Denver for assistance with graphics. DNA sequencing was done at the University of Colorado Cancer Center DNA Sequencing & Analysis Core. The work was supported by NIH grant HD17449 and grants from the Itkin Family Foundation and the Towne Foundation.

Abbreviations

- GAR

phosphoribosylglycinamide

- GART

phosphoribosylglycinamide transformylase

- GARS

phosphoribosylglycinamide synthase

- AIRS

phosphoribosylaminoimidazole synthetase

- CHO

Chinese hamster ovary

- PRPP

phosphoribosylpyrophosphate

- PRPS1

PRPP synthase 1

- CMTX5

Charcot-Marie Tooth syndrome

- ADSL

adenylosuccinate lyase

- ATIC

phosphoribosylaminoimidazolecarboaxamide transformylase/IMP synthase

- FCS

fetal calf serum

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- dNTP(s)

deoxynucleotide triphosphates(s)

- DS

Down syndrome

- FISH

fluorescence in situ hybridization

- DAPI

4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- CMV

cytomegalovirus

- RT-PCR

reverse transcription PCR

- kDa

kiloDaltons

- E. coli

Escherichia coli

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aimi J, Qiu H, Williams J, Dixon JE. De novo purine nucleotide biosynthesis: cloning of human and avian cDNAs encoding the trifunctional glycinamide ribonucleotide synthetase-aminoimidazole ribonucleotide synthetase-glycinamide ribonucleotide transformylase by functional complementation in E. coli. Nuc Acid Res. 1990;18:6665–6672. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.22.6665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An S, Kumar R, Sheets ED, Benkovic SJ. Reversible compartmentalization of de novo purine biosynthetic complexes in living cells. Science. 2008;320:103–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1152241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausubel FM. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. J Wiley; Brooklyn, NY: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes TS, Bleskan JH, Hart IM, Walton KM, Barton JW, Patterson D. Purification of, generation of monoclonal antibodies to, and mapping of phosphoribosyl N-formylglycinamide amidotransferase. Biochemistry. 1994;33:1850–1860. doi: 10.1021/bi00173a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker MA, Nosal JM, Switzer RL, Smith PR, Palella TD, Roessler BJ. Point mutations in PRPS1, the gene encoding the PRPP synthetase (PRS) 1 isoform, underlie X-linked PRS superactivity associated with purine nucleotide inhibitor-resistance. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1994;370:707–710. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-2584-4_147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky G, Barnes T, Bleskan J, Becker L, Cox M, Patterson D. The human GARS-AIRS-GART gene encodes two proteins which are differentially expressed during human brain development and temporally overexpressed in cerebellum of individuals with Down syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:2043–2050. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.12.2043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang FH, Barnes TS, Schild DG, Gnirke A, Bleskan J, Patterson D. Expression of human cDNA encoding a protein containing GAR synthetase, AIR synthetase, and GAR transformylase corrects the defects in mutant Chinese hamster ovary cells lacking these activities. 1991 doi: 10.1007/BF01233066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahms TES, Sainz G, Giroux EL, Caperelli CA, Smith JL. The Apo and ternary complex structures of a chemotherapeutic target: human glycinamide ribonucleotide transformylase. Biochemistry. 2005;44:9841–9850. doi: 10.1021/bi050307g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Brouwer APM, et al. Arts Syndrome Is Caused by Loss-of-Function Mutations in PRPS1. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:507–518. doi: 10.1086/520706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derman E, Krauter K, Walling L, Weinberger CM, Ray M, Darnell JE., Jr Transcriptional control in the production of liver-specific mRNAs. Cell. 1981;23:731–739. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90436-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedecký D, Tomková J, Maier V, Janost'áková A, Procházka M, Adam T. Capillary electrophoretic method for nucleotide analysis in cells: application on inherited metabolic disorders. Electrophoresis 2007. 2007;28:373–380. doi: 10.1002/elps.200600262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guex N, Peitsch MC. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: an environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis. 1997;18:2714–2723. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150181505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ham RG. Clonal growth of mammalian cells in a chemically defined, synthetic medium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1965;53:288–293. doi: 10.1073/pnas.53.2.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hards RG, Patterson D. Resolution of the intermediates of de novo purine biosynthesis by ion-pair reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. Journal of Chromatography. 1988;455:217–224. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)82120-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris M. High-frequency induction by 5-azacytidine of proline independence in CHO-K1 cells. Somat Cell Mol Genet. 1984;10:615–624. doi: 10.1007/BF01535227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henikoff S, Keene MA, Sloan JS, Bleskan J, Hards R, Patterson D. Multiple purine pathway enzyme activities are encoded at a single genetic locus in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:720–724. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.3.720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin M, Oates DC, Patterson D. Biochemical genetics of Chinese hamster cell mutants with deviant purine metabolism: isolation and characterization of a mutant deficient in the activity of phosphoribosylaminoimidazole synthetase. Somatic Cell Genet. 1979;5:203–216. doi: 10.1007/BF01539161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kan JL, Moran RG. Analysis of a mouse gene encoding three steps of purine synthesis reveals use of an intronic polyadenylation signal without alternative exon usage. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:1823–1832. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.4.1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kan JL, Moran RG. Intronic polyadenylation in the human glycinamide ribonucleotide formyltransferase gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3118–3123. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.15.3118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao F, Chasin L, Puck TT. Genetics of somatic mammalian cells. X. Complementation analysis of glycine-requiring mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1969;64:1284–1291. doi: 10.1073/pnas.64.4.1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, et al. Mutations in PRPS1, which encodes the phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate synthetase enzyme critical for nucleotide biosynthesis, cause hereditary peripheral neuropathy with hearing loss and optic neuropathy (CMTX5) Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:552–558. doi: 10.1086/519529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger F, Moglich A, Kiefhaber T. Effect of proline and glycine residues on dynamics and barriers of loop formation in polypeptide chains. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:3346–52. doi: 10.1021/ja042798i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CM, Guo M, Salas M, Schupf N, Silverman W, Zigman WB, Husain S, Warburton D, Thaker H, Tycko B. Cell type-specific over-expression of chromosome 21 genes in fibroblasts and fetal hearts with trisomy 21. BMC Medical Genetics 2006. 2006;7(24) doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-7-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Kappock TJ, Stubbe J, Weaver TM, Ealick SE. X-ray crystal structure of aminoimidazole ribonucleotide synthetase (PurM), from the Escherichia coli purine biosynthetic pathway at 2.5 A resolution. Structure. 1999;7:1155–1166. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(99)80182-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manieri W, Moore ME, Soellner MB, Tsang P, Caperelli CA. Human glycinamide ribonucleotide transformylase: active site mutants as mechanistic probes. Biochemistry. 2007;46:156–63. doi: 10.1021/bi0619270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marie S, Heron B, Bitoun P, Timmerman T, Van den Berghe G, Vincent MF. AICA-ribosiduria: a novel, neurologically devastating inborn error of purine biosynthesis caused by mutation of ATIC. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:1276–1281. doi: 10.1086/421475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy EA, Titus SA, Taylor SM, Jackson-Cook C, Moran RG. A Mutation Inactivating the Mitochondrial Inner Membrane Folate Transporter Creates a Glycine Requirement for Survival of Chinese Hamster Cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:33829–33836. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403677200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MP, Kumar S. Understanding human disease mutations through the use of interspecific genetic variation. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:2319–2328. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.21.2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore EE, Jones C, Kao FT, Oates DC. Synteny between glycinamide ribonucleotide synthetase and superoxide dismutase (soluble) Am J Hum Genet. 1977;29:389–396. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouchegh K, Zikanova M, Hoffmann GF, Kretzschmar B, Kuhn T, Mildenberger E, Stoltenburg-Didinger G, Krijt J, Dvorakova L, Konzik T, Zeman J, Kmoch S, Rossi R. Lethal fetal and early neonatal presentation of adenylosuccinate lyase deficiency: observation of 6 patients in 4 families. J Pediatr. 2007;150:57–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oates DC, Patterson D. Biochemical genetics of Chinese hamster cell mutants with deviant purine metabolism: characterization of Chinese hamster cell mutants defective in phosphoribosylpyrophosphate amidotransferase and phosphoribosylglycinamide synthetase and an examination of alternatives to the first step of purine biosynthesis. Somatic Cell Genet. 1977;3:561–577. doi: 10.1007/BF01539066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pant SS, Moser H, Krane SM. Hyperuricemia in Down's syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1968;28:472–478. doi: 10.1210/jcem-28-4-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson D, Kao FT, Puck TT. Genetics of somatic mammalian cells: biochemical genetics of Chinese hamster cell mutants with deviant purine metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1974;71:2057–2061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.5.2057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson D. Biochemical genetics of Chinese hamster cell mutants with deviant purine metabolism: biochemical analysis of eight mutants. Somat Cell Genet. 1975;1:91–110. doi: 10.1007/BF01538734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson D, Graw S, Jones C. Demonstration, by Somatic Cell Genetics, of Coordinate Regulation of Genes for Two Enzymes of Purine Synthesis Assigned to Human Chromosome 21. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78:405–409. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.1.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson D. Genetic mechanisms involved in the phenotype of Down syndrome. Mental Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2007;13:199–206. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivendran S, Colman RF. Effect of a new non-cleavable substrate analog on wild-type and serine mutants in the signature sequence of adenylosuccinate lyase of Bacillus subtilis and Homo sapiens. Protein Sci. 2008;17:1–13. doi: 10.1110/ps.034777.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivendran S, Patterson D, Spiegel E, McGown I, Cowley D, Colman RF. Two novel mutant human adenylosuccinate lyases (ASLs) associated with autism and characterization of the equivalent mutant Bacillus subtilis ASL. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:53789–53797. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409974200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel EK, Colman RF, Patterson D. Adenylosuccinate lyase deficiency. Mol Genet Metab. 2006;89:19–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2006.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai M, Koo J, Yip P, Colman RF, Segall M, Howell LP. Substrate and product complexes of Escherichia coli adenylosuccinate lyase provide new insights into the enzymatic mechanism. J Mol Biol. 2007;370:541–554. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.04.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitkup D, Sander C, Church GM. The amino-acid mutational spectrum of human genetic disease. Genome Biol. 2003;4:R72. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-11-r72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Kappock TJ, Stubbe J, Ealick SE. X-ray crystal structure of glycinamide ribonucleotide synthetase from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1998;37:15647–15662. doi: 10.1021/bi981405n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan BX, Sun YQ. Glycine Residues Provide Flexibility for Enzyme Active Sites. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:3190–3194. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.6.3190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yannoukakos D, Vasseur C, Driancourt C, Blouquit Y, Delaunay J, Wajcman H, Bursaux E. Human erythrocyte band 3 polymorphism (band 3 Memphis): characterization of the structural modification (Lys 56----Glu) by protein chemistry methods. Blood. 1991;78:1117–1120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Desharnais J, Greasley SE, Beardsley GP, Boger DL, Wilson IA. Crystal structures of human GAR Tfase at low and high pH and with substrate beta-GAR. Biochemistry. 2002;41:14206–14215. doi: 10.1021/bi020522m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Sequence alignment for the GART protein from CHO, Mus musculus, and Homo sapiens. The amino acid sequence of GART from CHO, mouse, and human is shown. Amino acid identities are indicated by grey shadowing, with darker grey indicating amino acids identical in all species and lighter grey indicating amino acids identical in two of three species.

Figure S2. Western blot analysis of GARS-AIRS-GART and GARS protein expression in wild-type (CHO- K1) and mutant CHO cell lines. 30 ug of total protein was separated on a 12% PA gel, transferred to a nylon membrane and immunoblotted with an anti-GARS monoclonal antibody diluted 1:5000. A control blot was probed with a 1:10000 dilution of an anti-actin monoclonal antibody. 1 = CHO-K1; 2 = AdeC; 3 = AdeG (55-1).