Abstract

Data from a nationally representative sample of private health plans reveal that special lifetime limits on behavioral health care are rare (used by 16% of products). However, most plans have special annual limits on behavioral health utilization; for example, 90% limit outpatient mental health and 93% limit outpatient substance abuse treatment. As a result, enrollees in the average plan face substantial out-of-pocket costs for long-lasting treatment: a median of $2,710 for 50 mental health visits, or $2,400 for 50 substance abuse visits. Plans' access to new managed care tools has not led them to stop using benefit limits for cost containment purposes.

Introduction

In the US, private insurance coverage has traditionally been less generous for mental health and substance abuse (MH/SA) treatment than for medical care. In particular, many private health plans limit the number of days, visits or dollars available for MH/SA coverage, even when they do not similarly limit medical coverage. One survey found that in 2006, 81% of insured workers were in plans that had special limits on substance abuse coverage (Gabel, Whitmore and Pickreign et al., 2007). Another survey reported that in 2005, 90% of privately employed workers were in plans with special limits on outpatient mental health coverage (US Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2007). By contrast, special limits on other types of medical care are very rare; more often, plans only impose an overall lifetime limit on plan expenditures for an individual.

The limits originate in insurers' longstanding perceptions that unlimited benefits would result in excessive, costly MH/SA utilization, given uncertainties around diagnosis and treatment. Advocates, providers and others have challenged these perceptions, and countered with concerns that the limits could deter necessary care, or place major financial burdens on affected individuals and their families. Supporting these concerns, one study found that most privately insured people under 65 had benefits that left them at risk of high out-of-pocket costs in the event of a serious mental illness (Zuvekas, Banthin and Selden, 1998). Another study found that 23% of mental health patients paid more than half of the cost of treatment (Ringel and Sturm, 2001). Using 2003 data, Zuvekas and Meyerhoefer (2006) found that patients' share of mental health spending increased with the number of visits, whereas their share of medical spending decreased with the number of visits – a finding consistent with the presence of special limits on MH. From a policy viewpoint, limits appear contrary to the purpose of insurance, which should protect the insured against catastrophic expenses rather than covering only low-end costs (Frank and McGuire, 2003).

In response to these concerns, the federal government recently passed the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (2008), which will prohibit private plans from imposing special limits or differential cost-sharing for mental health and addictions treatment. The act takes effect starting in 2010.

Our study provides baseline data on the current state of benefit limits before the implementation of the 2008 law. Prior to 2008, the only federal regulation of mental health benefit limits was the 1996 Mental Health Parity Act, which barred private plans from imposing dollar limits that were more stringent for mental health than for medical care. The law did not apply to substance abuse coverage, nor did it prohibit other types of limits (e.g. on visits or days). In addition, a majority of states have passed mental health parity laws over the past decade, requiring private plans' coverage of MH/SA to equal medical coverage in some or all dimensions. Some of these laws define parity more widely than the 1996 federal law, for example, by applying it to day and visit limits and to copayments. However, their impact is considerably more limited since state laws do not apply to self-insured employers, under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA). One study estimates that in 2003, only 20% of private-sector employees with employer-sponsored health insurance were covered by strong state parity laws, and only 3% were covered by laws that applied to all mental illnesses (Buchmueller, Cooper, Jacobson et al., 2007).

Some have argued that insurers should now have less need of benefit limits, as they can instead control utilization with managed care tools, such as prior authorization or case management (e.g. Sturm and McCulloch, 1998; Barry, Gabel, Frank et al, 2003). This would imply that fewer plans might now be using benefit limits. However, in recent years there has been a shift in enrollment over time from health maintenance organizations (HMOs) to preferred provider organizations (PPOs), and the latter tend to have weaker utilization management controls anyway (Kronenfeld, 2003; Merrick et al, 2006). Also, a majority of health plans now contract externally for behavioral health, either with a specialized managed behavioral health organization (MBHO) or through a more comprehensive contract that also covers medical care (Horgan, Garnick, Merrick et al, 2008). The plan's contracting approach too may affect reliance on benefit limits, if the external contractor places more or less reliance on them. Finally, the health insurance industry is increasingly dominated by for-profit plans, which may view benefit limits more favorably than not-for-profit plans, if they are under greater pressure to cut costs.

This paper examines the prevalence of benefit limits for MH/SA treatment, and the size of the resulting financial burden for those in treatment. Patients' out-of-pocket burden depends not only on limits but also on copayments, and previous research has found that during 1987-1996, these features moved in opposite directions (limits tightened and copays decreased) (McKusick et al., 2002). We therefore use plans' reported copayment levels, as well as limits, to simulate the potential annual out-of-pocket cost a member could face for specified numbers of outpatient visits. Our questions are:

How common are special limits on mental health and substance abuse benefits?

How large is the potential out-of-pocket cost facing users of MH/SA care, as a function of copayments and limits?

How does the potential out-of-pocket cost relate to health plan characteristics (e.g., profit status) or environment (e.g., state parity law)?

This paper adds to the existing literature by reporting limits and computing out-of-pocket burden separately for both mental health and substance abuse. Although our data were collected several years ago (2003), they report on a nationally representative sample of plans, and it is probable that many of the patterns we describe have persisted since that time. The new 2008 federal parity law should largely eliminate these limits, implying that our data will provide an important baseline for understanding the impact of that law.

Study Data and Methods

Data

We surveyed a nationally representative sample of private health plans regarding alcohol, drug abuse, and mental health services in 1999 and 2003. Our focus was on managed care plans, which by 2003 enrolled 95% of privately insured patients (Gabel, Claxton, Gil et al, 2005); we excluded Medicare and Medicaid insurance products. In 2003 we surveyed 368 plans in the same nationally representative market areas (83% response rate), building on the earlier 1999 survey. The telephone survey included separate modules for administrative and clinical respondents. Each plan was asked about its three most commonly purchased commercial managed care products in 2003. The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at our institution. The study was linked to the Community Tracking Study (CTS), a longitudinal study of health system change funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Further details on sample design are in the Appendix.

The telephone survey was conducted from April 2003 to April 2004. Typically, there were 2 respondents per health plan (1 each for the administrative and clinical components). For some national or regional health plans, we interviewed respondents at the corporate headquarters level regarding multiple sites. In some cases the health plans referred us to their specialty contractor, the managed behavioral health organization (MBHO), for more detailed information. All items were asked at the product level within each market-area-specific health plan. Respondents were asked to treat as one product “any packages, plans or contracts that are similar in terms of out-of-network coverage, referrals, and primary care physicians.”

This paper uses data from the 2003 survey, for the subset of plans that responded to questions about benefit limits (N=745 products, weighted N=7,037). Some of these plans did not report the specific amount of the limit, so for some analyses the sample is smaller (varying by type of limit).

Measuring benefits

Respondents were asked whether each insurance product had annual or lifetime limits on mental health and/or substance abuse services, and the value of those limits in dollars, days or visits. In addition, we asked about the copayment or coinsurance required for outpatient visits for mental health or substance abuse care.

Computing out-of-pocket cost

For each insurance product, we computed a member's expected annual out-of-pocket cost for preset numbers of outpatient visits (20, 50), for both MH and SA services. These utilization levels are not typical, but are experienced by a non-trivial proportion of service users. For example, in recent national data, among patients seeing a psychiatrist, 7.7% received 20 or more visits in the previous 12 months, and 1.6% received 50 or more visits. (For those seeing a nonpsychiatrist specialty provider, the equivalent figures were 26.3% and 8.7%)(Wang, Lane, Olfson et al., 2005). The out-of-pocket cost was computed by applying the plan's reported copayment and coinsurance rates and benefit limits to the specified number of visits. For visits beyond the benefit limit, and for plans with coinsurance, the computation required specifying the total amount paid per visit. We used a figure of $98, based on the national average expenditure in 2003 for visits to outpatient or office-based providers for mental disorders (AHRQ, 2008).

Our use of health plan benefits to estimate out-of-pocket cost is an approach that has been used in previous studies (e.g. McKusick et al 2002; Zuvekas, Banthin & Selden 1998).

Other Variables

Several variables describing characteristics of the insurance product were used:

Product type, which could be health maintenance organizations (HMOs), point-of-service (POS), or preferred provider organizations (PPOs) (observers tend to view HMOs as the most managed and PPOs as the least so);

The plan's contracting arrangement for behavioral health for each product, which could be internal delivery, a contract with a specialty MBHO or a contract with an organization that included both behavioral health and general medical care (termed “comprehensive contract”);

Whether the state had a ‘strong’ mental health parity law, which we defined (following Buchmueller et al, 2007) as laws that “mandate mental health benefits, prohibit limits on visits or days, and limit the extent to which health plan enrollees can be charged higher cost sharing for mental health services”.

Whether the product charged coinsurance (a percent of charges) for behavioral health care, instead of fixed dollar copayments.

Whether the plan selling the product was under for-profit or not-for-profit ownership.

Statistical Analysis

For all analyses, the data presented are weighted to give national estimates for private managed-care insurance products. Multivariate regression analyses were used to test which product characteristics predict out-of-pocket cost for 20 or 50 outpatient visits, for both MH and SA care. The regressions were implemented using SUDAAN software for accurate estimation of the sampling variance, given our complex sampling design (Research Triangle Institute, 2002).

The sampling weights are computed from the inverse of the selection probabilities. The selection probabilities are computed from each stage of selection: site selection and the selection of the health plans in each site. The site selection probability is unity (1.0) for the nine sites selected with certainty and less than 1.0 for the other 51 sites. The health plan selection probability (conditional on the selection of the site) is the selection rate in each site. We computed the base weight for all health plans using the inverse of the product of the probabilities of site selection and of selection of the health plans in each site.

Study Results

Characteristics of the sample

In our sample, 39% of insurance products were POS, 31% were HMO and 30% PPO (Table 1). For more than two-thirds of insurance products, behavioral health care was managed through a contract with a specialty entity (an MBHO). The remainder either managed care internally or had an external contract for both medical and behavioral health care (a ‘comprehensive contract’). Over 80% of insurance-products were in for-profit plans, and only 16% charged consumers coinsurance for MH/SA (the rest used copayments). A majority of products were located in states with a strong mental health parity law.

Table 1.

Sample description

| Percent of products | ||

|---|---|---|

| Product type | ||

| Preferred provider organization (PPO) | 30% | |

| Health maintenance organization (HMO) | 31% | |

| Point of service plan (POS) | 39% | |

| Contracting arrangement | ||

| Internal | 16% | |

| Specialty contract | 72% | |

| Comprehensive contract | 12% | |

| For-profit | 82% | |

| Nonprofit | 18% | |

| Region | ||

| Midwest | 31% | |

| Northeast | 11% | |

| South | 39% | |

| West | 18% | |

| Plan uses coinsurance for behavioral health | 16% | |

| Strong state MH parity law (all diagnoses) | 59% | |

Note: unweighted N=648 insurance products, weighted N=5,769.

Cost-sharing

Among plans using copayments, the mean (median) copayment was $19 ($20) for both MH and SA care. Among plans using coinsurance, the mean (median) rate was 39% (39%) for MH and 35% (32%) for SA. (Data not shown). Previous work with this dataset documented an increase in average cost-sharing between 1999 and 2003 (Horgan et al, 2008).

Prevalence of benefit limits

Lifetime limits on mental health and substance abuse treatment were relatively rare, with only 16% of products using them (Table 2). However, annual limits were much more common: 94% of products had special annual limits for outpatient MH or SA care, and 89% had them for inpatient MH or SA care. (For MH specifically, these figures were 90% and 83%). In addition, around one quarter of products with annual limits had one limit for mental health and one for substance abuse treatment, but most products applied a single limit to both services combined.

Table 2.

Types of limits used

| Dollar | Day or visit |

Both | Type unknown |

Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifetime | ||||||

| Combined MH/SA limit | 3.6% | 7.1% | 1.1% | 11.7% | ||

| Separate MH, SA limits | 0.6% | 1.7% | 2.3% | |||

| Mental health limit only | 0.4% | 0.3% | 0.8% | |||

| Substance abuse limit only | 0.7% | 0.6% | 0.4% | 1.6% | ||

| Any limit | 5.3% | 9.3% | 1.8% | 16.4% | ||

| Annual inpatient | ||||||

| Combined MH/SA limit | 5.4% | 40.3% | 12.7% | 58.4% | ||

| Separate MH, SA limits | 17.3% | 4.1% | 0.9% | 22.3% | ||

| Mental health limit only | 0.1% | 1.7% | 0.1% | 1.8% | ||

| Substance abuse limit only | 0.5% | 6.0% | 6.5% | |||

| Any limit | 5.9% | 65.3% | 16.8% | 1.0% | 89.0% | |

| Annual outpatient | ||||||

| Combined MH/SA limit | 5.3% | 45.1% | 12.7% | 63.2% | ||

| Separate MH, SA limits | 12.1% | 12.9% | 0.5% | 25.4% | ||

| Mental health limit only | 1.0% | 0.1% | 1.1% | |||

| Substance abuse limit only | 0.3% | 4.5% | 4.7% | |||

| Any limit | 5.6% | 62.8% | 12.9% | 13.3% | 94.5% | |

Notes: (1) cells show percent of all insurance products responding to limits questions (including those with no limits). Weighted N=7,037 for inpatient and outpatient limits; 6062 for lifetime limits.

Products were much more likely to limit inpatient days or outpatient visits, rather than limiting spending (Table 2). For example, 45% of products had a combined (MH and SA) annual limit on outpatient visits, but only 5% had a combined annual limit on outpatient spending.

Table 3.

Average out-of-pocket cost for 20 or 50 visits

| Mental health | Substance abuse | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost of 20 visits | Cost of 50 visits | Cost of 20 visits |

Cost of 50 visits |

|

| Mean (Standard deviation) |

$443 (669) | $2,219 (3,566) | $452 (728) | $1,944 (3,506) |

| 10th percentile | $300 | $750 | $300 | $750 |

| Median | $400 | $2,710 | $400 | $2,400 |

| 90th percentile | $980 | $3,440 | $980 | $3,440 |

Note: coinsurance is computed based on assuming the allowed charge is $98 per visit. Weighted N=5,769.

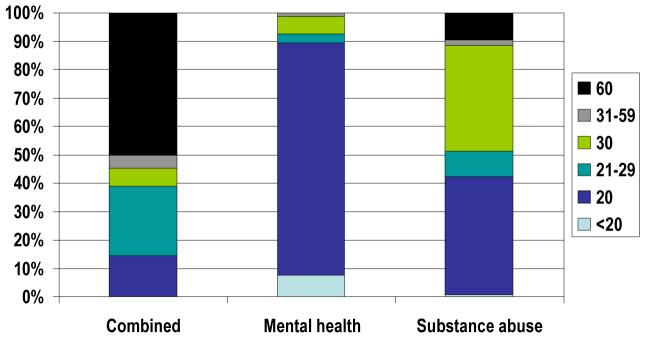

Among products with an annual outpatient visit limit on MH and SA combined, half had a limit of 60 visits and the remainder had varying limits, mostly of less than 30 visits (Figure 1). Among products with a separate annual outpatient visit limit for MH, more than 80% set the limit at 20 visits. By contrast, among products with a separate annual outpatient visit limit for SA, only 40% of products had a 20-visit limit, and many had a more generous limit of 30 visits (Figure 1).

Annual outpatient limits: Number of visits

Note: ‘Combined’ column reports only data for plans with a combined limit (weighted N= 3176). Similarly, weighted N=1,781 for MH and 1,201 for SA.

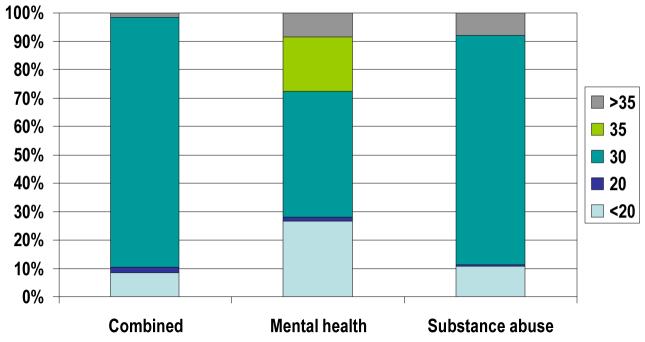

For inpatient care, a 30-day annual limit was the most common choice, whether the limit applied to MH only, SA only, or both combined (Figure 2). Among products with an annual inpatient visit limit on MH and SA combined, nearly 90% had a 30-day limit.

Annual outpatient limits: Number of visits

Note: ‘Combined’ column reports only data for plans with a combined limit (weighted N= 2,835). Similarly, weighted N=1,627 for MH and 1,638 for SA.

Out-of-pocket cost

We computed out-of-pocket cost for preset numbers of visits (20, 50) in each product, based on copayments and the limits already described (Table 3). Among these products, the median out-of-pocket cost for 20 visits would be $400, whether the visits were for substance abuse or mental health treatment. However, if 50 visits were made, the median out-of-pocket cost would be $2,710 for mental health, compared to $2,400 for substance abuse. (Difference is significant (p <.01), paired t-test). This difference confirms that benefit limits are more stringent for mental health than for substance abuse treatment, among the products studied.

Predictors of out-of-pocket cost

Table 4 presents results of a multivariate analysis, to see what characteristics of plan products or their environment predict high out-of-pocket cost burden. Product type is a strong predictor, with HMOs imposing lower out-of-pocket cost than PPOs (the reference group), for both types of care (MH, SA) and both levels of visits (20, 50). In most cases POS plans had a similar effect as HMOs. Products that manage behavioral health care internally have higher out-of-pocket cost for mental health visits than those that contract externally (but differences for substance abuse visits were not significant.) For-profit products differed significantly from nonprofits in only one comparison, with higher out-of-pocket cost for 20 MH visits. Finally, the presence of a strong state parity law is only associated with the level of out-of-pocket cost in one of our models, the one for 50 SA visits, with the association indicating higher cost.

Table 4.

Predictors of out-of-pocket cost for behavioral health visits

| Mental health | Substance abuse | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost of 20 visits | Cost of 50 visits | Cost of 20 visits | Cost of 50 visits | ||

| Intercept | 624.14 ** | 3740.31 ** | 622.25 ** | 2577.63 ** | |

| Product type (ref=PPO) | |||||

| HMO | −146.78 ** | −760.72 ** | −145.94 ** | −342.43 * | |

| POS | −118.73 ** | −897.23 ** | −117.08 ** | −276.71 | |

| Contracting (ref=internal) | |||||

| Specialty contract | −166.33 ** | −528.49 ** | −74.72 | −197.35 | |

| Comprehensive contract | −15.09 | −1063.99 ** | 50.64 | 59.94 | |

| For-profit | 139.23 ** | −181.98 | 40.56 | −66.91 | |

| Region (ref=Midwest) | |||||

| Northeast | −91.12 * | −290.24 | −32.38 | −433.48 | |

| South | −109.34 ** | −564.80 ** | −118.63 ** | −600.11 ** | |

| West | −106.29 * | −384.06 | −123.92 * | −489.44 * | |

| Strong state parity law | −19.93 | 124.13 | 18.96 | 366.61 ** | |

| R-squared | 0.3505 | 0.1870 | 0.2235 | 0.1128 | |

| Weighted N | 5,769 | 5,769 | 5,858 | 5,858 | |

Notes: coefficients are from ordinary least squares regression.

denotes statistical significance at p<.01

denotes statistical significance at p<.05.

In a supplementary set of regressions, we tested whether product type and contracting type interact. The results indicated that out-of-pocket cost is systematically higher in PPO and POS plans with internal provision, and lowest in HMOs with specialty contracts. (Data not shown).

Limitations

This study has two limitations which should be noted. First, we only asked about each plan's three largest commercial managed care products, and thus may lack information on some products. However, most plans reported having 3 or fewer products. Second, we can only report results in terms of prevalence at a product level, as we do not have enrollment data to estimate percentages of enrollees subject to different benefit limits.

Discussion

This study confirms that special limits on behavioral health care continue to predominate, well after managed care became dominant in US health care. 90% of products had special annual limits for outpatient mental health care, whereas other surveys have found that general medical conditions are hardly ever subject to special limits (US Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2007). The only limits widely used for general medical care are limits on lifetime spending, which one survey reported as applying to only half of covered workers in 2004, and being mostly in the $1 million-$2 million range (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2004).

It is noteworthy that so many products have limits of 30 outpatient visits per year (or even lower) for MH and SA combined, given that many individuals have both MH and SA disorders concurrently, and may face an additional challenge getting both treated within 30 visits per year. National survey data indicate that among adults with serious psychological distress in the past year, 22% had past-year dependence or abuse of illicit drugs or alcohol. For adults without serious psychological distress, the rate of past-year dependence or abuse was 8% (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2007).

It is also interesting to note that outpatient limits appear more stringent for mental health than for substance abuse treatment. One might have expected tougher limits on substance abuse, given the general perception that it is more stigmatized, and that spending on it is viewed less favorably by the public, compared to MH treatment (Martin, Pescosolido and Tuch, 2000). On the other hand, from a health plan point of view, SA disorders are considerably less prevalent. In addition, SA benefits may be seen as less vulnerable to discretionary use, given the extreme reluctance of many people to enter SA treatment unless coerced by employers, courts and others, and the unpleasantness of some SA treatments such as opiate detoxification (Barry and Sindelar, 2007). The idea that SA treatment demand is less sensitive to generous benefits is also borne out by recent research finding that the effect of copays on treatment intensity is smaller for SA than had been found previously for MH (LoSasso and Lyons, 2004).

MH also differs from SA in the extent to which medications have emerged as a major part of treatment: in 2003, they accounted for 23% of MH spending but only 0.5% of SA spending (Mark et al 2007a, 2007b). Spending on medications does not count toward the special limits described in this paper, so those limits would have less impact on patients receiving only periodic visits for medication monitoring (although their spending on drugs is managed using other techniques such as three-tier formularies) (Huskamp 2005; Hodgkin, Horgan, Garnick et al., 2007). However, a majority of treatment users have at least some ambulatory visits, amounting to 66% of users in 2001 (Zuvekas, 2005). Plans may perceive a need for continued attention to visit costs, not least as the proportion of the population with any mental health treatment visits has increased over time.

Managed care is often viewed as having less need of benefit limits, given its access to other cost-containment tools such as utilization management and provider profiling (Barry, Frank, and McGuire, 2006). In support of this, we find that out-of-pocket costs are lower in HMO and POS products, which are viewed as more managed than PPOs. This confirms Zuvekas and Meyerhoefer's (2006) finding in national patient-level data, where HMO members had lower out-of-pocket share. However, our results suggest that despite having these other tools, managed care plans have not chosen to abandon benefit limits, perhaps because they perceive risks in doing so, or no gains. When the federal 1996 Mental Health Parity Act banned special limits on mental health spending, plans responded by replacing spending limits with limits on visits and days, rather than by abandoning limits altogether (Gitterman, Sturm, Pacula et al, 2001). Barry and colleagues have suggested that plans may retain limits as a way to discourage enrollment of individuals likely to use mental health benefits (Barry, Gabel, Frank et al, 2003).

State parity laws had little effect on expected out-of-pocket cost in our study, possibly due to the large number of employers that are exempted from state laws due to their small size or self-insured status (Buchmueller et al., 2007).

The benefit limits we document here should mostly disappear under the new federal parity law that just passed. Where the 1996 law only banned special dollar limits for MH, the 2008 law adds a prohibition on other special limits such as for visits or episodes. In addition, the 2008 law applies to SA treatment too, where the 1996 law only covered MH. Finally, it prohibits the use of higher copays/coinsurance for MH/SA, which were allowed under the 1996 law, and affect many more patients than limits, since they must be paid even by low users who would not reach the limit. Like the 1996 law, the 2008 law includes exemptions for small employer groups (those with fewer than 50 enrollees).

However, elimination of special benefit limits will not necessarily remove all access barriers to BH care, depending on how health plans react. Some plans could drop BH benefits altogether, since the law still does not mandate BH coverage in private insurance. Alternatively, they could raise copayments and coinsurance – as long as the increases are for all care, not just BH care. This would mean the new law had less ability to reduce patient's out-of-pocket costs. Finally, plans could increase the stringency of their utilization management for BH care, for example by requiring more frequent reauthorization of treatment. The new law requires disclosure of plans' medical necessity criteria, but leaves various other management approaches up to the plan's discretion.

Continued monitoring of patients' access to BH treatment will therefore require supplementing benefits data with information on managed care plans' utilization management activities. This would allow a fuller picture of the state of patient access to MH/SA treatment. It will also be important to examine differences in out-of-pocket burden across socioeconomic groups.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (grant R01 AA 010869) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (grant R01 DA10915), National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland. The authors thank respondents from the participating health plans for their time; Frank Potter and the staff at Mathematica Policy Research, for fielding the survey; Galina Zolotusky for programming assistance; and Grant Ritter, Sharon Reif and Joanna Volpe-Vartanian for helpful discussions.

Appendix

The study was linked to the Community Tracking Study (CTS), a longitudinal study of health system change funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (Kemper, Blumenthal, Corrigan et al., 1996). At the first stage, the primary sampling units were the 60 market areas the CTS had selected to be nationally representative. The CTS study defined market areas based on Metropolitan Statistical Areas (for metropolitan communities) or Bureau of Economic Analysis Economic Areas (for non-metropolitan communities). The second stage of our sampling consisted of selecting plans within market areas. Plans serving multiple markets were defined as separate plans for the study and data were collected with reference to the specific market.

The 1999 sample frame was based on a CTS household survey that used responses to identify and survey insurers and health plans regarding plan characteristics. This survey yielded around 1000 entities categorized as health plans. After excluding entities that were exclusively indemnity plans and those no longer present within market areas, 944 plans constituted our sample frame, from which 720 market-specific plans were selected with equal probability and without replacement across the sites. The plan sample was allocated to each market area based on the weighted estimate of plan enrollees in each site, with proportional distribution between preferred-provider organization (PPO)-only and health maintenance organization (HMO)/multitype plans. Of the 720 sampled plans, 247 were deemed ineligible because they had closed, merged or were otherwise unreachable, had fewer than 300 subscribers in the market, did not offer comprehensive health care products, or served only Medicaid/Medicare. This left 473 eligible plans, of which 434 (92%) responded, regarding 787 eligible insurance products.

For the 2003 survey, we augmented the 1999 sample of 720 plans with a national sample of plans not previously operating in the market areas. Of the 110 new plans identified, we selected 94, maintaining the same sampling rates as those in 1999. Thus, the 2003 sample frame consisted of 1054 plans, and the sample totaled 814 plans including all 1999 eligible sampled cases plus a sample of 1999 ineligibles and new plans. Of these 814 plans, 373 were ineligible, leaving 441 eligible plans, of which 368 (83%) responded and reported on 812 products. Four products that were “consumer driven” (a new category in 2003), were excluded from analyses. Data used in this study were from the 2003 survey.

References

- Barry CL, Gabel JR, Frank RG, et al. Design of mental health benefits: still unequal after all these years. Health Affairs. 2003 Sep-Oct;22(5):127–37. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.5.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry CL, Frank RG, McGuire TG. The costs of mental health parity: still an impediment? Health Affairs. 2006;25(3):623–634. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.3.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry CL, Sindelar JL. Equity in private insurance coverage for substance abuse: A perspective on parity. Health Affairs. 2007 doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.6.w706. 10.1377/hlthaff.26.6w706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchmueller TC, Cooper PF, Jacobson M, Zuvekas S. Parity For Whom? Exemptions And The Extent Of State Mental Health Parity Legislation. Health Affairs. 2007:w483–487. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.4.w483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly R. Law Opens MCO Panels To ‘Any Willing Provider’. Psychiatric News. 2006;41(13):10. [Google Scholar]

- Frank RG, McGuire TG. Economics and mental health. In: Culyer AJ, Newhouse JP, editors. Handbook of Health Economics. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gabel J, Claxton G, Gil I, et al. Health Benefits In 2005: Premium Increases Slow Down, Coverage Continues To Erode. Health Affairs. 2005;24(5):1273–1280. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.5.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabel JR, Whitmore H, Pickreign JD, et al. Substance abuse benefits: Still limited after all these years. Health Affairs. 2007;26(4):w474–w482. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.4.w474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitterman DP, Sturm R, Pacula RL, Scheffler RM. Does the sunset of mental health parity really matter? Adm Policy Mental Health. 2001;28(5):353–69. doi: 10.1023/a:1011113932599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glied SA, Frank RG. Shuffling toward parity: bringing mental health under the umbrella. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;359(2):113–115. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0804447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman HH, Frank RG, Burnam MA, et al. Behavioral health insurance parity for federal employees. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(13):1378–86. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa053737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkin D, Horgan CM, Garnick DW, Merrick EL, Volpe-Vartanian J. Management of Access to Branded Psychotropic Medications in Private Health Plans. Clinical Therapeutics. 2007;29:371–380. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horgan CM, Garnick DW, Merrick EL, Hodgkin D. Changes in How Health Plans Provide Behavioral Health Services. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research, forthcoming. doi: 10.1007/s11414-007-9084-0. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huskamp HA. Pharmaceutical cost management and access to psychotropic drugs: The U.S. context. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 2005;28(5):484–495. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation . Employer health benefits: 2004 annual survey. Menlo Park; California: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kemper P, Blumenthal D, Corrigan JM, et al. The design of the community tracking study: a longitudinal study of health system change and its effects on people, Inquiry. Summer. 1996;33(2):195–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronenfeld JJ. Organizational Variation In The Managed Care Industry In The 1990s: Implications For Institutional Change. In: Anthony D, Banaszak-Holl J, editors. Reorganizing Health Care Delivery Systems: Problems of Managed Care and Other Models of Health Care Delivery. Emerald Group Publishing; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- LoSasso AT, Lyons JS. The sensitivity of substance abuse treatment intensity to co-payment levels. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2004;31(1):50–65. doi: 10.1007/BF02287338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark TL, Levit KR, Buck JA, et al. Mental health treatment expenditure trends, 1986-2003. Psychiatric Services. 2007a;58(8):1041–1048. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.8.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark TL, Levit KR, Vandivort-Warren R, et al. Trends in spending for substance abuse treatment, 1986-2003. Health Affairs. 2007b;26(4):1118–1128. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.4.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JK, Pescosolido BA, Tuch SA. Of Fear and Loathing: The Role of ‘Disturbing Behavior’, Labels, and Causal Attributions in Shaping Public Attitudes Toward Persons with Mental Illness. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000;41(2):208–223. [Google Scholar]

- McKusick DR, Mark TL, King EC, Coffey RM, Genuardi J. Trends in mental health insurance benefits and out-of-pocket spending. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics. 2002;5(2):71–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. 2008 http://www.meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/, accessed 7/17/2008.

- Merrick EL, Horgan CM, Garnick DW, Hodgkin D. Managed care organizations' use of treatment management strategies for outpatient mental health care. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2006;33(1):104–14. doi: 10.1007/s10488-005-0024-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul Wellstone and Pete Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act. 2008. (Pub. L. No. 110-343, 122 Stat. 3765). [Google Scholar]

- Peele PB, Lave JR, Xu Y. Benefit limits in managed behavioral health care: do they matter? Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 1999;26(4):430–441. doi: 10.1007/BF02287303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Research Triangle Institute . SUDAAN User's Manual: release 8.0. Research Triangle Institute; Research Triangle Park, NC: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ringel JS, Sturm R. Financial burden and out-of-pocket expenditures for mental health across different socioeconomic groups: results from healthcare for communities. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2001;4(3):141–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturm R. How expensive is unlimited mental health care coverage under managed care? JAMA. 1997;278(18):1533–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturm R, McCulloch J. Mental health and substance abuse benefits in carve-out plans and the Mental Health Parity Act of 1996. Journal of Health Care Financing. 1998;24(3):82–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturm R, Zhang W, Schoenbaum MJ. How expensive are unlimited substance abuse benefits under managed care? Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research. 1999;26(2):203–10. doi: 10.1007/BF02287491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Results from the 2006 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Rockville, MD: 2007. (NSDUH Series H-32, DHHS Publication No. SMA 07-4293). [Google Scholar]

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics . National Compensation Survey: Employee Benefits in Private Industry in the United States, 2005. 2007. Bulletin 2589. [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):629–40. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuvekas SH, Banthin JS, Selden TM. Mental health parity: what are the gaps in coverage? Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics. 1998;1(3):135–146. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-176x(1998100)1:3<135::aid-mhp17>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuvekas SH, Meyerhoefer CD. Coverage for mental health treatment: do the gaps still persist? Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics. 2006;9(3):155–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuvekas SH. Prescription drugs and the changing patterns of treatment for mental disorders, 1996-2001. Health Affairs. 2005;24(1):195–205. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.1.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]