Abstract

Contrast-enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance imaging can define the territory and extent of myocardial infarction from patterns of late gadolinium enhancement. Following failure to reperfuse with thrombolytic therapy, a case of myocardial infarction is described in which ongoing symptoms and an electrocardiogram change led to a diagnostic dilemma. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging confirmed an apical infarction, an aneurysm and acute pericarditis. In addition, late gadolinium enhancement unexpectedly revealed the presence of biventricular apical thrombi. The prevalence of cardiac thrombi and pulmonary emboli may be greater than generally appreciated.

Keywords: AMI, Cardiac MR, Thrombolysis, Thrombus

Abstract

L’imagerie par résonance magnétique cardiaque à contraste rehaussé permet de définir le territoire et l’ampleur de l’infarctus du myocarde à partir de l’image de phase tardive rehaussée par le gadolinium. Après l’échec de la reperfusion par thrombolytiques, on décrit un cas d’infarctus du myocarde au cours duquel les symptômes persistants et les changements à l’ÉCG ont mené à un dilemme diagnostique. L’imagerie par résonance magnétique cardiaque a confirmé un infarctus apical, un anévrisme et une péricardite aiguë. De plus, la phase tardive du rehaussement au gadolinium a révélé de manière imprévue la présence de thrombi apicaux biventriculaires. La prévalence des thrombi cardiaques et des embolies pulmonaires pourrait se révéler plus forte qu’on ne l’a généralement cru.

We report a case of initially uncomplicated acute myocardial infarction. However, ongoing symptoms and equivocal investigations led to a diagnostic dilemma. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) clarified the sequence of events and unexpectedly revealed an apical aneurysm with biventricular apical thrombi.

CASE PRESENTATION

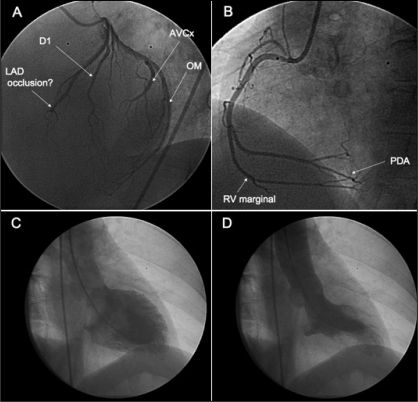

A 59-year-old woman, a hypertensive smoker, developed new-onset retrosternal chest pain while at rest. She was not known to have had coronary artery disease in the past. The initial electrocardiogram (ECG) performed in the emergency department did not meet criteria for ST segment elevation myocardial infarction. However, unequivocal anteroapical changes subsequently occurred within 1 h of admission, prompting the administration of thrombolytic therapy. Despite this, she remained symptomatic, and the ECG changes worsened with additional involvement of the inferior leads (Figure 1). Urgent angiography was performed with a goal of rescue percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). No definitive occlusion of the distal left anterior descending or posterior descending arteries could be identified (Figures 2A and 2B). The vessels were of small calibre (smaller than 2 mm) despite taking multiple views after intracoronary nitrate. PCI was discounted. A dyskinetic apical segment was evident on left ventriculography (Figures 2C and 2D). The area was localized and unlike that seen in takotsubo cardiomyopathy (1). Subsequent confirmatory biochemical evidence of infarction became evident, with a rise in troponin I over the next 24 h (0.15 μg/L to 0.61 μg/L to 20.4 μg/L) and creatine kinase (86 U/L to 623 U/L).

Figure 1).

Electrocardiogram after failure to reperfuse 90 min after tenecteplase administration. Persistent anteroapical and inferior ST segment elevations were seen

Figure 2).

A Coronary angiogram performed in left anterior oblique 60° view. The termination of the small (<2 mm), tapering distal left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) was uncertain. B Dominant right coronary artery. Posterior descending artery (PDA) supplies inferior wall. C Left ventriculogram in diastole. D Apical aneurysm evident in systole. D1 First diagonal; AVCx Atrioventricular groove circumflex artery; OM Obtuse marginal; RV Right ventricular

The patient continued to have intermittent chest pain over the ensuing 72 h. In view of the diagnostic uncertainty, contrast-enhanced cardiac MRI was requested to better characterize the nature and extent of the myocardial insult. This was performed on the fourth day after admission.

Cardiac MRI

Steady-state, free precession cine MRI demonstrated a discrete territory of biventricular apical dyskinesis (Figures 3A and 3B). This was more localized than that seen with apical ballooning syndrome (1).

Figure 3).

Four-chamber cardiac magnetic resonance imaging studies performed on day 4 of admission. A Systolic frames obtained from a fast imaging steady-state, free precession sequence showing aneurysmal left ventricular (LV) and right ventricular (RV) apexes. B Diastolic still frame demonstrating normal ventricular and atrial dimensions. C Still frame from late contrast-enhanced two-dimensional inversion recovery, gradient echo, fast low angle-shot magnetic resonance sequence. Late gadolinum enhancement (LGE) was consistent with myocardial infarction of the cardiac apex. Thrombi appeared as low signal intensity filling defects in both ventricular apexes

Following 0.2 mmol/kg of the intravenous contrast agent gadolinium, an inversion recovery gradient echo sequence confirmed a biventricular apical scar (Figure 3C). This was not in keeping with myocarditis, which typically has a patchy and mid-wall distribution.

Myocardial injury, whether due to infarct necrosis or fibrosis, is detected by late gadolinium enhancement. Idiopathic restrictive cardiomyopathy with endomyocardial fibrosis was considered, because this has been reported to occur with biventricular apical thrombi (2). This differential diagnosis, however, appeared less likely in the absence of left and right atrial enlargement, obliteration of the apex by fibrosis, or regurgitation of the atrioventricular valves (2).

The apical site of the late gadolinium enhancement pattern was consistent with a myocardial area perfused by a long, type III left anterior descending coronary artery wrapping around the cardiac apex. This explained the ECG changes (Figure 1). No pericardial effusion was present to suggest early Dressler’s syndrome. Aortic arch pathology was excluded.

The diagnosis of exclusion was a nonreperfused apical infarction with overlying pericarditis. The dramatic and novel finding in the present case, however, was the evidence of thrombi in both ventricular apexes (Figure 3C).

The cardiac MRI scan clarified the clinical series of events. It confirmed the need for secondary preventative therapy after myocardial infarction and led to the prescription of warfarin therapy to prevent stroke and pulmonary thromboembolus.

DISCUSSION

Biventricular apical thrombi

The present report highlights the potential existence of concurrent right and left ventricular thrombi in acute myocardial infarction. The role of cardiac MRI in left ventricular thrombus detection has been previously described (3,4); however, to our knowledge, there have been no prior imaging reports of simultaneous left and right ventricular thrombi.

This finding would rarely be evident clinically. It is difficult to diagnose by echocardiography because of the extensive trabeculae within the right ventricular apex and the proximity to the imaging probe when scanning. Hospital postmortem studies have demonstrated a high prevalence of right-sided intracardiac thrombi, with thrombi found in 7.2% of 23,796 cases in a consecutive autopsy series (5). Furthermore, patients dying from ischemic heart disease had a 3.2 times higher risk (95% CI 2.7 to 3.6) of right-sided intracardiac thrombus compared with age- and sex-matched controls. This was associated with evidence of pulmonary embolus in 43% (5).

In addition, the present report illustrated the ability of cardiac MRI to define a localized apical aneurysm and delineate between subendocardial and full thickness infarction. Our patient underwent early angiography and did not have the option of coronary intervention. However, the Occluded Artery Trial (OAT) (6) recently assessed the outcomes of patients randomly assigned to coronary intervention or medical therapy for persistently occluded arteries three to 28 days postmyocardial infarction. The median time of eight days was outwith the currently accepted period in which PCI has been demonstrated to salvage myocardium. No reduction in the combined end point of death, recurrent myocardial infarction or heart failure occurred in the PCI group. A limitation of the OAT study was the absence of a requirement to demonstrate reversible ischemia or viable myocardium.

The ability of cardiac MRI to determine whether a significant infarction has occurred, coupled with an assessment of myocardial ischemia, might have altered the outcome of the OAT trial.

REFERENCES

- 1.Teraoka K, Kiuchi S, Takada N, Hirano M, Yamashina A. No delayed enhancement on contrast magnetic resonance imaging with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2005;111:e261–2. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000162471.97111.2C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cury RC, Abbara S, Sandoval LJ, Houser S, Brady TJ, Palacios IF. Visualization of endomyocardial fibrosis by delayed-enhancement magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation. 2005;111:e115–7. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000157399.96408.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barkhausen J, Hunold P, Eggebrecht H, et al. Detection and characterization of intracardiac thrombi on MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:1539–44. doi: 10.2214/ajr.179.6.1791539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mollet NR, Dymarkowski S, Volders W, et al. Visualization of ventricular thrombi with contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in patients with ischemic heart disease. Circulation. 2002;106:2873–6. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000044389.51236.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ogren M, Bergqvist D, Eriksson H, Lindblad B, Sternby NH. Prevalence and risk of pulmonary embolism in patients with intracardiac thrombosis: A population-based study of 23 796 consecutive autopsies. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:1108–14. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hochman JS, Lamas GA, Buller CE, et al. Occluded Artery Trial Investigators Coronary intervention for persistent occlusion after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2395–407. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]