Abstract

Galectin-3 (Gal-3) is secreted by activated macrophages. In hypertension, Gal-3 is a marker for hypertrophic hearts prone to develop heart failure. Gal-3 infused in pericardial sac leads to cardiac inflammation, remodeling, and dysfunction. N-acetyl-seryl-aspartyl-lysyl-proline (Ac-SDKP), a naturally occurring tetrapeptide, prevents and reverses inflammation and collagen deposition in the heart in hypertension and heart failure postmyocardial infarction. In the present study, we hypothesize that Ac-SDKP prevents Gal-3-induced cardiac inflammation, remodeling, and dysfunction, and these effects are mediated by the transforming growth factor (TGF)-β/Smad3 signaling pathway. Adult male rats were divided into four groups and received the following intrapericardial infusion for 4 wk: 1) vehicle (saline, n = 8); 2) Ac-SDKP (800 μg·kg−1·day−1, n = 8); 3) Gal-3 (12 μg/day, n = 7); and 4) Ac-SDKP + Gal-3 (n = 7). Left ventricular ejection fraction, cardiac output, and transmitral velocity were measured by echocardiography; inflammatory cell infiltration, cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, and collagen deposition in the heart by histological and immunohistochemical staining; and TGF-β expression and Smad3 phosphorylation by Western blot. We found that, in the left ventricle, Gal-3 1) enhanced macrophage and mast cell infiltration, increased cardiac interstitial and perivascular fibrosis, and causes cardiac hypertrophy; 2) increased TGF-β expression and Smad3 phosphorylation; and 3) decreased negative change in pressure over time response to isoproterenol challenge, ratio of early left ventricular filling phase to atrial contraction phase, and left ventricular ejection fraction. Ac-SDKP partially or completely prevented these effects. We conclude that Ac-SDKP prevents Gal-3-induced cardiac inflammation, fibrosis, hypertrophy, and dysfunction, possibly via inhibition of the TGF-β/Smad3 signaling pathway.

Keywords: N-acetyl-seryl-aspartyl-lysyl-proline, cardiac dysfunction, fibrosis, inflammation

galectin-3 (gal-3) (also known as MAC-2 antigen) is a member of a large family of β-galactoside-binding adhesion/growth-regulatory endogenous lectins. This lectin is a multifunctional factor and binds to distinct glycan and protein ligands (13). Gal-3 is expressed and released by the epithelium and by inflammatory cells, including macrophages, mast cells, and neutrophils, which are involved in different physiological and pathological conditions. Evidence links macrophage activation and infiltration to cardiac remodeling and to pathogenesis of heart failure (HF) (12, 38). In a model of renin-dependent hypertension with HF (transgenic Ren-2 rats), cardiac Gal-3 is one of the most strongly overexpressed genes. In this model of hypertension, at early stages of cardiac hypertrophy (before HF development), myocardial Gal-3 expression was increased to higher levels in those rats that later progressed to HF, compared with those that remained compensated (34, 35). Recently, clinical studies have shown that serum Gal-3 levels were elevated in patients with acute HF, and they were prognostic of adverse outcome (19, 39). Increased Gal-3 secretion stimulates release of various mediators, such as transforming growth factor (TGF)-β and interleukins-1 or -2, and promote cardiac fibroblast proliferation, collagen deposition, and ventricular dysfunction (1, 35, 40).

N-acetyl-seryl-aspartyl-lysyl-proline (Ac-SDKP) is a naturally occurring anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic peptide. Ac-SDKP is hydrolyzed almost exclusively by angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), and its plasma concentration is increased substantially by ACE inhibitors (3). In fact, Ac-SDKP mediates the anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic effects of ACE inhibitors (22, 24). Rats overexpressing cardiac ACE have decreased Ac-SDKP concentration and increased fibrosis in the heart (26). Also, inhibition of Ac-SDKP release from thymosin-β4 promotes cardiac and renal perivascular fibrosis (PVF) and nephrosclerosis (7). Our laboratory and others have shown previously that in vitro Ac-SDKP inhibited cardiac fibroblast proliferation and collagen synthesis (25, 29). Treatment with Ac-SDKP reduces inflammation and collagen deposition in the heart and kidney in various hypertensive models and in HF post-myocardial infarction (MI) (22, 23, 30, 42).

We have evidence that, in the left ventricle (LV), Ac-SDKP inhibits Gal-3 expression caused by ANG II infusion. Also, Ac-SDKP, in vitro, inhibits macrophage activation and migration induced by Gal-3 (33), suggesting that this tetrapeptide may inhibit not only Gal-3 expression, but also its effects. In the present study, we investigated the hypothesis that that Ac-SDKP prevents Gal-3-induced cardiac inflammation, remodeling, and dysfunction, and these effects are mediated by the TGF-β/Smad3 signaling pathway. We used intrapericardial administration of Gal-3 and/or Ac-SDKP in rats. This method allows us to target the heart and obtain site-selective drug efficiency with low-level systemic effects.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA), weighing 275–300 g, were housed in an air-conditioned room with a 12:12-h light-dark cycle, where they received standard laboratory rat chow (0.4% sodium) and drank tap water. They were given 7 days to adjust to their new environment. Before all surgical procedures, they were given analgesia with butorphanol (2 mg/kg sc) and anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg ip). This study was approved by the Henry Ford Hospital Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Systolic blood pressure (SBP) was measured by tail cuff before surgery and by the end of the experiment.

Surgical procedure for installing an intrapericardial catheter.

MRE 010 Micro-Renathane tubing (inner diameter 0.005 mm, outer diameter 0.01 mm) is made into a loop (10 mm in diameter), which is attached to a silicone disk with silicone adhesive. One end of the loop is closed, and the other is opened and connected to a Tygon tubing (inner diameter 0.015 mm, outer diameter 0.03 mm) and perforated through the disk. The Tygon tubing is, in turn, connected to a PE-60 tubing, which is fitted to the flow moderator of an osmotic minipump (Alzet 2004, Durect, Cupertino, CA). The loop was punctured with ∼10 holes for perfusing drug solution. We modified the technique of inserting a catheter into the pericardial sac reported previously (14) by not cutting the midline sternum, thus lessening bleeding. Rats were intubated and ventilated with room air using a positive-pressure respirator (model 680, Harvard, South Natick, MA). A left thoracotomy was performed via the third intercostal space, and the lungs retracted to expose the thymus lobes and the heart. The thymus lobes were carefully separated, and the upper part of the pericardial sac was punctured (1- to 2-mm opening). The loop catheter was inserted into the pericardial sac, which was then closed by sealing it to the thymus with tissue adhesive glue (vetbond, 3M, St. Paul, MN). The minipump was implanted subcutaneously between the shoulder blades. The open end of the catheter was guided to the place where the osmotic minipump was implanted and connected to it. The lungs were inflated by increasing positive end-expiratory pressure, and then the thoracotomy site was closed.

Experimental protocols.

In a preliminary study, we infused Gal-3 intrapericardially for 2 wk (n = 5 each). Although we found that Gal-3 increased interstitial collagen fraction (ICF) (P < 0.05) and PVF (P < 0.05), the heart and lung weights were not increased. In addition, echocardiographic study showed that Gal-3 tended to reduce ratio of early left ventricular filling phase to atrial contraction phase (E/A ratio), but did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.07), and LV ejection fraction (LVEF) was not changed. Hence, in the present study, we extended the infusion of Gal-3 to 4 wk. The following intrapericardiac treatment groups were studied: 1) vehicle, received saline; 2) Ac-SDKP, 800 μg·kg−1·day−1; 3) Gal-3, 12 μg/day [the dose was calculated on the basis of reported bioactivity, adjusting for the local advantage of pericardial delivery (14)]; and 4) Gal-3 plus Ac-SDKP. The perfusion period was 4 wk. Gal-3 was prepared by recombinant production and purified using affinity chromatography and checked for purity by one- and two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and mass spectrometry (32). To exclude the possibility that Ac-SDKP binds Gal-3 and directly interferes with its effects, we performed binding assays with biotinylated Gal-3, both in solid phase (with asialofetuin as matrix) (2) and in a cell system with the natural glycan profile (5). Biotinylated Gal-3 was quantitated spectrophotometrically or by flow cytometry, in the presence of lactose (a positive control) or Ac-SDKP. Lactose inhibited Gal-3 binding nearly completely at 1 mM, while Ac-SDKP caused no inhibition up to 16 mM in the solid-phase assay and up to 8 mM in the cell system. These data indicate that Ac-SDKP does not interfere with Gal-3 binding to glycans.

Echocardiography.

Echocardiography and Doppler sonography (Acuson, Sequoia C 256 with 15-MHz transducer) were performed while simultaneously recording ECG. M-mode echocardiography was performed in the parasternal long-axis view for the measurement of LV dimensions, and then in the anterior short-axis view to evaluate LVEF. Transmitral Doppler inflow waves were used to measure peak early diastolic filling velocity (E wave), peak filling velocity at atrial contraction (A wave), and their ratio (E/A), assessing diastolic function as described previously (27). Aortic systolic velocity-time integral (VTI) and aortic root dimension (AoD) were determined, and stroke volume calculated according to the formula: stroke volume = (VTI)[(AoD/2)2]. Cardiac output (CO) = stroke volume × heart rate (HR). All Doppler spectra were recorded for five to seven cardiac cycles at a sweep speed of 200 mm/s.

Cardiac hemodynamics.

Following echocardiography, rats were intubated. Cardiac contractility was assessed following previously described methods for LV catheterizations (44) and stimulation of cardiac reserve (31). Briefly, a 2-French Mikro-Tip catheter (Millar, Houston, TX) was introduced in the LV through the right carotid artery. A jugular vein was also cannulated, and isoproterenol (0.02 μg·kg−1·min−1) was infused for 4 min. LV pressure and positive and negative change in pressure over time (±dP/dt) were visualized and recorded with Chart 5.5 software (AD Instruments, Colorado Springs, CO).

Heart and lung weights.

Following the hemodynamic studies, the rats were killed and the chest opened. The heart was stopped during diastole by injecting 15% potassium chloride solution, then excised, weighed, and expressed as heart weight-to-body weight (BW) ratio. The LV of the heart was sectioned transversely into five slices from apex to base. One midventricular slice was fixed in 10% formalin and embedded in paraffin. Others were rapidly frozen and kept at −80°C until the assay. The lungs were also excised and weighed.

Hydroxyproline assay.

Collagen content of myocardial tissue was determined by hydroxyproline assay, as described previously (23). Briefly, samples were dried, homogenized, and hydrolyzed with 6 N HCl for 16 h at 110°C. A standard curve of 0–5 μg of hydroxyproline was used. Data were expressed as micrograms of collagen per milligram of dry weight, assuming that collagen contains an average of 13.5% hydroxyproline (8).

Histology.

A transmural section of LV was taken from the midventricle. Sequential 5-μm paraffin-embedded sections were stained with Toluidine blue (Sigma) (11) to visualize mast cells. Mast cell density was determined as the total number of mast cells/LV cross-sectional area. Picrosirius red was used to quantify myocardial interstitial and perivascular collagen deposition and myocyte cross-sectional area (MCSA) (37). Microphotographs of each slide were taken at ×400 magnification using a microscope (IX81, Olympus America, Center Valley, PA) with a digital camera (DP70, Olympus America). Image analysis was performed with a computerized image analysis system (Microsuite Biological imaging software, Olympus America). ICF was detected by calculating the ratio of the collagen area to the entire area of an individual section. Perivascular collagen deposition was measured as the ratio of the fibrosis area surrounding the vessel to total vessel area (43). MCSA was measured separately in the outer half area (close to epicardium) and inner half area (close to endocardium).

Immunohistochemical staining.

Frozen sections (6 μm) were immunostained with ED-1 antibody, which recognizes monocytes/macrophages. Negative controls were processed in a similar fashion, except for the incubation step with primary antibody. Positive cells (with dark brown staining) were counted in high-power fields in each section and expressed as cells per millimeter squared (10).

TGF-β1, -β2, -β3 and phosphorylated Smad3 were determined using Western blot.

Protein (50 μg) from the LV extracts was subjected to 12% SDS-PAGE under nonreducing conditions for TGF-β1, -β2, and -β3, or reducing conditions for phosphorylated Smad3 (p-Smad3) and electrotransferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Membranes were incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C. The primary antibodies were as follows: a monoclonal antibody against TGF-β1, -β2, and -β3 (2 μg/ml; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), a rabbit polyclonal antibody against p-Smad3 (1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology), and a goat polyclonal antibody against actin (1:1,000; Santa Cruz Technology, Santa Cruz, CA). Bound antibodies were visualized by using secondary antibodies with conjugated horseradish peroxidase (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), and ECL-plus chemiluminescence detection system reagent (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) was used to visualize the bands. After p-Smad3 was detected, the blots were stripped with a Western blot stripping buffer (Pierce, Rockford, IL) and reblotted with a rabbit polyclonal antibody against Smad3 (1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology). Films were scanned with an Epson Perfection 3200 Scanner (Epson America, Long Beach, CA). Band density was analyzed with ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health). Densitometric analysis was used to quantify intensity of the bands. TGF-β1, -β2, and -β3 was normalized to actin, and p-Smad3 was normalized to Smad3. The results were expressed as fold increase compared with vehicle. The molecular masses of both pSmad3 and Smad3 are 52 kDa, TGF-β1, -β2, and -β3 are 25 kDa, and actin is 43 kDa.

Data analysis.

All data are expressed as means ± SE. Student's t-test was used to compare mean values of the various parameters (heart weight, lung weight, ICF, PVF, MCSA, SBP, LVEF, E/A ratio, and dP/dt) between different groups, specifically, vehicle vs. Gal-3, and Gal-3 vs. Gal-3 + Ac-SDKP. Hochberg and Benjamini's (15) method for multiple comparisons was used to adjust the α-level of significance.

The authors had full access to the data and take responsibility for its integrity. All authors have read and agree to the paper as written.

RESULTS

BW, SBP, HR, and autopsy findings.

There were no differences in BW, SBP, and HR among groups. In autopsy, we did not observe thickened, rigid pericardium, or adhesions to the surrounding structures. There was no fluid effusion in all rats, including Gal-3-treated rats. Gal-3 significantly increased heart and lung weight compared with vehicle; these changes were blocked by Ac-SDKP (Table 1).

Table 1.

Body weight, systolic blood pressure, heart rate, and heart and lung weight

| Vehicle | Ac-SDKP | Galectin-3 | Galectin-3 + Ac-SDKP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight, g | 447±12 | 456±9 | 487±12 | 457±7 |

| SBP | 116±5 | 107±3 | 110±2 | 109±3 |

| HR | 357±11 | 333±14 | 364±12 | 351±14 |

| Heart weight, mg/100 g | 291±15 | 294±8.2 | 330±5.5* | 287±10‡ |

| Lung weight, mg/100 g | 392±15 | 335±27 | 440±17.5* | 373±20† |

| LVEDD, mm | 7.68±0.17 | 7.55±0.16 | 7.77±0.19 | 7.46±0.21 |

| LVESD, mm | 3.9±0.15 | 3.7±0.2 | 4.3±0.25 | 3.8±0.29 |

Values are means ± SE. Ac-SDKP, N-acetyl-seryl-aspartyl-lysyl-proline; SBP, systolic blood pressure; HR, heart rate; LVEDD, left ventricular end-diastolic dimension; LVESD, left ventricular end-systolic dimension.

P < 0.05, vehicle vs. galectin-3.

P< 0.05 and

P < 0.01, galectin-3 vs. galectin-3 + Ac-SDKP.

Effect of Ac-SDKP on myocardial inflammation induced by Gal-3.

Macrophages (ED-1-positive cells) in the myocardium increased significantly in the Gal-3 treatment group compared with vehicle (P < 0.01). Ac-SDKP significantly reduced macrophage count (P < 0.01, Gal-3 vs. Gal-3 + Ac-SDKP) (Fig. 1). There was also a significant increase in mast cell density in the Gal-3 treatment group compared with vehicle (P < 0.01), which was blocked by Ac-SDKP (P < 0.05). Figure 1 also shows representative microphotographs of mast cell infiltration into the myocardium from rats treated with vehicle, Ac-SDKP, Gal-3, and Gal-3 + Ac-SDKP. The increased mast cell density was more marked in the epicardial myocardium.

Fig. 1.

Effect of N-acetyl-seryl-aspartyl-lysyl-proline (Ac-SDKP) on myocardial macrophage and mast cell infiltration induced by intrapericardial infusion of galectin-3 (Gal-3). Top left: four panels are representative images showing macrophages (brown color with immunohistochemical staining, ×400; black bar = 100 μm). Bottom left: four panels are representative images showing mast cell infiltration (dark blue with toluidine blue staining, ×400; black bar = 100 μm) in the myocardium 4 wk after treatment with vehicle, Ac-SDKP, Gal-3, or Gal-3 + Ac-SDKP. Right: quantitative results of myocardial macrophage (top) and mast cell density (bottom) in 4 treatment groups. *P < 0.05. **P < 0.01.

Effect of Ac-SDKP on cardiac fibrosis and MCSA induced by Gal-3.

LV collagen content (hydroxyproline assay) increased significantly in the Gal-3 group compared with the vehicle group (P < 0.01). This increase was prevented by treatment with Ac-SDKP (P < 0.05) (Table 2). Figure 2, left, shows representative microphotographs of interstitial and perivascular collagen deposition estimated by staining with picrosirius red. The average value of myocardial interstitial and perivascular collagen deposition (Fig. 2) increased significantly in the Gal-3 group compared with vehicle (ICF: P < 0.01, PVF: P < 0.001; vehicle vs. Gal-3). The increases in interstitial and perivascular collagen were partially and completely prevented, respectively, by Ac-SDKP (ICF: P < 0.01, PVF: P < 0.001; Gal-3 vs. Gal-3 + Ac-SDKP). MCSA was increased in Gal-3-treated rats; this change was prevented by Ac-SDKP. The increase in MCSA was greater in the epicardial than in the endocardial area (Fig. 3).

Table 2.

Cardiac collagen content, Ac-SDKP level, and left ventricle dimensions

| Vehicle | Ac-SDKP | Galectin-3 | Galectin-3 + Ac-SDKP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac tissue Ac-SDKP, pg/mg tissue | 76.1±7.4 | 391±128* | 63.5±6.7 | 339.4±129‡ |

| Plasma Ac-SDKP level, pg/μl | 1.58±0.2 | 2.82±0.6 | 1.65±0.2 | 3.1±0.8 |

| Cardiac collagen content, μg/mg dry tissue | 20±2 | 15.1±1.2 | 33.3±3.8† | 22.2±2.3§ |

Values are means ± SE.

P < 0.01, Ac-SDKP vs. vehicle.

P < 0.05, galectin-3 vs. vehicle.

P = 0.056 and

P < 0.05, galectin-3 + Ac-SDKP vs. galectin-3.

Fig. 2.

Effect of Ac-SDKP on myocardial interstitial collagen fraction (ICF) and perivascular fibrosis (PVF) induced by intrapericardial infusion of Gal-3. Left: representative images of ICF and PVF following vehicle, Ac-SDKP, Gal-3, or Gal-3 + Ac-SDKP infusion (Picrosirius red staining, ×400, black bar = 100 μm). Right: quantitative results of ICF and PVF in the 4 groups. **P < 0.01. ***P < 0.001.

Fig. 3.

Effect of Ac-SDKP on cardiomyocyte hypertrophy induced by intrapericardial infusion of Gal-3. Solid bars represent myocyte cross-sectional area of epicardial myocardium (Epi); open bars represent myocyte cross-sectional area of endocardial myocardium (Endo). *P < 0.05. ***P < 0.001.

Effect of Ac-SDKP on TGF-β1, -β2, -β3, and p-Smad3 expression in LV of rats treated with Gal-3.

Gal-3 increased TGF-β1, -β2, and -β3 expression in LV compared with vehicle group; Ac-SDKP inhibited this effect. Gal-3 also increased Smad3 phosphorylation compared with vehicle, and Ac-SDKP prevented this effect (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Effect of Ac-SDKP on myocardial transforming growth factor (TGF)-β expression and Smad3 phosphorylation (p-Smad3) induced by intrapericardial infusion of Gal-3. TGF-β expression (left) and p-Smad3 (right) in the left ventricle were detected by Western blot, showing bands of the typical homodimer (TGF-β: 25 kDa; Smad3: 52 kDa) (top) and quantitative analysis (bottom). *P < 0.05. **P < 0.01. +P = 0.052.

Effect of Ac-SDKP on hemodynamics and cardiac function.

The percent change of amplitude of the −dP/dt from baseline after isoproterenol challenge was decreased in Gal-3-treated rats compared with vehicle (P < 0.05); Ac-SDKP significantly improved this response (P < 0.05, Gal-3 vs. Gal-3 + Ac-SDKP) (Fig. 5). The percent change of amplitude of the +dP/dt from the baseline after isoproterenol challenge was also decreased in the Gal-3-treated rats (vehicle 0.76 ± 0.09, Gal-3 0.53 ± 0.09, P < 0.05). However, Ac-SDKP treatment did not prevent this decrease (0.46 ± 0.01, not significant).

Fig. 5.

Effect of Ac-SDKP on Gal-3 induced reduction of minimum rate of left ventricular change in pressure over time (dP/dt min) (−dP/dt) response to isoproterenol (impairment of left ventricular relaxation). *P < 0.05.

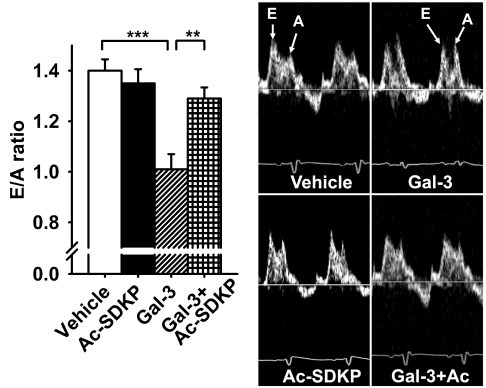

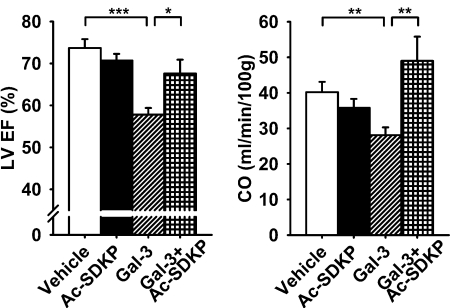

Transmitral Doppler E- (early LV filling phase) to A-wave (atrial contraction phase) ratio was significantly decreased in Gal-3 rats (P < 0.001, vehicle vs. Gal-3), which was prevented by Ac-SDKP (P < 0.01, Gal-3 vs. Gal-3 + Ac-SDKP) (Fig. 6). Intrapericardial delivery of Gal-3 reduced LVEF (P < 0.001) and CO (P < 0.01, vehicle vs. Gal-3); these changes were prevented by Ac-SDKP (LVEF P < 0.05, and CO P < 0.01; Gal-3 vs. Gal-3 + Ac-SDKP) (Fig. 7). There were no differences among groups in LV end-diastolic diameter, although LV end-systolic diameter in Gal-3 group was slightly higher, it did not reach statistical significance compared with vehicle group (Table 2).

Fig. 6.

Effect of Ac-SDKP on Gal-3-induced diastolic dysfunction measured by transmitral Doppler velocity ratio of early left ventricular filling phase to atrial contraction phase (E/A ratio). Right: representative images showing mitral Doppler velocity E/A ratio following vehicle, Ac-SDKP, Gal-3, or Gal-3 + Ac-SDKP treatment. Left: quantitative results of E/A ratio in each group. **P < 0.01. ***P < 0.001.

Fig. 7.

Effect of Ac-SDKP on left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF; left) and cardiac output (CO; right) in Gal-3-induced cardiac dysfunction. *P < 0.05. **P < 0.01. ***P < 0.001.

Ac-SDKP content in cardiac tissue and plasma.

Ac-SDKP content in cardiac tissue was about fivefold higher in intrapericardial Ac-SDKP infusion groups compared with their counterpart vehicle and Gal-3 groups (P < 0.05, vehicle vs. Ac-SDKP; P = 0.056, Gal-3 vs. Gal-3 + Ac-SDKP). The plasma Ac-SDKP levels were elevated in Ac-SDKP and combined Gal-3 plus Ac-SDKP groups compared with their corresponding vehicle and Gal-3 groups; however, the differences are not statistically significant (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic properties of Ac-SDKP are documented in the heart and kidney in the rat model of hypertension and MI (22, 28, 42). In the present study, we further confirmed these protective effects in a different model of cardiac remodeling and dysfunction induced by intrapericardial Gal-3 infusion. We found that Gal-3 enhanced macrophage and mast cell infiltration, as well as collagen deposition in the heart; these were prevented by Ac-SDKP. Ac-SDKP also prevented cardiac hypertrophy and pulmonary congestion, as demonstrated by decreased heart and lung weights. Furthermore, Ac-SDKP improved cardiac function, as shown by increases in LVEF, CO, E/A ratio, and −dP/dt response to isoproterenol. The beneficial effects of Ac-SDKP may be via inhibition of the TGF-β/Smad3 signaling pathway, since we found that Gal-3 markedly increased TGF-β expression, and Smad3 activity in the LV and Ac-SDKP prevents these effects. The presented evidence clearly supports our hypothesis that Ac-SDKP prevents harmful effects of Gal-3 in an inflammatory model of cardiac remodeling and dysfunction.

It is well known that immunological and inflammatory processes play an important role in HF (18). Proinflammatory cytokines, especially the lectin Gal-3 (MAC-2 antigen), not only activates macrophages, but also recently have been shown to drive “alternative” macrophage activation (17), which is involved in organ fibrosis, which is an important component of several cardiovascular diseases. In unstable regions of atherosclerotic plaques, Gal-3 expression is upregulated, and it exacerbates vascular inflammation by stimulating macrophages to express a range of chemokines, including CC chemokines (20). Sharma et al. (35) previously reported that intrapericardial Gal-3 infusion caused macrophage infiltration in the heart and resulted in both cardiac structural changes and dysfunction. Consistent with these findings, we demonstrate here that Gal-3 enhances macrophage and mast cell infiltration, thus generating a microenvironment rich in proinflammatory cytokines, which promote fibrosis. Hence, our data identify Gal-3 as a target for development of new strategies for therapeutic intervention preventing Gal-3's harmful effects. In the present study, we define Ac-SDKP as a viable option. We have shown in vitro that the anti-inflammation mechanism of Ac-SDKP is due to its direct effect on bone marrow stem cells and macrophages, inhibiting their differentiation, activation, and cytokine release (33). Furthermore, Ac-SDKP inhibits DNA and collagen synthesis in cardiac fibroblasts, which suggests that it may be an important endogenous regulator of fibroblast proliferation and collagen synthesis in the heart (29). Not only did we observe that Ac-SDKP prevents cardiac inflammation and fibrosis, but it also inhibits Gal-3-induced cardiac hypertrophy. More importantly, it improves cardiac systolic and diastolic function. The view is generally held that increased collagen content in the heart increases diastolic stiffness and impairs LV relaxation, resulting in LV diastolic dysfunction. Ac-SDKP improved −dP/dt response to isoproterenol and transmitral Doppler E/A ratio, indicating improved diastolic function. In addition, Gal-3 caused a decrease in systolic function, which was prevented by Ac-SDKP. The decrease in systolic function caused by Gal-3 may be due to release of proinflammatory cytokines and superoxides. Ac-SDKP may prevent the decrease in systolic function by its anti-inflammatory effects. We previously reported that, in models of hypertension and HF induced by MI, Ac-SDKP decreased macrophage infiltration and fibrosis in the heart. However, these changes were not associated with improvement of either LVEF or diastolic dysfunction (9, 42). A possible explanation of this discrepancy could be the use of a different model of cardiac dysfunction. In the hypertensive model, the main reason for cardiac dysfunction is probably not inflammation but rather increased afterload that causes hypertrophy, fibrosis, and diastolic dysfunction. While in the post-MI model, the cause of HF is due to a significant decrease of viable myocardium, which results in a major reduction of the ejection fraction. In the Gal-3 pericardial sac infusion model, Gal-3 directly triggers a cardiac inflammatory response, fibrosis, and hypertrophy, with little changes in viable myocardium. In this model, cardiac remodeling and dysfunction are probably a consequence of the inflammatory process caused by Gal-3. Ac-SDKP, likely by blocking inflammatory effects of Gal-3, prevents the lectin's detrimental effects on both cardiac remodeling and dysfunction. Ac-SDKP also promotes angiogenesis (16). Our laboratory previously found that Ac-SDKP stimulated endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and tube formation in vitro and increased myocardial capillary density in vivo (41). This angiogenic property of Ac-SDKP may favorably provide blood flow and oxygen supply to the damaged myocardium, thus improving cardiac function.

The antifibrotic effects of Ac-SDKP appear to involve multiple signaling pathways, including inhibition of expression and effects of TGF-β/Smad signaling and connective tissue growth factor-p42/p44 MAPK (22, 25, 29), which play essential roles in fibrotic and hypertrophic remodeling of the heart (6). We have reported that Ac-SDKP reduces TGF-β production in both post-MI and renal-vascular hypertension models (21, 42). Also, Ac-SDKP further inhibits TGF-β-stimulated Smad2 phosphorylation and reduces cardiac fibrosis (24). In the present study, we further confirmed in our rat model of cardiac dysfunction that Gal-3 markedly increased TGF-β expression and Smad3 activity. Ac-SDKP prevented these effects, suggesting that Ac-SDKP prevents Gal-3-induced cardiac inflammation, fibrosis, and dysfunction, possibly via inhibition of TGF-β/Smad3 signaling pathway. However, we did not find antihypertrophic effects of Ac-SDKP in our laboratory's previous studies on various hypertensive models (21, 24, 30), suggesting that, in the present study, this effect may be involved in a different signaling pathway induced by Gal-3. We found that Gal-3 induced mast cell infiltration mostly in the epicardial area (Fig. 1). Gal-3 increased cross-sectional area of both epicardial and endocardial myocytes, although changes in the epicardium were larger than in the endocardium. Ac-SDKP prevented this hypertrophic effect, suggesting that it worked via either inhibition of mast cell infiltration and/or blocking a direct effect of Gal-3. The involvement of mast cells in cardiac hypertrophy and HF is well documented (4, 36). Mast cells are an important source of cytokines, growth factors, and chemokines, including histamine, TNF-α/NF-κB/IL-6 and renin (4), which are released upon mast cell degranulation. Mast cell-derived chymase appears to be an important source of intracardiac angiotensin II formation. In addition, products released by mast cells, such as TNF-α and ANG II, increase production of reactive oxygen species, which are involved in induction of cardiac hypertrophy.

Finally, to evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of Ac-SDKP by local delivery into the pericardial sac, we measured both cardiac tissue and plasma Ac-SDKP levels and found that myocardial Ac-SDKP levels were fivefold higher in Ac-SDKP groups compared with vehicle or Gal-3 groups (Table 2). However, plasma Ac-SDKP levels were not significantly different among the four groups. These results suggest that this technique provided mainly a local Ac-SDKP therapeutic effect, while limiting systemic side effects of Gal-3.

In summary, this study demonstrated that intrapericardial Gal-3 delivery causes cardiac inflammation, fibrosis, and dysfunction. Simultaneous Ac-SDKP administration prevents detrimental Gal-3-induced effects. The improvements in cardiac function are likely due to decreased cardiac inflammation, fibrosis, and hypertrophy. Also, these preventive effects of Ac-SDKP may be via inhibition of TGF-β/Smad3 signaling pathway. Thus Ac-SDKP treatment may represent a potential therapeutic strategy for halting progression of HF induced by immunological or inflammatory reactions, such as viral myocarditis, rejection posttransplant, or pericarditis.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL28982 (O. A. Carretero) and HL071806 (N.-E. Rhaleb), the Verein zur Förderung des biologisch-technologischen Fortschritts in der Medizin e.V. (Heidelberg, Germany), and the research initiative LMU.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmad N, Gabius HJ, Andre S, Kaltner H, Sabesan S, Roy R, Liu B, Macaluso F, Brewer CF. Galectin-3 precipitates as a pentamer with synthetic multivalent carbohydrates and forms heterogeneous cross-linked complexes. J Biol Chem 279: 10841–10847, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andre S, Unverzagt C, Kojima S, Frank M, Seifert J, Fink C, Kayser K, von der Lieth CW, Gabius HJ. Determination of modulation of ligand properties of synthetic complex-type biantennary N-glycans by introduction of bisecting GlcNAc in silico, in vitro and in vivo. Eur J Biochem 271: 118–134, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azizi M, Rousseau A, Ezan E, Guyene TT, Michelet S, Grognet JM, Lenfant M, Corvol P, Ménard J. Acute angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition increases the plasma level of the natural stem cell regulator N-acetyl-seryl-aspartyl-lysyl-proline. J Clin Invest 97: 839–844, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balakumar P, Singh AP, Ganti SS, Krishan P, Ramasamy S, Singh M. Resident cardiac mast cells: are they the major culprit in the pathogenesis of cardiac hypertrophy? Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 102: 5–9, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belvisi L, Bernardi A, Colombo M, Manzoni L, Potenza D, Scolastico C, Giannini G, Marcellini M, Riccioni T, Castorina M, Logiudice P, Pisano C. Targeting integrins: insights into structure and activity of cyclic RGD pentapeptide mimics containing azabicycloalkane amino acids. Bioorg Med Chem 14: 169–180, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bujak M, Frangogiannis NG. The role of TGF-beta signaling in myocardial infarction and cardiac remodeling. Cardiovasc Res 74: 184–195, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cavasin MA, Liao TD, Yang XP, Yang JJ, Carretero OA. Decreased endogenous levels of Ac-SDKP promote organ fibrosis. Hypertension 50: 130–136, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiariello M, Ambrosio G, Cappelli-Bigazzi M, Perrone-Filardi P, Brigante F, Sifola C. A biochemical method for the quantitation of myocardial scarring after experimental coronary artery occlusion. J Mol Cell Cardiol 18: 283–290, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cingolani OH, Yang XP, Liu YH, Villanueva M, Rhaleb NE, Carretero OA. Reduction of cardiac fibrosis decreases systolic performance without affecting diastolic function in hypertensive rats. Hypertension 43: 1067–1073, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Damoiseaux JGMC, Döpp EA, Calame W, Chao D, MacPherson GG, Dijkstra CD. Rat macrophage lysosomal membrane antigen recognized by monoclonal antibody ED1. Immunology 83: 140–147, 1994. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Enerback L, Kolset SO, Kusche M, Hjerpe A, Lindahl U. Glycosaminoglycans in rat mucosal mast cells. Biochem J 227: 661–668, 1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frangogiannis NG, Smith CW, Entman ML. The inflammatory response in myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res 53: 31–47, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gabius HJ Cell surface glycans: the why and how of their functionality as biochemical signals in lectin-mediated information transfer. Crit Rev Immunol 26: 43–79, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hermans JJ, van Essen H, Struijker-Boudier HA, Johnson RM, Theeuwes F, Smits JF. Pharmacokinetic advantage of intrapericardially applied substances in the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 301: 672–678, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hochberg Y, Benjamini Y. More powerful procedures for multiple significance testing. Stat Med 9: 811–818, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu JM, Lawrence F, Kovacevic M, Bignon J, Papadimitriou E, Lallemand JY, Katsoris P, Potier P, Fromes Y, Wdzieczak-Bakala J. The tetrapeptide AcSDKP, an inhibitor of primitive hematopoietic cell proliferation, induces angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Blood 101: 3014–3020, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacKinnon AC, Farnworth SL, Hodkinson PS, Henderson NC, Atkinson KM, Leffler H, Nilsson UJ, Haslett C, Forbes SJ, Sethi T. Regulation of alternative macrophage activation by galectin-3. J Immunol 180: 2650–2658, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mann DL Inflammatory mediators and the failing heart. Past, present, and the foreseeable future. Circ Res 91: 988–998, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Milting H, Ellinghaus P, Seewald M, Cakar H, Bohms B, Kassner A, Korfer R, Klein M, Krahn T, Kruska L, El BA, Kramer F. Plasma biomarkers of myocardial fibrosis and remodeling in terminal heart failure patients supported by mechanical circulatory support devices. J Heart Lung Transplant 27: 589–596, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Papaspyridonos M, McNeill E, de Bono JP, Smith A, Burnand KG, Channon KM, Greaves DR. Galectin-3 is an amplifier of inflammation in atherosclerotic plaque progression through macrophage activation and monocyte chemoattraction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 28: 433–440, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peng H, Carretero OA, Brigstock DR, Oja-Tebbe N, Rhaleb NE. Ac-SDKP reverses cardiac fibrosis in rats with renovascular hypertension. Hypertension 42: 1164–1170, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peng H, Carretero OA, Liao TD, Peterson EL, Rhaleb NE. Role of Ac-SDKP in the antifibrotic effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in hypertension-induced target organ damage. Hypertension 49: 1–9, 2007.17145983 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peng H, Carretero OA, Raij L, Yang F, Kapke A, Rhaleb NE. Antifibrotic effects of N-acetyl-seryl-aspartyl-lysyl-proline on the heart and kidney in aldosterone-salt hypertensive rats. Hypertension 37: 794–800, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peng H, Carretero OA, Vuljaj N, Liao TD, Motivala A, Peterson EL, Rhaleb NE. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. A new mechanism of action. Circulation 112: 2436–2445, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pokharel S, Rasoul S, Roks AJM, van Leeuwen REW, van Luyn MJA, Deelman LE, Smits JF, Carretero OA, van Gilst WH, Pinto YM. N-acetyl-Ser-Asp-Lys-Pro inhibits phosphorylation of Smad2 in cardiac fibroblasts. Hypertension 40: 155–161, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pokharel S, van Geel PP, Sharma UC, Cleutjens JPM, Bohnemeier H, Tian XL, Schunkert H, Crijns HJGM, Paul M, Pinto YM. Increased myocardial collagen content in transgenic rats overexpressing cardiac angiotensin-converting enzyme is related to enhanced breakdown of N-acetyl-Ser-Asp-Lys-Pro and increased phosphorylation of Smad2/3. Circulation 110: 3129–3135, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prunier F, Gaertner R, Louedec L, Michel JB, Mercadier JJ, Escoubet B. Doppler echocardiographic estimation of left ventricular end-diastolic pressure after MI in rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 283: H346–H352, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rasoul S, Carretero OA, Peng H, Cavasin MA, Zhuo J, Sanchez-Mendoza A, Brigstock DR, Rhaleb NE. Antifibrotic effect of Ac-SDKP and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition in hypertension. J Hypertens 22: 593–603, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rhaleb NE, Peng H, Harding P, Tayeh M, LaPointe MC, Carretero OA. Effect of N-acetyl-seryl-aspartyl-lysyl-proline on DNA and collagen synthesis in rat cardiac fibroblasts. Hypertension 37: 827–832, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rhaleb NE, Peng H, Yang XP, Liu YH, Mehta D, Ezan E, Carretero OA. Long-term effect of N-acetyl-seryl-aspartyl-lysyl-proline on left ventricular collagen deposition in rats with 2-kidney, 1-clip hypertension. Circulation 103: 3136–3141, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saragoca M, Tarazi RC. Impaired cardiac contractile response to isoproterenol in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Hypertension 3: 380–385, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saussez S, Lorfevre F, Nonclercq D, Laurent G, Andre S, Journe F, Kiss R, Toubeau G, Gabius HJ. Towards functional glycomics by localization of binding sites for tissue lectins: lectin histochemical reactivity for galectins during diethylstilbestrol-induced kidney tumorigenesis in male Syrian hamster. Histochem Cell Biol 126: 57–69, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sharma U, Rhaleb NE, Pokharel S, Harding P, Rasoul S, Peng H, Carretero OA. Novel anti-inflammatory mechanisms of N-Acetyl-Ser-Asp-Lys-Pro in hypertension-induced target organ damage. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H1226–H1232, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharma UC, Pokharel S, Evelo CTA, Maessen JG. A systematic review of large scale and heterogeneous gene array data in heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol 38: 425–432, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sharma UC, Pokharel S, van Brakel TJ, van Berlo JH, Cleutjens JPM, Schroen B, André S, Crijns HJGM, Gabius HJ, Maessen J, Pinto YM. Galectin-3 marks activated macrophages in failure-prone hypertrophied hearts and contributes to cardiac dysfunction. Circulation 110: 3121–3128, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shiota N, Rysä J, Kovanen PT, Ruskoaho H, Kokkonen JO, Lindstedt KA. A role for cardiac mast cells in the pathogenesis of hypertensive heart disease. J Hypertens 21: 1935–1944, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sweat F, Puchtler H, Rosenthal SI. Sirius Red F3BA as a stain for connective tissue. Arch Pathol 78: 69–72, 1964. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Amerongen MJ, Harmsen MC, van RN, Petersen AH, van Luyn MJ. Macrophage depletion impairs wound healing and increases left ventricular remodeling after myocardial injury in mice. Am J Pathol 170: 818–829, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Kimmenade RR, Januzzi JL Jr, Ellinor PT, Sharma UC, Bakker JA, Low AF, Martinez A, Crijns HJ, MacRae CA, Menheere PP Pinto YM. Utility of amino-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide, galectin-3, and apelin for the evaluation of patients with acute heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 48: 1217–1224, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Villalobo A, Nogales-González A, Gabius HJ. A guide to signaling pathways connecting protein-glycan interaction with the emerging versatile effector functionality of mammalian lectins. Trends Glycosci Glycotechnol 18: 1–37, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang D, Carretero OA, Yang XY, Rhaleb NE, Liu YH, Liao TD, Yang XP. N-acetyl-seryl-aspartyl-lysyl-proline stimulates angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287: H2099–H2105, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang F, Yang XP, Liu YH, Xu J, Cingolani O, Rhaleb NE, Carretero OA. Ac-SDKP reverses inflammation and fibrosis in rats with heart failure after myocardial infarction. Hypertension 43: 229–236, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhan Y, Brown C, Maynard E, Anshelevich A, Ni W, Ho IC, Oettgen P. Ets-1 is a critical regulator of Ang II-mediated vascular inflammation and remodeling. J Clin Invest 115: 2508–2516, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zimmer HG Measurement of left ventricular hemodynamic parameters in closed-chest rats under control and various pathophysiologic conditions. Basic Res Cardiol 78: 77–84, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]