Abstract

We describe a case of brain abscesses with gas formation following otitis media, for which the patient treated himself by placing clay in his ear. Several microorganisms, including Clostridium glycolicum, were cultured from material obtained from the patient. This is the first report of an infection in an immunocompetent patient associated with this microorganism.

CASE REPORT

A previously healthy male patient, 62 years of age, presented in our hospital with severe pain in his right ear. Ten days prior to presentation, the patient had started treating his earache by placing pieces of clay in his external auditory meatus. When the patient was seen in our hospital, the clay was removed and the ear, nose, and throat specialist diagnosed acute otitis media and otitis externa, with perforation of the tympanum. Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid was prescribed, and the patient was discharged home. Two days later, the patient presented again with headache, earache, hearing loss, and neck stiffness. A physical examination indicated that the patient was Kernig's sign and Brudzinski's sign positive, and there was a nystagmus toward the right and diplopia. He was febrile (39.5°C) and hypertensive (160/100 mm Hg) but was well orientated. The patient was admitted with suspected bacterial meningitis secondary to otitis media, and blood was taken for the determination of the cell count, chemistry, and culture, for which it was inoculated into paired aerobic and anaerobic bottles of the Bactec blood culture system (Becton Dickinson Diagnostic Instrument Systems, France). The C-reactive protein level of the patient upon admission was 168 mg/liter, and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 105 mm/h. Following a computed tomography (CT) scan, lumbar puncture was performed using standard aseptic techniques, with collection of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for the determination of the cell count, chemistry, Gram stain, and culture. CSF examination revealed an increased leukocyte count (1,733/mm3), an increase in the protein level (1.98 g/liter), and decreased glucose (1.1 mmol/liter, with 8.9 mmol/liter serum glucose). No leukocytes or microorganisms were seen via Gram staining. Culture results are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Microorganisms isolated from clinical materials

| Date (day/mo) | Material | Culture result | Culture details |

|---|---|---|---|

| 17/01 | Blood | C. glycolicum | Anaerobic bottle (Bactec) |

| 17/01 | CSF | C. cadaveris | Anaerobic culture for 48 h |

| 18/01 | Pus from mastoid | 2 types of E. coli | Sheep blood and MacConkey agar |

| 2 types of anaerobic gram-positive rods | Anaerobic culture for 48 h, strains dead | ||

| 23/01 | Necrotic tissue mastoid | Streptococcus spp., 2 types of E. coli, coagulase-negative staphylococcus, Brevibacterium spp. | Sheep blood agar |

| C. glycolicum | Brucella blood agar, anaerobic culture for 48 h |

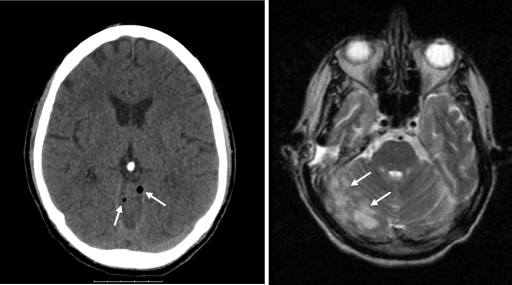

A CT scan made before lumbar puncture showed signs of otitis media and mastoiditis on the right side. Gas was seen along the tentorium and vermis cerebri (Fig. 1), compatible with intracranial gas formation. Broad-spectrum antibiotic treatment with floxacillin (flucloxacillin), ceftazidime, and metronidazole was started. Surgical intervention aimed at draining the mastoid was carried out one day after admission by the ear, nose, and throat specialists. Direct inspection during surgery revealed abundant pus and necrotic tissue extending to the brain tissue. Swabs of pus present in the mastoid were taken for culture; however, no samples were collected specifically for anaerobic culture. The swabs were plated on sheep blood agar, MacConkey agar, and chocolate agar plates (Oxoid, United Kingdom) which were incubated under aerobic conditions and on one sheep blood agar plate which was incubated under anaerobic conditions.

FIG. 1.

CT scan images showing intracerebral gas along the vermis (arrows; left panel) and cerebellitis (arrows; right panel).

The patient's condition deteriorated in the days following admission, when he required mechanical ventilation following an epileptic seizure. A magnetic resonance imaging scan showed signs of encephalitis and thrombosis of the right sigmoidal sinus, and the patient was transferred to a tertiary care unit for neurosurgical care.

Necrotic tissue from the mastoid was subsequently excised, and intracerebral pus was drained; samples were placed in a sterile container for culture. Although no anaerobic transport medium was used, the transport time to the microbiology unit was sufficiently short to ensure survival of aerobic as well as anaerobic microorganisms. Gram staining of the excised necrotic tissue showed few leukocytes and abundant gram-negative rods, gram-positive cocci, and gram-positive rods. Material was plated on sheep blood agar (Becton Dickinson), MacConkey agar (Oxoid), chocolate agar, and Columbia agar (containing 10 mg of nalidixic acid/liter) plates (Becton Dickinson) and incubated under aerobic conditions or plated on a Brucella blood agar plate (Becton Dickinson) and incubated under anaerobic conditions. Also, material was cultured for fungi and mycobacteria, but these cultures remained negative. Culture results are represented in Table 1. On the Clostridium spp. which were cultured, we performed an API Rapid ID 32 A test (BioMerieux, France). The result was confirmed by sequencing the 16S rRNA region of the genome of both strains (5).

Following excision and drainage of the intracranial necrotic tissue and pus, the patient's inflammatory parameters improved rapidly. His neurological condition nevertheless remained poor for several weeks, but he eventually recovered with residual profound bilateral hearing loss, for which he received two cochlear implants.

Brain abscesses are focal suppurative processes, usually originating from a chronic otitis media, mastoiditis, sinusitis, or dental infection, from penetrating traumas or postsurgery. Brain abscesses are associated with otitis media in around 30% of cases. Less frequently, brain abscesses are complications of septicemia or dental infections. In a quarter of cases, the origin of the brain abscess is not known (7, 12). It is estimated that only 1 in 2 × 106 episodes of otitis media results in a brain abscess (9).

Microorganisms most commonly found in otogenic brain abscesses include streptococci, staphylococci, Enterobacteriaceae, and anaerobic bacteria, as well as fungi, in particular, Aspergillus spp. In about a third of cases, multiple microorganisms are cultured from a brain abscess, the majority of which have only a single microorganism (1, 2).

Gas-containing brain abscesses may result from either bacterial fermentation or penetration of gas through an abnormal communication between the exterior and intracranium. In the case we present, imaging suggests that the presence of intracranial gas was due to bacterial fermentation, as no communication was seen in CT and magnetic resonance imaging scans. Although Clostridium species, which are often associated with gas formation, were isolated from this patient, C. glycolicum and C. cadaveris are rarely found in infections, and therefore, limited clinical data on gas formation during infections by these two species exist. Both species, however, are able to form gas. Biochemically, they can be distinguished by gelatin hydrolysis, indole testing, and milk digestion, for which C. cadaveris tests positive and C. glycolicum tests negative. C. glycolicum was cultured twice, from blood as well as from necrotic intracranial tissue, whereas C. cadaveris was cultured only once from CSF, and only sporadic colonies were seen. The case for involvement of C. glycolicum is therefore stronger than that for C. cadaveris. However, pus taken at the first surgical intervention initially yielded two types of anaerobic gram-positive rods, with different colony morphologies. Unfortunately, these strains could not be identified (Table 1).

Other microorganisms associated with gas formation include some Enterobacteriaceae (13), Bacteroides spp. (8), Peptostreptococcus (10), and Fusobacterium (14). In the case of this patient, the infection was polymicrobial and the Clostridium spp. which were cultured may have contributed to the formation of intracranial gas.

Only small studies have investigated the outcome of intracranial infections with gas formation. Interestingly, the mortality due to these infections tends to be low, in contrast to that due to infections with gas formation elsewhere in the body. Prompt surgical intervention, nevertheless, appears to be essential in addition to antibiotic treatment. Overall mortality due to brain abscesses outside the developing world is still significant, around 10%, and in the developing world, it is estimated to be as high as 30% (3, 11).

Although C. glycolicum has been isolated from human wounds, peritoneal fluid, and feces (4), it was until recently unclear whether any pathogenic role could be ascribed to this microorganism. Recently, Elsayed and Zhang reported the isolation of C. glycolicum from blood cultures of a bone marrow transplant patient, implying clinical significance in an immunocompromised patient (5). The patient we describe was fully immunocompetent. The presence of clay, blocking the external auditory meatus, may have contributed to a local environment in which an otherwise nonpathogenic anaerobic microorganism could become pathogenic. The clay may also have been the source of the microorganism, as it is prevalent in soil (6), but unfortunately, the clay was not cultured.

The choice of home remedy of this patient prompted an Internet search on the use of clay for common ailments. We found a large number of alternative medicine websites (e.g., www.aboutclay.com, www.terrageena.com, and www.shirleys-wellness-cafe.com/clay.htm) promoting the use of clay; according to one such website, “With its large absorption capacity, clay binds toxins, cleans and vitalises therefore the body” (http://www.aromavera.nl/therapie.html).

In conclusion, Clostridium glycolicum may act as a copathogen in infections in immunocompetent individuals.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 24 December 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Couloigner, V., O. Sterkers, A. Redondo, and A. Rey. 1998. Brain abscesses of ear, nose, and throat origin: comparison between otogenic and sinogenic etiologies. Skull Base Surg. 8163-168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Louvois, J. 1980. Bacteriological examination of pus from abscesses of the central nervous system. J. Clin. Pathol. 3366-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Domingo, Z. 1994. Clostridial brain abscesses. Br. J. Neurosurg. 8691-694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drasar, B. S., P. Goddard, S. Heaton, S. Peach, and B. West. 1976. Clostridia isolated from faeces. J. Med. Microbiol. 963-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elsayed, S., and K. Zhang. 2007. Clostridium glycolicum bacteremia in a bone marrow transplant patient. J. Clin. Microbiol. 451652-1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaston, L. W., and E. R. Stadtman. 1963. Fermentation of ethylene glycol by Clostridium glycolicum, sp. n. J. Bacteriol. 85356-362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hakan, T., N. Ceran, I. Erdem, M. Z. Berkman, and P. Goktas. 2006. Bacterial brain abscesses: an evaluation of 96 cases. J. Infect. 52359-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Issaragrisil, R., W. Bhoopat, P. Khanjanasthiti, C. Dhiraputra, and S. Chitvanith. 1985. Gas-containing brain abscess due to Bacteroides corrodens: a case report. J. Med. Assoc. Thai. 68212-215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leskinen, K., and J. Jero. 2005. Acute complications of otitis media in adults. Clin. Otolaryngol. 30511-516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Odake, G. 1984. Gas-producing brain abscess due to peptostreptococcus. Neurol. Med. Chir. 2446-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paolini, S., G. Ralli, P. Ciappetta, and A. Raco. 2002. Gas-containing otogenic brain abscess. Surg. Neurol. 58271-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prasad, K. N., A. M. Mishra, D. Gupta, N. Husain, M. Husain, and R. K. Gupta. 2006. Analysis of microbial etiology and mortality in patients with brain abscess. J. Infect. 53221-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tada, M., Y. Toyoshima, H. Honda, N. Kojima, T. Yamamoto, K. Nishikura, and H. Takahashi. 2006. Multiple gas-forming brain microabscesses due to Klebsiella pneumoniae. Arch. Neurol. 63608-609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taguchi, Y., J. Sato, and N. Nakamura. 1981. Gas-containing brain abscess due to Fusobacterium nucleatum. Surg. Neurol. 16:408-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]