Abstract

Analysis of naturally occurring mutations that cause seizures in rodents has advanced understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying epilepsy. Abnormalities of Ih and h channel expression have been found in many animal models of absence epilepsy. We characterized a novel spontaneous mutant mouse, apathetic (ap/ap), and identified the ap mutation as a 4 base pair insertion within the coding region of Hcn2, the gene encoding the h channel subunit 2 (HCN2). We demonstrated that Hcn2ap mRNA is reduced by 90% compared to wild type, and the predicted truncated HCN2ap protein is absent from the brain tissue of mice carrying the ap allele. ap/ap mice exhibited ataxia, generalized spike-wave absence seizures, and rare generalized tonic-clonic seizures. ap/+ mice had a normal gait, occasional absence seizures and an increased severity of chemoconvulsant-induced seizures. These findings help elucidate basic mechanisms of absence epilepsy and suggest HCN2 may be a target for therapeutic intervention.

Introduction

Absence epilepsy is a common generalized epilepsy syndrome of childhood and adolescence. Several familial generalized epilepsy syndromes have been mapped in humans, and in a majority of cases, the affected gene encodes a voltage- or ligand-gated ion channel (for review see; (Steinlein, 2004)). In addition to heritable generalized epilepsies in humans, many animal models of generalized epilepsy, including absence epilepsy, have been described. Similar to human cases, generalized epilepsy syndromes in animals (arising as either spontaneous mutations in inbred colonies (Noebels, 2006), or resulting from targeted gene deletions (Burgess, 2006)), have overwhelmingly involved genes encoding ion channels.

Of the spontaneous monogenic mouse epilepsy models, several of the implicated genes are also mutated in human epilepsy syndromes (Noebels, 2003). Mouse mutations lacking a currently appreciated human counterpart are also critical for epilepsy research as they may shed light on basic mechanisms of epileptic neuronal synchronization, offer opportunities to study genetic interactions in epilepsy, and point toward genes causing epilepsy in humans.

Here we report a novel spontaneous mouse mutation, which we have named apathetic (ap). Apathetic (ap/ap) mice are ataxic and exhibit brief behavioral arrests and tonic-clonic convulsions phenotypically resembling generalized absence and tonic-clonic convulsions, respectively. EEG studies reveal frequent generalized spike-wave seizures sensitive to ethosuximide, consistent with absence epilepsy. While otherwise appearing neurologically normal, a fraction of mice heterozygous for the ap allele also exhibited absence seizures, and ap/+ mice showed enhanced sensitivity to chemoconvulsive seizures. We positionally identified the mutation in the ap/ap mice as a 4 base pair insertion in the gene encoding the hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated (HCN) ion channel (h channel) subunit 2 (Hcn2). The ap mutation is predicted to introduce 41 novel amino acids and a novel stop codon that truncates the HCN2 protein within the cyclic nucleotide binding domain, but no truncated HCN2 protein was observed in mice harboring the ap allele. HCN2 was absent from the brain of ap/ap mice and reduced in ap/+ animals, but we observed no changes in other h channel subunits. Our studies add to the growing body of data implicating h channels in epilepsy, and suggest that the human HCN2 gene should be considered in future studies of familial epilepsy as well as a potential target for development of new therapeutics.

Materials and Methods

Mice

The apathetic (ap) mutation arose spontaneously in a colony of DW/Pas mice being studied for obesity/diabetes phenotypes by WKC and RLL in the vivarium at the Rockefeller University (Laboratory Animal Resource Center). Affected male and female ap mice were always born from unaffected mating pairs, and were observed approximately 25% of the time in litters with affected animals, suggesting autosomal recessive inheritance. A carrier female was outcrossed to a normal C57BLKS/J male to facilitate initial mapping. Pairs of male and female F1 mice were test crossed until obligate carriers were identified producing affected mice. After initial chromosomal localization, carrier DW/Pas females were crossed to CAST/Ei wild type (+/+) males to increase the number of polymorphic microsatellite markers available for fine mapping. Obligate F1 carriers were identified through test crosses and then used to generate affected F2 animals. Ap/ap mice were maintained in federally approved animal facilities at The Rockefeller University, Columbia University, and Northwestern University with 12L/12D cycle and ad libitum access to food and water. Animals were weaned at 21 days of age. All animal usage in these studies was approved by The Rockefeller University, Columbia University (IUCAC), and Northwestern University Animal Care and Use Committees (NUACUC).

Mapping the apathetic locus

Genome wide linkage analysis was performed using 12 affected F2 DW/Pas C57BLKS/J animals and 44 polymorphic MapPair markers (Research Genetics; Huntsville, AL) spaced at approximately 30 cM intervals across the genome. All mice were phenotyped by a single observer (WKC). Genomic DNA was extracted from spleens using proteinase K digestion and phenol chloroform extraction. Amplicons of polymorphous microsatellite markers were amplified by polymerase chain reaction and separated on a 5% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. After the ap locus was linked to mouse chromosome 10 at approximately 40.4 cM from the centromere, further fine mapping was performed in the affected F2 Dw/PAS × CAST/Ei with an additional 24 markers on chromosome 10 in a total of 473 F2 mice to define a minimal non-recombinant interval between D10Mit139/D10Mit260/D10Mit175 and D10Mit21/D10Mit23 containing the ap locus. A complete mouse BAC contig was built across the non-recombinant interval by screening the RTCO-23 C57BL/6J mouse BAC library (http://www.roswellpark.org/Research/Shared_Resources/Microarray_and_Genomics_Resource) for clones containing genes or DNA sequences in the non-recombinant interval. By comparing the sequences of the mouse BAC ends and genes contained within the mouse BACs to human sequence databases, we identified a human cosmid containing the gene BSG as well as the 5’ end of HCN2. We tested Hcn2 as a candidate gene, and the coding regions of Hcn2 were sequenced on genomic DNA by dideoxy sequencing on an ABI 377 according the manufacturer’s instructions in ap/ap and control mice.

Genotyping the Hcn2ap locus

Genomic DNA was purified from 1mm-length tip of mouse tails using Sigma REDExtractNAmp Tissue Kit (Sigma, MO) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The mutation in exon 6 of the Hcn2 gene containing nucleotide 1669 was amplified by PCR using 5’-primer; 5’-ATGGCTTTCTCCAGT-3’ and 3’-primer; 5’-CCCATGCTGGATGAAG-3’. Amplified PCR products were separated in 15% non-denaturing PAGE gels, and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. The PCR fragment generated by the wild type allele was 90 bp and by the ap allele was 94 bp.

Behavioral testing

Adult mice 8-16 weeks old were assessed with a simple neurological screen for motor and sensory responses (Paylor et al., 1998). In this screen, a mouse was weighed and measured, then placed into an empty cage and observed for 1 min. The presence of several behavioral responses was recorded (i.e., wild running, freezing, licking, jumping, sniffing, rearing, movement throughout the cage, and defecation). Postural reflexes were then evaluated by determining if the mouse would splay its limbs when in a cage that is quickly lowered and moved from side to side. The righting reflex, whisker touch response, eye blink, and ear twitch were then evaluated. A platform test was conducted by placing the animal in the center of a platform (20 cm), then recording the latency to move to the edge, as well as the number of times the mouse reaches its head over the edge (nose pokes). Two-way (genotype × gender) analyses of variance (ANOVA) were used to analyze the platform test data. Nonparametric statistical tests were used to analyze the remaining data. The rotarod test was performed by placing a mouse on a rotating drum (Ugo Basile) and measuring the time each animal was able to maintain its balance on the rod. The speed of the rotarod accelerated from 4 to 40 rpm over a 10-min period. Mice were given four trials with a 30- to 60-min intertrial rest interval. Rotarod data were analyzed with a three-way (genotype × gender × trial) ANOVA with repeated measures. Significant interactions were subsequently analyzed by use of simple effects tests.

Animal surgery and EEG recording

At 3 months of age, ap/ap and +/+ mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (80 mg/kg) and xylazine (9 mg/kg). An incision was made on the scalp to expose the skull. Four holes were drilled through the skull to dura, two placed 1mm anterior to the bregma and two placed 7mm anterior to the bregma, each being 1.5 mm lateral to the central sulcus. These holes accommodated a prefabricated mouse headmount (Pinnacle Technologies) which was fastened to the skull with stainless steel screws (Small Parts, Miami Lakes, FL). The headstage was secured to the skull using dental acrylic. Loose skin was sutured around the implant and at least 7 days were allowed before beginning data collection. Following the recovery period, mice were placed individually in a cylindrical (diameter, 10 in.) recording chambers and allowed ad libitum access to food and water. EEG data were collected using a wire tether/commutator system (Plastics One, Roanoke, VA). All signals are amplified 100X at the preamplifier before the tether and swivel arrangement, and 100X at the main amplifier stage (10,000X total). Signals were filtered at 0.5 Hz high pass and 50 Hz low pass, and a 60 Hz digital notch filter was applied to all channels. Sampling at 400 Hz was digitized using a 14-bit A/D converter (Texas Instruments, Dallas, TX), collected and stored on a MacBook Pro (Apple, Cupertino, CA) computer running a PC emulator (VMware Fusion, Palo Alto, CA) and Sirenia software (Pinnacle, Austin, TX). Video recording of EEG sessions was performed with a Canon Optura Xi camera. EEG analysis was performed offline by manually scrolling through 60 second epochs of EEG data to detect repetitive rhythmic (2-8 Hz), high amplitude (>2 fold above background) sharp-wave activity lasting longer than 1 sec.

RT-PCR and qRT-PCR

Total RNA from one hemisphere of +/+ and ap/ap mouse brain was purified using Trizol Reagent and the PureLink Micro-to-midi Total RNA Purification System (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), following manufacturer’s protocol. On-column DNA digestion was performed using amplification grade DNase I (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). For qualitative RT-PCR, first strand cDNA synthesis was performed from 1 μg of total RNA using the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis SuperMix (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with random hexamers and oligo(dT), following manufacturer’s protocol. From the first-strand synthesis reaction, 3.5 μl were used as template for PCR amplification of full-length Hcn2 coding mRNA, which was performed under the following conditions: 1 min at 94°C, then 30 cycles of 20 s at 95°C, and 2 min at 68°C, followed by 3 min at 68°C using forward primer 5’-TTCTGCAGCCCGGCGTCAACAAG-3’ and reverse primer 5’-AGGGTGGCAATGGCCGATGTGA-3’ yielding a ~1.67 kb amplicon. As a control, PCR was performed with no template as well as from reactions containing no reverse transcriptase. Amplified PCR products were separated in 2% agarose gels and visualized with ethidium bromide staining. To compare relative Hcn2 transcript levels between ap/ap mice and +/+ controls, quantitative RT-PCR was performed on RNA samples prepared as described above using the QTaq One-Step qRT-PCR SYBR Kit (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) and a real-time PCR LightCycler (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). Reactions were performed in triplicate using intron-spanning primers to amplify Hcn2 message (forward 5’-GCGTGCCTTTGAGACCGT-3’ and reverse 5’-CTGAACCTTGTGTAGCAAGATGGA-3’). Hcn2 transcript levels were normalized to glyceraldehye-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh), which was amplified using forward primer 5’-GTCGTGGATCTGACGTGCC-3’ and reverse primer 5’-TGCCTGCTTCACCACCTTC-3’. Melting curves were used to confirm amplification of a single product.

Antibody preparation

cDNA encoding amino acids 45-135 of mouse Hcn2 was generated by PCR using primers (5’- CGCGAATTCACGACCCCCTCGCAC and 3’- CGCGTCGACGAAGCTAGCCTGGCT), followed by subcloning the PCR product into the EcoRI and BamHI sites of the glutathione-S-transferase-producing vector, pGEX-4T1 (Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ). Fusion protein was expressed in BL21 bacteria (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and purified by Glutathione-sepharose affinity chromatography according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). The purified HCN2 (45-135) fusion protein was used to immunize guineas pigs to produce antisera specific to the amino (N)-terminus of mouse HCN2 (α-N’-HCN2) (Affinity Bioreagents, Golden, CO).

Cos-7 cell culture, transfection, and generation of protein extracts

Cos-7 cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin (10 units/ml), and streptomycin (10μg/ml). Cells were transfected at 30% confluence in serum-free media using Lipofectamine plus reagent according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). After 24-36 hours, cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and protein extracts were generated in Teen-Tx (0.1M Tris, 1mM EDTA, 1mM EGTA, 1% Triton-X100).

Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting

+/+, ap/+ and ap/ap mice were anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation and sacrificed by decapitation. Brains were rapidly removed and homogenized in 10 vol (w/v) of buffer containing 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, and 320 mM sucrose, and centrifuged at 1000 × g to remove nuclei and insoluble material. The post-nuclear homogenate was centrifuged at 50,000 × g for 40 min to yield a cytosolic fraction (S2) and crude membrane pellet, which was resuspended in Teen-Tx (S3). Protein extracts were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Primary antibodies were diluted in block solution containing 5% milk and 0.1% Tween-20 in TBS (TBST) and incubated with membranes overnight at 4 °C or 1 hr at room temperature (RT) [guinea pig (gp) α-HCN2, 1:1000 (Shin et al., 2006); gp α-N’-HCN2. 1:500, rab α-HCN2, 1:200, Alomone, Israel; gp α-HCN1, 1:2000 (Shin and Chetkovich, 2007); gp α-HCN4, 1:2000, (Shin et al., 2008) and Supplementary Figure 1; mouse α-tubulin, 1:2000, Millipore, Bedford, MA]. Blots were washed 3 × 10 min with TBST, and species-appropriate secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ) was added in TBST containing 5% milk at a dilution of 1:2500. Labeled bands were visualized using Supersignal chemiluminescence (Pierce, Rockford, IL), and densitometric analysis performed using NIH Image J software.

Immunohistochemistry

For immunohistochemistry of fixed brain tissues, mice were perfused with fixative, 4% freshly depolymerized paraformaldehyde in PBS. Brains were removed and post-fixed overnight at 4°C in fixative, and parasagittal free-floating sections (50 μm) were cut on a microslicer (VT1000 S, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). DAB staining was performed with gp α-N’-HCN2 (1:500) followed by species-appropriate secondary antibody in an avidin–biotin–peroxidase system (ABC Elite; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Peroxidase staining was developed using 3,9-diaminobenzidine as the chromogen.

Light microscopy

Digital images of DAB-stained sections were taken with 3X or 8X objectives affixed to a Nikon SMZ 1000 microscope with SPOT Advance software, equipped with RT slider camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Inc., Sterling Heights, MI). All images were exported and analyzed using NIH image J software.

4-AP induced seizure and measurement of seizure severity

4-aminopyridine (4-AP) was administered intraperitoneally (10mg/kg, i.p) to 8-10 week old +/+ or ap/+ mice. Animals were returned to their cages, and behavior was observed continuously for up to 90 min. A stereotypical progression of seizures following 4-AP administration was scored according to prior studies (Weiergraber et al., 2006). Briefly, phase I was characterized as hypoactivity, phase II as partial clonus (including head bobbing and forelimb clonus), phase III as generalized myoclonus (including the whole body clonus, wild running, and loss of motor control), and phase IV as generalized tonic-clonic seizures (terminating in hindlimb extension upon the death of the animal).

Results

The apathetic phenotype

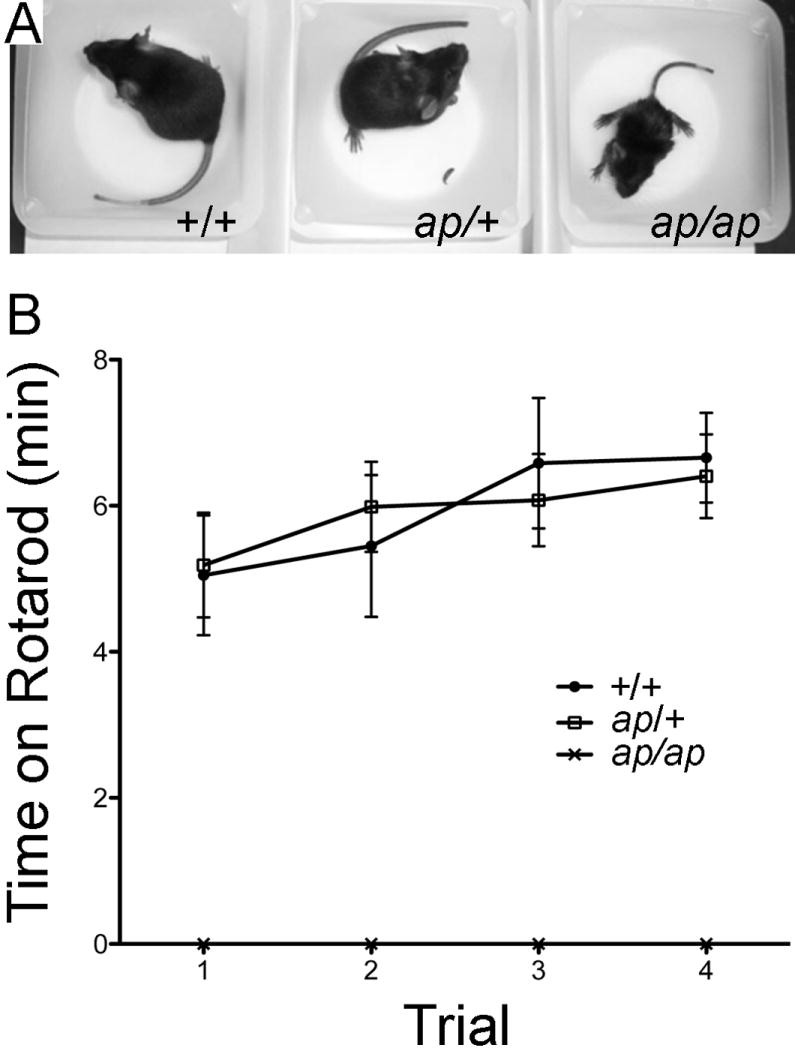

We discovered a new neurological mutant mouse, apathetic (Hcn2ap/ap, ap/ap), that arose spontaneously on a DW/Pas background. The mutation segregated as an autosomal recessive trait, and homozygous affected mice (ap/ap) were identifiable as early as postnatal day 14 by their diminished body length and weight (Figure 1 and Table 1). When forced to swim, ap/ap mice had difficulty in coordinating their extremity movements to orchestrate stroking motions, and would drown if allowed to do so. The ap/ap mice also demonstrated difficulty with balance and fell to one side when standing on their hind legs to feed. Furthermore, ap/ap but not heterozygous (ap/+) or wild type (+/+) animals exhibited striking motor incoordination (See Supplementary Video 1, showing +/+ and ap/ap mouse ambulating)). In a series of simple neurological screening tests (Paylor et al., 1998) that is summarized in Table 1, ap/ap mice showed evidence of ataxia, with unsteady gait and intention tremors as they ambulated. For example, when placed in a cage that was quickly lowered and moved from side to side +/+ and ap/+ animals splayed their legs and remained upright, whereas ap/ap animals exhibited postural instability and usually fell over. When placed in the center of a suspended platform, +/+ and ap/+ mice easily negotiated the platform, whereas the ataxic ap/ap mice were often unable to check themselves from falling at the edges. Motor coordination and balance were also tested using an accelerating rotarod. ap/ap mice were completely unable to walk on the rotarod without falling. Comparison of ap/+ and +/+ mice revealed that both genotypes spent increasing time on the rotarod with training [F(3,90) 2.91, P<0.05] (Figure 1). Both ap/+ and +/+ mice spent equal amounts of time on the rotarod [F(1,90) = 0.0007, P = 0.979]. Regardless of genotype, female mice spent significantly more time on the rotarod than male mice [F(1,90) = 8.88, P = 0.0001]. Other neurological reflexes such as the righting reflex, whisker touch response, eye blink, and ear twitch were indistinguishable between genotypes (Table 1). In summary, neurological testing revealed that ap/ap mice exhibit a profound motor defect that is most consistent with ataxia, whereas the motor function of ap/+ animals is indistinguishable from +/+ animals.

Figure 1.

Apathetic mice have smaller body size and an ataxic gait. A, photograph of postnatal day 25 wild type (+/+), heterozygous (ap/+) and apathetic (ap/ap) mice reveals smaller body size (also note the wide-based stance of the ap/ap mouse. B, Rotarod test. The averages ± S.E.M for time spent on the rotarod across four test trials for +/+ (filled circles), ap/+ (open squares) and ap/ap (x shape) mice. n=6 each male and female +/+, n=10 each male and female ap/+ and n=5 each ap/ap male and female. Note the ap/ap mice are totally unable to walk on rotarod, whereas +/+ and ap/+ mice perform equally well.

Table 1.

General motor and sensory responses of apathetic, heterozygous and wild type mice.

| +/+ | ap/+ | ap/ap | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical characteristics | |||

| Male weight (g) | 28.8 (±0.6) | 28.6 (±0.7) | 15.1 (±0.4)*** |

| Female weight (g) | 23.0 (±0.6) | 22.5 (±0.7) | 13.0 (±0.5)*** |

| Male length (cm) | 8.9 (±0.1) | 8.8 (±0.2) | 7.6 (±0.1)*** |

| Female Length (cm) | 8.7 (±0.1) | 8.8 (±0.2) | 7.2 (±0.1)*** |

| General behavioral observations (% subjects displaying response) | |||

| wild running | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| freezing | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| sniffing | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| licking | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| rearing | 100 | 100 | 20*** |

| jumping | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| defecation | 30 | 20 | 20 |

| urination | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| move around entire cage | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Sensorimotor reflexes (% subjects displaying “normal response”) | |||

| cage movement | 100 | 100 | 10*** |

| righting | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| whisker response | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| eye blink | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| ear twitch | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Motor responses | |||

| Elevated platform | |||

| latency to edge (sec) | 2.5 (±0.8) | 4.2 (±.1.1) | 13.8 (±.3.0)*** |

| no. of exploratory nose pokes | 9 (±1) | 10 (±1) | 1 (±0)*** |

| falls from platform (%) | 0 | 0 | 70*** |

Data represent the mean (±S.E.M.). Weight and length measurements include 13-16 mice of each gender and genotype. Behavioral testing includes 5 male and 5 female mice for each genotype.

P< 0.001

In addition to ataxia in the ap/ap mice, young (postnatal day 21-60) ap/ap mice, but not ap/+ or +/+ mice, demonstrate abnormal episodic motor behavior; 1) frequent episodes of brief behavioral arrest lasting 2-3 seconds 2) occasional repeated and rhythmic jumping toward the top of the cage on their hind legs, and 3) rare frank tonic-clonic convulsions. The latter rhythmic jumping and tonic-clonic convulsions are occasionally followed by a period of quiescence (postictal period), and animals have been observed to die immediately after these episodes. As ap/ap animals age, they become less active and interact less with their littermates and their environment by six months of age, hence their designation as apathetic (ap). As animals age, they continue to exhibit episodes of behavioral arrest, but jumping spells are no longer observed after 6 weeks of age, and older animals (>4 months) frequently assume an unusual posture for mice in which they curl up on their sides. ap/ap mice show increased mortality of 13.5% between the ages of 21-28 days of life with subsequent mortality of approximately 10% per month until 12 months of age by which time virtually all animals are dead. The cause of death has not been determined despite numerous post-mortem pathological examinations of affected animals, suggesting a neurological or cardiac electrical cause of death.

Epilepsy in apathetic mice

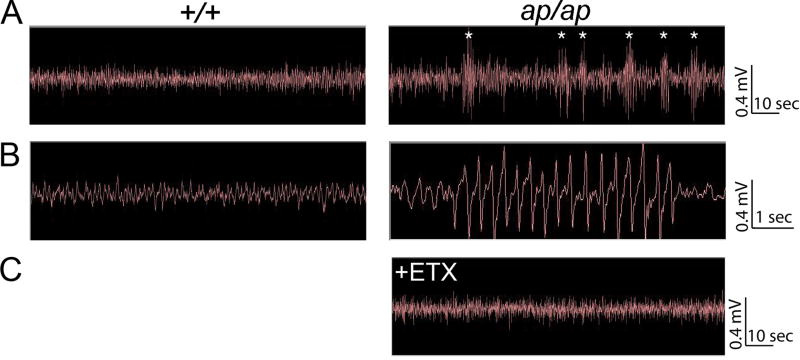

The abnormal “spells” observed in ap/ap mice resemble epileptic seizures, but in mice as in humans, it can often be difficult to distinguish between epileptic and nonepileptic events (Noebels, 2006). In order to evaluate whether ap/ap mice are epileptic, we performed cortical surface EEG recordings. Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of seizures noted through observation and EEG recording. From analysis of 50 hours of EEG recording, ap/ap animals exhibited frequent (4.2±0.7 events per minute, n=3), large amplitude (>2 fold baseline amplitude), runs of spike-wave discharges (Figure 2). The frequency of spike-wave discharges ranged from 3-7 Hz and individual runs of spike-wave lasted 1-3 seconds in duration. They were often, but not always, associated with a brief head twitch or behavioral pause. No EEG spike-wave discharges were observed in +/+ animals (n=3) in over 89 hours of recording. Because the spike-wave discharges coupled with behavioral pauses resembled absence seizures, we administered the Ca++ channel antagonist, ethosuximide, while recording EEG in ap/ap mice. Ethosuximide, a drug that specifically prevents absence seizures in humans and rodents (Browne, 1983; Heller et al., 1983; Sasa et al., 1988; Snead, 1988), completely eliminated the spike-wave discharges and episodes of behavioral arrest in ap/ap mice (Figure 2). We were unable to record the EEG during jumping spells (because the younger animals (<6 weeks) that exhibit jumping spells do not survive anesthesia and surgery for the EEG headmount), but strongly suspect they are epileptic because animals exhibit post-ictal quiescence and have been observed to die following these spells. EEG and video recorded during tonic-clonic convulsive events revealed these events to be epileptic as well (examples shown in Supplementary Figure 2 and Supplementary Video 2, respectively). In summary, behavioral observations together with findings of ethosuximide sensitive spike-wave discharges strongly suggest ap/ap mice have a generalized epilepsy syndrome that resembles human absence epilepsy.

Table 2.

Characteristics of seizures in ap/ap and ap/+ mice

| Genotype |

Sz type |

% with Sz |

Sz frequency |

Sz duration |

Spike-wave frequency |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral |

EEG |

|||||

| ap/ap | ||||||

| Behavioral Arrest | 100 | 9-10/hour | 200-300/hour† | 1-3 sec | 3-7 Hz | |

| Jumping spells | 100* | 2-3/hour | None* | N/A | N/A | |

| Gen. Tonic-Clonic | 100 | Occasional | Occasional | 5-30 sec | 3-7 Hz | |

| ap/+ | ||||||

| Behavioral Arrest | 20** | None** | 1-2/hour | 1-3 sec | 3-7 Hz | |

| Jumping spells | 0 | None | None | N/A | N/A | |

| Gen. Tonic Clonic | 0 | None | None | N/A | N/A | |

Note that EEG recording of ap/ap mice is 20-fold more sensitive than behavioral observation to detect seizures

Jumping spells are present between 3 and 6 weeks of age, but we are only able to record EEG from older ap/ap mice owing to the small size and fragility of younger mice.

In the ap/+ mice with spike-wave seizures on EEG recording, the motor manifestations are so infrequent and subtle that a trained observer does not score them.

Figure 2.

Epidural electrocephalographic (EEG) recordings from +/+ and ap/ap mice. A, Continuous two minute EEG recording in +/+ littermate (left panel) and ap/ap (right panel) mice. Asterisks (*) indicate typical spike-wave discharges observed in the ap/ap mice. B, Expanded time scale of EEG activity in +/+ (left trace) and ap/ap (right panel) mice demonstrates representative (3-7 Hz, 1-4 sec) spike-wave discharge recorded during behavioral arrest in an ap/ap mouse (right panel). C, Ethosuximide (ETX, 200 mg/kg, i.p.) injection in an ap/ap mouse eliminates behavioral arrests and spike-wave seizures detected by EEG.

Although ap/+ mice showed no overt behavioral arrest episodes, exhibited no jumping behaviors and had normal longevity, we nonetheless performed EEG monitoring of ap/+ mice to look for seizures. Indeed in >500 hours of recording in 10 mice we observed that two ap/+ mice exhibited the spontaneous, paroxysmal 1-3 second runs of spike-wave discharges that were observed in all of the ap/ap mice. Similar to ap/ap animals, retrospective video/EEG analysis revealed that these seizures were associated with behavioral arrest, however the seizures were much less frequent, occurring only 2-3 times per hour in the two ap/+ mice exhibiting seizures as opposed to 4-5 times per minute in each of the ap/ap mice.

Increased severity of provoked seizures in ap/+ mice

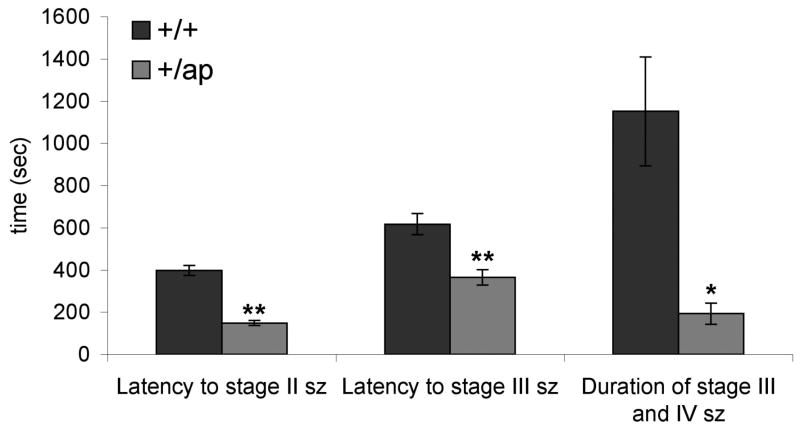

In contrast to ap/ap mice, only a small fraction of ap/+ mice exhibited spontaneous generalized absence seizures and spike-wave EEG abnormalities. We wondered whether the ap mutation might lead to increased seizure propensity in ap/+ animals not exhibiting spontaneous seizures. Thus, we investigated whether ap/+ mice are more susceptible to the chemoconvulsant-induced generalized seizures. Using the K+ channel blocker, 4-aminopyridine (4-AP, 10 mg/kg, i.p.), we induced seizures in +/+ and ap/+ mice. 4-AP blocks A-type K+ channels and delayed rectifier K+ channels, which induces burst firing and leads to generalized-tonic clonic seizures in mice and rats (Komagiri and Kitamura, 2003; Russell et al., 1994; Thompson, 1982). After 4-AP injection, we found that 14 out of 15 +/+ animals, and 17 out of 17 ap/+ animals developed generalized tonic clonic seizures (phase IV) leading to death. Interestingly, we found that the latency between injection of 4-AP and initiation of limb clonus (phase II) and generalized myoclonus (phase III) was significantly shorter in ap/+ compared to +/+ animals (Figure 3; phase II= 148.5±11.5 sec vs 397.3±23.3 sec, n=17 for ap/+, n=14 for +/+, ** P<0.001; phase III= 365.3±36.4 sec vs 616.2±50.2 sec, n=17 for ap/+, n=14 for +/+, ** P<0.001). Moreover, the duration of phase III plus phase IV seizures was markedly shorter in ap/+ compared to +/+ mice, (Figure 3; 192.5±50.4 sec vs 1150.8±257.7 sec, n=17 for ap/+, n=14 for +/+, * P<0.01). These data demonstrate that mice heterozygous for the ap allele have an accelerated epileptic response to the chemoconvulsant, 4-AP, and are consistent with neuronal hyperexcitability in the ap/+ mice.

Figure 3.

Seizure severity of ap/+ mice is higher than +/+ mice. Generalized seizures were induced by injecting +/+ (n=15) and ap/+ (n=17) mice with 4-aminopyridine (4-AP; 10mg/kg). Latency to stage II and III seizure as well as duration of stage III seizure are presented. Both latency and duration of seizures were significantly shorter in +/ap mice compared to +/+ mice (*P<0.01. ** P<0.001)

Genetic analysis of apathetic mice

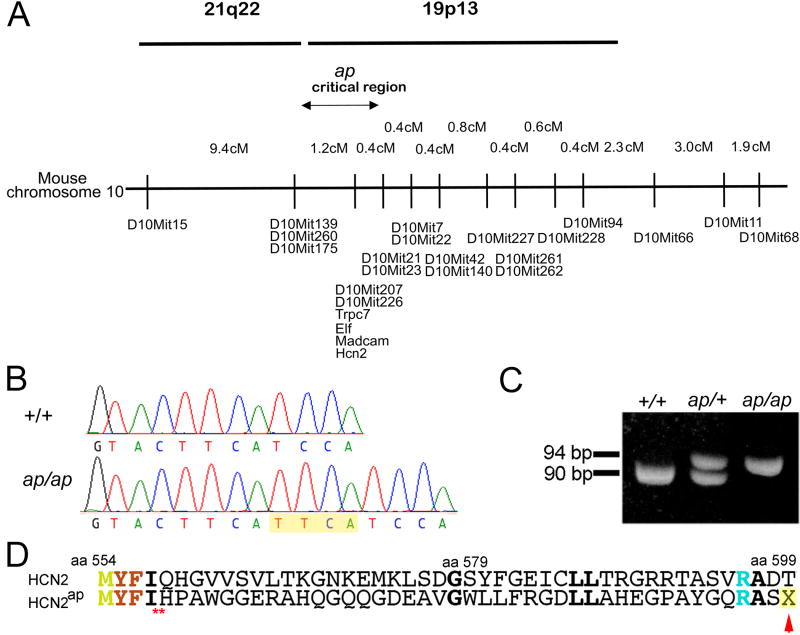

By linkage analysis, we mapped this new murine neurological mutation to mouse chromosome 10 at 40.4 cM (Figure 4A), constructed a complete mouse BAC contig across the non-recombinant interval and identified human genomic clones mapping to the orthologous region on human 19p13.3 (Puttagunta et al., 2000). By identifying and sequencing positional candidate genes mapping to this region in humans and mouse, we identified a 4 base pair insertion at nucleotide position 1669 in the cyclic nucleotide binding domain of the hyperpolarization-activated cation channel Hcn2 in the ap/ap mouse. This 4 base pair insertion, TTCA, is located in the middle of exon 6 of the Hcn2 gene as a tandem repeat, likely resulting from duplication of the same 4 bp 5’ to the insertion (Figure 4B). We designed a genotyping PCR primer pair for detecting a 90 bp fragment for the wild type Hcn2 allele and 94 bp fragment for the Hcn2ap allele. By separating PCR amplicons on non-denaturing gels we were able to confirm the genotypes of ap/ap, +/+ and ap/+ animals (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Apathetic mice harbor a four base pair insertion in the Hcn2 gene. A, Genetic map of mouse chromosome 10 at the apathetic locus with the homologous human chromosomes. Map based upon 946 meioses. Maximum, non-recombinant interval containing ap indicated. B, Schematic diagram of the 4 base pair insertion (TTCA) in Hcn2 in ap/ap mice, localized to the coding region of the cyclic nucleotide binding domain of HCN2 protein. C, Electropherograms of wild type and apathetic Hcn2 gene shows insertion of 4 base pairs, TTCA in Hcn2ap gene. D, PCR amplification of the Hcn2 gene yields a 90 and 94 base pair amplicon for wild type (+) and apathetic (Hcn2ap) alleles, respectively. E, A Predicted translation products of wild type and apathetic Hcn2 alleles show the frameshift and premature stop codon (red arrow) in predicted Hcn2ap.

Apathetic mRNA is transcribed

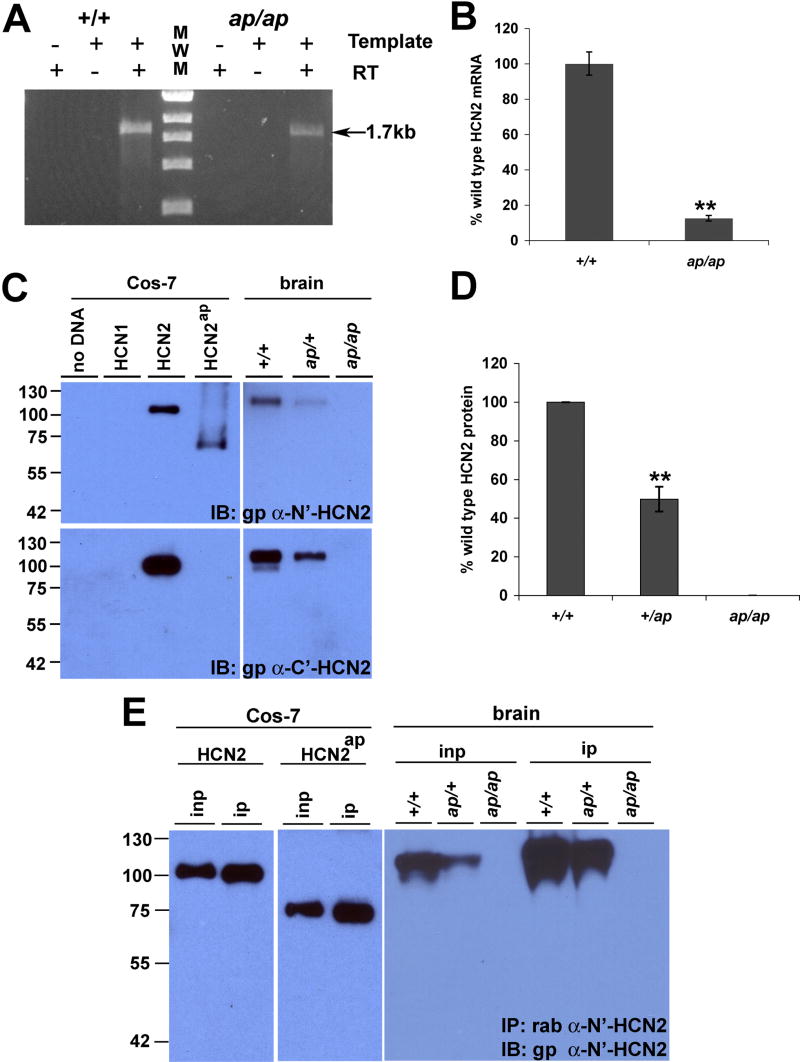

mRNA stability is governed by a complex and incompletely understood process, and even small insertions and deletions within mRNA sequences can lead to instability or decreased production of mRNA (Hollams et al., 2002). To evaluate expression of Hcn2ap, we performed reverse-transcription PCR (RT-PCR) of Hcn2 mRNA in +/+ and ap/ap animals. We amplified full-length HCN2 mRNA along with no template and no reverse transcriptase controls and found that HCN2 mRNA is detected in the brain of both +/+ and ap/ap mice (Figure 5A). To determine whether ap/ap mice have decreased quantity of Hcn2 mRNA, we performed quantitative real-time RT-PCR and found that Hcn2 mRNA is reduced by ~90% in ap/ap compared to +/+ mice (Figure 5B), suggesting that although the Hcn2ap mutation does not abolish transcription of Hcn2 mRNA, the ap mutation may affect production or stability of the Hcn2 mRNA.

Figure 5.

Hcn2ap is transcribed, but apathetic HCN2 protein is not detected. A, RT-PCR of full length of Hcn2 mRNA shows that Hcn2 mRNA is present in both wild type (+/+) and apathetic (ap/ap) mice (arrow). B, Quantitative RT-PCR shows that mRNA of Hcn2 is decreased by ~90% in ap/ap mice as compared to +/+ controls. C, Protein extracts from Cos-7 cells overexpressing wild type or apathetic HCN2 (HCN2ap), and protein extracts from +/+, ap/+, and ap/ap mouse brains were generated and separated by SDS-PAGE. Blots were labeled with gp α-HCN2 (C-terminal epitope) or gp α-N’-HCN2 (N-terminal epitope) antibodies. Gp α-HCN2 detects wild type HCN2, but not HCN2ap protein, whereas α-N’-HCN2 detects both proteins in overexpressed heterologous cells. α-N’-HCN2 does not detect HCN2ap in ap/+ or ap/ap brain, suggesting absence of HCN2ap protein. D, Protein expression of HCN2 was decreased ~50% in the brain of ap/+ compared to +/+ mice (n=4, ** P<0.01). E, HCN2ap protein was not detected even after concentrating protein extracts by immunoprecipitation. Protein extracts prepared from Cos-7 cells overexpressing wild type or HCN2ap, as well as +/+, ap/+, and ap/ap mouse brains were immunoprecipitated with rab α-HCN2 antibody and probed with gp α-N’-HCN2. Whereas both wild type and HCN2ap proteins in Cos-7 cells were concentrated and showed increased band intensity, no bands were detected from brain extracts of ap/ap mice. inp= input extract, ip= immunoprecipitated extract.

Apathetic protein is undetectable

The Hcn2ap allele is a 4 base pair insertion located within exon 6 of the Hcn2 gene, which, if translated, is predicted to produce a frame-shift and insertion of 41 new amino acids in the cyclic nucleotide binding domain of HCN2 before a stop codon is introduced (Figure 4D). Thus, whereas wild type HCN2 protein has a molecular weight of 100 kD (~110 kD with glycosylation), transcription and translation of Hcn2ap is predicted to produce a partial C-terminus-truncated HCN2 protein with expected mass of 70 kD (HCN2ap protein) by early termination of translation.

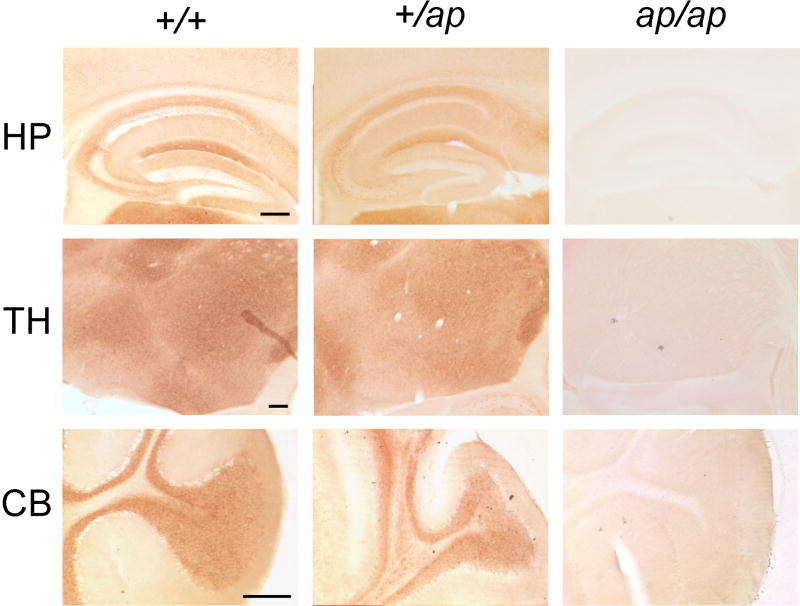

In order to detect ap protein, we generated an antibody that recognizes the N-terminus of mouse HCN2, an epitope predicted to be shared by wild type and HCN2ap protein. We subcloned, expressed, and purified the GST fusion protein, GST-HCN2(43-135), and then submitted the epitope for commercial generation of gp polyclonal antisera. Western blotting with gp-α-N’-HCN2(43-135) detected 100 kD and 110 kD bands in +/+ mouse brain extract, which correspond to glycosylated and non-glycosylated HCN2, respectively (Figure 5C and data not shown). We next demonstrated ability to detect both wild type HCN2 and HCN2ap. To do this we generated cDNA constructs encoding these HCN2 isoforms and transfected them into Cos-7 cells. As expected, western blotting of transfected Cos-7 cells using our α-N’-HCN2(43-135) recognized both proteins, whereas an antibody prepared against the C-terminus of mouse HCN2, α-HCN2(761-863) (Shin et al., 2006), detected wild type but not the truncated ap protein which has wild type sequence through amino acid 557. We then looked for the presence of ap HCN2 protein in brain by western blotting using the membrane extract of brains from +/+, ap/+ and ap/ap mice. Surprisingly, no bands were detected in the brain extract of ap/ap mice with α-HCN2 antibodies recognizing either the N-terminus (gp α-N’-HCN2) or C-terminus of HCN2 (gp α-HCN2) (Figure 5C-E). In the brain extracts of both +/+ and ap/+ mice, bands of 100 kD and 110 kD were detected with either antibody, corresponding to the predicted size of the unglycosylated and glycosylated wild type HCN2 protein (Figure 5D); however, HCN2 protein was 50% decreased in ap/+ compared to +/+ brain (50.0±6.4 % compared to +/+, n=4, * P<0.01, Figure 5D). We did not detect any smaller bands in ap/+ brain using the antibody that recognizes the HCN2 N-terminus, α-N’-HCN2(43-135). We also performed immunoprecipitation of HCN2 from brain extract using a commercial antibody prepared against the HCN2 N-terminus (rab α-HCN2, Alomone, Jerusalem), followed by detection with α-N’-HCN2(43-135). Although this antibody immunoprecipitated HCN2ap when expressed in Cos-7 cells, and increased the detection of wild type HCN2 protein in brain extract of ap/+ animals, we did not detect any HCN2ap expression in ap/+ or ap/ap animals (Figure 5E). We also used our sensitive and specific α-N’-HCN2(43-135) antisera to evaluate HCN2 immunoreactivity in immunohistochemical studies. Similar to what was observed using another specific HCN2 polyclonal antibody (Notomi and Shigemoto, 2004), α-N’-HCN2(43-135) demonstrated enhanced immunoreactivity in the stratum lacunosum moleculare of hippocampal area CA1, the granule cell layer of cerebellum and in the thalamus of both ap/+ and +/+ mice (Figure 6). Consistent with biochemical studies, we found no HCN2 immunoreactivity in ap/ap mouse brain (Figure 6). Thus, it is likely that Hcn2ap mRNA is not translated into protein or that the mutant ap protein is preferentially degraded. Taken together, these data suggest that the Hcn2ap allele is a functionally “null” mutation.

Figure 6.

Distribution of HCN2 protein in +/+, ap/+ and ap/ap mouse brain. 50 μm-think parasagittal brain sections were generated and immunohistochemistry was performed using gp α-N’-HCN2 antibody, visualized with DAB staining. HCN2 is concentrated in the stratum lacunosum-moleculare layer of hippocampal area CA1 (HP, top panel), thalamic nuclei (TH, middle panel), and granule cell layer in the cerebellum (CB, bottom panel). Note that distribution patterns of HCN2 are not significantly different between +/+ and ap/+ brains. No immunoreactivity of HCN2 was detected in ap/ap brain.

Expression of HCN1 and HCN4 is unchanged in apathetic mice

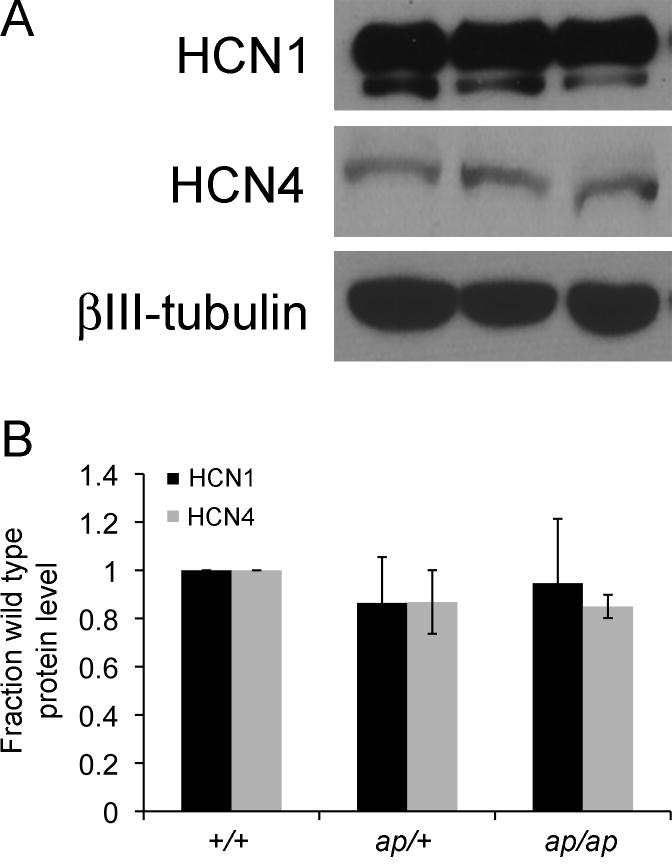

HCN subunit expression may be regulated by activity (Bender et al., 2003; Fan et al., 2005; van Welie et al., 2004). As such, it is possible that loss of HCN2 or seizures in the ap/ap mouse might change expression of other HCN subunits. Thus, in addition to HCN2, we also explored the expression levels of the other major brain HCN subunits, HCN1 and HCN4. Because we and others have noted that commercial anti-HCN preparations vary in sensitivity and specificity, we utilized custom antisera directed against HCN1 (Shin and Chetkovich, 2007) and HCN4 (Shin et al., 2008) to perform western blotting of extracts prepared from cortex of adult +/+, ap/+ and ap/ap mice. In contrast to HCN2 which was reduced in ap/+ and absent in ap/ap mice, levels of HCN1 and HCN4 protein in ap/+ and ap/ap mice were unchanged as compared to +/+ mice (Figure 7; HCN1: ap/+ 86 ± 19, ap/ap 87 ± 13 % of +/+ levels, n=3, P=0.75; HCN4 ap/+ 95 ± 26, ap/ap 85 ± 5 % of +/+ levels, n=3, P=.14). These data suggest that the ap mutation specifically reduces HCN2 protein levels without resulting in compensatory overexpression of HCN1 or HCN4.

Figure 7.

HCN1 and HCN4 expression in +/+, +/ap, and ap/ap brain. A. Brain extracts were generated and proteins separated by SDS-PAGE. Blots were probed with gp α-HCN1 antibody, gp α-HCN4 antibody, or ms α-βIII-tubulin antibody. B. Density of HCN1 and HCN4 bands were normalized to the density of βIII-tubulin to control for loading differences. No significant change in the protein expression levels of HCN1 or HCN4 was detected when comparing +/ap or ap/ap to +/+ mice (n=3, P=.75 and .14 for HCN1 and HCN4, respectively). Data shown are mean ± S.E.M.

Discussion

We report that a spontaneously arising 4 base pair insertion in the mouse gene encoding the h channel subunit, Hcn2, eliminates HCN2 protein production, and that homozygosity for the mutation produces an early onset neurological phenotype that includes ataxia and generalized absence seizures. The epilepsy, reduced size, and decreased viability of the homozygous ap/ap mice, which we have named apathetic, are similar to that reported previously for a targeted knockout of the Hcn2 gene (Ludwig et al., 2003). The initial report of the Hcn2 knockout mouse specifically described reduced locomotor activity (Ludwig et al., 2003); however, the Hcn2 knockout mouse was noted to be ataxic in a review of h channels (Herrmann et al., 2007). Our present study utilizes numerous behavioral observations to characterize the predominant ap/ap motor abnormality as ataxia. Seizures in mice heterozygous for the Hcn2 knockout allele have not been observed, but detailed analysis of these mice by EEG recording has not been performed (Personal communication, Andreas Ludwig). In contrast, we found spontaneous seizures and enhanced chemoconvulsant-induced seizures in the ap/+ mouse, suggesting the ap allele confers increased seizure propensity even in heterozygosity. We furthermore showed reduction of HCN2 protein levels, but not levels of HCN1 or HCN4 in brain of ap/ap and ap/+ mice, suggesting that the abnormalities in mice harboring the ap allele are due to loss of HCN2. Our findings are significant in that 1) we describe a novel, spontaneous mutation of the HCN2 gene that results in increased propensity to generalized seizures, 2) we identify a naturally-occurring Hcn2 mutation that results in an epilepsy phenotype similar to that observed in an engineered Hcn2 knockout mouse, and 3) we characterize the molecular and physiological consequences of the ap mutation of Hcn2 to expand our understanding of the relationship between HCN2 protein, ataxia, and epilepsy.

HCN2 is one of four subunits (HCN1-4) of the h channel, which mediates the current, Ih, in heart and brain (Ludwig et al., 1998; Santoro et al., 1998). Whereas all subunits are expressed in brain, HCN1, HCN2, and HCN4 are the predominant subunits. HCN1 and HCN2 are expressed together in neurons of the cortex, hippocampus and cerebellum, while HCN2 and HCN4 are the major h channel subunits expressed in the thalamus (Abbas et al., 2006; Notomi and Shigemoto, 2004; Santoro et al., 2000). Ih is critical for the rhythmic activity of thalamic neurons and the periodicity of thalamocortical network oscillations as a pacemaker (Maccaferri and McBain, 1996; Pape and McCormick, 1989). We report here that HCN2 (but not HCN1 or HCN4) levels are undetectable in ap/ap and significantly reduced in ap/+ mice. In the homozygous Hcn2 knockout animal, absence epilepsy results from a near complete loss of Ih in thalamocortical relay neurons, resulting in hyperpolarization of the resting membrane potential, an altered response to depolarizing inputs and an increased susceptibility to oscillations (Ludwig et al., 2003). Given the similar reduction in HCN2 without changes in HCN1 or HCN4, we reason that seizures present in mice harboring the ap mutation are likely due to specific loss of HCN2, and likely share a similar mechanism with the Hcn2 knockout animal.

We found 90% reduction of Hcn2 mRNA expression in ap/ap mice, and no HCN2ap protein. The absence of any detectable HCN2 protein in the brain of ap/ap mice indicates that the ap mutation is a null mutation, which is often the case when DNA insertion or deletion leads to a premature stop codon (Conti and Izaurralde, 2005). This inference is further supported by the several common phenotypes shared by the apathetic and Hcn2 knockout mice, including seizures, locomotor defects, small body length and weight compared to littermates, as well as whole-body tremor and progressive hypoactivity with age (Ludwig et al., 2003). Although otherwise indistinguishable from +/+ mice, ap/+ mice exhibit spontaneous seizures and increased susceptibility to chemoconvulsant-induced seizure progression. Whether mice heterozygous for the Hcn2 knockout allele have epilepsy has not been reported (Ludwig et al., 2003). We found a 50% reduction in HCN2 protein in the ap/+ mice, and no changes in HCN1 or HCN4. The results are analogous to those of Ludwig et al, who showed reduction of HCN2 but not HCN1 and HCN4 mRNA in mice heterozygous for the Hcn2 knockout allele (Ludwig et al., 2003). While it is possible that different strain background could influence seizure propensity differently in ap/ap versus Hcn2 knockout mice, it is also possible that undetectable levels of HCN2ap protein (which would not be present in mice heterozygous for the Hcn2 knockout allele) could impact h channel or other neuronal function and increase seizure propensity in ap/+ mice. Future studies will be aimed at exploring potential differences between the knockout and ap alleles with respect to epilepsy.

H channel abnormalities have been reported in several animal models of inherited generalized absence epilepsy (Di Pasquale et al., 1997; Kuisle et al., 2006; Strauss et al., 2004). In the rat models of absence epilepsy, Wistar Albino Glaxo/Rijswijk (WAG/Rij) rats and Genetic Absence Epilepsy Rats from Strasbourg (GAERS), onset of seizures is correlated with altered Ih and h channel expression in cortex and thalamus (Budde et al., 2005; Kole et al., 2007; Strauss et al., 2004). Interestingly, Blumenfeld et al recently found that pre-morbid treatment of WAG/Rij rats with ethosuximide prevented the development of absence epilepsy and eliminated reduction of HCN1 observed in these rats (Blumenfeld et al., 2008). These observations, coupled with our and others’ findings of absence epilepsy in the apathetic and Hcn2 knockout mice, respectively, suggest an important role for h channel changes in generalized absence epilepsy.

Ap/ap mice die prematurely from unknown causes. Although some ap/ap mice have been observed to die following myoclonic-like jumping or generalized convulsions, the cause of death is unresolved. Hcn2 knockout mice have cardiac sinus dysrhythmia characterized by increased variability in the heart rate at rest that is due to the reduction of Ih in cardiomyocytes (Ludwig et al., 2003). We are planning future studies to determine whether a similar cardiac abnormality exists in ap/ap animals, and will explore whether the premature deaths are due to intrinsic cardiac dysrhythmia or perhaps result from another process analogous to human “sudden death in epilepsy” (Nashef et al., 2007).

In summary, we discovered a novel spontaneous mutant mouse, apathetic, with a 4 base pair insertion at nucleotide 1669 in the cyclic nucleotide binding domain of the Hcn2 gene that eliminates HCN2 protein production. The phenotype of the ap/ap mouse includes ataxia and absence epilepsy that is ameliorated by ethosuximide treatment. Overall, these studies support the concept that h channels are critical for maintaining normal neuronal network oscillations, and that genetic loss of function of Hcn2 predisposes animals to generalized absence epilepsy. Although we do not yet know whether Hcn2 mutations cause familial epilepsy in humans, we reason that HCN2 may be an important target for future studies aimed at developing novel therapeutics to treat generalized epilepsy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Won Jun Choi for comments on the manuscript and Genn Suyeoka, Andrey Popov and Felix Nuñez-Santana for technical support. This research was supported by grants from the American Academy of Pediatrics: Young Investigator’s Research Award, Children’s Health Research Center (P30 HD34611), National Institutes of Health (R21 NS052595) and from the Partnership for Pediatric Epilepsy Research, which includes the American Epilepsy Society, the Epilepsy Foundation, The Epilepsy Project, Fight Against Childhood Epilepsy and Seizures (f.a.c.e.s.), and Parents Against Childhood Epilepsy (P.A.C.E.). We confirm that we have read the Journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Conflicts of Interest None of the authors has any conflict of interest to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abbas SY, Ying SW, Goldstein PA. Compartmental distribution of hyperpolarization-activated cyclic-nucleotide-gated channel 2 and hyperpolarization-activated cyclic-nucleotide-gated channel 4 in thalamic reticular and thalamocortical relay neurons. Neuroscience. 2006;141:1811–1825. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender RA, Soleymani SV, Brewster AL, Nguyen ST, Beck H, Mathern GW, Baram TZ. Enhanced expression of a specific hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated cation channel (HCN) in surviving dentate gyrus granule cells of human and experimental epileptic hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2003;23:6826–6836. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-17-06826.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenfeld H, Klein JP, Schridde U, Vestal M, Rice T, Khera DS, Bashyal C, Giblin K, Paul-Laughinghouse C, Wang F, Phadke A, Mission J, Agarwal RK, Englot DJ, Motelow J, Nersesyan H, Waxman SG, Levin AR. Early treatment suppresses the development of spike-wave epilepsy in a rat model. Epilepsia. 2008;49:400–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01458.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne TR. Ethosuximide (Zarontin) and other succinimides. In: Browne TR, Feldman RG, editors. Epilepsy: Diagnosis and Management. Little Brown & Co; Boston, Mass: 1983. pp. 215–224. [Google Scholar]

- Budde T, Caputi L, Kanyshkova T, Staak R, Abrahamczik C, Munsch T, Pape HC. Impaired regulation of thalamic pacemaker channels through an imbalance of subunit expression in absence epilepsy. J Neurosci. 2005;25:9871–9882. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2590-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess DL. Transgenic and gene replacement models of epilepsy: targeting ion channel and neurotransmission pathways in mice. In: Pitkanen A, Schwartzkroin PA, Moshe SL, editors. Models of seizures and epilepsy. Elsevier; London: 2006. pp. 199–223. [Google Scholar]

- Conti E, Izaurralde E. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay: molecular insights and mechanistic variations across species. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:316–325. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Pasquale E, Keegan KD, Noebels JL. Increased excitability and inward rectification in layer V cortical pyramidal neurons in the epileptic mutant mouse Stargazer. J Neurophysiol. 1997;77:621–631. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.2.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y, Fricker D, Brager DH, Chen X, Lu HC, Chitwood RA, Johnston D. Activity-dependent decrease of excitability in rat hippocampal neurons through increases in I(h) Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1542–1551. doi: 10.1038/nn1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller AH, Dichter MA, Sidman RL. Anticonvulsant sensitivity of absence seizures in the tottering mutant mouse. Epilepsia. 1983;24:25–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1983.tb04862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann S, Stieber J, Ludwig A. Pathophysiology of HCN channels. Pflugers Arch. 2007;454:517–522. doi: 10.1007/s00424-007-0224-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollams EM, Giles KM, Thomson AM, Leedman PJ. MRNA stability and the control of gene expression: implications for human disease. Neurochem Res. 2002;27:957–980. doi: 10.1023/a:1020992418511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kole MH, Brauer AU, Stuart GJ. Inherited cortical HCN1 channel loss amplifies dendritic calcium electrogenesis and burst firing in a rat absence epilepsy model. J Physiol. 2007;578:507–525. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.122028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komagiri Y, Kitamura N. Effect of intracellular dialysis of ATP on the hyperpolarization-activated cation current in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2003;90:2115–2122. doi: 10.1152/jn.00442.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuisle M, Wanaverbecq N, Brewster AL, Frere SG, Pinault D, Baram TZ, Luthi A. Functional stabilization of weakened thalamic pacemaker channel regulation in rat absence epilepsy. J Physiol. 2006;575:83–100. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.110486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig A, Budde T, Stieber J, Moosmang S, Wahl C, Holthoff K, Langebartels A, Wotjak C, Munsch T, Zong X, Feil S, Feil R, Lancel M, Chien KR, Konnerth A, Pape HC, Biel M, Hofmann F. Absence epilepsy and sinus dysrhythmia in mice lacking the pacemaker channel HCN2. Embo J. 2003;22:216–224. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig A, Zong X, Jeglitsch M, Hofmann F, Biel M. A family of hyperpolarization-activated mammalian cation channels. Nature. 1998;393:587–591. doi: 10.1038/31255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccaferri G, McBain CJ. Long-term potentiation in distinct subtypes of hippocampal nonpyramidal neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16:5334–5343. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-17-05334.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nashef L, Hindocha N, Makoff A. Risk factors in sudden death in epilepsy (SUDEP): the quest for mechanisms. Epilepsia. 2007;48:859–871. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noebels JL. Exploring new gene discoveries in idiopathic generalized epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2003;44(Suppl 2):16–21. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.44.s.2.4.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noebels JL. Spontaneous epileptic mutations in the mouse. In: Pitkanen A, Schwartzkroin PA, Moshe SL, editors. Models of seizures and epilepsy. Elsevier; London: 2006. pp. 222–233. [Google Scholar]

- Notomi T, Shigemoto R. Immunohistochemical localization of Ih channel subunits, HCN1-4, in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 2004;471:241–276. doi: 10.1002/cne.11039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pape HC, McCormick DA. Noradrenaline and serotonin selectively modulate thalamic burst firing by enhancing a hyperpolarization-activated cation current. Nature. 1989;340:715–718. doi: 10.1038/340715a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paylor R, Nguyen M, Crawley JN, Patrick J, Beaudet A, Orr-Urtreger A. Alpha7 nicotinic receptor subunits are not necessary for hippocampal-dependent learning or sensorimotor gating: a behavioral characterization of Acra7-deficient mice. Learn Mem. 1998;5:302–316. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puttagunta R, Gordon LA, Meyer GE, Kapfhamer D, Lamerdin JE, Kantheti P, Portman KM, Chung WK, Jenne DE, Olsen AS, Burmeister M. Comparative maps of human 19p13.3 and mouse chromosome 10 allow identification of sequences at evolutionary breakpoints. Genome Res. 2000;10:1369–1380. doi: 10.1101/gr.145200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell SN, Publicover NG, Hart PJ, Carl A, Hume JR, Sanders KM, Horowitz B. Block by 4-aminopyridine of a Kv1.2 delayed rectifier K+ current expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J Physiol. 1994;481(Pt 3):571–584. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoro B, Chen S, Luthi A, Pavlidis P, Shumyatsky GP, Tibbs GR, Siegelbaum SA. Molecular and functional heterogeneity of hyperpolarization-activated pacemaker channels in the mouse CNS. J Neurosci. 2000;20:5264–5275. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-14-05264.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoro B, Liu DT, Yao H, Bartsch D, Kandel ER, Siegelbaum SA, Tibbs GR. Identification of a gene encoding a hyperpolarization-activated pacemaker channel of brain. Cell. 1998;93:717–729. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81434-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasa M, Ohno Y, Ujihara H, Fujita Y, Yoshimura M, Takaori S, Serikawa T, Yamada J. Effects of antiepileptic drugs on absence-like and tonic seizures in the spontaneously epileptic rat, a double mutant rat. Epilepsia. 1988;29:505–513. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1988.tb03754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin M, Brager D, Jaramillo TC, Johnston D, Chetkovich DM. Mislocalization of h channel subunits underlies h channelopathy in temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurobiol Dis. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin M, Chetkovich DM. Activity-dependent regulation of h channel distribution in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:33168–33180. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703736200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin M, Simkin D, Suyeoka GM, Chetkovich DM. Evaluation of HCN2 abnormalities as a cause of juvenile audiogenic seizures in Black Swiss mice. Brain Res. 2006;1083:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.01.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snead OC., 3rd Gamma-Hydroxybutyrate model of generalized absence seizures: further characterization and comparison with other absence models. Epilepsia. 1988;29:361–368. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1988.tb03732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinlein OK. Genes and mutations in human idiopathic epilepsy. Brain Dev. 2004;26:213–218. doi: 10.1016/S0387-7604(03)00149-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss U, Kole MH, Brauer AU, Pahnke J, Bajorat R, Rolfs A, Nitsch R, Deisz RA. An impaired neocortical Ih is associated with enhanced excitability and absence epilepsy. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:3048–3058. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-816X.2004.03392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson S. Aminopyridine block of transient potassium current. J Gen Physiol. 1982;80:1–18. doi: 10.1085/jgp.80.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Welie I, van Hooft JA, Wadman WJ. Homeostatic scaling of neuronal excitability by synaptic modulation of somatic hyperpolarization-activated Ih channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:5123–5128. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307711101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.