Abstract

Antigen-specific immune responses are impaired after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT). The events contributing to this impairment include host hematolymphoid ablation and donor cell regeneration, which is altered by pharmacologic immune suppression to prevent graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). A generally accepted concept is that graft T cell depletion performed to avoid GVHD yields poorer immune recovery because mature donor T cells are thought to be the major mediators of protective immunity early post-HCT. Our findings contradict the idea that removal of mature donor cells worsens immune recovery post-HCT. By transplantation of purified hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) compared with bone marrow (BM) across donor and recipient pairs of increasing genetic disparity, we show that grafts composed of the purified progenitor population give uniformly superior lymphoid reconstitution, both qualitatively and quantitatively. Subclinical GVHD by T cells in donor BM likely caused this lympho-depleting GVHD. We further determined in the major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-mismatched pairs, that T cell restricted proliferative responses were dictated by donor rather than host elements. We interpret these latter findings to show the importance of peripheral antigen presentation in the selection and maintenance of the T cell repertoire.

Keywords: immune reconstitution, mice, T cell selection

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) constitute a rare population in adult BM and mobilized peripheral blood (MPB) (1). By virtue of their self-renewal and differentiation capacities, these primitive cells are the only population capable of sustaining hematolymphoid development for the life of an individual (1, 2). Thus, for clinical hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT), HSC are the only population required to engraft. Although transplantation of HSCs alone could significantly reduce the complications of allogeneic HCT, the current standard is to transplant BM or MPB-containing primitive progenitors and mature blood and lymphoid elements (3). Given the heterogeneity of the grafts infused, the effect of these cell transplants on host immunity is complex. The desired outcome is the reestablishment of an effective immune system that accurately delineates self from non-self. However, this goal is often confounded by the negative effects of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), a syndrome caused by donor lymphoid cells that recognize alloantigens and destroy host tissues including lymphoid stroma (4, 5). Pharmacotherapy is used to prevent and control GVHD but is ineffective in some patients. Thus, it is in this environment of a lymphocyte-depleted host expressing multiple allo-antigenic targets and under the cover of pharmacotherapy that antigen-specific immunity is expected to recover. Not surprisingly, functional immune reconstitution remains a major problem after allogeneic HCT.

Attempts have been made to improve transplant outcomes and simplify the problem of immune regeneration by eliminating the cells that mediate GVHD. T cell depletion (TCD) of hematopoietic grafts is performed under some circumstances such as when donor and recipients are mismatched at multiple MHC-alleles, as is case for HLA (HLA) haplo-identical transplantations; otherwise the consequence could be devastating and uncontrolled GVHD (6, 7). Recipients of TCD grafts do not require pharmacologic immune suppression and do not usually suffer from clinically detectable acute GVHD (6, 8). It is therefore disappointing that the major causes of morbidity and mortality in patients of TCD grafts are infectious complications (9). Thus, it is generally believed that the benefits achieved by TCD are offset by the perceived slowed and ineffective recovery of lymphoid function. This concern has justified the continued use of unmanipulated allografts and the acceptance of GVHD as a potential complication.

Few studies have attempted to isolate the factors that influence the tempo and functional recovery of antigen-specific immunity post-HCT. Given the numerous factors involved in the reconstruction of antigen-specific immunity, we performed transplantations in mice to examine 2 issues. First, quantitative and qualitative T cell recovery was compared in recipient mice that received highly purified HSC versus whole bone marrow (WBM) administered at doses that did not cause overt GVHD. Second, the consequences of genetic disparity on T cell selection was examined to specifically study the effect of an unshared MHC-allele from the donor on the recovery of antigen-specific responses. Our results reveal that across all allogeneic strains tested, lymph node reconstitution and T cell responses to antigenic challenge were superior in recipients of HSC as compared with WBM. Sampling exclusively from the blood leads to a surprisingly incomplete assessment of immune function. Furthermore, immunization of chimeras with allele-specific peptides revealed that T cell restriction was dictated by the donor MHC-type, a finding that contradicts the conventional understanding of T cell selection. In our view these latter studies suggest a critical role for continuous peripheral MHC stimulation in shaping and maintaining the T cell repertoire.

Results

Chimerism.

Four strain combinations with increasing genetic disparity were tested (Table 1). Congenic transplants were performed between C57BL/6 strains (designated BA and BA.CD45.1) that differ at the nonhistocompatibility loci, Thy-1 and CD45. Thy-1 is expressed on all T cells and CD45 is expressed on all hematopoietic lineage cells, thus the relative contribution of donor versus host to the peripheral blood (PB) and lymphoid organs was determined by antibody staining. MHC-matched transplants were between BA and BALB.B mice that share the H-2b MHC-haplotype. Haplo-identical transplantations were performed by between (BA × SWR) F1 mice (H-2b/q) and (SWR × BALB/c) F1 mice (H-2q/d), which share the coexpressed H-2q molecule but are mismatched at the other MHC allele. For the fully disparate (MHC and minor histocompatibility complex) transplants, donors were BA and recipients BALB/c mice. Recipient mice were lethally irradiated and transplanted with either WBM or HSC. Neither group showed clinical signs of acute GVHD including inability to regain weight in the weeks after the transplant (Fig. S1), diarrhea or skin manifestations.

Table 1.

Donor and recipient mice characteristics at the MHC, Thy-1, and CD45 alleles for each transplant cohort

| Strain disparity | Donor | Donor characteristic |

Recipient | Recipient characteristic |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MHC | Thy-1 | CD45 | MHC | Thy-1 | CD45 | |||

| Congenic | C57BL/6 Thy-1.1 (BA) | H-2b | Thy-1.1 | CD45.2 | C57BL/6 (BA.CD45.1) | H-2b | Thy-1.2 | CD45.1 |

| MHC-matched | C57BL/6 Thy-1.1 (BA) | H-2b | Thy-1.1 | CD45.2 | BALB.B | H-2b | Thy-1.2 | CD45.2 |

| Haplo-identical | (C57BL/6 Thy-1.1) F1 | H-2b/H-2q | Thy-1.1 | CD45.2 | (SWR × BALB/c) F1 | H-2q/H-2d | Thy-1.2 | CD45.2 |

| MHC-mismatched | C57BL/6 Thy-1.1 (BA) | H-2b | Thy-1.1 | CD45.2 | BALB/c | H-2d | Thy-1.2 | CD45.2 |

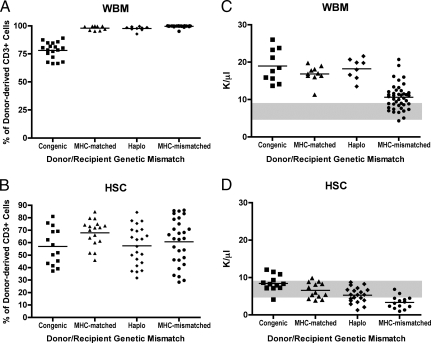

Chimerism studies of PB were performed at 6 weeks postprocedure. As we previously showed, lethal radiation with donor cell rescue results in conversion to full donor type in all blood lineages except T cells, because levels of donor T cells obtained depend on the cellular content of the graft (33). Data in Fig. 1 show blood T cell chimerism in recipients of WBM compared with HSC. Transplants of allogeneic WBM (Fig. 1A) result in near complete conversion to donor type (>97%). In contrast, recipients of HSC allografts demonstrated mixed T cell chimerism with a range of donor contribution between 55% to 66% (Fig. 1B). Transplantation of congenic WBM also resulted in reduced T cell chimerism. This relative lack of host T cells in the recipients of allogeneic WBM as compared with those engrafted with allogeneic HSC or congenic WBM demonstrates that relatively small numbers of alloreactive mature donor cells contained within WBM were capable mediating significant GVH responses manifested by the elimination of host T cells.

Fig. 1.

Chimerism and blood leukocyte counts in WBM versus HSC recipients. (A and B) Donor and host contributions were determined by FACS analysis of PB. Each shape represents 1 animal and its percentage of donor chimerism in the CD3+ subset. The mean cohort chimerism is shown as a line. (A) Allogeneic WBM transplanted mice demonstrated near complete conversion of T cells to donor phenotype. (B) HSC transplanted cohorts retained significant host elements, with donor contributions that ranged from 57 to 68%. Differences were statistically significant between the WBM and HSC congenic, MHC-matched, haploidentical and MHC-mismatched transplants (congenic, P = 0.0003, <0.0001 for all other settings). (C and D) Blood leukocyte counts were elevated in recipients of WBM compared with control mice and HSC recipients. Complete blood counts (CBC) were collected at 6 weeks from mice transplanted with (C) WBM or (D) HSC. Each shape represents 1 animal and the mean cohort count is shown by a line. The normal reference ranges are indicated by solid gray bars. Recipients of congenic, MHC-matched and haplo-identical WBM demonstrated significantly higher leukocyte than the HSC transplanted mice and the normal reference ranges (all P < 0.001). Recipients of MHC-mismatched WBM showed a statistically significant increase in the leukocyte values (P = 0.0151) when compared with normal reference values. HSC transplanted mice showed a stepwise decrease in leukocyte with increased genetic donor-host divergence. Values were within the normal reference range for all cohorts, except the MHC-mismatched recipients, which demonstrated significantly reduced values as compared with the reference (P = 0.004).

Quantitative Immune Reconstitution of PB.

Fig. 1 C and D shows the complete blood counts (CBC) in recipients of WBM (Fig. 1C) as compared with those transplanted with HSC (Fig. 1D). Fig. S2 shows the absolute lymphocyte counts for WBM and HSC recipients. The reference range for control animals (shown in shaded gray) was 5.5 to 9.3 K/μL for the CBC [and 3.7 to 7.8 K/μL for the absolute lymphocyte count (Fig. S2)]. Of note, recipients of congenic, MHC-matched and haplo-identical WBM demonstrated significantly higher leukocyte and absolute lymphocyte counts as compared with untransplanted controls. Recipients of MHC-mismatched WBM had CBCs and absolute lymphocyte counts in the normal range or higher. In contrast, as compared with WBM, recipients of HSC had significantly lower CBCs and absolute lymphocyte counts and, as the genetic difference increased, there was a notable reduction these levels, with the MHC-mismatched mice demonstrating the lowest WBC and absolute count. Furthermore, as compared with control unmanipulated mice, the allografted recipients of MHC-mismatched HSC had CBC and absolute lymphocyte values below the reference or in the low-normal range.

Recovery of Lymph Node Size and Architecture.

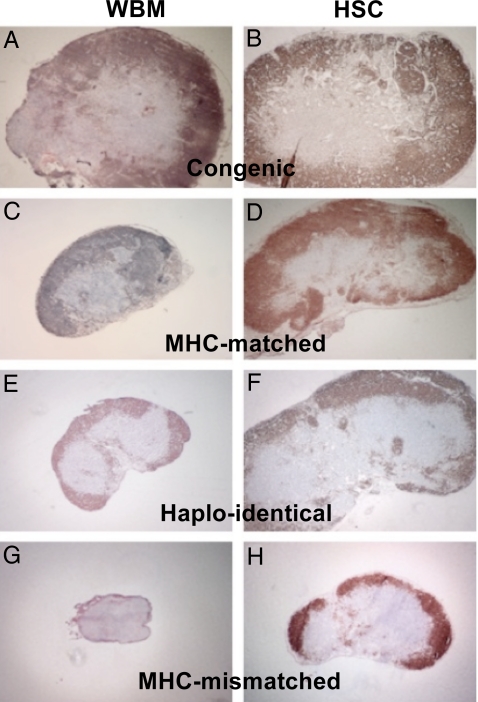

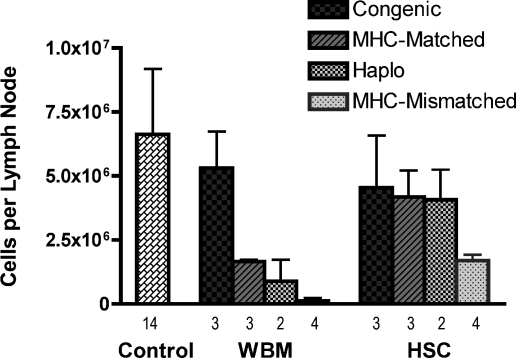

To further assess the effect of genetic disparity and hematopoietic graft content on lymphocyte recovery, histologic and cell count studies were performed on the draining lymph nodes of transplanted mice immunized with a mixture of peptides derived from hen egg lysozyme (HEL). Fig. 2 shows immunohistochemistry staining with anti-B220 to highlight the lymph node architecture by marking the B cell rich cortical areas. Fig. 3 shows the cell counts recovered from the lymph nodes. As expected, untransplanted immunized controls had the largest lymph nodes (data not shown) and highest cell counts (Fig. 3). In the treatment groups 2 notable observations were made: (i) Lymph nodes from recipients of allogeneic HSC were markedly larger than mice that received WBM from the same strain donors, and the total cell counts correlated with these morphologic observations. The most striking difference was between recipients of MHC-mismatched grafts. Recipients of MHC-mismatched WBM demonstrated severe lymph node hypoplasia and architectural breakdown. By comparison, mice transplanted with MHC-mismatched HSC had larger lymph nodes, increased cells counts and intact lymph node architecture, although the size and cell counts were reduced compared with the other HSC recipients. (ii) For WBM transplanted mice, lymph node size decreased as the donor and recipient genetic divergence increased, an effect that was more pronounced compared with the HSC groups. Notably, the relative subset content among the various lymph node groups remained consistent (Fig. S3). Thus, we conclude that unlike the results from the PB wherein WBM transplanted mice showed normal or higher than normal levels of WBCs (Fig. 1 C and D) and lymphocytes (Fig. S2), the lymph node evaluations of WBM recipients revealed relatively poor recovery. The converse was observed in HSC recipients wherein PB studies suggested poor reconstitution whereas the lymph node recovery was clearly superior to the WBM recipients.

Fig. 2.

Lymph node hypoplasia observed in WBM transplanted mice compared with recipients of HSC. Inguinal lymph nodes were harvested 9 days after base of the tail immunization of transplanted mice. The figure shows immunohistochemical staining of representative lymph nodes pictured at 4× magnification. Staining is with α-B220 to highlight the B cell rich cortical regions. Lymph nodes harvested from WBM transplanted mice (A, C, E, and G) were noticeably smaller compared with similar donor and host pairings transplanted with HSC (B, D, F, and H). Marked atrophy and disruption of normal lymphoid architecture was evident in recipients of MHC-mismatched WBM (G), but not HSC (H).

Fig. 3.

Lymph node cell counts revealed markedly decreased lymph node cellularity in WBM transplanted animals compared with those receiving HSCs. Inguinal lymph nodes were recovered 9 days after HEL immunization of WBM and HSC transplanted mice. Lymph nodes cells from the transplant cohorts were pooled and counted. The mean cells per lymph node recovered shown. The total number of lymph nodes included in each cohort is shown below each bar. Although the difference in cell recovery between congenic WBM versus HSC groups was not significant (P = 0.70), the difference between the MHC-matched pairs was nearly significant (P = 0.10) and the difference in MHC-mismatched mice was clearly significant (P = 0.029). The number of experiments in the haploidentical setting were too low to perform a meaningful statistical test.

Functional Recovery of Antigen-Specific Responses.

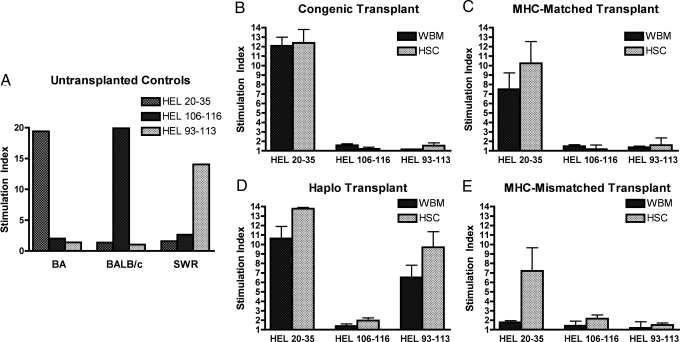

To assess the functional ability of transplanted mice to mount antigen-specific immune responses lymphocyte proliferation assays were performed using MHC-restricted peptides as immunogens. HEL peptide selection was based on prior studies by Moudgil et al. who defined HEL peptides restricted to the MHC class II I-A molecules of the H-2b, H-2d, and H-2q alleles (11). As shown in Fig. 4A, untransplanted control mice immunized with the peptide mixture responded appropriately to the allele-specific peptides. Similarly the congenic transplanted mice (Fig. 4B) responded to the H-2b restricted peptide only, although to a lesser extent than the unmanipulated controls, and there was no difference in the level of response of WBM versus HSC transplanted mice. In contrast, significantly lower responses were observed in recipients of allogeneic WBM as compared with HSC (Fig. 4 C–E), and similar to what as observed for lymph node histology, the most profound differences were noted between the recipients of fully MHC-mismatched grafts.

Fig. 4.

Lymph node cell proliferation to MHC-restricted HEL peptides was donor MHC-restricted and significantly impaired in WBM transplanted mice as compared with recipients of HSC. Transplanted mice were immunized with HEL 20–35 (H-2b-restricted), 106–116 (H-2d restricted) and 93–113 (H-2q restricted) peptides. Shown are the proliferative responses to the 10 nmol per well of peptide. (A) Stimulation of cells from untransplanted controls demonstrate robust proliferation in an MHC-restricted manner. (B) There was no significant difference between WBM and HSC transplanted animals in the congenic pairs. (C) Lymph node cells from mice receiving MHC-matched HSC grafts had significantly greater responses compared with recipients of WBM (P = 0.028). (D) Lymph nodes from haplo-identical recipients demonstrated surprisingly robust proliferation despite a partial mismatch, and the cells responded only to the peptides restricted to donor MHC, H-2b and H-2q. For both the H-2b and H-2q restricted peptides HSC grafts demonstrated greater responses than WBM, however, differences were statistically significant for the H-2b peptide only (H-2b, P = 0.013 and H-2q, P = 0.10). (E) Lymph node from MHC-mismatched recipients demonstrated profound differences between WBM and HSC recipients (P = 0.004) and peptide responses were specific to the donor MHC allele.

The differences in proliferative responses could not be explained by reduced numbers of input T cells derived from the lymph nodes of WBM as compared with HSC recipients. A phenotype analysis of the lymph node cells from transplanted versus control unmanipulated mice failed to reveal skewing of the relative cellular content (Fig. S3). In fact, somewhat surprisingly a higher percentage of CD4+ were present cells in the lymph nodes of mice that received WBM from MHC-mismatched donors as compared those that received MHC-mismatched HSC. The absolute number and percentage of CD4+CD25+ cells in the lymph nodes also did not show any clear differences among the treatment and control groups (Table S1). Thus, in addition to the superior recovery of lymph node morphology and lymph node cell counts for the recipients of purified HSC, these analyses demonstrate that allogeneic HSC recipients demonstrate better functional recovery of antigen-specific immune responses compared with recipients of WBM.

MHC-Restriction.

In addition to measuring the level of antigen-specific responses, the HEL peptide proliferation assay allowed us to identify the dominant MHC element controlling the response to the antigen (Fig. 4). It is notable for the recipients of haplo-identical or fully MHC-mismatched grafts, the proliferative responses were limited to the MHC-type of the donor hematopoietic graft. Thus, in the case of the haplo-identical (BA × SWR) F1 into (SWR × BALB/c) F1 mice, peptide responses were observed restricted by both the shared allele (H-2q) and donor allele (H-2b). Similarly, for the BA into BALB/c transplantations wherein only the HSC recipients mounted peptide-specific proliferation, the responses were restricted by the donor H-2b restricted peptide, not the host H-2d. Taken together these data demonstrate that purified HSC grafts generate all of the elements necessary for T cell selection and can dictate T cell restriction.

Discussion

Reconstitution of a robust immune system after allogeneic HCT remains a major concern for this field. Technology now permits the engineering of grafts to contain only primitive cells that will develop antigen specificity in the host and avoid the problem of GVHD. However, experiences with patients that receive TCD grafts suggest that removal of mature cells place patients in a highly immunocompromised state. Surprisingly little is known about the details of immune recovery post-HCT, and in particular the tempo of functional immune reconstitution of grafts replete with mature lymphoid cells compared with those that are not. Here, our study of immune reconstitution in recipients of HSC versus WBM, and in donor/recipient pairs of increasing genetic disparity bring 2 distinct but related transplantation issues into relief. First, the deleterious effects of subclinical GVHD on immune function across clinically relevant genetic differences was revealed. Second, peripheral lymph node T cells are able to recognize and proliferate in response to MHC molecules expressed on donor-derived antigen-presenting cells (APC), regardless of the recipient MHC type expressed on thymic epithelial cells. These latter observations run counter to conventional thinking regarding T cell selection.

Subclinical GVHD.

Across all allogeneic strain combinations tested, HSC transplanted mice had improved lymph node size, cellularity, architecture and peptide-specific proliferation compared with their WBM counterparts, even though blood CBCs in HSC recipients lag considerably behind the WBM engrafted mice. Although overt GVHD is known to have potent and varied effects on immune reconstitution and targets different lymphoid organs, the effect of subclinical GVHD is less studied and under appreciated, even in experimental transplantation. Mouse WBM recipients as compared with humans have no obvious evidence of GVHD, a difference that is attributed to the way marrow is harvested. Human BM is significantly contaminated with PB, however, mouse BM is extracted as a clean and relatively bloodless BM core from dead animals. Further, among the ≈2–4% of T cells contained in mouse BM are regulatory T cell populations in relatively high proportion that attenuates the effects of the GVHD inducing conventional marrow T cells (12). Thus, clinically detectable GVHD in mice is obtained by adding peripheral lymphocytes to WBM preparations. Our study reinforces the idea that even nonovert allo-immunity has adverse effects on immune function, and further emphasizes that peripheral lymphoid elements are major targets of GVHD.

Prior studies have reported lymph node hypoplasia with GVHD (13–15). In the 1990's, Onoe and Good examined the phenomenon of lymphoid hypoplasia in the setting of subclinical GVHD (4). They studied lymphoid reconstitution of recipients of WBM grafts treated with varying degrees of T cell depletion, and noted reduction of lymph node cellularity in MHC-mismatched but not MHC-matched allografts. The differences between the MHC-matched and mismatched mice prompted the authors to conclude that “disparity in the H-2 region is the primary requirement for the induction of subclinical GVHR.” Although we do not disagree that the disparity at H-2 is likely the most potent initiator of GVHD, our data show differences clear differences between MHC-matched recipients of WBM and HSC, highlighting the contribution of minor histocompatibility antigens to GVHD and the subsequent effects on lymph node reconstitution.

At face value, our data contradict the clinical experience in patients that receive TCD versus unmanipulated hematopoietic grafts plus pharmacologic immune suppression, because the former demonstrate significantly worse functional immunity. However, we did not seek to completely recapitulate these complex clinical scenarios. We have simply observed that superior T cell responses to de novo antigens are uniformly achieved with purified HSC as compared with grafts replete with relatively low levels of mature T cells across all allogeneic settings. Furthermore, we show that measurements taken from blood may not accurately reflect functional reconstitution.

Another caveat of our data are the possibility that by controlling GVHD, pharmacologic immune suppression may in fact act beneficially to preserve immune function. The particular clinical scenario relevant to this point is haplo-identical HCT, wherein grafts are T cell depleted yet still contain measurable amounts of T cells. Such patients usually do not receive pharmacologic GVHD prophylaxis and suffer significantly from infectious complications. A large retrospective study examining the factors affecting the survival of recipients of HLA-identical T cell depleted BM reported that survival was improved in patients that received pharmacologic immune suppression concomitant with T cell depleted grafts (16). We believe these data suggest that residual T cells in a depleted graft are sufficient to cause subclinical GVH effects on immune function—GVH effects that are diminished by immunosuppressive pharmacotherapy.

MHC-Restriction and T Cell Selection.

Our studies measured T cell proliferation to MHC-allele-specific peptides between donor and recipients of different genetic disparities. We were thereby able to assess the effects of donor hematopoietic cells derived de novo from HSC on T cell restriction and peripheral T cell stimulation. Our results unequivocally show that the peptide proliferative response, which is predominantly CD4+ T cell mediated, were restricted to the hematopoietic derived donor MHC-allele. The generally held belief is that the most efficacious method of T cell selection involves positive selection on MHC-expressing thymic epithelial cells (nonhematopoietic), followed by negative selection involving bone-marrow derived elements (17, 18). However, this long-held view of exclusive T cell positive selection on radio-resistant thymic cells is under revision based on more recent studies suggesting that positive selection can occur on BM derived cells (10, 19–21), including fibroblasts or other MHC class II expressing cells in the thymic microenvironment (22–24). T cell development has also been shown to occur by extrathymic pathways (25, 26). In addition, “loose” positive selection on MHC-disparate thymic epithelium may still allow a proportion of T cells to interact with APC in the periphery (27). Thus, it is clear that positive selection can occur through a variety of mechanisms. However, regardless of the specific MHC allele directing positive selection, our data lead us to hypothesize that functional T cell MHC-restriction is dictated predominantly by the MHC molecules present on peripheral APCs.

It is increasingly appreciated that postthymic mature T cells require survival signals in the periphery through constant interaction with an appropriate MHC (28, 29). In our view, postthymic T cell selection continues in the periphery, conceptually with “positive selection” via survival signals from MHC/TCR recognition and “negative selection” via death by MHC/TCR neglect. Although positive selection is likely most efficiently mediated by thymic epithelium, our data support the idea that peripheral APCs can select for populations, even minor ones that then expand and fill the lymphoid compartments. For example, in our MHC-mismatched HSC transplantations (H-2b donor, H-2d recipient) host thymic epithelium may select a far greater proportion of naïve H-2d restricted T cells and a far smaller proportion of H-2b restricted cells selected on HSC derived elements. However, peripheral selection from APCs exclusively expressing H-2b MHC prompts expansion of H-2b restricted T cells to fill niche spaces left empty by MHC-interaction-neglected H-2d restricted T cells.

Conclusions

Our studies were to motivated to better delineate the factors that impair antigen-specific immunity after allogeneic HCT, including the possible disruption of T cell selection and development in the presence of an unmatched MHC allele. Our results on lymphoid recovery after HSC transplantation and the proven ability of even MHC-mismatched HSC derived cells to regenerate antigen-specific T cell responses give confidence that hematopoietic graft engineering will make the problems of GVHD and failed immunity obsolete.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

Mice were bred and maintained at the Stanford University under strict pathogen-free conditions. Table 1 shows the identity of donor and recipients and allelic markers for the different genetic combinations.

HSC Purification and Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation.

HSC were obtained by modified methods as originally described by Spangrude et al. (30) (see SI Methods for HSC purification for details). The T cell content (CD3+ cells) in WBM is ≈2–5% and the log T cell reduction of purified HSC is ≈107. Thus, HSC grafts contained negligible amounts to T cells. A total of 5,000 HSC or an equivalent dose of 1 × 107 unmanipulated WBM-containing 5,000 HSC and a range of 2–5 × 105 T cells were infused by retro-orbital injection within 12 h of irradiation exposure. Lethal radiation doses were delivered to the recipients based on strain (31). BALB.B and BALB/c mice received 800 cGy, BA.45.1 mice received 950 cGy, (SWR/J × BALB/c)F1 mice received 1,000 cGy of whole-body γ irradiation, delivered in 2 split doses >3 h apart.

Chimerism Analysis of PB and Lymph Nodes.

Chimerism was assessed by FACS analysis of PB and lymph node 6 weeks after transplant. Donor versus host cells were differentiated by staining for Thy1.1 (Ox-7) and CD45.1 in congenic, MHC-matched and haplo-identical recipients. Some of the MHC-matched studies used staining for a β2-microglobulin variant (Ly-m11) (BD PharMingen). Stains for lineage markers included: T cells (α-CD4-APC, L3T4), B cells (α-B220-Cy5PE, RA3–6B2), monocytes (α-Mac-1-PE, M1/70) and granulocytes (α-GR.1-PE, 8C5). CBC of experimental mice were obtained by automated hematology analyzer (Abbott Cell-dyn 3500).

Lymph Node Proliferation Assay.

Nine different HEL peptides reported to be restricted to either H-2b, H-2d or H-2q MHC II haplotypes (11, 32) were synthesized by the Stanford Peptide Synthesis Group. Three peptides, HEL 20–35 restricted to H-2b, HEL 106–116 restricted to H-2d, and HEL 93–113 restricted to H-2q, were chosen based immunogenicity as assessed in lymph node proliferation assays of immunized untransplanted control mice. Modified lymph node proliferation assays were performed based on studies by Moudgil and Sercarz (11), which are described in SI Methods.

Histologic Evaluation of Lymph Nodes.

On day 9 after immunization with pooled HEL peptide the draining lymph nodes were removed, flash frozen in OCT (Tissue-Tek, Torrance, CA) and cut in 7 micrometer sections. Sections were fixed in cold acetone, blocked and stained with biotin-α-CD3 at 1:10 or α-B220 (Becton Dickinson Bioscience, Mountain View, CA). Slides were incubated with VECTASTAIN ABC kit (Vector Laboratories) and developed with DAB Substrate Kit (Vector Laboratories), followed by hematoxylin and eosin staining.

Statistical Methods.

Two group comparisons used in Figs. 1, 3, and 4 were performed by the Mann–Whitney test. Leukocyte and absolute lymphocyte counts were compared with the maximum of the standard references ranges (Fig. 1 and Fig. S2) by 1-group t test. All tests were 2-tailed and performed to the 95% significance level.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank D.B Escoto for animal management. This work was supported by a Paul and Daisy Soros Fellowship (to G.J.T.); a Stanford DARE Doctoral Fellowship (to J.A.A.); and National Institutes of Health Grants RO1 HL087240 and PO1 CA049605 (to J.A.S).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: I.L.W. is cofounder and a director of Stem Cells, Inc; this company deals only with neural and liver stem cells. I.L.W. is a stockholder and cofounder in Cellerant, Inc; this company is limited to the transplantation of myeloid progenitors. I.L.W. holds more than $100,000 in stock in Amgen Corporation.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0813335106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Shizuru JA, Negrin RS, Weissman IL. Hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells: Clinical and preclinical regeneration of the hematolymphoid system. Annu Rev Med. 2005;56:509–538. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.54.101601.152334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguila HL, et al. From stem cells to lymphocytes: Biology and transplantation. Immunol Rev. 1997;157:13–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb00971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dreger P, et al. G-CSF-mobilized peripheral blood progenitor cells for allogeneic transplantation: Safety, kinetics of mobilization, and composition of the graft. Br J Haematol. 1994;87:609–613. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1994.tb08321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hirano M, et al. Reconstitution of lymphoid tissues under the influence of a subclinical level of graft versus host reaction induced by bone marrow T cells or splenic T cell subsets. Cell Immunol. 1993;151:118–132. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1993.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lapp WS, Ghayur T, Mendes M, Seddik M, Seemayer TA. The functional and histological basis for graft-versus-host-induced immunosuppression. Immunol Rev. 1985;88:107–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1985.tb01155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Champlin RE, et al. T-cell depletion of bone marrow transplants for leukemia from donors other than HLA-identical siblings: Advantage of T-cell antibodies with narrow specificities. Blood. 2000;95:3996–4003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kernan NA, et al. Analysis of 462 transplantations from unrelated donors facilitated by the National Marrow Donor Program. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:593–602. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199303043280901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitsuyasu RT, et al. Treatment of donor bone marrow with monoclonal anti-T-cell antibody and complement for the prevention of graft-versus-host disease. A prospective, randomized, double-blind trial. Ann Intern Med. 1986;105:20–26. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-105-1-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ho VT, Soiffer RJ. The history and future of T-cell depletion as graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2001;98:3192–3204. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.12.3192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shizuru JA, Weissman IL, Kernoff R, Masek M, Scheffold YC. Purified hematopoietic stem cell grafts induce tolerance to alloantigens and can mediate positive and negative T cell selection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:9555–9560. doi: 10.1073/pnas.170279297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moudgil KD, Sercarz EE. Dominant determinants in hen eggwhite lysozyme correspond to the cryptic determinants within its self-homologue, mouse lysozyme: Implications in shaping of the T cell repertoire and autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 1993;178:2131–2138. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.6.2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffmann P, Ermann J, Edinger M, Fathman CG, Strober S. Donor-type CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells suppress lethal acute graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. J Exp Med. 2002;196:389–399. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Billingham RE, Brent L. A simple method for inducing tolerance of skin homografts in mice. Transplant Bull. 1957;4:67–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baker MB, Riley RL, Podack ER, Levy RB. Graft-versus-host-disease-associated lymphoid hypoplasia and B cell dysfunction is dependent upon donor T cell-mediated Fas-ligand function, but not perforin function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1366–1371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klimpel GR, Annable CR, Cleveland MG, Jerrells TR, Patterson JC. Immunosuppression and lymphoid hypoplasia associated with chronic graft versus host disease is dependent upon IFN-gamma production. J Immunol. 1990;144:84–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marmont AM, et al. T-cell depletion of HLA-identical transplants in leukemia. Blood. 1991;78:2120–2130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matzinger P. Why positive selection? Immunol Rev. 1993;135:81–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1993.tb00645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zinkernagel RM, et al. On the thymus in the differentiation of “H-2 self-recognition” by T cells: Evidence for dual recognition? J Exp Med. 1978;147:882–896. doi: 10.1084/jem.147.3.882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bix M, Raulet D. Inefficient positive selection of T cells directed by haematopoietic cells. Nature. 1992;359:330–333. doi: 10.1038/359330a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martinic MM, et al. Efficient T cell repertoire selection in tetraparental chimeric mice independent of thymic epithelial MHC. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:1861–1866. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252641399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zinkernagel RM, Althage A. On the role of thymic epithelium vs. bone marrow-derived cells in repertoire selection of T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8092–8097. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.8092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choi EY, et al. Thymocyte-thymocyte interaction for efficient positive selection and maturation of CD4 T cells. Immunity. 2005;23:387–396. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hugo P, Kappler JW, McCormack JE, Marrack P. Fibroblasts can induce thymocyte positive selection in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10335–10339. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.10335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li W, et al. An alternate pathway for CD4 T cell development: Thymocyte-expressed MHC class II selects a distinct T cell population. Immunity. 2005;23:375–386. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arcangeli ML, et al. Extrathymic hemopoietic progenitors committed to T cell differentiation in the adult mouse. J Immunol. 2005;174:1980–1988. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.4.1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maillard I, et al. Notch-dependent T-lineage commitment occurs at extrathymic sites following bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 2006;107:3511–3519. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaye J, Vasquez NJ, Hedrick SM. Involvement of the same region of the T cell antigen receptor in thymic selection and foreign peptide recognition. J Immunol. 1992;148:3342–3353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldrath AW, Bevan MJ. Selecting and maintaining a diverse T-cell repertoire. Nature. 1999;402:255–262. doi: 10.1038/46218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kirberg J, Berns A, von Boehmer H. Peripheral T cell survival requires continual ligation of the T cell receptor to major histocompatibility complex-encoded molecules. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1269–1275. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.8.1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spangrude GJ, Heimfeld S, Weissman IL. Purification and characterization of mouse hematopoietic stem cells. Science. 1988;241:58–62. doi: 10.1126/science.2898810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kallman RF, Kohn HI. The influence of strain on acute x-ray lethality in the mouse. I. LD50 and death rate studies. Radiat Res. 1956;5:309–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bixler GS, Jr, Yoshida T, Atassi MZ. T cell recognition of lysozyme. IV. Localization and genetic control of the continuous T cell recognition sites by synthetic overlapping peptides representing the entire protein chain. J Immunogenet. 1984;11:327–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-313x.1984.tb00819.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shizuru JA, Jerabek L, Edwards CT, Weissman IL. Transplantation of purified hematopoietic stem cells: Requirements for overcoming the barriers of allogeneic engraftment. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 1996;2:3–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.