Abstract

Background:

Interrelationships among the ACE deletion/insertion (D/I) polymorphism (rs1799752), migraine, and cardiovascular disease (CVD) are biologically plausible but remain controversial.

Methods:

Association study among 25,000 white US women, participating in the Women’s Health Study, with information on the ACE D/I polymorphism. Migraine and migraine aura status were self-reported. Incident CVD events were confirmed after medical record review. We used logistic regression to investigate the genotype-migraine association and proportional hazards models to evaluate the interrelationship among genotype, migraine, and incident CVD.

Results:

At baseline, 4,577 (18.3%) women reported history of migraine; 39.5% of the 3,226 women with active migraine indicated aura. During 11.9 years of follow-up, 625 CVD events occurred. We did not find an association of the ACE D/I polymorphism with migraine or migraine aura status. There was a lack of association between the ACE D/I polymorphism and incident major CVD, ischemic stroke, and myocardial infarction. Migraine with aura doubled the risk for CVD, but only for carriers of the DD (multivariable-adjusted relative risk [RR] = 2.10; 95% CI = 1.22–3.59; p = 0.007) and DI genotype (multivariable-adjusted RR = 2.31; 95% CI = 1.52–3.51; p < 0.0001). The risk was not significant among carriers of the II genotype, a pattern we observed for myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke.

Conclusions:

Data from this large cohort of women do not suggest an association of the ACE deletion/insertion (D/I) polymorphism with migraine, migraine aura status, or cardiovascular disease (CVD). The increased risk for CVD among migraineurs with aura was only apparent for carriers of the DD/DI genotype. Due to limited number of outcome events, however, future studies are warranted to further investigate this association.

GLOSSARY

- ACE

= angiotensin-converting enzyme;

- CI

= confidence interval;

- CVD

= cardiovascular disease;

- D/I

= deletion/insertion;

- HRs

= hazard ratios;

- IHS

= International Headache Society;

- MI

= myocardial infarction;

- OR

= odds ratio;

- WHS

= Women’s Health Study.

Migraine is a common debilitating headache disorder with a complex etiology, in which heredity plays an important role.1,2 Current pathophysiologic concepts are based on the neurovascular hypothesis.3 Vascular dysfunctions are of particular interest since population-based studies have established an increased risk for ischemic stroke and other ischemic vascular events among patients with migraine, in particular migraine with aura.4–6 In addition, effective treatment of both migraine7 and cardiovascular disease8 with drugs inhibiting the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) suggests a link between migraine and cardiovascular disease. Further, the deletion/insertion (D/I) polymorphism (rs1799752) in the ACE gene may be implicated in both migraine and cardiovascular disease (CVD).

Clinic-based case-control studies of limited sample size have associated the ACE D/I polymorphism with overall migraine,9–12 migraine with aura,10,12,13 and migraine without aura.12,14 However, whether the mode of association and whether the risk for migraine is increased or reduced by a certain genotype is unclear.

The relationship between the ACE D/I polymorphism and CVD is equally controversial. Meta-analyses of case-control studies found only weak associations of the ACE DD genotype with ischemic stroke15–17 or myocardial infarction.18 In addition, one cohort study suggested that the ACE D/I polymorphism is not a strong risk factor for myocardial infarction.19

The Women’s Health Study (WHS) provides the opportunity to investigate whether 1) the ACE D/I polymorphism is associated with migraine or migraine aura status; 2) the ACE D/I polymorphism is associated with incident CVD; and 3) the previously identified increased risk of CVD among migraineurs with aura is modified according to ACE D/I genotype status.

METHODS

Study population.

The WHS was a randomized trial designed to test the benefits and risks of low-dose aspirin and vitamin E in the primary prevention of CVD and cancer among apparently healthy women. The design, methods, and results have been described in detail previously.20,21 Briefly, a total of 39,876 US female health professionals aged ≥45 years at baseline in 1993 without a history of CVD, cancer, or other major illnesses were randomly assigned to active aspirin (100 mg on alternate days), active vitamin E (600 IU on alternate days), both active agents, or both placebos. All participants provided written informed consent and the Institutional Review Board of Brigham and Women’s Hospital approved the WHS. Baseline information was self-reported and collected by a mailed questionnaire that asked about many cardiovascular risk factors and lifestyle variables.

Blood samples were collected in tubes containing EDTA from 28,345 participating women prior to randomization. After excluding participants with missing information on migraine, ACE D/I polymorphism, and with reported CVD or angina prior to receiving the baseline questionnaire, a total of 26,428 women remained in the data set. We further excluded non-Caucasian women (n = 1,428) to avoid race-specific genetic interaction, leaving 25,000 Caucasian women for analyses.

Assessment of migraine.

Participants were asked on the baseline questionnaire “Have you ever had migraine headaches?” and “In the past year, have you had migraine headaches?” From this information, we categorized women into “any history of migraine”; “active migraine,” which includes women with self-reported migraine during the past year; and “prior migraine,” which includes women who reported ever having had a migraine but none in the year prior to completing the baseline questionnaire. In a previous study,4 we have shown good agreement with 1988 International Headache Society (IHS) criteria for migraine.22 Participants who reported active migraine were further asked whether they had an “aura or any indication a migraine is coming.” Responses were used to classify women who reported active migraine into active migraine with aura and active migraine without aura.

Ascertainment of cardiovascular disease.

During follow-up, participants self-reported cardiovascular events. Medical records were obtained for all cardiovascular events and reviewed by an Endpoints Committee of physicians. Nonfatal stroke was confirmed if the participant had a new focal-neurologic deficit of sudden onset that persisted for >24 hours. Based on available clinical and diagnostic information, strokes were then classified into major subtypes (ischemic, hemorrhagic, or unknown) with excellent interrater agreement.23 The occurrence of myocardial infarction was confirmed if symptoms met World Health Organization criteria and if the event was associated with abnormal levels of cardiac enzymes or abnormal electrocardiograms. Cardiovascular deaths were confirmed by review of autopsy reports, death certificates, medical records, or information obtained from next of kin or family members.

We evaluated the association between migraine and ACE D/I genotypes with major CVD, a combined endpoint defined as the first of any of these events: nonfatal ischemic stroke, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or death from ischemic CVD. We also evaluated the association with any first ischemic stroke and any first myocardial infarction. However, there were too few deaths due to CVD to conduct meaningful analyses.

Genotype determination of the ACE D/I polymorphism (rs1799752).

Genotyping was performed in the context of a multimarker assay using an immobilized probe approach, as previously described (Roche Molecular Systems).24 In brief, each DNA sample was amplified by PCR with biotinylated primers. Each PCR product pool was then hybridized to a panel of sequence-specific oligonucleotide probes immobilized in a linear array. The colorimetric detection method was based on the use of streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase conjugate with hydrogen peroxidase and 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine as substrates. Linear array processing was facilitated by the use of the AutoRELI-Mark II (Dynal Biotech). Genotype assignment was performed using the proprietary Roche Molecular Systems StripScan image processing software. To confirm genotype assignment, scoring was carried out by two independent observers. Discordant results (<1% of all scoring) were resolved by a joint reading, and where necessary, a repeat genotyping.

Statistics.

M. Schürks (Division of Preventive Medicine) and R.Y. Zee (Division of Preventive Medicine) conducted the statistical analysis. We present baseline characteristics of participants with respect to their ACE D/I genotype using descriptive statistics. Genotype and allele frequencies were compared according to migraine and migraine aura status using the χ2 test.

We used logistic regression models to evaluate the association between ACE D/I genotypes and migraine. We calculated odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) from separate models for 1) any history of migraine, 2) active migraine with aura, 3) active migraine without aura, and 4) prior migraine. We built age-adjusted and multivariable-adjusted models. The multivariable-adjusted models included the following covariates: age (continuous), body mass index (continuous), exercise (never, less than once/week, 1–3 times/week, 4 or more times/week), postmenopausal hormone use (never, past, current), history of oral contraceptive use (yes, no, not sure), history of hypertension (yes, no), history of diabetes (yes, no), alcohol consumption (never, 1–3 drinks/month, 1–6 drinks/week, ≥1 drinks/day), smoking (never, past, current <15 cigarettes/day, current ≥15 cigarettes/day), and family history of myocardial infarction prior to age 60 (yes, no, unknown). Including indicator variables for randomized treatment assignment did not alter the effect estimates for any of the models presented. We incorporated a missing value indicator if the number of women with missing information on covariates was ≥100. For covariates with missing information on <100 women, those were either grouped into the reference category or the past exposure category, if applicable.

We used Cox proportional hazards models to evaluate the association between ACE D/I genotypes as well as migraine with incident cardiovascular events. We calculated multivariable-adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and their 95% CIs including the same covariates as mentioned before.

We tested the proportionality assumption of the Cox proportional hazards models by including an interaction term for the ACE D/I polymorphism and migraine status with time, respectively, and found no significant violation.

We built additive models to investigate the association of the ACE D/I polymorphism with migraine and incident CVD events. This model assumes that the risk for carriers of the heterozygous DI genotype for developing the outcome is halfway between carriers of the homozygous genotypes (DD and II). The advantage of this model is that the strength of genotype-phenotype association is expressed in a single parameter (beta estimate) and statistical tests for detecting a relationship have only one degree of freedom.25 We checked for deviation from additivity by adding a dominance variable to the model (extended model). This variable was coded as 0 for homozygotes and 1 for heterozygotes.25 We compared the overall fit of the additive and the extended model using the likelihood ratio test. We also evaluated the association between migraine and incident CVD stratified by ACE D/I genotype status.

All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). All p values were two-tailed and we considered p < 0.05 as significant. Since we evaluated biologically plausible associations between only one polymorphism, migraine, and CVD, we did not further adjust p values.

RESULTS

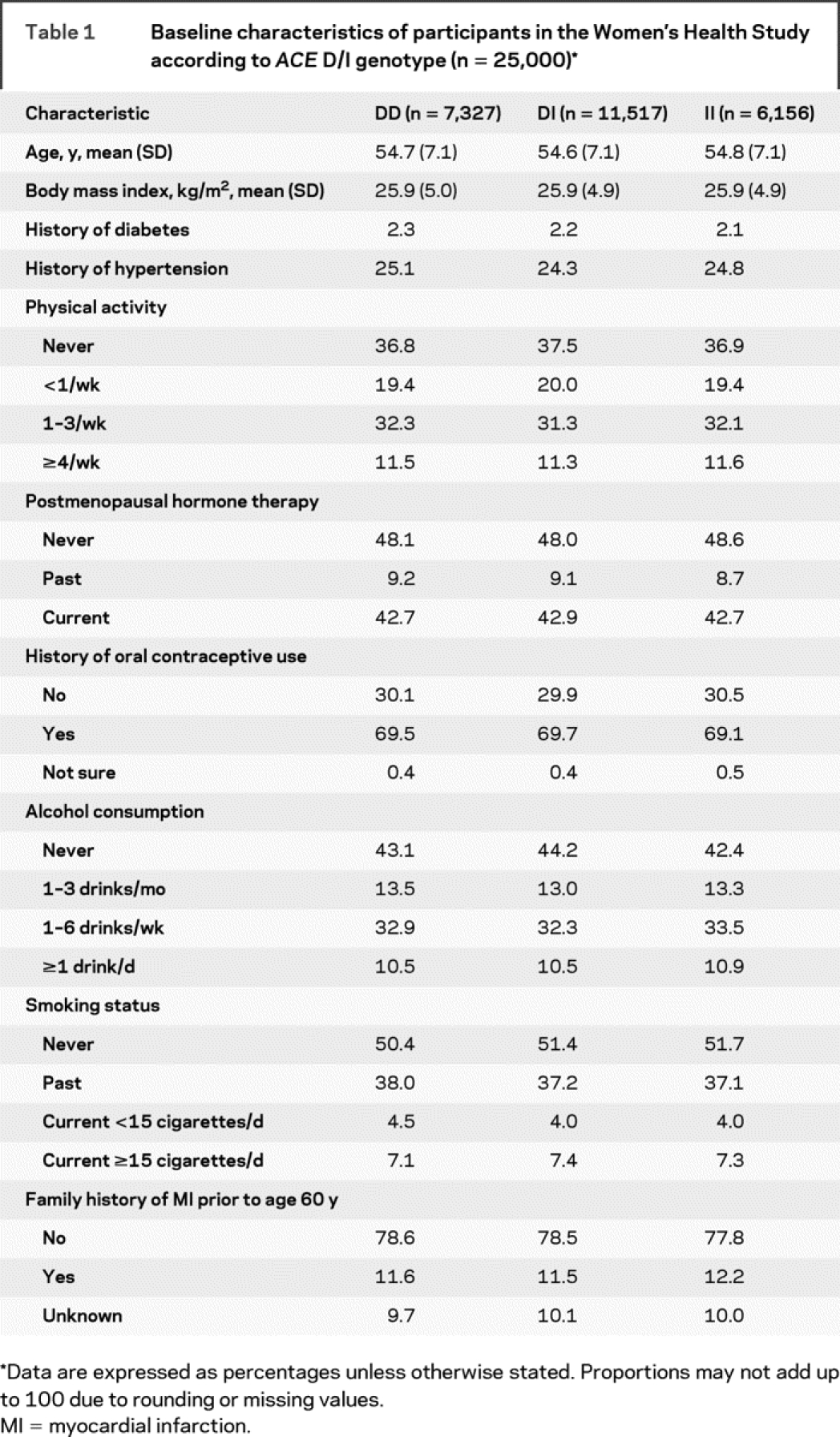

The baseline characteristics of women according to ACE D/I genotype are summarized in table 1. Age, body mass index, history of diabetes, and history of hypertension were equally distributed among genotypes. Women also did not differ regarding physical activity, postmenopausal hormone therapy, history of oral contraceptive use, alcohol consumption, smoking habits, and family history of myocardial infarction.

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of participants in the Women’s Health Study according to ACE D/I genotype (n = 25,000)

At baseline, 4,577 (18.3%) women reported any history of migraine. Active migraine was reported by 3,226 women. Among those, 1,275 (39.5%) indicated migraine aura. The observed genotype distribution for the ACE D/I polymorphism deviated from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium both among women with no history of migraine and among women with migraine (χ2 with 1 degree of freedom: p < 0.0001). There was no difference in the genotype and allele distribution for ACE D/I between women with and without migraine (table e-1 on the Neurology® Web site at www.neurology.org).

Since the results from the age-adjusted and multivariable-adjusted models were almost identical for both the logistic regression analyses and for the Cox proportional hazards analyses, we only present the results from the multivariable-adjusted models.

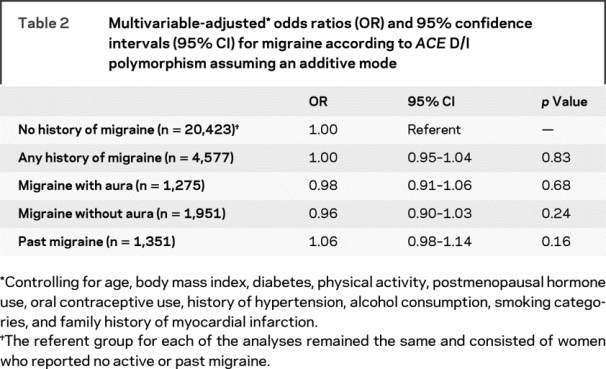

Results from the logistic regression analysis showed no association between ACE D/I polymorphism and any history of migraine (table 2). The multivariable-adjusted OR in the additive mode was 1.00 (95% CI = 0.95–1.04; p = 0.83). Further, we did not find an association with migraine subgroups. We did not find strong evidence for deviation from additivity.

Table 2 Multivariable-adjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for migraine according to ACE D/I polymorphism assuming an additive mode

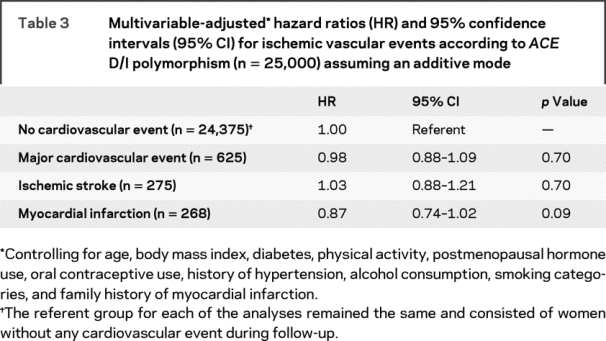

During a mean of 11.9 years of follow-up (296,853 person-years), 625 first major CVD events, 275 ischemic strokes, and 268 myocardial infarctions were confirmed. The ACE D/I polymorphism was not associated with increased risk of incident major CVD, incident ischemic stroke, and incident myocardial infarction (table 3). Again, we did not find strong evidence for deviation from additivity.

Table 3 Multivariable-adjusted hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for ischemic vascular events according to ACE D/I polymorphism (n = 25,000) assuming an additive mode

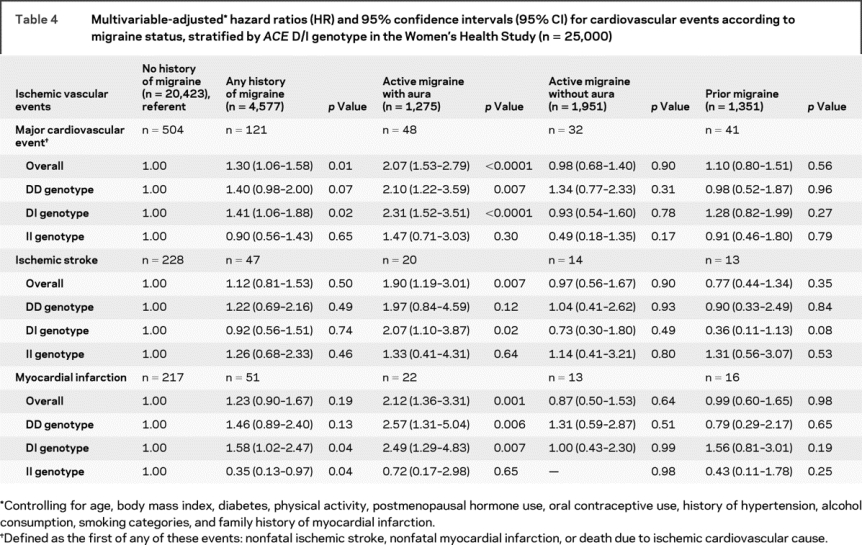

In table 4, we summarize the association between migraine status and incident ischemic cardiovascular events. Compared with women without migraine, women with any history of migraine had increased risk for major CVD (multivariable-adjusted HR 1.30; 95% CI 1.06–1.58; p = 0.01). This elevated risk was only apparent for women with active migraine with aura (multivariable-adjusted HR = 2.07; 95% CI = 1.53–2.79; p < 0.0001). This pattern occurred for ischemic stroke (multivariable-adjusted HR = 1.90; 95% CI = 1.19–3.01; p = 0.007) and myocardial infarction (multivariable-adjusted HR = 2.12; 95% CI = 1.36–3.31; p = 0.001). The stratified analysis shows that the increased risk for major CVD among migraineurs with aura occurred only for carriers of the ACE DD (multivariable-adjusted RR = 2.10; 95% CI = 1.22−3.59; p = 0.007) and DI genotype (multivariable-adjusted RR = 2.31; 95% CI = 1.52−3.51; p < 0.0001), but not for carriers of the II genotype (multivariable-adjusted HR = 1.47; 95% CI = 0.71−3.03; p = 0.03). This pattern of lack of association for the II genotype was apparent for both ischemic stroke (multivariable-adjusted HR = 1.33; 95% CI = 0.41–4.31; p = 0.64) and myocardial infarction (multivariable-adjusted HR = 0.72; 95% CI = 0.17–2.98; p = 0.65).

Table 4 Multivariable-adjusted hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for cardiovascular events according to migraine status, stratified by ACE D/I genotype in the Women’s Health Study (n = 25,000)

When we tested whether the association between migraine aura status (i.e., evaluating women with migraine with aura and women with migraine without aura) and incident major CVD was modified by genotype status among the entire cohort, the results were not significant (p for interaction = 0.13 assuming an age-adjusted and 0.16 assuming a multivariable-adjusted recessive model).

DISCUSSION

In this large study of Caucasian women, we found no association between the ACE D/I polymorphism and migraine or migraine aura status as well as no association between the ACE D/I polymorphism and incident major CVD, including myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke. Migraine with aura was associated with a twofold increased risk of major CVD. This increased risk, however, was only significant among carriers of the ACE DD/DI genotype, a pattern appearing for ischemic stroke and myocardial infarction.

Prior studies investigating the association between the ACE D/I polymorphism and migraine are contradictory.9–11,13,14 While one study suggested that the ACE DD genotype increases the risk for overall migraine, but not for migraine-specific subgroups,9 others showed an increased risk for migraine without aura,14 migraine with aura,13 and for overall migraine, with the strongest risk for migraine with aura.10 Further, one study suggested a protective effect for overall migraine,11 and findings from a recent one do not indicate an association at all.12 The different results may be due to targeting different study populations, differences in ethnicity, or small sample size.

Based on available data, the following pathophysiologic association may be sketched: ACE DD genotype is associated with migraine with aura,13 because the ACE D allele results in higher ACE levels,26 and higher ACE levels are found in migraineurs with aura.27 However, our data do not support this association. Reasons for this may include that a pathophysiologic association is specific to certain ethnic populations, for example Japanese.13,27 In addition, the ACE D/I polymorphism accounts for only about 50% of ACE activity variation,28 and elevated ACE activities may also be attributable to copy number variations of the ACE gene. These copy number variations account for a large amount of genetic heterogeneity and have been associated with various disorders.29

The relationship between the ACE D/I polymorphism and CVD is equally controversial. A meta-analysis of case-control studies18 and a prospective population-based study19 found that the ACE DD genotype is not a strong risk factor for myocardial infarction. The results of a case-control study among postmenopausal women indicated that the ACE DD genotype may be associated with myocardial infarction/angina, in particular among postmenopausal hormone users.30 Meta-analyses of case-control studies found only a weak association of the ACE DD genotype with ischemic stroke.15–17 Our results, however, do not suggest that the ACE D/I polymorphism alters the risk for incident major CVD, myocardial infarction, or ischemic stroke. The discrepant results may be due to differences in study design and due to population-specific gene–gene and gene–environment interactions.15,18

The complex relationship between genetic variants, migraine, and CVD has been the focus of recent studies. Migraine with aura has been shown to increase the risk of CVD by approximately twofold.4,5,31 Further, we have shown that this increased risk was magnified for carriers of the TT genotype of the MTHFR 677C>T polymorphism, which was driven by a selective fourfold increased risk of ischemic stroke.32 These results may suggest in part differential pathophysiologic mechanisms in the migraine with aura–ischemic stroke and migraine with aura–myocardial infarction association and are plausible considering the complexity of CVD pathophysiology.5,33

Results from the present study suggest that the increased risk for CVD among women with migraine with aura is only significant for carriers of the ACE DD/DI genotype, but not for carriers of the II genotype when contrasted to women without migraine. However, the number of outcome events in subgroups was considerably small and, as a consequence, the CIs are wide, indicating remaining uncertainties. Indeed, when we tested whether the association between migraine aura status and incident major CVD was modified by genotype status in the entire cohort, the results were not significant. However, this does not necessarily contradict our findings that a modifying effect is limited to the subgroup of patients with migraine with aura. In addition, a differential association is plausible. For example, higher plasma ACE activities among carriers of the ACE DD/DI genotype increase angiotensin II levels, thus boosting the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) activity and mediating the migraine with aura-CVD association. Since elevated angiotensin II levels may also result from non-ACE enzymes like chymase or cathepsins,34 our results of a differential impact of the RAS on this association may have been further diluted. Unfortunately, we could not further investigate these hypotheses, since plasma ACE activities or angiotensin II levels were not available.

To further understand the complex interrelationship between migraine and CVD, investigating potential modifying effects of other genetic variants in the RAS and those implicated in migraine or CVD may be promising. In addition, gene–gene and gene–environment interactions need to be considered. Particularly interactions of the MTHFR 677C>T and ACE D/I polymorphisms seem plausible,10,35 but also between genes and underlying vascular risk status.5

Our study has several strengths, including the large number of participants with and without migraine and high incidence of confirmed CVD events. Further, information on a large number of potential CVD risk factors was available and the homogenous nature of the cohort, consisting only of Caucasian women, may reduce confounding. However, several limitations of our study should be considered. First, migraine and aura status were self-reported and were not classified according to strict IHS criteria. Thus, nondifferential misclassification is possible. However, the prevalence of migraine (18.3%) and the prevalence of migraine aura among women with active migraine (39.5%) is similar to those seen in other large population-based studies in the United States36 and the Netherlands.37 The 1-year prevalence of migraine for women was 18.2% in the United States and 25% in the Netherlands, while migraine aura was reported by 37% in the United States36 and 31% in the Netherlands.37 Furthermore, we have previously shown good agreement of our migraine classification with IHS criteria for migraine.4 Second, the genotype distribution deviated from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. Since genotypes of both women with migraine and women without migraine were in Hardy-Weinberg disequilibrium, this is an unlikely indication for genotype-based differential survival. In addition, genotyping error is unlikely given our stringent genotyping protocol. However, this stringency together with the fact that participants were all white female health professionals age ≥45 years, not representing all white women, most likely accounts for the deviation from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. Thus, generalizability may be limited. Finally, we cannot exclude that examination of a different polymorphism not in linkage disequilibrium with the variant tested might lead to a different result. Thus, the ACE DD/DI genotype may only be a marker for an increased risk of CVD among patients with migraine with aura.

Future studies need to replicate our findings in other large cohorts with information on migraine and aura status according to IHS criteria. Age- and gender-specific effects must be considered and gene–gene interactions explored. Further understanding factors increasing the likelihood of migraine or increasing the risk of CVD among patients with migraine with aura may help to develop preventive strategies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank the participants in the Women’s Health Study for their commitment and cooperation and the Women’s Health Study staff for their assistance.

DISCLOSURE

Dr. Zee has received within the last 5 years research support from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, the Leducq Foundation, the Donald W. Reynolds Foundation, and Roche. Dr. Buring has received within the last 5 years investigator-initiated research funding and support as Principal Investigator from the National Institutes of Health (the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the National Cancer Institute, and the National Institute of Aging) and Dow Corning Corporation; research support for pills and/or packaging from Bayer Heath Care and the Natural Source Vitamin E Association; and honoraria from Bayer for speaking engagements. Dr. Schürks has received within the last 5 years investigator-initiated research funds from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and an unrestricted research grant from Merck, Sharp and Dohme. Dr. Kurth has received within the last 5 years investigator-initiated research funding as Principal or Co-Investigator from the National Institutes of Health, Bayer AG, McNeil Consumer & Specialty Pharmaceuticals, Merck, and Wyeth Consumer Healthcare; he is a consultant to i3 Drug Safety and Whiscon; and he received honoraria from Organon for contributing to an expert panel and from Genzyme and Pfizer for educational lectures. Dr. Schürks and Dr. Zee take full responsibility for the data, the analysis and interpretation, and the conduct of the research; they had full access to all of the data; and they have the right to publish any and all data, separate and apart from the attitudes of the sponsor.

Supplementary Material

Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Markus Schürks, Division of Preventive Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, 900 Commonwealth Avenue East, 3rd Fl, Boston, MA 02215-1204 mschuerks@rics.bwh.harvard.edu

Supplemental data at www.neurology.org

*These authors contributed equally.

The Women’s Health Study is supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL-43851 and HL-080467) and the National Cancer Institute (CA-47988). The research for this work was supported by grants from the Donald W. Reynolds Foundation, the Leducq Foundation, and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. F. Hoffmann La-Roche and Roche Molecular Systems, Inc., also supported the genotype determination financially and with in-kind contribution of reagents and consumables. Dr. Schürks was supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SCHU 1553/2-1). The funding agencies played no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Disclosure: Author disclosures are provided at the end of the article.

Received May 29, 2008. Accepted in final form November 19, 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ligthart L, Boomsma DI, Martin NG, Stubbe JH, Nyholt DR. Migraine with aura and migraine without aura are not distinct entities: further evidence from a large Dutch population study. Twin Res Hum Genet 2006;9:54–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mulder EJ, Van Baal C, Gaist D, et al. Genetic and environmental influences on migraine: a twin study across six countries. Twin Res 2003;6:422–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pietrobon D, Striessnig J. Neurobiology of migraine. Nat Rev Neurosci 2003;4:386–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kurth T, Gaziano JM, Cook NR, Logroscino G, Diener HC, Buring JE. Migraine and risk of cardiovascular disease in women. JAMA 2006;296:283–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kurth T, Schürks M, Logroscino G, Gaziano JM, Buring JE. Migraine, vascular risk, and cardiovascular events in women: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2008;337:a636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pezzini A, Grassi M, Del Zotto E, et al. Migraine mediates the influence of C677T MTHFR genotypes on ischemic stroke risk with a stroke-subtype effect. Stroke 2007;38:3145–3151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schrader H, Stovner LJ, Helde G, Sand T, Bovim G. Prophylactic treatment of migraine with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (lisinopril): randomised, placebo controlled, crossover study. BMJ 2001;322:19–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nilsson PM. Optimizing the pharmacologic treatment of hypertension: BP control and target organ protection. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs 2006;6:287–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kara I, Ozkok E, Aydin M, et al. Combined effects of ACE and MMP-3 polymorphisms on migraine development. Cephalalgia 2007;27:235–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lea RA, Ovcaric M, Sundholm J, Solyom L, Macmillan J, Griffiths LR. Genetic variants of angiotensin converting enzyme and methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase may act in combination to increase migraine susceptibility. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 2005;136:112–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin JJ, Wang PJ, Chen CH, Yueh KC, Lin SZ, Harn HJ. Homozygous deletion genotype of angiotensin converting enzyme confers protection against migraine in man. Acta Neurol Taiwan 2005;14:120–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tronvik E, Stovner LJ, Bovim G, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme gene insertion/deletion polymorphism in migraine patients. BMC Neurol 2008;8:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kowa H, Fusayasu E, Ijiri T, et al. Association of the insertion/deletion polymorphism of the angiotensin I-converting enzyme gene in patients of migraine with aura. Neurosci Lett 2005;374:129–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paterna S, Di Pasquale P, D’Angelo A, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme gene deletion polymorphism determines an increase in frequency of migraine attacks in patients suffering from migraine without aura. Eur Neurol 2000;43:133–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Casas JP, Hingorani AD, Bautista LE, Sharma P. Meta-analysis of genetic studies in ischemic stroke: thirty-two genes involving approximately 18,000 cases and 58,000 controls. Arch Neurol 2004;61:1652–1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ariyaratnam R, Casas JP, Whittaker J, Smeeth L, Hingorani AD, Sharma P. Genetics of ischaemic stroke among persons of non-European descent: a meta-analysis of eight genes involving approximately 32,500 individuals. PLoS Med 2007;4:e131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma P. Meta-analysis of the ACE gene in ischaemic stroke. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1998;64:227–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morgan TM, Coffey CS, Krumholz HM. Overestimation of genetic risks owing to small sample sizes in cardiovascular studies. Clin Genet 2003;64:7–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sayed-Tabatabaei FA, Schut AF, Vasquez AA, et al. Angiotensin converting enzyme gene polymorphism and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality: the Rotterdam Study. J Med Genet 2005;42:26–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rexrode KM, Lee IM, Cook NR, Hennekens CH, Buring JE. Baseline characteristics of participants in the Women’s Health Study. J Womens Health Gend Based Med 2000;9:19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ridker PM, Cook NR, Lee IM, et al. A randomized trial of low-dose aspirin in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in women. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1293–1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Classification and diagnostic criteria for headache disorders, cranial neuralgias and facial pain: Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. Cephalalgia 1988;8 suppl 7:1–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Atiya M, Kurth T, Berger K, Buring JE, Kase CS. Interobserver agreement in the classification of stroke in the Women’s Health Study. Stroke 2003;34:565–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheng S, Grow MA, Pallaud C, et al. A multilocus genotyping assay for candidate markers of cardiovascular disease risk. Genome Res 1999;9:936–949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cordell HJ, Clayton DG. Genetic association studies. Lancet 2005;366:1121–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tiret L, Rigat B, Visvikis S, et al. Evidence, from combined segregation and linkage analysis, that a variant of the angiotensin I-converting enzyme (ACE) gene controls plasma ACE levels. Am J Hum Genet 1992;51:197–205. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fusayasu E, Kowa H, Takeshima T, Nakaso K, Nakashima K. Increased plasma substance P and CGRP levels, and high ACE activity in migraineurs during headache-free periods. Pain 2007;128:209–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rigat B, Hubert C, Alhenc-Gelas F, Cambien F, Corvol P, Soubrier F. An insertion/deletion polymorphism in the angiotensin I-converting enzyme gene accounting for half the variance of serum enzyme levels. J Clin Invest 1990;86:1343–1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jakobsson M, Scholz SW, Scheet P, et al. Genotype, haplotype and copy-number variation in worldwide human populations. Nature 2008;451:998–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Methot J, Hamelin BA, Bogaty P, Arsenault M, Plante S, Poirier P. ACE-DD genotype is associated with the occurrence of acute coronary syndrome in postmenopausal women. Int J Cardiol 2005;105:308–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Etminan M, Takkouche B, Isorna FC, Samii A. Risk of ischaemic stroke in people with migraine: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ 2005;330:63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schürks M, Zee RY, Buring JE, Kurth T. Interrelationships among the MTHFR 677C>T polymorphism, migraine, and cardiovascular disease. Neurology 2008;71:505–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spence J. Homocysteine-lowering therapy: a role in stroke prevention? Lancet Neurol 2007;6:830–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmieder RE, Hilgers KF, Schlaich MP, Schmidt BM. Renin-angiotensin system and cardiovascular risk. Lancet 2007;369:1208–1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tietjen EG. Migraine and ischaemic heart disease and stroke: potential mechanisms and treatment implications. Cephalalgia 2007;27:981–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Diamond S, Diamond ML, Reed M. Prevalence and burden of migraine in the United States: data from the American Migraine Study II. Headache 2001;41:646–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Launer LJ, Terwindt GM, Ferrari MD. The prevalence and characteristics of migraine in a population-based cohort: the GEM study. Neurology 1999;53:537–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.