Abstract

Physiologic and pathogenic changes in amine release induce dramatic behavioral changes, but the underlying cellular mechanisms remain unclear. To investigate these adaptive processes, we have characterized mutations in the Drosophila vesicular monoamine transporter (dVMAT), which is required for the vesicular storage of dopamine, serotonin, and octopamine. dVMAT mutant larvae show reduced locomotion and decreased electrical activity in motoneurons innervating the neuromuscular junction (NMJ) implicating central amines in the regulation of these activities. A parallel increase in evoked glutamate release by the motoneuron is consistent with a homeostatic adaptation at the NMJ. Despite the importance of aminergic signaling for regulating locomotion and other behaviors, adult dVMAT homozygous null mutants survive under conditions of low population density, thus allowing a phenotypic characterization of adult behavior. Homozygous mutant females are sterile and show defects in both egg retention and development; males also show reduced fertility. Homozygotes show an increased attraction to light but are mildly impaired in geotaxis and escape behaviors. In contrast, heterozygous mutants show an exaggerated escape response. Both hetero- and homozygous mutants demonstrate an altered behavioral response to cocaine. dVMAT mutants define potentially adaptive responses to reduced or eliminated aminergic signaling and will be useful to identify the underlying molecular mechanisms.

AMINERGIC signaling pathways regulate a variety of complex behaviors in both the fly and mammals. In Drosophila melanogaster, dopamine is thought to regulate arousal (van Swinderen et al. 2004; Andretic et al. 2005; Kume et al. 2005), locomotion (Yellman et al. 1997; Chang et al. 2006), the behavioral effects of cocaine (McClung and Hirsh 1998, 1999; Torres and Horowitz 1998; Bainton et al. 2000), and vitellogenesis (Willard et al. 2006). Serotonin regulates visual pathways (Hevers and Hardie 1995; Chen et al. 1999), circadian rhythms (Shaw et al. 2000; Yuan et al. 2006), place memory (Sitaraman et al. 2008), and possibly ovarian follicle formation (Willard et al. 2006). Octopamine, which is structurally similar to noradrenaline, is involved in larval locomotion (Saraswati et al. 2004; Fox et al. 2006) and adult fertility (Monastirioti et al. 1996; Cole et al. 2005; Middleton et al. 2006). Many components of the aminergic signaling machinery responsible for these behaviors are evolutionarily conserved (Morgan et al. 1986; Budnik and White 1987; Konrad and Marsh 1987; Neckameyer and White 1993; Corey et al. 1994; Demchyshyn et al. 1994; Porzgen et al. 2001; Yuan et al. 2006; Draper et al. 2007; Schaerlinger et al. 2007); the behavioral responses of flies and humans to psychostimulants are also similar (McClung and Hirsh 1998; Bainton et al. 2000; Andretic et al. 2005). These similarities suggest that D. melanogaster may be used as a genetic model to study the molecular mechanisms by which amines regulate synaptic transmission and behavior.

Aminergic neurotransmission requires the presynaptic release of neurotransmitter and its subsequent reuptake at the nerve terminal. Two distinct types of neurotransmitter transporters are required for these activities: plasma membrane transporters that terminate the action of released neurotransmitter (Hahn and Blakely 2007; Torres and Amara 2007) and vesicular transporters that package the transmitters for regulated release (Liu and Edwards 1997; Erickson and Varoqui 2000; Eiden et al. 2004). In mammals, the neural isoform of the vesicular monoamine transporter, VMAT2, is responsible for the storage of dopamine, serotonin, and noradrenaline in all central aminergic neurons. A separate gene, VMAT1, is expressed at the periphery and in neuroendocrine cells (Liu and Edwards 1997; Erickson and Varoqui 2000; Eiden et al. 2004). In contrast, the genome of Caenorhabditis elegans contains a single VMAT ortholog (cat-1), thus simplifying the genetic analysis of vesicular amine transport (Duerr et al. 1999). Similarly, we have reported that the genome of D. melanogaster contains a single VMAT ortholog (dVMAT) that is expressed in all dopaminergic, serotonergic, and octopaminergic cells in both larvae and adults (Greer et al. 2005; Chang et al. 2006).

Heterozygous VMAT2 knockout mice (+/−) display a number of behavioral deficits including impairments in learned helplessness and conditioned place preference paradigms (Takahashi et al. 1997; Wang et al. 1997; Fukui et al. 2007). The synaptic mechanisms by which changes in VMAT2 expression alter these behaviors are not known. It also is unclear how the complete elimination of VMAT activity might affect complex behavior; VMAT2 homozygous knockouts die soon after birth and relatively limited information is available on the behavioral phenotype of cat-1 (Duerr et al. 1999). In addition, little is known about the relationship between changes in amine release and the function of downstream circuits (Nicola et al. 2000; Wolf et al. 2003). The modulation of glutamatergic neurons may be particularly important since interactions between dopamine and glutamate have been linked to both addiction and schizophrenia (Wolf et al. 2003; Carlsson 2006; Lewis and Gonzalez-Burgos 2006).

We are using the model organism D. melanogaster to study how changes in VMAT activity and amine release may alter synaptic transmission and behavior (Chang et al. 2006; Sang et al. 2007). We have shown previously that the dVMAT gene contains two splice variants, dVMAT-A and -B and that overexpression of DVMAT-A protein has a dramatic effect on amine-dependent behaviors (Greer et al. 2005; Chang et al. 2006). More recently, we have characterized mutations in the dVMAT gene, but limited our phenotypic characterization to the function of DVMAT-B, an isoform found exclusively in a small subset of glia in the visual system (Romero-Calderón et al. 2008). Here, we present a more in-depth characterization of the dVMAT loss-of-function alleles, focusing on the function of DVMAT-A, which is expressed in all dopaminergic, serotonergic, and octopaminergic neurons (Greer et al. 2005; Chang et al. 2006). Our results help define how monoamine release regulates glutamatergic motoneurons in the larva and a number of complex behaviors in the adult fly. In addition, our data on the survival and behavior of adult flies suggest that adaptive mechanisms may in some cases obviate the need for regulated aminergic signaling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Drosophila stocks and husbandry:

Drosophila stocks were raised in standard cornmeal/molasses/agar bottles or vials at room temperature (23°) with a relative humidity of 20–40% in a 12-hr dark/light cycle. Canton-S (CS) and w1118CS10 (w1118 outcrossed 10 times to Canton-S) were from our laboratory stocks (Simon et al. 2003). l(2)SH0459 (dVMATP1) was obtained from Oh et al. (2003), and was outcrossed 5 times to w1118CS10, and stocks of heterozygotes were kept over CyO balancer (dVMATP1/CyO). The generation of the imprecise excision allele dVMATΔ14 is described elsewhere (Romero-Calderón et al. 2008). The chromosomal deletion (deficiency) line Df(2R)CX1/SM1, deleted from 49C1 to 50D1 was obtained from the Bloomington Stock Center (stock no. 442), and Df(2R)MK2, deleted from 50A6 to 50C1–3 (Lekven et al. 1998), was a generous gift of Volker Hartenstein. For genetic rescue experiments, we used a previously described UAS-DVMAT-A transgene (Chang et al. 2006) recombined with the daughterless-GAL4 driver on the third chromosome. For electrophysiologic experiments, dVMAT mutants were maintained over a CyO balancer marked with Kr-GFP to facilitate the selection of homozygous mutant larvae.

To obtain large numbers of homozygous mutant adults for phenotypic analysis, we compromised between a higher percentage of expected homozygotes in sparse cultures and a higher absolute number of homozygotes in less sparse cultures (see results). We obtained ∼20–30% of expected homozygotes using 5–20 male:female pairs mated in bottles for ≤5 days.

Western blots:

Western blots were performed as previously described. Briefly, flies were anesthetized using CO2, and 20 heads per genotype homogenized in SDS–PAGE sample buffer. One head equivalent of homogenate from each fly line was loaded onto a polyacrylamide gel, followed by transfer to nitrocellulose. The upper half of each membrane was incubated with 1:4000 rabbit anti-DVMAT-N (Romero-Calderón et al. 2008) and the lower half was incubated with 1:1000 mouse anti-Late bloomer (Kopczynski et al. 1996) overnight at 4°. Membranes were incubated in secondary antibody for 45 min at room temperature using either 1:1000 anti-rabbit or 1:1000 anti-mouse HRP conjugated antibodies (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). The protein bands were detected using SuperSignal West Pico luminol/peroxide (Pierce, Rockford, IL) for 1 min and exposed for 5–60 sec on Kodak (Rochester, NY) Biomax Light film.

HPLC:

HPLC analysis of dopamine and serotonin was performed as previously described (Chang et al. 2006). To determine potential sex effects on amine content we used three heads per sample. For all other experiments we used four heads per sample, two male plus two female.

Ovarian morphology:

Females were collected as virgins within 8 hr of eclosion and aged together in vials for 3–4 days, either alone or with the same number of CS males. In some cases, as indicated in the text, yeast paste was added at 3 days after eclosion. Oocytes with long dorsal appendages (stage 14) were scored as “mature.” All dissections were carried out 4 days after eclosion. Females were anesthetized using CO2, killed by brief incubation in 75% ethanol, and dissected in PBS. The ovaries (10 per condition) were mounted in 50:50 PBS:glycerol and digital images obtained using a Zeiss AxioCam camera. Measurements of ovary size were made using Zeiss Axiovision software.

Electrophysiology:

Intracellular recordings from muscles were performed as described previously (Daniels et al. 2004). In brief, third instar larvae were selected from vials (homozygous mutants were selected by the absence of a Kr-GFP marker on the CyO balancer) and dissected in HL-3 saline (Stewart et al. 1994). HL-3 saline solution contains (in mm) 70 NaCl, 5 KCl, 20 MgCl2, 10 NaHCO3, 5 trehalose, 115 sucrose, 5 HEPES, 0.30 CaCl2, pH 7.20. Recordings were made from muscle 6 in segments A3 and A4 in the same solution using sharp glass electrodes with tip resistances between 14 and 27 MΩ. Cells were selected for analysis if the resting membrane potential was < −60 mV and if the muscle input resistance was at least 5 MΩ. For each cell, 70 consecutive spontaneous miniature events were measured using MiniAnal (Synaptosoft, Decatur, GA), taking care to exclude events with slow rise times that originate from the neighboring muscles. Evoked events were recorded while stimulating with 100 pulses at 2 Hz. The last 75 events were averaged to obtain the mean amplitude for each cell. Resting membrane potential was −66 ± 1 in w1118CS10 and −63 ± 1 in dVMATP1 homozygotes (P/P), P < 0.05, n = 17. Muscle input resistance was 7.1 ± 0.5 in w1118CS10, 12 ± 1.3 in P/P, P < 0.0005, n = 12.

Action potential recordings were performed following the protocol of Fox et al. (2006). Briefly, larvae were selected and dissected as above and then incubated in HL-3 solution containing 1.5 mm CaCl2 or HL-3.1 solution (Feng et al. 2004; “low Mg2+ saline”), containing (in mm) 70 NaCl, 5 KCl, 4 MgCl2, 10 NaHCO3, 5 trehalose, 115 sucrose, 5 HEPES, 1.5 CaCl2, pH 7.20. The segmental nerves were left intact and connected to the ventral nerve cord, and the preparation was not stretched tightly to allow for contraction. A polished electrode was used to suck up the segmental nerve for recording using a differential amplifier (model 410, Brownlee Precision, San Jose, CA). The signal was filtered using pClamp 9.0 software (Molecular Devices, Union City, CA) with a highpass filter set at 100 Hz and a lowpass filter set at 10 kHz. Segmental nerves innervating the anterior segments were used preferentially. Tactile stimulation was achieved by touching a silver wire connected to a micromanipulator to the posterior body wall of the larva.

Behavioral analysis:

Handling:

As described in Connolly and Tully (1998) and Simon et al. (2006), all experiments used naive flies and were performed at the same time of day, in a range of 3–4 hr in the afternoon, to avoid variation in performance linked to circadian rhythm. All behavioral assays were carried out in the same dedicated room at ∼25°. Unless otherwise noted in the text, flies were collected the day before the experiment, under cold anesthesia and using a mixture of males and females, and experiments were performed under ambient light. Individuals were counted and sexed under CO2 anesthesia after the experiments were performed. The flies were allowed to habituate to the testing room for 2 hr before each experiment.

Survival:

To compare the lethal effects of the dVMAT mutants vs. relevant deficiencies (see Figure 2C) three females and three males were mated in vials for 5 days at 25°. Since both the dVMAT mutants and the deficiencies were maintained over balancer (CyO or SM1), controls also included a balancer chromosome (see also Figure 2 legend). For all crosses, the number of adult flies per vial that eclosed were counted for 19 days after the crosses were initiated and scored for the dominant Cy marker; i.e., the number of straight vs. curly winged flies. The number of Cy heterozygotes (curly wings) were used to calculate the expected number of Cy+ (straight wings), assuming standard Mendelian ratios and that CyO/CyO, SM1/SM1, and CyO/SM1 are lethal. Statistical analysis was performed using the raw numbers of surviving flies. To facilitate comparisons between genotypes, we show the data as percentages of wild-type (wt) survival in Figure 2C.

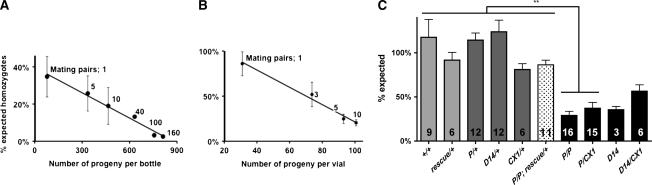

Figure 2.—

Homozygous flies are sensitive to crowding. (A) Conditional survival of dVMAT mutants in bottles. Data points represent the percentage of expected adult homozygotes from heterozygous parents (dVMATP1/CyO). Under standard laboratory conditions (≥100 females per bottle), <1% of dVMATP1 mutant homozygotes reach adulthood. In contrast, up to ∼40% of expected homozygotes are obtained in bottles containing 1 mating pair (one female crossed with one male). Each data point represents the mean ± SEM of n = 3 crosses made with indicated number of mating pairs for 5 days. Similar results were obtained using dVMATΔ14 homozygotes (not shown). (B) In vials, a similar effect is observed. Nearly all dVMATP1 (P/P) homozygotes can reach adulthood using 1 mating pair per vial (mean ± SEM, n = 18 crosses) and a decrease in homozygote survival is seen in vials containing increasing numbers of mating pairs (3, 5, or 10; n = 3 crosses for each). For all conditions, parents were removed after 5 days. (C) Deficiency analysis and genetic rescue. Columns represent the percentage of expected genotypes mating three females and three males in vials for 5 days. The number of replicates and the F1 genotypes that were scored for survival are indicated. Survival of +/+ homozygotes did not differ from flies expressing rescue transgenes in a dVMAT + background (da-GAL4, UAS-dVMAT-A indicated as “rescue/+”), or other controls under the top bar in C including dVMATP1/+ heterozygotes (indicated as “P/+”), dVMATΔ14/+ heterozygotes (D14/+), and the heterozygous deletion CX1/+. In contrast, P/P and CX1/P differed from the genetically rescued line dVMATP1; da-GAL4, UAS-dVMAT-A (indicated as “P/P; rescue/+”), (one-way ANOVA P < 0.0001, Dunnett's post-test, indicated on the graph, **P < 0.01, and all other controls **P < 0.01). The crosses used to generate the listed F1 genotypes were: “+/+”: CyO/+ × CyO/+ ; “rescue/+”: da-GAL4, UAS-DVMAT-A × CyO/+; “P/+”: dVMATP1/CyO × CyO/+ ; “D14/+”: dVMATΔ14/CyO × CyO/+; “CX1/+”: Df(2)CX1/SM1 × CyO/+; “P/P; rescue/+”: dVMATP1/CyO; da-GAL4, UAS-DVMAT-A × dVMATP1/CyO; +/+ ; “P/P”: dVMATP1/CyO × dVMATP1/CyO ; “P/CX1”: dVMATP1/CyO × Df(2)CX1/SM1 ; “D14”: dVMATΔ14/CyO × dVMATΔ14/CyO; “D14/CX1”: dVMATΔ14/CyO × Df(2)CX1/SM1.

Larval locomotion:

As adapted from Connolly and Tully (1998), one third instar larva was placed on a petri dish filled with standard food and allowed to acclimate for 1 min. The lid of the petri dish was covered with a 5 × 5 mm grid and the number of grid lines crossed by the larva recorded over a period of 5 min. Experiments were performed blindly with respect to genotype, and all larvae were allowed to reach adulthood, at which time the genotype was determined. Mutants were scored by the absence of the Cy marker on the CyO balancer. Homozygotes (dVMATP1/dVMATP1) were obtained from heterozygous balanced parents (dVMATP1/CyO) and heterozygous mutants (dVMATP1/+) from crosses of heterozygous balanced parents (dVMATP1/CyO) with controls (CS, “+/+”).

Response to touch in larvae:

Assays were performed as described in Kernan et al. (1994) and Connolly and Tully (1998). Briefly, third instar larvae were handled as for locomotion. After 1 min. of rest on the food, anterior segments were lightly stroked with an eyelash. Their response was measured on a scale of 0–4 as described (Kernan et al. 1994; Connolly and Tully 1998); the same larva was tested four times with a maximal possible score of 16. Controls (w1118CS10 and CS) performed similarly to previous reports (w1118CS10 9.5 ± 2.4, CS 11.1 ± 1.8 compared to yw 10.3 ± 0.24 in Kernan et al. (1994).

Negative geotaxis studies in adults:

Negative geotaxis behavior (Benzer 1967; Connolly and Tully 1998) was recorded as the percentage of flies able to climb on the upper tube of a choice-test apparatus in 15 sec (the time needed for ∼80% of 4-day-old wt flies to reach the upper tube), or 5 sec; the latter represents a challenging condition for control flies and only ∼15% of 4-day-old flies reached the upper tube. To stimulate the flies and initiate each experiment, the apparatus was tapped three times. Approximately 50 naive flies were used for each per data point.

Fast phototaxis and dark reactivity studies in adults:

Positive phototaxis was assessed in a countercurrent apparatus (Benzer 1967; Connolly and Tully 1998) as described (Connolly and Tully 1998; Romero-Calderón et al. 2007). For testing fast phototaxis toward the light, the flies were tapped gently to the bottom of the first tube, and the apparatus was laid horizontally with the distal tubes directly in front of a 15-W fluorescent warm-white light. The flies were given 15 sec to reach the distal tube (the time necessary for 100% of 3- to 4-day-old control flies to reach the first tube). After the test, the tubes were collected and the flies anesthetized and counted. Each fly received a score corresponding to the tube in which they were found at the end of the assay, and the performance index (PI) was calculated by averaging all of the scores and dividing by the total number of flies multiplied by the total number of tubes. A maximum value of 1 is obtained when all of the flies have chosen five times to go into the distal tube. Tests for movement away from light and dark reactivity were performed similarly, with a 15-sec choice, but with the proximal rather than the distal tube next to light in the first case, and in the second case without a visible light stimulus and under a dim photosafe red light, to which flies are blind. For each experiment, we used 30–100, naive, 3- to 5-day-old flies.

Open-field locomotion test in adults:

As described in Connolly and Tully (1998), in brief, a single fly was allowed to acclimate for 1 min in an 80 × 55 × 2-mm chamber containing a 5 × 5-mm grid. The number of grid lines that were crossed over a period of 1–2 min was scored in real time or from video recordings. As previously described (Chang et al. 2006), cocaine was administered in standard food: 3 ml of molten molasses agar media was mixed with 150 μl of a stock solution of cocaine in water to obtain a final concentration of 1 μg/ml. Red food dye (McCormick, Hunt Valley, Maryland) was added (0.4% v/v final) to ensure homogeneity. Control food was made in parallel, using vehicle alone. Fresh food was provided each day for 5–7 days prior to behavioral testing.

Longevity studies:

Survival was measured as described (Simon et al. 2003). Briefly, flies were collected 2–3 days after adult emergence, allowing time for mating. Males and females were then separated under brief cold anesthesia. The flies were then transferred every 2–3 days into vials containing fresh food at 25°, under a 12:12-hr light–dark cycle. Deaths were recorded at transfer.

Statistical analysis:

Most statistical analyses were performed using Prism 4 (GraphPad Software, San Diego).

RESULTS

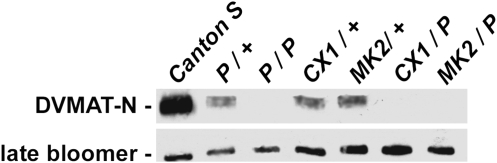

Decrease of DVMAT protein expression in the dVMAT mutant:

We have obtained a line [l(2)SHO459] (Oh et al. 2003) containing a transposable P element reported to localize to the Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project (BDGP) predicted gene CG6119 (now CG33528 http://flybase.bio.indiana.edu/reports/FBgn0259816.html), which we have found encodes the 3′ portion of dVMAT (Greer et al. 2005). We have confirmed that the insertion site of l(2)SHO459 is the last coding exon of dVMAT, which generates a functional deletion of the last two transmembrane domains of DVMAT-A (Romero-Calderón et al. 2008). We designate this line as dVMATP1. In addition, we have excised the P element in dVMATP1 to obtain an imprecise excision allele (dVMATΔ14), that contains a 57-bp in-frame insertion of P-element-derived DNA (Romero-Calderón et al. 2008). Western blots of adult head homogenates show a dramatic reduction in DVMAT protein in homozygous dVMATP1 (Figure 1, P/P) and dVMATΔ14 flies (not shown) as compared to CS controls (Figure 1). DVMAT protein levels are restored using the daughterless promoter (da-GAL4) and the UAS-dVMAT-A transgene (not shown). Similar to heterozygous mouse VMAT2 knockouts (Fon et al. 1997), we observe a dose-dependent decrease in expression in the heterozygous dVMATP1 mutant (Figure 1, P/+).

Figure 1.—

DVMAT protein levels. The expression of DVMAT protein in mutant heads was tested using an antibody raised against the N terminus of the protein, which detects both known splice variants dVMAT-A and -B. Compared to Canton-S controls, heterozygous dVMAT mutants (P/+) show a marked reduction in expression, similar to the heterozygous deficiencies CX1/+ and MK2/+. DVMAT protein was not detected in the homozygous dVMATP1 (P/P) mutant, dVMATP1/CX1, or dVMATP1/MK2. One fly head equivalent of protein was loaded in each lane. The membrane protein Late bloomer was used as a loading control.

The deficiencies Df(2R)CX1 and Df(2R)MK2, respectively, delete chromosomal regions 49C1 to 50D1 and 50A6 to 50C1–3. Thus, both should uncover the dVMAT locus (50A14-50B1, Greer et al. 2005). As for dVMATP1 homozygotes, no protein is detected in dVMATP1 over the deletions (Figure 1, CX1/P and MK2/P) confirming that the deficiencies uncover the dVMAT gene. In addition, heterozygotes for the chromosomal deletions (Figure 1, CX1/+ and MK2/+) express DVMAT at a level similar to the heterozygous dVMAT mutants (Figure 1, P/+). These data, and the absence of detectable protein in dVMATP1 homozygotes are consistent with the possibility that dVMATP1 is a null allele.

Conditional viability of the mutants:

The dVMATP1 mutation was first identified as an anonymous lethal gene on the second chromosome (Oh et al. 2003), and under standard culture conditions <1% of adult dVMATP1 or dVMATΔ14 flies survive (Figure 2A). However, we find that by reducing the density of the cultures, up to 40% of the homozygous dVMAT mutants eclose and survive into adulthood in bottles (Figure 2A), and up to 100% survive in vials (Figure 2B). Similarly, when individual embryos were plated separately in an attempt to stage lethality, all of the homozygous mutants survived (data not shown). Reduced survival as a result of culture density was not seen in heterozygous mutants (Figure 2C) or wild-type flies (not shown). To confirm that density-dependent lethality was due to mutation of the dVMAT gene, we showed that expression of the UAS-dVMAT-A transgene (Chang et al. 2006) rescued lethality in homozygous dVMATP1 mutants (Figure 2C). Heterozygous deletions (CX1/+ and MK2/+) and the deletions over dVMATP1 (CX1/P and MK2/P) showed rates of survival similar to the dVMATP1 homozygotes (Figure 2C), consistent with the notion that dVMATP1 is a null allele.

Despite decreased amine storage, dVMAT mutants survive for weeks, allowing a phenotypic analysis of behavior:

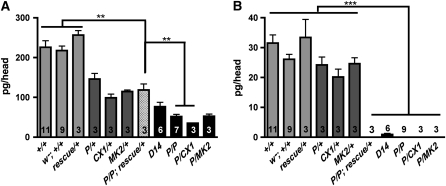

We next assessed how reduced dVMAT expression would affect monoamine stores in adult flies. We observe robust differences in amine levels in dVMAT mutants for both males and females (supplemental Figure 1) and we therefore pooled the data from both sexes as shown in Figure 3. In dVMATP1 heterozygotes, dopamine levels in adult heads are reduced by ∼35% compared to both CS and w1118CS10 controls, and in dVMATP1 homozygotes they are reduced ∼75% (Figure 3A). dVMATΔ14 homozygotes, which are phenotypically w, show an ∼65% reduction compared to controls. Residual dopamine content in the dVMAT mutants may be derived from cuticle forming tissue (see discussion). We could not detect serotonin in dVMATP1 homozygotes (Figure 3B). In contrast, we detect residual serotonin content in heads derived from dVMATΔ14 homozygotes (Figure 3B) suggesting that dVMATΔ14 is a weaker allele than dVMATP1.

Figure 3.—

Reduced dopamine and serotonin content. Monoamine levels were measured using HPLC. (A) Dopamine (pg/head): reduced dopamine content compared to the control lines CS (+/+) and w1118CS10 (w−; +/+) was seen in flies heterozygous for dVMATP1 (P/+), dVMATΔ14 (D14/+), and two genetic deletions CX1/+ and MK2/+. More severe reductions were seen in the homozygous mutants P/P and D14/D14, as well as in P/CX1 and P/MK2. The reduction in dopamine levels in P/P can be partially rescued by daughterless driving the expression of UAS-DVMAT-A cDNA (P/P; rescue/+). Significance values for the rescue line “P/P, rescue/+” compared to P/P or controls are indicated (one-way ANOVA P < 0.0001. Dunnett's post-test, **P < 0.01). (B) Serotonin (pg/head): serotonin levels are reduced in homozygous mutants and are not rescued by the expression of DVMAT-A cDNA using the da-GAL4 driver. (one-way ANOVA P < 0.0001, Bonferroni multiple comparison post-test separated two groups as indicated, ***P ≤ 0.001).

Since the w gene also has been reported recently to alter monoamine levels in the fly (Borycz et al. 2008; Sitaraman et al. 2008), and some of our experiments were performed in a w background, we compared the dopamine and serotonin contents of w1118CS10 vs. CS adult fly heads. Our data show no significant effect of w on either dopamine or serotonin levels and overall lower monoamine levels in CS heads as compared to both Sitaraman et al. (2008) and Borycz et al. (2008). For a discussion of variations in amine measurements in Drosophila see Hardie and Hirsh (2006).

Using the daughterless promoter (da-GAL4) to drive the UAS-DVMAT-A transgene we find that dopamine levels are partially rescued (up to heterozygote levels, Figure 3A). Since da-GAL4 is usually considered a ubiquitous driver in neurons, we were surprised to find that serotonin levels were not rescued using da-GAL4 (Figure 3B). To further investigate the discrepancy between dopamine and serotonin contents in the rescue lines, we explicitly tested the expression pattern of da-GAL4 using a UAS-GFP transgene as a marker, and colabeled with an antibody to serotonin. As expected, the expression pattern of da-GAL4 is quite broad; however, we did not detect any colabeling with serotonin (data not shown). Since expression of UAS-DVMAT-A using the daughterless driver fully rescues the lethality and infertility of dVMATP1 (Figures 2C and 4, D and E), exocytotic release of serotonin may not be essential for either survival or fertility (see discussion).

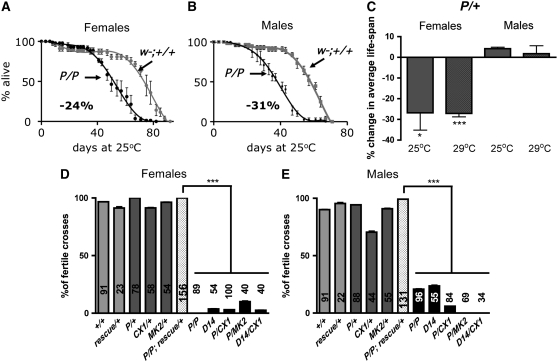

Figure 4.—

Homozygous mutant adults live up to 3 weeks, but have decreased fertility. (A–C) Decreased life span of the adult dVMATP1 mutant, compared to the control w1118CS10 (indicated as “w−; +/+”). (A and B) Survival curves of the dVMATP1 homozygotes (P/P) are shown (4–5 replicates of 20 flies at 25°). A similar decrease in average life span is seen in A homozygous females (−24%, 5 internal replicates of 20 flies, Wilcoxon-rank test comparing the survival curves P < 0.023), and in B homozygous males (−31%, Wilcoxon-rank test P < 0.017). (C) Female dVMATP1 heterozygotes show a decrease in life span when tested at either 25° (−27% ± 8, three independent experiments with three to four internal replicates of 20–40 flies, Student's t-test comparing average life span to controls, *P < 0.024) or 29° (−27% ± 2, two to three independent experiments with four internal replicates of 40 flies, Student's t-test, ***P < 0.0001) as compared to the control line. Male heterozygous mutants do not show a decrease in life span at either 25° or 29°. (D and E) Decreased fertility in homozygous dVMAT mutants and mutants over deficiency and rescue by UAS-dVMAT-A cDNA. For each cross, individual flies of the indicated genotype were mated with two to three CS control flies (+/+) of the opposite sex for 5 days. Columns indicate the percentage of individual crosses yielding adult progeny. The number of individual crosses made is indicated in each column. (D) Homozygote female mutants are infertile: homozygous dVMATP1 females mated to CS males did not yield any progeny in 89 testcrosses. A few vials with progeny were seen using dVMATΔ14 homozygotes (D14) and mutants over deficiency (P/CX1, P/MK2, and D14/CX1). Fertility of the genetically rescued females (P/P; rescue/+) differed from all the mutant lines (P/P, D14, P/CX1, P/MK2, D14/CX1, one-way ANOVA P < 0.0001, Bonferroni post-test as indicated on the graph, ***P < 0.001). The fertility of the rescue line did not differ from controls. (E) Male dVMAT homozygotes show reduced fertility, with only ∼20% of the crosses for P/P or D14/D14 males to CS females yielding progeny. The fertility of genetically rescued males (dVMATP1/dVMATP1; da-GAL4, UAS-DVMAT-A/+, indicated as “P/P; rescue/+”) is significantly higher than all of the mutant lines including P/P, D14, P/CX1, P/MK2, D14/CX1, (Bonferroni post-test, ***P < 0.001) but does not differ from either CS controls, dVMAT heterozygotes, heterozygous deficiencies (CX1/+ and MK2/+), or CS flies expressing the rescue transgenes (da-GAL4, UAS-DVMAT-A/+ indicated as “rescue/+”).

Despite deficits in amine storage, for up to 3 weeks posteclosion, the adult homozygous dVMAT mutants do not die at a faster rate than controls (w1118CS10, “w−; +/+”) (see materials and methods), and mutants can survive for >2 months (Figure 4, A and B). However, homozygous males, and both homozygous and heterozygous dVMATP1 females show a decrease in life span of ∼30% and begin dying 1 week before controls (Figure 4, A–C). In addition, both male and female mutants show fertility defects (Figure 4, D and E). Only a fraction of the adult homozygous males generate adult progeny when mated with CS females (21% ± 0.5 and 24% ± 1, respectively, for dVMATP1 and dVMATΔ14, Figure 4E). Homozygous dVMATP1 females are essentially infertile and did not appear to lay any eggs as virgins or after mating; however, a few adult progeny were produced by dVMATΔ14 females as well as heterozygotes of dVMATP1 over chromosomal deletions (Figure 4D).

Infertility is due to defects in both oocyte development and retention:

Since dVMATP1 is more likely to be a null (see discussion), we focused most of our subsequent studies on this allele. To facilitate our phenotypic analysis, we outcrossed dVMATP1 5 times into the well-characterized genetic background w1118CS10, which had been previously outcrossed 10 times to the wild-type strain Canton-S (Simon et al. 2003). The w gene has been previously reported to cause some behavioral deficits (Zhang and Odenwald 1995; Campbell and Nash 2001; Svetec et al. 2005; Sitaraman et al. 2008). We did not detect differences between the performance of CS vs. w1118CS10 for any of the assays used here except fast phototaxis and movement away from light (supplemental Figure 2); phototactic defects in w are presumably due to the absence of screening pigments in the eye.

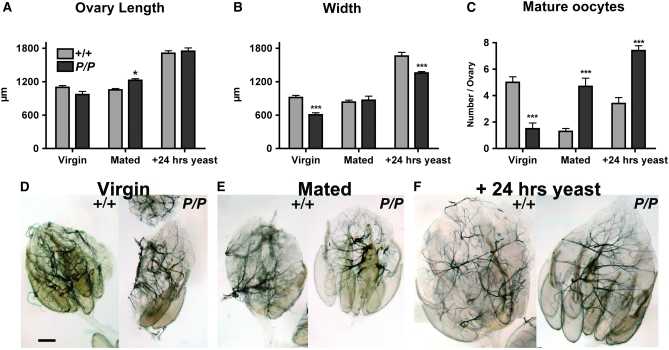

Infertility caused by altered aminergic signaling has been associated with egg retention and disrupted oocyte development (see discussion). Therefore, to investigate the mechanisms(s) underlying female infertility in dVMAT mutants, we dissected and examined the ovaries from mutant and control flies. We find that the ovaries of 3-day-old, mated homozygous dVMATP1 females contain 3.5-fold more mature oocytes than controls (4.7 ± 0.6 vs. 1.3 ± 0.2 in CS females, Figure 5, C and E). dVMAT mutant ovaries are similar in length and only slightly larger (+4%, P < 0.05) than CS controls despite their dramatic increase in oocyte content (Figure 5, A, B, and E). Thus, dVMAT mutants retain oocytes and/or eggs similar to mutants with defects in octopaminergic signaling (Monastirioti 1999; Lee et al. 2003; Cole et al. 2005) but also show a relative decrease in ovary size.

Figure 5.—

Abnormal ovarian morphology. (A–C) The bar graph shows the length (A), maximal width (B), and number of mature oocytes (C) in CS controls (“+/+”, light gray bars) and homozygous dVMATP1 females (“P/P”, dark gray bars). Each bar represents the mean ± SEM from 10 ovaries. For ovary length, the mutant differed from control only as a function of genotype × condition (two-way ANOVA P < 0.0001, Bonferroni post-test *P < 0.05.). For ovary width and number of mature oocytes, both genotype and condition alone (and genotype × condition) showed significant differences for mutant vs. control (one-way ANOVA, P < 0.0001 for both). The significance levels (Bonferroni post-test) for differences between mutant and control within each condition (virgin, mated and +24 hr yeast paste) are indicated on the graphs (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). (D–F). Representative examples of ovaries derived from 3- to 4-day-old mutant and control virgins (D), mated females (E), and 4-day-old mated females fed yeast paste for 24 hr (F) are shown. Bar, 200 μm.

To further investigate these effects, we examined ovaries dissected from 3-day-old virgin females. Unlike mated females, wild-type virgin females retain mature oocytes in their ovaries (Bloch Qazi et al. 2003), and we observe multiple mature oocytes in ovaries dissected from control flies (Figure 5, C and D). However, in contrast to mated dVMAT mutants, mutant virgins showed fewer mature oocytes than controls (1.5 mature oocytes per ovary vs. 5 in control virgin flies, Figure 5C) and a modest decrease in ovary size (−33% in width, Figure 5B).

The difference between mature oocyte numbers in mated vs. virgin dVMAT mutants suggests that mutant females are able to respond to mating signals known to increase mature oocyte production. We therefore investigated whether the mutants were also able to respond to another stimulus known to influence oocyte development—nutrition (Drummond-Barbosa and Spradling 2001). Similar to wild-type flies, dVMAT mutant females show a twofold increase in the number of mature oocytes (P < 0.0001) and an increase in ovary size, (albeit less than controls) when fed yeast paste for 24 hr (Figure 5, A–C, and F). These data confirm that dVMAT mutants are able to respond to signals that stimulate the function of the ovary, but are defective in oocyte and egg deposition. In addition, unlike mutants that reduce octopaminergic signaling (Monastirioti 1999; Lee et al. 2003; Cole et al. 2005), they show an additional defect in oocyte development that is most easily observed in virgin females. This difference is consistent with previous pharmacologic data suggesting that dopaminergic and possibly serotonergic inputs regulate oocyte development (Neckameyer 1996; Pendleton et al. 1996; Willard et al. 2006) (see discussion).

The larval phenotype of dVMAT mutants includes decreased locomotion and motoneuron activity:

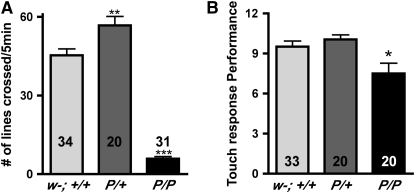

Under relatively sparse culture conditions, most if not all homozygous dVMATP1 (P/P) mutant larvae can survive through the third instar and pupate. However, larval behavior is grossly abnormal. Although dVMAT mutants clearly feed, as shown by uptake of food coloring in the culture media (data not shown), they show reduced movement compared to wild-type (w11118CS10, Figure 6A, w−; +/+) and heterozygote controls (Figure 6A, P/+, one-way ANOVA P < 0.0001, Bonferroni post-test P < 0.001 compared to w−; +/+ or P/+). In contrast to homozygotes, the heterozygous dVMATP1 mutant (P/+) displays an increase in locomotion (see also adult locomotion below). Interestingly, homozygous dVMATP1 (P/P) larvae will initiate locomotion if stimulated by contact with another larva (not shown) or the bristle of a paintbrush. Quantitation of their response to touch shows only a slight deficit relative to controls (Figure 6B). Heterozygotes (P/+) are indistinguishable from controls in their response to touch (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.—

Mutants show reduced larval locomotion but near normal response to touch. (A) Locomotion: number of grids crossed within 5 min. Both homozygotes (P/P) and heterozygotes (P/+) differ from controls (one-way ANOVA, P < 0.0001). Significance levels (Bonferroni post-test) for differences between homozygous and heterozygous mutants vs. control (w−; +/+) are indicated (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). (B) Response to touch: the performance of the heterozygotes is not different from that of control (w−; +/+), and the homozygotes are somewhat less responsive (one-way ANOVA: P < 0.0032, Bonferroni post-test w−; +/+ vs. P/P indicated on the graph, *P < 0.05).

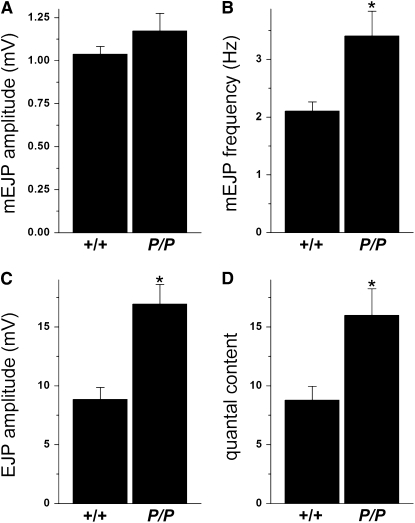

To further explore the mechanisms underlying the defect in dVMAT larval locomotion, we performed an electrophysiological analysis of the glutamatergic (type I) NMJ, the synapse that drives muscle contraction and larval locomotion (Jan and Jan 1976; Gramates and Budnik 1999). We observed a doubling of the evoked junctional potentials (EJPs) in dVMATP1 homozygous mutants (P/P) relative to controls (Figure 7C, 9 ± 1 mV in CS controls “+/+” vs. 17 ± 2 mV in P/P mutants, n = 17 and 12, respectively; Student's t-test P < 0.0002). The amplitude of the miniature end plate potentials (minis) was similar to controls (Figure 7A, CS: 1.04 ± 0.04 mV, n = 17, vs. dVMATP1: 1.17 ± 0.10 mV, n = 12). However, the input resistance of the mutant muscle was higher than controls (see materials and methods), suggesting that muscle size may be smaller in the mutant. We therefore calculated quantal content (direct method: EJP/mEJP), which cancels out any effects of input resistance and represents the number of vesicles that fuse during evoked release. This too, was increased in the dVMAT mutant (Figure 7D), consistent with a presynaptic increase in synaptic strength. We also observed an increased frequency of spontaneous events (Figure 7B, CS: 2.1 ± 0.2 Hz, n = 17 vs. dVMATP1: 3.4 ± 0.4 Hz, n = 17, P < 0.005), consistent with a potentiation in presynaptic function.

Figure 7.—

Evoked release and quantal content are increased in dVMAT mutants. Comparison of homozygous dVMATP1 (P/P) mutants with controls CS (+/+). (A) The amplitude of spontaneous miniature events (mEJPs or minis) in mutant dVMATP1 homozygotes (P/P) does not differ significantly from CS controls (+/+, Student's t-test, P > 0.18). (B) Mini frequency is increased in P/P compared to controls (P < 0.005). (C) Evoked EJP amplitude is increased in P/P (P < 0.0002). (D) Quantal content calculated by the direct method is increased in P/P (P < 0.005). All data are shown as mean ± SEM, n = 17 for +/+, n = 12 for P/P.

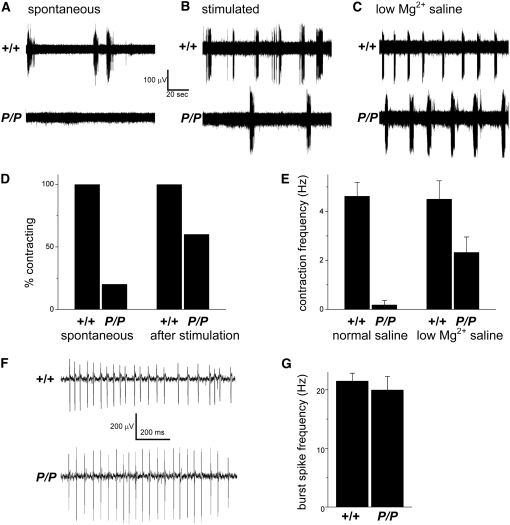

An increase in synaptic strength would not explain the locomotion defects in the dVMAT mutant, suggesting instead that the circuit is disrupted upstream of the larval NMJ. To test this hypothesis, we used a suction electrode attached to a segmental nerve to record motoneuron action potentials. In control larvae, spontaneous bursts of action potentials can be recorded from the segmental nerves (Figure 8); these coincide with the contraction of muscles in the innervated segment of the body wall (not shown). dVMATP1 mutant larvae show very few spontaneous action potentials or contractions (Figure 8, A, D, and E). However, the defects in initiating spontaneous action potentials and contractions can be partially overcome by mechanically stimulating the larvae (Figure 8, B and D), which is consistent with the results of larval locomotion assays. In addition to mechanical stimulation, increasing synaptic transmission throughout the nervous system by recording in saline with a lower Mg2+ concentration partially rescues the defects in both spontaneous action potential bursts and muscle contractions in the dVMATP1 mutants (Figure 8, C and E). Furthermore, the action potentials that we observe in dVMATP1 mutants appear essentially indistinguishable from wild-type bursts (Figure 8F) both in duration (data not shown) and spike frequency during a burst episode (Figure 8G). Together, these data suggest that the intrinsic properties of the motoneurons are not compromised and that the motor program that controls the pattern of activation, the central pattern generator (CPG), is grossly intact (see discussion and Saraswati et al. 2004). Rather, the decrease in baseline motoneuron activity is more likely to be due to deficits in the initiation of the CPG. We further speculate that the observed increase in EJPs may be a homeostatic response to the decrease in spontaneous motoneuron firing (see discussion).

Figure 8.—

Recordings from segmental nerves show a decrease in spontaneous action potentials. Data were derived from homozygous dVMATP1 (P/P) mutants and CS controls (+/+). (A) Sample traces from +/+ and P/P segmental nerves. No action potential bursts associated with a segmental contraction are seen in the mutant. (B) Sample bursts of action potentials recorded after tactile stimulation of the posterior cuticle show an increase in action potentials in the mutant. (C) Incubation in low Mg2+ saline also increases spontaneous contractions and associated action potentials in the mutant. (D) All control larvae that were tested (n = 6) but only one of five P/P larvae showed spontaneous contractions. Sensory stimulation (“after stimulation”) induced all CS and three out of five P/P larvae to contract. (E) Quantitation of the results shown in A and C shows low rates of contractions/action potentials in the mutant (0.2 ± 0.2 min−1, n = 5) relative to CS controls (4.6 ± 0.6 min−1, n = 6, Student's t, P = 0.00007). Incubation in low Mg2+ saline partially rescues the spontaneous contraction frequency of the mutant (2.3 ± 0.6, n = 9, compared to CS, 4.5 ± 0.8 min−1, n = 3). (F) Expanding the timescale of a representative trace shows that the action potential bursts that accompany segmental contraction are similar in the P/P mutant and +/+ controls. (G) Quantitation of the results from F shows that the frequency of action potentials during a burst episode [“burst spike frequency (Hz)”] is indistinguishable in P/P (20 ± 2 Hz, n = 22 bursts) vs. +/+ larvae (21 ± 1 Hz, n = 18 bursts, P > 0.5), indicating that the intrinsic physiology of motoneuron firing is intact in the mutant.

The adult homozygous dVMAT phenotype includes a blunted response to cocaine and a stronger attraction to light:

We next assessed the performance of the dVMATP1 mutant adults in a series of behaviors previously associated with aminergic signaling (Hevers and Hardie 1995; McClung and Hirsh 1998, 1999; Torres and Horowitz 1998; Chen et al. 1999; Bainton et al. 2000). Because of the conditional survival of homozygous dVMATP1 null mutants, we were able to test the behavior of flies presumably unable to release serotonin, dopamine, or octopamine from secretory vesicles either during development or in adulthood. The behavior of these animals reflects both the inability to use aminergic pathways as adults, as well as developmental adaptations to chronically absent amine release. For comparison, we tested the behavior of dVMATP1 heterozygotes. This allowed us to assess the potential effects of decreasing rather than eliminating DVMAT expression and regulated monoamine release.

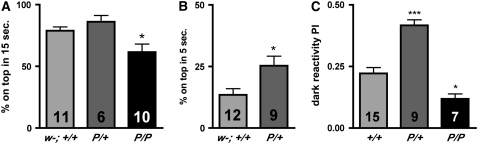

We first tested the escape response of mutants and controls using negative geotaxis (Connolly and Tully 1998), a well-described assay in which the flies are induced to escape their initial position by a mechanical stimulus. In response to the stimulus, wild-type flies will climb upward and against gravity (Connolly and Tully 1998). This assay has been used to test the performance of a variety of mutants and is notably sensitive to changes in dopaminergic signaling (Bainton et al. 2000; Sang et al. 2007). We first tested geotaxis under conditions in which most of the controls (w1118CS10: w−; +/+) were able to climb to an upper vial: 77% ± 4 of the control flies are able to reach the top vial in 15 sec (Figure 9A). We observed a modest decrease in the number (62% ± 6.5) of homozygous dVMATP1 (P/P) mutants that reached the upper vial (one-way ANOVA P < 0.0001, Bonferroni post-test P < 0.05). In addition, we observed a trend for more heterozygotes than controls to reach the upper vial, suggesting the possibility that the escape response might be potentiated in heterozygotes. To determine whether more challenging conditions would differentiate heterozygotes from controls, we performed the same assay, but reduced the time allowed to reach the upper vial. Given 5 sec to climb, 13.5% ± 2.5 of the control flies reached the upper vial. In contrast, 25% ± 4 of the heterozygous mutants reached the upper vial (t-test, P < 0.016, Figure 9B). These data indicate that a moderate decrease in dVMAT expression potentiates the escape behavior. Possible mechanisms for the increase in performance include an increase in: (1) locomotor speed, (2) the drive to climb upward against gravity, or (3) the escape response itself.

Figure 9.—

Heterozygotes show a potentiated escape response. (A and B) Negative geotaxis. (A) Given 15 sec to climb, dVMATP1 mutants (P/P) show a modest reduction in performance compared to both w−; +/+ and P/+ (one-way ANOVA, P < 0.0001, Bonferroni post-test *P < 0.05, n = 6–11 as indicated in each column, 30–80 flies per trial). (B) Given 5 sec to reach the top vial, P/+ performs better than control (t-test P < 0.0162). (C) Dark reactivity. Flies are mechanically agitated (in the absence of light or geotactic stimuli) and allowed to “escape” their home vial. The performance of both homozygotes and heterozygote differs from the control, (one-way ANOVA, P < 0.0001, Bonferroni post-test *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, using replicates of 30–80 flies with the number of replicates indicated in each column). Note: Since CS and w1118CS10 did not differ in performance (see supplemental Figure 2) only one was used as a control in each of the experiments shown here.

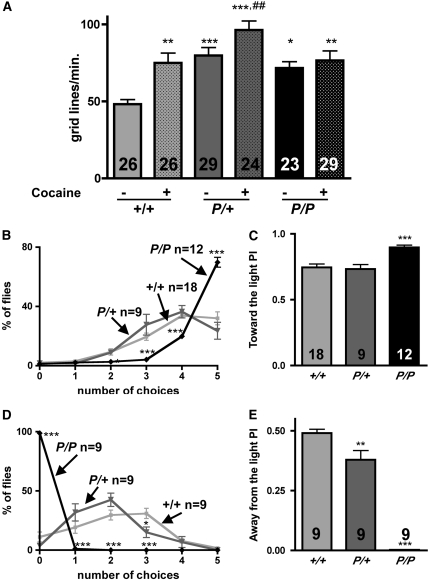

To help distinguish between the latter two possibilities, we used a second test of the escape response, in which the flies are induced to escape their initial position using a horizontally rather than vertically oriented apparatus (also known as dark reactivity; Connolly and Tully 1998). As observed for negative geotaxis, the dVMAT heterozygotes perform better than controls (Figure 9C). Together, the results of these assays suggest that the improved performance of the heterozygotes is not due to an increased drive to climb, but rather to an increase in either locomotion or the escape response. We find that both homozygotes and heterozygotes locomote faster than controls in an open field assay: both cross ∼60% more grid lines per minute than controls (CS and w1118CS10 did not differ and only CS “+/+” shown in Figure 10A). Since both genotypes locomote faster, but only the heterozygotes show an enhanced escape response relative to controls, our data suggest that the escape response per se is potentiated in heterozygotes.

Figure 10.—

Mutants show an increase in locomotion and fast phototaxis and a blunted behavioral response to cocaine. (A) Increased locomotion and a blunted response to cocaine. Homozygous (P/P) and heterozygous (P/+) mutants show an increase in locomotion relative to CS (+/+) controls, at baseline (“− cocaine”), with locomotion quantitated as the number of grid lines crossed per minute in an “open field” chamber. The locomotor activity of wild-type (wt) flies fed cocaine (“+/+: + cocaine”) is similar to the baseline rates of P/+ and P/P. When fed cocaine, P/+ but not P/P exhibits a significant behavioral response (one-way ANOVA, P < 0.01, Bonferroni post-test: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001: different from “+/+ − cocaine”; ##P <0.01: different from “P/+ − cocaine”). Twenty-three to 29 adults were tested per genotype, with number of replicates indicated in each column. (B) Fast phototaxis: toward the light. dVMATP1 mutants (P/P, black line) chose to go toward the light more often than CS (+/+, light shaded line), or dVMATP1/+ heterozygotes (P/+, dark shaded line) (two-way ANOVA, choice × genotype P < 0.0001, Bonferroni post-test, P/P but not P/+ differed from CS, ***P < 0.0001 at each indicated point). Number of replicates are indicated at the top of each curve. (C) The data in B are plotted as performance index (PI). P/P differs from both +/+ and P/+ (one-way ANOVA, P < 0.0001, Bonferroni post-test, difference with CS ***P < 0.001 as indicated). (D) dVMATP1 mutants choose to stay near light. The number of times flies chose to move away from a light source is plotted. The plot for P/P (black line) differs from both +/+ and P/+ (two-way ANOVA, P < 0.0001, Bonferroni post-test, significance level for each point as compared to CS as indicated, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001). (E) The data in D are shown as a performance index: both P/P and P/+ differ from +/+ (one-way ANOVA, P < 0.0001, Bonferroni post-test, difference with CS is indicated, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). The number of replicates is shown in each column.

To further assess potential changes in behavior due to altered amine release, we used locomotion to measure the flies' behavioral response to cocaine. We used a long-term exposure paradigm in which flies were fed a moderate dose of cocaine-HCl (1 μg/ml mixed into standard molten fly food) for 5 days (Chang et al. 2006). Controls showed an increase in locomotion when fed cocaine (+56%, Figure 10A), consistent with the previously described ability of cocaine to stimulate motor behavior in the fly (McClung and Hirsh 1998; Torres and Horowitz 1998; Bainton et al. 2000; Chang et al. 2006). Heterozygous dVMAT mutants fed cocaine showed a ∼20% increase in locomotion relative to untreated flies. In contrast, cocaine did not appear to alter the motor behavior of the homozygous mutants (see discussion).

Vision may also be regulated by monoamines (Hevers and Hardie 1995; Chen et al. 1999), and we next tested the performance of the dVMAT mutants using a fast phototaxis assay. We first measured attraction to light in a countercurrent apparatus in which the flies are allowed to choose to run toward light up to five times (Figure 10B). On average, both control and dVMAT heterozygotes chose to run toward the light four times, whereas the homozygotes ran to light five times. The performance of males and females did not differ (supplemental Figure 2), and the data were therefore pooled. The calculated performance index (see materials and methods) showed no difference between control and heterozygotes (0.73 ± 0.03 vs. 0.75 ± 0.03), and a 20% increase in the PI for homozygotes' movement toward the light (Figure 10C, 0.9 ± 0.02, one-way ANOVA: P < 0.0001).

Although the increase in fast phototaxis by the dVMAT mutant was statistically significant, the absolute difference from wild type was relatively small. More importantly, the apparent increase in phototaxis under these conditions might be artifactually enhanced by an increase in locomotor speed (see Figure 10A). To rule out this possibility, we tested the behavioral response of flies allowed to run away from the same light stimulus. In this assay, the homozygotes never ran away from the light. In contrast, the heterozygotes ran away from the light two times on average, and the control two to three times (Figure 10D). This effect is not the result of impaired locomotion since the same mechanical stimulus causes the flies to leave the proximal tube in the dark (see Figure 9, C and D). Thus, in the “away from light” phototaxis assay, the performance index of the homozygote is essentially 0 (0.002 ± 0.001), and the heterozygotes are 22% less efficient than the controls (0.38 ± 0.4 vs. 0.49 ± 0.02, one-way ANOVA, P < 0.0001, Figure 10E). In sum, we observe a dosage effect with homozygotes showing a more robust attraction to light than controls and heterozygous mutants showing a modest increase in phototaxis (Figure 10, B–E).

Both central and peripheral pathways might contribute to this effect. To test whether peripheral phototransduction in the eye and signaling by the photoreceptor cells were altered by loss of dVMAT we performed electroretinograms on the mutant flies. This electrophysiological assay measures field potentials in the retina and the first optic ganglia in response to light (Alawi and Pak 1971; Heisenberg 1971). We did not detect any difference between control and dVMAT null mutants (not shown). These data suggest that the increase in fast phototaxis seen in the dVMAT mutants more likely reflects differences in the animal's behavioral response to light, rather than differences in the perception of light by the eye.

DISCUSSION

We report here the phenotypic analysis of two Drosophila VMAT mutant alleles. In general, the phenotype of the dVMATP1 allele was somewhat stronger than dVMATΔ14 and appeared similar if not identical to heterozygotes containing dVMATP1 over two large chromosomal deletions. We conclude that dVMATΔ14 is a strong hypomorph, and that dVMATP1 is likely to be a null allele. This would be consistent with the characteristics of each allele at the molecular level. The dVMATP1 allele contains a P -element insertion in a coding exon and should result in a C-terminal truncation (Romero-Calderón et al. 2008). The excision event that generated the dVMATΔ14 allele left an insertion of 57 bp in the same reading frame as dVMAT; if translated, the protein would contain a 17-amino-acid insertion (Romero-Calderón et al. 2008). These differences notwithstanding, the phenotypes of the dVMATP1 and dVMATΔ14 are similar and in the remainder of the discussion we refer simply to the “dVMAT mutants.”

The phenotypes of the heterozygous and homozygous dVMAT mutants, respectively, demonstrate the synaptic and behavioral effects of chronically reduced vs. absent vesicular monoamine release. Remarkably, we find that homozygous mutants with little or no neuronal amine release not only survive, but show near normal or elevated responses to some environmental stimuli. This phenotype is in striking contrast to the enervating, and in some cases lethal effects of acute DVMAT inhibition with reserpine (Pendleton et al. 1996, 2000; Chang et al. 2006), suggesting that the survival and behavior of the dVMAT mutants is the result of multiple adaptive changes in the nervous system.

Monoamine content:

To our knowledge, dVMAT is the only vesicular transporter expressed in dopaminergic, serotonergic, and octopaminergic neurons in the fly (Greer et al. 2005; Chang et al. 2006), and HPLC analysis of adult head homogenates shows that dVMAT homozygous mutants store dramatically reduced quantities of dopamine and serotonin. (Octopamine concentrations could not be determined under the analysis conditions used here). The observed decrease in amine storage is consistent with previous studies of mouse VMAT2 knockouts (Fon et al. 1997) and C. elegans cat-1 mutants (Duerr et al. 1999). The residual dopamine present in total head homogenates derived from homozygous mutants is likely to represent cuticular dopamine (Wright 1987), which may constitute up to ∼75% of the total head content (Hardie and Hirsh 2006). In contrast, the brain is estimated to contain ∼96% of total head serotonin (Hardie and Hirsh 2006).

It has been reported that w can affect both amine levels and amine-dependent behavior (Zhang and Odenwald 1995; Campbell and Nash 2001; Svetec et al. 2005; Borycz et al. 2008; Sitaraman et al. 2008). Our HPLC measurements do not show significant differences in serotonin and dopamine between w and w+ flies. With the exception of phototaxis and movement away from light, we also do not detect behavioral differences for any of the assays we employed. These data indicate that mutations in dVMAT rather than w are responsible for all aspects of the phenotype we report.

Conditional lethality:

Survival of the dVMAT homozygotes depends on lowering the density of the cultures (see Figure 2). The effect of crowding makes it difficult to precisely stage lethality using standard quantitative methods that rely on plating individual embryos (data not shown), but qualitative observations strongly suggest that the mutants die as larvae. Further experiments will be required to determine how culture conditions may affect dVMAT mutant larvae. Regardless of the precise mechanism, it is likely that their sensitivity to crowding as well as other aspects of the dVMAT phenotype are primarily due to dysfunction of the nervous system, rather than reduced amines elsewhere in the organism. Dopamine is critical to cuticle formation (Wright 1987; Neckameyer and White 1993) but dVMAT is not expressed in the cuticle (Greer et al. 2005), and we do not detect cuticular defects in either the dVMAT mutants or flies overexpressing DVMAT-A (Chang et al. 2006; Sang et al. 2007).

The few adult dVMAT mutants that eclose under relatively crowded culture conditions are often smaller than wild-type flies, sluggish, and appear to be “escapers” of larval lethality: adult mutants that survive but are severely compromised. In contrast, mutants that develop under sparse conditions are of normal size, show survival rates of up to 100%, and perform better than controls in some assays. We suggest that these are not escapers and that it is more useful to conceptualize the dVMAT phenotype as conditionally lethal and dependent on a gene × environment interaction that we do not yet understand. For now, it is important to note that only flies raised under sparse conditions were used in all of the behavioral assays we report here.

Fertility:

Mutations in either of the biosynthetic enzymes for octopamine, tyramine β-hydroxylase (TβH), and tyrosine decarboxylase (Tdc2), or the octopamine receptor (OAMB) result in egg retention without defects in oocyte development, most likely secondary to altered ovarian and oviduct contractions (Monastirioti et al. 1996; Lee et al. 2003; Monastirioti 2003; Cole et al. 2005; Middleton et al. 2006; Rodríguez-Valentín et al. 2006). Octopamine may also act as a neurohormone in controlling the metabolism of gonadotropins (juvenile hormone and 20-H ecdysone; Gruntenko et al. 2007). dVMAT mutants show an egg-retention phenotype similar to mutants with reduced octopamineric signaling. However, they also show reduced ovary size supporting previous pharmacologic data that suggest a role for dopamine and/or serotonin in ovarian development (Monastirioti et al. 1996; Neckameyer 1996; Pendleton et al. 1996; Willard et al. 2006).

Reduced fertility in dVMAT males may also be due to loss of dopaminergic and/or serotonergic signaling. Tyrosine hydroxylase has been reported to be expressed in adult male testicular tissue (Neckameyer 1996) and serotonergic neurons innervate the male gonads (Lee et al. 2001). Since our data show that da-GAL4 rescues male as well as female infertility, and does not drive expression in serotonergic cells (see below), it is less likely that serotonin is responsible for either the male or female fertility defects in dVMAT mutants. Further experiments using cell-specific drivers to rescue dVMAT in particular aminergic cell types will allow us to genetically dissect the contribution of dopamine and other amines to both male and female fertility.

Despite the observed defect in female fertility, dVMAT mutant females appear to respond to signals in the sperm and seminal fluid that stimulate oogenesis (Bloch Qazi et al. 2003) and nutritional supplementation with yeast, which increases germ-cell proliferation (Drummond-Barbosa and Spradling 2001; Bloch Qazi et al. 2003). These data suggest that either monoamine neurotransmitters are not required for transmitting these signals or the circuits controlling these processes are more malleable than oogenesis and better able to adapt to the loss of aminergic signaling.

Serotonin does not seem to be necessary for survival and fertility:

We find that da-GAL4 expression is not detectable in serotonergic neurons and does not rescue the decrease in 5HT levels seen in the dVMAT mutant. The genetic rescue of dVMAT mutants using this driver therefore suggests the possibility that serotonergic neurotransmission might not be required for either development or survival. A large deletion that includes a serotonin receptor gene is embryonic lethal, and the analysis of an additional point mutant suggests that serotonin is required for gastrulation (Colas et al. 1999; Schaerlinger et al. 2007). Similarly, pharmacological experiments indicate a role for serotonin in oogenesis (Willard et al. 2006). In light of these studies, we speculate that a developmental adaptation to decreased serotonin release might reduce its apparent requirement in the dVMAT mutants.

Central amines control locomotion and glutamate release at the larval NMJ:

The larval NMJ in Drosophila is a well-characterized electrophysiological preparation and, like many central synapses in mammals, uses glutamate as the primary neurotransmitter (Jan and Jan 1976; Petersen et al. 1997; Daniels et al. 2006). Furthermore, both the electrophysiological and locomotor outputs of the NMJ are modulated by monoamines (Nishikawa and Kidokoro 1999; Saraswati et al. 2004; Fox et al. 2006), although the aminergic circuits responsible for these effects are not known.

We show that mutation of dVMAT leads to defects in: (1) locomotion, (2) glutamate release at the NMJ, and (3) the baseline electrical activity of segmental nerves containing motoneuron axons. Under conditions of low Mg2+ in which synaptic transmission throughout the nervous system is potentiated, baseline motoneuron activity in the dVMATP1 mutant is restored and appears more similar to controls. Touching the body wall of the dissected larva also increases motoneuron activity. Similarly, when the larvae are stimulated to move, crawling appears to be grossly normal. These data suggest that both the basic electrophysiological function of the motoneuron as well as the intrinsic motor program regulating motoneuron output—the CPG—are grossly intact. Therefore, the deficits we observe in both locomotion and motoneuron activity suggest that aminergic inputs may be required to initiate the activity of the CPG under baseline conditions. This idea is consistent with the phenotype shown by mutants in the gene encoding tyramine-β-hydroxylase (TβH) required for the biosynthesis of both tyramine and octopamine (Saraswati et al. 2004; Fox et al. 2006). Since light touch can activate motoneuron activity and locomotion in the dVMAT mutants, it would appear that, in some cases, aminergic regulation can be circumvented by the activation of other circuits that control the CPG.

Previous studies (Saraswati et al. 2004; Fox et al. 2006) and our own data suggest that, for larval locomotion, the primary site of action for amines is upstream of the motoneuron. Amines may activate the motoneuron in the neuropil of the ventral nerve cord or alternatively, influence synaptic events even farther upstream. Since these are most likely to be central effects, the phenotype we observe seems unlikely to involve more peripheral type II terminals that store octopamine and reside on selected muscles near type I terminals (Monastirioti et al. 1995; Gramates and Budnik 1999). Several classical electrophysiological studies have tested the affects of octopamine on the glutamatergic NMJ in flies and other insects, but the true function of type II terminals remains unclear (Klaassen and Kammer 1985; Nishikawa and Kidokoro 1999).

In addition to defects in segmental nerve activity we observe a robust increase in quantal content at the NMJ, as shown by an increase in the ratio of evoked potentials/miniature evoked potentials. This result may seem counterintuitive, since glutamate release at the NMJ drives locomotion, and we observe a decrease in movement. We propose that the increase in quantal content is likely to represent an adaptive response to decreased activity in the motoneuron. Additional data (not shown), suggest that the size and morphology of the NMJ in dVMAT mutant larvae and the number of boutons on each muscle are similar to wild type. Therefore, the increase in quantal content that we observe is not likely to represent an increase in the number of release sites, but rather, that a larger number of vesicles are released from each bouton during exocytosis.

In mammals, the aminergic regulation of glutamatergic signaling has been suggested to regulate downstream behavior and thus contribute to the pathophysiology of both addiction and schizophrenia (Nicola et al. 2000; Carlsson 2006; Hyman et al. 2006; Lewis and Gonzalez-Burgos 2006). However, in mammalian preparations, the glutamatergic synapses under study are far removed from the final behavioral output, making a direct comparison between synaptic function and behavior difficult. In contrast, the behavioral output of the fly NMJ, locomotion, is directly mediated by an electrophysiologically accessible synapse. Our data and those of others (Cooper and Neckameyer 1999; Dasari and Cooper 2004; Saraswati et al. 2004; Fox et al. 2006) support the possibility that the larval NMJ may provide a simple and robust system to study how amines modulate glutamatergic signaling and its downstream affects and the adaptive changes that occur in response to altered aminergic transmission.

Adult mutants outperform wild-type flies in some behavioral assays:

Homozygous VMAT2 knockout mice die soon after birth thus prohibiting a behavioral analysis of adults completely lacking regulated amine release (Fon et al. 1997; Takahashi et al. 1997; Wang et al. 1997). In contrast, null dVMAT homozygotes can eclose and survive for up to 3 weeks, thereby allowing us to test the behavior of both homozygous and heterozygous mutants. In contrast to treatment with reserpine, which decreases motor activity (Pendleton et al. 2000; Chang et al. 2006), dVMAT mutant homozygotes show an increase in open-field locomotion. This difference further suggests that development in the absence of amines may result in adaptive changes in the fly's nervous system. Adaptive changes may also cause the increase in phototaxis seen in homozygotes and the increase in the escape response seen in heterozygotes. In contrast, other aspects of the dVMAT phenotype are likely to be due simply to decreased amine release, rather than a subsequent adaptive change in response to decreased release. For example, the absence of a behavioral response to cocaine in dVMAT homozygotes may result from limited dopamine stores; in the absence of extracellular dopamine, blockade of DAT (or SERT) would not increase extracellular dopamine levels and thus should not be able to potentiate signaling at the synapse.

How might the dVMAT mutants adapt to decreased vesicular amine release? As suggested previously for VMAT2 knockout heterozygotes, decreased gene dosage in the fly might decrease amine release and thus lead to synaptic and behavioral hypersensitivity via increased sensitivity of postsynaptic receptors (Fon et al. 1997; Takahashi et al. 1997; Wang et al. 1997; Fukui et al. 2007). This might be the cause of the heightened escape response in the dVMAT mutant heterozygotes. The survival and behavior of the dVMAT homozygotes is more difficult to understand. One possible mechanism is that monoamines are still synthesized, albeit not stored, or not stable, thus not detectable, and that mutants are using other, nonexocytotic forms of amine release. This could conceivably occur via efflux through the plasma membrane transporters DAT or SERT, although there is relatively little evidence for efflux in the absence of psychostimulant drugs such as amphetamine (Heeringa and Abercrombie 1995; Falkenburger et al. 2001; Hilber et al. 2005; Johnson et al. 2005; Kahlig et al. 2005). Alternatively, some circuits usually controlled by amines may have adapted by dramatically downregulating the relevant signaling machinery, such that aminergic input is no longer required. Both possibilities are intriguing and we speculate that the study of compensatory changes in dVMAT mutants may be applicable to adaptive processes in other systems. Cellular adaptations to altered aminergic neurotransmission are thought to account for the long-term response to antidepressants (Pittenger and Duman 2008) and the behavioral changes that accompany psychostimulant addiction (Kopnisky and Hyman 2002; Wolf et al. 2003; Girault and Greengard 2004); however, the mechanisms underlying these changes remain unclear. Similar to dVMAT homozygotes, cellular adaptations that occur during psychostimulant addiction may bypass the normal aminergic regulation of reward circuits (Hyman et al. 2006). We suggest that dVMAT mutants will provide a useful model to explore the potentially conserved mechanisms by which the nervous system adapts to changes in aminergic signaling.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a 2007 Young Investigator Award from National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression (NARSAD); a pilot grant award from the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) Center for Autism Research and Treatment with funding by a National Institutes of Health grant (STAART, U54 MH068172, PI: M. Sigman and D. Geschwind); training support from the UCLA Cousins Center at the Semel Institute for Neurosciences with funding by a National Institutes of Health Grant (T32-MH18399) to A.F.S.; grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (MH076900) and the National Institute of Environmental Health and Safety (ES015747) to D.E.K.; and grants from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (DA020812) and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NS051453) to A.D.

References

- Alawi, A. A., and W. L. Pak, 1971. On-transient of insect electroretinogram: its cellular origin. Science 172 1055–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andretic, R., B. van Swinderen and R. J. Greenspan, 2005. Dopaminergic modulation of arousal in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 15 1165–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bainton, R. J., L. T. Y. Tsai, C. M. Singh, M. S. Moore, W. S. Neckameyer et al., 2000. Dopamine modulates acute responses to cocaine, nicotine and ethanol in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 10 187–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benzer, S., 1967. Behavioral mutants of Drosophila melanogaster isolated by countercurrent distribution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 58 1112–1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloch Qazi, M. C., Y. Heifetz and M. F. Wolfner, 2003. The developments between gametogenesis and fertilization: ovulation and female sperm storage in Drosophila melanogaster. Dev. Biol. 256 195–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borycz, J., J. A. Borycz, A. Kubów, V. Lloyd and I. A. Meinertzhagen, 2008. Drosophila ABC transporter mutants white, brown and scarlet have altered contents and distribution of biogenic amines in the brain. J. Exp. Biol. 211 3454–3466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budnik, V., and K. White, 1987. Genetic dissection of dopamine and serotonin synthesis in the nervous system of Drosophila melanogaster. J. Neurogenet. 4 309–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, J. L., and H. A. Nash, 2001. Volatile general anesthetics reveal a neurobiological role for the white and brown genes of Drosophila melanogaster. J. Neurobiol. 49 339–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson, A., 2006. The neurochemical circuitry of schizophrenia. Pharmacopsychiatry 39(Suppl 1): S10–S14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H.-Y., A. Grygoruk, E. S. Brooks, L. C. Ackerson, N. T. Maidment et al., 2006. Over-expression of the Drosophila vesicular monoamine transporter increases motor activity and courtship but decreases the behavioral response to cocaine. Mol. Psychiatry 11 99–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B., I. A. Meinertzhagen and S. R. Shaw, 1999. Circadian rhythms in light-evoked responses of the fly's compound eye, and the effects of neuromodulators 5-HT and the peptide PDF. J. Comp. Physiol. A Neuroethol. Sens. Neural. Behav. Physiol. 185: 393. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Colas, J. F., J. M. Launay, J. L. Vonesch, P. H Ickel and L. Maroteaux, 1999. Serotonin synchronizes convergent extension of ectoderm with morphogenetic gastrulation movements in Drosophila. Mech. Dev. 87 77–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole, S. H., G. E. Carney, C. A. McClung, S. S. Willard, B. J. Taylor et al., 2005. Two functional but noncomplementing Drosophila tyrosine decarboxylase genes: distinct roles for neural tyramine and octopamine in female fertility. J. Biol. Chem. 280 14948–14955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly, J. B., and T. Tully, 1998. Behavior, learning, and memory, pp. 265–317 in Drosophila: A Practical Approach, edited by D. B. Roberts. IRL, Oxford.

- Cooper, R. L., and W. S. Neckameyer, 1999. Dopaminergic modulation of motor neuron activity and neuromuscular function in Drosophila melanogaster. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 122 199–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corey, J. L., M. W. Quick, N. Davidson, H. A. Lester and J. Guastella, 1994. A cocaine-sensitive Drosophila serotonin transporter: cloning, expression, and electrophysiological characterization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91 1188–1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, R. W., C. A. Collins, M. V. Gelfand, J. Dant, E. S. Brooks et al., 2004. Increased expression of the Drosophila vesicular glutamate transporter leads to excess glutamate release and a compensatory decrease in quantal content. J. Neurosci. 24 10466–10474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, R. W., C. A. Collins, K. Chen, M. V. Gelfand, D. E. Featherstone et al., 2006. A single vesicular glutamate transporter is sufficient to fill a synaptic vesicle. Neuron 49 11–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasari, S., and R. L. Cooper, 2004. Modulation of sensory-CNS-motor circuits by serotonin, octopamine, and dopamine in semi-intact Drosophila larva. Neurosci. Res. 48 221–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demchyshyn, L. L., Z. B. Pristupa, K. S. Sugamori, E. L. Barker, R. D. Blakely et al., 1994. Cloning, expression, and localization of a chloride-sensitive serotonin transporter from Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91 5158–5162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draper, I., P. T. Kurshan, E. McBride, F. R. Jackson and A. S. Kopin, 2007. Locomotor activity is regulated by D2-like receptors in Drosophila: an anatomic and functional analysis. Dev. Neurobiol. 67 378–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond-Barbosa, D., and A. C. Spradling, 2001. Stem cells and their progeny respond to nutritional changes during Drosophila oogenesis. Dev. Biol. 231 265–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duerr, J. S., D. L. Frisby, J. Gaskin, A. Duke, K. Asermely et al., 1999. The cat-1 gene of Caenorhabditis elegans encodes a vesicular monoamine transporter required for specific monoamine-dependent behaviors. J. Neurosci. 19 72–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiden, L., M. H. Schäfer, E. Weihe and B. Schütz, 2004. The vesicular amine transporter family (SLC18): amine/proton antiporters required for vesicular accumulation and regulated exocytotic secretion of monoamines and acetylcholine. Pflügers Archiv. Eur. J. Physiol. 447 636–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson, J. D., and H. Varoqui, 2000. Molecular analysis of vesicular amine transporter function and targeting to secretory organelles. FASEB J. 14 2450–2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkenburger, B. H., K. L. Barstow and I. M. Mintz, 2001. Dendrodendritic inhibition through reversal of dopamine transport. Science 293 2465–2470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y., A. Ueda and C. F. Wu, 2004. A modified minimal hemolymph-like solution, HL3.1, for physiological recordings at the neuromuscular junctions of normal and mutant Drosophila larvae. J. Neurogenet. 18 377–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fon, E. A., E. N. Pothos, B.-C. Sun, N. Killeen, D. Sulzer et al., 1997. Vesicular transport regulates monoamine storage and release but is not essential for amphetamine action. Neuron 19 1271–1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox, L. E., D. R. Soll and C. F. Wu, 2006. Coordination and modulation of locomotion pattern generators in Drosophila larvae: effects of altered biogenic amine levels by the tyramine Beta hydroxlyase mutation. J. Neurosci. 26 1486–1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukui, M., R. M. Rodriguiz, J. Zhou, S. X. Jiang, L. E. Phillips et al., 2007. Vmat2 heterozygous mutant mice display a depressive-like phenotype. J. Neurosci. 27 10520–10529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girault, J. A., and P. Greengard, 2004. The neurobiology of dopamine signaling. Arch. Neurol. 61 641–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gramates, L. S., and V. Budnik, 1999. Assembly and maturation of the Drosophila larval neuromuscular junction, pp. 93–117 in Neuromuscular Junctions in Drosophila, edited by V. Budnik and L. S. Gramates. Academic Press, San Diego. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Greer, C. L., A. Grygoruk, D. E. Patton, B. Ley, R. Romero-Calderón et al., 2005. A splice variant of the Drosophila vesicular monoamine transporter contains a conserved trafficking domain and functions in the storage of dopamine, serotonin, and octopamine. J. Neurobiol. 64 239–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruntenko, N. E., E. K. Karpova, A. A. Alekseev, N. A. Chentsova, E. V. Bogomolova et al., 2007. Effects of octopamine on reproduction, juvenile hormone metabolism, dopamine, and 20-hydroxyecdysone contents in Drosophila. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 65 85–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]