Abstract

BACKGROUND:

When clinical guidelines affect large numbers of individuals or substantial resources, it is important to understand their benefits, harms and costs from a population perspective. Many countries’ dyslipidemia guidelines include these perspectives.

OBJECTIVE:

To compare the effectiveness and efficiency of the 2003 and 2006 Canadian dyslipidemia guidelines for statin treatment in reducing deaths from coronary artery disease (CAD) in the Canadian population.

METHODS:

The 2003 and 2006 Canadian dyslipidemia guidelines were applied to data from the Canadian Heart Health Survey (weighted sample of 12,300,000 people), which includes information on family history and physical measurements, including fasting lipid profiles. The number of people recommended for statin treatment, the potential number of CAD deaths avoided and the number needed to treat to avoid one CAD death with five years of statin therapy were determined for each guideline.

RESULTS:

Compared with the 2003 guidelines, 1.4% fewer people (20 to 74 years of age) are recommended statin treatment, potentially preventing 7% more CAD deaths. The number needed to treat to prevent one CAD death over five years decreased from 172 (2003 guideline) to 147 (2006 guideline).

CONCLUSIONS:

From a population perspective, the 2006 Canadian dyslipidemia recommendations are an improvement of earlier versions, preventing more CAD events and deaths with fewer statin prescriptions. Despite these improvements, the Canadian dyslipidemia recommendations should explicitly address issues of absolute benefit and cost-effectiveness in future revisions.

Keywords: Death, Health care delivery, Lipids, Myocardial infarction

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

Lorsque des directives cliniques touchent beaucoup d’individus ou sollicitent des ressources substantielles, il est important d’en comprendre les avantages, les inconvénients et le coût, du point de vue des populations. Les directives de nombreux pays sur les dyslipidémies tiennent compte d’une telle perspective.

OBJECTIF :

Comparer l’efficacité et l’efficience des directives canadiennes de 2003 et de 2006 sur le traitement des dyslipidémies au moyen des statines, pour ce qui est de réduire le nombre de décès d’origine coronarienne dans la population canadienne.

MÉTHODES :

Les directives canadiennes de 2003 et de 2006 sur les dyslipidémies ont été appliquées à des données de l’Enquête canadienne sur la santé cardiovasculaire (échantillon pondéré de 12 300 000 personnes), incluant des renseignements sur les antécédents familiaux et certains paramètres physiques, notamment, les profils lipidiques à jeun. Pour chaque directive, les auteurs ont déterminé le nombre de personnes à qui le traitement par statines a été recommandé, le nombre potentiel de décès d’origine coronarienne évités et le nombre de patients à traiter pour éviter un décès d’origine coronarienne au moyen d’un traitement par statine d’une durée de cinq ans.

RÉSULTATS :

Comparativement aux directives de 2003, on note une réduction de 1,4 % du nombre de personnes (de 20 à 74 ans) chez qui un traitement par statine a été recommandé, ce qui potentiellement préviendrait 7 % plus de décès d’origine coronarienne. Le nombre de patients à traiter pour prévenir un décès d’origine coronarienne sur une période de cinq ans est passé de 172 (directives de 2003) à 147 (directives de 2006).

CONCLUSIONS :

Du point de vue des populations, les recommandations canadiennes de 2006 sur les dyslipidémies constituent une amélioration par rapport aux versions antérieures, puisqu’elles permettent de prévenir plus d’incidents et de décès coronariens au moyen d’un moins grand nombre d’ordonnances de statines. Malgré ces améliorations, lors des futures révisions, les recommandations canadiennes sur les dyslipidémies devraient expressément tenir compte des bénéfices et de la rentabilité absolus des interventions.

When clinical guidelines affect large numbers of people or substantial resources, such as the Canadian dyslipidemia recommendations, it is important to understand their benefits, harms and costs from a population perspective. Currently, hundreds of thousands of Canadians take statins, at a direct drug cost of approximately $2 billion, or more than 1% of total health care expenditures (1). We previously assessed the 2003 Canadian recommendations from a population perspective (2) and found that they performed worse than those of other countries’ recommendations. We now provide an updated assessment for the most recent (2006) changes to the Canadian recommendations (3). A detailed description of our methodology, including the assumptions of our model, can be found in the accompanying Appendixes 1 to 3.

The most recent recommendations decreased low-density lipoprotein (LDL) target levels for high-risk people (from 2.5 mmol/L to 2.0 mmol/L) and increased LDL targets for low-risk people (from 4.5 mmol/L to 5.0 mmol/L). We assessed these changes with respect to three population characteristics – the number of people recommended statin treatment, the potential community effectiveness (defined as the potential number of deaths from coronary artery disease [CAD] prevented if all Canadians were screened, treated and compliant according to the guidelines) and the guideline efficiency (defined as the number of deaths from CAD prevented in relation to the number of people recommended statin treatment and measured by the overall number needed to treat [NNT]).

As with our previous assessment, we used the 1990 Canadian Heart Health Survey (CHHS), the last national population health survey that included physical measures such as cholesterol levels and blood pressure (2,4,5). The 2006 Canadian population had an older age distribution compared with 1990, which will likely result in an underestimation of the number of individuals in the moderate and high-risk groups. However, the CHHS is well-suited to estimate the potential effectiveness of statins because its measurements pre-date the widespread adoption of statin therapy in Canada. Furthermore, there is no strong evidence that the risk of CAD among Canadians has appreciably changed in the intervening period, given that the incidence of CAD is stable (6) and, aside from smoking, risk factors are either unchanged or have shown small prevalence increases (7). The CHHS methods have previously been described in detail (8). We applied the screening and treatment recommendations to each survey respondent, as described by the guidelines. We included only respondents who were questioned about their family history of heart disease to allow for comparison with our assessment of other national and international guidelines. CHHS respondents were allocated to risk groups based on their 10-year probability of a ‘hard’ CAD event, as determined by the Framingham-based risk point scoring system used in the Canadian guidelines. The Framingham risk index is an accurate and discriminating tool for the estimation of CAD risk, but it cannot be substituted for the history and physical examination taken by the clinician, which may aid in the detection of less common causes of dyslipidemia. For example, our model did not account for the small number (9) of individuals with monongenic dyslipidemias, such as familial hypercholesterolemia, who may be inappropriately labelled as low-risk by the Framingham risk algorithm alone. Finally, we assumed that individuals would be recommended statin therapy if their LDL level exceeded the target level set for their particular risk category (Appendixes 1 to 3).

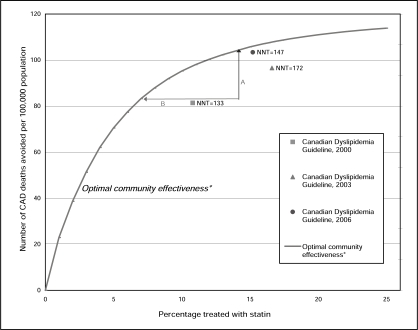

We found that compared with the 2003 guidelines, the latest updates recommend statin treatment to 1.4% fewer people (a decrease from 16.6% to 15.2% of Canadians 20 to 74 years of age) while potentially preventing 7.0% more deaths from CAD (an increase from 96 to 103 CAD deaths prevented per 100,000 Canadians) (Figure 1). The recommendations’ overall efficiency improved by 14.5% (NNT from 172 to 147), or equal to approximately $290 million in direct drug cost savings at the national level given current expenditures (14.5% of $2 billion equals $290 million).

Figure 1).

Number of coronary artery disease (CAD) deaths avoided per 100,000 population over five years versus the percentage of Canadian population 20 to 74 years of age treated with statins based on the 2000 to 2006 Canadian dyslipidemia guidelines. *The optimal community effectiveness curve shows the number of CAD deaths avoided if the highest-risk people were treated first. A – The effectiveness gap or the difference between the potential deaths avoided by the guideline recommendations compared with the optimal number of deaths avoided if the highest-risk people were recommended treatment. B – The efficiency gap or the difference between percentage of the population recommended statin treatment compared with the minimum population who could be treated to avoid the same number of deaths. NNT Number needed to treat to prevent one CAD death over five years

At face value, the New Zealand Guidelines Group (6) and the Joint British Societies (7,8) continue to have more favourable population characteristics than the Canadian recommendations, mainly because they do not recommend statins to low-risk people unless they have very high cholesterol levels. For example, the 2003 New Zealand dyslipidemia guidelines recommended statins to low-risk individuals (10-year CAD risk of less than 10%) only if the total cholesterol is greater than 8 mmol/L or if the total cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio is greater than 8. The 1998 and 2005 Joint British Societies’ dyslipidemia guidelines (7,8) do not use lipid targets for statin therapy for people at low risk of CAD. In the 1990 Canadian population, low-risk people comprised 8.4% of the population recommended statin therapy, or 1.3% of Canadians 20 to 74 years of age, according to the 2006 recommendations. People at very low risk (0% to 5% 10-year risk of CAD) comprised 3.3% of the population recommended statin therapy.

Statin recommendations for people at low and very low risk for CAD are debated for two reasons. First, meta-analyses and reviews reach different conclusions about whether statins are efficacious, in terms of relative benefit, in low- and very low-risk groups. There are no statin intervention trials in very low-risk people, with differing views on whether the (same) relative benefit that is observed in high-risk groups holds for low- and very low-risk groups, including low-risk people whose lipid levels are above the Canadian targets. Second, there is no consensus on whether absolute benefit, cost-effectiveness and resource implications should be considered when developing clinical recommendations and guidelines. The Canadian recommendations do not explicitly include these perspectives, but other countries’ guidelines do. Even if statins have a favourable relative benefit for very low-risk groups, the absolute benefit is very small. We estimated the mean 10-year CAD risk for the very low-risk group to be 1.2%, which equals an absolute benefit of 0.05% (NNT=1940) for five years of statin therapy to prevent CAD.

CONCLUSIONS

From a population perspective, the 2006 Canadian dyslipidemia recommendations are an improvement over earlier versions. The updated guidelines have the potential to prevent more CAD events and deaths with fewer statin prescriptions. However, the Canadian guidelines should be further discussed. Recommending treatment to very low-risk people appears to be neither an efficient nor effective way to reduce cardiovascular outcomes, but has large resource and patient implications given the number of people in this group.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this project was provided by a grant from the Canadian Population Health Initiative.

APPENDIX 1

Screening criteria and classification of risk groups as defined in the 2003 and 2006 Canadian recommendations for the management of dyslipidemia as applied to the population of the Canadian Heart Health Survey (CHHS)

| Guideline recommendations | Application to CHHS dataset | |

|---|---|---|

|

Screening criteria according to the 2003 recommendations | ||

| Age | Men >40 years of age, women >50 years of age or postmenopausal | Men >40 years of age, women >50 years of age |

| Risk factors | Presence of ≥1 risk factor for coronary artery disease (CAD) | Any of obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2), hypertension (blood pressure higher than140/90 mmHg) or smoking |

| Family history | Strong family history of premature CAD | Self-reported family history of CAD |

| Disease state | Presence of diabetes | Self-reported diabetes |

| Presence of xanthoma or other stigmata of dyslipidemia | Previous myocardial infarction or angina | |

| Evidence of atherosclerosis | ||

|

Screening criteria according to the 2006 recommendations | ||

| Age | Men >40 years of age, women >50 years of age or postmenopausal | Men >40 years of age, women >50 years of age |

| Risk factors | Presence of ≥1 risk factor for CAD | Any of obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2), hypertension (blood pressure higher than140/90 mmHg) or smoking |

| Family history | Strong family history of premature CAD | Self-reported family history of CAD |

| Disease state | Presence of diabetes | Self-reported diabetes |

| Manifestations of hyperlipidemia | Previous myocardial infarction or angina | |

| Exertional chest discomfort, dyspnea or erectile dysfunction | ||

| Chronic kidney disease or systemic lupus erythematosus | ||

| Evidence of atherosclerosis | ||

|

Risk group definitions according to the 2003 recommendations | ||

| High | 10-year risk of ‘hard’ CAD event (CAD-related death, nonfatal myocardial infarction) ≥20% or history of diabetes or any atherosclerotic disease | 10-year risk of ‘hard’ CAD event (CAD-related death or nonfatal myocardial infarction) ≥20% or self-reported diabetes or self-reported past myocardial infarction or angina |

| Moderate | 10-year risk of ‘hard’ CAD event 11%–19% | 10-year risk of ‘hard’ CAD event 11%–19% |

| Low | 10-year risk of ‘hard’ CAD event ≤10% | 10-year risk of ‘hard’ CAD event ≤10% |

|

Risk group definitions according to the 2006 recommendations | ||

| High | 10-year risk of ‘hard’ CAD event (CAD-related death, nonfatal myocardial infarction) ≥20% or history of diabetes or any atherosclerotic disease, and most patients with chronic kidney disease | 10-year risk of ‘hard’ CAD event (CAD-related death or nonfatal myocardial infarction) ≥20% or self-reported diabetes or self-reported past myocardial infarction or angina |

| Moderate | 10-year risk of ‘hard’ CAD event 11%–19% | 10-year risk of ‘hard’ CAD event 11%–19% |

| Low | 10-year risk of ‘hard’ CAD event ≤10% | 10-year risk of ‘hard’ CAD event ≤10% |

BMI Body mass index

APPENDIX 2

Analysis of the 1992 Canadian population by risk group using the 2003 recommendations for the management of dyslipidemia*†

| Analysis | Low risk | Moderate risk | High risk | Total | High-risk subgroups

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of CVD | History of diabetes and age ≥30, years | 10-year risk of CAD >30% | |||||

| Estimated number (%) of individuals | 10,200,000 (82.9) | 790,000 (6.4) | 1,330,000 (10.7) | 12,350,000 (100.0) | 500,000 (4.0) | 390,000 (3.2) | 430,000 (3.5) |

| Number (%) recommended for lipid testing | 7,100,000 (69) | 790,000 (100) | 1,330,000 (100) | 9,200,000 (75) | 500,000 (100) | 390,000 (100) | 430,000 (100) |

| Number recommended for statin therapy | 450,000 | 430,000 | 1,150,000 | 2,000,000 | 400,000 | 330,000 | 400,000 |

| Percentage recommended statins of those screened | 6 | 55 | 87 | 22 | 81 | 85 | 96 |

| Number of CAD-related deaths prevented over 5 years§ | 300 | 1140 | 10,400 | 12,000 | 6360 | 1255 | 2800 |

| NNT to prevent 1 CAD-related death over 5 years of statin therapy§ | 1477 | 380 | 111 | 172 | 64 | 265 | 148 |

Raw numbers (before rounding) were used to calculate all percentages and the number needed to treat (NNT).

*The reference population included Canadians in 1992 20–74 years of age. Data from the Canadian Heart Health Survey were used to identify the risk categories of respondents;

†See Appendix 1 for risk group definitions;

§Calculated using Framingham study equations given a 24% relative efficacy of statins. CAD Coronary artery disease; CVD Cardiovascular disease

APPENDIX 3

Analysis of the 1992 Canadian population by risk group using the 2006 recommendations for the management of dyslipidemia*†

| Analysis | Low risk | Moderate risk | High risk | Total | Very high-risk subgroups

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of CVD | History of diabetes, and age ≥30, years | 10-year risk of CAD >30% | |||||

| Estimated number (%) of individuals | 10,200,000 (82.9) | 790,000 (6.4) | 1,330,000 (10.7) | 12,350,000 (100.0) | 500,000 (4.0) | 390,000 (3.2) | 430,000 (3.5) |

| Number (%) recommended for lipid testing | 7,100,000 (69) | 790,000 (100) | 1,330,000 (100) | 9,200,000 (75) | 500,000 (100) | 390,000 (100) | 430,000 (100) |

| Number recommended for statin therapy | 150,000 | 430,000 | 1,275,000 | 1,900,000 | 470,000 | 370,000 | 430,000 |

| Percentage recommended statins of those screened | 2 | 55 | 96 | 20 | 95 | 94 | 100 |

| Number of CAD-related deaths prevented over 5 years§ | 155 | 1100 | 11,400 | 12,700 | 7200 | 1300 | 2900 |

| NNT to prevent 1 CAD-related death over 5 years of statin therapy§ | 1011 | 380 | 112 | 147 | 66 | 283 | 148 |

Raw numbers (before rounding) were used to calculate all percentages and the number needed to treat (NNT).

*The reference population included Canadians in 1992 20–74 years of age. Data from the Canadian Heart Health Survey were used to identify the risk categories of respondents;

†See Appendix 1 for risk group definitions;

§Calculated using Framingham study equations given a 24% relative efficacy of statins. CAD Coronary artery disease; CVD Cardiovascular disease

REFERENCES

- 1.Abramson J, Wright JM. Are lipid-lowering guidelines evidence-based? Lancet. 2007;369:168–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60084-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manuel DG, Kwong K, Tanuseputro P, et al. Effectiveness and efficiency of different guidelines on statin treatment for preventing deaths from coronary heart disease: Modelling study. BMJ. 2006;332:1419–23. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38849.487546.DE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McPherson R, Frohlich J, Fodor G, Genest J, Canadian Cardiovascular Society Canadian Cardiovascular Society position statement – recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of dyslipidemia and prevention of cardiovascular disease. Can J Cardiol. 2006;22:913–27. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(06)70310-5. (Erratum in 2006;22:1077) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manuel DG, Lim J, Tanuseputro P, et al. Revisiting Rose: Strategies for reducing coronary heart disease. BMJ. 2006;332:659–62. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7542.659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manuel DG, Tanuseputro P, Mustard CA, et al. The 2003 Canadian recommendations for dyslipidemia management: Revisions are needed. CMAJ. 2005;172:1027–31. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1040202. (Erratum in 2005;173:133) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.New Zealand Guidelines Group The assessment and management of cardiovascular risk, 2003. < www.nzgg.org.nz/guidelines/0035/CVD_Risk_Full.pdf> (Version current at June 29, 2004)

- 7.British Heart Foundation Updated guidelines on cardiovascular disease risk assessment. British Heart Foundation Fact file (08/2004). British Heart Foundation in association with the British Cardiac Society. 5-1–2005.

- 8.British Cardiac Society; British Hypertension Society; Diabetes UK; HEART UK; Primary Care Cardiovascular Society; Stroke Association JBS 2: Joint British Societies’ guidelines on prevention of cardiovascular disease in clinical practice. Heart. 2005;91(Suppl 5):v1–52. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.079988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]