Abstract

We tested the hypothesis that lymphatics would exhibit myogenic constrictions and dilations to intraluminal pressure changes. Collecting lymphatic vessels were isolated from rat mesentery, cannulated, and pressurized for in vitro study. The lymphatic diameter responses to controlled intraluminal pressure steps of different magnitudes were tested in the absence and presence of the inflammatory mediator substance P, which is known to enhance lymphatic contractility. Myogenic constriction, defined as a time-dependent decrease in end-diastolic diameter over a 1- to 2-min period following pressure elevation (after initial distension), was observed in the majority of rat mesenteric lymphatic vessels in vitro and occurred over a relatively wide pressure range (1–15 cmH2O). Myogenic dilation, a time-dependent rise in end-diastolic diameter following pressure reduction, was observed in over half the vessels equilibrated at a low baseline pressure. Myogenic constrictions were independent of the cardiac-like and time-dependent compensatory decline in end-systolic diameter and increase in amplitude observed in almost all vessels following pressure elevation. Substance P increased the percentage of vessels exhibiting myogenic constriction, the magnitude and rate of constriction, and the pressure range over which constriction occurred. Our results demonstrate that myogenic responses occur in collecting lymphatic vessels and suggest that the response may aid in preventing vessel overdistension during inflammation/edema.

Keywords: lymphatic contraction, lymphatic contractility, substance P, inflammation

lymph formation and propulsion are determined by the interplay of multiple factors, both passive and active, that control how lymphatic vessels behave as pumps and/or conduits (20, 23, 24, 44). Passive factors influencing lymph propulsion include hydrostatic pressure gradients across and along lymphatic vessels, tissue compression, respiratory movements, and gravitational forces (45, 46). Active lymph propulsion is achieved by the spontaneous, rhythmic contractions of collecting lymphatic vessels, which serve as an essential pump mechanism to propel lymph uphill against a hydrostatic pressure gradient from peripheral lymphatics through lymph nodes into the thoracic duct (29, 50).

The lymphatic pump exhibits cardiac-like behavior in several respects, such that pump performance can be analyzed using cardiac indexes (4, 26, 36, 42). For example, collecting lymphatics exhibit intrinsic compensation to changes in input (preload) or output (afterload) pressure (18, 21, 24, 39, 49). Other aspects of lymphatic vessel behavior resemble those of blood vessels. Similar to arterioles, lymphatics have a certain degree of basal tone (21, 22) and respond to imposed, intraluminal flow gradients (23, 33); in contrast to arterioles, lymphatics also respond to flow transients associated with the lymphatic contraction cycle (25).

Blood vessels, notably small arteries and arterioles, typically exhibit myogenic reactions to changes in intravascular pressure (3). Although the term “myogenic response” has been used to describe various responses of blood vessels to altered pressure or stretch, these are often distinct phenomena that more accurately fit under a broader heading of “myogenic behavior” (13). A narrower and more precise definition of the term myogenic response is constriction to elevated pressure or dilation to reduced pressure (12). In this sense of the term, myogenic responses are exhibited by arterioles, small arteries, and, to some extent, veins but are most pronounced in small- to intermediate-sized arterioles, where they are important for local control of blood flow and capillary pressure (13). Whether lymphatics exhibit myogenic responses in this stricter sense of the term is not known.

The term “lymphatic myogenic response” has been used previously in a broad sense to refer to a number of intrinsic adaptations of the lymphatic pump to hydrostatic forces (2, 42). Although the literature is replete with examples of lymphatic contraction patterns at various steady-state pressure levels (22, 23, 33, 39, 42), few continuous records of the lymphatic response to acute pressure changes have been published (40, 49). In the course of a recent study (10), we consistently observed what appeared to be myogenic constrictions to rapid pressure elevation. The constriction was evident as a time-dependent decrease in end-diastolic diameter (EDD) over a 1- to 2-min period following pressure elevation. The purpose of the present study was to determine the magnitude of the lymphatic myogenic response and the conditions under which it occurs.

METHODS

Vessel isolation.

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (170–260 g body wt) were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (Nembutal; 100 mg/kg ip), and a loop of duodenum from each animal was exteriorized through a midline abdominal incision. All animal protocols were approved by the University of Missouri Animal Care and Use Committee and conformed to US Public Health Service policy for the humane care and use of laboratory animals (PHS Policy, 1996). Collecting lymphatic vessels (90–160 μm ID, 1–2 mm long) were dissected from their paired mesenteric small arteries/veins in MOPS-buffered, albumin-supplemented physiological saline solution (APSS) at room temperature. After removal of connective tissue and fat, each vessel was transferred to a 3-ml chamber for cannulation, pressurization, and subsequent isobaric studies. The animal was euthanized with pentobarbital sodium (200 mg/kg ic).

Solutions.

APSS contained 145.0 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 2.0 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 1.2 mM NaH2PO4, 0.02 mM EDTA, 5.0 mM glucose, 2.0 mM sodium pyruvate, 3.0 mM MOPS, and 0.5 g/100 ml purified BSA (pH 7.4 at 37°C). Initially, pipette and bath solutions were APSS, but after vessel cannulation and equilibration, the external solution was changed to an identical solution without albumin. Ca2+-free APSS was identical to APSS, except for substitution of 3.0 mM EDTA for CaCl2. All chemicals were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO), except albumin (catalog no. 10856), which was obtained from US Biochemicals (Cleveland, OH).

Pressure control method.

Vessel segments used for these protocols had at most one valve to ensure adequate pressure control in the entire segment (1–2 mm total length). For study of isobaric contractions, the lymphatic segment was cannulated at each end with a glass micropipette on a Burg-style V-track system (17) and pressurized on the stage of an inverted microscope. Pressure was initially set to 3 cmH2O from a single standing reservoir during 30–60 min of equilibration. Diameter changes were continuously tracked by computer (7). To control the rate of change in intraluminal pressure (dP/dt), the pipette connections were switched from the reservoir to a servo-controlled pressure system, consisting of a servo-null-style shaker pump driven by a hardware-based servo controller through a unitary-gain power amplifier (15). The controller compared the output signal from a low-pressure transducer (model 104, CyQ, Nicholsville, KY) with a reference voltage specified by a computer and adjusted the pump voltage accordingly. A T-tube connector was used to pressurize both pipettes from a single pressure source to ensure that no axial pressure gradient was imposed (23, 25). The diameter and pressure signals were recorded using an analog-digital–digital-analog interface (model PCI 6030e, National Instruments). For diameter tracking, the image was digitized with a 1,632 × 1,234 pixel firewire camera (model A641FM, Basler, Ahrensburg, Germany) at 15 Hz and processed as previously described (7). Only the top half of the video field was acquired to increase the video throughput to 30 Hz. All diameters reported in this study are internal diameters.

Protocols.

Each vessel was equilibrated for 30–60 min at 3 cmH2O and 37°C until a stable pattern of spontaneous contractions developed. During this time, the diameter tracking system was adjusted to give accurate recordings of internal diameter. The bath solution was changed every ∼30 min to minimize changes in osmolarity associated with evaporation. Criteria for viable vessels included 1) the development of spontaneous tone, particularly at pressures <3 cmH2O, 2) the development of spontaneous contractions during the equilibration period, the amplitude of which was ≥30% of the maximal passive diameter at the equilibration pressure, and 3) contractions that were reasonably uniform over the entire length of the vessel (i.e., not just in a single spot). Vessels that did not meet these criteria were discarded. In addition, data sets from vessels that developed irregular contraction patterns during an experiment were not used for subsequent analysis.

For step pressure protocols, pressure was set to one of four baseline levels (0.5, 1, 3, or 5 cmH2O) for several minutes until a new contraction pattern stabilized. This pressure range overlaps the hydrostatic pressure range (2–5 cmH2O) in vivo, under conditions approximating normal tissue hydration, based on the few published measurements of lymphatic pressure in rat mesentery (4, 26, 28). The vessel was then subjected to a series of rapid pressure steps (+2, +4, +6, +8, +10, and +12 cmH2O), for 2–5 min at each step, with return to baseline pressure for 3–10 min before the next pressure step. After completion of the pressure step series, usually in sequential order, SP (3 × 10−8 M) was applied to the bath and the same series of pressure steps was repeated. For ramp pressure protocols, pressure was initially set at 0.5 cmH2O and then ramped to 3 cmH2O at one of five different rates, such that the ramp was complete in ∼30, 15, 6, 3, or 1.5 min. A rapid pressure step from 0.5 to 3 cmH2O was also tested on the same vessel. After 3–5 min at 3 cmH2O, pressure was returned to 0.5 cmH2O for 5–10 min until a stable contraction pattern redeveloped. Subsequently, another ramp was performed. This sequence was repeated until all five ramp rates were tested in pseudorandomized order.

At the end of each experiment, the vessel was equilibrated for 30 min in Ca2+-free APSS at 37°C, and then passive diameters were determined for each previous step or ramp pressure sequence.

Data analysis.

After completion of an experiment, custom analysis routines written in LabView were used to detect the diameter maxima and minima associated with each contraction cycle and the contraction frequency (FREQ) before, during, and after the pressure steps or ramps. Frequency was computed on a contraction-by-contraction basis. Other contraction parameters were calculated as follows

|

(1) |

where EDD is end-diastolic diameter and ESD is end-systolic diameter at any given pressure

|

(2) |

where MaxD is the maximal passive diameter at the respective pressure

|

(3) |

where EDD1 is the EDD associated with the first contraction after the pressure step

|

(4) |

|

(5) |

where Ri is the initial end-diastolic radius, Rf is the final end-diastolic radius after a steady-state constriction was achieved, and Pi and Pf represent the baseline pressure and the final pressure after the pressure step (in mmHg).

Data sets were analyzed using Excel and JMP 5.1 (SAS, Cary, NC). In most cases, one-way ANOVAs were performed, with pressure designated as the independent variable. Tukey-Kramer or Dunnett's post hoc test was then used to test for significant within-group variation. For comparisons between control and SP data sets, matched-pairs tests were used. Significance was defined as P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Myogenic constriction.

Under in vitro conditions, the responses of mesenteric lymphatics to small positive pressure steps (≤3 cmH2O) were associated with increases in EDD that were suggestive of passive diameter responses. However, in all cases, the change in EDD was less than the change in response to an identical pressure step in Ca2+-free APSS (Fig. 1A). In this regard, the lymphatic response to pressure elevation resembled that of some arteries (37) and veins (35) in what has been characterized as a “nonpassive” or “slight” myogenic response (13).

Fig. 1.

A: time course of lymphatic diameter response to an abrupt increase in pressure [+2 cmH2O (left) and +6 cmH2O (right)]. Passive diameter changes for the same pressure steps (recorded in Ca2+-free bath at the end of the experiment) are overlaid and shown as maximal passive diameter (MaxD). EDD and ESD, end-diastolic and end-systolic diameter. Myogenic constriction is a time-dependent decline in EDD at constant pressure; a compensatory increase in AMP occurs when ESD decreases more than EDD over time. B: plot of normalized change in EDD for the first 25 contractions following positive pressure steps of +2, +4, +6, +8, +10, and +12 cmH2O. Baseline pressure was 1 cmH2O. Contraction frequency (FREQ) is higher with higher pressure (as in A), so time to complete 25 contractions is less with larger pressure steps. Error bars, SE.

When larger pressure steps were imposed, the typical lymphatic response was an initial passive distension followed by a progressive decline in EDD over a time course of 1–3 min (Fig. 1A). Because overt constrictions to pressure elevation such as this more closely resembled the responses of small arteries and arterioles (8), we termed this behavior “lymphatic myogenic constriction.” In contrast to highly responsive arterioles (8, 38), however, we seldom observed lymphatic myogenic constriction to a diameter that was less than the initial diameter (i.e., less than EDD at the lower pressure). Myogenic constrictions may not have been reported previously for lymphatic vessels, because their observation (based on our experience) required very clean and rapid pressure steps, which were not practical without the use of a servo system. Here, sustained myogenic constrictions were observed in 17 of 23 (74%) rat mesenteric lymphatic vessels (based on control vessels pooled from all protocols at 1 cmH2O baseline pressure). However, subsequent analyses included all vessels whether or not they exhibited myogenic constriction, as long as the vessels met the other criteria for viability.

To quantify myogenic constriction, EDD, ESD, and AMP were measured for each spontaneous contraction following a positive pressure step. In preliminary studies, we found that myogenic constrictions were typically complete (i.e., with no further constriction) within 1–2 min (requiring 15–20 contractions) and were maintained for ≥4 min. In some vessels, we monitored the sustained constriction for longer durations, but long-duration monitoring at every pressure step would have lengthened the protocols, such that vessel function would have been compromised in many cases. The standard protocol was to measure EDD and ESD for ∼25 contractions (2–4 min) after a positive pressure step and for ∼10 contractions after a negative pressure step. The normalized change in EDD is plotted against the contraction number for pressure steps of different sizes in Fig. 1B. In the first series of protocols, all vessels were equilibrated at a baseline pressure of 1 cmH2O before pressure was stepped by +2, +4, +6, +8, +10, or +12 cmH2O, with return to 1 cmH2O after each step. The first step of +2 cmH2O was not associated with a myogenic constriction but, rather, with a progressive increase in normalized EDD over time. A pressure step of +4 cmH2O produced only a slight, transient myogenic constriction over the first few contractions. However, pressure steps between +6 and +12 cmH2O consistently produced myogenic constrictions (negative values of the normalized change in EDD), with a progressively greater effect at higher pressure steps. The response began to diminish in magnitude with pressure steps larger than +14 cmH2O (not shown), but steps larger than +12 cmH2O were not routinely performed to avoid possible damage to the vessel.

Two other effects of pressure are evident from the data in Fig. 1B. 1) The rate of myogenic constriction was enhanced with increasing size of the pressure step. The slopes of the lines fitting the data progressively decreased from +0.39 (+2 cmH2O) to −1.75 (+12 cmH2O; in units of normalized change in EDD per minute), indicating a higher rate of constriction with larger pressure steps. 2) There was a progressive increase in FREQ with larger pressure steps (i.e., higher final pressures), as would be expected from previous studies (22, 49). Since only the data for the first 25 contractions were plotted for each pressure step, a higher FREQ dictated that the contractions were completed in a shorter time. Thus the FREQ for the +12-cmH2O data set was nearly three times higher than that for the +2-cmH2O data set. The FREQ response to pressure was further confirmation that this set of vessels was responding normally.

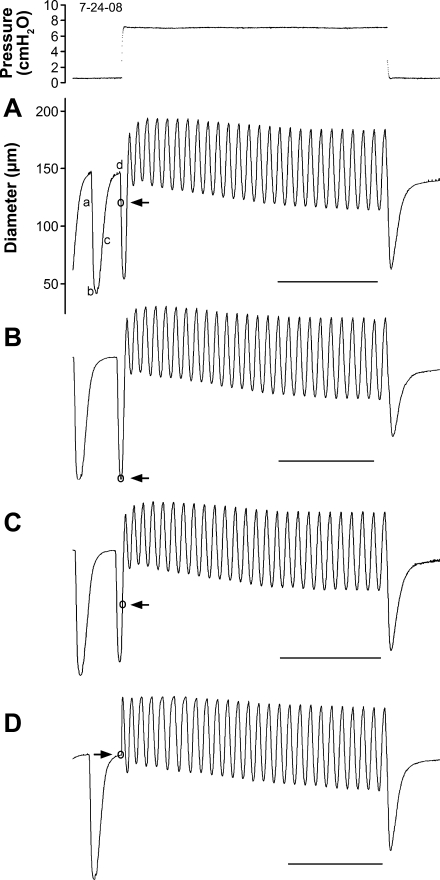

In the protocols described above, an increasing pressure step was always timed to coincide with the diastolic phase of a spontaneous contraction, whereas pressure reduction was timed to coincide with systole. However, it is possible that the level of activation of the vessel at different points within a contraction cycle might have influenced the magnitude of the subsequent reaction to a rapid pressure step. We tested this possibility using the protocol illustrated in Fig. 2. For several vessels showing myogenic constrictions, pressure steps of identical magnitude were imposed, with each step initiated early in systole (a), at peak systole (b), in early diastole (c), or in late diastole (d). A representative set of traces for one vessel is shown in Fig. 2, with the timing of the pressure rise indicated by arrows. There was very little difference in the magnitude of the change in EDD (maximum to minimum) between the traces, except for the AMP of the first three contractions. Thus it appeared that the timing of the pressure step did not significantly affect the magnitude of the myogenic constriction. In subsequent experiments, pressure steps were always initiated in late diastole.

Fig. 2.

Protocol to test how timing of a pressure step might influence magnitude and/or time course of a change in EDD. Pressure step was initiated at 1 of 4 points within the lymphatic contraction cycle (○ in each diameter trace) and corresponds to a–d. Pressure trace at top is associated with diameter recording in A (subsequent pressure steps are not shown but were essentially identical in magnitude and length). All diameter scaling is the same as in A. Time scales of B–D were adjusted slightly to align traces, and calibration bars indicate true scaling, 30 s. Actual sequence in which traces were collected was as follows: D, B, A, and C.

Compensatory AMP increase following pressure elevation.

The first contraction after a positive pressure step was triggered by the increased distension/filling associated with the pressure change and, thus, was not a true isobaric contraction. Compared with the respective values at the baseline pressure, there was an initial increase in ESD, an increase in EDD, and a decrease in AMP after the pressure step. Subsequently, a progressive decline in EDD and ESD occurred, with the decline in ESD being greater, such that AMP progressively increased over time at constant pressure. EDD, ESD, and AMP stabilized after 25–30 contractions. A similar compensatory effect for AMP has been described previously in other lymphatic vessels (4, 10, 36), although the time course over which it occurs has not been documented. The phenomenon appears to represent an intrinsic compensation of the lymphatic pump to pressure elevation, perhaps analogous to heterometric regulation of cardiac muscle (47).

A compensatory increase in AMP was observed after positive pressure steps in nearly every vessel in response to most pressure steps between +2 and +12 cmH2O. It occurred even after pressure steps from 0.5 to 3 cmH2O or from 1 to 3 cmH2O, in which myogenic constrictions were seldom observed (e.g., Fig. 1A, left; Fig. 1B, open circles). The observation that this response was more consistent and robust than myogenic constriction prompted a comparison of its magnitude in vessels that did show myogenic constriction with that in vessels that did not show myogenic constriction. Figure 3 plots the time course of AMP (normalized to MaxD) as a function of time after a pressure step, with the data separated according to whether the vessel showed myogenic constriction to one or more pressure steps (Fig. 3A) or failed to show myogenic constrictions (Fig. 3B). Upon analysis, there were only slight differences between any of the respective pairs of curves for the two groups of vessels (e.g., comparison of the two curves at +4 cmH2O), although FREQ increased less in response to some of the higher pressure steps in the nonmyogenic vessels. These findings indicate that mesenteric lymphatics exhibited compensatory increases in AMP whether or not they showed myogenic constrictions and suggest that the two phenomena may be mechanistically distinct.

Fig. 3.

Plots of normalized AMP as a function of time after rapid pressure elevation. Vessels were divided into 2 groups for separate analysis: vessels that showed myogenic constriction to at least 1 pressure step in the range +2 to +12 cmH2O (A) and vessels that showed no myogenic constrictions to any pressure step over the same range (B). Scales are the same for A and B. Baseline pressure = 1 cmH2O for all vessels. Error bars, SE. Error bars on time axis are not shown for clarity.

Pressure range for myogenic constriction.

Next, we tested whether the magnitude of myogenic constriction was altered by the baseline pressure from which positive pressure steps were imposed. Vessels were equilibrated at one of the four baseline pressures (see methods) from which the standard set of positive pressure steps was imposed. The lowest practical baseline pressure was 0.5 cmH2O because of the very low FREQ of many vessels at this pressure (some contracted only once every 10 min in the absence of SP). Figure 4 summarizes the data for this protocol. In Fig. 4A, the average steady-state change in normalized EDD for each pressure step is plotted against the test pressure. The four sets of curves represent the data sets for the four different baseline pressures, with negative values indicating myogenic constrictions at the respective pressures. A more negative slope reflects a higher myogenic gain, following the convention used to analyze myogenic responses in arterioles (8, 43). Clearly, the magnitude of myogenic constriction and the sensitivity to pressure were greatest at the lower pressures, in particular at 0.5 cmH2O. In Fig. 4B, the change in diameter for the same vessels and pressure steps is plotted as a function of the test pressure to indicate the magnitude of the initial stretch associated with the pressure change. Interestingly, myogenic reactivity was not always proportional to the increase in initial stretch. For example, vessels equilibrated at 0.5 cmH2O were nearly twofold more reactive to pressure steps than those equilibrated at 1 cmH2O; however, the responses at the lower baseline pressure were associated with only ∼25% more stretch.

Fig. 4.

A: magnitude of myogenic constriction expressed as normalized change in EDD as a function of pressure. After equilibration at baseline pressures (0.5, 1, 3, and 5 cmH2O), pressure was stepped by +2, +4, +6, +8, +10, and +12 cmH2O. Values of normalized EDD were then averaged over contractions 15–25 after the pressure step to estimate the steady-state constriction achieved. B: change in diameter plotted as a function of the final pressure for the same vessels and pressure steps in A. Error bars, SE. *Significant difference (P < 0.05, by ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc tests) between the indicated mean and the mean at the lowest test pressure for a given baseline pressure; for clarity, significant difference is shown only for 0.5 cmH2O baseline pressure data set, but the pattern of significant differences was the same for all other data sets.

Effect of SP.

SP is a neuropeptide associated with lymphoid tissue and inflammatory responses. Not surprisingly, SP-containing nerves are closely associated with lymphatic vessels in the gastrointestinal tract (27, 30), and SP has been shown to modulate lymphatic contractility (1, 14). Agonists such as norepinephrine and angiotensin II enhance basal myogenic tone in arterioles and enhance myogenic constriction to pressure elevation (13, 19, 41). For these reasons, we hypothesized that SP would enhance the myogenic constriction observed in lymphatic vessels.

The effects of a moderately low concentration of SP (3 × 10−8 M) on the lymphatic response to rapid pressure elevation were studied in 11 vessels. This concentration of SP produced a consistent increase in spontaneous FREQ and a slight increase in tone at every baseline pressure, with very little change in AMP (14). Representative examples of the effect of SP on the lymphatic response to rapid pressure steps from a baseline pressure of 3 cmH2O are shown in Fig. 5, A and B. Ten of 11 lymphatic vessels showed enhanced myogenic constriction in the presence of SP. The results for all 11 vessels are summarized in Fig. 5, C and D. The chronotropic effect of elevated pressure is apparent from the shorter times required to achieve a fixed number contractions with higher pressure steps; for example, after a pressure step of +2 cmH2O, ∼2.5 min were required to complete 25 contractions under control conditions, whereas only ∼1 min was required in the presence of SP. More importantly, SP enhanced the rate and magnitude of constriction after pressure elevation for all pressure steps, as denoted by more negative values of normalized EDD at each time point. In most cases, the magnitude of the constriction increased by more than threefold in the presence of SP. Correspondingly, the rate at which the constriction developed was also enhanced by SP. The slopes of the lines fitting the data sets in Fig. 5 ranged from +0.12 to −0.48 (change in normalized EDD/min) for the control data and from −2.89 to −3.75 for the SP data; i.e., constriction was 6- to 10-fold faster in the presence of SP.

Fig. 5.

Lymphatic response to pressure steps of +8 and +10 cmH2O before (A) and after (B) application of 3 × 10−8 M substance P (SP) to the bath (scales are the same for A and B). C and D: summary data for time course of the change in normalized EDD before (control) and after treatment with 3 × 10−8 M SP (paired measurements) at 3 cmH2O baseline pressure. For clarity, results of statistical tests are not shown, but each of the steady-state means (e.g., for contraction 25) was significantly different between control and SP data sets, except at +6 cmH2O (not significant). Error bars, SE. For clarity, error bars are shown only for the first and last points.

The effects of SP on the change in normalized EDD in response to the same set of pressure steps are shown in Fig. 6 for four different baseline pressures. For this analysis, the steady-state change in normalized EDD was measured as described above. Under control conditions (in the absence of SP), the normalized EDD increased for the first pressure step (+2 cmH2O) from a baseline of 0.5 cmH2O, but at all subsequent (higher) pressure steps, the vessels constricted (Fig. 6A, open circles). The same pattern was evident starting from a baseline pressure of 1 cmH2O (Fig. 6B, open circles), but the magnitude of the constriction was slightly less for each pressure step than at the lower baseline pressure. As baseline pressure was raised to 3 or 5 cmH2O, the degree of constriction in response to increasing pressure steps diminished (Fig. 6, C and D, open circles).

Fig. 6.

A–D: Plots of steady-state normalized change in EDD (averaged over contractions 15–25 after a pressure step) as a function of step pressure. Data represent paired data sets. Error bars, SE. *Significant difference (P < 0.05, by matched pairs test) between control and SP at the respective pressure.

At each of the four baseline pressures, SP (3 × 10−8 M) enhanced the magnitude of myogenic constriction. Moreover, this enhancement occurred for each pressure step, except the lowest one (+2 cmH2O) at the two lower baseline pressures. The effect of SP was clearest at baseline pressures of 3 and 5 cmH2O. SP also increased basal lymphatic tone at each level of pressure, regardless of the baseline pressure (not shown). Tone was 7–9% at all baseline pressures (0.5–5 cmH2O) in the absence of SP. In the presence of 3 × 10−8 M SP, tone significantly increased to 12–13% after all positive pressure steps, except after the lowest steps from baseline pressures of 0.5 and 1 cmH2O, where even higher levels of tone (17–18%) were recorded. This effect of SP at low pressures has been reported previously (14) and is not shown here, because the tone data sets at the four baseline pressure levels overlapped extensively and could not be easily distinguished on a single plot.

Myogenic dilation.

Arterioles that show myogenic constriction to pressure elevation typically show myogenic dilation to pressure reduction (8). In the course of the present study, we observed that many lymphatic vessels showed what appeared to be myogenic dilations in response to downward pressure steps. An example of this response is shown in Fig. 7. For comparison, Fig. 7A shows a vessel that did not exhibit myogenic dilation, because diameter slowly declined with time after the downward pressure step (arrow) over a time course similar to the diameter change for the same vessel in the Ca2+-free bath (passive trace; superimposed on the active diameter trace). In contrast, the diameter of a myogenically dilating vessel in Fig. 7B slowly increased after each downward pressure step (arrows); this pattern was the opposite of the passive behavior of the same vessel in response to the same pressure steps (recorded at the end of the experiment). We refer to this response as “myogenic dilation.” In addition, the magnitude of the myogenic dilation appeared to be increased with larger pressure steps, as did the time required for complete dilation (Fig. 7B). This vessel also showed myogenic constriction in response to each of the upward pressure steps, and the magnitude of the constriction progressively increased with the size of the pressure step. Another vessel showing myogenic dilation is represented in Fig. 5, A and B, whereas a vessel not exhibiting myogenic dilation is represented in Fig. 1A. There was an interesting correlation between myogenic dilation and constriction: for vessels starting from a baseline pressure of 1 cmH2O, 13 of 23 (56%) vessels dilated after negative pressure steps. All 13 vessels also showed myogenic constriction. Of the 10 vessels that did not show myogenic dilation, only 4 (40%) showed myogenic constriction. For vessels equilibrated at a baseline pressure of 3 cmH2O, only 1 of 10 showed myogenic dilation. Thus myogenic dilation was more prominent at lower pressures and in vessels showing myogenic constriction. Lymphatic myogenic dilation was difficult to analyze, because in most cases the dilation was complete before any spontaneous contractions occurred (Fig. 5A) due to a rate-sensitive mechanism that inhibited contraction for 1–2 min after a downward pressure step (10). There was also a trend for the magnitude of myogenic dilation to be enhanced by SP (cf. Fig. 5, A and B).

Fig. 7.

Myogenic dilation after rapid pressure reduction. A: lymphatic vessel that exhibited a slight myogenic constriction to a pressure step from 1 to 6 cmH2O but did not show myogenic dilation when pressure was returned to 1 cmH2O. Passive response of the same vessel to the same-size pressure step, obtained at the end of the experiment, is overlaid on the active diameter trace. Change in EDD after pressure was reduced followed a time course similar to the passive trace. B: lymphatic vessel that showed myogenic dilations to the falling phase of each of 3 pressure steps. Passive traces for the same-size pressure steps are overlaid and labeled. After pressure was reduced, EDD rose with time during the 1st min, in contrast to the shape of the passive traces. Dilation was exaggerated with greater pressure steps.

DISCUSSION

We describe, for the first time, myogenic constrictions and dilations of collecting lymphatic vessels. Although the term “lymphatic myogenic response” has been used previously to refer to various reactions of the lymphatic pump to hydrostatic forces (2, 42), in the context of our study, it was defined as a time-dependent decline in EDD following pressure elevation (myogenic constriction) or a time-dependent rise in EDD following pressure reduction (myogenic dilation). Myogenic responses were observed in a large majority of rat mesenteric lymphatic vessels in vitro and occurred over a surprisingly wide range of pressures. Myogenic constrictions were distinct from at least one cardiac-like aspect of lymphatic pump behavior, namely, the time-dependent compensatory decline in ESD and increase in AMP that were also observed after pressure elevation. The inflammatory mediator SP, which is known to enhance lymphatic contractility, increased 1) the percentage of vessels exhibiting myogenic constriction, 2) the magnitude of myogenic constriction, 3) the rate of constriction, and 4) the pressure range over which constriction occurred. Our results demonstrate that myogenic responses occur in collecting lymphatic vessels and suggest that the response may aid in preventing vessel overdistension when lymph pressure is elevated, such as during inflammation and edema.

Comparison to myogenic responses of blood vessels.

Under control conditions, i.e., in the absence of any exogenous activators of lymphatic muscle, lymphatic vessels showed the strongest myogenic responses to pressure steps starting from baseline pressures of 0.5–1 cmH2O, a pressure range that coincides with higher levels of basal tone, as described previously (22, 23). Indeed, this pressure range may be close to the in vivo hydrostatic pressure under conditions of normal tissue hydration, based on the few published measurements of lymphatic pressure in the intact rat mesenteric microcirculation. For example, Hargens and Zweifach (28) recorded lymphatic FREQ of 7 min−1 at 3 cmH2O average end-diastolic pressure, and Granger et al. (26) recorded FREQ of 5 min−1 at 2 cmH2O end-diastolic pressure. However, these in vivo measurements likely represent the high end of the lymphatic pressure range under conditions of normal tissue hydration, because they were, by necessity, made in superfused preparations in which the tissue was likely to be slightly hydrated, thus elevating lymphatic pressures and flow rates. Therefore, in vivo diastolic pressures in rat mesenteric lymphatics are probably often <2 cmH2O, in a range where they would exhibit myogenic responses to transmural pressure increases.

How do lymphatic myogenic responses compare with those of arterioles and small arteries? Lymphatic vessels, similar to arterioles, show a lower and an upper limit to myogenic constriction. Lymphatic constrictions waned above pressures of ∼15 cmH2O and did not occur in response to the smallest pressure step (+2 cmH2O), as consistently shown in Figs. 1B, 3, and 5A; similarly, even highly reactive arterioles do not show myogenic constrictions below a minimum pressure [e.g., <40 cmH2O for hamster cheek pouch 2nd-order arterioles (8)]. To make more quantitative comparisons between lymphatic and arteriolar myogenic responses, we calculated the myogenic index according to the formula described in previous publications (8). The myogenic index represents the relative change in vessel diameter per unit change in pressure (traditionally in mmHg). The strongest myogenic constriction of lymphatic vessels occurred (under control conditions) with a pressure step from 0.5 to 10.5 cmH2O, corresponding to a steady-state change in normalized EDD of approximately −3 (Fig. 6A). We used the absolute lymphatic diameters (initial and final) for the 10 vessels in that protocol to calculate a myogenic index of −0.51 (in mmHg). Of those 10 vessels, 6 constricted, 2 dilated, and 2 showed <1-μm change in diameter upon pressure elevation (after initial distention). The myogenic index for the six vessels that constricted was −0.75. Surprisingly, the values are quite comparable to those of first-, second-, and third-order arterioles from hamster cheek pouch (range −0.41 to −0.85) and other tissues (8).

The mechanisms by which an increase in circumferential length evokes myogenic constriction in vascular smooth muscle are not fully understood, but it seems clear that muscle cell length per se cannot be the controlled variable (32). Burrows and Johnson (5, 6) demonstrated that wall tension correlates well with the responses of small arterioles to pressure elevation, where the vessels often constrict well below their initial diameters. The same principles presumably apply to lymphatic muscle, even though the compliance of lymphatic vessels is remarkably different from that of arterioles (48). In lymphatics, myogenic constrictions were strongest in response to pressure elevation from the lowest baseline pressure, from which pressure steps produced the largest amount of distension (Fig. 4). However, myogenic constrictions were not proportional to the degree of distension, nor were large distensions always required; for example, in the presence of SP, vessels showed larger myogenic constrictions starting from higher baseline pressures (Fig. 6, C and D), from which further pressure elevation evoked very little further distension (Fig. 4B).

Relationship of myogenic responses to lymphatic pump function.

Lymphatic myogenic constrictions were not necessarily associated with, nor were they correlated to, time-dependent decreases in ESD after pressure elevation (Fig. 3). The examples shown here (Figs. 1A, 2, 5A, 5B, and 7) appear to be the first published descriptions of the time course of both phenomena in lymphatic vessels, even though steady-state AMP compensation has been documented previously (18, 21, 22, 40). The partial recovery (i.e., decline) of lymphatic vessel ESD (following its initial increase after a pressure step) presumably reflects underlying mechanisms that are analogous to heterometric regulation in the heart (34). In the isolated heart, an increase in preload produces an immediate increase in end-diastolic volume (i.e., EDD), with subsequent maintenance of end-systolic volume (ESD) if afterload is kept constant; thus cardiac stroke volume (AMP) increases in proportion to preload over a relatively wide preload range. If afterload is increased in the isolated heart (at constant preload), end-systolic volume increases and stroke volume is reduced (11, 47). A subsequent reduction in end-systolic volume does not occur unless there is an increase in contractility. However, in our protocols, preload and afterload were elevated simultaneously by increase of the pressure in both cannulating pipettes, so that further studies are required to distinguish their independent effects. Thus it is not clear whether an increase in lymphatic muscle contractility is associated with the subsequent decline in ESD after pressure elevation. However, given that myogenic constrictions in arterioles are associated with an increase in contractility of vascular smooth muscle (9, 32), the decline in lymphatic ESD probably does not reflect an increase in lymphatic muscle contractility, because we observed equivalent compensatory changes in ESD and AMP in vessels that showed myogenic constrictions and in vessels that did not show myogenic constrictions (Fig. 3), i.e., in vessels presumably exhibiting different levels of contractility.

Lymphatic myogenic responses are enhanced by SP.

Multiple aspects of lymphatic myogenic constriction were enhanced by the inflammatory mediator SP: 1) the percentage of vessels in which it was observed, 2) its magnitude, 3) its rate, and 4) the pressure range over which it occurred. Recently, we demonstrated that SP induces positive inotropic and chronotropic responses in isolated rat mesenteric lymphatics. In addition, SP enhanced basal lymphatic tone, i.e., reduced EDD at constant pressure, in a dose-dependent manner (14). The latter effect is particularly interesting, because the development of basal tone is one characteristic shared by lymphatics and arteriolar blood vessels (21, 22), as opposed to lymphatic pump behavior, which is more cardiac-like (4, 26, 36). Since basal tone and myogenic responses have been shown to be closely related (but perhaps distinct) in blood vessels (13), it is not surprising that lymphatic vessels are able to demonstrate myogenic responses under the appropriate conditions and that those responses are enhanced by an agonist that also enhances basal tone. In addition, myogenic constriction has been shown to be associated with an increase in the activation state of smooth muscle (9, 31), so that agonists that enhance contractility might be expected to enhance myogenic responsiveness.

The effect of SP on the enhancement of lymphatic myogenic constriction was greatest at higher pressures (Fig. 6), extending the range over which myogenic constrictions occurred. One possible conclusion from this observation is that SP, and perhaps other inflammatory mediators that are known to modulate the lymphatic pump in vivo (1, 16), activate collecting lymphatics to enable them to resist distension at the higher intraluminal pressures that are encountered during inflammation/edema. Our studies have revealed this previously undescribed and possibly underappreciated mechanism that contributes to fluid homeostasis.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL-089784.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank David Durtschi and Shan Yu Ho for technical assistance and Dr. David C. Zawieja for many helpful suggestions and ideas.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amerini S, Ziche M, Greiner ST, Zawieja DC. Effects of substance P on mesenteric lymphatic contractility in the rat. Lymphat Res Biol 2: 2–10, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atchison DJ, Johnston MG. Role of extra- and intracellular Ca2+ in the lymphatic myogenic response. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 272: R326–R333, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bayliss WM On the local reactions of the arterial wall to changes of internal pressure. J Physiol 28: 220–231, 1902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benoit JN, Zawieja DC, Goodman AH, Granger HJ. Characterization of intact mesenteric lymphatic pump and its responsiveness to acute edemagenic stress. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 257: H2059–H2069, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burrows ME, Johnson PC. Arteriolar responses to elevation of venous and arterial pressures in cat mesentery. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 245: H796–H807, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burrows ME, Johnson PC. Diameter, wall tension, and flow in mesenteric arterioles during autoregulation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 241: H829–H837, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis MJ An improved, computer-based method to automatically track internal and external diameter of isolated microvessels. Microcirculation 12: 361–372, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis MJ Myogenic response gradient in an arteriolar network. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 264: H2168–H2179, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis MJ, Davidson J. Force-velocity relationship of myogenically active arterioles. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 282: H165–H174, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis MJ, Davis AM, Lane MM, Zawieja DC, Gashev AA. Rate-sensitive contractile responses of lymphatic vessels to circumferential stretch. J Physiol. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Davis MJ, Gore RW. Determinants of cardiac function: simulation of a dynamic cardiac pump for physiology instruction. Am J Physiol 25: 13–25, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis MJ, Hill MA. Signaling mechanisms underlying the vascular myogenic response. Physiol Rev 79: 387–423, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis MJ, Hill MA, Kuo L. Local regulation of microvascular perfusion. In: Handbook of Physiology: Microcirculation (2nd ed.), edited by Tuma R, Duran W, Ley K. New York: Elsevier, 2008, p. 1–127.

- 14.Davis MJ, Lane MM, Davis AM, Durtschi D, Zawieja DC, Muthuchamy M, Gashev AA. Modulation of lymphatic muscle contractility by the neuropeptide substance P. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 295: H587–H597, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis MJ, Lane MM, Scallan JP, Gashev AA, Zawieja DC. An automated method to control preload by compensation for stress relaxation in spontaneously contracting, isometric rat mesenteric lymphatics. Microcirculation 14: 603–612, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dobbins DE Neuropeptide modulation of lymphatic smooth muscle tone in the canine forelimb. Mediators Inflamm 1: 241–246, 1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duling BR, Gore RW, Dacey RG Jr, Damon DN. Methods for isolation, cannulation, and in vitro study of single microvessels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 241: H108–H116, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eisenhoffer J, Elias RM, Johnston MG. Effect of outflow pressure on lymphatic pumping in vitro. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 265: R97–R102, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Faber JE, Meininger GA. Selective interaction of α-adrenoceptors with myogenic regulation of microvascular smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 259: H1126–H1133, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gashev AA Lymphatic vessels: pressure- and flow-dependent regulatory mechanisms. Ann NY Acad Sci 1131: 100–109, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gashev AA [The pump function of the lymphangion and the effect on it of different hydrostatic conditions]. Ross Fiziol Zh Im I M Sechenova 75: 1737–1743, 1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gashev AA, Davis MJ, Delp MD, Zawieja DC. Regional variations of contractile activity in isolated rat lymphatics. Microcirculation 11: 477–492, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gashev AA, Davis MJ, Zawieja DC. Inhibition of the active lymph pump by flow in rat mesenteric lymphatics and thoracic duct. J Physiol 450: 1023–1037, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gashev AA, Orlov RS, Zawieja DC. [Contractions of the lymphangion under low filling conditions and the absence of stretching stimuli. The possibility of the sucking effect]. Ross Fiziol Zh Im I M Sechenova 87: 97–109, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gasheva OY, Zawieja DC, Gashev AA. Contraction-initiated NO-dependent lymphatic relaxation: a self-regulatory mechanism in rat thoracic duct. J Physiol 575: 821–832, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Granger HJ, Kovalcheck S, Zweifach BW, Barnes GE. Quantitative analysis of lymph formation and propulsion. Proc Summer Computer Simulation Conf, La Jolla, CA, 1977, p. 562–569.

- 27.Guarna M, Pucci AM, Alessandrini C, Volpi N, Fruschelli M, D'Antona D, Fruschelli C. Peptidergic innervation of mesenteric lymphatics in guinea pigs: an immunocytochemical and pharmacological study. Lymphology 24: 161–167, 1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hargens AR, Zweifach BW. Contractile stimuli in collecting lymph vessels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 233: H57–H65, 1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hargens AR, Zweifach BW. Transport between blood and peripheral lymph in intestine. Microvasc Res 11: 89–101, 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hukkanen M, Konttinen YT, Terenghi G, Polak JM. Peptide-containing innervation of rat femoral lymphatic vessels. Microvasc Res 43: 7–19, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson PC Autoregulatory responses of cat mesenteric arterioles measured in vivo. Circ Res 22: 199–212, 1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson PC The myogenic response. In: Handbook of Physiology The Cardiovascular System. Vascular Smooth Muscle. Bethesda, MD: Am. Physiol. Soc., 1980, sect. 2, vol. II, p. 409–442. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koller A, Mizuno R, Kaley G. Flow reduces the amplitude and increases the frequency of lymphatic vasomotion: role of endothelial prostanoids. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 277: R1683–R1689, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Konhilas JP, Irving TC, de Tombe PP. Frank-Starling law of the heart and the cellular mechanisms of length-dependent activation. Pflügers Arch 445: 305–310, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuo L, Arko F, Chilian WM, Davis MJ. Coronary venular responses to flow and pressure. Circ Res 72: 607–615, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li B, Silver I, Szalai JP, Johnston MG. Pressure-volume relationships in sheep mesenteric lymphatic vessels in situ: response to hypovolemia. Microvasc Res 56: 127–138, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu Y, Harder DR, Lombard JH. Myogenic activation of canine small renal arteries after nonchemical removal of the endothelium. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 267: H302–H307, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Loutzenhiser R, Bidani A, Chilton L. Renal myogenic response: kinetic attributes and physiological role. Circ Res 90: 1316–1324, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McGeown JG, McHale NG, Roddie IC, Thornbury K. Peripheral lymphatic responses to outflow pressure in anaesthetized sheep. J Physiol 383: 527–536, 1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McHale NG, Roddie IC. The effect of transmural pressure on pumping activity in isolated bovine lymphatic vessels. J Physiol 261: 255–269, 1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meininger GA, Faber JE. Adrenergic facilitation of myogenic response in skeletal muscle arterioles. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 260: H1424–H1432, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mizuno R, Dornyei G, Koller A, Kaley G. Myogenic responses of isolated lymphatics: modulation by endothelium. Microcirculation 4: 413–420, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Osol G, Halpern W. Myogenic properties of cerebral blood vessels from normotensive and hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 249: H914–H921, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Quick CM, Venugopal AM, Gashev AA, Zawieja DC, Stewart RH. Intrinsic pump-conduit behavior of lymphangions. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 292: R1510–R1518, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schmid-Schönbein GW Microlymphatics and lymph flow. Physiol Rev 70: 987–1028, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schmid-Schönbein GW, Zweifach BW. Fluid pump mechanisms in initial lymphatics. News Physiol Sci 9: 67–71, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 47.West JB Best and Taylor's Physiological Basis of Medical Practice. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins, 1991.

- 48.Zhang RZ, Gashev AA, Zawieja DC, Davis MJ. Length-tension relationships of small arteries, veins and lymphatics from the rat mesenteric microcirculation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H1943–H1952, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang RZ, Gashev AA, Zawieja DC, Lane MM, Davis MJ. Length-dependence of lymphatic phasic contractile activity under isometric and isobaric conditions. Microcirculation 14: 613–625, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zweifach BW, Lipowsky HH. Pressure-flow relations in blood and lymph microcirculation. In: Handbook of Physiology. The Cardiovascular System. Microcirculation. Bethesda, MD: Am. Physiol. Soc., 1984, sect. 2, vol. IV, p. 251–307. [Google Scholar]