Abstract

Aldose reductase (AR), a member of the aldo-keto reductase family, has been demonstrated to play a central role in mediating myocardial ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury. Recently, using transgenic mice broadly overexpressing human AR (ARTg), we demonstrated that AR is an important component of myocardial I/R injury and that inhibition of this enzyme protects heart from I/R injury (20–22, 48, 49, 56). To rigorously delineate mechanisms by which AR pathway influences myocardial ischemic injury, we investigated the role played by reactive oxygen species (ROS), antioxidant enzymes, and mitochondrial permeability transition (MPT) pore opening in hearts from ARTg or littermates [wild type (WT)] subjected to I/R. MPT pore opening after I/R was determined using mitochondrial uptake of 2-deoxyglucose ratio, while H2O2 was measured as a key indicator of ROS. Myocardial 2-deoxyglucose uptake ratio and calcium-induced swelling were significantly greater in mitochondria from ARTg mice than in WT mice. Blockade of MPT pore with cyclosphorin A during I/R reduced ischemic injury significantly in ARTg mice hearts. H2O2 measurements indicated mitochondrial ROS generation after I/R was significantly greater in ARTg mitochondria than in WT mice hearts. Furthermore, the levels of antioxidant GSH were significantly reduced in ARTg mitochondria than in WT. Resveratrol treatment or pharmacological blockade of AR significantly reduced ROS generation and MPT pore opening in mitochondria of ARTg mice hearts exposed to I/R stress. This study demonstrates that MPT pore opening is a key event by which AR pathway mediates myocardial I/R injury, and that the MPT pore opening after I/R is triggered, in part, by increases in ROS generation in ARTg mice hearts. Therefore, inhibition of AR pathway protects mitochondria and hence may be a useful adjunct for salvaging ischemic myocardium.

Keywords: mitochondria, mitochondrial permeability transition pore, polyol pathway

mitochondria play a key role in influencing cell death/survival, especially after a stress event in cardiac tissue (5, 8, 12, 63). Mitochondria in ischemic and reperfused hearts have impaired function, a decreased adenine nucleotide content, reduced activities of adenine nucleotide translocase and oxidative phosphorylation enzymes, lower membrane potential, and decreased NADH dehydrogenase activity (8, 11, 13, 15, 16, 27, 29). Mitochondrial permeability transition (MPT), opening of nonselective pores spanning the mitochondrial matrix to the cytosol, has been implicated as a key event in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury. Opening of MPT pore (MPTP) occurs when the mitochondria are exposed to high calcium, along with adenine nucleotide depletion, elevations in phosphate concentrations, membrane depolarization, and/or oxidative stress (5, 8, 11–13, 15, 16, 27, 29, 63). Studies have implicated the MPTP as a key determinant of cell survival (7, 11, 13, 15, 17, 27, 29, 44). It has been shown that opening of MPTP, indeed, plays an important role in necrosis and apoptosis after I/R (7, 17, 27, 29, 44).

Recent studies have demonstrated that polyol pathway or aldose reductase (AR) pathway is a key contributor to myocardial I/R injury, and that inhibition of AR protects myocardium from I/R injury (20–22, 48, 49, 56). Inhibition of AR resulted in improved energy homeostasis (20, 21, 48, 49) and attenuation of the changes in intracellular sodium and calcium (46). Flux via AR has been shown to impact adversely on calcium homeostasis, increase oxidative stress, and impair energy homeostasis (14, 38, 39, 47, 61). Since these conditions are ripe for MPTP opening in myocardium after I/R, we postulated modulation of MPTP opening, in part, due to increases in reactive oxygen species (ROS), is one mechanism by which AR pathway mediates myocardial I/R injury. The AR protein activity in mice is severalfold less than in the hearts of humans and rats (20, 47). Hence, we employed ARTg mice with activity similar to those in humans (20, 47). Using these mice, we show that MPT opening, due in part to increases in ROS, is a key event by which AR pathway mediates myocardial ischemic injury.

METHODS

All studies were performed with the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Columbia University, New York, and conform to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (National Institutes of Health publication no. 85–23, 1996). ARTg mice were obtained from an established breeding colony at Columbia University. Briefly, these transgenic mice were developed by injecting full-length human AR (hAR) cDNA with a mouse major histocompatibility antigen class I promoter (20). These transgenic mice have been backcrossed over 10 generations to obtain mice in the C57BL6 background and were used in our studies. The litters were routinely screened for hAR transgene expression by polymerase chain reaction using primers and conditions described previously (20). Our laboratory has recently conducted studies using these mice and have published in the literature (20). Nontransgenic littermates [wild type (WT)] were used as controls.

I/R Protocol

Hearts were isolated and perfused with Krebs-Henseleit buffer, containing (in mM) the following: 118 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.2 MgCl2, 25 NaHCO3, 5 glucose, 0.4 palmitate, 0.4 BSA, and 70 mU/l insulin, as previously described (20–22, 45). Left ventricular developed pressure (LVDP) and left ventricular end-diastolic pressure were continuously monitored, as previously published (20–22, 45). Hearts were paced at 420 beats/min using electrodes placed on the right atrium. After an equilibration period of 30 min, global ischemia was performed for 25 min in WT and ARTg mice hearts, followed by 60 min of reperfusion.

The following groups of mice were studied.

Untreated WT and ARTg.

Hearts from WT and ARTg mice were perfused with Krebs-Henseleit buffer throughout the I/R protocol.

ARTg-AR inhibitor.

Hearts from ARTg mice were perfused with modified Krebs-Henseleit buffer containing 100 μM zopolrestat [AR inhibitor (ARI)] (this dose gives free acid concentration of 1 μM), starting 10 min before ischemia and continued throughout ischemia and reperfusion. In specific experiments, appropriate WT mice were also perfused similarly with ARI as above. Zopolrestat concentration used here is based on our laboratory's earlier studies (20–22).

Cyclosporin treated.

Hearts from WT (WT-CsA) and ARTg (ARTg-CsA) mice were perfused with Krebs-Henseleit buffer plus 0.2 μM cyclosporin A (CsA) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) throughout the I/R protocol.

Resveratrol treated.

Hearts from WT (WT-Res) and ARTg (ARTg-Res) mice were perfused with Krebs-Henseleit buffer containing 10 μM resveratrol (Res; Sigma) starting 10 min before ischemia and continued throughout ischemia and reperfusion.

Mitochondrial Studies

Measurement of the MPTP.

To determine influence of AR activity on mitochondrial permeability, 2-[3H]deoxyglucose (2-DG) was used to measure MPTP in hearts according to published methods in the literature (27, 29). Briefly, hearts were perfused in recirculating mode with 2-DG (0.1 μCi/ml) for 30 min and were then perfused in the absence of 2-DG for 10 min in a non-recirculating mode. After subjecting the hearts to ischemia and reperfusion, tissues were rapidly excised, weighed, and homogenized in ice-cold buffer (0.25 M sucrose, 20 mM HEPES, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT, and 0.1 mM PMSF) using a tissue tearer (Biospec Products) for 10–15 s and in a glass homogenizer at 4°C. An aliquot of the homogenate was used for counting total 3H after protein precipitation. Mitochondria were prepared from the homogenate by differential centrifugation (43, 54). Homogenate was centrifuged at 750 g for 10 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was further centrifuged at 10,000 g for 10 min (Sorvall model RC- 5C plus) at 4°C. Mitochondrial pellet was washed twice in ice-cold isolation buffer. Part of the mitochondrial fraction was suspended in isolation buffer for measuring citrate synthase (CS) activity. The remaining mitochondrial fraction was assayed for trapped 2-DG in the mitochondria. Mitochondrial entrapment of 2-DG was determined according to published methods (27, 29) and calculated as follows: 105 × (mitochondrial [3H] dpm per unit CS)/(total heart [3H] dpm/g wet wt).

Mitochondrial swelling as a measure of MPTP opening.

We also employed the mitochondrial swelling as a measure of MPTP opening. For measurement of MPTP opening, mitochondria were suspended in freshly prepared swelling buffer (0.2 M sucrose, 10 mM Tris-MOPS, pH 7.4, 5 mM succinate, 1 mM phosphate, 2 μM rotenone, and 1.0 μM EGTA-Tris, pH 7.4) at 0.5 mg/ml, and swelling of mitochondria was monitored by decrease in absorbance at 540 nm in the presence of CaCl2 (5–200 μM). CsA (0.2 μM) was added 2–3 min before CaCl2 to prevent the swelling of mitochondria (64). Extent of pore opening was expressed in terms of changes in absorbance at 540 nm per minute in the presence and absence of Ca2+ and CsA.

Mitochondrial Enzyme Analysis

Isolated, perfused hearts were analyzed for various mitochondrial enzymes associated with electron transport chain, as described in the literature (35, 36, 43, 52). Rotenone-sensitive complex I activity was measured by oxidation of NADH by ubiquinone-1 at 340 nm, complex IV activity was assayed by the oxidation of dithionite reduced cytochrome c at 550 nm, and complex V (oligomycin-sensitive ATP synthase) was determined by the oxidation of NADH in a coupled assay using pyruvate kinase and lactate dehydrogenase at 340 nm. CS was determined at 412 nm.

Measurement of H2O2 Production

To investigate if AR pathway influences mitochondrial ROS generation in hearts after I/R, we measured mitochondrial H2O2 using the oxidation of the fluorogenic indicator amplex red in the presence of horseradish peroxidase (Amplex red kit, Molecular Probes). In a typical experiment, 100 μg of mitochondria were incubated in the presence of horseradish peroxidase( 0.2 U/ml) and amplex red (100 μM) in a final volume of 0.3 ml at room temperature. The signals for H2O2 were linear up to 200 μg of mitochondrial protein. Standard curves were generated with known amounts of H2O2 in the reaction mixture and was linear up to 1 mM. Background fluorescence was measured in the absence of mitochondria and subtracted from the sample readings. Fluorescence was recorded at 530 nm excitation and 590 nm emission wavelengths in a Perkin Elmer L-225-8000 Spectrofluorometer. Results were expressed as nanomoles of H2O2 per milligram mitochondrial protein per minute. Catalase (643 U/ml) was added to ensure the observed increase in fluorescence was due to hydrogen peroxide generated in the reaction. The addition of catalase decreased fluorescence to the basal level. Appropriate controls were included to correct for autofluorescence of Res.

Biochemical measurements.

GSH was measured in homogenate and mitochondrial fractions using the BiotechR GSH-412 TM kit (Oxis Research, Portland, OR). GSH content was determined in the samples as per manufacturer's instructions. Creatine kinase release, a marker of injury due to I/R, was measured in effluents, as published earlier (21–23, 48). Malonaldialdehyde (MDA) and SOD activity in heart homogenates were determined using commercially available kits (MDA 586 and Bioxy Tech SOD-25 from Oxis International).

Statistical Analysis

All data are presented as means ± SD. Statistical significance of differences between control and ARTg hearts was determined by ANOVA. Post hoc comparisons were performed with Tukey or Dunnett procedures using SAS package software, as indicated. Statistical significance was ascribed to the data when P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Mitochondrial Pore Opening During Reperfusion in Mice Hearts

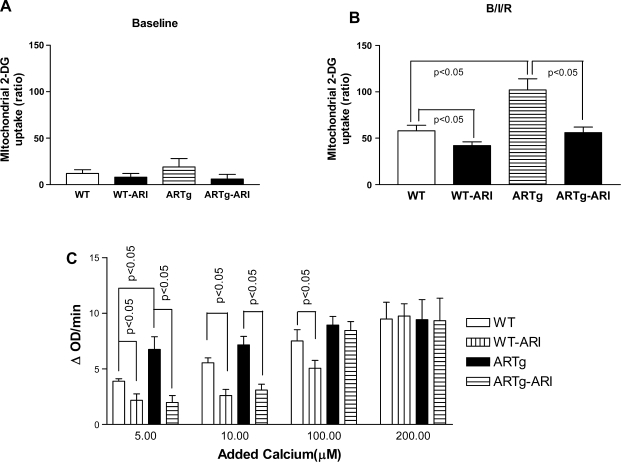

To determine whether AR pathway influences MPTP opening after I/R, two methods were employed. In the first method, the determination of 2-DG phosphate in the isolated mitochondria, a well-documented measure of MPTP opening (27, 29), was used. Under baseline perfusion conditions, mitochondrial entrapment of 2-DG was similar in WT and ARTg mice hearts (Fig. 1A). Mitochondrial entrapment of 2-DG was greater in hearts from ARTg (Fig. 1B) than in WT littermates after I/R. Inhibition of AR with zopolrestat attenuated mitochondrial entrapment of 2-DG in ARTg hearts after I/R. Consistent with earlier studies (27, 29), mitochondrial entrapment of 2-DG was significantly higher in I/R conditions than in baseline perfusion conditions.

Fig. 1.

Mitochondrial permeability in wild-type (WT), human aldose reductase expressing transgenic (ARTg), and aldose reductase inhibited ARTg (ARTg-ARI) (using zopolrestat) mice hearts subjected to ischemia-reperfusion (I/R; n = 6 per group). Mitochondrial permeability transition (MPT) pore opening was determined using 2-[3H]deoxyglucose (2-DG) uptake in the mitochondria of hearts subjected to baseline perfusion (A) or I/R conditions denoted as B/I/R (B) or swelling of mitochondria by measuring light scattering at 540 nm in the presence and absence of varying amounts of added calcium (μM) (n = 6 per group) (C). Data represent means ± SD. Details of the experimental conditions for data are described in methods. ΔOD, change in optical density.

In the second method, we monitored the swelling of mitochondria by measuring light scattering at 540 nm in the presence of varying amounts of added calcium. Figure 1C shows that, at lower concentrations of calcium, the rate of swelling was greater in ARTg mice than in littermates. Pharmacological inhibition of AR blocked mitochondrial swelling in ARTg hearts at low calcium concentrations. Similar effects on swelling of mitochondria were observed in WT hearts treated with an ARI. At higher concentrations of calcium, cardiac mitochondria from all groups had relatively lower calcium-induced changes in absorbance at 540 nm, a finding consistent with earlier studies in mice (60). Addition of CsA, known to inhibit the pore opening (11, 37), abolished the calcium-induced swelling effects in mitochondria from ARTg, ARTg-ARI, and WT hearts (data not shown). The 2-DG entrapment studies and calcium-induced swelling studies suggest that AR pathway influences MPTP opening in mice hearts after I/R.

Involvement of MPTP in Myocardial Ischemic Injury in AR Mice Hearts

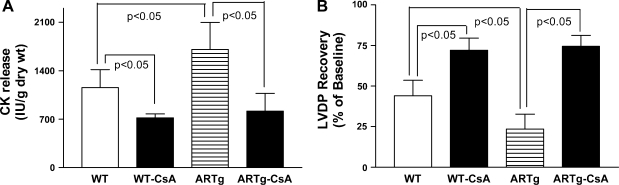

Since CsA has been shown to inhibit opening of MPTPs, we subjected hearts from ARTg and littermate mice to I/R in the presence of CsA and determined whether AR pathway influences myocardial ischemic injury via modulation of MPTP. Creatine kinase release during reperfusion, a marker of ischemic injury, was measured in these studies. The data in Fig. 2A show that myocardial ischemic injury was greater in ARTg vs. littermate hearts (P < 0.05), a finding consistent with our laboratory's earlier publication (20). Myocardial ischemic injury was significantly reduced in CsA-treated ARTg compared with untreated ARTg hearts (P < 0.05). Similarly, in the littermate hearts, perfusion with CsA also resulted in significant reduction of ischemic injury (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Determination of myocardial ischemic injury, as shown by creatine kinase (CK) release (A), and left ventricular developed pressure (LVDP) recovery in WT, ARTg, cyclosporin A (CsA)-treated WT, and CsA-treated ARTg mice hearts subjected to I/R (B). Six hearts per group were studied. Data represent means ± SD. Details of the experimental conditions are described in methods.

Reductions in ischemic injury due to MPTP closing with CsA were associated with improved LVDP recovery after I/R. Data in Fig. 2B demonstrate that inclusion of CsA in perfusion medium improved LVDP recovery in both ARTg and littermate mice hearts. LVDP recovery was impaired in ARTg mice hearts compared with WT littermates (P < 0.05). These data indicate that MPTP opening impacts injury and LVDP recovery due to I/R in mice hearts, with greater impact being observed in ARTg mice hearts.

Mitochondrial ROS

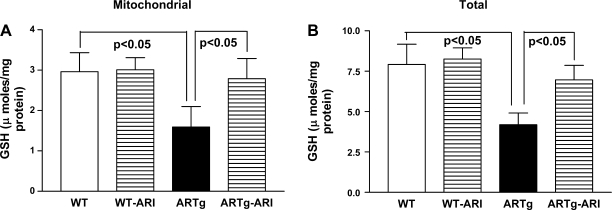

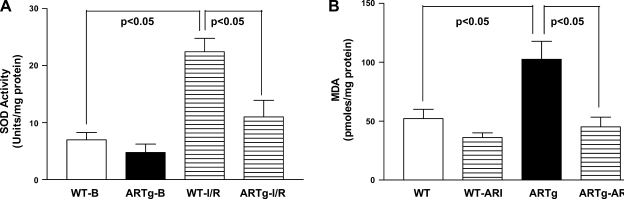

We investigated if AR mediates MPTP opening, at least in part, via increasing oxidative stress. Mitochondrial and total GSH content was significantly reduced in ARTg mice hearts than in WT (Fig. 3) (P < 0.05). Activity of MnSOD was significantly reduced in ARTg mice hearts, compared with WT, after I/R (Fig. 4A). Changes in activities and expression of catalase were similar in ARTg and WT mice hearts subjected to I/R (data not shown). MDA levels were significantly greater in ARTg than in WT mice after I/R (Fig. 4B). Inhibition of AR with ARI reduced MDA content in ARTg (P < 0.05) vs. WT mice exposed to I/R (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 3.

GSH measurements in mitochondrial fractions (A) and total lysates (B) from ARTg, ARTg-ARI, WT, and WT-ARI mice hearts were determined as described in methods. Data represent means ± SD; n = 6–9 per group.

Fig. 4.

A: SOD activity at baseline or after I/R in ARTg and WT heart homogenates. B: malonaldialdehyde (MDA) was measured in heart lysates from WT, WT-ARI, ARTg, and ARTg-ARI after I/R injury. The activity levels were determined using commercially available kits from Oxis. Data represent means ± SD; n = 6 per group.

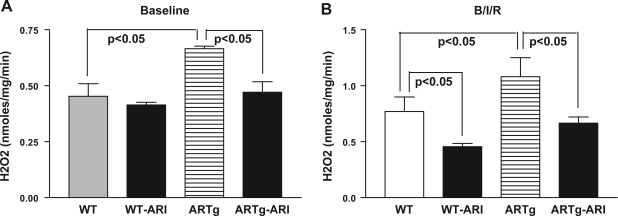

Since reduced GSH content, along with changes in antioxidant enzyme activities in mitochondria, promotes generation of H2O2, we measured changes in mitochondrial H2O2 in ARTg and WT mice hearts, with and without pharmacological intervention. Under baseline conditions, mitochondrial H2O2 was significantly higher in ARTg mice hearts compared with WT hearts (Fig. 5A). Mitochondria from ARTg mice hearts subjected to I/R injury had significantly higher amounts of H2O2 compared with WT hearts (Fig. 5B). Comparing ARTg vs. WT, the net change in H2O2 generation was 0.021 nmol·min−1·mg−1 under baseline and 0.031 nmol·min−1·mg−1 under I/R conditions. Net change in H2O2 was 0.031 nmol·min−1·mg−1 comparing WT baseline vs. WT I/R and 0.042 nmol·min−1·mg−1 comparing ARTg baseline vs. ARTg I/R. These data indicate that the increases in H2O2 were significantly greater in the ARTg group compared with WT under all perfusion conditions. Pharmacological blockade of AR in ARTg mice hearts significantly reduced mitochondrial H2O2 in both perfusion conditions (Fig. 5). These data demonstrating increases in MDA (Fig. 4B) and H2O2 (Fig. 5B) in ARTg hearts indicate increased cardiac oxidative stress in ARTg compared with WT mice.

Fig. 5.

A: measurements of mitochondrial H2O2 after baseline perfusion in WT, WT-ARI, ARTg, and ARTg-ARI, mice hearts. B: H2O2 was measured in isolated mitochondria from the WT, WT-ARI, ARTg, and ARTg-ARI mice hearts after I/R. The details of the amplex red method to measure mitochondrial H2O2 are described in methods. Data represent means ± SD; n = 6 per group.

Mitochondrial Enzymes

To determine whether AR pathway impacts activity of mitochondrial respiratory complexes, we measured activities of specific electron transport chain enzymes in WT and ARTg mice hearts (Table 1). CS activity was similar in mitochondria from WT and ARTg mice hearts. Under baseline conditions, mitochondria from WT and ARTg mice hearts exhibited similar activity profile for complexes I, IV, and V, and CS. Upon I/R, marked deficiencies in activity levels of mitochondrial complex I (33% in WT vs. 92% in ARTg), complex IV (27% in WT vs. 56% in ARTg), and complex V (70% in WT vs. 85% in ARTg) were observed in the ARTg group compared with WT littermate hearts. These enzyme deficits were noted using absolute specific activities for the enzymes or activity ratio to that of CS, a marker enzyme commonly used to normalize mitochondrial content (Table 1). These data indicate that the mitochondrial complexes in ARTg are more prone to damage than those in the WT mice when subjected to I/R. Pharmacological inhibition of AR blocked the reductions in activities of complexes I and V, but not IV, in ARTg mice hearts subjected to I/R. Thus data presented here demonstrate that mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation enzyme changes are critically affected by myocardial ischemic injury in ARTg mice hearts.

Table 1.

Mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation enzymes in mice hearts

| Sample | CS (SA) | Complex I/CS | Complex IV/CS | Complex V/CS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | ||||

| WT | 400±55 | 0.065±0.02 | 0.497±0.07 | 1.23±0.1 |

| ARTg | 370±19 | 0.078±0.02 | 0.629±0.10 | 0.90±0.22 |

| Ischemia-reperfusion | ||||

| WT | 333±54 | 0.061±0.010a | 0.467±0.04d | 0.350±0.095 |

| WT-ARI | 398±29 | 0.039±0.05 | 0.165±0.008 | 0.271±0.037 |

| ARTg | 351±25 | 0.007±0.004b,c | 0.315±0.04e,f | 0.143±0.032 |

| ARTg-ARI | 418±9.7 | 0.024±0.003c | 0.172±0.007e,f | 0.205±0.024 |

Values are means ± SD of activity ratios to citrate synthase; n = 8 hearts/group. Specific activities (SA) for complexes I, IV, V and citrate synthase (CS), expressed as nmol·min−1·mg−1 protein, were determined as described in methods. WT, wild type; ARTg, human aldose reductase transgenic mice; ARI, aldose reductase inhibitor. For complex I activity data,

P < 0.05 comparing WT at baseline vs. WT after ischemia-reperfusion;

P < 0.05 comparing ARTg at baseline vs. ARTg after ischemia-reperfusion;

P < 0.05 comparing WT after ischemia-reperfusion vs. ARTg after ischemia-reperfusion. For complex IV activity data,

P < 0.05 comparing WT at baseline vs. WT after ischemia-reperfusion;

P < 0.05 comparing ARTg at baseline vs. ARTg after ischemia-reperfusion;

P < 0.05 comparing WT after ischemia-reperfusion vs. ARTg after ischemia-reperfusion.

Effect of ROS Reduction on MPT and Ischemic Injury in ARTg Mice Hearts

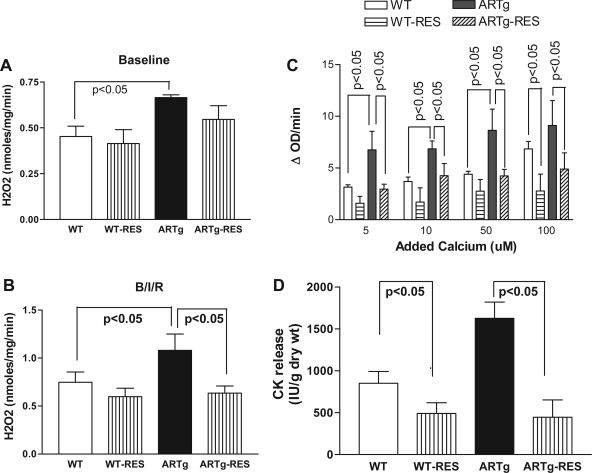

To determine whether blockade of ROS generation during I/R in ARTg hearts is, in part, responsible for MPTP opening, we perfused hearts with Res, a powerful antioxidant (Fig. 6, A and B). Res significantly reduced mitochondrial H2O2 after I/R stress in ARTg hearts (Fig. 6B). The reduction in mitochondrial H2O2 after I/R in ARTg hearts treated with Res was associated with reduction in mitochondrial swelling (Fig. 6, B and C) and attenuation of ischemic injury (Fig 6D). These data demonstrate that ROS generation is a key mechanism by which MPTP opens and mediates ischemic injury in ARTg hearts.

Fig. 6.

Effect of resveratrol (Res) on H2O2 generation by mitochondria under baseline (A) and I/R conditions, denoted as B/I/R (B), Ca2+-induced mitochondrial swelling (C), and ischemic injury (D) in WT and ARTg mice hearts subjected to I/R. Data represent means ± SD; n = 6 in each group. Details of the experimental conditions for data are described in methods.

DISCUSSION

Recent studies have demonstrated the importance of AR pathway in mediating myocardial ischemic injury (20, 21, 26, 46–49, 56). It was also shown that flux via AR pathway in ischemic hearts increases cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio, impairs energy metabolism, reduces Na+-K+-ATPase activity, impairs intracellular sodium and ATP levels, and influences JAK-STAT signaling via protein kinase C (20–22, 26, 46–49, 56). Since the conditions that occur during reperfusion after ischemia, such as high intracellular calcium, ATP depletion, increased phosphate, and oxidative stress, are ideally suited for MPTP opening (11, 13, 15, 16, 27, 29), we investigated if AR pathway mediates ischemic injury via modulation of MPTP properties.

AR and MPTP

The data presented here show that the increased I/R injury in ARTg mice hearts is associated with increased opening of the MPTP. Thus, in the isolated perfused heart, the increased MPTP opening, detected by 2-DG- and calcium-induced (Fig. 1) swelling, was accompanied by increased injury and poor functional recovery (Fig. 2) after I/R. Inhibition of AR using zopolrestat in ARTg hearts resulted in inhibition of MPTP opening (Fig. 1), decreased ischemic injury, and improved functional recovery after I/R (20). In earlier studies, we have shown that AR activity and substrate flux via AR are severalfold greater in ARTg mice hearts than in WT hearts (20), and that attenuation of these changes protects ARTg mice hearts from I/R injury. Therefore, this study links increased opening of the MPTP to increases in AR activity and flux in ARTg mice hearts.

Several studies have shown that opening of MPTP, indeed, plays an important role in I/R injury (7, 11, 13, 15–17, 27, 29, 44). Recent studies have demonstrated that blocking of MPTP opening protects myocardium from I/R injury (7, 17, 27, 29, 44). Studies have also demonstrated that the immunosuppressive drug CsA inhibits MPTP opening and protects myocardium from I/R injury (7, 17, 27, 29, 44). Although CsA can exert additional inhibitory effects at higher doses, the concentrations employed in our study have been shown to be optimal for preferential inhibition of MPTP (11, 37). In our study, we show that perfusion of ARTg mice hearts with CsA reduced ischemic injury and improved functional recovery on reperfusion. Within the limitations of the in vitro mitochondrial studies, the data presented here demonstrate that AR pathway mediates myocardial ischemic injury, in part, by opening MPTP in mice hearts.

AR, ROS, MPTP, and Ischemic Injury

Several mechanisms can be postulated to explain the action by which AR might impact MPTP opening. Foremost among them is the hypothesis that AR leads to glutathione depletion and increases ROS (58, 59). For this reason, we assessed the activity levels of oxidant stress enzymes in the hearts of mice before I/R injury. Reductions in GSH and SOD activity are likely to favor increases in H2O2 in ARTg mice hearts, as shown in this study (Fig. 5), and are indicative of the high-oxidant stress environment in amplifying injury in the ARTg mice hearts. In the myocardium, accumulation of excessive ROS production has been linked to MPTP opening and injury after I/R. In this study, we demonstrate that mitochondrial H2O2 generation was significantly higher in ARTg mice hearts compared with WT hearts under all perfusion conditions. It is evident from our data that net changes in mitochondrial H2O2 of 0.031 nmol·min−1·mg−1 or above elicits significant increases in MPTP opening. Furthermore, we demonstrate that pharmacological blockade of AR in ARTg mice heart results in significant reduction of mitochondrial H2O2, attenuation of MPTP opening, and reduction in injury after I/R. Similarly, perfusion with Res was associated with reduction in mitochondrial H2O2, attenuation of MPTP opening, and reduction in injury after I/R in ARTg mice hearts. Although Res has been shown to mediate some of the beneficial effects via SIRT1 (31, 62), reduction in oxidative stress and protection of ischemic hearts by Res in this study are consistent with earlier studies demonstrating antioxidant properties of Res in the cardiac system (2, 6, 25, 50). Our findings here are consistent with the earlier studies (4, 55), demonstrating that increased oxidative stress is an important mechanism by which MPTP opening is increased in ARTg hearts subjected to I/R.

Our data presented here demonstrating increased oxidative stress in ARTg mice hearts subjected to I/R are consistent with data from other studies that have implicated increases in flux via AR to increased oxidative stress. Studies by Iwata et al. (26) demonstrated that AR overexpressing mouse hearts exhibit increased injury and poor functional recovery after myocardial I/R, and that these changes are due to increased oxidative stress. Mice expressing hAR exhibit greater injury and greater MDA content than WT mice with lower AR activity (34). It has also been shown that AR null mice exhibit reduced oxidative stress and are protected against ischemic injury (34). In rat hearts subjected to I/R, increases in polyol pathway activity have been shown to increase iron accumulation and exacerbation of oxidative damage (54). Furthermore, studies have shown that AR inhibition in animals does not cause increases in lipid peroxidation products (3, 18, 32, 39), and that ARI-treated hyperglycemic animals show reductions in diabetic vascular complications and not accelerated pathological changes. Only discordant findings to date have been in a rabbit model of ischemic preconditioning by Shinmura et al. (51). Thus overwhelming evidence in the literature support our findings demonstrating that AR increases oxidative stress under conditions of I/R, thereby contributing to increased injury.

AR and Mitochondrial Enzymes

Mitochondrial electron transport chain complexes are known to contribute to ROS production and to be impacted by continued production of ROS. In particular, potential contribution from complex I, complex III of electron transport chain, and mitochondrial glycerol phosphate dehydrogenase and succinate-ubiquinone oxido reductase toward electron leakage and ROS production has been widely described (24, 30, 33, 40, 41, 42). I/R injury has been shown to impair mitochondrial respiration by impacting oxidative phosphorylation enzymes in the mitochondria (9, 24, 30, 33, 40, 42). Complex I has previously been shown, in part, to be responsible for increased ROS generation (1, 53, 57). Inhibition of AR, in I/R, blocked reductions in complex I and V activities, but not complex IV, in ARTg mice hearts (Table 1). Since defects in mitochondrial ATPase have been associated with decrease in mitochondrial ATP content (19), improved complex V activity with inhibition of AR may, in part, be responsible for improved ATP content in ARTg mice hearts after I/R (20). The data presented in this study are consistent with earlier studies that have demonstrated a link between increased generation of mitochondrial H2O2 and greater reductions in activities of complexes I, IV, and V. While we have discussed potential pathways by which AR can impact ROS, the precise mechanisms by which AR increases ROS and the sequence of changes in mitochondrial complexes and or other components impacting oxidative stress are yet to be elucidated. Taken together, increased flux through polyol pathway enzyme, AR, is a major contributing factor toward mitochondrial dysfunction, assessed by reduced activity levels of oxidative phosphorylation enzymes.

Future Directions

While we have focused on the role of ROS in opening MPTP in ARTg mice hearts, other factors influencing MPTP, such as intracellular calcium, ATP depletion, cytosolic NADH/NAD+, NADPH, and associated changes in protein kinases in cell death/survival signaling (28), need to be explored.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that MPTP opening is a key event by which AR pathway mediates myocardial I/R injury. Furthermore, we show that the MPTP opening after I/R is triggered, in part, by increases in ROS generation in ARTg mice hearts. Therefore, inhibition of AR pathway protects mitochondria and hence may be a useful adjunct for salvaging ischemic myocardium.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HL61783, HL68954, and HL60901, and Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bernardi P, PetronelliV, Di Lisa F, Forte M. A mitochondrial perspective on cell death. Trends Biochem Sci 26: 112–117, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bezstarosti K, Das S, Lamers JM, Das DK. Differential proteomic profiling to study the mechanism of cardiac pharmacological preconditioning by resveratrol. J Cell Mol Med 10: 896–907, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 3.Chung SS, Ho EC, Lam KS, Chung SK. Contribution of polyol pathway to diabetes-induced oxidative stress. J Am Soc Nephrol 8, Suppl 3: S233–S236, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clarke SJ, Khaliulin I, Das M, Parker JE, Heesom KJ, Halestrap AP. Inhibition of mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening by ischemic preconditioning is probably mediated by reduction of oxidative stress rather than mitochondrial protein phosphorylation. Circ Res 102: 1082–1090, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crompton M The mitochondrial permeability transition pore and its role in cell death. Biochem J 341: 127–132, 1999. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dekkers DH, Bezstarosti K, Gurusamy N, Luijk K, Verhoeven AJ, Rijkers EJ, Demmers JA, Lamers JM, Maulik N, Das DK. Identification by a differential proteomic approach of the induced stress and redox proteins by resveratrol in the normal and diabetic rat hearts. J Cell Mol Med 12: 1677–1689, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Di Lisa F, Manabo R, Canton M, Barile M, Bernardi P. Opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore causes depletion of mitochondrial and cytosolic NAD+ and is a causative event in the death of myocytes in postischemic reperfusion of the heart. J Biol Chem 276: 2571–2575, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Di Lisa F, Menabo R, Siliprandi N. L-propionyl-carnitine protection of mitochondrial in ischemic rat hearts. Mol Cell Biochem 88: 169–173, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drahota Z, Chowdhury SK, Floryk D, Mracek T, Wilhelm J, Rauchova H, Lenaz G, Houstek J. Glycerophosphate-dependent hydrogen peroxide production by brown adipose tissue mitochondria and its activation by ferricyanide. J Bioenerg Biomembr 34: 105–113, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goh SS, Woodman OL, Pepe S, Cao AH, Qin C, Ritchie RH. The red wine antioxidant resveratrol prevents cardiomyocyte injury following ischemia-reperfusion via multiple sites and mechanisms. Antioxid Redox Signal 9: 101–113, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Griffiths EJ, Halestrap AP. Protection by Cyclosporin A of ischemia/reperfusion-induced damage in isolated rat hearts. J Mol Cell Cardiol 25: 1461–1469, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griffiths EJ, Halestrap AP. Mitochondrial non-specific pores remain closed during cardiac ischaemia, but open upon reperfusion. Biochem J 307: 93–98, 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gunther TE, Pfeiffer DR. Mechanisms by which mitochondria transport calcium. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 258: C755–C786, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta S, Chough E, Daley J, Oates P, Tornheim K, Ruderman NB, Keaney Jr JF. Hyperglycemia increases endothelial superoxide that impairs smooth muscle cell Na+-K+-ATPase activity. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 282: C560–C566, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halestrap AP, Connern CP, Griffiths EJ, and Kerr PM. Cyclosporin A binding to mitochondrial cyclophilin inhibits the permeability transition pore and protects hearts from ischaemia/reperfusion injury. Mol Cell Biochem 174: 167–172, 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hardy DL, Clark JB, Usmar V, Smith DR, Stone D. Reoxygenation dependent decrease in mitochondrial NADH CoQ reductase activity in hypoxic-reoxygenated rat heart. Biochem J 274: 133–137, 1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hausenloy DJ, Maddock HL, Baxter GF, Yellon DM. Inhibiting mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening: a new paradigm for myocardial preconditioning? Cardiovasc Res 55: 534–543, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ho ECM, Lam KSL, Chen YS, Yip JCW, Arvindakshan M, Yamagishi S, Yagihashi S, Oates PJ, Ellery CA, Chung SSM, Chung SK. Aldose reductase-deficient mice are protected from the delayed motor nerve conduction velocity and increased JNK activation, depletion of reduced glutathione and increased superoxide accumulation and DNA damages. Diabetes 55: 1946–1953, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Houstek J, Klement P, Floryk D, Antonicka H, Hermanska J, Kalous M, Hansikova H, Hout'kova H, Chowdhury SK, Rosipal T, Kmoch S, Stratilova L, Zeman J. A novel deficiency of mitochondrial ATPase of nuclear origin. Hum Mol Genet 8: 1967–1974, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hwang YC, Kaneko M, Bakr S, Liao H, Lu Y, Lewis ER, Yan SD, Ii S, Itakura M, Rui L, Skopicki H, Homma S, Schmidt AM, Oates PJ, Szabolcs M, Ramasamy R. Central role for aldose reductase pathway in myocardial ischemic injury. FASEB J 18: 1192–1199, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hwang YC, Sato S, Tsai JY, Bakr S, Yan SD, Oates PJ, Ramasamy R. Aldose reductase activation is a key component of myocardial response to ischemia. FASEB J 16: 243–245, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hwang YC, Shaw S, Kaneko M, Redd H, Marerro M, Ramasamy R. Aldose reductase pathway mediates JAK-STAT signaling: a novel axis in myocardial ischemic injury. FASEB J 19: 795–797, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hwang YC, Bakr S, Ellery CR, Oates PJ, Ramasamy R. Sorbitol dehydrogenase: a novel target for adjunctive protection of ischemic myocardium. FASEB J 17: 2331–2333, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ide T, Tsutsui H, Hayashidani S, Kang D, Suematsu N, Nakamura K, Utsumi H, Hamasaki N, Takeshita A. Mitochondrial DNA damage and dysfunction associated with oxidative stress in failing hearts after myocardial infarction. Circ Res 88: 529–535, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Imamura G, Bertelli AA, Bertelli A, Otani H, Maulik N, Das DK. Pharmacological preconditioning with resveratrol: an insight with iNOS knockout mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 282: H1996–H2003, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iwata K, Matsuno K, Nishinaka T, Persson C, Yabe-Nishimura C. Aldose reductase inhibitors improve myocardial reperfusion injury in mice by a dual mechanism. J Pharm Sci 102: 37–46, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Javadov SA, Lim KH, Kerr PM, Suleiman MS, Angelini GD, Halestrap AP. Protection of hearts from reperfusion injury by propofol is associated with inhibition of the mitochondrial permeability transition. Cardiovasc Res 45: 360–369, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Juhaszova M, Zorov DB, Kim SH, Pepe S, Fu Q, Fishbein KW, Ziman BD, Wang S, Ytrehus K, Antos CL, Olson EN, Sollott SJ. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta mediates convergence of protection signaling to inhibit the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. J Clin Invest 113: 1535–1549, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kerr PM, Suleiman MS, Halestrap AP. Reversal of permeability transition during recovery of hearts from ischemia and its enhancement by pyruvate. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 276: H496–H502, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kwong LK, Sohal RS. Substrate and site specificity of hydrogen peroxide generation in mouse mitochondria. Arch Biochem Biophys 350: 118–126, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lagouge M, Argmann C, Gerhart-Hines Z, Meziane H, Lerin C, Daussin F, Messadeq N, Milne J, Lambert P, Elliott P, Geny B, Laakso M, Puigserver P, Auwerx J. Resveratrol improves mitochondrial function and protects against metabolic disease by activating SIRT1 and PGC-1alpha. Cell 127: 1109–1122, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee AYW, Chung SS. Contributions of polyol pathway to oxidative stress in diabetic cataract. FASEB J 13: 23–30, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lesnefsky EJ, Chen Q, Moghaddas S, Hassan MO, Tandler B, Hoppel CL. Blockade of electron transport during ischemia protects cardiac mitochondria. J Biol Chem 279: 47961–47967, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lo AC, Cheung AK, Hung VK, Yeung CM, He QY, Chiu JF, Chung SS, Chung SK. Deletion of aldose reductase leads to protection against cerebral ischemic injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 27: 1496–1509, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marin-Garcia J, Ananthakrishnan R, Agrawal N, Goldenthal MJ. Mitochondrial gene expression during bovine cardiac growth and development. J Mol Cell Cardiol 26: 1029–1036, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marin-Garcia J, Ananthakrishnan R, Goldenthal MJ. Heart mitochondria response to alcohol is different than brain and liver. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 19: 1463–1466, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nazareth W, Yafei N, Crompton M. Inhibition of anoxia-induced injury in heart myocytes by cyclosporin A. J Mol Cell Cardiol 23: 1351–1354, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Obrosova IG Increased sorbitol pathway activity generates oxidative stress in tissue sites for diabetic complications. Antioxid Redox Signal 7: 1543–1552, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Obrosova IG, Minchenko AG, Vasupuram R, White L, Abatan OI, Kumagai AK, Frank RN, Stevens MJ. Aldose reductase inhibitor fidarestat prevents retinal oxidative stress and vascular endothelial growth factor overexpression in streptozotocin-diabetic rats. Diabetes 52: 864–871, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paradies G, Petrosillo G, Pistolese M, Di Venosa N, Federici A, Ruggiero FM. Decrease in mitochondrial complex I activity in ischemic/reperfused rat heart: involvement of reactive oxygen species and cardiolipin. Circ Res 94: 53–59, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pellici G, Lanfrancone L, Grignani F, Mcglade J, Cavallo F, Forni G, Nicoletti I, Grignani F, Pawson T, Pellici PG. A novel transforming protein (SHC) with an SH2 domain is implicated in mitogenic signal transduction. Cell 70: 93–104, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Petrosillo G, Ruggiero FM, Di Venosa N, Paradies G. Decreased complex III activity in mitochondria isolated from rat heart subjected to ischemia and reperfusion: role of reactive oxygen species and cardiolipin. FASEB J 17: 714–716, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ragan C, Wilson M, Darley-Usmar V, Lowe P. Mitochondria, A Practical Approach, edited by Darley-Usmar V, Rickwood D, Wilson MT. Oxford, UK: IRL, 1987, p. 79–112.

- 44.Rajesh KG, Sasaguri S, Zhitian Z, Suzuki R, Asakai R, Maeda H. Second window of ischemic preconditioning regulates mitochondrial permeability transition pore by enhancing Bcl-2 expression. Cardiovasc Res 59: 297–307, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ramasamy R, Hwang YC, Whang J, Bergmann SR. Protection of ischemic hearts by high glucose is mediated by the glucose transporter, GLUT-4. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 281: H290–H297, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ramasamy R, Liu H, Oates PJ, Schaefer S. Attenuation of ischemia induced increases in sodium and calcium by an aldose reductase inhibitor zopolrestat. Cardiovasc Res 42: 130–139, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ramasamy R, Oates PJ. Aldose reductase and vascular stress. In: Text Book of Diabetes Mellitus and Cardiovascular Disease, edited by Marso SP and Stern DM. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003, p. 55–74.

- 48.Ramasamy R, Oates PJ, Schaefer S. Aldose reductase inhibition improves the altered glucose metabolism of isolated diabetic rat hearts. Diabetes 46: 292–300, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ramasamy R, Trueblood NA, Schaefer S. Metabolic effects of aldose reductase inhibition during low-flow ischemia and reperfusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 275: H195–H203, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ray PS, Maulik G, Cordis GA, Bertelli AA, Bertelli A, Das DK. The red wine antioxidant resveratrol protects isolated rat hearts from ischemia reperfusion injury. Free Radic Biol Med 27: 160–169, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shinmura K, Bolli R, Liu SQ, Tang XL, Kodani E, Xuan YT, Srivastava S, Bhatnagar A. Aldose reductase is an obligatory mediator of the late phase of ischemic preconditioning. Circ Res 91: 240–246, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Srere PA Citrate synthase. Methods Enzymol 13: 3–11, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sugioka K, Nakano M, Totsune-Nakano H, Minakami H, Tero-kubota S, Ikegami Y. Mechanism of O2-generation in reduction and oxidation cycle of ubiquinone in a model mitochondrial electron transport system. Biochim Biophys Acta 936: 377–385, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tang WH, Wu S, Wong TM, Chung SK, Chung SS. Polyol pathway mediates iron-induced oxidative injury in ischemic-reperfused rat heart. Free Radic Biol Med. 45: 602–610, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Townsend PA, Davidson SM, Clarke SJ, Khaliulin I, Carroll CJ, Scarabelli TM, Knight RA, Stephanou A, Latchman DS, Halestrap AP. Urocortin prevents mitochondrial permeability transition in response to reperfusion injury indirectly, by reducing oxidative stress. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H928–H938, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tracey WR, Magee WP, Ellery CA, MacAndrew JT, Smith AH, Knight DR, Oates PJ. Aldose reductase inhibition alone or combined with an adenosine A(3) agonist reduces ischemic myocardial injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 279: H1447–H1452, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Turrens JF, Boveris A. Generation of superoxide anion by the NADH dehydrogenase of bovine heart mitochondria. Biochem J 191: 421–427, 1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vikramadithyan RK, Hu Y, Noh H, Liang CP, Hallam K, Tall AR, Ramasamy R, Goldberg IJ. Human aldose reductase expression accelerates diabetic atherosclerosis in transgenic mice. J Clin Invest 115: 2434–2443, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vincent AM, Russell JW, Low P, Feldman EL. Oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of diabetic neuropathy. Endocr Rev 25: 612–628, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang G, Liem DA, Vondriska TM, Honda HM, Korge P, Pantaleon DM, Qiao X, Wang Y, Weiss JN, Ping P. Nitric oxide donors protect murine myocardium against infarction via modulation of mitochondrial permeability transition. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288: H1290–H1295, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Williamson JR, Chang K, Frangos M, Hasan KS, Ido Y, Kawamura T, Nyengaard JR, Van den Enden M, Kilo C, Tilton RG. Hyperglycemic pseudohypoxia and diabetic complications. Diabetes 42: 801–813, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang H, Baur JA, Chen A, Miller C, Adams JK, Kisielewski A, Howitz KT, Zipkin RE, Sinclair DA. Design and synthesis of compounds that extend yeast replicative lifespan. Aging Cell 6: 35–43, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zamzami N, Kroemer G. The mitochondrion in apoptosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2: 67–71, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zamzami N, Maisse C, Metivier D, Kroemer G. Measurement of membrane permeability and permeability transition of mitochondria. Methods Cell Biol 65: 147–158, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]