Abstract

Seasonal dynamics of total phenolics (TP), extractable condensed tannins (ECT), protein-bound condensed tannins (PBCT), fiber-bound condensed tannins (FBCT), total condensed tannins (TCT), and protein precipitation capacity (PPC) in young, mature and senescent branchlets of Casuarina equisetifolia were studied at Chishan Forestry Center of Dongshan County, Fujian Province, China. In addition, nitrogen contents of branchlets at the different developmental stages were also determined. The contents of TP and ECT, and PPC in young branchlets were significantly higher than those in mature and senescent branchlets through the season. However, PBCT contents were significantly higher in senescent branchlets than those in young and mature branchlets; FBCT fluctuated with season. Young branchlets had the highest N content, which decreased during branch maturity and senescence. The highest contents of TP and the lowest contents of TCT and N in young and mature branchlets were observed in summer. There was a significant negative correlation between TP and N contents. In contrast, TCT contents were positively correlated to N contents. Nutrient resorption during senescence and high TCT:N ratios in senescent branchlets are the important nutrient conservation strategies for C. equisetifolia.

Keywords: Casuarina equisetifolia, Condensed tannins, Total phenolics, Nitrogen, Seasonal dynamics

INTRODUCTION

Casuarina equisetifolia is a nitrogen-fixing tree of considerably social, economic and environmental importance in tropical/subtropical littoral zones of Asia, the Pacific, and Africa. It is commonly used in agro-forestry systems for soil stabilization and reclamation work and in coastal protection and rehabilitation (Pinyopusarerk and House, 1993; Pinyopusarerk and Williams, 2000). It is one of the most extensively introduced tree species outside its natural range. There are more than 300 000 ha of C. equisetifolia plantations in the coastline of southern China (Zhong et al., 2005). Despite the widespread planting and known ecological and physiological properties of C. equisetifolia, very little has been done to explore secondary metabolism production along with seasonal changes, although they are recognized as high in tannin and astringent (Okuda et al., 1980).

Tannins play a role in a number of ecological processes in addition to herbivore defense, including litter decomposition, nutrient cycling, nitrogen sequestration, microbial activity, humic acid formation, metal complexation, and pedogenesis (Kraus et al., 2003). Tannins comprise a significant portion of terrestrial biomass C (Hernes et al., 2001). Leaves and bark may contain up to 40% tannin by dry weight (Kuiters, 1990; Matthews et al., 1997; Lin et al., 2006; 2007), and in leaves and needles tannin contents can exceed lignin levels (Hernes et al., 2001). Because tannins are complex and energetically costly molecules to synthesize, their widespread occurrence and abundance suggest that tannins play an important role in plant function and evolution (Cates and Rhoades, 1977; Zucker, 1983). Some species rich in polyphenols appear to gain a competitive advantage by altering nutrient cycling and thus influencing forest dynamics (Northup et al., 1998; Fierer et al., 2001; Kraus et al., 2003). Plants greatly influence soil processes through litter inputs (Aber et al., 1990); thus, alterations in foliar chemistry have important implications for plant-litter-soil interactions and ecosystem function (Kraus et al., 2004).

Traditionally, justification for the high metabolic cost associated with the production of tannins was attributed to improve herbivore defense (Feeny, 1970). Two major hypotheses have been proposed to predict the effects of environmental factors on secondary metabolite concentrations. The carbon-nutrient balance (CNB) hypothesis postulates that phenolic levels in plants are determined by the balance between carbon and nutrient availability (Bryant et al., 1983). The growth-differentiation balance (GDB) hypothesis (Loomis, 1932; Lorio, 1986; Herms and Mattson, 1992) considers factors that limit growth and differentiation (the sum of chemical and morphological changes that occur in maturing cells, including carbon-based secondary synthesis). The production of phenolics dominates when factors other than photosynthate supply are suboptimal for growth (e.g., under nutrient limitation or moderate drought). Resource-based theories assume that the synthesis of defensive compounds is constrained by the external availability of resources and internal trade-offs in resource allocation between growth and defense (Riipi et al., 2002). They state that growth processes dominate over the production of defensive compounds, and that more carbon is left for defensive compounds only when plant growth is restricted by a lack of mineral nutrient (emphasized by the CNB hypothesis) or by any factor (according to the GDB hypothesis) (Haukioja et al., 1998). Jones and Hartley (1999) presented a protein competition model (PCM) for predicting total phenolics allocation and content in leaves of terrestrial higher plants. They stated that “protein and phenolics synthesis compete for the common, limiting resource phenylalanine,” so nitrogen (N) rather than C is the limiting resource for synthesis of phenolics.

Despite the growing knowledge of the physiological basis and ecological consequences of leaf phenolics presence in plant tissues, only a few extensive datasets are available to evaluate the relative importance of leaf phenolics variability caused by environmental changes and developmental stages (Covelo and Gallardo, 2001; Lin et al., 2007). This variability may determine not only the susceptibility of plants to herbivore attack, but also important aspects of nutrient cycling in terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems (Gallardo and Merino, 1992; Serrano, 1992; Mafongoya et al., 1997; Northup et al., 1998).

According to PCM, the growth-defense trade-off depends not only on competition for a limited pool of available carbohydrates, but also on competition for nitrogen as a component of common precursor compounds (Jones and Hartley, 1999; Gayler et al., 2007). In this regard, information on the seasonal dynamics of tannins and nitrogen contents is necessary.

The objective of the present study was to test the validity of the following hypotheses: (1) Tannins of branchlets at different developmental stages follow a seasonal pattern; (2) The production of phenolics dominates under nutrient limitation. To answer these hypotheses, a field investigation of C. equisetifolia was conducted at Chishan Forestry Center of Dongshan County, Fujian Province, China.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study areas

The study was carried out at Chishan Forestry Center of Dongshan County (23°40′ N, 117°18′ E), Fujian Province, China. The climate of the region belongs to southern subtropical maritime monsoon climate, with annual temperature ranging from 3.8 °C to 36.6 °C. Mean annual precipitation and evaporation are 1 103.8 mm and 2 027.9 mm, respectively. The rain season is from May to September and the dry season is from October to April of the next year. The soils are coastal sandy barren.

The C. equisetifolia plantations were artificial, pure forests that were planted in 1999. The coverage of dense forest was 0.7, tree density was 3 552 tree/ha, canopy height ranged from 5~7 m, and diameter at breast height (DBH) was (8.1±1.4) cm. The average N and P contents of the soils at 20 cm depth were (54.49±7.89) and (2.69±0.42) mg/kg, respectively, and soil pH was 4.19±0.05.

Materials

Thirty individuals of C. equisetifolia were chosen and labeled. The height and growth conditions of the chosen trees were similar. The development stages of branchlets were demarcated into three stages, i.e., young branchlets (newly-emerged, usually shorter than 5 cm in length at the top of branch, and light green in color), mature branchlets (fully developed, usually 15~25 cm long, and dark green in color), and senescent branchlets (old branchlets, white or grey in color). Branchlets damaged by insects and disease or mechanical factors were avoided. Young, mature and senescent branchlets of each labeled tree were collected in March, June, September, and December of 2007. All samples were taken to the laboratory immediately after sampling and cleaned with distilled water.

Chemical analyses

All chemicals were of analytical reagent purity grade. An additional standard denoted here as purified tannin, was extracted from C. equisetifolia branchlets and purified on Sephadex LH-20 (Amersham, USA) according to the procedure previously described by Asquith and Butler (1986) as modified by Hagerman (2002). The condensed tannin standard was freeze-dried and stored at −20 °C until required.

Procedures described by Lin et al.(2006) were used to determine total phenolics (TP), extractable condensed tannins (ECT), protein-bound condensed tannins (PBCT), fibre-bound condensed tannins (FBCT), and protein precipitation capacity (PPC). TP were measured with the Prussian blue method (Graham, 1992), and ECT, PBCT and FBCT were assayed by the butanol-HCl method (Terrill et al., 1992) using purified tannins from C. equisetifolia branchlets as the standard. The contents of total condensed tannins (TCT) were calculated by adding the respective quantities of ECT, PBCT, and FBCT (Terrill et al., 1992). A radial diffusion assay was used to determine the PPC (Hagerman, 1987).

N content was determined with Nessler’s reagent after Kjeldahl digestion of powdered samples with sulfuric acid and hydrogen peroxide (Mae et al., 1983).

Calculations

Resorption efficiency (RE) was calculated as the percentage of N recovered from the senescing leaves (Aerts, 1996; Killingbeck, 1996):

| RE (%)=(A1−A2)/A1×100, |

where A 1 is N content in mature branchlets; A 2 is N content in senescent branchlets.

Statistical analyses

All measurements were replicated three times and analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (SPSS 11.0 for Windows) with TP, ECT, PBCT, FBCT, TCT, and PPC.

RESULTS

Seasonal dynamics of total phenolics contents

TP content was highest in young branchlets, (146.17±4.14) to (169.23±4.78) mg/g, and decreased with maturity and senescence. TP did not follow the identical pattern for young, mature, and senescent branchlets. TP contents of young [(169.23±4.78) mg/g] and mature [(118.40±5.81) mg/g] branchlets in summer were relatively high than those in other seasons. TP content of senescent branchlets was the lowest in summer [(24.56±0.92) mg/g] and the highest in winter [(98.74±16.10) mg/g] (Fig.1).

Fig. 1.

Seasonal changes in total phenolics contents of branchlets at different development stages of C. equisetifolia

Seasonal dynamics of condensed tannin contents

ECT contents of young and senescent branchlets were significantly higher in winter than in other three seasons (Fig.2a), which was different from the observation of ECT contents of mature branchlets. The ECT contents of young and senescent branchlets in winter reached (316.17±64.10) and (168.06±44.19) mg/g, respectively. ECT contents of mature branchlets ranged from (101.44±16.17) to (137.36±13.48) mg/g, and remained unchanged with season. ECT contents of senescent branchlets were significantly lower than those of young and mature branchlets except for the mature branchlets in winter, showing that the ECT contents of the branchlets decreased with senescence.

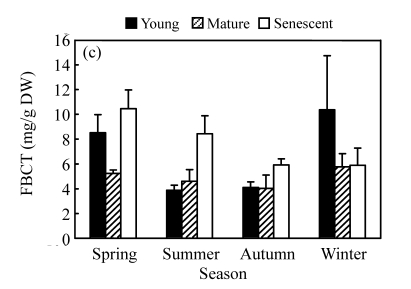

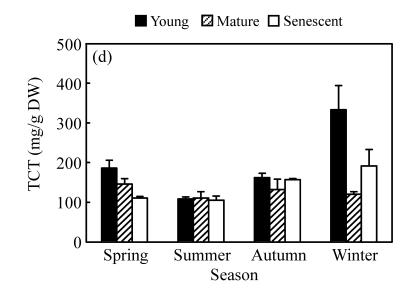

Fig. 2.

Seasonal changes in ECT (a), PBCT (b), FBCT (c) and TCT (d) contents of branchlets at different development stages of C. equisetifolia

PBCT contents were significantly higher in senescent branchlets than in young and mature branchlets (Fig.2b), showing that PBCT contents increased with senescence. The highest PBCT contents of young and mature branchlets in autumn were (13.55±2.32) and (7.43±1.01) mg/g, respectively. PBCT contents of young and mature branchlets both increased gradually during the growing season and then declined in winter. However, FBCT contents of the branchlets showed the decreasing trends during the growing seasons, and then increased in winter (Fig.2c). Except for in winter, FBCT contents of senescent branchlets were significantly higher than those of young and mature branchlets (Fig.2c).

PBCT was significantly higher than FBCT for senescent branchlets, but there was no significant difference for young and mature branchlets. ECT accounted for 89%~95% of TCT in young and mature branchlets, with 5%~11% being bound to protein or fibre (Fig.2d).

Seasonal dynamics of protein precipitation capacity

PPC was the highest in young branchlets, and decreased with maturity and senescence (Fig.3). The PPCs of young [(530.19±30.39) cm2/g] and mature [(398.28±23.01) cm2/g] branchlets were lower in spring than in other seasons.

Fig. 3.

Seasonal changes in PPC of branchlets at different development stages of C. equisetifolia

Seasonal dynamics of nitrogen content and resorption efficiency

Young and mature branchlets had significantly higher nitrogen contents than senescent branchlets. The N contents of senescent branchlets were all below 0.86% (Fig.4). The lowest N contents all occurred in the summer for young, mature, and senescent branchlets. The N contents remained relatively stable for the other seasons. Nitrogen resorption efficiency (NRE) ranged from (51.01±3.94)% to (63.00±8.61)% with no significant difference among four seasons.

Fig. 4.

Seasonal changes in N contents of branchlets at different development stages of C. equisetifolia

Numbers within the ellipses represent the nitrogen resorption efficiency

DISCUSSION

Young branchlets had the higher contents of TP and ECT than mature and senescent branchlets. The observed changes in TP and ECT contents of the branchlets associated with different development stages are in accordance with the findings reported for different mangrove species (Lin et al., 2006; 2007) and oak species (Makkar et al., 1988; Rossiter et al., 1988). Young leaves need to be well defended, since damage to young leaves may cause a larger decline in future photosynthesis than damage to mature leaves (McKey, 1974; Harper, 1989). In addition, the fact that young branchlets contain much higher contents of TP and ECT compared with mature and senescent branchlets may indicate that young branchlets are experiencing more intense selective pressure than mature and senescent branchlets. Many of the soluble carbon compounds (which also include polyphenols) are expected to be translocated from leaves during senescence (Mafongoya et al., 1998). The depletion of TP and ECT during senescence in the spring, summer and autumn and the enrichment of TP and ECT during senescence in winter were found in the present study. The decrease in phenolics content may reflect an active turnover of phenolics and an increase in bound or nonextractable phenolics during senescence (Fig.2b). As polyphenols are water-soluble and susceptible to leaching (Hättenschwiler and Vitousek, 2000), leaching of polyphenols or tannins by sporadic rain (from green leaves) might be a cause for the net ‘enrichment’ in senesced leaves (Teklay, 2004), but the exact cause or mechanism is difficult to ascertain. Constantinides and Fownes (1994) also found both an increase and a decrease in polyphenol contents. Kuhajek et al.(2006) observed that no significant effects of leaf age on both condensed tannins and total phenolics. As for bound condensed tannins, PBCT contents were significantly higher in senescent branchlets than in young and mature branchlets.

Seasonal changes in leaf chemistry reflect changing demands for carbohydrates and nutrients resulting from normal growth and differentiation processes (Wareing, 1959; Moorby and Wareing, 1963). The GDB hypothesis (Loomis, 1932; Lorio, 1986; Herms and Mattson, 1992) and the CNB hypothesis (Bryant et al., 1983) assume that the synthesis of carbon-rich secondary chemicals is limited by the availability of photosynthesis (carbon). According to these hypotheses, growth processes dominate over differentiation or production of carbon-rich secondary compounds as long as conditions are favorable for growth, but the GDB hypothesis is associated with the temporal variation in growth activity more directly than the CNB hypothesis (Tuomi, 1992). If plant growth is active, and therefore demands large amounts of carbon, allocation to carbon-rich secondary metabolites, e.g., phenolics, is predicted to decline; however, when growth is limited more than photosynthesis, allocation to defense will increase (Riipi et al., 2002). Under the assumptions of the GDB hypothesis, allocation to phenolics should be low in spring during rapid growth of the short-shoot leaves (Riipi et al., 2002). The amounts of phenolics should increase most quickly in summer, when the photosynthetic capacity of the newly matured leaves is highest (Mooney and Gulmon, 1982). The highest TP content in summer was found in this paper (Fig.1). C. equisetifolia growth is active from May to September (rain season) with the relatively high soil water availability. According to the PCM hypothesis, protein demand should be highest when plant grows rapidly, and allocation to those phenolics that are derived from phenylalanine should simultaneously decrease (Jones and Hartley, 1999), as phenylalanine is the common precursor of either protein or condensed tannins synthesis (Hättenschwiler and Vitousek, 2000). However, the second major group of phenolics, the hydrolysable tannins, has gallic acid as its precursor (Haukioja et al., 1998). Therefore, depending on the relative strength of the synthetic route via dehydroshikimic acid to gallic acid, hydrolysable tannins may or may not trade off directly with protein synthesis (Haukioja et al., 1998). Hydrolysable tannins are thought to be metabolically cheaper than phenylpropanoids, and the synthesis of it in the season may be a cost-saving defense strategy during a time when condensed tannins are not yet effective as defense (Haukioja et al., 1998; Salminen et al., 2001). However, the changes in contents do not necessarily reflect the quantitative allocation of tannins to the leaves, because of rapid turnover of labile compounds (Kleiner et al., 1999) and because the contents are affected by concomitant changes in proportions of other components of the leaves, e.g., structural leaf components (Koricheva, 1999).

The lowest nitrogen contents of branchlets at the different development stages occurred in summer, when C. equisetifolia growth is active. Similarly, Aerts et al.(1999) suggested that summer warming reduced N contents of mature and senescent leaves in Rubus. First, a portion of N was allocated to other portions (e.g., roots and flowers); for example, the peak of the flowering period appears from April to June for C. equisetifolia (Morton, 1980). Second, N contents were diluted by branchlets mass accumulation during summer when C. equisetifolia grew rapidly. Changes in leaf N contents may directly impact the photosynthetic capacity of the species involved, as there is usually a direct relation between leaf N content and the maximum rate of photosynthesis (Lambers et al., 1998). In this study, TP contents were inversely related to N contents. It is common to find a negative correlation between N and secondary compound contents, such as phenolics and tannins (Horner et al., 1987; Mansfield et al., 1999). This pattern lends to support source-sink hypotheses, such as the CNB hypothesis (Bryant et al., 1983) and the GDB hypothesis (Herms and Mattson, 1992) that predict increased C allocation to secondary C compounds under low nutrient conditions. However, there was a positive correlation between N and TCT contents, which is consistent with a previous study (Horner et al., 1987) but inconsistent with other study (Kraus et al., 2004). They may result from differences in the carbon:nutrient balance of the plants resulting from differences in relative resource availability (Horner et al., 1987).

The young leaves were likely to produce toxic effects even at low levels of intake, and PPC was considered to be related to the biological activity (Martin and Martin, 1982; Deshpande et al., 1986) and was very high in the young leaves. The research on C. equisetifolia comes to the same result (Fig.3). The capacity of tannin to bind proteins was related to the molecular size of the tannins (Makkar et al., 1987). In general, it was found that the larger-sized condensed tannin could precipitate more protein than the smaller-sized condensed tannin (Osborne and McNeill, 2001). In this study, there was no significant correlation between TP or TCT and PPC in young and mature branchlets (Table 1), which is consistent with the previous study (Martin and Martin, 1982). However, there was a significantly positive correlation between TP or TCT and PPC in senescent branchlets. The results indicate that the possible increase in degree of polymerization with senescence leads to the more larger-sized tannins and the more protein precipitated.

Table 1.

Correlative coefficient of selected branchlet data (n=12)

| Branchlets | TP vs N | TCT vs N | TP vs TCT | TP vs PPC | TCT vs PPC |

| Young | −0.615 (P=0.033) | 0.554 (P=0.061) | −0.081 (P=0.802) | 0.190 (P=0.554) | 0.242 (P=0.448) |

| Mature | −0.785 (P=0.002) | 0.497 (P=0.100) | −0.126 (P=0.695) | 0.147 (P=0.649) | −0.647 (P=0.023) |

| Senescent | 0.374 (P=0.231) | 0.264 (P=0.407) | 0.926 (P=0) | 0.870 (P=0) | 0.870 (P=0) |

TP:N ratio was the highest in young branchlets and decreased with maturity and senescence in spring and summer, while TP:N ratio of branchlets decreased with maturity and increased with senescence in autumn and winter (Fig.5a). TP:N ratios of young and mature branchlets were both the highest in summer, and remained relatively stable in other three seasons. The relatively low TP contents of senescent branchlets paired with high N contents in spring resulted in the low TP:N ratios. The TP:N ratios of senescent branchlets increased through the season (from spring to winter).

Fig. 5.

Seasonal changes in TP:N (a) and TCT:N (b) ratios of branchlets at different development stages of C. equisetifolia

Seasonal changes in TCT:N ratios during development stages were different from the observation of TP:N ratios (Fig.5b). TCT:N ratios of senescent branchlets were significantly higher than those of young and mature branchlets.

TCT:N ratios of senescent branchlets were significantly higher than TP:N ratios of senescent branchlets in corresponding seasons.

The role that tannins play in soil processes is believed to occur largely through their ability to precipitate proteins, as well as their relative resistance to decomposition (Kuiters, 1990; Kraus et al., 2003). The amount of tannins entering the soil relative to the amount of proteins or N may be the key factor influencing soil nutrient cycling. Therefore, parameters such as TP:N and CT:N ratios may be the best predictors of litter quality (Kraus et al., 2004). In green foliage, high TP:N and TCT:N ratios may help reduce herbivory. In our study, TP:N ratios in young branchlets were higher than those in mature branchlets. The highest levels of TP:N in young and mature branchlets both occurred in summer, indicating potentially increased grazer deterrence. TP:N ratios in senescent branchlets increased through the season (from spring to winter). TCT:N ratios were significantly higher in senescent branchlets than those in young and mature branchlets. Nutrient resorption (about 50%~60%) during senescence and high TCT:N ratios in senescent branchlets are the important nutrient conservation strategies for C. equisetifolia.

Footnotes

Project supported by the National Eleventh Five-year Key Project (No. 2006BAD03A14-01), Fujian Provincial Major Special Program of Science and Technology (No. 2006NZ0001-2), the Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University (No. NCET-07-0725), and the Program for Innovative Research Team in Science and Technology in Fujian Province University, China

References

- 1.Aber JD, Melillo JM, McClaugherty CA. Predicting long term patterns of mass loss, nitrogen dynamics, and soil organic matter formation from initial fine litter chemistry in temperate forest ecosystems. Canadian Journal of Botany. 1990;68(10):2201–2208. doi: 10.1139/b90-287. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aerts R. Nutrient resorption from senescing leaves of perennials: are there general patterns? Journal of Ecology. 1996;84(4):597–608. doi: 10.2307/2261481. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aerts RJ, Barry TN, McNabb WC. Polyphenols and agriculture: beneficial effects of proanthocyanidins in forages. Agriculture Ecosystems & Environment. 1999;75(1-2):1–12. doi: 10.1016/S0167-8809(99)00062-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asquith T, Butler L. Interactions of condensed taninis with selected proteins. Phytochemistry. 1986;25(7):1591–1593. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)81214-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bryant JP, Chapin FSIII, Klein DR. Carbon/nutrient balance of boreal plants in relation to vertebrate herbivory. Oikos. 1983;40(3):357–368. doi: 10.2307/3544308. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cates RG, Rhoades DF. Patterns in the production of antiherbivore chemical defenses in plant communities. Biochemical Systematics Ecology. 1977;5(3):185–193. doi: 10.1016/0305-1978(77)90003-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Constantinides M, Fownes JH. Nitrogen mineralization from leaves and litter of tropical plants: relationship to nitrogen, lignin and soluble polyphenol concentrations. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 1994;26(1):49–55. doi: 10.1016/0038-0717(94)90194-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Covelo F, Gallardo A. Temporal variation in total leaf phenolics content of Quercus robur in forested and harvested stands in northwestern Spain. Canadian Journal of Botany-Revue Canadienne De Botanique. 2001;79(11):1262–1269. doi: 10.1139/cjb-79-11-1262. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deshpande SS, Cheryan M, Salunkhe DK. Tannin analysis of food products. CRC Critical Review in Food Science and Nutrition. 1986;24(4):401–449. doi: 10.1080/10408398609527441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feeny P. Seasonal changes in oak leaf tannins and nutrients as a cause of spring feeding by winter moth caterpillars. Ecology. 1970;51(4):565–581. doi: 10.2307/1934037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fierer N, Schimel JP, Cates RG, Zou JP. Influence of balsam poplar tannin fractions on carbon and nitrogen dynamics in Alaskan taiga floodplain soils. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 2001;33(12-13):1827–1839. doi: 10.1016/S0038-0717(01)00111-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gallardo A, Merino J. Nitrogen immobilization in leaf litter at two Mediterranean ecosystems of SW Spain. Biogeochemistry. 1992;15(3):213–228. doi: 10.1007/BF00002937. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gayler S, Grams TEE, Heller W, Treutter D, Priesack E. A dynamical model of environmental effects on allocation to carbon-based secondary compounds in juvenile trees. Annals of Botany. 2007;101(8):1089–1098. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcm169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graham HD. Stabilization of the Prussian blue color in the determination of polyphenols. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 1992;40(5):801–805. doi: 10.1021/jf00017a018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hagerman AE. Radial diffusion method for determining tannin in plant extracts. Journal of Chemical Ecology. 1987;13(3):437–449. doi: 10.1007/BF01880091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hagerman AE. Tannin Chemistry. 2002 (Available from: http://www.users. muohio.edu/hagermae/tannin.pdf)

- 17.Harper JL. The value of a leaf. Oecologia. 1989;80(1):53–58. doi: 10.1007/BF00789931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hättenschwiler S, Vitousek PM. The role of polyphenols in terrestrial ecosystem nutrient cycling. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 2000;15(6):238–243. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(00)01861-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haukioja E, Ossipov V, Koricheva J, Honkanen T, Larsson S, Lempa K. Biosynthetic origin of carbon-based secondary compounds: cause of variable responses of woody plants to fertilization? Chemoecology. 1998;8(3):133–139. doi: 10.1007/s000490050018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herms DA, Mattson WJ. The dilemma of plants: to grow or defend. Quarterly Review of Biology. 1992;67(3):283–335. doi: 10.1086/417659. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hernes PJ, Benner R, Cowie GL, Goni MA, Bergamaschi BA, Hedges JI. Tannin diagenesis in mangrove leaves from a tropical estuary: a novel molecular approach. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 2001;65(18):3109–3122. doi: 10.1016/S0016-7037(01)00641-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horner JD, Cates RG, Gosz JR. Tannin, nitrogen, and cell wall composition of green vs senescent Douglas-fir foliage. Oecologia. 1987;72(4):515–519. doi: 10.1007/BF00378976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones CG, Hartley SE. A protein competition model of phenolic allocation. Oikos. 1999;86(1):27–44. doi: 10.2307/3546567. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Killingbeck KT. Nutrients in senesced leaves: keys to the search for potential resorption and resorption proficiency. Ecology. 1996;77(6):1716–1727. doi: 10.2307/2265777. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kleiner KW, Raffa KF, Dickson RE. Partitioning of 14C-labeled photosynthate to allelochemicals and primary metabolites in source and sink leaves of aspen: evidence for secondary metabolite turnover. Oecologia. 1999;119(3):408–418. doi: 10.1007/s004420050802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koricheva J. Interpreting phenotypic variation in plant allelochemistry: problems with the use of contents. Oecologia. 1999;119(4):467–473. doi: 10.1007/s004420050809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kraus TEC, Dahlgren RA, Zasoski RJ. Tannins in nutrient dynamics of forest ecosystems—a review. Plant and Soil. 2003;256(1):41–66. doi: 10.1023/A:1026206511084. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kraus TEC, Zasoski RJ, Dahlgren RA. Fertility and pH effects on polyphenol and condensed tannin contents in foliage and roots. Plant and Soil. 2004;262(1-2):95–109. doi: 10.1023/B:PLSO.0000037021.41066.79. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuhajek JM, Payton IJ, Monks A. The impact of defoliation on the foliar chemistry of southern rata (Metrosideros umbellata) New Zealand Journal of Ecology. 2006;30(2):237–249. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuiters AT. Role of phenolic substances from decomposing forest litter in plant-soil interactions. Acta Botanica Neerlandica. 1990;27(4):329–348. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lambers H, Chapin FS, Pons TL. Plant Physiological Ecology. New York, USA: Springer-Verlag; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin YM, Liu JW, Xiang P, Lin P, Ye GF, Sternberg LdaSL. Tannin dynamics of propagules and leaves of Kandelia candel and Bruguiera gymnorrhiza in the Jiulong River Estuary, Fujian, China. Biogeochemistry. 2006;78(3):343–359. doi: 10.1007/s10533-005-4427-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin YM, Liu JW, Xiang P, Lin P, Ding ZH, Sternberg LdaSL. Tannins and nitrogen dynamics in mangrove leaves at different age and decay stages (Jiulong River Estuary, China) Hydrobiologia. 2007;583(1):285–295. doi: 10.1007/s10750-006-0568-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Loomis WE. Growth-differentiation balance versus carbo-hydrate-nitrogen ratio. Proceedings of the American Society for Horticultural Science. 1932;29:240–245. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lorio PLJr. Growth differentiation-balance: a basis for understanding southern pine beetle-tree interactions. Forest Ecology and Management. 1986;14(4):259–273. doi: 10.1016/0378-1127(86)90172-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mae T, Makino A, Ohira K. Changes in the amounts of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase synthesized and degraded during the life span of rice leaf (Oryza sativa L.) Plant and Cell Physiology. 1983;24(6):1079–1086. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mafongoya PL, Giller KE, Palm CA. Decomposition and nitrogen release patterns of tree prunings and litter. Agroforestry Systems. 1997;38(1-3):77–97. doi: 10.1023/A:1005978101429. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mafongoya PL, Nair PKR, Dzowela BH. Mineralization of nitrogen from decomposing leaves of multipurpose trees as affected by their chemical composition. Biology and Fertility of Soils. 1998;27(2):143–148. doi: 10.1007/s003740050412. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Makkar HPS, Dawra RK, Singh B. Protein precipitation assay for quantitation of tannins: determination of protein in tannin-protein complex. Analytical Biochemistry. 1987;166(2):435–439. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90596-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Makkar HPS, Dawra RK, Singh B. Changes in tannin content, polymerisation and protein precipitation capacity in oak (Quercus incana) leaves with maturity. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 1988;44(4):301–307. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.2740440403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mansfield JL, Curtis PS, Zak DR, Pregitzer KS. Genotypic variation for condensed tannin production in trembling aspen (Populus tremuloides, Salicaceae) under elevated CO2 and in high- and low-fertility soil. American Journal of Botany. 1999;86(8):1154–1159. doi: 10.2307/2656979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martin JS, Martin MM. Tannin assays in ecological studies: lack of correlation between phenolics, proanthocyanidins and protein-precipitating constituents in mature foliage of six oak species. Oecologia. 1982;54(2):205–211. doi: 10.1007/BF00378394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matthews S, Mila I, Scalbert A, Donnelly DMX. Extractable and non-extractable proanthocyanidins in barks. Phytochemistry. 1997;45(2):405–410. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(96)00873-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McKey D. Adaptive patterns in alkaloid physiology. The American Naturalist. 1974;108(961):305–320. doi: 10.1086/282909. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mooney HA, Gulmon SL. Constraints on leaf structure and function in reference to herbivory. BioScience. 1982;32(3):198–206. doi: 10.2307/1308943. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moorby J, Wareing PF. Ageing in woody plants. Annals of Botany. 1963;27(2):291–308. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morton JF. The Australian pine or beefwood (Casuarina equisetifolia L.), an invasive “weed” in Florida. Proceedings of the Florida State Horticultural Society. 1980;93:87–95. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Northup RR, Dahlgren RA, McColl JG. Polyphenols as regulators of plant-litter-soil interactions in northern California’s pygmy forest: a positive feedback? Biogeochemistry. 1998;42(1-2):189–220. doi: 10.1023/A:1005991908504. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Okuda T, Yoshida T, Hatano T, Yazaki K, Ashida M. Ellagitannins of the casuarinaceae, stachyuraceae and myrtaceae. Phytochemistry. 1980;21(12):2871–2874. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(80)85058-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Osborne NJT, McNeill DM. Characterisation of Leucaena condensed tannins by size and protein precipitation capacity. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 2001;81(11):1113–1119. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.920. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pinyopusarerk K, House APN. Casuarina: An Annotated Bibliography of C. equisetifolia, C. junghuhniana and C. oligodon. Nairobi, Kenya: International Centre for Research in Agrogorestry; 1993. p. 296. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pinyopusarerk K, Williams ER. Range-wide provenance variation in growth and morphological characteristics of Casuarina equisetifolia grown in Northern Australia. Forest Ecology and Management. 2000;134(1-3):219–232. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1127(99)00260-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Riipi M, Ossipov V, Lempa K, Haukioja E, Koricheva J, Ossipova S, Pihlaja K. Seasonal changes in birch leaf chemistry: are there trade-offs between leaf growth, and accumulation of phenolics? Oecologia. 2002;130(3):380–390. doi: 10.1007/s00442-001-0826-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rossiter MC, Schultz JC, Baldwin IT. Relationships among defoliation, red oak phenolics, and gypsy moth growth and reproduction. Ecology. 1988;69(1):267–277. doi: 10.2307/1943182. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Salminen JP, Ossipov V, Haukioja E, Pihlaja K. Seasonal variation in the content of hydrolysable tannins in leaves of Betula pubescens . Phytochemistry. 2001;57(1):15–22. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)00502-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Serrano L. Leaching from vegetation of soluble polyphenolic compounds, and their abundance in temporary ponds in the Doñana National Park (SW Spain) Hydrobiologia. 1992;229(1):43–50. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Teklay T. Seasonal dynamics in the concentrations of micronutrients and organic constituents in green and senesced leaves of three agroforestry species in southern Ethiopia. Plant and Soil. 2004;267(1-2):297–307. doi: 10.1007/s11104-005-0124-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Terrill TH, Rowan AM, Douglas GD, Barry TN. Determination of extractable and bound condensed tannin contents in forage plants, protein concentrate meals and cereal grains. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 1992;58(3):321–329. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.2740580306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tuomi J. Toward integration of plant defence theories. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 1992;7(11):365–367. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(92)90005-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wareing PF. Problems of juvenility and flowering in trees. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 1959;56(366):282–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8339.1959.tb02504.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhong CL, Bai JY, Zhang Y. Introduction and conservation of Casuarina trees in China. Forest Research. 2005;18(3):345–350. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zucker WV. Tannins: does structure determine function An ecological perspective. The American Naturalist. 1983;121(3):335–365. doi: 10.1086/284065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]