Puberty and Menarche

Conventional textbook teachings regarding menstruation in adolescents need to be examined in light of evidence regarding what is “normal.” Traditionally, precocious puberty has been defined as any pubertal development occurring before age 8. A large observational cross-sectional study of girls presenting to pediatricians for routine medical care (n = 17,077) evaluated breast and pubic hair development.[1] This study was among the first to suggest that pubertal development appears to be starting earlier than had previously been noted. This study found that nearly half of African American girls had pubertal development before age 8; it is unlikely that all of these girls had significant pathology. Based on this study, it was suggested that new norms for “precocious” puberty be established, with the proposal that it be defined as pubertal development before age 7 in whites and age 6 in African Americans.[2] However, this is still considered controversial, and it should be noted that pathologic causes of precious puberty can still occur in 6- to 7-year-olds; the younger the signs of puberty occur, the more likely a pathologic cause will be found.[3] Regardless, many scholars feel that these new guidelines present a practical, evidence-based approach.[4]

Emerging information about menarche – onset of the first menstrual period – from this study and others shows that there are differences between populations, with African American girls in the United States experiencing earlier puberty than Mexican American or white girls.[1,5–8] While the age of menarche has been declining from the early 1800s until the 1950s, more recently the decline seems to have slowed or stabilized and has only declined slightly since that time.[5–13] It has been suggested that the trends toward earlier puberty and menarche are caused by increases in overweight and obesity as reflected by body mass index.[7,8,12,14,15] It has also been suggested that decreases in age at menarche until the mid-1960s resulted from “positive” changes, such as better nutrition, whereas decreases since that time are related to “negative” changes, such as overeating, decreased physical activity, and possibly even chemical pollution.[12] In terms of the significance of earlier pubertal development, breast development before adrenarche (as manifested by pubic hair growth) as a pathway to puberty is associated with a greater proportion of body fat and greater waist circumference and waist/hip ratio; there is also a theorized or possible association with an increased risk for breast cancer or cardiovascular risks later in life.[16]

Delayed pubertal development with the absence of breast development by age 13 is strongly associated with impaired reproductive potential and should prompt an assessment to rule out ovarian failure with abnormal karyotype or other potentially irreversible problems.[17,18] The absence of menstruation by age 15 is also statistically quite uncommon (< 95th to the 98th percentile) and merits investigation.[1,11,19–21] This recommendation contrasts to the traditional guideline, which defined primary amenorrhea as lack of menstruation by age 16.

Menstrual Frequency and Cyclicity

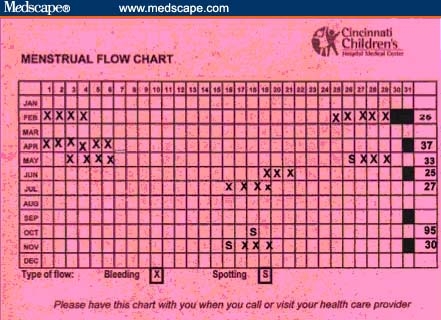

Adolescents should be encouraged to prospectively chart their menstrual bleeding from the time of menarche. A menstrual calendar is illustrated in Figures 1 and 2. While menstrual cycles tend to vary among adolescents, the length of a normal cycle ranges between approximately 20 to 45 days, with a mean cycle length of 32.2 days in the first and second gynecologic years.[22–24] These data contrast to the traditional dictum that any degree of irregularity is acceptable in young teens because many if not most are anovulatory. The range for menstrual cycles in adolescents is wider than in adults, in whom normal cycle length is defined as being between 21 and 34 days.[25] It is important to ascertain what an adolescent means when she complains of “irregular periods.” She may mean that her cycles are not always exactly 28 days; that the period does not always come on the same day of the week or date of the month; that the number of bleeding days varies from month to month; that she has “skipped a month” when her period begins at the end of one month and doesn't begin until the beginning of the subsequent month; or that she has had “two periods a month” if the period begins at the beginning of the month and the next period begins at the end of the month. A review of these complaints is facilitated by a graphic representation; in Figure 3, the menstrual cycles from January through July are within normal limits.

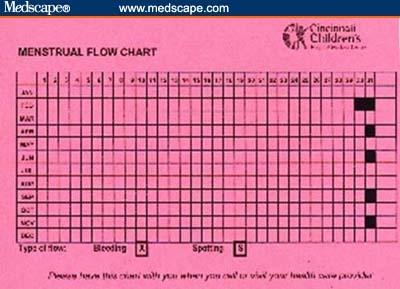

Figure 1.

Sample Menstrual Flow Calendar for tracking menstrual timing, flow, and duration.

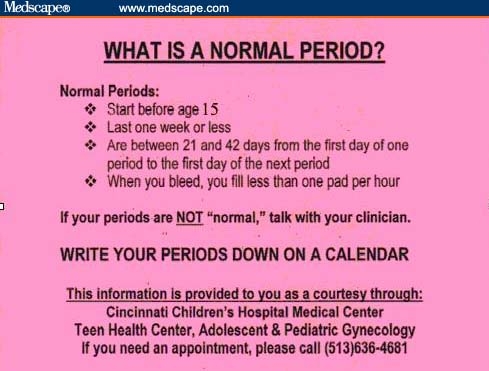

Figure 2.

Menstrual informational card for teens.

Figure 3.

Menstrual Flow Calendar with sample documentation.

Adolescents with cycles that are consistently outside of the range of 20 to 45 days should be evaluated for pathologic conditions, such as the polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), eating disorders, thyroid disease, hyperprolactinemia, or even such rare conditions as ovarian insufficiency (premature ovarian failure).[19] Table 1 lists causes of abnormal menstrual bleeding that can occur in women of all ages; those that can occur in adolescents are highlighted. The medical history and examination will render some of these conditions unlikely; however, others are more common and can be associated with health risks in adulthood, including risks for subsequent osteopenia or osteoporosis in girls with eating disorders or possible cardiovascular disease and diabetes in girls with PCOS.[26] The 95th percentile for menstrual cycle length is 90 days, even in the first gynecologic year.[22] Thus, secondary amenorrhea should be defined by this evidence-based criterion as 90 days, rather than the traditional 6 months (Figure 3).

Table 1.

Causes of Menstrual Irregularity/Abnormal Uterine Bleeding, Including Frequent Bleeding, Infrequent Bleeding, Intermenstrual Bleeding, or Postcoital Bleeding

| Anovulation |

| Polycystic ovarian syndrome |

| Stress – hypothalamic |

| Excessive exercise |

| Eating disorders |

| Anorexia nervosa |

| Bulimia |

| Hormonal conditions |

| Cushing's disease |

| Hyperprolactinemia |

| Thyroid disease |

| Chronic Illnesses |

| Diabetes mellitus, especially if poorly controlled |

| Inflammatory bowel disease |

| Kidney (renal) disease |

| Liver disease |

| Ovarian insufficiency – sometimes called ovarian failure, premature ovarian failure, or premature menopause |

| Pituitary conditions |

| Pituitary tumors (adenomas), such as prolactinoma |

| Cervical Conditions |

| Cervical cancer |

| Cervical infection (cervicitis) – may be caused by sexually transmitted diseases, including gonorrhea, Chlamydia, and Trichomonas |

| Cervical polyp |

| Endometrial Conditions |

| Endometrial cancer |

| Endometrial hyperplasia |

| Endometrial infection (endometritis) |

| Endometrial polyp |

| Endometriosis or adenomyosis |

| Hormonal Therapies |

| Breakthrough bleeding (unscheduled bleeding) |

| Birth control pills (oral contraceptives); most likely during the first few months of use; when taken late or missed; when used in smokers; with extended cycle regimens (84/7 trimonthly or 365-day regimen) |

| Birth control patch or ring; most likely during the first few months of use |

| Progestin-only birth control |

| Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depo-Provera®) |

| Progestin-only pills also called mini-pills – VERY unforgiving of missed pills |

| Progestin-containing intrauterine device–Mirena® |

| Hormone therapy for menopausal symptoms |

| Medical Illness |

| Adrenal disease |

| Adrenal hyperplasia |

| Cushing syndrome and disease |

| Clotting (coagulation) problems |

| Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura |

| Cancer, such as leukemia |

| Von Willebrand disease |

| Kidney (renal) disease |

| Liver disease |

| Pituitary disease |

| Thyroid disease |

| Medications/Drugs |

| Anticoagulants |

| Antipsychotic drugs |

| Progesterone |

| Tamoxifen |

| Complementary and Alternative Medicines (evidence may be sparse) |

| Chasteberry |

| Feverfew |

| Menopause (average age 51, defined as no bleeding for 1 year) |

| Ovarian Conditions |

| Ovarian cancers |

| Ovarian cysts |

| Ovarian tumors |

| Pregnancy |

| Conditions in Early Pregnancy |

| Miscarriage (medical term is spontaneous abortion) |

| Threatened |

| Incomplete |

| Complete |

| Tubal (ectopic pregnancy) |

| Molar pregnancy |

| Conditions in Late Pregnancy |

| Placental abruption |

| Placenta previa |

| Trauma |

| Foreign body in vagina |

| Retained tampon |

| Other objects |

| Sexual assault or abuse |

| Uterine Conditions |

| Pelvic inflammatory disease |

| Uterine fibroids (leiomyoma) |

| Vaginal Conditions |

| Vaginal infection (vaginitis) |

| Yeast infection (candidiasis) |

| Vaginal cancer |

| Vulvar Conditions |

| Lichen sclerosus |

| Rashes, other |

| Vulvar cancer |

| Sexually Transmitted Diseases |

| Chlamydia |

| Genital warts (condyloma), human papillomavirusGonorrhea |

| Trichomonas |

| Herpes simplex virus |

Heavy Menstrual Bleeding

Mothers of adolescents sometimes note that teens soil their underwear or clothing with menses; this may be evidence of heavy flow. While adolescents who have recently achieved menarche may have accidents while they are learning how to manage their periods and how frequently they need to change their sanitary protection, adolescents who are unable to go through the night without soiling bedding or who bleed so heavily that they require a change of protection more frequently than once an hour should be evaluated for causes of heavy bleeding.[27] While adults with heavy bleeding may have conditions ranging from uterine fibroids to endometrial polyps, hyperplasia, or even uterine or cervical malignancies, these conditions are rare in adolescents. One condition that deserves consideration in adolescents with excessively heavy bleeding or anemia is coagulopathies, such as von Willebrand disease, which occurs in as many as 1% of individuals.[28] Studies evaluating teens with heavy bleeding or hemorrhage have shown coagulopathies in up to 20%, with nearly half of those who present with heavy bleeding at the time of menarche having a coagulation defect.[29–32] Screening for these conditions should include coagulation tests, including a screen for von Willebrand disease; a complete blood count; and measurement of red cell indices, which can suggest iron deficiency anemia. Coagulation problems are typically associated with heavy but regular monthly bleeding. Most adolescents have bleeding lasting 3 to 7 days; bleeding for longer than 7 days is uncommon and merits evaluation.[19,33] An evaluation and diagnosis can minimize morbidities associated with these conditions, and management can vastly improve a young girl's quality of life.

Conditions associated with anovulation or oligo-ovulation can present with prolonged cycles followed by prolonged bleeding or, alternatively, with frequent bleeding. Adolescents who have hirsutism or moderate to severe acne as a sign of hyperandrogenism in addition to oligo-ovulation meet the diagnostic criteria for PCOS.[34] This syndrome is the most common condition presenting in this manner. It occurs in 5% to 7% of adult women and is probably the most common condition presenting with irregular bleeding, although diagnostic challenges complicate the assessment of the frequency of PCOS among adolescents. While irregular bleeding in the first few gynecologic years is frequently ascribed to immaturity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis, testing is warranted to rule out other causes of anovulation, including thyroid disease; conditions (including drug use) that are associated with hyperprolactinemia; or even ovarian insufficiency, also known as premature ovarian failure, which is characterized by cycles longer than the typical 45 days[19] (Table 1).

Summary

Clinicians need to be aware of evidence-based norms for pubertal development and menstrual function. Parameters for normal and abnormal menstrual bleeding in adolescents are listed in Table 2. Informing adolescents and their parents about these parameters and encouraging prospective charting of bleeding can help to determine whether the bleeding pattern is unusual enough to warrant diagnostic testing or therapy. Physicians and women should be encouraged to consider the menstrual cycle as a “vital sign.”[19,35] Just as abnormalities in pulse, respiration, or blood pressure can signal the need for medical evaluation, so too can menstrual abnormalities. It may be helpful to suggest to an adolescent that menstrual abnormalities in the absence of hormonal therapies should warrant attention: “Your body is telling you something.” Abnormal bleeding while on hormonal contraception has a very different pathophysiology from abnormal bleeding without hormonal contraception. Appropriate evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment have the potential to prevent future morbidities and to significantly improve an adolescent's quality of life.[36]

Table 2.

Quick Guide to Periods in Adolescents: What's Normal/What's Not

| Puberty |

| Too early (termed precocious puberty): Before age 6 in African Americans or before age 7 in whites |

| Too late (pubertal delay): No breast development by age 13 |

| Breast Development |

| Typically around age 11 |

| Too early: Before age 6 in African American or before age 7 in whites |

| Too late: If no breast development by age 13 |

| Menarche |

| Typically age 12–13; African American slightly earlier than whites |

| Too early: Before age 9 |

| Too late: No period by age 15 or by 2.5–3 years after the onset of breast development |

| Menstrual Cycle Length |

| Adolescents: 20–45 days |

| No periods for > 90 days (ie, amenorrhea) is abnormal in reproductive age women |

| Menstrual Flow Duration |

| Typical: 2–7 days |

| Menstrual Flow Volume |

| Typical: 35 mL (the textbook answer – of no practical worth) |

| Average tampon/pad use: Each pad or tampon lasts 3–4 hours |

| Excessive: ≥85 mL leads to anemia if ongoing |

| Soaking a pad or tampon in 1–2 hours for more than 2–4 hours is a practical definition, particularly if associated with feeling light-headed or dizzy |

Footnotes

Reader Comments on: Menstruation in Adolescents: What's Normal? See reader comments on this article and provide your own.

Readers are encouraged to respond to the author at paula.hillard@stanford.edu or to Peter Yellowlees, MD, Deputy Editor of The Medscape Journal of Medicine, for the editor's eyes only or for possible publication as an actual Letter in the Medscape Journal via email: peter.yellowlees@ucdmc.ucdavis.edu

References

- 1.Herman-Giddens ME, Slora EJ, Wasserman RC, et al. Secondary sexual characteristics and menses in young girls seen in office practice: a study from the Pediatric Research in Office Settings network. Pediatrics. 1997;99:505–512. doi: 10.1542/peds.99.4.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hammond R. Recurrent cervical smear abnormalities following treatment. Hosp Med (London) 1999;60:250–253. doi: 10.12968/hosp.1999.60.4.1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaplowitz P. Clinical characteristics of 104 children referred for evaluation of precocious puberty. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:3644–3650. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaplowitz P. Precocious puberty: update on secular trends, definitions, diagnosis, and treatment. Adv Pediatr. 2004;51:37–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freedman DS, Khan LK, Serdula MK, Dietz WH, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS. Relation of age at menarche to race, time period, and anthropometric dimensions: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Pediatrics. 2002;110:e43. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.4.e43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chumlea WC, Schubert CM, Roche AF, et al. Age at menarche and racial comparisons in US girls. Pediatrics. 2003;111:110–113. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson SE, Must A. interpreting the continued decline in the average age at menarche: results from two nationally representative surveys of U.S. girls studied 10 years apart. J Pediatr. 2005;147:753–760. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDowell MA, Brody DJ, Hughes JP. Has age at menarche changed? Results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2004. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40:227–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wyshak G, Frisch RE. Evidence for a secular trend in age of menarche. N Engl J Med. 1982;306:1033–1035. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198204293061707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Macmahon B. Age at menarche: United States, 1973. Series 11, no. 133. Rockville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 1974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zacharias L, Rand WM, Wurtman RJ. A prospective study of sexual development and growth in American girls: the statistics of menarchie. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1976;31:325–337. doi: 10.1097/00006254-197604000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herman-Giddens ME. The decline in the age of menarche in the United States: should we be concerned? J Adolesc Health. 2007;40:201–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Demerath EW, Towne B, Chumlea WC, et al. Recent decline in age at menarche: the Fels Longitudinal Study. Am J Hum Biol. 2004;16:453–457. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herman-Giddens ME, Kaplowitz PB, Wasserman R. Navigating the recent articles on girls' puberty in pediatrics: what do we know and where do we go from here? Pediatrics. 2004;113:911–917. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.4.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaplowitz PB, Slora EJ, Wasserman RC. Earlier onset of puberty in girls: relation to increased body mass index and race. Pediatrics. 2001;108:347–353. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.2.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Biro FM, Lucky AW, Simbartl LA, et al. Pubertal maturation in girls and the relationship to anthropometric changes: pathways through puberty. J Pediatr. 2003;142:643–646. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2003.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reindollar RH, Byrd JR, McDonough PG. Delayed sexual development: a study of 252 patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1981;140:371–380. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(81)90029-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Timmreck LS, Reindollar RH. Contemporary issues in primary amenorrhea. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2003:30287–302. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8545(03)00027-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.ACOG Committee Opinion No. 349, November 2006: Menstruation in girls and adolescents: using the menstrual cycle as a vital sign. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:1323–1328. doi: 10.1097/00006250-200611000-00059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harlan WR, Harlan EA, Grillo GP. Secondary sex characteristics of girls 12 to 17 years of age: the U.S. Health Examination Survey. J Pediatr. 1980:961074–1078. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(80)80647-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nelson L, Bakalov V. Amenorrhea. eMedicine. 2005.

- 22.Treloar AE, Boynton RE, Behn BG, Brown BW. Variation of the human menstrual cycle through reproductive life. Int J Fertil. 1967;12:77–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vollman R. The menstrual cycle. In: Friedman E, editor. Major Problems in Obstetrics and Gynecology. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Co; 1977. pp. 1–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flug D, Largo RH, Prader A. A longitudinal study of menstrual patterns in Swiss girls. Ann Hum Biol. 1984:495–508. doi: 10.1080/03014468400007411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fraser IS, Critchley HO, Munro MG, Broder M. Can we achieve international agreement on terminologies and definitions used to describe abnormalities of menstrual bleeding? Hum Reprod. 2007;22:635–643. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gordon CM, Nelson LM. Amenorrhea and bone health in adolescents and young women. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2003;15:377–384. doi: 10.1097/00001703-200310000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Warner PE, Critchley HO, Lumsden MA, et al. Menorrhagia I: measured blood loss, clinical features, and outcome in women with heavy periods: a survey with follow-up data. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:1216–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2003.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Phillips MD, Santhouse A. von Willebrand disease: recent advances in pathophysiology and treatment. Am J Med Sci. 1998;316:77–86. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199808000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Claessens E, Cowell CA. Acute adolescent menorrhagia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1981;139:277–280. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(81)90009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duflos-Cohade CM, Amandruz M, Thibaud E. Pubertal metrorrhagia. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 1996;9:16–20. doi: 10.1016/s1083-3188(96)70005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Edlund M, Blombäck M, von Schoultz B, Andersson O. On the value of menorrhagia as a predictor for coagulation disorders. Am J Hematol. 1996;53:234–238. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8652(199612)53:4<234::AID-AJH4>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bevan JA, Maloney KW, Hillery CA, Gill JC, Montgomery RR, Scott JP. Bleeding disorders: A common cause of menorrhagia in adolescents. J Pediatr. 2001;138:856–861. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.113042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flug D, Largo RH, Prader A. Menstrual patterns in adolescent Swiss girls: a longitudinal study. Ann Hum Biol. 1984;11:495–508. doi: 10.1080/03014468400007411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2004;81:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hillard PJA. Menstruation in adolescents: what's normal, what's not. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1135:29–35. doi: 10.1196/annals.1429.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kouides PA, Phatak PD, Burkart P, et al. Gynaecological and obstetrical morbidity in women with type I von Willebrand disease: results of a patient survey. Haemophilia. 2000;6:643–648. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2516.2000.00447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]