Abstract

Background

Alcohol use-related problems and depressive symptoms are clearly associated with each other, but results regarding the nature of this association have been inconsistent. In addition, the possible moderating effects of age and gender have not been comprehensively examined. The goals of this study were to clarify (1) how depressive symptoms affect the levels and trajectory of alcohol use-related problems, (2) how alcohol use-related problems affect the levels and trajectory of depressive symptoms, and (3) whether there are differences in these associations at different points in development or between males and females.

Methods

Participants for this study were drawn from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (AddHealth) data set, a community-based sample of 20,728 adolescents followed from adolescence through early adulthood. Multilevel models were used to assess how each problem affected the level and rate of change in the other problem over time; gender was considered as a possible moderator of these associations.

Results

The results indicated that alcohol use-related problems and depressive symptoms had reciprocal, positive effects on each other during the period from early adolescence through early adulthood; however, these effects differed somewhat by gender and age. High levels of depressive symptoms were associated with higher initial levels of alcohol problems (particularly among females), as well as faster increases in alcohol problems over time among males. High levels of alcohol problems were associated with higher initial levels of depressive symptoms (particularly among females), as well as less curvature in the slope of depressive symptoms so that although there was a large difference between people with high and low depressive symptoms in early adolescence, by early adulthood the difference was smaller (particularly among females).

Conclusions

These results highlight the importance of examining gender and age in studies on the associations between affective disorders and substance use disorders.

Keywords: alcohol, depression, comorbidity, longitudinal, adolescence

For decades, theorists and researchers have discussed associations between depression and alcohol use disorders (e.g., Zucker, 1986) and recent commentaries have noted the need for research on the relation between alcohol use disorders and mood disorders (e.g., Li et al., 2004). However, the results of empirical studies on the nature of this association have been inconsistent. These inconsistencies may be due, in part, to the fact that different studies use samples that vary in their gender and age composition. This study examined the longitudinal associations between alcohol problems and depressive symptoms in a community-based sample of youth. By using an analytic approach that examined within-person trajectories of change over time (i.e., how levels of one problem predicted both level and rate of change of the other problem) it provides a unique angle on these associations across the period from early adolescence through early adulthood. It also adds to the existing literature by reporting cross-sectional correlations between continuous measures of depressive symptoms and alcohol use-related problems from early adolescence through early adulthood in a single community-based sample.

Previous Research on Alcohol Problems and Depression

Major depressive disorder (MDD) has long been linked to alcohol use disorders (here, these disorders are considered together with depressive symptoms and alcohol use-related problems due to evidence that levels of these symptoms fall on a continuum in the population [e.g., Hankin et al., 2005; Hasin et al., 2006]). These two problems have been discussed together for theoretical reasons, with the concept of “negative affect alcoholism” dating back several decades (see Zucker, 1986 for a discussion of this). Alcohol (or other substances) may be used by people with depressive feelings to help them cope (“self-medication”); substance use may be especially reinforcing for depressed people because it can decrease negative feelings. In turn, alcohol problems may predispose people to depression, either through physiological effects of heavy substance use or because the consequences of problem use (e.g., family problems, school or work problems) may be depressing. Alternatively, both depression and alcohol problems may be different expressions of an underlying risk factor (such as difficulty with emotion regulation, poor family relationships, etc.), a shared comorbid condition, or a shared genetic diathesis (Nurnberger et al., 2002). Evidence has supported both models that emphasize the likelihood that alcohol problems and depression act as risk factors for each other (see Swendsen and Merikangas, 2000 for a review) and models that support the potential shared neurobiological underpinnings of these problems (Rao, 2006).

Evidence is conflicting regarding the temporal association between depression and alcohol problems. Some studies have found that depression predicts alcohol problems (e.g., Abraham and Fava, 1999), whereas others have found that alcohol problems (or substance problems in general—including illicit drug-related problems) predicts depression (e.g., Bovasso, 2001; Bukstein et al., 1992; Rao et al., 2000; Rohde et al., 2001; Stice et al., 2004). Furthermore, a number of studies have found a reciprocal association: that depressive disorders predict substance problems and substance problems predicts depression (e.g., Clark et al., 1997; Deykin et al., 1992; Hettema et al., 2003; Swendsen et al., 1998). However, it is important to note that for each of these patterns, there are also negative findings—findings that one problem does not predict the other over time.

There are several potential factors that could account for these discrepant findings. First, these associations may differ by age. Among studies that include frequent assessments, there is some indication of more reciprocal prediction (depression predicting substance abuse and the reverse) in early to mid-adolescence (Stice et al., 2004, in univariate analyses predicting the onset of each problem by the other problem) than in late adolescence to early adulthood (Rao et al., 2000). Several other studies are consistent with the notion of closer associations between these problems among younger people: (1) a retrospective study indicated that adolescent-onset substance use disorders (SUDs—abuse and dependence) may be more strongly related to depression than adult-onset SUDs (Clark et al., 1998); (2) a prospective study found that persistent internalizing problems predicted persistent substance use in preadolescence, but the same was not true during adolescence (Loeber et al., 1999); and (3) in the same sample, the level of depression among 13-year-olds was associated with concurrent level of alcohol use but did not predict change in alcohol use over time (White et al., 2001). It is not clear whether the possible closer associations between SUDs and depression among younger people are related to aspects of the disorders or developmental periods themselves or whether early-onset cases represent more severe variants, which would make it more likely that people with early-onset cases had either particularly strong genetic predispositions (to both problems or to a neurobiological factor that increased risk for both problems, such as difficulties with emotion regulation) or particularly noxious environments (e.g., severe abuse; Clark et al., 2003). Adolescent-onset depression does predict risk for later depression and impaired functioning (Weissman et al., 1999) and early-onset binge drinking does predict later alcohol abuse and dependence (Chassin et al., 2002), though whether these increased risks carry over to increased risk for other problems remains an open question.

Second, these associations may differ by gender. Several studies have found that the link between depression and substance problems is stronger in females than males (Bukstein et al., 1992; Clark et al., 1997; Deykin et al., 1992). However, some contradictory evidence exists (Costello et al., 1999; Henry et al., 1993), and several studies have found that associations between depression and substance problems are similar for males and females (e.g., Hettema et al., 2003; Marmorstein and Iacono, 2003; Rohde et al., 2001). Among longitudinal studies, no clear pattern has emerged, though it is possible that SUDs may more commonly precede MDD in males, while MDD may be equally likely to precede or follow SUDs in females (Clark et al., 1997; Hettema et al., 2003).

Third, these associations may differ by type of substance (alcohol versus illicit drugs), although there is limited evidence to support this notion. Of the prospective studies discussed above, the one that examined adolescent alcohol use disorders found that they predicted later MDD (Rohde et al., 2001); similarly, the one that focused on drug use disorders found that cannabis abuse predicted later depression among adults (Bovasso, 2001). Retrospective studies do not indicate any clear difference in patterns between alcohol and illicit drugs (e.g., Abraham and Fava, 1999; Clark et al., 1997; Hettema et al., 2003; Swendsen et al., 1998), however there is too little evidence to conclusively state whether these associations differ by type of substance.

Fourth, there may be a difference in associations between depression and substance problems when diagnoses versus symptoms are considered. However, no clear pattern based on this distinction emerges in the literature to date. When SUDs and depressive diagnoses are considered, some evidence points to SUDs predicting depressive disorders (Bukstein et al., 1992; Hettema et al., 2003; Rao et al; Rohde et al., 2001; but see Abraham and Fava, 1999), though there is also evidence of reciprocal prediction (Clark et al., 1997; Deykin et al., 1992; Swendsen et al., 1998). Fewer studies have examined depressive and substance-related symptoms, but the evidence from those also tends to point to substance-related symptoms predicting depressive symptoms (Bovasso, 2001; Stice et al., 2004 [which examined substance-related symptoms as predictors of the onset of depressive pathology]). This similar pattern of results is not surprising, given that depression and substance-related problems occur on continua in the population (Hankin et al., 2005; Hasin et al., 2006).

Fifth, these associations may differ based on whether the samples were recruited from clinics or from the community. However, no clear pattern based on sample origin emerges. Clinic samples have yielded results indicating that depression predicts alcohol problems (Abraham and Fava, 1999), that substance problems predicts depression (Bukstein et al., 1992), and that there is a reciprocal association between the two (Clark et al., 1997; Deykin et al., 1992). Community samples have yielded results indicating that substance problems predicts depression (Bovasso, 2001; Rao et al., 2000; Rohde et al., 2001; Stice et al., 2004) and that there is a reciprocal relation between the two (Hettema et al., 2003; Swendsen et al., 1998). The lack of community-based studies finding unidirectional effects from depression to substance problems may not reflect a true lack of effect, though, since multiple community-based studies have found reciprocal relations between the two problems.

Current Study

The goals of the present study were to clarify (1) how depressive symptoms predict the levels and trajectory of alcohol use-related problems, (2) how alcohol use-related problems predict the levels and trajectory of depressive symptoms, and (3) whether there are differences in these associations at different points in development or between males and females. The period from early adolescence through early adulthood was considered, and a community-based sample of youth was used to avoid the biases associated with treatment-seeking populations.

A multilevel modeling approach was used. Simple variable-centered prospective analyses, in which a variable at one point in time is used to predict another variable at a later point in time, have traditionally been used but are limited in several ways. For example, only two assessment points can be examined. Also, if the sample is a single uniform age, these studies can only tell us about the relation between the variables at the two assessment ages; if the sample includes youth of different ages, important developmental differences may be masked. Thus, for developmentally-focused research, multilevel modeling has significant advantages. This approach first determines typical trajectories of each type of problem over this time period, then examines how each problem relates to increases or decreases in the level and rate of change of the other problem within individuals. Potential gender differences were assessed by entering gender into the model as another possible predictor of trajectories. By examining the shape of these trajectories over time and the effects of each problem on the slope of the trajectories, the possibility that these associations differed at different ages/developmental stages was examined.

Hypotheses were developed based on both theoretical reasons (the self-medication model of substance abuse and the possibility that heavy substance use may cause physiological and/or psychosocial consequences that increase risk for depression) and empirical evidence supporting reciprocal pathways between depression and alcohol problems. Overall, it was expected that higher levels of depressive symptoms would be associated with both higher levels of alcohol use-related problems and faster increases in alcohol use-related problems over time. Reciprocally, it was expected that higher levels of alcohol use-related problems would relate to both higher levels of depressive symptoms and faster increases in depressive symptoms over time. It was tentatively expected that, if gender differences were found, associations between the two problems would be stronger for females, compared to males. It was also expected that, if developmental differences were found, the reciprocal effects of these problems would be stronger among younger, compared to older, youth.

In addition to these analyses addressing the effect of each problem on the trajectory of the other problem, we also report cross-sectional correlations between these problems at each age, by gender. These analyses allow for an examination of developmental trends in the concurrent associations between alcohol use-related problems and depressive symptoms.

Method

Participants

Participants for this study were drawn from the restricted-use contractual data set of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (AddHealth) data set (Udry, 2003). The Rutgers University Institutional Review Board approved the data analysis project presented here. At Wave 1 (1994–1995), the AddHealth team collected a stratified, random sample of students from high schools in the United States; the high schools were stratified into clusters based on region, urbanicity, size of school, type of school, percentage of school that was white, percentage of school that was black, span of grades included in the school, and type of curriculum the school offered. Participating high schools then identified middle schools or junior high schools that contributed at least five students to the entering class of the high school; students from one feeder school per high school were selected for inclusion in this study. Students from 145 middle, junior high, and high schools participated in this initial phase of data collection. Next, in-home interviews were completed with a core sample from each community as well as participants from some “saturated schools” (schools in which all students were included in the in-home sample) and over-samples of some special populations (adolescents with limb disabilities, black participants from well-educated families, Chinese, Cuban, and Puerto Rican adolescents, and adolescents residing with other genetically related or non-related adolescents in the sample). Mothers of these in-home interview participants were also interviewed. All students (n=20,728) were in grades 7–12 during the 1994–95 school year when these data were collected (age range=11–21; a total of 80 [0.38%] students were 20 or 21 at this assessment and were most likely receiving special education services or were learning English as a second language). Approximately 1 year later (1996), in-home follow-up interviews (Wave 2) were conducted with 71% (n=14,738) of these adolescents (age range=11–23); adolescents who were no longer in high school (i.e., participants who were in 12th grade at Wave 1) were not followed-up at this time. Approximately 6 years after the initial assessment (2001–2002), the original participants were located and invited to participate in in-home interviews again (Wave 3); 73% of the Wave 1 sample (n=15,197) did so (age range 18–28). Additional information regarding the design of this study can be found in Harris et al. (2003).

At Wave 1, participants in this study were a mean age of 15.66 (SD=1.75). At Waves 2 and 3, they averaged 16.22 (SD=1.65) and 21.96 (SD=1.77) years old, respectively. At Wave 1, twenty-three percent were African-American, 8% were Asian-American or Pacific Islander, 4% were Native American, and 61% were Caucasian. In addition, 17% were Hispanic or Latino. Eighty-two percent of mothers had graduated from high school or gotten their GED, and 23% of mothers had graduated from college by the time of the Wave 1 assessment. Mothers reported that 9.7% of families were receiving some form of public assistance (such as welfare).

Overall response rates were 78.9% at Wave 1, 88.2% at Wave 2, and 77.4% at Wave 3. To assess for the possibility of differential attrition, participants who completed both the Wave 1 and Wave 3 assessments were compared to participants who completed the Wave 1 assessment only on levels of depressive symptoms and alcohol problems (Wave 2 was not included in this analysis since participants who had graduated from high school between Wave 1 and Wave 2 were intentionally not assessed at Wave 2). There were no differences in levels of Wave 1 depressive symptoms between these groups (t=−.98, p>.05). Wave 3 non-participants had slightly higher mean levels of alcohol problems at Wave 1 (t=−3.52, p<.001), but this effect seemed to be related to the higher levels of Wave 3 non-response among older participants (who were more likely to have had alcohol problems at Wave 1, due to being in late, as opposed to early, adolescence). Specifically, mean levels of Wave 1 alcohol problems among participants who did and did not participate at Wave 3 were similar when participants of similar ages were examined (e.g., when Wave 3 participants and non-participants who were 12–13 and 17–18 at Wave 1 were compared separately, there were no differences in alcohol problems between the groups [t=−1.44, p>05 and t=−1.17, p>.05, respectively]).

Measures

Depressive symptoms

Nine depression-related questions, drawn from the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977), were asked of participants at all three assessments. Each item was rated on a 4-point scale (never/rarely, sometimes, a lot of the time, most of the time/all of the time), resulting in a scale ranging from 0 to 27 (actual maximum score = 27). The participants were instructed to report on symptoms they may have had during the past week. The mean total score (across all waves and ages) was 5.55 (standard deviation [SD] = 4.26); among people who had used alcohol at least 2–3 times, the mean score was 5.75 (SD = 4.38). Standardized Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for this scale ranged from .80 at the first assessment to .81 at the third assessment. Although this was a shorter scale than that used at Waves 1 and 2 and previously shown to have considerable validity (e.g., Rende et al., 2006; Steuber and Banner, 2006), it correlated highly with the longer scale that was administered at Waves 1 and 2 (r=.95 at Wave 1, r=.96 at Wave 2). The CES-D has been shown to be strongly associated with diagnoses of major depression in other community-based samples of adolescents (e.g., Prescott et al., 1998).

Alcohol use-related problems

Seven questions regarding alcohol use-related problems were asked of participants at all three assessments. Each asked about the participant’s frequency during the past twelve months of experiencing various types of problems that may occur as a result of alcohol use (e.g., “…you’ve had problems at school or with school work because you had been drinking”; “…you had problems with your friends because you had been drinking”). All items were either developmentally appropriate at all ages (e.g., gotten into a physical fight due to drinking) or were modified to be developmentally appropriate (e.g., the item above relating to problems with school or school work was changed at Wave 3 to reflect problems with school or work). Each item was rated on a 5-point scale (ranging from “never” to “5 or more times”), resulting in a scale ranging from 0 to 35 (actual maximum score = 28). The mean score (across all waves and ages) was 1.47 (SD = 2.95; median = 0.00); among people who had used alcohol at least 2–3 times, the mean score was 2.82 (SD = 3.57; median = 2.00). Standardized Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for this scale ranged from .74 at the first assessment to .76 at the third assessment. Scores on this measure were log-transformed due to skew.

Gender

The biological sex of each participant was recorded when demographic information was collected during the first assessment. Males were coded zero and females were coded one.

Age

The age of each participant was recorded at the time of each assessment.

Statistical Analyses

Prior to analyses being conducted, each participant’s score on each measure at each assessment wave was converted to a score at each age he or she was assessed. This resulted in a data structure in which each participant contributed data at his or her set of three ages (e.g., ages 12, 13, and 18 for one participant; ages 17, 18, and 23 for another).

First, means and standard deviations for depressive symptoms and alcohol use-related problems were computed for participants at each age. Then, cross-sectional Pearson correlations between these problems were computed for males and females separately at each age.

Multilevel models for predicting change were used to investigate the effect of depressive symptoms on alcohol use problem trajectories over time and the effect of alcohol use problems on depressive trajectories over time. This method is functionally the same as growth curve modeling or mixed effects models (e.g., Singer, 1998). Models were estimated using PROC MIXED in the Statistical Analysis System (SAS) version 9.1. Full information maximum likelihood estimation (ML) was used in order to compare directly the fit of nested models to the data and in order to use all available data, given the presence of missing observations, which were treated as missing at random (Singer and Willett, 2003). Both the likelihood ratio test (LRT; comparing the –2 log likelihood of nested models) and the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) were used to assess model fit (Singer and Willett, 2003).

First, unconditional growth models for alcohol use-related problems (dependent variable) were estimated and investigated in order to examine whether a linear or quadratic model best fit the data. Then, the potential influence of gender on alcohol problems was investigated by entering gender as a time-invariant predictor. Next, depressive symptoms at each time point (a time-varying predictor) were added to the model in order to examine whether depressive symptoms, alone or in combination with gender, affected the trajectory of alcohol problems over time. The final model was determined by examining both the pattern of significance of the predictors and the fit statistics of the models.

Next, analogous models were estimated using depressive symptoms as the dependent variable and age, gender, and alcohol use-related problems as predictor variables. Briefly, models including (1) a linear slope, (2) a quadratic slope, (3) slope terms plus gender, and (4) slope terms, gender, and alcohol problems were examined.

Initially, participants who reported not having a drink of alcohol more than two or three times in their lives and never drinking outside the family were assigned a score of zero on the measure of alcohol problems. After these primary analyses, all analyses were re-run including only participants who reported having had alcohol at least 2–3 times in their lives to examine whether the associations were similar in the entire sample and in the sub-sample of alcohol users.

These analyses resulted in models in which main effects of each predictor reflected the influence of the predictor on the initial level of the dependent variable, while the interaction effects of the predictors with the slope terms indicated how, at each age, the predictor variable deflected the individual’s score on the dependent variable off of the typical developmental trajectory. In models of this type, if the association between these problems remained the same at different ages, that would be indicated by a non-significant interaction between the independent variable (alcohol problems or depression) and the term(s) in the equation that represented slope (linear and/or quadratic). In contrast, a significant interaction between the independent variable and slope term(s) would indicate that the effect of the predictor varied at different points in development. The intercepts and slopes are estimated independently, so while earlier levels of the dependent variable are not statistically “controlled for,” the estimate of initial values is separated from the estimate of change over time.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Means and standard deviations for depressive symptoms and alcohol use-related problems are presented in Table 1. Depressive symptoms peaked at age 17 and alcohol problems peaked at age 22.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and cross-sectional correlations between depressive symptoms and alcohol use-related problems.

| Age (na) | Mean (SD) Depressive Symptomsb | Mean (SD) Alcohol Problemsb | Correlationb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | Females | All | Males | Females | All | Males | Females | |

| 12 | 4.64 | 5.28 | 5.00 | .23 | .11 | .16 | .07 | .27*** |

| (n = 591) | ||||||||

| (3.46) | (3.83) | (3.68) | (1.63) | (.79) | (1.24) | |||

| 13 | 4.34 | 5.39 | 4.92 | .24 | .34 | .30 | .10*** | .10*** |

| (n = 2846) | ||||||||

| (3.29) | (4.18) | (3.84) | (1.13) | (1.43) | (1.30) | |||

| 14 | 4.54 | 6.07 | 5.35 | .45 | .63 | .54 | .10*** | .24*** |

| (n = 4557) | ||||||||

| (3.52) | (4.56) | (4.18) | (1.71) | (1.92) | (1.83) | |||

| 15 | 5.04 | 6.77 | 5.94 | .82 | .99 | .91 | .11*** | .21*** |

| (n = 5817) | ||||||||

| (3.66) | (4.69) | (4.31) | (2.20) | (2.39) | (2.30) | |||

| 16 | 5.40 | 6.88 | 6.14 | 1.16 | 1.14 | 1.15 | .15*** | .20*** |

| (n = 6859) | ||||||||

| (3.86) | (4.55) | (4.29) | (2.72) | (2.59) | (2.65) | |||

| 17 | 5.69 | 6.84 | 6.26 | 1.50 | 1.23 | 1.36 | .12*** | .14*** |

| (n = 6926) | ||||||||

| (3.94) | (4.57) | (4.31) | (2.99) | (2.68) | (2.84) | |||

| 18 | 5.69 | 6.75 | 6.21 | 1.93 | 1.36 | 1.65 | .10*** | .12*** |

| (n = 5319) | ||||||||

| (3.96) | (4.61) | (4.32) | (3.43) | (2.81) | (3.15) | |||

| 19 | 5.19 | 5.92 | 5.56 | 2.35 | 1.96 | 2.15 | −.02 | .09** |

| (n = 2592) | ||||||||

| (4.00) | (4.60) | (4.33) | (3.69) | (3.39) | (3.54) | |||

| 20 | 4.32 | 5.47 | 4.94 | 2.65 | 2.00 | 2.30 | .09** | .08** |

| (n = 2097) | ||||||||

| (3.80) | (4.56) | (4.26) | (3.75) | (3.16) | (3.46) | |||

| 21 | 4.29 | 4.83 | 4.59 | 3.03 | 1.99 | 2.46 | .07* | .03 |

| (n = 2336) | ||||||||

| (3.78) | (4.27) | (4.06) | (3.94) | (3.09) | (3.54) | |||

| 22 | 4.31 | 5.19 | 4.76 | 3.09 | 2.09 | 2.57 | .11*** | .02 |

| (n = 2737) | ||||||||

| (3.83) | (4.39) | (4.15) | (3.86) | (3.26) | (3.59) | |||

| 23 | 4.36 | 4.92 | 4.66 | 2.95 | 1.94 | 2.42 | .12*** | .06* |

| (n = 2718) | ||||||||

| (3.87) | (4.29) | (4.11) | (3.86) | (3.11) | (3.52) | |||

| 24 | 3.98 | 4.86 | 4.43 | 2.77 | 1.87 | 2.32 | .03 | .06 |

| (n = 2298) | ||||||||

| (3.71) | (4.29) | (4.05) | (3.74) | (2.93) | (3.39) | |||

| 25 | 4.25 | 5.23 | 4.71 | 2.32 | 1.41 | 1.90 | .08 | −.02 |

| (n = 728) | ||||||||

| (3.78) | (4.16) | (3.99) | (3.28) | (2.43) | (2.95) | |||

| 26 | 5.15 | 6.86 | 5.81 | 1.77 | 1.13 | 1.53 | −.03 | .03 |

| (n = 104) | ||||||||

| (3.78) | (5.73) | (4.68) | (3.14) | (2.91) | (3.06) | |||

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001.

SD = standard deviation. Only ages at which there were at least 100 participants assessed are included in this table.

These sample sizes refer to participants who provided data on both depressive symptoms and alcohol use-related problems.

Means and standard deviations for alcohol use-related problems were derived from raw data; correlations with depressive symptoms were calculated using log-transformed alcohol problem variables. Mean numbers of depressive symptoms differed (p<.05) between males and females at all ages except age 26. Mean numbers of alcohol problems differed (p<.05) between males and females at all ages except 12, 16, and 26. Correlations between depressive symptoms and alcohol problems differed (p<.05) between males and females at ages 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 19, and 22 (but not at other ages).

Pearson correlation coefficients representing the cross-sectional associations between depressive symptoms and alcohol use-related problems are also presented in Table 1. Inspection of these values indicates that for males, there tended to be a curvilinear pattern of these correlation coefficients, with them tending to be fairly low in early adolescence and the mid-20s and higher in between (with a peak at age 16). In contrast, in females, these correlation coefficients were highest in early adolescence and then tended to decrease over time. These patterns indicate that (1) the cross-sectional associations between depressive symptoms and alcohol problems changed with age, and (2) these associations showed different patterns in males and females. Therefore, we next examined the influence of each problem on the trajectory of the other problem over time, considering gender as a possible moderator of these associations.

Trajectories of Alcohol Use-Related Problems

Parameter estimates, along with standard errors, the significance levels of t-values associated with each parameter estimate, and fit statistics for all models, are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Regression coefficients (standard errors) for models examining trajectories of alcohol use-related problems over timea

| Unconditional Growth Model | Model with Gender | Full Model (Gender and Depressive Symptoms) | Final Model | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Status: | ||||

| Genderb | .056*** | .0001 | .0041 | |

| (.011) | (.0178) | (.0092) | ||

| Depression | .0054*** | .0068*** | ||

| (.0022) | (.0011) | |||

| Gender × Depression | .0086*** | .0074*** | ||

| (.0028) | (.0014) | |||

| Rate of Change: | ||||

| Time (linear) | .0587*** | .0666*** | .0588*** | .0609*** |

| (.0018) | (.0026) | (.0042) | (.0020) | |

| Time (quadratic) | −.0019*** | −.0020** | −.0015*** | −.0016*** |

| (.0001) | (.0001) | (.0003) | (.0001) | |

| Gender × linear time | −.0135*** | −.0061 | −.0074*** | |

| (.0037) | (.0059) | (.0013) | ||

| Depression × linear time | .0007 | .0002 | ||

| (.0007) | (.0002) | |||

| Gender × Depression × linear time | −.0015§ | −.0011*** | ||

| (.0009) | (.0002) | |||

| Gender × quadratic time | −.00002 | −.0001 | ||

| (.0002) | (.0004) | |||

| Depression × quadratic time | −.00003 | |||

| (.00005) | ||||

| Gender × Depression × quadratic time | .00003 | |||

| (.0001) | ||||

| Fit Statistics: | ||||

| −2LL | 22762.2 | 22482.2 | 21778.2 | 21778.8 |

| BIC | 22851.7 | 22601.5 | 21957.1 | 21927.9 |

p<.10

p<.01

p<.001.

N=20,728.

The results in this table are derived from analyses including all participants (not limited to those who had used alcohol more than 2–3 times). Results of analyses including only alcohol users were quite similar; differences are noted in the text.

Gender was coded as follows: male=0, female=1.

Unconditional growth model

First, a linear growth model was fit to the data. As expected, it indicated that alcohol problems tended to increase with increasing age (linear slope=.0310). A quadratic model provided a significantly better fit to the data than the linear model (LRT difference = 2461.7, df = 4, p < .001). Therefore, the quadratic model was retained for future analyses. The negative value of the quadratic term indicated that with each squared value of age, the rate of change in the slope slowed, resulting in a slope that increased more steeply in adolescence and less steeply in early adulthood.

Model including gender as a predictor

Next, gender was entered as a time-invariant predictor. The model including gender fit the data significantly better than the unconditional growth model (LRT: difference = 280.0, df = 4, p < .001). Parameter estimates indicated that although females had slightly higher initial levels of alcohol problems, males experienced a steeper increase in alcohol problems over time than females did.

Model including depressive symptoms and gender as predictors (full model)

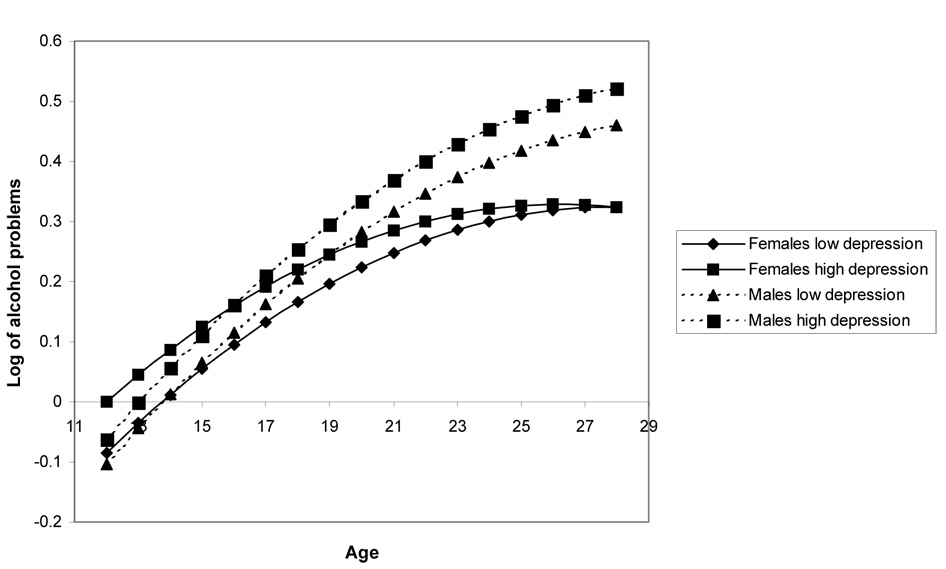

Next, depressive symptoms were added to the model as a time-varying predictor. The model including gender along with depressive symptoms fit the data significantly better than the model including only gender as a predictor (LRT: difference = 704, df = 4, p < .001). Examination of the parameter estimates indicated that depressive symptoms were associated with higher initial levels of alcohol problems, especially for females. There was also a trend-level (p = .08) interaction effect of gender and depressive symptoms on the linear slope such that males with higher levels of depressive symptoms experienced more rapid (steeper) increases in their alcohol problems than did females.

Final model

In an attempt to find a model that provided a good fit to the data yet was parsimonious, first, all terms from the full model that were not significant at the p<.05 level were removed. However, this model provided a significantly less-good fit to the data (LRT: difference = 261.5, df = 4, p < .001). Therefore, all terms except those relating to the quadratic slope were retained. This model provided a good fit to the data (LRT: difference = 0.6, df = 4, p = .96, and the BIC was smaller for this model, indicating a better fit).

This final model indicated that initial levels of depressive symptoms were associated with higher initial levels of alcohol problems, especially for females. However, males overall, and especially males with high levels of depressive symptoms, had a faster rate of growth in their alcohol-related problems, compared to females or males with low levels of depression.

A prototypical plot of this model is depicted in Figure 1. The trajectories depicted in this figure represent model-predicted trajectories for male and female participants with high (75th percentile) and low (25th percentile) levels of depressive symptoms.

Figure 1.

Longitudinal trajectories of alcohol use-related problems, by gender and level of depressive symptoms. The trajectories referring to participants with low depressive symptoms refers to participants at the 25th percentile of depressive symptoms; that referring to high depressive symptoms refers to participants at the 75th percentile of depressive symptoms. This figure is derived from analyses including all study participants (n=20,728).

Trajectories of Depressive Symptoms

Parameter estimates, along with standard errors, the significance levels of t-values associated with each parameter estimate, and fit statistics for all models, are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Regression coefficients (standard errors) for models examining trajectories of depressive symptoms over timea

| Unconditional Growth Model | Model with Gender | Full Model (Gender and Alcohol Problems) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Status: | |||

| Genderb | 1.4941*** | 1.1261*** | |

| (.1646) | (.1822) | ||

| Alcohol Problems | 2.7852*** | ||

| (.4619) | |||

| Gender × Alcohol Problems | 3.599*** | ||

| (.6385) | |||

| Rate of Change: | |||

| Time (linear) | .2754*** | .3079*** | .2668*** |

| (.0237) | (.0343) | (.0405) | |

| Time (quadratic) | −.0279*** | −.0272*** | −.0251*** |

| (.0015) | (.0022) | (.0026) | |

| Gender × linear time | −.0233 | .0310 | |

| (.0473) | (.0552) | ||

| Alcohol Problems × linear time | −.3865** | ||

| (.1203) | |||

| Gender × Alcohol Problems × linear time | −.6680*** | ||

| (.1704) | |||

| Gender × quadratic time | −.0037 | −.0049 | |

| (.0030) | (.0040) | ||

| Alcohol Problems × quadratic time | .0171* | ||

| (.0072) | |||

| Gender × Alcohol Problems × quadratic time | .0294** | ||

| (.0104) | |||

| Fit Statistics: | |||

| −2LL | 281701.3 | 280929.4 | 268560.0 |

| BIC | 281790.8 | 281048.7 | 268738.7 |

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001.

N=20,728.

The results in this table are derived from analyses including all participants (not limited to those who had used alcohol more than 2–3 times). Results of analyses including only alcohol users were quite similar; differences are noted in the text.

Gender was coded as follows: male=0, female=1.

Unconditional growth model

First, a linear growth model was fit to the data. It indicated that across the period from early adolescence through early adulthood, depressive symptoms tended to decrease slightly. A quadratic model provided a significantly better fit to the data than the linear growth model (LRT: difference = 709.6, df = 4, p < .001). Therefore, the quadratic model was retained for future analyses.

Model including gender as a predictor

Gender was next entered as a time-invariant predictor. The model including gender fit the data significantly better than the unconditional growth model (LRT: difference = 771.9, df = 4, p < .001). Parameter estimates indicated that females had higher initial levels of depressive symptoms.

Model including alcohol use-related problems and gender as predictors (full model)

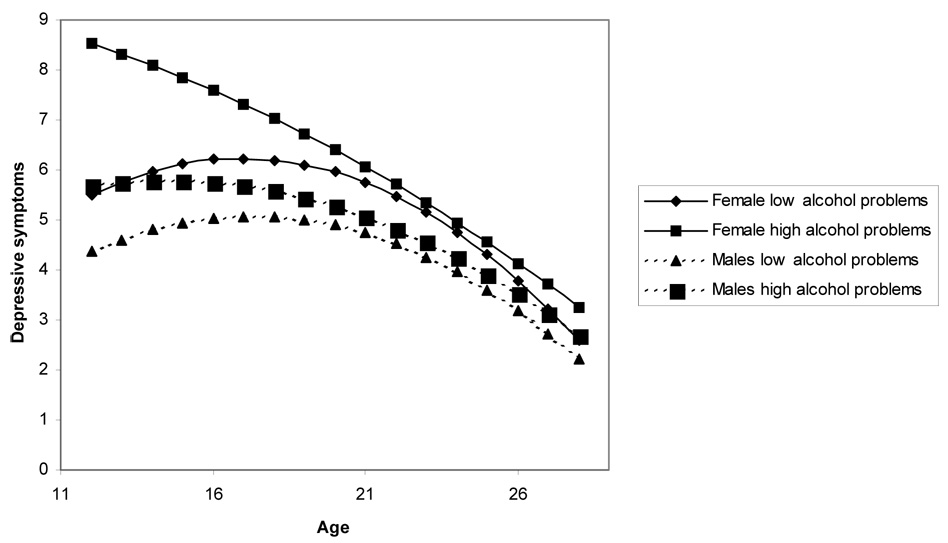

Next, alcohol problems were added to the model as a time-varying predictor. The model including gender along with alcohol problems fit the data significantly better than the model including only gender as a predictor (LRT: difference = 12369.4, df = 4, p < .001). Examination of the parameter estimates indicated that early alcohol problems were associated with higher initial levels of depressive symptoms, especially for females. However, depressive symptoms increased most rapidly for males with high levels of alcohol problems—that is, males with high levels of alcohol problems were especially likely to be increasing (or decreasing less than other participants) in their depressive symptoms at any given point in time. In addition, alcohol problems were associated with less curvature in the trajectory of depressive symptoms over time, especially for females. Thus, among participants with high levels of alcohol problems, and especially females with high levels of alcohol problems, the slope of depressive symptoms was more linear than among other participants such that although there was a large difference in depressive symptoms between participants with high and low levels of alcohol problems in early adolescence, by early adulthood the differences were small and relatively consistent.

Final model

Because the highest-order interaction term was significant, we retained the full model as the final model. A prototypical plot of this model is depicted in Figure 2. The trajectories depicted in this figure represent model-predicted trajectories for male and female participants who have high (75th percentile) and low (25th percentile) levels of alcohol problems.

Figure 2.

Longitudinal trajectories of depressive symptoms, by gender and level of alcohol use-related problems. The trajectories referring to participants with low alcohol problems refers to participants at the 25th percentile of alcohol problems; that referring to high alcohol problems refers to participants at the 75th percentile of alcohol problems. This figure is derived from analyses including all study participants (n=20,728).

Models including only participants who used alcohol

When analogous analyses were conducted including only participants who used alcohol, the results were quite similar. For analyses using depressive symptoms to predict alcohol problems, a final model using the same set of predictors was ideal. For analyses using alcohol problems to predict depressive symptoms, the quadratic terms were not significant; therefore, the best-fitting model included only the intercept and linear slope terms.

Discussion

The results of this study indicate that alcohol use-related problems and depressive symptoms have reciprocal, positive effects on each other during the period from early adolescence through early adulthood; however, these effects differ somewhat by gender and age. Overall, higher levels of depressive symptoms were associated with higher initial levels of alcohol problems (particularly among females), as well as faster increases in alcohol problems over time among males. Reciprocally, high levels of alcohol problems were associated with higher initial levels of depressive symptoms (particularly among females); however, while the trajectory of depressive symptoms among participants overall was curvilinear, high levels of alcohol problems were associated with less curvature in the slope of depressive symptoms over time (particularly among females), so although there was a large effect of alcohol problems in early adolescence, that effect was smaller by early adulthood.

Cross-sectional correlations between depressive symptoms and alcohol problems at each age illustrate these trends in a different way. These correlation coefficients showed a curvilinear pattern among males, being fairly low in early adolescence and the mid-20s and higher in between. Among females, these correlation coefficients were highest in early adolescence and tended to decrease over time. These findings complement the longitudinal findings summarized above by illustrating that in early adolescence, there were closer associations between these two problems among females, while later in development this was not the case.

There are many possible explanations for these longitudinal associations between depressive symptoms and alcohol problems. As noted by Swendsen and Merikangas (2000), it is likely that there are multiple pathways leading to comorbidity between these problems, and the population of individuals with both problems is probably quite heterogeneous. Some support for a common genetic diathesis has been found (e.g., Kendler et al., 1993; Nurnberger et al., 2002; Prescott et al., 2000; Preisig et al., 2001), though it is possible that any apparent shared genetic risk may actually be due to the genetic risk for antisocial personality disorder, which is frequently comorbid with both depression and alcohol dependence (Fu et al., 2002). Research integrating an examination of antisocial behavior along with depression and alcohol problems would be useful in teasing apart whether this joint comorbidity accounts for the apparent association between depression and alcohol problems. There are several ways in which neurobiological factors may link these disorders, and based on evidence from animal studies, substance use in adolescence may have more effects on the brain than substance use in adulthood (see Rao, 2006 for a review)—which could result in more risk for depression stemming from heavy alcohol use in adolescence, compared to heavy alcohol use in adulthood. Evidence also indicates that physical and sexual abuse may predispose adolescents to both depression and alcohol use disorders (Clark et al., 2003). In addition, it seems likely that each disorder influences risk for the other, whether because people sometimes drink heavily to cope with negative feelings or because the problems that go along with having an alcohol use disorder (e.g., social and occupational impairment) also are stressors that can precipitate a depressive episode.

The findings of the current study regarding the interactive associations between gender and age on associations between alcohol problems and depression are somewhat consistent with the existing literature. Two previous studies also found close associations between substance problems and depression-related problems in early adolescence, though these studies used a sample of boys only (i.e., Loeber et al., 1999; White et al., 2001). Specifically, Loeber and colleagues (1999) found that internalizing problems predicted substance use more strongly during pre-adolescence than during adolescence, and White et al. (2001) also reported that depressive symptoms were associated with alcohol use in early adolescence. Some studies of both genders that found closer associations between these problems among girls compared to boys used mid-adolescent samples (13–18 in Bukstein et al. [1992], 14–18 in Clark et al. [1997], 15–19 in Deykin et al. [1992]), and studies reporting no gender differences used mid-adolescent 22 through adulthood samples (17 in Marmorstein and Iacono [2003], 14–18 followed to age 24 in Rohde et al. [2001]).

The reasons for these gender differences are unclear. In early adolescence, rates of depression among girls increase at a markedly faster rate than among boys (e.g., Hankin et al., 1998); perhaps young girls are more likely to self-medicate their depressive symptoms by drinking alcohol, or perhaps some girls become depressed because they are either drinking or engaging in behaviors that may be associated with drinking (e.g., spending time with delinquent peers). Reciprocally, in early adulthood females may stop drinking heavily earlier than males (e.g., Labouvie, 1996), so depression may become less associated with alcohol problems among young women during that time period. Future research using more closely-spaced assessments and examining other potential mediating and moderating factors would be useful in explaining this pattern of associations.

This study confirms that clinicians should be aware that youth experiencing high levels of depression or alcohol-related problems are at risk for the development of the other problem. Given the prominence of the “self-medication” model of alcoholism, clinicians should be especially alert to the other direction of risk—alcohol problems predicting depression. These links are especially striking among early adolescent girls, so clinicians treating one of these problems among this group should make sure to assess and continually monitor clients for the development of the other problem. The cross-sectional correlations between these problems were somewhat less strong for women in early adulthood and for males in both early adolescence and early adulthood, so clinicians working with these age groups may be less likely to find these associations in their clients.

There were several limitations of this study. The measures of depressive symptoms and alcohol problems were continuous; clinically-significant syndromes were not examined. Therefore, it is not clear how these would apply to people with major depressive disorder or with alcohol abuse or dependence. Also, studies examining associations between these problems are complicated by the differing natures of depression and alcohol problems: specifically, depression is conceived of as an episodic disorder, while alcohol problems (particularly dependence) are relatively more stable (though individuals can have waxing and waning symptoms). In this study, depressive symptoms were assessed using a measure that asked about experiences during the past week; in contrast, alcohol problems were assessed using a measure that asked about experiences during the past twelve months. Therefore, problems that occurred at times other than the assessment windows for depressive symptoms and alcohol problems were missed, and problems that appeared to be concurrent could actually have reflected alcohol problems that preceded depressive symptoms within a single year. Cases in which depressive symptoms preceded (or occurred together with) alcohol problems but remitted by the week before the assessment would have been missed. Although unfortunate for analytic purposes, these differing assessment time frames may be appropriate given differences in memory for these problems. For example, a youth who had problems in school due to drinking in the past year would be likely to remember that event (e.g., being suspended), while a youth who felt sad (but was not severely depressed) in the past year may not remember that more transient feeling. Finally, due to the Wave 1 sampling strategy, these participants may not have been completely representative of adolescents in the United States (e.g., home-schooled adolescents and incarcerated adolescents were not included); the results cannot be generalized to the population of adolescents in the United States. Future research examining whether associations between these problems are similar in people from different racial/ethnic backgrounds and different socioeconomic strata would be useful.

This study contributed to our understanding of associations between depressive symptoms and alcohol problems in several ways. Its use of a sample whose ages spanned from early adolescence through early adulthood enabled us to examine associations across this entire developmental period and not just part of it (e.g., during adolescence). This age span, combined with the fact that the sample included both males and females, allowed us to detect the effects of gender during different developmental periods. The community-based nature of the sample allowed us to avoid the biases associated with treatment-seeking or high-risk samples. In addition, this study’s use of a growth curve analytic approach allowed for an examination of how each problem was likely to affect the trajectory of the other problem within individuals. This approach differs from most studies that examine whether one variable predicts another variable at a later time point and, therefore, provides a unique and informative perspective on the issue of how depressive and alcohol problems relate longitudinally.

The results of this study indicate that both gender and developmental stage are crucial factors to consider in examinations of associations between depressive symptoms and alcohol use-related problems. Although each type of problem tended to be associated with both increased levels of and increased growth in the other problem, the initial associations were stronger among females but growth in each problem was predicted more strongly among males. Future research examining the mechanisms behind these findings would be useful in developing effective prevention and treatment programs for adolescents and young adults with depressive and/or alcohol use-related problems.

Acknowledgments

This research uses data from Add Health, a program project designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris, and funded by a grant P01-HD31921 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 17 other agencies. Special acknowledgment is due Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design. Persons interested in obtaining data files from Add Health should contact Add Health, Carolina Population Center, 123 W. Franklin Street, Chapel Hill, NC 27516-2524 (addhealth@unc.edu). No direct support was received from grant P01-HD31921 for this analysis.

This study was supported by a research grant from the Alcoholic Beverage Medical Research Foundation and K01DA022456 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The author is grateful to Helene Raskin White for her helpful comments on earlier drafts of this article.

References

- Abraham HD, Fava M. Order of onset of substance abuse and depression in a sample of depressed outpatients. Compr Psychiatry. 1999;40:44–50. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(99)90076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alati R, Lawlor DA, Najman JM, Williams GM, Bor W, O’Callaghan M. Is there really a ‘J-shaped’ curve in the association between alcohol consumption and symptoms of depression and anxiety? Findings from the Mater-University Study of Pregnancy and its Outcomes. Soc Stud Addict. 2005;100:643–651. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovasso GB. Cannabis abuse as a risk factor for depressive symptoms. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:2033–2037. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.12.2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukstein OG, Glancy LJ, Kaminer Y. Patterns of affective comorbidity in a clinical population of dually diagnosed adolescent substance abusers. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1992;31:1041–1045. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199211000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Pitts SC, Prost J. Binge drinking trajectories from adolescence to emerging adulthood in a high-risk sample: Predictors and substance abuse outcomes. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70:67–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DB, De Bellis MD, Lynch KG, Cornelius JR, Martin CS. Physical and sexual abuse, depression and alcohol use disorders in adolescents: Onsets and outcomes. Drug Aclohol Depend. 2003;69:51–60. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00254-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DB, Kirisci L, Tarter RE. Adolescent versus adult onset and the development of substance use disorders in males. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;49:115–121. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00154-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DB, Pollock N, Bukstein OG, Mezzich AC, Bromberger JT, Donovan JE. Gender and comorbid psychopathology in adolescents with alcohol dependence. J Amer Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:1195–1203. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199709000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Erkanli A, Federman E, Angold A. Development of psychiatric comorbidity with substance abuse in adolescents: Effects of timing and sex. J Clin Child Psychol. 1999;28:298–311. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp280302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Angold A. Prevalence and development of pyschiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deykin EY, Buka SL, Zeena TH. Depressive illness among chemically dependent adolescents. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:1341–1347. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.10.1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Q, Heath AC, Bucholz KK, Nelson E, Goldberg J, Lyons MJ, True WR, Jacob T, Tsuang MT, Eisen SA. Shared genetic risk of major depression, alcohol dependence, and marijuana dependence: Contribution of antisocial personality disorder in men. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:1125–1132. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.12.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorenstein C, Andrade L, Zanolo E, Artes R. Expression of depressive symptoms in a nonclinical Brazilian adolescent sample. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50:129–137. doi: 10.1177/070674370505000301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY, Moffitt TE, Silva PA, McGee R, Angell KE. Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: Emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. J Abnorm Psychol. 1998;107:128–140. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Fraley RC, Lahey BB, Waldman ID. Is depression best viewed as a continuum or discrete category? A toxometric analysis of childhood and adolescent depression in a population-based sample. J Abnorm Psychol. 2005;114:96–110. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KM, Florey F, Tabor J, Bearman PS, Jones J, Udry JR. The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health: Research Design [WWW document] 2003 URL: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design.

- Hasin DS, Liu X, Alderson D, Grant BF. DSM-IV alcohol dependence: A categorical or dimensional phenotype? Psychol Med. 2006;36:1695–1705. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706009068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry B, Feehan M, McGee R, Stanton W, et al. The importance of conduct problems and depressive symptoms in predicting adolescent substance use. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1993;21:469–480. doi: 10.1007/BF00916314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettema JM, Prescott CA, Kendler KS. The effects of anxiety, substance use and conduct disorders on risk of major depressive disorder. Psychol Med. 2003;33:1423–1432. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703008365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Heath AC, Neale MC, Kessler RC, Eaves LJ. Alcoholism and major depression in women: A twin study of the causes of comorbidity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:690–698. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820210024003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC. Epidemiology of women and depression. J Affect Disord. 2003;74:5–13. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00426-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III--R psychiatric disorders in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labouvie E. Maturing out of substance use: Selection and self-correction. J Drug Issues. 1996;26:457–476. [Google Scholar]

- Li T-K, Hewitt BG, Grant BF. Alcohol use disorders and mood disorders: A national institute on alcohol abuse and alcoholism perspective. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:718–720. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M, White HR. Developmental aspects of delinquency and internalizing problems and their association with persistent juvenile substance use between ages 7 and 18. J Clin Child Psychol. 1999;28:322–332. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp280304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmorstein NR, Iacono WG. Major depression and conduct disorder in a twin sample: Gender, functioning, and risk for future psychopathology. J Amer Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42:225–233. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200302000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurnberger JI, Foroud T, Flury L, Meyer ET, Wiegand R. Is there a genetic relationship between alcoholism and depression? Alcohol Res Health. 2002;26:233–240. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patten SB, Wang JL, Williams JVA, Currie S, Beck CA, Maxwell CJ, el-Guebaly N. Descriptive epidemiology of major depression in Canada. Can J Psychiatry. 2006;51:84–90. doi: 10.1177/070674370605100204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preisig M, Fenton BT, Stevens DE, Merikangas KR. Familial relationship between mood disorders and alcoholism. Compr Psychiatry. 2001;42:87–95. doi: 10.1053/comp.2001.21221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prescott CA, Aggen SH, Kendler KS. Sex-specific genetic influences on the comorbidity of alcoholism and major depression in a population-based sample of US twins. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:803–811. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.8.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prescott CA, McArdle JJ, Hishinuma ES, Johnson RC, Miyamoto RH, Andrade NN, Edman JL, Makini GK, Nahulu LB, Yuen NYC, Carlton BS. Prediction of major depression and dysthymia from CES-D scores among ethnic minority adolescents. J Amer Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37:495–503. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199805000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rao U. Links between depression and substance abuse in adolescents: Neurobiological mechanisms. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31:S161–S174. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao U, Daley SE, Hammen C. Relationship between depression and substance use disorders in adolescent women during the transition to adulthood. J Amer Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:215–222. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200002000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rende R, Slomkowski C, Lloyd-Richardson E, Stroud L, Niaura R. Estimating genetic and environmental influences on depressive symptoms in adolescence: Differing effects on higher and lower levels of symptoms. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2006;35:237–243. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3502_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde P, Lewinsohn PM, Kahler CW, Seeley JR, Brown RA. Natural course of alcohol use disorders from adolescence to young adulthood. J Amer Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:83–90. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200101000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD. Using SAS PROC MIXED to estimate multilevel models, hierarchical models, and individual growth models. J Ed Behav Statistics. 1998;24:323–355. [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis: Modeling Change and Event Occurrence. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Steuber TL, Banner F. Adolescent smoking and depression: Which comes first? Addict Behav. 2006;31:133–136. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swendsen J, Merikangas K, Canino G, Kessler R, Rubio-Stipec M, Angst J. The comorbidity of alcoholism with anxiety and depressive disorders in four geographic communities. Compr Psychiatry. 1998;39:176–184. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(98)90058-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Burton EM, Shaw H. Prospective relations between bulimic pathology, depression, and substance abuse: Unpacking comorbidity in adolescent girls. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:62–71. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.1.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner JL, Reinherz HZ, Beardslee WR, Fitzmaurice GM, Leis JA, Berger SR. Change in prevalence of psychiatric disorders from ages 21 to 30 in a community sample. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195:298–306. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000261952.13887.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udry JR. Waves I & II, 1994–1996; Wave III, 2001–2002 [machine-readable data file and documentation] Chapel Hill, NC: Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 2003. The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health) [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Wolk S, Goldstein RB, Moreau D, Adams P, Greenwald S, Klier CM, Ryan ND, Dahl RE, Wickramaratne P. Depressed adolescents grown up. JAMA. 1999;281:1707–1713. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.18.1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Xie M, Thompson W, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Psychopathology as a predictor of adolescent drug use trajectories. Psychol Addict Beh. 2001;15:210–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA. The four alcoholisms: A developmental account of the etiological process. Nebr Symp Motiv. 1986;34:27–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]