Abstract

Pantoea agglomerans and other Pantoea species cause infections in humans and are also pathogenic to plants, but the diversity of Pantoea strains and their possible association with hosts and disease remain poorly known, and identification of Pantoea species is difficult. We characterized 36 Pantoea strains, including 28 strains of diverse origins initially identified as P. agglomerans, by multilocus gene sequencing based on six protein-coding genes, by biochemical tests, and by antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Phylogenetic analysis and comparison with other species of Enterobacteriaceae revealed that the genus Pantoea is highly diverse. Most strains initially identified as P. agglomerans by use of API 20E strips belonged to a compact sequence cluster together with the type strain, but other strains belonged to diverse phylogenetic branches corresponding to other species of Pantoea or Enterobacteriaceae and to probable novel species. Biochemical characteristics such as fosfomycin resistance and utilization of d-tartrate could differentiate P. agglomerans from other Pantoea species. All 20 strains of P. agglomerans could be distinguished by multilocus sequence typing, revealing the very high discrimination power of this method for strain typing and population structure in this species, which is subdivided into two phylogenetic groups. PCR detection of the repA gene, associated with pathogenicity in plants, was positive in all clinical strains of P. agglomerans, suggesting that clinical and plant-associated strains do not form distinct populations. We provide a multilocus gene sequencing method that is a powerful tool for Pantoea species delineation and identification and for strain tracking.

The genus Pantoea includes several species that are generally associated with plants, either as epiphytes or as pathogens, and some species can cause disease in humans. Pantoea agglomerans, the Pantoea species most commonly isolated from humans, is widely distributed in nature and has been isolated from numerous ecological niches, including plants, water, soil, humans, and animals. It is frequently associated with plants as an epiphyte or an endophyte, and some isolates have been reported to be tumorogenic pathogens (20, 51). As an opportunistic human pathogen, P. agglomerans can occur sporadically or in outbreaks. At the beginning of the 1970s, P. agglomerans (then called Enterobacter agglomerans) was implicated in a large U.S. and Canadian outbreak of septicemia caused by contaminated closures on bottles of infusion fluids; 25 hospitals were involved, with 378 cases (34). Since then, P. agglomerans bacteremia has also been described in association with the contamination of intravenous fluid, parenteral nutrition, the anesthetic agent propofol, blood products, and transference tubes used for intravenous hydration (2-4, 22, 36). P. agglomerans has been recovered from joint fluids of patients with arthritis, synovitis, or osteomyelitis (7). Infection often occurs after injuries with plant thorns, wood slivers, or wooden splinters (7, 8, 16, 30, 40, 49). Cases of peritonitis due to P. agglomerans have also been reported (15, 31). Finally, P. agglomerans, which is known to colonize cotton and cotton plants heavily, is associated with cotton fever, a benign febrile syndrome seen in intravenous drug abusers (14).

Seven Pantoea species are currently distinguished: P. agglomerans, the type species of the genus; Pantoea ananatis; Pantoea stewartii (divided into the two subspecies Pantoea stewartii subsp. stewartii, the agent of Stewart's vascular wilt in maize and sweet corn, and Pantoea stewartii subsp. indologenes); Pantoea dispersa; Pantoea citrea; Pantoea punctata; and Pantoea terrea (18, 20, 28, 37). The Pantoea agglomerans complex was previously designated Erwinia herbicola or Enterobacter agglomerans (18). The biochemical heterogeneity of P. agglomerans and related strains and species renders identification difficult, even if several biochemical or nutritional characteristics distinguish the “Japanese group” (20) of Pantoea species (P. citrea, P. punctata, and P. terrea). Currently, confident identification is not achieved routinely.

Precise knowledge of the phylogenetic relationships and the degree of genetic distinctness among Pantoea species is a prerequisite for their correct identification. Phylogenetic relationships among Pantoea species were initially based on 16S rRNA analysis (24, 39, 53), which showed that P. agglomerans, P. ananatis, and P. stewartii were closely related. The same result was obtained based on the three protein-coding genes atpD, carA, and recA (53). However, only one or a few strains per species were analyzed, and the phylogenetic relationships of the three “Japanese” species with the other Pantoea species have, to our knowledge, never been described. Hence, it is not clear whether Pantoea species are clearly demarcated and if the genus Pantoea forms only one phylogenetic branch.

Defining bacterial species remains a challenge, especially given the fact that homologous recombination or lateral gene transfer can disturb species boundaries. Currently, the approach to defining bacterial species uses both genomic and phenotypic characteristics. The pragmatic values of 70% DNA-DNA reassociation and a difference of <5°C in the melting temperature have been proposed as a cutoff for species definition (50) but are technically challenging to obtain. Multilocus sequence analysis (MLSA) provides an alternative way to define species and to explore sequence discontinuities among them (19). Phylogenetic analysis of concatenated multiple protein-coding genes sometimes allow one to clearly separate species into sequence clusters that can be used to define species, even if borders may be fuzzy for highly recombinogenic species (17, 23). Moreover, the MLSA approach can be used to estimate homologous recombination among species, which is important for determining the reliability of molecular identification based on one or a few genes and for estimating the impact of homologous recombination or lateral gene transfer on the speciation process. So far, no MLSA approach has been reported for Pantoea species.

Strain typing and population genetics studies are necessary for epidemiological purposes and to identify strains with important phenotypes such as virulence to plants or humans (11, 47). For example, it is important to determine if P. agglomerans strains differ in their abilities to infect humans or to cause specific diseases in plants. Currently, P. agglomerans strains can be differentiated using fluorescent amplified fragment length polymorphism (5) or pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (51). However, these methods do not provide unambiguous definition of clones and clonal families, and the results are generally difficult to compare among laboratories. Currently, the amount of diversity within P. agglomerans and its population structure are unknown. A widely accepted method for studying strain relationships is multilocus sequence typing (MLST) (33). It consists of sequencing internal portions of several protein-coding genes. This method provides unambiguous and portable data and allows one to compare data worldwide, which is necessary in order to achieve a comprehensive overview of strain diversity and epidemiological distribution (32). In addition, this method is suitable for studying strain phylogeny and allows one to address evolutionary questions at the strain level within species (11). In contrast to MLSA, MLST relies on the comparison of allelic profiles of strains within species, whereas MLSA uses concatenation of gene sequences to define boundaries and phylogenetic relationships between species.

There are few data concerning the susceptibility of P. agglomerans to antimicrobial agents. In 1986, Muytjens et al. reported in vitro susceptibility data for eight species of Enterobacter, including 27 strains of E. agglomerans (38). The strains exhibited very variable susceptibilities to β-lactams, aminoglycosides, and quinolones. Hieng et al. (25) described a case of septicemia due to an Erwinia herbicola strain that was resistant to ampicillin, carbenicillin, and cephalothin (cefalotin) and susceptible to other antibiotics usually active on gram-negative bacilli. Cruz et al. (7) reported similar results. No β-lactamase was found among the Pantoea species. In 2000, a clinical isolate of P. agglomerans recovered from a patient with septic arthritis was reported to be highly resistant to fosfomycin (8).

The objectives of this study were (i) to define the phylogenetic relationships among P. agglomerans strains, or strains that may be misidentified as P. agglomerans, and other species of Enterobacteriaceae; (ii) to characterize Pantoea species or phylogenetic clusters biochemically and for their susceptibilities to antimicrobial agents; and (iii) to develop and evaluate MLST for strain discrimination and determination of the population structure of P. agglomerans.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

A total of 36 strains belonging to the genus Pantoea were used. A set of 28 strains initially identified as P. agglomerans were gathered from different microbiology laboratories (Tenon, Saint-Antoine, and Saint-Michel hospitals, Paris, France), from the collection of the Biodiversity of Emerging Bacterial Pathogens Unit (Institut Pasteur, Paris, France), and from the Collection de l'Institut Pasteur (CIP). These strains were mainly isolated from clinical samples (Table 1). Strains were identified using API 20E biochemical strips (bioMerieux SA, Marcy-l'Etoile, France), and eight of them were confirmed as P. agglomerans sensu stricto based on DNA-DNA hybridization results (6). Eight type strains, corresponding to described species and subspecies of the genus Pantoea, were included for comparison (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the strains used in this study

| Study code | Strain namea | Original designation | Original identification method | MLSA identification | Source | ST | repA PCR result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA13 | CIP102191 | P. agglomerans | API 20E | Enterobacter cowanii | Food | NCb | Negative |

| PA8 | CIP5549 | P. agglomerans | API 20E | Enterobacter cowanii | Growth medium contaminant | NC | Negative |

| PA1 | SM141 | P. agglomerans | API 20E | Pantoea agglomerans | Clinical, Paris, France (Saint-Michel Hospital), | 9 | Positive |

| PA11 | SA-BAM | P. agglomerans | API 20E | Pantoea agglomerans | Blood, Paris, France (Saint-Antoine Hospital) | 10 | Positive |

| PA12 | SA-CHA | P. agglomerans | API 20E | Pantoea agglomerans | Blood, Paris, France (Saint-Antoine Hospital) | 11 | Positive |

| PA14 | CIP102282 | P. agglomerans | API 20E | Pantoea agglomerans | Tobacco | 12 | Positive |

| PA17 | 36779 | P. agglomerans | API 20E | Pantoea agglomerans | Blood, Paris, France (Tenon Hospital) | 13 | Positive |

| PA18 | 2263 | P. agglomerans | API 20E | Pantoea agglomerans | Blood, Paris, France (Saint-Antoine Hospital) | 14 | Positive |

| PA7 | CIPA181 | P. agglomerans | API 20E | Pantoea agglomerans | Blood, France | 15 | Positive |

| PA9 | CIP82.100 | P. agglomerans | API 20E | Pantoea agglomerans | Cereal, Canada | 16 | Positive |

| PA3 | 4119 | P. agglomerans | API 20E | Pantoea agglomerans | Clinical, Paris, France (Saint-Michel Hospital) | 18 | Positive |

| PA4 | 26301 | P. agglomerans | API 20E | Pantoea agglomerans | Dialysis, Paris, France (Tenon Hospital) | 19 | Positive |

| SB545 | 04A450 | P. agglomerans | API 20 E | Pantoea agglomerans | Blood, Paris, France | 20 | Negative |

| SB4002 | 014230 | P. agglomerans | DNA-DNA hybridizationd | Pantoea agglomerans | BBPE collectionc | 2 | Positive |

| SB4003 | 2774-71 | P. agglomerans | DNA-DNA hybridization | Pantoea agglomerans | Leg wound, BBPE collection | 3 | Positive |

| SB4004 | 82-84 | P. agglomerans | DNA-DNA hybridization | Pantoea agglomerans | BBPE collection | 4 | Positive |

| SB4005 | 85-54 | P. agglomerans | DNA-DNA hybridization | Pantoea agglomerans | BBPE collection | 5 | Positive |

| SB4006 | CUETM85-53 | P. agglomerans | DNA-DNA hybridization | Pantoea agglomerans | Bean plant leaf | 6 | Positive |

| SB4008 | EL107 | P. agglomerans | DNA-DNA hybridization | Pantoea agglomerans | BBPE collection | 7 | Positive |

| SB4009 | ICPB EM102 | P. agglomerans | DNA-DNA hybridization | Pantoea agglomerans | Japan | 8 | Positive |

| SB4001 | 0103202 | P. agglomerans | DNA-DNA hybridization | Pantoea agglomerans | BBPE collection | 17 | Positive |

| SB3745 | CIP57.51T | P. agglomerans | Type strain | Pantoea agglomerans | Knee laceration | 1 | Positive |

| SB3686 | CIP105207T | Pantoea ananatis | Type strain | Pantoea ananatis | Ananas comosus, Brazil | NC | Negative |

| SB3620 | ATCC 31623T | Pantoea citrea | Type strain | Pantoea citrea | Unspecified | NC | Negative |

| PA16 | CIP102701 | P. agglomerans | API 20E | Pantoea dispersa | Human ear, Le Kremlin Bicêtre, France | NC | Positive |

| SB3687 | CIP105207T | Pantoea dispersa | Type strain | Pantoea dispersa | Ananas comosus, Brazil | NC | Negative |

| SB3621 | ATCC 31626T | Pantoea punctata | Type strain | Pantoea punctata | Mandarin (Citrus reticulata), Japan | NC | Negative |

| SB3640 | CIP104006T | Pantoea stewartii subsp. indologenes | Type strain | Pantoea stewartii subsp. indologenes | Millet, India | NC | Negative |

| SB3656 | CIP104005T | Pantoea stewartii subsp. stewartii | Type strain | Pantoea stewartii subsp. stewartii | Maize, United States | NC | Negative |

| SB3746 | CIP105600T | Pantoea terrea | Type strain | Pantoea terrea | Soil, Japan | NC | Negative |

| SB546 | 07A374 | P. agglomerans | API 20E | Single branch close to Enterobacter | Blood, Freiburg, Germany | NC | Negative |

| PA15 | CIP102343 | P. agglomerans | API 20E | Single branch close to Kluyvera genus | Human urine, Algeria | NC | Negative |

| PA5 | 6241 | P. agglomerans | API 20E | Single branch close to P. agglomerans | Blood, Paris, France (Saint-Michel Hospital) | 21 | Positive |

| SB547 | 12A277 | P. agglomerans | API 20E | Single branch close to P. agglomerans | Blood, Utrecht, The Netherlands | 22 | Negative |

| PA2 | 1618 | P. agglomerans | API 20E | Single branch close to Pantoea genus | Clinical, Paris, France (Saint-Michel Hospital) | NC | Negative |

| PA10 | CIP107083 | P. agglomerans | API 20E | Single branch close to Rahnella aquatilis | Beetroot (Beta vulgaris), Germany | NC | Negative |

ATCC, American Type Culture Collection; CUETM, Collection Unité EcoToxicologie Microbienne, Lille, France; ICPB, International Collection of Phytopathogenic Bacteria.

NC, not coded.

BBPE, Biodiversity of Emerging Bacterial Pathogens, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France.

All DNA-DNA hybridization data are from Brenner et al., 1984 (6).

Total-DNA extraction.

Bacterial strains were grown on tryptone-casein-soy agar for 24 h at 30°C. DNA was extracted using the Wizard genomic DNA purification kit (Promega, Madison, WI).

PCR amplifications and sequencing.

PCR amplification and sequencing of internal portions of the six housekeeping genes fusA, gyrB, leuS, pyrG, rplB, and rpoB were performed with the oligonucleotide primers given in Table 2, using the protocol described previously for Plesiomonas shigelloides (44). These genes were selected because they are single-copy-number genes, essential, and present in many bacterial lineages; therefore, they were expected to be present in all members of the Enterobacteriaceae. Primers for fusA, leuS, and pyrG were retrieved from Salerno et al. (44), and primers for gyrB, rplB, and rpoB were designed to amplify all species of the Enterobacteriaceae. The PCR cycles used for amplification are shown in Table 2. PCR products were directly sequenced after purification by ultrafiltration (Millipore, France) on both strands using the BigDye Terminator ready reaction kit (version 3.1; Perkin-Elmer). Purification was performed by ethanol precipitation. Sequence reaction products were analyzed using an ABI 3730XL automated DNA sequencer. 16S rRNA was amplified and sequenced under the same conditions using the primers and PCR cycles detailed in Table 2. The repA gene was amplified by PCR with the previously described primers Rep23220_5 and Rep25101_3 (51). This PCR was carried out using 30 cycles (30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 45°C, and 1 min at 72°C).

TABLE 2.

Primers and conditions used for amplification and sequencing

| Gene | Primer name | Primer sequence | Primer positions on coding sequences | PCR cycles | Template size (bp)a | Template position on the geneb | Template position on the E. coli K-12 genomeb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fusA | fusA3 | 5′-CAT CGG TAT CAG TGC KCA CAT CGA-3′ | 36-59 | 2 min 94°C; 1 min 94°C, 1 min 60°C, 1 min 72°C (10 cycles); 1 min 94°C, 1 min 50°C, 1 min 72°C (21 cycles); 5 min 72°C | 633 | 103-735 | 3471434-3470802 (RC) |

| fusA4 | 5′-CAG CAT CGC CTG AAC RCC TTT GTT-3′ | ||||||

| gyrB | gyrB3 | 5′-GCG TAA GCG CCC GGG TAT GTA-3′ | 57-77 | 2 min 94°C; 1 min 94°C, 1 min 60°C, 1 min 72°C (10 cycles); 1 min 94°C, 1 min 50°C, 1 min 72°C (21 cycles); 5 min s72°C | 417 | 256-672 | 3877887-3877471 (RC) |

| gyrB4 | 5′-CCG TCG ACG TCC GCA TCG GTC AT-3′ | 1488-1508 | |||||

| gyrB3i | 5′-AAC GCW ATC GAC GAA GC-3′ | 136-152 | Primers used only for sequencing | ||||

| gyrB4i | 5′-TGG AAV CCR TCR TTC CAC-3′ | 771-788 | |||||

| leuS | leuS3 | 5′-CAG ACC GTG CTG GCC AAC GAR CAR GT-3′ | 487-512 | 2 min 94°C; 1 min 94°C, 1 min 60°C, 1 min 72°C (10 cycles); 1 min 94°C, 1 min 50°C, 1 min 72°C (21 cycles); 5 min 72°C | 642 | 568-1209 | 673439-672798 (RC) |

| leuS4 | 5′-CGG CGC GCC CCA RTA RCG CT-3′ | 1274-1293 | |||||

| pyrG | pyrG3 | 5′-GGG GTC GTA TCC TCT CTG GGT AAA GG-3′ | 31-56 | 2 min 94°C; 1 min 94°C, 1 min 60°C, 1 min 72°C (10 cycles); 1 min 94°C, 1 min 50°C, 1 min 72°C (21 cycles); 5 min 72°C | 306 | 82-387 | 2907607-2907302 (RC) |

| pyrG4 | 5′-GGA ACG GCA GGG ATT CGA TAT CNC CKA-3′ | 434-460 | |||||

| rplB | rplB3 | 5′-CAG TTG TTG AAC GTC TTG AGT ACG ATC C-3′ | 227-254 | 2 min 94°C; 1 min 94°C, 1 min 60°C, 1 min 72°C (10 cycles); 1 min 94°C, 1 min 50°C, 1 min 72°C (21 cycles); 5 min 72°C | 333 | 304-636 | 3449083-3448751 (RC) |

| rplB4 | 5′-CAC CAC CAC CAT GYG GGT GRT C-3′ | 685-706 | |||||

| rpoB | Vic3 | 5′-GGC GAA ATG GCW GAG AAC CA-3′ | 1422-1442 | 4 min 94°C; 30 s 94°C, 30 s 50°C, 30 s 72°C (30 cycles); 5 min 72°C | 501 | 1657-2157 | 4180924-4181424 |

| Vic2 | 5′-GAG TCT TCG AAG TTG TAA CC-3′ | 2469-2489 | |||||

| 16S rRNA | Ad | 5′-AGA GTT TGA TCM TGG CTC AG-3′ | 8-27 | 4 min 94°C; 1 min 94°C, 1 min 49°C, 1 min 72°C (35 cycles); 7 min 72°C | |||

| rJ | 5′-GGT TAC CTT GTT ACG ACT T-3′ | 1492-1510 | |||||

| E | 5′-ATT AGA TAC CCT GGT AGT CC-3′ | 787-806 | Primers used only for sequencing | ||||

| rE | 5′-GGA CTA CCA GGG TAT CTA AT-3′ | 788-806 | |||||

| D | 5′-CAG CAG CCG CGG TAA TAC-3′ | 519-536 |

The template corresponds to the internal portion of the PCR product used for sequence comparison.

E. coli K-12 was taken as the reference (NCBI genome accession number NC_000913). RC, reverse complement.

Biochemical characteristics.

Biochemical tests were performed using the Biotype-100 system (BioMérieux, Marcy-L'Etoile, France) with Biotype medium 1. Positive tests were scored after observation of turbidity or color change following growth in single carbon sources after 48 h and 96 h of incubation at 30°C, according to the manufacturer's instructions. API 20E strips were used in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions (bioMérieux). The tests were all carried out at least in duplicate, and analytical index profiles were determined after 24 h and 48 h of incubation at 37°C. Identification was performed using the API 20E database (version 4.1) with the analytical profile index and with apiweb identification software.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

Antimicrobial susceptibility was determined by the disk diffusion method on Mueller-Hinton agar (Bio-Rad, Marnes la Coquette, France) according to the recommendations of the Comité de l'Antibiogramme de la Société Française de Microbiologie (CA-SFM) (http://www.sfm.asso.fr). The antibiotic disks (Bio-Rad) were as follows: amoxicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, ticarcillin, ticarcillin-clavulanic acid, piperacillin, piperacillin-tazobactam, cephalothin, cefoxitin, cefotaxime, ceftazidime, aztreonam, imipenem, gentamicin, tobramycin, netilmicin, amikacin, nalidixic acid, ofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, fosfomycin, and colistin. MICs of amoxicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, cephalothin, cefotaxime, and fosfomycin were determined by the standard agar dilution method according to the recommendations of the CA-SFM.

Data analysis.

Chromatogram traces were edited and analyzed using BioNumerics, version 5.10 (Applied Maths, Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium). Each base of the selected template region was confirmed by at least two chromatograms (forward and reverse); if there were ambiguities for a sequence, an additional sequence reaction was performed. Sequences were aligned with BioNumerics. The best model of nucleotide substitution was determined using the MODELTEST Web server (42). Maximum-likelihood trees and bootstrap values were calculated using PhyML (21) with the appropriate model of nucleotide substitution, and the proportion of invariable sites was estimated. Nucleotide diversity and level of polymorphism were calculated using DNAsp, version 4 (43). MLST data were analyzed by the standard MLST approach: for each gene, an allele number was attributed to each allelic variant, and the sequence type (ST) of a strain corresponded to the combination of the allele numbers of the six genes.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

All sequences of MLST genes are available on our publicly accessible MLST Web server (http://www.pasteur.fr/mlst). The rrs gene (coding for 16S rRNA) sequences were deposited in the GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ databases under accession numbers FJ357809 to FJ357836.

RESULTS

Phylogenetic relationships.

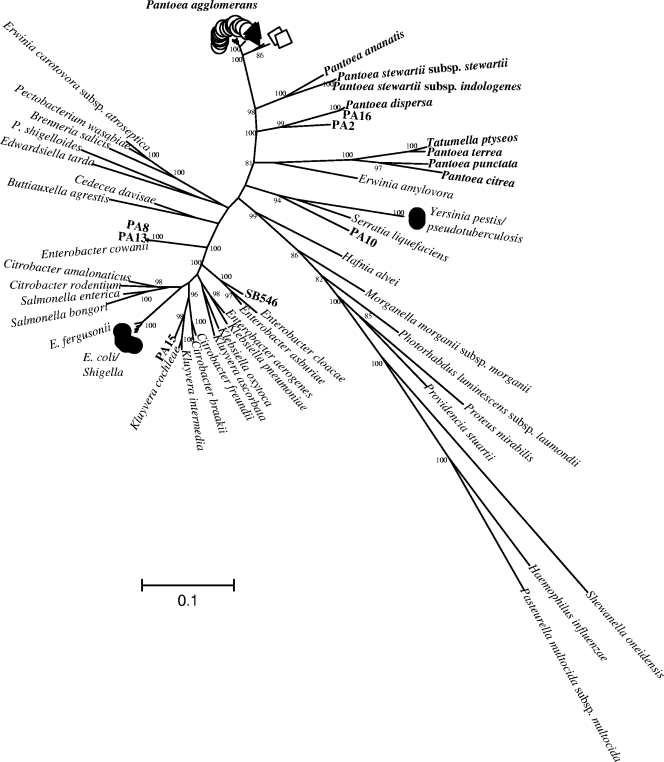

The sequences of internal portions of six protein-coding genes were obtained for the 36 study strains. Phylogenetic analysis of the aligned sequences showed that eight strains were highly divergent, showing less than 85% nucleotide similarity with the remaining strains. Comparison with a reference database containing the sequences of all type strains of Enterobacteriaceae showed that these eight strains were closely related to species external to the P. agglomerans cluster (Fig. 1). Two strains (PA8 and PA13) were very similar (>99.4%) to Enterobacter cowanii, whereas three other strains each formed a single branch close to Kluyvera intermedia and Kluyvera cochleae (PA15), a cluster of Enterobacter species including Enterobacter cloacae (SB546), or Serratia liquefaciens/Yersinia pseudotuberculosis (PA10). The three latter strains potentially represent new species. Finally, the type strains of P. terrea, P. punctata, and P. citrea clustered together with Tatumella ptyseos, indicating that these three Pantoea species should be reclassified as Tatumella.

FIG. 1.

Maximum-likelihood tree of 34 species of Enterobacteriaceae (each represented by its taxonomic type strain), the 36 Pantoea study strains, and 3 other gammaproteobacteria, constructed using the concatenated sequences of six loci (fusA, gyrB, leuS, pyrG, rplB, and rpoB). Sequences of the following strains were retrieved from the GenBank database: Yersinia pestis CO92 (accession no. NC_003143), Pasteurella multocida subsp. multocida Pm70 (NC_002663), Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 (NC_004347), and Haemophilus influenzae Rd KW20 (NC_000907). The numbers at the nodes are bootstrap values higher than 80%, obtained after 1,000 replicates.

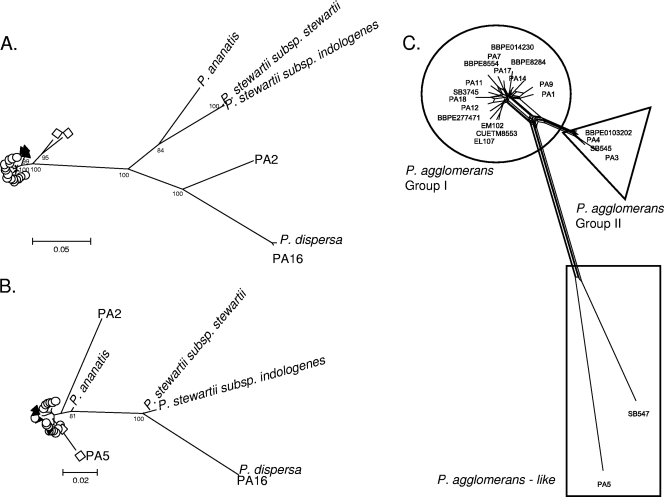

The remaining 28 strains had at least 86% similarity, on average, to each other and formed a unique branch relative to the type strains of other Enterobacteriaceae (Fig. 1). This branch included the type strain of P. agglomerans as well as those of the taxa P. stewartii subsp. stewartii, P. stewartii subsp. indologenes, P. ananatis, and P. dispersa. The phylogenetic relationships among the 28 strains were analyzed in detail. With minor exceptions, the individual gene phylogenies of the six protein-coding genes were congruent (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The phylogenies obtained based on the 2,832 bp of the concatenated sequence of the six genes (Fig. 2A) and on 1,491 aligned nucleotides of the 16S rRNA gene (Fig. 2B) are compared in Fig. 2. As expected, the protein-coding genes appeared to evolve much faster than the 16S rRNA gene: the numbers of phylogenetically informative sites were 420 (47.8%) for the concatenate and 46 (3.1%) for 16S rRNA, resulting in increased robustness of the nodes based on protein-coding genes. The minimal similarities observed between two sequences were 86.1% (concatenate) and 95.6% (16S rRNA). Twenty isolates, including the P. agglomerans type strain, grouped in a tight cluster with >99% similarity between any pair of strains. Two additional strains, SB547 and PA5, diverged from this P. agglomerans cluster by 3.8% and 4.4%, respectively. The taxonomic status of the 2 latter strains is therefore unclear, whereas the 19 isolates that formed a tight cluster with the type strain of P. agglomerans can clearly be considered P. agglomerans. P. ananatis and the two subspecies of P. stewartii were associated based on the concatenate (Fig. 2A), whereas P. ananatis clustered closer to P. agglomerans based on 16S rRNA (Fig. 2B). Finally, strain PA16 was closely related (99.4%) to the type strain of P. dispersa and may be identified as belonging this species, whereas strain PA2 formed a unique branch loosely related (89.3%) to P. dispersa. Strain PA2 may therefore represent a new species.

FIG. 2.

(A and B) Maximum-likelihood trees of 28 strains of Pantoea agglomerans and closely related species, constructed using concatenated sequences of six protein-coding genes (fusA, gyrB, leuS, pyrG, rplB, and rpoB) (A) and 16S rRNA sequences (B) based on the general time-reversible model of nucleotide substitution, which was inferred to be the most likely using MODELTEST. (C) Split decomposition analysis tree of the 20 strains of P. agglomerans and 2 P. agglomerans-like strains. Circles and triangles represent P. agglomerans groups I and II, respectively. The two P. agglomerans-like strains, PA5 and SB547, are in the rectangle. The numbers at the nodes are bootstrap values higher than 80%, obtained after 1,000 replicates.

Biochemical characterization.

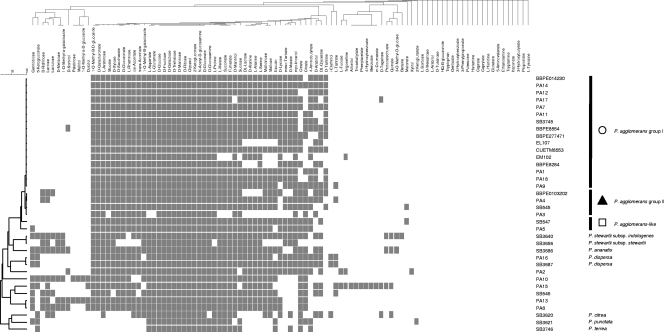

In order to assess whether biochemical characteristics can discriminate among species and the phylogenetic clusters identified above, the 36 study strains were characterized biochemically by two systems, API 20E and Biotype-100 strips. Biotype-100 strips test for the ability of strains to grow on 99 carbon sources in minimal medium. Biotype-100 analysis yielded results remarkably consistent with phylogenetic clustering, and some carbon sources distinguished the phylogenetic branches (Fig. 3). In particular, strains of P. agglomerans were the only ones to utilize d-tartrate (75% of strains); myo-inositol was used only by P. agglomerans, P. agglomerans-like strains, and the most closely related species (P. stewartii, P. ananatis, and P. dispersa); and meso-tartrate was used by the same group (85% of P. agglomerans strains) except for P. ananatis. The three divergent Pantoea type strains (P. citrea, P. punctata, and P. terrea) did not use a number of substrates, e.g., 1-O-methyl-β-d-glucoside and d-galacturonate, which were used by 100% of the other strains. Strain PA15, which clustered in a unique branch based on gene sequences, was unique in its ability to utilize six carbon sources (Fig. 3, adonitol to m-coumarate).

FIG. 3.

Biotype-100 results for the 36 strains used in the study. The tree on the left corresponds to a dendrogram, obtained by the unweighted-pair group method using average linkages, based on the concatenated sequences of six protein-coding genes (fusA, gyrB, leuS, pyrG, rplB, and rpoB) for the 36 strains. The tree at the top corresponds to the dendrogram, obtained by the unweighted-pair group method using average linkages, of 99 carbon sources clustered based on Dice similarity. A gray square means that the strain is able to utilize the substrate, whereas an empty square means that the strain is not able to grow on this carbon source after 48 h of incubation.

Based on API 20E tests, all isolates were typical of the genus Pantoea: they were urease negative; lysine and ornithine were not decarboxylated; and H2S was not produced from thiosulfate. All strains used glucose, mannitol, rhamnose, saccharose, arabinose, and amygdalin as substrates. The variable characteristics are reported in Table 3. Most isolates of P. agglomerans produced a yellow pigment on Trypticase soy medium (14/19) and were Voges-Proskauer positive (16/19). Comparison with the phenotypic characteristics of other type strains tested (P. dispersa, P. ananatis, and P. stewartii) showed few differences. Notably, only P. ananatis and P. stewartii were positive for indole production. The two undefined strains SB547 and PA5 shared the unique characteristic of being arginine dihydrolase positive.

TABLE 3.

Phenotypic characteristics of Pantoea agglomerans strains and related strains

| Characteristic | Resulta for:

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19 P. agglomerans strainsb | P. agglomerans CIP57.51T | SB547 | PA5 | PA2 | PA16 | P. dispersa CIP103338 | P. ananatis CIP105207 | P. stewartii CIP104006 | P. citrea | P. punctata | P. terrea | T. ptyseos | |

| Yellow pigment | 14/19 | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | ||||

| Indole production | 0/19 | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| Arginine dihydrolase | 0/21 | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | + |

| Voges−Proskauer | 16/19 | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + |

| Gelatin hydrolysis | 19/19c | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Production of acid from: | |||||||||||||

| Inositol | 0/19 (7/19)d | + | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| Melibiose | 6/19 | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| Fosfomycin susceptibilitye | 0/19 | R | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S |

Results are given as positive (+), negative (−), resistant (R), or susceptible (S) for individual strains. For the 19 P. agglomerans strains, results are given as the number of strains with the characteristic/total number of strains tested.

Strains PA1, PA3, PA4, PA7, PA9, PA11, PA12, PA14, PA17, PA18, SB4001, SB4002, SB4003, SB4004, SB4005, SB4006, SB4008, SB4009, and SB545.

Gelatin hydrolysis positive in 48 h.

Inositol positive in 48 h.

Determined by the disk diffusion method.

According to the API 20E system database, it was not possible to identify any isolate at the species level. However, the current database includes only Pantoea sp1, sp2, sp3, and sp4 (synonyms of Enterobacter agglomerans groups 1, 2, 3, and 4). The 19 isolates of P. agglomerans were divided into three different numerical codes: 1005173 (8 strains), 1005133 (8 strains), and 1004133 (3 strains), which corresponded, respectively, to Pantoea sp3 with 68% confidence, to Pantoea sp3 with 99.2% confidence, and to Pantoea sp4 with 64% confidence. With the addition of gelatin hydrolysis, which was positive in 48 h for all 19 isolates, these 19 isolates were identified as Pantoea sp3 with, respectively, 95%, 99.8%, and 96.4% confidence. Isolate PA16 was identified as Pantoea sp2 with only 43% confidence (code 0205173).

Antibiotic susceptibility.

All strains of P. agglomerans were uniformly susceptible to aminoglycosides (gentamicin, tobramycin, amikacin), fluoroquinolones (ofloxacin, ciprofloxacin), and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. All strains were fully susceptible to broad-spectrum cephalosporins and imipenem. Testing for susceptibility to other β-lactams showed various results (Table 4): nine P. agglomerans strains were susceptible to all β-lactams; six strains showed intermediate susceptibility or resistance to amoxicillin; and four strains showed intermediate susceptibility or resistance to cephalothin. Isolates SB547 and PA5 were susceptible to all antibiotics. Strain PA16 and the type strains of P. dispersa and P. stewartii were resistant to cephalothin, and the type strain of P. ananatis was resistant to amoxicillin.

TABLE 4.

MICs of several β-lactams

| Species or strain(s) | MIC (mg/liter) of the following β-lactam (breakpoints)a:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amx (4-16) | Amx-CA (4/2-16/2) | Cf (1-32) | Ctx (4-32) | |

| P. agglomerans (n = 20) | 1->128 | 0.125-2 | 1-32 | <0.06-0.25 |

| SB547 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0.125 |

| PA5 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.25 |

| P16, P. dispersa, P. stewartii | 1-2 | 1-2 | 16-32 | 0.25 |

| P. ananatis | 64 | 2 | 1 | 0.125 |

Amx, amoxicillin; Amx-CA, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid; Cf, cephalothin; Ctx, cefotaxime. Breakpoints are from the CA-SFM.

Remarkably, resistance to fosfomycin (MICs, >32 mg/liter) was observed for all P. agglomerans strains but for no other species, and may thus provide a useful and simple test for presumptive identification. In particular, isolates SB547 and PA5, which are closely related to P. agglomerans based on housekeeping gene sequences, were susceptible to fosfomycin.

MLST discriminates P. agglomerans isolates.

For the 20 P. agglomerans strains and isolates SB547 and PA5, the number of distinct alleles ranged from 4 for rplB to 17 for leuS (Table 5). Remarkably, each strain had a unique ST, showing that MLST is very discriminatory among P. agglomerans strains.

TABLE 5.

Diversity of six housekeeping genes among 20 Pantoea agglomerans and 2 P. agglomerans-like strainsa

| Gene | Template size (bp) | No. of alleles | No. (%) of polymorphic sites | π | No. of parsimony informative sites | No. of synonymous changes | No. of nonsynonymous changes | Ks | Ka | Ks/Ka |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fusA | 633 | 12 | 19 (3) | 0.00646 | 9 | 17 | 4 | 0.02269 | 0.00194 | 11.7 |

| gyrB | 417 | 15 | 39 (9.4) | 0.01587 | 15 | 36 | 5 | 0.06244 | 0.0016 | 39.0 |

| leuS | 642 | 17 | 91 (14.2) | 0.02617 | 53 | 86 | 7 | 0.11934 | 0.00387 | 30.8 |

| pyrG | 306 | 9 | 16 (5.2) | 0.00633 | 4 | 16 | 0 | 0.02712 | 0 | NA |

| rplB | 333 | 4 | 10 (3.0) | 0.00273 | 1 | 9 | 1 | 0.0096 | 0.00034 | 28.2 |

| rpoB | 501 | 13 | 30 (6.0) | 0.00912 | 15 | 32 | 0 | 0.03836 | 0 | NA |

| Concatenate | 2,832 | 22 | 205 (7.2) | 0.01233 | 97 | 196 | 17 | 0.04887 | 0.0016 | 30.5 |

π, average number of nucleotide differences per site for two randomly selected strains; Ks, number of synonymous changes per synonymous site; Ka, number of nonsynonymous changes per nonsynonymous site; NA, not applicable.

The levels of nucleotide diversity differed greatly among genes (Table 5). The percentage of polymorphic sites ranged from 3% for fusA and rplB to 14% for leuS, while the average number of nucleotide differences per site (π) ranged from 0.3% to 2.6% for rplB and leuS, respectively. Thus, P. agglomerans contains relatively large numbers of nucleotide polymorphisms among orthologous genes, even based on this limited strain sample. No nonsynonymous changes were found in pyrG and rpoB, and the ratio of synonymous to nonsynonymous changes (Ks/Ka) was higher than 11 for the other genes, consistent with selection against amino acid changes in housekeeping genes.

For microevolutionary studies, phylogenetic relationships among strains using MLST data are typically deduced based on allelic profiles rather than nucleotide sequences, since the former approach is less sensitive to recombination (11). Among P. agglomerans isolates, most STs were distant by at least three allelic mismatches, with only two pairs of STs (ST11-ST12 and ST17-ST19) differing by two genes. Thus, it was difficult, based on this restricted sample, to identify groups of closely related STs that could correspond to clonal families.

The phylogenetic structure of P. agglomerans was investigated by analysis of nucleotide sequences using SplitsTree (Fig. 2C). This analysis revealed the existence of a cluster of four strains (group II), which was demarcated from the remaining 16 P. agglomerans strains, including the type strain (group I). This cluster was also recovered by maximum-likelihood (Fig. 2A) and neighbor-joining (data not shown) phylogenetic reconstructions, as well as from most individual gene phylogenies (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Therefore, two phylogenetic groups can be distinguished within P. agglomerans. Three of four isolates of group II did not utilize d-lyxose, whereas all group I strains except one were positive for this carbon source. Of note, the 16S rRNA gene sequence did not allow separation between the two groups due to its limited amount of polymorphism (Fig. 2B).

Plasmid pPATH is associated with the virulence of P. agglomerans for plants (35), and P. agglomerans strains differ by the presence of this plasmid (51). Currently, the link between plant strains and human clinical isolates is not known. In order to determine the presence or absence of plasmid pPATH among our strains, we performed a PCR assay (51) that targets the repA gene, which codes for the replicase protein A of plasmid pPATH. It appeared that all P. agglomerans strains were positive by repA PCR, except for strain SB545 of group II. Of the two P. agglomerans-like strains SB547 and PA5, the former was negative and the latter was positive. All non-P. agglomerans strains were negative except for strain PA16 (identified as P. dispersa), which was positive and may have acquired plasmid pPATH horizontally. These results provide no evidence that P. agglomerans clinical strains represent a population distinct from plant-pathogenic strains.

DISCUSSION

Universal genes for phylogeny and species borders in Enterobacteriaceae.

In this work, we have developed and applied multilocus gene sequencing with the combined purposes of determining the phylogenetic relationships among Pantoea species and species borders using a MLSA approach and evaluating the usefulness of MLST for P. agglomerans strain typing. The primers used here were designed to be applicable to Enterobacteriaceae strains of all genera and species and allowed us to successfully amplify and sequence the six genes in species belonging to many genera (Fig. 1). Because this set of genes provides much better resolution than the traditionally used 16S rRNA gene, and because the 16S rRNA gene is not reliable for phylogeny in Enterobacteriaceae (39), this set of six protein-coding genes should be useful for future phylogenetic studies of species of Enterobacteriaceae.

The six genes fusA, gyrB, leuS, pyrG, rplB, and rpoB were successfully PCR amplified and sequenced for a collection of 36 strains initially identified as belonging to the Pantoea genus. The phylogenetic tree based on the concatenated sequences of the six housekeeping genes confirms that the genus Pantoea is heterogeneous. Pantoea species did not group in a single branch but instead were divided into two clusters. One cluster contained the type species of the genus (P. agglomerans), together with P. ananatis, P. dispersa, and P. stewartii. The second cluster contained the species P. citrea, P. terrea, and P. punctata, described by Kageyama et al. (28), which were strongly associated with the type strain of Tatumella ptyseos. These results indicate a necessity to revise the taxonomic status of these three species, as was suggested by Grimont and Grimont based on the distinct phenotypic characteristics of the “Japanese” group of Pantoea species (20), which possibly should be reclassified as belonging to the genus Tatumella.

Within the first cluster, P. agglomerans was clearly demarcated from the other species. Indeed, the 19 isolates and the type strain formed a tight cluster with less than 1.5% divergence on average for the six protein-coding genes, while these strains were separated by more than 7% divergence from P. ananatis and P. stewartii. Therefore, there appears to be no ambiguity in the distinctness of these species based on the present set of strains. In contrast, the two strains SB547 and PA5 showed an intermediate average distance from P. agglomerans strains. However, individual gene phylogenies of the six genes do not show the same picture, especially for fusA, on the basis of which the two strains clustered inside P. agglomerans (group II) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Some strains can have intermediate positions on phylogenetic trees deduced from concatenated sequences, in particular due to horizontal transfer occurring independently on individual genes, providing conflicting phylogenetic signals. These strains result in unclear demarcation of species, and this difficulty in separating species has led to the concept of “fuzzy species” (23). SB547 and PA5 potentially represent examples of strains that have received DNA sequences from external species, leading to their apparent separation from P. agglomerans. Alternatively, they may represent a distinct species that has received some genes (in particular, fusA) from P. agglomerans. This phenomenon makes it difficult to decide, based on the present data, whether the two strains SB547 and PA5 belong to P. agglomerans or to a closely related species. In contrast, PA2 clearly represents a species distinct from all currently described Pantoea species, since its uniqueness is supported by all individual gene phylogenies.

It may be noted that the position of P. ananatis relative to P. agglomerans and P. stewartii in the concatenate tree (Fig. 2A) was different from that in the 16S rRNA tree (Fig. 2B). This difference was also apparent in a previous study where 16S rRNA and protein-coding genes were analyzed (53). The plot of the distance based on 16S rRNA versus the distance based on the concatenated sequence showed a strong correlation, with most comparisons fitting on a single line, but P. ananatis stood as an outlier, with an atypically high 16S rRNA similarity (data not shown). Therefore, one may suspect that the 16S rRNA gene underwent horizontal transfer between P. agglomerans and P. ananatis. Based on individual gene phylogenies (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), five of our six genes, as well as the atpD and carA genes (53), grouped P. ananatis with P. stewartii, while fusA grouped P. ananatis with P. agglomerans. Thus, fusA may also have been imported from P. agglomerans into P. ananatis. Finally, we noted that for both subspecies of P. stewartii, the 5′ portion of the 16S rRNA sequence was divergent from those of P. agglomerans and P. ananatis, with 8 single-nucleotide polymorphisms within 92 nucleotide positions (8.7%), whereas the average divergence over the entire length of the rRNA gene was 2.7%. This observation suggests that the 16S rRNA gene of P. stewartii may have a mosaic origin.

Overall, these results illustrate the importance of using multiple independent gene sequences, since they provide much-improved phylogenetic information over that obtained with the 16S rRNA gene. In addition, as proposed in the MLSA approach (23), the use of multiple genes allows one to buffer the effect of horizontal transfer on phylogenies and to be better informed on the validity of assigning strains to species.

Identification tools.

Biochemical tests are broadly used for strain identification in clinical laboratories. Our results show that strains identified as P. agglomerans by widely used biochemical methods represent a diverse set of strains encompassing several unrelated phylogenetic branches. A majority of isolates initially identified as P. agglomerans clustered in a compact group together with the type strain and can be considered as belonging to the species P. agglomerans. Nevertheless, the API 20E method led to the misidentification of a few strains (SB546, PA2, PA8, PA10, PA13, PA15, and PA16), since phylogenetic analysis revealed that they did not belong to P. agglomerans. Thus, multilocus sequencing of protein-coding genes stands as a useful reference tool for the identification of P. agglomerans and for the characterization of atypical strains.

Even though biochemical identification used routinely can be imprecise, the Biotype-100 results were consistent with the phylogeny, and some characteristics appear to be potentially useful and can provide an orientation for strain identification, since they are specific to particular phylogenetic clusters. For example, d-tartrate was used only by P. agglomerans, whereas myo-inositol and meso-tartrate were used only by P. agglomerans and closely related Pantoea species; these results are consistent with previous data (20). Likewise, resistance to fosfomycin was found to be very useful for the identification of P. agglomerans.

Toward a universal MLST scheme for Enterobacteriaceae?

Strain typing is an important tool for detecting the source of infections in epidemiological investigations (48). In addition, the possible association between ecology or virulence and particular P. agglomerans clones is currently unknown, and future research into these important questions would benefit greatly from a standard definition of strains. MLST is now widely recognized as a powerful approach for defining groups of related strains (clones), for determining the geographic and temporal distribution of clones, and for revealing the internal genetic structure of species. Until now, MLST developments have been restricted to a few species of the Enterobacteriaceae (1, 9, 29, 52), because it remains difficult to design successful PCR primers for sequencing of protein-coding genes, especially when no genome sequence is available. In addition, because different gene sets are used for different species, and because distinct genes have distinct evolutionary rates, direct comparison of amounts of diversity and population genetics parameters among species is not possible.

We successfully developed an MLST scheme for Pantoea species in the absence of a complete genome sequence for Pantoea by designing broad-range primers based on universally conserved protein-coding genes. Our data show that MLST is a powerful typing tool for P. agglomerans, since each of the 20 isolates had a distinct multilocus genotype (allelic profile). This result was not necessarily expected, since the use of broadly distributed genes could have implied a low evolutionary rate and hence low discrimination. Together with previous results for Plesiomonas shigelloides (44) and Enterobacter cloacae (41), which also showed high discrimination among strains, the present study therefore indicates that our set of broad-range primers could represent a universal MLST scheme applicable to most, if not all, species of the Enterobacteriaceae.

Population structure of P. agglomerans.

Bacterial species differ widely in the rate of homologous recombination among strains (13, 45). Determining the frequency of recombination is important for understanding the evolution of bacterial pathogens and for the interpretation of typing data (46). Given the relatively small sample and the restricted degree of nucleotide polymorphism, it was not possible to determine the rate of recombination precisely and to demonstrate its occurrence statistically. However, two lines of evidence indicate that recombination is not rare among P. agglomerans strains. First, the distribution of nucleotide polymorphisms along the individual phylogenies of the three most informative genes (gyrB, leuS, and rpoB) showed homoplasy, which is likely to result from the occurrence of intragenic recombination in these genes. Second, split decomposition analysis of the concatenated sequences of the six genes showed a network-like structure (Fig. 2C). Typically, networks disclosed upon split decomposition analysis are interpreted as evidence for recombination (26), since they incorporate the effects of both intragenic and intergenic recombination. This analysis, therefore, suggests relatively frequent homologous recombination among P. agglomerans strains. This species, therefore, represents another example of a recombining species within the family Enterobacteriacae, following the previous demonstration of high rates of recombination in P. shigelloides (44) and moderate recombination in Escherichia coli (12, 52) and Salmonella enterica (10).

Despite evidence for homologous recombination among housekeeping genes, an internal phylogenetic structure could be revealed for P. agglomerans. Indeed, we consistently found two groups of strains that were recovered by different analyses and genes. The existence of an internal phylogenetic structure in the presence of recombination is reminiscent of the situation of E. coli, where at least six clearly separated groups are distinguished (27). In addition, utilization of d-lyxose appeared to distinguish P. agglomerans groups I and II, although this finding should be confirmed with additional strains. There was no association in our limited sample between the groups and the source of isolates, but the study of larger strain collections of diverse origins, including plant-pathogenic isolates and environmental isolates, may reveal associations between phenotypes and multilocus genotypes. In order to provide a common language for P. agglomerans strain characterization and evolution, a publicly available MLST website was set up at http://www.pasteur.fr/mlst.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Bizet (Collection de l'Institut Pasteur) for providing type strains, T. Lambert (Saint-Michel Hospital) for providing clinical strains, and J.-C. Petit for support.

A.D. was partially financed by a generous gift from the Conny-Maeva Charitable Foundation.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 3 December 2008.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jcm.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Achtman, M., K. Zurth, G. Morelli, G. Torrea, A. Guiyoule, and E. Carniel. 1999. Yersinia pestis, the cause of plague, is a recently emerged clone of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9614043-14048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvarez, F. E., K. J. Rogge, J. Tarrand, and B. Lichtiger. 1995. Bacterial contamination of cellular blood components. A retrospective review at a large cancer center. Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 25283-290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett, S. N., M. M. McNeil, L. A. Bland, M. J. Arduino, M. E. Villarino, D. M. Perrotta, D. R. Burwen, S. F. Welbel, D. A. Pegues, L. Stroud, et al. 1995. Postoperative infections traced to contamination of an intravenous anesthetic, propofol. N. Engl. J. Med. 333147-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bicudo, E. L., V. O. Macedo, M. A. Carrara, F. F. Castro, and R. I. Rage. 2007. Nosocomial outbreak of Pantoea agglomerans in a pediatric urgent care center. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 11281-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brady, C., S. Venter, I. Cleenwerck, M. Vancanneyt, J. Swings, and T. Coutinho. 2007. A FAFLP system for the improved identification of plant-pathogenic and plant-associated species of the genus Pantoea. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 30413-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brenner, D. J., G. R. Fanning, J. K. Leete Knutson, A. G. Steigerwalt, and M. I. Krichevsky. 1984. Attempts to classify Herbicola group-Enterobacter agglomerans strains by deoxyribonucleic acid hybridization and phenotypic tests. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 3445-55. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cruz, A. T., A. C. Cazacu, and C. H. Allen. 2007. Pantoea agglomerans, a plant pathogen causing human disease. J. Clin. Microbiol. 451989-1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Champs, C., S. Le Seaux, J. J. Dubost, S. Boisgard, B. Sauvezie, and J. Sirot. 2000. Isolation of Pantoea agglomerans in two cases of septic monoarthritis after plant thorn and wood sliver injuries. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38460-461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diancourt, L., V. Passet, J. Verhoef, P. A. D. Grimont, and S. Brisse. 2005. Multilocus sequence typing of Klebsiella pneumoniae nosocomial isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 434178-4182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Falush, D., M. Torpdahl, X. Didelot, D. F. Conrad, D. J. Wilson, and M. Achtman. 2006. Mismatch induced speciation in Salmonella: model and data. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 3612045-2053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feil, E. J. 2004. Small change: keeping pace with microevolution. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2483-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feil, E. J., E. C. Holmes, D. E. Bessen, M. S. Chan, N. P. Day, M. C. Enright, R. Goldstein, D. W. Hood, A. Kalia, C. E. Moore, J. Zhou, and B. G. Spratt. 2001. Recombination within natural populations of pathogenic bacteria: short-term empirical estimates and long-term phylogenetic consequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98182-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feil, E. J., and B. G. Spratt. 2001. Recombination and the population structures of bacterial pathogens. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 55561-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferguson, R., C. Feeney, and V. A. Chirurgi. 1993. Enterobacter agglomerans-associated cotton fever. Arch. Intern. Med. 1532381-2382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferrantino, M., S. D. Navaneethan, and J. A. Sloand. 2008. Pantoea agglomerans: an unusual inciting agent in peritonitis. Perit. Dial. Int. 28428-430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flatauer, F. E., and M. A. Khan. 1978. Septic arthritis caused by Enterobacter agglomerans. Arch. Intern. Med. 138788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fraser, C., W. P. Hanage, and B. G. Spratt. 2007. Recombination and the nature of bacterial speciation. Science 315476-480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gavini, F., J. Mergaert, A. Beji, C. Mielcarek, D. Izard, K. Kersters, and J. De Ley. 1989. Transfer of Enterobacter agglomerans (Beijerinck 1888) Ewing and Fife 1972 to Pantoea gen. nov. as Pantoea agglomerans comb. nov. and description of Pantoea dispersa sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 39337-345. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gevers, D., F. M. Cohan, J. G. Lawrence, B. G. Spratt, T. Coenye, E. J. Feil, E. Stackebrandt, Y. Van de Peer, P. Vandamme, F. L. Thompson, and J. Swings. 2005. Re-evaluating prokaryotic species. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3733-739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grimont, P. A. D., and F. Grimont. 2005. Genus Pantoea, p. 713-720. In D. J. Brenner, N. R. Krieg, and J. T. Staley (ed.), Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology, 2nd ed., vol. 2. The Proteobacteria. Springer-Verlag, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guindon, S., and O. Gascuel. 2003. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst. Biol. 52696-704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Habsah, H., M. Zeehaida, H. Van Rostenberghe, R. Noraida, W. I. Wan Pauzi, I. Fatimah, A. R. Rosliza, N. Y. Nik Sharimah, and H. Maimunah. 2005. An outbreak of Pantoea spp. in a neonatal intensive care unit secondary to contaminated parenteral nutrition. J. Hosp. Infect. 61213-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanage, W. P., C. Fraser, and B. G. Spratt. 2005. Fuzzy species among recombinogenic bacteria. BMC Biol. 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hauben, L., E. R. Moore, L. Vauterin, M. Steenackers, J. Mergaert, L. Verdonck, and J. Swings. 1998. Phylogenetic position of phytopathogens within the Enterobacteriaceae. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 21384-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hieng, H., C. Richard, J. Marie, and Y. Lemennais. 1989. A propos d'un cas de septicémie à Erwinia herbicola. Med. Mal. Infect. 19193-195. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huson, D. H., and D. Bryant. 2006. Application of phylogenetic networks in evolutionary studies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 23254-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jaureguy, F., L. Landraud, V. Passet, L. Diancourt, E. Frapy, G. Guigon, E. Carbonnelle, O. Lortholary, O. Clermont, E. Denamur, B. Picard, X. Nassif, and S. Brisse. 26 November 2008, posting date. Phylogenetic and genomic diversity of human bacteremic Escherichia coli strains. BMC Genomics 9560. [Epub ahead of print.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kageyama, B., M. Nakae, S. Yagi, and T. Sonoyama. 1992. Pantoea punctata sp. nov., Pantoea citrea sp. nov., and Pantoea terrea sp. nov. isolated from fruit and soil samples. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 42203-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kidgell, C., U. Reichard, J. Wain, B. Linz, M. Torpdahl, G. Dougan, and M. Achtman. 2002. Salmonella typhi, the causative agent of typhoid fever, is approximately 50,000 years old. Infect. Genet. Evol. 239-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kratz, A., D. Greenberg, Y. Barki, E. Cohen, and M. Lifshitz. 2003. Pantoea agglomerans as a cause of septic arthritis after palm tree thorn injury; case report and literature review. Arch. Dis. Child. 88542-544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lim, P. S., S. L. Chen, C. Y. Tsai, and M. A. Pai. 2006. Pantoea peritonitis in a patient receiving chronic ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Nephrology (Carlton) 1197-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maiden, M. C. 2006. Multilocus sequence typing of bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 60561-588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maiden, M. C., J. A. Bygraves, E. Feil, G. Morelli, J. E. Russell, R. Urwin, Q. Zhang, J. Zhou, K. Zurth, D. A. Caugant, I. M. Feavers, M. Achtman, and B. G. Spratt. 1998. Multilocus sequence typing: a portable approach to the identification of clones within populations of pathogenic microorganisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 953140-3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maki, D. G., F. S. Rhame, D. C. Mackel, and J. V. Bennett. 1976. Nationwide epidemic of septicemia caused by contaminated intravenous products. I. Epidemiologic and clinical features. Am. J. Med. 60471-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manulis, S., Y. Gafni, E. Clark, D. Zutra, Y. Ophir, and I. Barash. 1991. Identification of a plasmid DNA probe for detection of strains of Erwinia herbicola pathogenic on Gypsophila paniculata. Phytopathology 8154-57. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matsaniotis, N. S., V. P. Syriopoulou, M. C. Theodoridou, K. G. Tzanetou, and G. I. Mostrou. 1984. Enterobacter sepsis in infants and children due to contaminated intravenous fluids. Infect. Control 5471-477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mergaert, J., L. Verdonck, and K. Kersters. 1993. Transfer of Erwinia ananas (synomym, Erwinia uredovora) and Erwinia stewartii to the genus Pantoea emend. as Pantoea ananas (Serrano 1928) comb. nov., and Pantoea stewartii (Smith 1898) comb. nov., respectively, and description of Pantoea stewartii subsp. indologenes subsp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 43162-173. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Muytjens, H. L., and J. van der Ros-van de Repe. 1986. Comparative in vitro susceptibilities of eight Enterobacter species, with special reference to Enterobacter sakazakii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 29367-370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Naum, M., E. W. Brown, and R. J. Mason-Gamer. 2008. Is 16S rDNA a reliable phylogenetic marker to characterize relationships below the family level in the Enterobacteriaceae? J. Mol. Evol. 66630-642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Olenginski, T. P., D. C. Bush, and T. M. Harrington. 1991. Plant thorn synovitis: an uncommon cause of monoarthritis. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2140-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paauw, A., M. P. Caspers, F. H. Schuren, M. A. Leverstein-van Hall, A. Deletoile, R. C. Montijn, J. Verhoef, and A. C. Fluit. 2008. Genomic diversity within the Enterobacter cloacae complex. PLoS ONE 3e3018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Posada, D. 2006. ModelTest server: a Web-based tool for the statistical selection of models of nucleotide substitution online. Nucleic Acids Res. 34W700-W703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rozas, J., J. C. Sanchez-DelBarrio, X. Messeguer, and R. Rozas. 2003. DnaSP, DNA polymorphism analyses by the coalescent and other methods. Bioinformatics 192496-2497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Salerno, A., A. Deletoile, M. Lefevre, I. Ciznar, K. Krovacek, P. Grimont, and S. Brisse. 2007. Recombining population structure of Plesiomonas shigelloides (Enterobacteriaceae) revealed by multilocus sequence typing. J. Bacteriol. 1897808-7818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith, J. M., N. H. Smith, M. O'Rourke, and B. G. Spratt. 1993. How clonal are bacteria? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 904384-4388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spratt, B. G., W. P. Hanage, and E. J. Feil. 2001. The relative contributions of recombination and point mutation to the diversification of bacterial clones. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 4602-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spratt, B. G., and M. C. Maiden. 1999. Bacterial population genetics, evolution and epidemiology. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 354701-710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van Belkum, A., P. T. Tassios, L. Dijkshoorn, S. Haeggman, B. Cookson, N. K. Fry, V. Fussing, J. Green, E. Feil, P. Gerner-Smidt, S. Brisse, and M. Struelens. 2007. Guidelines for the validation and application of typing methods for use in bacterial epidemiology. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 13(Suppl 3)1-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vincent, K., and R. M. Szabo. 1988. Enterobacter agglomerans osteomyelitis of the hand from a rose thorn. A case report. Orthopedics 11465-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wayne, L., D. Brenner, R. Colwell, P. A. Grimont, O. Kandler, M. Krichevsky, L. Moore, W. Moore, R. Murray, E. Stackebrandt, M. Starr, and H. G. Truper. 1987. Report of the Ad Hoc Committee on Reconciliation of Approaches to Bacterial Systematics. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 37463-464. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weinthal, D. M., I. Barash, M. Panijel, L. Valinsky, V. Gaba, and S. Manulis-Sasson. 2007. Distribution and replication of the pathogenicity plasmid pPATH in diverse populations of the gall-forming bacterium Pantoea agglomerans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 737552-7561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wirth, T., D. Falush, R. Lan, F. Colles, P. Mensa, L. H. Wieler, H. Karch, P. R. Reeves, M. C. Maiden, H. Ochman, and M. Achtman. 2006. Sex and virulence in Escherichia coli: an evolutionary perspective. Mol. Microbiol. 601136-1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Young, J. M., and D. C. Park. 2007. Relationships of plant pathogenic enterobacteria based on partial atpD, carA, and recA as individual and concatenated nucleotide and peptide sequences. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 30343-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.