Abstract

Eating routines are a compelling issue because recurring eating behaviors influence nutrition and health. As non-traditional and individualized eating patterns have become more common, new ways of thinking about routine eating practices are needed. This study sought to gain conceptual understanding of working adults' eating routines. Forty-two purposively sampled US adults reported food intake and contextual details about eating episodes in qualitative 24-hour dietary recalls conducted over 7 consecutive days. Using the constant comparative method, researchers analyzed interview transcripts for recurrent ways of eating that were either explicitly reported by study participants as “routines” or emergent in the data. Participants' eating routines included repetition in food consumption as well as eating context, and also involved sequences of eating episodes. Eating routines were embedded in daily schedules for work, family, and recreation. Participants maintained purposeful routines that helped balance tension between demands and values, but they modified routines as circumstances changed. Participants monitored and reflected upon their eating practices and tended to assess their practices in light of their personal identities. These findings provide conceptual insights for food choice researchers and present a perspective from which practitioners who work with individuals seeking to adopt healthful eating practices might usefully approach their tasks.

Keywords: Routine, food choice, eating patterns, habits, repetition, qualitative methods, embedded, reflective, agency, identities

Introduction

People maintain routines related to work, family, and other domains of their lives, including eating (Warde & Hetherington, 1994). Routines include social and temporal components that can provide organization (Clark, 2000; Becker, 2004), efficiency (Khare & Inman, 2006; Becker, 2004), comfort/security (Connors, Bisogni, Sobal, & Devine, 2001), and identity (Zisberg, Young, Schepp, & Zysberg, 2007). Routines are strategies for conserving physical and cognitive resources (Zisberg et al., 2007), and they simplify daily activities because life runs more smoothly when things are predictable and expected from day to day and week to week

Routines are shaped by environmental and cultural contexts (Gallimore & Lopez, 2002). Routines reflect the thoughts, behaviors, and tastes that people internalize and enact over time as a result of the social structures and cultures in which they have lived (Bourdieu, 1984; Warde & Hetherington, 1994). This applies to how people deal with food and eating (Beardsworth and Keil, 1997) and time (Daly, 1996). From this perspective, routines related to eating reflect what people have learned is appropriate, expected, or desirable in their cultural and social contexts, e.g. the timing, foods, and settings for daily “breakfast,” “lunch,” and “dinner” plus “snacks” in the United States.

Routines also reflect the way that people deal with the tensions between the demands they face and resources that they have in the multiple settings in which they live. From this perspective, people develop routines for everyday decisions that are a compromise between what is desirable and what is practical in given settings (Gallimore & Lopez, 2002). Betsch, Fiedler & Brinkmann (1998) conceptualize a routine as “an option that comes to mind as a solution when a person recognizes a particular decision problem, which involves personal goals and familiar context conditions.” People establish routines when they face repeated decision problems and when they find that particular solutions work well. People deviate from traditional “proper meals” in timing, foods, and social settings as a result of perceived work demands, family demands, and time scarcity (e.g. Devine, Connors, Sobal & Bisogni, 2003; Warde, 1999; Poulain, 2002).

Routines have a dynamic quality as they adapt to changing contexts as necessary (Denham, 2002). This paradoxical quality allows routines to be resilient and consistent yet always evolving as the situations in life change (Denham, 2002). DeVault (1991) described how parents continuously revise and adjust their food routines in response to changes as an ordinary part of the work of feeding a family

The Food Choice Process Model views people as constructing food choice thoughts, feelings, and actions as a result of their life course experiences and a variety of influences that may be cultural, personal, social, contextual, and resource related (Furst, Connors, Bisogni, Sobal, & Falk, 1996). Through a personal system, people construct food choice values (e.g. taste, convenience, cost, managing relationships, and health) and develop ways to achieve these values in different situations (Connors et al., 2001). People also develop ways of negotiating and balancing these values when all values cannot be met at the same time. The personal food system includes cognitive processes of classifying foods and situations, strategies for implementing food choice values (including routinization to simplify recurrent eating choices) (Falk, Bisogni, & Sobal, 1996), and scripts or plans to guide food behavior in repeating situations (Blake, Bisogni, Sobal, Jastran, & Devine, 2008; Falk et al., 1996). This conceptualization is consistent with views of routines as systems that are organized around personal goals and ideals (Bargh & Barndollar, 1996; Ouellette & Wood, 1998). Routines that fit with competing goals and ideals in eating situations are often complex and carefully constructed over time to provide the best fit or solution to food choice dilemmas (Falk et al., 1996). Once found to work well, successful routines for eating provide a level of comfort and predictability, with momentum for repetition (Connors et al., 2001).

Nutrition professionals are acutely aware of the importance of eating patterns in assessing diet as it relates to chronic disease and behavior change (Snetselaar, 1997). A client's identification of recurring patterns of behavior is a key component of dietary counseling (Snetselaar, 1997). However “eating routines” as a concept in food choice research needs clearer conceptualization and greater elaboration. The importance of eating routines as a phenomenon and process in food choice emerged in a study of situational aspects of food choice conducted with working adults living in a semi-rural area of Upstate New York. Study participants reported what, where, when, and with whom they ate in qualitative interviews conducted over seven consecutive days. Analysis of these data led Bisogni, Falk, Madore, Blake, Jastran, Sobal & Devine (2007) to propose a framework for characterizing eating episodes that would encompass the situationality of eating as viewed from people's perspectives and recognize that eating episodes are more than simply food and beverage consumption. The episode framework includes eight inter-connected dimensions (food/drink, time, location, activities, social setting, mental processes, physical condition, recurrence), each of which can have multiple features. The dimension of recurrence represents the repetition that may occur across multiple episodes in varying dimensions (e.g. same food, same location, same people, same activities) and the frequency with which this repetition occurs. In that study, participants often volunteered the words “routine”, “pattern”, “usual”, “habit”, “ritual,” and “regular schedule” to describe and emphasize their repetitive eating practices and situations. For example, when one participant was asked whether she called a particular reoccurring meal her breakfast or her break she responded, “I just call it my normal routine.” These adults used traditional meal labels (e.g. “breakfast,” “lunch,” “dinner”) to describe their routine eating practices, but also used uniquely constructed labels for their repetitive practices (e.g. “my little pick me up”) and adjusted meal hours and social settings to their work schedules and family demands (Bisogni et al 2007). Participants also had well established scripts for evening meals that suited their circumstances (Blake et al., 2008).

Given the apparent importance of routines to these participants and the need to understand repetitive eating practices at a time when traditional meal practices are changing, we sought to gain conceptual understanding of eating routines from this rich data set (Bisogni et al., 2007). We examined which kinds of eating routines operate and how people experience these routines.

Methods

Twenty-one men and twenty one women, working in non-managerial, non-professional positions provided multiple types of data about their food choices that were collected over 9 different contacts with the same interviewer (3 face-to-face and 6 telephone interviews). At the first in-person contact, participants completed a questionnaire about their demographic characteristics and a food frequency questionnaire. They also answered open-ended questions about their food preferences and routines and completed the first of seven 24-hr qualitative recalls of eating and drinking events. For the next six days, interviewers telephoned participants and completed 24-hr qualitative recalls of food choice events. The daily interview protocol for the 24-hr recall of food choice episodes was adapted from the multiple pass approach to the 24-hour recall (Guenther, Kott, & Carriquiry, 1997). In each recall, participants reported about the previous day's eating, first by quickly recalling all food consumed, then reviewing the day with details about each eating episode, and finally verifying the interviewer's summary of eating for the day. Reviewing the previous day multiple times enhanced recall of events and information that may be forgotten or omitted in one quick summary of the day. Questions such as “what was the first time you had anything to eat or drink yesterday?” were used, rather than questions using traditional meal labels, such as “What did you have for breakfast yesterday?” Details about each eating episode included the foods/drinks consumed, location, the persons present, where the food/drink was purchased/acquired, the participant's feelings in that situation, other activities, and the role of the participant in the eating situation. In recalling eating episodes from the previous day, participants also quite often discussed work and family schedules that were connected to their eating.

The eighth contact with participants was a 60-120 minute interview about common eating situations, people present in eating episodes, and foods. Before the ninth contact, the research team read the verbatim transcripts from the 7 consecutive day recalls and summarized the participant's eating practices over the 7 days. The team also identified areas for further questioning to understand the participant's eating practices. The ninth contact was an in-person interview in which the interviewer reviewed and verified the summary with participant and asked additional questions about the participant's eating practices.

With nine contacts with the same interviewer, the participant typically had developed strong rapport, making it comfortable for them to discuss their eating patterns and fostered discussion of personal food choice values and reasons for food behaviors. The open-ended, probing nature of all the interviews allowed the participant's personally relevant details of food related behavior to emerge.

The demanding nature of the 7 consecutive day recalls required that participants have access to a telephone throughout the interview process. Each participant worked with only one interviewer, and the interviewer was flexible in scheduling the interviews according to the structures of participants' personal schedules. For example, some participants needed a call late at night and others who worked nights required a call early in the day. All interviews were audio recorded. The recordings were transcribed verbatim and then verified for accuracy by the interviewer. Field notes that were also taken by the interviewers after the 3 face-to-face interviews enhanced the data.

Participants were recruited through community agencies, employers, ads in local newspapers, and personal contacts. They were purposively sampled to vary in gender, age, occupation, and living situation. The methods for recruiting and collecting data from participants were approved by the University Institutional Review Board (IRB). Each participant signed a consent form prior to participating and receiving compensation.

The 21 men and 21 women were mostly white (86%) and ranged in age from 20 to 61 years. Their occupations included building and ground maintenance, office and administrative, sales, personal care and other service, transportation and moving, community and social services, and installation and repair. Participants' marital status included never married (38%), married (48%), and divorced or separated (14%). Half of participants reported having at least one child younger than 19 years living at home. High school/less than high school was reported as the highest level of education by about 29% of participants, and 61% indicated that they completed some college but did not hold 4-year degrees. Their annual household incomes ranged from less than $10,000 U.S. (12%) to more than $70,000 U.S. (7%), with 61% reporting household incomes less than $40,000 U.S. Participants varied in their responsibilities for household food management.

Interview transcripts from all 9 participant contacts were analyzed for eating routines using the constant comparative method (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Analysis considered participants' explicit recognition of eating routines in their daily lives (“that is always what I do”) as well as researchers' identification of repetitive dimensions of eating episodes in the data. Each interview was read and coded for routines and related themes. As new themes were noticed, all previous and subsequent interviews were searched for these emergent themes. Providing 7 consecutive days of eating information in the daily interviews encouraged participants to acknowledge and discuss routine aspects of their eating behavior. Data quality was improved by prolonged engagement with participants. Data analysis was enhanced by interviewer participation in analysis and peer review as study findings were shared and discussed with other researchers. Each participant's data was reviewed by the entire research team prior to final interviews so that team assessments could be clarified and appropriate questions added to guide the final interview. Further, findings were also presented and challenged by further peer review with university faculty and students working on related issues (Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

Results

Participants in this study provided rich data about eating routines. They varied in the number and complexity of their routines. Breakfast, lunch, and dinner were common meal pattern labels used by many participants, but the dimensions of those meals varied across participants and the eating routines reported by participants extended beyond these meals. The following sections report the main themes emerging from analysis of the routines described by study participants.

What are eating routines?

When looking at single eating episodes, participants' descriptions of their eating routines included both repetition in foods and drinks consumed and repetition in contexts for consumption. Participants presented their eating episodes as having many dimensions, including food, time, location, activity, social setting, mental processes and physical condition. From this perspective, eating routines involved repetition in a cluster of dimensions of an eating episode that could involve a few of these dimensions or many of them. For example, a routine of “coffee in the morning” combines food/drink (coffee) and time (morning), but the location, social setting, activity, mental processes, and physical condition could vary. A more detailed routine was presented by a participant who reported “in the summer (time) I live on salads (food) because the trailer (location) is ungodly hot (physical condition).” Table 1 presents examples of combinations of dimensions that were represented in routines described by these participants.

Table 1. Dimensions of eating episodes that recur in routines.

| Food, Time, Recurrence |

▪ “… then at night (time) I had a bowl of ice cream (food), which you'll probably hear every day (recurrence) … it's habitual … a typical thing to me.” |

| Food, Social Setting, Mental Processes (goal), Recurrence | ▪ “[when my husband plays golf with my brother-in-law] I'll invite my sister over (social setting) … if I want to make like stuffed peppers (food). And he [husband] doesn't like those. So … we'll fix something for the kids (social setting), but then we'll make stuffed peppers (food) … because the kids (social setting) won't eat that either.” |

| Location, Social Setting, |

▪ “[in the break room at work] (location) mostly everyone's (social setting) got their own set routine … that's your chair … [laughs].” |

| Time, Activity, Social Setting |

▪ “That's an everyday routine [for our family (social setting) breakfast] (time) just because The Wiggles (activity) are on from 8:30 to 9:30 (time).” |

| Food, Time, Social Setting |

▪ “Like Wednesday nights (time) I get take out (food) for the girls [and her husband] (social setting) because that's the night I come home and change clothes real quick and go skiing.” |

| Food, Time, Activity, Social Setting, Location |

▪ “While the kids are in the back watching their cartoons (time) … I'm out here (location, social setting) watching my soap (activity) … and eating what they can't have … ice cream (food) … they can't have it because … one has asthma and one is lactose intolerant.” |

| Food, Time, Location, Recurrence |

▪ “I eat the same thing in here [restaurant] (location) every day (recurrence) … I get two eggs, medium. I get whole wheat toast. I get home fries and coffee and water (food). Every day of the [work] week (recurrence).” |

| Food, Time, Activity |

▪ “That's a normal routine. Come home from bible study (activity) [Wednesday nights (time)] and sort of have the second phase of dinner (food).” |

| Food, Time, Mental Processes (goal), Physical Conditions |

▪ “Because I'm working … late at night (time), it's [work meal] something (food) that's not going to be like heavy or greasy … But just something that's going to … fill me up (physical condition, mental processes). Nothing like … fast food (food) or anything that's greasy.” |

Eating routines can also be described in terms of the nature of repetition or the circumstances that initiated this familiar combination of eating and context. The repetition could be based on chronological time (e.g. “each morning,” “once a week”) or recur because the person's daily life presented another repeating dimension that triggered the familiar eating episode. For example, the routine could be initiated by social setting (“when we get together with friends, we always go out to eat”), place (“when I go to the fair I always have a cheeseburger”), or physical condition (“I only eat when I'm hungry”). Often, a traditional meal label (e.g. dinner) was used in describing a particular routine but recurring context dimensions and specific behaviors set the routine apart from just another “dinner.”

When looking across days and weeks, eating routines involved regularity in sequence. Participants described distinct patterns of eating episodes that were specific to a 24-hour period (work days, non-work days, days when I have evening hours) or other personally defined time periods (“summer when the kids are home from school,” “weeks when I am working overtime,” or “times when my husband is not on his truck trips.”)

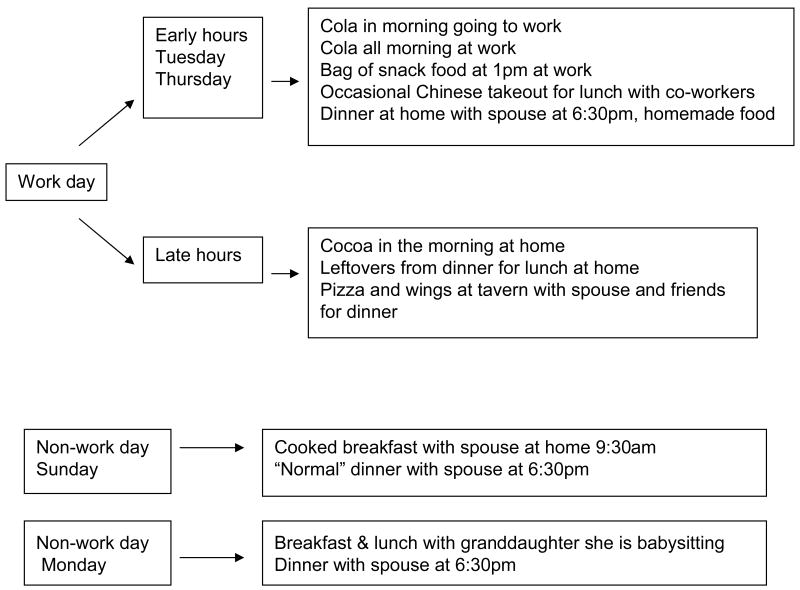

A case example (Figure 1) illustrates the routine sequences of eating across the week described by Amy (a pseudonym), a hairdresser who lived with her spouse and was the household food manager. Her patterns of eating and drinking episodes varied with her work schedule. On days when she worked an early schedule (time), she routinely drank cola (food) at work (location) until mid-day (time) when she ate some sort of bagged snack (food) she often purchased on her way to work. Amy continued drinking cola until she had dinner with her husband (social setting) around 6:00 in the evening (time). On the one day each week that she began work later (time), she had time for morning hot cocoa and then ate leftovers (food) at home (location). She drank cola (food) on her way into work (location- car) and throughout her work day, but instead of having dinner at home, she routinely met her husband at a local tavern (location) and they had pizza and wings (food) for dinner there with friends (social setting). Even though she ate a meal called “dinner” each evening, the context dimensions provided by different days of the week created different dinner routines. On days off that fell on weekends (time), Amy and her husband cooked a big hot breakfast (food) together (social setting) and then ate dinner together (social setting) later. On Mondays (time) she did not work and cared for her granddaughter and had breakfast and lunch with the child (social setting) at home (location). This example reveals how her work schedule and the days of the week set the dimensions of location, social context, and food for Amy's meals and helped create her routines for different days.

Figure 1.

Case example of routine sequences of eating episodes for specified time periods described by a hairdresser

The number and arrangement of eating episodes on work and school days were often part of participants' routines. A few people routinely avoided eating any food at work, their routines instead consisted of beverages including coffee, soft drinks, or juice throughout every workday. For some participants, their routine was eating nothing at work and waiting to have their one main meal a day at home. One woman with little structure to her work day ate at various times, but it was a routine for her to always eat lunch when she felt hungry.

“And I've also been known to eat my lunch at like 10:00….Just because I don't have a set time that I go to lunch. … So I just eat when I need to.”

Some participants routinely skipped certain meals, especially a meal in the morning they usually referred to as breakfast. Others had a two meal a day routine that included eating breakfast and dinner but no midday meal.

What are the characteristics of eating routines?

Participants described four common characteristics of their eating routines. 1) Eating routines were embedded in work and family schedules; 2) they reflected personal food choice values; 3) they were adaptable (i.e. stable yet able to change); and 4) people were reflective about their routines and derived identities from them.

1) Eating routines were embedded in work and family schedules

Work and family schedules often set the dimensions of the eating episodes that would repeat, such as food/drink, time, location, activities, social setting, mental processes, and physical condition. For example, participants explained how their overall schedules often dictated where they would be eating, who else would be there, what activities would be going on during, before, and after eating, and both the chronological time and amount of time available for food acquisition and eating. People reported that their eating routines were coordinated with the other recurring aspects of their lives including work (e.g. “coffee before work”), household responsibilities (e.g. “just after I cut the grass”), and recreation (e.g. “popcorn when we watch a movie”).

For participants who had spouses or families, the schedules of each family member's obligations (both work and non-work) typically shaped their eating routines. One woman explained how the children's swim lessons influenced their evening meal.

“We'll do that after swim lessons. Pick something up [from a fast food place] on the way home…Once a week….Tuesdays are swim.”

Participants described the challenge of coordinating each family member's schedules into a shared food routine, often with the goal of eating meals together. One mother explained,

“…now we're doing football‥ So we feed the kids earlier …practice is from 6 to 8 ‥before where mealtime would be like 5, 5:30, now we have to feed them like at 4:30, 5:00 to get them … ready to go out … to go to practice. …We figured it out last year. Because we were juggling football … this activity, that activity. And I finally said, ‘Okay. This year we're gonna have a schedule because … 8 o'clock at night I'm getting home feeding kids!”

Some parents of young children found it simplest to eat at times that were best for their children. One mother reported “it's easier to convert to their (children's eating) schedule.”

Work shaped eating routines in many ways. Participants explained that work schedules, whether fixed or variable, dictated the regularity of eating episodes. One woman's routine for family meals was based on her changing work hours.

“…it [a family meal] depends on the … day of the week because my [work] week is different. [At]… the end of the week and the weekends I'm home for dinner, not necessarily breakfast. Whereas the beginning of the week I'm home for breakfast and not at all [for] dinner. It depends on the time of day… and what day it is.”

The nature of participants' occupations and work activities also shaped eating routines. A man whose current eating routine at work involved frequently skipping meals described how the structure and social expectations of a previous job encouraged a more regular eating routine

“…in my former job I was more structured. [I] actually sat down and ate breakfast, ate lunch. Part of it was I was in the food service field and it made sense to eat at structured times. I didn't skip meals as much.”

Regularly scheduled paydays also were a way that work influenced eating routines. One person described routinely eating more for lunch on paydays because he would have more money to spend.

“…the only difference is I get more [food]. Like … this week I've been eating three hotdogs at break. Tomorrow is payday - I may get four or five.”

For some participants, social aspects of the work setting contributed to eating routines. The eating routine of a man who shared coffee with his co-workers at the start of the work shift was shaped by social expectations and work role benefits that reinforced the routine.

“It's kind of a routine [drinking coffee together] … there were other guys all sitting around. We were all talking about the jobs that they were doing that day… passing along information and stuff.”

The transit time between work, family, and recreation activities was the routine time that some participants relied on for eating. Participants who had early work hours commonly reported “picking something up on the way to work” or eating in the car en route to the next activity. One participant who traveled from one city to another with her boss for work explained their routine as, “We always eat while we drive [to our next job].”

Participants indicated that their eating routines were also shaped by the regularity of foods available to them in different settings. Access to any food, and particularly preferred foods, changed in regular ways in restaurants, relative's houses, at work, and in recreational settings. People planned eating routines around food availability. For example, one man reported regularly eating available leftovers at the location of his ex-wife's house when he was there after work to spend time with his children. Because the boss's mother brought in home baked items to work every Monday, one woman routinely indulged in them on that day. Being in the vicinity of a favorite food source often routinely triggered eating that food. One woman explained,

“Well she [my daughter] likes her little candy cigarettes and that's the only place that has them … is out there… It's kind of like a little tradition … [to] stop … there.”

Eating routines also provided structure to people's lives. Eating routines influenced how other responsibilities were executed. One woman who had recently begun working independently as a house cleaner said her life lacked the defined work hours and mealtimes that her previous job dictated. She described how she tried to create meal routines to give her days some structure “because I have such weird jobs [and hours], I do get kind of like a regular pattern [with meals].” Eating routines that were tied to the other routines in life such as work breaks, driving to and from work, or other activities seemed to be reinforced by the benefits and momentum of those activities and had increased durability. Participants explained that small changes in routines occurred as their circumstances shifted and the need arose to coordinate eating with new daily routines, places, or people. For example, one woman described changing her morning eating routine when she got a new job closer to home and wistfully recalled how she managed it previously because of a long commute.

“I was better when … I had an hour drive… I'd have two English muffins and my tea … now I'm just getting the tea because the drive is shorter … So I haven't gotten to the point of getting that English muffin routine going again.”

Some participants described the purpose of a routine as knowing that the routine would happen. One participant who started work late in the day described a routine breakfast as his main meal for interacting with his spouse and his most relaxed daily meal.

“It's just the ritual of it. Just the getting up in the morning … having time to sort of just orient and stuff like that.”

Participants explained that they were attached to eating routines that became part of their daily regimen. Changes in routines appeared to require time for adjustment. One participant who had just altered his work hours by starting a half hour earlier in the morning said of his morning routine,

“I looked at the clock. I said, ‘Man. Am I gonna make it [to work] if I stop for the coffee?’ … It's gonna take me probably a couple weeks to figure out the [new] pattern.”

2) Eating routines reflected personal food choice values

Participants indicated that they constructed eating routines to accomplish goals that were important to them. They explained that their routines helped them achieve food choice values such as enjoying taste preferences, enacting family or ethnic traditions, or saving money or time. For example, a father described how he was able to satisfy his taste preferences by having a routine for eating foods that he liked but his children disliked.

“… if it's something like I really want, I will make it to bring for lunch, or make it when the boys aren't there.”

One man described how he saved time at breakfast

“For breakfast. Yeah. That is pretty typical … when I eat my oatmeal I usually stand up because I eat it in a hurry so I can rush out the door and go to work.”

Health concerns and physical performance were other reasons some participants provided for constructing repetitive eating routines. Participants' health concerns included managing high blood sugar, losing weight, and taking medications. A person who was trying to eat more healthfully described how she slightly changed an existing routine.

“And I was trying to avoid the cookies is the biggest reason I started [eating my lunch] early.”

A body builder had unique eating routines that he constructed to meet his personal goals.

“Where now I'm pretty much set on a schedule, okay? I've got to have my breakfast in by 10 o'clock. Because by 12:30 … I'm taking a supplement … So I'm like on a schedule where I'm eating every hour and a half to two hours …”

A commonly reported goal was to create family meals, which often included routine foods (often home made), routine eating places (home, often around the table), and routine atmosphere (relaxed, everyone happy and satisfied). One woman explained how her family constructed a dinner routine for Sunday nights (time) that focused on “just watching TV, talking and cuddling. We all just cuddled on the couch as a family (social setting). That's our regular Sunday night routine.”

A need for relaxation was a frequently expressed goal as participants described their eating routines. Relaxing in the evening with television and a meal, snack, or drink was typical among these participants. Some parents described being more relaxed when eating meals apart from their young children, such as a person who said “I feed the kids and I try to eat when they're sleeping.” One mother of four young children explained that arranging for the kids to be asleep while she ate was the most important aspect of her eating routine.

Eating routines on weekends or non-work days often meant enjoying more relaxed meals in general. One woman explained,

“Weekend meals are much different than weekday meals. Actually weekend meals I'm more relaxed and I can take time to prepare ‘em. I'm not in a hurry. I'm not going anywheres.”

Break time at work was a scheduled time of day for some participants that often included both relaxation and eating. For example, while most people ate at work with co-workers, one man who described his need for a respite from his work ate lunch and snacks alone as an eating routine. Another man went home to have lunch with his wife and watch television for his relaxing food time.

Participants had routines for treating themselves, and these were often a reflection of using routines that involved balancing of food choice values over time. For example, people who used restrictive routines to meet health goals but did not meet their taste preferences often had a routine of indulging themselves on certain days or in particular contexts. It appeared that the indulgent treat routine made it possible to stick to the more restrictive everyday routine. Many participants routinely indulged in take-out food or restaurant meals on Friday evenings, declaring “Friday nights we go out.”

3) Eating routines were adaptable: stable but able to change

Participants explained that their eating routines had evolved as the best fit for the constraints and opportunities to attain food choice values in daily life. Following routines provided participants the predictability of achieving their food choice values, helped them feel in control of the short and long-term consequences of eating, and prevented them from finding themselves in situations that would conflict with their intentions. For example, a routine of exclusively eating cheeseburgers at local fairs made life easier and more secure for one man who called them “Just a safe thing to eat. You can't mess up a cheeseburger.”

Routines persisted if they seemed to work well but were also dynamic, changing over time as circumstances and food related values changed. For example, participants who were responsible for cooking a meal for a child developed eating routines based on this responsibility. The developmental changes in their children meant changes in eating routines. One participant who described an erratic eating routine foresaw a change when her son began school.

“… I'm not used to structure. I'm used to being able to come and go and do what I want when I need to do it. I'm going to have to be home, get him [her son] fed by a certain time, getting him bathed by 8 and then [to] bed by 8:30.”

Another example of how a parent's routine responded to the changing needs of his child is a father who hoped to share more meals with his 22 year-old daughter. He said,

“I'm willing to change our eating schedule if it would accommodate eating with [my daughter]… She has weird hours and she's in college so we're trying to do that.”

Disruptions of family member's activity routines could change eating routines. For example, when one participant's son was away at camp, meal routines became more haphazard. Another woman was married to a long-distance truck driver whose work schedule influenced family eating routines. When he came home, his presence changed all household schedules including mealtimes, which were routine and predictable in his absence.

4) People were reflective about their eating routines and derived identities from their routines

Participants reflected upon and reacted to their eating routines in different ways. One type of reaction was boredom with living with an unchanging routine. Participants described having the “same old routine” or lamented “It's so routine, it's pathetic.”

Participants also viewed routines as positive because they simplified their eating decisions and providing predictability. One man explained

“I know in the morning what I'm going to get so I'm not, you know, taking time to think ‘What's for breakfast?’ It's already there in my head.”

The comfort that routines provided was often viewed positively by participants. One person explained, “I'm comfortable…it's a routine. You don't want to change the routine.” Others also described their aversion to changing the routines “I don't like it when things get changed … I kind of like the same routine.” One woman who was returning from a vacation where they ate “weird meals” described the comfort afforded by eating routines,

“it's getting back to a routine … we were like ‘Okay. Yeah! We're finally home and we're getting settled.’ ”

Another man whose wife and daughter were away on a trip leaving him to eat alone explained how this social disruption caused his more erratic eating behavior. “It was just not the normal routine … you get out of that routine and … just off balance.”

People's strong ideas about what was “normal” shaped eating routines that fit those expectations. One participant believed that snacking was not healthy and ate only three very regular meals daily, with no eating or drinking in-between. Participants expressed norms related to the importance of breakfast, meal size at certain times of day, having meals as a family or eating meals together, and foods appropriate to different times of day. As one person explained, “I basically stick to stereotyped categories … If it's breakfast, you eat cereal, toast.”

Even ways of eating that might look unstructured to an outside observer were sometimes perceived as quite structured and familiar to the individual living with them. One person described his eating in the following way:

“…it's stable. Yeah it's… probably the most stable thing I do. … As crazy and unstructured as it is to everybody else, it's the most structured thing I do.”

Sometimes participants described eating behavior that was consistent but said, “This isn't typical. I mean it's typical for the past year, but it's not typical,” indicating that the routine felt temporary and undesirable in some way, with a sense or desire that soon they would revert back or convert to an earlier or different eating routine that felt more comfortable.

Occasional deviations from typical routines were acknowledged and explained. If the participant felt their daily eating routine was generally meeting an important food choice value such as healthy eating, a change from the routine now and then was not a source of guilt.

“It happens. I ate something I shouldn't have ate for two or three days in a row… I know that little blip isn't going to harm me because I'll get back to the other [healthy] routine…It's not like [I]…do it on a very daily basis.”

Some participants described having identities based on their eating routines. Identities related to eating routines were often reported when participants perceived that their ways of eating were in contrast to cultural norms. For example, participants reported, “I'm not a meal eater” or “I'm always eating….I've always been a grazer.” Other participants elaborated about routines and identities more fully.

“I'm not a standard eater. I'm not a ritualized eater … you know, Will [boss] has to eat at 6:00 or he just thinks he's going to die you know. (laughs) I eat from 4, through 6, into 8, you know. No. I am not a ritualistic eater.”

“I'm a whatever I want eater. I'm a sometimes eater. Right now today, yesterday and tomorrow I'm a picky but whatever I want to eat eater…So I'm an eat as I please eater. ”

Meal irregularity was the routine for certain individuals. A single father stated, “No. I don't [eat regular meals].” A single mother with few obligations in her family life explained how she differed from her friends, situating her own routines by comparing them to routines of others she knew,

“Well they [friends] usually have a set dinner time, I don't. It's whenever you're hungry. And they usually create a meal for their family because they usually have their spouse home and other kids and I don't. It's just me and my son. So there's a big difference.”

Another participant said,

“I don't eat on schedule. … Like I don't eat… at 9:00 am exactly I have this. I'm not a scheduled eater. I'm not a typical eater, I guess I would say…”

Summary of results

Study participants reported many different kinds of eating routines that could be analyzed and characterized in different ways. At the episode level of analysis, a routine could be examined according to the nature of the repetition and described from the perspective of the multi-dimensional framework for eating/drinking episodes using the dimensions of food/drink, time, activity, location, mental processes, physical condition, and/or social setting. Participants also described eating routines as involving sequences of eating/drinking episodes, a second way that routines could be examined. Participants explained that their eating routines (either individual or sequences) were embedded in their work and family schedules and based on their personal food choice values. Participants reported that their eating routines were developed as “best-fit” solutions to their goals in different settings and that they modified their routines when circumstances required a new best fit. Finally, participants in this study reflected upon their eating routines, evaluating them from different perspectives and deriving personal identities from them.

Discussion

This analysis sought to develop a conceptual understanding of eating routines using a unique data set comprised of multiple, situational recalls of eating episodes from adults that were supplemented with additional qualitative interviews with each participant. The findings provided insights for how researchers and practitioners might conceptualize eating routines for research and health promotion.

The concept of eating routines and their analysis

This study proposes that “eating routines” is a useful concept for capturing the different ways in which people construct regularities in eating practices, including but not limited to the traditional 3 meal-a-day pattern. The findings illustrate eating routines as rich phenomena that can be analyzed at multiple levels and can account for context as well as food and beverage consumption, allowing the examination of eating patterns from different perspectives and for different purposes. At the episode level (Bisogni et al., 2007), eating routines can be designated as predictable combinations of consumption with various aspects of the context. The dimensions of eating episodes proposed by Bisogni et al. (2007) provide a way to identify and organize the many different attributes of eating routines.

When considering routines as the pattern of eating episodes over a period of time (e.g. day or week), a routine can be described in terms of the number and sequence of episodes and/or how the episodes relate to a person's overall schedule and contexts for daily living (Goode, Curtis & Theophano, 1984). Diagramming eating routines shows how individual eating episodes are linked to each other (e.g. “no lunch, big dinner”). Routines emphasize the personally constructed ways that people regularize dietary behaviors and show how people may have different types of “typical days” of dietary intake depending upon schedule, home, or work responsibilities. Denham (2002) supports the idea that time is a critical influence on the creation and enactment of routines, with time of day, day of the week, seasons of year and developmental stages in the individual and the family contributing to and shaping routines.

The concept of eating routines is a useful way to capture the repetition in ways of eating that many people experience that is not dependent upon traditional meal patterns or meal labels (i.e. breakfast, lunch, dinner, snacks). Although the traditional 3 meal-a-day pattern and labels were part of participants' experiences and often used as the reference point for describing their ways of eating, participants reported different personal routines for these meals and routines for eating outside traditional meals. As traditional meal patterns have moved toward individualized ways of eating for many people (Sobal, Bisogni, Devine, & Jastran, 2006; Bove, Sobal, & Rauschenbach, 2003), researchers need ways to identify, characterize, and understand the repetition without being limited to using traditional meal labels as the standard of reference. While not the final word on representing these transitions in eating practices, this study proposes eating routines and their dimensions as useful ways to dissect, represent, and understand these changing patterns.

Operation of eating routines in people's lives

These findings illustrate how people construct eating routines as a result of both the structure of their lives and the agency that they bring to life (Ilmonen, 2001; Sztompka, 1994). These ideas are also consistent with the work of Ludwig (1997) who studied routines for daily life in elderly people. From a structural perspective, many aspects of participants' eating routines were established by their home conditions, work conditions, family responsibilities, geographic location, food availability, culture, and resources related to time, money, and available human capital for meal preparation (Devine, Jastran, Jabs, Wethington, Farrell, & Bisogni, 2006; Jabs, Devine, Bisogni, Farrell, Jastran, & Wethington, 2007; Beardsworth & Keil, 1997). The highly structured and ritualized nature of time in the daily, weekly and yearly patterns of home life has been emphasized by Straw and Elliott (1986). Other researchers have discussed the ways employment structures time for home life (Bianchi, 2000) and for food (Devine et al., 2003). These structural aspects of people's lives shape many dimensions of eating episodes including location, activities, time, mental processes, physical condition, social setting, and food (Ilmonen, 2001).

From an agentic perspective (Bandura, 2001), participants explained how eating routines reflected their food choice values and ideals for eating within the constraints set by the structures of their lives. Participants were able to exert control over some dimensions of eating episodes and the patterns of episodes. For example, a person might be at work but could choose the place to eat as well as whether or not to eat alone or with others, a person could eat at home but adjust their own meal time relative to their children's, or a person's meal could occur during work hours, but the person could choose the source of their food (home vs work) based on the perceived satisfaction of the foods available at the workplace.

People also derive models for behavior and decision making from the culture in which they live (cultural structures) (Bourdieu, 1984) and these norms can guide eating routines. Sometimes a routine was a “best fit” solution and other times the routine was the way a person thought they “should” do things. Most of the time, participants appeared to be seeking a balance between their ideals and realities as they designed eating systems and routines that worked for their unique situations.

The findings that eating routines also structured daily life are consistent with prior work that reports how regular eating practices enhance the quality of life and health for individuals and families by providing predictability and stability (Denham, 2003; Wolin & Bennett, 1984; Fiese, Foley & Spagnola, 2006). However, stability in eating practices has typically been described in terms of regular, traditional meals, yet this norm is not realistic for many people given their work and home responsibilities. The concept of eating routines emphasizes the regularity and predictability that a person constructs within their circumstances rather than whether or not a person achieves a culturally prescribed set of meals. In this way, the idea of eating routines opens the opportunity to think about other non-traditional ways to achieve this stability and predictability, such as eating out on Friday nights with family.

The stability of eating routines results from their development and adaptation over time as “best-fit” solutions to common eating situations and value conflicts. Being “best fit” solutions helps explain why routines are often hard to change. Predictable routines allow daily life to progress smoothly and satisfactorily, consistent with the view of Gallimore and Lopez (2002) that daily routines can be as “familiar as an old glove.” These finely tuned solutions reduced the time and stress involved in making daily decisions about the details of eating, and time scarcity and stress are issues that many employed workers face (Jabs et al., 2007).

The flexibility and adaptability that participants reported in the ways that they adjusted their eating practices to the other demands in life is readily captured in the concept of eating routines. For many participants, eating routines were always works in progress, subject to modification as their work and/or family situations changed. Zisburg et al. (2007) suggest that routines may fulfill a role in understanding adaptation to environmental demands because routine creates order and uniformity and helps in making adjustments to changing conditions.

The need for flexibility and adaptability in food practices for workers and employed parents has been emphasized by other researchers and supports the experiences of many participants in this study (Moen & Wethington, 1992). The conceptualization of revising or constructing new eating routines as circumstances change is more neutral and less value laden than are deviations from normative ways of eating such as “missing lunch” on certain days or “making a dinner that is too late.” Using the perspective of eating routines, the emphasis can be on ways of eating that work for a person's and for the family's social, emotional, and physical well being rather than whether or not a particular norm or ideal has been achieved. The concept of eating routines allows for the identification and understanding of eating realities rather than idealized eating patterns.

In this study, participants were quite conscious of their repetitive eating patterns because they completed 24-hour recalls over 7 consecutive days. This heightened consciousness led these participants to comment about and account for the ways that they ate. The awareness that participants expressed about their typical ways of eating, however, suggests that people self-monitor and have a sense of when they are behaving in comfortable and familiar ways.

The strong involvement of norms in participants' evaluations of their eating routines is consistent with the view that culture, class and lifecourse experiences play a crucial role in influencing what people believe their routines ought to be, acting as mirrors of cultural and societal values and structures (Daly, 1996; Beardsworth & Keil, 1997; Bourdieu, 1984). Gallimore & Lopez (2002) also identify the “ecological-cultural” surroundings as providing obstacles to changing routines for “even the most determined efforts.”

The link between identities and routines that participants reported is consistent with the mutual shaping nature of eating and identity (Bisogni, Connors, Devine, & Sobal, 2002). As individual eating episodes reflect personal values and priorities, the consistency of these values promotes routine eating behavior, which, in turn, contributes to developing stronger identities. This link is further supported by the work of Zisburg et al. (2007) that emphasizes how routines organize the timing, duration and order of activities and are observable behavior patterns that “comprise the individual's world, lifestyle and even identity.” Charmaz (2002) noted that the self is closely tied to habitual self-definitions and ways of viewing oneself that can be threatened by attempting new daily routines. This connection to identity may help explain why eating routines are difficult to change.

Among the study participants were people who did not have extensive or complex eating routines. Not all people desired routines. Reich and Zautra (1991) defined the psychological trait of routinization as the extent to which people are “motivated to maintain the daily events of their lives in relatively unchanging and orderly patterns of regularity.” Thus, eating routines were rare and seen as undesirable for only a few informants, which highlights the substantial role of routines for most participants. Study participants had a measure of organization and stability in their lives that allowed them to be in contact with an interviewer over the course of several weeks, and their reports of eating routines may be different from other working adults living less organized lives.

Limitations

In addition to the limitations of a small, non-representative sample of working adults in one location, the people who volunteered for this study had to have a certain level of stability and organization in their lives to complete this intensive study. The eating practices of working adults living less stable and organized lives may present different information related to eating routines.

The eating routines identified in this study did not distinguish between more automatic behaviors, similar to Clark's (2000) view of “habits” as less conscious, repetitive behaviors compared to “routines,” which are more conscious. The multi-day conversations about their eating episodes and follow-up interviews heightened participants' awareness of some of these automatic behaviors. Repetition in eating practices may go unnoticed by individuals who are not prompted to think about it.

This analysis considered all regularities in eating as “routines” and did not distinguish between routines and rituals as some other researchers have done (Fiese, Hooker, Kotary, & Schwagler, 1993; Fiese, Tomcho, Douglas, Josephs, Poltrock, & Baker, 2002; Marshall, 2005). For example, in studies of family routines, Fiese et al. (2002) describe routines as observable repeated behavior that is task oriented and reserves the term rituals for activities that promote group identity and have symbolic meaning. This analysis did not consider which of the regularities in eating episodes or patterns of episodes had deep meaning for participants versus which ones were simply functional in their lives. Future investigations of this distinction may be useful to further understand eating behaviors.

Finally, this analysis did not attempt to find associations between foods consumed and participants' eating routines. Whereas participants may have been somewhat biased or sensitized to food choice and eating by repetitive, daily contact with interviewers, the study was presented as seeking to understand situational eating and never portrayed to participants as a nutrition or health promotion study.

Implications and Applications

This study of eating routines is a beginning for examining repetition in eating practices in a way that is open to broadly consider how people construct food choice in contemporary society. The findings need to be extended and elaborated upon with studies of people with different characteristics and living in different settings, regions, and cultures.

This research advances the Food Choice Process Model (Furst et al., 1996; Falk et al., 1996; Connors et al., 2001; Sobal et al., 2006) by further developing the concept of routines in the personal food system, the cognitive processes through which people construct food choice. The concept of eating routines highlights the situational aspects of eating as routines occur in contexts and people clearly have repeating contexts for eating with matching situation-specific routines. The conceptual frameworks used in this study to represent routines as repetition of individual episodes and patterns of different episodes may be useful to other researchers who wish to characterize the ways that people eat and link these to dietary intake or health outcomes.

The conceptualization of routines in this study emphasizes the importance of context and structure in a person's regular eating practices. This emphasis is well suited to studying food choices because contemporary approaches to health promotion emphasize social and physical environmental influences on nutrition and health behaviors (French, Story, & Jeffery, 2001). The study findings do suggest, however, that people may exercise their agency to respond to environmental factors in individual ways by constructing their own eating routines. As evidenced by the Food Choice Process Model, contextual factors are one of many influences on food behavior.

The concept of eating routines allows for individualization to be considered because it emphasizes a holistic and integrated view of the consumption behavior and consumption context and also a view of the way that people construct connections among their eating episodes in daily patterns. As health promotion interventions pay more attention to modifying environments with a view to influencing eating behaviors (French et al., 2001), it is important to recognize the individual ways that people may respond to changes in the environment. Given that dietary guidelines suggest that people have both lower and upper limits to their intake of macro and micronutrients, models for representing the contexts and patterns of eating episodes helps identify and understand how people distribute intake behavior within their daily and weekly lives.

Eating routines are crafted and “owned” by people as they choose among possible options in their recurrent eating situations and fine tune the solutions that work for them. In order to change their behaviors in accord with health recommendations, people must change their routines. Betsch, Haberstroh, Molter, & Glockner (2004) described the exceptional durability of routines and the tendency of people trying to change a routine to fall back into an old routine when under stress or time pressure. Theories of nutrition counseling emphasize that a holistic consideration of eating episodes throughout the day (time, place, mood, social details) is necessary to understand eating patterns because increased awareness of the environmental stimuli for eating and the moods surrounding eating events are first steps in re-structuring eating routines (Holli & Calabrese, 1998). Whereas the term eating routines is not typically used in nutrition practice, Gallimore and Lopez (2002) use “routines” as they describe how daily practices are both constrained and enabled by the eco-cultural context. They suggest that as clients explain their routines, health practitioners are able to learn much about what the “daily routine represents, what it reflects and what accommodations are made to sustain it” (Gallimore & Lopez, 2002). They also propose that clinicians working with people who are adapting to new health problems must understand the need to help fit interventions into client's existing routines.

The concept of eating routines emphasizes the clients' roles in directing how they balance structure and agency (or constraints and choice) to perform the necessary task of nourishing themselves or others and fulfilling their other needs through food consumption. The concept of eating routines encourages a view of nutrition behaviors that takes into account how people's eating practices are intertwined and embedded with other parts of their lives and also result from their needs for predictability and stability.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by funds from the Cornell University Agricultural Experiment Station, USDA-CREES, Hatch Project #NYC399422 and NIH Training Grant #2 T32 DK07158-27. The authors thank Patrick Blake for his assistance with data collection.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bandura A. Social Cognitive Theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001;52:1–26. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargh JA, Barndollar K. Automaticity in action: The unconscious as repository of chronic goals and motives. In: Gollwitzer P, Bargh JA, editors. The psychology of action: Linking cognition and motivation to behavior. New York: Guilford Press; 1996. pp. 457–481. [Google Scholar]

- Beardsworth A, Keil T. Sociology on the menu: An invitation to the study of food and society. London: Routledge; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Becker MC. Organizational routines: a review of the literature. Industrial and Corporate Change. 2004;13(4):643–677. [Google Scholar]

- Betsch T, Fiedler K, Brinkmann J. Behavioral routines in decision making: The effects of novelty in task presentation and time pressure on routine maintenance and deviation. European Journal of Social Psychology. 1998;28:861–878. [Google Scholar]

- Betsch T, Haberstroh S, Molter B, Glockner A. “Oops, I did it again” - relapse errors in routinized decision making. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 2004;93(1):62–74. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi SM. Is anyone doing the housework? Trends in the gender division of household labor. Social Forces. 2000;79(1):191–228. [Google Scholar]

- Bisogni CA, Connors M, Devine C, Sobal J. Who we are and how we eat: A qualitative study of identities in food choice. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2002;34(3):128–139. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60082-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisogni CA, Falk LW, Madore E, Blake CE, Jastran M, Sobal J, Devine CM. Dimensions of everyday eating and drinking episodes. Appetite. 2007;48(2):218–231. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake CE, Bisogni CA, Sobal J, Jastran M, Devine CM. How adults construct evening meals: Scripts for food choice. Appetite. 2008;51 doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.05.062. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P. Distinction: A social critique of the judgment of taste. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Bove CF, Sobal J, Rauschenbach BS. Food choices among newly married couples: Convergence, conflict, individualism and projects. Appetite. 2003;40(1):25–41. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6663(02)00147-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. The self as habit: The reconstruction of self in chronic illness. The Occupational Therapy Journal of Research. 2002;22(Winter Supplement):31S–41S. [Google Scholar]

- Clark F. The concepts of habit and routine: A preliminary theoretical synthesis. The Occupational Therapy Journal of Research. 2000;20(Fall Supplement):123S–136S. [Google Scholar]

- Connors M, Bisogni C, Sobal J, Devine C. Managing values in personal food systems. Appetite. 2001;36(3):189–200. doi: 10.1006/appe.2001.0400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly KJ. Families & time: Keeping pace in a hurried culture. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Denham S. Family routines: A structural perspective for viewing family health. Advances in Nursing Science. 2002;24(4):60–74. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200206000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denham S. Relationships between family rituals, family routines, and health. Journal of Family Nursing. 2003;9(3):305–330. [Google Scholar]

- DeVault M. Feeding the family: The social organization of caring as gendered work. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Devine CM, Connors M, Sobal J, Bisogni CA. Sandwiching it in: Spillover of work onto food choices and family roles in low- and moderate-income urban households. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;56(3):617–630. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine CM, Jastran M, Jabs J, Wethington E, Farrell TJ, Bisogni CA. “A lot of sacrifices”: Work-family spillover and the food choice coping strategies of low-wage employed parents. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;63:2591–2603. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk LW, Bisogni CA, Sobal J. Food choice processes of older adults. Journal of Nutrition Education. 1996;28:257–265. [Google Scholar]

- Fiese BH, Foley KP, Spagnola M. Routine and ritual elements in family mealtimes: Contexts for child well-being and family identity. In: Larson RW, Wiley AR, Branscomb KR, editors. Family mealtime as a context of development and socialization. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2006. pp. 67–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiese BH, Hooker KA, Kotary L, Schwagler J. Family rituals in the early stages of parenthood. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1993;55(3):633–642. [Google Scholar]

- Fiese BH, Tomcho TJ, Douglas M, Josephs K, Poltrock S, Baker T. A review of 50 years of research on naturally occurring family routines and rituals: Cause for celebration? Journal of Family Psychology. 2002;16:381–390. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.16.4.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French SA, Story M, Jeffery RW. Environmental influences on eating and physical activity. Annual Review of Public Health. 2001;22:309–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.22.1.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furst T, Connors M, Bisogni C, Sobal J, Falk L. Food choice: A conceptual model of the process. Appetite. 1996;26:247–265. doi: 10.1006/appe.1996.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallimore R, Lopez EM. Everyday routines, human agency and eco-cultural context: Construction and maintenance of individual habits. The Occupational Therapy Journal of Research. 2002;22:70S–77S. [Google Scholar]

- Goode JG, Curtis K, Theophano J. Meal formats, meal cycles, and menu negotiation in the maintenance of an Italian-American community. In: Douglas M, editor. Food in the social order: Studies of food and festivities in three American communities. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1984. pp. 143–218. [Google Scholar]

- Guenther PM, Kott PS, Carriquiry AL. Development of an approach for estimating usual nutrient intake distributions at the population level. Journal of Nutrition. 1997;127:1106–1112. doi: 10.1093/jn/127.6.1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holli BB, Calabrese RJ. Communication and education skills for dietetics professionals. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ilmonen K. Sociology, consumption and routine. In: Gronow J, Warde A, editors. Ordinary consumption. London: Routledge; 2001. pp. 9–24. [Google Scholar]

- Jabs J, Devine CM, Bisogni CA, Farrell T, Jastran M, Wethington E. Trying to find the quickest way: Employed mothers' constructions of time for food. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2007;39(1):18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khare A, Inman JJ. Habitual behavior in American eating patterns: The role of meal occasions. Journal of Consumer Research. 2006;32(4):567–575. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall DW. Food as ritual, routine or convention. Consumption, Markets and Culture. 2005;8(1):69–85. [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig FM. How routine facilitates wellbeing in older women. Occupational Therapy International. 1997;4(3):213–228. [Google Scholar]

- Moen P, Wethington E. The concept of family adaptive strategies. Annual Review of Sociology. 1992;18:233. [Google Scholar]

- Ouellette JA, Wood W. Habit and intention in everyday life: The multiple processes by which past behavior predicts future behavior. Psychological Bulletin. 1998;124(1):54–74. [Google Scholar]

- Poulain JP. The contemporary diet in France: “De-structuration” or from commensalism to “vagabond feeding”. Appetite. 2002;39(1):43–55. doi: 10.1006/appe.2001.0461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich JW, Zautra A. Analyzing the trait of routinization in older adults. International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 1991;32:161–180. doi: 10.2190/4PKR-F87M-UXEQ-R5J2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snetselaar LG. Nutrition counseling skills for medical nutrition therapy. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen Publishers; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sobal J, Bisogni CA, Devine CM, Jastran M. A conceptual model of the food choice process over the life course. In: Shepherd R, Raats MM, editors. Psychology of food choice. Oxfordshire, UK: CABI Publishing; 2006. pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss AL, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 2nd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Straw P, Elliot B. Hidden rhythms: Hidden powers? Women and time in working-class culture. Life Stories/Recits de vie. 1986;2:34–47. [Google Scholar]

- Sztompka P. Agency and structure: Reorienting social theory. Langhorne, PA: Gordon and Breach; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Warde A. Convenience food: space and timing. British Food Journal. 1999;101(7):518–527. [Google Scholar]

- Warde A, Hetherington K. English households and routine food practices: A research note. The Sociological Review. 1994;42(4):758–778. [Google Scholar]

- Wolin S, Bennett L. Family rituals. Family Process. 1984;23:401–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1984.00401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zisberg A, Young HM, Schepp K, Zysberg L. A concept analysis of routine: Relevance to nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2007;57(4):442–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]