Abstract

Liver-stage antigen 3 (LSA-3) is a new vaccine candidate that can induce protection against Plasmodium falciparum sporozoite challenge. Using a series of long synthetic peptides (LSP) encompassing most of the 210-kDa LSA-3 protein, a study of the antigenicity of this protein was carried out in 203 inhabitants from the villages of Dielmo (n = 143) and Ndiop (n = 60) in Senegal (the level of malaria transmission differs in these two villages). Lymphocyte responses to each individual LSA-3 peptide were recorded, some at high prevalences (up to 43%). Antibodies were also detected to each of the 20 peptides, many at high prevalence (up to 84% of responders), and were directed to both nonrepeat and repeat regions. Immune responses to LSA-3 were detectable even in individuals of less than 5 years of age and increased with age and hence exposure to malaria, although they were not directly related to the level of malaria transmission. Thus, several valuable T- and B-cell epitopes were characterized all along the LSA-3 protein, supporting the antigenicity of this P. falciparum vaccine candidate. Finally, antibodies specific for peptide LSP10 located in a nonrepeat region of LSA-3 were found significantly associated with a lower risk of malaria attack over 1 year of daily clinical follow-up in children between the ages of 7 and 15 years, but not in older individuals.

Preerythrocytic malaria antigens are critical targets of protective immune responses induced by irradiated sporozoites in humans (9, 22). The demonstration of T-cell-mediated protection in mice immunized by this means (10, 16), the acquisition of a significant level of protection against homologous Plasmodium falciparum challenge in human volunteers (22), and the induction by liver-stage antigens of a high level of protection against P. falciparum infection in chimpanzees (19, 31) all point to a major role for preerythrocytic stage antigens as vaccine candidates.

Liver-stage antigen 3 (LSA-3) is a novel antigen expressed at the preerythrocytic stages (4). LSA-3 was selected by the differential immune response found between protected and nonprotected volunteers, both similarly immunized with irradiated sporozoites (4, 9). The gene encoding LSA-3 is unusually well-conserved (4), in contrast with many other malaria vaccine candidates (11, 19, 23). More than 10 dominant T-helper (Th), cytotoxic T-lymphocyte, and B-cell epitopes have already been characterized in LSA-3 (20), some of them displaying cross-reactivity with an homologous antigen in Plasmodium yoelii (2). The protective potential of LSA-3 was demonstrated by a series of experiments in chimpanzees and Aotus monkeys challenged with P. falciparum (4, 21) and in mice challenged by P. yoelii following immunization either by recombinant proteins with adjuvant or by formulations without adjuvant, such as recombinant proteins adsorbed on microparticles or lipopeptides in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (4), or DNA-based immunization (29). These convergent results stress the potential of LSA-3 as a prime vaccine candidate.

We therefore decided to further analyze the antigenicity of LSA-3 and to investigate immune responses to discrete regions of the protein in exposed individuals living in areas where malaria is endemic.

T- and B-cell responses were evaluated in subjects living in two villages in Senegal, West Africa, where malaria is endemic, using three small synthetic peptides and a series of 17 overlapping long synthetic peptides (LSP) encompassing most of the LSA-3 protein. In keeping with preliminary results (20), we found a high prevalence of responses to most regions of this preerythrocytic stage antigen in individuals of different age groups. These results bring additional arguments in favor of the potential of the LSA-3 protein for vaccine development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Population studied.

A total of 294 inhabitants from Dielmo and Ndiop, two villages located in a rural area of Senegal (West Africa), 270 km southwest of Dakar were studied. In Dielmo, a group of 143 villagers and then a second group of 91 villagers 3 to 87 years of age were enrolled in this study; in Ndiop, a group of 60 villagers 4 to 71 years of age was enrolled in this study. The villagers were selected so as to be representative of all age groups and were clinically asymptomatic at the time of the study. The main epidemiological features of these two villages have been reported previously (26, 27, 32). Entomological and parasitological surveys showed that Dielmo, with approximately 200 to 300 infected mosquito bites per person per year, is an area where malaria is holoendemic and characterized by high and perennial parasite transmission (13), whereas Ndiop is a mesoendemic area where malarial transmission is seasonal, approximately 10 times lower, with ca. 20 to 30 infected bites per person per year (14). Clinical data were recorded on a daily basis year-round, and malaria attacks were defined as a fever of >38.5°C associated with a parasite density over an age-dependent threshold defined for each age group (32). In the present study, malaria attacks recorded for months following blood sampling were used for the statistical analysis.

After informed consent from each individual or their legal representative was obtained, venous blood samples were collected during winter, i.e., during the lowest transmission season in both villages, using 10-ml Vacutainers in which 250 IU of preservative-free heparin (Liquemine; Roche) had been added. Blood samples were transferred to our laboratory in Dakar, Senegal, within 4 to 5 h at a temperature of 20°C to 25°C.

This study was examined and approved by the National Senegalese Ethical Committee.

Peptides.

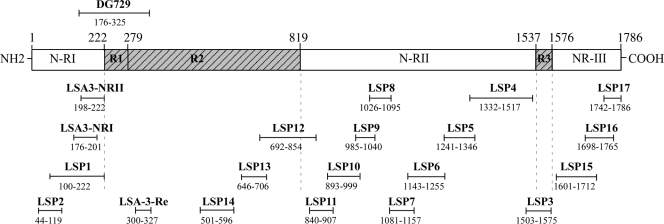

Seventeen overlapping long synthetic peptides (LSP1 to LSP17) 45 to 186 amino acids in length, spanning most of the P. falciparum LSA-3 protein (Fig. 1) were synthesized by solid-phase 9-fluorenylmethoxy carbonyl (Fmoc) chemistry as described previously (18, 24, 25). The purity of the LSP was determined by high-performance liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry and ranged from 70% to 80%. Impurities consisted mostly of either smaller fragments or full-length peptides differing by one or two t-butyl groups [-C-(CH3)3]. No indication of bacterial endotoxin contamination was found in the peptide preparations following the use of Limulus amebocyte lysate (Pyrogent Plus; Cambrex Bio Science). Two peptides, LSP with amino acids 44 to 119 (LSP 44-119) (LSP2) and LSP 100-222 (LSP1), represent most of the nonrepeat region I (NR-I) from the N-terminal part of the protein. Three peptides, namely, LSP 501-596 (LSP14), LSP 646-706 (LSP13), and LSP 692-854 (LSP12), contain sequences representative of the repeat region R2. Eight out of the 12 remaining peptides spanning amino acids 840 to 1517 correspond to sequences from nonrepeat region II (NR-II). One LSP, LSP3 (LSP 1503-1575) covers the repeat block R3, and the last three peptides spanning residues1601 to 1786 represent the nonrepeat C-terminal region (NR-III). Each peptide overlapped the following or previous one by 15 amino acids, except the sequences 1503-1575 and 1601-1712 for which 26 amino acids were missing in the repeat region R3 (Fig. 1). In addition, three smaller peptides derived from the recombinant protein DG729 (positions 176 to 325) used previously in immunization experiments and inducing protection (1, 4, 21), covering part of the NR-I region of the protein (LSA-3-NRI 176-201 and NR-II 198-222) and part of the R2 region (LSA-3-Re 300-327) (4), were tested in parallel.

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the Plasmodium falciparum LSA-3 protein showing the localization of the peptides employed, the 17 long synthetic peptides (LSP1 to LSP17) and the 3 smaller peptides (LSA-3-NRI, LSA-3-NRII, and LSA-3-RE) encompassing most of the LSA-3 protein. The localization of DG729 is indicated. The numbers are amino acid positions.

ELISAs.

Preliminary assays showed that 5 μg/ml and 1 μg/ml concentrations of the LSA-3 short and long synthetic peptides, respectively, gave optimal enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) results. The peptides, diluted in PBS were added to each well of 96-well flat-bottomed polystyrene microtiter plates (Immulon) and incubated at 4°C overnight. After the wells were washed five times with PBS containing 1% Tween, 200 μl of PBS with 1% bovine serum albumin blocking buffer was added to each well, and the plates were incubated for 1 h at 37°C.

Each plasma sample was tested in duplicate in peptide-coated wells for total immunoglobulin G (IgG) and each IgG subclass (IgG1 to IgG4). The plasma samples, diluted 1/100, were added to the wells (100 μl/well), and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 90 min. After the wells were washed, the plates were incubated at 37°C for 1 h in the presence of peroxidase-conjugated goat F(ab′)2 fragment to human IgG Fc (gamma chain specific; at 1/6,000) (Cappel, France). For the immunoglobulin isotype determination, the monoclonal antibodies were purchased from Unipath (Bedford, United Kingdom) and corresponded to mouse anti-IgG1 (clone NL16) at 1/2,000, anti-IgG3 (clone ZG4) at 1/10,000, and anti-IgG4 (clone GB7B) at 1/30,000. Anti-IgG2 antibody (clone HP6002) was used at 1/10,000 and purchased from Sigma. Plates were treated as previously described (1), and optical density (OD) values at 450 nm were read by using Titertek multiscan apparatus (Flow Laboratories). The ELISA reader was set so as to subtract the reading of a blank control from the test samples. Each plasma sample was analyzed in the presence of 10 negative-control and 10 positive-control plasma samples. In addition, a negative-control standard (corresponding to a pool of plasma samples from naïve French donors) and a positive-control standard (corresponding to a pool of positive plasma samples from Senegalese donors) were included in each assay. A sample was considered positive (i.e., above the threshold of positivity) if the mean OD reading of the duplicates was higher than the mean OD value plus 3 standard deviations (SD) of the negative samples. Therefore, each absorbance value above the threshold was considered a positive OD.

Lymphoproliferation assays.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated from heparinized whole blood by Histopaque-1077 density gradient (Sigma Diagnosis, St. Louis, MO) and washed three times in PBS. Cultures of peripheral blood mononuclear cells were grown in 96-well round-bottomed plates (Nunclon) at a final concentration of 106 cells/ml and in a total volume of 200 μl of RPMI 1640 culture medium supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated pooled human serum AB (from the French National Center for Blood Transfusion, France), 1 mM glutamine, 35 mM HEPES, 1% sodium pyruvate, 2 g/liter sodium bicarbonate, and 10 mg/liter gentamicin. The peptides tested were added at a final concentration of 10 μg/ml. The plates were thereafter incubated at 37°C in a water-saturated atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Unstimulated (control) and stimulated cells were cultured in parallel. For a positive control, we used tuberculin (purified protein-derived tuberculin from the Statens Serum Institute, Copenhagen, Denmark) at a final concentration of 2.5 μg/ml. Cultures were pulsed on day 6 with [3H]thymidine (1 μCi per well) 16 h before harvesting, and the radioactivity incorporated was evaluated using a liquid scintillation counter. Cells from five unexposed donors tested under the same conditions with the various peptides were included as negative controls (no significant proliferative response was observed using lymphocytes of the unexposed donors). Results are expressed as stimulation indices (SI), defined as the mean counts per minute (cpm) of cells recovered from triplicate wells containing antigen divided by the mean cpm of control cells recovered from triplicate wells without antigen. The cutoff value for positivity was a SI value higher than 2 and a change in cpm of >1,000.

Statistical analysis.

Mean antibody responses were determined on antibody “responders,” i.e., on individuals with positive OD values. The Spearman rank correlation test was used for comparison of antibody responses in the different age groups (Stat View software; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). The relationship between all the antibody responses (using continuous data) and the risk of malaria attack occurrence during the 12 months following the blood sampling was tested using a Poisson regression model where the number of malaria attacks was tested as the dependent variable and the number of days of follow-up (i.e., exposure to P. falciparum infection) as well as antibody responses as the independent variables (Stata software; Stata Corporation, College Station, TX). The relative risk associated with the different variables within each age group was estimated by the generalized estimating equation model. This model is based on the inclusion or exclusion of the antibody responses tested, and in each case, the fraction of the clinical immunity acquired in each age group and attributable to each LSP peptide response was calculated. The effect of antibody response was tested separately for each of the 17 LSP and was considered significant only when its P value was below 0.003 (= 0.05/17; i.e., after Bonferroni's correction) to take into account the multiplicity of tests.

RESULTS

Antigenicity of the nonrepeat (LSA-3-NRI and LSA-3-NRII) and repeat (LSA-3-Re) peptides of LSA-3.

We first determined in the inhabitants of Dielmo, Senegal, the cellular and humoral responses directed against three short peptides, NRI, NRII, and RE, which cover DG297, the recombinant protein with which most protection data has been obtained in primates as described previously (1, 4, 21). Results from lymphoproliferative assays carried out in various age groups are shown in Table 1. Out of 143 Dielmo inhabitants tested, 39% responded to peptide LSA-3-NRI, 37% responded to LSA-3-NRII, and 44% responded to LSA-3-Re. The prevalence of responders was high in children less than 10 years old, slightly lower in adolescents (11 to 15 years old), and highest in young adults (16 to 20 years old). However, the prevalence decreased in subjects older than 20 years, in contrast with responses to many other malarial antigens (26-28). The association between a decrease in proliferative response and an increase in age for the three synthetic peptides tested was more prominent in the 143 villagers tested (as indicated by Spearman rank correlation tests) for LSA-3-Re (ρ = −0.287; P = 0.0005) than for LSA-3-NRI (ρ = −0.218; P = 0.008) and for LSA-3-NRII (ρ = −0.152; P = 0.067).

TABLE 1.

Results of the lymphoproliferative assays carried out in Dielmo, Senegal, using three peptides encompassing the repeat and nonrepeat subregions of LSA-3

| Age group (yr) | % of responders (n/N)a | Mean SI ± SDb

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSA-3-NRI | LSA-3-NRII | LSA-3-Re | ||

| 3-5 | 40.00 (10/25) | 3.77 ± 0.90 | 3.32 ± 0.86 | 3.84 ± 1.33 |

| 6-10 | 50.00 (13/26) | 3.74 ± 1.20 | 3.61 ± 0.91 | 3.88 ± 0.96 |

| 11-15 | 36.40 (8/22) | 3.96 ± 1.38 | 4.86 ± 1.24 | 4.35 ± 1.38 |

| 16-20 | 64.70 (11/17) | 3.78 ± 0.92 | 3.45 ± 1.05 | 3.78 ± 1.42 |

| 21-40 | 31.40 (11/35) | 3.55 ± 1.23 | 3.42 ± 0.89 | 3.15 ± 0.77 |

| >40 | 16.70 (3/18) | 3.48 ± 1.21 | 2.46 ± 0.43 | 3.72 ± 1.24 |

| Total | 39.20 (56/143) | 3.73 ± 1.09 | 3.62 ± 1.10 | 3.77 ± 1.17 |

For each age group, the percentage of responders to one peptide or all three peptides is shown. The number of responding individuals (n) and the total number of subjects tested in each age group (N) is shown in parentheses.

The mean stimulation index ± standard deviation is shown for each peptide. The mean SI of mononuclear cell proliferation is given with reference to the control wells (i.e., autologous cells maintained in complete culture medium but without antigen). LSA-3-NRI and LSA-3-NRII correspond to the nonrepeat regions of LSA-3, and LSA-3-Re corresponds to the repeat region of the antigen.

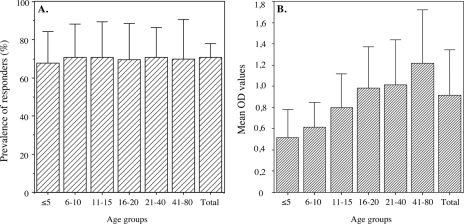

Antibody responses determined by ELISAs showed a marked difference between repeat and nonrepeat regions. Although the prevalence of antibody responses against LSA-3-NRI and LSA-3-NRII was high (i.e., 40% and 60%, respectively, of the individuals tested [data not shown]), the mean antibody responses were low and did not change much with age. Of note, both the prevalence and level of antibodies directed to the repeat region LSA-3-Re were high, with a prevalence of ca. 70% in children ≤5 years old, and the mean OD values increased with age as illustrated in Fig. 2.

FIG. 2.

Prevalence of individuals having antibodies to the LSA-3-Re repeat and trend for increase with age in the mean levels of antibodies in Dielmo, Senegal. The percentages of responders to LSA-3-Re (A) and the mean levels of antibody responses to LSA-3-Re antigen (B) are shown for various age groups (age in years). The total number of villagers tested was 143, and the number of individuals included in each age group is the same as that indicated in Table 1. The bars in panel A correspond to 95% confidence intervals of the percentages, and the bars in panel B correspond to standard deviations.

Immune responses to 17 long synthetic peptides spanning the LSA-3 protein.

Further studies relied on 17 LSP covering most of the 210-kDa LSA-3 protein, and the antigenicity of LSA-3 was tested in inhabitants of the Dielmo and Ndiop villages in Senegal.

T-cell assays of the inhabitants of Dielmo, Senegal, showed that with the notable exception of LSP14 and LSP16, which were recognized by only 3.1% and 9.4% of the individuals, respectively, the other 15 LSP induced a lymphoproliferative response in 17% to 50% of the inhabitants of Dielmo studied (Table 2). The highest stimulation indices were found in Dielmo for LSP13, a peptide derived from the repeat region of LSA-3 (mean SI ± SD, 14.2 ± 21.3). A somewhat different pattern was found in 43 inhabitants from Ndiop, Senegal (Table 2) in whom the highest prevalences of cellular responses were found for LSP10, LSP11, and LSP12, followed by LSP17, LSP16, LSP4, and LSP9. Prevalences of responses to LSP14 and -16 were markedly higher in Ndiop (reaching 25.6 and 48.8%) than in Dielmo (P = 0.072 and P = 0.0071 for LSP14 and LSP16, respectively) despite the lower transmission prevailing in Ndiop. T-cell responses were thus detected in the two villages to every single peptide tested, sometimes at prevalences above 55% in Ndiop. The combined pattern of individual responses suggests that each peptide likely defines an individual, non-cross-reactive epitope. Finally, the T-cell antigenicity of the protein is supported by the fact that the prevalences of some proliferative responses in the presence of certain LSA-3 peptides were as high in inhabitants from Ndiop receiving 10-fold-less infected mosquito bites than in Dielmo.

TABLE 2.

Proliferative responses of mononuclear cells obtained from inhabitants of the villages of Dielmo and Ndiop in Senegal by using 17 long synthetic peptidesa

| Peptide testedb | Dielmo

|

Ndiop

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of responders (n/N)c | Mean SI ± 1 SD | % of responders (n/N) | Mean SI ± 1 SD | |

| LSP2 | 18.6 (13/70) | 4.6 ± 3.3 | 37.2 (16/43) | 11.3 ± 15.8 |

| LSP1 | 30 (21/70) | 4.6 ± 3.3 | 18.6 (8/43) | 4.9 ± 3.4 |

| LSP14 | 3.1 (1/32) | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 25.6 (11/43) | 3.2 ± 1.3 |

| LSP13 | 50.0 (35/70) | 14.2 ± 21.3 | 16.3 (7/43) | 4.1 ± 1.9 |

| LSP12 | 42.9 (30/70) | 6.1 ± 5.7 | 55.8 (24/43) | 9.9 ± 13.3 |

| LSP11 | 41.4 (29/70) | 5.8 ± 5.4 | 55.8 (24/43) | 14.5 ± 15.6 |

| LSP10 | 37.1 (26/70) | 4.2 ± 2.7 | 55.8 (24/43) | 10.0 ± 8.8 |

| LSP9 | 30.0 (21/70) | 4.4 ± 3.2 | 44.2 (19/43) | 12.1 ± 13.2 |

| LSP8 | 25.7 (18/70) | 4.4 ± 3.9 | 13.9 (6/43) | 8.4 ± 4.9 |

| LSP7 | 17.1 (12/70) | 12.9 ± 19.6 | 20.9 (9/43) | 5.6 ± 4.0 |

| LSP6 | 28.6 (20/70) | 6.9 ± 8.9 | 23.2 (10/43) | 4.3 ± 2.9 |

| LSP5 | 32.9 (23/70) | 7.9 ± 9.8 | 34.9 (15/43) | 9.4 ± 12.3 |

| LSP4 | 27.1 (19/70) | 7.5 ± 12.6 | 46.5 (20/43) | 9.1 ± 10.1 |

| LSP3 | 27.1 (19/70) | 4.0 ± 2.4 | 39.5 (17/43) | 11.2 ± 13.2 |

| LSP15 | 25.0 (8/32) | 3.4 ± 1.2 | 4.6 (2/43) | 2.1 ± 0.1 |

| LSP16 | 9.4 (3/32) | 2.3 ± 0.3 | 48.8 (21/43) | 8.2 ± 7.5 |

| LSP17 | 25.0 (8/32) | 4.1 ± 1.5 | 51.2 (22/43) | 8.1 ± 8.9 |

| PPD | 74.3 (52/70) | 19.2 ± 21.8 | 90.7 (39/43) | 89.9 ± 110.4 |

Mononuclear cells were cultured in the presence of the various LSA-3-derived LSP.

The 17 LSP tested (LSP1 to LSP17, which encompass most of the LSA-3 protein and are shown in order from the N terminus to the the C terminus of LSA-3) are shown. Purified protein-derived tuberculin (PPD) was used as a positive control.

The percentage of responders to each peptide is shown. The number of responding individuals (n) and the total number of subjects tested in each age group (N) is shown in parentheses.

IgG antibodies directed against the 17 LSP were evaluated in the plasma samples from 91 individuals living in Dielmo, Senegal, and 60 individuals from Ndiop, Senegal. As shown in Table 3, each of the LSP defined at least one B-cell epitope but with a wide range of prevalences and of antibody levels. In agreement with the results initially obtained with the smaller LSA-3-Re peptide, the highest antibody levels were obtained in response to LSP12 in Dielmo and in response to a peptide situated in the R2 repeat region of LSA-3 in Ndiop. Antibody prevalence was also maximal to this peptide in Dielmo. However, both repeat and nonrepeat regions of LSA-3 were targeted by specific antibodies, with comparable, high prevalences. This was seen for instance for the nonrepeat peptides LSP4, -7, and -10 encompassing a nonrepeat region, compared to the three peptides LSP12, -13, and -14 encompassing the R2 repeat region, which is an unusual finding. Here as well, the combined pattern of individual responses suggests that each peptide likely defines at least one individual, B-cell epitope, not cross-reactive with the remaining epitopes as described previously (20), except for the three peptides (LSP12, -13, and -14) derived from the R2 repeat region. IgG isotype-specific antibodies were analyzed in a subset of 33 individuals from Dielmo. Antibodies to the 17 peptides were found to include each of the four IgG subclasses, with a high prevalence of IgG3. The highest IgG3 levels were found in response to LSP12, with 30 out of 33 individuals responding specifically to this long synthetic peptide, but no particular indication regarding the pattern of anti-LSA-3 IgG subclass responses was identified (data not shown).

TABLE 3.

Prevalence of IgG antibodies to the different LSP corresponding to subregions of LSA-3 antigen in inhabitants of the villages of Dielmo and Ndiop in Senegala

| Peptideb | Dielmo

|

Ndiop

|

Mean OD ± 1 SD for negative controlse | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of responders (n/N)c | Mean OD ± 1 SDd | % of responders (n/N) | Mean OD ± 1 SD | ||

| LSP2 | 6.6 (6/91) | 0.523 ± 0.459 | 1.7 (1/60) | 0.055 | 0.180 ± 0.05 |

| LSP1 | 25.3 (23/91) | 0.699 ± 0.328 | 13.3 (8/60) | 0.686 ± 0.266 | 0.421 ± 0.25 |

| LSP14 | 59.3 (54/91) | 0.690 ± 0.406 | 43.3 (26/60) | 0.408 ± 0.274 | 0.200 ± 0.09 |

| LSP13 | 51.7 (47/91) | 0.581 ± 0.557 | 20.0 (12/60) | 0.147 ± 0.130 | 0.170 ± 0.05 |

| LSP12 | 84.6 (77/91) | 1.620 ± 0.726 | 75.0 (45/60) | 0.907 ± 0.534 | 0.230 ± 0.11 |

| LSP11 | 28.6 (26/91) | 0.418 ± 0.477 | 21.7 (13/60) | 0.336 ± 0.286 | 0.160 ± 0.05 |

| LSP10 | 75.8 (69/91) | 0.848 ± 0.748 | 61.7 (37/60) | 0.759 ± 0.588 | 0.160 ± 0.03 |

| LSP9 | 29.7 (27/91) | 0.195 ± 0.237 | 18.3 (11/60) | 0.307 ± 0.322 | 0.190 ± 0.04 |

| LSP8 | 33.0 (30/91) | 0.399 ± 0.420 | 23.3 (14/60) | 0.513 ± 0.495 | 0.150 ± 0.04 |

| LSP7 | 63.7 (58/91) | 0.639 ± 0.517 | 48.3 (29/60) | 0.690 ± 0.560 | 0.160 ± 0.05 |

| LSP6 | 48.3 (44/91) | 0.777 ± 0.625 | 35.0 (21/60) | 0.775 ± 0.601 | 0.220 ± 0.09 |

| LSP5 | 39.6 (36/91) | 0.668 ± 0.558 | 18.3 (11/60) | 0.761 ± 0.632 | 0.210 ± 0.09 |

| LSP4 | 79.1 (72/91) | 0.885 ± 0.655 | 78.3 (47/60) | 0.722 ± 0.498 | 0.250 ± 0.02 |

| LSP3 | 45.1 (41/91) | 0.903 ± 0.697 | 31.7 (19/60) | 0.420 ± 0.507 | 0.190 ± 0.07 |

| LSP15 | 1.1 (1/91) | 0.133 | 1.7 (1/60) | 0.881 | 0.240 ± 0.11 |

| LSP16 | 8.8 (8/91) | 0.354 ± 0.250 | 6.7 (4/60) | 0.515 ± 0.419 | 0.370 ± 0.14 |

| LSP17 | 18.0 (16/89) | 0.632 ± 0.368 | 5.0 (3/60) | 0.394 ± 0.218 | 0.400 ± 0.15 |

The optical density values of the IgG responses (corresponding to the mean OD tests minus the mean OD of the negative controls plus 3 standard deviations) are indicated.

LSP1 to LSP17, which encompass most of the LSA-3 protein, are shown in order from the N terminus to the C terminus of LSA-3.

For each of the different antigens tested (LSP1 to LSP17), the percentage of responders is shown. The number of responding individuals (n) and the total number of individuals (N) are shown in parentheses.

For each of the different antigens tested (LSP1 to LSP17), the mean net IgG OD ± 1 standard deviation is indicated.

Ten negative controls.

Age-specific patterns in subjects exposed to medium or high malaria transmission.

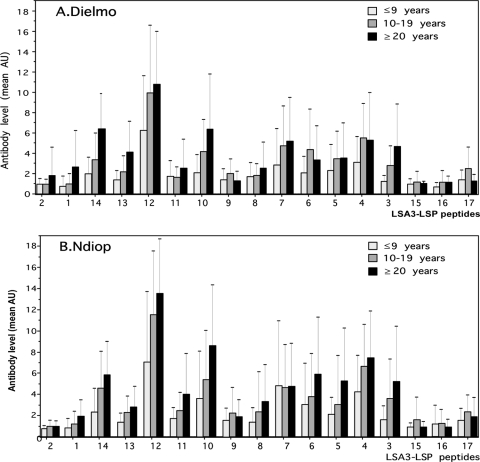

Since the inhabitants of the Dielmo and Ndiop villages in Senegal differ markedly in their level of exposure to infectious mosquito bites (13, 14) and the pattern of immune responses (27), we then compared anti-LSA-3 antibody responses as a function of age in both villages. A trend for an increase in antibody responses to several LSP was observed associated with age in Dielmo and Ndiop villages. Antibody responses to the repeat region, particularly to LSP12, -13, and -14 increased with age in Dielmo. There was also an increase of antibodies to several peptides from the nonrepeat region (i.e., LSP3 to LSP-7 and LSP10) with increasing age that indicated that higher doses of these immunogens were required to raise antibodies compared to LSP from the repeat region. The general patterns of age-dependent increase in antibody to the 17 peptides was largely superimposed for each LSP in the two villages (Fig. 3A and B), but the maximal levels reached were higher in Dielmo and a trend for a higher percentage of villagers with detectable antibody responses to each LSP was found in this village. Therefore, these results indicate that most parts of LSA-3 (with a few exceptions, such as LSP2, LSP15, and LSP16) are antigenic under natural conditions of exposure and elicit antibody responses both under medium or high malaria transmission conditions.

FIG. 3.

Levels of antibody responses to the 17 different LSP encompassing the LSA-3 protein in different age groups of inhabitants of the Dielmo and Ndiop villages in Senegal. The numbering of the different LSP tested correspond to that shown in Fig. 1, i.e., they are indicated from the N terminus to the C terminus of LSA-3. The absorbance values (AU) indicated in the figure correspond to the difference between test OD values minus the mean of the control OD values plus 3 SD.

Relationship between antibody responses and acquired clinical resistance to malaria.

The availability of very detailed clinical data led us to analyze antibody responses to each LSA-3 peptide in relation to the clinical attacks recorded over a period of 1 year following collection of the plasma samples. To this end, the 90 subjects from Dielmo, Senegal, were stratified into four age groups of 3 to 6 years of age (n = 12), 7 to 11 years of age (n = 10), 12 to 15 years of age (n = 11), and ≥16 years of age (n = 57).

The incidence of clinical malaria attacks occurring during the year following the blood sampling was recorded actively on a daily basis (Table 4). All the individuals were enrolled in this study at the same time in the same place, were equally exposed to malaria transmission, and had the same access to health services. No self-treatment, chemoprophylaxis, or effective antivectorial intervention was used by this population. The incidence of clinical malaria has been analyzed in a multivariate Poisson regression model including age in four groups (children aged 3 to 6 years old as reference group) and the LSA-3-specific antibody responses. In comparison to the children aged 3 to 6 years old, the acquired protection, i.e., immunity acquired with age was 41% (relative risk, 0.59), 77% (relative risk, 0.23), and 96% (relative risk, 0.04) by individuals aged 7 to 11, 12 to 15, and >16 years old, respectively.

TABLE 4.

Fraction of clinical immunity attributable to LSA-3- or LSP10-specific antibody responses calculated for the different age groups of inhabitants living in Dielmo, Senegal

| Age group (yr) | No. of individuals | No. of malaria attacks | No. of days of follow-up | Annual incidence rate of malaria attacksa | Age variation of the relative risk of malaria attack/year (95% confidence interval)b

|

% of clinical immunity attributable to LSP10-specific responses | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSP10− | LSP10+ | ||||||

| 3-6 | 12 | 30 | 3,802 | 2.88 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| 7-11 | 10 | 15 | 3,454 | 1.59 | 0.586 (0.313-1.10) | 0.680 (0.361-1.28) | 22.7 |

| 12-15 | 11 | 6 | 3,507 | 0.62 | 0.233 (0.096-0.563) | 0.409 (0.158-1.05) | 22.9 |

| ≥16 | 57 | 8 | 18,059 | 0.16 | 0.039 (0.015-0.103) | 0.059 (0.022-0.157) | 2.1 |

| Total | 90 | 59 | 28,822 | 0.75 | |||

The incidence rates of malaria attacks in inhabitants living in Dielmo, Senegal, were determined for different age groups.

The age-dependent changes in the relative risk of malaria attacks when excluding the effect of anti-LSP10 specific antibody responses (LSP10−) or when taking into account the effect of anti-LSP10 specific antibody responses (LSP10+) are shown. The total age variation of the relative risk of malaria attack/year (95% confidence interval) for LSP10 was 2.83 (1.52-5.29).

Independent of age, antibody response to LSP10 was found to be significantly associated with a reduction by 2.8 (95% confidence interval, 1.5 to 5.3; P = 0.001 < 0.003 = 0.05/17, Bonferroni's correction for multiple tests) of the risk of malaria attack. The level of resistance to malaria due to age only, i.e., age-associated immunity independent of the antibody response to LSA-3 or LSP10, was estimated to be 32% (1 to 0.68), 59% (1 to 0.41), and 94% (1 to 0.06) in individuals aged 7 to 11, 12 to 15, and >15 years old, respectively. Therefore, the fraction of the immunity acquired by the children aged 7 to 15 years old in comparison to children aged 3 to 6 years old that could be associated with anti-LSP10 antibody response was estimated to be 22.7% (i.e., 41.4% − 32%)/41.4% in children 7 to 11 years of age and 22.9% [i.e., (76.7% − 59.1%)/76.7%] in children 12 to 15 years of age, whereas it was only marginal, 2% [i.e., (96.1% − 94%)/96.1%], for the individuals aged 16 years or more.

DISCUSSION

A detailed immunoepidemiological study of LSA-3, a Plasmodium falciparum preerythrocytic stage antigen with demonstrated potential as a malaria vaccine (4), was conducted in two villages of Senegal (West Africa). We used 3 short and 17 long synthetic peptides spanning almost all of the LSA-3 protein. The latter peptides rely on a technology which accommodates the successful synthesis of long sequences and led us to gather an estimate of the antigenic content of all regions from this large protein and to further document our preliminary antigenic characterization of LSA-3 (1, 4).

Overall, lymphocyte and antibody assays indicate that each of the 17 overlapping long synthetic peptides spanning almost all of LSA-3 contain both B- and T-cell epitopes within the same sequence, which is not surprising given the relatively large size of each peptide. The prevalence of responses is high, and some individuals exposed to malaria recognized most regions of LSA-3.

At the B-cell level, each individual studied had detectable antibodies against a minimum of 6 polypeptides and a maximum of 15 of the 17 polypeptides studied. Both the prevalences and levels of antibodies to the repeat and nonrepeat regions were high, and on some occasions, they were of comparable magnitude. This observation challenges the current concept that dominant B-cell epitopes segregate in repetitive regions (3, 7). These results differ from those reported for the circumsporozoite protein (CS), in which the repeat region is the main target of antibodies in subjects living in areas where malaria is endemic (5-7, 17), and conversely, in which immunodominant T-cell epitopes are located in the most polymorphic nonrepetitive C terminus of the protein (8, 15, 30, 33, 34). In this respect, LSA-3 stands closer to Plasmodium falciparum thrombospondin-related adhesive protein (PfTRAP) than to CS. Using 50 overlapping PfTRAP peptides, 26 Th cell epitopes along the entire protein were described using lymphocytes from Gambian adults (12). However, in the case of PfTRAP, only 10 out of 26 epitopes were found to be conserved, whereas the available data for LSA-3 showed conservation of the epitopes identified so far (4).

At the T-cell level, each of the individuals studied showed lymphocyte responses against at least 2 and up to 12 out of the 17 LSP analyzed. Although the prevalence of LSA-3-specific proliferative responses was expectedly lower than that of B-cell responses, the pattern of proliferative responses roughly paralleled that of antibody responses. The T-cell responses to the N-terminal LSP1 peptide confirm previous data gathered using short peptides within the same sequence (i.e., LSA-3-NRI and LSA-3-NRII) (1). However, the peak prevalence occurred early in age and exposure (11 to 15 years) and remained similar in older individuals. Finally, and again in contrast with the CS protein, the repeat region of LSA-3 was found to define a strong T-cell epitope. Comparison of the SI and prevalence of proliferating cells tested in the two villages in Senegal led to a consistent difference between Dielmo and Ndiop. Two peptides (LSP7 and LSP13) were inducing the highest SI in Dielmo, whereas LSP2, LSP3, LSP9, LSP10, and LSP11 which gave comparatively lower SI values were more strongly recognized in Ndiop. Obviously, different peptides were found associated with the most sustained proliferative responses observed in each of the two villages, which differ not only by malaria transmission rate but also by the genetic background of the inhabitants, with Serere dominating in Dielmo and Wolof and Fulani dominating in Ndiop. Nevertheless, the precise explanation of the differences observed in proliferative responses would need more investigations.

The prevalences of both B- and T-cell responses were not directly dependent on transmission levels, an observation which is also in agreement with the high antigenicity of each region of the protein. In Ndiop, Senegal, an area where malaria transmission is strictly seasonal, the pattern of responses to LSA-3 was largely similar to that found in Dielmo, Senegal (where malaria transmission is perennial and approximately 10 to 20 times higher than in Ndiop). Yet immune responses, particularly antibody levels, increased as a function of age and hence exposure to infected mosquito bites, at least during childhood and adolescence, to most peptides and thereafter reached a plateau. This phenomenon, and the lack of difference between Ndiop and Dielmo, suggest that the protein is highly antigenic and that exposure to low numbers of sporozoites in Ndiop, i.e., small amounts of antigen, is sufficient to induce consistent immune responses.

The epidemiological relationship observed between anti-LSP10 antibodies and acquired clinical protection is an additional point of interest, although its biological basis remains to be investigated further. The data showing that a significant percentage of acquired immunity between two age groups could be associated with LSA-3 antibody responses led us to formulate the hypothesis that LSA-3 is not only antigenic but that immune responses to this antigen may also correlate with the level of individual protection developed during the progressive process of its acquisition through cumulative exposure to malaria transmission. Of note, the potential association between anti-LSP10 antibodies and protection was consistently detected in the age groups during which the transition between nonprotection toward protection status was observed in these areas where malaria is endemic. In addition, and in line with other observations carried out in the same settings, the potential association between protection and antibodies to other antigens was also found to be stronger in the young age groups (26, 28). Anti-LSP10 antibodies could be either a surrogate marker of protection against the preerythrocytic stage or an effective component of a defense mechanism. Since LSA-3 was found to be able to induce protection (2, 4, 21, 29) and since anti-LSA-3 antibodies strongly inhibit P. falciparum sporozoite invasion into human hepatocytes, as well as P. yoelii sporozoite invasion into mouse hepatocytes (2) and can passively transfer protection in vivo (2), an antibody-mediated mechanism targeting the LSP10 region is a plausible hypothesis that would now deserve to be investigated. If confirmed by further studies, LSP10 should be incorporated into a vaccine so as to induce or boost existing responses in young children. Overall, the present results add further critical information to our initial immunological characterization of LSA-3 (1, 2, 4). This study led to the identification of numerous domains within LSA-3 that are highly antigenic in individuals exposed to malaria which might therefore correspond to immune effector targets and further document the potential of LSA-3 as a valuable malaria preerythrocytic stage vaccine candidate.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the villagers of Dielmo and Ndiop in Senegal for their active and continuing participation in the project, to the medical staff involved in both villages, and to E. M. Fall for his technical assistance. We particularly thank the national authorities in Senegal for their continuous support to the project.

This study was supported by a VIHPAL grant from the French Ministry of Research.

Editor: J. F. Urban, Jr.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 12 January 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.BenMohamed, L., H. Gras-Masse, A. Tartar, P. Daubersies, K. Brahimi, M. Bossus, A. Thomas, and P. Druilhe. 1997. Lipopeptide immunization without adjuvant induces potent and long-lasting B, T-helper, and cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses against a malaria liver stage antigen in mice and chimpanzees. Eur. J. Immunol. 271242-1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brahimi, K., E. Badell, J. P. Sauzet, L. BenMohamed, P. Daubersies, C. Guerin-Marchand, G. Snounou, and P. Druilhe. 2001. Human antibodies against Plasmodium falciparum liver-stage antigen 3 cross-react with Plasmodium yoelii preerythrocytic-stage epitopes and inhibit sporozoite invasion in vitro and in vivo. Infect. Immun. 693845-3852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dame, J. B., J. L. Williams, T. F. McCutchan, J. L. Weber, R. A. Wirtz, W. T. Hockmeyer, W. L. Maloy, J. D. Haynes, I. Schneider, D. Roberts, et al. 1984. Structure of the gene encoding the immunodominant surface antigen on the sporozoite of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Science 225593-599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daubersies, P., A. W. Thomas, P. Millet, K. Brahimi, J. A. Langermans, B. Ollomo, L. BenMohamed, B. Slierendregt, W. Eling, A. Van Belkum, G. Dubreuil, J. F. Meis, C. Guerin-Marchand, S. Cayphas, J. Cohen, H. Gras-Masse, P. Druilhe, and L. B. Mohamed. 2000. Protection against Plasmodium falciparum malaria in chimpanzees by immunization with the conserved pre-erythrocytic liver-stage antigen 3. Nat. Med. 61258-1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Del Giudice, G., Q. Cheng, D. Mazier, N. Berbiguier, J. A. Cooper, H. D. Engers, C. Chizzolini, A. S. Verdini, F. Bonelli, A. Pessi, et al. 1988. Immunogenicity of a non-repetitive sequence of Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite protein in man and mice. Immunology 63187-191. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Del Giudice, G., J. A. Cooper, J. Merino, A. S. Verdini, A. Pessi, A. R. Togna, H. D. Engers, G. Corradin, and P. H. Lambert. 1986. The antibody response in mice to carrier-free synthetic polymers of Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite repetitive epitope is I-Ab-restricted: possible implications for malaria vaccines. J. Immunol. 1372952-2955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Del Giudice, G., H. D. Engers, C. Tougne, S. S. Biro, N. Weiss, A. S. Verdini, A. Pessi, A. A. Degremont, T. A. Freyvogel, P. H. Lambert, et al. 1987. Antibodies to the repetitive epitope of Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite protein in a rural Tanzanian community: a longitudinal study of 132 children. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 36203-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doolan, D. L., H. P. Beck, and M. F. Good. 1994. Evidence for limited activation of distinct CD4+ T cell subsets in response to the Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite protein in Papua New Guinea. Parasite Immunol. 16129-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Druilhe, P. L., L. Renia, and D. A. Fidock. 1998. Immunity to liver stages, p. 513-543. In I. W. Sherman (ed.), Malaria: parasite biology, pathogenesis, and protection. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 10.Egan, J. E., J. L. Weber, W. R. Ballou, M. R. Hollingdale, W. R. Majarian, D. M. Gordon, W. L. Maloy, S. L. Hoffman, R. A. Wirtz, I. Schneider, et al. 1987. Efficacy of murine malaria sporozoite vaccines: implications for human vaccine development. Science 236453-456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Escalante, A. A., H. M. Grebert, R. Isea, I. F. Goldman, L. Basco, M. Magris, S. Biswas, S. Kariuki, and A. A. Lal. 2002. A study of genetic diversity in the gene encoding the circumsporozoite protein (CSP) of Plasmodium falciparum from different transmission areas—XVI. Asembo Bay Cohort Project. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 12583-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flanagan, K. L., M. Plebanski, P. Akinwunmi, E. A. Lee, W. H. Reece, K. J. Robson, A. V. Hill, and M. Pinder. 1999. Broadly distributed T cell reactivity, with no immunodominant loci, to the pre-erythrocytic antigen thrombospondin-related adhesive protein of Plasmodium falciparum in West Africans. Eur. J. Immunol. 291943-1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fontenille, D., L. Lochouarn, N. Diagne, C. Sokhna, J. J. Lemasson, M. Diatta, L. Konate, F. Faye, C. Rogier, and J. F. Trape. 1997. High annual and seasonal variations in malaria transmission by anophelines and vector species composition in Dielmo, a holoendemic area in Senegal. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 56247-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fontenille, D., L. Lochouarn, M. Diatta, C. Sokhna, I. Dia, N. Diagne, J. J. Lemasson, K. Ba, A. Tall, C. Rogier, and J. F. Trape. 1997. Four years' entomological study of the transmission of seasonal malaria in Senegal and the bionomics of Anopheles gambiae and A. arabiensis. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 91647-652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Good, M. F., D. Pombo, I. A. Quakyi, E. M. Riley, R. A. Houghten, A. Menon, D. W. Alling, J. A. Berzofsky, and L. H. Miller. 1988. Human T-cell recognition of the circumsporozoite protein of Plasmodium falciparum: immunodominant T-cell domains map to the polymorphic regions of the molecule. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 851199-1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoffman, S. L., D. Isenbarger, G. W. Long, M. Sedegah, A. Szarfman, S. Mellouk, and W. R. Ballou. 1990. T lymphocytes from mice immunized with irradiated sporozoites eliminate malaria from hepatocytes. Bull. W. H. O. 68132-137. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lopez, J. A., M. A. Roggero, O. Duombo, J. M. Gonzalez, R. Tolle, O. Koita, M. Arevalo-Herrera, S. Herrera, and G. Corradin. 1996. Recognition of synthetic 104-mer and 102-mer peptides corresponding to N- and C-terminal nonrepeat regions of the Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite protein by sera from human donors. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 55424-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merrifield, R. B. 1963. Solid-phase peptide synthesis. The synthesis of a tetrapeptide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 852149-2152. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nardin, E. H., V. Nussenzweig, R. S. Nussenzweig, W. E. Collins, K. T. Harinasuta, P. Tapchaisri, and Y. Chomcharn. 1982. Circumsporozoite proteins of human malaria parasites Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax. J. Exp. Med. 15620-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perlaza, B. L., J. P. Sauzet, A. T. Balde, K. Brahimi, A. Tall, G. Corradin, and P. Druilhe. 2001. Long synthetic peptides encompassing the Plasmodium falciparum LSA-3 are the target of human B and T cells and are potent inducers of B helper, T helper and cytolytic T cell responses in mice. Eur. J. Immunol. 312200-2209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perlaza, B. L., C. Zapata, A. Z. Valencia, S. Hurtado, G. Quintero, J. P. Sauzet, K. Brahimi, C. Blanc, M. Arevalo-Herrera, P. Druilhe, and S. Herrera. 2003. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of Plasmodium falciparum liver-stage Ag-3 in Aotus lemurinus griseimembra monkeys. Eur. J. Immunol. 331321-1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rieckmann, K. H. 1990. Human immunization with attenuated sporozoites. Bull. W. H. O. 6813-16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robson, K. J., A. Dolo, I. R. Hackford, O. Doumbo, M. B. Richards, M. M. Keita, T. Sidibe, A. Bosman, D. Modiano, and A. Crisanti. 1998. Natural polymorphism in the thrombospondin-related adhesive protein of Plasmodium falciparum. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 5881-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roggero, M. A., B. Filippi, P. Church, S. L. Hoffman, U. Blum-Tirouvanziam, J. A. Lopez, F. Esposito, H. Matile, C. D. Reymond, N. Fasel, et al. 1995. Synthesis and immunological characterization of 104-mer and 102-mer peptides corresponding to the N- and C-terminal regions of the Plasmodium falciparum CS protein. Mol. Immunol. 321301-1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roggero, M. A., C. Servis, and G. Corradin. 1997. A simple and rapid procedure for the purification of synthetic polypeptides by a combination of affinity chromatography and methionine chemistry. FEBS Lett. 408285-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rogier, C., A. Tall, N. Diagne, D. Fontenille, A. Spiegel, and J. F. Trape. 1999. Plasmodium falciparum clinical malaria: lessons from longitudinal studies in Senegal. Parassitologia 41255-259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rogier, C., and J. F. Trape. 1995. Study of premunition development in holo- and meso-endemic malaria areas in Dielmo and Ndiop (Senegal): preliminary results, 1990-1994. Med. Trop. (Marseilles) 5571-76. (In French.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roussilhon, C., C. Oeuvray, C. Muller-Graf, A. Tall, C. Rogier, J. F. Trape, M. Theisen, A. Balde, J. L. Perignon, and P. Druilhe. 2007. Long-term clinical protection from falciparum malaria is strongly associated with IgG3 antibodies to merozoite surface protein 3. PLoS Med. 4e320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sauzet, J. P., B. L. Perlaza, K. Brahimi, P. Daubersies, and P. Druilhe. 2001. DNA immunization by Plasmodium falciparum liver-stage antigen 3 induces protection against Plasmodium yoelii sporozoite challenge. Infect. Immun. 691202-1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sinigaglia, F., M. Guttinger, D. Gillessen, D. M. Doran, B. Takacs, H. Matile, A. Trzeciak, and J. R. Pink. 1988. Epitopes recognized by human T lymphocytes on malaria circumsporozoite protein. Eur. J. Immunol. 18633-636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomas, A. W., B. Slierendregt, B. Mons, and P. Druilhe. 1994. Chimpanzees and supporting models in the study of malaria pre-erythrocytic stages. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 89(Suppl. 2)111-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trape, J. F., C. Rogier, L. Konate, N. Diagne, H. Bouganali, B. Canque, F. Legros, A. Badji, G. Ndiaye, P. Ndiaye, et al. 1994. The Dielmo project: a longitudinal study of natural malaria infection and the mechanisms of protective immunity in a community living in a holoendemic area of Senegal. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 51123-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zevering, Y., R. A. Houghten, I. H. Frazer, and M. F. Good. 1990. Major population differences in T cell response to a malaria sporozoite vaccine candidate. Int. Immunol. 2945-955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zevering, Y., C. Khamboonruang, K. Rungruengthanakit, L. Tungviboonchai, J. Ruengpipattanapan, I. Bathurst, P. Barr, and M. F. Good. 1994. Life-spans of human T-cell responses to determinants from the circumsporozoite proteins of Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 916118-6122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]