Abstract

Obliterative bronchiolitis (OB) is a major cause of allograft dysfunction after lung transplantation and is thought to result from immunologically mediated airway epithelial destruction and luminal fibrosis. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) have been implicated in the regulation of lung inflammation, airway epithelial repair, and extracellular matrix remodeling and therefore may participate in the pathogenesis of OB. The goals of this study were to determine the expression profiles of MMPs and TIMPs and the role of TIMP-1 in the development of airway obliteration using the murine heterotopic tracheal transplant model of OB. We demonstrate the selective induction of MMP-3, MMP-9, MMP-12, and TIMP-1 in a temporally restricted manner in tracheal allografts compared with isografts. In contrast, the expression of MMP-7, TIMP-2, and TIMP-3 was decreased in allografts relative to isografts during the period of graft rejection. TIMP-1 protein localized to epithelial, mesenchymal, and inflammatory cells in the tracheal grafts in a temporally and spatially restricted manner. Using TIMP-1–deficient mice, we demonstrate that the absence of TIMP-1 in the donor trachea or the allograft recipient reduced luminal obliteration and increased re-epithelialization in the allograft compared with wild-type control at 28 d after transplantation. Our findings provide direct evidence that TIMP-1 contributes to the development of airway fibrosis in the heterotopic tracheal transplant model, and suggest a potential role for this proteinase inhibitor in the pathogenesis of OB in patients with lung transplant.

Keywords: heterotopic tracheal transplant, matrix metalloproteinase, obliterative bronchiolitis, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase

Lung transplantation is often the only hope for patients with end-stage lung disease. However, 5-yr survival is only 45%, with the majority of deaths resulting from complications of obliterative bronchiolitis (OB) (1). OB is a histopathologic diagnosis characterized by mature collagen deposition resulting in occlusion of the small airways accompanied by infiltration of inflammatory cells and proliferating fibroblasts (2, 3). Due to the insensitivity of transbronchial biopsies to make a histologic diagnosis of OB in patients with lung transplant, a clinical equivalent, called bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS), was created and is based on findings from pulmonary function tests that show increased airflow obstruction over baseline (4). Treatment of OB with increased immunosuppression is generally ineffective (1–3). A better understanding of the pathogenesis of OB has been gained through the use of the heterotopic tracheal transplant model (5–7). This model develops obliterative airway disease (OAD) that is histologically similar to the lesion observed in OB. Although the OAD that develops in the heterotopic tracheal transplant is not a perfect correlate of OB, similarities between the histopathology of OAD and OB are irrefutable.

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are a family of structurally related neutral proteinases that require zinc interactions in their catalytic domain for proper function (8). In vitro, MMPs have the ability to degrade substrates of the extracellular matrix (ECM) and non-ECM components (8). Collectively, MMPs can regulate multiple biological processes, such as organ morphogenesis, tumor metastasis, wound repair, inflammation, and innate immunity (8–10). The pleiotropic functions of MMPs are tightly regulated through gene expression, compartmentalization to the pericellular environment, pro-enzyme activation, and enzyme inactivation (8). An important mechanism of MMP regulation is provided by tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase (TIMPs), which have been shown to block MMP proteolytic activity in vitro. TIMP-1, -2, -3, and -4 are structurally related molecules that have multiple biological activities (11). Each inhibitor noncovalently binds to the MMP with 1:1 stoichiometry such that the amino-terminal domain of the TIMP occupies and blocks the substrate recognition site of the catalytic domain of the MMP (11).

Chronic lung allograft dysfunction is thought to be the result of persistent low-grade inflammation leading to abnormal repair and excessive ECM accumulation along epithelial surfaces (2, 3, 12). A dynamic balance between MMP and TIMP activity is postulated to be important in the regulation of inflammation, re-epithelialization, and wound healing. Therefore, it is not surprising to find differential expression of MMPs and TIMPs in the lungs of patients with OB (13–17). For example, levels of MMP-9 and TIMP-1 are increased in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BAL) recovered from patients with BOS (13). This indirect evidence suggests that members of the MMP and TIMP gene families may make important contributions to the development of OB.

In this study, we report the selective induction of stromelysin-1 (MMP-3), gelatinase-B (MMP-9), macrophage metalloelastase (MMP-12), and TIMP-1 in a temporally restricted manner in heterotopically transplanted mouse tracheas. Furthermore, TIMP-1 protein localized to epithelial, mesenchymal, and inflammatory cells of tracheal grafts in distinct temporal patterns. To directly investigate the importance of TIMP-1 in the development of OAD, we analyzed luminal obliteration and airway re-epithelialization of wild-type tracheas transplanted into TIMP-1–deficient mice and TIMP-1–deficient tracheas transplanted into wild-type mice compared with wild-type control mice. We observed that luminal obliteration was reduced and that re-epithelialization of the airway increased after heterotopic tracheal transplantation when TIMP-1 was deficient in the donor or recipient compared with wild-type tracheas implanted into wild-type recipients. Our results provide direct evidence that TIMP-1 contributes to the development of OAD and may be a potential target for treatment in patients with OB.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Laboratory Animals

TIMP-1 null (−/−) mutation and wild-type (TIMP-1 +/+) mice were bred from C57BL/6 (H2-b) mice heterozygous for a targeted disruption of exon 3 of the TIMP-1 gene (18). TIMP-1–deficient mice have previously been backcrossed onto the C57Bl/6 strain for 10 generations. Balb/c (H2-d) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). The genotypes of wild-type and TIMP-1 −/− mice were confirmed by PCR analysis performed on DNA prepared from the tails of 3-wk-old animals as previously described (18).

Heterotopic Tracheal Transplantation

All mice were specific pathogen-free males 8–12 wk of age. At least four mice were used for each group and time point. Under intraperitoneal Avertin anesthesia, donor animals were prepared, and a median sternotomy was performed. The trachea was explanted and placed in cold sterile saline as described previously (6). A dorsolateral subcutaneous pocket was created in the recipient animal, and the donor trachea was heterotopically transplanted. Allograft transplants were performed by implanting tracheas from Balb/c mice into subcutaneous pouches of C57BL/6 recipient mice. Isograft transplants were performed using C57BL/6 mice as donors and recipients. Tracheas were recovered at Days 7, 14, and 28 after transplantation. After recovery, a 1-mm section from the middle of the trachea was removed, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and embedded in paraffin. The remaining two outer tracheal sections were combined and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C before RNA isolation with TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Heterotopic tracheal transplants with TIMP-1 −/− mice were also evaluated. Allografts were performed with TIMP-1 −/− tracheas implanted into wild-type Balb/c recipients or wild-type Balb/c tracheas implanted into TIMP-1 −/− recipients and compared with wild-type allografts. Tracheas were recovered at Day 28 after transplantation, and a 1-mm section from the center of the trachea was removed and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for histologic examination.

All animals received humane care in compliance with the Principles of Laboratory Animal Care, formulated by the National Society of Medical Research, and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, prepared by the Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources and published by the National Institute of Health (NIH Publication no. 86-23, revised 1985). All procedures involving the mice were approved by the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center Animal Studies Committee.

Morphologic Studies

Tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Digital photomicrographs of H&E-stained tracheal sections were produced with a Nikon E600 photomicroscope and MetaMorph 4.6 software. The images were downloaded and analyzed with ImageJ software (National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD).

The percentage of luminal obstruction in transplanted tracheas was calculated by outlining the inner surface of the cartilage (a line was drawn connecting the two ends of the tracheal cartilage) and using the cursor to trace the inner surface of the residual lumen. The cross-sectional area within the residual lumen was subtracted from the entire area contained within the cartilage. The percentage of luminal obstruction was calculated using the following formula:

|

In normal, unmanipulated tracheas, the respiratory epithelium and submucosa lie within the cartilaginous rings. Therefore, using this formula, normal tracheas demonstrate a baseline luminal obstruction value of ∼ 3%.

To determine the amount of re-epithelialization after transplantation, the linear distance of the original inner circumference of the trachea was determined. Areas of intact respiratory epithelium were traced, and the cumulative distance was measured. A percentage of the airway circumference that was lined by epithelium was calculated.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Steady-state mRNA expression was measured by quantitative real-time PCR using the ABI Prism 7900 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). In brief, total RNA was extracted from snap-frozen tracheas (TRIzol; Invitrogen), and the RNA quality was confirmed with an Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies Inc., Palo Alto, CA). First-strand cDNA was synthesized with Superscript II (Invitrogen). Reaction volumes were 20 μl with the following PCR conditions: 50°C for 2 min and 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of amplification at 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. Due to low expression levels of MMP-7, products were amplified for 50 cycles. cDNA created from total RNA isolated from the same isografts and allografts were used to determine the mRNA expression level for all the genes evaluated. All gene expression levels were normalized to levels of β-actin expression as an internal control. After normalization, there is no specific unit of measure, so the relative gene expression level was labeled as an arbitrary unit.

mRNA levels for β-actin; MMP-3, -7, -9, and -12; and TIMP-2, -3, and -4 were quantified using commercially available primer and probe sets (Assay-On-Demand, Applied Biosystems). TIMP-1 primers and probe were specially designed with Assay-By-Design (Applied Biosystems) to detect only wild-type TIMP-1 mRNA and not the truncated mRNA expressed by TIMP-1 −/− mice. TIMP-1 primer and probe sequences were as follows: forward primer 5′-CAGAACCGCAGT GAAGAGTTTC-3′, reverse primer 5′-GCTGCAGGCACTGATGTG-3′, and probe 5′- ATCACGGGCCGCCTAA -3′.

Immunohistochemistry

TIMP-1 immunohistochemistry was performed as previously described (19). Antigen retrieval was performed on 5-μm sections of mouse tracheal tissue using Target Retrieval Solution (DakoCytomation; Dako Corp., Carpinteria, CA) at 95°C for 20 min. Tissue sections were blocked for endogenous peroxidase activity and nonspecific protein. Sections were treated with affinity-purified goat polyclonal antibody to mouse recombinant TIMP-1 (1:40) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) followed by biotinylated donkey anti-goat antibody (1:400) (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA), which was visualized using an RTU Vectastain kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and the Envision DAB kit (DakoCytomation). The sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. Digital photomicrographs were produced with a Nikon E600 photomicroscope and MetaMorph 4.6 software (Molecular Devices Corp., Sunnyvale, CA). The digitized images were processed with Adobe Photoshop for Windows 7.0 software (Adobe Systems, Inc., Mountainview, CA) using identical parameters for all images. As a negative control, serial sections were stained with irrelevant goat IgG of the same isotype.

Statistical Analysis

Data are reported as mean ± SE. All statistical analyses were performed by the Mann-Whitney U test. Differences were considered significant at the P < 0.05 level.

RESULTS

Allografts Develop OAD after Heterotopic Tracheal Transplantation

Heterotopic transplantation of allografts resulted in the development of OAD. Luminal obliteration was readily apparent in allografts compared with isograft controls by Day 28 after transplantation (Figures 1A and 1B). Morphometry confirmed increased luminal obliteration in allografts compared with isografts at Day 14 (44% versus 16%, P < 0.05) and Day 28 (94% versus 15%, P < 0.0005), respectively (Figure 1C). A ciliated, pseudo-stratified columnar epithelium lined almost the entire lumen of the isograft by Day 28 after transplantation (Figure 1A, inset). In contrast, allografts were poorly re-epithelialized at Day 14 (27% versus 100%, P < 0.001) and Day 28 (0% versus 92%, P < 0.005) compared with isograft controls (Figure 1D). Thus, the mucociliary epithelium was effectively repaired, and the lumens did not obliterate in isografts, whereas the tracheal epithelium failed to regenerate, and luminal obliteration developed in allografts consistent with previous observations (7, 20).

Figure 1.

Tracheal histology at Day 28 after transplantation. (A) Isografts had patent lumens and were fully re-epithelialized with a ciliated pseudo-stratified, columnar epithelium (arrow) (H&E; bar = 50 μm; original magnification: ×200; insets ×20). (B) Allografts develop OAD with inflammatory and mesenchymal cell infiltration into the obliterated lumen. An epithelium is not present, and the basement membrane (arrowhead) is pulled away from the cartilage (*) (H&E; bar = 50 μm; original magnification: ×200; insets ×20). (C) Morphometric analysis of luminal obliteration. Mean values (± SE) for percentage of luminal obliteration of isografts (white column) and allografts (black column) after tracheal transplantation. Five transplanted tracheas were analyzed at each time point for each group. *P < 0.05; †P < 0.0005. (D) Morphometric analysis of re-epithelialization. Mean values (± SE) for percentage of the tracheal lumen covered with epithelial cells for isografts (white column) and allografts (black column) after tracheal transplantation. Five transplanted tracheas were analyzed at each time point for each group. *P < 0.005; †P < 0.001.

Expression of MMP-3, MMP-9, and MMP-12 Is Induced in Allografts versus Isografts after Heterotopic Tracheal Transplantation

To determine the temporal profile of expression for MMP-3 (stromelysin-1), MMP-7 (matrilysin), MMP-9 (gelatinase B), and MMP-12 (macrophage metalloelastase), we analyzed steady-state mRNA levels of isografts and allografts at Days 7, 14, and 28 after transplantation. Our data demonstrate the selective expression of MMPs in a temporally restricted manner after tracheal transplantation. The mRNA levels were increased in allografts compared with isografts for MMP-3 at Days 14 and 28 (Figure 2A) and for MMP-12 at Day 28 (Figure 2B). The mRNA levels of MMP-9 were increased several fold in allografts compared with isografts at Day 14 after transplantation (Figure 2C). Conversely, mRNA levels were decreased in allografts compared with isografts at Day 28 for MMP-9 (Figure 2C) and MMP-7 (Figure 2D). The steady-state mRNA levels of MMP-3, -7, -9, and -12 in isografts and allografts were greater than those of normal tracheas at all time points (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Temporal changes in MMP-3, MMP-9, MMP-12, and MMP-7 steady-state mRNA levels after tracheal transplantation. Mean values (± SE) for the signal intensity for MMP-3 (A), MMP-12 (B), MMP-9 (C), and MMP-7 (D) of normal tracheas (white column), isografts (gray column), and allografts (black column) expressed as arbitrary units (A.U.) after normalization to β-actin. Six normal tracheas, five isografts, and five allografts were analyzed at each time point. *P < 0.05; †P < 0.01 of allografts compared with isografts.

Expression of TIMP-1 Is Selectively Induced in Allografts Compared with Isografts after Heterotopic Tracheal Transplantation

The temporal profiles of expression for TIMP-1, -2, -3, and -4 were determined from total cellular RNA recovered from isografts, allografts, and normal tracheas. Our findings demonstrate the selective induction of TIMP-1 expression in allografts and TIMP-3 expression in isografts. In addition, we observed the selective suppression of TIMP-2 in allografts after transplantation. Steady-state mRNA levels for TIMP-1 were increased in isografts and allografts at Day 7 after transplantation (Figure 3A). However, by Day 14, mRNA levels for TIMP-1 remained elevated in allografts but decreased in isografts to the levels found in normal tracheas (Figure 3A). In contrast, steady-state levels of TIMP-3 mRNA were significantly elevated in isografts over allografts and normal tracheas at Days 14 and 28 after transplantation (Figure 3B). Furthermore, mRNA levels for TIMP-2 were decreased in allografts compared with isografts and normal tracheas at all time points (Figure 3C). TIMP-4 expression in allografts and isografts was undetectable at all time points (data not shown). Because expression of TIMP-1 was elevated in allografts compared with isografts after transplantation, we chose to further examine the contribution of TIMP-1 to the development of OAD.

Figure 3.

Temporal changes in TIMP-1, TIMP-2, and TIMP-3 steady-state mRNA levels after tracheal transplantation. Mean values (± SE) for the signal intensity for TIMP-1 (A), TIMP-3 (B), and TIMP-2 (C) of normal tracheas (white column), isografts (gray column), and allografts (black column) expressed as arbitrary units (A.U.) after normalization to β-actin. Six normal tracheas, five isografts, and five allografts were analyzed at each time point. *P < 0.05; †P < 0.01 of allografts compared with isografts.

To identify the location of TIMP-1 protein in the tracheal grafts, we performed immunohistochemistry on allografts, isografts, and normal tracheas. TIMP-1 was expressed in allografts and isografts in a temporally and spatially restricted manner. TIMP-1 protein was detected in flattened epithelial cells of allografts at Day 7 after transplantation (Figure 4A) but was rarely detected in cuboidal epithelial cells of isografts at this time point (Figure 4D). TIMP-1 protein was also found in mesenchymal cells in the tracheal submucosa and chondrocytes of the tracheal cartilage of allografts and, to a lesser extent, isografts. TIMP-1 immunostaining persisted within the flattened epithelial cells at Day 14 in the allografts and was detected in submucosal mesenchymal and inflammatory cells (Figure 4B). By Day 28, the allograft epithelium was no longer identifiable, and TIMP-1 protein was localized to mesenchymal and inflammatory cells within the tracheal lumen and submucosa (Figure 4C). Our findings demonstrate the early and persistent presence of TIMP-1 in the allograft during the development of OAD.

Figure 4.

Localization of TIMP-1 protein by immunohistochemistry in isografts, allografts, and normal trachea. (A) Tracheal allograft at Day 7 incubated with TIMP-1 antibody shows prominent TIMP-1 immunostaining of the flattened epithelium (arrow) along with fibroblasts in the submucosa and chondrocytes (bar = 50 μm; original magnification: ×400). (B) Allograft at Day 14 incubated with TIMP-1 antibody demonstrates strong TIMP-1 positivity in the metaplastic epithelium (arrow) (bar = 50 μm; original magnification: ×400). (C) Allograft at Day 28 stained with TIMP-1 antibody shows TIMP-1 immunostaining of inflammatory cells and fibroblasts in the submucosa and tracheal lumen (arrowheads) (bar = 50 μm; original magnification: ×400). (D) Tracheal isograft at Day 7 after transplantation incubated with antibody to murine TIMP-1 demonstrates faint TIMP-1 immunostaining (brown) of airway epithelial cells and infrequent staining of chondrocytes and fibroblasts in the submucosa (bar = 50 μm; original magnification: ×400). (E) Isograft at Day 14 after transplantation in- cubated with TIMP-1 antibody shows TIMP-1 immunostaining of fully differentiated ciliated epithelium (dashed arrow) (bar = 50 μm; original magnification: ×400). (F) Isograft at Day 28 after transplantation incubated with TIMP-1 antibody shows strong TIMP-1 immunostaining of the restored tracheal epithelium (dashed arrow) (bar = 50 μm; original magnification: ×400). (G) Normal trachea incubated with TIMP-1 antibody shows TIMP-1 protein localized to the intact tracheal epithelium (dashed arrow) (bar = 50 μm; original magnification: ×400). (H) Allograft at Day 14 incubated with isotype control antibody shows no background staining (bar = 50 μm; original magnification: ×400).

TIMP-1 protein was also detected in the regenerated and differentiated ciliated columnar epithelium of isografts at Days 14 and 28 after transplantation (Figures 4E and 4F). This pattern of TIMP-1 staining in the re-epithelialized isografts was similar to that seen in the normal trachea (Figure 4G).

TIMP-1 Deficiency Increases Re-epithelialization and Abrogates the Development of OAD after Heterotopic Tracheal Transplantation

To determine whether the development of OAD was altered in the absence of TIMP-1, we measured re-epithelialization and luminal obliteration in wild-type allografts transplanted into TIMP-1–deficient compared with wild-type recipients. Allografts transplanted into TIMP-1 −/− recipients did not develop OAD at Day 28 after transplantation, unlike those transplanted into wild-type mice (Figures 5A and 5B). By morphometry, allografts transplanted into TIMP-1 −/− recipients had less luminal obliteration compared with allografts transplanted into wild-type recipients (31% versus 94%, P < 0.05) (Figure 5C). Re-epithelialization was increased in allografts transplanted into TIMP-1 −/− recipients compared with those transplanted into wild-type recipients (45% versus 0%, P < 0.05) (Figure 5D). In addition, allografts implanted into TIMP-1 −/− recipients had less submucosal thickening and inflammatory cell infiltration compared with wild-type recipients at Day 28 (Figures 5A and 5B). We did not observe a significant difference in luminal obliteration or re-epithelialization in allografts from wild-type recipients versus allografts from TIMP-1–deficient recipients at Days 7 and 14. Wild-type isografts transplanted into TIMP-1 −/− recipients underwent re-epithelialization with pseudo-stratified, columnar epithelium and did not develop luminal obliteration after 28 d, similar to isografts in wild-type recipients (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Tracheal allografts recovered from TIMP-1–deficient recipients have decreased luminal obliteration and increased re-epithelialization at Day 28 after transplantation. (A) Wild-type allograft recovered from a TIMP-1 −/− recipient after 28 d shows epithelial cells covering large portions of the basement membrane (arrowhead) and minimal inflammation in the submucosa between the epithelium and cartilage (*) (H&E; bar = 50 μm; original magnification: ×200; insets ×20). (B) Wild-type allograft recovered from a wild-type recipient after 28 d demonstrates no identifiable epithelium, prominent inflammatory cells, and fibroblasts in the submucosa and luminal obliteration. The basement membrane (arrowhead) is pulled away from the cartilage (*) (H&E; bar = 50 μm; original magnification: ×200; insets ×20). (C) Morphometric analysis of luminal obliteration. Mean values (± SE) for percentage of luminal obliteration of wild-type allografts recovered from TIMP-1−/− (white column) and wild-type (black column) recipients at Day 28 after tracheal transplantation. Allografts from four TIMP-1 −/− and five wild-type recipients were analyzed. *P < 0.05. (D) Morphometric analysis of re-epithelialization. Mean values (± SE) for percentage of the tracheal lumen covered with epithelial cells for wild-type allografts recovered from TIMP-1−/− (white column) and wild-type (black column) recipients at Day 28 after tracheal transplantation. Allografts from four TIMP-1 −/− and five wild-type recipients were analyzed. *P < 0.05.

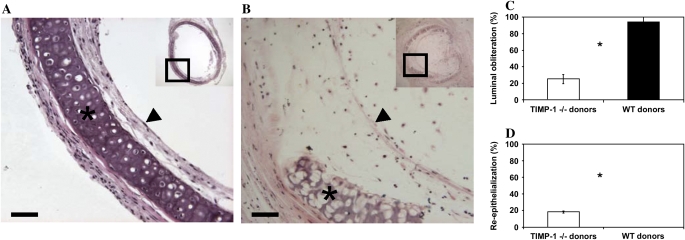

To determine whether TIMP-1 deficiency in the donor trachea affected the development of OAD, we transplanted TIMP-1 −/− allografts into wild-type recipients. In contrast to wild-type tracheas, TIMP-1 −/− allografts did not develop OAD at Day 28 after transplantation into wild-type recipients (Figures 6A and 6B). Morphometric analysis revealed that TIMP-1 −/− allografts had decreased luminal obliteration compared with wild-type allografts (25% versus 94%, P < 0.05) (Figure 6C). Additionally, re-epithelialization was increased in TIMP-1 −/− allografts compared with wild-type allografts transplanted into wild-type recipients (18% versus 0%, P < 0.05). TIMP-1 −/− allografts also lacked the submucosal thickening and inflammatory cell infiltration seen in wild-type tracheas at Day 28 (Figures 6A and 6B). We did not identify a significant difference in luminal obliteration or re-epithelialization in wild-type versus TIMP-1 −/− allografts recovered from wild-type recipients at Days 7 and 14. TIMP-1 −/− isografts underwent re-epithelialization with pseudo-stratified, columnar epithelium and did not develop luminal obliteration after 28 d, similar to wild-type isografts (data not shown). Our findings indicate that TIMP-1 deficiency in the allograft or the recipient facilitates epithelial repair and prevents luminal obliteration.

Figure 6.

TIMP-1 deficiency in donor tracheas decreased luminal obliteration and increased re-epithelialization of allografts at Day 28 after transplantation. (A) TIMP-1 −/− trachea recovered from wild-type recipient 28 d after allograft transplantation shows squamous epithelial cells covering the basement membrane (arrowhead) with minimal inflammation seen in the submucosa between the epithelium and cartilage (*) (H&E; bar = 50 μm; original magnification: ×200; insets ×20). (B) Wild-type trachea recovered from wild-type recipient 28 d after allograft transplantation shows no identifiable epithelium and inflammatory cell and fibroblast accumulation in the submucosa and lumen. The basement membrane (arrowhead) is pulled away from the cartilage (*) (H&E; bar = 50 μm; original magnification: ×200; insets ×20). (C) Morphometric analysis of luminal obliteration. Mean values (± SE) for percentage of luminal obliteration of TIMP-1−/− (white column) and wild-type (black column) tracheas recovered from wild-type recipients at Day 28 after transplantation. Four TIMP-1 −/− and five wild-type allografts were analyzed. *P < 0.05. (D) Morphometric analysis of re-epithelialization. Mean values (± SE) for percentage of the lumen covered with epithelial cells for TIMP-1−/− (white column) and wild-type (black column) tracheas recovered from wild-type recipients at Day 28 after transplantation. Four TIMP-1 −/− and five wild-type allografts were analyzed. *P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

The major goals of this study were to investigate the expression of MMPs and TIMPs in the heterotopic tracheal transplant model and to determine the role of TIMP-1 in the development of OAD. Our study is the first to provide direct evidence that TIMP-1 contributes significantly to the pathogenesis of OAD. We found that steady-state mRNA levels for MMP-3, MMP-9, and MMP-12 were selectively increased in the allograft. We demonstrated that TIMP-1 expression was induced in a temporally and spatially restricted manner in tracheal allografts and that increased expression of TIMP-1 correlated with the development of OAD. In contrast, the expression of TIMP-2 and TIMP-3 was markedly lower in tracheal allografts compared with isografts during the period of graft rejection. The decrease in luminal obliteration and mononuclear inflammatory cell accumulation and the increase in tracheal re-epithelialization in the absence of allograft or recipient TIMP-1 support the concept that TIMP-1 promotes the development of OAD. Furthermore, the detection of TIMP-1 in the epithelium of isografts at Days 14 and 28 after transplantation coincides with the regeneration of a mature mucociliary epithelium (5, 21). The pattern of TIMP-1 expression in the restored isografts was similar to that found in normal tracheas. These observations suggest that TIMP-1 may play a homeostatic role in the fully differentiated pseudo-stratified airway epithelium and may function to limit proteolysis by MMPs that may persist after the completion of epithelial repair.

Our results show the selective expression of MMPs in a temporally restricted manner after tracheal transplantation and suggest that these MMPs may make distinct contributions to the pathogenesis of OAD in heterotopic tracheal transplants. Our finding of increased MMP-9 expression in tracheal allografts at Day 14 is in agreement with the MMP-9 expression profile reported by Fernandez and colleagues (22). In that study, MMP-9 mRNA expression and enzymatic activity levels were increased at Days 10 and 20 of tracheal allograft rejection. Likewise, our observations of increased MMP-9 and TIMP-1 expression during the development of OAD in the heterotopic tracheal transplant model are consistent with those reported for BAL specimens of patients with BOS. Taghavi and colleagues demonstrated increased MMP-9 and TIMP-1 concentrations in the BAL recovered from patients with BOS compared with that recovered from lung transplant recipients who did not develop this complication (13).

TIMP-2 mRNA expression was decreased in the allograft compared with the isograft at Days 7, 14, and 28, whereas TIMP-3 mRNA expression was increased in the isograft compared with allografts at Days 14 and 28. This selective difference in expression in TIMP-2 and TIMP-3 mRNA may suggest a protective role of TIMP-2 and TIMP-3 in the heterotopic tracheal transplant. TIMP-3 may be protective in the tracheal graft by preventing the release of cell-surface–bound TNF-α, thus attenuating inflammation through the inhibition of a disintegrin and metalloproteinase–17, also known as TNF-α–converting enzyme (23, 24). TIMP-2 is interesting because it not only has the ability to inhibit MMPs in vitro but also is vital for the activation of MMP-2 (gelatinase A) in vivo (25). Heterotopic tracheal transplantation into MMP-2–deficient mice failed to demonstrate protection from or acceleration in the development of OAD (22). Therefore, we speculate that a protective role attributable to TIMP-2 would likely be due to MMP inhibition rather than increased MMP-2 activation.

Our histology results showed that TIMP-1 was expressed by mononuclear leukocytes, fibroblasts, chondrocytes, and airway epithelial cells in the tracheal allograft. These findings are consistent with previously published pulmonary sources of TIMP-1 (26–28). In our model, TIMP-1 was derived from donor and recipient sources. Our findings demonstrated that the elimination of TIMP-1 from the donor trachea or the allograft recipient was sufficient to prevent the development of OAD.

Inhibition of OAD development has also been observed in tracheal allografts recovered from recipients with targeted disruption of the MMP-9 gene. Heterotopic tracheal transplantation into MMP-9 −/− recipients produced less mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltration, epithelial damage, and luminal occlusion of the allografts compared with those transplanted into wild-type recipients (22). The abrogation of OAD in the absence of MMP-9 or its inhibitor, TIMP-1, presents a seeming paradox that suggests the underlying mechanisms are more complex than merely the stoichiometric inhibition of MMP activity.

The mechanism by which TIMP-1 deficiency protects the allograft from OAD has yet to be fully elucidated. Studies in the heterotopic tracheal transplant model have demonstrated that airway epithelial destruction is an important early event in the development of OAD (29–31). Airway epithelial repair is dependent on matrix metalloproteinases to enable epithelial cell spreading and migration over the denuded basement membrane. For example, MMP-7 is prominently expressed by damaged airway epithelial cells and is required for epithelial repair (32). MMP-9 is expressed in the advancing lamellipodia of migrating human bronchial epithelial cells and is postulated to regulate cell migration by remodeling the provisional ECM at contact points with the cell membrane (33). Increased expression of TIMP-1 could inhibit MMP activity required for airway epithelial repair in the tracheal allograft, thus contributing to the development of OAD. In support of this concept, overexpression of TIMP-1 in keratinocytes has been shown to interfere with cutaneous wound healing by retarding epithelial cell migration over the wound (34). In our study, TIMP-1 expression was selectively elevated in tracheal allografts compared with isografts during the second week after transplantation. Increased TIMP-1 expression coincides with the period of maximal epithelial cell proliferation in the allografts (5). Moreover, TIMP-1 protein localizes to the airway epithelium and submucosa in close proximity to damaged epithelial cells of the allografts. Thus, TIMP-1 is present at the appropriate time and location to interfere with airway epithelial repair and facilitate the development of OAD. We attribute the increase in TIMP-1 mRNA expression in the allograft at Day 14 after transplantation to increased expression by epithelial, mesenchymal, and inflammatory cells of the allograft. However, by Day 28, the allografts had lost most of their epithelium, which likely represents the loss of an important source of TIMP-1. We speculate that it is this loss of the allograft epithelium that accounts for much of the decrease in TIMP-1 mRNA observed at Day 28, despite the persistence of TIMP-1 protein in mesenchymal and inflammatory cells.

TIMP-1 deficiency in the donor or recipient led to increased re-epithelialization of the tracheal allograft. However, airway re-epithelialization in the allograft was incomplete and undifferentiated at Day 28 after transplantation compared with isograft controls, which have a completely restored mucociliary epithelium. A potential explanation for the observed difference may be that decreased, but not eliminated, TIMP-1 expression prevents full restoration of the epithelium. Despite incomplete epithelial repair, TIMP-1 deficiency in the donor or recipient was sufficient to prevent mesenchymal cell migration and ECM deposition in the lumen.

Another potential mechanism by which TIMP-1 deficiency may prevent OAD is through enhanced ECM degradation. However, increased proteolysis of ECM components alone would not account for the marked reduction in inflammatory and mesenchymal cell infiltration of the tracheal lumen and submucosa observed when TIMP-1 was absent from the allograft or recipient. It is now increasingly recognized that the biological functions of MMPs extend beyond ECM remodeling. Indeed, gelatinase B– deficient mice were protected from the development of OAD in the allograft potentially through the modulation of cytokines and chemokines (22). Furthermore, TIMP-1 deficiency did not attenuate lung or renal fibrosis in mouse models of injury (19, 35, 36). Thus, we feel that the protection from OAD observed in the heterotopic allografts of TIMP-1–deficient donors or recipients is mediated through more than just ECM degradation.

A third possible mechanism through which TIMP-1 deficiency may prevent the development of OAD is by modulating respiratory epithelium-specific homing signals. Bronchial epithelial cells express E-cadherin, which binds the integrin αEβ7 (CD103) present on 90% of CD8+ lymphocytes and 40% of CD4+ lymphocytes (37). Thus, airway epithelial cell E-cadherin may affect allospecific T-cell homing through engagement of αEβ7 integrin. MMP-7 has been shown to mediate E-cadherin shedding from the surface of airway epithelial cells and through this mechanism could potentially suppress lymphocyte accumulation in the allograft (38). TIMP-1 deficiency in the allograft could enhance proteolytic cleavage of E-cadherin to downregulate allospecific T-lymphocyte homing to the airway epithelium.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that TIMP-1 is differentially expressed between tracheal isografts and allografts in a spatially and temporally restricted manner after heterotopic transplantation. Furthermore, TIMP-1 deficiency in the donor or the recipient is sufficient to prevent OAD at 28 d after transplantation. Our findings provide direct evidence that TIMP-1 plays an important role in the development of OAD in the heterotopic tracheal transplant model and suggest a potential role for this proteinase inhibitor in the pathogenesis of OB in patients with lung transplant.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Paul D. Soloway for providing the TIMP-1 −/− mice and Drs. William C. Parks and Joan G. Clark for their helpful discussions. They also thank Lisa McLemore for excellent technical assistance.

This study was supported by an American Lung Association of Washington Research Training Fellowship grant (P.C.) and grants HL63994 (D.K.M.) and HL079756 (P.C.) from the National Institutes of Health.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0344OC on December 30, 2005

Conflict of Interest Statement: None of the authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Trulock EP, Edwards LB, Taylor DO, Boucek MM, Berkeley MK, Hertz MI. Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: twenty-second official adult lung and heart-lung transplant report-2005. J Heart Lung Transplant 2005;24:956–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Estenne M, Hertz M. Bronchiolitis obliterans after human lung transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;166:440–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boehler A, Kesten S, Weder W, Speich R. Bronchiolitis obliterans after lung transplantation. Chest 1998;114:1411–1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Estenne M, Maurer JR, Boehler A, Egan JJ, Frost A, Hertz M, Mallory GB, Snell GI, Yousem S. Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome 2001: an update of the diagnostic criteria. J Heart Lung Transplant 2001;21:297–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neuringer IP, Aris RM, Burns KA, Bartolotta TL, Chalermskulrat W, Randell SH. Epithelial kinetics in mouse heterotopic tracheal allografts. Am J Transplant 2002;2:410–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hele DJ, Yacoub MH, Belvisi MG. The heterotopic tracheal allograft as an animal model of obliterative bronchiolitis. Respir Res 2001;2:169–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hertz MI, Jessurun J, King MB, Savik SJ, Murray JJ. Reproduction of the obliterative bronchiolitis lesion after heterotopic transplantation of mouse airways. Am J Pathol 1993;142:1945–1951. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parks WC, Wilson CL, Lopez-Boado YS. Matrix metalloproteinases as modulators of inflammation and innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 2004;4:617–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parks WC, Shapiro SD. Matrix metalloproteinases in lung biology. Respir Res 2001;2:10–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagase H, Woessner JF Jr. Matrix metalloproteinases. J Biol Chem 1999;274:21491–21494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lambert E, Dassé E, Haye B, Petitfrère E. TIMPs as multifacial proteins. Clin Rev Oncol Hematol 2004;49:187–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brazelton TR, Adams B, Shorthouse R, Morris RE. Chronic rejection: the result of uncontrolled remodeling of graft tissue by recipient mesenchymal cells? Data from two rodent models and the effects of immunosuppressive therapies. Inflamm Res 1999;48:S134–S135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taghavi S, Krenn K, Jaksch P, Klepetko W, Aharinejad S. Broncho-alveolar lavage matrix metalloproteases as a sensitive measure of bronchiolitis obliterans. Am J Transplant 2005;5:1548–1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hubner RH, Meffert S, Mundt U, Bottcher H, Freitag S, El Mokhtari NE, Pufe T, Hirt S, Folsch UR, Bewig B. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 in bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after lung transplantation. Eur Respir J 2005;25:494–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trello CA, Williams DA, Keller CA, Crim C, Webster RO, Ohar JA. Increased gelatinolytic activity in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid in stable lung transplant recipients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997;156:1978–1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eerola LM, Alho HS, Maasilta PK, Inkinen KA, Harjula AL, Litmanen SH, Salminen US. Matrix metalloproteinase induction in post-transplant obliterative bronchiolitis. J Heart Lung Transplant 2005;24:426–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beeh KM, Beier J, Kornmann O, Micke P, Buhl R. Sputum levels of metalloproteinase-9 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1, and their ratio correlate with airway obstruction in lung transplant recipients: relation to tumor necrosis factor-a and interleukin-10. J Heart Lung Transplant 2001;20:1144–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soloway PD, Alexander CM, Werb Z, Jaenisch R. Targeted mutagenesis of TIMP-1 reveals that lung tumor invasion is influenced by TIMP-1 genotype of the tumor but not by that of the host. Oncogene 1996;13:2307–2314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim KH, Burkhart K, Chen P, Frevert CW, Randolph-Habecker J, Hackman RC, Soloway PD, Madtes DK. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase–1 deficiency amplifies acute lung injury in bleomycin exposed mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2005;33:271–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boehler A, Chamberlain D, Kesten S, Slutsky AS, Mingyao L, Keshavjee S. Lymphocytic airway infiltration as a precursor to fibrous obliteration in a rat model of bronchiolitis obliterans. Transplantation 1997;64:311–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Genden EM, Iskander A, Bromberg JS, Mayer L. The kinetics and pattern of tracheal allograft re-epithelialization. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2003;28:673–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fernández FG, Campbell LG, Liu W, Shipley JM, Itohara S, Patterson GA, Senior RM, Mohanakumar T, Jaramillo A. Inhibition of obliterative airway disease development in murine tracheal allografts by matrix metalloproteinase-9 deficiency. Am J Transplant 2005;5:671–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mohammed FF, Smookler DS, Taylor SE, Fingleton B, Kassiri Z, Sanchez OH, English JL, Matrisian LM, Au B, Yeh WC, et al. Abnormal TNF activity in TIMP-3 −/− mice leads to chronic hepatic inflammation and failure of liver regeneration. Nat Genet 2004;36:969–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Federici M, Hribal ML, Manghini R, Kanno H, Marchetti V, Porzio O, Sunnarborg SW, Rizza S, Serino M, Cunsolo V, et al. TIMP3 deficiency in insulin receptor-haploinsufficient mice promotes diabetes and vascular inflammation via increased TNF- a. J Clin Invest 2005;115:3494–3505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Z, Juttermann R, Soloway PD. TIMP-2 is required for efficient activation of proMMP-2 in vivo. J Biol Chem 2000;275:26411–26415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yao PM, Maitre B, Delacourt C, Buhler JM, Harf A, Lafuma C. Divergent regulation of 92-kDa gelatinase and TIMP-1 by HBECs in response to IL-1b and TNF-a. Am J Physiol 1997;273:L866–L874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou X, Trudeau JB, Schoonover KJ, Lundin JI, Barnes SM, Cundall MJ, Wenzel SE. Interleukin-13 augments transforming growth factor-beta1-induced tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 expression in primary human airway fibroblasts. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2005;288:c435–c442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferrari-Lacraz S, Nicod LP, Chicheportiche R, Welgus HG, Dayer J-M. Human lung tissue macrophages, but no alveolar macrophages, express matrix metalloproteinases after direct contact with activated T lymphocytes. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2001;24:442–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.King MB, Pedtke AC, Levrey-Hadden HL, Hertz MI. Obliterative airway disease progresses in heterotopic airway allografts without persistent alloimmune stimulus. Transplantation 2002;74:557–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fernández FG, Jaramillo A, Chen C, Liu DZ, Tung T, Patterson GA, Mohanakumar T. Airway epithelium is the primary target of allograft rejection in murine obliterative airway disease. Am J Transplant 2004;4:319–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adams B, Brazelton T, Berry G, Morris R. The role of respiratory epithelium in a rat model of obliterative airway disease. Transplantation 2000;69:661–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dunsmore SE, Saarialho-Kere UK, Roby JD, Wilson CL, Matrisian LM, Welgus HG, Parks WC. Matrilysin expression and function in airway epithelium. J Clin Invest 1998;102:1321–1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Legrand C, Gilles C, Zahm JM, Polette M, Buisson AC, Kaplan H, Birembaut P, Tournier JM. Airway epithelial cell migration dynamics: MMP-9 role in cell-extracellular matrix remodeling. J Cell Biol 1999;2:517–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Salonurmi T, Parikka M, Kontusaari S, Pirila E, Munault C, Salo T, Tryggvason K. Overexpression of TIMP-1 under the MMP-9 promoter interferes with wound healing in transgenic mice. Cell Tissue Res 2004;315:27–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eddy AA, Kim H, López-Guisa J, Oda T, Soloway PD, Wing D. Interstitial fibrosis in mice with overload proteinuria: deficiency of TIMP-1 is not protective. Kidney Int 2000;58:618–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim H, Oda T, López-Guisa J, Wing D, Edwards DR, Soloway PD, Eddy AA. TIMP-1 deficiency does not attenuate interstitial fibrosis in obstructive nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 2001;12:736–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Agace WW, Higgins JM, Sadasivan B, Brenner MB, Parker CM. T-lymphocyte-epithelial-cell interactions: integrin alpha(E)(CD103)beta(7), LEEP-CAM and chemokines. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2000;12:563–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McGuire JK, Li Q, Parks WC. Matrilysin (matrix metalloproteinase-7) mediates E-cadherin ectodomain shedding in injured lung epithelium. Am J Pathol 2003;162:1831–1843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]