Abstract

We evaluated patients’ satisfaction with the physician caring for them as part of an international web-based survey of quality of life(QOL) in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia(CLL; n=1482). Over half(55.9%) of patients thought about their diagnosis daily. Although >90% felt their doctor understood how their disease was progressing(i.e., stage, blood counts, nodes), <70% felt their physician understood how CLL affected their QOL(anxiety, worry, fatigue). Reported satisfaction with their physician in a variety of areas strongly related to patients’ measured emotional and overall QOL(all p<0.001). Physician use of specific euphemistic phrases to characterize CLL (e.g., “CLL is the ‘good’ leukemia”) was also associated with lower emotional QOL among patients (p<0.001). These effects on QOL remained(p<0.001) after adjustment for age, co-morbid health conditions, fatigue, and treatment status. The effectiveness with which physicians help patients adjust to the physical, intellectual, and emotional challenges of CLL appears to impact patient QOL.

Keywords: leukemia, supportive care, quality of life

Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia(CLL) is one of the most common lymphoid malignancies1–3. An overwhelming majority of patients(70–80%) have early-stage disease at the time of diagnosis and have no clinical symptoms4–6. Based on randomized phase 3 trials demonstrating no increase in survival with early institution of alkylating agent-based chemotherapy, such patients are typically managed with a “watch and wait” strategy7,8. While this is an evidence-based approach, it can be psychologically difficult for patients who recognize they have a significant health problem and often feel that “nothing is being done about it”. Patients also face significant uncertainty about the future repercussions of their CLL on their family members, functional status, and ability to work in addition to uncertainties about the side effects of future chemotherapeutic treatments9. Since they typically have little understanding of CLL at the time of their diagnosis, patients are often heavily reliant on their physician to provide information about the illness and support them as they adjust to the implications of the diagnosis.

Despite these significant challenges to quality of life (QOL) faced by CLL patients, few studies have evaluated the QOL of individuals with CLL. Nearly all studies that have done so were performed in conjunction with clinical trials testing the efficacy of various chemotherapeutic treatments for patients with advanced stage or progressive disease10–13. Although a growing body of literature on the importance of physician-patient communication has emerged over the last decade14–19, to our knowledge, no study has evaluated the influence of the doctor-patient relationship on emotional distress or QOL in patients’ with CLL.

We recently conducted an international web-based survey of CLL patients which used standardized instruments to evaluate fatigue and QOL20. Consistent with the asymptomatic nature of CLL at the time of diagnosis for most patients, the physical, functional, and overall QOL scores of CLL patients in this study were similar to or better than both published population norms and samples of patients with other types of cancer21–23. In distinct contrast, the emotional QOL scores of CLL patients were significantly lower than both the general population and individuals with other malignancies.

When designing this study, we hypothesized that a CLL patient’s relationship with their physician impacts their emotional QOL. To test this hypothesis we evaluated patients’ satisfaction with the physician caring for their CLL as part of our international survey. In addition, we asked patients to indicate whether the physician caring for them had used specific phrases to describe CLL which were hypothesized to undermine patient’s adjustment to their diagnosis. Here, we analyze these factors and assess their relationship with patient’s emotional QOL as assessed by validated instruments.

Materials and Methods

Patients on Accrual

As previously described20, we conducted a web-based survey evaluating QOL in CLL patients between June and October 2006. This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board. The survey was posted to the worldwide web and was open to participation by CLL patients around the world. Patients were recruited principally through partnership with CLL patient advocacy organizations20.

Survey Content

A detailed description of the survey has been previously published20. Information on patient demographics, CLL-specific information, and comorbid health problems(evaluating conditions assessed by the Charlson Comorbidity Index24) was collected. The survey included the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy General(FACT-G) QOL survey,25 a standardized instrument to measure health-related QOL, that has been extensively used21–23 and shown to correlate well with other QOL assessment tools26. The study also included the Brief Fatigue Inventory(BFI), a standardized tool to assess fatigue for which published normative data is available27. The survey also included a number of study-specific questions which explored potential sources of anxiety related to CLL and evaluated patient satisfaction with the physician caring for their CLL(Appendix 1).

Statistical analysis

Demographic and CLL-specific information were compiled and descriptive statistics(Wilcoxon rank tests or Pearson’s chi-square tests) were computed. The BFI and FACT-G were scored according to the appropriate algorithm25 27 with missing data and adapted scoring scales handled as previously described20. Linear regression analyses were performed to adjust for covariates(such as disease stage), as well as to evaluate multivariate effects on QOL. Specifically, we evaluated whether the items related to patients’ satisfaction with their physician, understanding of CLL, and the phrases physicians had used to describe CLL improved our previously developed models for QOL20. Each item was first evaluated individually while adjusting for the other factors(e.g., age, extent of co-morbid health conditions, treatment status, etc.) previously shown to relate to patient QOL. We then modeled the items on satisfaction jointly in a multivariate model. For this analysis, however, only two items were considered because the five items on physician satisfaction and knowledge of CLL were highly associated with each other. The two items selected showed the least amount of correlation(odds ratio = 2.29; 95% confidence interval: 1.68, 3.13); the remaining associations had odds ratios > 4.0.

Results

Between June and October of 2006, 1482 patients with CLL responded to the survey. The diagnosis of CLL was validated in a randomly selected subset of survey participants who returned HIPAA waivers along with documentation from their health care provider20. The patient characteristics, overall QOL scores, and degree of fatigue have been previously reported20. Median age was 59 years(range 26–88), 57%(n=695) of respondents were men, 81%(n=1179) were married, 84%(n=1233) had children, and 97.5%(n=1422) were Caucasian. The median time from diagnosis to completion of the study survey was 3.4 years and 40%(n=591) of respondents had been previously treated for their CLL.

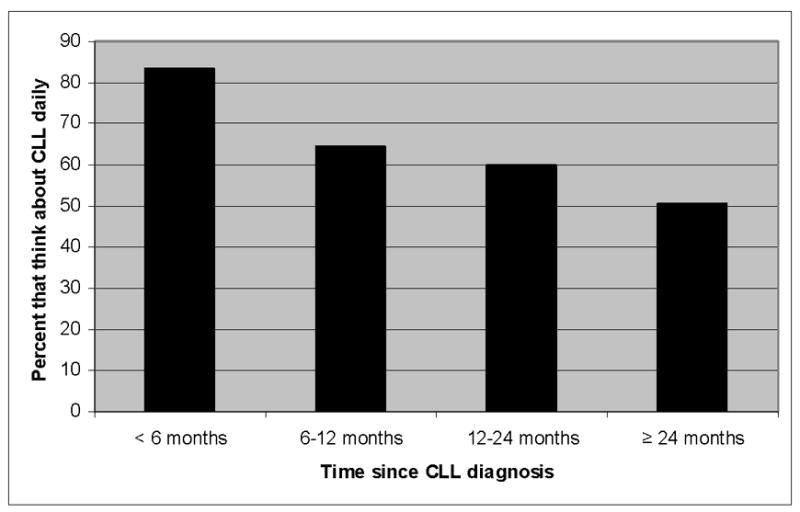

The current analysis evaluated the sources of anxiety in CLL patients, their satisfaction with the physician managing their CLL, and the relationship between these factors and QOL. We first evaluated how often patients thought about their illness. Over half(55.9%; n=822) of patients reported they thought about their CLL diagnosis daily. An additional 24%(n=355) reported thinking about their CLL diagnosis several times a week, while lesser numbers reported they thought about CLL “several times a month”(11.1%; n=163), “about once a month”(5.3%; n=78), or “less than once a month”(3.6%; n=53). Patients with greater degrees of fatigue, lower emotional QOL scores, and lower overall QOL scores were more likely to think about their CLL daily(Table 1) as were those who had been diagnosed more recently(Figure 1).

Table 1.

Relationship Between QOL, Fatigue, and the Frequency With Which Patients Think About CLL

| How often do you think about your CLL? | N (%) | Emotional QOL Score◆ | Overall QOL Score◆ | Fatigue Score* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily | 822 (55.9) | 16.2 | p<0.001 | 71.1 | p<0.001 | 3.1 | p<0.001 |

| Several times a week | 355 (24.1) | 18.0 | 75.1 | 2.7 | |||

| Several times a month | 163 (11.1) | 19.1 | 79.2 | 2.2 | |||

| About once a month | 78 (5.3) | 20.6 | 81.4 | 1.9 | |||

| Less than once a month | 53 (3.6) | 21.5 | 82.8 | 2.0 | |||

FACT-G – higher score indicates better quality of life

BFI – higher score indicates greater fatigue (worse quality of life)

Figure 1. Proportion of Patients Who Think About Their CLL Diagnosis Daily.

Y axis indicates the percent of patients who think about their CLL diagnosis daily based on time since diagnosis (x axis; n=1,482).

Patients also rated the impact of six disease-specific concerns on their QOL using an 11-point Likert scale(0=“no effect on my QOL” and 10=“major negative effect on my QOL”). Results are shown in Table 2. Patient ratings varied by current disease stage. With the exception of “concern my children or relatives may also develop CLL,” the negative impact of all items on QOL increased with more advanced disease stage. Although “concern about the implications of CLL for my family/loved ones” had the highest mean rating at all stages of the disease, the hierarchical importance of other sources of anxiety as assessed by mean scores differed by patients’ disease stage(p<0.001; see Table 2 for statistical comparisons). Among early-stage patients “uncertainty about whether my CLL will progress” and “concern my children or relatives may also develop CLL” were the 2nd and 3rd rated sources of anxiety while among advanced stage patients “living with symptoms related to CLL(fatigue, weight loss, night sweats, infections)” and “concern about the side-effects of treatment for my CLL” were the 2nd and 3rd rated factors.

Table 2.

Sources of Anxiety in CLL patients1

| Overall N=1482 |

Low Risk2 N=537 |

Intermediate Risk2 N=459 |

High Risk2 N=209 |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concern about the implications of my CLL for my family/loved ones | 5.1 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 7.0 | <0.001 |

| Uncertainty about whether my CLL will progress | 4.3 | 3.9 | 4.4 | 5.4 | <0.001 |

| Concern about the side effects of treatment for my CLL | 4.1 | 3.3 | 4.3 | 5.6 | <0.001 |

| Concern my children or relatives may also develop CLL | 3.6 | 3.5 | 3.8 | 3.9 | 0.396 |

| Generalized worry about having CLL | 3.6 | 3.1 | 3.6 | 4.6 | <0.001 |

| Living with symptoms related to CLL (fatigue, weight loss, night sweats, infections) | 3.5 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 6.0 | <0.001 |

Patients were asked to rate how much each item negatively affected their quality of life on a 0–10 Likert scale where 0 = “no effect on my quality of life” and 10 = “major negative effect on my QOL”. Items are shown in hierarchical order of importance to CLL patients based on mean scores.

Risk refers to patients stage using the modified Rai risk categorization28

Patients were next asked to indicate their satisfaction with various aspects of the physician caring for their CLL and whether the patient had a good understanding of CLL. Greater than 90%(91.2%, n=1340) of patients felt their doctor had a “good understanding of how their disease was progressing(i.e., the stage, blood counts, lymph nodes)”, and 90%(n=1324) felt “comfortable talking to their doctor about treatment and management of CLL”. In contrast, 69.6%(n=1024) felt their “doctor had a good understanding of how CLL was affecting their QOL(anxiety, worry, fatigue, etc.)”, and 77%(n=1134) felt “comfortable talking to their doctor about how CLL affected their QOL(anxiety, worry, fatigue, etc.)”. Reported satisfaction with their physician in these areas strongly related to patients’ emotional QOL(FACT-G) and overall QOL(FACT-G; Table 3).

Table 3.

Aspects of the Doctor – Patient Relationship and Anxiety in CLL Patients

| N (%) | Emotional QOL Score◆ | Overall QOL Score ◆ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do you feel you have a good understanding of your CLL? | Yes | 1261 (85.5) | 17.7 | p<0.001 | 75.0 | p<0.001 |

| No | 214 (14.5) | 15.1 | 67.5 | |||

| Do you feel your doctor has a good understanding of how your disease is progressing? | Yes | 1340 (91.2) | 17.5 | p<0.001 | 74.9 | p<0.001 |

| No | 129 (8.8) | 15.5 | 64.0 | |||

| Do you feel comfortable talking to your doctor about treatment and management of CLL? | Yes | 1324 (90.0) | 17.7 | p<0.001 | 75.2 | p<0.001 |

| No | 148 (10.0) | 14.6 | 62.8 | |||

| Do you feel your doctor has a good understanding of how your CLL is effecting your QOL (anxiety, worry, fatigue)? | Yes | 1024 (69.6) | 18.3 | p<0.001 | 77.9 | p<0.001 |

| No | 447 (30.4) | 15.1 | 64.8 | |||

| Do you feel comfortable talking to your doctor about how your CLL effects your QOL? | Yes | 1134 (77.1) | 18.0 | p<0.001 | 76.7 | p<0.001 |

| No | 336 (22.9) | 15.1 | 64.5 | |||

FACT-G – higher score indicates better quality of life

Patients were also asked to indicate whether the physician caring for them had used specific phrases to describe CLL. Thirty-three percent of patients had been told “CLL is the ‘good’ leukemia”, 24% had been told “don’t worry about your CLL”, and 35% had been told “if you could pick what cancer to have, this is what you would choose”. In aggregate, 52% of patients had received one of more of these characterizations of CLL by their physician. Measured emotional QOL and overall QOL were worse among patients who reported their physician had used these phrases to describe CLL(Table 4). Patients whose physician had used one of these phrases to describe CLL were less likely to feel their physician had a good understanding of their CLL or understood how CLL was effecting their QOL(all p<0.001). Patients whose physicians had used these phrases were also less likely to feel comfortable discussing disease management and the effects of CLL on their QOL with their physician(p<0.001; Table 5).

Table 4.

Phrases Used by Physicians to Describe CLL and Patient QOL

| Has your doctor ever used following phrases▲ | N (%) | Emotional QOL Score◆ | Overall QOL Score◆ |

|---|---|---|---|

| CLL is the “good leukemia” | 494 (33.3%) | 16.6 | 70.1 |

| Don’t worry about your CLL? | 354 (23.8%) | 16.4 | 69.9 |

| If you could pick what cancer to have, this is it | 524(35.4%) | 16.8 | 71.5 |

| My doctor has never used any phrases like this | 720 (48.6%) | 18.0 | 76.6 |

Patients asked to indicate all phrases their physician had used to describe CLL

FACT-G – higher score indicates better quality of life

All p-values for comparisons are p<0.001

Table 5.

Physician Use of Specific Phrases to Describe CLL and Patient Satisfaction with Their Physician

| Doctor did not use any of 3 phrases* N=720 |

Doctor used 1 or more of 3 phrases* to describe CLL N=762 (%) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients who felt their doctor had a good understanding of how their disease was progressing | 677 (94.7) | 663 (87.9) | <0.001 |

| Patients who felt comfortable talking to their doctor about treatment and management of CLL | 676 (94.7) | 648 (85.5) | <0.001 |

| Patients who felt their doctor had a good understanding of how CLL was effecting their QOL | 578 (80.8) | 446 (59.0) | <0.001 |

| Patients who felt comfortable talking to their doctor about how CLL effected their QOL | 611 (85.3) | 523 (69.4) | <0.001 |

CLL is the ‘good’ leukemia; Don’t worry about your CLL; If you could pick what kind of cancer to have, this is what you would choose

Finally, we performed multi-variable modeling to identify factors independently associated with QOL. Since we had previously demonstrated that age, gender, fatigue, extent of co-morbid health conditions, and treatment relate to QOL20, we evaluated whether patients’ satisfaction with their physician or physician use of specific phrases to describe CLL improved models of QOL already including those factors. Both “do you feel comfortable talking to your doctor about how your CLL affects your QOL” and “do you feel you have a good understanding of CLL” remained associated with emotional and overall QOL in the regression analysis(p<0.001). For overall QOL, 53% of the variation in patient QOL was explained by age, treatment status(current treatment), Charlson score, BFI, and response to these two questions. For emotional QOL, 27% of the variation in patient QOL is explained by age, gender, treatment status(previous and current treatment), and response to these two questions. In both models(overall and emotional QOL) response to the two questions had a larger effect on QOL score than any other factor in the model including current treatment. Reported use of 1 or more of the 3 phrases(e.g., “CLL is the ‘good’ leukemia”) to characterize CLL by the treating physician also remained significantly associated with lower emotional QOL(p<0.01) and overall QOL(p<0.0001) in the regression analysis. However, when we also included in the model “do you feel comfortable talking to your doctor” or “do you feel you have a good understanding of CLL”, the reported use of 1 or more of the 3 phrases was not significantly associated with overall QOL(p=0.077) or emotional QOL(p=0.331).

Discussion

CLL is a common hematologic malignancy that can have profound effects on patient QOL14. In the present study of over 1400 patients, the majority of patients thought about their diagnosis daily. While the proportion who thought about CLL daily decreased with time from diagnosis, over half of patients still thought about their disease every day more than 2 years after diagnosis. Among the 6 specific potential sources of anxiety explored, patients at all disease stages rated concern about the implications of their CLL for their family and loved ones as their greatest concern. The importance of other potential sources of anxiety varied by disease stage. Notably, the domain most frequently assessed by physicians(symptoms of fatigue, night sweats, weight loss, infection) was the lowest rated source of concern for patients with low or intermediate stage disease, while domains that are often unexplored(concerns about family members developing CLL, impact of the patient’s disease on their family members) were rated more highly.

We also found a powerful connection between patient’s relationship with their physician and their QOL. While over 90% of patients felt their physicians had a good understanding of how their disease was progressing, nearly 1/3 felt their physicians failed to recognize how CLL affected their QOL. Patients were also more likely to feel comfortable discussing treatment and disease management with their physician than discussing how the disease affected their QOL. Patients who felt their physician failed to understand the effects of CLL on their QOL or were uncomfortable discussing such effects with the physician had lower measured QOL. Evidence suggests the effect size of these differences in QOL are clinically meaningful29–31. Importantly, this effect on QOL remained(p<0.001) after adjustment for age, extent of co-morbid health conditions, measured fatigue, and treatment status in a regression analysis and these factors were the single strongest predictors of both overall QOL and emotional QOL in the models.

The language physicians used to describe CLL to their patients was also strongly related to patient QOL. Roughly half of the patients surveyed had been told by their physician that “CLL is the good leukemia”, “not to worry about their CLL”, and/or “if you could pick what cancer to have, this is it”. While these euphemisms are intended to be reassuring, they can invalidate the patient’s experience: there is no “good” leukemia, nearly all patients with a serious health problem are concerned about their diagnosis, and no one desires to have any type of cancer. Such statements represent a physician centered framing of the disease because they attempt to qualify the significance of the diagnosis by comparing it to other types of cancer rather than focusing on what this diagnosis means to this patient. Reported use of any of these phrases by the patient’s physician was associated with lower QOL and decreased satisfaction with their physician. Once again, this effect on QOL remained(p<0.001) after adjustment for age, extent of co-morbid health conditions, measured fatigue, and treatment status in a regression analysis. Importantly, reported use of these phrases also decreased patients reported comfort discussing QOL issues with their physician, suggesting such statements are conversation terminators32 that may imply to some patients their physician views the illness as unimportant and is not interested in its effects on their QOL.

Substantial research on the oncologist-patient relationship has emerged over the last decade with most of this research focused on physician patient communication15 and the delivery of bad/difficult news14,16. This research suggests the manner in which bad news is delivered and received can have significant psychological impact on patients33 and their families34. While physicians typically recognize the implications of the medical information they provide on patient’s physical health and life expectancy, they sometimes fail to recognize its impact on the emotional, social, spiritual, and occupational health of patients and their family members14. Despite its importance, oncologists often receive relatively little training in how to perform the difficult communication tasks associated with caring for patients with cancer. Increasing evidence suggests that such skills can be taught19,35–37.

How should physicians caring for patients with CLL respond to these findings? First, physicians need to recognize the profound emotional distress that can be precipitated by the diagnosis of CLL20. Second, physicians should refrain from using overly simplistic descriptions of the illness that fail to respect the patient’s personal determination of the meaning of their diagnosis. Third, since many patients report feeling uncomfortable discussing how CLL impacts their QOL with their medical provider, physicians should explicitly ask patients about anxiety, fatigue, worry, and other QOL problems they may be experiencing. Since the factors that cause the most concern vary between patients, a simple question such as, “what worries you most about your CLL?” may help physicians identify the needs of individual patients and allow them to tailor the support and education they provide. Finally, emotional distress related to CLL persists for years after diagnosis and should be addressed on an ongoing basis.

It is important to note that a strategy of “active surveillance” similar to that applied to patients with early stage CLL is also used in the management of other sub-types of low-grade non-Hodgkin lymphoma and selected older patients with early prostate cancer. Given the potential emotional distress precipitated by these diagnoses and the similarity in initial management, is tempting to speculate some of the findings in the current study may also have relevance in other malignancies–a hypothesis that warrants investigation.

Our study has a number of limitations. First, the electronic nature of the survey allowed for a large number of patients from around the world to participate but required participants have internet access and the ability to communicate in English. Most study participants were from the U.S. and the median age was younger than the general CLL patient population making the generalizability to other populations unknown. Second, patients with greater anxiety about their illness may be more likely to visit CLL patient advocacy web sites and to have heard about and participated in such a survey. Third, although QOL and fatigue were evaluated using standardized instruments, some characteristics such as disease stage were assessed by self-report. Fourth, because it was a cross-sectional survey, we cannot determine causality among the associations observed. Fifth, multiple biomarkers (e.g., immunoglobulin gene mutational status, ZAP-70 expression, CD38 expression, cytogenetics) are now available to help physicians predict the clinical course of the disease and it is unknown whether the introduction of these assays into clinical practice has heightened or alleviated the anxiety experienced by CLL patients. Finally, although the multi-variate models explained a substantial amount of the variation in patient’s overall and emotional QOL, they do not explain all the variation. Unmeasured factors not directly assessed such as personality traits, spirituality, and characteristics of social support likely account for some of the unaccounted for variation and should be evaluated in future studies.

Our study has several important strengths. To our knowledge, it is the first study to explore the importance of the physician-patient relationship in CLL and its potential influence on patient QOL. Standardized tools were used to evaluate fatigue and QOL and a large sample of patients from around the world participated. In addition to exploring the effects of the physician patient relationship, the study also included evaluation of disease characteristics(i.e., stage, treatment status) and co-morbidities that allowed us to control for a variety of other factors that may influence QOL.

CLL can have a profound impact on patient QOL. Physicians play an important role helping patients adjust to the physical, intellectual, and emotional challenges precipitated by their illness. The effectiveness with which physicians accomplish these tasks impacts patients’ QOL. The information, education, and support provided by physicians should be tailored to the individual needs of the patient. Additional studies exploring how physicians can best support patients with CLL and other malignancies are needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the patients with CLL from around the world who participated in this survey and to CLL Topics and other patient advocacy groups who encouraged patient participation.

APPENDIX 1: Study Specific Questions

Rate how much each item negatively effects your quality of life using the following scale:

| No effect on my quality of life | Major negative effect on my quality of life | |||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

Generalized worry about having CLL

Uncertainty about whether my CLL will progress

Concern about the side effects of treatment for CLL

Concern about the implications of my CLL for my family/loved ones

Concern my children or relatives may also develop CLL

Living with symptoms related to CLL (fatigue, weight loss, night sweats, infections)

-

How often do you think about your diagnosis of CLL?

daily

several times a week

several times a month

about once a month

less than once a month

-

Do you feel you have a good understanding of CLL?

Yes

No

-

Do you feel your doctor has a good understanding of how your disease is progressing (i.e. the stage, blood counts, lymph nodes)?

Yes

No

-

Do you feel comfortable talking to your doctor about treatment and management of CLL?

Yes

No

-

Do you feel your doctor has a good understanding of how your CLL is effecting your quality of life (anxiety, worry, fatigue, etc)?

Yes

No

-

Do you feel comfortable talking to your doctor about how your CLL effects your quality of life (anxiety, worry, fatigue, etc.)?

Yes

No

-

Has your doctor ever used any of the following phrases (or similar phrases) to explain the diagnosis of CLL to you (check all that apply)?

CLL is the ‘good’ leukemia

Don’t worry about your CLL

If you could pick what kind of cancer to have, this is what you would choose

My doctor has never used any phrases like this to describe CLL to me

Funding: National Cancer Institute [CA 113408 TD Shanafelt; CA 94919 to SL Slager; CA97274 to SL Slager]; Bayer Health Care Pharmaceuticals to TD Shanafelt.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Morton LM, Wang SS, Devesa SS, et al. Lymphoma incidence patterns by WHO subtype in the United States, 1992–2001. Blood. 2006;107:265–76. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A, Murray T, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2005. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:10–30. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zent CS, Kyasa MJ, Evans R, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia incidence is substantially higher than estimated from tumor registry data. Cancer. 2001;92:1325–30. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010901)92:5<1325::aid-cncr1454>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Call T, Phyilky R, Noel P, et al. Incidence of chronic lymphocytic leukemia in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1935 through 1989, with emphasis on changes in initial stage at diagnosis. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 1994;69:323–328. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)62215-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rozman C, Bosch F, Montserrat E. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a changing natural history? Leukemia. 1997;11:775–778. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2400679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Molica S, Levato D. What is changing in the natural history of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Haematologica. 2001;86:8–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dighiero G, Maloum K, Desablens B, et al. Chlorambucil in indolent chronic lymphocytic leukemia. French Cooperative Group on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1506–14. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199805213382104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chemotherapeutic Options in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: a Meta-analysis of the Randomized Trials. CLL Trialists’ Collaborative Group. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1999;91:861–868. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.10.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Molica S. Quality of life in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a neglected issue. Leuk Lymphoma. 2005;46:1709–14. doi: 10.1080/10428190500244183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levy V, Porcher R, Delabarre F, et al. Evaluating treatment strategies in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: use of quality-adjusted survival analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:747–54. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00359-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eichhorst BF, Busch R, Obwandner T, et al. Health-Related Quality of Life in Younger Patients With Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Treated With Fludarabine Plus Cyclophosphamide or Fludarabine Alone for First-Line Therapy: A Study by the German CLL Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2007 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.6929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rossi JF, van Hoof A, de Boeck K, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral fludarabine phosphate in previously untreated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1260–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Else M, Smith AG, Hawkins K, et al. Quality of Life in the LRF CLL4 Trial. Blood. 2005;106 Abstract# 2111. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fallowfield L, Jenkins V. Communicating sad, bad, and difficult news in medicine. Lancet. 2004;363:312–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15392-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Back AL, Arnold RM, Baile WF, et al. Approaching difficult communication tasks in oncology. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:164–77. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.3.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baile WF, Beale EA. Giving bad news to cancer patients: matching process and content. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:49s–51s. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jenkins V, Fallowfield L, Saul J. Information needs of patients with cancer: results from a large study in UK cancer centres. Br J Cancer. 2001;84:48–51. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baile WF, Lenzi R, Parker PA, et al. Oncologists’ attitudes toward and practices in giving bad news: an exploratory study. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2189–96. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Back AL, Arnold RM, Baile WF, et al. Efficacy of communication skills training for giving bad news and discussing transitions to palliative care. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:453–60. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.5.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shanafelt TD, Bowen D, Venkat C, et al. Quality of life in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: an international survey of 1482 patients. British Journal of Haematology. 2007 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06791.x. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brucker PS, Yost K, Cashy J, et al. General population and cancer patient norms for the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G) Eval Health Prof. 2005;28:192–211. doi: 10.1177/0163278705275341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holzner B, Kemmler G, Cella D, et al. Normative data for functional assessment of cancer therapy--general scale and its use for the interpretation of quality of life scores in cancer survivors. Acta Oncol. 2004;43:153–60. doi: 10.1080/02841860310023453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cella D, Zagari MJ, Vandoros C, et al. Epoetin alfa treatment results in clinically significant improvements in quality of life in anemic cancer patients when referenced to the general population. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:366–73. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:570–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holzner B, Bode RK, Hahn EA, et al. Equating EORTC QLQ-C30 and FACT-G scores and its use in oncological research. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:3169–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mendoza TR, Wang XS, Cleeland CS, et al. The rapid assessment of fatigue severity in cancer patients: use of the Brief Fatigue Inventory. Cancer. 1999;85:1186–96. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990301)85:5<1186::aid-cncr24>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rai K. A critical analysis of staging in CLL. New York: Alan R Liss; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sloan JA, Frost MH, Berzon R, et al. The clinical significance of quality of life assessments in oncology: a summary for clinicians. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14:988–98. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0085-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sloan JA. Assessing the minimally clinically significant difference: scientific considerations, challenges and solutions. Copd. 2005;2:57–62. doi: 10.1081/copd-200053374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sloan JA. Applying QOL Assessments: Solutions for Oncology Clinical Practice and Reserach, Part 1. Current Problems in Cancer. 2005;29:271–351. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pollak KI, Arnold RM, Jeffreys AS, et al. Oncologist communication about emotion during visits with patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5748–52. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.4180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Derogatis LR, Morrow GR, Fetting J, et al. The prevalence of psychiatric disorders among cancer patients. Jama. 1983;249:751–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.249.6.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davies R, Davis B, Sibert J. Parents’ stories of sensitive and insensitive care by paediatricians in the time leading up to and including diagnostic disclosure of a life-limiting condition in their child. Child Care Health Dev. 2003;29:77–82. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2214.2003.00316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fallowfield L, Jenkins V, Farewell V, et al. Efficacy of a Cancer Research UK communication skills training model for oncologists: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359:650–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07810-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jenkins V, Fallowfield L. Can communication skills training alter physicians’ beliefs and behavior in clinics? J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:765–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.3.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fallowfield L, Jenkins V, Farewell V, et al. Enduring impact of communication skills training: results of a 12-month follow-up. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:1445–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.