Abstract

Ataxia oculomotor apraxia 1 (AOA1) results from mutations in aprataxin, a component of DNA strand break repair that removes AMP from 5′ termini. Despite this, global rates of chromosomal strand break repair are normal in a variety of AOA1 and other aprataxin-defective cells. Here we show that short-patch single-strand break repair (SSBR) in AOA1 cell extracts bypasses the point of aprataxin action at oxidative breaks and stalls at the final step of DNA ligation, resulting in the accumulation of adenylated DNA nicks. Strikingly, this defect results from insufficient levels of nonadenylated DNA ligase, and short-patch SSBR can be restored in AOA1 extracts, independently of aprataxin, by the addition of recombinant DNA ligase. Since adenylated nicks are substrates for long-patch SSBR, we reasoned that this pathway might in part explain the apparent absence of a chromosomal SSBR defect in aprataxin-defective cells. Indeed, whereas chemical inhibition of long-patch repair did not affect SSBR rates in wild-type mouse neural astrocytes, it uncovered a significant defect in Aptx−/− neural astrocytes. These data demonstrate that aprataxin participates in chromosomal SSBR in vivo and suggest that short-patch SSBR arrests in AOA1 because of insufficient nonadenylated DNA ligase.

Oxidative stress is an etiological factor in many neurological diseases, including Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and Huntington's disease. One type of macromolecule damaged by reactive oxygen species is DNA, and oxidative damage to DNA has been suggested to be a significant factor in these and other neurological conditions (2). In particular, a number of rare hereditary neurodegenerative disorders have provided direct support for the notion that unrepaired DNA damage causes neural dysfunction. Not least of these are the recessive spinocerebellar ataxias, a number of which are associated with mutations in DNA damage response proteins (17). The archetypal DNA damage-associated spinocerebellar ataxia is ataxia-telangiectasia (A-T), in which mutations in ATM protein result in defects in the detection and signaling of DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) (3). A-T-like disorder is a related disease that exhibits neurological features similar to those of A-T, resulting from mutation of Mre11, a component of the MRN complex that operates in conjunction with ATM during DSB detection and signaling (28).

Two additional spinocerebellar ataxias are spinocerebellar ataxia with axonal neuropathy 1 (SCAN1) and ataxia oculomotor apraxia 1 (AOA1), in which the TDP1 and aprataxin proteins are mutated, respectively (9, 19, 27). Both TDP1 and aprataxin are components of the DNA strand break repair machinery (recently reviewed in references 6 and 24). Whereas SCAN1 is currently limited to nine individuals from a single family, AOA1 is one of the commonest recessive spinocerebellar ataxias. Aprataxin is a member of the histidine triad superfamily of nucleotide hydrolases/transferases and has been reported to remove phosphate and phosphoglycolate moieties from the 3′ termini of DNA strand breaks (26). Aprataxin can also remove AMP from a variety of ligands in vitro, including adenosine polyphosphates, AMP-lysine, AMP-NH2 (adenine monophosphoramidate), and adenylated DNA in which AMP is covalently attached to the 5′ terminus of a DNA single-strand break (SSB) or DSB (1, 16, 23, 25). To date, aprataxin activity is greatest on AMP-DNA, suggesting that this may be the physiological substrate of this enzyme.

In vitro, DNA strand breaks with 5′-AMP termini can arise from premature DNA ligase activity. DNA ligases adenylate 5′ termini at DNA breaks to enable nucleophilic attack of the resulting pyrophosphate bonds by 3′-hydroxyl termini, thereby resealing the breaks. However, DNA adenylation by DNA ligases can occur prematurely, before a 3′-hydroxyl terminus is available. Aprataxin reverses these premature DNA adenylation events, in vitro at least, effectively “resetting” the DNA ligation reaction to the beginning (1). Whether or not 5′-AMP arises in DNA in vivo or is a physiological substrate of aprataxin, however, is unknown. Moreover, attempts to measure DNA strand break repair rates in vivo are conflicting and have failed to identify a consistent defect in DNA SSB repair (SSBR) or DSB repair (DSBR) in AOA1 cells (14, 15, 20). It is thus not clear whether or not defects in DNA strand break repair can account for this neurodegenerative disease.

Here we have resolved the discrepancy between the requirements for aprataxin in vitro and in vivo by identifying the stage at which SSBR reactions fail in vitro and by carefully analyzing chromosomal SSBR rates in vivo. We show that short-patch SSBR reactions are defective in AOA1 cell extracts at the final step of DNA ligation, resulting in the accumulation of adenylated DNA nicks, and that this defect can be rescued in AOA1 extracts independently of aprataxin by addition of recombinant DNA ligase. We also find that treatment with aphidicolin, an inhibitor of DNA polymerase δ (Pol δ) and Pol ɛ, unveils a measurable defect in chromosomal SSBR in Aptx−/− primary neural astrocytes, suggesting that the adenylated nicks that arise from the short-patch repair defect can be channeled into long-patch repair in vivo. These data demonstrate that aprataxin participates in chromosomal SSBR and suggest that this process arrests in AOA1, at oxidative SSBs, due to insufficient levels of nonadenylated DNA ligase.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of adenylated DNA substrates.

Oligonucleotide duplexes containing an SSB with a 5′-AMP terminus and either a 1-bp gap with a 3′-phosphate terminus or a nick with a 3′-hydroxyl terminus were prepared as follows. A 25-mer (5′-GACATACTAACTTGAGCGAAACGGT) was labeled by phosphorylation with T4 PNK and [γ-32P]ATP and was annealed with a 43-mer (5′-CCGTTTCGCTCAAGTTAGTATGTCAAAGCAGGCTTCAACGGAT) and a 17-mer with a 3′-phosphate terminus (17-mer-P) (5′-TCCGTTGAAGCCTGCTT-P). The labeled 25-mer in this duplex was then either adenylated at the 5′ terminus by incubation with 1 U T4 DNA ligase at 30°C for 1 h in ligation buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 25 μg/μl bovine serum albumin, 1 mM ATP) or mock adenylated in the absence of T4 DNA ligase. The labeled adenylated 25-mer was then separated from the labeled nonadenylated 25-mer (and from the 17-mer and 43-mer) on a 15% denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) gel, excised, and eluted from the crushed gel in elution buffer (0.5 M ammonium acetate, 10 mM magnesium acetate, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]) overnight at room temperature. The eluted DNA was then ethanol precipitated. The labeled mock-adenylated 25-mer was purified in parallel. The labeled adenylated 25-mer was then reannealed with the 43-mer and either the 17-mer-P (containing a 3′ phosphate) or an 18-mer (5′-TCCGTTGAAGCCTGCTTT) to produce oligonucleotide duplexes harboring an adenylated SSB with either a 1-bp gap and a 3′-phosphate terminus or a nick with a 3′-hydroxyl terminus, respectively. To measure the repair of 3′ termini by PNK or gap filling by Pol β, the 17-mer-P or a 17-mer oligonucleotide lacking a 3′ phosphate, respectively, was labeled with T4 PNK (phosphatase dead) and [γ-32P]ATP and was annealed to the 25-mer and 43-mer. The substrate was either mock adenylated or adenylated as described above and was purified on a 15% native PAGE gel. The final substrate contained a 1-bp gap with a 5′ AMP and either a 3′ P or a 3′ OH.

Purification of recombinant human SSBR proteins.

Pol β was expressed in Escherichia coli and purified by anion and cation exchange as previously described (29), using a 1.6-ml Poros column on a Biocad Sprint chromatography system (Applied Biosystems, United Kingdom). His-tagged PNK and His-tagged DNA ligase IIIα (Lig3α) were expressed in the E. coli strain BL21(DE3) for 90 min at 20°C following addition of 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). PNK was purified by cation-exchange chromatography followed by immobilized metal chelate affinity chromatography (IMAC) as previously described (30). Lig3α was purified by IMAC as described previously (7), followed by cation exchange as described previously for PNK. His-tagged aprataxin was expressed from pB352 (8) in BL21(DE3) by addition of 1 mM IPTG and incubation at 30°C for 3 h. Aprataxin was purified by IMAC followed by cation exchange as described above for PNK and Lig3α.

Preparation of human lymphoblastoid cell extracts.

Total-cell extracts were prepared from 5 × 106 ConR2 (wild type [WT]) or Ap5 (AOA1) lymphoblastoid cells or from Aptx+/+ and Aptx−/− primary quiescent mouse astrocytes by lysis in 0.2 ml 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 100 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, and 1/100 dilution of protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma). The extracts were clarified by centrifugation, quantified with a Bio-Rad DC protein assay kit using bovine serum albumin as a standard, and then aliquoted and snap-frozen.

In vitro repair of adenylated SSB substrates by recombinant proteins.

For reactions employing recombinant human proteins, a 25 nM concentration of the indicated 32P-labeled substrate was incubated with the indicated concentrations of recombinant protein for 1 h at 30°C in 25 mM HEPES (pH. 8.0), 130 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 10 mM MgCl2, 100 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs), and 1 mM ATP unless otherwise indicated. Reactions were stopped by addition of 1/3 volume of formamide gel loading buffer, and reaction products were fractionated on 15% denaturing PAGE gels and analyzed by a phosphorimager.

For reactions employing cell extracts, 5 μg of extract from WT lymphoblastoid cells (ConR2) or AOA1 lymphoblastoid cells (Ap5) or from Aptx+/+ and Aptx−/− primary quiescent mouse astrocytes was incubated with a 100 nM concentration of the indicated 32P-labeled substrate for 1 h at 30°C in 25 mM HEPES (pH 8.0), 130 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, and, unless otherwise indicated, 10 mM MgCl2, 100 μM dNTPs, and 1 mM ATP. A 1,000-fold excess of a competitor oligonucleotide with an unrelated sequence and a 5′ phosphate (5′-P-TCTGCTAGCATCGATCCATG-3′) was added to reduce degradation of the labeled substrate by nonspecific nucleases. Reactions were stopped and products analyzed as described above.

Cell culture. (i) Human cells.

1BR3 cells are primary human fibroblasts, and ConR and ConR2 cells are lymphoblastoid cells, all from unrelated normal individuals. fAp1 and fAp4 cells are AOA1 primary fibroblasts, and Ap3 and Ap5 cells are AOA1 lymphoblasts. ConR, Con R2, fAp1, fAp4, Ap3, and Ap5 cells were kindly provided by Malcolm Taylor and, except for Ap5 and ConR2, have been described previously (8). Ap1, Ap3, and Ap4 cells harbor the homozygous APTX mutation W279X, which results in little or no aprataxin protein or activity (1, 8), and Ap5 cells harbor a genomic deletion of APTX (M. Taylor, unpublished data). Cells were cultured as described previously (8).

(ii) Primary mouse astrocytes.

Aptx−/− mice have been described previously (1). The generation and characterization of nestin-Cre conditional Xrcc1−/− mice will be described elsewhere. All animals were housed in individually ventilated cabinets and were maintained in accordance with the guidelines of the institutional animal care and ethical committee at the University of Sussex. Mouse astrocytes were prepared from postnatal day 3 (P3) to P4 brains. Cortices were dissociated by passage through a 5-ml pipette, and cells were resuspended in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium and Ham's F-12 nutrient mixture (1:1; Gibco-BRL) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1× Glutamax, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 20 ng/ml epidermal growth factor (Sigma). Primary astrocytes were established in Primeria T-25 tissue culture flasks (Falcon) at 37°C in a humidified oxygen-regulated (9%) incubator. The culture medium was changed after 3 days, and astrocyte monolayers reached confluence 3 days later. The purity of the astrocyte cultures was confirmed by immunofluorescence using an anti-GFAP antibody (Sigma).

Alkaline comet assays.

Cells (∼3 × 105/sample) were incubated with 75 μM (mouse astrocytes), 50 μM (human lymphoblastoid cells), or 75 μM (primary human fibroblasts) H2O2 for 10 min on ice or with the indicated doses of methyl methanesulfonate (MMS) for 10 min at 37°C. Where indicated, cells were then incubated in complete medium for the indicated repair periods at 37°C. To inhibit long-patch DNA polymerases, cells were incubated with 50 μM aphidicolin (Sigma) in complete medium for 30 min at 37°C. Cells were then either mock treated or treated with H2O2 or MMS as described above in the continued presence or absence of aphidicolin, as appropriate. Chromosomal DNA strand breaks were then measured using alkaline comet assays as previously described (5). Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software.

RESULTS

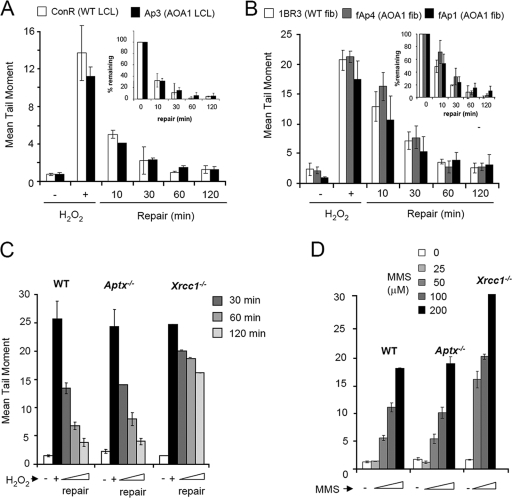

Aprataxin interacts with the SSBR scaffold protein XRCC1, raising the possibility that a defect in chromosomal SSBR underlies the neuropathology of this disease. However, evidence for a defect in SSBR in aprataxin-defective AOA1 cells is conflicting (14, 15, 20). To resolve this issue, we employed alkaline comet assays to compare chromosomal SSBR rates in a variety of different aprataxin-defective cell types. It should be noted that while alkaline comet assays measure both SSBs and DSBs, these assays primarily measure SSBs following short periods of treatment with H2O2 or MMS, because these agents induce several orders of magnitude more SSBs than DSBs (4, 18). In contrast to the findings of a previous report (15), we failed to observe a significant difference in chromosomal SSBR rates between either lymphoblastoid cells (Fig. 1A) or primary fibroblasts (Fig. 1B) from AOA1 patients and those from normal individuals following H2O2-induced oxidative stress. Because individual genetic variability might mask differences in SSBR rates, we also compared chromosomal SSBR in quiescent primary astrocytes from Aptx−/− mice and isogenic Aptx+/+ littermate controls. Astrocytes were chosen because they are neural in origin and thus better reflect the type of cells affected in AOA1. However, SSBR rates were similar in Aptx+/+ and Aptx−/− astrocytes following treatment with H2O2 (Fig. 1C). Aptx+/+ and Aptx−/− astrocytes also accumulated SSBs at similar rates during incubation with the alkyating agent MMS, suggesting that the rate of SSB rejoining during DNA base excision repair is also normal in Aptx−/− cells (Fig. 1D). In contrast, astrocytes lacking the core SSBR factor Xrcc1 exhibited greatly reduced SSBR rates following treatment with either H2O2 or MMS (Fig. 1C and D). It should be noted that we also observed normal SSBR kinetics in Aptx−/− postmitotic cerebellar granule neurons (data not shown). We conclude from these experiments that AOA1 and other aprataxin-defective cells lack a measurable defect in the global rate of chromosomal SSBR.

FIG. 1.

Normal rates of chromosomal SSBR in cells lacking aprataxin. (A) AOA1 lymphoblastoid cells were incubated in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 50 μM H2O2 (15 min on ice), followed by incubation in a drug-free medium for the indicated repair period at 37°C. Chromosomal DNA strand breaks were then measured by alkaline comet assays. (B) AOA1 primary fibroblasts were treated in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 75 μM H2O2 (15 min on ice) and processed as described for panel A. Insets in panels A and B contain the same data as in the main panels but plotted as percent damage remaining. (C) WT, Aptx−/−, and Xrcc1−/− primary quiescent astrocytes were incubated in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 75 μM H2O2 (10 min on ice), followed by incubation in a drug-free medium for the indicated repair period at 37°C. Chromosomal DNA strand breaks were then measured by alkaline comet assays. (D) WT, Aptx−/−, and Xrcc1−/− primary quiescent astrocytes were incubated in the absence (−) or presence of the indicated concentration of MMS (10 min at 37°C). Chromosomal DNA strand breaks were then measured by alkaline comet assays.

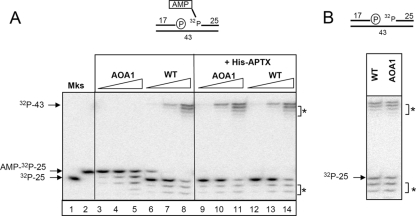

In contrast to the findings of cellular SSBR assays, protein extracts from Aptx−/− astrocytes and Aptx− chicken DT40 cells are unable to support short-patch repair of adenylated oxidative SSBs in vitro (1). To resolve this discrepancy, we examined whether this was also true in AOA1 lymphoblastoid cell extracts. To measure short-patch SSBR, we employed an oligonucleotide duplex harboring a 1-bp gap with 3′-phosphate termini, a substrate that mimics one of the commonest types of oxidative SSB arising in cells (Fig. 2A, top). The SSB also possesses a 5′ AMP and is therefore a substrate for aprataxin. In agreement with previous experiments with neural extracts (1), WT extracts efficiently removed AMP from 5′ termini and repaired the SSBs, as indicated by the respective appearance of the 32P-labeled 25-mer and the 32P-labeled 43-mer (Fig. 2A, lanes 6 to 8). In contrast, AOA1 extracts did not (Fig. 2A, lanes 3 to 5). Importantly, SSBR was proficient in AOA1 extracts if the initial SSB lacked 5′ AMP (Fig. 2B). A number of truncated oligonucleotide fragments were generated by nonspecific nucleolytic activity in these experiments, which represented degradation of the 3′ terminus of the 32P-labeled 25-mer. However, this activity did not account for the short-patch repair defect in AOA1 cell extracts, which was fully complemented by the addition of recombinant aprataxin (Fig. 2A, lanes 9 to 11). The appearance of ligated product in these experiments was dependent on the presence of dNTPs, confirming that these experiments measured gap repair rather than ligation across the 1-bp gap (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Aprataxin-dependent short-patch SSBR of 5′-AMP SSBs in AOA1 lymphoblastoid extracts. (A) Defective short-patch SSBR in AOA1 extracts and its complementation by recombinant aprataxin. (Top) Cartoon of the oligonucleotide duplex employed for these experiments, containing a 1-bp gap, a 3′-phosphate terminus, and a 5′-AMP terminus. The 5′ phosphate to which AMP is covalently linked is labeled with 32P. The position of this label restricts the assay to measurements of short-patch repair events only. Nucleotide lengths are shown. (Bottom) Portions (0.1 μg, 1.0 μg, or 5.0 μg) of either WT (ConR2) or AOA1 (Ap5) cell extracts were incubated for 60 min at 30°C with a 32P-labeled 5′-AMP SSB substrate (25 nM) in the absence (left) or presence (right) of recombinant human aprataxin (APTX) (100 nM). Reaction products were fractionated and detected as described in Materials and Methods. The 32P-labeled 25-mer containing (AMP-32P-25) or lacking (32P-25) 5′ AMP was fractionated in parallel for size markers (Mks). The position of the repaired 32P-labeled 43-mer is also indicated. Asterisks indicate nonspecific nucleolytic products. (B) Normal short-patch repair of SSBs lacking 5′ AMP in AOA1 cell extracts. (Top) Cartoon of the oligonucleotide duplex employed for these experiments, containing a 1-bp gap, a 3′-phosphate terminus, and a normal 32P-labeled 5′-phosphate terminus. WT (ConR2) or AOA1 (Ap5) cell extracts (5 μg) were incubated for 60 min at 30°C with a 32P-labeled SSB substrate lacking 5′ AMP (100 nM). Reaction products were fractionated and detected as described in Materials and Methods.

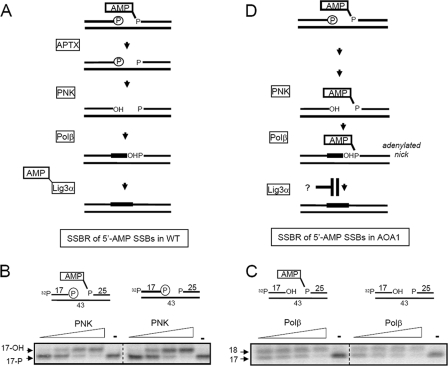

The predicted pathway for short-patch repair of SSBs harboring 5′ AMP in WT cells is depicted in Fig. 3A. It was considered likely that this pathway arrests in AOA1 extracts at the very beginning, prior to 3′-DNA end processing by PNK and/or DNA gap filling by Pol β, because the presence of AMP at the 5′ terminus might occlude access to the 3′ terminus. Surprisingly, however, the 3′-phosphatase activity of PNK was similar irrespective of whether the SSB possessed 5′ AMP or not, under conditions in which PNK was limiting (Fig. 3B). Similar results were observed for DNA gap filling by Pol β, with similar amounts of the 32P-labeled 17-mer converted into a 32P-labeled 18-mer irrespective of the presence or absence of 5′ AMP (Fig. 3C). These experiments suggested that neither PNK nor Pol β activity is affected by the presence of 5′ AMP at these time points, and thus short-patch SSBR might fail in AOA1 extracts at the final step of DNA ligation, resulting in the accumulation of adenylated DNA nicks (Fig. 3D).

FIG. 3.

Removal of 5′ AMP by aprataxin is not required for end processing by PNK or gap filling by Pol β. (A) Cartoon of aprataxin-dependent short-patch repair of adenylated SSBs in WT cells. (B) 5′ AMP does not affect processing of 3′-phosphate termini by PNK. An SSB substrate (25 nM) lacking or containing 5′ AMP as indicated (top) was incubated either with 25 nM, 50 nM, 125 nM, or 250 nM recombinant human PNK or without PNK (−) for 1 h at 30°C. Reaction products were fractionated by denaturing PAGE and detected by phosphorimaging. Note that the 5′ terminus of the 17-mer is labeled with 32P in these experiments to allow detection of 3′ end processing. The position of the 17-mer harboring 3′ phosphate (17-P) or 3′ hydroxyl (3′-OH) is indicated. (C) 5′ AMP does not affect gap filling by Pol β. An SSB substrate (25 nM) lacking or containing 5′ AMP as indicated (top) was incubated either with 5 nM, 15 nM, 30 nM, or 100 nM purified recombinant human Pol β or without Pol β (−) for 1 h at 30°C. Reaction products were fractionated by denaturing PAGE and detected by phosphorimaging. The positions of the 17-mer and 18-mer are indicated as markers. (D) Cartoon depicting APTX-independent repair of adenylated SSBs in AOA1. Note the hypothetical blockage of this process at the final step of DNA ligation.

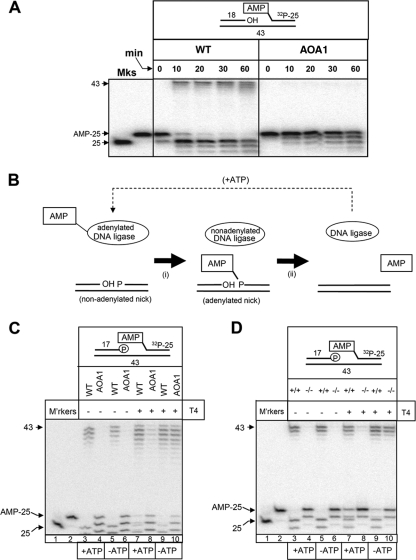

To confirm this hypothesis, we compared WT and AOA1 extracts for their abilities to ligate adenylated nicks. Indeed, whereas adenylated nicks were efficiently ligated by extracts from WT cells, they remained largely unligated in reaction mixtures containing AOA1 cell extracts (Fig. 4A). The finding that short-patch repair in AOA1 arrests during DNA ligation is surprising, because adenylated nicks are normal intermediates of DNA ligation and are normally rapidly resealed by nonadenylated DNA ligase (11). Normally, the nonadenylated DNA ligase required for this purpose is created during, and tightly coupled with, adenylation of the 5′ terminus of the break by an adenylated DNA ligase (Fig. 4B). However, in the absence of aprataxin, DNA nicks may accumulate in a preadenylated state and therefore require preexisting pools of nonadenylated DNA ligase. While both nonadenylated and adenylated DNA ligases exist in cells, the former may be very limited because the readenylation of DNA ligases by cellular ATP is very rapid. Consequently, we reasoned that the DNA ligation defect in AOA1 may reflect insufficient cellular levels of nonadenylated DNA ligase. To test this hypothesis, we examined the impact of supplementing short-patch SSBR reaction mixtures in AOA1 cell extracts and Aptx−/− mouse neural astrocyte extracts with recombinant DNA ligase. Strikingly, addition of T4 ligase restored short-patch SSBR efficiency in both AOA1 cell extracts and Aptx−/− neural cell extracts to a level similar to that observed in WT extracts (Fig. 4C and D, compare lanes 6 and 10). Importantly, complementation was more efficient in the absence of ATP than in its presence, supporting the notion that it was the nonadenylated subfraction of T4 ligase that was responsible for complementation (Fig. 4C and D, compare lanes 8 and 10). Similar results were observed for AOA1 cell extracts if T4 ligase was replaced with human DNA ligase 3α, albeit to a lesser extent (Fig. 5A).

FIG. 4.

Short-patch SSBR fails in AOA1 due to insufficient levels of nonadenylated DNA ligase. (A) AOA1 cell extracts cannot efficiently ligate adenylated DNA nicks. Total WT (ConR2) or AOA1 (Ap5) lymphoblastoid cell extracts (6.25 μg) were incubated with a 32P-labeled adenylated nicked substrate (25 nM) (top) for the indicated times at 30°C. Reaction products were fractionated by denaturing PAGE and detected by phosphorimaging. A 32P-labeled 25-mer containing 5′ AMP (AMP-25) and one lacking 5′ AMP were fractionated for size markers (Mks). The position of the 43-mer ligated product is indicated. (B) Cartoon depicting ligation of a nonadenylated DNA nick by DNA ligase. (i) An adenylated DNA ligase molecule transfers AMP to the 5′-phosphate terminus of a DNA nick, resulting in an adenylated nick and a nonadenylated ligase molecule. (ii) The nonadenylated DNA ligase molecule rapidly catalyzes a nucleophilic attack of the pyrophosphate bond linking AMP to DNA, resulting in nick ligation and the release of AMP. The nonadenylated DNA ligase molecule is readenylated (dashed arrow) in readiness for the next ligation event. (C) Complementation of the SSBR defect in AOA1 lymphoblastoid extracts by recombinant T4 DNA ligase. Total WT (ConR2) or AOA1 (Ap5) lymphoblastoid cell extracts (5 μg) were incubated with a 32P-labeled 5′-AMP SSB substrate (25 nM) for 1 h at 30°C in the presence or absence of 1 mM ATP and/or 2 U of T4 DNA ligase, as indicated. Reaction products were fractionated by denaturing PAGE and detected by phosphorimaging. The positions of the 32P-labeled 43-mer reaction product and the 32P-labeled 25-mer containing or lacking 5′ AMP are indicated. M'rkers, markers. (D) Complementation of the SSBR defect in Aptx−/− primary astrocyte extracts by recombinant T4 DNA ligase. Aptx+/+ (+/+) or Aptx−/− (−/−) mouse astrocyte extracts (5 μg) were incubated with a 32P-labeled 5′-AMP SSB substrate (25 nM) for 1 h at 30°C in the presence or absence of 1 mM ATP and/or 2 U of T4 DNA ligase, as indicated. Reaction products were fractionated by denaturing PAGE and detected by phosphorimaging. The positions of the 32P-labeled 43-mer reaction product and the 32P-labeled 25-mer containing or lacking 5′ AMP are indicated.

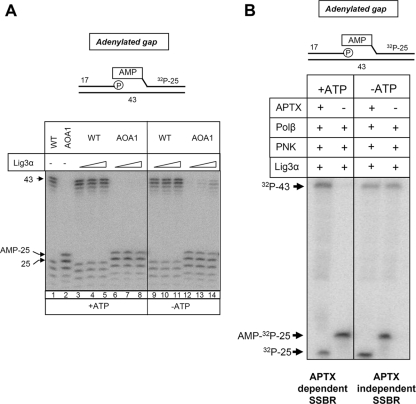

FIG. 5.

Complementation of the SSBR defect in AOA1 lymphoblastoid cell extracts by recombinant human Lig3α and reconstitution of aprataxin-independent SSBR with recombinant human proteins. (A) Complementation of the SSBR defect in AOA1 lymphoblastoid cell extracts by recombinant DNA ligase IIIα (Lig3α). Total WT or AOA1 lymphoblastoid cell extracts (5 μg) were incubated with a 32P-labeled 5′-AMP SSB (100 nM) substrate for 1 h at 30°C in the presence or absence of 1 mM ATP and/or 8 nM, 24 nM, or 72 nM Lig3α, as indicated. (B) Reconstitution of aprataxin-independent SSBR with recombinant human proteins. A 5′-AMP SSB substrate (60 nM) was incubated with 250 nM recombinant PNK, 100 nM Pol β, and 80 nM Lig3α in the presence or absence of 100 nM aprataxin (APTX) and 1 mM ATP, as indicated, for 1 h at 30°C. Reaction products were fractionated by denaturing PAGE and detected by phosphorimager.

The data described above suggest that short-patch repair of some adenylated SSBs can occur independently of aprataxin if sufficient nonadenylated DNA ligase is available. To confirm this idea, we attempted to reconstitute this aprataxin-independent SSBR pathway using recombinant proteins. As expected, the repair of adenylated gaps by PNK, Pol β, and Lig3α was dependent on aprataxin in the presence of ATP, conditions under which Lig3α is largely adenylated (Fig. 5B). However, in the absence of ATP, short-patch repair of 5′-AMP SSBs occurred independently of aprataxin. Taken together, these experiments indicate that short-patch repair arrests in AOA1 cell extracts at the final step of DNA ligation, due to insufficient levels of nonadenylated DNA ligase.

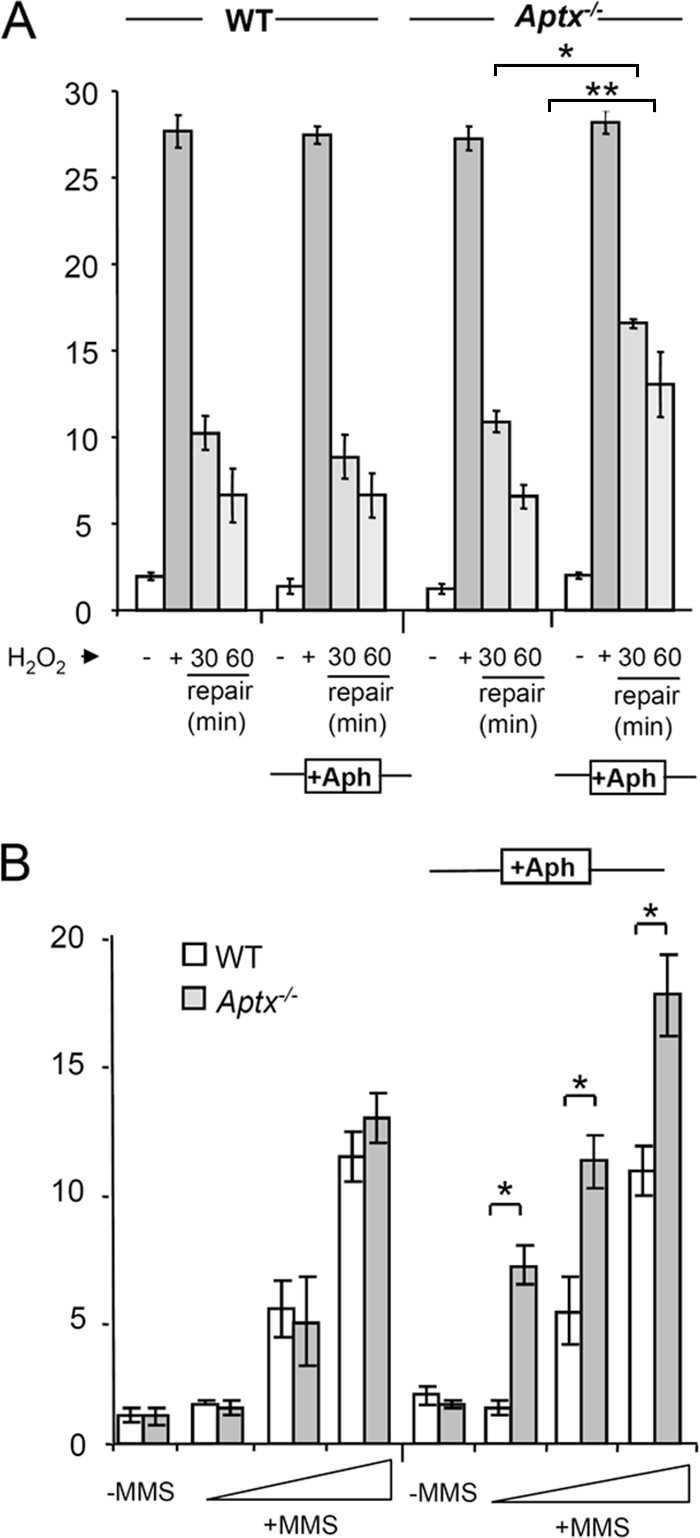

Importantly, the finding that short-patch repair failed during DNA ligation provides a possible explanation for the absence of a measurable defect in chromosomal SSBR in AOA1, following oxidative stress. This is because adenylated DNA nicks might be channeled into long-patch SSBR reactions, during which the adenylated 5′ terminus is displaced by extended DNA gap filling and then clipped off nucleolytically, avoiding the requirement for either aprataxin or preexisting pools of nonadenylated DNA ligase. While our in vitro assay was not capable of measuring long-patch repair reactions, this process might operate efficiently at adenylated nicks within a chromosomal context. To examine this possibility, we compared chromosomal SSBR rates in WT and Aptx−/− quiescent mouse neural astrocytes in the presence and absence of aphidicolin, an inhibitor of the DNA polymerases Pol δ and Pol ɛ, which are implicated in long-patch repair reactions (10, 13, 22). Strikingly, whereas aphidicolin did not measurably reduce SSBR rates in WT astrocytes following H2O2 treatment, it significantly slowed SSBR in Aptx−/− astrocytes (Fig. 6A). Aphidicolin also selectively slowed short-patch base excision repair in AOA1 cells, as indicated by the accumulation of higher steady-state levels of chromosomal DNA strand breaks in Aptx−/− astrocytes than in WT astrocytes during short incubations with the DNA-alkylating agent MMS (Fig. 6B). The fact that SSBR in Aptx−/− cells was slowed rather than prevented by aphidicolin most likely reflects the fact that only a subset of H2O2- and MMS-induced SSBs possess adenylated 5′ termini. Nevertheless, the presence of a measurable defect in chromosomal SSBR in Aptx−/− cells indicates that a significant fraction of endogenous SSBs arising from oxidative stress and DNA base damage are substrates for aprataxin.

FIG. 6.

Defective short-patch SSBR in quiescent primary Aptx−/− mouse neural cells. (A) Quiescent WT and Aptx−/− mouse astrocytes were either left untreated (−) or treated with 75 μM H2O2 for 10 min on ice (+) and, where indicated, then incubated in drug-free medium for 30 or 60 min. Where indicated (+Aph), cells were preincubated with 50 μM aphidicolin for 30 min at 37°C, and repair was conducted in the continued presence of aphidicolin. Chromosomal DNA strand breaks were then quantified by alkaline comet assays. Each bar represents the average mean tail moment from three independent experiments (error bars, ±1 standard deviation). Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (*, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01). (B) Quiescent WT and Aptx−/− mouse astrocytes were either left untreated (−) or treated with 25, 50, or 100 μM MMS for 10 min at 37°C with (+Aph) or without preincubation with 50 μM aphidicolin. Chromosomal DNA strand breaks were then quantified by alkaline comet assays. Each bar represents the average mean tail moment from three independent experiments (error bars, ±1 standard deviation). Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (*, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01).

In summary, we demonstrate here that aprataxin is required for SSBR in vivo and suggest that short-patch SSBR is defective in AOA1 cells, at oxidative SSBs, due to insufficient levels of nonadenylated DNA ligase.

DISCUSSION

AOA1 is one of the commonest recessive hereditary spinocerebellar ataxias identified to date. This disease results from mutations in aprataxin, a component of the DNA strand break repair machinery that removes AMP from 5′ termini during short-patch SSBR reactions in vitro (1, 9, 19). However, whether or not aprataxin is required for chromosomal DNA strand break repair in vivo is unclear. This is because the occurrence of DNA strand breaks with 5′ AMP has not yet been demonstrated. Moreover, attempts to detect a chromosomal DNA repair defect in AOA1 cells have proved conflicting and unclear (14, 15, 20). To resolve the latter issue, we carefully measured chromosomal SSBR rates in a variety of aprataxin-defective cell lines, including genetically matched WT and Aptx−/− quiescent neural cells. These experiments revealed that the overall rate of SSBR is normal in aprataxin-defective cells. Notably, we also failed to detect reduced rates of DSBR in AOA1 (unpublished observations).

To resolve the discrepancy between the requirement for aprataxin for SSBR in vitro versus that in vivo, we identified the stage at which short-patch SSBR fails in AOA1 in vitro. Notably, 3′-DNA end processing and DNA gap filling occurred normally during SSBR in the absence of aprataxin, despite the persistence of AMP on the 5′ terminus. However, SSBR reactions subsequently stalled at the final step of DNA ligation, resulting in the accumulation of adenylated DNA nicks. This was surprising, because adenylated DNA nicks are normal, indeed prerequisite, intermediates of DNA ligation reactions, requiring only nonadenylated DNA ligase to reseal the breaks. We therefore reasoned that DNA ligation might fail in AOA1 cell extracts because of insufficient levels of nonadenylated DNA ligase. This would be consistent with the notion that while DNA ligases exist in both adenylated and nonadenylated states, the former predominates in cells because of the cellular ATP concentration. This would not pose a problem in WT cells, in which aprataxin activity ensures that DNA nicks arising during SSBR are not preadenylated and thus are substrates for adenylated DNA ligase. However, in AOA1 cells, DNA nicks can arise in a preadenylated state during SSBR which thus require nonadenylated DNA ligase. In short, we propose that while all cells possess low levels of nonadenylated ligase, due to the rapid adenylation of free ligase molecules by cellular ATP, only in aprataxin-defective cells do preadenylated nicks arise at a level that exceeds the availability of nonadenylated ligase.

Confirmation that short-patch SSBR fails in AOA1 due to insufficient levels of nonadenylated DNA ligase emerged from our finding that addition of recombinant T4 DNA ligase or human Lig3α restored short-patch SSBR in AOA1 extracts and Aptx−/− quiescent astrocyte extracts in the absence of aprataxin. Importantly, complementation was more efficient if ATP was omitted from the reaction mixtures, supporting the notion that the complementing factor was nonadenylated DNA ligase. This may also explain the apparent difference between the abilities of T4 DNA ligase and Lig3α to complement the defect (compare Fig. 4C and 5A), since it is likely that the relative amounts of nonadenylated ligase present in the two DNA ligase preparations were different.

The finding that adenylated nicks accumulate during short-patch SSBR in AOA1 provides a possible explanation for the normal rate of chromosomal SSBR observed in this disease. This is because adenylated nicks can be channeled into long-patch SSBR. In this pathway, damaged 5′ termini are displaced as a single-stranded flap during gap filling from the 3′ terminus and cleaved off by Flap endonuclease 1 (FEN1) (reviewed in reference 12). This process would not be detected by the short-patch repair assays employed in the current work, because oligonucleotide duplexes of the type employed here are not good substrates for long-patch repair reactions and because cleavage of the single-strand flap would remove the 32P label in our substrates. However, to determine whether long-patch repair might compensate for the loss of short-patch repair in aprataxin-defective cells, we exploited the observation that long-patch SSBR employs the aphidicolin-sensitive DNA polymerases Pol δ and/or Pol ɛ (10, 13, 22). Because inhibition of Pol δ and/or Pol ɛ also prevents DNA replication during S phase and can thus impact DNA metabolism independently of long-patch SSBR, we employed quiescent primary astrocytes for these experiments. Strikingly, whereas preincubation with aphidicolin did not affect SSBR rates in WT cells, it revealed a significant chromosomal SSBR defect in Aptx−/− primary quiescent astrocytes following treatment with either H2O2 or MMS. SSBR was slowed rather than prevented by aphidicolin, perhaps reflecting the fact that only a subset of DNA strand breaks induced by these agents possess 5′-AMP termini. Alternatively, it is possible that Aptx−/− quiescent astrocytes possess additional, partially overlapping SSBR pathways. Nevertheless, these data demonstrate, for the first time, the involvement of aprataxin in chromosomal SSBR in vivo.

It remains to be determined whether long-patch repair can also compensate for defective short-patch repair in AOA1 cells, as appears to be the case in Aptx−/− mouse neural cells. However, if this is the case, why do aprataxin mutations result in disease? One possibility is that a subset of SSBs arise at which long-patch repair cannot operate. For example, it is possible that aprataxin is also required to repair specific types of damaged 3′ termini (26). Long-patch repair would be unable to operate at such breaks, because no 3′-hydroxyl primer terminus is available for DNA gap filling. Alternatively, since aprataxin is associated with the DSBR machinery (8), it is possible that unrepaired DSBs might account for AOA1. It should be noted, however, that we have so far failed to detect a DSBR defect in AOA1 or Aptx−/− cells (unpublished observations). Finally, it is possible that long-patch repair is not operative or is attenuated in the specific cell types that are affected in AOA1. For example, a number of replication-associated proteins, including several of those implicated in long-patch repair, are downregulated in certain differentiated cell types (21). Thus, it will now be of interest to expand the experiments described in this study to other cell types, including those neural cell types most likely affected in AOA1.

Acknowledgments

We thank LiMei Ju and Poorvi Patel for technical assistance and Malcolm Taylor for the provision of AOA1 lymphoblastoid cells.

This work was funded by MRC, BBSRC, and European Community (Integrated Project DNA repair [LSHG-CT-2005-512113]) grants to K.W.C. P.J.M. is funded by grants from the NIH and ALSAC of SJCRH. S.F.E.-K. is funded by the Wellcome Trust (grant 085284).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 December 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahel, I., U. Rass, S. F. El-Khamisy, S. Katyal, P. M. Clements, P. J. McKinnon, K. W. Caldecott, and S. C. West. 2006. The neurodegenerative disease protein aprataxin resolves abortive DNA ligation intermediates. Nature 443713-716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barzilai, A., S. Biton, and Y. Shiloh. 2008. The role of the DNA damage response in neuronal development, organization and maintenance. DNA Repair (Amsterdam) 71010-1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biton, S., A. Barzilai, and Y. Shiloh. 2008. The neurological phenotype of ataxia-telangiectasia: solving a persistent puzzle. DNA Repair (Amsterdam) 71028-1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradley, M. O., and K. W. Kohn. 1979. X-ray induced DNA double strand break production and repair in mammalian cells as measured by neutral filter elution. Nucleic Acids Res. 7793-804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breslin, C., P. M. Clements, S. F. El-Khamisy, E. Petermann, N. Iles, and K. W. Caldecott. 2006. Measurement of chromosomal DNA single-strand breaks and replication fork progression rates. Methods Enzymol. 409410-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caldecott, K. W. 2008. Single-strand break repair and genetic disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 9619-631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caldecott, K. W., S. Aoufouchi, P. Johnson, and S. Shall. 1996. XRCC1 polypeptide interacts with DNA polymerase β and possibly poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase, and DNA ligase III is a novel molecular ‘nick-sensor’ in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 244387-4394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clements, P. M., C. Breslin, E. D. Deeks, P. J. Byrd, L. Ju, P. Bieganowski, C. Brenner, M. C. Moreira, A. M. Taylor, and K. W. Caldecott. 2004. The ataxia-oculomotor apraxia 1 gene product has a role distinct from ATM and interacts with the DNA strand break repair proteins XRCC1 and XRCC4. DNA Repair (Amsterdam) 31493-1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Date, H., O. Onodera, H. Tanaka, K. Iwabuchi, K. Uekawa, S. Igarashi, R. Koike, T. Hiroi, T. Yuasa, Y. Awaya, T. Sakai, T. Takahashi, H. Nagatomo, Y. Sekijima, I. Kawachi, Y. Takiyama, M. Nishizawa, N. Fukuhara, K. Saito, S. Sugano, and S. Tsuji. 2001. Early-onset ataxia with ocular motor apraxia and hypoalbuminemia is caused by mutations in a new HIT superfamily gene. Nat. Genet. 29184-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DiGiuseppe, J. A., and S. L. Dresler. 1989. Bleomycin-induced DNA repair synthesis in permeable human fibroblasts: mediation of long-patch and short-patch repair by distinct DNA polymerases. Biochemistry 289515-9520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellenberger, T., and A. E. Tomkinson. 2008. Eukaryotic DNA ligases: structural and functional insights. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 77313-338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fortini, P., and E. Dogliotti. 2007. Base damage and single-strand break repair: mechanisms and functional significance of short- and long-patch repair subpathways. DNA Repair (Amsterdam) 6398-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goscin, L. P., and J. J. Byrnes. 1982. DNA polymerase delta: one polypeptide, two activities. Biochemistry 212513-2518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gueven, N., O. J. Becherel, A. W. Kijas, P. Chen, O. Howe, J. H. Rudolph, R. Gatti, H. Date, O. Onodera, G. Taucher-Scholz, and M. F. Lavin. 2004. Aprataxin, a novel protein that protects against genotoxic stress. Hum. Mol. Genet. 131081-1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gueven, N., P. Chen, J. Nakamura, O. J. Becherel, A. W. Kijas, P. Grattan-Smith, and M. F. Lavin. 2007. A subgroup of spinocerebellar ataxias defective in DNA damage responses. Neuroscience 1451418-1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kijas, A. W., J. L. Harris, J. M. Harris, and M. F. Lavin. 2006. Aprataxin forms a discrete branch in the HIT (histidine triad) superfamily of proteins with both DNA/RNA binding and nucleotide hydrolase activities. J. Biol. Chem. 28113939-13948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lavin, M. F., N. Gueven, and P. Grattan-Smith. 2008. Defective responses to DNA single- and double-strand breaks in spinocerebellar ataxia. DNA Repair (Amsterdam) 71061-1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lundin, C., M. North, K. Erixon, K. Walters, D. Jenssen, A. S. Goldman, and T. Helleday. 2005. Methyl methanesulfonate (MMS) produces heat-labile DNA damage but no detectable in vivo DNA double-strand breaks. Nucleic Acids Res. 333799-3811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moreira, M. C., C. Barbot, N. Tachi, N. Kozuka, E. Uchida, T. Gibson, P. Mendonca, M. Costa, J. Barros, T. Yanagisawa, M. Watanabe, Y. Ikeda, M. Aoki, T. Nagata, P. Coutinho, J. Sequeiros, and M. Koenig. 2001. The gene mutated in ataxia-ocular apraxia 1 encodes the new HIT/Zn-finger protein aprataxin. Nat. Genet. 29189-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mosesso, P., M. Piane, F. Palitti, G. Pepe, S. Penna, and L. Chessa. 2005. The novel human gene aprataxin is directly involved in DNA single-strand-break repair. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 62485-491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Narciso, L., P. Fortini, D. Pajalunga, A. Franchitto, P. Liu, P. Degan, M. Frechet, B. Demple, M. Crescenzi, and E. Dogliotti. 2007. Terminally differentiated muscle cells are defective in base excision DNA repair and hypersensitive to oxygen injury. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10417010-17015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Niranjanakumari, S., and K. P. Gopinathan. 1993. Isolation and characterization of DNA polymerase epsilon from the silk glands of Bombyx mori. J. Biol. Chem. 26815557-15564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rass, U., I. Ahel, and S. C. West. 2007. Actions of aprataxin in multiple DNA repair pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 2829469-9474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rass, U., I. Ahel, and S. C. West. 2007. Defective DNA repair and neurodegenerative disease. Cell 130991-1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seidle, H. F., P. Bieganowski, and C. Brenner. 2005. Disease-associated mutations inactivate AMP-lysine hydrolase activity of aprataxin. J. Biol. Chem. 28020927-20931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takahashi, T., M. Tada, S. Igarashi, A. Koyama, H. Date, A. Yokoseki, A. Shiga, Y. Yoshida, S. Tsuji, M. Nishizawa, and O. Onodera. 2007. Aprataxin, causative gene product for EAOH/AOA1, repairs DNA single-strand breaks with damaged 3′-phosphate and 3′-phosphoglycolate ends. Nucleic Acids Res. 353797-3809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takashima, H., C. F. Boerkoel, J. John, G. M. Saifi, M. A. Salih, D. Armstrong, Y. Mao, F. A. Quiocho, B. B. Roa, M. Nakagawa, D. W. Stockton, and J. R. Lupski. 2002. Mutation of TDP1, encoding a topoisomerase I-dependent DNA damage repair enzyme, in spinocerebellar ataxia with axonal neuropathy. Nat. Genet. 32267-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taylor, A. M., A. Groom, and P. J. Byrd. 2004. Ataxia-telangiectasia-like disorder (ATLD)—its clinical presentation and molecular basis. DNA Repair (Amsterdam) 31219-1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taylor, R. M., C. J. Whitehouse, and K. W. Caldecott. 2000. The DNA ligase III zinc finger stimulates binding to DNA secondary structure and promotes end joining. Nucleic Acids Res. 283558-3563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Whitehouse, C. J., R. M. Taylor, A. Thistlethwaite, H. Zhang, F. Karimi-Busheri, D. D. Lasko, M. Weinfeld, and K. W. Caldecott. 2001. XRCC1 stimulates human polynucleotide kinase activity at damaged DNA termini and accelerates DNA single-strand break repair. Cell 104107-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]