Abstract

We have previously described a novel flavivirus vaccine technology based on a single-cycle, capsid (C) gene-deleted flavivirus called RepliVAX. RepliVAX can be propagated in cells that express high levels of C but undergoes only a single cycle of infection in vaccinated hosts. Here we report that we have adapted our RepliVAX technology to produce a dengue vaccine by replacing the prM/E genes of RepliVAX WN (a West Nile virus [WNV] RepliVAX) with the same genes of dengue virus type 2 (DENV2). Our first RepliVAX construct for dengue virus (RepliVAX D2) replicated poorly in WNV C-expressing cells. However, addition of mutations in prM and E that were selected during blind passage of a RepliVAX D2 derivative was used to produce a second-generation RepliVAX D2 (designated D2.2) that displayed acceptable growth in WNV C-expressing cells. RepliVAX D2.2 grew better in DENV2 C-expressing cells than WNV C-expressing cells, but after several passages in DENV2 C-expressing cells it acquired further mutations that permitted efficient growth in WNV C-expressing cells. We tested the potency and efficacy of RepliVAX D2.2 in a well-described immunodeficient mouse model for dengue (strain AG129; lacking the receptors for both type I and type II interferons). These mice produced dose-dependent DENV2-neutralizing antibody responses when vaccinated with RepliVAX D2.2. When challenged with 240 50% lethal doses of DENV2, mice given a single inoculation of RepliVAX D2.2 survived significantly longer than sham-vaccinated animals, although some of these severely immunocompromised mice eventually died from the challenge. Taken together these studies indicate that the RepliVAX technology shows promise for use in the development of vaccines that can be used to prevent dengue.

Dengue viruses (DENV) are the etiologic agents of dengue fever, dengue hemorrhagic fever, and dengue shock syndrome. The viruses are transmitted to humans by Aedes spp. mosquitoes. DENV infections are a serious cause of morbidity and mortality in most tropical and subtropical areas of the world (12). Dengue cases are estimated to occur in up to 100 million individuals annually, and there are over 2.5 billion people living in areas at risk for infection, making dengue the most important arbovirus disease in the world. DENV belongs to the Flavivirus genus in the family Flaviviridae and exists as four antigenically distinct serotypes (DENV1 to -4) (4). The four serotypes of DENV do not confer cross-protective immunity, and epidemiological evidence indicates that immunity to one serotype of DENV increases the chance of a more severe disease upon infection with a second serotype by about 10-fold (26).

DENV are single-stranded, positive-sense RNA viruses and have an 11-kb genome characterized by a single open reading frame encoding three structural proteins (C, prM/M, and E) and seven nonstructural proteins (NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, and NS5) and untranslated regions at its 5′ and 3′ termini (5′ untranslated region [UTR] and 3′UTR). Viral RNA replication occurs in the cytoplasm via a negative-strand intermediate, leading to the accumulation of positive-strand RNAs. Several NS proteins have been implicated in the process. The NS2B/NS3 serine proteinase is required for processing at multiple sites in the NS polyprotein. NS3 also possesses RNA triphosphatase and RNA helicase activities, and NS5 contains methyltransferases and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase activities (33).

Currently there are licensed vaccines available to prevent yellow fever, Japanese encephalitis (JE), and tick-borne encephalitis. No licensed vaccines are available for dengue, although many are under development, including live-attenuated virus vaccines (LAV), inactivated virus vaccines (INV), and subunit virus vaccines (51). It is generally believed that LAV are more economical to produce and should be able to induce durable humoral and cellular immune responses with one dose. The licensed LAV for yellow fever (strain YFV-17D) is one of the most efficacious vaccines in use today, but an alarming number of cases of YF (indistinguishable from jungle YF and referred to as acute viscerotropic disease following yellow fever vaccination [YEL-AVD]) have been associated with recent YF-17D vaccination campaigns, suggesting that a safer vaccine is needed. Of particular concern are analyses of the viruses recovered from some cases of YEL-AVD that have failed to produce evidence that YEL-AVD has been caused by simple reversion of the vaccine virus, suggesting that the vaccine itself is virulent in some individuals (15). In contrast, INV such as those used to prevent JE are thought to be safer, but these too are in need of improvement, as evidenced by the recent halt in production of the efficacious mouse brain-derived JE INV due to adverse events associated with its use (7). Furthermore, INV are less potent than LAV, generally requiring multiple doses, resulting in high vaccination costs. An experimental INV has been developed for DENV and has demonstrated potency and efficacy in nonhuman primates, but it is likely to be very expensive to manufacture (48).

Recently, we reported the development of single-cycle flaviviruses that can be used as safe and effective vaccines (18, 36, 52). These vaccine candidates, which we have named RepliVAX, are single-round infectious particles that encode a genome harboring a truncated C (trC) gene that prevents the RepliVAX genome from being packaged into infectious particles unless a functional C gene is supplied in trans (for example, by C-expressing packaging cells [18, 36, 52] or by a C-expressing helper genome [47]). RepliVAX can infect normal cells in vaccinated animals, and infected cells release E-containing subviral particles and NS1, which induce antiviral immune responses (both humoral [18, 36, 52] and cellular [J. D. Brien, D. G. Widman, J. L. Uhrlaub, P. W. Mason, and J. Nikolich-Zugich, unpublished data]). However, RepliVAX infection cannot spread or cause disease in vaccinated animals, making RepliVAX a very safe LAV. We have recently shown that RepliVAX WN (derived from West Nile virus [WNV]) can prevent disease in two animal models of WN encephalitis (52). We have also reported that a RepliVAX JE could be produced by replacing the prM/E genes of RepliVAX WN with the same genes of JEV and shown that RepliVAX JE could prevent JE in a murine model for this important disease (18).

In the present study, we report that we have adapted our RepliVAX technology to produce a vaccine for dengue. Specifically, we have shown that a chimeric RepliVAX that expresses the prM/E genes of DENV2 in place of the WNV genes has been developed. This vaccine candidate, referred to as RepliVAX D2, replicated poorly at first. However, by creating a RepliVAX D2 derivative with a longer version of the C gene, transfecting this derivative into WNV C-expressing cells, and cocultivating these cells with WNV C-expressing cells for multiple passages and then further blind-passaging this derivative on cells expressing WNV C, we were able to generate a better-growing version of this construct. Sequence analyses of the “adapted” genome of this construct revealed amino acid changes in prM and E that were used to produce RepliVAX D2.2, which displayed acceptable growth in C-expressing cells. Passage of RepliVAX D2.2 in cells expressing the DENV2 C protein produced further adaptive changes that contributed to the ability of this single-cycle virus to grow in cells expressing the WNV C protein. When RepliVAX D2.2 and its passaged derivatives were used to vaccinate AG129 mice (an immunodeficient murine model for dengue), it produced dose-dependent DENV2-neutralizing antibody responses, and the vaccinated mice were protected from challenge with DENV2.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells, viruses, and RepliVAX.

BHK cells were maintained at 37°C in minimal essential medium (MEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics. Vero cells were maintained at 37°C in MEM containing 6% FBS and antibiotics. BHK(VEErep/C*-E/Pac) cells expressing the WNV C-prM/E proteins (8), BHK(VEErep/Pac-Ubi-C*) cells expressing the WNV C protein (52), and BHK(VEErep/Pac-Ubi-D2C) cells expressing the DENV2 C protein (see below) were propagated at 37°C in Dulbecco's MEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 10 μg/ml puromycin as previously described (8). The WNV derived from an infectious cDNA engineered from a 2002 WNV isolate was previously described (49), and RepliVAX WN.2 has also been described (52). The DENV2 used for in vitro and animal studies consisted of a high-passage, mouse brain-adapted derivative of the New Guinea C (NGC) strain.

Plasmid construction.

The plasmid pBelo WNV-Rz containing the infectious cDNA of a 2002 isolate of WNV was previously described (49). To construct the WNV/DENV2 chimeric cDNA, the WNV prM/E coding region of this bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) plasmid-propagated full-length WNV cDNA was replaced with the cDNA encoding the prM/E genes of DENV2 strain NGC, obtained from a low-passage strain of DENV2 NGC (monkey p1, mosquito p1, and C6/36 p2 [9]).

A previously described RepliVAX WN cDNA that had been introduced into a BAC plasmid to enhance its stability (52) was used to produce a RepliVAX D2 cDNA by replacing the WNV prM/E gene of RepliVAX WN with the prM/E gene of the DENV2 NGC strain. Gene substitution was accomplished by using overlap extension PCR (16) to precisely fuse the last C codon of RepliVAX to the first codon of the DENV2 NGC prM signal and to precisely fuse the last codon of the final transmembrane domain of the DENV2 E protein to the first NS1 codon of RepliVAX. The template used for cDNA amplification consisted of a previously cloned and characterized DENV2 cDNA (9) from the strain described above. The resulting RepliVAX was named RepliVAX D2.

To construct a WNV/DENV2 chimeric virus cDNA with a small deletion in the WNV C gene (referred to as WNV-D2prME shrtC), the truncated C gene found in all RepliVAX WN derivatives (lacking codons 32 to 100) was replaced with a WNV C gene lacking codons 58 to 98.

To obtain a cell line expressing DENV2 C protein, a VEErep (VEErep/Pac-Ubi-D2C) construct was created by substituting the codon-optimized DENV2 C gene (based on the protein sequence of accession number AF038403 [11]) for the WNV C gene in VEErep/Pac-Ubi-C*. BHK cell lines harboring this DENV2 C-expressing VEErep were created as previously described (52). Sequences of all constructs are available from the authors upon request.

RNA transcription and transfection.

To generate synthetic RepliVAX RNAs, the relevant plasmids were linearized with SwaI and the resulting template DNAs were in vitro transcribed using a MegaScript T7 synthesis kit (Ambion) in the presence of 7mG(ppp)G cap analogue (New England Biolabs). For synthetic VEErep RNAs, plasmids were linearized by MluI, and the resulting template DNAs were in vitro transcribed using a MegaScript SP6 synthesis kit (Ambion) in the presence of 7mG(ppp)G cap analogue. The yield and integrity of transcripts were determined by using nondenaturing gel electrophoresis, and aliquots of transcription reaction mixtures were used for transfection without additional purification.

RNA was transfected into BHK packaging cells by using Lipofectin (Invitrogen) with a slight modification of the manufacturer's suggested protocol. Two hours after transfection, the RNA-Lipofectin-medium mixtures were removed from the cell layers and the cells were refed with fresh medium and incubated at 37°C until assayed as described below. In some cases, BHK and BHK packaging cells were electroporated with T7 transcription reactions, and viruses or RepliVAX were collected as previously described (8).

RepliVAX D2 titration.

To determine the titers of viruses and RepliVAX D2 (and its derivatives), cell monolayers prepared in multiwell plates were incubated with dilutions of samples and then overlaid with medium containing 1% FBS (in some cases containing 0.8% carboxymethyl cellulose). Following incubation for the appropriate time, the monolayers were fixed and immunostained as previously described (41), and foci or individual cells were counted and used to calculate a titer of focus-forming units (FFU)/ml for spreading infections or infectious units (IU)/ml for nonspreading infections.

For growth curves, Vero or BHK packaging cells were infected at defined multiplicities of infection (MOIs) and then incubated at 37°C. Media were removed and replaced with fresh media at the indicated time points and stored at −80°C for subsequent titration as described above.

Preparation of RepliVAX D2.2 for in vivo studies.

The second generation of RepliVAX D2 (RepliVAX D2.2; see Results) that contained adaptive mutations in the prM and E genes was used for all animal work. The transcribed RNA was electroporated into BHK(VEErep/C*-E/Pac) cells as described above. The supernatant harvested at day 4 was used to infect BHK(VEErep/Pac-Ubi-D2C) cells. The harvest from this passage (p1) was subsequently concentrated by mixing with polyethylene glycol 8000 (PEG) and NaCl (to achieve final concentrations of 10% and 500 mM, respectively), and the resulting precipitate was collected by high-speed centrifugation. This PEG-concentrated pellet was resuspended in MEM containing 1% FBS at 5% of the original volume. The passage 1 material from the BHK(VEErep/Pac-Ubi-D2C) cells was also passaged a further seven times (p8) in BHK(VEErep/Pac-Ubi-D2C) cells, material from the p8 was concentrated as above using PEG/NaCl, and p9 material was used without a concentration step. For each of these samples, titrations were performed on Vero cells (as described above), and samples were diluted to achieve the concentrations described below.

Mouse inoculations.

Eight-week-old AG129 mice (purpose-raised from founders kindly provided by W. Klimstra) were used to test the ability of a single intraperitoneal (i.p.) inoculation of RepliVAX D2.2 to prevent lethal DENV2 infection. Mice were assigned to the following four groups of 10 animals. The first group received diluent. The second group received 50,000 IU of RepliVAX D2.2 p9 [supernatant fluid prepared without PEG concentration from RepliVAX D2.2 passaged nine times in BHK(VEErep/Pac-Ubi-D2C) cells]. The third group received 500,000 IU of RepliVAX D2.2 p1 [prepared from a PEG concentrate of RepliVAX D2.2 recovered from BHK(VEErep/C*-E/Pac) cells and passed one time in BHK(VEErep/Pac-Ubi-D2C) cells]. The fourth group received 500,000 IU of RepliVAX D2.2 p8 [prepared from a PEG concentrate of material passaged eight times in BHK(VEErep/Pac-Ubi-D2C) cells]. The remaining infectious inocula were back-titered in Vero cells immediately after the vaccination and found to have the expected titers.

Twenty-one days postvaccination, serum was collected from animals by retro-orbital puncture (among three groups, a single animal was lost during this procedure). Pooled samples of sera from each group were used to determine the neutralization antibody titers, and individual sera were tested for specific antibodies for DENV2 E by using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (see below). To assess vaccine efficacy, all mice were challenged at 28 days postvaccination with 1,000 FFU of NGC DENV2 by the i.p. route, a dose corresponding to 240 50% lethal doses (LD50) in these mice. All animals were weighed daily from 3 days prior to challenge and until 28 days postchallenge and examined for signs of infection. Animals that appeared to be unable to survive until the next day (based on lethargy, weight loss, and paralysis) were humanely euthanized in compliance with the UTMB Animal Care and Use Committee requirements and scored as “dead” the following day. All surviving animals were euthanized at 28 days postchallenge.

Microneutralization assay.

Sera from each group were pooled and tested for neutralizing activity on Vero cell monolayers in a focus reduction neutralization test using 96-well plates. Sera were heat inactivated at 56°C for 30 min. Twofold serial dilutions of the serum samples (1/8 to 1/256) were mixed with an equal volume containing 40 FFU of DENV2, strain NGC, and incubated rocking at 37°C for 1 h. Fifty μl of each mixture was transferred to two wells of Vero cells plated in a 96-well plate and incubated rocking at 37°C for 1 h. Duplicate wells of a no-serum control were included in each experiment. After the 1-hour adsorption period at 37°C, the inocula were removed, the cells were rinsed once with medium, and 100 μl of overlay medium (0.8% carboxymethyl cellulose and 2% FBS in MEM) was added to each well. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 72 h and then fixed with acetone-methanol and immunostained as described above, with a flavivirus E-specific monoclonal antibody (37) (generously supplied by E. Konishi). Foci counted in duplicate wells were averaged and compared to the no-serum wells, and neutralization titers were reported as the highest serum dilution yielding a 90% reduction in focus number.

ELISA.

To evaluate the immune responses to DENV2 E, we constructed a VEErep expressing a His-tagged truncated (tr) DENV2 E protein by expressing the first 395 amino acids of DENV2 NGC E followed by a Gly-Gly linker and six His residues in a VEErep, as previously described for a WNV E ELISA antigen (18). A BHK cell line harboring this VEErep was used as the source of DENV2 trE-containing culture fluid, which was used to coat the plates that were used to perform ELISAs as previously described, except that blocking steps and incubations were performed using phosphate-buffered saline containing 5% nonfat dried milk (Carnation) instead of the previously reported horse serum blocking buffer (18). Results are presented as averages and standard deviations of data obtained from duplicate wells determined using 1/100 dilutions of sera from each animal.

RESULTS

Construction and characterization of a chimeric WNV encoding the DENV2 prM/E genes.

We have previously reported that genetically engineered single-cycle flaviviruses containing a deletion of the C gene (named RepliVAX) could be used as a vaccine platform by demonstrating that a chimeric RepliVAX created by replacing the prM/E genes of RepliVAX WN with the same genes of JEV could be used as a vaccine to prevent JE (18). Before applying this method to produce a dengue vaccine, we constructed a full-length chimeric WNV/DENV2 cDNA, which included the prM and E genes of the DENV2 (NGC strain) with all other sequences derived from WNV as shown in Fig. 1A. To demonstrate that this chimeric virus encoding DENV2 prM/E (WNV-D2prME) was viable, full-length RNAs generated by T7 RNA polymerase from this cDNA were transfected into BHK cells. Three days posttransfection, the cells were fixed and immunostained with an anti-WNV hyperimmune mouse ascitic fluid, and 100% of transfected cells were shown to be immunopositive (data not shown), indicating that WNV-D2prME was viable.

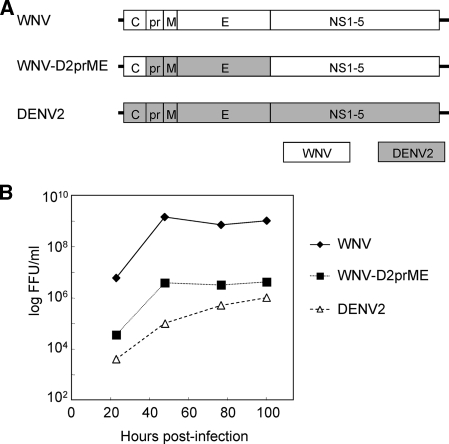

FIG. 1.

Genomic structures and growth properties of WNV, WNV/DENV2 chimera (WNV-D2prME), and DENV2. (A) Schematic representation of the virus genomes. The fusions between the coding regions were precisely constructed to fall at the predicted signal peptidase sites following the C protein by fusing the last codon of the WNV prM signal peptide to the first codon of the mature DENV2 prM and that of the predicted signal peptidase cleavage site following the second transmembrane domain of E by fusing the last codon of DENV2 E to the first codon of WNV NS1. (B) Growth curves showing titers obtained from monolayers of Vero cells infected with the indicated virus at an MOI of 0.02 and incubated at 37°C. At each time point, the media were removed and frozen for subsequent titration and fresh media were added. Virus titers were determined by focus formation assay in Vero cells (see Materials and Methods).

To compare WNV-D2prME to its parents we performed a growth curve analysis on Vero cells. To this end, Vero cells were infected with all three viruses at an MOI of 0.02 FFU/cell, and culture supernatants were taken at the indicated time points. The growth of the chimeric virus was delayed relative to WNV, although the chimeric virus grew faster than DENV2 NGC (Fig. 1B). These results demonstrate that the WNV/DENV2 chimeric genome could be packaged into virus particles using the WNV-C and DENV2-prM/E proteins.

RepliVAX D2 failed to grow in the WNV C-expressing cell line.

Generation of a viable WNV/DENV2 chimeric virus encouraged us to construct a RepliVAX D2 single-cycle virus using the same methods we had applied for producing RepliVAX JE (18) and the WNV/DENV2 chimera. To make a RepliVAX D2-encoding cDNA plasmid, the cDNA corresponding to the prM/E genes of the RepliVAX WN plasmid was replaced by a cDNA encoding prM/E of DENV2. Insertion was accomplished to produce in-frame fusions at the signalase cleavage sites between WNV C and DENV2 prM and between DENV2 E and WNV NS1 precisely as we had done to generate the WNV-D2prME chimera (Fig. 2A).

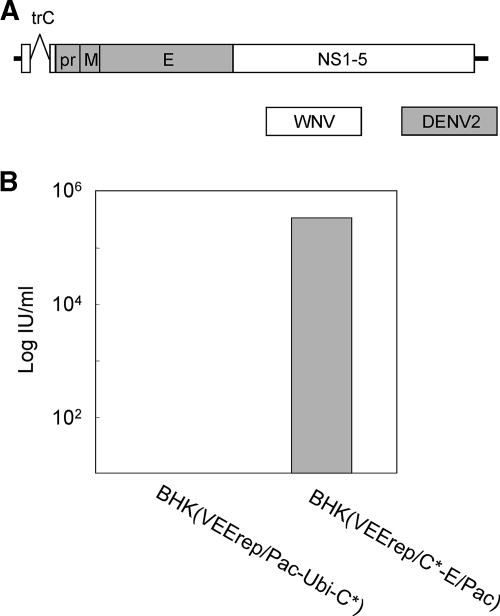

FIG. 2.

Construction of RepliVAX D2. (A) Schematic representation of the genome of RepliVAX D2. Fusion sites used in this construction were precisely the same as those used for construction of WNV-D2prME (see the legend for Fig. 1). (B) Titers of RepliVAX D2 produced by transfection of BHK(VEErep/Pac-Ubi-C*) or BHK(VEErep/C*-E/Pac) with RepliVAX D2 RNA. Dilutions of the supernatant collected 5 days posttransfection were used to inoculate monolayers of BHK(VEErep/Pac-Ubi-C*) cells, the cells were fixed 5 days postinfection and stained with anti-WNV antibody, and then stained cells were counted to determine the titers produced by the transfections.

RNA derived from this plasmid was generated in vitro and transfected into BHK packaging cells, BHK(VEErep/Pac-Ubi-C*) cells expressing WNV C, or BHK(VEErep/C*-E/Pac) cells expressing WNV structural proteins, C, prM, and E (8).

As shown in Fig. 2B, RepliVAX D2 produced a titer of 3.3 × 105 IU/ml in BHK(VEErep/C*-E/Pac) cells 5 days posttransfection. In contrast, no infectious particle production was detected in the supernatant recovered from the transfected BHK(VEErep/Pac-Ubi-C*) cells, although the RepliVAX D2-transfected BHK(VEErep/Pac-Ubi-C*) cultures contained large numbers of cells that were immunostained by a WNV antibody that was unable to detect the cells in the absence of transfection (data not shown). These virus titration data suggested that the RepliVAX D2 genome was able to replicate and be packaged into WNV-C/prM/E particles, whereas trans-expressed WNV-C was not able to complement DENV2-prM/E for efficient production of infectious particles. This interpretation was confirmed by studies showing the RepliVAX D2 particles recovered from transfected WNV C/prM/E-expressing cells could not be neutralized by a DENV2 E-specific antibody and RepliVAX D2 particles recovered from transfected WNV C-expressing cells were neutralized by this DENV2-specific antibody, whereas the converse neutralization results were obtained with a WNV E-specific antibody (results not shown). Despite our inability to detect RepliVAX D2 particles in culture fluid obtained from transfected C-expressing cells, the large number of immunopositive cells in the cultures of BHK(VEErep/Pac-Ubi-C*) transfected with RepliVAX D2 RNA suggested that RepliVAX D2 particles could be produced in the presence of trans-expressed WNV C.

Serial passage of WNV/DENV2 chimera virus with small deletion of C gene.

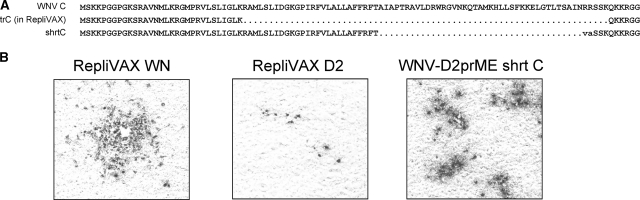

Since RepliVAX D2 could clearly replicate its genome but appeared to be very inefficient at spreading in BHK(VEErep/Pac-Ubi-C*) cells, blind passages of RepliVAX D2 were performed in BHK(VEErep/Pac-Ubi-C*) cells to obtain a better-growing strain, a method that had helped us to produce a better-growing RepliVAX JE (18). However, the titer of RepliVAX D2 produced by BHK(VEErep/Pac-Ubi-C*) appeared to be too low for this procedure, and the infectious titer was lost during the passaging procedure (results not shown). To aid in the recovery of a better-growing RepliVAX, we took advantage of data from other studies on WNV replicons that indicated that replicons with an incomplete but slightly larger version of the C gene (shrtC) displayed replication properties superior to replicons containing the trC gene found in RepliVAX (R. Fayzulin and P. W. Mason, unpublished data). To this end, we constructed WNV/DENV2 chimera virus with this shrtC gene (named WNV-D2prME shrtC) (Fig. 3A). When transcribed RNA for WNV-D2prME shrtC was introduced into BHK(VEErep/Pac-Ubi-C*), this RNA produced foci of infection larger than those produced by RepliVAX D2 RNA transfection but smaller than those produced by RepliVAX WN RNA (Fig. 3B). Despite this apparent enhancement in packaging over RepliVAX D2, we were unable to blind passage WNV-D2prME shrtC in BHK(VEErep/Pac-Ubi-C*) cells.

FIG. 3.

Effect of addition of C coding sequences on focus formation by single-cycle chimeric viruses. (A) Segment of the WNV coding region showing the WT C gene, the C gene deletion of RepliVAX, and shrtC. (B) Micrographs of monolayers of BHK(VEErep/Pac-Ubi-C*) transfected with the in vitro transcripts of the indicated constructions and then fixed at 5 days posttransfection and stained with anti-WNV antibody.

To overcome this apparent severe growth defect when we attempted to complement in trans the DENV2 prM/E with trans-expressed WNV C, we undertook the unusual blind passaging procedure of trypsinizing the cultures of the WNV-D2prME shrtC RNA-transfected BHK(VEErep/Pac-Ubi-C*) cells and then passaging the cells in the presence of a fourfold addition of naïve BHK(VEErep/Pac-Ubi-C*) cells. Using this unusual strategy, the cultures continued to produce low, but detectable, titers of infectivity (close to 103 IU/ml). The supernatant obtained from the eighth such passage of these cocultured cells (t8) was then blind passaged an additional six times on BHK(VEErep/Pac-Ubi-C*) cells, and the sixth blind passage sample (t8/p6) showed a titer of greater than 105 IU/ml on BHK(VEErep/Pac-Ubi-C*) cells.

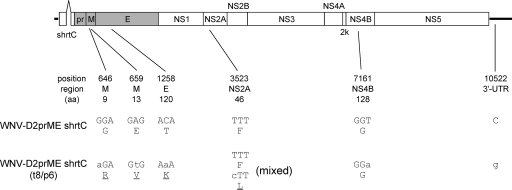

Sequence analyses were used to determine how WNV-D2prME shrtC changed during the passage. To address this, the t8/p6 stock of WNV-D2prME shrtC was inoculated into Vero cell cultures (to permit amplification of the flavivirus genome in the absence of the packaging cell line-encoded C gene), and RNA was extracted 2 days postinfection. The RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA, and the full-length viral genome was sequenced using previously described methods (49). Analysis of these sequence data revealed that blind-passaged WNV-D2prME shrtC had six nucleotide changes relative to the original sequence (Fig. 4). These included two nucleotide changes in the M-coding region, resulting in amino acid codon changes at position 9 (G to R) and position 13 (E to V), and one mutation in the E-coding region, resulting in a change of a T to a K codon at position 120. Analyses of these data also revealed a change in the NS2A-coding region, which resulted in an F-to-L coding change. However, this position appeared to contain a mixture of the original and mutated nucleotides, suggesting that this mutation was not essential for efficient viral replication. One synonymous change was detected in the NS4B coding region, as well as a change in the 3′UTR (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Schematic diagram showing the WNV-D2prME shrtC and the mutations that were detected in the genome of the variant passaged eight times by mixing trypsinized infected BHK(VEErep/Pac-Ubi-C*) cells with naïve cells and then six times by simple passage of infected culture fluid in BHK(VEErep/Pac-Ubi-C*) (see text). The “position” indicates the number of altered nucleotides in the genome, “region” indicates functional localization, and “aa” indicates the amino acid position of the affected codon within the individual protein-coding regions. Lowercase letters designate nucleotide changes, and underlined amino acids indicate changes in coding capacity.

Incorporation of mutations into the RepliVAX D2 genome.

Among six mutations observed in the blind-passaged WNV-D2prME shrtC, we focused on the three mutations in the M and E protein-coding regions, since amino acid changes in viral structural proteins appeared likely to be the primary cause of the improved viral replication. In addition, the mutation in NS2A was a mixed population, and mutation in NS4B did not produce an amino acid change. Although the change in the 3′UTR was intriguing, its location at a position between conserved elements RCS3 and CS3 that were found only in flaviviruses from the JEV complex (13, 20, 21) argued that it was unlikely to contribute substantially to viral replication.

To directly determine whether these mutations in the structural region were responsible for the enhanced growth, RepliVAX D2 genomes containing either the two neighboring mutations in M (Mmut) or the single mutation in E (Emut), or all three mutations (MEmut, referred to from this point forward as RepliVAX D2.2), were constructed.

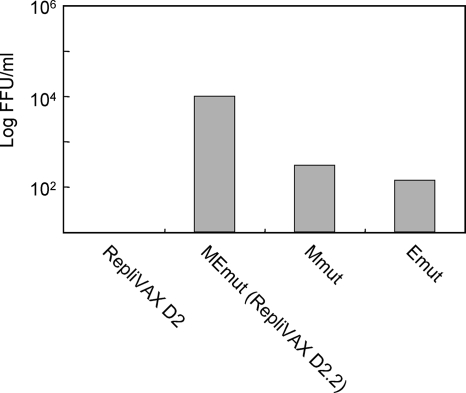

BHK(VEErep/Pac-Ubi-C*) cells were transfected with each of these newly generated RNAs and cultured for 4 days. The titer obtained from cells transfected with the RepliVAX D2 RNA containing both the M and E mutations was significantly higher than those of RNAs containing either M or E mutations, whereas the cells transfected with RNA from the original RepliVAX D2 produced no detectable titer (Fig. 5), suggesting that both M and E mutations needed to act cooperatively to improve the growth of RepliVAX D2. Furthermore, similarity in growth of WNV-D2prME shrtC t8/p6 and a genetically engineered derivative of WNV-D2prME shrtC that contained all three structural protein gene mutations argued that the NS protein and 3′UTR mutations selected during the passage had no growth-promoting capabilities (results not shown). The inability of the M and E mutations to independently effect better growth of these chimeric viruses was consistent with the prolonged passaging protocol that was needed to obtain a substantially better-growing version of WNV-D2prME shrtC.

FIG. 5.

Demonstration that structural protein mutations found in WNV-D2prME shrtC (t8/p6) enhance replication of RepliVAX D2. Supernatants recovered from BHK(VEErep/Pac-Ubi-C*) cells 4 days posttransfection with synthetic RepliVAX D2 RNA or derivatives containing both M mutations (Mmut), the E mutation (Emut), or all three mutations (RepliVAX D2.2) were diluted and used to infect monolayers of BHK(VEErep/Pac-Ubi-C*) cells. Six days later the monolayers were fixed and stained with anti-WNV antibodies and the numbers of FFU per ml were calculated.

DENV2 C-expressing cells can produce RepliVAX D2.2 more efficiently than WNV C-expressing cells.

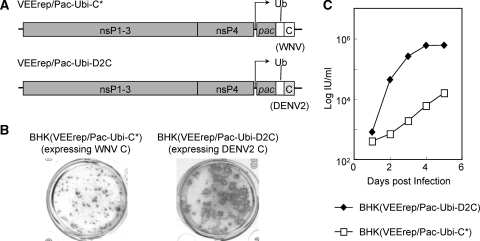

Although RepliVAX D2.2 could be readily propagated on BHK(VEErep/Pac-Ubi-C*) cells, the titers of the released infectious particles never exceeded 104 IU/ml. Therefore, we tested to see if RepliVAX D2.2 could be grown to higher titers in DENV2 C-expressing cells. To this end, DENV2 C-expressing cells were established using a VEE replicon encoding codon-optimized DENV2 C sequence [BHK(VEErep/Pac-Ubi-D2C)] (Fig. 6A), using precisely the same strategy employed to make the VEErep used in the production of the BHK(VEErep/Pac-Ubi-C*) cells (see Materials and Methods). Side-by-side focus formation assays of RepliVAX D2.2 on WNV C-expressing cells and DENV2 C-expressing cells revealed that RepliVAX D2.2 produced larger foci on DENV2 C-expressing cells than on WNV C-expressing cells (Fig. 6B). Side-by-side growth curves were also generated with RepliVAX D2.2 in infected WNV C-expressing cells or DENV2 C-expressing cells. As shown in Fig. 6C, RepliVAX D2.2 grew faster and to higher titers on DENV2 C-expressing cells than on WNV C-expressing cells.

FIG. 6.

RepliVAX D2.2 grows better in packaging cells expressing the DENV2 C protein than cells expressing the WNV C protein. (A) Schematic representation of the VEE replicon used to supply the WNV and DENV2 C protein in packaging cells. Noncytopathic VEE replicons (VEErep/Pac-Ubi-C* or VEErep/Pac-Ubi-D2C) encode the mature C of WNV or DENV2 along with the Pac-selectable marker expressed as a fusion protein with ubiquitin. (B) Photographs of immunohistochemically stained RepliVAX D2.2 foci of infection produced on monolayers of BHK(VEErep/Pac-Ubi-C*) cells or BHK(VEErep/Pac-Ubi-D2C) cells. Infected monolayers were incubated for 5 days under a carboxymethyl cellulose overlay and then fixed and stained with anti-WNV antibody. (C) Growth curves of RepliVAX D2.2 on BHK(VEErep/Pac-Ubi-C*) or BHK(VEE/Pac-Ubi-D2C) cells. Monolayers of BHK packaging cells were infected with the RepliVAX D2.2 at an MOI of 0.5 and incubated at 37°C. At each time point, the media were removed and frozen for subsequent titration and fresh media were added. RepliVAX titers were determined by infectious assay in Vero cells (see Materials and Methods).

Further passage of RepliVAX D2.2 yielded even-better-growing variants that grew well in cells expressing WNV-C.

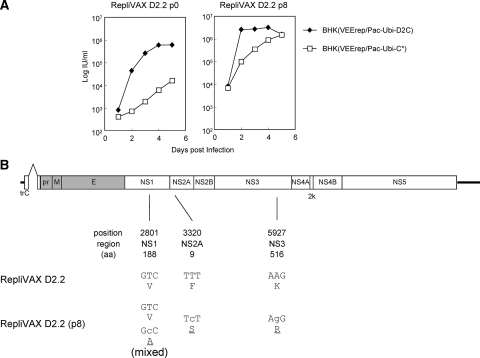

Successful propagation of RepliVAX D2.2 using BHK(VEErep/Pac-Ubi-D2C) encouraged us to examine whether blind passage of RepliVAX D2.2 could generate a better-growing derivative. Following multiple passages on these DENV2 C-expressing cells we were able to demonstrate that RepliVAX D2.2 at the eighth blind passage produced larger foci on BHK(VEErep/Pac-Ubi-D2C) than the passage 0 stocks (harvested from transfection) and grew to titers of greater than 106 IU/ml (results not shown). Side-by-side growth analysis revealed that the RepliVAX D2.2 p8 achieved titers up to fivefold higher than RepliVAX D2.2 p0 on BHK(VEErep/Pac-Ubi-D2C) (Fig. 7A). In addition, RepliVAX D2.2 p8 achieved titers approximately 100 times higher than RepliVAX D2.2 p0 on BHK(VEErep/Pac-Ubi-C*) cells which produced the WNV C protein (Fig. 7A). Sequencing of the entire genome of this p8 population revealed three nonsynonymous changes in NS1, NS2A, and NS3 (Fig. 7B). The NS1 mutation was found as a mixed population, suggesting it was not important for the enhanced growth phenotype, which was confirmed using reverse genetics studies (results not shown). Similar reverse genetics studies showed that RepliVAX D2.2 recreated with both the NS2A and NS3 mutations grew to higher titers than the parental RepliVAX D2.2, although neither of these mutations appeared to have a demonstrable effect on genome replication (when inserted separately or together in replicon RNAs). NS2A has previously been implicated in flavivirus packaging, although our mutation is found distant (on the linear NS2A peptide) from mutations previously shown to have an effect on packaging (25, 32). Furthermore, an NS3 mutation found some distance from our mutation, but still within the RNA helicase domain of NS3, has been shown to have a deleterious effect on packaging (39).

FIG. 7.

Phenotypic and genotypic changes observed in RepliVAX D2.2 following blind passage on BHK(VEErep/Pac-Ubi-D2C) cells. (A) Growth curves of RepliVAX D2.2 p0 (recovered directly from electroporation) and RepliVAX D2.2 p8 [from passages performed on BHK(VEE/Pac-Ubi-D2C) cells] performed on BHK(VEErep/Pac-Ubi-C*) cells (open squares) or BHK(VEE/Pac-Ubi-D2C) cells (filled diamonds). Cells were infected at an MOI of 0.5, medium was collected, and titers were determined on Vero cells as indicated in Materials and Methods. (B) Schematic diagram showing the RepliVAX D2.2 genome and the mutations that were detected in the genome of the variants passaged eight times BHK(VEErep/Pac-Ubi-D2C) cells. The “position” indicates the number of altered nucleotides in the genome, “region” indicates functional localization, and “aa” indicates the position of the affected codon within the individual protein-coding regions. Lowercase letters designate nucleotide changes, and underlined amino acids indicate changes in coding capacity.

Determination of RepliVAX D2.2 potency and efficacy in AG129 mice.

To determine RepliVAX D2.2 potency and efficacy we utilized severely immunodeficient strain AG129 mice, which are susceptible to morbidity and mortality following peripheral DENV infection (19). Mice were bred under standard sterile housing conditions and then inoculated by the i.p. route with three different preparations of RepliVAX D2.2 (see Materials and Methods). Twenty-one days postinoculation blood was collected from the mice by retro-orbital puncture, and sera obtained from these samples were tested by ELISA and microneutralization assays to determine individual and group titers, respectively. Table 1 shows the results of these studies. The ELISA data show the average and standard deviations of the optical density values obtained with a single serum dilution (1/100), and the neutralization data show the serum dilutions that produced a 90% neutralization of DENV2. Both tests showed low or undetectable serological activity in the diluent-inoculated mice and dose-dependent DENV2-specific responses in the RepliVAX D2.2-inoculated mice. These data failed to show any convincing differences in the responses to the various RepliVAX D2.2 preparations, consistent with the small changes observed in the genomes of the passaged variants (Fig. 7B).

TABLE 1.

Prechallenge serology and summary of postchallenge efficacy data from AG129 mice vaccinated with RepliVAX D2.2 and challenged with DENV2 NGC

| Vaccination group | Prechallenge serologya

|

% Efficacy

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protection from morbidity ond:

|

Protection from mortality one:

|

|||||

| DENV2 trE ELISAb | Neut. titerc | Day 21 | Day 28 | Day 21 | Day 28 | |

| 1: diluent | 0.09 (0.04) | <1:16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2: RepliVAX D2.2 p9, 50,000 IU | 0.45 (0.27) | 1:16 | 67 | 33 | 78 | 33 |

| 3: RepliVAX D2.2 p8, 500,000 IU | 0.77 (0.24) | 1:32 | 90 | 80 | 100 | 100 |

| 4: RepliVAX D2.2 p1, 500,000 IU | 1.00 (0.47) | 1:32 | 67 | 56 | 89 | 78 |

Serology data were obtained using sera collected at 21 days postvaccination.

Average of trE ELISA ODs obtained from 1/100 dilutions of sera obtained from all animals in each group; standard deviations within the groups are shown in parentheses.

Highest serum dilution (from pooled sera from all animals) yielding 90% focus reduction as determined using a microneutralization test with DENV2.

Protection from morbidity was recorded at 21 or 28 days postchallenge (see Fig. 8A). Statistical significance values (calculated by Fisher's exact test using two-tailed analyses) between group 1 and the other groups were found to be <0.01 (1 versus 2), <0.0001 (1 versus 3), <0.01 (1 versus 4) on day 21, and not significant (NS; 1 versus 2), <0.001 (1 versus 3), and <0.05 (1 versus 4) on day 28.

Protection from mortality was recorded at 21 or 28 days postchallenge (see Fig. 8B). Statistical significance values (calculated by Fisher's exact test using two-tailed analyses) between group 1 and the others were found to be <0.005 (1 versus 2), <0.0001 (1 versus 3), and <0.001 (1 versus 4) on day 21 and NS (1 versus 2), <0.0001 (1 versus 3), and <0.005 (1 versus 4) on day 28.

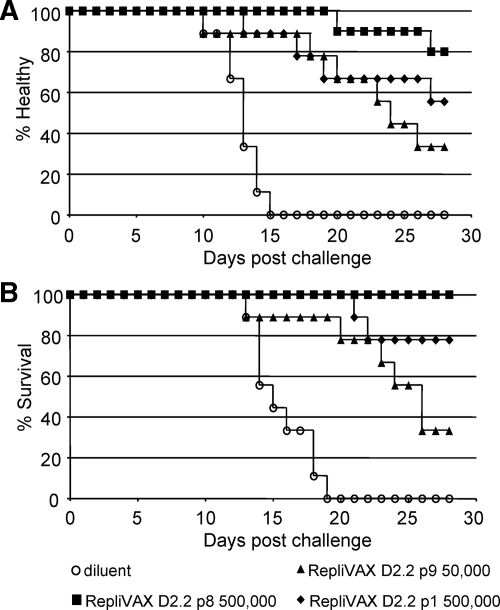

Twenty-eight days after their single vaccination with RepliVAX D2.2, the animals for whom results are shown in Table 1 were challenged by i.p. inoculation with 1,000 FFU of a mouse brain-adapted DENV2 NGC, a challenge dose that corresponds to 240 LD50 in AG129 mice. The postchallenge data from these studies are shown in Fig. 8 and summarized in Table 1. These studies demonstrated that this challenge dose produced 100% morbidity (as measured by a 10% drop in weight) (Fig. 8; Table 1) and 100% mortality by days 15 and 19, respectively, in diluent-vaccinated animals. Vaccination with any of the doses of RepliVAX D2.2 evaluated in this experiment produced significant delays in the onset of both illness and death in these animals (Fig. 8; Table 1). Inspection of the data from this experiment shows a clear correlation of protection from morbidity and mortality with vaccine dose and prechallenge serological data (Fig. 8; Table 1). Further, over the 28-day course of observation not a single animal died in the group inoculated with 500,000 IU of the RepliVAX D2.2 p8, and in this group only two animals showed illness due to infection and this appeared late in the challenge period (Fig. 8; Table 1).

FIG. 8.

Vaccination with RepliVAX D2.2 protects AG129 mice from DENV2 NGC morbidity and mortality. (A) Kaplan-Meier curve showing onset of illness (as indicated by loss of 10% of weight relative to day of challenge) in animals following challenge with 240 LD50 of DENV2 NGC (see Materials and Methods). (B) Kaplan-Meier curve showing onset of death following challenge with 240 LD50 of DENV2 NGC (see Materials and Methods). Statistical significance levels for diluent and vaccine groups in terms of morbidity and mortality are shown in Table 1.

DISCUSSION

A safe and effective vaccine to prevent dengue is urgently needed. We have previously reported that RepliVAX, which is based on a single-cycle infectious WNV (36, 52), could be used to produce a safe and effective JE vaccine by replacing the prM/E genes of RepliVAX WN with the same genes of JEV (18). In this study, we showed that this strategy could also be used to produce a RepliVAX WN-based dengue vaccine. However, a suitable chimeric RepliVAX D2 construct with our RepliVAX WN proved much more difficult to obtain than the RepliVAX JE construct.

Our initial RepliVAX D2 construct, produced by the identical strategy used to produce RepliVAX JE, failed to produce detectable titers of infectious particles when it was propagated on cell lines expressing the trans-complementing WNV C protein. However, this RepliVAX D2 construct was able to produce infectious particles when introduced into WNV C/prM/E-expressing cells, indicating that the trans-expressed WNV C and cis-expressed DENV2 prM/E were less efficiently utilized for genome encapsidation than when all three structural proteins were coexpressed in trans. Although we have not fully determined why the RepliVAX-encoded DENV2 prM/E proteins were so poorly utilized for encapsidation with the trans-expressed WNV C, we have also noted that RepliVAX WN grows more poorly in WNV C-expressing cells than in cells expressing WNV C/prM/E (R. Suzuki and P. Mason, unpublished data). Thus, the poor growth performance of our initial RepliVAX D2 construct could result from the lower efficiency of encapsidation by trans-expressed homologous C, exacerbated by the use of a heterologous prM/E. Further support for this idea came from studies demonstrating that a chimeric virus encoding the DENV2 prM/E with the intact WNV C coding region (WNV-D2prME) grew faster than the parental DENV2 NGC, demonstrating that DENV2 prM and E were clearly competent for viral assembly with the WNV C protein (although, as discussed below, we found some evidence that the DENV2 C protein could be used more efficiently than the WNV C protein by DENV2 prM and E).

Studies to “rationally” enhance the replication of RepliVAX D2 by making a large number of different mutations within the DENV2 prM signal peptide of RepliVAX D2 (which differs significantly in both length and amino acid sequence from the WNV prM signal peptide) did not result in the generation of single-cycle viruses that grew more efficiently (Suzuki and Mason, unpublished). In addition, blind passage of WNV-D2prME (the fully infectious chimera) in normal cells did not readily produce better-growing variants (Suzuki and Mason, unpublished). Therefore, we attempted to blind passage our single-cycle viruses to produce better-growing variants, which we presumed would select variants with enhanced trans-encapsidation efficiency. This strategy, which we had successfully employed to produce better-growing variants of RepliVAX WN and RepliVAX JE (18, 52), failed to produce positive results, likely due to the very low titers obtained with both RepliVAX D2 and the related construct WNV-D2prME shrtC. When this strategy failed, we decided to blind passage WNV-D2prME shrtC, using the unusual strategy of passaging the C-expressing cells infected with this crippled virus and later passaging the virus itself. Interestingly, the better-growing passaged populations of WNV-D2prME shrtC obtained from this passaging regimen contained multiple mutations, including three nonsynonymous changes in the M and E regions. Although reverse genetics studies demonstrated that either the two M or single E mutations improved the production of infectious particles of RepliVAX D2, RepliVAX D2.2, which contained all three of these structural protein mutations, replicated much better in WNV C-expressing cells than the parental RepliVAX D2. The positions of these mutations were initially surprising to us, since we had previously found that blind passaging of RepliVAX WN (52) and RepliVAX JE (18) selected adaptive mutations at the junction between prM and the truncated C protein, and work by multiple other groups had also demonstrated that amino acid changes near the NS2B/NS3 cleavage site in this region of the flavivirus genome can alter encapsidation efficiency (1, 23, 30, 34, 53).

The mechanism(s) by which these three structural protein mutations enhanced the yield of RepliVAX D2 is currently under investigation. Their effects could be manifest at several levels, including improved assembly of prM/E into provirions, improved maturation, improved stability of the mature virion, improved receptor binding/entry, and/or improved specific infectivity. For a number of viruses (including flaviviruses) it has been demonstrated that adaptation to grow in some cell lines results in the selection of mutants that bind heparin with high affinity (5, 22, 29, 31, 35, 42). This phenomenon appears to result from selection of viruses that harbor mutations that increase the positive charge on surface proteins, permitting more efficient interaction with the cell surface heparan sulfate or another negatively charged glycosaminoglycan(s), facilitating infection. All three structural protein mutations we observed in the blind-passaged WNV-D2prME shrtC resulted in a net increase in positive charge, suggesting that these mutations could enhance binding to cells, improving the infectivity of RepliVAX D2.2. The E protein mutation selected in this manner was on the surface of domain II of the DENV 2 E protein, and the Lys residue selected at this position (residue 120) has previously been associated with increased DENV2 binding to heparin, more rapid clearance following peripheral inoculation in AG129 mice, lower neuroinvasiveness in these mice, and increased specific infectivity in cells in culture (31). Although insertion of this E mutation on its own improved the growth characteristics of RepliVAX D2, it was more efficient in improving growth when combined with two mutations in M. Even though a detailed three-dimensional structure of this region of M is not available, a cryo-electron microscopy structure (54) has been derived which places the transmembrane domains of M in proximity to the domain II (residue 120) mutation we found in E. The proximity of our two M mutations to the transmembrane domain of M suggests that all three of our selected mutations could function together to facilitate binding to negatively charged cell surface molecules, enhancing RepliVAX D2 growth. However, these two M mutations are also near the furin cleavage site in prM, so it is possible that they might be able to increase growth of RepliVAX D2.2 through an alternative mechanism. As a further alternative, it is possible that these mutations may also have contributed to the ability of the DENV2 prM/E cassette to function in the context of the WNV C protein (see below), although we did not test this directly.

Other studies revealed that the DENV2 C-expressing cells produced RepliVAX D2.2 more efficiently than WNV C-expressing cells, suggesting that, despite the lack of readily visible associations between the nucleocapsid and envelope glycoproteins of mature (24) or immature (55) flavivirus particles, the ability of C to interact with these proteins may be important for genome encapsidation. For hepatitis C virus, a member of another genus in the family Flaviviridae, the oligomerized core protein has been shown to interact with E1 protein (38). Although this type of interaction has not been reported for the C and M/E proteins among members of the Flavivirus genus, such an interaction might affect efficient viral assembly and could help to explain our data.

Further blind passage of RepliVAX D2.2 on DENV2 C-expressing cells produced populations of RepliVAX with an increased ability to grow both in these cells and in cells that expressed the WNV C protein. Interestingly, the mutations detected in this blind-passaged population were found in the NS1, NS2A, and NS3 regions of the genome. However, only the NS2A and NS3 mutations appeared to be needed to confer the enhanced growth properties. The precise mechanism by which our NS2A and NS3 mutations influence RepliVAX yield will be of great interest to explore, since these studies could lead to methods to enhance the yields (and possibly efficacies) of all RepliVAX-based vaccines.

As part of our studies to evaluate our vaccines, we performed an efficacy study in the severely immunodeficient mouse model for dengue (19). This strain of mouse has been used for studies to evaluate dengue pathogenesis (28, 43, 44) and has also been reported to be useful in vaccine studies (6, 17, 27). Although we had some concerns about the abilities of these mice to mount an effective immune response to RepliVAX D2.2 inoculation, we detected no untoward effects of vaccination (consistent with the inability for high-dose RepliVAX WN to cause disease in severely immuno-incompetent baby mice [36]), and we detected readily measurable levels of both anti-E immunoglobulin G and neutralizing antibodies. Following vaccination we challenged these mice with a highly passaged, mouse brain-adapted strain of DENV2 NGC. This challenge virus was surprisingly virulent in these mice, with the challenge dose of 1,000 FFU in cell culture corresponding to over 240 times the LD50. Despite this highly lethal challenge, 100% of the mice given a single dose of RepliVAX in one of our vaccine groups survived for 28 days postvaccination, and all groups showed statistically significant protection from infection relative to diluent-inoculated animals at either 21 or 28 days postchallenge. All of the vaccinated animals that did succumb to the challenge did so after all of the control animals had died. We believe that the eventual demise of these animals is consistent with the severely immunodeficient phenotype of these mice, which would have prevented them from mounting an effective cytotoxic T-cell response, which is known to be essential for recovery from flavivirus infections (3, 40, 45, 46, 50).

Due to the well-known epidemiological association of severe dengue disease with secondary dengue infection, it is widely accepted that any dengue vaccine deployed for widespread use must produce high-titer tetravalent immunity or run the risk of producing more severe disease in vaccinated populations (14). This poses challenges for the use of tetravalent LAV, since the coadministration of a tetravalent LAV might result in competition, dampening the infection (and hence potency) of one or more of the serotypes. This type of competition has been observed in some studies (2, 10), but it remains unclear if competition will be a problem as these products are further developed. In the case of single-cycle particle vaccines, this problem may be lessened by using high doses of each component of the vaccine, initiating synchronous infections that may be less susceptible to competition. From that standpoint, RepliVAX may have some advantages over other types of LAV, but titers of RepliVAX will likely need to be higher to effect efficient vaccination. From that standpoint, we were particularly disappointed by the low titer of our prototype RepliVAX D2 construct, and although RepliVAX D2.2 grows to higher titers, we expect that additional improvement in titer (and/or boosting) will be essential for its eventual utility as a human vaccine candidate.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that the single dose of our unique single-cycle dengue vaccine was able to elicit neutralizing antibodies in mice and provide protection from lethal challenge with DENV2. The demonstration of the immunogenicity and protective efficacy of RepliVAX D2.2 as a vaccine against DENV2 challenge in mice indicates that the RepliVAX platform is suitable for developing a dengue vaccine.

Acknowledgments

We thank W. Klimstra, LSU Health Sciences Center, Shreveport, LA, for supplying the founders for our AG129 colony. We thank T. Ishikawa (UTMB) for help with serological assays, E. Infante (UTMB) for supplying the DENV2 trE antigen, E. Konishi (Kobe University) for supplying the 10B4 monoclonal antibody, N. Bourne (UTMB) for help with statistical analyses, and Richard J. Kuhn (Purdue University) for confirming our interpretations on the expected locations of M mutations on the three-dimensional structure of the RepliVAX particle.

This work was supported by a grant from NIAID to P.W.M. through the Western Regional Center of Excellence for Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Disease Research (NIH grant number U54 AI057156) and a grant from the Sealy Center for Vaccine Development.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 10 December 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amberg, S. M., and C. M. Rice. 1999. Mutagenesis of the NS2B-NS3-mediated cleavage site in the flavivirus capsid protein demonstrates a requirement for coordinated processing. J. Virol. 738083-8094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blaney, J. E., Jr., J. M. Matro, B. R. Murphy, and S. S. Whitehead. 2005. Recombinant, live-attenuated tetravalent dengue virus vaccine formulations induce a balanced, broad, and protective neutralizing antibody response against each of the four serotypes in rhesus monkeys. J. Virol. 795516-5528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brien, J. D., J. L. Uhrlaub, and J. Nikolich-Zugich. 2007. Protective capacity and epitope specificity of CD8+ T cells responding to lethal West Nile virus infection. Eur. J. Immunol. 371855-1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burke, D. S., and T. P. Monath. 2001. Flaviviruses, p. 1043-1125. In D. M. Knipe, P. M. Howley, D. G. Griffin, R. A. Lamb, M. A. Martin, and B. Roizman (ed.), Fields Virology, 4th ed., vol. 1. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Byrnes, A. P., and D. E. Griffin. 1998. Binding of Sindbis virus to cell surface heparan sulfate. J. Virol. 727349-7356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calvert, A. E., C. Y. Huang, R. M. Kinney, and J. T. Roehrig. 2006. Non-structural proteins of dengue 2 virus offer limited protection to interferon-deficient mice after dengue 2 virus challenge. J. Gen. Virol. 87339-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2008. Prevention of specific infectious diseases: Japanese encephalitis. CDC health information for travelers, 2008. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA.

- 8.Fayzulin, R., F. Scholle, O. Petrakova, I. Frolov, and P. W. Mason. 2006. Evaluation of replicative capacity and genetic stability of West Nile virus replicons using highly efficient packaging cell lines. Virology 351196-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fonseca, B. A. L. 1994. Vaccinia-vectored dengue vaccine candidates elicit neutralizing antibodies in mice. Doctoral thesis. Yale, New Haven, CT.

- 10.Galler, R., R. S. Marchevsky, E. Caride, L. F. Almeida, A. M. Yamamura, A. V. Jabor, M. C. Motta, M. C. Bonaldo, E. S. Coutinho, and M. S. Freire. 2005. Attenuation and immunogenicity of recombinant yellow fever 17D-dengue type 2 virus for rhesus monkeys. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 381835-1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gualano, R. C., M. J. Pryor, M. R. Cauchi, P. J. Wright, and A. D. Davidson. 1998. Identification of a major determinant of mouse neurovirulence of dengue virus type 2 using stably cloned genomic-length cDNA. J. Gen. Virol. 79437-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gubler, D. J., and M. Meltzer. 1999. Impact of dengue/dengue hemorrhagic fever on the developing world. Adv. Virus Res. 5335-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hahn, C. S., Y. S. Hahn, C. M. Rice, E. Lee, L. Dalgarno, E. G. Strauss, and J. H. Strauss. 1987. Conserved elements in the 3′ untranslated region of flavivirus RNAs and potential cyclization sequences. J. Mol. Biol. 19833-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halstead, S. B., and J. Deen. 2002. The future of dengue vaccines. Lancet 3601243-1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayes, E. B. 2007. Acute viscerotropic disease following vaccination against yellow fever. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 101967-971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higuchi, R., B. Krummel, and R. K. Saiki. 1988. A general method of in vitro preparation and specific mutagenesis of DNA fragments: study of protein and DNA interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 167351-7367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang, C. Y., S. Butrapet, K. R. Tsuchiya, N. Bhamarapravati, D. J. Gubler, and R. M. Kinney. 2003. Dengue 2 PDK-53 virus as a chimeric carrier for tetravalent dengue vaccine development. J. Virol. 7711436-11447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishikawa, T., D. G. Widman, N. Bourne, E. Konishi, and P. W. Mason. 2008. Construction and evaluation of a chimeric pseudoinfectious virus vaccine to prevent Japanese encephalitis. Vaccine 262772-2781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson, A. J., and J. T. Roehrig. 1999. New mouse model for dengue virus vaccine testing. J. Virol. 73783-786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khromykh, A. A., and E. G. Westaway. 1994. Completion of Kunjin virus RNA sequence and recovery of an infectious RNA transcribed from stably cloned full-length cDNA. J. Virol. 684580-4588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khromykh, A. A., and E. G. Westaway. 1997. Subgenomic replicons of the flavivirus Kunjin: construction and applications. J. Virol. 711497-1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klimstra, W. B., K. D. Ryman, and R. E. Johnston. 1998. Adaptation of Sindbis virus to BHK cells selects for use of heparan sulfate as an attachment receptor. J. Virol. 727357-7366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kofler, R. M., J. H. Aberle, S. W. Aberle, S. L. Allison, F. X. Heinz, and C. W. Mandl. 2004. Mimicking live flavivirus immunization with a noninfectious RNA vaccine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1011951-1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuhn, R. J., W. Zhang, M. G. Rossmann, S. V. Pletnev, J. Corver, E. Lenches, C. T. Jones, S. Mukhopadhyay, P. R. Chipman, E. G. Strauss, T. S. Baker, and J. H. Strauss. 2002. Structure of dengue virus: Implications for flavivirus organization, maturation, and fusion. Cell 108717-725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kummerer, B. M., and C. M. Rice. 2002. Mutations in the yellow fever virus nonstructural protein NS2A selectively block production of infectious particles. J. Virol. 764773-4784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kurane, I., and F. A. Ennis. 1997. Immunopathogenesis of dengue virus infections, p. 273-290. In D. J. Gubler and G. Kuno (ed.), Dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever. CABI Publishing, Oxon, United Kingdom.

- 27.Kyle, J. L., S. J. Balsitis, L. Zhang, P. R. Beatty, and E. Harris. 2008. Antibodies play a greater role than immune cells in heterologous protection against secondary dengue virus infection in a mouse model. Virology 380296-303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kyle, J. L., P. R. Beatty, and E. Harris. 2007. Dengue virus infects macrophages and dendritic cells in a mouse model of infection. J. Infect. Dis. 1951808-1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee, E., R. A. Hall, and M. Lobigs. 2004. Common E protein determinants for attenuation of glycosaminoglycan-binding variants of Japanese encephalitis and West Nile viruses. J. Virol. 788271-8280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee, E., C. E. Stocks, S. M. Amberg, C. M. Rice, and M. Lobigs. 2000. Mutagenesis of the signal sequence of yellow fever virus prM protein: enhancement of signalase cleavage in vitro is lethal for virus production. J. Virol. 7424-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee, E., P. J. Wright, A. Davidson, and M. Lobigs. 2006. Virulence attenuation of Dengue virus due to augmented glycosaminoglycan-binding affinity and restriction in extraneural dissemination. J. Gen. Virol. 872791-2801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leung, J. Y., G. P. Pijlman, N. Kondratieva, J. Hyde, J. M. Mackenzie, and A. A. Khromykh. 2008. Role of nonstructural protein NS2A in flavivirus assembly. J. Virol. 824731-4741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lindenbach, B. D., and C. M. Rice. 2001. Flaviviridae: the viruses and their replication, p. 991-1041. In D. M. Knipe, P. M. Howley, D. G. Griffin, R. A. Lamb, M. A. Martin, and B. Roizman (ed.), Fields virology, 4th ed., vol. 1. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lobigs, M., and E. Lee. 2004. Inefficient signalase cleavage promotes efficient nucleocapsid incorporation into budding flavivirus membranes. J. Virol. 78178-186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mandl, C. W., S. L. Allison, H. Holzmann, T. Meixner, and F. X. Heinz. 2000. Attenuation of tick-borne encephalitis virus by structure-based site-specific mutagenesis of a putative flavivirus receptor binding site. J. Virol. 749601-9609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mason, P. W., A. V. Shustov, and I. Frolov. 2006. Production and characterization of vaccines based on flaviviruses defective in replication. Virology 351432-443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mori, Y., T. Okabayashi, T. Yamashita, Z. Zhao, T. Wakita, K. Yasui, F. Hasebe, M. Tadano, E. Konishi, K. Moriishi, and Y. Matsuura. 2005. Nuclear localization of Japanese encephalitis virus core protein enhances viral replication. J. Virol. 793448-3458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakai, K., T. Okamoto, T. Kimura-Someya, K. Ishii, C. K. Lim, H. Tani, E. Matsuo, T. Abe, Y. Mori, T. Suzuki, T. Miyamura, J. H. Nunberg, K. Moriishi, and Y. Matsuura. 2006. Oligomerization of hepatitis C virus core protein is crucial for interaction with the cytoplasmic domain of E1 envelope protein. J. Virol. 8011265-11273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patkar, C. G., and R. J. Kuhn. 2008. Yellow fever virus NS3 plays an essential role in virus assembly independent of its known enzymatic functions. J. Virol. 823342-3352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Purtha, W. E., N. Myers, V. Mitaksov, E. Sitati, J. Connolly, D. H. Fremont, T. Hansen, and M. S. Diamond. 2007. Antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes protect against lethal West Nile virus encephalitis. Eur. J. Immunol. 371845-1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rossi, S. L., Q. Zhao, V. K. O'Donnell, and P. W. Mason. 2005. Adaptation of West Nile virus replicons to cells in culture and use of replicon-bearing cells to probe antiviral action. Virology 331457-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sa-Carvalho, D., E. Rieder, B. Baxt, R. Rodarte, A. Tanuri, and P. W. Mason. 1997. Tissue culture adaptation of foot-and-mouth disease virus selects viruses that bind to heparin and are attenuated in cattle. J. Virol. 715115-5123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shresta, S., J. L. Kyle, H. M. Snider, M. Basavapatna, P. R. Beatty, and E. Harris. 2004. Interferon-dependent immunity is essential for resistance to primary dengue virus infection in mice, whereas T- and B-cell-dependent immunity are less critical. J. Virol. 782701-2710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shresta, S., K. L. Sharar, D. M. Prigozhin, P. R. Beatty, and E. Harris. 2006. Murine model for dengue virus-induced lethal disease with increased vascular permeability. J. Virol. 8010208-10217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shrestha, B., and M. S. Diamond. 2004. Role of CD8+ T cells in control of West Nile virus infection. J. Virol. 788312-8321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shrestha, B., M. A. Samuel, and M. S. Diamond. 2006. CD8+ T cells require perforin to clear West Nile virus from infected neurons. J. Virol. 80119-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shustov, A. V., P. W. Mason, and I. Frolov. 2007. Production of pseudoinfectious yellow fever virus with two-component genome. J. Virol. 8111737-11748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Simmons, M., K. R. Porter, C. G. Hayes, D. W. Vaughn, and R. Putnak. 2006. Characterization of antibody responses to combinations of a dengue virus type 2 DNA vaccine and two dengue virus type 2 protein vaccines in rhesus macaques. J. Virol. 809577-9585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Suzuki, R., R. Fayzulin, I. Frolov, and P. W. Mason. 2008. Identification of mutated cyclization sequences that permit efficient replication of West Nile virus genomes: use in safer propagation of a novel vaccine candidate. J. Virol. 826942-6951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang, Y., M. Lobigs, E. Lee, and A. Mullbacher. 2003. CD8+ T cells mediate recovery and immunopathology in West Nile virus encephalitis. J. Virol. 7713323-13334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Whitehead, S. S., J. E. Blaney, A. P. Durbin, and B. R. Murphy. 2007. Prospects for a dengue virus vaccine. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5518-528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Widman, D. G., T. Ishikawa, R. Fayzulin, N. Bourne, and P. W. Mason. 2008. Construction and characterization of a second-generation pseudoinfectious West Nile virus vaccine propagated using a new cultivation system. Vaccine 262762-2771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yamshchikov, V. F., and R. W. Compans. 1993. Regulation of the late events in flavivirus protein processing and maturation. Virology 19238-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang, W., P. R. Chipman, J. Corver, P. R. Johnson, Y. Zhang, S. Mukhopadhyay, T. S. Baker, J. H. Strauss, M. G. Rossmann, and R. J. Kuhn. 2003. Visualization of membrane protein domains by cryo-electron microscopy of dengue virus. Nat. Struct. Biol. 10907-912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang, Y., J. Corver, P. R. Chipman, W. Zhang, S. V. Pletnev, D. Sedlak, T. S. Baker, J. H. Strauss, R. J. Kuhn, and M. G. Rossmann. 2003. Structures of immature flavivirus particles. EMBO J. 222604-2613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]