Abstract

Data obtained from two waves of a longitudinal study of 671 rural African American families, with an 11-year-old preadolescent, were examined to test pathways through which racial and ethnic socialization influence youth's self-presentation and academic expectation and anticipation through the enhancement of youth self-pride. Structural equation modeling analyses indicated that racial and ethnic socialization was linked with youth's expectation and anticipation for academic success, through youth self-pride, including racial identity and self-esteem, and academic self-presentation. The results highlight the need to disaggregate racial and ethnic socialization in order to better understand how these parenting domains uniquely forecast youth self-pride, as well as their orientation to education and academic success.

Keywords: parenting, racial socialization, rural, racial identity, academic self-presentation

The study presented in this article tests a heuristic model, developed by the Study Group on Culture, Race, and Ethnicity Culture and Race, for understanding the pathway through parenting practice unique to African American parents, in particular the combination of racial and ethnic socialization, forecasts youths’ orientation to education, an important developmental goal parents have for children within this community (Brody & Stoneman, 1992; Hill, 2001). In this endeavor, we examined the extent to which racial and ethnic socialization influence rural African American youths’ self-pride, consisting of racial identity and self-esteem, and the role of youth self-pride in forecasting whether youth would be willing to hide his or her abilities in school to “fit” in with peers. Subsequently, as educational performance and school connectedness are juxtaposed with often the salience of racial identity, we pose the question, “how does a strong sense of self-pride encourage youth to not engage in behaviors that reflect masking their academic abilities in order to maintain a sense of collective identity?” (Ogbu, 2004). Finally, how does the concealment of ones’ academic strengths influence teachers’ perceptions of youths’ academic competence and rural African American parents’ perceptions of their sons and daughters’ academic performance?

We focus specifically on rural African American families because these families often are confronted with the additional burden of encouraging their children to do well in school as an avenue to overcome the challenges associated with rearing children in economically disadvantaged environments. Many of these children grow up in communities that lack the structural resources afforded to families who are rearing youth in urban settings (Proctor & Dalaker, 2003), including restricted range of employment opportunities, vast distances from businesses and services, limited public transportation, and a lack of recreational facilities for children and adolescents. For example, the families who participated in the current study live in small towns and communities in rural Georgia, in which poverty rates are among the highest in the nation and unemployment rates are above the national average (Proctor & Dalaker, 2003). Thus, with limited discretionary income, for rural families, encouraging youth to link academic success as a way out of poverty may be more challenging than those rearing children in urban areas where there is a greater likelihood of exposure to .

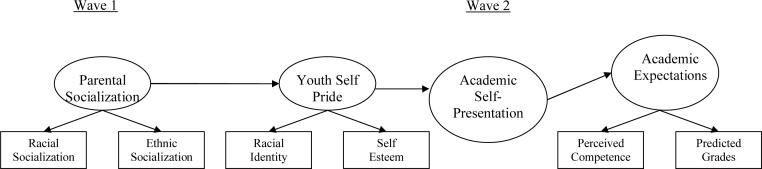

On the other hand, African Americans, regardless of geographic residence or economic status, have historically viewed academic achievement as an avenue for escaping poverty and gaining social mobility (Billingsley, 1968). Social scientists, however, still know little about the mechanisms and dynamics of childhood socialization in African American families that promote academic orientation and engagement in their children (Brody et al., 2002; 2004; Murry & Brody, 1999; Murry, Brody et al., 2005). Knowledge about this process could be enhanced by longitudinal investigations that identify causal links between specific domains of parenting, e.g., racial and ethnic socialization, that African Americans engage foster positive identity development in their children as well as transmit messages that doing well in school can, indeed, be beneficial in terms access to better occupations and better living conditions. Thus, the present study was designed to determine the extent to which parenting strategies that are unique to the ecological contexts of African Americans youth, in particular racial and ethnic socialization, make unique contributions and operate together to forecast youths’ academic outcomes. We hypothesized that adaptive racial and ethnic socialization would be indirectly linked to youths’ academic outcomes over time through the youths’ self-pride. We also hypothesized that positive self-pride, specifically elevated racial identity pride and positive self-esteem, would forecast academic self-presentation, such that youth would report less inclination to engage in practices that would camouflage their academic potential. Reducing academic self-presentation practices would, in turn, promote teachers’ perceptions of youths’ competence and parents’ perception that their children would do well in school. The conceptual model that guided this study is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The conceptual model linking socialization with self-pride, academic self-presentation and academic success.

Conceptual Model

The theoretical underpinnings of this current investigation are based on our longitudinal empirical research with rural African American families (Brody, Murry et al., 2002; Murry & Brody, 1999), empirical evidence from various studies of racial socialization and racial identity (Hughes & Chen, 1997; Hughes & Johnson, 2001; Smith & Brookins, 1997), and tenets of the competence model of family functioning (Waters & Lawrence, 1993). The competence model of family functioning was selected because it describes many of the processes that African American parents engage to rear competent children. Inherent in this model are the assertions that parenting behaviors represent adaptive responses to environmental challenges, and that parents who live in challenging environments possess strengths that account for the variation in competence among children living in high-risk environments (Murry, Brody et al., 2005). These theoretical explanations were utilized to test tenets of Ogbu's theory of oppositional culture that have been put forth to explain how racism influences African American youths’ academic outcomes (1986). Emphasized in this theory is that the consequences of racism and discrimination in White-dominated institutions, including schools, for African American youths, increase their vulnerability to reject those institutions that do not portray or embrace their own experience (Thompson et al., 2000). Further, this theory contends that the sense of marginalization may evoke heighten sense of disengagement from White-dominated social institutions, such that African American youth may adopt a stance of cultural inversion, camouflaging their ability to do well to avoid criticism from their peers for “acting White” (Fordham & Ogbu, 1986; Fries-Britt, 1998; Graham, Taylor, & Hudley, 1998; Majors & Billson, 1993; Ogbu, 1986, 1992, 1993). These reactionary behaviors are more likely to occur when: 1) youth perceive a need to resist what they view as unfair power structure; 2) youth are experience a sense of oppressed and disadvantaged because of their skin color or social class; or 3) youth perceives that embracing the dominant culture means rejecting their own (Alpert, 1991; Fordham, 1996; Mirón & Lauria, 1998; Spencer, Noll, Stoltzfus, & Harpalani, 2001). In keeping with these theoretical models and empirical findings, we contend that studying racial and ethnic socialization can help explain why some African American youth are able to successfully navigate the consequences of racism and discrimination to achieve academically. In the following section, we describe the links among aspects of racial and ethnic socialization that have implications for promoting positive youth self-pride that we forecast will dissuade rural African American youth from engaging in practices that would camouflage their academic potential. We begin the following section by providing a brief overview of studies linking academic outcomes to race related issues.

Associations among Academic Outcomes and Racial Marginalization

African American youth frequently underachieve in school as compared their European American counterparts (Ford & Harris, 1992; McAdoo, 1997). Evidence of academic discrepancies is further implicated by statistics of high school dropout rates and low postsecondary attendance. For example, African American youth in Georgia experience higher dropout rates, 9.4% compared to 5.7% for Caucasian youth. In 2001, 70% of high school students across the United States graduated within 4 years compared to 46% among African American students in Georgia (Greene, 2001). Further, in Georgia, only 12% of rural African American high school graduates attend a 2- or 4-year college or university (Boatright & Bachtel, 2000). While reasons for educational discrepancies among African American youth remain unclear, Ogbu (1986; 2004) has offered several plausible theoretical explanations. He contends that racial discrimination against African Americans may negatively affect African American youths’ perception of the overall intent and regard of educational institutions, which in turn create barriers to their academic success (1986, 1994, 1997). Further, African American youth encounter stress and racialized pressure in White-dominated institutions, including school, to take on a Eurocentric perspective which may run counter to their own experience (Thompson, Anderson, & Bakeman, 2000) and sense of identity. These experiences may facilitate the development of an ambivalent academic orientation, as schools may be perceived as “White institutions” thereby reducing the likelihood of the internalization of educational goals and standards. The culmination of these negative and oppressive experiences may explain why African American youth may begin to see academic achievement as the prerogative of White Americans. What is more, African American youth may respond to the negative images that they receive from society about their inability to achieve academically by disengaging from school as an adaptive way to protect their collective identity and self-worth (Fordham & Ogbu, 1986; Ogbu, 1986; 1993). These reactionary responses, in turn, contribute to compromised school performance, jeopardizing their potential success (Ogbu, 1997).Moreover, recognizing disparities in returns on educational investment, African American youth may adopt a philosophy of cultural inversion, promoting the idea that “that which is for White people is not for African Americans,” and those that betray this ideology may be perceived as “Uncle Toms” (Ogbu, 1986). As a result of this perspective, attempting to succeed in school could be perceived by peers as a denouncement of heritage and an act of betrayal against one's community. To avoid criticism from their African American peers for “acting White” and to gain acceptance from their African American peers, youth may attempt to camouflage their academic ability, and consequently jeopardize their success (Fries-Britt, 1998; Graham, Taylor, & Hudley, 1998; Majors & Billson, 1993; Ogbu, 1992). Ogbu (1986) characterized this behavior as academic self-presentation. Noteworthy is that while youth may be staging this academic self-presentation for the benefit of other African American youth, their peers may not be the only ones receiving messages about their academic engagement and competence. For example, teachers and parents may also notice these displays, and as a result, underestimate youths’ competence and school success. In keeping with the theory of the looking glass self, we contend that if youths’ teachers and parents perceive them to have low competence as a result of their academic self-presentation, youth may internalize this perception and this may become a self-fulfilling prophecy, school disengagement and low academic performance.

Linking Racial and Ethnic Socialization to Academic Self-Perception

Unlike ethnic majority parents, African American parents have the added responsibility of teaching their children how to manage their lives and to interpret their experiences in a society in which they and their parents are often devalued (Hughes & Chen, 1997; Murry, 2000). Parental messages about race and ethnicity serve a protective function in adolescent identity development. Studies have consistently demonstrated that African American parents have the ability to buffer their children from negative societal messages about their race; including messages from their peers that may devalue school (Brody, Kim, Murry, & Brown, 2005; Murry & Brody, 2002). Yet, despite the widespread recognition of African American youths’ academic underachievement, there is limited recognition of the powerful factors that protect rural African American youth from internalizing negative images about their race originate in the family environment, particularly in parents’ caregiving practices (Brody, Dorsey, Forehand, & Armistead, 2002; Brody et al., 2001; Murry & Brody, 1999). Such parenting behaviors also foster resilience in youth, as youths who receive explicit messages about race relations are more likely to reject stereotypic images of their race (Smith & Brookins, 1997).

While parent's race related messages to children may take many different forms, including promotion of mistrust, preparation for bias, and cultural pride (Peters, 1985; Thornton, Chatters, Taylor, & Allen, 1990), few studies have examined the specific effects of these distinct race related communication messages on youths developmental outcomes. It seems apparent that various messages can induce differential responses. For example, messages that are geared toward dealing with racial barriers can induce distrust, hopelessness, and a sense of victimization, whereas other messages that focus on the management of prejudice and discrimination can be empowering , and still others that emphasize a sense of pride in being African American (Hughes & Chen, 1997) can engender positive self-perception. What is apparent, however, according to Stevenson and colleagues (1996), the most adaptive approach to parental race related socialization involves teaching children about the realities of racial oppression while emphasizing the possibility of achieving success despite these obstacles (Stevenson et al., 1996). In addition, we contend that to the extent that African American parents convey messages of acceptance and racial pride to their children, youth will report elevated positive racial identity, heightened self-esteem, that will in turn increase the likelihood that youth will reject stereotypic images about their race (Smith & Brookins, 1997), including labels that link school failure and underachieving with what it means to be “an African American.”

In fact, by viewing parents as pivotal in the process of connecting youths’ perception of racial awareness, identity development, and school performance may a key factor in explaining the contradictory findings regarding racial identity and African American academic achievement. In particular, whereas, Ogbu and Fordham reported that African American students, who were academically successful, disassociated with their racial group, or, as they contend, these youths developed a “raceless persona”(Fordham, 1988; Fordham & Ogbu, 1986), both Fordham (1988) and Sanders (1997) found evidence of high achieving African American youth who did not reject their racial group but were more likely to have heightened racial pride. Such youth viewed stereotypic images of underachieving African Americans with low school bonding, as challenges to overcome. These myths motivated them to perform well in school as a way of challenging negative societal views. Moreover, high academically achieving youth associated their success with the strengths and success of being an African Americans (Fordham & Ogbu, 1986). Clarifying this contradiction served as one of the impetus for the present study. Thus, in the current study, we proposed that parents who convey messages about the realities of racial oppression, while emphasizing a sense of pride connected to their African American heritage and the possibility of achieving success despite these obstacles (Stevenson, Reed, & Bodison, 1996), will promote self-pride, which included racial identity and self-esteem in their children.

Youth Self-Pride

Parental race-related socialization has been demonstrated to enhance youths’ sense of self-pride (Murry & Brody, 2002; Murry et al., 2005), further supporting the centrality of parenting to adolescent identity development (Murry & Brody, 2004). Although the complex process of developing a sense of self as African has yet to be unraveled, it has been well documented that when parents teach their children about race related issues, their children exhibit elevated racial pride, strong racial identity (Marshall, 1995; Miller, 1999; Murray & Mandara, 2002), and heightened self-esteem (Murry, 2000; Stevenson et al., 1996). We include both racial identity and self esteem because Twenge and Crocker (2002), concluded from their meta-analysis of research on race and self-esteem, that, in general, African Americans report higher personal self-esteem than do members of other racial groups. Although reasons for these findings are unclear, several scholars have noted that when racial identity is salient to one's self-definition and is also viewed as positive, youth not only have elevated self-worth, but also report higher academic achievement (Bowman & Howard, 1985; Miller & MacIntosh, 1999; but see Marshall, 1995). Moreover, Phinney and Chavira (1995) contend that African American youth with elevated self-esteem engaged in proactive coping when exposed to racially discriminatory incidences, whereas those with low self-esteem tend to respond to stereotypic portrayal of their racial group by engaging in both internalizing and externalizing behavior, including anger, depression, and apathy. We hypothesized that youth self-pride would decrease the use of academic self-presentation among rural African American youth, which we predict would be associated with teachers’ and parents’ perceptions of youths’ academic competence and success.

Moderational Effect Of Gender

Extant studies have consistently shown gender disparities in academic performance of African American males and females, with females generally outperforming males (Ford & Harris, 1997; Hare, 1985; Saunders, Davis, Williams, & Williams, 2004), including reporting higher educational goals, more favorable academic attitudes, and being more future oriented (Greene, 1990; Greene & Wheatley, 1992; Sundbergy, Poole, & Tyler, 1983). Noteworthy is that, to our knowledge, no studies have considered whether ethnic and racial socialization have differential effect on rural African American sons and daughters’ racial identity and self-esteem. Fur, the implication of the protective nature of both racial and ethnic socialization for sons and daughters’ academic success has not been investigated. To address these gaps, we posed and tested uninvestigated ancillary hypothesis that considered the extent to which ethnic and racial socialization, as well as youth self-pride would operate differently for rural African American males and females.

Summary of Present Study

A sample of rural African American families with an 11-year-old child was assessed at two intervals in order to document the longitudinal impact of ethnic and racial socialization on the academic outcomes of middle school age youth as they transition into early adolescence. Including these two time periods will allow an examination of changes in youths’ educational and developmental transitions, given that peer influence become more salient during the transition from elementary-level to middle and junior high school. Further, the decision to examine parental socialization exposure during middle school age years on youth academic competence was informed by developmental research. In particular, past research has established that close family relationships, academic achievement, and peer group acceptance are markers of competence during preadolescence and adolescence (Masten & Coatsworth, 1998). The development of these competencies has prognostic significance for the accomplishment of developmental tasks during early and late adolescence (Cairns & Cairns, 1995; Caspi & Bem, 1990; Donovan, Jessor, & Costa, 1991; Werner & Smith, 1992), such staying in school, as well as obtaining and maintaining employment (Caspi, Elder, & Bem, 1987; Layton & Eysenck, 1985; Masten & Coatsworth, 1998).

As the conceptual model in Figure 1 illustrates, we hypothesized direct and indirect paths through which ethnic and racial socialization contributes to youths’ academic success. We posited that adaptive racial and ethnic socialization would be indirectly linked to youths’ academic outcomes over time through the youths’ self-pride. We also predicted that positive youth self-pride, specifically racial identity and self-esteem, would forecast academic self-presentation, such that youth who report elevated self-pride would be less inclined to engage in practices that would camouflage their academic potential. Reducing the engagement in academic self-presentation practices would, in turn, foster positive teachers’ perceptions of youths’ competence, as well as evoke positive influence on parents’ perception that their children's ability to do well in school. The hypotheses were tested using structural equation modeling (SEM), which allowed multiple predictions to be evaluated in a single analysis while controlling for measurement error.

Method

Participants

African American mothers and their 11-year-old children (M = 11.2 years) who resided in nine rural Georgia counties participated in the study. Although 75% of the mothers worked an average of 39.4 hours per week, 46.3% of the total sample lived below federal poverty standards and another 50.4% lived within 150% of the poverty threshold. The families were representative of the areas in which they lived (Boatright & Bachtel, 2002) and are best described as working poor. Their economic level reflected the dominance of low-wage, resource-intensive industries in these areas.

Schools in the nine counties provided lists of 11-year-old students, from which families were selected randomly. Of the randomly selected families, 671 were participated in the study, resulting in a recruitment rate of 65%. The retention rate for families providing data in all waves of collection was 94%. In 53.6% of these families, the target child was female. The families who completed the study had an average of 2.7 children. Of the mothers, 33.1% were single, 23.0% were married and living with their husbands, 33.9% were married but separated from their husbands, and 7.0% were living with partners to whom they were not married. Of the two-parent families, 93.0% included both of the target child's biological parents. The mothers’ mean age was 38.1 years. A majority of the mothers, 78.7%, had completed high school. The families’ median household income was $1,655.00 per month.

Procedures

Center staff contacted the families who had been selected randomly from the lists that the schools provided. Community liaisons followed up this initial contact. Chosen on the basis of their extensive social contacts and positive community standing, the community liaisons were African American community members who resided in the counties in which the participants lived and maintained connections between the University research group and the communities. The liaisons sent letters to the families, and then telephoned the children's primary caregivers to describe the pretest assessment and answer any questions the caregivers asked. Families who were willing to participate in the study were told that a field researcher from the University would contact them to schedule a data collection visit in the family's home. Each family was paid $100 at the completion of each wave of data collection.

To enhance rapport and cultural understanding, African American students and community members served as field researchers at both data collection waves. Prior to data collection, the visitors received 27 hours of training in administering the protocol. The instruments and procedures were developed and refined with the help of a focus group of 40 African American community members who were representative of the population from which the sample was drawn. Both the focus groups and the community liaisons are part of a partnership process between the researchers and the communities in which the research is conducted; this process has been described in detail elsewhere (Brody, Murry, Kim, & Brown, 2002; Murry & Brody, 2004).

Two waves of data were collected an average of nine months apart. During each wave, one home visit lasting 2 hours was made to each family. Informed consent forms were completed at both waves. Mothers consented to their own and the youths’ participation, and youths assented to their own participation. At each home visit, field researchers administered self-report questionnaires to the mothers and youths in an interview format that eliminated literacy concerns. Each interview was conducted privately, with no other family members present or able to overhear the conversation.

Measures

Parental racial and ethnic socialization

Caregivers reported their use of the two components of socialization in Wave 1 via the Cultural Heritage (5 items) and Warnings about Discrimination (6 items) subscales of the Racial Socialization Scale (Hughes & Johnson, 2001). Caregivers rated the items on a scale ranging from 1 (never) to 3 (three to five times). The stem for each question is, “How often in the past month have you...” with the stem followed by specific socialization behaviors. Racial socialization behaviors include “talked with your child about discrimination or prejudice against your racial group” and “explained to your child something you saw on TV that showed poor treatment of your racial group.” Ethnic socialization behaviors include “talked to your child about important people or events in the history of your racial group” and “done or said things to encourage your child to read books concerning the history or traditions of your racial group.” Cronbach's alphas were .85 for racial socialization and .82 for ethnic socialization.

Youth self-pride

The youth self-pride construct, assessed at Wave 2, was composed of two indicators, racial identity and self-esteem. Youths provided self-reports of their racial identity using the Inventory of Black Identity (Smith & Brookins, 1997), which consists of 15 items rated on a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Items include “Being Black is an important part of my self-image,” “I often regret that I am Black” (reverse scored), and “I believe that, because I am Black, I have many strengths.” Cronbach's alpha was .75. Youths reported their self-esteem using the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965), a widely used measure of self-concept that is composed of 10 items rated on a scale ranging from 1 (completely false) to 5 (completely true). Items include “I take a positive attitude toward myself” and “I wish I could have more respect for myself” (reverse scored). Cronbach's alpha was .75.

Youth academic self-presentations

At Wave 2, adolescents provided self-reports of ability-camouflaging behaviors using the 4-item Impression Management subscale of Arroyo and Zigler's (1995) Racelessness Scale. Rated on a scale ranging from 1 (untrue) to 3 (very true), the items include “I never let my friends know when I get good grades in school,” “I sometimes do things I really don't like just so other students will like me,” “I feel like I must act less intelligent than I am so other students will not make fun of me,” and “I could probably do better in school, but I don't try because I don't want to be called a nerd.” Cronbach's alpha was .53. We recognize that this coefficient estimate is low; because our decision to maintain this measure in our analysis was informed by previous research supporting its theoretical relevance to the issues examined in the current study. In addition, an examination of the inter-item correlations indicates that they are moderately high, suggesting that the items are measuring the same underlying construct. Further, while much emphasis has been placed on the importance of yielding measures with high reliability, there is little guidance on what constitutes acceptable or insufficient reliability (Helms, et al., 2006; Peterson, 1994).

Adult academic expectations

Two indicators from teachers and one from mothers were used to index adults’ perceptions and expectations regarding youths’ academic performance and potential; these were assessed at Wave 2. Teachers reported their perceptions of adolescents’ academic competence using the seven-item Academic Competence subscale of the Perceived Competence Scale for Children (Harter, 1982). For simplicity in rating and scoring this instrument, the response set was altered from the original two-step, forced-choice format to a rating scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4(always). Items included, “This child is very good at his/her schoolwork,” and “She/he does well in class.” Cronbach's alpha was .77. Mothers stated the grades they expected the youths to receive on their next report cards in English, social studies, science, and math, based on their performance to date. Responses ranged from 1 (F) to 5 (A).

Results

Plan of Analysis

The hypothetical model presented in Figure 1 was analyzed via SEM using Amos 5.0 software (Arbuckle, 2003), which uses the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation method. FIML does not delete cases for which data are missing from one or more waves of data collection, nor does it delete cases for which data are missing for a variable within a wave of data collection. This method thus avoids potential problems, such as biased parameter estimates, that are more likely to occur if pairwise or listwise deletion procedures are used to compensate for missing data (Arbuckle & Wothke, 1999). Table 1 presents the correlation matrix, means, and standard deviations for the SEM variables; Figure 2 presents the results of the test of the structural model.

Table 1.

Intercorrelations, means, and standard deviations for all study variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlations | |||||||

| 1. Racial Socialization | -- | ||||||

| 2. Ethnic Socialization | .57* | -- | |||||

| Youth Self-Pride | |||||||

| 3. Racial Identity | .10* | .12* | -- | ||||

| 4. Self Esteem | .06 | .08* | .55* | -- | |||

| 5. Academic Self Presentation | −.02 | −.01 | −.35* | −.40* | -- | ||

| Academic Expectations | |||||||

| 6. Teachers' Report of Academic Competence | .01 | −.01 | .18* | .26* | −.32* | -- | |

| 7. Parents and Teachers' Predicted Grades | .03 | .04 | .21* | .23* | −.24* | .36* | -- |

| M (SD) | |||||||

| Total Sample | 9.97 (3.09) | 9.29 (2.70) | 56.82 (6.19) | 42.35 (6.24) | 5.38 (1.63) | 15.96 (3.18) | 16.64 (2.39) |

| Females | 9.86 (3.15) | 9.11 (2.84)+ | 56.93 (6.33) | 42.70 (6.17) | 5.20 (1.55)* | 16.48 (3.28)* | 16.92 (2.37)* |

| Males | 10.06 (3.02) | 9.50 (2.52) | 56.74 (5.99) | 42.00 (6.32) | 5.59 (1.69) | 15.33 (2.96) | 16.30 (2.37) |

p ≤ .05, + p ≤ .10

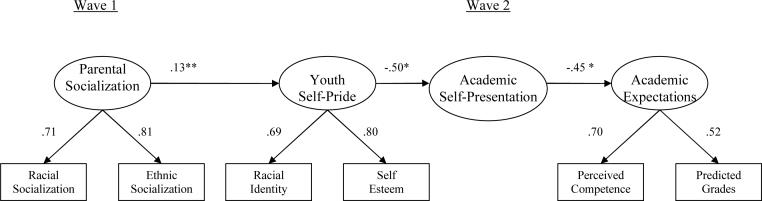

Figure 2.

Results of the tests of the structural model, with factor loadings of the manifest variables on their respective latent constructs

Measurement Model

All indicators loaded significantly on their latent constructs, supporting the measurement model's adequacy. All loadings (λ) of manifest indicators on corresponding latent constructs were significant at α = .05 and all the coefficients were above .50, demonstrating the model's adequacy. As expected, the positive, significant factor loadings of racial socialization and ethnic socialization confirmed their validity as indexes of the latent construct measuring parental socialization. The positive, significant loadings of racial socialization and self-esteem indicate their adequacy as indicators of the youth self-pride construct. Finally, the positive loading of teachers’ perceived academic competence and parents’ grade expectations confirmed their utility as indicators of the construct of adult academic expectations.

Structural Model

After determining that the measurement model fit the data as specified, we tested the structural model. The overall model fit was good: χ2(12, N = 671) = 28.66, p ≤ .01. Because the sample in this study was relatively large, we considered alternative fit indexes; these confirmed the model's acceptable fit to the data. According to (Arbuckle & Wothke, 1999), a χ2/df ratio between 1 and 3 indicates a good model fit; the χ2/df ratio for this analysis was 2.39. The comparative fit index (CFI) was .98, and the Root Mean Square of Approximation (RMSEA) was .05 (90% confidence interval [CI] .03; .07). As hypothesized, adaptive racial and ethnic socialization practices at Wave 1 were significantly and positively associated with youth self-pride 1 year later, at Wave 2 (β = .13, p ≤ .05). Youths whose mothers conveyed messages about the realities of racial oppression along with discussions about ways to succeed despite these obstacles and pride in their families’ African American heritage were more likely to report positive racial identity and elevated self-esteem than were youths whose mothers did not communicate these messages. This finding supported our hypothesis that African American parents serve as major socializing agents in youths’ development of both racial identity and self-esteem.

Consistent with our indirect effect hypothesis, the association between Wave 1 ethnic and racial socialization and youths’ Wave 2 academic self-presentation was mediated through youths’ Wave 2 youth self-pride. The predicted direct path between self-pride and academic self-presentation also emerged, a significant and negative association (β = −.50, p ≤ .05). Consistent with the theoretical model, youths who reported positive racial identity and elevated self-esteem were less likely than those who did not report these outlooks to camouflage their academic abilities to gain peer acceptance. Finally, teachers were likely to perceive youths as academically competent and parents expected youths to receive good grades in school when youths were disinclined to engage in negative academic self-presentations (β = −.45, p ≤ .05). This finding is consistent with our hypothesis that youths’ self-pride and academic self-presentations can influence significant others’ perceptions and expectations concerning youths’ scholastic abilities. Given the numerous studies showing significant disparities in academic performance between African American male and female youths (Ford & Harris, 1997; Saunders et al., 2004), we used a multigroup analysis in AMOS 5.0 to test the hypothetical model separately for boys and girls. No gender differences emerged for our sample.

Discussion

Prior research addressing identity development among African American youths beyond race-related issues has been sparse, and we know of no studies in which associations among both racial and ethnic socialization parenting behaviors, racial self-pride (e.g., racial identity and self-esteem), and academic self-presentation have been addressed with rural African American families. Guided by a central model designed and developed by the Study Group on Race, Culture, and Ethnicity (SGRCE), the present study addressed these issues by examining the developmental pathways by which parents’ use of socialization about race and ethnicity when their children are in middle school serves as a foundation for the development of a positive sense of self and self-presentation as youth transition into early adolescence. As illustrated in the central model guiding this Special Issue, parental ethnic and racial socialization is hypothesized to indirectly influence youth adjustment and development through its affect on youths’ self-esteem and racial/ethnic identity. Our findings provide empirical evidence in support of the appropriateness of this theoretical model for understanding the mechanism through which both racial socialization and ethnic socialization can serve a protective role in dissuading youth from concealing their academic strengths. Further, that such efforts have a spillover effect to influence both parents and teachers’ perceptions of youths’ academic competence and in turn affect youths actual academic performance.

Our study was informed by extant studies and theories of racial socialization (Hughes & Chen, 1992), Ogbu's (1988), theory of oppositional culture, and Murry and Brody's research with rural African American families. We also relied on tenets of the competence model of family functioning (Waters & Lawrence, 1993), which asserts that many of the processes, including racial and ethnic socialization, in which African American parents engage to rear competent children, represent adaptive responses to environmental challenges. demonstrating the importance of both racial and ethnic socialization in enhancing African American youths resilience over time, instilling in them a sense of racial pride that will enable them to resist negative societal images of members of their racial and ethnic group, including images that associate underachievement and low academic success with “being Black in American.” Our findings also highlight that studies of parenting among minority groups should take into consideration the relevance of historical influences and beliefs regarding raising children.

To that end and in accordance to the SGRCE theoretical model, our work contributes to a renewed interest in disaggregating racial and ethnic socialization to understand better how these unique parenting aspects impact youth development. In the present study, we sought to illustrate that, because African American parents rear their children in a society in which they and their children are often devalued (Stevenson et al., 1996). In this endeavor, they may be particularly inclined to engage in situation-specific parenting behaviors, including engaging in conversations that prepare them for the challenges associated with growing up in a society that does not embrace members of their racial group. These parenting strategies are commonly referred to as racial or ethnic socialization. We contend that there is a need to disaggregate these two domains of parenting because the content of messages transmitted by each may have differential impact on youth outcomes. In particular, socialization process in which African American parents emphasize self-acceptance and racial pride to their children make evoke messages that inform youths’ perception of self-image: that African Americans are strong, beautiful, people with a rich history. Whereas, messages to prepare youth for racism and discrimination they will face, may be more directed toward instructions regarding coping strategies that may be employed to reduce racism related stress (Stevenson, Reed, & Bodison, 1996), or instill in their children an awareness of the importance of resisting white hegemony and power structures that create barriers, and rather than succumbing to these injustices provide strategies for their children to overcome those real or perceived barriers and succeed. Historically, African American parents have strongly believed that education as a pathway to upward mobility and impart messages supporting that belief to their children (Bowman & Howard, 1985; Jodl, Michael, Malanchuk, Eccles, & Sameroff, 2001; Phinney & Chavira, 1995; M. G. Sanders, 1997). Moreover, our findings offer support to substantiate the relevance of both ethnic and racial socialization in order to understand the dynamics of child socialization in rural African American families.

Findings from our study lend support for the classic work of Bowman and Howard (1985), who contend that when African American parents socialized their children about group affiliation, pride and awareness of social inequality, children were more likely to have high academic achievement. In particular, we found that adaptive racial and ethnic socialization promoted elevated racial identity and heightened self-esteem that in turn, reduced the use of academic self-presentation strategies among youth. For youths who did not engage in academic self-presentation, parents’ had high expectations that they would do well in school, and their teachers’ viewed them as academically competent. Teaching youth about both racial and ethnic related issues facilitate high academic achievement by encouraging youth to be strong and to work hard, which in turn fosters a sense empowerment , as well as confidence and pride among youth (M. G. Sanders, 1997).

The association between parents’ academic expectation and their children's expectation of their academic abilities has been well documented (Sanders, Field, & Diego, 2001). Relatively little is known, however, about the link between African American parents’ racial and ethnic socialization and their academic expectations for their preadolescent children, or about the linkages parental educational expectations, parenting practices, and youth development. Even less is known about ways in which youths’ practice of self-presentation transmits messages to teachers that in turn forecasts teachers’ perceptions of students’ academic abilities. Our findings address these gaps, emphasizing that adaptive racial and ethnic socialization have protective contributions for youths’ academic outcomes. By enhancing youths’ sense of self, parents indirectly dissuade youth from disassociating from school as a way to maintain collective identity. Although most correlational studies have shown direct links between racial socialization and racial identity, our findings extend this area of research by demonstrating the importance of both racial and ethnic socialization for not only racial identity but also self-esteem. Further, our findings support other studies that have shown that instrumental and emotional support from parents buffered youths from the negative consequences of stressful life events by fostering positive self-perceptions (McCreary et al., 1999). Positive self-pride, in turn decreases the tendency for youth to hide their academic talents from others in order to maintain a sense of collective identity.

An important issue to consider is how parents influence self-pride in youth. According to Lerner's circular functioning theory, during the early years of children's development, children receive feedback about themselves from others, including their parents. These interactions trigger children's self-evaluations (Murry, Brody, et al., 2005). Children develop greater self-acceptance when the interactions are positive and consistent with the prevailing standards of persons who are important to them. In addition to families and other significant adults, youth acquire information about themselves from school (Reichert & Kuriloff, 2004), teachers in particular. Noteworthy is that findings from the current study provide evidence of the importance of considering the active role of youth in their own socialization and development. Our findings revealed that to the extent to which youth conceal their academic competence from peers, teachers and parents may also observe such displays and respond by underestimating the youths’ true potential and abilities. Mirroring that image back at youth may have long term implications for the development of academic possible selves, which subsequently can inhibit youths’ options for success in normative pathways.

For our final analysis, we tested a replication of our hypothetical model moderated by gender to determine whether the predicted paths operate differently for boys and girls reared in comparable contexts. No significant differences emerged, suggesting that the process through which racial and socialization influenced the academic success of rural African American youth, worked similarly for both males and females.

Although our findings are noteworthy and make a unique contribution to the literature on parenting and adolescent adjustment, the study is not without limitations. It is important to recognize the heterogeneity not only of African American families but also of rural families. The extent to which our findings can be generalized to rural African American families from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds also remains unknown. In addition, because our sample consisted of preadolescents, we are unable to draw conclusions about early to late adolescence, a time when peer influence becomes more important and possibly heightens adolescents’ need to “fit in.” Future waves of data will allow us to deduce how socialization works to protect youth during a potentially more vulnerable developmental period. Finally, it seems important to acknowledge that the potential bias in our measure of academic success includes teachers’ report of their perception of African American youths’ academic abilities. This is of particular concern, given that accounts of racial bias in both grading and placement of teachers, especially for African American males, have been documented (Dei, Mazzuca, McIssac, & Zine, 1997; Mickelson, 2003; Swanson, Cunningham, & Spencer, 2003; Wright, Weekes, McGlaughlin, & Webb, 1998). Accordingly, it is well-known that teachers’ often perceive students of color to be deficient (Gay, 2000; Haberman & Post, 1992; Sleeter, 1993). These perceptions not only influence teachers expectations for students, but may also hinder teachers’ ability to accurately estimate students’ learning potential (Ferguson, 1998). In fact, teachers’ perception and expectation have been conjectured to increase underachievement of students of color (Skrla & Scheurich, 2003). Although our analyses did not capture these issues in our assessment of academic success, we are confident in our ability to account some of the variability related to teachers’ perceptions of African American students’ performance, given that both parents and teachers’ report of youth's academic competence hung together and evinced positive loading to confirm their utility as indicators of the academic success construct.

Another limitation is related to the extent to which we have adequately captured identity formation, given the short time span of the current study. We raise this issue because identity development is a normative, dynamic, complex process, youths’ self-reflections and heightened awareness of what it means to be an adolescent, an African American, and an African American adolescent female or male are facilitated by their growing capacity to think cognitively about “self.” Thus, we anticipate a natural shifting of youths’ racial identity and self-esteem as the 10-to 11-year-olds included in our study transition into later stages of adolescence. At the same time, our results show promising patterns of the need to dismantle racial and ethnic socialization in studies of racial identity formation and self-esteem of rural African American youth. Further, although our follow-up assessment was conducted after youth transitioned in to early adolescence, what is apparent is that youth self-pride (e.g. racial identity and self-esteem) is pivotal to youth academic success. The results of this investigation add to the evidence indicating that parenting processes, in particular, both racial and ethnic socialization, can foster positive racial identity and self-esteem that in turn buffer youth from minimizing their academic abilities and increase teachers’ expectation for youth's academic competence. This finding may have implications for reducing underachievement in school, enhancing school bonding, and more importantly reducing drop out rates, among in rural African American youths who are living in contextually challenging circumstances.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and the National Institute of Mental Health. Cady Berkel's involvement in the preparation of this manuscript was partially supported by Grant T32MH18387.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at http://www.apa.org/journals/cdp/

Contributor Information

Velma McBride Murry, Center for Family Research, University of Georgia.

Cady Berkel, Prevention Research Center, Arizona State University.

Gene H. Brody, Center for Family Research, University of Georgia

Shannon J. Miller, Department of Child and Family Development, University of Georgia

Yi-fu Chen, Center for Family Research, University of Georgia.

References

- Alpert B. Students' resistance in the classroom. Anthropology & Education Quarterly. 1991;22:350–366. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. Amos 5.0. SPSS; Chicago, IL: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL, Wothke W. Amos 4.0 user's guide. SmallWaters Corporation; Chicago: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo CG, Zigler E. Racial identity, academic achievement, and the psychological well-being of economically disadvantaged adolescents. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1995;69:903–914. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billingsley A. The treatment of negro families in American scholarship. 1968. In.

- Boatright SR, Bachtel DC, editors. The Georgia county guide. Athens, GA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman PJ, Howard C. Race-related socialization, motivation, and academic achievement: A study of Black youths in three-generation families. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry. 1985;24:134–141. doi: 10.1016/s0002-7138(09)60438-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Dorsey S, Forehand R, Armistead L. Unique and protective contributions of parenting and classroom processes to the adjustment of African American children living in single-parent families. Child Development. 2002;73:274–286. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Ge X, Conger RD, Gibbons FX, Murry VM, Gerrard M, et al. The influence of neighborhood disadvantage, collective socialization, and parenting on African American children's affiliation with deviant peers. Child Development. 2001;72:1231–1246. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Kim S, Murry VM, Brown AC. Longitudinal links among parenting, self-presentations to peers, and the development of externalizing and internalizing symptoms in African American siblings. Development & Psychopathology. 2005;17:185–205. doi: 10.1017/s0954579405050108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Murry VM, Kim S, Brown AC. Longitudinal pathways to competence and psychological adjustment among African American children living in rural single-parent households. Child Development. 2002;73:1505–1516. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Stoneman Z. Child competence and developmental goals among rural Black families: Investigating the links. In: Sigel IE, McGillicuddy-DeLisi AV, Goodnow JJ, editors. Parental belief systems: The psychological consequences for children. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns RB, Cairns BD. Social ecology over time and space. In: Moen P, Elder GH, editors. Examining lives in context: Perspectives on the ecology of human development. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 1995. pp. 397–421. [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Bem DJ. Personality continuity and change across the life course. In: Pervin L, editor. Handbook of personality theory and research. Guilford Press; New York: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Elder GH, Bem DJ. Moving against the world: Life-course patterns of explosive children. Developmental Psychology. 1987;23:308–313. [Google Scholar]

- Dei GJS, Mazzuca J, McIssac E, Zine J. Reconstructing ‘drop-out’: A critical ethnography of the dynamics of Black students' disengagement from school. University of Toronto Press; Buffalo, NY: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Donovan JE, Jessor R, Costa FM. Adolescent health behavior and conventionality-unconventionality: An extension of Problem-Behavior Theory. Health Psychology. 1991;10:52–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford DY, Harris JJ. The American achievement ideology and achievement differentials among preadolescent gifted and nongifted African American males and females. Journal of Negro Education. 1992;61:45–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ford DY, Harris JJ. A study of the racial identity and achievement of Black males and females. Roeper Review. 1997;20:105–110. [Google Scholar]

- Fordham S. Racelessness as a factor in Black students' school success: Pragmatic strategy or pyrrhic victory? Harvard Educational Review. 1988;58:54–84. [Google Scholar]

- Fordham S, Ogbu JU. Black students' school success: Coping with the “burden of acting White”. Urban Review. 1986;18:176–206. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Cleveland MJ, Wills TA, Brody GH. Perceived discrimination and substance use in African American parents and their children: A panel study. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 2004;86:517–529. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.4.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare BR. Reexamining the achievement central tendency: Sex differences within race and race differences within sex. In: McAdoo JL, editor. Black children: Social, educational, and parental environments. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1985. pp. 139–155. [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. The Perceived Competence Scale for Children. Child Development. 1982;53:87–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helms JE, Henze KT, Sass TL, Mifsud VA. Treating cronbach's alpha reliability coefficients as data in counseling research. The Counseling Psychologist. 2006;34:630–660. [Google Scholar]

- Hill SA. Class, race, and gender dimensions of child rearing in African American families. Journal of Black Studies. 2001;31:494–508. [Google Scholar]

- Honora DT. The relationship of gender and achievement to future outlook among African American adolescents. Adolescence. 2002;37:301–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Chen L. When and what parents tell children about race: An examination of race-related socialization among African American families. Applied Developmental Science. 1997;1:200–214. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Johnson D. Correlates in children's experiences of parents' racial socialization behaviors. Journal of Marriage & Family. 2001;63:981–995. [Google Scholar]

- Jodl KM, Michael A, Malanchuk O, Eccles JS, Sameroff A. Parents' roles in shaping early adolescents' occupational aspirations. Child Development. 2001;72:1247–1265. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layton C, Eysenck S. Psychotism and unemployment. Personality & Individual Differences. 1985;6:387–390. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall S. Ethnic socialization of African American children: Implications for parenting, identity development, and academic achievement. Journal of Youth & Adolescence. 1995;24:377–396. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Coatsworth JD. The development of competence in favorable and unfavorable environments: Lessons from research on successful children. American Psychologist. 1998;53:205–220. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAdoo HP. Black families. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Mickelson RA. When are racial disparities in education the result of racial discrimination? A social science perspective. Teachers College Record. 2003;105:1052–1086. [Google Scholar]

- Miller DB. Racial socialization and racial identity: Can they promote resiliency for African American adolescents? Adolescence. 1999;34:493–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DB, MacIntosh R. Promoting resilience in urban African American adolescents: Racial socialization and identity as protective factors. Social Work Research. 1999;23:159–169. [Google Scholar]

- Mirón LF, Lauria M. Student voice as agency: Resistance and accommodation in inner-city schools. Anthropology & Education. 1998;18:312–334. [Google Scholar]

- Murray CB, Mandara J. Racial identity development in African American children: Cognitive and experiential antecedents. In: McAdoo HP, editor. Black children: Social, educational, and parental environments. 2nd ed. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2002. pp. 73–96. [Google Scholar]

- Murry VM. Challenges and life expectancies of Black American families. In: McKenry PC, Price SJ, editors. Families and change: Coping with stressful events and transitions. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Murry VM, Brody GH. Self-regulation and self-worth of Black children reared in economically stressed, rural, single mother-headed families: The contribution of risk and protective factors. Journal of Family Issues. 1999;20:458–484. [Google Scholar]

- Murry VM, Brody GH. Racial socialization processes in single-mother families: Linking maternal racial identity, parenting, and racial socialization in rural, single-mother families with child self-worth and self-regulation. In: McAdoo HP, editor. Black children: Social, educational, and parental environments. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2002. pp. 97–115. [Google Scholar]

- Murry VM, Brody GH. Partnering with community stakeholders: Engaging rural African American families in basic research and the Strong African American Families preventive intervention program. Journal of Marital & Family Therapy. 2004;30:271–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2004.tb01240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murry VM, Brody GH, McNair LD, Luo Z, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, et al. Parental involvement promotes rural African American youths' self-pride and sexual self-concepts. Journal of Marriage & Family. 2005;67:627–642. [Google Scholar]

- Murry VM, Brown PA, Brody GH, Cutrona CE, Simons RL. Racial discrimination as a moderator of the links among stress, maternal psychological functioning, and family relationships. Journal of Marriage & Family. 2001;63:915–926. [Google Scholar]

- Ogbu JU. The consequences of American caste system. In: Neisser U, editor. The school achievement of minority children. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1986. pp. 19–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ogbu JU. Differences in cultural frame of reference. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1993;16:483–506. [Google Scholar]

- Ogbu JU. Racial stratification and education in the United States: Why inequality persists. Teachers College Record. 1994;96:264–298. [Google Scholar]

- Ogbu JU. African American education: A cultural-ecological perspective. In: McAdoo HP, editor. Black families. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1997. pp. 234–250. [Google Scholar]

- Ogbu JU. Collective identity and the burden of “acting White” in Black history, community, and education. The Urban Review. 2004;36:1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman D, Bybee D, Terry K, Hart-Johnson T. Possible selves as roadmaps. Journal of Research in Personality. 2004;38:130–149. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson RA. A meta-analysis of Cronbach's coefficient alpha. Journal of Consumer Research. 1994;21:381–391. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, Cantu CL, Kurtz DA. Ethnic and American identity as predictors of self-esteem among African American, Latino, and White adolescents. Journal of Youth & Adolescence. 1997;26:165–185. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, Chavira V. Parental ethnic socialization and adolescent coping with problems related to ethnicity. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1995;5:31–53. [Google Scholar]

- Proctor BD, Dalaker J. Poverty in the United States: 2002. Washington, DC: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Reichert MC, Kuriloff P. Boys' selves: Identity and anxiety in the looking glass of school life. Teachers College Record. 2004;106:544–573. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ: 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Rowley SJ, Sellers RM, Chavous TM, Smith MA. The relationship between racial identity and self-esteem in African American college and high school students. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1998;74:715–724. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.3.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders CE, Field TM, Diego MA. Adolescents' academic expectations and achievement. Adolescence. 2001;36:795–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders MG. Overcoming obstacles: Academic achievement as a response to racism and discrimination. Journal of Negro Education. 1997;66:83–93. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders J, Davis L, Williams T, Williams JH. Gender differences in self-perceptions and academic outcomes: A study of African American high school students. Journal of Youth & Adolescence. 2004;33:81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Skrla L, Scheurich JJ. Educational equity and accountability: Paradigms, policies, and politics. Routledge; London: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Smith EP, Brookins CC. Toward the development of an ethnic identity measure for African American youth. Journal of Black Psychology. 1997;23:358–377. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer MB, Noll E, Stoltzfus J, Harpanlani V. Identity and school adjustment: Revising the “acting white” assumption. Educational Psychologist. 2001;36:21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson HC, Reed J, Bodison P. Kinship social support and adolescent racial socialization beliefs: Extending the self to family. Journal of Black Psychology. 1996;22:498–508. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson DP, Cunningham M, Spencer MB. Black males' structural conditions, achievement patterns, normative needs, and “opportunities”. Urban Education. 2003;38:608–633. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson CP, Anderson LP, Bakeman RA. Effects of racial socialization and racial identity on acculturative stress in African American college students. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2000;6:196–210. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.6.2.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tickamyer AR, Duncan CM. Poverty and opportunity structure in rural America. Annual Review of Sociology. 1990;16:67–86. [Google Scholar]

- Twenge JM, Crocker J. Race and self-esteem: Meta-analyses comparing Whites, Blacks, Hispanics, Asians, and American Indians and comment on Gray-Little and Hafdahl (2000). Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:371–408. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.3.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters DB, Lawrence EC. Competence, courage and change: An approach to family therapy. Norton Publishers; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Werner EE, Smith R. Cornell University Press. New York: 1992. Overcoming the odds: High-risk children from birth to adulthood. [Google Scholar]

- Wright C, Weekes D, McGlaughlin A, Webb D. Masculinised discourses within education and the construction of Black male identities amongst African Caribbean youth. British Journal of Sociology of Education. 1998;19:75–87. [Google Scholar]