Abstract

The physical properties that govern the waterborne transmission of Toxoplasma gondii oocysts from land to sea were evaluated and compared to the properties of carboxylated microspheres, which could serve as surrogates for T. gondii oocysts in transport and water treatment studies. The electrophoretic mobilities of T. gondii oocysts, lightly carboxylated Dragon Green microspheres, and heavily carboxylated Glacial Blue microspheres were determined in ultrapure water, artificial freshwater with and without dissolved organic carbon, artificial estuarine water, and artificial seawater. The surface wettabilities of oocysts and microspheres were determined using a water contact angle approach. Toxoplasma gondii oocysts and microspheres were negatively charged in freshwater solutions, but their charges were neutralized in estuarine water and seawater. Oocysts, Glacial Blue microspheres, and unwashed Dragon Green microspheres had low contact angles, indicating that they were hydrophilic; however, once washed, Dragon Green microspheres became markedly hydrophobic. The hydrophilic nature and negative charge of T. gondii oocysts in freshwater could facilitate widespread contamination of waterways. The loss of charge observed in saline waters may lead to flocculation and subsequent accumulation of T. gondii oocysts in locations where freshwater and marine water mix, indicating a high risk of exposure for humans and wildlife in estuarine habitats with this zoonotic pathogen. While microspheres did not have surface properties identical to those of T. gondii, similar properties shared between each microsphere type and oocysts suggest that their joint application in transport and fate studies could provide a range of transport potentials in which oocysts are likely to behave.

The zoonotic protozoal parasite Toxoplasma gondii is emerging as an important waterborne pathogen in both human and wildlife populations. Contaminated water supplies have been implicated as the sources of infection for human toxoplasmosis outbreaks in several countries, including Panama, Brazil, India, French Guyana, and Canada (2, 4, 7, 12, 43). While T. gondii is usually associated with subclinical or mild flu-like symptoms in immunocompetent individuals, this parasite causes potentially fatal encephalitis in immunosuppressed patients, as well as abortion and congenital disease in infants born to women who are acutely infected during pregnancy (29, 42). Waterborne transmission of T. gondii to immunocompetent adults has been reported, with resultant ocular and disseminated disease (12). Wildlife is also susceptible to waterborne toxoplasmosis, and in California, T. gondii is a significant cause of death in threatened Southern sea otters (Enhydra lutris nereis), where infection is hypothesized to occur through ingestion of oocysts that reach coastal waters in contaminated freshwater runoff (31, 39, 41). Along the California coast, 38% of live sea otters sampled between 1998 and 2004 had been exposed to T. gondii, and although water-related toxoplasmosis in humans has not been reported in this state, high rates of sea otter infection suggest that T. gondii contamination may pose a significant risk to animal and human health (11).

Domestic and wild felids are the only known definitive hosts of T. gondii, and one cat can shed millions of oocysts in its feces when infected (14). Toxoplasma gondii oocysts are highly resistant to the environment. Oocysts can remain viable in water sources for several years and are reportedly resistant to commonly employed water treatment processes, including chlorination, ozonation, and UV radiation (16, 32, 55, 56). Despite the significant health implications of waterborne toxoplasmosis in humans and animals, identifying high-risk sites of exposure and implementing prevention measures are difficult because the transport mechanisms and fate of T. gondii oocysts in the environment are largely unknown. Particularly puzzling is the observation that a large proportion of sea otters as well as other marine mammals are infected with this terrestrial pathogen (15, 40). The lack of knowledge on the behavior of oocysts in the environment is due to the lack of data regarding the surface chemistry of oocysts, as well as the absence of available tools for investigating the transport of T. gondii through environmental matrices.

Using oocysts in transport studies is not practical due to their biohazardous potential, the lack of available methods for quantitative detection in the environment, and the difficulty of producing oocysts, which requires experimental infection of mice and cats. The utilization of surrogate particles that mimic the behavior of oocysts in environmental waters could prove to be a powerful tool for evaluating the transmission of T. gondii from cat feces to susceptible hosts through aquatic habitats. Successful surrogates should be safe to release and easy to detect. Fluorescent polystyrene microspheres are nontoxic, inert particles that have been utilized as surrogates for other pathogens, including the protozoan parasite Cryptosporidium, viruses, and bacteria (18, 22, 26, 38). Using surrogates in the laboratory and field requires that particles must accurately predict the behavior of T. gondii by mimicking important physical and chemical properties. Certain physical properties of T. gondii oocysts, including size, shape, and specific gravity (sg), have been reported. Oocysts are roughly 10 to 12 μm in size and oval in shape, and their sg is between 1.05 and 1.10 (14, 17). However, surface properties such as electrophoretic mobility (an approximation of surface charge) and hydrophobicity, which strongly govern the behavior of particles in aquatic environments, have not been previously reported for T. gondii oocysts. In this study, we evaluated the electrophoretic mobilities of T. gondii oocysts in different water types that simulate aquatic environments in which oocysts are expected to become entrained during their transport from land to sea. Hydrophobicity was evaluated by measuring the surface wettability of T. gondii oocysts. Wettability experiments were performed using the water contact angle approach (53), a method that has not been previously described for protozoan parasites. To identify potential surrogate particles for T. gondii, fluorescent polystyrene microspheres with different modifications of their surface chemistries were evaluated, and their electrophoretic mobilities and hydrophobicity characteristics were compared with those of T. gondii oocysts. The objectives of this study were to further the current understanding of T. gondii oocyst surface properties that govern their transmission through water and to identify surrogate microspheres with surface chemistries similar to that of oocysts which could be employed in studies to evaluate the transport of T. gondii in aquatic habitats.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Toxoplasma gondii oocyst production.

All animal experiments were conducted with the approval and oversight of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of California, Davis, which is accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International. Female Swiss Webster mice (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) and 10-week-old specific-pathogen-free kittens (Nutrition and Pet Care Center, Department of Molecular Biosciences, University of California, Davis) were used for oocyst production. An indirect fluorescent-antibody test was used to prescreen sera from mice and kittens at a 1:40 dilution to ensure negative statuses prior to experimental infection with T. gondii. To produce oocysts, two kittens were fed 16 brains of mice previously inoculated with culture-derived tachyzoites of a characterized type II isolate of T. gondii obtained from a southern sea otter in California (40). Feces that were obtained from kittens were examined daily by zinc sulfate double centrifugation to detect shedding of oocysts. Once detected, unsporulated oocysts were harvested from fecal samples using sodium chloride (1.2 sg) as previously described (56). Sporulation was achieved by aeration in 2% sulfuric acid at 25°C over 7 to 10 days, after which a cesium chloride gradient was used to purify the oocysts as previously described (17) with the following modifications: 6 ml of oocyst suspension was layered onto 9 ml of CsCl solutions at 1.05, 1.10, and 1.15 sg and centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 60 min. Following centrifugation, oocysts were harvested and washed three times in deionized water, and the final suspension was strained through a 100-μm cell strainer (BD Falcon) to remove remaining debris. Purified oocysts were stored in 2% sulfuric acid at 4°C until use (within 6 months of production).

Surrogate microspheres.

Two different fluorescent, carboxylate-modified polystyrene microspheres were evaluated as potential T. gondii surrogate particles: Dragon Green (DG) microspheres (10.35-μm diameter, density of 1.06 sg, COOH at 1.0 μeq/g titration) and Glacial Blue (GB) microspheres (8.6-μm diameter, density of 1.06 sg, COOH at 800 μeq/g) were obtained from Bangs Laboratories, Inc., Fishers, IN (product numbers FC07F/5493 and PC06N/8319, respectively). DG microspheres were shipped in the presence of a surfactant (Tween 20), and GB microspheres were shipped in ultrapure water without a surfactant.

Electrophoretic mobility experiments. (i) Water solutions.

The electrophoretic mobilities of T. gondii oocysts and microspheres were evaluated in six water types. These included ultrapure (polished) water and five synthetic water solutions that represent aquatic environments that oocysts are likely to encounter during their transport from cat feces through overland flow into coastal waters. Artificial freshwater was prepared using an artificial pond water recipe found at the National Institute for Environmental Studies website to obtain a solution that was 0.5 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM NaHCO3, 0.05 mM KCl, and 0.4 mM CaCl2 (http://www.nies.go.jp/chiiki1/protoz/toxicity/medium.htm). All chemicals used were reagent grade (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) and dissolved in ultrapure water. Freshwater with dissolved organic carbon (DOC) was prepared by mixing Suwannee River natural organic matter (International Humic Substances Society, St. Paul, MN) with artificial freshwater to obtain solutions of freshwater plus 5 mg/liter DOC and of freshwater plus 15 mg/liter DOC. Artificial seawater was prepared by mixing Bio-Sea true seawater formula (Aqua Craft, Inc., Hayward, CA) with ultrapure water until an sg of 1.025 and 33 to 34 ppt were obtained. To simulate estuarine waters, solutions of freshwater plus 15 mg/liter DOC and seawater were combined at a 4:1 ratio which yielded a solution with an sg of 1.020 and 26 ppt. Water solutions were filtered through a 0.22-μm cellulose membrane (Millipore) and stored at 4°C until use. The conductivity of water solutions was measured after preparation, and the pH was measured for each particle and solution type at the onset of the mobility experiments (Accumet conductivity and pH meters; Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA).

(ii) Sample preparation.

Toxoplasma gondii oocysts stored in 2% sulfuric acid were washed twice with ultrapure water and twice with the water solution being tested in 15-ml, 100,000-molecular-weight Amicon Ultra tubes (Millipore Corporation). Amicon tubes were selected for the washing and concentrating of oocysts because large losses of oocysts were observed after oocysts were purified via the cesium chloride gradient and washed using standard centrifugation techniques. The Amicon tube technique reduced oocyst loss and allowed for an adequate concentration of oocysts. Following the four washes, oocysts were recovered by repeated rinsing and suctioning of the inner Amicon compartment and filter. The final volume was adjusted with the same water type until a dilution of 1 × 105 oocysts/ml was achieved. DG microspheres that were shipped in surfactant were tested as unwashed and washed preparations to evaluate the effect of surfactant removal on their surface properties. Unwashed microspheres were diluted directly into the water type being tested, and washed microspheres were processed using Amicon tubes, as used for T. gondii oocysts. GB microspheres were diluted directly from the stock suspension into each water type being tested to achieve a 1 × 105 particles/ml dilution.

(iii) Mobility measurement.

The electrophoretic mobilities of T. gondii oocysts and microspheres were determined using a ZetaPALS instrument (Brookhaven Instruments Corp., Holtsville, NY). Electrophoretic mobility units (MU) were automatically converted to zeta potentials by the instrument using the Smoluchowski equation (47). The electrophoretic mobilities of T. gondii oocysts and microspheres suspended in each water type were tested in triplicate. Four measurements were conducted on each replicate. For each particle and water type, a mean and standard error of the mean were calculated by averaging the mobilities of the three replicates.

Contact angle experiments. (i) Surface preparation.

The preparation of a uniform layer of particles (either T. gondii oocysts or microspheres) was modified from a technique for obtaining the contact angle of white blood cells proposed by Van Oss et al. (53). Briefly, T. gondii oocysts stored in sulfuric acid were washed four times with ultrapure water and concentrated to achieve a 1 × 106 oocysts/ml suspension. GB microspheres were diluted in ultrapure water to achieve a concentration of 1 × 106 particles/ml. DG microspheres were tested as unwashed and washed preparations (as described above) to evaluate their surface wettability without the presence of surfactant. Layers of particles were prepared on a 12-well, 5-mm slide (Erie Scientific, Portsmouth, NH) that was prewashed with hexanes and ethanol and O2 plasma etched at 180 W for 3 min to remove debris and facilitate particle spreading. To form a surface layer of either T. gondii oocysts or microspheres, slides were kept in a vacuum desiccator, and 10-μl drops of the test solution were applied repeatedly within wells until a uniform layer of particles was formed (between 250,000 and 500,000 particles). Three individual slide wells were coated with T. gondii oocysts, washed DG microspheres, or unwashed DG microspheres. Two slide wells were coated with GB microspheres. Measurements were conducted in triplicate on each slide well preparation. Initial measurements were performed over a range of drying times from 10 to 50 min using both vacuum and air drying conditions. To ensure drying conditions that were reproducible and not dependent on ambient humidity conditions, 15 min of vacuum desiccation was used for all particles for the remainder of the study.

(ii) Contact angle measurement.

Contact angle measurements were obtained using a VCA Optima XE system (AST Products, Billerica, MA). Each contact angle measurement was performed by dispensing a 2.5-μl droplet of ultrapure water on the particle layer and video recording the advancing droplet angle with a charge-coupled-device camera. The contact angle formed between the tangent of the semicircle droplet at the surface interface was calculated frame by frame for each video using the AST Optima analysis program. The plateau contact angle was obtained by averaging 8 to 12 individual angles during the plateau phase of the droplet as previously described (46).

RESULTS

Electrophoretic mobility.

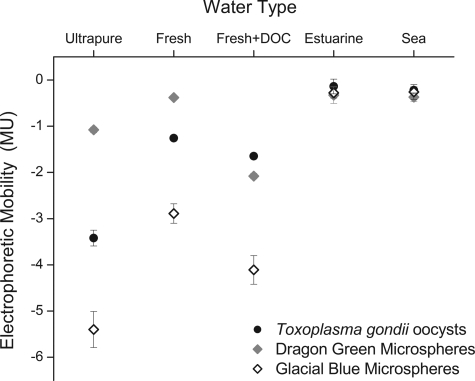

The conductivity and pHs of the solutions used in electrophoretic mobility determinations are displayed in Table 1. The electrophoretic mobilities and zeta potentials of T. gondii oocysts and surrogate microspheres suspended in different water types are summarized in Table 1. Oocysts were negatively charged in all freshwater solutions, with the highest (most negatively charged) MU (−3.42 MU) observed in ultrapure water. The charge of oocysts increased to near neutral in the higher-ionic-strength estuarine and seawater solutions (−0.14 MU and −0.22 MU, respectively). The negative charge of oocysts correlated with increasing concentrations of DOC in freshwater, with mean MU of −1.26, −1.48, and −1.65 when suspended in solutions of freshwater, of freshwater plus 5 mg/liter DOC, and of freshwater plus 15 mg/liter DOC, respectively. The electrophoretic mobilities of microspheres showed a similar pattern, with increasing mobilities in the presence of DOC and decreasing mobilities in saline waters (Fig. 1). Compared with the mobilities of T. gondii oocysts, DG microspheres had lower mobilities in ultrapure and freshwater solutions but were similar in charge when suspended in freshwater plus 15 mg/liter DOC, estuarine, and seawater solutions. Washing DG microspheres did not appreciably alter their electrophoretic mobilities. The GB microspheres had higher mobilities than those of oocysts in all freshwater solutions, but like oocysts and DG microspheres, their charge was reduced in estuarine and seawater solutions.

TABLE 1.

Electrophoretic mobilities and zeta potentials of Toxoplasma gondii oocysts and DG and GB surrogate microspheres in different water types

| Water type | Conductivity (μS/cm)a | Particle typeb | pHc | Electrophoretic mobility (μm/s/V/cm)d | Zeta potential (mV)e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrapure | 4 | T. gondii | 6.7 | −3.42 (0.17) | −43.74 (2.22) |

| DG | 5.5 | −1.08 (0.06) | −13.85 (0.70) | ||

| Washed DG | 5.5 | −1.24 (0.08) | −15.81 (0.92) | ||

| GB | 6.0 | −5.40 (0.39) | −69.09 (4.95) | ||

| Freshwater | 130 | T. gondii | 7.0 | −1.26 (0.01) | −16.16 (0.06) |

| DG | 7.0 | −0.38 (0.00) | −4.90 (0.03) | ||

| Washed DG | 7.0 | −0.74 (0.01) | −9.48 (0.11) | ||

| GB | 7.1 | −2.89 (0.21) | −36.97 (2.63) | ||

| Freshwater + 5 mg/liter DOC | 154 | T. gondii | 6.7 | −1.48 (0.02) | −19.02 (0.26) |

| Freshwater + 15 mg/liter DOC | 162 | T. gondii | 6.4 | −1.65 (0.05) | −21.09 (0.67) |

| DG | 6.7 | −2.08 (0.06) | −26.63 (0.81) | ||

| Washed DG | 6.7 | −1.67 (0.10) | −21.35 (1.27) | ||

| GB | 6.8 | −4.11 (0.31) | −52.62 (3.92) | ||

| Estuarine | 34,980 | T. gondii | 7.5 | −0.14 (0.16) | −1.84 (2.03) |

| DG | 7.7 | −0.33 (0.18) | −4.18 (2.29) | ||

| Washed DG | 7.7 | NAf | NA | ||

| GB | 7.6 | −0.28 (0.11) | −3.65 (1.41) | ||

| Seawater | 47,790 | T. gondii | 7.9 | −0.22 (0.07) | −2.81 (0.83) |

| DG | 8.0 | −0.37 (0.10) | −4.70 (1.24) | ||

| Washed DG | 8.0 | −0.21 (0.43) | −2.66 (5.52) | ||

| GB | 7.8 | −0.26 (0.16) | −3.36 (1.96) |

Conductivity of water solutions was measured after suspensions were prepared according to recipes provided in Materials and Methods.

T. gondii, T. gondii oocysts; DG, Dragon Green surrogate microspheres; GB, Glacial Blue surrogate microspheres.

The pH for each particle and water type was measured at the onset of the mobility experiments.

Values represent the means of three replicates (standard error of the mean).

Zeta potential was automatically converted from electrophoretic mobilities by the ZetaPALS instrument using the Smoluchowski equation (ζ = 4пημ/Ε, where ζ is zeta potential, η is viscosity of solution, μ is electrophoretic mobility, and Ε is dielectric constant of solution). Values represent the means of three replicates (standard error of the mean).

NA, not assessed.

FIG. 1.

Electrophoretic mobilities of Toxoplasma gondii oocysts and surrogate microspheres in different water types. Error bars represent the standard errors of the means of three replicates. The DOC was 15 mg/liter, and MU are expressed in μm/s/V/cm.

Contact angle.

The means of the advancing contact angles measured and analyzed during the plateau phase after dispensing a water droplet on a surface of T. gondii oocysts and microspheres are presented in Table 2. The water contact angle on a surface of T. gondii oocysts was markedly hydrophilic at 13.4 degrees. Unwashed DG microspheres and GB microspheres also displayed low hydrophilic angles. However, washing DG microspheres that were shipped in the presence of a surfactant produced a significant increase in contact angle, from a hydrophilic angle of 11.6 degrees prior to washing to 130.9 degrees after washing.

TABLE 2.

Advancing plateau contact angles of water on the surfaces of Toxoplasma gondii oocysts and carboxylated polystyrene microspheres

| Particle type | Mean angle (°) (SE) | Angle range (°) |

|---|---|---|

| Toxoplasma gondii oocysts | 13.4 (3.42) | 7.3-19.1 |

| Surrogate microspheres | ||

| DGa | 11.6 (3.98) | 7.2-19.5 |

| Washed DG | 130.9 (2.96) | 125.5-135.6 |

| GBb | 7.3 (0.18) | 7.1-7.5 |

Dragon Green microspheres shipped in the presence of a surfactant were tested as unwashed and washed.

Glacial Blue microspheres.

DISCUSSION

The surface properties of Toxoplasma gondii oocysts, including electrophoretic mobilities and hydrophobicity, partially govern the transmission of this zoonotic pathogen through water. The carboxylated polystyrene microspheres that were evaluated in this study possess surface properties that resemble those of T. gondii oocysts, suggesting that these particles may be utilized as surrogate particles for this parasite. Results from this study provide novel insight into the physical mechanisms that affect the epidemiology of waterborne toxoplasmosis and provide a new tool for investigating the environmental transport of T. gondii oocysts and assessing the efficiency of water treatment methods for the removal of the parasite from water.

Contact angle and electrophoretic mobility data demonstrate that T. gondii oocysts are hydrophilic and negatively charged in freshwater types. The reduced electrophoretic mobilities seen in higher-ionic-strength estuarine and seawater solutions reflect a loss of surface charge that may strongly influence the transport behavior of oocysts from overland freshwater runoff to coastal waters. The transport and fate of contaminants, including pathogens, largely depend on whether they readily form aggregates with other suspended matter. When aggregated, particles are more likely to settle and accumulate in sediments than particles that are suspended freely in the water column and can be advected along with water currents over long distances. The forces that govern particle-particle interactions in aquatic media are largely determined by the surface properties of the particles, including repulsive electrostatic forces and van der Waals and acid-base interactions, which can be attractive or repulsive. Together, these forces have been described as the extended DLVO (Derjaguin, Landau, Verwey, and Overbeek) theory (54). As surface charge approaches zero, the potential of particles to repel each other and other similarly charged particles diminishes, resulting in a higher probability of particle flocculation (25).

The decreases in the electrophoretic mobilities (diminished negative charge) of T. gondii oocysts in saline waters suggest that flocculation of oocysts from overland runoff may occur at freshwater and seawater mixing zones, leading to aggregates of debris containing oocysts within estuaries and near-coast habitats. In fact, flocculation of other organic matter and heavy metals has been documented to occur in estuaries (19, 30, 48, 49). While flocculation and the subsequent concentration of pathogens have not been previously described in natural estuarine habitats, diminished mobilities with increasing ionic strength in bacteria, yeast, and other protozoan parasites have been documented under experimental conditions (5, 28, 45). The potential flocculation of T. gondii oocysts and other land-derived pathogens in estuarine habitats would significantly affect their spatial distribution in coastal environments. Terrestrial pathogens are likely to reach estuarine waters following heavy surface runoff events that are driven by rainfall. Once deposited in higher-salinity waters, flocculation of pathogens would lead to aggregation with other suspended particles, resulting in increased deposition and accumulation in sediments at freshwater and marine water mixing zones. If the increased salinity of water favored flocculation of T. gondii oocysts, then locations where contaminated freshwater runoff mixes with marine waters may pose distinct high-risk sites of exposure to wildlife species, such as sea otters that live exclusively in near-shore habitats and feed on benthic invertebrates that have been shown to concentrate T. gondii oocysts in their tissues (1, 36). Toxoplasma gondii oocysts remain viable for at least 6 months in seawater, so persistence of infective oocysts as they accumulate in marine sediments is possible (35). Although the actual flocculation of T. gondii and other land-derived pathogens within estuarine waters needs to be verified experimentally, such sites may also be important from a public health perspective. Concentration of pathogens at the freshwater and marine water mixing zones may pose a significantly higher risk of infection to humans through recreational uses or ingestion of shellfish that are farmed and harvested at these locations. Once flocculated, pathogens within marine aggregates can be ingested by filter-feeding bivalves (37) which are then able to concentrate and transmit zoonotic microorganisms to people (10, 23, 24, 41, 57).

To date, the method most commonly employed to assess the hydrophobicity of protozoans is the microbial adhesion to hydrocarbon approach (44). This method measures hydrophobicity indirectly and suffers from serious drawbacks (9, 20, 51). In addition, several studies that utilized the microbial adhesion to hydrocarbon approach report contradictory results when the approach was applied to Cryptosporidium oocysts (13, 28). Thus, the contact angle approach utilized in the present study provides a novel tool for a quantitative and direct approximation of hydrophobicity and surface energy studies on protozoan parasites. Surface energy is a more accurate term for interactions commonly simplified by the term “hydrophobicity” and is composed of Lifshitz-van der Waals interactions and acid-base interactions which include proton-donating and proton-accepting chemical groups (52). The contact angle method can be used to quantify each component that contributes to surface energy by probing surfaces with three different liquids, typically one apolar and two polar solutions (6). While a thorough evaluation of surface energy can have useful applications for predicting adsorption of particles, the objective of our study was to provide an approximation of T. gondii hydrophobicity that could be used for choosing an appropriate surrogate particle. The use of the contact angle method with water as a probing liquid revealed that T. gondii oocysts were markedly hydrophilic, with a low average contact angle of 13.4 degrees. An important consideration when evaluating the surface properties of pathogens is that chemicals used to extract and store pathogens can influence the results of electrophoretic mobility and hydrophobicity experiments (8). For this reason, careful attention was given to oocyst purification methods, and preservatives or antibiotics were purposefully not used in oocyst storage media. In addition, the surface properties discussed here were evaluated using oocysts from a type II strain of T. gondii; further investigations will be necessary to assess if isolate or genotype variation affects the wall composition and surface properties of oocysts.

Results of the electrophoretic mobility and contact angle experiments performed on carboxylated DG and GB microspheres suggest that the joint application of these surrogate particles may provide insight on the range of transport potentials expected from T. gondii oocysts in water. When utilizing surrogate particles for estimating pathogen behavior, one should note that certain surface properties not commonly measured can also affect particle transport, as was demonstrated with the effect of steric hindrance on the stability of Cryptosporidium sp. oocysts in water (33). In this study, focus was given to surface charge and hydrophobicity, two properties that are known to significantly affect particle interactions in aquatic habitats (25). Like T. gondii, the electrophoretic mobilities of microspheres increased in water containing DOC and decreased in estuarine and seawater solutions. Neither surrogate type had a surface charge that was identical to that of T. gondii oocysts in the freshwater solutions; however, in estuarine water and seawater, the mobilities of oocysts, DG microspheres, and GB microspheres were near neutral. As expected from the increased carboxylation of the styrene residues on GB microspheres, in purified water and freshwater solutions, GB microspheres had higher mobilities and DG microspheres had lower mobilities than those of T. gondii oocysts. The increased mobilities seen in the presence of DOC have been previously described in the literature for other particles and are attributed to adsorption of humic and fluvic acids onto the surfaces of the particles (3, 21).

A comparison between the contact angle results of T. gondii oocysts and surrogate microspheres showed that GB and unwashed DG microspheres have low contact angles, corresponding with hydrophilic properties similar to those of oocysts. However, after DG microspheres were washed, their contact angle increased significantly, reflecting a hydrophobic surface. The change in surface hydrophobicity is likely due to the removal of Tween that was present in the microsphere suspension as shipped from the manufacturer. As a nonionic surfactant, Tween was expected to influence surface hydrophobicity, as shown in other studies (34). However, washing DG microspheres did not seem to appreciably alter electrophoretic mobility results, which is likely due to the nonionized nature of the hydrophilic portion of the Tween molecule. The results reported here highlight the importance of considering the effect of shipping solution on microsphere surface properties when selecting these particles as surrogates for pathogen transport and fate studies. Once DG microspheres are placed in water in laboratory experiments or after release in the environment, Tween molecules will become diluted and may diffuse away from the surfaces of microspheres, rendering these particles hydrophobic and no longer similar to hydrophilic T. gondii oocysts. Finally, for both microsphere and oocyst contact angle experiments, it is important to consider that an uneven surface formed by creating a layer composed of discrete particles may influence angle measurements (50). A recently described film-caliper contact angle method applied on microspheres suggests that future application of this method on microbial organisms may soon provide a quantitative measurement of surface wettability that avoids the potential impact of surface roughness (27).

The carboxylated microspheres tested in this study did not have surface properties identical to those of T. gondii oocysts, yet the pattern of similarities shared with oocysts suggests that both DG and GB microspheres can serve as potential surrogates. Overall, DG microspheres are similar in size, sg, and electrophoretic mobilities to T. gondii oocysts. However, unlike T. gondii, in the absence of a surfactant, DG microspheres become hydrophobic and may adsorb more readily to organic debris and vegetation. GB microspheres are hydrophilic and do not require a surfactant to remain stable in suspension. These particles are expected to remain freely suspended in the water column longer than oocysts due to their stronger electrostatic repulsive properties (higher mobilities) and their expected lower settling velocities as a result of their smaller size as predicted by Stokes' law (25). Thus, based on the surface properties tested and theoretical considerations of particle transport in aqueous media, DG microspheres are expected to have a shorter transport potential, while GB microspheres are expected to have a longer transport potential than T. gondii oocysts under identical environmental conditions. If applied simultaneously, these surrogates may bracket the behavior of T. gondii oocysts, thus providing a maximum and minimum expected recovery of oocysts in transport and fate studies. In current settling and transport behavior studies, DG and GB microspheres will be evaluated further for their application as surrogates for T. gondii oocysts. The cost of the surrogate microspheres is approximately $2 per one million microspheres. In comparison, based on several T. gondii oocyst production experiments in our laboratory, we estimate a cost of $150 per one million oocysts; this cost includes animal handling, oocyst isolation, and purification expenses. Microspheres bearing surface chemistry similar to that of T. gondii, therefore, provide a cost-efficient, safe, and quantitative means of estimating the transport potential of oocysts.

The hydrophilic nature and negative charge of T. gondii oocysts in freshwater enable this zoonotic pathogen to become easily entrained in waterways and bypass commonly used treatment processes. Thus, oocysts that survive and remain viable in the environment serve as a source of infection to people and animals. The observed loss of surface charge in estuarine habitats could lead to oocyst aggregation and subsequent accumulation of this parasite in areas where freshwater and marine waters mix, leading to distinct high-risk zones of infection to susceptible hosts through accidental ingestion of contaminated water or accumulation in food sources such as shellfish. Although the surface properties of the microspheres we evaluated were not identical to those of T. gondii, using both DG and GB microspheres together will provide a range of transport potentials in which oocysts are likely to behave. Future applications of surrogates will provide safe methods and novel insight on the transport and fate of T. gondii oocysts in aquatic systems, as well as a new tool for evaluating water treatment processes for removing this zoonotic pathogen from drinking water.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation, Ecology of Infectious Disease grant 0525765.

We thank Andrea Packham for assistance with oocyst production and Robert Zasoski and David Fairhurst for the insight and guidance they provided with the electrophoretic mobility studies.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 5 December 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arkush, K. D., M. A. Miller, C. M. Leutenegger, I. A. Gardner, A. E. Packham, A. R. Heckeroth, A. M. Tenter, B. C. Barr, and P. A. Conrad. 2003. Molecular and bioassay-based detection of Toxoplasma gondii oocyst uptake by mussels (Mytilus galloprovincialis). Int. J. Parasitol. 33:1087-1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bahia-Oliveira, L. M., J. L. Jones, J. Azevedo-Silva, C. C. Alves, F. Orefice, and D. G. Addiss. 2003. Highly endemic, waterborne toxoplasmosis in north Rio de Janeiro state, Brazil. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9:55-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beckett, R., and N. P. Le. 1990. The role of organic matter and ionic composition in determining the surface charge of suspended particles in natural waters. Colloids Surf. 44:35-49. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benenson, M. W., E. T. Takafuji, S. M. Lemon, R. L. Greenup, and A. J. Sulzer. 1982. Oocyst-transmitted toxoplasmosis associated with ingestion of contaminated water. N. Engl. J. Med. 307:666-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolster, C. H., S. L. Walker, and K. L. Cook. 2006. Comparison of Escherichia coli and Campylobacter jejuni transport in saturated porous media. J. Environ. Qual. 35:1018-1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bos, R., H. C. van der Mei, and H. J. Busscher. 1999. Physico-chemistry of initial microbial adhesive interactions—its mechanisms and methods for study. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 23:179-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bowie, W. R., A. S. King, D. H. Werker, J. L. Isaac-Renton, A. Bell, S. B. Eng, S. A. Marion, et al. 1997. Outbreak of toxoplasmosis associated with municipal drinking water. Lancet 350:173-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brush, C. F., M. F. Walter, L. J. Anguish, and W. C. Ghiorse. 1998. Influence of pretreatment and experimental conditions on electrophoretic mobility and hydrophobicity of Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:4439-4445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Busscher, H. J., B. van de Belt-Gritter, and H. C. van der Mei. 1995. Implications of microbial adhesion to hydrocarbons for evaluating cell surface hydrophobicity 1. Zeta potentials of hydrocarbon droplets. Colloids Surf. B 5:111-116. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cabelli, V. J., and W. P. Heffernan. 1970. Accumulation of Escherichia coli by Northern quahaug. Appl. Microbiol. 19:239-244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conrad, P. A., M. A. Miller, C. Kreuder, E. R. James, J. Mazet, H. Dabritz, D. A. Jessup, F. Gulland, and M. E. Grigg. 2005. Transmission of Toxoplasma: clues from the study of sea otters as sentinels of Toxoplasma gondii flow into the marine environment. Int. J. Parasitol. 35:1155-1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dardé, M. L., I. Villena, J. M. Pinon, and I. Beguinot. 1998. Severe toxoplasmosis caused by a Toxoplasma gondii strain with a new isoenzyme type acquired in French Guyana. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drozd, C., and J. Schwartzbrod. 1996. Hydrophobic and electrostatic cell surface properties of Cryptosporidium parvum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:1227-1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dubey, J. P., N. L. Miller, and J. K. Frenkel. 1970. The Toxoplasma gondii oocyst from cat feces. J. Exp. Med. 132:636-662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dubey, J. P., R. Zarnke, N. J. Thomas, S. K. Wong, W. Van Bonn, M. Briggs, J. W. Davis, R. Ewing, M. Mense, O. C. Kwok, S. Romand, and P. Thulliez. 2003. Toxoplasma gondii, Neospora caninum, Sarcocystis neurona, and Sarcocystis canis-like infections in marine mammals. Vet. Parasitol. 116:275-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dumetre, A., and M. L. Darde. 2003. How to detect Toxoplasma gondii oocysts in environmental samples? FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 27:651-661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dumetre, A., and M. L. Darde. 2004. Purification of Toxoplasma gondii oocysts by cesium chloride gradient. J. Microbiol. Methods 56:427-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Emelko, M. B., and P. M. Huck. 2004. Microspheres as surrogates for Cryptosporidium filtration. J. Am. Water Works Assoc. 96:94-105. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gebhardt, A. C., F. Schoster, B. Gaye-Haake, B. Beeskow, V. Rachold, D. Unger, and V. Ittekkot. 2005. The turbidity maximum zone of the Yenisei River (Siberia) and its impact on organic and inorganic proxies. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 65:61-73. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geertsema-Doornbusch, G. I., H. C. van der Mei, and H. J. Busscher. 1993. Microbial cell surface hydrophobicity. The involvement of electrostatic interactions in microbial adhesion to hydrocarbon (MATH). J. Microbiol. Methods 18:61-68. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gerritsen, J., and S. W. Bradley. 1987. Electrophoretic mobility of natural particles and cultured organisms in fresh waters. Limnol. Oceanogr. 32:1049-1058. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gonzalez, J. M., and C. A. Suttle. 1993. Grazing by marine nanoflagellates on viruses and virus-sized particles: ingestion and digestion. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 94:1-10. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graczyk, T. K., R. Fayer, E. J. Lewis, J. M. Trout, and C. A. Farley. 1999. Cryptosporidium oocysts in Bent mussels (Ischadium recurvum) in the Chesapeake Bay. Parasitol. Res. 85:518-521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Graczyk, T. K., D. J. Marcogliese, Y. de Lafontaine, A. J. Da Silva, B. Mhangami-Ruwende, and N. J. Pieniazek. 2001. Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts in zebra mussels (Dreissena polymorpha): evidence from the St. Lawrence River. Parasitol. Res. 87:231-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gregory, J. 2005. Particles in water: properties and processes. Taylor & Francis Group, Boca Raton, FL.

- 26.Harvey, R. W., N. E. Kinner, D. Macdonald, D. W. Metge, and A. Bunn. 1993. Role of physical heterogeneity in the interpretation of small-scale laboratory and field observations of bacteria, microbial-sized microsphere, and bromide transport through aquifer sediments. Water Resour. Res. 29:2713-2721. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horozov, T. S., D. A. Braz, P. D. I. Fletcher, B. P. Binks, and J. H. Clint. 2008. Novel film-calliper method of measuring the contact angle of colloidal particles at liquid interfaces. Langmuir 24:1678-1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hsu, B. M., and C. Huangc. 2002. Influence of ionic strength and pH on hydrophobicity and zeta potential of Giardia and Cryptosporidium. Colloids Surf. A 201:201-206. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones, J. L., A. Lopez, M. Wilson, J. Schulkin, and R. Gibbs. 2001. Congenital toxoplasmosis: a review. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 56:296-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karbassi, A. R., and S. Nadjafpour. 1996. Flocculation of dissolved Pb, Cu, Zn and Mn during estuarine mixing of river water with the Caspian Sea. Environ. Pollut. 93:257-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kreuder, C., M. A. Miller, D. A. Jessup, L. J. Lowenstine, M. D. Harris, J. A. Ames, T. E. Carpenter, P. A. Conrad, and J. A. Mazet. 2003. Patterns of mortality in southern sea otters (Enhydra lutris nereis) from 1998-2001. J. Wildl. Dis. 39:495-509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuticic, V., and T. Wikerhauser. 1996. Studies of the effect of various treatments on the viability of Toxoplasma gondii tissue cysts and oocysts. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 219:261-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuznar, Z. A., and M. Elimelech. 2006. Cryptosporidium oocyst surface macromolecules significantly hinder oocyst attachment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 40:1837-1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li, W., and T. Gu. 1985. Equilibrium contact angles as a function of the concentration of nonionic surfactants on quartz plate. Colloid Polym. Sci. 263:1041-1043. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindsay, D. S., M. V. Collins, S. M. Mitchell, R. A. Cole, G. J. Flick, C. N. Wetch, A. Lindquist, and J. P. Dubey. 2003. Sporulation and survival of Toxoplasma gondii oocysts in seawater. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 50(Suppl.):687-688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lindsay, D. S., K. K. Phelps, S. A. Smith, G. Flick, S. S. Sumner, and J. P. Dubey. 2001. Removal of Toxoplasma gondii oocysts from sea water by eastern oysters (Crassostrea virginica). J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2001(Suppl.):197S-198S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lyons, M. M., J. E. Ward, R. Smolowitz, K. R. Uhlinger, and R. J. Gast. 2005. Lethal marine snow: pathogen of bivalve mollusc concealed in marine aggregates. Limnol. Oceanogr. 50:1983-1988. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Metge, D. W., R. W. Harvey, R. Anders, D. O. Rosenberry, D. Seymour, and J. Jasperse. 2007. Use of carboxylated microspheres to assess transport potential of Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts at the Russian River water supply facility, Sonoma County, California. Geomicrobiol. J. 24:231-245. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller, M. A., I. A. Gardner, C. Kreuder, D. M. Paradies, K. R. Worcester, D. A. Jessup, E. Dodd, M. D. Harris, J. A. Ames, A. E. Packham, and P. A. Conrad. 2002. Coastal freshwater runoff is a risk factor for Toxoplasma gondii infection of southern sea otters (Enhydra lutris nereis). Int. J. Parasitol. 32:997-1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller, M. A., M. E. Grigg, C. Kreuder, E. R. James, A. C. Melli, P. R. Crosbie, D. A. Jessup, J. C. Boothroyd, D. Brownstein, and P. A. Conrad. 2004. An unusual genotype of Toxoplasma gondii is common in California sea otters (Enhydra lutris nereis) and is a cause of mortality. Int. J. Parasitol. 34:275-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller, M. A., W. A. Miller, P. A. Conrad, E. R. James, A. C. Melli, C. M. Leutenegger, H. A. Dabritz, A. E. Packham, D. Paradies, M. Harris, J. Ames, D. A. Jessup, K. Worcester, and M. E. Grigg. 2008. Type X Toxoplasma gondii in a wild mussel and terrestrial carnivores from coastal California: new linkages between terrestrial mammals, runoff and toxoplasmosis of sea otters. Int. J. Parasitol. 38:1319-1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murray, P. R., E. J. Baron, J. H. Jorgensen, M. A. Pfaller, and R. H. Yolken (ed.). 2003. Manual of clinical microbiology, 8th ed., vol. 2. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 43.Palanisamy, M., B. Madhavan, M. B. Balasundaram, R. Andavar, and N. Venkatapathy. 2006. Outbreak of ocular toxoplasmosis in Coimbatore, India. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 54:129-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosenberg, M. 2006. Microbial adhesion to hydrocarbons: twenty-five years of doing MATH. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 262:129-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Salt, D. E., A. C. Bentham, S. Hay, A. Idris, J. Gregory, M. Hoare, and P. Dunnill. 1996. The mechanism of flocculation of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell homogenate using polyethyleneimine. Bioprocess Eng. 15:71-76. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sharma, P. K., and K. H. Rao. 2002. Analysis of different approaches for evaluation of surface energy of microbial cells by contact angle goniometry. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 98:341-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shaw, D. J. 1969. Electrophoresis, 1st ed. Academic Press, Inc., New York, NY.

- 48.Sholkovitz, E. R. 1978. Flocculation of dissolved Fe, Mn, Al, Cu, Ni, Co and Cd during estuarine mixing. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 41:77-86. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sholkovitz, E. R. 1976. Flocculation of dissolved organic and inorganic matter during mixing of river water and seawater. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 40:831-845. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spori, D. M., T. Drobek, S. Zurcher, M. Ochsner, C. Sprecher, A. Muehlebach, and N. D. Spencer. 2008. Beyond the lotus effect: roughness, influences on wetting over a wide surface-energy range. Langmuir 24:5411-5417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van der Mei, H. C., B. van de Belt-Gritter, and H. J. Busscher. 1995. Implications of microbial adhesion to hydrocarbons for evaluating cell surface hydrophobicity. 2. Adhesion mechanisms. Colloids Surf. B 5:117-126. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Van Oss, C. J. 1993. Acid-base interfacial interactions in aqueous media. Colloids Surf. A 78:1-49. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Van Oss, C. J., C. F. Gillman, and A. W. Neumann (ed.). 1975. Phagocytic engulfment and cell adhesiveness as cellular surface phenomena, 1st ed., vol. 2. Marcel Dekker, Inc., New Hyde Park, NY.

- 54.Van Oss, C. J., R. J. Good, and M. K. Chaudhuryc. 1986. The role of van der Waals forces and hydrogen bonds in “hydrophobic interactions” between biopolymers and low energy surfaces. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 111:378-390. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wainwright, K. E., M. Lagunas-Solar, M. A. Miller, B. C. Barr, I. A. Gardner, C. Pina, A. C. Melli, A. E. Packham, N. Zeng, T. Truong, and P. A. Conrad. 2007. Physical inactivation of Toxoplasma gondii oocysts in water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:5663-5666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wainwright, K. E., M. A. Miller, B. C. Barr, I. A. Gardner, A. C. Melli, T. Essert, A. E. Packham, T. Truong, M. Lagunas-Solar, and P. A. Conrad. 2007. Chemical inactivation of Toxoplasma gondii oocysts in water. J. Parasitol. 93:925-931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wilson, I. G., and J. E. Moore. 1996. Presence of Salmonella spp. and Campylobacter spp. in shellfish. Epidemiol. Infect. 116:147-153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]