Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is the fourth leading cause of death worldwide and is a progressive and irreversible disorder. Cigarette smoking is associated with 80–90% of COPD cases; however, the genes involved in COPD-associated emphysema and chronic inflammation are poorly understood. It was recently demonstrated that early growth response gene 1 (Egr-1) is significantly upregulated in the lungs of smokers with COPD (Ning W and coworkers, Proc Natl Acad Sci 2004;101:14895–14900). We hypothesized that Egr-1 is activated in pulmonary epithelial cells during exposure to cigarette smoke extract (CSE). Using immunohistochemistry, we demonstrated that pulmonary adenocarcinoma cells (A-549) and primary epithelial cells lacking basal Egr-1 markedly induce Egr-1 expression after CSE exposure. To evaluate Egr-1–specific effects, we used antisense (αS) oligodeoxynucleotides (ODN) to knock down Egr-1 expression. Incorporation of Egr-1 αS ODN significantly decreased CSE-induced Egr-1 mRNA and protein, while sense ODN had no effect. Via Egr-1–mediated mechanisms, IL-1β and TNF-α were significantly upregulated in pulmonary epithelial cells exposed to CSE or transfected with Egr-1. To investigate the relationship between Egr-1 induction by smoking and susceptibility to emphysema, we determined Egr-1 expression in strains of mice with different susceptibilities for the development of smoking-induced emphysema. Egr-1 was markedly increased in the lungs of emphysema-susceptible AKR/J mice chronically exposed to cigarette smoke, but only minimally increased in resistant NZWLac/J mice. In conclusion, Egr-1 is induced by cigarette smoke and functions in proinflammatory mechanisms that likely contribute to the development of COPD in the lungs of smokers.

Keywords: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Egr-1, gene expression, inflammation, pulmonary

The highly progressive and irreversible disorder known as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is functionally characterized by excessive airway obstruction. As contributors to COPD, emphysema and chronic bronchitis are two chronic lung diseases that cause significant morbidity, mortality, and health care expenditure (1, 2). Cigarette smoke exposure is acknowledged as a key risk factor in the development of COPD and is identified as the primary cause of 80–90% of all COPD cases in the United States (3). Because only 15–20% of heavy smokers develop clinically significant airway obstruction leading to COPD, genetic susceptibility must also be considered to understand the progression of the disease (4). The genes that link cigarette smoking and COPD susceptibility, however, remain poorly understood.

Protein products induced by differentially expressed genes likely exert both activating and inhibiting effects on mechanisms of COPD-associated airway disease, emphysema, and the resulting airflow obstruction. Therefore, the identification and functional characterization of such genes will assist in defining mechanisms of disease progression at the biochemical level and suggest potential sites for therapeutic intervention. Compared with at-risk smokers, smokers diagnosed with moderate COPD have altered expression of several genes including transcription factors (Egr-1 and Fos) and growth factors and associated proteins (CTGF, CYR61, CX3CL1, TGFβ1, and PDGFRα) (5). These and other gene products likely function to stimulate the recruitment of inflammatory cells, cell death, and elevated protease levels observed after prolonged cigarette smoke exposure (6–10).

Egr-1 (early growth response gene 1) is a zinc finger–containing, hypoxia-inducible transcription factor highly expressed in the lungs of smokers with COPD (5). Egr-1 binds the GC-rich sequence GCG(G/T)GGGCG, which often overlaps the DNA binding sequence of Sp1. Competition between Sp1 and Egr-1 leads to either activation or repression of common target genes (11, 12). As a crucial regulator of cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival, Egr-1 is induced by many stimuli ranging from growth factors and cytokines to stress signals such as radiation, exposure to apoptosis-promoting factors, injury, and stretch (11, 13, 14). Furthermore, depending on the stimulus and cell type, various signal transduction pathways induce Egr-1 expression, including pathways mediated by the MAP-kinases ERK1/2, protein kinase C-β (PKC-β), Rho GTPase, or p38/c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) (15). Although research aimed at understanding these signal transduction pathways are progressing, studies ascribing association with Egr-1 in cigarette smoke–mediated COPD are lacking.

In this study, we used Type II pneumocyte-like human pulmonary adenocarcinoma cells (A-549) and primary pulmonary small airway epithelial cells (SAEC) to investigate the role of Egr-1 during cigarette smoke–induced lung inflammation. Our results show that Egr-1 protein is induced in A-549 cells and SAECs after exposure to cigarette smoke extract (CSE). We also demonstrate that AKR/J mice, a strain of mice highly susceptible to cigarette smoke–induced emphysema (16), have significantly upregulated Egr-1 expression after exposure to cigarette smoke for 6 mo. In comparison, a resistant strain, NZWLac/J, had minimal pulmonary Egr-1 expression after exposure to identical conditions. Through the use of Egr-1 αS ODN, we demonstrate that the proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β and TNF-α are induced by CSE in vitro via an Egr-1–mediated mechanism. Collectively, these data offer intriguing insights into potential mechanisms whereby exposure to cigarette smoke induces the upregulation of Egr-1 in luminal epithelial cells. Elevated cytokine secretion induced by Egr-1 may activate downstream effects, including the recruitment of inflammatory cells, thus contributing to the development of COPD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies and Immunohistochemistry

A rabbit Egr-1 polyclonal antibody (sc-110; Santa Cruz Biotech, Santa Cruz, CA) was raised against a peptide that recognizes the C-terminus and was used at a dilution of 1:200. Cells were fixed by incubation in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min. Immunohistochemical staining for Egr-1 was performed using standard techniques as previously outlined (17). Control cultures were incubated in serum alone.

ODNs and CSE

Egr-1 sense (5′-AGT GTG CCC CTG CAC CCC GC-3′) and αS ODN (5′-GCG GGG TGC AGG GGC ACA CT-3′) (18) were synthesized by Stratagene (La Jolla, CA). CSE was generated as previously described with slight modifications (19). Briefly, two 2RF4 research cigarettes (University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY) were continuously smoked with a vacuum pump into 20 ml of DMEM or Small Airway Epithelial Cell Basal Medium (SAGM; Cambrex, Walkersville, MD). This smoke-bubbled medium was passed through a 0.22-μm filter (Pall Corp., Ann Arbor, MI) to remove large particles and the resulting medium was defined as 100% CSE. The total particulate matter content of 2RF4 cigarettes is 11.7 mg/cigarette, tar is 9.7 mg/cigarette, and nicotine is 0.85 mg/cigarette. Dilutions were made using DMEM or SAGM.

Cell Culture and Transfection

Human type II–like pulmonary adenocarcinoma cells (A-549) were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS, L-glutamine, and antibiotics. SAECs were maintained in SAGM supplemented according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were split into 6-well dishes and grown to 40–50% confluence. Cultures were exposed to media supplemented with CSE (25% or 50% CSE) or media alone for 1–4 h. Egr-1 knock-down experiments involved transfection of cells with Egr-1 sense or αS ODN (10 μM) with FuGENE-6 reagent (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) as previously outlined (20). Where noted, cells were allowed to grow for 12 h before CSE exposure. At the termination of the experiment, cells were immediately fixed for immunohistochemistry, and RNA was isolated for assessment by RT-PCR or lysed and subjected to Western blot analysis.

RNA Isolation and RT-PCR Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from cells grown in culture by using the Absolutely RNA RT-PCR Miniprep Kit (Stratagene). Reverse transcription of total mRNA and PCR conditions were as previously described (17). Gene expression was assessed in three replicate pools, and representative data are shown.

Protein Analysis

Whole cell lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis with a rabbit polyclonal Egr-1 antibody (sc-110; Santa Cruz). Briefly, equal amounts of total protein were analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), blocked with 5% evaporated milk, and exposed to the primary antibody diluted at 1:200 at 4°C overnight. Exposure to horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies was followed by development with ECL (Amersham Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, UK). Images presented are representative.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

After CSE exposure, cell culture medium was immediately analyzed for the presence of secreted IL-1β and TNF-α. Cytokine levels were assessed by using the human IL-1β and TNF-α enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) Kits (Antigenix America Inc., Huntington Station, NY) and by following the manufacturer's instructions.

Mouse Lung Samples

Lung tissue from two strains of mice (AKR/J and NZWLac/J) exposed to cigarette smoke or normal air for 6 mo was examined (16). Briefly, male mice were exposed to cigarette smoke or room air using a standard smoking apparatus (Cigarette Laboratory at the Tobacco and Health Research Institute, University of Kentucky) for 6 mo (age 3–9 mo). Mice were subjected to the smoke of two standard research nonfiltered cigarettes (2R1) per day, for 5 d/wk. Animals were killed by exsanguination, and lungs were inflated with optimal cutting temperature fluid then flash frozen in isopentane and liquid nitrogen. Five-micrometer sections were cut, fixed, and immunostained for the presence of Egr-1 using the rabbit polyclonal antibody previously mentioned (sc-110; Santa Cruz).

Data Analysis

Band densities were quantified using NIH ImageJ software (version 1.34; NIH, Bethesda, MD). Data are identified as means ± SE. Statistical significance was determined using the Student t test. All experiments were performed in triplicate, and representative results are shown.

RESULTS

Exposure to CSE Induces Egr-1 Expression

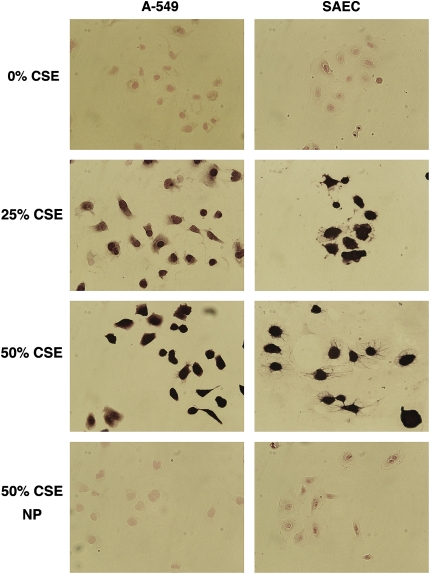

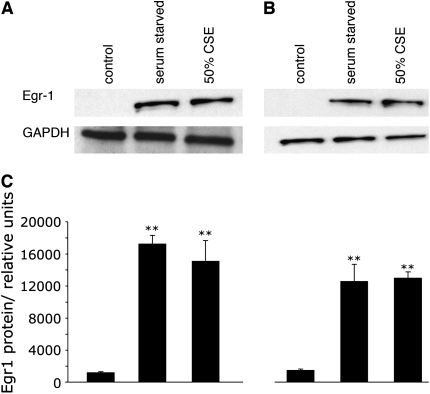

To investigate whether cigarette smoke extract (CSE) induces Egr-1, we performed immunohistochemical staining on A-549 cells and SAECs grown in media supplemented with various concentrations of CSE. Cells at 40–50% confluence were exposed for 1, 2, or 4 h to 0, 25, or 50% CSE and immediately fixed. We observed that cells had minimal expression Egr-1 when grown in medium without CSE (Figure 1). Egr-1 was markedly induced after exposure to 25% or 50% CSE (Figure 1) for 2 h. In the absence of Egr-1 primary antibodies, Egr-1 was not detected after exposure to 50% CSE (Figure 1). These experiments were completed after optimizing CSE dose levels and duration of exposure. Via trypan blue exclusion, no significant differences in A-549 cell viability were observed after exposure to 0% (99.0 ± 0.5), 25% (96.7 ± 2.1), or 50% (94.2 ± 3.6) CSE. When compared with 0% CSE (97.8 ± 1.7), primary SAEC viability was lower when CSE exposure was 25% (89.6 ± 2.2) and 50% (82.0 ± 5.9), suggesting that primary epithelial cells are more sensitive to the effects of CSE. Egr-1 was induced in both cell types after exposure for 1 h, and viability was not significantly decreased after 2 h (not shown). These findings were further investigated by Western blotting performed on cell lysates obtained from cells grown under similar conditions. Egr-1 protein was not observed in A-549 cells or SAECs grown in media alone, and as expected Egr-1 was significantly increased after CSE exposure and serum starvation (Figure 2). These data demonstrate that exposure to CSE induces Egr-1 expression in pulmonary epithelial cells in vitro.

Figure 1.

Exposure of A-549 cells and SAECs to CSE upregulates Egr-1 expression. Cells at 40–50% confluence were incubated in media alone, 25% CSE, or 50% CSE for 2 h, immediately fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and immunostained for Egr-1 protein expression. Egr-1 expression was not detected in control cells grown in medium alone. Egr-1 was markedly induced in cells exposed to 25% and 50% CSE. Experiments without primary antibodies revealed no immunoreactivity after exposure to 50% CSE. Images are at ×80 magnification.

Figure 2.

CSE induces Egr-1 expression in human pulmonary adenocarcinoma cells (A-549) and Primary SAECs. (A and B) Representative Western blot analysis reveals no Egr-1 expression in cells grown in medium alone (control). Significant upregulation of Egr-1 was observed in serum-starved cells and in cells exposed to 50% CSE for 2 h. (C) Relative densitometry was quantified by using NIH Image-J software. Significant differences in Egr-1 protein expression as compared with control are noted at P ⩽ 0.01 (**).

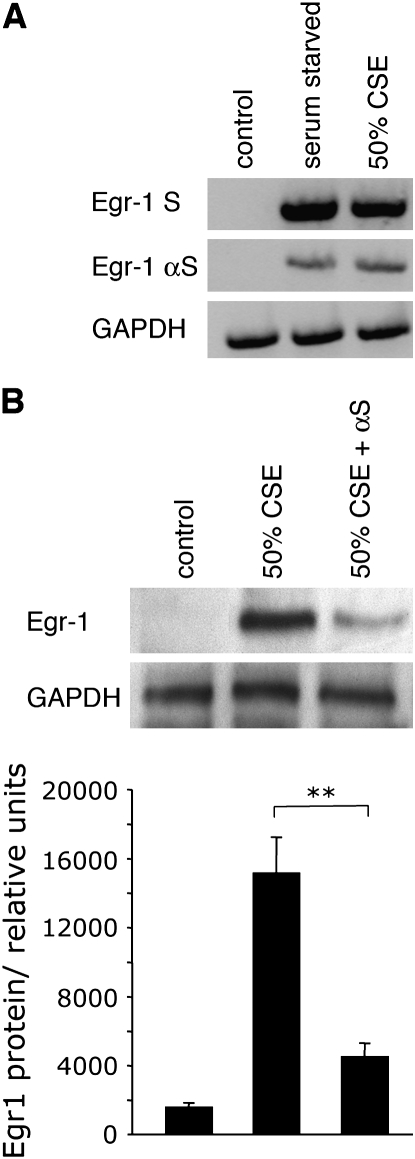

Egr-1 αS ODN Inhibit Egr-1 mRNA and Protein Expression in A-549 Cells Exposed to CSE

CSE-induced upregulation of Egr-1 expression was further assessed by employing Egr-1–specific αS ODN. A-549 cells were transfected with sense or αS ODN (10 μM), allowed to grow for 12 h, then exposed to CSE. Similar to induction during serum starvation, CSE exposure resulted in high levels of Egr-1 mRNA expression (Figure 3A). CSE-induced upregulation of Egr-1 was significantly diminished by the incorporation of Egr-1 αS ODN. Assessment by Western blotting also demonstrated that CSE-mediated Egr-1 activation was significantly reduced by exposure to Egr-1 αS ODN (Figure 3B). Sense ODN had no effect on Egr-1 protein expression (not shown). From the data presented, it is clear that pulmonary epithelial cells exposed to CSE upregulate Egr-1 expression.

Figure 3.

Egr-1 αS ODNs inhibit Egr-1 mRNA and protein expression. (A) A-549 cells were transfected with Egr-1 sense (S) or antisense (αS) oligonucleotides (10 μM) and serum starved or exposed to CSE 12 h after transfection for 2 h. Total RNA was isolated, 1.0 μg was reverse transcribed, and the resulting cDNA was subjected to PCR analysis. αS oligonucleotides significantly decreased Egr-1 mRNA expression. (B) Cells manipulated as outlined above were lysed and subjected to Western blot analysis. Significant αS ODN-mediated decreases in Egr-1 expression were detected after serum starvation or exposure to CSE. Relative densitometry was quantified by using NIH Image-J software. Significant differences in Egr-1 protein expression are noted at P ⩽ 0.05 (*) and P ⩽ 0.01 (**).

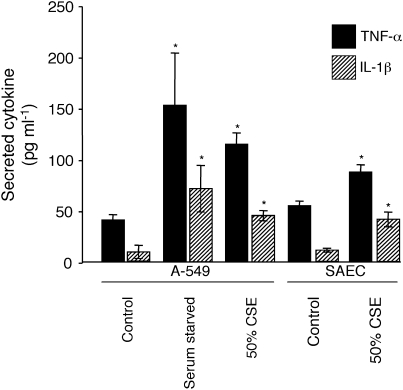

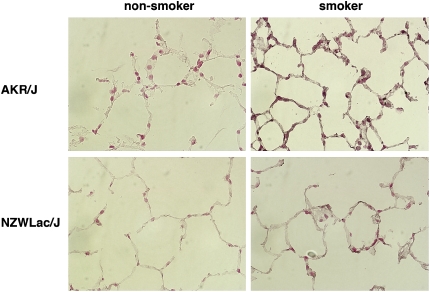

CSE Exposure Induces Proinflammatory Cytokine Expression

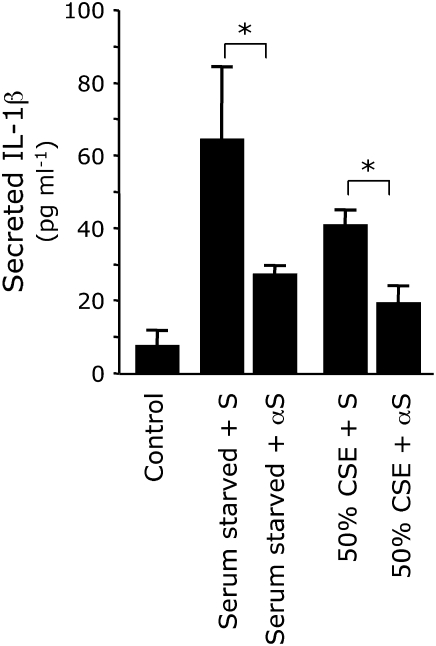

We next investigated downstream targets in potential mechanisms of CSE-mediated cellular responses. Inflammation generally follows homeostatic perturbation such as exposure to foreign substances or removal of nutrients; therefore, we assessed the expression of proinflammatory cytokines after CSE exposure. Removal of serum markedly induced the secretion of IL-1β and TNF-α in A-549 cells (Figure 4). Although not to the levels observed after serum starvation, exposure to 50% CSE also significantly increased cytokine secretion (Figure 4). Similar CSE-induced increases in cytokine secretion were observed in SAECs.

Figure 4.

CSE exposure induces proinflammatory cytokine secretion. A-549 cells were serum starved or exposed to 50% CSE for 2 h and medium was immediately assayed for secreted IL-1β (shaded bars) and TNF-α (solid bars) by ELISA. Compared with basal levels observed from cells grown in DMEM-10% FCS (control), cells exposed to media lacking serum or 50% CSE had significantly elevated levels of secreted IL-1β and TNF-α. SAECs exposed to 50% CSE also induced cytokine secretion. Data presented are from two experiments, each performed in triplicate. *P ⩽ 0.05.

Egr-1 αS ODN Inhibit CSE-Induced Proinflammatory Cytokine Expression

While incapable of blocking Egr-1 completely, we demonstrate that αS ODN are effective in significantly decreasing Egr-1 expression (Figure 3). Knocking down Egr-1 expression in A-549 cells resulted in significant decreases in the levels of secreted IL-1β in experiments involving serum starvation and exposure to CSE (Figure 5). αS-mediated inhibition of Egr-1 was less effective in blocking TNF-α secretion by A-549 cells (Figure 6). While αS ODN significantly decreased TNF-α secretion by cells exposed to 50% CSE, inhibition of Egr-1 did not significantly lower TNF-α secretion in serum-starved cells (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Egr-1 αS ODNs inhibit CSE-induced IL-1β secretion. A-549 cells were transfected with Egr-1 sense (S) or antisense (αS) oligonucleotides (10 μM) and serum starved or exposed to CSE 12 h after transfection for 2 h. Medium was isolated and subjected to ELISA. Secreted IL-1β was significantly decreased by Egr-1 αS oligonucleotides after serum starvation or CSE exposure. Data presented are from two experiments, each performed in triplicate. *P ⩽ 0.05.

Figure 6.

Egr-1 αS ODNs inhibit CSE-induced TNF-α secretion. A-549 cells were transfected with Egr-1 sense (S) or antisense (αS) oligonucleotides (10 μM) and serum starved or exposed to CSE 12 h after transfection for 2 h. Medium was isolated and subjected to ELISA. Secreted TNF-α was not significantly decreased by Egr-1 αS ODNs after serum starvation. TNF-α secretion was significantly inhibited by Egr-1 αS ODNs in cells exposed to 50% CSE. Data presented are from two experiments, each performed in triplicate. *P ⩽ 0.05.

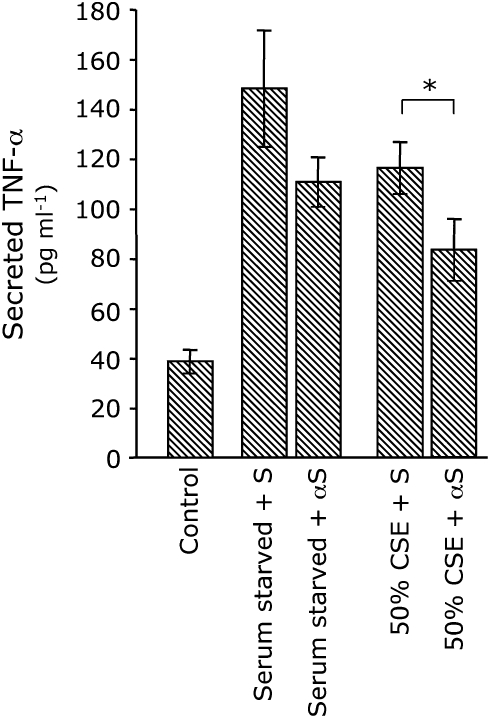

Exogenous Egr-1 Induces Proinflammatory Cytokine Expression

We previously demonstrated that Egr-1 is not detected in unstimulated A-549 cells, but is significantly induced after CSE exposure (Figure 3). Because cross talk between numerous mechanisms of proinflammatory cytokine activation after cigarette smoke exposure likely occurs, we investigated the role of Egr-1 in the absence of CSE. After transfection of Egr-1 (pCMV–Egr-1), secreted IL-1β was significantly elevated (Figure 7A). Significant increases in IL-1β secretion were observed in A-549 cells transfected with 200 and 400 ng of Egr-1; however, IL-1β secretion did not significantly increase in cells transfected with higher concentrations (Figure 7A). Significant increases in secreted TNF-α by A-549 cells were not observed until a high concentration (800 ng) of Egr-1 was transfected (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

Exogenous Egr-1 induces proinflammatory cytokine secretion. In the absence of CSE, A-549 cells were transfected with Egr-1 (pCMV-Egr-1), and secreted IL-1β or TNF-α in the medium was assessed by ELISA. While transfection experiments with 200–400 ng Egr-1 significantly induced IL-1β secretion, TNF-α secretion was significantly elevated only after 800 ng of Egr-1 was transfected. Data presented are from two experiments, each performed in triplicate. *P ⩽ 0.05.

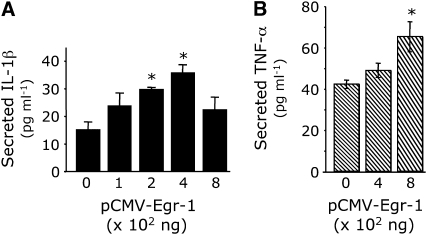

Egr-1 Is Induced in the Lungs of Mice Exposed to Cigarette Smoke In Vivo

AKR/J and NZWLac/J are two strains of mice with different genetic backgrounds. Previous research has shown that AKR/J mice exposed to cigarette smoke for 6 mo develop marked emphysema, whereas NZWLac/J mice do not (16). Compared with the less responsive NZWLac/J mice, AKR/J mice exposed to cigarette smoke have decreased alveolar elastance, elevated inflammatory cell infiltration, and significant increases in the expression of TNF-α, IL-12, IL-10, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β (16). Therefore, these strains of mice were exposed to cigarette smoke (smokers) or room air (nonsmokers) for 6 mo and pulmonary Egr-1 expression was assessed. Egr-1 was marginally detected by immunohistochemistry in pulmonary alveolar epithelial cells in the lungs of nonexposed mice (Figure 8). AKR/J mice exposed to cigarette smoke had markedly increased Egr-1 expression in respiratory epithelial cells in the peripheral lung; however, Egr-1 was only minimally induced in the lungs of emphysema-resistant NZWLac/J smoke-exposed mice.

Figure 8.

Egr-1 is induced in the lungs of mice exposed to cigarette smoke. Cigarette smoke–induced emphysema hypersensitive (AKR/J) and resistant (NZWLac/J) mice were maintained in environments either lacking (nonsmokers) or including cigarette smoke (smokers) for 6 mo. Immunohistochemistry reveals minimal Egr-1 expression in nonsmoker lungs of both strains; however Egr-1 expression was markedly increased in AKR/J smoker lungs. Egr-1 was minimally increased in the lungs of smoker NZWLac/J mice resistant to cigarette smoke–induced emphysema. Control sections incubated in serum alone had no immunoreactivity (not shown). Figures are at ×100 magnification.

DISCUSSION

The expression of the zinc finger transcription factor, Egr-1, was assessed in pulmonary epithelial cells exposed to CSE. While pathways potentially active in the pathogenesis of COPD have been shown to involve Egr-1, the direct role of Egr-1 in cells exposed to cigarette smoke, or the regulation of potential Egr-1–targeted responses, remained enigmatic. We demonstrate that Egr-1 mRNA and protein are markedly induced after exposure to CSE. The induction of Egr-1 protein was detected at levels similarly observed in cells stressed by serum starvation. Through the use of Egr-1 αS ODN, we show that the levels of secreted proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β and TNF-α) by cells exposed to CSE are significantly attenuated after direct inhibition of Egr-1. We also show that transfection of pulmonary epithelial cells with exogenous Egr-1 results in significantly elevated cytokine secretion.

Similar to the rapid induction of Egr-1 in A-549 cells and primary SAECs after exposure to CSE, increased Egr-1 has been observed in cells responding to acute injury or environmental manipulation (21–28). It is likely, however, that Egr-1 expression is prolonged in emphysema (29), which contributes to destructive pulmonary diseases such as COPD (5). Because COPD is a heterogeneous condition with variable morphologic and physiologic phenotypes, careful assessments of the level of airway obstruction, type of emphysema, and degree of inflammation are all necessary to characterize COPD in humans. It is therefore necessary to examine the expression and function of Egr-1 in the variable pulmonary complications resulting from chronic exposure to cigarette smoke.

Because much of the data presented here have been derived from experiments using A-549 cells, a pulmonary adenocarcinoma cell line functionally similar to type II pneumocytes (30) and primary SAECs, relevance to complex pulmonary responses affected by exposure to cigarette smoke at the organ level remains uncertain. Further analysis of Egr-1–mediated mechanisms of inflammation and emphysema in susceptible (AKR/J), resistant (NZWLac/J), and Egr-1–null mice chronically exposed to cigarette smoke are required. Only a few of the genes identified as being directly regulated by Egr-1 in vitro (22) have been confirmed in vivo. Study of the Egr-1 knockout mouse for example has only revealed that luteinizing hormone-β (31), apo A-1 (32), and tissue factor (33) are regulated by Egr-1. Although our current research demonstrates that Egr-1 is directly induced by cigarette smoke in vitro and in susceptible mouse strains in vivo, it is likely that a combination of factors function to induce downstream target genes in vivo.

Downstream targets of Egr-1 that function in the progression of pulmonary disease are incompletely understood. Zhu and colleagues show that matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are regulated by Egr-1 in lung fibroblasts (33), which may affect ECM turnover in the development of COPD-associated emphysema. Several proteolytic enzymes contribute to alveolar septal destruction that leads to COPD, but speculation remains as to the identification of all sources of these degrading enzymes. Our data demonstrate that epithelial cells may play an indirect role in the activation of proteolytic enzyme–containing inflammatory cells via Egr-1–dependent secretion of proinflammatory cytokines.

In addition to emphysema, cigarette smoke–induced chronic inflammation in pulmonary airways is also associated with the pathogenesis of COPD. As currently demonstrated, CSE upregulates the expression of IL-1β and TNF-α by pulmonary epithelial cells via Egr-1 activation. An initial review of the promoters of these cytokines revealed no direct Egr-1 response elements. Further investigation of these promoters is required to distinguish indirect transcriptional regulation by Egr-1 through the activation of additional transcription factors. Inflammation has been characterized as a condition that results from imbalances between oxidants and antioxidants or between proteases and antiproteases (34). While we have demonstrated direct regulation of inflammatory cytokine secretion by Egr-1, work is currently underway that focuses on potential mechanisms associated with Egr-1 that mediate cigarette smoke–induced inflammatory responses during oxidative stress.

Our research expands the understanding of Egr-1, a transcription factor that orchestrates cellular responses to several stimuli. Although under normal conditions Egr-1 is it not an essential transcription factor (35), its expression is induced by cigarette smoke and it leads to increased secretion of proinflammatory cytokines by pulmonary epithelial cells. Because serum starvation and exposure to CSE both result in the activation of Egr-1–mediated mechanisms of proinflammatory cytokine secretion, it is likely that several interacting factors target Egr-1 to induce phenotypic effects attributed to lung disease. This is especially true in the case of TNF-α, where CSE induced only a modest increase in the secretion of this potent cytokine, suggesting many potential mechanisms of regulation. Our work suggests an interesting mechanism mediated by Egr-1 in which pulmonary alveolar epithelial cells secrete IL-1β and TNF-α after exposure to cigarette smoke. Interestingly, both IL-1β and TNF-α can induce the expression of Egr-1 in pulmonary fibroblasts (29). Such increased Egr-1 expression in fibroblasts not directly exposed to cigarette smoke in the conducting and respiratory airways may then induce MMPs (33) and other genes that contribute to airway damage and inflammation associated with COPD. Therefore, effective inhibition of the nonessential transcription factor Egr-1 may significantly attenuate obstructive pulmonary remodeling, alveolar breakdown, and inflammation associated with the pathology of COPD.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Tapan Mukherjee for technical assistance.

This research was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health, HL72903 (J.R.H.) and HL07636 (P.R.R.).

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0428OC on April 6, 2006

Conflict of Interest Statement: None of the authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Voelkel NF, MacNee W. Chronic obstructive lung diseases. Hamilton, ON: B. C. Decker; 2002. pp. 90–113.

- 2.Petty TL. COPD in perspective. Chest 2002;121:116S–120S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sethi JM, Rochester CL. Smoking and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clin Chest Med 2000;21:67–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mayer AS, Newman LS. Genetic and environmental modulation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Physiol 2001;128:3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ning W, Li CJ, Kaminski N, Feghali-Bostwick CA, Alber SM, Di YP, Otterbein SL, Song R, Hayashi S, Zhou Z, et al. Comprehensive gene expression profiles reveal pathways related to the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004;101:14895–14900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carp H, Janoff A. Possible mechanisms of emphysema in smokers. In vitro suppression of serum elastase-inhibitory capacity by fresh cigarette smoke and its prevention by antioxidants. Am Rev Respir Dis 1978;118:617–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hautamaki RD, Kobayashi DK, Senior RM, Shapiro SD. Requirement for macrophage elastase for cigarette smoke-induced emphysema in mice. Science 1997;277:2002–2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuschner WG, D'Alessandro A, Wong H, Blanc PD. Dose-dependent cigarette smoking-related inflammatory responses in healthy adults. Eur Respir J 1996;9:1989–1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sopori M. Effects of cigarette smoke on the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol 2002;2:372–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wright JL, Churg A. Cigarette smoke causes physiologic and morphologic changes of emphysema in the guinea pig. Am Rev Respir Dis 1990;142:1422–1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu C, Rangnekar VM, Adamson E, Mercola D. Suppression of growth and transformation and induction of apoptosis by EGR-1. Cancer Gene Ther 1998;5:3–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beckmann AM, Wilce PA. Egr transcription factors in the nervous system. Neurochem Int 1997;31:477–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Donovan KJ, Tourtellotte WG, Millbrandt J, Baraban JM. The EGR family of transcription-regulatory factors: progress at the interface of molecular and systems neuroscience. Trends Neurosci 1999;22:167–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gashler A, Sukhatme VP. Early growth response protein 1 (Egr-1): prototype of a zinc-finger family of transcription factors. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol 1995;50:191–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baron V, Duss S, Rhim J, Mercola D. Antisense to the early growth response-1 gene (Egr-1) inhibits prostate tumor development in TRAMP mice. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2003;1002:197–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guerassimov A, Hoshino Y, Takubo Y, Turcotte A, Yamamoto M, Ghezzo H, Triantafillopoulos A, Whittaker K, Hoidal JR, Cosio MG. The development of emphysema in cigarette smoke-exposed mice is strain dependent. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004;170:974–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reynolds PR, Hoidal JR. Temporal-spatial expression and transcriptional regulation of alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor by thyroid transcription factor-1 and early growth response factor-1 during murine lung development. J Biol Chem 2005;280:32548–32554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Banks MF, Gerasimovskaya EV, Tucker DA, Frid MG, Carpenter TC, Stenmark KR. Egr-1 antisense oligonucleotides inhibit hypoxia-induced proliferation of pulmonary artery adventitial fibroblasts. J Appl Physiol 2005;98:732–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishii T, Matsuse T, Igarashi H, Masuda M, Teramoto S, Ouchi Y. Tobacco smoke reduces viability in human lung fibroblasts: protective effect of glutathione S-transferase P1. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2001;280:L1189–L1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reynolds PR, Mucenski ML, Le Cras TD, Nichols WC, Whitsett JA. Midkine is regulated by hypoxia and causes pulmonary vascular remodeling. J Biol Chem 2004;279:37124–37132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khachigian L, Lindner V, Williams A, Collins T. Egr-1-induced endothelial gene expression: a common theme in vascular injury. Science 1996;271:1427–1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khachigian L, Collins T. Inducible expression of Egr-1-dependent genes: a paradigm of transcriptional activation in vascular endothelium. Circ Res 1997;81:457–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yan S-F, Zou Y-S, Gao Y, Zhai C, Mackman N, Lee S, Milbrandt J, Pinsky D, Kisiel W, Stern D. Tissue factor transcription driven by Egr-1 is a critical mechanism of murine pulmonary fibrin deposition in hypoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998;95:8298–8303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yan S-F, Lu J, Zou Y-S, Soh-Won J, Cohen D, Buttrick P, Cooper D, Steinberg S, Mackman N, Pinsky D, et al. Hypoxia-associated induction of Early Growth Response-1 gene expression. J Biol Chem 1999;274: 15030–15040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bonventre J, Sukhatme V, Bamberger J, Ouellette A, Brown D. Localization of the protein product of the immediate early growth response gene, Egr-1, in the kidney after ischemia and reperfusion. Nat Med 1991;2:251–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brand T, Sharma H, Fleischmann K, Duncker D, McFalls E, Verdouw P, Schaper W. Proto-oncogene expression in porcine myocardium subjected to ischemia and reperfusion. Circ Res 1992;71:1351–1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cornelius A, Holmer E, Birnbaum D, Riegger G, Schunkert H. Expression of immediate early genes after cardioplegic arrest and reperfusion. Ann Thorac Surg 1997;63:1669–1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ouellette A, Malt R, Sukhatme V, Bonventre J. Expression of two “immediate early” genes, Egr-1 and c-fos, in response to renal ischemia and during compensatory renal hypertrophy in mice. J Clin Invest 1990;85:766–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang W, Yan SD, Zhu A, Zou YS, Williams M, Godman GC, Thomashow BM, Ginsburg ME, Stern DM, Yan SF. Expression of Egr-1 in late stage emphysema. Am J Pathol 2000;157:1311–1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith BT. Cell line A549: a model system for the study of alveolar type II cell function. Am Rev Respir Dis 1977;115:285–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee S, Sadovsky Y, Swirnoff A, Polish J, Goda PG, Milbrandt J. Luteinizing hormone deficiency and female infertility in mice lacking the transcription factor NGFI-A (Egr-1). Science 1996;273:1219–1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zaiou M, Azrolan N, Hayek T, Wang H, Wu L, Haghpassand M, Cizman B, Madaio M, Milbrandt J, Marsh J, et al. The full induction of human apoA-1 gene expression by experimental nephrotic syndrome in transgenic mice depends on cis-acting elements in the proximal 256 base-pair promoter region and the trans-acting factor Egr-1. J Clin Invest 1998;101:1699–1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu YK, Liu X, Ertl RF, Kohyama T, Wen FQ, Wang H, Spurzem JR, Romberger DJ, Rennard S. Retinoic acid attenuates cytokine-driven fibroblast degradation of extracellular matrix in three-dimensional culture. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2001;25:620–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.MacNee W. Oxidative stress and lung inflammation in airways disease. Eur J Pharmacol 2001;429:195–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Silverman ES, Collins T. Pathways of Egr-1-mediated gene transcription in vascular biology. Am J Pathol 1999;154:665–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]