Abstract

Full-length 66-kDa estrogen receptor α (ERα) stimulates target gene transcription through two activation functions (AFs), AF-1 in the N-terminal domain and AF-2 in the ligand binding domain. Another physiologically expressed 46-kDa ERα isoform lacks the N-terminal A/B domains and is consequently devoid of AF-1. Previous studies in cultured endothelial cells showed that the N-terminal A/B domain might not be required for estradiol (E2)-elicited NO production. To evaluate the involvement of ERα AF-1 in the vasculoprotective actions of E2, we generated a targeted deletion of the ERα A/B domain in the mouse. In these ERαAF-10 mice, both basal endothelial NO production and reendothelialization process were increased by E2 administration to a similar extent than in control mice. Furthermore, exogenous E2 similarly decreased fatty streak deposits at the aortic root from both ovariectomized 18-week-old ERαAF-1+/+ LDLr−/− (low-density lipoprotein receptor) and ERαAF-10 LDLr −/− mice fed with a hypercholesterolemic diet. In addition, quantification of lesion size on en face preparations of the aortic tree of 8-month-old ovariectomized or intact female mice revealed that ERα AF-1 is dispensable for the atheroprotective action of endogenous estrogens. We conclude that ERα AF-1 is not required for three major vasculoprotective actions of E2, whereas it is necessary for the effects of E2 on its reproductive targets. Thus, selective ER modulators stimulating ERα with minimal activation of ERα AF-1 could retain beneficial vascular actions, while minimizing the sexual effects.

Keywords: atherosclerosis, reendothelialization, vasculoprotection

Epidemiological studies have suggested that both endogenous and exogenous estrogens protect women against cardiovascular diseases. Although the cardiovascular protective effect of conjugated equine estrogens was not confirmed in postmenopausal women enrolled in the Women Health Initiative (1), it is now widely accepted that the elevated mean age of the women (10–15 years postmenopause) largely contributed to the lack of prevention (2, 3). Thus, although the cardiovascular effects of estrogens are far more complex than initially assumed, it is clear that these hormones play important roles in vascular physiology and pathophysiology, with potential therapeutic implications. Indeed, various vasculoprotective actions of 17β-estradiol (E2), such as atheroprotection (4, 5), increase of NO production (6), prevention of endothelial activation (7) or apoptosis (8), and the acceleration of endothelial healing (9) have been extensively described.

The main action of E2 is mediated by 2 nuclear receptors, estrogen receptor (ER) α and ERβ, encoded by 2 distinct genes, Esr1 and Esr2, respectively. ERα, but not ERβ, is necessary and sufficient to mediate most of the vascular effects of E2, such as the increase in basal NO production (6) and the acceleration of reendothelialization (10). ERα can be divided into 6 domains from A to F that harbors 2 transactivation functions (AF-1 and AF-2) located within regions B and E, respectively (11, 12). In addition to the full-length 66-kDa (ERα66) isoform, a 46-kDa ERα-isoform (ERα46), lacking the N-terminal portion (domains A/B), and thereby AF-1, can be expressed through either an alternative splicing (13) or an internal entry site of translation (14). The relative contribution exerted by each isoform has been studied in vitro showing a selective permissiveness to either AF according to cellular type and context (12, 15).

ERα46 is expressed in human endothelial cells and is, as ERα66, able to stimulate acute NO production in endothelial cells in vitro (16, 17). Interestingly, previous studies have suggested that the ERα A/B domains might not be necessary for some vascular effects in response to estrogens in vivo. Indeed, the effect of E2 on endothelial NO production (18) and postinjury medial hyperplasia (19) was preserved in the first model of ERα gene disruption (αERKO), which consisted in the insertion of the neomycin-resistance gene in exon 1 (20). In contrast, both vascular effects of E2 were abolished in a more recently generated ERα knockout mouse model (ERα−/−) that fully and unambiguously lacks ERα (6, 21, 22). The persistence of both effects in αERKO mice was attributed to a non-natural mRNA alternative splicing, resulting in the expression of a truncated chimeric isoform deficient in ERα AF-1 box 2 and 3 (18, 23–25).

The aim of the present work was to directly evaluate the involvement of ERα AF-1 in NO production and two other vasculoprotective effects of E2, the reendothelialization process and the development of atherosclerosis. To this end, we developed a mouse model lacking the ERα A/B domains that we named ERαAF-10.

Results

Generation of ERαAF-10 Mice.

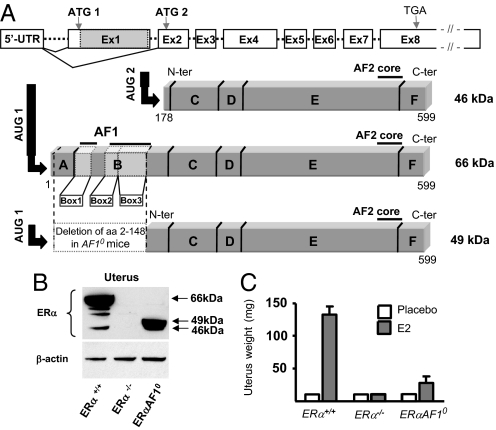

A mouse model used to study the role of ERα AF-1 was generated through a targeted deletion by using a knockin strategy, through which 441 nt of exon 1 were deleted. The truncated protein lacks the A domain and all three motifs constituting ERα AF-1 (AF-1 boxes 1–3) in the B domain, thus yielding a 451-aa-long, 49-kDa protein (Fig. 1A). As expected, both the 66- and 46-kDa ERα isoforms were detected in uteri from wild-type mice, whereas no immunoreactivity was observed in homogenates from ERα−/− mice (Fig. 1B). In uteri from ERαAF-10 mice, we detected the expression of a 49-kDa ERα corresponding to the expected domain A/B-truncated ERα protein and the physiological 46-kDa isoform. As for the 66-kDa natural isoform, the 49-kDa protein expression is initiated at the first ATG codon using the ERαAF-10 construct. Interestingly, the expression level of the 49-kDa isoform from ERαAF-10 mice was similar to that of the 66-kDa isoform in the wild-type mice.

Fig. 1.

Generation and validation of ERα AF-10 mice. (A) Schematic representation of the wild-type ERα gene (Esr1) and the targeted AF10 allele (the gray area in exon 1 shows the sequence deleted in ERαAF-10 mice corresponding to amino acids 2–148). The two physiologically-expressed ERα isoforms of 66-kDa (full length) and 46 kDa (AF-1 deficient) and the 49-kDa ERα protein expressed in ERα AF-10 mice are represented. (B) ERα protein level were assessed by Western blot analysis of 50 μg of protein from ERα+/+, ERα−/−, and ERα AF-10 mice uteri. (C) Uterine weight from ERα+/+, ERα−/−, and ERαAF-10− mice treated or not with E2 (80 μg/kg per day for 2 weeks).

As described (18, 21), E2 treatment elicited an important uterine hypertrophy in ERα+/+ mice, whereas no effect was observed in ERα−/− mice (Fig. 1C). In ERαAF-10 mice, only a modest increase in uterine weight was observed in response to E2, which demonstrates a crucial role of ERα AF-1 in uterus hyperplasia.

AF-1 Is Not Necessary for the Effect of E2 on Basal NO Production and Acceleration of Reendothelialization.

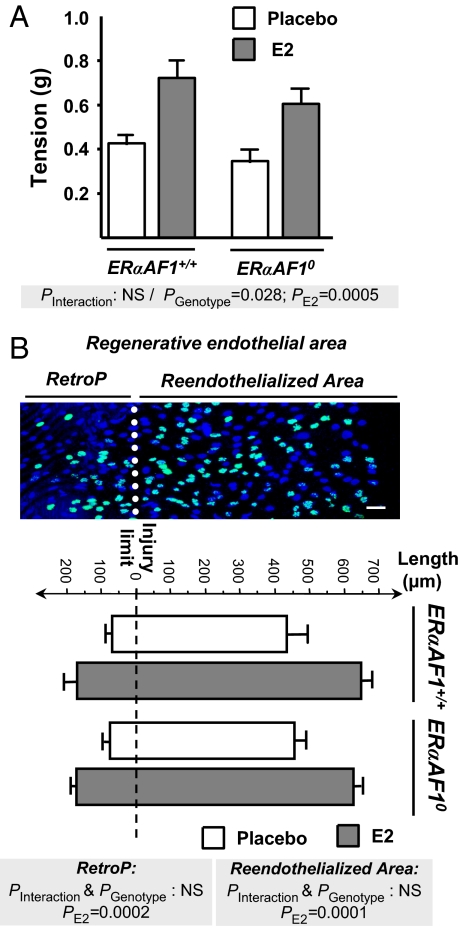

The production of NO was evaluated in isolated aortic rings. As reported in C57BL/6 mice (6), E2 did not significantly alter the contraction in response to 80 mM KCl or the α1-adrenergic agonist phenylephrine in ERαAF-1+/+ mice (data not shown). Similar results were observed in aortic rings from ERαAF-10 mice (data not shown). However, as shown in Fig. 2A, E2 significantly enhanced the basal NO release (evaluated by the NG-nitro-l-arginine-induced contraction obtained in U-46619 precontracted aortic rings) in both ERαAF-1+/+ and ERαAF-10 mice.

Fig. 2.

ERα AF-1 function is dispensable in the effect of E2 on basal NO production and endothelial healing. The effect of E2 was studied in ERα+/+ and ERα AF-10 ovariectomized mice. (A) The basal NO release of aortic rings from mice treated either with placebo (filled bars) or E2 (empty bars) was evaluated from the NG-nitro-l-arginine (100 μM)-induced contraction in rings precontracted with U-46619 (7.5 nM). Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA, and no significant interaction (P = 0.83) was observed. (B) (Upper) Representative en face confocal immunohistochemical analysis of the intima tunica from a E2-treated mouse, 72 h after surgery with designation of the reendothelialized area, retrograde proliferating zone (RetroP), and regenerative endothelial area. Nuclei, stained with propidium iodide, appear in dark blue, and proliferating BrdU-positive cells appear in light blue. (Scale bar: 50 μm.) (Lower) Quantification (mean ± SEM) of the length of the above-mentioned zones from an average of 4 mice per group. Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA, and no significant interaction was observed for RetroP length (P = 0.91) or reendothelialized area (P = 0.51).

We next compared endothelial healing in ERαAF-1+/+ versus ERαAF-10 mice in response to E2 treatment. As described (26, 27), the carotid electric injury model used for this study allows a precise definition of the injury limit and a measurement of the length of the reendothelialized area by using en face confocal microscopy. In ERαAF-1+/+ and ERαAF-10 mice, both basal and E2-stimulated reendothelialized areas were similar at day 3 postinjury (Fig. 2B). As described (27), the regeneration involved a large area of proliferating endothelial cell defined by BrdU immunostaining, named the “regenerative endothelial area” that is enlarged by E2 in ERαAF-1+/+ mice (Fig. 2B). This E2 effect is caused by an enlargement of both the reendothelialized area and the retrograde proliferating area of uninjured endothelium (RetroP). These actions of E2 were similar in ERαAF-1+/+ and ERαAF-10 mice (Fig. 2B).

Altogether, the effect of E2 on NO production and the reendothelialization process in ERαAF-10 mice was similar to that observed in ERαAF-1+/+ mice. These results unambiguously demonstrate that the N-terminal A/B region, and therefore ERα AF-1, is dispensable for these two ERα-mediated vasculoprotective effects.

The Atheroprotective Effect of E2 Depends on ERα but Not on ERα AF-1.

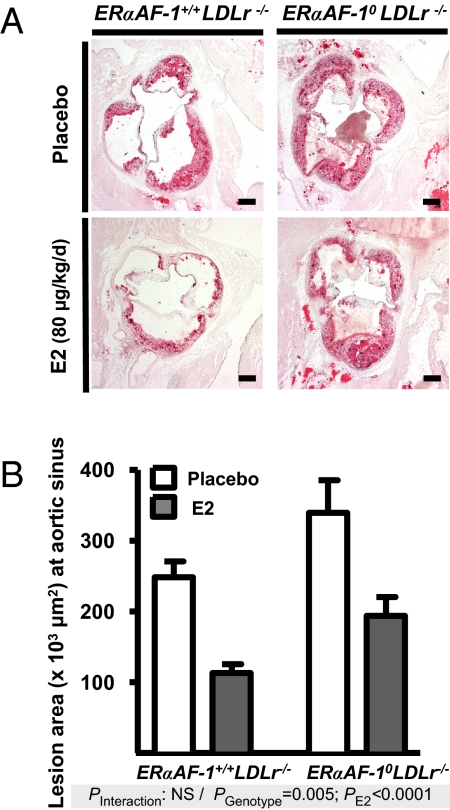

It was shown that ERα mediates most of the atheroprotective effects of E2 in the αERKO mice (28). However, a residual effect of E2 was still apparent in 25% of these mice. Thus, we first decided to reconsider the question using the ERα−/− mice model devoid of any ERα expression. The prevention of fatty streak deposit by E2 was abolished in ERα−/−LDLr−/− (low-density lipoprotein receptor) mice, definitely demonstrating that ERα mediates the atheroprotective effect of E2 (Table 1 and Fig. S1). We next tested the involvement of ERα AF-1 on this process. To this aim, we bred ERαAF-1+/− mice with LDLr−/− mice to obtain ERαAF-10 LDLr−/− and ERαAF-1+/+ LDLr−/− mice. As expected, exogenous E2 (80 μg/kg per day for 12 weeks) significantly decreased fatty streak deposits at the aortic sinus from ovariectomized 18-week-old ERαAF-1+/+ LDLr−/− mice exposed to a hypercholesterolemic diet (Fig. 3). This atheroprotective effect of E2 was similar in ERαAF-10 LDLr−/− mice, as indicated in the two-way ANOVA by an absence of interaction (P = 0.85), and a highly significant effect of E2 treatment (P < 0.0001). Placebo-treated mice showed neither a significant change in total plasma cholesterol, nor in HDL-cholesterol, according to the genotype (Table 2). As proposed (4, 29, 30), the atheroprotective effect of E2 seems to be the consequence of a direct action on the cells of the arterial wall rather than an effect on the lipoprotein profile. Indeed, E2 treatment decreased total plasma cholesterol in both ERαAF-1+/+ LDLr−/− and ERαAF-10 LDLr−/− mice but no trend toward a change was observed on total cholesterol/HDL-cholesterol ratio. Noteworthy, the surface of the lesions was larger in ERαAF-10 LDLr−/− mice than in ERαAF-1+/+ LDLr−/− mice at the level of the aortic sinus, irrespective of treatment (Fig. 3). This unexpected observation is demonstrated by the results of the two-way ANOVA that clearly indicated an independence between the effect of E2 and the effect of the genotype ERαAF-10.

Table 1.

Effect of E2 treatment in 18-week-old ERα+/+ LDLr−/− and ERα−/− LDLr−/− mice on fatty streak lesion size

| Measure |

ERα+/+LDLr−/− |

ERα−/−LDLr−/− |

P, two-factor ANOVA |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | E2 | Placebo | E2 | Genotype | E2 | Interaction | |

| Body weight, g | 22.2 ± 1.3 | 22.1 ± 0.7 | 24.5 ± 1.0 | 22.9 ± 0.6 | NS | NS | NS |

| Uterine weight, mg | <10 | 95.3 ± 21 | <10 | <10 | — | — | — |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 1,644 ± 100 | 1,009 ± 68** | 1,534 ± 108 | 1,432 ± 150 | — | — | 0.04 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 317 ± 11 | 199 ± 15*** | 318 ± 16 | 290 ± 16 | — | — | 0.009 |

| Cholesterol/HDL ratios | 5.2 ± 0.2 | 5.1 ± 0.2 | 4.8 ± 0.2 | 4.9 ± 0.2 | NS | NS | NS |

| Lesions, × 103 μm2 | 365 ± 43 | 160 ± 25*** | 303 ± 35 | 264 ± 24 | — | — | 0.027 |

Results are expressed as means ± SEM. To test the role of E2 treatment and genotype, 2-way ANOVA was performed. When an interaction was observed between the 2 factors, the effect of E2 treatment was studied in each genotype by using a Bonferroni posttest (**, P < 0.01;

***, P < 0.001). NS, not significant.

Fig. 3.

Exogenous E2 prevents fatty streak deposits in 18-week-old ERαAF-10 mice. Four-week-old ovariectomized ERαAF-1+/+LDLr−/− and ERαAF-10LDLr−/− mice were given either placebo or E2 (80 μg/kg per day for 12 weeks) and switched to atherogenic diet from the age of 6–18 weeks. (A) Representative micrographs of Oil red-O lipid stained cryosections of the aortic sinus. (Scale bars: 200 μm.) (B) Quantification (mean ± SEM) of lesion area at the aortic sinus from an average of 7–8 mice per group. Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA, and no significant interaction (P = 0.85) was observed.

Table 2.

Effect of E2 treatment on body weight, uterine weight, plasma lipid concentrations, and fatty streak lesion size in 18-week-old AF-1+/+ LDLr−/− and AF-10 LDLr−/− mice

| Measure |

AF-1+/+LDLr−/− |

AF-10LDLr−/− |

P, two-factor ANOVA |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | E2 | Placebo | E2 | Genotype | E2 | Interaction | |

| Body weight, g | 22.6 ± 1.1 | 23.6 ± 1.0 | 20.5 ± 1.2 | 21.7 ± 1.1 | NS | NS | NS |

| Uterine weight, mg | <10 | 127 ± 12 | <10 | 26 ± 9 | — | — | — |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 1,177 ± 127 | 893 ± 123 | 1,261 ± 98 | 828 ± 105 | NS | 0.009 | NS |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 241 ± 37 | 220 ± 11 | 305 ± 45 | 189 ± 16 | NS | 0.02 | NS |

| Cholesterol/HDL ratios | 4.6 ± 0.2 | 4.4 ± 0.5 | 4.3 ± 0.3 | 4.3 ± 0.3 | NS | NS | NS |

| Lesions, × 103 μm2 | 247 ± 20 | 112 ± 11 | 338 ± 41 | 192 ± 26 | 0.0054 | <0.0001 | NS |

Results are expressed as means ± SEM. NS, not significant.

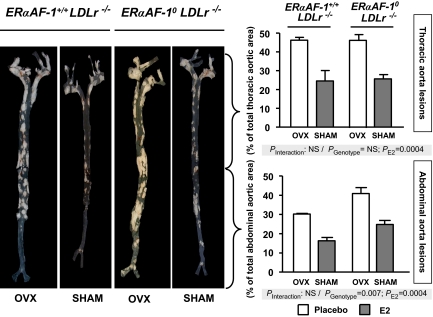

We then evaluated the role of ERα (Fig. S1) and its AF-1 (Fig. 4 and Table 3) in the atheroprotective effect of endogenous estrogens at late stages of atheroma by assessing en face preparations of the aortic tree from 8-month-old ovariectomized or sham-operated female mice. Again, no significant change in the lipoprotein profile was observed in ovariectomized ERαAF-1+/+ LDLr−/−, ERα−/− LDLr−/−, and ERαAF-10 LDLr−/− mice, irrespective of the hormonal status (Table 3 and data not shown).

Fig. 4.

The atheroprotective effect of endogenous estrogens persists in 8-month-old ERαAF-10 mice. Four-week-old ERαAF-1+/+ LDLr−/− and ERαAF-10 LDLr−/− mice were ovariectomized (OVX) or not (SHAM) and switched to atherogenic diet from the age of 6 weeks until euthanization. (A) Representative en face aorta preparations (1.8× magnification) from groups of 5 mice. (B) Quantification of lesions (mean ± SEM) from the thoracic and the abdominal aorta expressed as percentage of total aorta area. Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA, and no significant interaction was observed for either thoracic (P = 0.87) or abdominal (P = 0.76) aortae.

Table 3.

Effect of endogenous estrogens on body weight, uterine weight, plasma lipid concentrations, and fatty streak lesion size in 8-month-old AF-1+/+ LDLr−/− and AF-10LDLr−/− mice

| Measure |

AF-1+/+LDLr−/− |

AF-10LDLr−/− |

P, two-factor ANOVA |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ovx | Sham | Ovx | Sham | Genotype | E2 | Interaction | |

| Body weight, g | 27.5 ± 0.1 | 23.9 ± 0.6 | 27.8 ± 1.5 | 28 ± 0.7 | NS | NS | NS |

| Uterine weight, mg | <10 | 86.9 ± 7 | <10 | 28.3 ± 5 | — | — | — |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 822 ± 103 | 877 ± 109 | 1,108 ± 118 | 821 ± 82 | NS | NS | NS |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 191 ± 2 | 185 ± 9 | 254 ± 25 | 198 ± 10 | NS | NS | NS |

| Cholesterol/HDL ratios | 4.3 ± 0.5 | 4.7 ± 0.4 | 4.4 ± 0.3 | 4.1 ± 0.2 | NS | NS | NS |

| Aortic root lesions, × 103 μm2 | 789 ± 52 | 861 ± 63 | 882 ± 17 | 895 ± 84 | NS | NS | NS |

| Aorta lesion,% | |||||||

| Thoracic | 46.5 ± 1.3 | 24.6 ± 5.6 | 46.5 ± 3.9 | 26 ± 2 | NS | 0.0004 | NS |

| Abdominal | 30.3 ± 0.3 | 16.1 ± 1.9 | 40.7 ± 3.3 | 24.8 ± 2.2 | 0.007 | 0.0004 | NS |

Results are expressed as means ± SEM. NS, not significant.

Endogenous estrogens decreased the lesion size in both thoracic (−61%) and abdominal (−68%) aortae from ERα+/+ LDLr−/− mice (Fig. S1). Once again, this protective effect was shown to be fully dependent on ERα, because it was abolished in ERα−/− LDLr−/− mice (Fig. S1). However, compared with ERαAF-1+/+ LDLr−/− mice, the atheroprotective effect of endogenous estrogens was similar in intact ERαAF-10 LDLr−/− mice both at the level of the thoracic and the abdominal aorta (reduction by 44% and 39% respectively), as indicated by two-way ANOVA. Indeed, no interaction was observed between the hormonal status and the genotype (P = 0.87 and 0.76 for the thoracic and abdominal aorta, respectively), demonstrating that ERα AF-1 is not required for the atheroprotective effect of endogenous estrogens (Fig. 4). Interestingly, as observed for the 18-week-old mice, the surface of the lesions in the abdominal aorta in 8-month-old mice was larger in ERαAF-10 LDLr−/− mice than in control littermates, no matter the hormonal status (Fig. 4; P = 0.007).

The size and collagen content of atherosclerotic lesions at the aortic sinus was also evaluated in these 8-month-old mice. In contrast to the clear atheroprotective effect of endogenous estrogens on the less advanced lesions in thoracic and abdominal aortae, we did not observe any effect of endogenous estrogens at the aortic sinus, irrespective of the genotype, potentially as a consequence of a saturation of the atheromatous process at this site (Fig. S2).

Taken together, these data clearly demonstrate that ERα AF-1 is not necessary to mediate the atheroprotective effect of both endogenous and exogenous estrogens. In addition, we observed an atheroprotective role of the ERα A/B domain that is independent of E2.

Discussion

To determine the role of ERα AF-1 in the vascular effects of estrogens, we have generated a targeted deletion in mouse by using a knockin strategy, through which the sequence coding for the main part of the A/B region, including AF-1, was excised. This mouse model allowed us to study the physiological role of ERα AF-1 in vivo. Both ERαAF-10 male and female mice were unfertile when homozygous (M.-C. Antal, A. Krust, P. Chambon, and M. Mark, unpublished work), demonstrating the crucial role of ERα AF-1 for reproduction and necessitating the use of heterozygous progenitors.

E2-elicited NO production was shown to prevent vasospasm (31) and platelet aggregation (32), both processes being involved in the atherogenesis process or its complications. In this study, we observed that E2-induced increase of basal NO production and the acceleration of reendothelialization were unchanged in ERαAF-10 mice (Fig. 2), whereas those E2 effects were abolished in ERα−/− mice (6, 10). Although suggested by the persisting effect of E2 on NO production (18) and the prevention of the postinjury medial hyperplasia (19) with the αERKO mice, we directly demonstrate that these two E2 actions are ERα AF-1-independent.

The preventive effect of estrogens against fatty streak deposit has been established in several animal models (30, 33, 34), including hypercholesterolemic mouse models such as ApoE−/− (apolipoprotein E) (4, 5) and LDLr−/− mice (29, 35). Even though the atheroprotective effect of E2 was lost in αERKO ApoE−/− mice, a minority of mice (4 of 14) were still protected (28). One hypothesis that could explain this observation is the variability of the expression level of the chimeric receptor lacking AF-1 in αERKO mice (24) (see Introduction). Here, we first showed that the atheroprotective action of E2 was abolished in ERα−/−LDLr−/− mice, at the ages of 18 weeks (Table 1) and 8 months (Fig. S1). Second, we demonstrated unambiguously that ERα AF-1 is completely dispensable for mediating the atheroprotective effect of both endogenous and exogenous estrogens. Third, we found that the A/B domain exerts an atheroprotective action independently of the binding of E2 to ERα, because ERαAF-10 LDLr−/− mice had larger lesions both at the aortic sinus (18 weeks; Fig. 3) and at the abdominal aorta site (8 months; Fig. 4), no matter the hormonal status.

ERα AF-1 box 2 and 3 are targets for several protein kinases, which could contribute to this ligand-independent atheroprotective effect. In particular, serine residues such as S104, S106, and/or S118 (corresponding to S108, S110, and S122 in mouse ERα) are substrates for MAP kinases (36–38), glycogen synthase kinase 3β (39), the cyclinA/cdk2 complex (40), and Cdk7 (41). Even though the impact of these posttranslational modifications has not yet been evaluated in vivo, they could potentially be part of the mechanisms involved in the ligand-independent atheroprotective action we observed in this study. However, this effect could also be caused by the absence of the A domain that represses the ligand-independent transcriptional activities of ERα via an interaction with the E domain (42).

Until now, the respective physiological roles of the full-length ERα66 (harboring both AF-1 and AF-2) and the shorter AF-1-deficient ERα46 have remained elusive. However, this work demonstrates that the vasculoprotective actions of E2 could be mediated by ERα46. The respective contribution of AF-1 and AF-2 to the transcriptional activity of the full-length ERα is both promoter- and cell-dependent (12, 15). Moreover, a small pool of ER localized at the plasma membrane can induce rapid no genomic signaling called membrane-initiated steroid signaling (MISS) in response to E2 (43). Interestingly, it has been shown that deletion of the A/B or C domain has little consequence on membrane localization and function (44), illustrating the ability of both ERα66 and ERα46 to mediate MISS effects (16, 17). Future work will have to determine: (i) to which extent the ERα46 isoform is physiologically or pathophysiologically expressed in human vascular cells, and (ii) the respective contribution of ERα AF-2 mediated transcription and ERα MISS activity in the vascular effects of E2.

Interestingly, the role of ERα AF-1 in uterine hyperplasia was suggested by using the first generation of αERKO (18, 20) and fully demonstrated in the double αβ DERKO mice (22, 45) compared with ERα−/− mice (18, 21). These studies suggest not only a critical role of ERα, but also substantial role of ERα AF-1 in the proliferation and morphogenesis of reproductive tissues. In any case, the E2-induced uterine hyperplasia relies heavily on ERα AF-1 (Fig. 1C and M.-C. Antal, A. Krust, P. Chambon, and M. Mark, unpublished work), further emphasizing its importance in the E2 effect on this major estrogen-dependent target.

To conclude, the present study demonstrates that the ERα A/B domain and thus its AF-1 is dispensable for the signaling leading to at least three major vasculoprotective effects of E2, increase of basal endothelial NO production, acceleration of endothelial healing, and prevention of the atheromatous process. The role of ERα AF-1 in other E2 beneficial actions on bone or insulin sensitivity, for instance, and the complex actions on breast cancer development should be assessed in future studies. Nevertheless, the present work already suggests that selective ER modulators stimulating ERα independently of the A/B domain, i.e., with minimal activation of ERα AF-1, could retain beneficial vascular effects with minimal sexual actions.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

All experimental procedures involving animals were performed in accordance with the principles and guidelines established by the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale and were approved by the local Animal Care and Use Committee. Mice were housed in cages in groups of 5 and kept in a temperature-controlled facility on a 12-h light–dark cycle. ERα-null (ERα−/−) mice were generated as described (21). ERα AF-1-deficient (ERα AF-10) mice were generated through the strategy outlined in Fig. 1 and as described (M.-C. Antal, A. Krust, P. Chambon, and M. Mark, unpublished work). Briefly, 441 bp of exon 1 (corresponding to amino acids 2–148) were deleted through homologous recombination, thus preserving the translational initiation codon (ATG1) in exon 1 and 20 bp at the 3′ extremity of exon 1. This preservation ensured a correct recognition of the splicing donor site and hence of exon 1 by the spliceosome. To generate the double-deficient mice, LDLr−/− female mice, purchased from Charles River (35), were crossed with ERαAF-1+/− males. Heterozygous LDLr+/−ERαAF-1+/− mice were used to generate LDLr−/−ERαAF-1+/− mice, which were used as parental progenitors. Normocholesterolemic control mice corresponded to wild-type (ERαAF-1+/+) littermates and hypercholesterolemic control mice corresponded to wild-type (ERαAF-1+/+ or ERα+/+) littermates deficient in LDLr.

Ovariectomization was performed at 4 weeks of age, and concomitantly (for carotid artery injury and aortic ring experiments) the mice received pellets s.c. releasing either placebo or E2 (0.1 mg, 60 days release, i.e., 80 μg/kg per day; Innovative Research of America). We systematically checked that placebo-treated ovariectomized mice had an atrophied uterus (<10 mg), nondetectable circulating levels of E2 (<5 pg/mL, i.e., <20 pM), and that those implanted with an E2-releasing pellet had a significant increase in uterine weight and serum E2 concentrations (100–150 pg/mL; data not shown), irrespective of the genotype.

In atherosclerosis experiments, mice received pellets at weeks 6 and 12. At 6 weeks of age, the mice were switched to a hypercholesterolemic atherogenic diet (1.25% cholesterol, 6% fat, no cholate; TD96335; Harlan Teklad). At 18 weeks or 8 months of age, overnight-fasted mice were anesthetized, and blood was collected from the retroorbital venous plexus. Upon euthanization, the heart, the ascending aorta (aortic sinus), the thoracic and abdominal aorta, and the uterus were carefully dissected. For the studies on aortic sinus in 18-week-old mice the groups contained an average of 8 mice, and for en face studies in 8-month-old mice the groups contained an average of 5 mice.

Determination of Serum Lipids.

Total plasma cholesterol was assayed by using the CHOD-PAD kit (Horiba ABX). The HDL fraction was isolated from 10 μL of serum and assayed with C-HDL + third-generation kit (Roche).

Isolated Vascular Ring Experiments.

Mice were exposed to either placebo or E2 for 2 weeks before euthanization. Four 3-mm-long ring segments were obtained from the descending thoracic aorta. They were suspended in individual organ chambers filled with 5 mL of Krebs buffer: 118.3 mM NaCl, 4.69 mM KCl, 1.25 mM CaCl2, 1.17 mM MgSO4, 1.18 mM K2HPO4, 25.0 mM NaHCO3, and 11.1 mM glucose, pH 7.40. The solution was aerated continuously with 95% O2/5% CO2 and maintained at 37 °C. Tension was recorded with a linear force transducer. The resting tension was gradually increased to 1 g over 45 min, and the ring segments were exposed to 80 mM KCl until the optimal isometric contraction was reached. After washout, the vessels were left at the resting tension throughout the study. They were contracted with l-phenylephrine (Phe) (3 μM) to determine maximal contraction and then precontracted to 80% of that value (Phe; 0.25 μM). Basal NO production by aortic ring was evaluated from the contraction elicited after 30 min with NG-nitro-l-arginine (final concentration: 100 μM) added to rings precontracted for 30 min with the thromboxane A2 mimetic U-46619 (7.5 nM). Data were collected with Acknowledge software (Biopac System).

Mouse Carotid Injury and Quantification of Reendothelialization.

Mice were exposed to either placebo or E2 for 2 weeks before surgery and until euthanization, 3 days later. The mice were anesthetized by injection of ketamine (100 mg·kg−1) and xylazine (10 mg·kg−1) by i.p. route. The carotid electric injury was performed as described (10). Briefly, surgery was carried out with a stereomicroscope (Nikon SMZ800), and the left common carotid artery was exposed via an anterior incision in the neck. The electric injury was applied to the distal part (4 mm precisely) of the common carotid artery with a bipolar microregulator. We recently compared the kinetics of reendothelialization of mouse carotid arteries in the conventional endovascular and a perivascular electric injury model by Evans blue staining and found similar basal healing kinetics and accelerative action of E2 in both models (27). The electric injury model in combination with en face confocal microscopy was used to visualize the endothelial monolayer and study reendothelialization and was performed as described (27).

Morphometric Analyses of Fatty Streak Lesions.

Fatty streak lesion size was estimated at the aortic sinus as described (46). Collagen fibers were stained with Sirius red. The lesion collagen content was determined by measuring the relative area/density in 12 contiguous fields in each Sirius red-stained section.

The entire aortic tree was removed and cleaned of adventitia, split longitudinally to the iliac bifurcation, and pinned flat on a dissection pan for analysis by en face preparation. Images were captured with a Sony 3CCD video camera, and the fraction covered by lesions was evaluated as a percentage of the total aortic area.

Western Blot Analysis.

Dissected uteri were homogenized by using a glass potter in lysis buffer [20 mM Tris·HCl (pH 8), 100 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM EDTA (pH 8), 20 mM NaF, proteinase inhibitors (Complete EDTA-free; Roche], 1 mM PMSF, and 2 mM orthovanadate, sonicated, and centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. Fifty micrograms of protein of the supernatant was separated by SDS/PAGE (10%) and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. Blocking (1 h at room temperature) and incubation with primary rabbit anti-mouse ERα antibody (MC-20; Santa Cruz Biotechnology; dilution 1/1,000) (overnight, 4 °C) and secondary antibody (goat HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG, Cell Signaling Technology 7074; dilution 1/10,000) (1 h, room temperature) was done in TBST containing 3% dry milk. ECL West Pico (Pierce) was used to reveal signals.

Statistical Analyses.

Results are expressed as means ± SEM. To test the roles of E2 treatment and genotype (ERα or ERα AF-1 deficiency) a two-way ANOVA was performed. When an interaction was observed between the two factors, the effect of E2 treatment was studied in each genotype by using a Bonferroni post test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Professor F. Bayard for his input in the work of our team over many years; Dr. J. C. Faye and Professor K. Korach for sharing their knowledge of ERs; the staff of the IFR31 animal facility and the Plateforme d'Experimentation Fonctionnelle at the Institut de Médecine Moléculaire de Rangueil for skillful technical assistance; and H. Bergès and L. Libert for technical support. The work at the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale Unité 858 was supported by Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, Université Paul Sabatier and Faculté de Médecine Toulouse-Rangueil, the European Vascular Genomics Network (European Community's Sixth Framework Program for Research Contract LSHM-CT-2003-503254), the Fondation de France, the Fondation de l'Avenir, and the Conseil Régional Midi-Pyrénées. The work at the Institut de Génétique et de Biologie Moléculaire et Cellulaire was supported by European Project Estrogen in Women Aging Contract LSHM-CT-2005-518245. A.B.-G. was supported by a grant from the Société Française d'Hypertension Artérielle.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0808742106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Rossouw JE, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: Principal results from the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2002;288:321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mendelsohn ME, Karas RH. HRT and the young at heart. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2639–2941. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe078072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rossouw JE, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of cardiovascular disease by age and years since menopause. J Am Med Assoc. 2007;297:1465–1477. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.13.1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elhage R, et al. Estradiol-17β prevents fatty streak formation in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Arterioscl Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:2679–2684. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.11.2679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bourassa PA, Milos PM, Gaynor BJ, Breslow JL, Aiello RJ. Estrogen reduces atherosclerotic lesion development in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:10022–10027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Darblade B, et al. Estradiol alters nitric oxide production in the mouse aorta through the α-, but not β-, estrogen receptor. Circ Res. 2002;90:413–419. doi: 10.1161/hh0402.105096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caulin-Glaser T, Watson CA, Pardi R, Bender JR. Effects of 17β-estradiol on cytokine-induced endothelial cell adhesion molecule expression. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:36–42. doi: 10.1172/JCI118774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Razandi M, Pedram A, Levin ER. Estrogen signals to the preservation of endothelial cell form and function. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:38540–38546. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007555200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krasinski K, et al. Estradiol accelerates functional endothelial recovery after arterial injury. Circulation. 1997;95:1768–1772. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.7.1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brouchet L, et al. Estradiol accelerates reendothelialization in mouse carotid artery through estrogen receptor-α but not estrogen receptor-β. Circulation. 2001;103:423–428. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.3.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krust A, et al. The chicken oestrogen receptor sequence: Homology with v-erbA and the human oestrogen and glucocorticoid receptors. EMBO J. 1986;5:891–897. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04300.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tora L, et al. The human estrogen receptor has two independent nonacidic transcriptional activation functions. Cell. 1989;59:477–487. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flouriot G, et al. Identification of a new isoform of the human estrogen receptor-α (hER-α) that is encoded by distinct transcripts and that is able to repress hER-α activation function 1. EMBO J. 2000;19:4688–4700. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.17.4688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barraille P, Chinestra P, Bayard F, Faye JC. Alternative initiation of translation accounts for a 67/45-kDa dimorphism of the human estrogen receptor ERα. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;257:84–88. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berry M, Metzger D, Chambon P. Role of the two activating domains of the oestrogen receptor in the cell-type- and promoter-context-dependent agonistic activity of the anti-oestrogen 4-hydroxytamoxifen. EMBO J. 1990;9:2811–2818. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07469.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Figtree GA, McDonald D, Watkins H, Channon KM. Truncated estrogen receptor α 46-kDa isoform in human endothelial cells: Relationship to acute activation of nitric oxide synthase. Circulation. 2003;107:120–126. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000043805.11780.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li L, Haynes MP, Bender JR. Plasma membrane localization and function of the estrogen receptor α variant (ER46) in human endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:4807–4812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0831079100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pendaries C, et al. The AF-1 activation-function of ERα may be dispensable to mediate the effect of estradiol on endothelial NO production in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:2205–2210. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042688499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iafrati MD, et al. Estrogen inhibits the vascular injury response in estrogen receptor α-deficient mice. Nat Med. 1997;3:545–548. doi: 10.1038/nm0597-545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lubahn DB, et al. Alteration of reproductive function but not prenatal sexual development after insertional disruption of the mouse estrogen receptor gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11162–11166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.11162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dupont S, et al. Effect of single and compound knockouts of estrogen receptors α (ERα) and β (ERβ) on mouse reproductive phenotypes. Development. 2000;127:4277–4291. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.19.4277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pare G, et al. Estrogen receptor-α mediates the protective effects of estrogen against vascular injury. Circ Res. 2002;90:1087–1092. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000021114.92282.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Couse JF, et al. Analysis of transcription and estrogen insensitivity in the female mouse after targeted disruption of the estrogen receptor gene. Mol Endocrinol. 1995;9:1441–1454. doi: 10.1210/mend.9.11.8584021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kos M, Denger S, Reid G, Korach KS, Gannon F. Down but not out? A novel protein isoform of the estrogen receptor α is expressed in the estrogen receptor α knockout mouse. J Mol Endocrinol. 2002;29:281–286. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0290281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Metzger D, Ali S, Bornert JM, Chambon P. Characterization of the amino-terminal transcriptional activation function of the human estrogen receptor in animal and yeast cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:9535–9542. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.16.9535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Billon A, et al. The estrogen effects on endothelial repair and mitogen-activated protein kinase activation are abolished in endothelial nitric oxide (NO) synthase knockout mice, but not by NO synthase inhibition by N-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:830–838. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Filipe C, et al. Estradiol accelerates endothelial healing through the retrograde commitment of uninjured endothelium. Am J Physiol. 2008;294:H2822–H2830. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00129.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hodgin JB, et al. Estrogen receptor α is a major mediator of 17β-estradiol's atheroprotective effects on lesion size in Apoe−/− mice. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:333–340. doi: 10.1172/JCI11320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marsh MM, Walker VR, Curtiss LK, Banka CL. Protection against atherosclerosis by estrogen is independent of plasma cholesterol levels in LDL receptor-deficient mice. J Lipid Res. 1999;40:893–900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arnal JF, Scarabin PY, Tremollieres F, Laurell H, Gourdy P. Estrogens in vascular biology and disease: Where do we stand today? Curr Opin Lipidol. 2007;18:554–560. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e3282ef3bca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miyagawa K, Rosch J, Stanczyk F, Hermsmeyer K. Medroxyprogesterone interferes with ovarian steroid protection against coronary vasospasm. Nat Med. 1997;3:324–327. doi: 10.1038/nm0397-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakano Y, Oshima T, Matsuura H, Kajiyama G, Kambe M. Effect of 17β-estradiol on inhibition of platelet aggregation in vitro is mediated by an increase in NO synthesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18:961–967. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.6.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clarkson TB, Appt SE. Controversies about HRT: Lessons from monkey models. Maturitas. 2005;51:64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2005.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hodgin J, Maeda N. Estrogen and mouse models of atherosclerosis. Endocrinology. 2002;143:4495–4501. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elhage R, et al. The atheroprotective effect of 17-estradiol depends on complex interactions in adaptive immunity. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:267–274. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)62971-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kato S, et al. Activation of the estrogen receptor through phosphorylation by mitogen-activated protein kinase. Science. 1995;270:1491–1494. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5241.1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bunone G, Briand PA, Miksicek RJ, Picard D. Activation of the unliganded estrogen receptor by EGF involves the MAP kinase pathway and direct phosphorylation. EMBO J. 1996;15:2174–2183. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thomas RS, Sarwar N, Phoenix F, Coombes RC, Ali S. Phosphorylation at serines 104 and 106 by Erk1/2 MAPK is important for estrogen receptor-α activity. J Mol Endocrinol. 2008;40:173–184. doi: 10.1677/JME-07-0165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Medunjanin S, et al. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 interacts with and phosphorylates estrogen receptor α and is involved in the regulation of receptor activity. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:33006–33014. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506758200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rogatsky I, Trowbridge JM, Garabedian MJ. Potentiation of human estrogen receptor α transcriptional activation through phosphorylation of serines 104 and 106 by the cyclin A-CDK2 complex. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:22296–22302. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.32.22296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen D, et al. Activation of estrogen receptor α by S118 phosphorylation involves a ligand-dependent interaction with TFIIH and participation of CDK7. Mol Cell. 2000;6:127–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Metivier R, et al. A dynamic structural model for estrogen receptor-α activation by ligands, emphasizing the role of interactions between distant A and E domains. Mol Cell. 2002;10:1019–1032. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00746-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hammes SR, Levin ER. Extranuclear steroid receptors: Nature and actions. Endocr Rev. 2007;28:726–741. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Razandi M, et al. Identification of a structural determinant necessary for the localization and function of estrogen receptor α at the plasma membrane. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:1633–1646. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.5.1633-1646.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karas RH, et al. Effects of estrogen on the vascular injury response in estrogen receptor α, β (double) knockout mice. Circ Res. 2001;89:534–539. doi: 10.1161/hh1801.097239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gourdy P, et al. Transforming growth factor activity is a key determinant for the effect of estradiol on fatty streak deposit in hypercholesterolemic mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2214–2221. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.150300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.