Abstract

The initial bronchoconstrictor response of the asthmatic airway depends on airway smooth muscle (ASM) contraction. Intracellular calcium is a key signaling molecule, mediating a number of responses, including proliferation, gene expression, and contraction of ASM. Ca2+ influx through receptor-operated calcium (ROC) or store-operated calcium (SOC) channels is believed to mediate longer term signals. The mechanisms of SOC activation in ASM remain to be elucidated. Recent literature has identified the STIM and ORAI proteins as key signaling players in the activation of the SOC subtype; calcium release–activated channel current (ICRAC) in a number of inflammatory cell types. However, the role for these proteins in activation of SOC in smooth muscle is unclear. We have previously demonstrated a role for STIM1 in SOC channel activation in human ASM. The aim of this study was to investigate the expression and define the potential roles of the ORAI proteins in SOC-associated Ca2+ influx in human ASM cells. Here we show that knockdown of ORAI1 by siRNA resulted in reduced thapsigargin- or cyclopiazonic acid (CPA)–induced Ca2+ influx, without affecting Ca2+ release from stores or basal levels. CPA-induced inward currents were also reduced in the ORAI1 knockdown cells. We propose that ORAI1 together with STIM1 are important contributors to SOC entry in ASM cells. These data extend the major tissue types in which these proteins appear to be major determinants of SOC influx, and suggest that modulation of these pathways may prove useful in the treatment of bronchoconstriction.

Keywords: airway smooth muscle, ORAI, store-operated calcium entry, ion channels

CLINICAL RELEVANCE

Our findings demonstrate expression and roles for ORAI homologs in store-operated calcium influx in human airway smooth muscle cells. Modulation of calcium influx pathways may prove useful in the treatment of bronchoconstriction in asthmatic airways.

Contraction of airway smooth muscle (ASM) is a key response underlying bronchoconstriction in asthmatic airways. Unlike vascular smooth muscle, in which voltage-dependent channels are important in Ca2+ homeostasis, in ASM the contractile response is dependent on both release from intracellular stores and influx through non–voltage-dependent pathways. Thus, major contractile agonists, such as histamine, will activate Ca2+ signals by rapid release from internal stores via activation by inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate followed by a more sustained Ca2+ influx via plasma membrane ion channels (reviewed in Reference 1). In smooth muscle, Ca2+ influx through both receptor-operated calcium (ROC) channels and store-operated calcium (SOC) channels is believed to provide the Ca2+ signals required for long-term signals, sustained contraction, and the refilling of internal Ca2+ stores (2, 3).

The mechanisms of SOC entry in smooth muscle remain unidentified. Recent advances in the investigations of these mechanisms in inflammatory and other cell types have identified both STIM (stromal interaction molecule) and ORAI proteins as critical components of the SOC pathway (4–7). STIM1 has been identified as a single transmembrane protein that resides in both the plasma membrane and the membrane of the sarcoplasmic reticulum (8). Having no channel-like properties, STIM1 is believed to be a Ca2+ sensor, monitoring the Ca2+ content of intracellular stores (9). Current evidence supports the hypothesis that upon depletion of Ca2+ store content, STIM1 aggregates with itself into discrete puncta (7). From there, it interacts with other proteins in the plasma membrane, resulting in the activation of SOC influx.

Further advances followed with the identification of ORAI. There are three known human ORAI homologs: ORAI1 (FLJ14466), ORAI2 (C7prf19), and ORAI3 (MGC13024). ORAI1 was originally identified as being critical for the activation of SOC influx in T cells through investigation of two patients with severe combined immunodeficiency disease (SCID) (4). These patients with SCID had T cells with defective SOC and a single mutation in ORAI1 was found to be responsible. Additional groups have also identified the ORAI homologs as being critical to the SOC pathway (5, 10). These studies have mainly focused on the activity of the Ca2+ release–activated Ca2+ current (ICRAC); a non–voltage-gated, inwardly rectifying, Ca2+-selective current present in T cells and other hematopoietic cells. Small interfering RNA (siRNA)–mediated knockdown of ORAI1 in these cell types resulted in a significant reduction in both ICRAC and store depletion–induced Ca2+ influx. In addition, overexpression of ORAI1 together with STIM1 resulted in a large amplification of ICRAC (5, 10–13). However, ICRAC is not readily detectable in all cell types. Other cell types, including smooth muscle cells, are sensitive to store depletion, yet the SOC currents present are less Ca2+ selective with marked outward rectification. For example, whole cell currents induced by cyclopiazonic acid (CPA) in human bronchial smooth muscle cells have previously been reported (2, 14). The contribution of ORAI to these other SOC currents remains unclear.

We have previously used siRNA-based approaches to clarify the role of STIM1 in SOC-associated Ca2+ influx in primary human ASM (HASM) cells (14). Selective suppression of STIM1 resulted in a reduction of both store depletion– and histamine-induced Ca2+ influx and a reduction in nonselective SOC-associated inward currents in these cells. The aims of the current study were as follows: (1) to investigate the expression and roles of the ORAI homologs in SOC signals in ASM cells using siRNA targeted against ORAI1, 2, and 3; and (2) to further delineate the nature of SOC currents in these cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Unless otherwise stated, all reagents used were obtained from Sigma (Poole, Dorset, UK).

Cells

Human airway tissue was obtained from the bronchi of patients (with no history of asthma) undergoing surgery and with full patient and ethical approval from the Nottingham local research ethics committee. HASM cells were isolated from fresh tissue and cultured using published methods (15).

Transfection of siRNA

All siRNA sequences were designed by and purchased from Ambion (Huntingdon, Cambridge, UK). The sequences targeted were as follows: ORAI1 (FLJ14466) siRNA; AAGCAACGTGCACAATCTCAA, ORAI2 (C7orf19) siRNA; AACCGTTTGGTTCAATGAGGG and ORAI3 (MGC13024) siRNA; AACCATTTCCATTCCTATACA. HASM cells (passage 3–4) were transfected with 20 nM siRNA (final concentration) in serum free Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM; containing 2 mM glutamine) for 6 hours. After 6 hours, the medium was aspirated away and replaced with serum (10% fetal calf serum [FCS]) containing DMEM and incubated for approximately 45 hours longer. The siRNA was transfected into cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) at a final concentration of 2 μl/ml, as per the manufacturer's instructions.

Total RNA Extraction and Reverse Transcriptase–Polymerase Chain Reaction

Total RNA was isolated and purified from pelleted HASM cells using the RNeasy mini kit and QIAshredders (Qiagen, Sussex, UK) following the manufacturer's instructions. Isolated RNA was then reverse transcribed using Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) and random hexamers (Invitrogen). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed on the cDNA (1:5 dilution) to investigate the expression of ORAI1, 2, and 3 in HASM. Specific primers were designed using primer 3 software (16) and the primer sequences are listed in Table 1. Cycling was performed 35 times; first at 94°C, followed by 50°C (annealing temperature), then at 72°C (all for 90 s), followed by 10 minutes at 72°C. PCR products were separated by electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. The identit of the products was confirmed by direct sequencing.

TABLE 1.

PRIMER AND PROBE SEQUENCES FOR REVERSE TRANSCRIPTASE POLYMERASE CHAIN REACTION AND QUANTITATIVE POLYMERASE CHAIN REACTION (TAQMAN)

| Gene | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer | Probe |

|---|---|---|---|

| ORAI1 (Taqman) | CTTCGCCATGGTGGCAAT | CAGGCACTGAAGGCGATGA | AGCTGGACGCTGACC |

| ORAI2 (Taqman) | TCTACCTGAGCAGGGCCAAG | GGGTACTGGTACTGCGTCTCC | CTCCAGCAGGACCTCCGCCCTCC |

| ORAI3 (Taqman) | AGCTTCCAGCCGCACGT | AGGCACTGAAGGCCACCA | TGCCTTGCTCTCGGGCTTCGCC |

| ORAI1 RT-PCR | GACTGGATCGGCCAGAGTTA | CACTGAAGGCGATGAGCAG | N/A |

| ORAI2 RT-PCR | GTCACCTCTAACCACCACTCG | CGGGTACTGGTACTGCGTCT | N/A |

| ORAI3 RT-PCR | GCACGTCTGCCTTGCTCT | GAGGTTGTGGATGTTGCTCA | N/A |

Definition of abbreviations: N/A = not applicable; RT-PCR = reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction.

Real-Time Quantitative PCR (Taqman)

Real-time quantitative (Taqman) PCR was used to determine gene mRNA levels in RNA extracted from HASM cells. The level of ORAI mRNA knockdown was quantitatively measured using the Mx3005P Taqman machine and MxPro software (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Primer and probe assays for ORAI1, 2, and 3 were designed to meet specific criteria using Beacon software (Stratagene). The primer and probe sequences are listed in Table 1; primers were made and purchased from Invitrogen, probes from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA). The 5′ and 3′ nucleotides of the probes were labeled with a reporter (6-carboxy-fluorescein [FAM]) and a quencher (6-carboxy-tetramethylrhodamine [TAMRA]) dye, respectively. The PCRs were performed with the Applied Biosystems Universal Master Mix (Applied Biosystems), using 4 μl diluted cDNA (1:25 dilution), 900-nM primers, and a 250-nM probe in a 20-μl final reaction mixture. The PCR protocol consisted of 10 minutes at 95°C followed by 40 cycles of 30 seconds at 95°C and 60 seconds at 60°C. Each sample was run in triplicate and mRNA knockdown was measured from mRNA obtained from three separate transfections. 18s RNA was used as a reference gene to correct for equal cDNA input. The relative expression of the target gene was calculated using the comparative method (2−ΔΔCt, where Ct indicates the cycle number threshold at which amplification is exponential) (17). Each Taqman assay was initially validated to use this method of analysis by assessing the primer efficiencies by plotting a cDNA standard curve. The primer efficiencies of each assay were all 100 ± 10% and so approximately equal.

Measurement of [Ca2+]i

HASM cells (passage 3–5) were plated in black-walled, clear-bottom, 96-well plates at a density of approximately 10,000 cells per well. The following day, the cells were transfected as previously described and assayed for intracellular Ca2+ 45–50 hours later. At the time of assay, each well of a 96-well plate is predicted to contain approximately 20,000 cells. The cells were loaded with the calcium detection dye Fluo-4AM (Molecular Probes, Leiden, The Netherlands) for 1 hour at room temperature in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS and 2.5 mM probenecid, after which they were washed with Hanks' balanced salt solution containing 10 mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-ethane sulfonic acid (HEPES), 2.5 mM probenecid, 0.1 mM CaCl2, and 1 mM MgCl2, and left at room temperature for 20 minutes before assay. Fluorescence was continuously recorded at wavelengths of 485 nm excitation and 520 nm emission using a Flexstation (Molecular Devices, Wokingham, UK). Cells were stimulated with 10 μM CPA for 4 minutes or 1 μM thapsigargin (TG) for 24 minutes (TG was added in immediately after the wash step) followed by the addition of 1.9 mM CaCl2 (2-mM final concentration). Data are presented as changes in fluorescence intensity compared with the baseline; the area under the curve was used as an estimate of changes in [Ca2+]i.

Patch-Clamp Electrophysiology

Whole cell currents were recorded using an EPC-10 double amplifier and analyzed with Patchmaster version 2.10 software (HEKA, Lambrecht, Germany). Whole cell SOC currents were activated through passive depletion of the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ store with 10 μM CPA. These studies were performed in extracellular solution that was free of Ca2+ to amplify the SOC currents for easier detection. Compositions of intracellular and extracellular solutions were as follows: internal solution: 140 mM Cs-methasulfanate, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM Mg(ATP)2, 5 mM ethyleneglycol-bis-(β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N′-tetraacetic acid (EGTA), 1.5 mM CaCl2, 10 mM HEPES (pH = 7.2, free Ca2+ concentration = 70 nM); external solution: 140 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM CsCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM glucose, 10 mM HEPES (pH = 7.4). The calcium-free solution contained 0.5 mM EGTA and verapamil (5 μM), and niflumic acid (100 μM) was included in the external solution to inhibit any residual L-type voltage Ca2+ channels and Cl− currents. Pipettes were pulled from borosilicate glass capillaries (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) using a pipette puller, model PP-830 (Digitimer Research Instruments, Bunkyo-Ku, Tokyo) and had resistances of 5–8 MΩ when filled with internal solution.

Resuspended HASM cells were placed directly into the cell chamber and allowed to settle. The cell chamber was continuously perfused with external solution at a steady speed of 6 ml/minute. Drugs were delivered through a puffer pipette positioned approximately 50 μm from the cells. Cells were held at a membrane potential of −40 mV and current–voltage relationships were analyzed every 5 seconds from voltage ramps from −100 to +100 mV at a rate of 0.5V · second−1. Currents were filtered at 1 kHz and sampled at 4 kHz. Currents recorded before the activation of the SOC currents were used as a template for subtraction of leak currents. Individual cell current densities were calculated by dividing peak current amplitude at maximum activation of inward current (at −80 mV) and outward current (+80 mV) by cell capacitance.

Western Blot Analysis

Western blot analysis was used to detect ORAI1 protein (∼50 kD) in HASM and to detect changes in protein level after siRNA transfection. HASM cells were scraped from a confluent 75-cm2 flask and collected into ice cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Cells were lysed on ice with a lysis buffer consisting of a complete inhibitor cocktail + 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacectic acid (cat. no. 11-836-153-001; Roche Diagnostics Ltd, West Sussex, UK) with 20 mM Tris base, 0.9% NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 1 μg/ml pepstatin A. The Bio-Rad assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories Ltd., Herts, UK) was used (following manufacturer's instructions) to quantify the level of protein in each sample to ensure equal protein loading. Sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis was used to separate the proteins according to their molecular weight. Briefly, 20 μg protein (denatured) along with a molecular weight protein marker, Bio-Rad Kaleidoscope marker (Bio-Rad Laboratories), was loaded onto an acrylamide gel consisting of a 5% acrylamide stacking gel stacked on top of a 10% acrylamide resolving gel and run through the gel by application of 100 V for approximately 1 hour. Proteins were transferred from the gel to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane using a wet blotting method. The membrane was blocked with 5% Marvel in PBS containing 0.1% Tween20 (PBS-T) and then probed with an anti-ORAI1 (1:1,000) antibody (rabbit polyclonal antibody; Axxora Life Sciences, Nottingham, UK) followed by a peroxidase conjugated secondary (1:10,000) antibody. The enhanced chemiluminescence method of protein detection using enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (Amersham GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) was used to detect labeled proteins.

Statistical Analysis

Averaged data are presented as mean ± SEM. Where appropriate, statistical analysis was assessed by unpaired Student t tests or one-way analysis of variance followed by the Dunnett's test for multiple group comparisons. Data were considered significant at P < 0.05 or P < 0.01.

RESULTS

ORAI mRNA Expression in HASM Cells

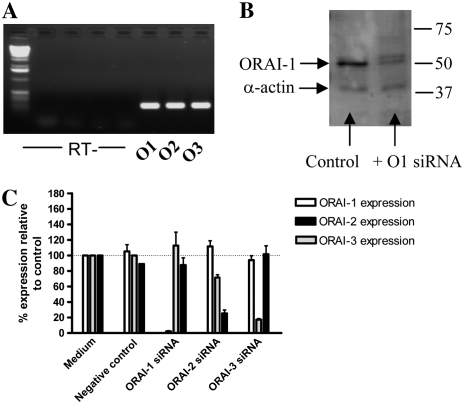

We first examined the expression of the three known human ORAI homologs (ORAI1, 2, and 3) in primary cultured HASM cells. Figure 1A shows the PCR products obtained: all three homologs were detected. Each PCR product was directly sequenced to confirm identity.

Figure 1.

Expression of ORAI homologs in human airway smooth muscle (HASM) and siRNA-targeted knockdown of ORAI homologs. (A) mRNA expression of ORAI1, 2, and 3 in HASM cells using reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) (O1: ORAI1, O2: ORAI2, O3: ORAI3). PCR products were sequenced to confirm expression. No products were detected in the RT samples (i.e., RNA samples that have not been reverse transcribed) to confirm no genomic DNA contamination. (B) Western blot analysis of ORAI1 protein expression after ORAI1 siRNA transfection; expression of smooth muscle α-actin was assessed as a control for equal protein loading. (C) siRNA-mediated knockdown of ORAI1, 2, and 3 mRNA assessed by real-time, quantitative PCR; the effects of individual siRNAs on expression of all ORAI homologs were assessed. The level of ORAI mRNA expression in HASM cells transfected with siRNA was compared relative to an untreated control, which was set to 100%. Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM, cDNA samples were tested in triplicate and the graph represents data from three separate transfections.

siRNA-Mediated Knockdown of ORAI1, 2, and 3

We next obtained selective siRNA sequences to target and knockdown all three homologs. All three siRNAs were purchased from Ambion: sequences are listed in Materials and Methods. Delivery of siRNA to the cells was achieved through use of lipid-based transfection by Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Efficiency of knockdown was assessed with quantitative real-time PCR (Taqman). Figure 1C shows the knockdown of mRNA achieved with each siRNA. The level of ORAI mRNA expression in HASM cells transfected with siRNA was compared relative to an untreated control, which was set to 100%. The Ct values from the untreated medium controls were as follows (mean ± SEM, n = 3); ORAI1 (29.5 ± 0.5), ORAI2 (31.3 ± 0.1), and ORAI3 (31.1 ± 0.2). Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM, cDNA samples were tested in triplicate and the graph represents data from three separate transfections. Transfection with 20 nM ORAI1 siRNA resulted in 97.6 ± 0.8% knockdown of ORAI1 mRNA, without affecting expression of ORAI2 or ORAI3. Transfection with 20 nM ORAI3 siRNA resulted in an 82.7 ± 1.4% reduction of ORAI3 mRNA again without affecting ORAI1 or 2. Transfection with 20 nM ORAI2 siRNA reduced ORAI2 expression by 74.7 ± 4.6%; however, a small nonspecific reduction in ORAI3 expression was also observed.

Western blotting was used to study the expression of ORAI1 at the protein level and to assess the level of protein knockdown after siRNA transfection. Protein data are restricted to ORAI1 due to lack of commercially available antibodies against other members of the ORAI family. Western blot analysis revealed a prominent band of 50 kD in size, which corresponds to the expected size of ORAI1. Other, less intense protein bands of different molecular weights appeared; the bands are likely to be a result of nonspecific/background binding as a result of using a polyclonal primary antibody. Cell lysates were collected from control cells and cells treated with 20 nM ORAI1 siRNA; cellular protein levels were estimated and equal amounts of protein were loaded; equal protein loading was checked by probing for smooth muscle α-actin expression. Figure 1B shows a Western blot showing ORAI1 and smooth muscle α-actin expression from both control and ORAI1 siRNA–treated cells. A significant reduction in band definition corresponding to ORAI1 protein is seen with the siRNA-treated sample compared with control sample.

Effects of ORAI1, 2, and 3 mRNA Knockdown on SOC Influx Assessed through Intracellular Ca2+ Measurements

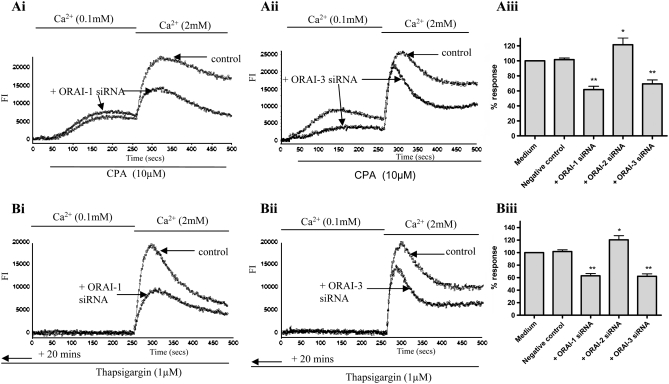

After successful knockdown of mRNA and (for ORAI1) protein, we then observed the functional effects on Ca2+ signals induced by store depletion. Changes in intracellular Ca2+ were measured using the Ca2+ detection dye Fluo-4AM (Molecular Probes). Store depletion was induced by either 10 μM CPA or 1 μM TG in a low extracellular Ca2+ (0.1 mM) buffer. After 4 minutes of stimulation with CPA or 24-minute incubation with TG, the addition of extracellular Ca2+ resulted in a large influx of Ca2+ over basal compared with cells not prestimulated with TG or CPA. Both TG- and CPA-induced Ca2+ influx was significantly decreased in cells transfected with siRNA targeted at ORAI1 (Figure 2) compared with cells transfected with an equal concentration of negative control siRNA. Transfection with ORAI2 siRNA had no inhibitory effects on Ca2+ influx. Transfection with ORAI3 siRNA also resulted in abnormal CPA-induced Ca2+ signals: both Ca2+ release from stores and Ca2+ influx from the extracellular space was decreased compared with control cells.

Figure 2.

Effects of ORAI1, 2, or 3 mRNA knockdown on cyclopiazonic acid (CPA)– and thapsigargin (TG)-induced Ca2+ influx. (Ai and Aii) Representative raw traces illustrating the CPA-induced changes in [Ca2+]i (presented as fluorescence intensity [FI]) in HASM cells transfected with ORAI1 siRNA (Ai) and ORAI3 siRNA (Aii), compared with HASM cells transfected with a negative control siRNA. CPA (10 μM) was added to the cells in the presence of low extracellular Ca2+ (0.1 mM) followed by the restoration of 2 mM Ca2+ as indicated. (Aiii) Summary of the data illustrated in (Ai) and (Aii) showing averaged changes in fluorescence after 2 mM Ca2+ restoration (averaged data from 8 separate experiments, at least 6 repeats within each experiment). (Bi and Bii) Representative raw traces illustrating the TG-induced changes in [Ca2+]i in HASM cells transfected with ORAI1 siRNA (Bi) and ORAI3 siRNA (Bii), compared with control cells. TG (1 μM) was added to the cells in the presence of low extracellular Ca2+ (0.1 mM) for 20 minutes before assay, followed by the restoration of 2 mM Ca2+ as indicated. (Biii) Summary of the data illustrated in (Bi) and (Bii) showing averaged changes in fluorescence after 2 mM Ca2+ restoration (averaged data from 4 separate experiments, at least 6 repeats within each experiment). Results are expressed as % changes ± SEM compared with control. Data are indicated as statistically significant with *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01.

Effects of ORAI1 Knockdown on Store-Operated Inward Currents Assessed by Whole Cell Patch Clamp

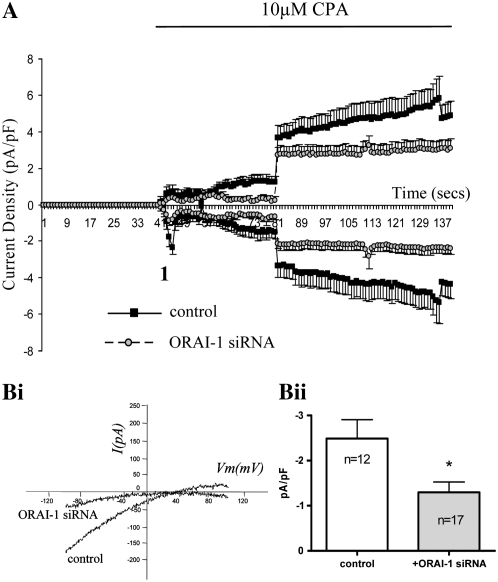

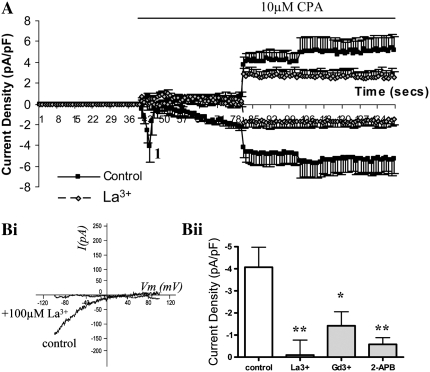

As a result of these Ca2+ data and given the level of knockdown and the specificity of the siRNA, we studied the effect of ORAI1 siRNA transfection on whole cell inward currents initiated by store depletion. Extracellular Ca2+ was omitted in these experiments because SOC currents are amplified under conditions where extracellular Ca2+ is absent and so are easier to study. In control cells under the experimental conditions described, application of CPA resulted in the activation of an inward current with two distinct components (Figure 3A). The first stage (depicted in Figure 3A as “1”) was a small, transient inward current followed by a further gradual development of current. The I-V profile at this point (“1”) is shown in Figure 3Bi and shows an inward current, with minimal outward current and a reversal potential of approximately +40 mV. The second current was larger and more sustained, with a more linear I-V relationship and marked outward current. In cells transfected with 20 nM siRNA targeted at ORAI1, activation of the initial current was inhibited. The second, larger, more sustained current was not greatly affected, taking into consideration the reduced baseline current before the activation of this secondary current. The characteristics of the initial current are similar to those previously observed for ICRAC. We therefore examined the effects of 100 μM La3+, 100 μM Gd3+, and 50 μM 2-aminoethoxydiphenylborane (2-APB) on the CPA-induced inward current. These inhibitors have been used in the past to inhibit SOC influx (18–20). At the concentrations stated, all inhibitors significantly suppressed the initial inward current (at point 1). Figure 4A shows a time course of current density showing control cells versus cells treated with 100 μM La3+. Figure 4Bi shows a representative I-V profile at point 1 on the time course and compares a control cell with an La3+-treated cell. The averaged inward current densities at point 1 (measured at −80 mV) are illustrated in Figure 4Bii, which shows control cells (n = 9) compared with cells treated with 100 μM La3+ (n = 9), 100 μM Gd3+ (n = 9), and 50 μM 2-APB (n = 9).

Figure 3.

Effects of ORAI1 knockdown on CPA-induced inward currents in single HASM cells assessed by whole cell patch clamp. (A) Time course of current density (inward currents measured at −80 mV, outward current measured at +80 mV); each point represents mean data ± SEM of all cells in each group; control cells treated with negative control siRNA (n = 12), ORAI1 suppressed cells (n = 17). (Bi) Representative current–voltage (I-V) relationships at point 1 from the time course. (Bii) Bar chart illustrating CPA-sensitive inward current density at point 1 (measured at −80 mV) in cells transfected with negative control or ORAI1 siRNA. Data are indicated as statistically significant with *P < 0.05.

Figure 4.

Inhibitory effects of 100 μM La3+, 100 μM Gd3+, and 50 μM 2-aminoethoxydiphenylborane (2-APB) on CPA-induced inward currents in single HASM cells assessed by whole cell patch clamp. (A) Time course of current density (inward currents measured at −80 mV, outward current measured at +80 mV) showing control cells versus cells treated with 100 μM La3+, each point represents mean data ± SEM of all cells in each group; control cells (n = 9), La3+-treated cells (n = 9). (Bi) Representative current–voltage (I-V) relationships at point 1 from the time course. (Bii) A bar chart illustrating CPA-sensitive inward current density at point 1 (measured at −80 mV) of control cells compared with cells treated with 100 μM La3+, 100 μM Gd3+, and 50 μM 2-APB. Data are indicated as statistically significant with *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

Understanding the mechanisms underlying activation of ASM contraction is of fundamental importance to asthma. Although it has been clear for many years that Ca2+ plays a key role in the contractile response, the mechanisms underlying control of Ca2+ homeostasis have been uncertain. The concept of Ca2+ influx mediated by a depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores was first introduced over 20 years ago (21). Over the last few decades, many mechanisms of communication between intracellular stores and plasma membrane ion channels have been proposed, including the release of diffusional messengers and vesicle fusion (reviewed in Reference 22), all of which have remained controversial. Recently, there has been interest in members of the STIM and ORAI family of proteins and their roles in SOC influx. Using an RNA interference approach, we demonstrated a role for STIM1 in the activation of SOC influx in primary HASM cells (14). We now report expression and studies on the potential roles for the three known human ORAI homologs (ORAI1, 2, and 3) in the activation of SOC influx in HASM cells.

All three ORAI homologs were found to be expressed in the primary airway myocytes. Successful knockdown of mRNA of all three homologs was achieved through siRNA transfection, and the level of knockdown was measured through quantitative reverse transcriptase (RT)–PCR. Knockdown of ORAI1 protein was achieved and visualized through Western blotting.

After successful knockdown of ORAI1 mRNA and protein, the effects of knockdown on store-mediated Ca2+ influx were then investigated. Both CPA- and TG-mediated Ca2+ influx was greatly reduced in the ORAI1 siRNA–transfected cells compared with the negative control–transfected cells. Knockdown of ORAI2 mRNA had no inhibitory effects on SOC influx in these cells; if anything, a slight enhancement of Ca2+ influx was observed. These data could suggest a role for ORAI2 in regulation of Ca2+ influx but should be interpreted with caution as some off-target effects were seen with this siRNA (unlike the other siRNAs used), including a small upregulation of STIM1 expression (data not shown). The cells transfected with siRNA targeted at ORAI3 also displayed abnormal CPA-mediated Ca2+ signals. Both Ca2+ release from stores and Ca2+ influx were reduced in the ORAI3 knockdown cells. These novel data suggest that cells with reduced ORAI3 expression have a lower Ca2+ store content—that is, ORAI3 may function to regulate basal Ca2+ levels or ORAI3 may play a role in Ca2+ release from stores.

As a result of the data obtained on Ca2+ influx and given the level of knockdown and the specificity of the siRNA species used, we next investigated the effect of ORAI1 siRNA transfection on whole cell inward currents initiated by store depletion. Extracellular Ca2+ was omitted in these experiments because SOC currents are amplified under conditions where extracellular Ca2+ is absent and so are easier to study. In control cells under the conditions described, application of CPA resulted in the activation of an inward current with two separate components. The first smaller, transient inward current was inhibited in the ORAI1 siRNA–transfected cells. Taking into consideration the reduced baseline current in the ORAI1-transfected cells, the activation of the second current was similar to that of control cells. Various known inhibitors of SOC influx, including 2-APB, La3+, and Gd3+, have also inhibited these currents (see Figure 4). The I-V profile of the initial current demonstrates characteristics typical of ICRAC (i.e., very positive reversal potential with limited outward rectification), whereas the secondary current shows similarities to previously observed ISOC currents responsible for capacitative store filling in human bronchial smooth muscle cells (2). These data demonstrating that the initial (ICRAC-like) current was inhibited by knockdown of ORAI1 could potentially be explained in two ways: that ICRAC is present in ASM or that ORAI1 contributes to other ISOC currents in these cells. Both of these possibilities are novel to previous concepts of ASM function, although some relevant data are emerging in other cell types.

Until recently, all of the studies investigating ORAI have focused on its involvement in the activation of the specific SOC subtype ICRAC. Mutations in ORAI1 result in significant changes to the electrophysiologic properties of ICRAC, rendering the current less Ca2+ selective with outward rectification (23). Such studies have provided evidence for the theory that ORAI1 forms the pore-forming subunits of the CRAC channel. However, there is some evidence that ORAI1 and STIM1 can contribute to function of other SOC channels (24). For example, ORAI1 has been reported to interact with Transient Receptor Potential Classical (TRPC)1 and forms a ternary complex together with STIM1 in the plasma membrane (25). Both STIM1 and ORAI1 are believed to contribute to the SOC function of TRPC1. Knockdown of either ORAI1 or STIM1 inhibits TRPC1 mediated ISOC in human salivary gland cells (25). It may be that the function of other TRPC channels is also mediated by the STIM and ORAI proteins given that ORAI1 interacts with TRPC3 and TRPC6, and there is suggestive evidence that ORAI1 may function to regulate these channels (26).

It is well established that TRPC channels assemble into homo- or heterotetramers with other TRPC subunits (27). It is possible that different TRPC/STIM/ORAI subunits interact to form different SOC channels with different electrophysiology and pharmacologic properties in ASM and that these complexes underlie the different Ca2+ influx pathways present in this cell type. Our group has previously found expression of a range of TRPC homologs in HASM and lung tissue including TRPC1, 3, 4, and 6 (28).

In summary, the data presented here clearly show a role for ORAI1 and, potentially, ORAI3 in SOC signals in ASM cells. It is likely that the role of ORAI and STIM homologs in SOC activation also extends to other smooth muscle cell types.

S.E.P. is in receipt of a Medical Research Council–funded scholarship.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue's table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI:10.1165/rcmb.2007-0395OC on January 31, 2008

Conflict of Interest Statement: None of the authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Hall IP. Second messengers, ion channels and pharmacology of airway smooth muscle. Eur Respir J 2000;15:1120–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sweeney M, McDaniel SS, Platoshyn O, Zhang S, Yu Y, Lapp BR, Zhao Y, Thistlethwaite PA, Yuan JX. Role of capacitative Ca2+ entry in bronchial contraction and remodeling. J Appl Physiol 2002;92:1594–1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leung FP, Yung LM, Yao X, Laher I, Huang Y. Store-operated calcium entry in vascular smooth muscle. Br J Pharmacol 2008;153:846–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feske S, Gwack Y, Prakriya M, Srikanth S, Puppel SH, Tanasa B, Hogan PG, Lewis RS, Daly M, Rao A. A mutation in Orai1 causes immune deficiency by abrogating CRAC channel function. Nature 2006;441:179–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang SL, Yeromin AV, Zhang XH, Yu Y, Safrina O, Penna A, Roos J, Stauderman KA, Cahalan MD. Genome-wide RNAi screen of Ca(2+) influx identifies genes that regulate Ca(2+) release-activated Ca(2+) channel activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006;103:9357–9362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roos J, DiGregorio PJ, Yeromin AV, Ohlsen K, Lioudyno M, Zhang S, Safrina O, Kozak JA, Wagner SL, Cahalan MD, et al. STIM1, an essential and conserved component of store-operated Ca2+ channel function. J Cell Biol 2005;169:435–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liou J, Kim ML, Heo WD, Jones JT, Myers JW, Ferrell JE Jr, Meyer T. STIM is a Ca2+ sensor essential for Ca2+-store-depletion-triggered Ca2+ influx. Curr Biol 2005;15:1235–1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manji SS, Parker NJ, Williams RT, van Stekelenburg L, Pearson RB, Dziadek M, Smith PJ. STIM1: a novel phosphoprotein located at the cell surface. Biochim Biophys Acta 2000;1481:147–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang SL, Yu Y, Roos J, Kozak JA, Deerinck TJ, Ellisman MH, Stauderman KA, Cahalan MD. STIM1 is a Ca2+ sensor that activates CRAC channels and migrates from the Ca2+ store to the plasma membrane. Nature 2005;437:902–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vig M, Peinelt C, Beck A, Koomoa DL, Rabah D, Koblan-Huberson M, Kraft S, Turner H, Fleig A, Penner R, et al. CRACM1 is a plasma membrane protein essential for store-operated Ca2+ entry. Science 2006;312:1220–1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soboloff J, Spassova MA, Tang XD, Hewavitharana T, Xu W, Gill DL. Orai1 and STIM reconstitute store-operated calcium channel function. J Biol Chem 2006;281:20661–20665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mercer JC, Dehaven WI, Smyth JT, Wedel B, Boyles RR, Bird GS, Putney JW Jr. Large store-operated calcium selective currents due to co-expression of Orai1 or Orai2 with the intracellular calcium sensor, Stim1. J Biol Chem 2006;281:24979–24990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peinelt C, Vig M, Koomoa DL, Beck A, Nadler MJ, Koblan-Huberson M, Lis A, Fleig A, Penner R, Kinet JP. Amplification of CRAC current by STIM1 and CRACM1 (Orai1). Nat Cell Biol 2006;8:771–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peel SE, Liu B, Hall IP. A key role for STIM1 in store operated calcium channel activation in airway smooth muscle. Respir Res 2006;7:119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daykin K, Widdop S, Hall IP. Control of histamine induced inositol phospholipid hydrolysis in cultured human tracheal smooth muscle cells. Eur J Pharmacol 1993;246:135–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rozen S, Skaletsky H. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods Mol Biol 2000;132:365–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001;25:402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bootman MD, Collins TJ, Mackenzie L, Roderick HL, Berridge MJ, Peppiatt CM. 2-Aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB) is a reliable blocker of store-operated Ca2+ entry but an inconsistent inhibitor of InsP3-induced Ca2+ release. FASEB J 2002;16:1145–1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Broad LM, Cannon TR, Taylor CW. A non-capacitative pathway activated by arachidonic acid is the major Ca2+ entry mechanism in rat A7r5 smooth muscle cells stimulated with low concentrations of vasopressin. J Physiol 1999;517:121–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luo D, Broad LM, Bird GS, Putney JW Jr. Signaling pathways underlying muscarinic receptor-induced [Ca2+]i oscillations in HEK293 cells. J Biol Chem 2001;276:5613–5621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Putney JW Jr. A model for receptor-regulated calcium entry. Cell Calcium 1986;7:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clapham DE. TRP channels as cellular sensors. Nature 2003;426:517–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vig M, Beck A, Billingsley JM, Lis A, Parvez S, Peinelt C, Koomoa DL, Soboloff J, Gill DL, Fleig A, et al. CRACM1 multimers form the ion-selective pore of the CRAC channel. Curr Biol 2006;16:2073–2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ambudkar IS, Ong HL, Liu X, Bandyopadhyay B, Cheng KT. TRPC1: the link between functionally distinct store-operated calcium channels. Cell Calcium 2007;42:213–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ong HL, Cheng KT, Liu X, Bandyopadhyay BC, Paria BC, Soboloff J, Pani B, Gwack Y, Srikanth S, Singh BB, et al. Dynamic assembly of TRPC1-STIM1-Orai1 ternary complex is involved in store-operated calcium influx: evidence for similarities in store-operated and calcium release-activated calcium channel components. J Biol Chem 2007;282:9105–9116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liao Y, Erxleben C, Yildirim E, Abramowitz J, Armstrong DL, Birnbaumer L. Orai proteins interact with TRPC channels and confer responsiveness to store depletion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007;104:4682–4687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hofmann T, Schaefer M, Schultz G, Gudermann T. Subunit composition of mammalian transient receptor potential channels in living cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2002;99:7461–7466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Corteling RL, Li S, Giddings J, Westwick J, Poll C, Hall IP. Expression of transient receptor potential C6 and related transient receptor potential family members in human airway smooth muscle and lung tissue. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2004;30:145–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]