Abstract

Fumonisin B1 (FB1) is a mycotoxin that inhibits ceramide synthases (CerS) and causes kidney and liver toxicity and other disease. Inhibition of CerS by FB1 increases sphinganine (Sa), Sa 1-phosphate, and a previously unidentified metabolite. Analysis of the latter by quadrupole-time-of-flight mass spectrometry assigned an m/z = 286.3123 in positive ionization mode, consistent with the molecular formula for deoxysphinganine (C18H40NO). Comparison with a synthetic standard using liquid chromatography, electrospray tandem mass spectrometry identified the metabolite as 1-deoxysphinganine (1-deoxySa) based on LC mobility and production of a distinctive fragment ion (m/z 44, CH3CH=NH +2) upon collision-induced dissociation. This novel sphingoid base arises from condensation of alanine with palmitoyl-CoA via serine palmitoyltransferase (SPT), as indicated by incorporation of l-[U-13C]alanine into 1-deoxySa by Vero cells; inhibition of its production in LLC-PK1 cells by myriocin, an SPT inhibitor; and the absence of incorporation of [U-13C]palmitate into 1-[13C]deoxySa in LY-B cells, which lack SPT activity. LY-B-LCB1 cells, in which SPT has been restored by stable transfection, however, produce large amounts of 1-[13C]deoxySa. 1-DeoxySa was elevated in FB1-treated cells and mouse liver and kidney, and its cytotoxicity was greater than or equal to that of Sa for LLC-PK1 and DU-145 cells. Therefore, this compound is likely to contribute to pathologies associated with fumonisins. In the absence of FB1, substantial amounts of 1-deoxySa are made and acylated to N-acyl-1-deoxySa (i.e. 1-deoxydihydroceramides). Thus, these compounds are an underappreciated category of bioactive sphingoid bases and “ceramides” that might play important roles in cell regulation.

Fumonisins (FB)2 cause diseases of horses, swine, and other farm animals and are regarded to be potential risk factors for human esophageal cancer (1) and, more recently, birth defects (2). Studies of this family of mycotoxins, and particularly of the highly prevalent subspecies fumonisin B1 (FB1) (reviewed in Refs. 1 and 2), have established that FB1, is both toxic and carcinogenic for laboratory animals, with the liver and kidney being the most sensitive target organs (3, 4). Other FB are also toxic, but their carcinogenicity is unknown.

FB are potent inhibitors of ceramide synthase(s) (CerS) (5), the enzymes responsible for acylation of sphingoid bases using fatty acyl-CoA for sphingolipid biosynthesis de novo and recycling pathways (6). As a consequence of this inhibition, the substrates sphinganine (Sa) and, usually to a lesser extent, sphingosine (So), accumulate and are often diverted to sphinganine 1-phosphate (Sa1P) and sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P), respectively (7), while the product N-acylsphinganines (dihydroceramides), N-acylsphingosines (ceramides, Cer), and more complex sphingolipids decrease (5, 7). This disruption of sphingolipid metabolism has been proposed to be responsible for the toxicity, and possibly carcinogenicity, of FB, based on mechanistic studies with cells in culture (5, 7–9). This has been borne out by a number of animal feeding studies that have correlated the elevation of Sa in blood, urine, liver, and kidney with liver and kidney toxicity (4, 7, 10, 11).

Most of the mechanistic studies have focused on the accumulation of free Sa and other sphingoid bases, because these compounds are highly cytotoxic, although the large number of bioactive metabolites in this pathway make it likely that multiple mediators may participate (7, 9). Nonetheless, inhibition of serine palmitoyltransferase (SPT), the initial enzyme of de novo sphingolipid biosynthesis, reverses the increased apoptosis and altered cell growth induced by FB1 treatment (12–19). Therefore, it is likely that these effects of FB1 are due to the accumulation of cytotoxic intermediate(s) rather than depletion of downstream metabolites, because the latter also occurs when SPT is inhibited.

In studies of the effects of FB1 on the renal cell line LLC-PK1 (20),3 we have noted that in addition to the elevation of Sa and So, there is a large increase in an unidentified species that appears to be a sphingoid base, because it is extracted by organic solvents, derivatized with ortho-phthalaldehyde (OPA), and eluted from reverse-phase liquid chromatography (LC) in the sphingoid base region. Herein we report: (i) the isolation and characterization of this novel sphingoid base as 1-deoxysphinganine (1-deoxySa); (ii) that its origin is the utilization of alanine instead of serine by SPT as well as that the N-acyl-derivatives of 1-deoxySa (1-deoxydihydroceramides (1-deoxyDHCer)) are normally found in mammalian cells; (iii) that 1-deoxySa has cytotoxicity comparable to other sphingoid bases elevated by FB1; and (iv) that 1-deoxySa is not only elevated in cells in culture but also in tissues of animals exposed to dietary FB and, therefore, might contribute to diseases caused by these mycotoxins.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials—Pig kidney epithelial cells (LLC-PK1; CL 101), African green monkey kidney cells (Vero cells; CCL 81), and the human prostate cancer cell line (DU-145, HTB-81™) were from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). The LY-B and LY-B-LCB1 cells were a generous gift from Ken Hanada (21). P53N5-W mice, 5–7-week-old, were purchased from Taconic Farms, Inc. (The P53N5 strain was derived originally from the C57BL/6 mouse strain.)

FB1 used in the in vitro studies was prepared and purified (>95% purity) as described in Meredith et al. (22) (establishing that the impurities were primarily other FBs and FB dimers) or for the experiments specified were purchased from Biomol (Philadelphia, PA). FB1 used in the mouse feeding study was supplied by Dr. Marc Savard (Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Ottawa, ON, Canada). Myriocin was prepared as described in Riley and Plattner (23). Free sphingoid bases, sphingoid base 1-phosphates, and the internal standard mixture for sphingolipids (Sphingolipid Mixture II, LM-6005) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL) except for d-erythro-C16-sphingosine, which was from Matreya (Pleasant Gap, PA). 1-DeoxySa was initially synthesized by minor modifications of a recently developed method for the synthesis of So (24) and has subsequently become available commercially from Avanti Polar Lipids.

Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), Hanks' balanced salt solution, and Minimal Essential Medium (MEM, Invitrogen catalogue no. 61100-061) were obtained from GIBCO Invitrogen. Eagles Minimal Essential Medium, Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), Ham's F12, fetal calf serum (FCS), and trypsin/EDTA were obtained from ATCC. l-[U-13C]Alanine, l-[U-13C]serine, and [U-13C]palmitic acid (all ≥98% purity) were purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc. Preparative C18 bulk packing material (55–105 μm) was purchased from Waters (Waters Corp., Part No. WAT010001). Acetonitrile (Burdick & Jackson) and water (J. T. Baker) were high performance LC (HPLC) grade and formic acid (>95%; Sigma-Aldrich) and all other reagents and chemicals were of analytical grade or better and were from various commercial suppliers.

Cell Culture—LLC-PK1 cells were grown and maintained in 25-cm2 culture flasks containing DMEM/Ham's F12 (1:1) with 5% FCS at 37 °C and 5% CO2. For experiments using confluent cultures of LLC-PK1 cells, the cells were seeded at ∼15,000 to 30,000 viable cells/cm2 in 8-cm2 dishes and then allowed to attach and grow to at least 90% confluence (3–5 days) prior to addition of test agents added directly to the media without addition of fresh growth medium. For experiments measuring effects on rapidly proliferating cells, the LLC-PK1 cells were seeded at ∼2,500 viable cells/cm2 in 8-cm2 dishes and allowed to attach and grow for 2 to 3 days (until ∼30% confluent) prior to addition of fresh growth medium containing the various test agents. The seeding density was chosen so that cell number in control cultures increased linearly over the entire experimental time course. Vero cells were grown and maintained in 25-cm2 culture flasks containing Eagles MEM with 10% FCS at 37 °C and 5% CO2. All experiments with Vero cells used rapidly proliferating cells that had been subcultured from confluent cultures at a 1:36 split ratio into 8-cm2 dishes. This split ratio resulted in cultures that were ∼30% confluent after 24 h. The DU-145 cells were grown in Eagles MEM and 10% FCS at 37 °C and 5% CO2 as described in the technical literature from the ATCC. The LY-B and LY-B-LCB1 cells were cultured in medium containing DMEM/Ham's F12 (1:1) with 5% FCS at 37 °C and 5% CO2, essentially as described in Ref. 21.

After treatments, cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS, the dishes placed on ice, and cells removed from the surface of the dishes using a rubber scraper. The cells detached by scraping were collected in polypropylene tubes and pelleted by centrifuging at 4 °C. The PBS was removed, and the cells frozen at –20 °C. Except where noted, cell extracts were normalized by protein amounts, which were determined by the Lowry method (25) and a commercially available kit (Pierce® BCA Protein Assay Kit, Product No. 23225, Thermo Scientific Pierce) using bovine serum albumin (BSA) as the standard.

Sphingolipid Extraction and Analysis—A number of independent methods were used to characterize the sphingolipids to provide confirmation of the findings, and the specific method is indicated in the text and figure legends: 1) Free sphingoid bases were extracted from the cells and quantified by high performance LC (HPLC) and fluorescent detection of the OPA derivatives using C20-sphinganine (C20 Sa) as an internal standard according to Riley et al. (26). 2) Free sphingoid bases and sphingoid base 1-phosphates were also analyzed (in experiments with proliferating and confluent cultures of LLC-PK1 cells, Vero cells, and homogenates of mouse liver and kidney) by LC tandem linear-ion trap electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (LC ESI-MS/MS) using the method of Zitomer et al. (27) except that instead of extracting pulverized freeze-dried tissues, either fresh liver or kidney homogenates (10–20 mg/100 μl phosphate buffer) or cultured cells (50–100 μg protein) were extracted with C16-So and C17-S1P as internal standards. 3) Free sphingoid bases and N-acyl-derivatives were analyzed by minor modifications of published methods (28) to detect compounds with and without the 1-hydroxyl group based on their resolution by LC. For 1-deoxySa, the precursor ion m/z 286.4 and product ion m/z 268.4 (-H2O) in positive ionization mode were followed. (Note: these overlap with ions from other sphingoid bases, such as d17:1; however, these compounds are resolved by LC as described below.) For N-acyl-1-deoxySa, the cell and tissue extracts were first scanned for precursors for m/z 268.4 to identify which N-acyl-derivatives were present. Then they were analyzed by LC ESI-MS/MS using multiple reaction monitoring with Q1 and Q3 set to pass the following precursor and product ions for the designated N-acyl-1-deoxySa. The abbreviations connote the sphingoid base, m18:0, and fatty acid chain length and number of double bonds using standard nomenclature (28): 524.7/268.4 (m18:0/C16:0), 552.7/268.4 (m18:0/C18:0), 580.7/268.4 (m18:0/C20:0), 608.8/268.4 (m18:0/C22:0), 634.9/268.4 (m18:0/C24:1), 636.9/268.4 (m18:0/C24:0), 662.9/268.4 (m18:0/C26:1), and 664.9/268.4 (m18:0/C26:0). The LC ESI-MS/MS of the free sphingoid bases was conducted using reverse phase LC (Supelco 2.1 × 50 mm Discovery C18 column, Sigma) and a binary solvent system at a flow rate of 0.6 ml/min delivered by a Shimadzu LC-10 AD VP binary pump system coupled to an ABI 4000 QTrap (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The binary system began with equilibration of the column with a solvent mixture of 60% mobile phase A (CH3OH/H2O/HCOOH, 58/41/1, v/v/v, with 5 mm ammonium formate) and 40% mobile phase B (CH3OH/HCOOH, 99/1, v/v, with 5 mm ammonium formate), sample injection (typically in 50 μl of the same mixture), elution with this mixture for 1.3 min followed by a linear gradient to 100% B over 2.8 min, and then a column wash with 100% B for 0.5 min followed by a wash and re-equilibration with the original A/B mixture before the next run. The elution times were 2.1 min for C17 So (internal standard), 2.4 min for C18 So, 2.6 min for C18 Sa, and 2.8 min for C18-1-deoxySa, with all having baseline resolution.

The N-acyl-derivatives were analyzed by normal phase LC (Supelco 2.1 × 50 mm LC-NH2 column) at a flow rate of 0.75 ml/min and an isocratic solvent system (CH3CN/CH3OH/CH3COOH/CH3(CH2)3OH/H2O, 95/3/1/0.4/0.3, v/v with 5 mm ammonium acetate) delivered by a Perkin Elmer Series 200 MicroPump system coupled to a PE Sciex API 3000 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Using these LC conditions, the 1-deoxydihydroceramides (1-deoxyDHCer) elute together at 0.3 min and are resolved from ceramides (Cer), which elute at 0.37 min. The settings for the mass spectrometry were optimized for each category of compounds as described previously (28). Quantitation was based on spiking the original extract with the sphingolipid internal standard mixture from Avanti Polar Lipids and comparison of the areas for m18:0 with d17:0 (which were approximately the same based on comparison of d17:0 with synthetic m17:0) and for N-acyl-1-deoxySa, the C12-Cer internal standard. Therefore, although these are close approximations, absolute quantitation will require the availability of MS internal standards for these specific compounds. 4) High resolution accurate mass MS was conducted on an ABI Q-Star (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using samples in methanol infused via a TriVersa nanomate (Advion Biosciences, Ithaca, NY) using a D-chip at 1.5 kV and a gas pressure of 0.2 psi. A total of 30 scans were averaged.

To obtain sufficient quantity of the unidentified sphingoid base for chemical characterization, the free sphingoid bases were partially purified from thirty 75-cm2 flasks of confluent cultures of LLC-PK1 cells that had been treated with 35 μm FB1 for 120 h. The cells were scraped and pooled in a single glass tube, and the free sphingoid bases were extracted and treated with 0.1 m KOH in methanol to decrease interference from glycerolipids as described by Riley et al. (26). The extracted sphingoid bases were dissolved in a small volume of acetonitrile:H2O:formic acid (49.5:49.5:1, v/v/v) and loaded on a minicolumn of preparative C18 packing material (5 mm × 60 mm) equilibrated with the same mobile phase. Free sphingoid bases were eluted by increasing the percentage of acetonitrile, and the fractions that were enriched in the unidentified sphingoid base were identified by LC linear ion trap-ESI-MS/MS, pooled, dried under nitrogen, and stored at –80 °C for later analysis.

Analysis of Stable Isotope-labeled Sphingoid Bases using l-[U-13C]Alanine and l-[U-13C]Serine—Vero cells at ∼30% confluence in 8-cm2 culture plates were incubated in MEM (Invitrogen 61100-061 without serine or alanine) with 2% FCS and 7 amino acid supplements (with 16 dishes per supplement): (i) 100 μm l-serine (natural abundance 13C) + 100 μm l-alanine (natural abundance 13C), (ii) 100 μm l-serine + 100 μm l-[U-13C]alanine, (iii) 100 μm l-serine + 300 μm l-[U-13C]alanine, (iv) 100 μm l-serine + 500 μm l-[U-13C]alanine, (v) 100 μm l-[U-13C]serine + 100 μm l-alanine, (vi) 300 μm l-[U-13C]serine + 100 μm l-alanine, and (vii) 500 μm l-[U-13C]serine + 100 μm l-alanine. After 24 h in culture, half of the dishes in each group were administered sterile FB1 for a final concentration of 35 μm. After 48 h of additional incubation, half of the dishes in each group were used for sphingolipid analysis and half for protein assays. This experiment was repeated twice. Analysis of the sphingolipids in the extracts included m/z for the 12C-labeled products and the [13C] masses of relevant compounds (mass of [12C] parent ion + 2 mass units resulting from incorporation of 2 carbons from the l-[U-13C]amino acid with the third 13C-labeled carbon lost as 13CO2).

Analysis of 1-DeoxySa and Metabolites in LY-B and LY-B-LCB1 Cells—These cell lines were plated in 100-mm culture dishes to ∼50% confluence, and then new medium (a 1:1 mixture of DMEM and Ham's F12 media with 10% FCS) containing 0.1 mm [U-13C]palmitic acid bound to fatty acid-free BSA (as a 1:1 molar complex) was added. After 24 h, the lipids were extracted as described previously (28) and analyzed for the 12C- and 13C-labeled sphingolipids (with the latter having a M+16 or M+32 m/z offset from the 12C-species) using LC ESI-MS/MS as described above.

Effect of Sa and 1-DeoxySa on Cell Growth, Accumulation of Sphingoid Bases, Sphingoid Base 1-Phosphates, Cer, and 1-DeoxyDHCer—As described previously (8, 13), LLC-PK1 cells were grown in 8-cm2 dishes to ∼30% confluence. Then Sa or 1-deoxySa was added as the 1:1 (mol/mol) complex with fatty acid-free BSA with or without addition of FB1 (dissolved in water) at the concentrations described in the text. After 48 h, cell protein was measured (25) for the attached cells, which we have determined to be linearly related to cell number [μg protein = 1.63 + 3.29 × (viable cells × 10–4), r2 = 0.96, n = 53] (8). All experiments were conducted with DMEM/Ham's F12 plus 5% FCS. The effect of treatments on the detachment of cells was determined by collecting the medium and pelleting the detached cells for a separate analysis of the protein amounts. In earlier studies, we have shown that both FB1 and free Sa inhibit cell growth and increase the number of detached cells, which are dead, based on uptake of trypan blue and lactate dehydrogenase release (8, 13, 15). A duplicate set of dishes (n = 3/treatment) was collected for determining changes in endogenous sphingoid bases, sphingoid base 1-phosphates, Cer, and 1-deoxyDHCer by LC-ESI-MS/MS as described previously.

The effects of 1-deoxySa and Sa on DU-145 cells were examined by culturing the cells to ∼25–50% confluence in 24-well dishes, addition of the sphingoid base as a 1:1 (mol:mol) complex with fatty acid-depleted BSA (sterilized by filtration), incubation for 24 h, and then assessment of cell viability using the WST-1 Cell Proliferation Reagent (Roche Applied Science) following the manufacturer's instructions.

Analysis of 1-DeoxySa in Mice Fed FB1—Upon receipt, mice were housed individually under conditions meeting the requirements of the Canadian Council for Animal Care. Similar to the FB feeding protocols described by Gelderblom et al. (29), male mice (n = 10) received a modified AIN 76A diet supplemented with 0–50 mg FB1/kg for 26 weeks, and then were killed under isoflurane anesthesia by cardiac puncture. Liver and kidney tissues were removed as quickly as possible, flash-frozen in liquid N2, and stored at –80 °C until used for sphingolipid analysis.

RESULTS

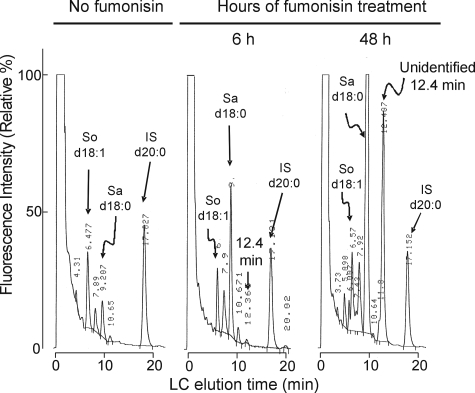

FB1 Elevates Sa and a Mystery Peak in Cells—Shown in Fig. 1 are representative reverse phase HPLC profiles of the amounts of free sphingoid bases detected as the OPA derivatives from LLC-PK1 cells that have or have not been exposed to 50 μm FB1. As has been seen before (20), FB1 treatment increased the amount of Sa by severalfold within 6 h, and by orders of magnitude after 48 h. In addition, a new and unidentified peak with an elution time of 12.4 min is noticeable after 6 h of FB1 treatment, and by 48 h, the area under the curve for this “mystery peak” is nearly half of that for Sa. Several additional peaks can be seen in the extracts from the cells treated with FB1, but these were much smaller and were not examined further. This phenomenon was not limited to LLC-PK1 cells because we have seen this mystery peak in almost every cell line that we have treated with FB1 (which have included Vero cells, J774 cells, HT29 cells, HEK293 cells, inter alia) (data not shown).

FIGURE 1.

Representative chromatograms of lipid extracts from confluent cultures of LLC-PK1 cells treated with FB1 and analyzed by HPLC with fluorescence detection of the free sphingoid bases as the OPA derivatives using C20-Sa as an internal standard (26). In each case, the extracts were from ∼120 μg of total protein; the left chromatogram is for cells cultured in medium containing no FB versus cultures exposed to 50 μm FB1 for 6 (middle) and 48 h (right). Identifications are based on comparison with standards for So (d18:1), Sa (d18:0), and the added C20 Sa (d20:0) internal standard (IS). The unidentified species elutes at 12.4 min.

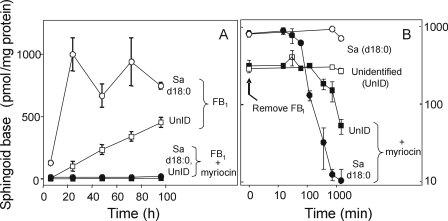

Evidence That the Mystery Peak Is an Unidentified Sphingoid Base—Based on its extraction by organic solvents, derivatization by OPA and LC mobility, it was likely that the mystery peak was a novel sphingoid base. If so, its production should be blocked by myriocin (also called ISP1), which is a potent inhibitor of SPT (30), the initial enzyme of de novo sphingolipid biosynthesis. As shown in Fig. 2A, treatment of LLC-PK1 cells concurrently with myriocin blocked the FB1-induced elevation of Sa and the unidentified sphingoid base. Furthermore, if the cells were first treated with FB1 for 48 h to elevate Sa and this unidentified species (labeled as time 0 in Fig. 2B), followed by changing the cells to new medium minus FB1 with or without myriocin, the presence of the SPT inhibitor greatly accelerated the decline in both free Sa and the unidentified sphingoid base (Fig. 2B). The slow decline in Sa and the unidentified compound in Fig. 2B when FB1 was removed (but myriocin not added, hence, the cells continue to synthesize Sa de novo) suggests that partial inhibition of CerS persists for awhile. This is consistent with the results of an earlier study showing that the efflux of [U-14C]FB1 from LLC-PK1 cells was rapid (half-life 2–3 min); however, a low but persistent amount of [14C] remained associated with the cells (31).

FIGURE 2.

Changes in free Sa (d18:0) and the unidentified sphingoid base (UnID) in confluent cultures of LLC-PK1 cells treated with FB1 and/or myriocin. Panel A shows the amounts of these free sphingoid bases in cells exposed to 35 μm FB1 for various times (white circles and squares) or FB1 plus myriocin (black circles and squares). Panel B shows the reversibility of these elevations when LLC-PK1 cells were exposed for 48 h to FB1 followed by a change to fresh medium without FB1 (at time 0) but with (black circles and squares) or without myriocin (white circles and squares). The free sphingoid bases were analyzed by HPLC with fluorescence detection of the free sphingoid bases as OPA derivatives using C20-Sa (d20:0) as an internal standard (26). The data are the mean ± S.D. from three independent experiments.

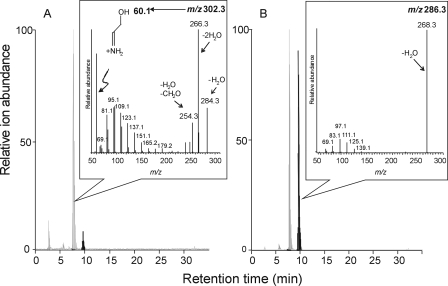

Identification of the Novel Sphingoid Base as 1-DeoxySa (m18:0)—The mystery peak was initially characterized by examining the partially purified extracts from LLC-PK1 cells (as described under “Experimental Procedures”) using a quadrupole-time of flight mass spectrometer (ABI QStar), which established that the samples contained an [M+H]+ ion of m/z 286.3123 (data not shown), for which the only plausible formula within 10 ppm is C18H40NO (286.3104), which is consistent with either a 1 or 3-deoxySa.

Using this information, lipid extracts from LLC-PK1 cells treated with FB1 for 25 h (Fig. 3A) and 120 h (Fig. 3B) were analyzed by reverse-phase LC ESI MS/MS monitoring for the [M+H]+ ions for Sa (m/z 302.3, light gray lines) and deoxySa (m/z 286.3, dark gray lines). Consistent with the results in Fig. 1, Sa eluted first (identified by both precursor m/z 302.3 and the known product ion spectrum for Sa, shown in the inset in panel A) (32) followed by deoxysSa (m/z 286.3), which was more highly elevated at 120 h (panel B) than at 25 h (panel A), consistent with the results shown in Fig. 2. Furthermore, the product ion spectrum for the m/z 286.3 peak was consistent with a compound with only one hydroxyl group (i.e. a deoxySa) because it displayed loss of one H2O (m/z 268, inset in Fig. 3B), whereas Sa produced both single and double dehydration products (Fig. 3A).

FIGURE 3.

Liquid chromatography of LLC-PK1 cell extracts after 24 h (A) and 120 h (B) of treatment with FB1 with monitoring for Sa and a novel sphingoid base by electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Free sphingoid bases were extracted from 100% confluent cultures (50–100μg of protein) using the method of Riley et al. (26) but without the addition of an internal standard. The chromatograms display the combined ion intensities for Sa (m/z 302.2, the gray major peak) and the unidentified sphingoid base (m/z 286.3, the black major peak), which eluted at retention times of ∼8 and 10 min, respectively. The insets are the product ion spectra for the eluted precursor m/z 302.2 (inset in A) and 286.3 (inset in B). Highlighted in A is a distinctive fragment for Sa (m/z 60. 1) that is not produced from m/z 286.3 (B).

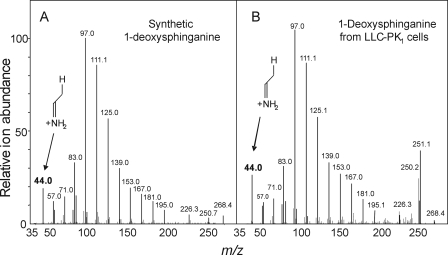

It is also noteworthy that the product ion spectrum for the deoxySa lacks the m/z 60.1 product ion that is obtained from fragmentation between carbons 2 and 3 of the sphingoid base (see inset for Fig. 3A) because this implies that the deoxySa lacks the 1-hydroxyl group. To study this further, the MS3 spectra were compared for synthetic 1-deoxySa (Fig. 4A) and the compound partially purified from LLC-PK1 cells (Fig. 4B), and both contained the m/z 44.0 ion predicted for fragmentation between carbons 2 and 3 of a 1-deoxySa. Therefore, based on these criteria, we tentatively identified the mystery peak produced by cells incubated with FB1 as 1-deoxySa.

FIGURE 4.

Comparison of the MS3 spectra for synthetic 1-deoxySa (A) and the deoxySa isolated from LLC-PK1 cell extracts (B) using the method of Riley et al. (26) with subsequent partial purification on a minicolumn of preparative C18 packing material (5 mm × 60 mm); fractions enriched in the deoxySa were pooled for analysis. The samples were introduced into a Thermo Electron Corporation LTQ XL via syringe pump and scanned across the mass range shown for the MS3 fragments from the single dehydration product (m/z 268) of deoxySa. Highlighted is the distinctive fragment for 1-deoxySa at m/z 44.

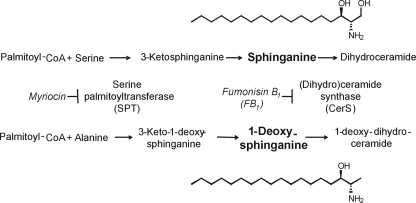

Biosynthesis of 1-DeoxySa from [13C]Alanine by SPT—Because myriocin blocked the formation of 1-deoxySa in FB1-treated cells (Fig. 2), it is possible that this compound arises from the condensation of l-alanine with palmitoyl-CoA by SPT as illustrated in Fig. 5. To test this hypothesis, proliferating cultures of Vero cells were grown in medium supplemented with varying ratios of natural abundance and l-[U-13C]alanine and l-[U-13C]serine. Vero cells were chosen for this experiment because they produced easily detectable levels of the deoxySa in control cultures and were somewhat more resistant to the growth inhibitory effects of FB1 in short term assays compared with the LLC-PK1 cells (in addition, culture medium without serine or alanine is also available commercially for these cells). The appearance of stable isotope-labeled 1-deoxySa and Sa were monitored by MS analysis of the products that have been produced from these precursors by the M+2 isotope shift (since one 13C of each amino acid is lost as 13CO2 in the condensation reaction). The experiment was designed with addition of both precursors because serine and alanine can be metabolically interconverted (albeit, with many intermediate steps) as well as incorporated into the co-substrate palmitoyl-CoA. Therefore, addition of the unlabeled amino acid should diminish the contribution from such 13C-labeled metabolites.

FIGURE 5.

Structures of Sa and 1-deoxySa and a scheme for the biosynthesis of 1-deoxySa and its accumulation in cells exposed to FB1. Also shown are the known sites of inhibition by FB1 and myriocin.

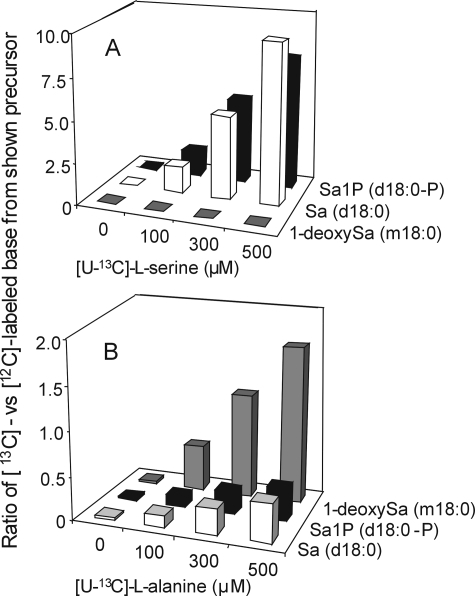

As shown in Fig. 6A, essentially none of the l-[U-13C]serine was incorporated into 1-deoxySa but was preferentially incorporated into [13C]Sa (d18:0) and [13C]Sa1P (d18:0-P) (Fig. 6A). Conversely, l-[U-13C]alanine was preferentially incorporated into 13C-labeled 1-deoxySa (m18:0) (Fig. 6B) versus Sa and Sa1P.

FIGURE 6.

Incorporation of l-[U-13C]alanine (A) and l-[U-13C]serine precursors (B) into the 1-deoxySa (m18:0), Sa (d18:0), and Sa1P (d18:0-P) in Vero cells treated with 35 μm FB1 for 48 h and grown in medium containing increasing concentrations of either l-[U-13C]alanine- or l-[U-13C]serine(100 μm to 500 μm). The control (0) contained 35 μm FB1 and both [U-12C]alanine and [U-12C]serine were at 100 μm each. All other treatments contained both alanine and serine; however, while the concentration of l-[U-13C]alanine and l-[U-13C]serine ranged from 100 to 500 μm the other l-[12C]amino acid (alanine or serine) was maintained at 100 μm. Free sphingoid bases and sphingoid base 1-phosphates were extracted from the proliferating (50–80% confluent after 48 h) cultures (50–150 μg of protein) using the method of Zitomer et al. (27). The 13C-labeled deoxySa (m/z 288), Sa (m/z 304), Sa1P (m/z 384), and [12C, natural abundance 13C] species of 1-deoxySa (m/z 286), Sa (m/z 302), and Sa1P (m/z 382) were analyzed using LC ion trap-ESI-MS and the mean of the results from four replicate dishes are expressed as the ratio of the amount of 13C-labeled compound/12C-labeled compound. The standard deviations were all less than 5% of the mean values and are therefore not shown.

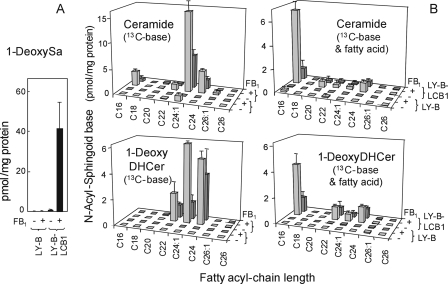

The utilization of l-alanine by SPT is surprising, although there has been a recent report of 1-deoxySa in Hek293 cells that express the mutant form of SPTLC1 that is found in human sensory neuropathy type 1 (HSN1) as well as in lymphoblast lines derived from HSN1 patients (33). Therefore, to determine if SPT is responsible for 1-deoxySa biosynthesis in these cells, the incorporation of [U-13C]palmitate into the sphingoid base backbones of sphingolipids and 1-deoxySa was analyzed using LY-B cells, a mutant Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cell line with undetectable SPT activity due to mutation of the SPT1 subunit (21). As shown in Fig. 7, there was no detectable incorporation of 13C-label into 1-deoxySA by LY-B cells with or without addition of FB1 (panel A), but when LY-B-LCB1 cells were used (which have restoration of SPT activity by stable transfection with the cDNA for SPT1), there is a low but detectable incorporation of [13C]palmitate into 1-deoxySa in these cells and robust biosynthesis and accumulation of 1-[13C]deoxySa when the cells were treated with FB1 (Fig. 7, panel A).

FIGURE 7.

Absence of 1-deoxySa biosynthesis by LY-B cells and restoration of its formation in LY-B-LCB1 cells. Shown are the amounts of 1-[13C]deoxySa (panel A) and 13C-backbone-labeled ceramides and 1-deoxy-DHCer (panel B)(i.e. with [13C] in the backbone only: labeled 13C-base, or both the backbone and the fatty acid, labeled 13C-base & fatty acid) that are produced by LY-B and LY-B-LCB1 cells. The cells were incubated with 0.1 mm [U-13C]palmitate as the 1:1 complex with BSA for 24 h. For comparison with earlier findings with FB1 treatment, the indicated groups were also treated with 25 μm FB1. Then the sphingolipids were extracted and analyzed by LC-ESI-MS/MS as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Each treatment was conducted in triplicate, and the results shown are means ± S.D., n = 3.

In addition, there was essentially no biosynthesis of Cer or N-acyl-1-deoxySa (1-deoxyDHCer) in LY-B cells (the first two rows of all of the graphs in Fig. 7, panel B). In contrast, LY-B-LCB1 cells incorporated [13C]palmitate into the sphingoid base backbone (labeled 13C-base in Fig. 7B) and into both the sphingoid base and fatty acid (labeled 13C-base and fatty acid in Fig. 7B) of Cer (upper two graphs of Fig. 7B) and 1-deoxyDHCer (lower two graphs of Fig. 7B). In addition, FB1 decreased the formation of these compounds, consistent with the accumulation of free 1-deoxySa (Fig. 7A). In this experiment, 1-deoxyDHCer was not a minor species because when all of the subspecies are summed, the amount of 1-[13C]deoxyDHCer is about one-third of the amount of [13C]Cer. However, the kinetics of Cer metabolism may be quite different because 1-deoxyDHCer cannot undergo head group addition. Future studies will need to compare the relative rates of the two arms of the pathway. Nonetheless, all in all, these results establish that the formation of 1-deoxySa requires SPT, and when formed, most appears to be acylated unless FB1 is present.

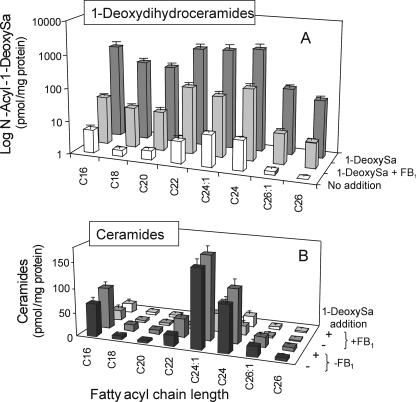

Endogenous 1-DeoxyDHCer and Acylation of Exogenously Added 1-DeoxySa in LLC-PK1 Cells—The results with the LY-B and LY-B-LCB1 cells (Fig. 7) suggest that the accumulation of 1-deoxySa in LLC-PK1 cells treated with FB1 is due to interruption of the formation of endogenous 1-deoxyDHCer. To test this prediction, the amounts and types of 1-deoxyDHCer and Cer of LLC-PK1 cells were analyzed by LC-ESI-MS/MS. As shown in Fig. 8A, control (no addition) LLC-PK1 cells contain on average 32 ± 4 pmol of 1-deoxyDHCer/mg protein that are distributed among a variety of fatty acyl chain lengths that are similar to that of the Cer in the cells (Fig. 8B). In addition, when the cells were treated with 10 μm 1-deoxySa and analyzed after 48 h, they contained highly elevated amounts of 1-deoxyDHCer (4,630 ± 396 pmol/mg protein) that were >90% suppressed if the cells were also treated with 50 μm FB1 (Fig. 8A). The addition of 10 μm 1-deoxySa did not appear to have any effect on the amount of ceramide (in contrast the FB1 alone or in combination with 1-deoxySa caused a major suppression of Cer accumulation (Fig. 8B). Therefore, the findings with LLC-PK1 cells were similar to what was observed with the LY-B-LCB1 cells, i.e. it appears that cells make a substantial amount of 1-deoxySa that is acylated to 1-deoxyDHCer.

FIGURE 8.

Endogenous N-acyl-sphingoid bases in LLC-PK1 cells and after incubation of the cells with exogenously added 1-deoxySa with or without FB1. LLC-PK1 cells incubated for 48 h in growth medium supplemented with vehicle only, 10 μm 1-deoxySa, 50 μm FB1, or 10 μm 1-deoxySa plus 50 μm FB1 followed by analysis of the 1-deoxydihydroceramides (panel A) and ceramides (panel B) by LC ESI-MS/MS as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Each treatment was conducted in triplicate, and the results shown are means ± S.D., n = 3.

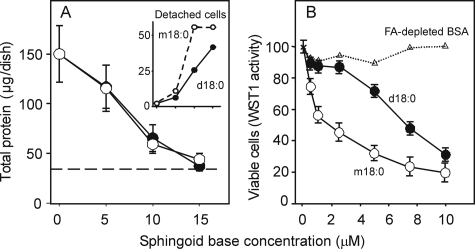

Cytotoxicity of 1-DeoxySa—The toxicity of free sphingoid bases (typically added to cells as the complex with BSA) is well-known (13, 34), and has been demonstrated previously in LLC-PK1 cells as a model for FB toxicity (13). The effect of 1-deoxySa on these cells was determined using the chemically synthesized compound as the BSA complex (Fig. 9A) versus the effect of a Sa-BSA complex. Both compounds are equally cytotoxic both in terms of decreased cell growth and an increased number of detached-dead cells based on their inability to exclude trypan blue (Fig. 9A, inset). Because 1-deoxySa has been reported to be cytotoxic for cancer cell lines (34), we also examined its effect on the human prostate cancer cell line DU-145 using the WST-1 cell proliferation assay. As shown in Fig. 9B, 1-deoxySa was severalfold more potent (IC50 ∼ 2 μm) than Sa (IC50 ∼ 7 μm) for this cancer cell line.

FIGURE 9.

Effects of 1-deoxySa on LLC-PK1 and DU-145 cells. Panel A shows the decrease in cell growth and increase in detached cells in proliferating cultures of LLC-PK1 cells treated for 48 h with increasing concentrations of Sa (black circles, d18:0) or 1-deoxySa (white circles, m18:0) administered as the BSA complex. The values are the total protein content of the dishes (mean ± S.D., n = 3) at each concentration after 48 h. The dashed line is the average protein content (n = 3) of the dishes at the time (t = 0) that the treatment began. The inset shows the total protein content of detached cells expressed as a percentage of the total protein content of attached cells for each treatment. Detached cells were dead, based on their inability to exclude trypan blue. Panel B shows the effect on DU-145 cells as measured by the WST-1 cell proliferation assay with 100% reflecting the absorbance of the WST-1 reagent after incubation with the untreated DU-145 cells. Also shown are the results for dishes where BSA alone was added, triangles and dotted line. Each data point is the mean ± S.D. for three different wells.

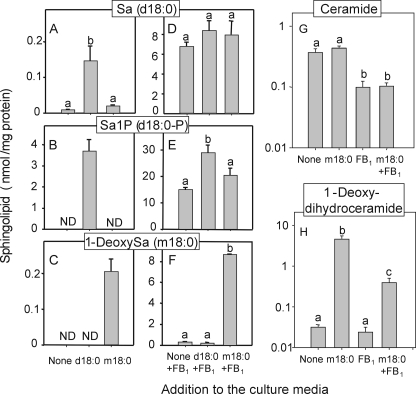

Analysis of the amounts of Sa, Sa1P, and 1-deoxySa in the LLC-PK1 cells treated with the 10 μm Sa (labeled d18:0 in Fig. 10, A–C) revealed that although there was a significant increase in intracellular Sa (Fig. 10A) compared with the control, the species that was present in the highest amount (∼4 nmol/mg protein, a 27-fold increase) was Sa1P (Fig. 10B), indicating that a large fraction of added Sa undergoes phosphorylation. 1-DeoxySa was also easily detected in the cells exposed to 10 μm 1-deoxySa (labeled m18:0 in Fig. 10C), and the amount was similar to the Sa in Sa-treated cells (∼0.2 nmol/mg protein, Fig. 10, A and C). 1-DeoxySa was not detected in the control cells (nor cells treated with Sa), nor was it phosphorylated (data not shown), which is expected since sphingosine kinase adds a phosphate to the hydroxyl group at carbon position 1.

FIGURE 10.

Accumulation of Sa (A and D), Sa1P (B and E), 1-deoxySa (C and F), and decrease in ceramide (G) and change in 1-deoxydihydroceramide (H) levels in LLC-PK1 cells treated as described in Fig. 9 but only at the 10 μm concentration of Sa and 1-deoxySa (A–C) or in combination with 50 μm FB1 (D–F). Free sphingoid bases and sphingoid base 1-phosphates were extracted from the proliferating (50–90% confluent after 48 h) cultures (50–100 μg of protein) using the method of Zitomer et al. (27). The values are the means ± S.D. (n = 3 replicate 8-cm2 dishes). Mean values with differing letters are significantly different among groups based on one way analysis of variance; ND, not detected.

Co-administration of Sa and FB1 caused large increases in Sa1P versus those obtained with addition of Sa or FB1 alone (Fig. 10, B and E); in contrast, the cellular amounts of Sa, while highly elevated, were not significantly different (Fig. 10D). Treatment with FB1 alone or FB1 plus 10 μm Sa caused a small but significant elevation in 1-deoxySa compared with the control (labeled none); however, co-administration of 1-deoxySa and FB1 caused a >25-fold elevation in 1-deoxySa compared with treatment with only 1-deoxySa or FB1 alone (Fig. 10, F and C). This provides further evidence that cells have a large capacity to acylate exogenous as well as endogenous 1-deoxySa. This was also evident in the large increase in 1-deoxyDHCer when 1-deoxySa was added to the cells (Fig. 10H).

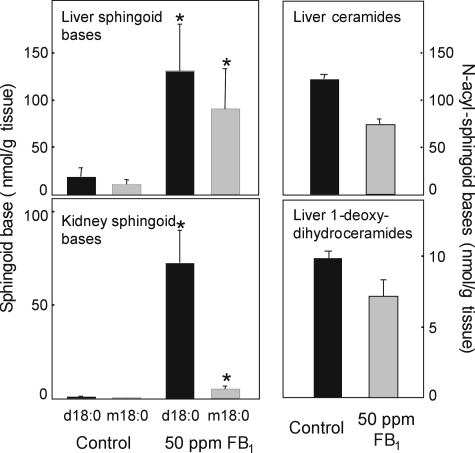

Analysis of 1-DeoxySa in Liver and Kidneys of Mice Fed FB1—To determine if 1-deoxySa is elevated in the target organs for FB toxicity (liver and kidney for mice) (35), male P53N5-W mice were fed 50 ppm FB1 in a modified AIN-76A diet for 6 months, and then lipid extracts from the livers and kidneys were analyzed by LC-ESI-MS/MS (Fig. 11). These analyses showed the typical elevation of Sa by FB1 treatment for both organs (34), as well as the presence of substantial amounts of 1-deoxySa in the FB1-fed mice, with the highest amount in liver. Given the similarity in the amounts of Sa and 1-deoxySa in liver, it is feasible that both compounds contribute to the toxicity of FB for this organ.

FIGURE 11.

Accumulation of Sa (d18:0, black bars) and 1-deoxySa (m18:0, gray bars) in liver (upper) and kidneys (lower) of male P53N5-W mice fed a modified AIN-76A diet containing 0 ppm (Control) or 50 ppm FB1 for 6 months. Free sphingoid bases were extracted from liver and kidney homogenates (20 mg of fresh weight) and analyzed by the method of Zitomer et al. (27). Shown are means ± S.D. for five mice per group (n = 5); an asterisk (*) indicates that the mean is significantly (p < 0.05) elevated compared with the corresponding control group. Also shown are the total average amounts (± the range) of ceramides and 1-deoxydihydroceramides in livers from two mice in each group (right panels).

DISCUSSION

These studies have established that the mystery peak that we described in FB-treated cells almost a decade ago (20) is 1-deoxySa, a novel sphingoid base that is biosynthesized by SPT via the condensation of palmitoyl-CoA with l-alanine. It is surprising that this compound has not been more widely noted in mammalian cells; however, its presence as mainly the N-acyl-derivatives makes it difficult to detect in the much larger pool of cellular Cer and other neutral lipids.

This compound and other 1-deoxysphingoid bases are known to be made by other organisms (36), but have only recently surfaced in mammalian cells in studies of a mutation in the SPTLC1 gene that causes HSN1 (33). However, because our studies have found substantial amounts of these compounds in mammalian cell lines not thought to have a defect in SPT, it is evident that 1-deoxySa and 1-deoxyceramides are normally made by mammals. This does not rule out the possibility that abnormal elevations in 1-deoxySa by a mutant SPTLC1, or due to inhibition of its acylation by FB, could cause cytotoxicity.

The rapid and extensive acylation of 1-deoxySa is not surprising since studies of the structural requirements of sphingoid bases as substrates and inhibitors of CerS had previously shown that this compound was acylated (37). In LY-B-LCB1 cells FB1 caused a much larger increase in 1-deoxySa (40 pmol/mg protein) than can be accounted for solely by the levels of 1-deoxyDHCer in the untreated cells. The precise fate of 1-deoxySa is not known and raises interesting questions about the subsequent metabolism and functions of these compounds since 1-deoxyDHCer might be desaturated to 1-deoxyceramides,4 but none of the usual downstream complex sphingolipids (sphingomyelins, ceramide 1-phosphates or hexosylceramides) can be made. Furthermore, the free sphingoid base cannot undergo phosphorylation, which is a prerequisite step for catabolism of So and Sa via S1P lyase (38). Therefore, there must be alternative mechanisms for elimination of this category of sphingoid bases that are not yet understood.

The cytotoxicity of 1-deoxySa is similar to that previously seen for sphingoid bases (39), although the findings with DU-145 cells indicate that removal of the 1-hydroxyl-group has enhanced the potency somewhat. It is possible that some of the biological effects of 1-deoxySa occur after its metabolism to 1-deoxyDHCer, or due to interference with the metabolism of another sphingolipid, such as by inhibition of sphingosine kinase. However, the finding that addition of 1-deoxySa to LLC-PK1 cells did not decrease the ability of FB1 to elevate Sa1P (Fig. 10E) indicates that it does not eliminate sphingoid base phosphorylation, although its effects might be more pronounced under other circumstances.

The high amounts of 1-deoxysphingolipids in liver versus kidney (Fig. 11) is reminiscent of the greater sensitivity of liver to FB1-induced toxicity in mice (3). We have analyzed a number of tissues from other fumonisin-treated animals, such as liver and kidneys from Sprague-Dawley rats, several strains of mice and pigs (data not shown), and, so far, the highest amounts of 1-deoxySa and 1-deoxyDHCer have been found in P53N5 mice. It would be interesting to know if this species, which was derived originally from the C57BL/6 mouse, has structural differences in SPT that cause it to produce higher amounts of 1-deoxySa, in analogy to the HSN1 mutation (33).

We have noted also that the appearance of 1-deoxySa in cells in culture increases with the length of time that they have been left in culture (Figs. 2 and 3). This might be related to whether or not they are growing because we have not noted significant amounts in rapidly proliferating LLC-PK1 cells (8, 13), whereas, confluent cultures of LLC-PK1 cells left in medium for several days have amounts of 1-deoxySa that approach the levels of Sa (Figs. 2 and 3), and 1-deoxyCer that can be higher than Cer (Fig. 8). To some extent, this is probably due to the lack of downstream metabolism of these compounds, but another factor might be greater formation of 1-deoxySa after the medium and cells become depleted of serine relative to alanine. Indeed, we were easily able to detect 1-deoxySa in Vero cells even without treatment with FB1 (data not shown), and Vero cells are known to rapidly deplete serine from culture medium (40). Thus, one can envision how SPT might serve as a sensor for changes in the ratios of serine and alanine by producing alternative categories of sphingoid bases with different metabolic fates, effects on membrane structure, cell signaling (41), and (or) interaction with nuclear receptors that bind sphingosine (42).

Acknowledgments

We thank Thorsten Hornemann for discussions concerning the finding of 1-deoxysphinganine in cell culture models for HSN1 and Jency Showker for excellent technical support.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants GM76217 and GM69338 (LIPID MAPS) (to A. H. M., H. P., and M. C. S.) and GM066153 (to E. C. G.-A. and L. S. L.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: FB, fumonisins; 1-deoxySa, 1-deoxysphinganine; Cer, ceramide; CerS, ceramide synthases; d18:0, sphinganine; DHCer, dihydroceramide; 1-deoxyDHCer, 1-deoxydihydroceramide; ESI, electrospray ionization; HSN1, human sensory neuropathy type 1; LC ESI-MS/MS, liquid chromatography, electrospray tandem mass spectrometry; m18:0, 1-deoxysphinganine; OPA, ortho-phthalaldehyde; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; Sa, sphinganine; Sa1P, sphinganine 1-phosphate; So, sphingosine; S1P, sphingosine 1-phosphate; SPT, serine palmitoyltransferase; HPLC, high performance LC; DMEM, Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium; FCS, fetal calf serum; BSA, bovine serum albumin.

R. Riley, unpublished observations.

Preliminary investigations have observed species with the appropriate LC elution time and m/z to be the desaturated product. Furthermore, small amounts of 1-desoxymethylsphinganine (m17:0), which would be produced by condensation of palmitoyl-CoA and glycine, have also been noted. Definitive characterization of these other metabolites awaits the availability of synthetic standards.

References

- 1.Marasas, W. F. O. (2001) Environ. Health Perspect. 109 239–243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marasas, W. F. O., Riley, R. T., Hendricks, K. A., Stevens, V. L., Sadler, T. W., Gelineau-van Waes, J. B., Missmer, S. A., Cabrera, J., Torres, O., Gelderblom, W. C. A., Allgood, J., Martinez, C., Maddox, J., Miller, J. D., Starr, L., Sullards, M. C., Roman, A. V., Voss, K. A., Wang, E., and Merrill, A. H., Jr. (2004) J. Nutr. 134 711–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Voss, K. A., Riley, R. T., Norred, W. P., Bacon, C. W., Meredith, F. I., Howard, P. C., Plattner, R. D., Collins, T. F. X., Hansen, D. K., and Porter, J. K. (2001) Environ. Health Perspect. 109 259–266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.NTP Technical Report (2002). NIH Publication No. 99-3955

- 5.Wang, E., Norred, W. P., Bacon, C. W., Riley, R. T., and Merrill, A. H., Jr. (1991) J. Biol. Chem. 266 14486–14490 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pewzner-Jung, Y., Ben-Dor, S., and Futerman, A. H. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 25001–25005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Riley, R. T., Enongene, E., Voss, K. A., Norred, W. P., Meredith, F. I., Sharma, R. P., Williams, L. D., Carlson, D. B., Spitsbergen, J., and Merrill, A. H., Jr. (2001) Environ. Health Perspect. 109 301–308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoo, H. S., Norred, W. P., Wang, E., Merrill, A. H., Jr., and Riley, R. T. (1992) Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 114 9–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merrill, A. H. Jr., Sullards, M. C., Wang, E., Voss, K. A., and Riley, R. T. (2001) Environ. Health Perspect. 109 283–289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Delongchamp, R. R., and Young, J. F. (2001) Food Additiv. Contam. 18 255–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Riley, R. T., and Voss, K. A. (2006) Toxicol. Sci. 92 335–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schroeder, J. J., Crane, H. M., Xia, J., Liotta, D. C., and Merrill, A. H., Jr. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269 3475–3481 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoo, H. S., Norred, W. P., Showker, J. L., and Riley, R. T. (1996) Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 138 211–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmelz, E. M., Dombrink-Kurtzman, M. A., Roberts, P. C., Kozutsumi, Y., Kawasaki, T., and Merrill, A. H., Jr. (1998) Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 148 252–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riley, R. T., Voss, K. A., Norred, W. P., Bacon, C. W., Meredith, F. I., and Sharma, R. P. (1999) Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 7 109–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tolleson, W. H., Couch, L. H., Melchior, W. B. Jr., Jenkins, G. R., Muskhelishvili, M., Muskhelishvili, L., McGarrity, L. J., Domon, O. E., Morris, S. M., and Howard, P. C. (1999) Int. J. Oncol. 14 833–843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim, M. S., Lee, D. Y., Wang, T., and Schroeder, J. J. (2001) Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 176 118–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu, C. H., Lee, Y. M., Yum, Y. P., and Yoo, H. S. (2001) Arch. Pharmacal. Res. 24 136–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He, Q., Riley, R. T., and Sharma, R. P. (2002) Pharmacol. Toxicol. 90 268–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riley, R. T., Voss, K. A., Norred, W. P., Sharma, R. P., Wang, E., and Merrill, A. H., Jr. (1998) Rev. Méd. Vét. 149 617–626 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanada, K., Hara, T., Fukasawa, M., Yamaji, A., Umeda, M., and Nishijima, M. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273 33787–33794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meredith, F. I., Bacon, C. W., Plattner, R. D., and Norred, W. P. (1996) J. Ag. Food Chem. 44 195–198 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Riley, R. T., and Plattner, R. D. (2000) Methods Enzymol. 311 348–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang, H., and Liebeskind, L. S. (2007) Org. Lett. 9 2993–2995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lowry, O. H., Rosenbrough, N. J., Farr, A. L., and Randall, R. J. (1951) J. Biol. Chem. 193 265–275 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riley, R. T., Norred, W. P., Wang, E., and Merrill, A. H., Jr. (1999) Nat. Tox. 7 407–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zitomer, N. C., Glenn, A. E., Bacon, C. W., and Riley, R. T. (2008) Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 391 2257–2263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merrill, A. H., Jr., Sullards, M. C., Allegood, J. C., Kelly, S., and Wang, E. (2005) Methods 36 207–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gelderblom, W. C. A., Cawood, M. E., Snyman, S. D., and Marasas, W. F. O. (1994) Carcinogenesis 15 209–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miyake, Y., Kozutsumi, Y., Nakamura, S., Fujita, T., and Kawasaki, T. (1995) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 211 396–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Enongene, E. N., Sharma, R. P., Bhandari, N., Meredith, F. I., Voss, K. A., and Riley, R. T. (2002) Toxicol. Sci. 67 173–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sullards, M. C., Allegood, J. C., Kelly, S., Wang, E., Haynes, C. A., Park, H., Chen, Y., and Merrill, A. H., Jr. (2007) Methods Enzymol. 432 83–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hornemann, T., Penno, A., and von Eckardstein, A. (2008) Chem. Phys. Lipids 154S S63, PO 111 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sánchez, A. M., Malagarie-Cazenave, S., Olea, N., Vara, D., Cuevas, C., and Díaz-Laviada, I. (2008) Eur. J. Pharmacol. 584 237–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsunoda, M., Sharma, R. P., and Riley, R. T. (1998) J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 12 281–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pruett, S. T., Bushnev, A., Hagedorn, K., Adiga, M., Haynes, C. A., Sullards, M. C., Liotta, D. C., and Merrill, A. H., Jr. (2008) J. Lipid Res. 49 1621–1639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Humpf, H. U., Schmelz, E. M., Meredith, F. I, Vesper, H., Vales, T. R., Wang, E., Menaldino, D. S., Liotta, D. C., and Merrill, A. H., Jr. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273 19060–19064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fyrst, H., and Saba, J. D. (2008) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1781 448–458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stevens, V. L, Nimkar, S., Jamison, W. C., Liotta, D. C., and Merrill, A. H., Jr. (1990) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1051 37–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Quesney, S., Marc, A., Gerdil, C., Gimenez, C., Marvel, J., Richard, Y., and Meignier, B. (2003) Cytotechnology 42 1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zheng, W., Kollmeyer, J., Symolon, H., Momin, A., Munter, E., Wang, E., Kelly, S., Allegood, J. C., Liu, Y., Peng, Q., Ramaraju, H., Sullards, M. C., Cabot, M., and Merrill, A. H., Jr. (2006) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1758 1864–1884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Urs, A. N., Dammer, E., Kelly, S., Wang, E., Merrill, A. H. Jr., and Sewer, M. B. (2006) Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 265–266 174–178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]