Abstract

Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-BB is a well-known smooth muscle (SM) cell (SMC) phenotypic modulator that signals by binding to PDGF αα-, αβ-, and ββ-membrane receptors. PDGF-DD is a recently identified PDGF family member, and its role in SMC phenotypic modulation is unknown. Here we demonstrate that PDGF-DD inhibited expression of multiple SMC genes, including SM α-actin and SM myosin heavy chain, and upregulated expression of the potent SMC differentiation repressor gene Kruppel-like factor-4 at the mRNA and protein levels. On the basis of the results of promoter-reporter assays, changes in SMC gene expression were mediated, at least in part, at the level of transcription. Attenuation of the SMC phenotypic modulatory activity of PDGF-DD by pharmacological inhibitors of ERK phosphorylation and by a small interfering RNA to Kruppel-like factor-4 highlight the role of these two pathways in this process. PDGF-DD failed to repress SM α-actin and SM myosin heavy chain in mouse SMCs lacking a functional PDGF β-receptor. Importantly, PDGF-DD expression was increased in neointimal lesions in the aortic arch region of apolipoprotein C-deficient (ApoE−/−) mice. Furthermore, human endothelial cells exposed to an atherosclerosis-prone flow pattern, as in vascular regions susceptible to the development of atherosclerosis, exhibited a significant increase in PDGF-DD expression. These findings demonstrate a novel activity for PDGF-DD in SMC biology and highlight the potential contribution of this molecule to SMC phenotypic modulation in the setting of disturbed blood flow.

Keywords: shear stress, disturbed blood flow, smooth muscle myosin heavy chain, smooth muscle α-actin

atherosclerosis is a complex disease characterized by the accumulation of lipid and cholesterol deposits within the walls of blood vessels, as well as intimal proliferation and extracellular matrix deposition by phenotypically modulated smooth muscle (SM) cells (SMCs) (1). SMCs within human atherosclerotic lesions and experimental atherosclerosis exhibit a distinct morphological change compared with medial SMCs within the normal vessel wall (32). Along with this morphological change, phenotypically modulated SMCs exhibit decreased expression of a variety of contractile genes, including SM α-actin, SM myosin heavy chain (MHC), SM22α, smoothelin, and h1-calponin (32). Advanced atherosclerotic lesions are characterized by a large lipid and necrotic core covered by a fibrous cap, and the thickness and mechanical properties of these lesions are key determinants of the probability of plaque rupture (3, 12, 13), thrombosis, and subsequent acute myocardial infarction or stroke, the leading causes of death in developed countries (3, 12, 13). Although the precise factors and mechanisms that contribute to plaque rupture are poorly understood, a critical stabilizing factor is believed to be proliferation of and matrix deposition by SMC. In support of this notion, recent evidence suggests that unstable atherosclerotic lesions prone to rupture are characterized by cells expressing lower levels of SM α-actin, indicating a lack of SMCs and/or the preponderance of phenotypically modulated SMCs within these types of lesions (10, 22, 39). Thus an understanding of the factors and mechanisms that control the phenotypic state of SMCs within atherosclerotic lesions is of critical importance.

Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-BB is a secreted molecule known to decrease SMC gene expression (5, 8, 19, 42). PDGF-BB is a homodimer of two B subunits, which can bind to the PDGF αα-, αβ-, or ββ-receptor (37). After binding to the receptor and subsequent receptor dimerization, the receptor is autophosphorylated through intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity, which, in turn, propagates downstream signaling events, including phosphorylation of ERK and Elk-1 and induction of the potent SMC differentiation repressor gene Kruppel-like factor-4 (KLF-4) and transcription factor Sp1 (21, 26, 40, 42).

Recently, a novel member of the PDGF family, PDGF-DD (4), was discovered using bioinformatics approaches (4, 25). PDGF-DD is secreted as a latent disulfide-linked homodimer, which requires proteolytic cleavage between an NH2-terminal CUB domain and a COOH-terminal PDGF/VEGF homology domain (residues 258–370, also known as the core domain) for full activity (4, 11). Previous studies have demonstrated that PDGF-DD can be activated by urokinase-plasminogen activator in vitro (38).

Fluid shear stress is an important determinant of atherosclerotic lesion development (6, 43). Atherosclerotic lesions characteristically develop at branch points of arteries and bifurcations, where blood flow is complex and highly oscillatory and maintains a low time-average magnitude of shear stress (43). Although the mechanism is unclear, atherosclerosis-prone (atheroprone) shear stress is believed to be transduced into chemical mediators released by endothelial cells (ECs), which, in turn, influences the recruitment of other cell types, including SMCs, ultimately leading to the formation of atherosclerotic lesions (7). The importance of PDGF ββ-receptor signaling and PDGF-BB in this process has been documented, yet the role of PDGF-DD is virtually unexplored (33).

Here, we demonstrate that PDGF-DD, a PDGF ββ-receptor agonist, decreased the expression of multiple SMC genes, including SM α-actin, SM MHC, SM22α, and h1-calponin, and upregulated the expression of KLF-4, an effector of PDGF-BB-induced SMC marker gene suppression. Of particular importance, we demonstrate that ECs exposed to atheroprone flow patterns, as occur in vascular regions prone to the development of atherosclerosis, upregulated PDGF-DD expression, thus providing a potential mechanism for SMC phenotypic modulation in diseases associated with altered hemodynamic states.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Full-length and mature cleaved forms of recombinant human PDGF-DD were obtained from ZymoGenetics. U-0126 MEK1/2 inhibitor was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Plasmid DNA was prepared using Qiafilter MaxiPrep kits (Qiagen).

Cell culture, PDGF-DD treatment, and transient transfection.

Cultured rat aortic SMCs were grown to subconfluence, transiently transfected in insulin-free serum-free medium (IFSFM), and stimulated with PDGF-DD or the vehicle as previously described for PDGF-BB (8). These cells and the associated conditions are used routinely by our laboratory and consistently express all the SMC differentiation markers that have been identified.

Real-time RT-PCR.

Rat aortic SMCs or human coronary SMCs were treated with PDGF-DD as previously described for PDGF-BB (42). Briefly, subconfluent rat aortic SMCs were treated with IFSFM for 24 h to allow growth arrest and then with PDGF-DD for 24 h in IFSFM at 10 or 30 ng/ml. RNA was harvested, reverse transcribed, and quantified by real-time PCR as previously described (42). Each sample was quantified in duplicate, and each experiment was repeated a minimum of three times, with n = 3.

Mouse SMC harvest from floxed PDGF β-receptor mice and adenoviral infection.

Mouse SMCs were obtained from the thoracic aorta of four C57/Bl6 littermates by manual dissection under a Zeiss dissection microscope. They were plated and amplified in culture for six passages in DMEM with 20% FBS and then switched to DMEM with 10% serum for two further passages. The line was then divided into two parts: the first was infected with an adenovirus expressing Cre recombinase under the control of the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter at a multiplicity of infection of 75 for three passages, ∼5 days per infection; the second was infected in parallel with a control adenovirus with an empty cassette under the control of the CMV promoter. All animal use protocols were approved by The University of Virginia Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Cells were plated in 10% serum at a density of 1 × 104 cells/cm2 and allowed to grow to ∼75% confluency (∼24 h). Cells were then washed with Dulbecco's PBS and allowed to growth arrest in serum-free medium for 24 h. Cells were treated with vehicle, 50 ng/ml human PDGF-AA (Millipore), 50 ng/ml PDGF-BB (Millipore), or 30 ng/ml PDGF-DD (ZymoGenetics) for another 24 h before RNA was harvested in TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). The iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad) was used to synthesize 0.5 μg of cDNA from each sample. Gene expression for SM α-actin and SM MHC was determined by Bio-Rad quantitative PCR and normalized to expression values of 18S RNA.

Quantitative chromatin immunoprecipitation assay.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were performed as previously described (17). Antibodies included serum response factor (SRF; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), Elk-1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), acetylated histone H3 (acetyl-H3; Upstate), and acetylated histone H4 (acetyl-H4; Upstate). After immunoprecipitation, 1 ng of DNA from each treatment group was subjected to real-time PCR quantification.

EC-SMC coculture and flow apparatus.

The human EC-SMC coculture model has been described previously (15; also see supplemental information in the online version of this article). RNA was harvested and processed for real-time PCR (see above).

In vivo quantification of PDGF-DD expression.

Thirty-nine-week-old wild-type C57/Bl6 mice and age-matched apolipoprotein E-deficient (ApoE−/−) mice were euthanized, and aortas were perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde and dissected free. Tissue was embedded in paraffin, and 5-μm aortic sections were collected. Tissue was stained with antibodies to PDGF-D (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and MAC 2 (Accurate Chemicals, Westbury, NY). Coverslips were applied using Vectashield Hard Set mounting medium containing 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Images were acquired using a confocal microscope (model LSM 510-UV, Zeiss) and viewed using the Zeiss LSM 5 Image Browser. Cell counts were performed blindly on aortic arch and abdominal aorta sections from wild-type and ApoE−/− mice (n = 4). The ratio of PDGF-D-positive to DAPI-positive cells was calculated, and Student's t-test was performed to determine significance at the 0.05 level. Ratios >1 are due to sectioning artifacts, in which cell cytoplasms were present without their corresponding nuclei.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical significance was determined by using Student's t-test. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

PDGF-DD decreased expression of multiple SMC genes.

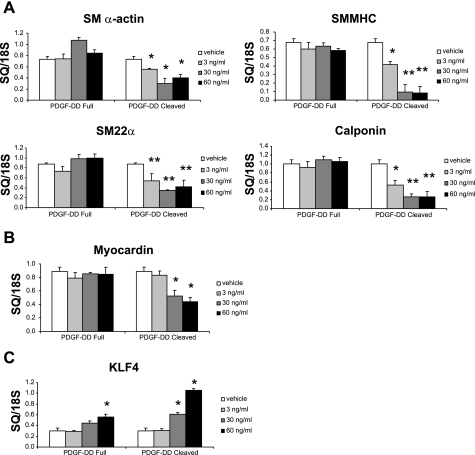

PDGF-BB is a well-known modulator of SMC phenotype and is an agonist at multiple receptors, including PDGF α/α-, α/β-, and β/β-receptors (37). PDGF-DD, a recently identified member of the PDGF family, also signals through the PDGF ββ-receptor (25, 34). Our initial aim was to determine whether PDGF-DD contains SMC phenotypic modulatory activity and whether cleavage is required for this activity. We treated rat aortic SMCs with increasing doses of the uncleaved form, as well as the mature cleaved form, of PDGF-DD. At 60 ng/ml, cleaved PDGF-DD decreased transcript levels of SM α-actin, SM MHC, h1-calponin, SM22α, and the potent SMC-selective transcription factor myocardin by 45%, 88%, 74%, 52%, and 50%, respectively (Fig. 1). The effects on SM α-actin and SM MHC expression were recapitulated in human coronary SMCs (see supplemental Fig. 1). Cleaved PDGF-DD also increased KLF-4 by 251% (Fig. 1). Interestingly, full-length PDGF-DD failed to significantly downregulate SM α-actin, SM MHC, h1-calponin, SM22α, and myocardin. The full-length ligand at 60 ng/ml induced KLF-4, but the response was greatly blunted compared with cleaved PDGF-DD (Fig. 1). These data demonstrate that the cleaved form of PDGF-DD is a selective and potent mediator of SMC phenotypic modulation.

Fig. 1.

Cleaved mature form of platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-DD decreased smooth muscle (SM) cell (SMC) gene expression in a dose-dependent manner. Growth-arrested subconfluent rat aortic SMCs were treated with the recombinant full-length PDGF-DD or the cleaved mature form of PDGF-DD (3–60 ng/ml). After 24 h, RNA was extracted and SMC genes were quantified by real-time PCR. A: real-time RT-PCR quantification of SMC genes in rat aortic SMCs demonstrates that the cleaved mature form of PDGF-DD potently repressed the SMC contractile genes SM α-actin, SM myosin heavy chain (MHC), SM22α, and h1-calponin. B: cleaved mature form of PDGF-DD also decreased myocardin expression in a dose-dependent manner as measured by real-time PCR. C: cleaved form of PDGF-DD increased expression of Kruppel-like factor-4 (KLF-4), a transcription factor implicated in repression of SMC genes. Full-length form of PDGF-DD failed to alter expression of SM α-actin, SM MHC, SM22α, h1-calponin, or myocardin. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001 vs. vehicle control. Data are plotted as starting quantity (SQ) normalized to 18S RNA.

Cleaved form of PDGF-DD inhibited expression of multiple SMC gene promoter-reporters in a dose-dependent manner.

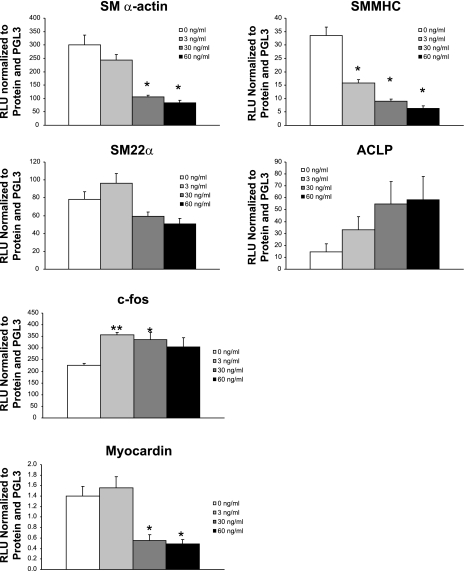

PDGF-BB decreases SMC gene mRNA levels and represses the activity of SMC gene promoter-reporter constructs (8, 42). To determine whether PDGF-DD inhibits SMC gene transcription, rat aortic SMCs were transfected with SMC gene promoter-reporter constructs and then with increasing doses of PDGF-DD. At 60 ng/ml, cleaved PDGF-DD resulted in a 72%, 81%, and 65% decrease (P < 0.05) in promoter activity of SM α-actin, SM MHC, and myocardin, respectively (Fig. 2). Furthermore, PDGF-DD at 3 ng/ml increased c-fos promoter activity 57%, and PDGF-DD at 60 ng/ml increased aortic carboxypeptidase-like protein promoter activity 401%. These results indicate that PDGF-DD-induced SMC phenotypic modulation is likely controlled, at least in part, at the level of transcription.

Fig. 2.

Cleaved PDGF-DD decreased SMC gene promoter activity in a dose-dependent manner. Growth-arrested subconfluent rat aortic SMCs were transfected with the −2555 to +2813 SM α-actin enhancer, the −4200 to +11600 SM MHC promoter-enhancer, or the −447 to +47 SM22α promoter-enhancer luciferase constructs as previously described (8). In addition, c-fos (−356/+190 bp), aortic carboxypeptidase-like protein (ACLP; −2502/+176), and myocardin promoters were also used to transfect SMCs. Mature cleaved form of human PDGF-DD (3, 30, and 60 ng/ml) was added, and specific promoter activity was measured. At 60 ng/ml, PDGF-DD decreased SM α-actin, SM MHC, and myocardin promoter activity 72%, 81%, and 65%, respectively; at 3 and 60 ng/ml PDGF-DD, c-fos and ACLP promoters were induced 57% and 401%, respectively. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001 vs. vehicle.

PDGF-DD treatment decreased SM α-actin, SM MHC, and SM22α protein levels in cultured rat aortic SMCs.

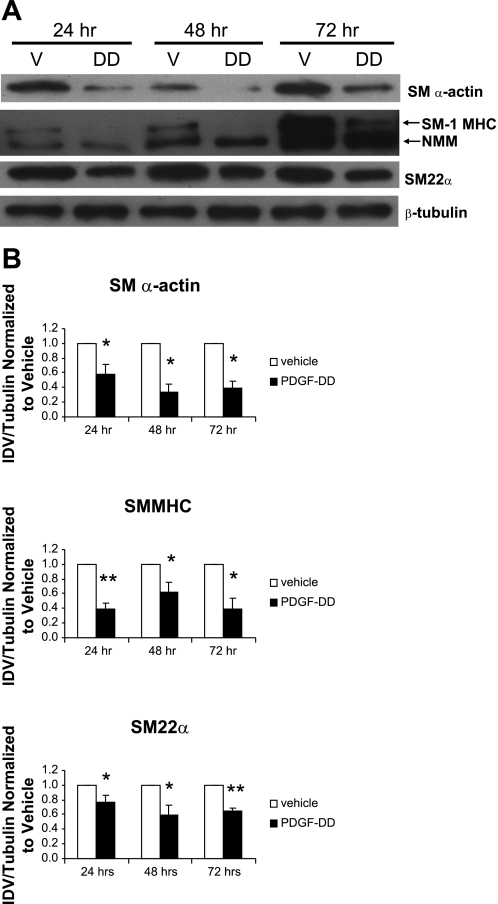

To extend our analyses of the effects of PDGF-DD on SMC gene expression, we next quantified SMC differentiation marker proteins SM α-actin, SM-1 MHC, and SM22α in rat aortic SMCs treated with the cleaved form of PDGF-DD. Importantly, cells showed diminished levels of SM α-actin, SM1 MHC, and SM22α protein after 24, 48, and 72 h of PDGF-DD treatment compared with vehicle control (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

PDGF-DD decreased SM α-actin, SM-1 MHC, and SM22α. Rat aortic SMCs were grown to 60–70% confluence and treated with insulin-free serum-free medium (IFSFM) for 16–18 h. Cells were then treated with the mature cleaved form of PDGF-DD (30 ng/ml). After 24, 48, and 72 h, cell lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis. A: treatment of rat aortic SMCs with 30 ng/ml cleaved PDGF-DD for 24, 48, and 72 h decreased levels of SM α-actin, SM-1 MHC, and SM22α protein. B: densitometry data for 3 independent experiments demonstrated a significant decrease in SM α-actin, SM1 MHC, and SM22α after 24, 48, and 72 h of treatment. V, vehicle; DD, PDGF-DD; NMM, nonmuscle myosin, IDV, integrated optical density value. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001 vs. vehicle.

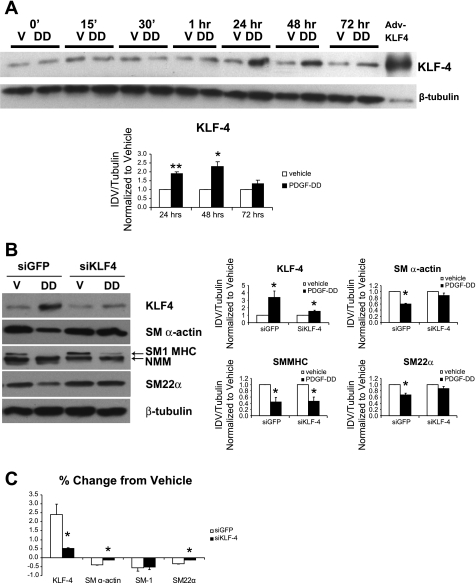

A small interfering RNA to KLF-4 partially blocked PDGF-DD-induced SMC gene repression.

We previously showed that KLF-4 can repress the expression of multiple SMC genes, including SM α-actin, SM MHC, and myocardin (26, 27). To define the kinetics of KLF-4 induction by PDGF-DD and the role of KLF-4 in PDGF-DD-induced SMC gene repression, we treated rat aortic SMCs with cleaved PDGF-DD alone or in combination with a small interfering RNA against KLF-4 (siKLF-4). Cell lysates were harvested at the indicated time points and analyzed by Western blot. After 24 and 48 h of treatment with PDGF-DD, levels of KLF-4 protein were significantly increased (Fig. 4A). The siKLF-4 significantly attenuated PDGF-DD-induced decreases in SM α-actin and SM22α protein levels, with little or no effect on changes in SM1 MHC (Fig. 4, B and C). Thus, KLF-4 appears necessary for PDGF-DD-induced repression of SM α-actin and SM22α, whereas alternative KLF-4-independent mechanisms mediate PDGF-DD-induced suppression of SM1 MHC.

Fig. 4.

Small interfering (si) RNA to KLF-4 (siKLF-4) partially blocked PDGF-DD-induced SMC gene downregulation. Rat aortic SMCs were grown to 60–70% confluence and transfected with 300 nM small interfering green fluorescent protein (siGFP) or siKLF-4 using Oligofectamine (Invitrogen). At 16 h after transfection, cells were treated with vehicle or mature cleaved form of PDGF-DD (30 ng/ml). At time indicated (A) or at 48 h (B), cell lysates were subjected to analysis by Western blot. A: KLF-4 protein levels increased 1 h after treatment with cleaved PDGF-DD (30 ng/ml) and persisted for 72 h. Significant induction of KLF-4 was observed at 24 and 48 h by densitometry. B: siKLF-4 blocked PDGF-DD-induced decreases in SM α-actin and SM22α but had no effect on SM1 MHC downregulation. C: percent change from vehicle calculations reveal that PDGF-DD-induced downregulation of SM α-actin and SM22α are dependent on KLF-4. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001 vs. vehicle.

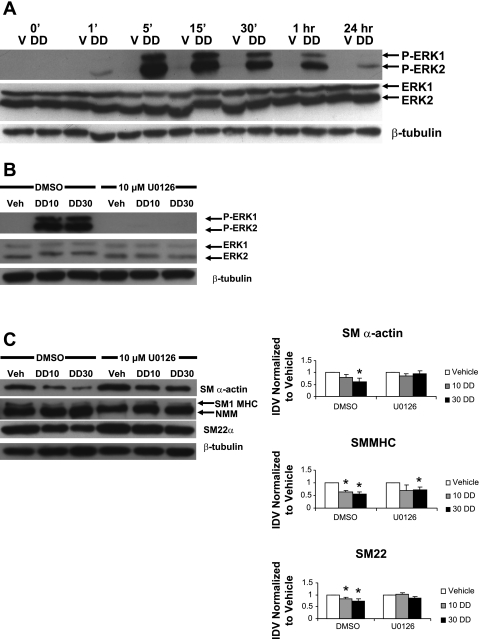

An inhibitor of ERK phosphorylation partially blocked PDGF-DD-induced SMC gene repression.

ERK is critical in mediating the effects of PDGF ββ-receptor signaling on progression through the cell cycle (29). Phosphorylation of ERK is also required for PDGF-BB-induced SMC gene repression (41). To determine whether ERK phosphorylation is involved in PDGF-DD-mediated SMC gene repression, SMCs were simultaneously treated with 0, 10, or 30 ng/ml PDGF-DD and 10 μM U-0126, an inhibitor of MEK kinase, an upstream activator of ERK1/2. Cell lysates were harvested at different time points to assess ERK1/2 phosphorylation and SMC protein levels.

Consistent with previous reports of the effects of PDGF-BB, the cleaved form of PDGF-DD induced strong and persistent phosphorylation of ERK1 and ERK2 (Fig. 5A). Moreover, the PDGF-DD-mediated decrease in SM α-actin and SM22α protein was strongly attenuated by pretreatment with U-0126 (Fig. 5C). In addition, compared with vehicle-treated cells, SM MHC downregulation by 10 ng/ml PDGF-DD was also partially blocked by treatment with U-0126 (Fig. 5C). At 30 ng/ml PDGF-DD, downregulation of SM MHC remained significant. Interestingly, KLF-4 protein levels appeared unaffected in cells treated with the inhibitor (see supplemental Fig. 2). These results demonstrate that PDGF-DD-induced repression of SMC genes is at least partially dependent on ERK1/2 phosphorylation.

Fig. 5.

Inhibition of MEK partially blocked PDGF-DD-induced downregulation of SMC genes. Rat aortic SMCs were grown to 60–70% confluence and treated with IFSFM for 16–18 h and then with the mature cleaved form of PDGF-DD (30 ng/ml) with or without the indicated MEK inhibitor. After the indicated treatment durations, cell lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis. A: treatment with the cleaved form of PDGF-DD induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation as early as 5 min after treatment. ERK1 phosphorylation of ERK1 persisted for ≥1 h, whereas ERK2 phosphorylation persisted for 24 h. P-ERK1 and P-ERK2, phosphorylated ERK1 and ERK2. B: phosphorylation of ERK1/2 induced by 10 or 30 ng/ml PDGF-DD (DD10 and DD30) was strongly blocked at 10 min by 10 μM U-0126. Veh, vehicle. C: PDGF-DD-induced downregulation of SM α-actin and SM22α were partially blocked by addition of 10 μM U-0126, while SM1 MHC appeared unaffected at 48 h after PDGF-DD treatment. *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle.

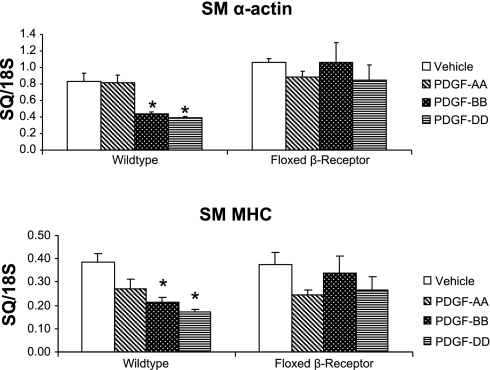

PDGF β-receptor is necessary for PDGF-DD-induced SMC gene repression.

PDGF-DD is known to be an agonist of the PDGF ββ-receptor (4). To determine whether the PDGF β-receptor is necessary for PDGF-DD-induced SMC gene repression, mouse aortic SMC cultures were derived from mice containing lox p sites flanking exon 2 of both alleles of the PDGF β-receptor gene. Treatment of these cells in culture with adenovirus-expressing Cre resulted in >90% loss of PDGF β-receptor protein (see supplemental Fig. 3). These cells were then treated with PDGF-AA, -BB, and -DD. The results are shown in Fig. 6. In cells treated with PDGF-DD, SM α-actin and SM MHC were decreased by 53% and 57%, respectively. Importantly, in mouse SMCs lacking a functional PDGF β-receptor, PDGF-DD-induced SMC gene repression was completely blocked (Fig. 6). Furthermore, PDGF-BB-induced SMC gene repression was also attenuated by the loss of a functional PDGF β-receptor. These results demonstrate that PDGF β-receptor is necessary for PDGF-BB- and -DD-induced SMC gene repression.

Fig. 6.

SMCs lacking PDGF β-receptor failed to repress SMC genes with PDGF-DD or PDGF-BB treatment. Mouse SMCs were obtained from thoracic aorta of C57/Bl6 PDGF β-receptor floxed mice by manual dissection and infected with an adenovirus expressing Cre recombinase (Cre) or an empty cassette, both under the control of the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter. Cells were then treated with vehicle, 50 ng/ml human PDGF-AA, 50 ng/ml PDGF-BB, or 30 ng/ml PDGF-DD for 24 h, and RNA was harvested and quantified by real-time PCR. In SMCs possessing a functional PDGF β-receptor, PDGF-DD substantially repressed transcription of SM α-actin and SM MHC 51% and 57%, respectively. In cells lacking PDGF β-receptor, PDGF-DD- and -BB-induced SMC gene repression was abrogated. *P < 0.05.

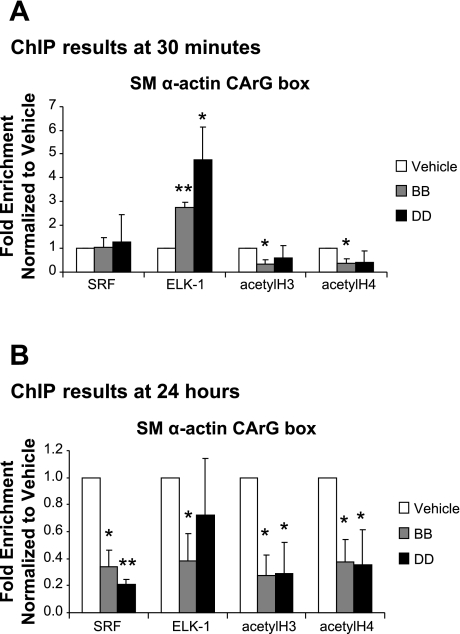

PDGF-DD decreased histone marks associated with SMC gene activation and enhanced phosphorylated Elk enrichment at the SM α-actin CArG box.

Previous studies from our laboratory (28, 42) and from others (41) demonstrated that epigenetic modifications contribute to PDGF-BB-induced suppression of SMC marker genes. To determine whether PDGF-DD treatment alone is sufficient to induce epigenetic modifications, we performed quantitative ChIP experiments to measure enrichment of acetyl-H3, acetyl-H4, SRF, and Elk-1 at the SM α-actin CArG box in rat aortic SMCs treated with PDGF-BB or PDGF-DD. After treatment for 0.5 h with either ligand at 30 ng/ml, Elk-1 was significantly enriched and acetyl-H3 and acetyl-H4 in the CArG box-containing region of the SM α-actin promoter were reduced (Fig. 7A). SRF enrichment showed no change at this time point. In contrast, after 24 h of treatment, Elk-1 enrichment returned to vehicle-treated levels in PDGF-DD-treated cells, but cells showed markedly decreased enrichment of SRF, as well as acetyl-H3 and acetyl-H4 (Fig. 7B). Taken together, these results are consistent with a model wherein PDGF-DD-induced repression of SMC marker genes is mediated at early time points by rapid and sustained reduction in histone H3/H4 acetylation and by ERK-dependent phosphorylation of Elk-1, as well as by inhibition of SRF binding to chromatin via epigenetic controls at later time points.

Fig. 7.

PDGF-DD induced early Elk-1 enrichment and late loss of SRF binding and histone acetylation at the SM α-actin promoter within intact chromatin. Subconfluent growth-arrested rat aortic SMCs were treated with PDGF-BB or -DD (30 ng/ml). After 30 min or 24 h of treatment, chromatin was isolated and subjected to quantitative chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis. A: after 30 min of PDGF-BB or -DD treatment, Elk-1 showed 2.5- and 4.5-fold enrichment, respectively, at the SM α-actin promoter. Additionally, there was a trend toward loss of acetylation of histone 3 and 4, with no change in serum response factor (SRF) enrichment. B: PDGF-BB and -DD induced a loss of SRF from the SM α-actin promoter after 24 h of treatment coincident with a loss of acetylation of histone 3 and 4. In contrast, there was no change in Elk-1 enrichment for PDGF-BB and -DD-treated cells at 24 h after treatment. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001.

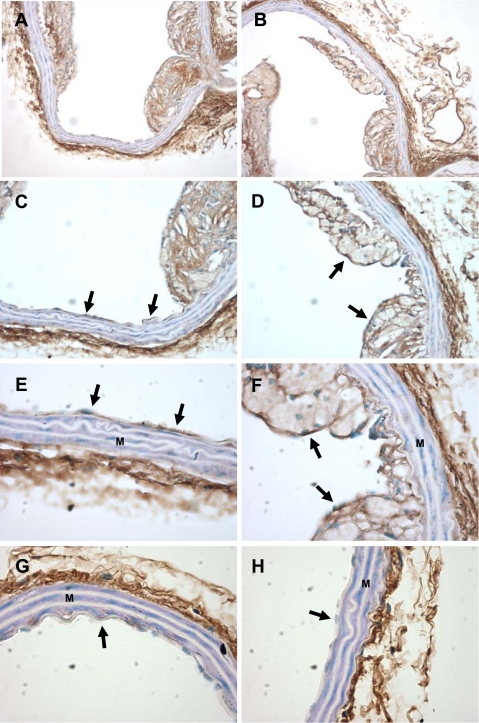

PDGF-DD expression was elevated in intimal lesions within the aortic arch region of ApoE−/− atherosclerotic mice.

PDGF-DD profoundly inhibited the expression of multiple SMC genes and induced SMC phenotypic modulation. Given the preponderance of phenotypically modulated SMCs in atherosclerotic lesions, we next wished to determine the expression of PDGF-DD in lesions in an experimental model of atherosclerosis in mice. Aortic arch and descending thoracic aorta sections from ApoE−/− mice fed a Western diet for 20 wk and age-matched C57/Bl6 wild-type mice were stained with antibodies to PDGF-DD. Wild-type mice showed strong staining in the adventitia and virtually no staining in the media or intima in aortic arch and descending thoracic aorta sections (Fig. 8, G and H). Interestingly, staining of the neointima in the aortic arch of ApoE−/− mice was intense within ECs adjacent to intimal lesions (Fig. 8, C and E), as well as cells within the intimal lesions (Fig. 8, D and F). In addition, compared with those from wild-type mice, sections from ApoE−/− mouse showed a similar pattern of staining with respect to the adventitial and medial layers in the aortic arch and descending thoracic aorta sections (Fig. 8). Staining was decreased in mouse aortic sections incubated with anti-PDGF-DD and recombinant PDGF-DD compared with anti-PDGF-DD alone, demonstrating the specificity of anti-PDGF-DD (see supplemental Fig. 4).

Fig. 8.

Region-specific expression of PDGF-DD in atherosclerotic lesions from apolipoprotein E-deficient (ApoE−/−) mice. Aortic arch sections from ApoE−/− mice fed a Western diet for 20 wk and age-matched wild-type C57/B6 mice were stained with antibodies to PDGF-DD. A, C, and E and B, D, and F are images of increasing objective power (×10, ×20, and ×40) in the same lesion area from the aortic arch. Endothelium (arrows), developing lesions, and adventitia stain positive for PDGF-DD, the media (M) does not. In G and H, endothelium of the aortic arch does not stain positive for PDGF-DD in C57/B6 wild-type controls (×40).

PDGF-DD is upregulated in ECs exposed to atherosclerosis-prone flow patterns.

Phenotypically modulated SMCs are a major cellular component of atherosclerotic lesions (35). These lesions predictably develop at branch points in the arterial vascular tree, where blood flow is nonlaminar or transitional and time-averaged shear stress is low. Given the potent ability of PDGF-DD to induce SMC phenotypic modulation as well as its expression in ApoE−/− mice, we used a novel disturbed-flow EC-SMC coculture model (15, 30) to test whether PDGF-DD expression is induced in ECs exposed to shear stress patterns characteristic of human atheroprone regions (14).

Human SMCs and ECs were cocultured and exposed to hemodynamic forces modeled after blood flow found in the human common carotid artery, a blood vessel relatively resistant to the development of atherosclerotic lesions (“atheroprotective”), or the internal carotid sinus portion of the human vascular tree, a region prone to atherosclerotic lesion development (“atheroprone”) (14).

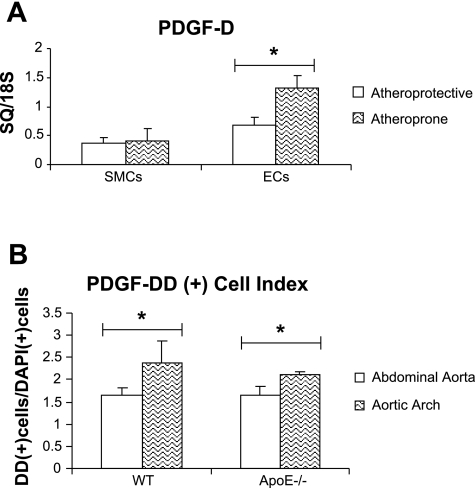

Human ECs exposed to atheroprotective flow patterns showed unchanged levels of PDGF-DD mRNA by real-time PCR analysis compared with cultured ECs exposed to static, or no-flow, conditions (data not shown). Importantly, PDGF-DD mRNA expression was significantly increased by 91% in human ECs exposed to atheroprone flow patterns compared with human ECs exposed to atheroprotective flow patterns (Fig. 9A). In contrast, human SMCs showed no significant change with exposure to altered flow patterns (Fig. 9A).

Fig. 9.

PDGF-DD is upregulated in human endothelial cells (ECs) exposed to carotid sinus flow patterns and in the murine aortic root in vivo. A: ECs and SMCs were plated on opposite sides of gelatin-coated porous polycarbonate membrane and grown together in reduced-serum medium. After 24 h of incubation, one of two separate and distinct waveforms, atheroprone or atheroprotective, was applied to the coculture system for an additional 24 h. Real-time PCR showed significantly upregulated expression of PDGF-D in ECs exposed to atheroprone flow patterns compared with ECs exposed to atheroprotective patterns. SMCs showed no change in PDGF-D expression with application of altered flow patterns. B: aortic arch and abdominal aorta sections from wild-type (WT) and age-matched ApoE−/− mice were stained with antibodies to PDGF-DD and with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) nuclear stain. Cells were blindly counted for either signal and are presented as a ratio. A greater proportion of cells expressed PDGF-DD in the aortic arch than in the abdominal aorta in wild-type and ApoE−/− mice. *P < 0.05.

PDGF-DD is upregulated in the proximal aorta in vivo.

ECs exposed to atheroprone flow upregulated PDGF-DD expression compared with cells exposed to atheroprotective flow. This suggests that hemodynamic forces play a role in regulating PDGF-DD expression in vivo. To determine whether PDGF-DD was increased in regions of atheroprone flow in vivo, we quantified PDGF-DD by immunofluorescence in the aortic arch (atheroprone region) and abdominal aorta (atheroprotective region) of wild-type and aged-matched ApoE−/− mice. Briefly, cross sections from corresponding portions of the aorta were stained with antibodies to PDGF-DD and DAPI and then blindly counted, and the ratio of PDGF-DD-positive to DAPI-positive cells was calculated (Fig. 9B). Interestingly, cells staining positive for PDGF-DD were present in greater abundance in the aortic root than in the abdominal aorta in wild-type mice (Fig. 9B). Importantly, this phenomenon was also observed in age-matched ApoE−/− mice (Fig. 9B). These results suggest that atheroprone hemodynamic forces may also activate PDGF-DD expression in vivo.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to explore the role of PDGF-DD, a recently identified PDGF ββ-receptor ligand, in SMC phenotypic modulation. Several novel results are presented. 1) PDGF-DD has the capacity to potently downregulate SMC genes. Moreover, we found that PDGF-DD decreased the activity of several SMC gene promoter-reporter constructs, indicating that changes are mediated, at least in part, at the transcriptional level. 2) PDGF-DD induced ERK phosphorylation and increased KLF-4 expression, two downstream mediators shown here to be required for PDGF-DD-induced SMC gene repression. 3) The PDGF β-receptor was necessary for PDGF-DD-induced SMC gene repression. 4) ChIP studies demonstrate that PDGF-DD decreased binding of SRF to CArG cis-elements within the endogenous SM α-actin promoter in intact chromatin. In addition, there was early recruitment of Elk-1 to the promoter, as well as a later decrease in histone H3 and H4 acetylation. 5) PDGF-DD was increased in the neointima of atherosclerotic lesions from the aortic arch of ApoE−/− atherosclerotic mice. 6) In a coculture model of ECs and SMCs, human ECs exposed to atheroprone hemodynamic shear stress significantly upregulated the expression of PDGF-DD, while cells expressing PDGF-DD were more abundant in vivo in regions of atheroprone flow. These latter observations are consistent with a model in which ECs, located within atherosclerosis-prone regions of the vasculature, secrete and release PDGF-DD in response to oscillatory and low-shear-stress blood flow patterns. This secretion, in turn, may induce SMCs to alter their phenotype, a cellular change observed in atherosclerotic lesions. Importantly, these results establish a potential link between atherosclerosis-prone blood flow patterns, PDGF-DD secretion by ECs, and SMC phenotypic modulation.

The SMC phenotypic modulatory activity of PDGF-BB is well described (5, 8, 19, 41, 42). However, the role of PDGF-DD in this process and the receptor responsible are virtually unexplored. The specific receptor binding profile of PDGF-DD, as well as a unique loss-of-function approach, allowed us to test the dependence of SMC gene repression on PDGF β-receptor signaling. Indeed, the above-described experiments establish for the first time that the PDGF β-receptor is necessary for SMC gene repression induced by PDGF-DD. Moreover, observations that PDGF-BB induced repression of SMC marker genes was also abrogated in PDGF β-receptor-knockout SMC (Fig. 6) are the first to conclusively show that these effects are dependent on the β-receptor, in that previous studies relied solely on use of pharmacological inhibitors that may affect other receptor pathways.

The binding receptor profile of PDGF-DD is controversial. Conflicting reports suggest that PDGF-DD is a specific β-receptor agonist or has activity at the α- and/or α/β-receptor heterodimer (4, 18). Indeed, the ability of PDGF-DD to bind the PDGF α- or α/β-receptor has not been established (2). Thus we cannot rule out the possibility that PDGF-DD acts, at least in part, through the PDGF α-receptor.

Results demonstrating that PDGF-DD and -BB enhanced early Elk-1 enrichment, late loss of SRF enrichment, and histone H3 and H4 acetylation suggest that these chromatin modifications are important for PDGF-induced SMC gene repression. The mechanisms for PDGF-BB-induced SMC gene repression have been explored in depth (26, 28, 40–42). This activity has been shown to be dependent on multiple repressor pathways (for review see Ref. 21), including ERK1/2 phosphorylation (41), Sp1 (40), histone deacetylase-2 (42), and p38 (16). Furthermore, PDGF-BB-induced SMC gene repression correlated with decreased SRF (26, 28, 40, 42) and decreased myocardin enrichment (41), loss of histone H4 acetylation (28, 42), and Elk-1 enrichment (41, 42) at various SMC gene promoters among other mechanisms (21). A similar loss of SRF, decreased histone H3 and H4 acetylation, and Elk-1 enrichment between PDGF-BB and -DD indicate that these epigenetic changes are downstream of PDGF ββ-receptor binding and do not require PDGF αα-receptor agonism.

KLF-4 and phosphorylation of ERK are shown here to be required for PDGF-DD-induced SM α-actin and SM22α repression. ERK1/2 phosphorylation is necessary for PDGF-BB-induced SMC gene repression (41), and KLF-4 is induced by PDGF-BB and capable of repressing myocardin-induced SMC gene activation (26). Here, we demonstrate that KLF-4 and ERK are additive in their ability to mediate PDGF-DD-induced SM α-actin and SM22α gene repression. siKLF-4 showed no effect on ERK1/2 phosphorylation or protein levels. Conversely, MEK1/2 inhibition with two separate compounds showed no effect on KLF-4 expression (see supplemental Fig. 2). Thus these data provide novel evidence that KLF-4 and ERK1/2 are independent downstream mediators of PDGF ββ-receptor-induced SMC gene repression. However, further studies are needed to determine the signaling pathways responsible for KLF-4 induction and SM MHC repression.

Our findings that PDGF-DD is upregulated in ECs exposed to atheroprone hemodynamic flow patterns suggest a novel pathophysiological role for PDGF-DD. Although evidence supports a role for PDGF-BB in the formation of atherosclerotic lesions in regions of disturbed flow (36), surprisingly few studies have tested the role of PDGF-DD, despite the clear importance of PDGF β-receptor signaling (23, 33). In addition, it is interesting to speculate that PDGF-DD may contribute to the formation of intimal masses, which represent accumulations of SMCs in the intima that preferentially develop in regions of disturbed flow in humans at an early age (39). An increased number of PDGF-DD-positive cells in regions prone to the development of atherosclerosis in wild-type mice, which do not develop atherosclerotic lesions spontaneously, is consistent with this hypothesis. Whereas much additional work is needed to test these possibilities, the results of the present studies indicate that further study of the potential role of PDGF-DD in formation of intimal masses in humans is warranted.

The evolution of a distinct PDGF family member became an outstanding question upon the discovery of PDGF-DD. By agonizing a distinct set of receptors in vivo, it is believed that PDGF-DD mediates physiological effects that are different from those of other PDGF family members. Importantly, the receptor binding profile of PDGF-DD remains controversial; thus a discussion of the role of PDGF-DD in vivo is limited. However, a discussion of α- vs. β-receptor roles is important. Although somewhat controversial, results from a number of in vitro studies have provided evidence that PDGF α-receptor signaling selectively mediates DNA and protein synthesis (20, 37), but not migration (9), whereas PDGF β-receptor signaling induces DNA synthesis (20) and migration (9). Because of the receptor binding properties of PDGF-DD, it is interesting to speculate that perhaps PDGF-DD contributes to disease states where there is both migration and proliferation of β-receptor-expressing cells. Examples would include tumor growth and invasion, where mural cells must migrate and invest newly developed tumor capillaries during arterialization, as well as atherosclerosis, which is characterized by intimal migration and proliferation of SMC. Indeed, evidence has emerged implicating PDGF-DD in tumorigenesis and atherosclerosis (24, 34). In contrast, PDGF-AA or selective PDGF α-receptor activation may primarily mediate SMC growth without migration, as occurs during development of medial hypertrophy in hypertension (for review see Ref. 31). However, there are a number of critical unresolved questions. 1) Does PDGF α- vs. β-receptor signaling mediate fundamentally different SMC responses in vivo as opposed to responses in cultured cells, which have been the focus of virtually all studies comparing these two signaling pathways? 2) What is the cross talk between PDGF α- and β-receptor signaling pathways within SMC in vivo that might alter responses to PDGF-BB vs. PDGF-DD? 3) What is the exact receptor binding profile of PDGF-DD? Indeed, a key question is as follows: Do SMC in vivo, which express both PDGF α- and β-receptors, show differences in gene expression patterns when stimulated with PDGF-BB vs. PDGF-DD? Resolving these questions will require development of complex mouse lines that exhibit conditional and SMC-selective knockout of these receptors in combination with models of vascular injury, atherosclerosis, and hypertension.

In summary, the results of the present studies reveal a novel role for PDGF-DD in SMC physiology and as a potential chemical mediator of hemodynamic shear stress. We demonstrate the conservation of molecular mechanisms between PDGF-BB and -DD, implicating early Elk-1 enrichment and late loss of SRF and histone acetylation as effectors of SMC gene repression. Finally, we demonstrate that ERK signaling, KLF-4, and the PDGF β-receptor are necessary for PDGF-DD-induced SMC gene repression. Importantly, these data establish a link between low/oscillatory shear stress blood flow, such as that which occurs in regions of atherosclerotic lesion formation, EC-mediated PDGF-DD expression, and SMC phenotypic modulation. Future experiments will be aimed at delineating the specific role of PDGF-DD in the progression of atherosclerosis and other diseases associated with disturbed blood flow, as well as the role of PDGF α-receptor signaling in PDGF-DD-induced SMC gene repression.

GRANTS

This research was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants P01 HL-19242, R01 HL-38854, and R37 HL-57353 (to G. K. Owens), American Heart Association Predoctoral Fellowship 0515324U (to J. A. Thomas), the University of Virginia Fund for Excellence in Science and Technology (to B. R. Blackman), and University of Virginia Basic Cardiovascular Training Grant 5T32 HL-0084 (to N. E. Hastings).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Diane Raines, Rupanda Tripathi, and Mary McCanna for expert technical assistance, John Sanders for immunofluorescence expertise, and ZymoGenetics for the generous contribution of full-length and cleaved PDGF-DD.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anonymous. National Cholesterol Education Program. Third Report of the Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Bethesda, MD: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 2001. (NIH Publ. No. 01-3670.)

- 2.Andrae J, Gallini R, Betsholtz C. Role of platelet-derived growth factors in physiology and medicine. Genes Dev 22: 1276–1312, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arbustini E, Dal Bello B, Morbini P, Burke AP, Bocciarelli M, Specchia G, Virmani R. Plaque erosion is a major substrate for coronary thrombosis in acute myocardial infarction. Heart 82: 269–272, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergsten E, Uutela M, Li X, Pietras K, Ostman A, Heldin CH, Alitalo K, Eriksson U. PDGF-D is a specific, protease-activated ligand for the PDGF-β receptor. Nat Cell Biol 3: 512–516, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blank RS, Owens GK. Platelet-derived growth factor regulates actin isoform expression and growth state in cultured rat aortic smooth muscle cells. J Cell Physiol 142: 635–642, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caro CG, Fitz-Gerald JM, Schroter RC. Atheroma and arterial wall shear. Observation, correlation and proposal of a shear-dependent mass transfer mechanism for atherogenesis. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 177: 109–159, 1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cunningham KS, Gotlieb AI. The role of shear stress in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Lab Invest 85: 9–23, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dandre F, Owens GK. Platelet-derived growth factor-BB and Ets-1 transcription factor negatively regulate transcription of multiple smooth muscle cell differentiation marker genes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 286: H2042–H2051, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davies MG, Owens EL, Mason DP, Lea H, Tran PK, Vergel S, Hawkins SA, Hart CE, Clowes AW. Effect of platelet-derived growth factor receptor-α and -β blockade on flow-induced neointimal formation in endothelialized baboon vascular grafts. Circ Res 86: 779–786, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davies MJ, Richardson PD, Woolf N, Katz DR, Mann J. Risk of thrombosis in human atherosclerotic plaques: role of extracellular lipid, macrophage, and smooth muscle cell content. Br Heart J 69: 377–381, 1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fredriksson L, Li H, Eriksson U. The PDGF family: four gene products form five dimeric isoforms. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 15: 197–204, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galis ZS, Khatri JJ. Matrix metalloproteinases in vascular remodeling and atherogenesis: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Circ Res 90: 251–262, 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galis ZS, Sukhova GK, Lark MW, Libby P. Increased expression of matrix metalloproteinases and matrix degrading activity in vulnerable regions of human atherosclerotic plaques. J Clin Invest 94: 2493–2503, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gelfand BD, Epstein FH, Blackman BR. Spatial and spectral heterogeneity of time-varying shear stress profiles in the carotid bifurcation by phase-contrast MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging 24: 1386–1392, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hastings NE, Simmers MB, McDonald OG, Wamhoff BR, Blackman BR. Atherosclerosis-prone hemodynamics differentially regulates endothelial and smooth muscle cell phenotypes and promotes pro-inflammatory priming. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 293: C1824–C1833, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayashi K, Takahashi M, Kimura K, Nishida W, Saga H, Sobue K. Changes in the balance of phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B (Akt) and the mitogen-activated protein kinases (ERK/p38MAPK) determine a phenotype of visceral and vascular smooth muscle cells. J Cell Biol 145: 727–740, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hendrix JA, Wamhoff BR, McDonald OG, Sinha S, Yoshida T, Owens GK. 5′ CArG degeneracy in smooth muscle α-actin is required for injury-induced gene suppression in vivo. J Clin Invest 115: 418–427, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoch RV, Soriano P. Roles of PDGF in animal development. Development 130: 4769–4784, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holycross BJ, Blank RS, Thompson MM, Peach MJ, Owens GK. Platelet-derived growth factor-BB-induced suppression of smooth muscle cell differentiation. Circ Res 71: 1525–1532, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inui H, Kitami Y, Tani M, Kondo T, Inagami T. Differences in signal transduction between platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) α- and β-receptors in vascular smooth muscle cells. PDGF-BB is a potent mitogen, but PDGF-AA promotes only protein synthesis without activation of DNA synthesis. J Biol Chem 269: 30546–30552, 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawai-Kowase K, Owens GK. Multiple repressor pathways contribute to phenotypic switching of vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 292: C59–C69, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kolodgie FD, Virmani R, Burke AP, Farb A, Weber DK, Kutys R, Finn AV, Gold HK. Pathologic assessment of the vulnerable human coronary plaque. Heart 90: 1385–1391, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kozaki K, Kaminski WE, Tang J, Hollenbach S, Lindahl P, Sullivan C, Yu JC, Abe K, Martin PJ, Ross R, Betsholtz C, Giese NA, Raines EW. Blockade of platelet-derived growth factor or its receptors transiently delays but does not prevent fibrous cap formation in ApoE null mice. Am J Pathol 161: 1395–1407, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larochelle WJ, Jeffers M, Corvalan JR, Jia XC, Feng X, Vanegas S, Vickroy JD, Yang XD, Chen F, Gazit G, Mayotte J, Macaluso J, Rittman B, Wu F, Dhanabal M, Herrmann J, Lichenstein HS. Platelet-derived growth factor D: tumorigenicity in mice and dysregulated expression in human cancer. Cancer Res 62: 2468–2473, 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Larochelle WJ, Jeffers M, McDonald WF, Chillakuru RA, Giese NA, Lokker NA, Sullivan C, Boldog FL, Yang M, Vernet C, Burgess CE, Fernandes E, Deegler LL, Rittman B, Shimkets J, Shimkets RA, Rothberg JM, Lichenstein HS. PDGF-D, a new protease-activated growth factor. Nat Cell Biol 3: 517–521, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu Y, Sinha S, McDonald OG, Shang Y, Hoofnagle MH, Owens GK. Kruppel-like factor 4 abrogates myocardin-induced activation of smooth muscle gene expression. J Biol Chem 280: 9719–9727, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu Y, Sinha S, Owens G. A transforming growth factor-β control element required for SM α-actin expression in vivo also partially mediates GKLF-dependent transcriptional repression. J Biol Chem 278: 48004–48011, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McDonald OG, Wamhoff BR, Hoofnagle MH, Owens GK. Control of SRF binding to CArG box chromatin regulates smooth muscle gene expression in vivo. J Clin Invest 116: 36–48, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Millette E, Rauch BH, Defawe O, Kenagy RD, Daum G, Clowes AW. Platelet-derived growth factor-BB-induced human smooth muscle cell proliferation depends on basic FGF release and FGFR-1 activation. Circ Res 96: 172–179, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Orr AW, Stockton R, Simmers MB, Sanders JM, Sarembock IJ, Blackman BR, Schwartz MA. Matrix-specific p21-activated kinase activation regulates vascular permeability in atherogenesis. J Cell Biol 176: 719–727, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Owens GK Control of hypertrophic versus hyperplastic growth of vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 257: H1755–H1765, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Owens GK, Kumar MS, Wamhoff BR. Molecular regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation in development and disease. Physiol Rev 84: 767–801, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palumbo R, Gaetano C, Antonini A, Pompilio G, Bracco E, Ronnstrand L, Heldin CH, Capogrossi MC. Different effects of high and low shear stress on platelet-derived growth factor isoform release by endothelial cells: consequences for smooth muscle cell migration. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 22: 405–411, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ponten A, Folestad EB, Pietras K, Eriksson U. Platelet-derived growth factor D induces cardiac fibrosis and proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells in heart-specific transgenic mice. Circ Res 97: 1036–1045, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ross R The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis: a perspective for the 1990s. Nature 362: 801–809, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rutherford C, Martin W, Carrier M, Anggard EE, Ferns GA. Endogenously elicited antibodies to platelet-derived growth factor-BB and platelet cytosolic protein inhibit aortic lesion development in the cholesterol-fed rabbit. Int J Exp Pathol 78: 21–32, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seifert RA, Hart CE, Phillips PE, Forstrom JW, Ross R, Murray MJ, Bowen-Pope DF. Two different subunits associate to create isoform-specific platelet-derived growth factor receptors. J Biol Chem 264: 8771–8778, 1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ustach CV, Kim HR. Platelet-derived growth factor D is activated by urokinase plasminogen activator in prostate carcinoma cells. Mol Cell Biol 25: 6279–6288, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Virmani R, Kolodgie FD, Burke AP, Farb A, Schwartz SM. Lessons from sudden coronary death: a comprehensive morphological classification scheme for atherosclerotic lesions. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 20: 1262–1275, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wamhoff BR, Hoofnagle MH, Burns A, Sinha S, McDonald OG, Owens GK. A G/C element mediates repression of the SM22α promoter within phenotypically modulated smooth muscle cells in experimental atherosclerosis. Circ Res 95: 981–988, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Z, Wang DZ, Hockemeyer D, McAnally J, Nordheim A, Olson EN. Myocardin and ternary complex factors compete for SRF to control smooth muscle gene expression. Nature 428: 185–189, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoshida T, Gan Q, Shang Y, Owens GK. Platelet-derived growth factor-BB represses smooth muscle cell marker genes via changes in binding of MKL factors and histone deacetylases to their promoters. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 292: C886–C895, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zarins CK, Giddens DP, Bharadvaj BK, Sottiurai VS, Mabon RF, Glagov S. Carotid bifurcation atherosclerosis. Quantitative correlation of plaque localization with flow velocity profiles and wall shear stress. Circ Res 53: 502–514, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.