Abstract

Obstructive lung diseases are often characterized by heterogeneous patterns of bronchoconstriction, although specific relationships between structural heterogeneity and lung function have yet to be established. We measured respiratory input impedance (Zrs) in eight anesthetized dogs using broadband forced oscillations at baseline and during intravenous methacholine (MCh) infusion. We also obtained high-resolution computed tomographic (HRCT) scans in 4 dogs and identified 20–30 individual airway segments in each animal. The Zrs spectra and HRCT images were obtained before and 5 min following a deep inspiration (DI) to 35 cmH2O. Each Zrs spectrum was fitted with two different models of the respiratory system: 1) a lumped airways model consisting of a single airway compartment, and 2) a distributed airways model incorporating a continuous distribution of airway resistances. For the latter, we found that the mean level and spread of airway resistances increased with MCh dose. Whereas a DI had no effect on average airway resistance during MCh infusion, it did increase the level of airway heterogeneity. At baseline and low-to-moderate doses of MCh, the lumped airways model was statistically more appropriate to describe Zrs in the majority of dogs. At the highest doses of MCh, the distributed airways model provided a superior fit in half of the dogs. There was a significant correlation between heterogeneity assessed with inverse modeling and the standard deviation of airway diameters obtained from HRCT. These data demonstrate that increases in airway heterogeneity as assessed with forced oscillations and inverse modeling can be linked to specific structural alterations in airway diameters.

Keywords: resistance, elastance, parameter estimation, Akaike criterion, canine, methacholine

the mechanical input impedance of the respiratory system (Zrs) has been demonstrated to be quite sensitive to parallel time constant heterogeneity in the lungs (19, 27, 36), specifically with regard to alterations in the frequency dependence of respiratory system resistance (Rrs) and elastance (Ers) (20, 25, 26). Often inverse modeling is applied to such Zrs spectra, in which the parameters of a specified lumped-element topology are estimated from the best-fit prediction to the actual data (2, 4). Ideally, the values of these parameters should correspond to actual physical properties of the respiratory system, such as airway resistance or tissue elastance. One particular inverse model that has been widely used to characterize Zrs data, regardless of pathology, has been the so-called “constant-phase” model described by Hantos et al. (16): a single compartment, viscoelastic structure that allows for the partitioning of airway and tissue resistances (20, 21). However, during bronchoconstriction, a heterogeneous distribution of parallel airway resistances may lead to biased model-based estimates of such airway and tissue properties (21, 28). Recently, several investigators have applied distributed inverse models to Zrs in an effort to quantify and compensate for such heterogeneity, reducing the estimation bias of airway and tissue properties (18, 19, 23, 39, 47). However, in cases of induced or spontaneous bronchoconstriction, it is unclear how widely distributed airway diameters should be before heterogeneity can adequately be assessed with such a distributed modeling approach. Such information would be important to evaluate, since heterogeneity has implications both for the work of breathing as well as the distribution of ventilation.

In addition, deep inspirations (DIs) have been shown to alter the dynamic mechanical equilibrium between opposing airway and tissue forces, leading to changes in the overall level of airway resistance. Nonetheless, it is unclear whether a DI has any sustained impact on the distribution of airway diameters during bronchoconstriction.

The goal of this study was to determine the sensitivity of detecting heterogeneous airway constriction in dogs using inverse modeling applied to Zrs measured during different infusion rates of a bronchonstricting agonist, and whether such functional changes in lung mechanics could be linked to specific structural alterations in airway diameter as assessed with high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT). In addition, we assessed whether a deep inspiration (DI) had any impact on changes in airway resistance or the heterogeneity of bronchoconstriction. The specific aims of this study were: 1) to measure Zrs in dogs at baseline and during the infusion of intravenous methacholine (MCh), 2) to determine the sensitivity of detecting the heterogeneity of airway constriction from Zrs using inverse modeling and HRCT, and 3) to determine the impact of DI on airway and respiratory tissue mechanics during induced bronchoconstriction.

METHODS

Animal preparation and protocol.

The protocol was approved by the Johns Hopkins Animal Care and Use Committee (Baltimore, MD) to ensure humane treatment of animals. Measurements were made in eight mongrel dogs weighing between 20 and 25 kg. Following placement of a peripheral intravenous line, each dog was anesthetized with intravenous thiopental (15 mg/kg induction dose followed by 10 mg·hr−1·kg−1 maintenance infusion) and paralyzed with 0.5 mg/kg succinylcholine with supplemental doses as required before measurements of respiratory impedance (see below). Each dog was orally intubated with an endotracheal tube (8.0- to 10.0-mm ID), and mechanically ventilated (Harvard Apparatus, Millis, MA) with a rate of ∼20 breaths/min and tidal volume of ∼15 ml/kg, titrated to achieve an end-tidal CO2 level of 30–40 Torr.

Forced oscillatory measurements of Zrs were obtained in each dog at a mean airway pressure of 10 cmH2O under baseline conditions and during continuous intravenous MCh infusion rates of 17, 67, and 200 μg/min (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO). For each condition, Zrs was measured immediately before and 5 min following a DI to 35 cmH2O sustained for 5 s. The Zrs was obtained using a custom-built servo-controlled pneumatic pressure oscillator (22) whose input driving signal consisted of nine sinusoids from 0.078 to 8.9 Hz arranged in a nonsum nondifference pattern (38). This signal was periodic over 25.6 s, and it was repeated four to five times such that each Zrs measurement lasted ∼2 min. The amplitude of the driving signal was adjusted to yield peak-to-peak pressures of 2–3 cmH2O. The resulting tracheal pressure waveform was measured with a variable reluctance transducer (LCVR 0–50 cmH2O, Celesco, Canoga Park, CA) connected to a small polyethylene catheter inserted into the endotracheal tube and allowed to extend ∼2 cm into the trachea (35). Airway flow was obtained with a screen pneumotachograph (model 4700A, Hans Rudolph, Kansas City, MO) coupled to another pressure transducer (LCVR 0–2 cmH2O, Celesco). Both pressure and flow signals were low-pass filtered at 10 Hz and sampled at 40 Hz by an analog-to-digital converter (model DT-2811, Data Translations, Marlborough, MA) for subsequent processing. Following the final dose of MCh, a 0.2 mg/kg intravenous atropine bolus was administered to block vagal tone in each dog and maximally dilate the airways, and a final Zrs measurement was obtained.

HRCT imaging of airways.

In four dogs (including an additional dog for which we did not have post-atropine Zrs measurements), we also obtained HRCT scans using a Sensation-16 scanner (Siemens, Iselin, NJ) immediately before each Zrs measurement. Images were obtained using a spiral mode during an 8-s period of apnea at 137 kVp and 165 mA. The computed tomography images were reconstructed with 1 mm slice thickness and a 512 × 512 matrix using 175-mm field at a window level of −450 Hounsfield units (HU) and window width of 1,350 HU. For each dog, we identified between 20 and 30 individual airway segments with 2–4 separate airway diameter measurements per segment, for a total of 36–124 diameters per dog. The cross-sectional area and diameter (Dn) was determined using the airway analysis model of the Volumetric Image and Display Analysis software package (Department of Radiology, Division of Physiological Imaging, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA). We made repeated measurements of airway size in a given dog for each dose and condition at approximately the same anatomic cross sections using adjacent anatomic landmarks, such as airway and vascular branch points. For each condition and MCh dose in the dog, we defined an average diameter for all airways identified, but we expressed these in terms of inverse diameters to the fourth power for the purposes of correlating them with the mean resistance as determined from the inverse modeling described below:

|

(1) |

where N is the number of discrete airway diameters identified. In addition, we also determined the standard deviation of airway diameters raised to the inverse fourth power

|

(2) |

Signal processing and inverse model analysis.

Zrs was computed from the sampled oscillatory pressure and flow waveforms using a Welch overlap-average periodogram technique with a 25.6-s rectangular window and 80% overlap (21). After neglecting the first 500 points in the data record (∼12.5 s) to minimize the influence of transient responses, between 12 and 20 overlapping windows were used to calculate Zrs for each animal. Total respiratory system resistance Rrs was determined from the real part of Zrs: Rrs = Re{Zrs}. The effective Ers was calculated from the imaginary part: Ers = −ωkIm{Ẑrs}, where ωk is the angular frequency of oscillation.

The mechanical properties of the respiratory system were assessed by fitting two different model topologies to each Zrs spectrum. Topology A was the well-known constant-phase model which has been used extensively to describe the oscillatory mechanics of the lungs and total respiratory system (3, 4, 16, 20, 21, 30). This model consists of a single, homogeneous, lumped airway compartment, with parameters for airway resistance (R) and inertance (I), in series with a tissue compartment with parameters for tissue damping (G) and elastance (H). The model has a predicted impedance (Ẑrs) as a function of frequency (ω) given by:

|

(3) |

where j is the unit imaginary number and α = (2/π)tan−1(H/G). Tissue hysteresivity, defined as the ratio of energy dissipation to energy storage across the respiratory tissues (13), can be determined as η = G/H for this model. However, since this topology assumes that the airway and tissue mechanical properties are homogeneously and uniformly distributed throughout the lungs, it may yield in artifactually high values for G and η when applied to Zrs during heterogeneous bronchoconstriction (20, 21, 28, 30).

Our second topology (B) was the distributed airways model originally described by Suki et al. (39) to provide a more accurate partitioning of airway and lung tissue resistances in the presence of heterogeneous bronchoconstriction. This model assumes that the respiratory system can be described by an arbitrary number of parallel branches, each consisting of identical G and H tissue parameters but unique airway resistance values. The values of these airway resistances vary from branch-to-branch in a probabilistic manner according to a predefined probability density function P(R) with upper and lower bounds Rmax and Rmin, respectively. The for this model can thus be expressed in terms of the five parameters Rmin, Rmax, I, G, and H:

|

(4) |

In contrast to the homogeneous Topology A, this topology may allow for a more accurate estimation of G and η during heterogeneous bronchoconstriction (39), albeit at the expense of an additional parameter (23). Given a specified distribution function P(R), an “effective” airway resistance can be determined from its mean value:

|

(5) |

while the heterogeneity of airway resistances can be determined from the standard deviation of P(R):

|

(6) |

Based on this mean (Rμ) and standard deviation (Rσ), we can determine the coefficient of variation in the airway distribution function as Rcv = Rμ/ Rσ.

Inverse model comparison.

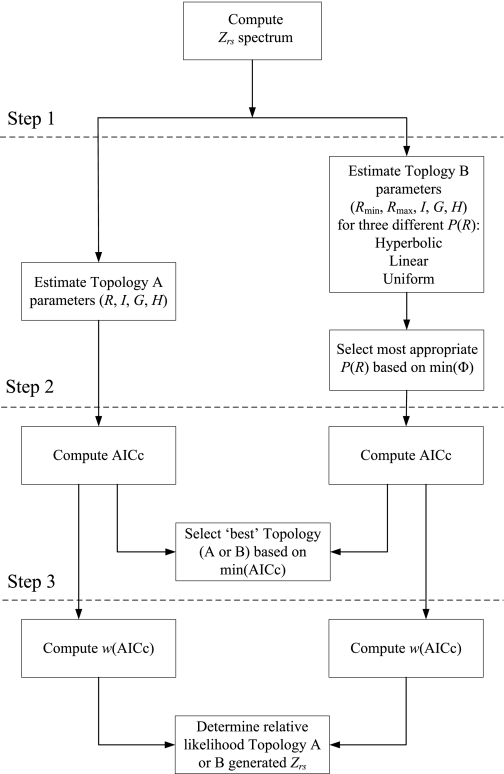

A flow diagram illustrating the steps used for comparing the relative appropriateness of either the homogeneous airways model (Topology A) or distributed airways model (Topology B) for describing each Zrs spectrum is shown in Fig. 1. First, the parameters for both topologies were simultaneously estimated using a nonlinear gradient technique (Matlab v7.0, The Mathworks, Natick, MA) that minimized the performance index Φ:

|

(7) |

where K is the number of distinct frequencies used in the excitation waveform (Step 1). For Topology B, we performed three separate estimations of its five parameters using three different forms of the airway distribution function P(R): hyperbolic, uniform, and linear (19, 23, 39). These particular forms of P(R) were selected based on their mathematical simplicity as well as their ability to yield a closed-form expression for the model predicted impedance described by Eq. 4 (39). In the case of Topology B, if the gradient search algorithm converged to a unique solution for two or more airway distribution functions, the most appropriate P(R) for a given Zrs spectrum was established based on the minimum Φ.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart illustrating process for parameter estimations and model comparisons for Topologies A and B. Zrs, respiratory input impedance; R, airway resistance parameter for Topology A; I, airway inertance; G, tissue damping; H, tissue elastance; Rmin, Rmax, minimum and maximum airway resistance parameters for Topology B, respectively; P(R), probability density function; min(Φ), minimum model fitting performance index; AICc, corrected Akaike Information Criterion; R, airway resistance; min(AICc), minimum AICc; w(AICc), Akaike weight.

Next, the relative appropriateness of using either Topology A or (the best form of) Topology B to describe the given Zrs spectrum was compared using the corrected Akaike Information Criterion (AICc) (1, 33), as determined from the respective Φ values obtained for both model fits (Step 2). The model with the lowest (i.e., most negative) AICc score was assumed to be the most likely topology to have generated the data (23). Finally, we computed the relative likelihood that either Topology A or B generated the Zrs data by computing the Akaike weight [w(AICc)] (23, 45), which can be interpreted as the probability that the model in question generated the Zrs data (Step 3). Thus for each Zrs spectrum fitted, the sum of the w(AICc) values from Topologies A and B should be equal to 1.

To determine whether the use of a statistically less appropriate model to describe a given Zrs spectrum would lead to biased estimates of airway or tissue properties, we also inspected the correlations between the individual parameter estimates from each topology for all doses and conditions. For airway resistance comparisons, we correlated the R parameter from Topology A to the Rμ from Topology B.

Statistical analysis.

For each MCh dose level, a one-way ANOVA was used to compare the model parameters from both Topology A and the best form of Topology B, as well as the derived parameters Rμ, Rσ, and Rcv before and after DI (SAS v8.2, SAS Institute, Cary, NC). If significance was obtained with ANOVA, post hoc analysis was performed using the Tukey honestly significant difference criterion. At each condition, pre- and post-DI comparisons of all variables were made using two-tailed paired t-tests. Post-atropine values were compared with there corresponding pre- and post-DI values at baseline using paired t-tests. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

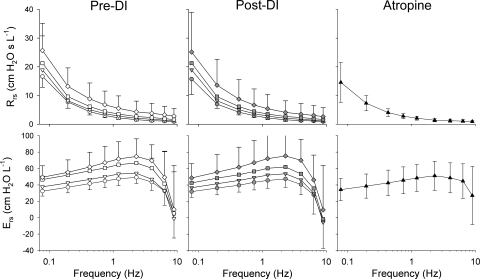

Figure 2 shows a summary of the Rrs and Ers spectra averaged across all eight dogs at baseline and at each of the three doses of MCh pre- and post-DI, as well as following administration of intravenous atropine. Under pre- and post-DI conditions, both Rrs and Ers increased at each frequency with increases in MCh dose. At the lowest frequencies, Rrs increased ∼50% during the highest dose of MCh compared with baseline, while Ers increased by ∼65%. There were no significant differences between the pre- and post-DI values of either Rrs or Ers at any MCh dose or frequency. Following administration of intravenous atropine, both Rrs and Ers decreased compared with their respective values at MCh dose of 200 μg/min, and they demonstrated no significant difference compared with their baseline values at any frequency.

Fig. 2.

Summary of respiratory resistance (Rrs) and elastance (Ers) from 0.078 to 8.9 Hz at baseline (circles) and intravenous MCh infusion rates of 17 (inverted triangles), 67 (squares), and 200 μg/min (diamonds) before (white) and 5 min following DI (gray). Data are also shown following intravenous atropine (black triangles). Error bars, where shown, denote SDs. DI, deep inspiration.

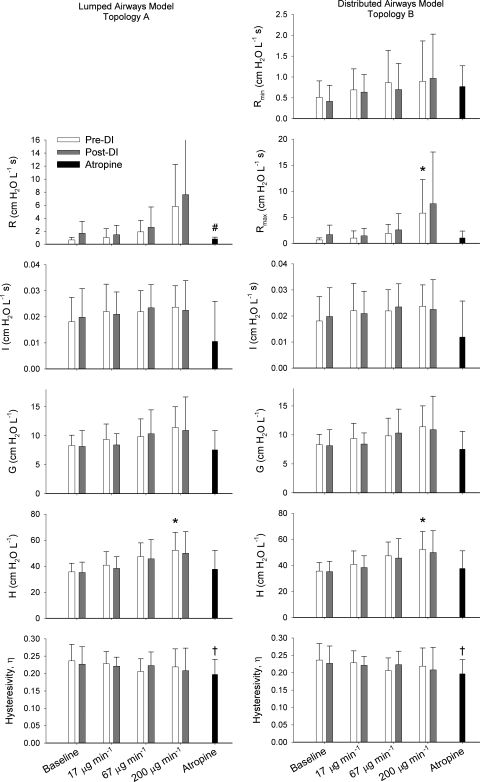

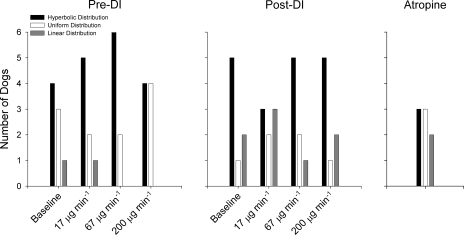

A summary of the estimated model parameters for both Topologies A and B is shown in Fig. 3, with the most appropriate distribution functions P(R) used for Topology B in Fig. 4. For Topology B, the hyperbolic distribution of airway resistances appeared to best describe Zrs for the majority of dogs pre- and post-DI at most MCh doses. Following administration of atropine, however, no airway distribution function outperformed the others. Both Topologies A and B detected significant increases in H with increased MCh dose pre-DI but not post-DI. For Topology B, Rmax significantly increased with increases in MCh dose. Topology A did demonstrate a trend of increasing R with MCh dose, but this did not achieve statistical significance pre- or post-DI. No significant change was observed for any model parameter between its pre- and post-DI values using paired t-tests. Following administration of atropine, R from Topology A was significantly lower than its pre-DI value at baseline. In addition, η was significantly lower than its pre-DI baseline value for both topologies.

Fig. 3.

Summary of parameter values for lumped airways model (Topology A) and distributed airways model (Topology B) averaged across all 8 dogs. Error bars denote SDs. η, Tissue hysteresivity. *Significantly higher compared with baseline value, P < 0.05 [using ANOVA and Tukey honestly significant difference under same condition (Pre-DI)]. †Significantly lower than pre- and post-DI values at baseline, P <0.05 (using paired t-test). #Significantly higher than pre-DI value, P < 0.05 (using paired t-test).

Fig. 4.

Summary of the airway resistance distributions obtained for Topology B for all 8 dogs at baseline and 3 doses of methacholine before and after DI. Data are also shown following intravenous administration of atropine.

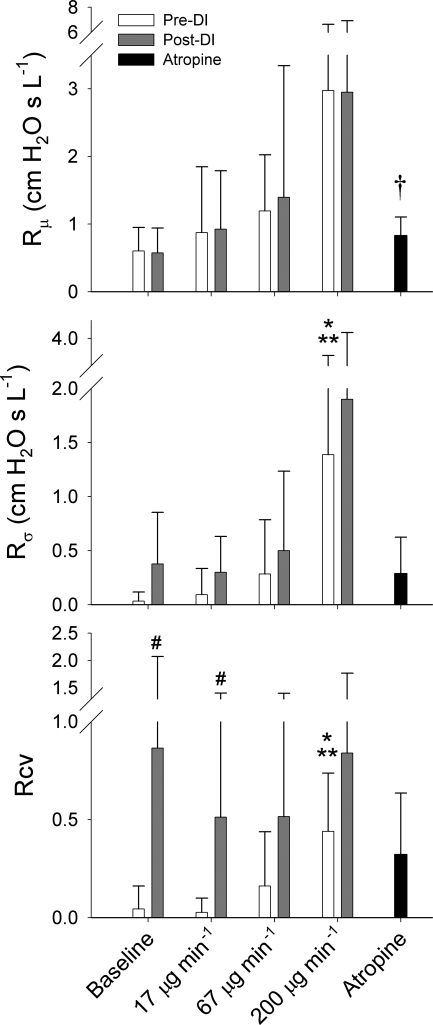

Figure 5 shows the summary of the Topology B-derived model parameters Rμ, Rσ, and Rcv at baseline and during MCh infusion pre- and post-DI, as well as following administration of atropine. While both Rμ and Rσ demonstrated an increasing trend with MCh dose, ANOVA only detected a significant dependence of the heterogeneity index Rσ on MCh dose pre-DI, with its value at 200 μg/min being significantly higher than its values at baseline and 17 μg/min using Tukey honestly significant difference. The pre-DI values of Rcv also demonstrated a significant dependence on MCh dose, also with significant pairwise differences between 200 μg/min compared with baseline and 17 μg/min. There was a considerable increase in the intersubject variability for Rcv post-DI, and a significant difference between its pre- and post-DI values at 17 μg/min.

Fig. 5.

Summary of derived airway parameter values for distributed airways model (Topology B) averaged across all 8 dogs. Error bars denote SDs. Rμ, mean airway resistance; Rσ, SD of airway resistances; Rcv, coefficient of variation for airway resistance. *Significantly higher than pre-DI value at baseline, P < 0.05 (using ANOVA and Tukey honestly significant difference). **Significantly higher than pre-DI value at methacholine dose of 17 μg/min, P < 0.05 (using ANOVA and Tukey honestly significant difference). †Significantly higher than pre-DI value at baseline, P < 0.05 (using paired t-test). #Significantly higher than pre-DI value at same methacholine dose, P < 0.05 (using paired t-test).

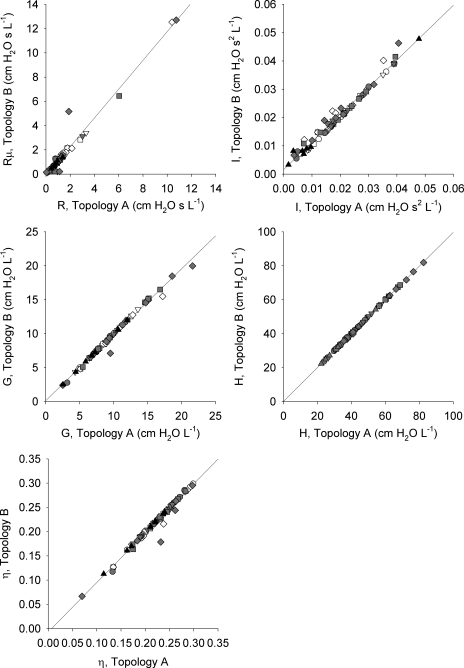

The correlations between the individual model parameter estimates for Topologies A and B for the individual dogs under all doses and conditions are shown in Fig. 6. In all cases, the airway and tissue parameter estimates were nearly identical, with regression lines indistinguishable from the lines of identity.

Fig. 6.

Correlations between parameter estimates obtained from Topology A (lumped airways model) and Topology B (distributed airways model). Data are shown for all 8 dogs at baseline (circles) and intravenous MCh infusion rates of 17 (inverted triangles), 67 (squares), and 200 μg/min (diamonds) before (white) and 5 min following DI (gray). Data are also shown following intravenous atropine (black triangles). In all plots, actual regression lines demonstrated no significant differences from the corresponding lines of identity.

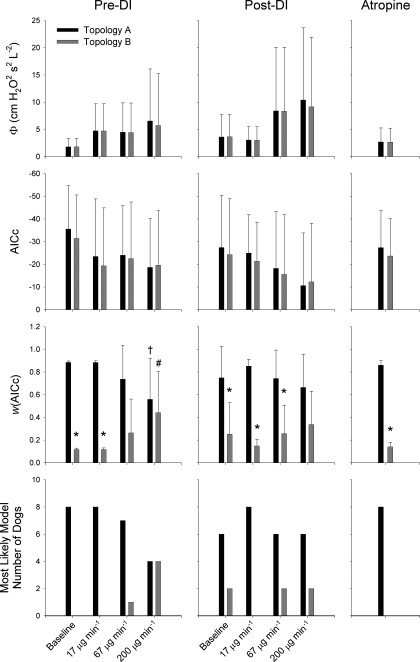

Figure 7 shows a summary of the values of Φ, AICc, and w(AICc) for Topologies A and B at each dose of MCh pre- and post-DI, as well as following administration of atropine. In addition, we also show the number of dogs for which either Topology A or B best described their Zrs spectra under all conditions and doses. Both topologies demonstrated trends of increasing Φ and AICc with MCh dose, although this did not achieve significance by ANOVA. Pre-DI values of w(AICc) for both Topologies were significantly dependent on MCh dose under pre-DI conditions but not post-DI. Pre-DI, nearly all dogs were best characterized by homogeneous airways model of Topology A under baseline conditions and at MCh doses of 17 and 67 μg/min. However, at the highest doses of MCh, half of the dogs were better described by the distributed airways model of Topology B. Under post-DI conditions, only two dogs were better characterized by Topology B at baseline and during MCh infusion rates of 67 and 200 μg/min. Following administration of atropine, all dogs were best described by Topology A.

Fig. 7.

Summary of Φ, AICc, and w(AICc) for Topologies A (black) and B (gray) before and after DI at each methacholine dose as well as following administration of intravenous atropine. Error bars, where shown, denote SDs. *Significantly lower that pre-DI value at same MCh dose, P < 0.05 (using paired t-test). †Significantly lower than corresponding values at baseline and MCh dose of 17 μg/min, P < 0.05 (using ANOVA and Tukey honestly significant difference). #Significantly higher than corresponding values at baseline and methacholine dose of 17 μg/min, P < 0.05 (using ANOVA and Tukey honestly significant difference).

Figure 8 shows the correlations between the mean and standard deviations of the airway diameters measured by HRCT with the Rμ and Rσ parameters from the distributed airways model for both a representative dog as well as averaged across the four dogs for which scans were obtained. While there was much intersubject variability, we found that the relationship between the airway diameters and model parameters was best described by the two-parameter regression equation y = a(1 − e−bx). Using this relationship, we found statistically significant (albeit nonlinear) correlations between the airway diameters and inverse model parameters.

Fig. 8.

Correlations between the airway diameters measured with high-resolution computed tomography (Eqs. 1 and 2) and derived airway resistance parameters from Topology B (Eqs. 5 and 6) for a representative dog (left) and averaged across four dogs (right). Data were obtained at baseline (circles) and intravenous MCh infusion rates of 17 (inverted triangles), 67 (squares), and 200 μg/min (diamonds) before (white) and 5 min following DI (gray). Dashed line represents rising exponential regression equation y = a(1 − e−bx). Data for representative dog is not included in Figs. 2–7 due to lack of atropine data. D̄ (D−4): mean of HRCT airway diameters to the inverse fourth power; S.D. (D−4), standard deviation of HRCT airway diameters to the inverse fourth power; Rμ, average airway resistance parameter from Topology B; Rσ, standard deviation of airway resistances from Topology B.

DISCUSSION

This study has demonstrated that functional alterations in lung mechanics assessed with forced oscillations, can be linked to structural changes in the pattern of airway constriction obtained from HRCT. Under induced bronchoconstriction, heterogeneity in the distribution of airway diameters may arise from differences in the pharmacological responsiveness of smooth muscle among the various airway segments (7, 8), or regional differences in perfusion-limited delivery of MCh due to heterogeneous bronchial blood flow (32).1 Exclusive of any increases in the effective airway resistance, heterogeneity in and of itself can cause substantial elevations in the resistive and elastic loads against which breathing occurs, which may exacerbate clinical symptoms in obstructive lung disease (29). Both modeling and imaging studies have shown that such heterogeneity results in significant alterations in ventilation distribution and gas exchange (15, 40, 41). In addition, ventilation heterogeneity has been strongly associated with airway hyperresponsiveness, raising questions as to its cause-and-effect relationship with reactive airway disease (44).

Using simple lumped-element models, both Otis et al. (36) and later Mead (31) demonstrated how parallel and serial time constant inhomogeneity can alter the frequency dependence of Zrs and its components, Rrs and Ers. Subsequent studies using more complicated anatomic computational models provided direct evidence as to how specific patterns and distributions of heterogeneous bronchoconstriction alter the frequency dependence of Rrs and Ers (11, 14, 25, 29, 43). More recent studies combining positron emission tomography imaging with forced oscillations in humans have elucidated a more definitive relationship between changes in Zrs and heterogeneous bronchoconstriction (40–42). The present study builds on this earlier work in that it seeks to establish whether quantifiable information on airway heterogeneity can be extracted from Zrs measured during pharmacologically induced bronchoconstriction, and whether such information is associated with anatomic changes in airway diameters obtained from HRCT.

It has been well established that changes in the frequency dependence of Zrs and its resistive (Rrs) and elastic components (Ers) can be indicative of both the pattern and locus of airway constriction (20). Morphometric modeling studies have indicted that in the presence of severe homogeneous peripheral airway constriction, Rrs will tend to increase uniformly at all frequencies. The Ers will demonstrate minimal change below 1 Hz but pronounced elevations at higher frequencies as a result of high-frequency oscillatory flow shunting into the central airway walls (25, 31). In the presence of central airway constriction, Rrs will demonstrate a mild uniform increases at all frequencies, regardless of the distribution of airway diameters, whereas Ers will be minimally affected. However, if central airway constriction includes mild peripheral airway constriction and airway closure, Ers can be affected at all frequencies (25). Thus our Zrs data in Fig.2 are most consistent with a combination of predominately central airway constriction and mild peripheral involvement.

To assess the sensitivity of using Zrs to detect the heterogeneity of airway constriction, we compared the performances of two different viscoelastic constant-phase models: 1) a “lumped” airways model in which the resistive and inertial properties of the airways is represented by individual R and I parameters; and 2) a “distributed” airways model in which airway resistance is assumed to be heterogeneously distributed according to a predefined probability density function, P(R). Both topologies were applied to the mechanical impedance spectra of the total respiratory system. Thus the parameters characterizing tissue mechanics are influenced by both the lung parenchymal tissues and the chest wall. Thus, the parameters characterizing airway resistance may in fact be biased due to the purely Newtonian and volume-dependent component of chest wall resistance. However, because our Zrs measurements were made at a constant mean airway pressure and (presumably) constant lung volume, we have assumed that the trends observed in our data are due solely to changes in the distribution of airway diameters (5), because MCh should have minimal influence on chest wall resistance.

Both models were able to detect alterations in airway and tissue mechanics with remarkable consistency, as we found no significant difference between estimates of the parameter values from either the lumped airway model or the distributed airways model (Fig. 5). This suggests that the R parameter of the traditional single-compartment constant-phase model can provide a reliable estimate of overall or average airway resistance, even during severe bronchoconstriction. Moreover, little-to-no estimation bias of the tissue properties was introduced when applying this model to data during intravenous MCh infusion (Fig. 6). This is in contrast to the findings of Suki et al. (39), who found a slight improvement in estimates of tissue resistance when using the model of Topology B compared with Topology A during simulated heterogeneous bronchoconstriction in a canine lung (39). This may be due to differences in the pattern of the heterogeneity of airway constriction in their theoretical model vs. our actual experimental conditions. We note, too, that aerosolized deliveries of bronchoconstricting agonists may result in a different heterogeneous pattern of airway constriction (34).

Both inverse model topologies also detected significant increases in tissue elastance H during MCh infusion (Fig. 3). While the tissue damping parameter G did demonstrate a tendency to increase with MCh dose (by ∼50% at the highest dose compared with baseline), this did not achieve statistical significance. These increases may reflect a stiffening of the parenchyma due to airway-tissue interdependence during bronchoconstriction, as suggested by the data of Mitzner et al. (32). Alternatively, increases in H (and G) may also be the result of a small number of closed airways randomly distributed throughout the airway tree, which effectively reduces the amount of lung tissue in communication with the airway opening. The fact that η, or the ratio of G to H, did not show any changes with MCh dose suggests that these dogs did experience progressive airway closure and derecruitment. Such derecruitment may alter the mean level and frequency dependence of Zrs, especially at low frequencies (25, 29). However, because we observed no significant pairwise differences in the pre- and post-DI tissue parameter values, we conclude that any benefits of DI were lost within the 5-min period between Zrs measurements (see below).

In this study, both models yielded consistent estimates of airway and tissue properties for all dogs under all conditions. Thus a relevant question may be which topology is most appropriate to describe Zrs data during induced bronchoconstriction. Topology A appears to be the statistically superior model for low-to-moderate doses of MCh based on Akaike criteria, an index derived from information theory to determine which model, in a maximum likelihood sense, is most appropriate to describe a given data set (1). However, statistical tests of model appropriateness, whether based on hypothesis testing paradigms (such as F tests) (20, 21) or maximum likelihood theory (1, 45), do not always indicate the utility of a particular model or the relevant physiological information it may provide (23). For example, Topology B has the advantage of providing information on the distribution of airway resistances, which is strongly correlated with the distribution of diameters obtained from randomly selected central airway segments measured with HRCT (Fig. 8). The fact that this relationship was nonlinear may indicate that Zrs is actually more sensitive to changes in airway resistance due to peripheral airway constriction, which HRCT will not detect (4, 41). Such information cannot be extracted from Zrs using Topology A, despite its apparent statistical superiority over Topology B.

This is not to suggest that formal statistical tests of model comparison are entirely without merit, because they may provide some insight into how strongly a physical mechanism influences a specified data set: in our case, the degree to which parallel airway heterogeneity influences Zrs. We used the technique of Akaike weights to determine the relative likelihood that the topology in question generated the Zrs data (45). Our results demonstrate that w(AICc) for the distributed airways model increases with increasing MCh dose under pre-DI conditions, suggesting that it becomes more appropriate (in a maximum likelihood sense) to characterize Zrs data during higher levels of bronchoconstriction compared with Topology A. Indeed, the relative likelihood that Topology B generated the data as assessed with w(AICc) progressively increased with MCh dose (Fig. 7). Moreover, the Zrs spectra for half of the dogs were best described by Topology B at the highest dose of MCh. This indicates that the spectral features of Zrs is not only influenced by heterogeneous bronchoconstriction, but the sensitivity of detecting airway heterogeneity from Zrs using inverse modeling is enhanced at higher MCh doses.

For the Topology B model fits, we limited our description of the parallel airway resistance distributions with only three different probability density functions: hyperbolic, uniform, or linear, with the most appropriate distribution for a given Zrs spectrum selected according to AICc comparisons (19, 23). These functions were used based on their mathematical simplicity and their ability to yield closed-form expressions for the predicted impedance of Eq. 4. Similar to the study of Suki et al. (39), we found that the hyperbolic distribution function was most appropriate to describe Zrs under the majority of conditions (Fig. 5). In reality, very little data exist as to how airway diameters are actually distributed in dogs at baseline or during induced bronchoconstriction (39), with diameters as measured by HRCT representing a gross undersampling of the actual population of airway segments (6, 7, 9). An additional limitation of Topology B is its assumption that all airway heterogeneity can be characterized by a parallel arrangement of conduits. In reality, the canine airway tree is a complex, asymmetric branching structure (17), and both serial (31) and parallel (36) heterogeneity can exist simultaneously during bronchoconstriction.

The distributed airways model was able to track significant increases in the heterogeneity of bronchoconstriction with MCh as quantified by either Rσ or Rcv. However, we observed no apparent changes in either Zrs or in the individual model parameters 5 min following a DI, similar to the findings of Kaminsky et al. (24). Given the very low frequency content of our driving signal (lowest frequency 0.078125 Hz), combined with our desire to maintain system stationarity during the forced oscillatory measurements, we waited several minutes following lung inflation before making post-DI measurements. This would ensure that any immediate transient effects of the DI would minimally influence our Fourier-based estimates of Zrs. Nonetheless, we did detect significant increases in our derived heterogeneity index Rcv 5 min following a DI. Such a sustained effect of a DI on airway heterogeneity may reflect local or regional differences in the mechanical equilibrium that is achieved between the opposing airway and tissue forces following inflation. For example the immediate effects of a DI may be to simultaneously dilate many airways, resulting in a transient lowering of airway resistance and a reduction in the heterogeneity of airway diameters. However, during the continuous infusion of a bronchoconstricting agonist, airway smooth muscle will reconstrict against the opposing parenchymal tethering forces. Any relative differences in the post-DI airway-parenchymal stress-relaxation responses may result in a new equilibrium of airway-parenchymal interdependence. This new mechanical equilibrium across many intraparenchymal airway segments may be sufficient to cause a widened distribution of diameters, although the net effect on global measures of effective airway resistance will be minimal.

Such an effect may be one of the reasons for the variable response of a DI during spontaneous and induced bronchoconstriction (10). Traditionally, it has been assumed that individuals with asthma have a diminished capacity to dilate their airways in response to a DI compared with healthy subjects (29, 37). This behavior has been speculated to be the result of diminished airway-parenchymal interdependence due to long-standing inflammation, or alterations in the length-tension properties of airway smooth muscle (12). During MCh-induced bronchoconstriction, a heterogeneous pharmacological response of airway smooth muscle, as suggested by increases in airway resistance heterogeneity, may also lead to heterogeneous alterations in parenchymal distortions and smooth muscle properties. If one assumes that a DI would alter airway-parenchymal interactions in a heterogeneous manner, a post-DI increase in Rcv would be expected.

CONCLUSION

In summary, these data demonstrate that changes in Zrs as assessed with forced oscillations and inverse modeling can be linked to specific structural alterations in the lung using HRCT. When inverse modeling is applied to Zrs data obtained in dogs during MCh-induced bronchoconstriction, either lumped or distributed airways models can accurately partition average airway and tissue properties. Distributed airways models, however, appear to be most appropriate during severe bronchoconstriction.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Insitute Grants P01 HL-010342 and K08 HL-089227, as well as by a Research Starter Grant from the Foundation for Anesthesia Education and Research.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Beatrice Mudge and Richard Rabold for technical assistance in this study. The authors also thank Dr. Monica Hawley for her assistance with statistical analysis of the data and Dr. Brett Simon for his many helpful suggestions during the preparation of the manuscript.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

Although variations in bronchial blood flow can affect the regional airway constriction (46), this only occurs if the delivery of MCh is perfusion limited. Given that our MCh was delivered as a constant infusion and its serum concentration was stable for an extended period of time, it is more likely that MCh delivery to the conducting airways was diffusion-limited in our experiments.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akaike H A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans Automat Contr 19: 716–723, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bates JHT Lung mechanics-the inverse problem. Austral Phys Eng Sci Med 14: 197–203, 1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bates JHT, Allen G. The estimation of lung mechanics parameters in the presence of pathology: a theoretical analysis. Ann Biomed Eng 34: 384–392, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bates JHT, Lutchen KR. The interface between measurement and modeling of peripheral lung mechanics. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 148: 153–164, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Black LD, Dellaca R, Jung K, Atileh H, Israel E, Ingenito EP, Lutchen KR. Tracking variations in airway caliber by using total respiratory vs. airway resistance in healthy and asthmatic subjects. J Appl Physiol 95: 511–518, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown RH, Mitzner W. Functional imaging of airway narrowing. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 137: 327–337, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown RH, Herold CJ, Hirshman CA, Zerhouni EA, Mitzner W. Individual airway constrictor response heterogeneity to histamine assessed by high-resolution computed tomography. J Appl Physiol 74: 2615–2620, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown RH, Kaczka DW, Fallano K, Chen S, Mitzner W. Temporal variability in the responses of individual canine airways to methacholine. J Appl Physiol 104: 1381–1386, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown RH, Mitzner W. Understanding airway pathophysiology with computed tomography. J Appl Physiol 95: 854–862, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fredberg JJ Airway obstruction in asthma: does the response to a deep inspiration matter? Respir Res 2: 273–275, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fredberg JJ, Hoenig A. Mechanical response of the lungs at high frequencies. J Biomech Eng 100: 57–66, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fredberg JJ, Inouye D, Miller B, Nathan M, Jafari S, Raboudi SH, Butler JP, Shore SA. Airway smooth muscle, tidal stretches, and dynamically determined contractile states. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 156: 1752–1759, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fredberg JJ, Stamenovic D. On the imperfect elasticity of lung tissue. J Appl Physiol 67: 2048–2419, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gillis HL, Lutchen KR. Airway remodeling in asthma amplifies heterogeneities in smooth muscle shortening causing hyperresponsiveness. J Appl Physiol 86: 2001–2012, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gillis HL, Lutchen KR. How heterogeneous bronchoconstriction affects ventilation distribution in human lungs: a morphometric model. Ann Biomed Eng 27: 14–22, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hantos Z, Daroczy B, Suki B, Nagy S, Fredberg JJ. Input impedance and peripheral inhomogeneity of dog lungs. J Appl Physiol 72: 168–178, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horsfield K, Kemp W, Phillips S. An asymmetrical model of the airways of the dog lung. J Appl Physiol 52: 21–26, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ito S, Ingenito EP, Arold SP, Parameswaran H, Tgavalekos NT, Lutchen KR, Suki B. Tissue heterogeneity in the mouse lung: effects of elastase treatment. J Appl Physiol 97: 204–212, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaczka DW, Hager DN, Hawley ML, Simon BA. Quantifying mechanical heterogeneity in canine acute lung injury: impact of mean airway pressure. Anesthesiology 103: 306–317, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaczka DW, Ingenito EP, Israel E, Lutchen KR. Airway and lung tissue mechanics in asthma: effects of albuterol. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 159: 169–178, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaczka DW, Ingenito EP, Suki B, Lutchen KR. Partitioning airway and lung tissue resistances in humans: effects of bronchoconstriction. J Appl Physiol 82: 1531–1541, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaczka DW, Lutchen KR. Servo-controlled pneumatic pressure oscillator for respiratory impedance measurements and high frequency ventilation. Ann Biomed Eng 32: 596–608, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaczka DW, Massa CB, Simon BA. Reliability of estimating stochastic lung tissue heterogeneity from pulmonary impedance spectra: a forward-inverse modeling study. Ann Biomed Eng 35: 1722–1738, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaminsky DA, Irvin CG, Lundblad LKA, Thompson-Figueroa J, Klein J, Sullivan MJ, Flynn F, Lang S, Bourassa L, Burns S, Bates JHT. Heterogeneity of bronchoconstriction does not distiguish mild asthmatic subjects from healthy controls when supine. J Appl Physiol 104: 10–19, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lutchen KR, Gillis H. Relationship between heterogeneous changes in airway morphometry and lung resistance and elastance. J Appl Physiol 83: 1192–1201, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lutchen KR, Greenstein JL, Suki B. How inhomogeneities and airway walls affect frequency dependence and separation of airway and tissue properties. J Appl Physiol 80: 1696–1707, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lutchen KR, Hantos Z, Jackson AC. Importance of low-frequency impedance data for reliably quantifying parallel inhomogeneities of respiratory mechanics. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 35: 472–481, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lutchen KR, Hantos Z, Petak F, Adamicza A, Suki B. Airway inhomogeneities contribute to apparent lung tissue mechanics during constriction. J Appl Physiol 80: 1841–1849, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lutchen KR, Jensen A, Atileh H, Kaczka DW, Israel E, Suki B, Ingenito EP. Airway constriction pattern is a central component of asthma severity: the role of deep inspirations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 164: 207–215, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lutchen KR, Suki B, Zhang Q, Petak F, Daroczy B, Hantos Z. Airway and tissue mechanics during physiological breathing and bronchoconstriction in dogs. J Appl Physiol 77: 373–385, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mead J Contribution of compliance of airways to frequency-dependent behavior of lungs. J Appl Physiol 26: 670–673, 1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mitzner W, Blosser S, Yager D, Wagner E. Effect of bronchial smooth muscle contraction on lung compliance. J Appl Physiol 72: 158–167, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Motulsky H, Christopoulos A. Fitting Models to Biological Data using Linear and Nonlinear Regression. A Practical Guide to Curve Fitting. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- 34.Nagase T, Moretto A, Ludwig MS. Airway and tissue behavior during induced constriction in rats: intravenous vs. aerosol administration. J Appl Physiol 76: 830–838, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Navalesi P, Hernandez P, Laporta D, Landry JS, Maltais F, Navajas D, Gottfried SB. Influence of site of tracheal pressure measurement on in situ estimation of endotracheal tube resistance. J Appl Physiol 77: 2899–2906, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Otis AB, McKerrow CB, Bartlett RA, Mead J, McIlroy MB, Selverstone NJ, Radford EP Jr. Mechanical factors in the distribution of pulmonary ventilation. J Appl Physiol 8: 427–443, 1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Skloot G, Permutt S, Togias A. Airway hyperresponsiveness in asthma: a problem of limited smooth muscle relaxation with inspiration. J Clin Invest 96: 2393–2403, 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Suki B, Lutchen KR. Pseudorandom signals to estimate apparent transfer and coherence functions of nonlinear systems: applications to respiratory mechanics. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 39: 1142–1151, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suki B, Yuan H, Zhang Q, Lutchen KR. Partitioning of lung tissue response and inhomogeneous airway constriction at the airway opening. J Appl Physiol 82: 1349–1359, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tgavalekos NT, Musch G, Harris RS, Vidal Melo MF, Winkler T, Schroeder T, Callahan R. Relationship between airway narrowing, patchy ventilation and lung mechanics in asthmatics. Eur Respir J 29: 1174–1181, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tgavalekos NT, Tawhai M, Harris RS, Musch G, Vidal-Melo MF, Venegas JG, Lutchen KR. Identifying airways responsible for heterogeneous ventilation and mechanical dysfunction in asthma: an image functional modeling approach. J Appl Physiol 99: 2388–2397, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tgavalekos NT, Venegas JG, Suki B, Lutchen KR. Relation between structure, function, and imaging in a three-dimensional model of the lung. Ann Biomed Eng 31: 363–373, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thorpe CW, Bates JHT. Effect of stochastic heterogeneity on lung impedance during acute bronchoconstriction: a model analysis. J Appl Physiol 82: 1616–1625, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Venegas JG, Schroeder T, Harris S, Winkler RT, Vidal Melo MF. The distribution of ventilation during bronchoconstriction is patchy and bimodel: A PET imaging study. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 148: 57–64, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wagenmakers EJ, Farrell S. AIC model selection using Akaike weights. Psychon Bull Rev 11: 192–196, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wagner EM, Mitzner W. Contribution of pulmonary versus systemic perfusion of airway smooth muscle. J Appl Physiol 78: 403–409, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yuan H, Suki B, Lutchen KR. Sensitivity analysis for evaluating nonlinear models of lung mechanics. Ann Biomed Eng 26: 230–241, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]